1. Introduction

Aesthetic perception, understood as the cognitive and emotional process of engaging with an object - whether a work of art or a natural scene- has been extensively studied in psychological research. Leder et al. [

1] emphasized a multi-stage model that gives minimal weight to beauty itself, and the following update of this model [

2] more explicitly incorporated emotional and contextual factors. This interest stems from the complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, and cultural factors that shape human engagement with the visual world [

3,

4]. A central element of aesthetic experience is the relationship between the physical attributes of an object and the emotional and psychological responses they elicit in the observer. This dynamic interaction contributes to the inherently subjective nature of aesthetic judgments. Because aesthetic judgments are deeply rooted in perceptual processes, understanding how the human mind interprets visual stimuli is crucial to comprehending the process behind aesthetic judgment. In the study of perception, Gestalt theories provide a fundamental framework for understanding how individuals experience complex visual forms. These theories propose that perceptual organization follows universal principles such as symmetry, figure-ground relationships, proximity, similarity, and common fate [

5,

6]. Gestalt psychology asserts that the mind does not passively register visual stimuli but actively organizes them through cognitive and psychological mechanisms that impose order and coherence upon the chaotic input from the environment [

7]. This active structuring process is central to our understanding of how visual stimuli are perceived aesthetically. It suggests that aesthetic judgment is not simply a passive or purely subjective response to sensory input but a dynamic cognitive process that involves organizing and interpreting visual elements according to inherent principles of perception. Gestalt principles have been widely applied to the study of aesthetic perception, providing valuable insights into why certain visual arrangements are experienced as harmonious, balanced, or aesthetically pleasing [

8,

9]. Complementing Gestalt theories, Westphal-Fitch et al. [

10] employed production-based methods to investigate how context and local symmetry influence aesthetic judgments. Their research demonstrated that aesthetic preference is not solely dependent on universal perceptual principles but is modulated by environmental context and the structural features of stimuli, highlighting the active role of the observer’s perceptual and cognitive engagement.

For example, symmetry and closure facilitate the perception of order and stability, contributing to more positive aesthetic evaluations [

5,

11]. Similarly, figure-ground segregation plays a crucial role in directing visual attention and shaping how works of art, design compositions, and natural landscapes are aesthetically interpreted [

12]. Recent neuroaesthetic research has provided empirical support for the role of Gestalt principles in shaping aesthetic experience [

13,

14]. These findings underscore the idea that aesthetic perception is not merely subjective but relies on universal cognitive processes that shape our experience of visual beauty. Understanding how perceptual grouping, symmetry, and figure-ground relationships influence aesthetic judgments enriches both theoretical models of visual perception and practical applications in diverse fields, such as art, design, and architecture. These areas rely heavily on visual appeal and the principles that underlie aesthetic preferences. In addition to serving as universal mechanisms for visual organization, Gestalt principles provide a lens through which to explore how individual differences and cultural influences may modulate aesthetic experience. Research suggests that individual differences, such as personality traits, cognitive styles, and prior experiences, can significantly influence how Gestalt principles shape aesthetic judgments [

2]. For example, expertise in art and design plays a key role in shaping aesthetic preferences, with trained artists often demonstrating heightened sensitivity to compositional subtleties that differ from the general population’s preference for simplicity and symmetry [

15]. This difference in preference arises because artistic expertise enhances perceptual fluency and cognitive flexibility, allowing experts to appreciate deviations from prototypical patterns rather than simply seeking visual coherence [

16]. Supporting this view, Höfel and Jacobsen’s electrophysiological studies [

17,

18] distinguish between spontaneous and intentional processes in aesthetic perception, revealing that both bottom-up sensory inputs and top-down cognitive control contribute to how aesthetic stimuli are processed in the brain. These findings align with Leder’s framework by demonstrating the interplay of automatic and controlled neural mechanisms in aesthetic appreciation, which may vary depending on expertise and cognitive engagement. Taken together, these studies highlight that aesthetic perception is a multifaceted process influenced by perceptual principles (Gestalt), contextual and emotional factors [

2], and neural mechanisms modulated by cognitive engagement and expertise [

17,

18]. Thus, a dynamic interplay between perceptual learning, cognitive adaptation, and aesthetic appreciation varies across individuals. Building on these findings, the present study aims to extend our understanding of the role of Gestalt principles in aesthetic judgment by examining how visual modifications affect the perception of sacred art. This study focuses on how small adjustments in visual attributes can influence the appreciation of beauty and emotional arousal. The artwork chosen for this research is a mosaic from the Church of St. Agnes Outside the Walls, a sacred work of great historical and religious significance. This choice provides an ideal context for examining the impact of Gestalt principles on aesthetic judgment since the structure and ornamentation of the mosaic provide a clear opportunity to manipulate key perceptual features such as symmetry, good form, common fate, and figure-ground organization. The use of mosaic art as the primary stimulus is based on the unique perceptual and aesthetic qualities inherent in mosaics. Mosaics are inherently highly structured compositions in which visual harmony results from the careful arrangement of individual tesserae. This makes them particularly well suited for testing Gestalt principles such as symmetry, figure-ground organization, and closure. Moreover, the religious context of mosaic art adds a layer of symbolic and emotional significance that can further modulate the viewer’s aesthetic response. While Gestalt laws have been extensively studied in general visual perception and other forms of art, their application to sacred art has not been explored. Sacred art is characterized by codified aesthetic conventions, symbolic content, and spiritual functions that differentiate it from secular art. Unlike modern or abstract paintings that are likely to encourage subjective interpretations, sacred art is governed by some rules of composition that are intended to evoke specific emotional and contemplative responses [

19]. This structured schema provides a steady environment for experimental manipulation, allowing the stringent examination of whether general perceptual processes, such as Gestalt principles, operate similarly in regions where visual elements are highly embedded in cultural and religious schemas. Furthermore, testing Gestalt principles in religious artwork raises the issue of whether religious experiences of beauty involve distinct perceptual or cognitive processes compared to secular aesthetic experiences. For instance, researchers have shown that verticality and symmetry are significant determinants of perceived sacredness (19). Therefore, this study makes a novel contribution by bridging the gap between perceptual science and the emotionally and culturally loaded domain of sacred art, ascertaining whether the identical principles of visual organization that guide general aesthetic responses are applicable in contexts where meaning and emotion are highly codified. Specifically, this study aims to contribute to the growing body of research on aesthetic perception by exploring how visual modifications of Gestalt principles influence the emotional and cognitive experiences associated with sacred art. By examining how subtle changes in symmetry and figure-ground relationships affect aesthetic judgments, the study aims to shed light on the underlying cognitive and neural processes that guide our appreciation of beauty in sacred art. This research advances theoretical knowledge about the intersection of perception, cognition, and aesthetics and has practical implications for designing religious and sacred spaces where visual appeal plays an integral role in shaping emotional and spiritual experiences.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

One hundred and twenty-seven participants volunteered to take part in this study (age: 25.04 ± 2.7 years; 78% female). Seventeen had master's degrees (17%), and one hundred and ten had bachelor's degrees (83%). Participants were recruited and tested in a controlled laboratory environment to ensure standardized experimental conditions. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1991), and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Dynamic, Clinical, and Health Psychology at Sapienza University of Rome (Protocol No. 0000216, 16/02/2022). Using G*Power, we computed a sensitivity analysis to detect a significant effect (minimum sample: 120 participants, considering α = 0.05 and 1 − β = 0.80, and a medium effect size).

2.2. Outcomes

2.2.1. Artistic Culture Questionnaire

The Artistic Culture Questionnaire was designed to quantify participants' aesthetic engagement and artistic literacy across a spectrum of art modalities, including but not limited to musical, cinematographic, and monumental forms. The instrument consists of three distinct sections: first, socio-demographic variables are collected; then, the degree of affective response and cognitive involvement elicited by diverse artistic stimuli was collected; finally, participants are queried regarding their prior exposure to the specific architectural and decorative elements of the Church of Saint Agnes Outside the Walls.

2.2.2. Aesthetic Rating Questionnaire

The Aesthetic Rating Questionnaire quantifies participants' subjective affective responses to visual stimuli, employing a semantic differential scale consisting of twenty bipolar adjectival descriptors. These descriptors were categorized into a composite score of positive aesthetic valences, including attractive, beautiful, delightful, elegant, fascinating, pleasant, magnificent, marvelous, and splendid. They were chosen to operationalize positive hedonic and aesthetic appraisals elicited by the presented images. Using a composite score simplifies the analysis and interpretation, allowing us to focus on the general aesthetic response elicited by the stimuli rather than fragmenting the data into multiple related but potentially correlated dimensions. These terms represent constructs associated with perceptual harmony, aesthetic pleasure, and visual attractiveness [

20]. Participants were instructed to rate each visual stimulus using a seven-point Likert scale, anchored by 'not at all' and 'very much,' to indicate the degree to which each adjectival descriptor applied to the presented stimuli.

2.3. Stimuli

The study used modified and original images of St. Agnes Outside the Walls mosaic to explore aesthetic judgments regarding Gestalt principles. The choice of this mosaic of the seventh century was based on its characteristics that are in accordance with the Gestalt principles. The apse mosaic depicts St. Agnes in the middle, symmetrically flanked by two similar male figures (Pope Honorius and Pope Symmachus), respecting both spatial and chromatic symmetries. The three figures are the same size, according to a good form principle, but they are not parallel but converging towards a unique point above their heads, according to the common fate principle. Finally, the golden background highlights these figures according to the principle of figure-ground ratio.

A single photograph of the apse mosaic was used as the baseline image, from which eighteen variations were created using GIMP2 software (version 2.10.24). These images were altered according to different Gestalt principles, including spatial symmetry, chromatic symmetry, figure-ground ratio, good form (changing the St. Agnes’ image size), and common fate. For spatial symmetry, the central figure of Saint Agnes was manipulated in several ways. Two images were modified by moving the figure: one was moved to the right and rotated 10° clockwise, while the other was moved to the left and rotated 10° counterclockwise. This category was called spatial asymmetry-displacement. Additionally, two images were created to represent spatial symmetry-enlargement, in which the figure of Saint Agnes was enlarged to 112% and 120% of its original size. Another two images were created to represent spatial symmetry-reduction, in which the figure was reduced to 75% and 65% of its original size. For chromatic symmetry, two images were modified to introduce chromatic asymmetry by changing the color of the Pope figure. In one image, the Pope on the right was presented in shades of red, while in the other, the same figure was given in shades of green. In addition, two other images changed the figure-ground relationship: one image replaced the gold background with a starry blue background, while the other replaced it with a green background. The last four categories incorporated both symmetry/asymmetry and common fate principles. In the first image, the symmetry of the figures was maintained, but the two popes were oriented to face outward and positioned close to the saint. The second image maintained the symmetry but moved the popes to the edges of the image, breaking the principle of common fate for which the vertical axes of the three figures converged to a unique point placed above their heads. The final two images were characterized by the absence of symmetry and no adherence to the common fate principle, with the figures of the two popes shifted.

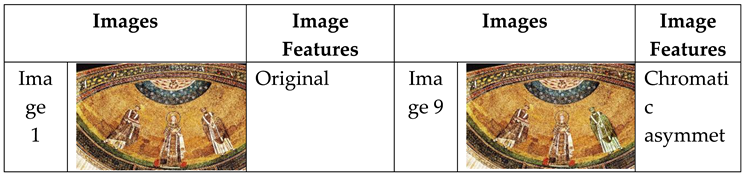

Table 1 below summarizes the characteristics of each modified image.

2.4. Procedure

In strict adherence to the pre-established research protocol, participants began the experimental session by completing the Artistic Culture Questionnaire after providing informed consent. This instrument established a baseline measure of their pre-existing artistic knowledge and engagement. Then, participants engaged with the experimental stimuli, presented on an FHD screen of 27’’: a sequence of 15 high-resolution digital images depicting the apse mosaic of St. Agnes Outside the Walls. Immediately following the presentation of each visual stimulus, participants completed the Aesthetic Evaluation Questionnaire, which was designed to quantify their subjective aesthetic responses. Each digital image was presented using calibrated projection software for a standardized exposure duration of 20 seconds. Considering the subtle compositional difference, this viewing time was chosen to ensure that participants had sufficient time for deliberate judgment. An adequate interval (until 2 minutes) was provided between items to allow participants sufficient time to respond to the questions.

2.5. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, as well as frequency counts and percentages, were utilized to characterize the data. To simplify the analysis, a composite aesthetic score was created by averaging the aesthetic judgments associated with each image. This composite score allowed overall aesthetic evaluation to be considered rather than separately analyzing individual valence responses. Specifically, the total positive valence scores were considered rather than individual adjective responses. Since all individual analyses in single aesthetic judgment revealed significant differences between the original and modified images, creating a composite aesthetic score provided a more concise representation of the overall effect (See Supplementary material). A Pearson's r correlation analysis was performed to investigate the potential association between participants' artistic knowledge and their aesthetic judgments. Moreover, an average score for images that reported similar Gestalt modification was computed, obtaining the mean aesthetic judgment for the following categories: spatial asymmetry, St. Agnes enlargement, St. Agnes reduction, chromatic asymmetry, figure-ground ratio, symmetry no-common fate, and asymmetry no-common fate. To examine the effect of perceptual manipulations, derived from Gestalt principles, on aesthetic judgments of the mosaic images, a series of analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to compare the aesthetic judgment scores on the original and modified images (spatial asymmetry, St. Agnes enlargement, St. Agnes reduction, chromatic asymmetry, figure-ground ratio, symmetry no-common fate, and asymmetry no-common fate). To understand the role of previous exposure to mosaic, a mixed-design ANOVA on aesthetic judgment was conducted in a subsample (previously exposed/not exposed St. Agnes mosaic), considering the composite modification score.

The Student’s t-test was used for post hoc analyses. The alpha level of statistically significant results was set at 0.05.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that structural and chromatic modifications of visual stimuli significantly influence aesthetic judgment. The findings provide empirical support for the influence of Gestalt principles on aesthetic judgments, consistent with neuroaesthetic theories that emphasize the role of visual harmony and structural coherence in aesthetic evaluation [

21]. The original mosaic elicited a more positive aesthetic response, aligning with observations that homogeneous visual structures are favored [

22]. Other aspects, such as familiarity, influence aesthetic perception [

23].

While the study primarily evaluated the impact of perceptual manipulation, the observed influence of prior familiarity underscores the multifaceted nature of aesthetic judgment, where both bottom-up perceptual processes and top-down cognitive factors play crucial roles. Specifically, our results reveal that although only 13.5% of respondents were familiar with the Saint Agnes Outside the Walls mosaic, they expressed higher positive judgments than those unfamiliar with the work. This finding is consistent with literature highlighting the role of prior knowledge and experience in shaping aesthetic appreciation [

23], as well as studies on perception that report a positive association between familiarity with environmental contexts and positive emotion [

24]. Familiarity can enrich interpretation, allowing for deeper engagement with the artwork's historical and cultural significance, potentially leading to more positive evaluations. The mere exposure effect [

25] also suggests that repeated exposure to an artwork can increase liking and preference. Furthermore, familiarity effects are well-documented in aesthetics research, demonstrating how top-down cognitive processes modulate the influence of perceptual factors [

1,

26]. This interplay between prior knowledge and perceptual organization reinforces the necessity to consider both bottom-up and top-down factors in aesthetic judgments.

However, our central focus was to analyze whether some manipulations of Gestalt principles (e.g., symmetry, common fate) would alter the aesthetic judgment of the Saint Agnes Outside the Walls mosaic. The results reveal a consistent trend of lower positive aesthetic ratings for the modified images than the original. The main effect observed confirms that participants consistently rated the original mosaic image as more aesthetically pleasing than any modified version. This aligns with existing literature emphasizing the importance of perceptual organization principles—such as symmetry, grouping, and balance—in shaping aesthetic experience [

11,

27]. The aesthetic value was significantly reduced across manipulated conditions, particularly spatial asymmetry by displacement, symmetry with shrinkage, chromatic asymmetry, and absence of common fate. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that visual symmetry is a powerful contributor to aesthetic preference [

28,

29], and even subtle deviations from proportional structure can negatively impact perceptual harmony.

Our findings support our idea that altering stimuli by disrupting their Gestalt principles may reduce the aesthetic valence of stimuli. An alternative interpretation could be that changes to the original stimuli may reduce their aesthetic valence. However, there are two arguments in favor of our hypothesis over this alternative. First, not all changes had the same effect on aesthetic judgment. The change in background color reduced aesthetic judgment but not enough to produce a statistically significant difference compared to that reported for the original stimuli. The gold background typical of Byzantine mosaics was replaced with a blue or green backdrop. Despite being quite different from the original, these colors might still maintain a clear distinction between the background and the figures, not sufficiently altering the figure-ground principle. Previous research on figure-ground segmentation [

30] suggests that stable perceptual structuring is a key element in visual comfort and preference. In another case, the alteration led to a reduction in aesthetic judgment, but not sufficiently large to be statistically significant, when St. Agnes was enlarged with respect to the figures of the two Popes—probably because it still maintained perceptual salience at the center of the stimulus. Conversely, the reduction in the size of the central figure disrupts the perceptual salience and focal point of the composition, leading to a statistically significant decrease in aesthetic valence. Research in visual attention suggests that larger or more prominent elements capture attention more effectively and contribute to a sense of visual importance (31). Diminishing this central element leads to a less engaging and aesthetically pleasing perception. The introduction of chromatic asymmetry also significantly impacted aesthetic ratings. The preference for color harmony and balance is a well-documented aspect of human visual perception [

32]. Deviations from a harmonious color scheme, as introduced in our chromatic asymmetry condition, can be perceived as visually jarring or less aesthetically pleasing, potentially activating brain regions associated with processing visual incongruity.

The second argument against the alternative hypothesis—that any change could have reduced the aesthetic judgment of the stimuli —is that familiarity increased aesthetic judgment. However, the effects of alterations to Gestalt principles were still present in participants unfamiliar with the stimuli. These participants were unaware of which stimulus was the original and could not clearly identify which changes had been applied. In this sense, they were naïve with respect to all the stimuli.

From a neurasthenic perspective, these findings align with studies suggesting that the brain's reward system is engaged by aesthetically pleasing stimuli that are processed efficiently and are perceived as harmonious [

33,

34]. It is important to highlight that while neurasthenic approaches provide valuable insight into brain mechanisms of aesthetic experience, behavioral studies focusing on perceptual principles remain essential to understanding how aesthetic judgments are formed in naturalistic viewing conditions [

22,

35]. This supports the behavioral approach of the present study, which emphasizes perceptual manipulation rather than direct neural measurement.

Among all conditions, the "no common fate asymmetry" variant elicited the strongest aesthetic penalty, significantly differing from all other versions. This is particularly revealing considering Gestalt principles, where common fate plays a crucial role in grouping and perceptual unity [

8]. Its disruption more severely interferes with the observer’s capacity to perceive visual coherence, thereby compromising aesthetic fluency. This effect supports the broader framework of processing fluency theory [

25], which argues that ease of perceptual processing positively contributes to aesthetic evaluation.

Symmetry is often associated with visual harmony, balance, and ease of processing, and it has been linked to positive aesthetic experiences across various cultures [

28]. Disrupting the symmetry of the mosaic, characterized in its intrinsic nature by a high degree of symmetry, violated this inherent preference for visual order and balance. Similarly, the principle of common fate, which suggests that elements moving or oriented in the same direction are perceived as belonging together, contributes to a sense of visual coherence. Disrupting this relationship by misaligning figures or altering their orientation can lead to a less unified and aesthetically pleasing composition [

8]. The distinct influence of the common fate principle observed here aligns with Gestalt research on grouping, underscoring its central role in perceptual coherence and aesthetic fluency[

36]. This aspect further underscores the hierarchical importance of different Gestalt principles in visual aesthetics.

From a neurasthenic perspective, these findings align with studies suggesting that the brain's reward system is engaged by aesthetically pleasing stimuli that are processed efficiently and are perceived as harmonious [

21]. Deviations from the preferred perceptual organization, induced by our modifications, may lead to less efficient processing and diminished activation of these reward pathways.

Another interesting pattern emerged in the chromatic domain. Although "no common fate symmetry" and "chromatic symmetric alteration" did not significantly differ, both were significantly distinct from all other conditions, indicating that color symmetry—even when altered—is less disruptive than outright chromatic imbalance, but more granular data on color perception would be needed. According to previous research [

32], these findings highlighted the aesthetic importance of color harmony. They suggest that spatial and chromatic organization contribute in an intertwined way to aesthetic perception.

Interestingly, the positive correlation between perceived pleasure reported for art-related hobbies and the aesthetic judgment of the original mosaic suggests that life experiences may drive top-down experiences with artistic works, even during a first viewing. Exposure to diverse visual stimuli could refine perceptual processing and increase the capacity for aesthetic appreciation [

37]. Such top-down modulations highlight how aesthetic experience is shaped not only by innate perceptual biases but also by learned expertise and cultural exposure, factors shown to enhance visual sensitivity and aesthetic discrimination [

38]. Furthermore, the consistency of the observed effects across both those familiar and unfamiliar with the specific mosaic underscores the fundamental and universal nature of these perceptual principles in shaping initial aesthetic responses. While prior familiarity might enhance overall appreciation, the basic impact of visual manipulations on perceived harmony and organization remains consistent.

Overall, the pattern of results reinforces the notion that aesthetic appreciation depends on an intricate balance between spatial and chromatic regularity, perceptual grouping, and structural coherence. While all manipulations reduced aesthetic ratings compared to the original, the degree of disruption varied depending on how fundamental the altered feature was to perceptual organization. Notably, alterations violating grouping principles like common fate appeared to have the most severe impact on aesthetic valuation due to their role in maintaining global coherence.

5. Limitations

While the controlled experimental approach employed in this study offers significant strengths, particularly in the precise manipulation of visual elements based on established Gestalt principles and using a complete aesthetic evaluation questionnaire, several limitations warrant consideration when interpreting the findings and considering their generalizability. Firstly, despite the unique contribution of utilizing a historical mosaic as the primary stimulus, this aspect introduces a potential limitation regarding the generalizability of our results to other fields. Moreover, only a single artwork—a mosaic from the Church of St. Agnes Outside the Walls—was used as the stimulus. While this choice allowed for controlled manipulation of specific Gestalt principles, it limits the generalizability of the findings to other sacred artworks or visual styles. Future research should incorporate a broader range of stimuli to test the robustness of these effects across different forms of sacred art and media. Moreover, the study relied on a composite score of exclusively positive adjectives. While this provided a clear index of positive aesthetic valence, it reduced psychological specificity and may limit construct validity. Future studies should employ validated multidimensional aesthetic scales and include negative or neutral descriptors. A further limitation concerns the interpretability of the Likert scale scores. Although the composite score provided statistical sensitivity, it does not allow a direct psychological interpretation of the absolute values (e.g., whether a rating reflects being less ‘beautiful’ or less ‘magnificent’). Future research should therefore employ validated multidimensional aesthetic scales that can capture distinct evaluative dimensions more precisely.

Secondly, expertise was not systematically assessed with validated instruments, limiting interpretability. Including participants with different levels of art expertise (e.g., art historians, artists) could provide further nuance. Including a more diverse participant pool, encompassing individuals with varying levels of art expertise, such as art history students or practicing artists, could have provided valuable insights into how expertise and specialized knowledge of art influence aesthetic judgments in response to these perceptual manipulations. As highlighted in our results, prior knowledge also plays a significant role in aesthetic appreciation. Comparing the responses of art experts with those of a general population sample could reveal more nuanced effects of Gestalt principles and the role of cognitive factors in aesthetic evaluation. Third, no psychophysiological or attentional measures (e.g., eye-tracking, neural data) were collected. While they were not included in the hypothesis and did not represent a focus of this study, such approaches would strengthen claims about underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, the study acknowledges that the exploring cultural influences on aesthetic judgments was not adequately addressed. While we recognize the impact of emotional states on aesthetic judgment [

15], this study did not extensively explore the participants' extended emotional states or personality dispositions as potential contributors to their aesthetic evaluations. Incorporating measures of emotional state could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between affective and perceptual factors in aesthetic responses. Finally, the static nature of the image presentation in this study represents a significant limitation. Future research could explore more dynamic or immersive presentation methods to gain a more ecologically valid understanding of aesthetic perception. Moreover, the results of the study clearly require deeper understanding and evaluation, including psychophysiological metrics, to identify characteristic correlations and eliminate distortions in surveys.