1. Introduction

Carbon neutrality refers to the 'Net-Zero' concept where net emissions from human activities become '0' to prevent the increase of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, and various policies are being pursued at the national level with the goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 [

1]. In the field of environmental engineering, including wastewater treatment, research on new wastewater treatment systems is being conducted to achieve carbon neutrality by reducing the required electrical energy while meeting effluent water quality standards, or by maximizing the conversion of organic matter (Chemical Oxygen Demand, COD), a potential energy source in wastewater, into biogas[

2,

3,

4]. Future-oriented wastewater treatment toward carbon neutrality is shifting from simple pollutant removal to an energy-positive direction that can actively produce and recover the energy potential in wastewater. To achieve this, it is necessary to reduce the amount of CO

2 generated in biological wastewater treatment processes and expand technologies that maximize the production of primary sludge and excess sludge for energy recovery[

5]. The Strass wastewater treatment plant in Austria achieved 'energy-positive' status through co-digestion technology, and by additionally applying heat-pump technology, was able to implement a stable 'energy-positive' wastewater treatment plant that could produce more than 180% of the energy required for the wastewater treatment plant [

6].

To maximize the recovery of energy potential from sewage and wastewater, it is necessary to reduce CO

2 generation due to oxidation in bioreactors and the amount of excess sludge with low biodegradability, while securing as much primary settled sludge with high biodegradability as possible. Biological wastewater treatment processes consume approximately 1,080-2,160 kJ/m³ of electrical energy, and assuming that the primary sludge recovery rate from primary clarifiers is 60% in terms of COD, approximately 1,158 kJ/m³ of energy can be recovered, and if 80%, approximately 1,398 kJ/m³ of energy can be recovered, enabling energy-neutral wastewater treatment [

7]. Additionally, by applying the Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation (ANAMMOX) process to remove ammonia nitrogen, approximately 65% of aeration energy can be reduced, requiring only about 810-1,620 kJ/m³ of energy for wastewater treatment including nitrogen removal, making energy-positive wastewater treatment feasible[

5].

Approximately 50-60% of the electrical energy required for biological wastewater treatment processes is consumed during the oxygen supply (aeration process) for microbial cultivation. To reduce this, COD in the influent wastewater must be removed in the primary clarifier before entering the aeration tank, which is an aerobic biological reactor, or the sludge residence time (SRT) of microorganisms must be controlled. Various efficient alternatives such as Chemical Enhanced Primary Treatment (CEPT) [

8,

9] or High Rate Activated Sludge (HRAS) [

10,

11] processes have been proposed to efficiently remove and separate COD from wastewater. The HRAS process showed lower Total COD (TCOD) recovery efficiency but higher separation efficiency for low molecular weight soluble COD (SCOD) that is difficult to separate by sedimentation [

12]. HRAS has lower TCOD removal efficiency than CEPT because some COD is biologically converted to carbon dioxide and biomass during the aeration process [

13]. Cagnetta et al [

14] proposed a chemical post-treatment method following HRAS as the optimal alternative for effectively separating and recovering COD from wastewater.

CEPT is a representative method for effectively separating TCOD from wastewater through chemical coagulation. Alum (Al₂(SO₄)₃·18H₂O), Poly Aluminum Chloride (PAC), and ferric chloride are used as coagulants for chemical precipitation in wastewater treatment, and polyacrylamide is used as a coagulation aid. Although ferric chloride has lower organic matter removal efficiency than PAC, it is known to improve methane production efficiency by participating in oxidation-reduction reactions during acid production and methane production processes in anaerobic digestion [

15,

16]. CEPT can remove approximately 50-80% of Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD₅) and 80-95% of phosphorus through chemical precipitation [

17,

18,

19]. However, chemical precipitation has the limitation of being effective for separating particulate COD larger than colloidal particles but not efficient for removing SCOD with small particle sizes [

20]. The highly biodegradable SCOD in wastewater can be easily removed as a carbon source required for the denitrification process of NO₃⁻. By converting SCOD to particulate COD (VSS) through denitrification reactions that utilize NO₃⁻ as the final electron acceptor and removing it together with particulate COD in CEPT, maximum separation and recovery of TCOD from influent wastewater can be achieved.

To reduce electrical energy while removing COD along with nitrogen, processes such as CEPT combined with Completely Autotrophic Nitrogen Removal Over Nitrite (CANON) [

21,

22] and Partial Nitrification/ANAMMOX (PN/A) [

23,

24,

25] have been proposed. In such wastewater treatment processes, the PN/A process for nitrogen removal is highly efficient under conditions with low COD/N (C/N) ratios, making the CEPT process necessary, and the optimal SCOD/N ratio for influent wastewater is proposed to be less than 2-3 [

26,

27].

To increase TCOD removal efficiency in CEPT, coagulants (ferric chloride) can be injected [

28], or biological denitrification reactions can be utilized [

29]. Park et al. [

29] achieved approximately 90% TCOD removal at a 300% recycle ratio in a primary clarifier-nitrification tank combined wastewater treatment process without coagulant dosage. This was attributed to the simultaneous removal of particulate organic matter in the microbial sludge layer formed during denitrification reactions. The NO₃⁻ required for denitrification reactions in CEPT can be supplied by oxidizing NH₄⁺ to NO₃⁻ in the subsequent nitrification reactor and returning the required amount, and TCOD removal efficiency can be expected to increase through chemical coagulation and biological denitrification reactions.

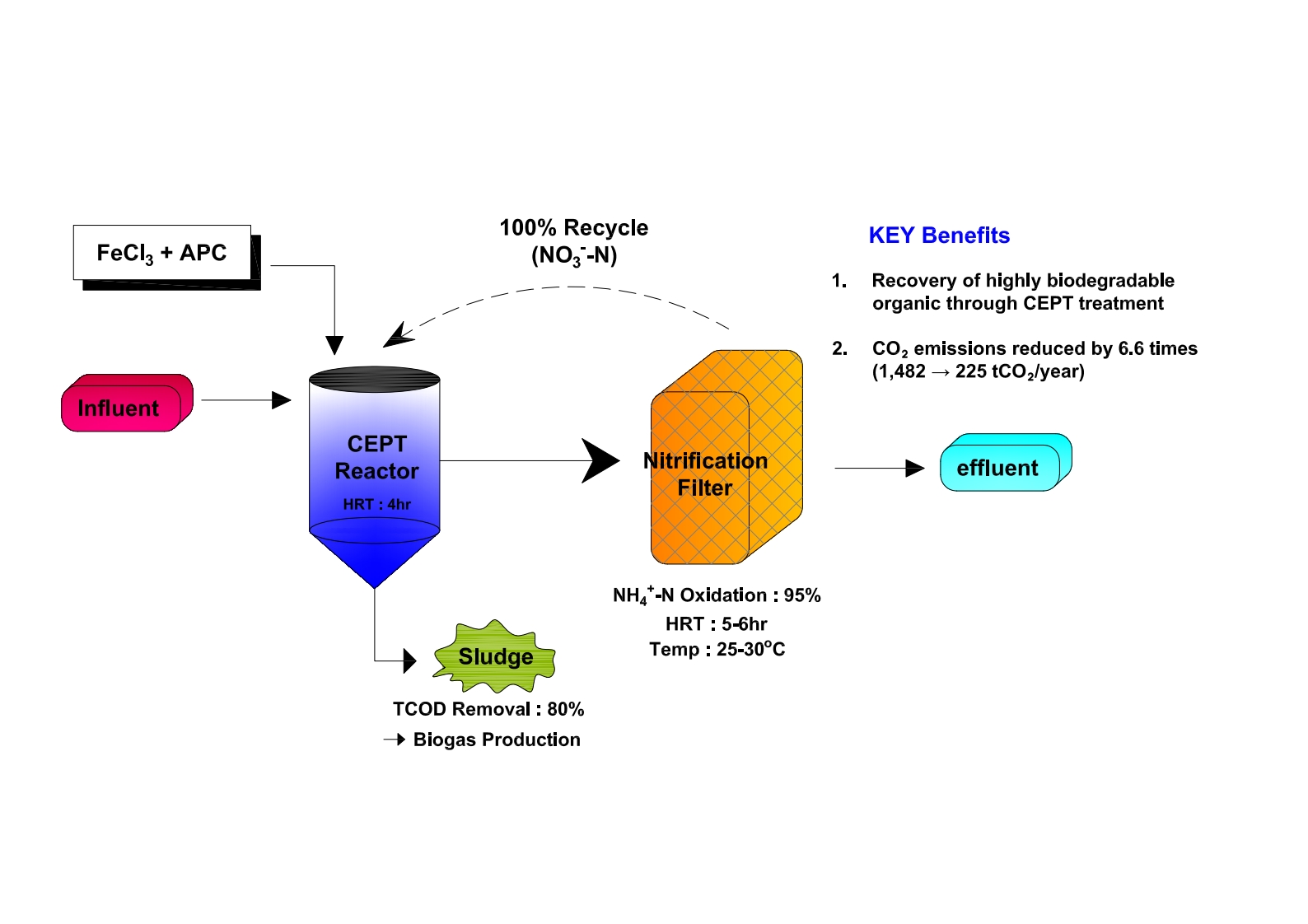

This study aims to derive optimal conditions for recovering organic matter from industrial wastewater using CEPT while simultaneously removing nitrogen and phosphorus. First, a CEPT process will be introduced to increase organic matter recovery in the primary clarifier, and the organic matter removal efficiency according to coagulant dosage and the energy potential of recovered sludge will be evaluated. Subsequently, nitrified effluent in the following nitrification filter will be returned to the CEPT reactor for denitrification using biodegradable SCOD, and the generated biomass will be recovered together.

2. Materials and Methods

The industrial wastewater used in this study had TCOD of 230 mg/L, NH₄

+-N of 18.6 mg/L, NO₃

--N of 4.7 mg/L, and T-P of 1.6 mg/L as shown in

Table 1, with a TCOD/TN ratio of approximately 9.83, indicating a relatively high organic matter content [

30]. Among the influent components, NO₃

--N comprised approximately 20% of the total nitrogen. The pH was 7.2±0.08, which is neutral, and the alkalinity was 300 mg-CaCO₃/L. The wastewater samples used for coagulation experiments were collected from the inlet of the primary clarifier after the grit chamber, and experiments were conducted within 12 hours while storing the samples at 4°C after collection.

For TCOD separation, ferric chloride (FeCl₃·6H₂O) 1% reagent and anionic polymer 0.1% reagent were prepared and used as coagulants. For coagulation pH adjustment, HCl 0.01 M (0.01 N) and NaOH 0.01 M (0.01 N) reagents were prepared and used. A 2 L capacity jar test apparatus from Phipps & Bird was used to determine optimal coagulation conditions. The jar specifications (W×L×H) were 11.5×11.5×21 cm, and the impeller specifications (W×L) were 7.62×2.54 cm.

In the coagulation experiments, the primary coagulant ferric chloride (FeCl₃·6H₂O) was first injected in the range of 0.25-3.0 mM to evaluate COD removal efficiency and derive the appropriate coagulant dosage. Subsequently, along with the appropriate ferric chloride dosage, the coagulation aid anionic polymer was injected at 0.5-1.0 mM, and COD removal efficiency was evaluated to determine optimal coagulation conditions based on the results.

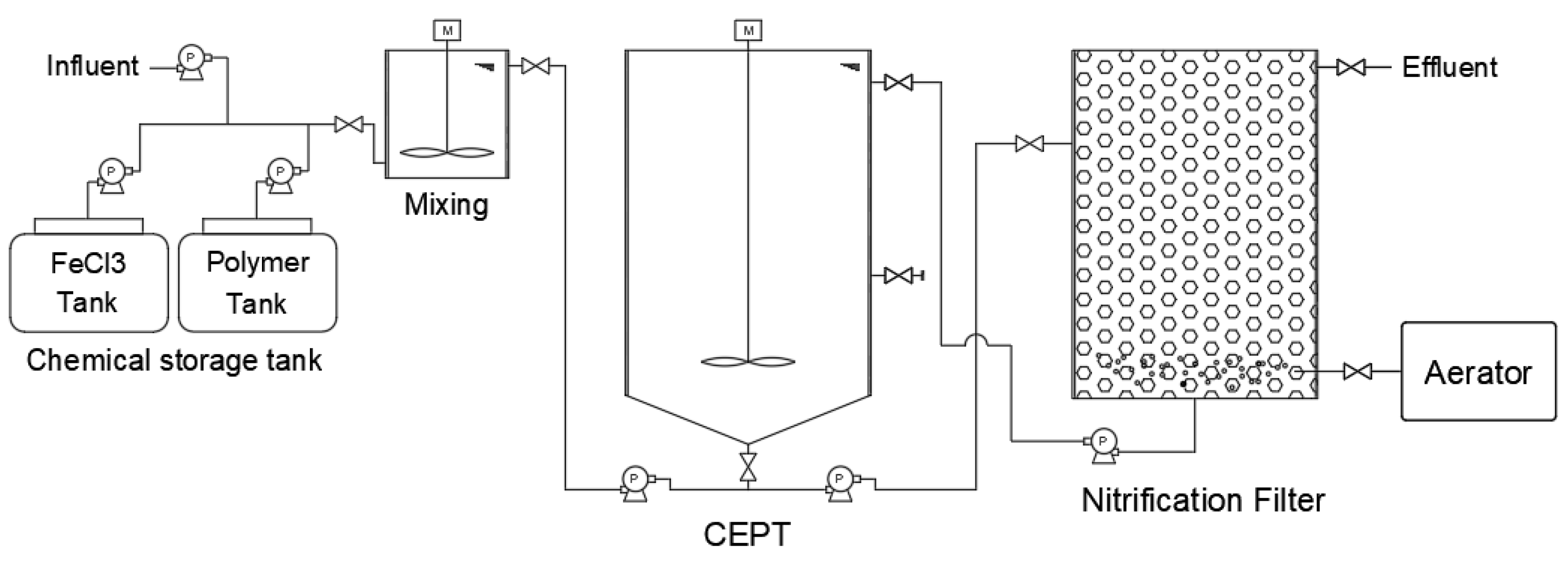

A continuous bench-scale experimental apparatus (CEPT-NF,

Figure 1) including a coagulation reactor was installed and operated at the wastewater treatment site. CEPT settled sludge generated during this process was collected to analyze volatile solids (VS) content, and COD. A 2 L rectangular acrylic reactor (W×H×L: 11.5×11.5×21 cm) was used as the coagulation reactor in the CEPT-NF process. For mixing, a paddle (W×L: 7.62×2.54 cm²) was installed 10 cm below the water surface, and the mixing intensity (velocity gradient, G value) and mixing time and were set to 200 sec⁻¹. Coagulants were injected at the predetermined optimal amounts using two metering pumps, and the temperature was adjusted to the range of 25-30°C considering the nitrification reaction. The CEPT reactor was cylindrical with a volume of 15 L and a depth of 45 cm. A paddle was installed at the bottom of the CEPT to enable effective mixing of the influent wastewater with added coagulants and settled sludge, operating at 10 rpm. The influent wastewater and nitrified return water were injected at the bottom of the CEPT to allow mixing by the paddle, and the primary sludge was discharged once daily through a valve installed in the middle of the CEPT. The CEPT retention time was varied from 2 hours (same as field conditions) to 6 hours, and TCOD removal efficiency was analyzed according to the presence or absence of coagulant dosage.

The nitrification reactor was constructed from a 25 L cylindrical acrylic pipe, filled with approximately 30% clay ball (5 mm) media, and activated sludge was circulated to allow attachment of nitrifying microorganisms. The nitrification reactor was operated in upflow mode with diffusion stones installed at the bottom and aeration rate. To maintain the activity of the nitrification reactor, a heating device was installed to control water temperature (20-30°C), and activated sludge was periodically injected in fixed amounts until the nitrification reaction reached steady state.

The continuous CEPT-NF process analyzed TCOD recovery efficiency according to surface loading rates of CEPT under the optimal coagulation conditions determined from jar tests. The DO concentration in the nitrification reactor was maintained in the range of 3-5 mg/L, and the recycle ratio of nitrified effluent was operated at 50-100%.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the local industrial wastewater.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the local industrial wastewater.

| Parameters |

CEPT |

NF |

Overflow rate

(m3/m2 ·day)

|

3.4 - 10.2 |

- |

| HRT (hr) |

2 – 6 |

3.3 – 10.0 |

| Flow rate (mL/min) |

42 – 125 |

| Volume (L) |

15 |

25 |

| Recycle ratio (%) |

- |

50 – 100 |

| DO (mg/L) |

- |

3 – 5 |

| Temperature (°C) |

- |

20 – 30 |

| Waste sludge rate(mL/day) |

3 |

- |

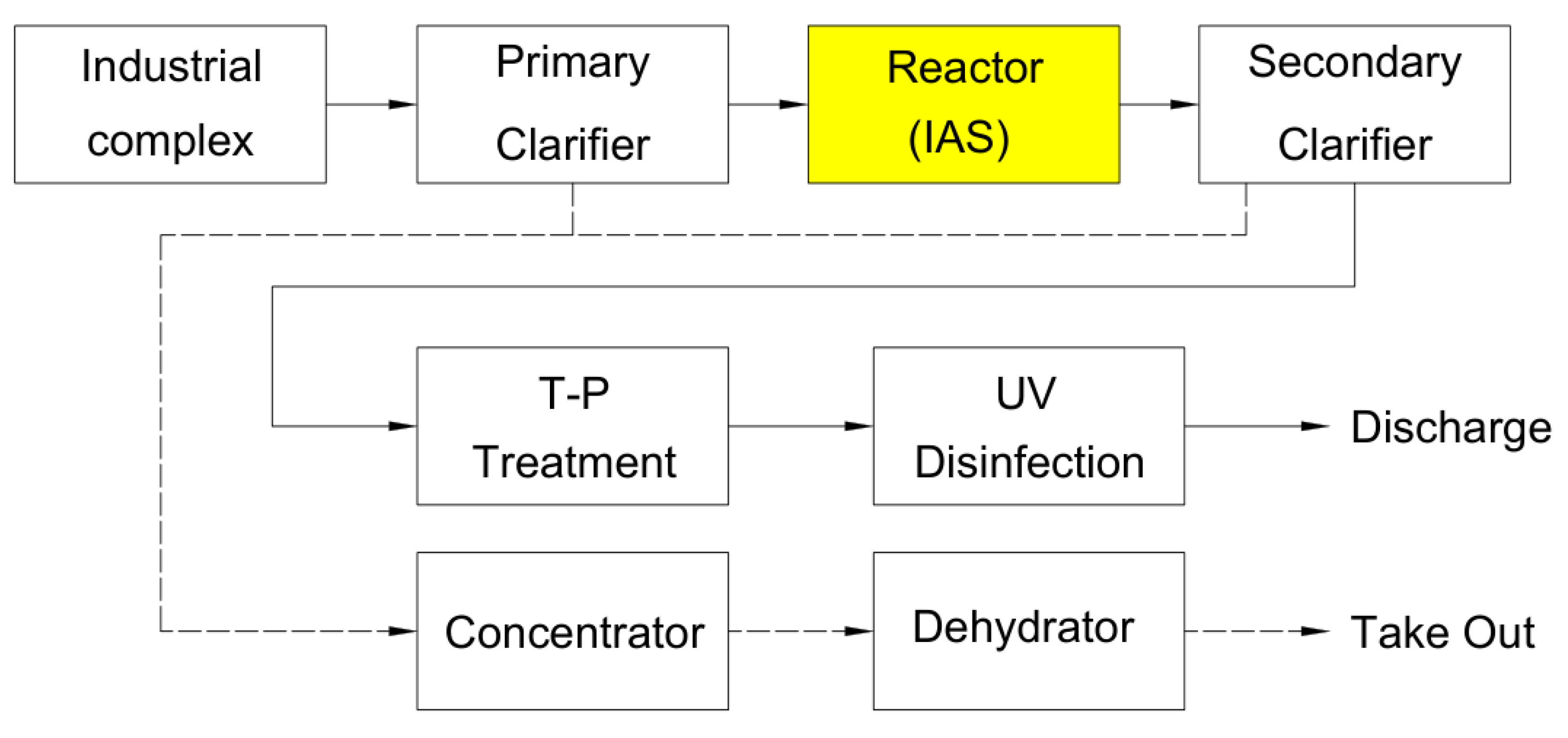

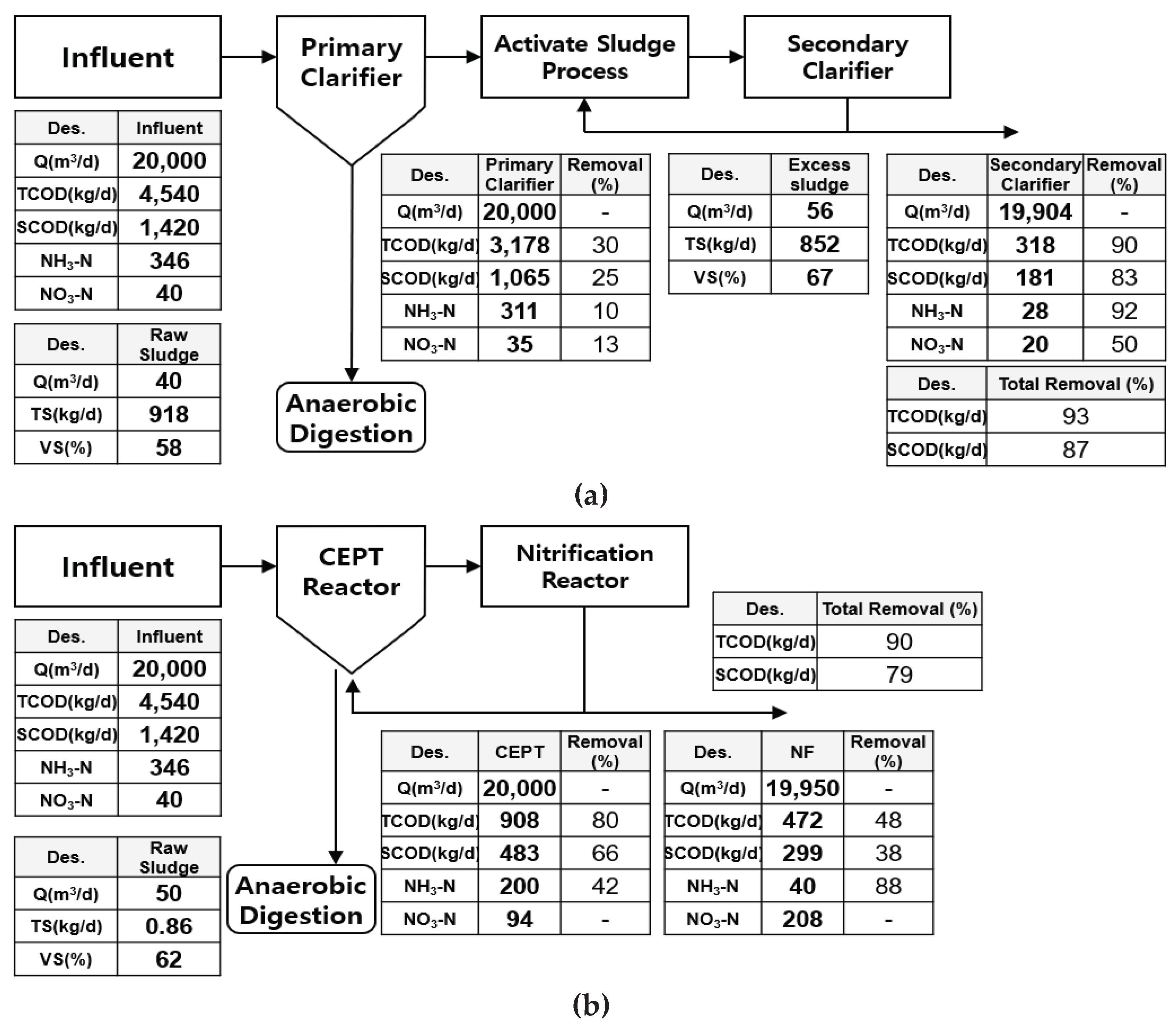

To comparatively evaluate the environmental performance of the actual wastewater treatment facility and the CEPT process, material balance analysis was conducted targeting the industrial complex wastewater treatment facility in local city. The study aimed to analyze CO₂ generation from biological organic matter removal in existing facilities and compare CO₂ generation by calculating the CO₂ equivalent value for organic matter recovered through coagulation precipitation in primary clarifiers when the CEPT is applied.

The local industrial wastewater treatment facility receives and treats 20,000 m³/day of wastewater and operates using the Intermittent Aeration System(IAS) which is an intermittent aeration method.

Figure 2 shows the process diagram of the full scale industrial wastewater treatment facility.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Operating Conditions for CEPT

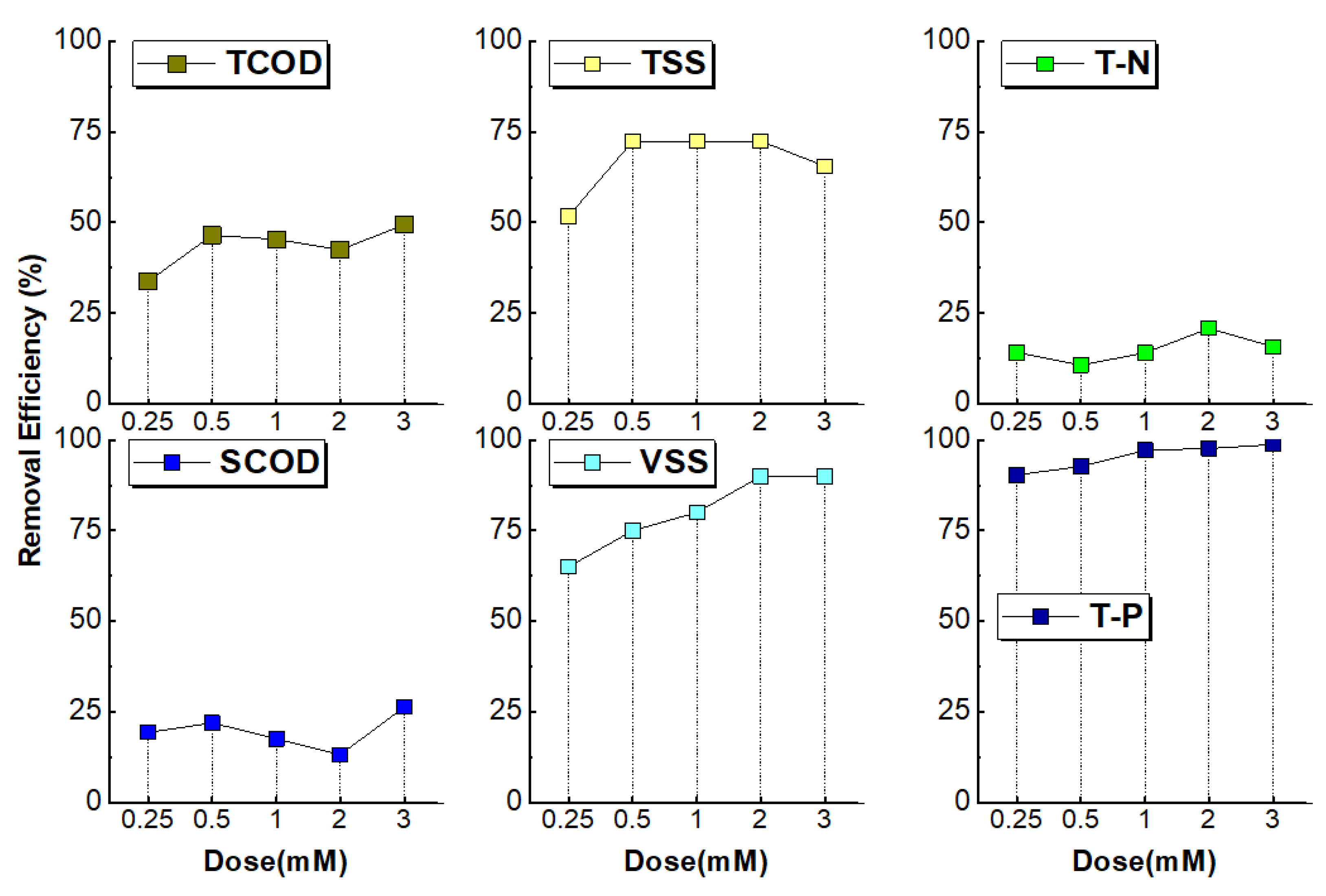

The results of jar tests conducted to determine optimal coagulation conditions for CEPT to physically and chemically separate organic matter in industrial wastewater are shown in

Figure 3. Although polyaluminum chloride (PACl), a polyaluminum coagulant, is more effective than FeCl₃ in removing total suspended solids (TSS), it has been reported to have inhibitory effects on hydrolysis and acid production reactions of precipitated Alum sludge [

3]. Fe sludge shows higher VFA yields during anaerobic digestion processes, and since Fe(III) is reduced to Fe(II) causing decomposition of Fe coagulated sludge, it also exhibits high TP removal efficiency and easy release as PO₄

3--P.

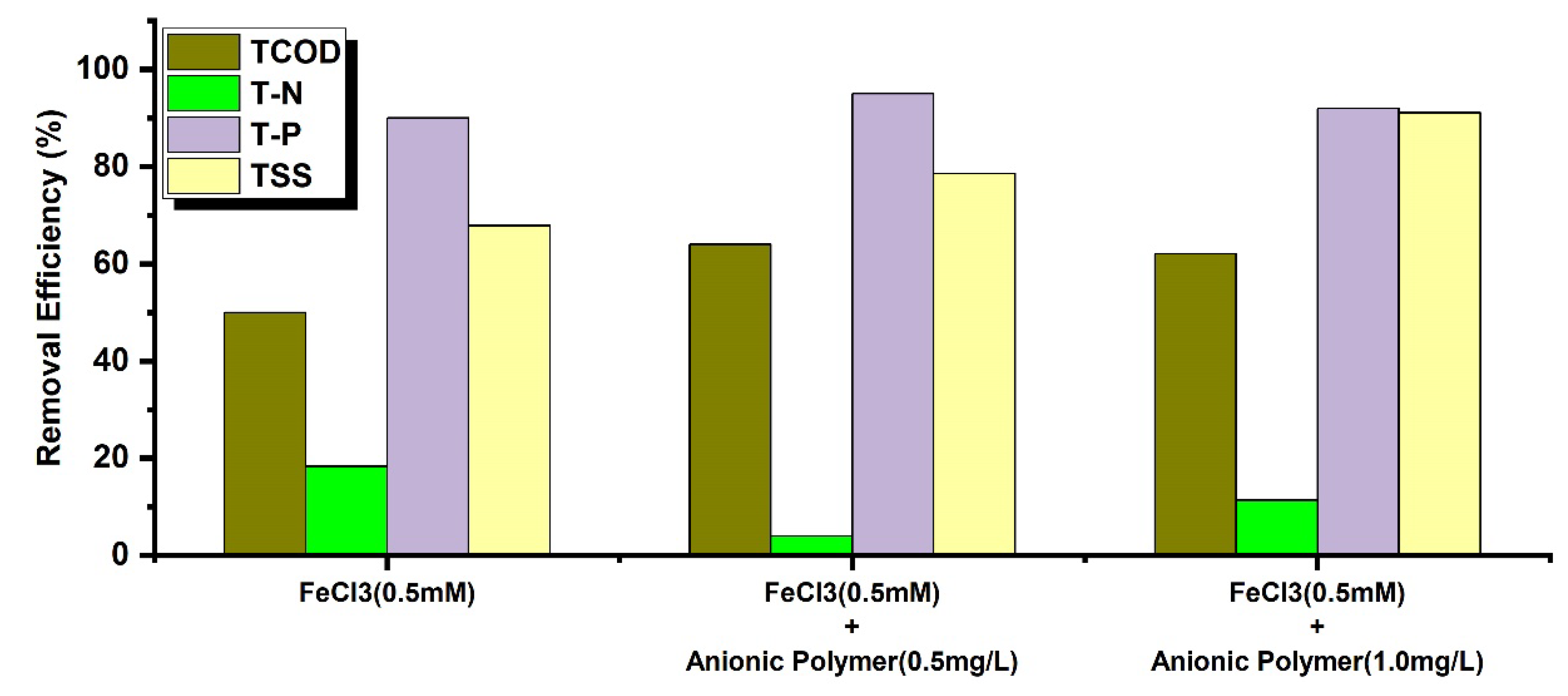

In this study, jar tests were conducted with FeCl₃ in dosing range of 0.25 to 3 mM. As shown in

Figure 3, TCOD removal efficiency was 34% at 0.25 mM and 47% at 0.5 mM, with no significant increase observed at higher dosage (45%, 42%, and 49% at 1 mM, 2 mM, and 3 mM, respectively). Lin et al. (2017) reported that when the FeCl₃ dosage was 0.22 mM in sewage coagulation, PO₄

3--P removal efficiency was 87.5% and TCOD removal efficiency was 68.3% [

3]. This difference is attributed to variations in coagulation efficiency for organic matter (COD) removal across different wastewater types. The SCOD removal efficiency of the industrial wastewater used in this study was low at 19% with a 0.25 mM dosage and 26% at 2 mM, with approximately 80% of SCOD remaining unremoved by coagulation.

Haydar and Aziz reported that CEPT can remove more than 98% of suspended solids (TSS) but only 7-28% of SCOD [

31]. The SCOD/TCOD ratio of domestic sewage in Korea ranges from 28% to 42% [

32], while the industrial wastewater used in this study had a ratio of 60.9%, which is considered to contribute to the relatively low TCOD removal efficiency. VSS removal efficiency was 64% when 0.25 mM FeCl₃ was injected and 74% when 0.5 mM was injected. TP removal efficiency was 90% at 0.25 mM dosage and 93% at 0.5 mM dosage, with no significant efficiency increase observed at higher dosages. Therefore, the optimal FeCl₃ dosage amount for efficient T-P removal is considered to be 0.5 mM.

To evaluate the effect of anionic polyelectrolytes(AP), the FeCl₃ dosage was fixed at 0.5 mM, and removal efficiency was assessed according to APC dosages (

Figure 4). When FeCl₃ 0.5 mM and APC 0.5 mg/L were injected, TCOD removal efficiency increased to 64%, TP to 95% and TSS to 79%. When the APC dosage amount was increased to 1.0 mg/L under the same conditions, TSS removal efficiency increased to 91%, while TCOD removal efficiency decreased to 62% and TP removal efficiency decreased to 92%. This is attributed to the offset of coagulation effects between APC molecules due to excessive coagulant dosage. Based on these results, the operating conditions for coagulation continuous CEPT-NF were set at FeCl₃ 0.5 mM and APC 0.5 mg/L for effective removal of TCOD and TP.

3.2. Organic Matter Removal in CEPT Reactor

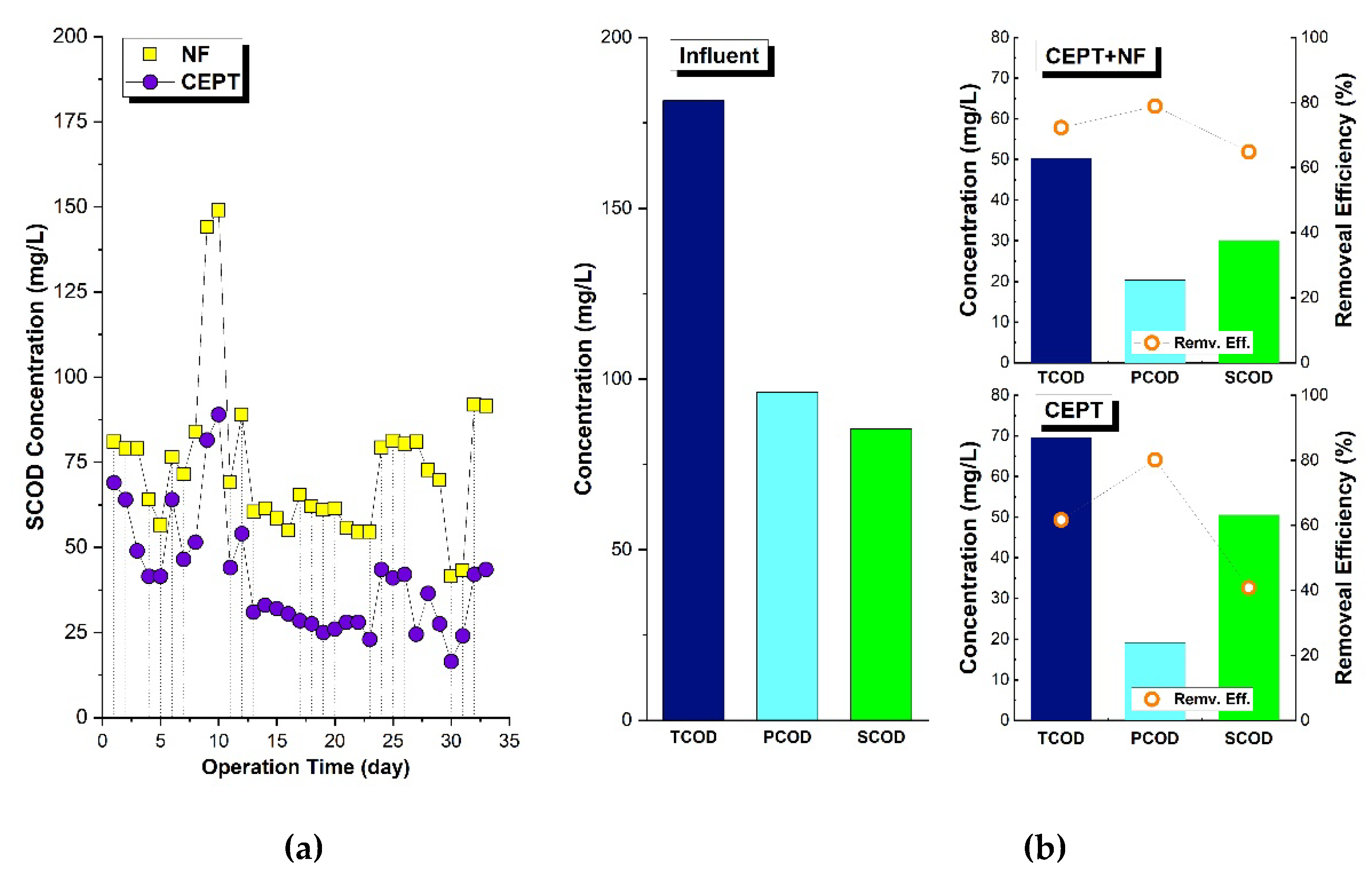

SCOD that is difficult to coagulate in CEPT can be classified as biodegradable COD because it consists of dissolved COD with small particle (2 μm or less). The SCOD can be eliminated through biological methods using microorganisms. Since the TN removal efficiency in CEPT is low at around 10% (

Figure 5a), nitrification-denitrification processes or recent CANON processes need to be introduced. CEPT effluent can be nitrified in a nitrification filter (NF) and then returned to CEPT for denitrification using SCOD as a carbon source. As a result, SCOD utilized by denitrifiers with nitrate to form microbial sludge and removed in CEPT, acting as auxiliary coagulants aid to improve TCOD removal in CEPT.

Figure 5b shows the COD removal efficiency when nitrified effluent was returned to CEPT. When 100% of the nitrified effluent was returned, the particulate COD (PCOD) removal efficiency showed little difference at 65%, but SCOD removal efficiency increased from 41% to 66%. This was because SCOD was effectively removed by denitrifying microorganisms in CEPT through the return of nitrified effluent.

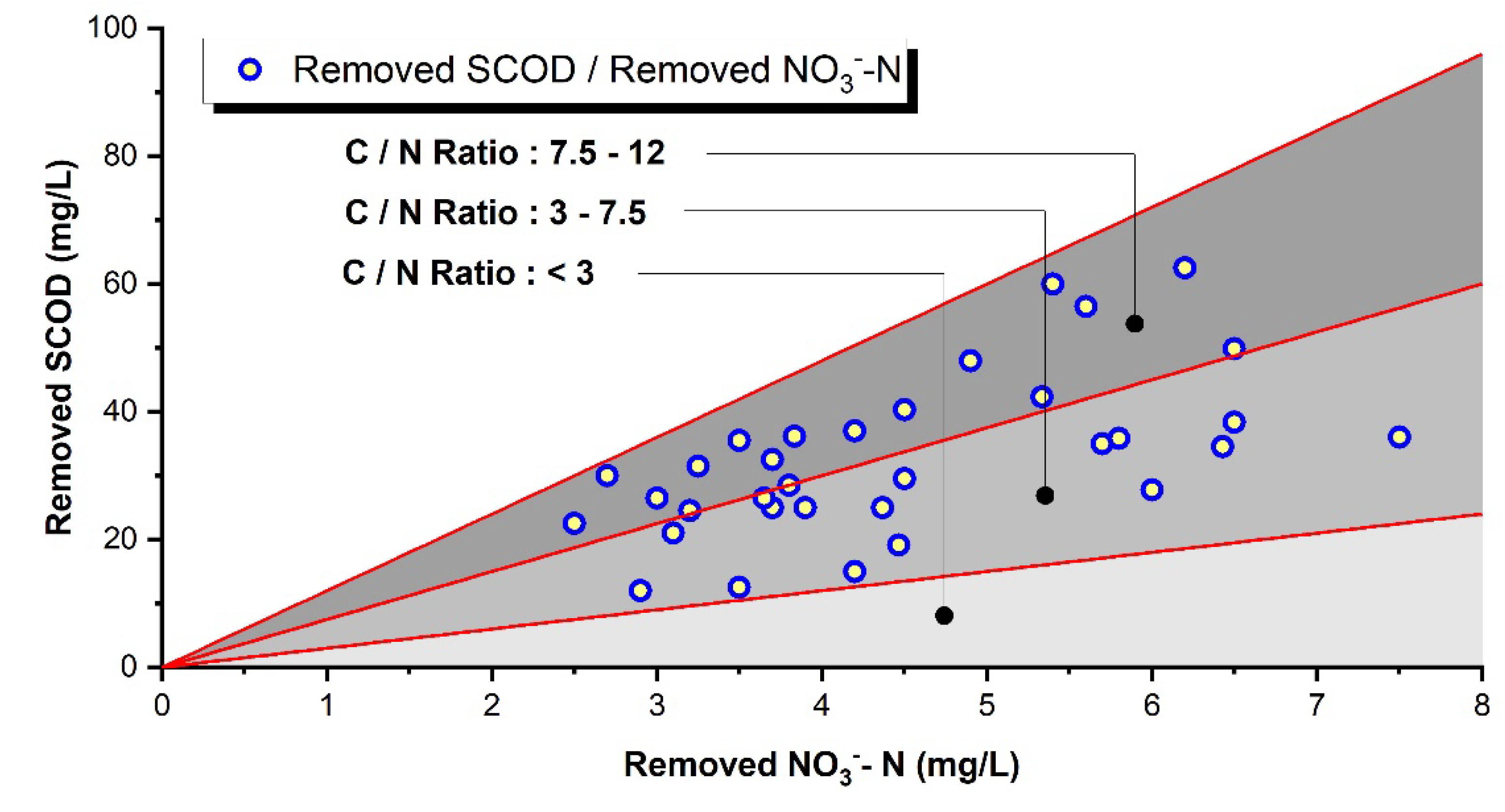

Figure 6 and

Table 3 show the relationship between organic matter removal and denitrification reactions in CEPT according to effluent recycle ratios. A high correlation was observed between NH₄⁺-N denitrification and SCOD removal. When effluent was not returned, NO₃⁻-N removal efficiency was 19%, which increased to 32% with 50% return and 56% with 100% return, showing improved denitrification efficiency. Although the theoretical organic carbon to nitrate ratio required for denitrification (COD/NO₃⁻-N) is 2-3, the actual removed COD/NO₃⁻-N ratio was as high as 7.5 in CEPT. SCOD can be utilized by denitrifying microbial growth and removed by co-precipitation with the microbial flocs and coagulant precipitates.

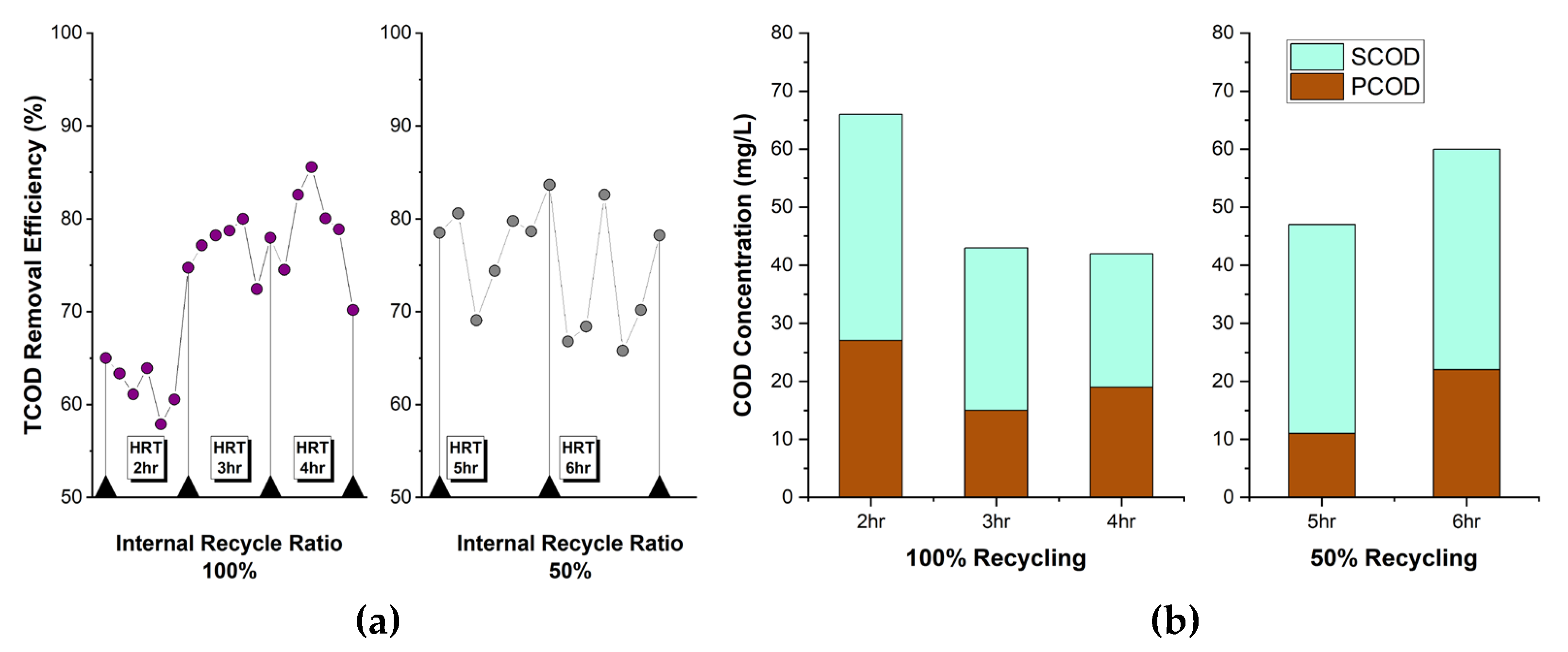

TCOD removal efficiency was analyzed according to CEPT retention time along with effluent recycle ratios. When retention time is increased by changing the flow rate in a CEPT reactor of the same size, the surface loading rate of CEPT, which not only increases TSS removal efficiency but also provides sufficient reaction time for microbial denitrification reactions, thereby enhancing denitrification efficiency.

Figure 7a shows the TCOD removal efficiency while adjusting recycle ratios to 100% and 50% and simultaneously increasing CEPT HRT from 2 hr to 3 hr and 4 hr. At a 100% recycle ratio, TCOD removal efficiency increased to 80% at HRT over 3 hr and it reached to maximum of 85% at 4 hr. When the recycle ratio was reduced to 50% and operated with longer retention times of 5 hr and 6 hr, TCOD removal efficiency no longer increased and was maintained in the 70-80% range. However, despite the increased reaction time, TCOD removal efficiency remained lower than that achieved with a 100% recycle ratio. This can be interpreted as indicating that the reaction time required for denitrification needs to be 3 hours or more, and that a 100% recycle ratio supplies sufficient NO₃⁻-N loading to CEPT for removing SCOD in the influent wastewater.

Figure 7b shows the concentration of PCOD and SCOD at different HRTs and recycle ratio in CEPT. When the recycle ratio was 100%, more SCOD was removed at HRT of 3 hr and 4 hr compared to other conditions, confirming a lower SCOD/TCOD ratio. The SCOD/TCOD ratio decreased to 65% at 3 hr HRT and 55% at 4 hr HRT. However, when the recycle ratio was 50%, SCOD was not removed even when HRT increased to 5-6 hr, and the SCOD/TCOD ratio remained high around 76-77%. Consequently, it is determined that to effectively remove SCOD in CEPT, the internal recycle ratio of nitrified effluent should be maintained at 100%, and HRT should be secured at least 3 hr. Maintaining a high recycle ratio may increase SCOD and NO₃⁻-N removal efficiency. However, concerns arise regarding decreased TCOD removal efficiency practical surface loading rate increases and associated energy consumption due to high recycle ratio indicating that additional optimization is required.

According to Shewa et al. (2020), TCOD removal efficiency in CEPT for sewage treatment was reported to reach a maximum of 95.6%[

19]. However, the results of this study targeting industrial wastewater showed that 80% of TCOD could be removed in CEPT through physicochemical coagulation combined with biological denitrification.

3.3. Nitrification Characteristics

Since autotrophic nitrifying bacteria have slow growth rates and compete with heterotrophic COD-removing microorganisms for dissolved oxygen, the COD/N ratio must be maintained low for efficient cultivation of nitrifying bacteria. It is known that when the COD/N ratio exceeds 3.0, the proportion of nitrifying bacteria decreases, leading to reduced nitrification rates [

33]. When TCOD is effectively removed (80%) in CEPT, the COD/N ratio entering the subsequent nitrification filter (NF) becomes 2.0 or lower, allowing dominant cultivation of nitrifying bacteria in NF.

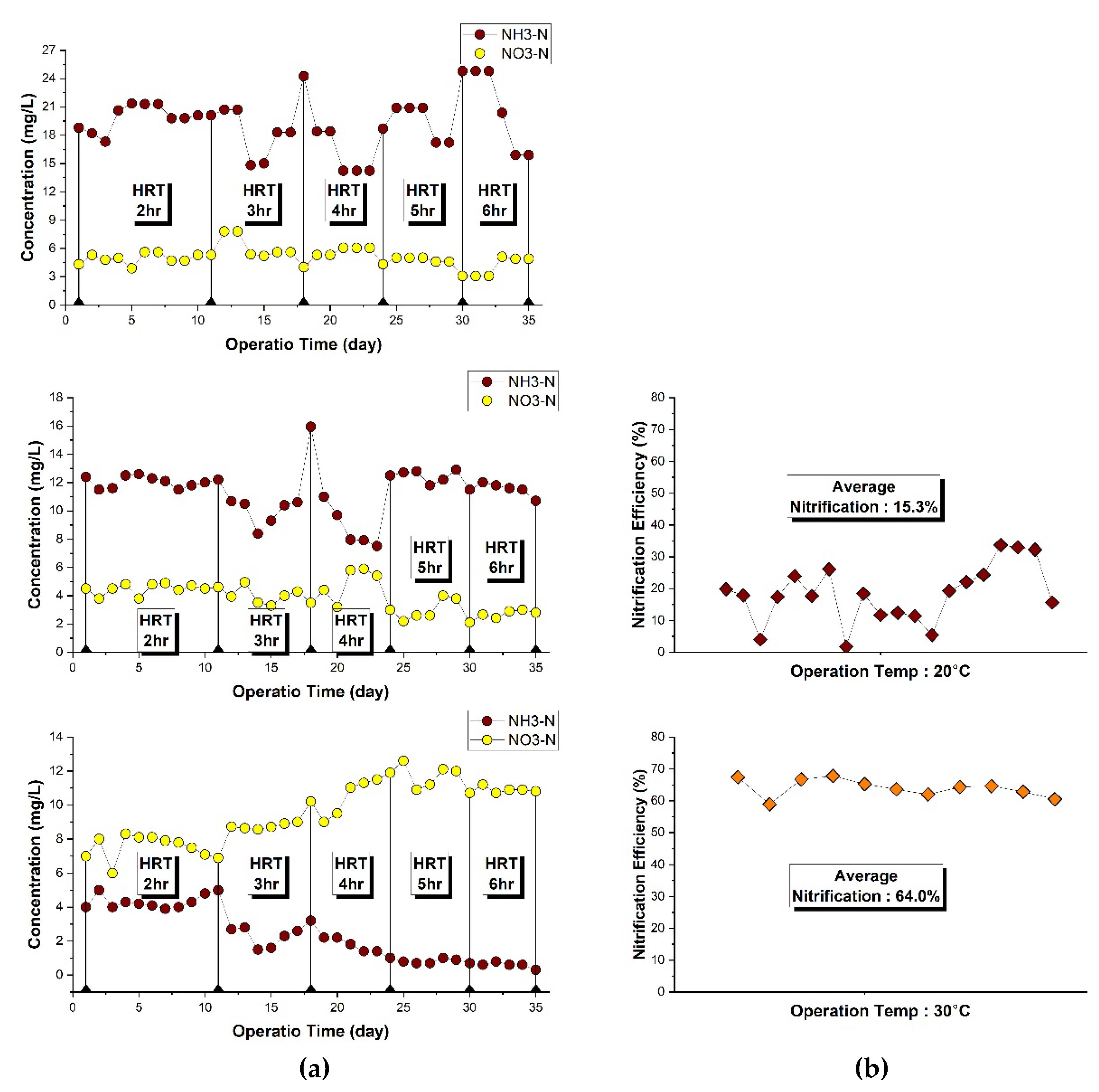

Since nitrification is significantly affected by pH and temperature, pH was adjusted to 7.2, and temperature was maintained in the range of 20-30°C. As shown in

Figure 8(b), when NF HRT was fixed at 2 hr and operated at 20°C, the nitrification efficiency showed low efficiency 15%. To achieve higher nitrification efficiency, experiments were conducted at an elevated temperature of 30°C, resulting in nitrification efficiency to 64%. All subsequent experiments were conducted at 30°C by using temperature control devices (DH-1000 AC-2R and DH-UT180).

The nitrification efficiency at HRT of NF 2-6 hr are shown in

Figure 8a. Nitrification efficiency was 64% at 2 hr HRT, and it increased to 3, 4, 5, and 6 hr, it was 88% at 3 hr and reached over 95% at 5-6 hr. The NF reactor combined with CEPT achieved effective nitrification efficiency using attached-growth biological filters with media under low COD/N ratios. The results showed that TN and SCOD could be removed together by denitrification with recycle of the nitrified effluent to CEPT, and biomass could be also removed in CEPT (

Figure 7b).

3.4. Mass Balance Analysis on TCOD and TN

To evaluate the greenhouse gas emission from the on-site ICWTP(Industrial Complex Wastewater Treatment Plant) and the CEPT-NF process, material balance for TCOD was analyzed and presented in

Figure 9. The influent concentration was set identically based on the actual wastewater, and loading rates and concentration were calculated reflecting flow rates.

The retention times for each process in the ICWTP are: primary clarifier 4 hr, intermittent aeration biological reactor 14 hr, and secondary clarifier 4 hr. The CEPT-NF process was set to the optimal conditions derived above: FeCl₃ dosage of 0.5 mM and polymer coagulant aid of 0.5 mg/L, operated at HRT of 4 hr. The nitrification filter retention time was set and operated at 4 hr. The sludge recycle ratio of the ICWTP is 35%, while the internal recycle ratio of the CEPT-NF process was set at 100%.

Greenhouse gas emissions were calculated by combining CO₂ generation from microbial organic matter decomposition in bioreactors and CO₂ generation from aeration in the industrial complex wastewater treatment facility and the CEPT-NF process.

First, CO₂ generation from microbial organic matter decomposition in bioreactors was calculated by multiplying the COD removed in the bioreactor by the CO₂ conversion factor (CO₂ value generated when 1g of COD is removed). Rahul Kadam reported in a carbon-neutral wastewater treatment system study that 1.42g of CO₂ is generated when 1g of COD is removed in wastewater treatment plant bioreactors[

34].

COD removed by coagulation precipitation in the CEPT process is discharged in solid form, significantly reducing the greenhouse gas emission potential of wastewater treatment processes.

Table 4 shows the greenhouse gas reduction amounts for ICWTP and when the CEPT process is applied. The CO₂ generation calculation based on COD removed in the bioreactor of the ICWTP resulted in 4,061 kg/d, and the annual total greenhouse gas emissions were calculated to be 1,482 tCO₂. For the CEPT-NF process, excluding COD that undergoes coagulation precipitation in the CEPT reactor, the CO₂ generation calculation based on 436 kg/d of COD removed during denitrification in CEPT showed that 619 kg/d of CO₂ would be generated, corresponding to 225 tCO₂ of annual total greenhouse gas emissions. This suggests that applying the CEPT process, which serves the role of a primary clarifier, could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by approximately 6.6 times compared to conventional wastewater treatment facilities.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the CEPT technique was introduced to efficiently separate and remove organic matter in the primary clarifier of industrial wastewater treatment processes. Research was conducted to recover organic matter contained in raw wastewater by applying coagulant dose and returning nitrified effluent, and the conclusions are as follows:

CEPT jar-test results showed that when 0.5 mM FeCl₃ and 0.5 ppm anionic polymer were added, removal efficiencies of 64% for TCOD, 88% for TP, and 79% for TSS were achieved. TN removal efficiency was low at 4%, indicating that a nitrogen removal process is required as a subsequent process to CEPT.

Bench-scale experiments conducted at different HRTs showed that TCOD removal rates were 78% and 80% at 3 hr and 4 hr with 100% RAS, the higher TCOD removal was possible through chemical coagulation of PCOD as well as biological assimilation of SCOD by denitrifications.

The SCOD/TCOD ratio showed a tendency to decrease as RAS increased. At 100% RAS, SCOD/TCOD was 55%, while at 50% RAS it was 70%. Simultaneously, denitrification efficiency was 32% at 50% RAS and 56% at 100% RAS. This indicates that SCOD, which has low coagulation efficiency, was effectively removed by biological denitrification, and the ΔSCOD/ΔNO₃⁻-N ratio was 7.5

Nitrification efficiency showed low (15) at 20°C, it increased to 64% at an elevated temperature 30°C.

HRT for nitrification 88% at HRT 3 hr and over 95% at HRT 5-6 hr.

The greenhouse gas emission for COD removal in the ICWTP as 1,482 tCO₂, while it was 225 tCO₂ the CEPT-NF. This represents a 6.6-fold reduction in applying the CEPT process by conventional in the ICWTP

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B.J.; methodology, J.H.K., B.C.P.; software, J.H.K. and S.H.L.; validation, J.H.K., S.Y.L. and Y.H.C.; formal analysis, H.B.J. and J.H.K.; investigation, S.Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.K. and S.H.L.; writing—review and editing, H.B.J. and J.H.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Legg, S. IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021 - the Physical Science basis. Interaction 2021, 49, 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiken, C.; Breuer, G.; Klaversma, E.; Santiago, T.; Van Loosdrecht, M. Sieving wastewater–Cellulose recovery, economic and energy evaluation. Water research 2013, 47, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Li, R.-h.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, X.-y. Recovery of organic carbon and phosphorus from wastewater by Fe-enhanced primary sedimentation and sludge fermentation. Process Biochemistry 2017, 54, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Tan, G.-Y. A.; Jing, H.; Lee, P.-H.; Lee, D.-J.; Leu, S.-Y. Enhanced primary treatment for net energy production from sewage–The genetic clarification of substrate-acetate-methane pathway in anaerobic digestion. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 431, 133416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H. Recovering the energy potential of sewage as approach to energy self-sufficient sewage treatment. Journal of Korean Society on Water Environment 2018, 34, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, O.; Enderle, P.; Varbanov, P. Ways to optimize the energy balance of municipal wastewater systems: lessons learned from Austrian applications. Journal of Cleaner Production 2015, 88, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Gu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y. COD capture: a feasible option towards energy self-sufficient domestic wastewater treatment. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 25054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malovanyy, A.; Trela, J.; Plaza, E. Mainstream wastewater treatment in integrated fixed film activated sludge (IFAS) reactor by partial nitritation/anammox process. Bioresource technology 2015, 198, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooijman, G.; De Kreuk, M.; Van Lier, J. Influence of chemically enhanced primary treatment on anaerobic digestion and dewaterability of waste sludge. Water Science and Technology 2017, 76, 1629–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, H.; Batstone, D. J.; Mouiche, M.; Hu, S.; Keller, J. Nutrient removal and energy recovery from high-rate activated sludge processes–Impact of sludge age. Bioresource Technology 2017, 245, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canals, J.; Cabrera-Codony, A.; Carbó, O.; Baldi, M.; Gutiérrez, B.; Ordoñez, A.; Martín, M. J.; Poch, M.; Monclús, H. Nutrients removal by high-rate activated sludge and its effects on the mainstream wastewater treatment. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 479, 147871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada-Santos, A.; Rivadulla, E.; Paredes, L.; Carballa, M.; Romalde, J.; Lema, J. M. Comprehensive comparison of chemically enhanced primary treatment and high-rate activated sludge in novel wastewater treatment plant configurations. Water research 2020, 169, 115258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; De Clippeleir, H.; Thomas, W.; Jimenez, J. A.; Wett, B.; Al-Omari, A.; Murthy, S.; Riffat, R.; Bott, C. A-stage and high-rate contact-stabilization performance comparison for carbon and nutrient redirection from high-strength municipal wastewater. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 357, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnetta, C.; Saerens, B.; Meerburg, F. A.; Decru, S. O.; Broeders, E.; Menkveld, W.; Vandekerckhove, T. G.; De Vrieze, J.; Vlaeminck, S. E.; Verliefde, A. R. High-rate activated sludge systems combined with dissolved air flotation enable effective organics removal and recovery. Bioresource technology 2019, 291, 121833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P. H. The significance of microbial Fe (III) reduction in the activated sludge process. Water Science and Technology.

- Farajnezhad, H.; Gharbani, P. Coagulation treatment of wastewater in petroleum industry using poly aluminum chloride and ferric chloride. International Journal of Research and Reviews in Applied Sciences 2012, 13, 306–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, F.; Wang, Y.; Lau, F. T.; Fung, W.; Huang, D.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, T. Anaerobic digestion of chemically enhanced primary treatment (CEPT) sludge and the microbial community structure. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2016, 100, 8975–8982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, M.; Afify, H.; Abdelfattah, A. Chemically enhanced primary treatment of sewage using the recovered alum from water treatment sludge in a model of hydraulic clari-flocculator. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2017, 19, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewa, W. A.; Dagnew, M. Revisiting chemically enhanced primary treatment of wastewater: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Wu, J.; Kang, J.; Gao, J.; Liu, R.; Gao, Y.; Wang, R.; Fan, R.; Khoso, S. A.; Sun, W. Comparison of the reduction of chemical oxygen demand in wastewater from mineral processing using the coagulation–flocculation, adsorption and Fenton processes. Minerals Engineering 2018, 128, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Third, K.; Sliekers, A. O.; Kuenen, J.; Jetten, M. The CANON system (completely autotrophic nitrogen-removal over nitrite) under ammonium limitation: interaction and competition between three groups of bacteria. Systematic and applied microbiology 2001, 24, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T. V.; Nguyen, P. D.; Phan, T. N.; Luong, D. H.; Van Truong, T. T.; Huynh, K. A.; Furukawa, K. Application of CANON process for nitrogen removal from anaerobically pretreated husbandry wastewater. International biodeterioration & biodegradation, 2019; 136, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jetten, M. S.; Horn, S. J.; van Loosdrecht, M. C. Towards a more sustainable municipal wastewater treatment system. Water science and technology 1997, 35, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Q.; Laloo, A.; Xu, Y.; Bond, P. L.; Yuan, Z. Achieving stable nitritation for mainstream deammonification by combining free nitrous acid-based sludge treatment and oxygen limitation. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 25547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Ormeci, B.; Mishra, S.; Hussain, A. Simultaneous partial Nitrification, ANAMMOX and denitrification (SNAD)–A review of critical operating parameters and reactor configurations. Chemical engineering journal 2022, 433, 133677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desloover, J.; De Clippeleir, H.; Boeckx, P.; Du Laing, G.; Colsen, J.; Verstraete, W.; Vlaeminck, S. E. Floc-based sequential partial nitritation and anammox at full scale with contrasting N2O emissions. Water Research 2011, 45, 2811–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeminck, S. E.; Hay, A. G.; Maignien, L.; Verstraete, W. In quest of the nitrogen oxidizing prokaryotes of the early Earth. Environmental microbiology 2011, 13, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Farzadkia, M. Chemically enhanced primary treatment of municipal wastewater; Comparative evaluation, optimization, modelling, and energy analysis. Bioresource Technology Reports 2022, 18, 101042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-M.; Jun, H.-B.; Hong, S.-P.; Kwon, J.-C. Small sewage treatment system with an anaerobic-anoxic-aerobic combined biofilter. Water science and technology, 2004; 48, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Puyuelo, B.; Ponsá, S.; Gea, T.; Sánchez, A. Determining C/N ratios for typical organic wastes using biodegradable fractions. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydar, S.; Aziz, J. A. Characterization and treatability studies of tannery wastewater using chemically enhanced primary treatment (CEPT)—a case study of Saddiq Leather Works. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 1076. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.-B.; Hur, H.-W.; Kang, H.; Chang, S.-O. Assessment of the Organic and Nitrogen Fractions in the Sewage of the Different Sewer Network Types by Respirometric Method. Journal of Korean Society of Environmental Engineers 2009, 31, 649–654. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, J.; Vicent, T.; Lafuente, F. Influence of temperature on denitrification of an industrial high-strength nitrogen wastewater in a two-sludge system. Water Sa 2003, 29, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.; Khanthong, K.; Park, B.; Jun, H.; Park, J. Realizable wastewater treatment process for carbon neutrality and energy sustainability: A review. Journal of environmental management 2023, 328, 116927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).