1. Introduction

In supervised classification the primary objective is to learn a decision rule that minimizes classification error. The Bayes classifier is the theoretical optimum for this criterion when the true class–conditional distributions are known [Fukunaga/Kessell, 1973; Loizou/Maybank, 1987; Devroye et al., 2013]. In practice, however, estimating a nonparametric, potentially high-dimensional joint density is often infeasible [Bellman, 1961; Bernard W Silverman, 1998] and building a fully parameterized model to represent the joint distribution can be impractical [Duda et al., 2001].

Consequently, a variety of classifiers have been developed to address classification challenges in practical scenarios. Consequently, a wide range of pragmatic approximations has been developed. One class of methods is nonparametric instance-based learning: k-nearest neighbors (kNN) is conceptually simple and, with a suitable choice of k, is a consistent approximation to the Bayes rule as the sample size grows [Cover/Hart, 1967]. Another popular approach is the naïve Bayes classifier, which drastically reduces estimation complexity by assuming feature independence and often performs well despite this strong simplification [John/Langley, 1995; Duda et al., 2001]. Both kNN and naïve Bayes offer fast and straightforward alternatives to the more intricate Bayes classifier, though they may not always achieve the same level of performance.

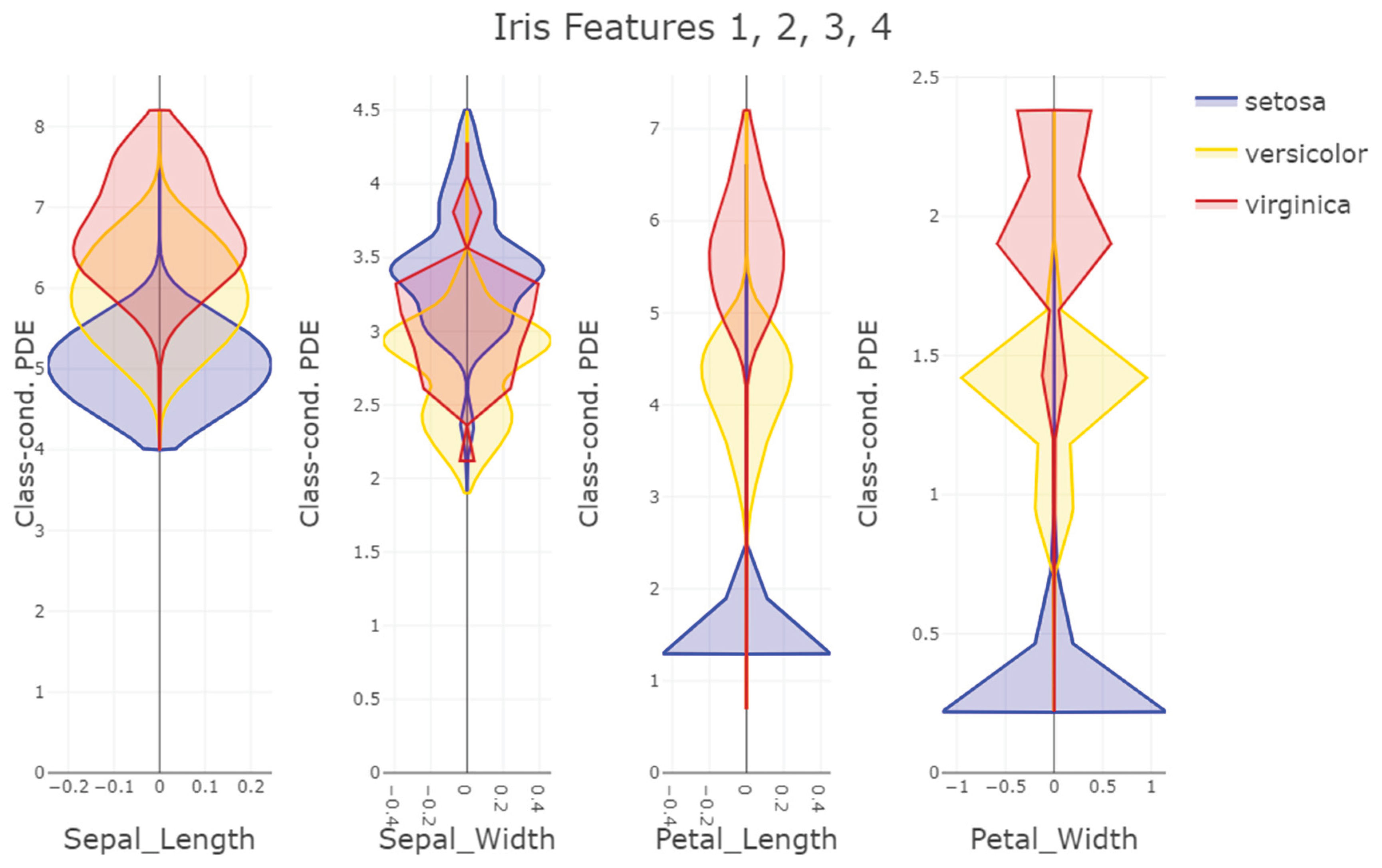

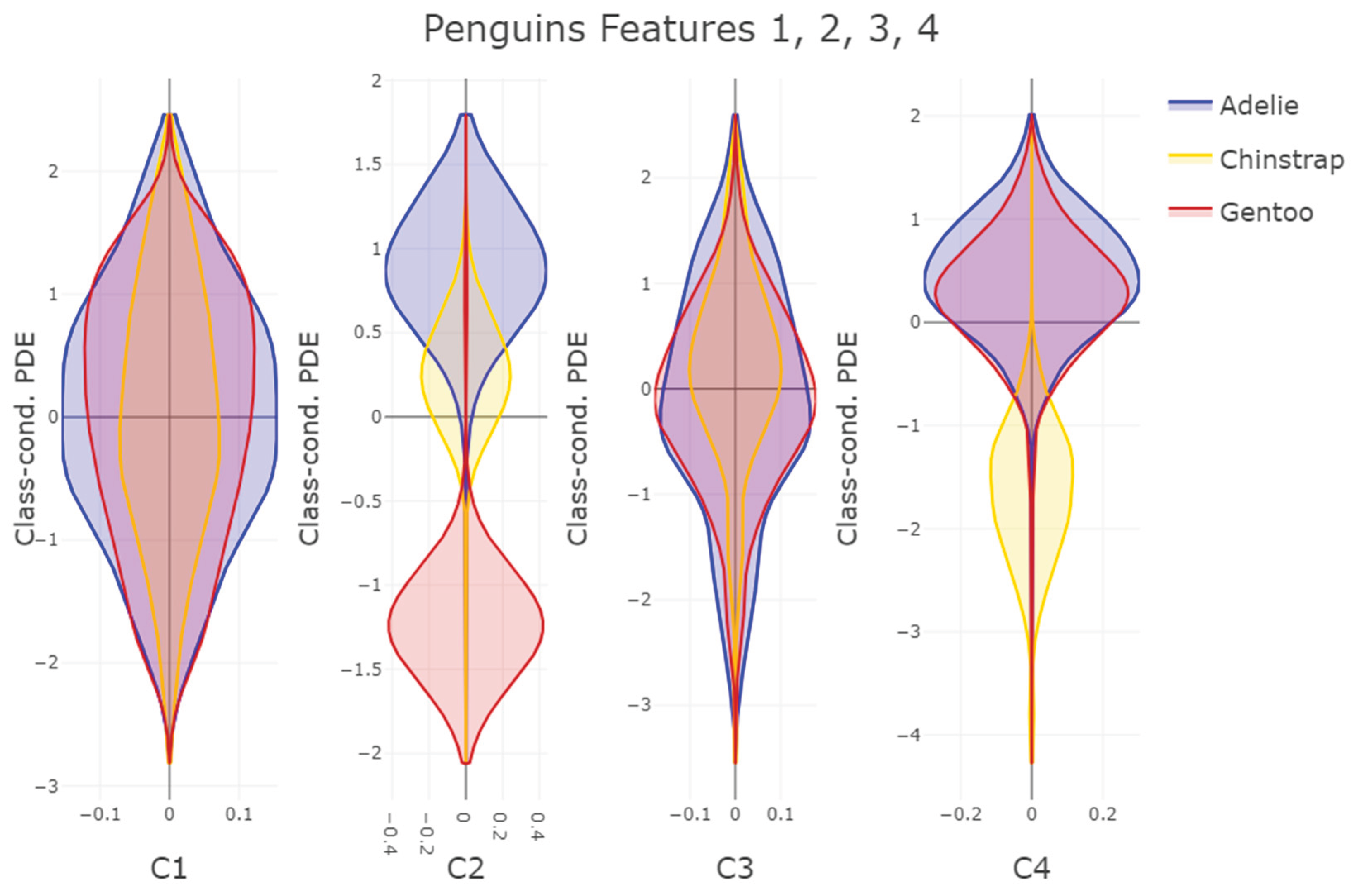

Therefore, the naïve Bayes and k-nearest neighbor (kNN) classifiers are commonly used as baseline algorithms for classification. However, in the case of naïve Bayes, the user must determine the most suitable strategy for model fitting based on the specific use case. Available strategies include fitting a mixture of Gaussian distributions or employing a non-parametric approach using kernel density estimation. However, these methods usually do not account for varying distributions across different features (e.g., see

Figure 2 and

supplementary C Figure C1 &C2 for varying feature distributions). Moreover, analyzing the distributions of all features to select the optimal strategy for a naïve Bayes classifier is a complex task. Similarly, for kNN, the user must choose an appropriate distance measure, which poses a similar complex decision [Thrun, 2021] as well as the number k of nearest neighbors.

Although this feature independence is quite constraining, naïve Bayes classifiers have been reported to achieve high performance in many cases [Domingos/Pazzani, 1997; Rish, 2001; Zaidi et al., 2013]. Interestingly, it has been observed that a naïve Bayes classifier might perform well even when dependencies exist among features [Rish, 2001] though correlation does not necessarily imply dependence [van den Heuvel/Zhan, 2022]. The impact of feature correlation on performance depends on both the degree of correlation and the specific measure used to evaluate it. Such performance-dependence relation can be effectively demonstrated by applying multiple correlation measures (see

Table 1). Likewise, the choice of class assignments to cases within a dataset also influences performance, which can be illustrated using a correlated dataset evaluated on two different classifications.

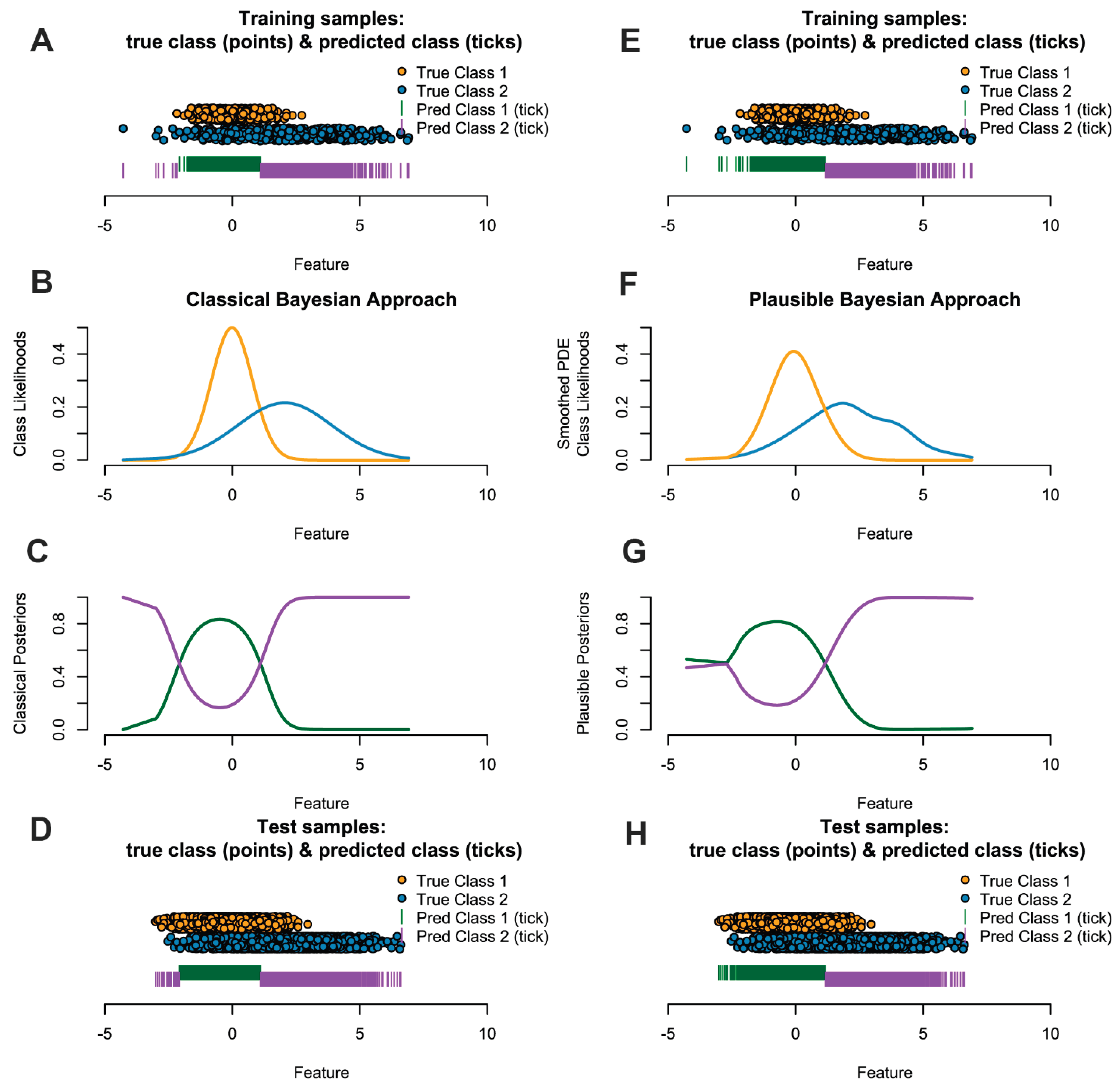

A pitfall in Bayesian theory occurs if observations with low evidence are assigned to a class with higher likelihood than another without considering that the probabilities of a probability density with higher variance decays slower than one with lower variance creating the situation that a class assignment chooses a far distant class with high variance over a closer class with smaller variance [Ultsch/Lötsch, 2022b]. An example for that would be the size of humans according to gender, where the females (Gaussian) distribution has higher variance than the males (Gaussian) distribution and the females mean is left of that of males. In that case, the classical Bayes theorem would assign a giant’s size to the class of females, since the likelihood of the males’ distribution would decay faster than that of the females. Instead, the closest mode could be chosen, if facing observations with low evidence (the giant size). As a consequence, the non-interpretable choice is to classify all giants as female.

Figure 1 outlines this situation for univariate on the left side and sketches influence of the flexible approach of smoothed Pareto density estimation (PDE) in combination with plausibility correction.

Figure 1.

Left (A-D) and right (E-H) panels show results on artificial data for the classical and plausible PDE-based naïve Bayes classifier, respectively. Each panel contains four rows: N=500 sampled points with predicted labels (A, H), class-conditional densities estimated from the training data (B, F), the posterior probability P(C1∣x) computed from the fitted model (C, G), and the test set of N=5000 points with its predictions (D, H). Because class 1 (dark green) has a smaller variance, its posterior decays in both tails and the MAP rule assigns extreme observations to class 2 in C; We argue to use the smoothed PDE to estimate the class likelihoods and the concept of Ultsch & Lötsch (2022) to correct assignments in regions of very low likelihood are not plausible in F. The right panel shows that the fine structure of disributions should be accounted for in the class likelihoods (F). Without prior knowledge, applying the left model C to the test data produces misclassifications relative to the true boundary and is less interpretable in comparison to G and H.

Figure 1.

Left (A-D) and right (E-H) panels show results on artificial data for the classical and plausible PDE-based naïve Bayes classifier, respectively. Each panel contains four rows: N=500 sampled points with predicted labels (A, H), class-conditional densities estimated from the training data (B, F), the posterior probability P(C1∣x) computed from the fitted model (C, G), and the test set of N=5000 points with its predictions (D, H). Because class 1 (dark green) has a smaller variance, its posterior decays in both tails and the MAP rule assigns extreme observations to class 2 in C; We argue to use the smoothed PDE to estimate the class likelihoods and the concept of Ultsch & Lötsch (2022) to correct assignments in regions of very low likelihood are not plausible in F. The right panel shows that the fine structure of disributions should be accounted for in the class likelihoods (F). Without prior knowledge, applying the left model C to the test data produces misclassifications relative to the true boundary and is less interpretable in comparison to G and H.

We are proposing a new methodology for the naïve Bayes classifier overcoming these challenges and improving performance. Our approach does not make any prior assumption about density distribution, creating an algorithm free of assumptions about the data distribution. Furthermore, we dispose any parameters to be optimized [Ultsch, 2005]. We use a model of density estimation based on information theory defined by a data-driven kernel radius without intrinsic assumptions about the data that outperforms typical density estimation approaches empirically [Thrun et al., 2020]. The main contribution of our work is:

Solution of the above-mentioned pitfall of the Bayes theorem within a Naïve Bayes classifier framework.

Empirical benchmark showing a robust classification performance of the plausible naïve Bayes classifier using the Pareto Density Estimation (PDE).

Visualization of the class-conditional likelihoods and posteriors to support model interpretability.

The aim of our work is to provide a classifier that can serve as a baseline. Hence, we will show that the performance of naïve Bayes is hard to associate with dependency measures and the design decisions are fluid across the degree of correlation and the choice of the correlation measure.

2. Materials and Methods

Let a classification } be a partition of a Dataset D consisting of N=|G| data points into k∈ℕ non-empty, disjoint subsets (classes) [Bock, 1974, p. 22]. Each class contains a subset of datapoints and each datapoint is assigned is a class label ∈{1,…,k} via the hypothesis function ℎ: D→{1,…,k}. The task of a classifier is to learn the mapping function h given training data and labels .

2.1. Bayes Classification

Assume a set of continuous input variables , with vector . In Bayesian classification, the prior is the initial belief (“knowledge) about class membership.

The Bayesian classifier picks the class whose posterior

has the highest probability

The posterior probability captures what is known about

, now that we have incorporated

. The posterior probability is obtained with the Bayes Theorem

Here

is the conditional probability of

given class

called class likelihood and the denominator is the evidence. Let H be the hypothesis space and

being a MAP hypothesis,

the (not necessarily i.i.d.) data set. A Bayes optimal classifier [Mitchell, 1997] is defined by

Equation 3 yields the optimal posterior probability to classify a data point in the sense that it minimizes the average probability error [Duda et al., 2001].

The general approach to Bayesian modeling is to set up the full probability model, i.e., the joint distribution of all entities in accordance with all that is known about the problem [Fukunaga/Kessell, 1971]. In praxis, given sufficient knowledge about the problem, distributions can be assumed for the and priors with hyperparameters θ that are estimated.

For the goal of this work of using a Bayesian classifier to measure a baseline of performance we make the assumption that the classification of the data point can be computed by the marginal class likelihoods

with

which is called the naive assumption because it assumes i.d.d. given the classification set G. In some domains the performance of a naive bayes classifier has been shown to be comparable to neural networks and decisions trees [Mitchell, 1997]. We will show in the results that for typical datasets, even if this assumption does not hold true, an acceptable baseline performance can be computed.

Our objective is to exploit the empirical information in the training set to derive, in a fully data-driven manner and under as few assumptions as possible, an estimate of each feature’s distribution within every class , and then to evaluate classifier performance on unseen test samples. To this end, we adopt a frequentist strategy: we estimate the class-conditional densities directly from the observed data, and we compute the class priors as the relative frequencies of each in the training sample—assuming that the sample faithfully represents the underlying population. Because our decision rule is given by Equation (4), which compares unnormalized scores across classes, the global evidence term (the denominator in Bayes’ theorem) may be treated as a constant and hence omitted.

The challenge is to estimate the likelihoods given the samples of the training data. However, by using the naive assumption, the challenge of estimating the -dimensional density is simplified to estimating one-dimensional densities. In prior works, the first naive bayes classifier using density estimation was introduced as flexible bayes [John/Langley, 1995]. This work improves significantly on the task of parameter-free univariate density estimation without making implicit assumptions about the data (c.f. [Thrun et al., 2020]).

2.2. Density Estimation

The task of density estimation can be achieved in two general ways. First, parametric statistics, meaning the fitting of parametrized functions as a superposition where the fitting can be done according to some quality measure or some sort of statistical testing. The drawback here is the rich possibility of available assumptions. A default approach could be the use of Gaussian distributions fitted on the data [Michal Majka, 2024]. Second, nonparametric statistics, meaning local parametrized approximations using neighboring data around each available datapoint. It varies in the use of fixed or variable kernels (global or local estimated radius). The drawback is the complexity in tuning bandwidths for optimal kernel estimation, which is a computational hard task [Devroye/Lugosi, 2000]. A default approach to solve this problem can be a Gaussian kernel where the bandwidth is selected according to the Silverman’s rule of thumb [Bernard W Silverman, 1998].

In this work, we want to solve the density estimation with the data-driven approach called Pareto Density Estimation (PDE) taken from [Ultsch, 2005]. In this way, any prior model assumption is dropped. The PDE is a nonparametric estimation method with variable kernel radius. For each available datapoint in the dataset, the PDE estimates a radius for estimating the density at this point. It uses a rule from information theory: The PDE maximizes the information content (reward) while minimizing the hypersphere radius (effort). Since this rule is historically known as Pareto rule (or 80-20-rule, reward/effort-trade-off), the method is called Pareto Density Estimation.

2.3. Pareto Density Estimation

Let a subset

of data points have a relative size is

. If there is an equal probability that an arbitrary point x is observed, then content is

. The optimal set size is the Euclidean distance of S from the ideal point, which is the empty set with 100% information [Ultsch, 2005]. The unrealized potential is

. Minimizing the

yields the optimal set size

. This set retrieves 88% of the maximum information [Ultsch, 2005]. For the purpose of univariate density estimation, the computation of the univariate Euclidean distance is required. Under the MMI assumption the squared Euclidian distances are χ-quadrat distributed [Ultsch, 2003] leading to

where

is the Chi-square cumulative distribution function for d degrees of freedom [Ultsch, 2005]. The pareto Radius is approximated by

for

.

The PDE is an adaptive technique for estimating the density at a datapoint following the Pareto rule (80-20-rule). The PDE is maximizing the information content using a minimum neighborhood size. It is well suited to estimating univariate feature distributions from sufficiently large samples and to highlighting non-normal characteristics (multimodality, skew, clipped ranges) that standard, default-parameter density estimators often miss. In an empirical study, Thrun et al. (2020) demonstrate that PDE visualizations (mirrored-density plots, short MD plot) more faithfully reveal fine-scale distributional features than standard visualization defaults (histograms, violin plots, and bean plots) when evaluated across multiple density-estimation approaches. Accordingly, PDE frequently yields superior empirical performance relative to commonly used, default-parameter density estimators. [Thrun et al., 2020].

Given the pareto radius R, the raw PDE can be estimated as discrete function solely at given kernel points

with

where 1 is an indicator function that is 1 if the condition holds and 0 otherwise, A normalizes

, and

a quantized function that is proportional to the number of samples falling within the interval [

-R,

+R].

For the mirrored-density (MD) plots used in Thrun et al. (2020), we previously applied piecewise-linear interpolation of the discrete PDE to fill gaps between kernel grid points and obtain a continuous visual approximation of a feature’s pdf While linear interpolation produces a visually faithful representation and is adequate for exploratory plots as it preserves continuity and is trivial to compute, it inherits the small-scale irregularities of the underlying discrete PDE estimate. If linearly interpolated densities are used directly as class-conditional likelihoods in Bayes’ theorem, that high-frequency noise propagates into the posteriors and can produce unstable or incorrect classifications.

Accordingly, in this work we therefore proceed as follows. After obtaining the raw and discrete conditional PDE ,we replace linear interpolation by several smoothing steps in the next section that produce a class likelihood which (i) preserves genuine distributional structure (modes, skewness, tails) and (ii) suppresses spurious high-frequency fluctuations that would destabilize posterior estimates.

2.4. Smoothed Pareto Density Estimation

Although the PDE of class likelihoods captures the overall shape of the distribution, it can be somewhat rough or piecewise-constant due to the uniform kernel and finite sampling. This is disadvantageous as irregular or noisy estimates yield fluctuating posteriors and unstable decisions. Therefore, smoothing the class likelihoods acts as a form of regularization: it suppresses sample-level noise and prevents high-frequency fluctuations like erratic spikes or dips in the likelihoods that lead to brittle posterior assignments. Balancing the fidelity to the PDE’s “true” features with removal of artificial high-frequency components results in more accurate approximations of the true underlying distributions leading to more reliable posterior estimates because they are less influenced by random sample noise.

For smoothing we exploit the insight, that the kernel estimate is a convolution of the data with the kernel by using fast Fourier transforms [Bernard W Silverman, 1998] p.61. To produce a smooth continuous density estimate, we convolve the PDE output with a Gaussian kernel using the Pareto radius as the bandwidth. Hence, the Gaussian smoothing kernel is defined as

where R is the pareto radius. We use the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), leveraging the convolution theorem in order to implement this convolution efficiently as follows.

First, we evaluate the Gaussian kernel on the same grid

as the PDE in which

is the number of grid points. Let

be the grid spacing, then the Gaussian kernel vector

yields a normalized kernel vector aligned with the PDE grid and we use the mean of adjacent differences to avoid numerical instabilities in spacing.

To perform a linear convolution without wrap-around artifacts, we zero-pad both the density and kernel vectors before FFT [Blackman/Tukey, 1958] (part1, p.260ff). We choose the padding length as the next power of two. This length ensures that circular convolution via FFT corresponds to the linear convolution of the original sequences, and using a power of two leverages FFT efficiency [Jones/Lotwick, 1984]. We create padded vectors (the with zero-pad) and ( with zeros zero-pad), each of length L. This padding avoids overlap of the signal with itself during convolution.

Next, we compute the FFT of both padded vectors, multiply them element-wise in the frequency domain, and then apply the inverse FFT. By the convolution theorem, the inverse FFT of the product

yields the linear convolution on the padded length. We divide by L in equation 9 when taking the inverse FFT, as per normalization convention.

The central elements correspond to the convolved density over the original grid. This middle segment is the smoothed density vector , aligned with the original kernel grid. The approach is motivated by the idea of [Bernhard W Silverman, 1982].

Finally, the montone Hermite spline approximation of [Fritsch/Carlson, 1980] yields the likelihood function . and allows for a functional fast computation of new points.

In sum, the empirical class PDE in a dimension can be rough due to the data being noisy. If used for visualization task, the roughness was inconsequential [Thrun et al., 2020]. In order to not influence the posteriors by data noise, we propose as a solution a combination of filtering by convolution (c.f. [Scott, 2015]) and monotonous spline approximation (c.f.[Bernard W Silverman, 1984]) yielding .

2.5. Plausible Naïve Bayes classification

Ultsch and Lötsch showed that misclassification can occur when only low evidence is used in the Bayes’ theorem, i.e., the cases lie below a certain threshold ε. They define cases below ε as uncertain and provide two solutions [Ultsch/Lötsch, 2022b]: reasonable Bayes (i.e. suspending a decision) and plausible Bayes (a correction of equation 4). To derive ε they propose the use of the computed ABC-analysis [Ultsch/Lötsch, 2015]. The algorithm allows to compute precise thresholds that partition a dataset into interpretable subsets.

Closely related to the Lorenz curve, the ABC curve graphically represents the cumulative distribution function. Using this curve, the algorithm determines optimal cutoffs by leveraging the distributional properties of the data. Positive-valued data are divided into three disjoint subsets: A (the most profitable or largest values, representing the 'important few'), B (values where yield matches effort), and C (the least profitable or smallest values, representing the 'trivial many').

Let

be a set of n observations which for the purpose of defining the plausible Naïve Bayes likelihoods in dimension

are indexed in non-decreasing order in the respective dimension, i.e.,

, let

, the

is defined by [Gastwirth, 1971] as

For all other p in [0,1] with p ≠ pi, L(p) is calculated using some linear, spline or other suitable interpolations on [Gastwirth/Glauberman, 1976].

Let L(p) be the Lorenz curve in equation 11 then the ABC curve is formally defined as

Then the break-even point satisfies

and the submarginal point

is located by minimizing the distance from the ABC curve to the maximal-yield point at (1,1) after passing the break-even point with

. The break-even point yields the BC limit, and, hence, the threshold

ε with

Equation 12 defines the BC-Limit.

Inspired by their idea, we reformulate the computation of epsilon from posterior to joint likelihood as follows. An observation

is considered uncertain in feature

whenever the joint likelihood every class falls below the confidence threshold ε, i.e.

where

denotes the marginal of the distribution in dimension

. We will apply the threshold ε to identify low-evidence regions where the plausibility correction (Eq. 15) may be considered. Such uncertain cases might be classified against human intuition to a class with a probability density center quite far away despite closer available class centers [Ultsch/Lötsch, 2022b]. Then a “reasonable” assignment might be to assign the case to the class whose probability centroid is closest which can be calculated using Voronoi cells for d>1. For the one-dimensional case they propose the closest mode could be determined for classifying such cases.

We estimate the univariate location of each class likelihood’s mode on a per-feature basis using the half-sample mode [Bickel/Frühwirth, 2006]. For small sample sizes (n < 100) we use the

estimator recommended by [Ekblom, 1972]. As a safeguard mechanism, estimated modes are only considered for resolving uncertain cases if they as well-separated, i.e., have a distance from each other of at least the 10th percentile within the training data

This mechanism is motivated by the potential presence of inaccurately estimated modes or overlapping (non-separable) classes.

When the class likelihood for an observation x is uncertain in feature (Eq. 13 holds true) and there is a class whose mode is well-separated from the highest-likelihood class (Eq. 14), we perform a conservative, local two-class correction of that feature class likelihoods as follows:

Let be the index of the uncorrected class likelihood with the largest value and the index of the class likelihood with closest mode to for which equation (14) hold true for and .

Then we update the two involved class likelihoods by replacing the values of the class likelihood

with the (former) top class likelihood

. In addition, the operation subtracts δ from the prior top likelihood

and adds δ to the runner-up

, the relative advantage of the runner-up versus the former top increases by 2δ, which is sufficient to resolve many marginal posterior ties or implausibilities (as shown in the example in figure 1) while remaining conservative. All other class likelihoods for this feature remain in Eq. 15 unchanged:

Equation 4 is then used with the locally corrected class likelihoods . Note that as the correction vanishes and the method reduces to the reasonable-Bayes rule; the transfer introduces a conservative “plausible-Bayes” adjustment, with controlling the strength of the plausibility correction.

2.6. Practical Considerations

In order to avoid numerical overflow, equation (4) with uncorrected or the with the locally corrected class likelihoods

can be computed in log scale

to select the label of the class

that with the highest probability.

In praxis, before this function can be computed, it must be determined if there are enough samples to yield a proper PDE. Based on empirical benchmarks [Thrun et al., 2020], if there are more than 50 samples and at least 12 uniquely defined samples, then then can be estimated, otherwise the estimations might deviate. In case of too few samples, the density estimation defaults to simple histogram binning with bin width defined by Scott`s rule [Keating/Scott, 1999].

Let be a small constant, then to ensure numerical stability in equation 16, the likelihoods are clipped to the range of . The reason is, that density after smoothing may result in values slightly below zero due to the convolution (c.f. [Bernard W Silverman, 1998]). In addition, density estimation can have spikes above 1. Moreover, we ensure numerical safety if we clip the corrected likelihoods to be non-negative after applying equation (15).

There is also a possibility that equation 4 may not allow a decision as two or more posteriors equal each other after the priors are considered. In such a case, the class assignment is randomly decided.

Equation (15) foundation is the assumption that modes can be estimated correctly in the data per class which could fail in praxis. As a safeguard, we provide for the user the following option. We compute the classification assignments as defined in Equation (4), transformed according to Equation (16), and likewise without correction , both using the training data.

Assuming the priors are not excessively imbalanced, we evaluate the Shannon entropy of each classification result

and choose the configuration that yields the highest entropy. The Shannon entropy H of

with priors

for

is defined as

with the normalization factor

.

A higher entropy indicates a potentially more informative classification.

Finally, due to the assumption leading to equation (4) and subsequent equations, we provide a scalable multicore implementation of the plausible bayes classifier by computing every feature separately proceeding as follows: For each feature dimension we estimate a single Pareto radius independent of class as defined in Equation (5) rather than separately for each feature-class combination. Empirical evaluations indicate that this approximation is sufficiently accurate for practical applications. For each class in each dimension we compute the class-wise PDE on an evenly spaced kernel grid to compute the raw conditional PDE covering the range of the data. Then, we compute the smoothed likelihood functions per feature dimension from the discrete conditional PDE . We call this approach the Plausible Pareto Density Estimation based flexible Naïve Bayes classifier (PDENB).

2.7. Interpretability of PDENB

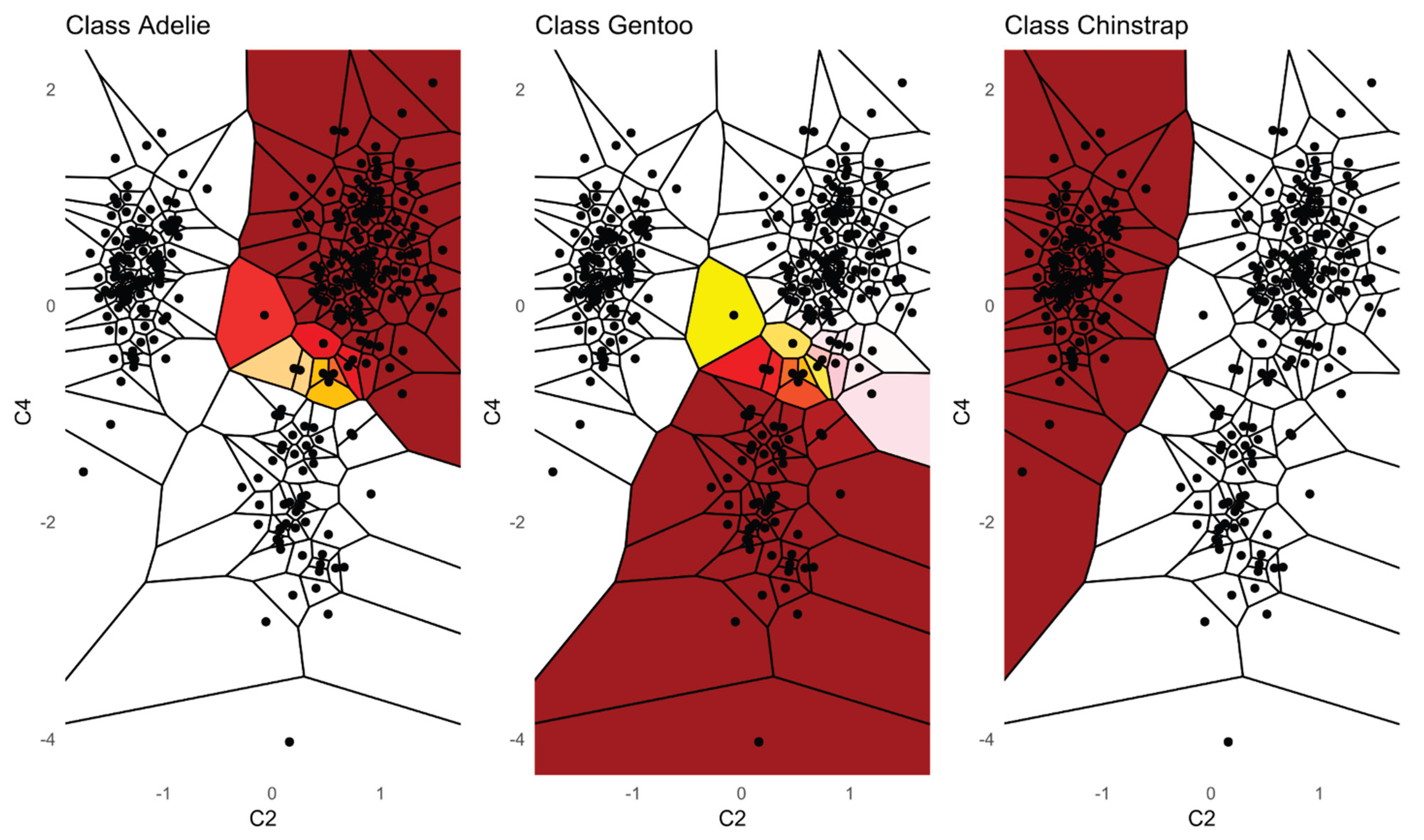

The one-dimensional density estimation required for the Naïve Bayes Classifier to compute the class-conditional likelihood of a feature as one of three parts of the Bayes theorem yielding the final Posterior. This class-conditional likelihood allows a two-dimensional visualization as a line plot for a single feature. The plot gives insight into the class-wise distribution of the feature. Scaling the likelihoods with the weight of the prior obtained from the frequentist approach [Duda et al., 2001] yields the correct probabilistic proportions between the class-conditional likelihoods which can be represented by different colors. Rotating the plots by 90 degrees and mirroring similar than for violin and mirrored density plots [Thrun et al., 2020] allows the lineup of the likelihoods for multiple features at once. Such visualization allows interpretation based on the class-wise distribution of features. Most likely, the colored class conditional likelihoods are overlapping and non-separable by solely one feature. However, in case of a high performing Naïve Bayes Classifier, overlaps do not indicate non-separability, but rather first of all a class tendency for each feature and second the existence of certain combinations and a disqualifier for other combinations in question. These visual implications can be the starting point for a domain expert to find relations between features and classes resulting in explanations.

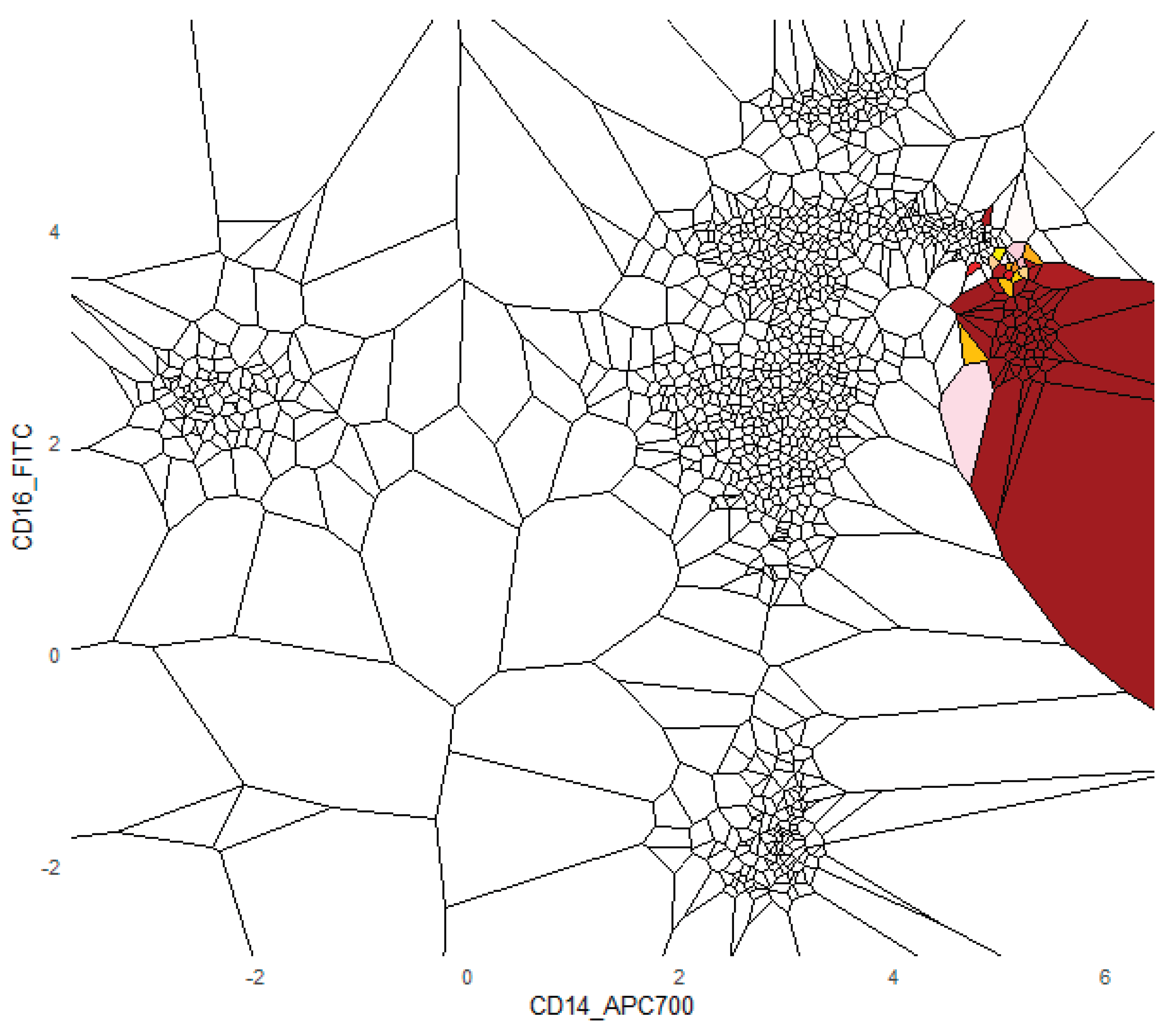

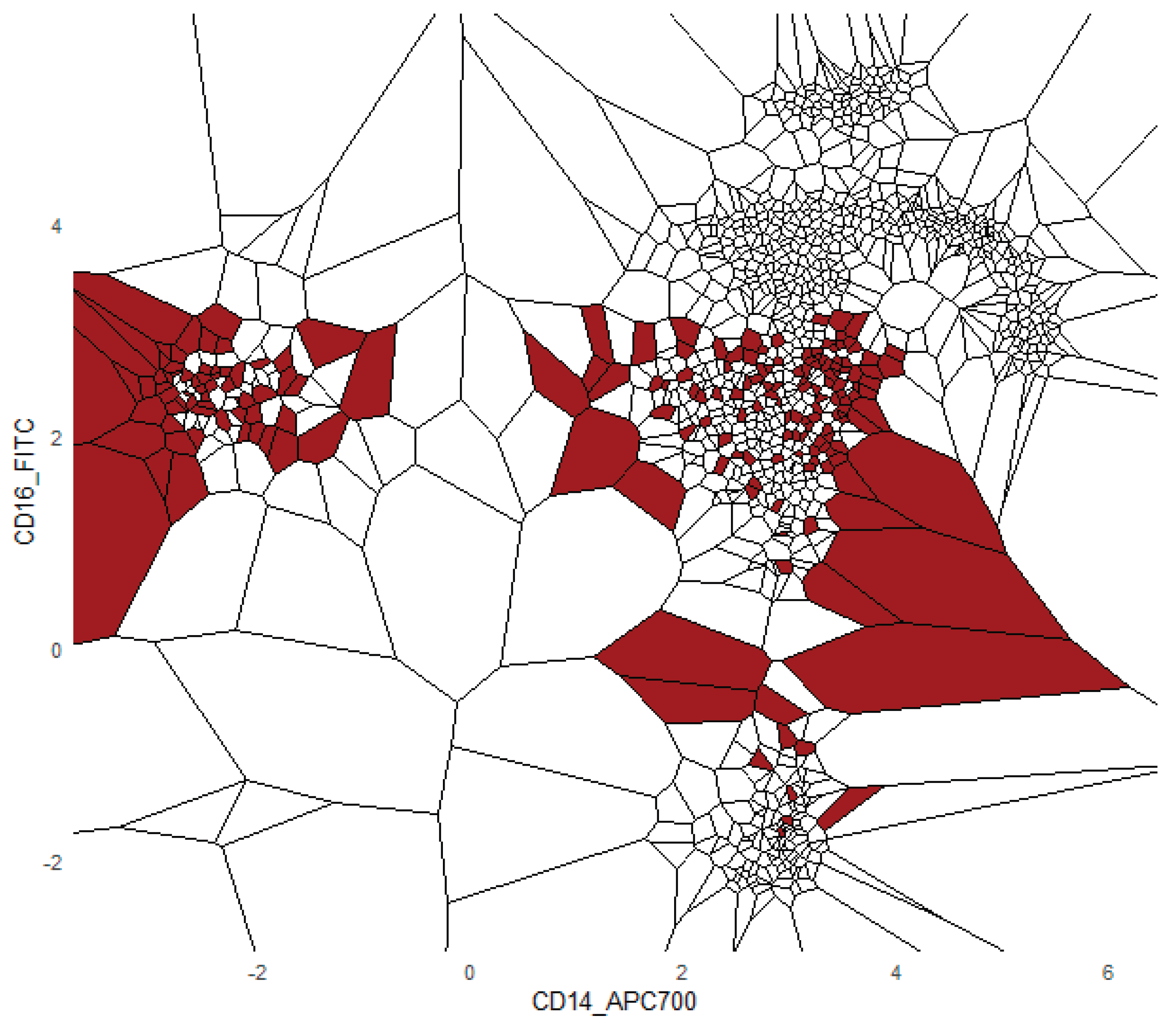

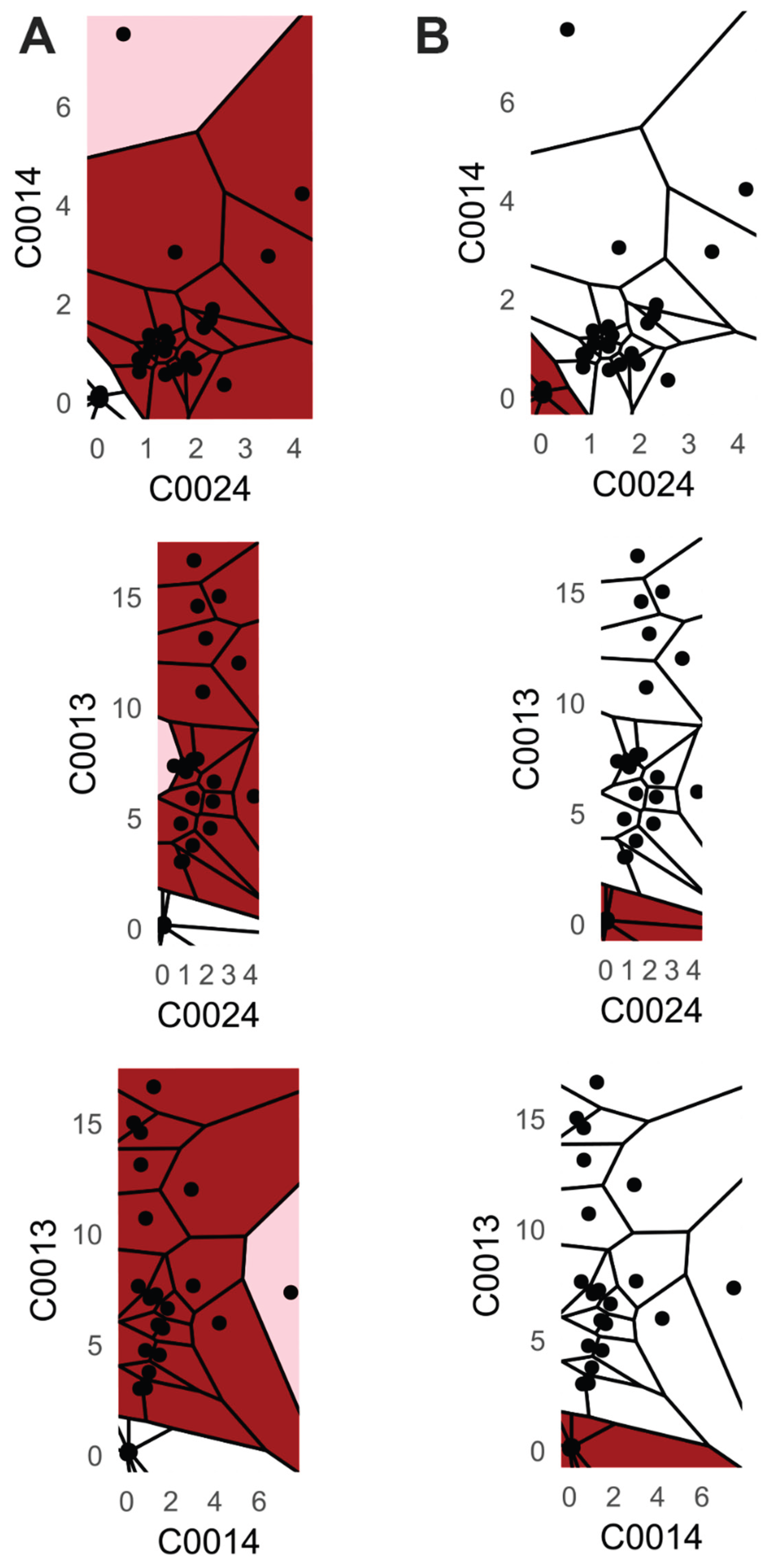

Additionally, we provide a visualization of one class versus all decision boundaries in 2D as follows. Given a two-dimensional slice

, the Voronoi cell associated with a point g

is the region of the plane consisting of all points that are closer to g than to any other point v in the slice is defined by

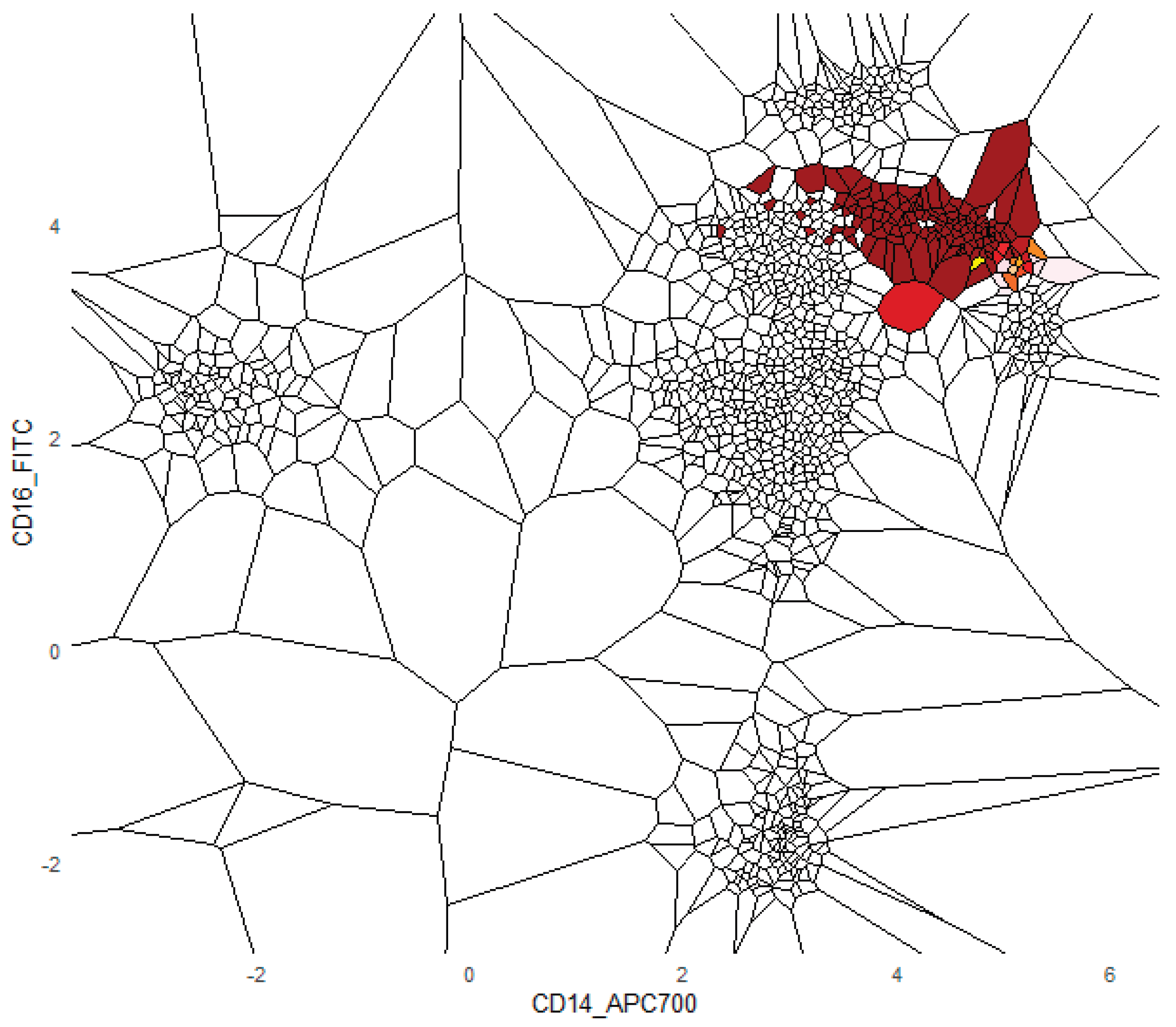

That is, contains all points such that the Euclidean distance from any y to g is less than or equal to the distance to any other v. Each Voronoi cell according to the binned posterior probability , thereby mapping regions of the plane to their inferred class likelihoods by colors. The binning can be either performed equally sized using Scotts rule as bin width [Keating/Scott, 1999] or less efficiently by the DDCAL clustering algorithm [Lux/Rinderle-Ma, 2023]. The user can visualize the set of slices of interest. This approach is motivated by human pattern recognition and subsequent disease classification of identified patterns in two-dimensional slices of data [Shapiro, 2005] that apparently is sufficient for a large variety of multivariate data distributions.

2.8. Benchmark Datasets and Conventional Naïve Bayes Algorithms

For the benchmark we selected 14 datasets: 13 from the UCI repository and a fourteenth dataset (“Cell populations”) containing manually identified cell populations [Plank et al., 2021]. Full dataset descriptions of the UCI datasets, attribute definitions and links to original sources are available on the repository pages for each dataset [Dua/Graff, 2019], for example or example,

Iris:

https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/iris). The Cell populations dataset is an extended version of the data used by Plank, Dorn & Krause (2021); the set of populations provided here is larger than in that publication because the authors labeled populations at finer granularity. A detailed description of the cell populations dataset is given in Plank et al. (2021).

The datasets were preprocessed priorly using methods rotation [Pearson, 1901; Hotelling, 1933] drawing [Karlis et al., 2003; Harmeling et al., 2004] as implemented in “ProjectionBasedClustering” available on CRAN [Thrun/Ultsch, 2020]. In it should be noted that although to the cell populations the signed log transformation for better interpretability was applied, no Euclidean optimized variance scaling was used[Ultsch/Lötsch, 2022a]. Thereafter, correlations of features were computed. Important properties and meta information, and correlations of the processed datasets are stated in table 1. The measure of correlation depends on the choice of algorithm. Here, the Pearson, Spearman’s rank, Kendall’s rank and the Xi correlation coefficient [Chatterjee, 2021] are summarized using the minimum and maximum value to characterize the correlations of the datasets. The values of the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficient tend to be higher than the Xi correlation coefficient by around 0.3. Similarly, Kendall’s Tau values tend to be higher than the Xi correlation coefficients but not as high as the Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Important attributes are the number of classes, the distribution of cases per class to judge class imbalance and various dependency measures related to the independent feature assumption of the naïve Bayes classifier are presented in table 1.

The performance is evaluated for the Plausible Pareto Density Estimation based flexible Naïve Bayes classifier (PDENB) in comparison to a Gaussian naïve Bayes classifier (GNB) and a nonparametric naïve bayes classifier (NPNB) from the R package “naivebayes” available on CRAN [Michal Majka, 2024]), a fast implementation of k-nearest neighbor classifier (kNN) from the R package “FNN” available on CRAN [Li, 2024]), a Gaussian naïve Bayes from the python package “sklearn” [Buitinck et al., 2011], a Gaussian and non-parametric naïve Bayes approach from the R package “klaR” available on CRAN [Roever et al., 2023], and last but not least a Gaussian naïve Bayes from the R package “e1071” available on CRAN [Meyer et al., 2024]. The algorithms for the naïve bayes methods were applied in their default settings differencing between “Gaussian” and “nonparametric” versions, while the parameter k for the kNN classifier is set to 7.

4. Discussion

We introduced PDENB, a Pareto Density–based Plausible Naïve Bayes classifier that combines assumption-free, neighborhood-based density estimation with smoothing and visualization tools to produce robust, interpretable classification. Our empirical benchmark across 14 datasets and the dedicated application to multicolor flow-cytometry demonstrate several consistent advantages of this approach.

First, PDENB is competitive with — and frequently superior to — established Naïve Bayes implementations and non-parametric variants. Using repeated 80/20 hold-out evaluations (or resampling for very large datasets) and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) as the performance measure, PDENB attains top average ranks (

Table 3) and achieves very high per-dataset performance on several problems (e.g., MCC

0.95 for Iris, Penguins, Wine, Dermatology, and the Cell populations dataset). The permutation tests (with multiple-comparison correction) aggregated in

Table 3 indicate that these improvements are not merely random fluctuations: they translate into statistically detectable differences for many dataset–classifier pairs (see also supplementary B1–B2). Note that we did not apply variance-optimized feature scaling for the benchmark; because k-nearest neighbors’ decisions are distance-based, kNN is therefore not expected to attain its best possible performance under our preprocessing. Choice of a scaling and distance is often empirical and context-dependent and there is no single universally “correct” recipe.

Second, PDENB’s core strength is its flexibility in modeling complex, non-Gaussian feature distributions without parametric assumptions. The Satellite dataset illustrates this point: feature distributions (see supplementary C) and class-conditional distributions there display long tails, multimodality and skewness that violate Gaussian assumptions. In that setting PDENB captures the fine structure that classical Gaussian Naïve Bayes misses, yielding substantially better discriminative performance. This example underscores the value of highly adaptive density estimation methods when confronted with complex, non-Gaussian data structures. This pattern — non-parametric methods outperforming Gaussian approximations when data depart from normality — is borne out across the benchmark: non-parametric Naïve Bayes variants tend to outrank their Gaussian counterparts (see

Table 2).

Third, PDENB directly supports interpretability through visualization. The class conditional mirrored-density (MD) plots and the customized 2D Voronoi posterior maps provide intuitive, feature-level and case-level explanations as outlined using

Figure 2-5: users can inspect class-conditional likelihood shapes (modes, skewness, overlaps) and identify the feature combinations that produce compact, high-posterior decision areas. These visual diagnostics do not replace formal model evaluation, but they materially aid exploratory analysis and hypothesis generation, and they help explain why a particular prediction was made in cases where two or more features jointly determine a compact posterior region (see

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

The FlowCytometry application of distinguishing blood vs bone marrow illustrates a practical use case where PDENB’s combination of sensitivity to distributional fine structure, feature selection, and interpretability is valuable. In such features of cell population frequencies, absolute counts, and percentages classical Gaussian assumptions are violated (see supplementary C

Figure 2 and 3). PDENB achieved 98.8 MCC under cross-validation. The improved baseline performance is practically meaningful because higher sample-level accuracy reduces the risk of mislabeling the origin of aspirates of bone marrow vs peripheral blood, which in turn can reduce downstream diagnostic errors. This result is a first indication that PDENB could potentially support clinically relevant classification tasks even with modest sample sizes, provided that careful feature selection and validation are applied.

The influence of dependency was tracked with four different measures in

Table 1 after preprocessing. High correlation values (>0.8) using all four measures are depicted in Table1 for all datasets except for the three: CoverType, Swiss, and Wine (Crabs and Penguin had low correlations due to rotation by ICA or PCA). Although naïve Bayes theoretically assumes feature independence. In practice correlated features did not necessarily imply a low performance (<0.8). For example, the Cell populations dataset retained high performance despite correlated features above 0.9. Plain removal of correlated features did not necessarily improve performance. Still, correlations can affect interpretability and sometimes classifier reliability; feature decorrelation, conditional modeling, or methods that explicitly capture dependencies may further improve performance in specific domains. In our benchmark, we observed that high feature correlation does not uniformly impair PDENB.

Our benchmark covers a diverse but limited set of datasets; broader evaluations — especially in high-dimensional, noisy, or highly imbalanced settings — would strengthen generality claims although benchmarking against all families of classifier is a controversial topic [Fernández Delgado et al., 2014; Wainberg et al., 2016]. We emphasize several methodological points and caveats. PDENB’s robust performance hinges on three design choices: (i) estimating a single, class-independent Pareto radius per feature; (ii) applying smoothing to the raw class-conditional PDE output prior to using it as a likelihood; and (iii) applying a plausibility correction to the class likelihoods. While these design choices increase estimator stability and interpretability, they come at the cost of greater computational demand. To mitigate the computational cost, we provide a multicore, shared-memory[Thrun/Märte, 2025] implementation for large-scale applications. Finally, embedding PDENB visualizations within formal explainable-AI workflows (e.g., counterfactual analyses, local-explanation wrappers) would enhance their utility for decision-makers.

The advantage of the PDENB is clearly the assumption-free modeling of the data and its robust performance. PDENB can be applied to data and leverage fine details of the distributions. Its assumption-free smoothed density estimation, combined a plausibility correction of the Bayes theorem, yields reliable and robust posterior estimates. Patterns made of multiplicative combinations of different features can be recognized by the user and serve as an explanation for relations between the input data and its classification.