Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

DNA Standard Reference Material

Surface Water Sample Collection, Filtration, and DNA Extraction

Fecal Indicator Assays

QIAcuity Digital PCR

Absolute Q Digital PCR

Statistical & Visual Analysis

Results and Discussion

Precision, Analytical Sensitivity, Quantitative Agreement with Control Material

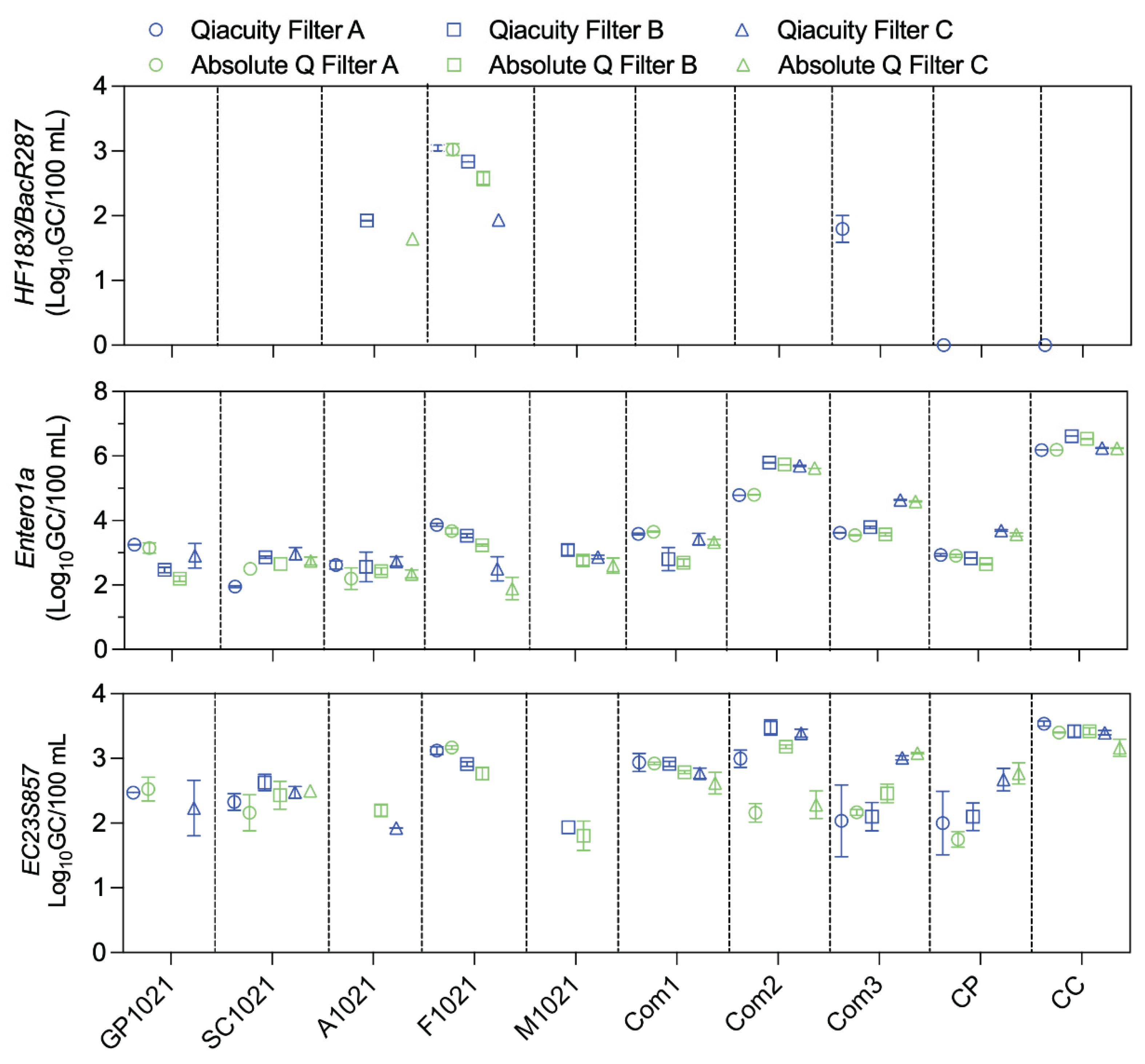

Qualitative and Quantitative Agreement with Water Samples

Study Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- Holcomb, D. A.; Stewart, J. R. Microbial Indicators of Fecal Pollution: Recent Progress and Challenges in Assessing Water Quality. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020, 7 (3), 311–324. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Grammer, P. Indicators of Microbial Quality *. In Routledge Handbook of Water and Health; Routledge, 2015.

- Haas, C. N. Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment and Molecular Biology: Paths to Integration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54 (14), 8539–8546. [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Method 1609.1: Enterococci in Water by TaqMan Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) with Internal Amplification Control (IAC) Assay; EPA-820-R-15-099; Office of Water: Washington, DC, 2015. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-08/documents/method_1609-1-enterococcus-iac_2015_3.pdf.

- US EPA. Method 1611: Enterococci in Water by TaqMan Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) Assay; EPA-821-R-12-008; 2012.

- Lane, M. J.; McNair, J. N.; Rediske, R. R.; Briggs, S.; Sivaganesan, M.; Haugland, R. Simplified Analysis of Measurement Data from A Rapid E. Coli qPCR Method (EPA Draft Method C) Using A Standardized Excel Workbook. Water 2020, 12 (3), 775. [CrossRef]

- Microbial Source Tracking: Methods, Applications, and Case Studies; Hagedorn, C., Blanch, A. R., Harwood, V. J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Boehm, A. B.; Van De Werfhorst, L. C.; Griffith, J. F.; Holden, P. A.; Jay, J. A.; Shanks, O. C.; Wang, D.; Weisberg, S. B. Performance of Forty-One Microbial Source Tracking Methods: A Twenty-Seven Lab Evaluation Study. Water Res. 2013, 47 (18), 6812–6828. [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Method 1696.1: Characterization of Human Fecal Pollution in Water by HF183/BacR287 TaqMan® Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) Assay; EPA 821-R-22-001; Office of Water, 2022; p 56. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-01/draft_method-1696.1-hf183_01052022_508.pdf.

- US EPA. Method 1697.2: Characterization of Human Fecal Pollution in Water by HumM2 TaqMan Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) Assay; EPA-821-R-23-010; 2023.

- Tiwari, A.; Ahmed, W.; Oikarinen, S.; Sherchan, S. P.; Heikinheimo, A.; Jiang, G.; Simpson, S. L.; Greaves, J.; Bivins, A. Application of Digital PCR for Public Health-Related Water Quality Monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 837, 155663. [CrossRef]

- Crain, C.; Kezer, K.; Steele, S.; Owiti, J.; Rao, S.; Victorio, M.; Austin, B.; Volner, A.; Draper, W.; Griffith, J.; Steele, J.; Seifert, M. Application of ddPCR for Detection of Enterococcus Spp. in Coastal Water Quality Monitoring. J. Microbiol. Methods 2021, 184, 106206. [CrossRef]

- US EPA Region 9. Re: REQUEST FOR CONCURRENCE TO IMPLEMENT ddPCR FOR BEACH WATER QUALITY RAPID DETECTION METHOD FOR RECREATIONAL BEACHES IN SAN DIEGO COUNTY, 2020. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2021-04/documents/epa_approval_of_ddpcr_beach_pilot-san-diego-c-10-06-2020.pdf.

- US EPA, O. EPA approves rapid test to assess beach water quality in San Diego County. https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-approves-rapid-test-assess-beach-water-quality-san-diego-county (accessed 2025-08-06).

- Willis, J. R.; Sivaganesan, M.; Haugland, R. A.; Kralj, J.; Servetas, S.; Hunter, M. E.; Jackson, S. A.; Shanks, O. C. Performance of NIST SRM® 2917 with 13 Recreational Water Quality Monitoring qPCR Assays. Water Res. 2022, 212, 118114. [CrossRef]

- Kralj, J.; Servetas, S.; Hunter, M.; Toman, B.; Jackson, S. NIST Special Publication 260-221: Certification of Standard Reference Material® 2917 Plasmid DNA for Fecal Indicator Detection and Identification; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2021; p 46. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.260-221.pdf.

- Green, H. C.; Haugland, R. A.; Varma, M.; Millen, H. T.; Borchardt, M. A.; Field, K. G.; Walters, W. A.; Knight, R.; Sivaganesan, M.; Kelty, C. A.; Shanks, O. C. Improved HF183 Quantitative Real-Time PCR Assay for Characterization of Human Fecal Pollution in Ambient Surface Water Samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80 (10), 3086–3094. [CrossRef]

- Haugland, R. A.; Siefring, S.; Lavender, J.; Varma, M. Influences of Sample Interference and Interference Controls on Quantification of Enterococci Fecal Indicator Bacteria in Surface Water Samples by the qPCR Method. Water Res. 2012, 46 (18), 5989–6001. [CrossRef]

- Chern, E. C.; Siefring, S.; Paar, J.; Doolittle, M.; Haugland, R. A. Comparison of Quantitative PCR Assays for Escherichia Coli Targeting Ribosomal RNA and Single Copy Genes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 52 (3), 298–306. [CrossRef]

- Huggett, J. F.; Foy, C. A.; Benes, V.; Emslie, K.; Garson, J. A.; Haynes, R.; Hellemans, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R. D.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M. W.; Shipley, G. L.; Vandesompele, J.; Wittwer, C. T.; Bustin, S. A. The Digital MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Digital PCR Experiments. Clin. Chem. 2013, 59 (6), 892–902. [CrossRef]

- Koo, T. K.; Li, M. Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15 (2), 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Crain, C.; Kezer, K.; Steele, S.; Owiti, J.; Rao, S.; Victorio, M.; Austin, B.; Volner, A.; Draper, W.; Griffith, J.; Steele, J.; Seifert, M. Application of ddPCR for Detection of Enterococcus Spp. in Coastal Water Quality Monitoring. J. Microbiol. Methods 2021, 184, 106206. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Sithebe, A.; Enitan, A. M.; Kumari, S.; Bux, F.; Stenström, T. A. Comparison of Droplet Digital PCR and Quantitative PCR for the Detection of Salmonella and Its Application for River Sediments. J. Water Health 2017, 15 (4), 505–508. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Smith, W. J. M.; Metcalfe, S.; Jackson, G.; Choi, P. M.; Morrison, M.; Field, D.; Gyawali, P.; Bivins, A.; Bibby, K.; Simpson, S. L. Comparison of RT-qPCR and RT-dPCR Platforms for the Trace Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in Wastewater. ACS EST Water 2022, 2 (11), 1871–1880. [CrossRef]

- Nshimyimana, J. P.; Cruz, M. C.; Wuertz, S.; Thompson, J. R. Variably Improved Microbial Source Tracking with Digital Droplet PCR. Water Res. 2019, 159, 192–202. [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Meng, Y.; Sui, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Fu, B. Comparison of Four Digital PCR Platforms for Accurate Quantification of DNA Copy Number of a Certified Plasmid DNA Reference Material. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5 (1), 13174. [CrossRef]

- Pavšič, J.; Žel, J.; Milavec, M. Assessment of the Real-Time PCR and Different Digital PCR Platforms for DNA Quantification. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408 (1), 107–121. [CrossRef]

- Crucitta, S.; Ruglioni, M.; Novi, C.; Manganiello, M.; Arici, R.; Petrini, I.; Pardini, E.; Cucchiara, F.; Marmorino, F.; Cremolini, C.; Fogli, S.; Danesi, R.; Del Re, M. Comparison of Digital PCR Systems for the Analysis of Liquid Biopsy Samples of Patients Affected by Lung and Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 541, 117239. [CrossRef]

- Samec, M.; Baranova, I.; Dvorska, D.; Biringer, K.; Kalman, M.; Pec, M.; Dankova, Z. Comparative Analysis of Two Digital PCR Platforms for Detecting DNA Methylation in Patient Samples. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2025, 43 (8), e70112. [CrossRef]

- Kløve-Mogensen, K.; Terp, S. K.; Steffensen, R. Comparison of Real-Time Quantitative PCR and Two Digital PCR Platforms to Detect Copy Number Variation in FCGR3B. J. Immunol. Methods 2024, 526, 113628. [CrossRef]

- Alikian, M.; Whale, A. S.; Akiki, S.; Piechocki, K.; Torrado, C.; Myint, T.; Cowen, S.; Griffiths, M.; Reid, A. G.; Apperley, J.; White, H.; Huggett, J. F.; Foroni, L. RT-qPCR and RT-Digital PCR: A Comparison of Different Platforms for the Evaluation of Residual Disease in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63 (2), 525–531. [CrossRef]

- Bivins, A.; Kaya, D.; Bibby, K.; Simpson, S. L.; Bustin, S. A.; Shanks, O. C.; Ahmed, W. Variability in RT-qPCR Assay Parameters Indicates Unreliable SARS-CoV-2 RNA Quantification for Wastewater Surveillance. Water Res. 2021, 203, 117516.

- Brooks, Y. M.; Spirito, C. M.; Bae, J. S.; Hong, A.; Mosier, E. M.; Sausele, D. J.; Fernandez-Baca, C. P.; Epstein, J. L.; Shapley, D. J.; Goodman, L. B.; Anderson, R. R.; Glaser, A. L.; Richardson, R. E. Fecal Indicator Bacteria, Fecal Source Tracking Markers, and Pathogens Detected in Two Hudson River Tributaries. Water Res. 2020, 171, 115342. [CrossRef]

- McMinn, B. R.; Korajkic, A.; Kelleher, J.; Diedrich, A.; Pemberton, A.; Willis, J. R.; Sivaganesan, M.; Shireman, B.; Doyle, A.; Shanks, O. C. Quantitative Fecal Pollution Assessment with Bacterial, Viral, and Molecular Methods in Small Stream Tributaries. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175740. [CrossRef]

- Zlender, T.; Rupnik, M. An Overview of Molecular Markers for Identification of Non-Human Fecal Pollution Sources. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Hart, J. J.; Jamison, M. N.; Porter, A. M.; McNair, J. N.; Szlag, D. C.; Rediske, R. R. Fecal Impairment Framework, A New Conceptual Framework for Assessing Fecal Contamination in Recreational Waters. Environ. Manage. 2024, 73 (2), 443–456. [CrossRef]

- Demeter, K.; Linke, R.; Ballesté, E.; Reischer, G.; Mayer, R. E.; Vierheilig, J.; Kolm, C.; Stevenson, M. E.; Derx, J.; Kirschner, A. K. T.; Sommer, R.; Shanks, O. C.; Blanch, A. R.; Rose, J. B.; Ahmed, W.; Farnleitner, A. H. Have Genetic Targets for Faecal Pollution Diagnostics and Source Tracking Revolutionized Water Quality Analysis Yet? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47 (4), fuad028. [CrossRef]

- Sivaganesan, M.; Willis, J. R.; Diedrich, A.; Shanks, O. C. A Fecal Score Approximation Model for Analysis of Real-Time Quantitative PCR Fecal Source Identification Measurements. Water Res. 2024, 255, 121482. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Baca, C. P.; Spirito, C. M.; Bae, J. S.; Szegletes, Z. M.; Barott, N.; Sausele, D. J.; Brooks, Y. M.; Weller, D. L.; Richardson, R. E. Rapid qPCR-Based Water Quality Monitoring in New York State Recreational Waters. Front. Water 2021, 3. [CrossRef]

- Yamahara, K. M.; Keymer, D. P.; Layton, B. A.; Walters, S. P.; Thompson, R. S.; Rosener, M.; Boehm, A. B. Application of Molecular Source Tracking and Mass Balance Approach to Identify Potential Sources of Fecal Indicator Bacteria in a Tropical River. PLOS ONE 2020, 15 (4), e0232054. [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, D. A.; Stewart, J. R. Microbial Indicators of Fecal Pollution: Recent Progress and Challenges in Assessing Water Quality. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020, 7 (3), 311–324. [CrossRef]

- Boehm, A. B.; Soller, J. A. Refined Ambient Water Quality Thresholds for Human-Associated Fecal Indicator HF183 for Recreational Waters with and without Co-Occurring Gull Fecal Contamination. Microb. Risk Anal. 2020, 16, 100139. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.; Jahne, M.; Keeling, D.; Gonzalez, R. The Effect of Sewage Source on HF183 Risk-Based Threshold Estimation for Recreational Water Quality Management. Microb. Risk Anal. 2024, 27–28, 100315. [CrossRef]

- The dMIQE Group; Huggett, J. F. The Digital MIQE Guidelines Update: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Digital PCR Experiments for 2020. Clin. Chem. 2020, 66 (8), 1012–1029. [CrossRef]

- Borchardt, M. A.; Boehm, A. B.; Salit, M.; Spencer, S. K.; Wigginton, K. R.; Noble, R. T. The Environmental Microbiology Minimum Information (EMMI) Guidelines: qPCR and dPCR Quality and Reporting for Environmental Microbiology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55 (15), 10210–10223. [CrossRef]

| SRM2917 (Dilution Levels) | HF183/BacR287 GC/rxn (CoV or PP)* |

Entero1a GC/rxn (CoV or PP)* |

EC23S857 GC/rxn (CoV or PP)* |

|||

| Qiacuity | Absolute Q | Qiacuity | Absolute Q | Qiacuity | Absolute Q | |

| Level 6 | 76.7 (10.8) | 73.4 (19.1) | 71.4 (29.6) | 69.0 (25.7) | 30.7 (20.2) | 33.6 (16.1) |

| Level 5 | 14.1 (38.0) | 11.2 (38.0) | 11.9 (57.5) | 12.2 (26.3) | 6.2 (38.5) | 4.0 (7/8) |

| Level 4 | 3.8 (7/8) | 0.9 (3/8) | 3.5 (16/20) | 2.4 (16/20) | 1.4 (4/8) | 0.6 (3/8) |

| Level 3 | 0.5 (2/8) | 0.1 (1/8) | 2.4 (13/20) | 1.5 (13/20) | 0.5 (2/8) | 0.3 (2/8) |

| Level 2 | 0.3 (1/8) | 0.3 (1/8) | 1.9 (11/20) | 1.4 (11/20) | 0.6 (2/8) | 0.3 (2/8) |

| Level 1 | 0 (0/8) | 0.1 (1/8) | 1.7 (11/20) | 1.2 (11/20) | 0.6 (2/8) | 0.1 (1/8) |

| dPCR Assays | 95% LOD (GC/rxn) (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Qiacuity | Absolute Q | |

| HF183/BacR287 | 6.54 (5.15 – 8.35) |

6.67 (3.24 – 14.0) |

| Entero1a | 6.83 (5.57 – 8.53) |

4.53 (1.86 – 17.4) |

| EC23S857 | 6.51 (2.72 – 22.5) |

10.2 (3.59 – 34.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).