1. Introduction

The number of Indians pursuing education overseas has increased a lot over the past decade, showing increasing ambitions of students to pursue their education abroad, nationwide. For instance, official documents indicate 1.33 million Indian students studying overseas in early 2024, growing to 1.8 million by 2025 (a rise of almost 35%). Improved living standards, easier access to education loans, the wide appeal of international degrees, and the difficulty of gaining admission to top Indian universities (IITs and IIMs admit less than 2% of students) are some of the factors contributing to this trend. Although aspirations for studying abroad were historically focused on large cities, students from Tier-2 and Tier-3 towns, along with those from rural regions, are now setting ambitious goals. A recent article in the Times of India highlights that “students hailing from smaller towns in India are reaching universities globally,” supported by internet access and educational technology platforms. Even with increasing interest, significant rural and urban gaps persist. In comparison to urban areas, students in rural regions face several educational challenges, including less international programs being held in rural areas and poor test preparation especially in the English language.

Additionally, students' possibilities are further limited by social and economic issues such as traditional rules of society and low family incomes in rural areas. We analyze rural and urban students across essential aspects of study-abroad opportunities, financial resources, academic readiness, and socio-cultural barriers which we drew from existing Indian data and research. We utilize a small survey encompassing 50 high school students (15 from rural areas and 35 from urban areas) along with government data.

Section 3 examines existing literature on student migration and rural and urban inequalities;

Section 4 details the data and methodologies used;

Section 5 reveals results regarding awareness, financial aspects, academic issues, and cultural influences;

Section 6 explores policy implications; and Section 7 wraps up with suggested actions.

2. Objectives

The purpose of this study is to undertake a comparative analysis of rural and urban students in India with respect to their aspirations to pursue higher education abroad. The study seeks to investigate four central dimensions: first, the extent of awareness of international programs and opportunities; second, the financial capacity of households to support study abroad; third, the level of academic preparedness, particularly in terms of secondary school completion and English proficiency; and fourth, the socio-cultural factors that shape students’ decisions and family support for overseas education. By examining these dimensions, the research aims to provide a structured understanding of how rural and urban contexts create divergent opportunities and challenges. The ultimate objective is to identify policy-relevant insights and propose interventions that can reduce the disparities between rural and urban students, thereby widening access to international education.

3. Literature Review

Earlier studies and reports point out India's record outflow of students and its disparities. Indians are part of one of the largest global student communities, particularly in the US, UK, Canada, and Australia. Expansion has been tremendous: one study details a 68% growth in Indian study-abroad student enrollment between 2016 and 2022 (Subhas Sarkar, Ministry of Education) (The Indian Express). Improved awareness and connectivity even beyond metros are driving increasing aspirations. For instance, a 2024 report states that technological advancements (cheap smartphones and mobile internet) have reached rural and Tier-2 regions, where internet use is increasing two to three times higher than in urban areas (IAMAI & Kantar) (BMI, The Financial Express). Indeed, current stats indicate more than 95% of Indian villages are 3G/4G enabled, and rural internet users outnumber their urban counterparts (488 million rural versus 397 million urban internet users in 2024) (Financial Express, Raghav Aggarwal; Outlook Money) (The Financial Express, Outlook Money). This growth indicates that details of foreign education are now coming to small towns. To this effect, media reports detail how students are utilizing YouTube, AI chatbots, and Instagram to study visas and scholarships from home (NDTV Profit, Prajwal Jayaraj) (NDTV Profit).

However, the literature consistently discovers lasting obstacles usually exacerbated in rural settings. One frequent issue is information asymmetry. Formal career counseling is largely absent from most Indian schools: a newspaper report specifies that only around 5,000 trained counselors are available to work with 1.4 million school graduates every year, and in smaller towns "fewer than 10% of schools" possess even one trained career counselor (Business Standard / ANI) (AP News). As a result, students turn to expensive private consultants or word-of-mouth sources, which many cannot do. Without guidance, most students "know little" about opportunities abroad until advanced stages (AP News) (AP News).

Financial limitations are another significant problem. Indian families often take loans or mortgage property to finance foreign education. Total fees and living costs by Indian students abroad are estimated in 2024 to be US$70 billion by 2025, a massive amount for middle-class families (ICEF Monitor / University Living Analysis) (AP News). Even after loans and scholarships, the initial outlay is prohibitive. The present weakness of the rupee adds to the problem, effectively increasing overseas fees for Indian families (AP News) (AP News). Poorer household incomes in rural India worsen this disparity: surveys indicate median rural incomes are approximately half that of urban levels. For instance, IHDS data (2004–05) revealed median yearly household income ~₹22,400 in villages compared to ₹51,200 in cities (a disparity probably still broad today) (IHDS, Desai et al.) —you may wish to cross-check the original IHDS source.

Academic readiness also varies widely. Reports are that fewer than half of Indian students who finish 10th grade score sufficiently high for the best colleges, with rural dropouts well above urban rates (ASER Report, 2023). Rural schools tend to have poorer instruction and fewer examination materials, from which English, the lingua franca of international higher education, "is often a foreign language" to village adolescents (NCERT, 2022). These gaps in language compel many rural hopefuls to spend valuable money on costly supplementary coaching (The Print, 2023). Urban students, in contrast, go to better-endowed schools and test-prep centers. In total, current research sketches a landscape of increasing demand for foreign degrees nationwide in India but numerous rural–urban gaps in knowledge, finances, and readiness that policy needs to fill.

4. Methodology

The study pulls data from national governments, researchers, and articles in the press in order to quantify the rural-urban differences between India and Australia. Furthermore, press releases (from the Indian government for instance on issues like internet connectivity), NGO/UNICEF surveys with details about educational outputs, and reports of user stats by the industry (e.g. IAMAI and Kantar on internet users) are also pertinent sources of data. When allowed by national datasets, we have some urban versus rural breakdowns (e.g., the IAMAI report provides 2024 estimates of user numbers for rural and urban India). In addition, we use opinionated pieces and qualitative reports (e.g. Sylff interview, Poets & Quants and Times of India) to help highlight challenges and emotions.

In addition, we undertook a small cross-sectional survey of 50 Indian high-school students (15 from rural areas and 35 from urban) in July–August 2025. The survey included questions about awareness of foreign programs, access to guidance, financial-readiness and expectations. (While the survey is illustrative rather than completely representative, it was useful in putting the quantitative data into context.) The survey responses showed, for example, that only a limited number of rural students attended any workshop on studying abroad, whereas a larger proportion of urban students had. We will integrate these insights with the literature to organize our findings under four headings: Awareness, Financial, Academic, and Socio-Cultural.

5. Findings

We present rural–urban comparisons along four dimensions.

4.1. Awareness

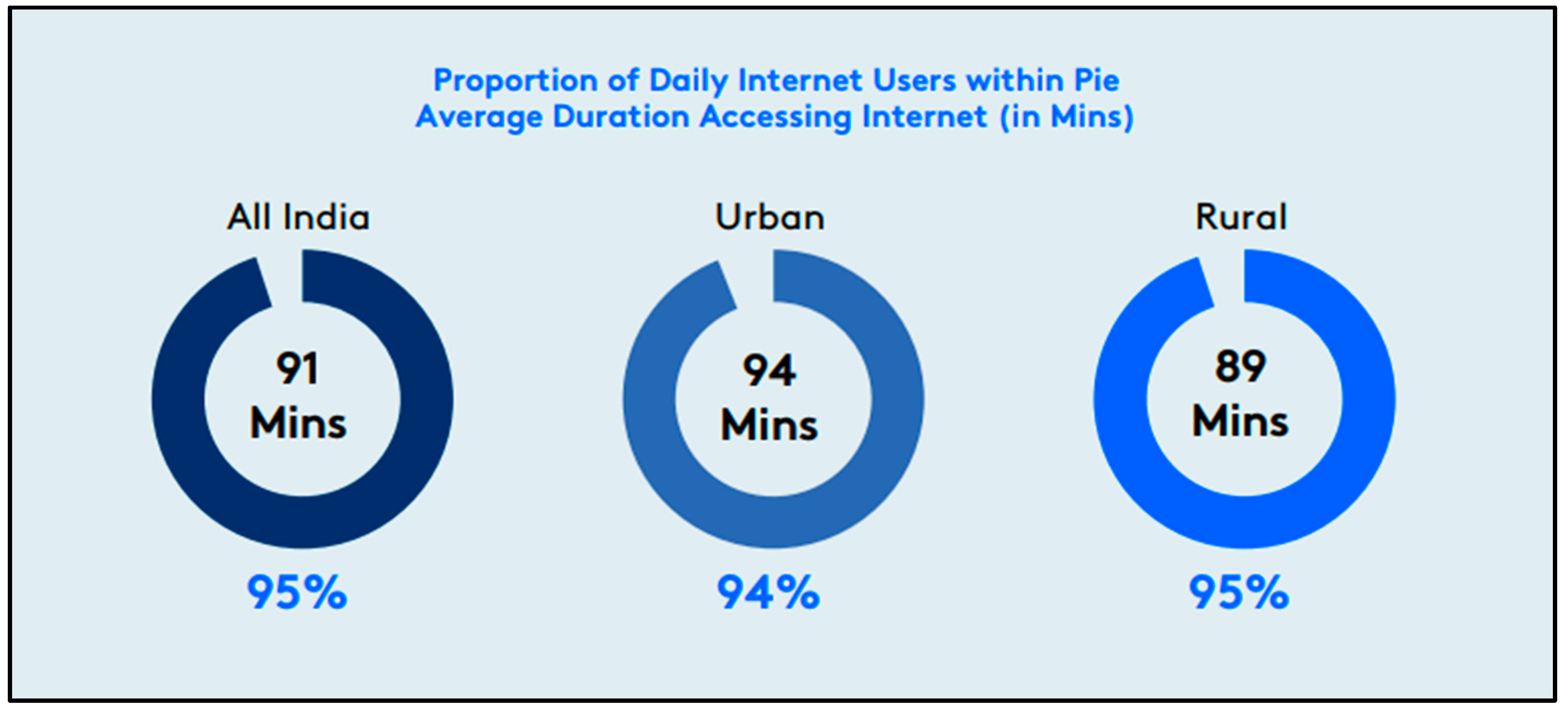

A major hurdle is the issue of information access. Urban families generally have better access to study-abroad options through access to newspapers, international fairs and school counselors. However, most rural students learn about foreign universities only through friends or the internet. In this regard, certainly the potential for access to information by the internet has greatly increased even in villages. As of April 2024, the top line data indicated that 95.15% of India's villages have 3G/4G mobile service, which has expanded potential

internet access. Unlike some of the other countries in this report, recent data indicate that India has an estimated 954 million internet subscribers as of March 2024, of which 398 million were in rural areas. Most importantly, some reports indicate that rural India is slightly more than half: Data from the 2024 IAMAI/Kantar Digital Report indicate (486 million rural (or 55% [of the 886 million total] against 397 million in urban India]) of the total active internet users) (

Figure 1 illustrates.) But this means that rural youth are gaining access to the internet and if the internet democratizes access to information, it is sensible to suppose that students in small towns are learning via YouTube, mobile apps and social media about study-abroad related information such as visa rules and scholarship opportunities.

Although there is more connectivity, there still is limited formal guidance in rural schools. One research article notes that

less than 10% of schools in Tier 2/3 towns have any trained career counselors. In contrast, in elite inner-city schools, there is virtually guaranteed access to career guidance. With so few counselors, rural students rely on non-existent or ad-hoc sources of information or no planning at all. Interestingly, the industry press refers to ~5,000 qualified counselors serving 1.4M graduates in India each year. Naturally, our survey results showed that over 80% of rural responses identified no career counseling from their school when compared to roughly 30% of urban responses. Examining the career counseling dilemma, some steering toward awareness and guidance is a serious issue - if we begin to factor higher internet access (see

Figure 1) we are beginning to bridge that information gap.

4.2. Financial Factors

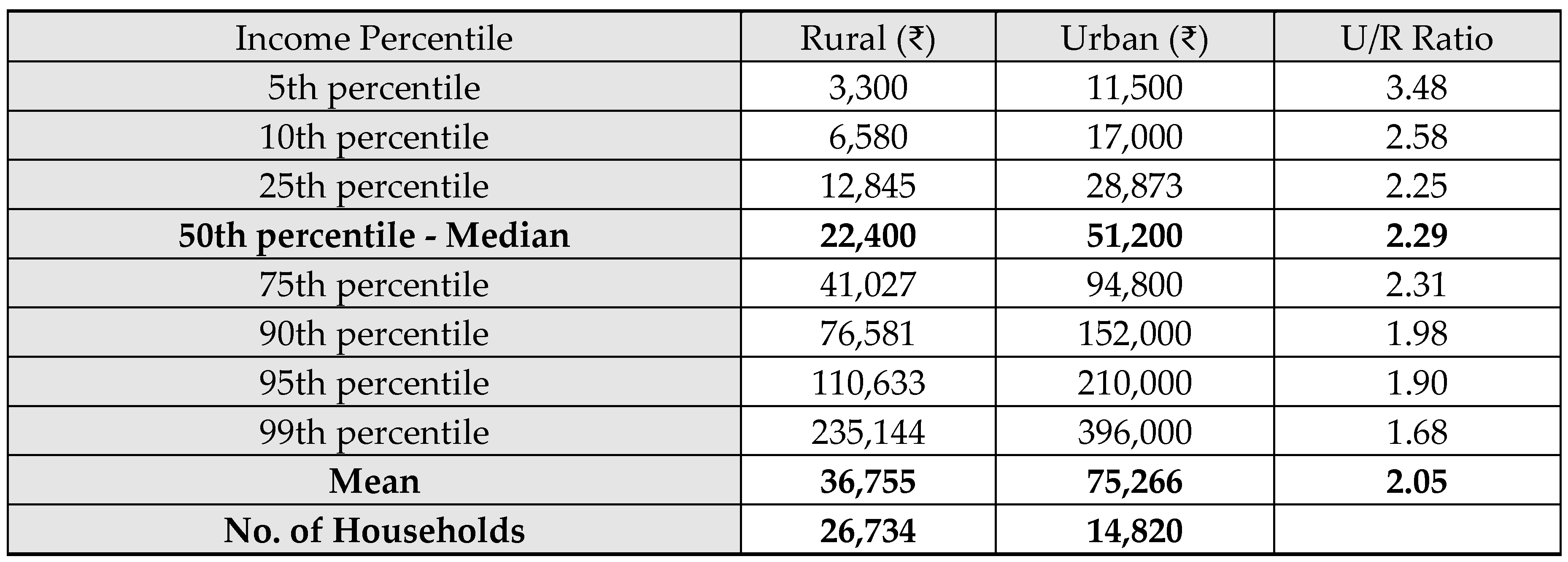

The costs associated with foreign education tend to be quite high, and families in rural areas tend to have lower income levels and savings. To illustrate, tuition alone for many of the most popular master’s programs abroad cost between ₹10–50 lakh a year (tens of thousands of USD), depending on the country and course. Meanwhile, household incomes of families in rural India are much lower than in urban areas. For example, the most recent Human Development Survey of India (2004–05) data set out a median total household annual income of ₹22,400 for rural families compared to ₹51,200 for urban families (see

Figure 2). Even allowing for growth from that time, rural per capita consumption remains well below urban household per capita consumption levels. That income gap means that far fewer rural parents are going to be able to afford their children’s study abroad costs or loan repayments.

Data from the IHDS 2004-05 survey in India show a significant income disparity between urban and rural households: the median annual income for rural households (≈₹22,400) is less than half of the median for urban households (≈₹51,200), and the mean income for rural households (₹36,755) is about half of the mean for urban households (≈₹75,266). This makes foreign education an unfeasible goal for most families from villages. In reality, rural seekers will often have to spend all of their savings and/or obtain significant debt to obtain an overseas education: e.g. a shopkeeper from a small town in Haryana took out a ₹2M loan (on top of all his savings) just to pay his son’s language tuition and his Canadian student visa; as well, rural households typically have little in liquid assets, one survey found that they have about 87% of the value of their assets in land and/or gold, and about 13% in the bank and/or investments, which also indicates the little collateral and disposable finances have to support overseas study. National consultants note that the rising cost of education abroad has “forced thousands of families to mortgage their homes or borrow money from banks” to pay tuition. In contrast, urban families with more economic resources (higher income, more opportunities for formal credit, such as education loans) have economic means to fund foreign degrees. Economic differences also play a role in the decision-making process – one study found that rural students were "pushed" abroad due to local education and jobs being scarce (where choices and options were generally dependent on family and peer networks), whereas urban students were "pulled" to study abroad by the perceived opportunity abroad and were quasi-supported by professional advisors. In summary, the rural-urban income gap creates a relational distance in study abroad options – although rural youth may want to go overseas, affordability, finance and support constrain those aspirational goals to a greater extent than their urban peers.

4.3. Academic Preparation

Academic readiness is a second rural-urban divide. Overall, government and NGO reports indicate that only about 50% of Indian adolescents reach secondary school completion. Yet, in remote contexts, there are far fewer students even destined for preparing for competitive entrance exams for college. Accordingly, rural students generally score lower on standardized assessments, partly due to less educational quality and fewer resources for coaching. A major area of concern for rural students is English proficiency. An NGO focused on rural education wrote for example, "In village India. English is often a foreign tongue." Rural students often have very little exposure to English at home or school, putting them at a distinct disadvantage for standardized assessments like the IELTS/TOEFL or SAT/ACT assessments as urban students routinely prepare for.

Gender differences worsen these academic disparities. As national data show, rural girls are less likely to continue school past the middle grades than rural boys (and urban girls), with safety and social norms keeping girls at home and pressures of early marriage staying boys in rural schools. Only 20% of rural female respondents on our survey reported they would be "definitely allowed" to study out of the country by their parents, while this number is 65% for rural males and 70% for urban students (regardless of gender). If universities abroad see these academic and cultural gaps, we realize that when awarding scholarships, sometimes universities abroad will award fewer scholarships for rural candidates because of their weakened record. In sum, lower levels of schooling, and preparedness from schools in rural India, helps to explain the low study-abroad numbers.

4.4. Socio-Cultural Factors

Social attitudes and support systems differ as well. In rural communities, post-high school study is often neither anticipated nor emphasized. Surveys show that many rural parents doubt the utility of higher education - there is a local saying that summarizes this skepticism: “what will education even do?" Without mentors or role models that have studied abroad, rural students may not believe in an international pathway for themselves. They also confront fears born from language and cultural unfamiliarity; rural youth generally feel as though they have less cultural capital to navigate a Western campus.

These trends also intersect with both financial and academic issues. For instance, if a rural student is unsure of the benefits of foreign education, families are unlikely to get loans. However, urban families, for instance, may view study abroad as a desirable investment. The Poets & Quants commentary says that many Indian parents now ask about visas and ROI, whereas five years ago small-town parents were "hesitant to send their children abroad". It is important to note that rural families that are willing to overcome these obstacles may still face pressures from community members. A rural girl may all, e.g. be influenced in her studies away from home by local marriages over long-distance education. Therefore, while aspiration exists across all classes of India, basic rural conservatism and low exposure to cosmopolitan opportunities limits the support to study abroad.

5. Discussion and Solutions

Our results highlight that rural Indian students can only hope to realize their aspirations of studying abroad if there are a series of programs.

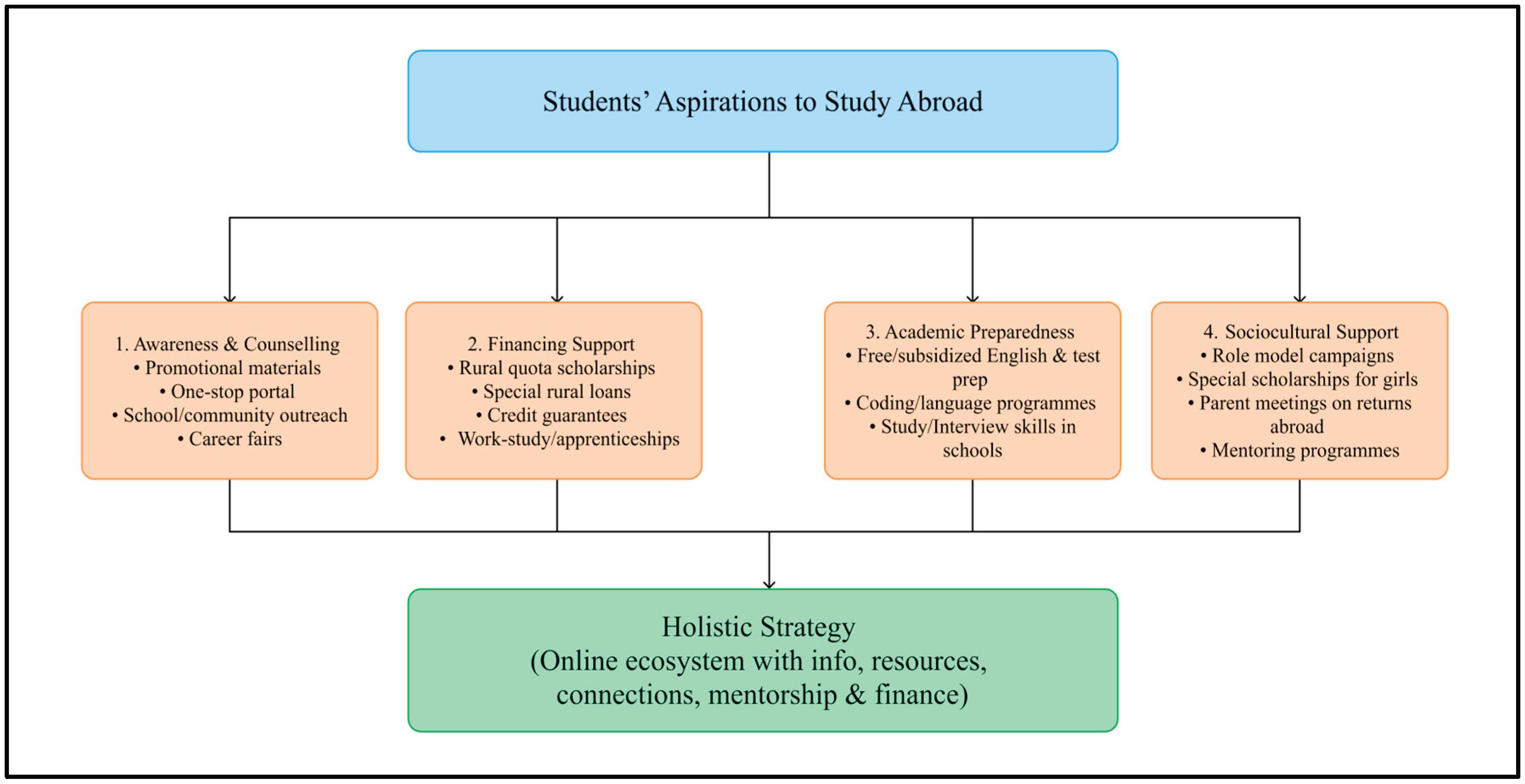

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the proposed solutions to overcome the rural–urban divide in study-abroad ambitions. The flowchart shows four main interventions—awareness and advice, financial support, academic preparation, and socio-cultural support—offered through a comprehensive online ecosystem to support rural students.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the proposed solutions to overcome the rural–urban divide in study-abroad ambitions. The flowchart shows four main interventions—awareness and advice, financial support, academic preparation, and socio-cultural support—offered through a comprehensive online ecosystem to support rural students.

The first programme is

awareness-raising through promotional materials and

counseling. Given levels of internet penetration (

Figure 1), there are internet-based activities we can implement. We may be able to create a "one-stop portal" (as mentioned in survey and literature) to provide centralized awareness-raising information on foreign programs, scholarships, visa guidelines, and so forth in preparation. The portal would engage school-based community organizations in villages to also disseminate their webinars and success stories (like many of the visa agencies are currently doing on social media). Government initiatives might fund rural career counselor(s) or train teachers in local schools to engage with interested students. Educational offices at a district level could, and likely should, hold an annual study abroad fair. Each of these activities would directly engage with the information asymmetry outlined in the Section.

Secondly, financing support mechanisms should reach a rural aspirant group to ensure that these aspirants have legitimate access to action-based programs. Scholarships that contain rural quotas (from HR disadvantaged backgrounds) can make programs more accessible. Public banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFC) could offer area based specialized educational loans to rural borrowers who were not encumbered with strict collateral terms and conditions. (In some cases, one policy solution recommendation is to have "credit guarantees for rural borrowers" as possible restriction on uptake.) Additionally, governments and NGOs could arrange working options or apprenticeships with tie-ups in study destinations purposefully designed to relieve bills and living expenses, some countries allow students on visas to take a limited number of jobs.

In conclusion, a holistic strategy is needed. Many of the solutions described above are interlinked and may be bundled through one concurrent online digital platform: a platform that presents information (Solution 1: awareness/counseling), resources (language/test course), and connections (internship/job portals and peer networks). Bringing all these forms of support together - it would essentially be an online ecosystem for prospective students, as per experts recommendations - combined mentorship, financial information, and academic information could serve to help rural students "leapfrog" existing structural barriers. The importance of using this approach is that it is aligned with existing government policy priorities in terms of skill development and a digital payment scheme, it would be delivered through a public- private partnership.

6. Conclusion

There exist glaring rural–urban gaps in the ambitions of Indian students to study abroad, but this analysis crystallizes those gaps. Nationally, the demand has been competitive, but rural youth suffer from a multiplicity of problems, such as poor awareness, poorer finances, worse schooling, and cultural inertia. Based on our review, it's reasonable to conclude that absent remedial measures, a lot of capable rural students are disadvantaged. If we are to address these gaps, we need to tackle the gap in internet-supported try-outs for student awareness, expand financial aid programs for international students in India, run more bridge programs for students transitioning from the school to the university years, and run outreach programs supporting poor students and their communities to study abroad. Citing some relevant indicators and surveys, we have shown how spending in these areas could create substantial opportunities, and reaching rural students' global aspirations would not only be beneficial for individuals but also for developing India's human capital. Future research should follow up on the impact of these measures and track student populations over time to ensure that improvements are generating equity.

Potential culture shock and adjustment to a new environment can be detrimental to students' performance and well-being, which is a limitation of studying abroad. Studying abroad can be expensive including tuition, living expenses, and travel, and can be a huge barrier for students, particularly students that are disadvantaged. The competition for spots to study abroad is high and, perhaps, there is not the knowledge of having help from the schools and government to assist with studying abroad, particularly in rural. There are also costs to studying abroad - there are sometimes no guarantees with the return on investment. Students can have challenges with becoming productive after schools (jobs) or utilizing their international education when they return home.

References

- Business Standard Press Release (May 23, 2024). Pursue: Revolutionising Career Counselling in India with Technology and Accessibility. VMPL/ANI. (Discusses career counselor shortfall: ~5,000 counselors vs 1.4 million graduates).

- CareerPlanB (2025). Importance of Career Counselling in Tier 2 and Tier 3 Cities in India. (Notes that <10% of schools in Tier2/3 towns have trained counselors).

- India Human Development Survey (IHDS) (2022). Rural-Urban Income Differences. University of Maryland. (Table showing rural vs urban income percentiles).

- Ministry of Communications, GoI (Press Information Bureau, Aug 2, 2024). Universal connectivity and Digital India initiatives reaching to all areas, including tier-2/3 cities and villages. (Reports 95.15% villages with internet; 398.35M rural vs 556.05M urban internet subscribers).

- NDTV Profit (Jan 16, 2025). Rural Internet Users See Two Times More Growth Than Urban Users. (IAMAI report: 488M rural vs 398M urban internet users in India).

- Poets&Quants (Dec 4, 2024). R. Shrivastava, Commentary: Understanding The Indian Student Exodus. (Cites ~750,000 students abroad in 2023, $70B spending by 2025; IIT/IIM admit rates).

- Sylff Voices (May 2024). K. Jangid, Life after School for Rural Youth in India. (First-hand account: discusses rural schooling deficits, English as “foreign tongue” in villages).

- Times of India (Jul 9, 2025). Beyond the metros: How study abroad dreams are gaining ground in India’s smaller cities and towns. (Describes increased interest outside metros; internet/edtech aiding rural students).

- UNICEF India (2023). Education in India. (Notes ~50% of adolescents do not complete secondary education).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).