1. Introduction

As existing literature on optimization — for example, Nocedal and Wright [

1], pp. 1–9 and Boyd and Vandenberghe [

2], pp. 1–2 — points out, constrained optimization plays an important role not only in natural sciences, where it was first developed by Euler, Fermat, Lagrange, Laplace, Gauss, Cauchy, Weierstrass, and others, but also in economics and its numerous applications, such as econometrics and operations research, including managerial planning at different levels, logistics optimization, and resource allocation. The history of modern constrained optimization began in the late 1940s to 1950s, when economics, already heavily reliant on calculus since the marginalist revolution of 1871–1874 [

3], pp. 43–168, and the emerging discipline of econometrics, standing on the shoulders of model fitting [

4] (pp. 438–457), internalized a new array of quantitative methods referred to as programming after the U.S. Army’s logistic jargon. Programming — including classical, linear, quadratic, and dynamic variants — originated with Kantorovich in economic planning in the USSR and was independently discovered and developed into a mathematical discipline by Dantzig in the United States (who introduced the bulk of terminology and the simplex algorithm) [

5] [

6], pp. 1–51. Since the pivotal proceedings published by Koopmans [

7], programming became an integral part of mathematical economics [

8,

9,

10], in both microeconomic analysis (an overview is provided in Intriligator and Arrow [

11], pp. 76–91) and macroeconomic modeling, such as Leontief’s input-output framework outlined in Koopmans [

7], pp. 132–173 and, in an extended form, in Dorfman et al. [

12], pp. 204–264.

Calculus, model fitting, and programming are, however, subject to strong assumptions, including function smoothness, full matrix ranks, well-posedness, well-conditionedness, feasibility, non-degeneracy, and non-cycling (in the case of the simplex algorithm), as summarized by Nocedal and Wright [

1], pp. 304–354, 381–382 and Intriligator and Arrow [

11], pp. 15–76. These limitations have been partially circumvented by developing more strategy-based than analysis-based, computationally intensive constraint programming algorithms; consult Frühwirth and Abdennadher [

13] and Rossi et al. [

14] for an overview. Still, specific cases of constrained optimization problems in econometric applications, such as incorporating the textbook two-quarter business-cycle criterion into a general linear model [

15] or solving underdetermined linear programs to estimate an investment matrix [

16], remain unresolved within the existing methodologies and algorithmic frameworks. In response, this text develops a modular two-step convex programming methodology to formalize such problems as a linear system of the form

, including linear(ized) constraints

, with

, where

is a partitioned matrix,

and

are its submatrices,

is a known vector, and

is the vector of unknowns, which includes both the target solution subvector

and an auxiliary slack-surplus subvector

, introduced to accommodate inequalities in constraints. The focus is on its linear algebra foundations with corresponding theorems and lemmas, followed by a discussion of numerical stability, goodness of fit, and potential applications.

The text is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes the historical development and recent advances in convex optimization, motivating the formulation of a new methodology. Section 3 presents the formalization of the estimator, while Section 4 develops a sensitivity analysis for . Section 5 introduces goodness-of-fit statistics, including the normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) and its sample-mean test. Section 6 presents special cases, and Section 7 reports the results of a Monte Carlo experiment and solves simulated problems via CLSP-based Python 3 modules. Section 8 concludes with a general discussion. Throughout, the following notation is used: bold uppercase letters (e.g., ) denote matrices; bold lowercase letters (e.g., ) denote column vectors; italic letters (e.g., ) denote scalars; the transpose of a matrix is denoted by the superscript ⊤ (e.g., ); the inverse by (e.g., ); generalized inverses are indexed using curly braces (e.g., ); the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse is denoted by dagger (e.g., ); norms, where , are denoted by double bars (e.g., ); and condition numbers by . All functions, scalars, vectors, and matrices are defined over the real numbers ().

2. Historical and Conceptual Background of the CLSP Framework

Convex optimization — formally,

, subject to convex inequality constraints

and affine equality constraints

[

2], pp. 7, 127–129, encompassing, among others, least squares, linear programming, and quadratic programming — has its roots in

differential calculus, a concept developed independently by Newton — who was influenced by Wallis and Barrow — in 1665–1666 (published posthumously in 1736), and by Leibniz, who drew among others on Pascal, in 1673–1675 (published in 1684 and 1686) [

17], and, in its constrained form, by Lagrange in the 1760s. Calculus-based optimization dominated analytical methods in mathematics and physics until the 19th century, during which period it was superseded in specific applications by model-fitting techniques, driven by empirical inconsistencies in classical mechanics, particularly in celestial motion [

18], pp. 11–61. Subsequent contributions by Euler, Laplace, Cauchy, and Weierstrass helped shape the modern algorithmic treatment of calculus-based optimization, as presented in, for example, Nocedal and Wright [

1], pp. 10–29 and, for economic applications, in Intriligator and Arrow [

11], pp. 53–72 and Ok [

19], pp. 670–745. In (micro)economic theory, Lagrangian optimization was introduced by Edgeworth, who applied it in 1877 to utility maximization, in 1879 to utilitarian welfare distribution, and in 1881 to general equilibrium via the contract curve [

20]. Since the 19th century, optimizing differentiable scalar-valued functions has become the foundation for the fitting techniques in mathematical statistics [

4], pp. 494–510.

Stigler [

18], pp. 11–61 traced the pre-19th century history leading to the invention of the

least squares method (named after the original French term

la méthode des moindres carrés, henceforth abbreviated as LS) by Legendre in 1805, Adrain in 1808-1809, and independently by Gauss in 1809 (although the latter claimed to have been using the method since 1795; a rigorous discussion of the priority dispute between Gauss and Legendre, a well-known case study in the history of scientific priority, is provided in Plackett [

21] and Stigler [

22] [

23], pp. 320–331). The method’s formalism evolved from Gauss’s, Yule’s, and Laplace’s pre-matrix notations to Pearson’s, Fisher’s, Frisch’s, Aitken’s (who is believed to anticipate the Gauss-Markov theorem [

24]), and Bartlett’s use of Cayley’s 1850s and subsequent methodologies, with the modern

notation, where

is a matrix and

are vectors, introduced around 1950 and already in use by Durbin and Watson, among others [

25]. LS became an essential tool at the dawn of modern econometrics and its application in linear regression (ordinary least squares, OLS) intensified with the creation of the Cowles Commission in the 1930s–1940s U.S. and the works of Fisher, Koopmans, Haavelmo, Stone, Prest, and others [

26], pp. 117–145, [

27], pp. 7–12. Contrary to the stricter assumptions of pure calculus-based optimization, LS (a) enabled modeling over discrete or irregular data, and (b) incorporated residuals, moving beyond exact curve fitting, while still ensuring minimum variance among unbiased linear estimators under the Gauss–Markov theorem.

Early efforts to estimate the normal equations

, where

is the sum-of-squares and cross-products matrix, spurred the development of generalized inverses, numerically stable matrix decompositions, and regularization techniques to tackle

rank-deficient and

ill-posed problems; consult Gentle [

4], pp. 126–154, 217–301 for a comprehensive modern overview. Their interconnection — namely, for the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse

, which has been computed predominantly through singular value decomposition (SVD) since the 1960s, as introduced by Golub and Kahan [

28] (a numerical algorithm for the weighted pseudoinverse was provided in the 1980s by Eldén [

29]) and was demonstrated, among others, in the 1970s by Ward [

30], p. 34 and, more profoundly, in the 2010s by Barata and Hussein [

31], pp. 152–154 to be the limit of a Tikhonov regularization formula

, where

is an identity matrix for

and

is a parameter (for a detailed presentation of the regularization in its original notation, consult Tikhonov et al. [

32], pp. 10–67) — has become a standard perspective in modern numerical analysis and forms the foundation of the CLSP framework, the first step of which is

, where

is either

or a constrained reflexive inverse

.

As documented in the seminal works of Rao and Mitra [

33], pp. vii–viii and Ben-Israel and Greville [

34], pp. 4–5, 370–374, the first pseudoinverses (original term, now typically reserved for

) or generalized inverses (current general term) emerged in the theory of integral operators — introduced by Fredholm in 1903 and further developed by Hurwitz in 1912 — and, implicitly, in the theory of differential operators by Hilbert in 1904, whose work was subsequently extended by Myller in 1906, Westfall in 1909, Bounitzky in 1909, Elliott in 1928, and Reid in 1931. The cited authors attribute their first application to matrices to Moore in 1920 under the term

general reciprocals[

35] (though some sources suggest he may have formulated the idea as early as 1906), with independent formulations by Siegel in 1937 and Rao in 1955, and generalizations to singular operators by Tseng in 1933, 1949, and 1956, Murray and von Neumann in 1936, and Atkinson in 1952–1953. A theoretical consolidation occurred with Bjerhammar’s [

36] rediscovery of Moore’s formulation, followed by Penrose’s [

37,

38] introduction of four conditions defining the unique least-squares minimum-norm generalized inverse

, which, for

, can be expressed in the following way:

In econometrics, it led to conditionally unbiased (minimum bias) estimators [

39] and a redefinition of the Gauss-Markov theorem [

40] in the 1960s, superseding earlier efforts [

41].

Further contributions to the theory, calculation, and diverse applications of

were made in the 1950s–early 1970s by Rao and Mitra [

33], Rao and Mitra [

42] (a synthesis of the authors’ previous works from 1955–1969), Golub and Kahan [

28], Ben-Israel and Greville [

34], Greville [

43], Greville [

44], Greville [

45], Greville [

46], Cline [

47], Cline and Greville [

48], Ben-Israel and Cohen [

49], and Lewis and Newman [

50] (the most cited sources on the topic in the Web of Science database, although the list is not exhaustive; consult Rao and Mitra [

33], pp. vii–viii for an extended one), which, among others, introduced the concept of a

-generalized inverse

, where

is the space of the

-generalized inverses of

, — hereafter,

-inverses for

,

-inverses, Drazin inverses, and higher-order

are disregarded because of their inapplicability to the CLSP framework — by satisfying a subset or all of the (i)–(iv) conditions in Equation (

1), as described in

Table 1. Formally, for

,

,

, and arbitrary matrices

, any

-inverse, including all

-inverses and

, can be expressed as

, out of which only

and a constrained

— here, the Bott-Duffin inverse [

51], expressed in modern notation as

, where

and

are orthogonal (perpendicular) projectors onto the rows and columns defined by an orthonormal matrix

— can be uniquely defined (

under certain conditions) and qualify as minimum-norm unbiased estimators in the sense of Chipman [

39] and Price [

40].

Starting from the early 1960s, Cline [

47], Rao and Mitra [

33], pp. 64–71, Meyer [

54], Ben-Israel and Greville [

34], pp. 175–200, Hartwig [

55], Campbell and Meyer [

52], pp. 53–61, Rao and Yanai [

56], Tian [

57], Rakha [

58], Wang et al. [

53], pp. 193–210, and Baksalary and Trenkler [

59], among others, extended the formulas for

to partitioned (block) matrices, including the general column-wise,

,

, and

— and, equivalently, row-wise,

,

,

, — cases (employed in the numerical stability analysis of the CLSP estimator for

in the decomposition

given

,

, and

):

where

, with equality iff

, and strict inequality iff

. For the original definitions and formulations, consult Rao and Mitra [

33], pp. 64–66 and Ben-Israel and Greville [

34], pp. 175–200.

To sum up,

(especially

), SVD, and regularization techniques — namely, Lasso (based on the

-norm), Tikhonov regularization (hereafter, referred to as Ridge regression, based on the

-norm), and Elastic Net (a convex combination of

and

norms) [

4], pp. 477–479 — have become an integral part of estimation (model-fitting), where

can be defined as a

minimum-norm best linear unbiased estimator (MNBLUE), reducing to the classical

BLUE in (over)determined cases. These methods have been applied in (a) natural sciences since the 1940s [

32] (pp. 68–156) [

36,

51] [

60], pp. 85–172 [

61,

62,

63], and (b) econometrics since the 1960s [

39,

40] [

64], pp. 36–157, 174–232 [

65], pp. 61–106 [

66], pp. 37–338 in both unconstrained and equality-constrained forms, thereby relaxing previous rank restrictions.

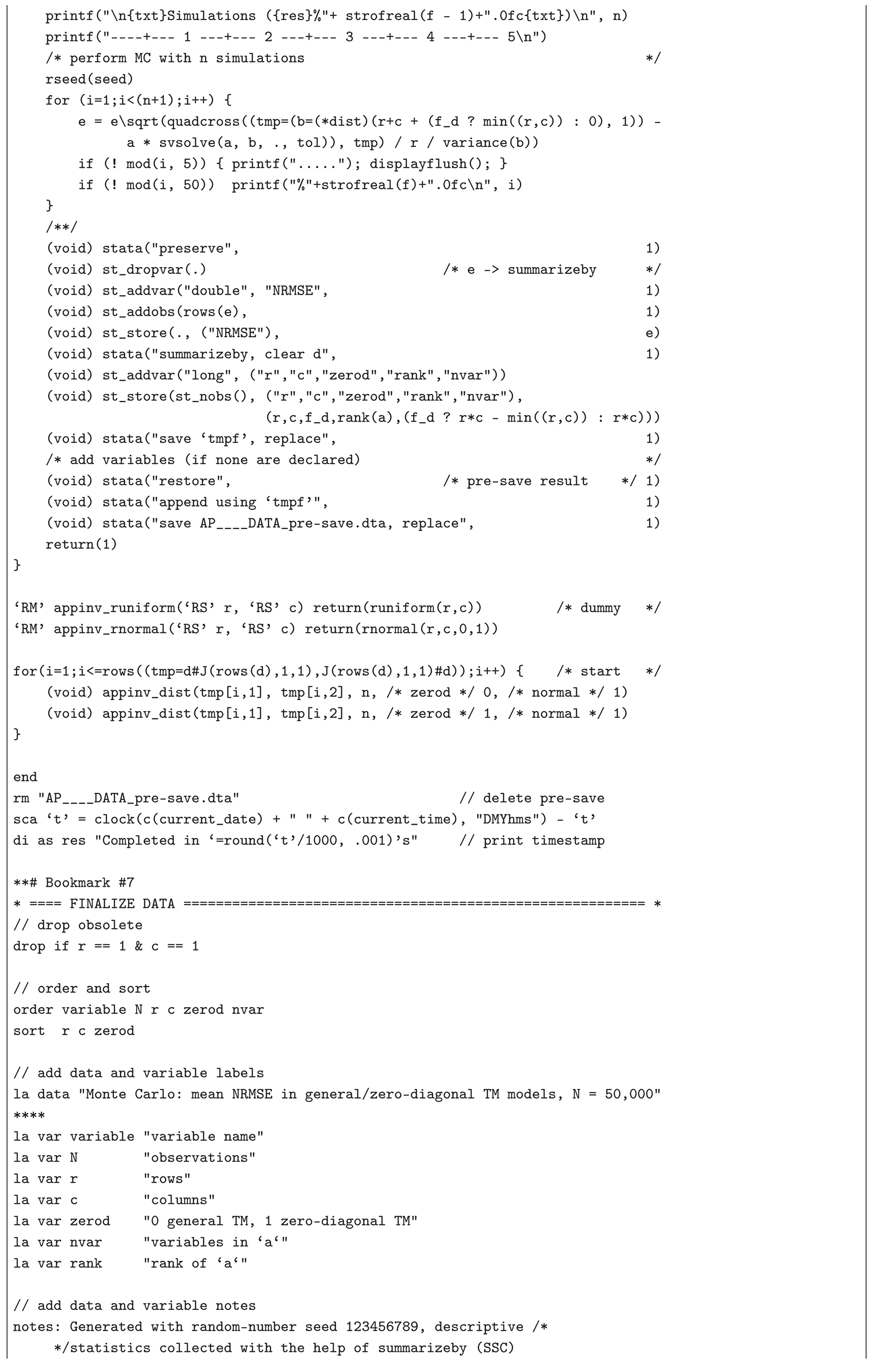

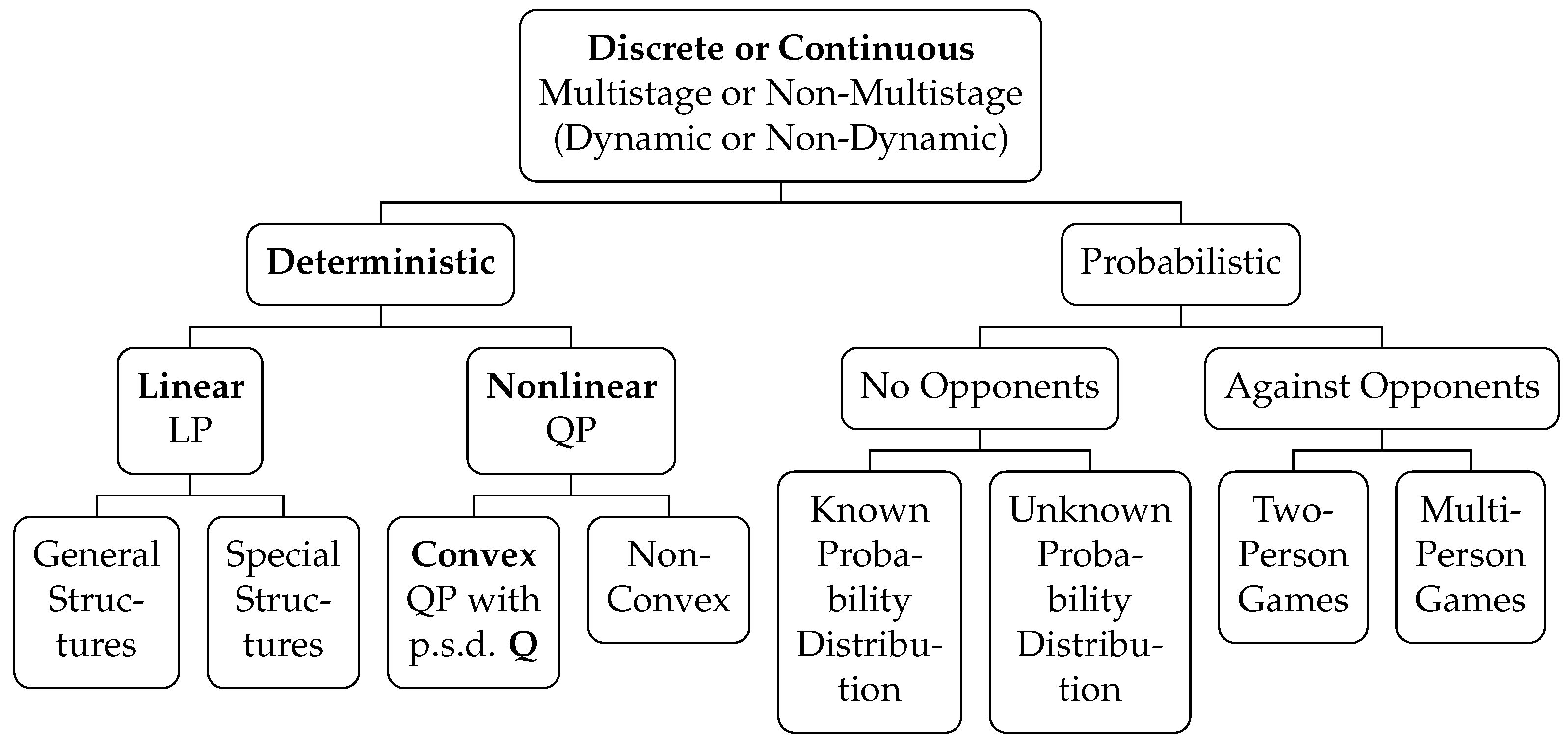

The incorporation of

inequality constraints into optimization problems during the 1930s–1950s (driven by the foundational contributions of Kantorovich [

67], Koopmans [

7], and Dantzig [

6], along with the later authors [

5]) marked the next milestone in the development of convex optimization under the emerging framework of programming, namely for linear cases (LP) — formally,

subject to

,

(with the dual

subject to

, where

,

, and

— and convex quadratic ones (QP) — formally,

subject to

(with the dual

), where

is symmetric positive definite,

,

, and

— [

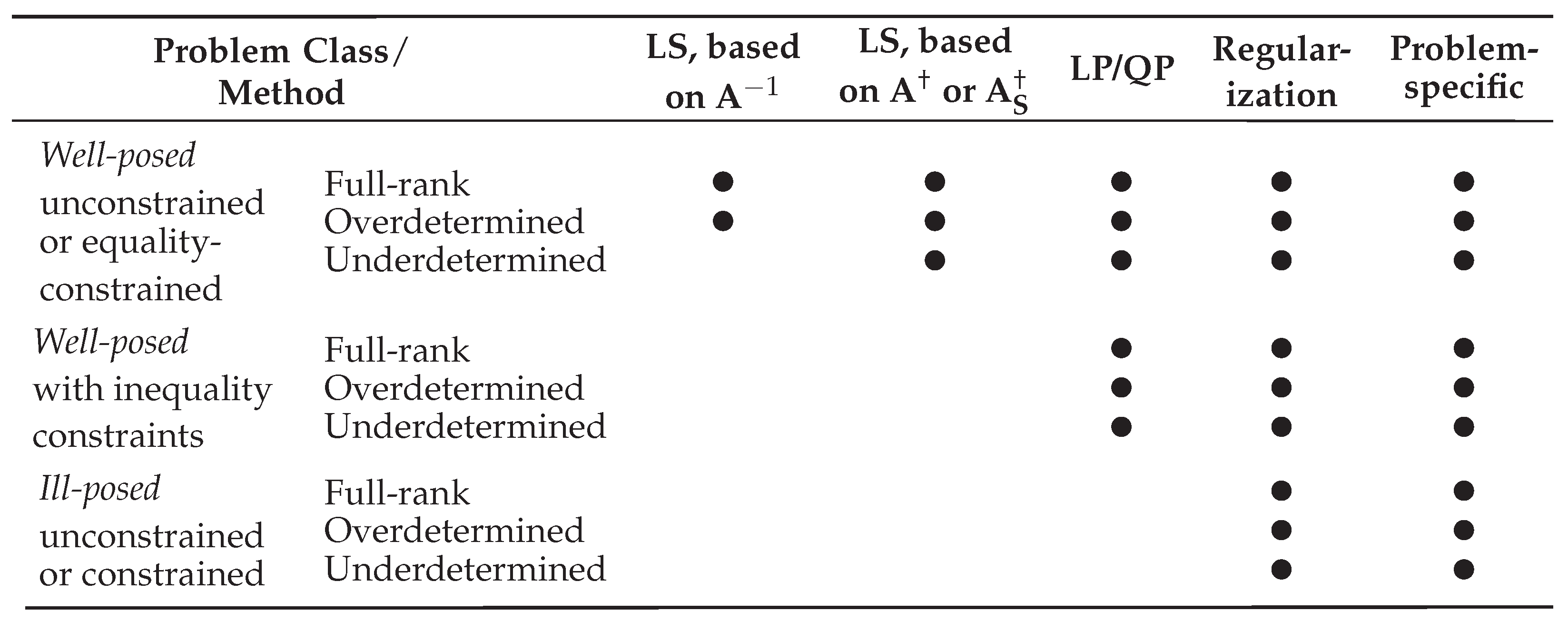

2] (pp. 146–213) (for a classification of programming, consult

Figure 1) [

6] (pp. 1–31) [

1], pp. 355–597, with Dantzig’s simplex and Karmarkar’s interior-point algorithms being efficient solvers [

68,

69].

In the late 1950s–1970s, the application of LP and QP extended to LS problems (which can be referred to as a

major generalization of mainstream convex optimization methods; consult Boyd and Vandenberghe [

2], pp. 291–349 for a comprehensive modern overview) with the pioneering works of Wagner [

70] and Sielken and Hartley [

71], expanded by Kiountouzis [

72] and Sposito [

73], who first substituted LS with LP-based (

-norm) least absolute (LAD) and (

-norm) least maximum (LDP) deviations and derived unbiased (

-norm,

) estimators with non-unique solutions; whilst, in the early 1990s, Stone and Tovey [

69] demonstrated algorithmic equivalence between LP algorithms and iteratively reweighted LS. Judge and Takayama [

74] and Mantel [

75] reformulated (multiple) LS with inequality constraints as QP, and Lawson and Hanson [

64], pp. 144–147 introduced, among others, the non-negative least squares (NNLS) method. These and further developments are reflected in the second step of the CLSP framework, where

is corrected under a regularization scheme inspired by Lasso (

), Ridge (

), and Elastic Net (

) regularization, where

, subject to

.

The final frontier that motivates the formulation of a new framework is the class of

ill-posed problems in Hadamard’s sense [

4] (pp. 143, 241), i.e., systems with no (i) feasibility,

, (ii) uniqueness,

, (iii) stability,

, or formulation — as a well-posed LS, LP, or QP problem — of solution under mainstream assumptions, where

,

, and

, such as the ones described in Bolotov [

15], Bolotov [

16]: namely, (a) underdetermined,

, and/or ill-conditioned linear systems,

,

, in cases of LS and LP, where solutions are either non-unique or highly sensitive to perturbations [

76,

77]; and (b) degenerate,

, with cycling behavior,

, and

,

, in all LP and QP problems, where efficient methods, such as the simplex algorithm, may fail to converge [

78,

79]. Such problems have been addressed since the 1940s–1970s by (a) regularization (i.e., a method of perturbations) and (b) problem-specific algorithms [

2] (pp. 455–630). For LS cases, the list includes, among others, Lasso, Ridge regularization, and Elastic Net [

4] (pp. 477–479), constrained LS methods [

80], restricted LS [

81], LP-based sparse recovery approaches [

77], Gröbner bases [

82], as well as derivatives of eigenvectors and Nelson-type, BD, QR- and SVD-based algorithms [

83]. For LS and QP — among others, Wolfe’s regularization-based technique for simplex [

84] and its modifications [

78,

79], Dax’s LS-based steepest-descent algorithm [

85], a primal-dual NNLS-based algorithm (LSPD) [

86], as well as modifications of the ellipsoid algorithm [

87]. A major early attempt to unify (NN)LS, LP, and QP within a single framework to solve both well- and ill-posed convex optimization problems was undertaken by Übi [

88], Übi [

89], Übi [

90], Übi [

91], Übi [

92], who proposed a series of problem-specific algorithms (VD, INE, QPLS, and LS1).

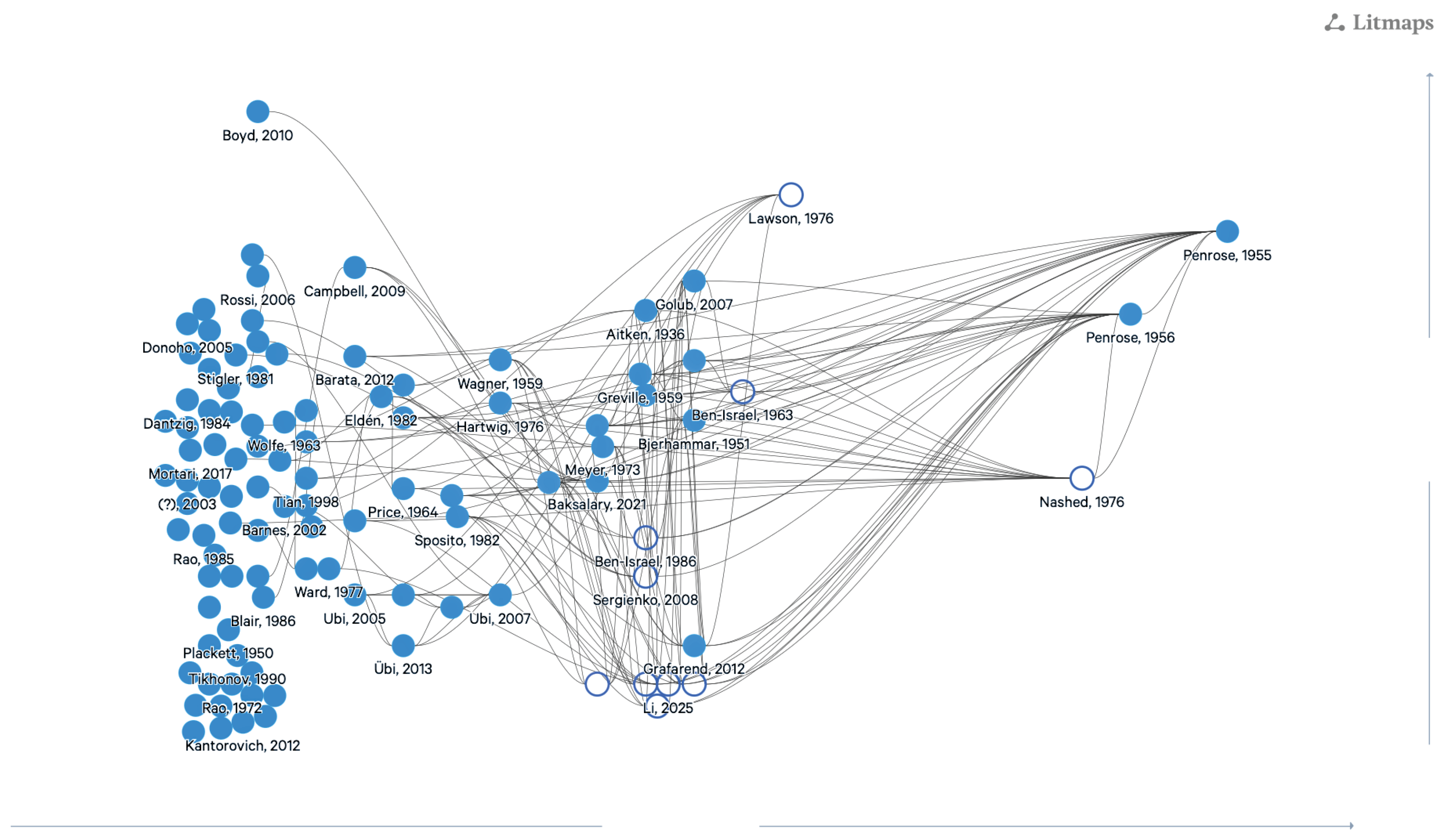

Figure 2 compares all the mentioned methods by functionality.

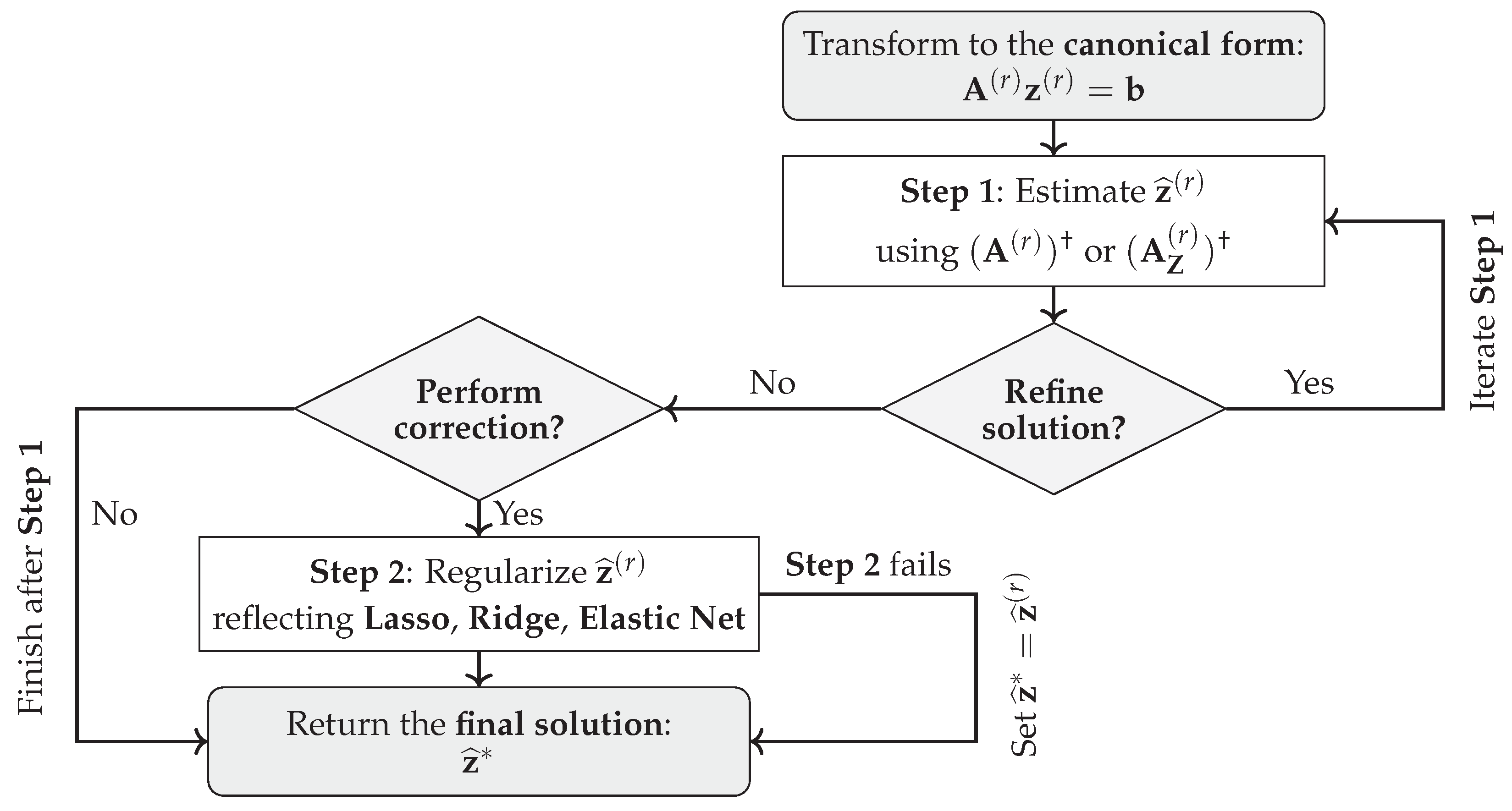

Therefore, to accommodate all considered problem classes, a modular two-step CLSP consists of (first, compulsory, step) minimum-norm LS estimation, based on or , followed by a (second, optional, step) regularization-based correction, contributing to the generalization of convex optimization methods by eliminating the need for problem-specific algorithms.

3. Construction and Formalization of the CLSP Estimator

Based on the citation and reference counts, as well as in-group relevance (i.e., the number of citations within the examined collection) of the selected sources (consult

Figure 3), this text incorporates the seminal studies on the topic, with the exception of historical seminar proceedings (e.g., Nashed) and a few secondary contributions by Ben-Israel, Sergienko, and Grafarend (Lawson and Hanson, erroneously indicated as missing due to incomplete monograph indexing, are already included in the bibliography as a 1995 reprint of the 1976 edition [

64]). Hence, it can be claimed that the CLSP framework is grounded in the general algorithmic logic of Wolfe [

84] and Dax [

85], as further formalized by Osborne [

78], who were among the first to introduce an additional estimation step into simplex-based solvers.

The proposed CLSP estimator is

modular — i.e., it comprises selectively omittable and repeatable actions for enhanced flexibility — and consists of

two steps: (a) the first, grounded in the theory of (constrained) pseudoinverses as summarized in Rao and Mitra [

33], Ben-Israel and Greville [

34], Lawson and Hanson [

64], and Wang et al. [

53], is iterable to refine the solution and serves as a mandatory baseline in cases where the second step becomes infeasible (due to mutually inconsistent constraints) — as exemplified by Whiteside et al. [

93] for regression-derived constraints and by Blair [

76], Blair [

94] in systems with either too few or too many effective constraints; — and (b) the second, grounded in the theory of regularization and convex programming as summarized in Tikhonov et al. [

32], Gentle [

4], Nocedal and Wright [

1], and Boyd and Vandenberghe [

2], provides an optional correction of the first step, drawing on the logic of Lasso, Ridge, and Elastic Net to address ill-posedness and compensate for constraint violations or residual approximation errors resulting from the first-step minimum-norm LS estimate. This structure ensures that CLSP

is able to yield a unique solution under a strictly convex second-step correction and

extends the classical LS framework in both scope and precision. The modular algorithmic flow is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The first process block in the CLSP algorithmic flow denotes the transformation of the initial problem —

, where

is the projection onto the

coordinates,

is the vector of model (target) variables to be estimated (

),

,

, is a vector of latent variables that appear only in the constraint functions

and

, such that

,

is the permutation matrix, and

and

are the linear(ized) inequality and equality constraints,

— to the

canonical form (a term first introduced in LP [

6] (pp. 75–81)), where (a)

is the block

design matrix consisting of a

-and-

constraints matrix , a

model matrix, a sign

slack matrix , and either a

zero matrix (if

) or a reverse-sign — i.e., based on

—

slack matrix (provided

):

and (b)

is

the full vector of unknowns, comprising (model)

and (slack)

,

and

— an equivalent problem [

2] (pp. 130–132), where

and

. The constraint functions

and

must be linear(ized), so that

,

.

In practical implementations, for problems with

, where

E is an estimability limit, the partitioning

,

,

,

, and

, can be used, leading to a total of

, composed of

and

,

,

, with a total of

:

are then treated as slack rows/columns, i.e., incorporated into , to act as balancing adjustments since the reduced model, by construction, tends to inflate the estimates .

The second process block, i.e., the

first step of the CLSP estimator, denotes obtaining an (iterated if

) estimate

(alternatively,

-times

with

) through the (constrained) Bott-Duffin inverse

[

51][

53](pp. 49–64), defined on a subspace specified by a symmetric idempotent matrix

(regulating solution-space exclusion through binary entries 0/1, such that

restricts the domain of estimated variables to the selected subspace, while

leaves the data vector, i.e., the input

, unprojected).

reduces to the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse

when

, and equals the standard inverse

iff

:

The number of iterations (r) increases until a termination condition is met, such as error or , whichever occurs first. In practical implementations, is efficiently computed using the SVD (see Appendix A.1).

The third process block, i.e., the

second step of the CLSP estimator, denotes obtaining a regularized solution

(alternatively,

-times

with

) — unless the algorithmic flow terminates after Step 1, in which case

— by penalizing deviations from the (iterated if

) estimate

reflecting Lasso (

, where

), Ridge (

, where

, a projector equal to

iff

is of full column rank, and

), and Elastic Net (

, where

) [

4] (pp. 477–479), [

2] (pp. 306–310):

where the parameter

may be selected arbitrarily or determined from the input

using an appropriate criterion, such as minimizing prediction error via cross-validation, satisfying model-selection heuristics (e.g., AIC or BIC), or optimizing residual metrics under known structural constraints. Alternatively,

may be fixed at benchmark values, e.g.,

, or based on an error rule, e.g.,

,

. The final value

is obtained by solving a convex programming problem, which, in practical implementations,

is efficiently computed with the help of numerical solvers.

This formalization of the process blocks ensures that the CLSP estimator yields a unique final solution under regularization weight owing to the strict convexity of the objective function (consult Theorem 1 for a proof). For , the solution remains convex but may not be unique unless additional structural assumptions are imposed. In the specific case of , the estimator reduces to the Minimum-Norm Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (MNBLUE), or, alternatively, to a block-wise -MNBLUE across reduced problems (for a proof, consult Theorem 2 and its corollaries).

Theorem 1. Let be the r-iterated estimate obtained in the first step of the CLSP algorithm, and let be the second-step correction obtained through convex programming by solving (i.e., the regularization parameter excludes a pure Lasso-type correction), then the final solution is unique.

Proof. Let denote the linear estimator obtained via the Bott-Duffin inverse, defined on a subspace determined by a symmetric idempotent matrix , and producing a conditionally unbiased estimate over that subspace. The Bott-Duffin inverse is given by , and the estimate is unique if . In this case, is the unique minimum-norm solution in . In all other cases, the solution set is affine and given by , where the null-space component represents degrees of freedom not fixed by the constraint , hence is not unique. At the same time, the second-step estimate is obtained by minimizing the function over the affine (hence convex and closed) constraint set . Under , the quadratic term contributes a positive-definite Hessian to the objective function, making it a strictly convex parabola-like curvature, and, given , the minimizer exists and is unique. Therefore, the CLSP estimator with yields a unique . □

Corollary 1. Let the final solution be , where denotes the Bott-Duffin inverse on a subspace defined by a symmetric idempotent matrix . Then (one-step) is unique iff . Else, the solution set is affine and given by , which implies that the minimizer is not unique, i.e., .

Corollary 2. Let be the final solution obtained in the second step of the CLSP estimator by solving (i.e., the regularization parameter is set to , corresponding to a Lasso correction). Then the solution exists and the problem is convex. The solution is unique iff the following two conditions are simultaneously satisfied: (1) the affine constraint set intersects the subdifferential of at exactly one point, and (2) the objective function is strictly convex on , which holds when intersects the interior of at most one orthant in . In all other cases, the minimizer is not unique, and the set of optimal solutions forms a convex subset of the feasible region ; that is, the final solution , where is convex and .

Theorem 2. Let be the r-iterated estimate obtained in the first step of the CLSP algorithm, and let be the second-step correction obtained through convex programming by solving (i.e., the regularization parameter is , corresponding to a Ridge correction), then is the Minimum-Norm Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (MNBLUE) of under the linear(ized) constraints set by the canonical form of the CLSP.

Proof. Let

denote the linear estimator obtained via the Bott-Duffin inverse, defined on a subspace determined by a symmetric idempotent matrix

, and producing a conditionally unbiased estimate over that subspace. The Bott-Duffin inverse is

and the estimate

is unique if

. Given the linear model derived from the canonical form

, where

are residuals with

, it follows that

. Substituting

yields

. By the generalized projection identity

, one obtains

, which proves conditional unbiasedness on

(and full unbiasedness if

). Subsequently, the second-step estimate

is obtained by minimizing the squared Euclidean distance between

and

, subject to the affine constraint

, which corresponds, in geometric and algebraic terms, to an orthogonal projection of

onto the affine (hence convex and closed) subspace

. By Theorem 1, the unique minimizer

exists and is given explicitly by

. This expression satisfies the first-order optimality condition of the convex program and ensures that

is both feasible and closest (in the examined

-norm) to

among all solutions in

. Therefore,

is (1) linear (being an affine transformation of a linear estimator), (2) unbiased (restricted to the affine feasible space), (3) minimum-norm (by construction), and (4) unique (by strict convexity). By the generalized Gauss-Markov theorem [

33] (Chapter 7, Definition 4, p. 139), [

34] (Chapter 8, Section 3.2, Theorem 2, p. 287), it follows that

is the

Minimum-Norm Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (MNBLUE) under the set of linear(ized) constraints

. □

Corollary 3. Let the canonical system be consistent and of full column rank, , , and . Suppose that the CLSP algorithm terminates after Step 1 and that , such that . Then, provided the classical linear model , where and , holds, the CLSP estimator is equivalent to OLS while is the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE).

Corollary 4.

Let be the r-iterated estimate obtained via the Bott-Duffin inverse, defined on a subspace determined by a symmetric idempotent matrix , and producing a conditionally unbiased estimate over that subspace. Subsequently, the estimate is obtained by minimizing the squared Euclidean distance between and , subject to the affine constraint , such that . Then each is the Minimum-Norm Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (MNBLUE) under the linear(ized) constraints defined by the canonical form of each reduced system of the CLSP, and is a block-wise-MNBLUEcorresponding to each of the reduced problems.

4. Numerical Stability of the Solutions and

The numerical stability of solutions in each step of the CLSP estimator — both the (iterated if

) first-step estimate

(alternatively,

) and the final solution

(alternatively,

) — depends on the condition number of the design matrix,

, which, given its block-wise formulation in Equation (

3), can be analyzed as a function of the

“canonical” constraints matrix as a fixed,

r-invariant, part of

. For both full and reduced problems,

sensitivity analysis of

with respect to constraints (i.e., rows) in

, especially focused on their reduction (i.e., dropping rows), is performed based on the decomposition:

where

, denotes the constraint-induced,

r-variant, part of

, and, when the rows of

lie entirely within

, i.e.,

,

i.e., a change in

consists of a (lateral) constraint-side effect,

, induced by structural modifications in

, an (axial) model-side effect,

, reflecting propagation into

— where

and

,

, and

(for a “partitioned” decomposition of

given the structure of

, see

Appendix A.2), — and the (non-linear) term,

.

The condition number of

,

, the change of which determines the constraint-side effect,

, can be itself analyzed with the help of pairwise angular measure between row vectors

, where

. For any two

(alternatively, in a centered form,

, with

),

, the cosine of the angle between them

(alternatively, a Pearson correlation coefficient

), captures their angular alignment — values close to

indicate near-collinearity and potential ill-conditioning, whereas values near 0 imply closeness to orthogonality and improved numerical stability:

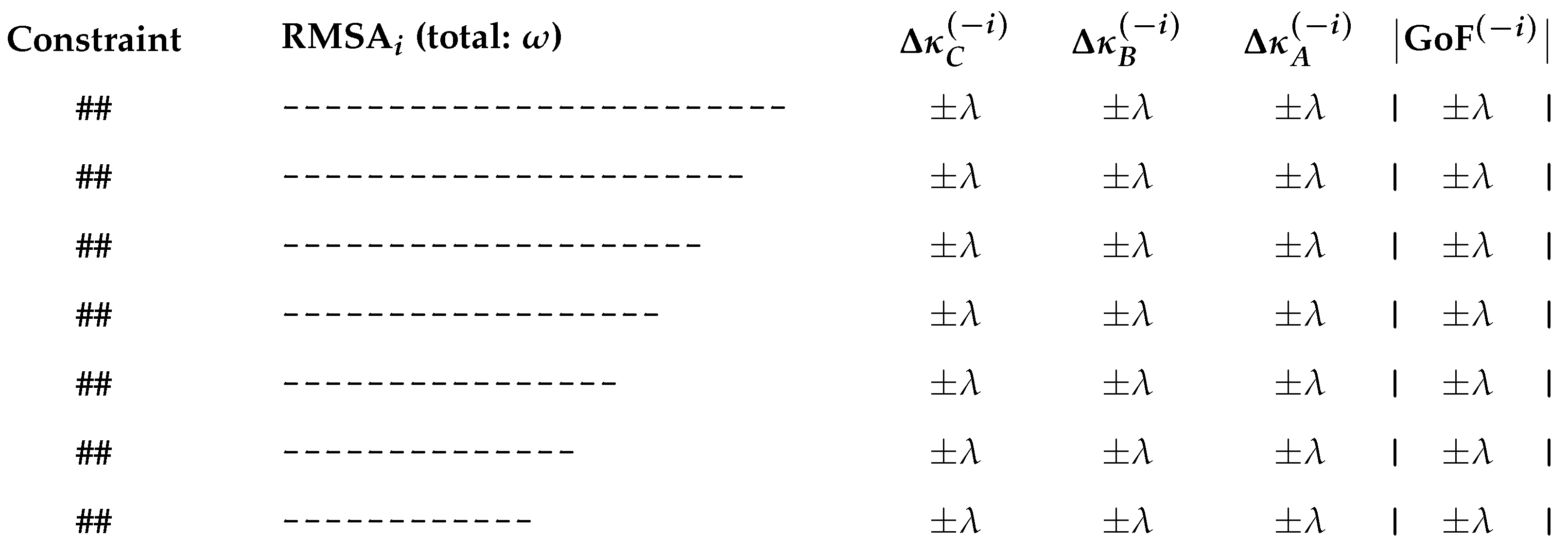

The pairwise angular measure can be aggregated across

j (i.e., for each row

) and jointly across

(i.e., for the full set of

unique row pairs of

), yielding a scalar summary statistic of angular alignment, e.g., the

Root Mean Square Alignment (RMSA):

where

captures the average angular alignment of constraint

i with the rest, while RMSA evaluates the overall constraint anisotropy of

. As with individual cosines

(alternatively,

), values near 1 suggest collinearity and potential numerical instability, while values near 0 reflect angular dispersion and reduced condition number

. The use of squared cosines

(alternatively,

) in contrast with other metrics (e.g., absolute values) maintains consistency with the Frobenius norms in

and assigns greater penalization to near-collinear constraints in

. Furthermore, a combination of

,

, and the above-described

marginal effects, obtained by excluding row

i from

— namely,

,

, and

if

— together with the corresponding changes in the

goodness-of-fit statistics from the solutions

and

(consult Section 5), can be visually presented over either all

i, or a filtered subset, such that

, as depicted in

Figure 5.

5. Goodness of Fit of the Solutions and

Given the hybrid structure of the CLSP estimator — comprising a least-squares-based (iterated if ) initial estimate (or ), followed by a regularization-based final solution (or ) — and the potentially ill-posed or underdetermined nature of the problems it addresses, standard goodness-of-fit methodology — such as explained variance measures (e.g., the coefficient of determination, ), error-based metrics (e.g., Root Mean Square Error, RMSE, for comparability with the above-described RMSA), hypothesis tests (e.g., F-tests in the analysis of variance and t-tests at the coefficient level), or confidence intervals (e.g., based on Student’s t- and the normal distribution) — requires appropriate adaptation to be uniformly applied to both full and reduced problems, with some statistics applicable only to Step 1 and/or under specific conditions (namely, the ANOVA F- tests, t-tests, and confidence intervals). In response, several more robust metrics are developed below: partial , normalized RMSE, t-test for the mean of the NRMSE, and a diagnostic interval based on the condition number.

For the

explained variance measures, the block-wise formulation of the full vector of unknowns

, — obtained from

(where

is the vector of model (target) variables and

,

, is a vector of latent variables present only in the constraints) and a vector of slack variables

, — the design matrix

, where

is the “canonical” model matrix, and the input

, all necessitate a

“partial” to isolate the estimated variables

, where, given the vector

,

provided that

,

, i.e., applicable strictly to (over)determined problems. If

, then

and

reduces to the classical

.

Next, for the

error-based metrics, independent of

and thus more robust across underdetermined cases (in contrast to

), a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) can be defined for both (a) the full solution

, via

, serving as an overall measure of fit, and (b) its variable component

, via

, quantifying the fit quality with respect to the estimated target variables only (in alignment with

). Then, to enable cross-model comparisons and especially its use in hypothesis testing (see below), RMSE must be normalized — typically by the standard deviation of the reference input,

or

, — yielding the

Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE) comparable across datasets and/or models (e.g., in the

t-test for the mean of the NRMSE):

The standard deviation is preferred in statistical methodology over the alternatives (e.g., max-min scaling or range-based metrics) because it expresses residuals in units of their variability, producing a scale-free measure analogous to the standard normal distribution. It is also more common in practical implementations (such as Python’s sklearn or MATLAB).

Also, for the

hypothesis tests, classical ANOVA-based

F-tests and coefficient-level

t-tests — relying on variance decomposition and residual degrees of freedom — are applicable exclusively to the least-squares-based (iterated if

) first-step estimate

and to the final solution

, given a strictly overdetermined

, i.e.,

,

(an OLS case), and under the assumption of homoscedastic and normally distributed residuals. Then, in the case of the

F-tests, the test statistics follow the distributions (a)

and (b)

, a Wald-type test on a linear restriction — with the degrees of freedom

and

if

is a vector of coefficients from a linear(ized) model with an intercept and

and

otherwise, — yielding (a)

and (b)

, where

is a restriction matrix:

In the case of the

t-tests, (a)

(

n test statistics) and (b)

(

p test statistics), given that the partial result

or

is a subvector of length

p of

(also

), yielding (a)

and (b)

:

An alternative hypothesis test — robust to both

and the step of the CLSP algorithm, i.e., valid for the final solution

(in contrast to the classical ANOVA-based

F-tests or coefficient-level

t-tests) — can be a

-

test for the mean of the NRMSE, comparing the observed

(as

), both full and partial, to the mean of a simulated sample

, generated via

Monte Carlo simulation, typically from a uniformly (a structureless baseline) or normally (a “canonical” choice) distributed random input

or

— both the distributions being standard, — for

, where

T is the sample size, yielding

with

and

for the two-sided test and

for the one-sided one:

justified when

is normally distributed or approximately normally distributed based on the Lindeberg-Lévy Central Limit Theorem (CLT), i.e., when

(as a rule of thumb) for

. Then,

denotes a good fit for

in the sense that

does not significantly deviate from the simulated distribution, i.e.,

should not be rejected for the CLSP model to be considered statistically consistent. In practical implementations (such as Python, R, Stata, SAS, Julia, and MATLAB/Octave),

T typically ranges from 50 to 50,000.

Finally, for the

confidence intervals, classical formulations for (a)

,

, and (b)

,

, — based on Student’s

t- and, asymptotically, the standard normal distribution,

and

, — are equivalently exclusively applicable to the least-squares-based (iterated if

) first-step estimate

and to the final solution

under a strictly overdetermined

, i.e.,

,

(an OLS case), and assuming homoscedastic and normally distributed residuals. Then, provided

, such as

, the confidence intervals for (a)

and (b)

are:

given that the partial result

or

is a subvector of length

p of

or

. For

, the distribution of the test statistic,

, approaches a standard normal one,

, based on the CLT, yielding an alternative notation for the confidence intervals:

An alternative “confidence interval” — equivalently robust to both

and the step of the CLSP algorithm, i.e., valid for the final solution

(in contrast to the classical Student’s

t- and, asymptotically, the standard normal distribution-based formulations) — can be

constructed deterministically via condition-weighted bands, relying on componentwise numerical sensitivity. Let the residual vector

be a (backward) perturbation in

, i.e.,

. Then, squaring both sides of the classical first-order inequality

yields

, where

—

and

being the biggest and smallest singular values of

— iff

. Under a uniform relative squared perturbation (a heuristic allocation of error across components as a simplification, not an assumption) of

, rearranging terms and taking square roots of both sides gives

and a condition-weighted “confidence” band:

which is a

diagnostic interval based on the condition number for

, consisting of (1) a canonical-form system conditioning,

, (2) a normalized model misfit,

, and (3) the “scale” of the final solution,

, without probabilistic assumptions. A perturbation in one or more of these three components, e.g., caused by a change in RMSA resulting from dropping selected constraints (consult Section 4), will affect the limits of

. Under a perfect fit, the interval collapses to

and, for

, tends to be very wide.

To summarize, the CLSP estimator requires a goodness-of-fit framework that reflects both its algorithmic structure and numerical stability. Classical methods remain informative but are valid only under strict overdetermination (), full-rank design matrix , and distributional assumptions (primarily, homoscedasticity and normality of residuals). In contrast, the proposed alternatives — (a) partial , (b) NRMSE and , (c) t-tests for the mean of NRMSE with the help of Monte Carlo sampling, and (d) condition-weighted confidence bands — are robust to rank deficiency and ill-posedness, making them applicable in practical implementations (namely, CLSP packages in Python, R, and Stata).

6. Special Cases of CLSP Problems: APs, CMLS, and LPRLS/QPRLS

The structure of the

design matrix in the CLSP estimator, as defined in Equation (

3) (consult Section 3), allows for accommodating a selection of special-case problems, out of which three cases are covered, but the list may not be exhaustive. Among others, the CLSP estimator is, given its ability to address ill-posed or underdetermined problems under linear(ized) constraints, efficient in addressing what can be referred to as

allocation problems (APs) (or, for flow variables,

tabular matrix problems, TMs) — i.e., in most cases, underdetermined problems involving matrices of dimensions

to be estimated, subject to known row and column sums, with the degrees of freedom (i.e., nullity) equal to

, where

is the number of active (non-zero) slack variables and

is the number of known model (target) variables (e.g., a zero diagonal), — whose design matrix,

, comprises a (by convention)

row-sum-column-sum constraints matrix (where

), a

model matrix — in a trivial case,

— a sign

slack matrix, and either a

zero matrix (if

) or a (standard) reverse-sign

slack matrix (provided

):

where

and

denote groupings of the

m rows and

p columns, respectively, into

i and

j homogeneous blocks (when no grouped row or column sums are available,

); with real-world examples including: (a) input-output tables (national, inter-country, or satellite); (b) structural matrices (e.g., trade, country-product, investment, or migration); (c) financial clearing and budget-balancing; and (d) data interpolations (e.g., quarterly data from annual totals). Given the available literature in 2025, the first pseudoinverse-based method of estimating input-output tables was proposed in Pereira-López et al. [

95] and the first APs (TMs)-based study was conducted in Bolotov [

16], attempting to interpolate a world-level (in total, 232 countries and dependent territories) “bilateral flow” matrix of foreign direct investment (FDI) for the year 2013, based on known row and column totals from UNCTAD data (aggregate outward and inward FDI). The estimation employed a minimum-norm least squares solution under APs (TMs)-style equality constraints, based on the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse of a “generalized Leontief structural matrix”, rendering it equivalent to the initial (non-regularized) solution in the CLSP framework,

. As a rule of thumb, AP (TM)-type problems are rank deficient for

with the CLSP being a

unique (if

) and an

MNBLUE (if

) estimator (consult Section 3).

In addition to the APs (TMs), the CLSP estimator is also efficient in addressing what can be referred to as

constrained-model least squares (CMLS) (or, more generally,

regression problems, RPs) — i.e., (over)determined problems involving vectors of dimension

p to be estimated with (standard) OLS degrees of freedom, subject to, among others, linear(ized) data matrix

-related (in)equality constraints,

, where

is a transformation matrix of

, such as the

i-th difference or shift (lag/lead), and

, — whose design matrix,

, consists of a

u-block constraints matrix (

),

, a data matrix as the

model matrix , a (standard) sign

slack matrix , and either a

zero matrix (if

) or a (standard) reverse-sign

slack matrix (when

):

with real-world examples including: (a) previously infeasible textbook-definition econometric models of economic (both micro and macro) variables (e.g., business-cycle models), (b) additional constraints applied to classical econometric models (e.g., demand analysis). Given the available literature in 2025, the first studies structurally resembling CMLS (RPs) were conducted in Bolotov [

15], Bolotov [

96], focusing on the decomposition of the long U.S. GDP time series into trend (

) and cyclical (

) components — using exponential trend, moving average, Hodrick-Prescott filter, and Baxter-King filter — under constraints on its first difference, based on the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) delimitation of the U.S. business cycle.

was then modeled with the help of linear regression (OLS), based on an

n-th order polynomial with extreme values smoothed via a factor of

and simultaneously penalized via an

n-th or (

)-th root,

, where

are the model parameters,

are the values of the (externally given) stationary points, and

is the error. The order of the polynomial and the ad-hoc selection of smoothing and penalizing factors, however, render such a method inferior to the CLSP. Namely, the

unique (if

) and an

MNBLUE (if

) CLSP estimator (consult Section 3) allows (a) presence of inequality constraints and (b) their ill-posed formulations.

Finally, the CLSP estimator can be used to address (often unsolvable using classical solvers) underdetermined and/or ill-posed — caused by too few and/or mutually inconsistent or infeasible constraints, as in the sense of Whiteside et al. [

93] and Blair [

76], Blair [

94], — LP and QP problems, an approach hereafter referred to as

linear/quadratic programming via regularized least squares (LPRLS/QPRLS): CLSP substitutes the original objective function of the LP/QP problem with the canonical form

(i.e., focusing solely on the problem’s constraints, without distinguishing between the LP and QP cases) with

being the solution of the original problem — where

is a permutation matrix, and

and

represent the linear(ized) inequality and equality constraints,

— and the degrees of freedom being equal — under the classical formalization of a primal LP/QP problem (consult Section 2) — to

, where

p is the length of

,

is the number of introduced slack variables, while

,

, and

denote the numbers of upper-bound, equality, and non-negativity constraints, respectively (under the standard assumption that all model variables are constrained to be non-negative). In the LPRLS/QPRLS, the design matrix,

, by the definition of LP/QP, is

r-invariant and consists of a block constraints matrix

, where

,

, and

, a (standard) sign

slack matrix , and

:

Given the available literature in 2025, the first documented attempts to incorporate LS into LP and QP included, among others, Dax’s LS-based steepest-descent algorithm [

85] and the primal-dual NNLS-based algorithm (LSPD) [

86], whose structural restrictions — in terms of well-posedness and admissible constraints — can be relaxed through LPRLS/QPRLS, still guaranteeing a

unique (if

) and an

MNBLUE (if

) solution (consult Section 3).

7. Monte Carlo Experiment and Numerical Examples

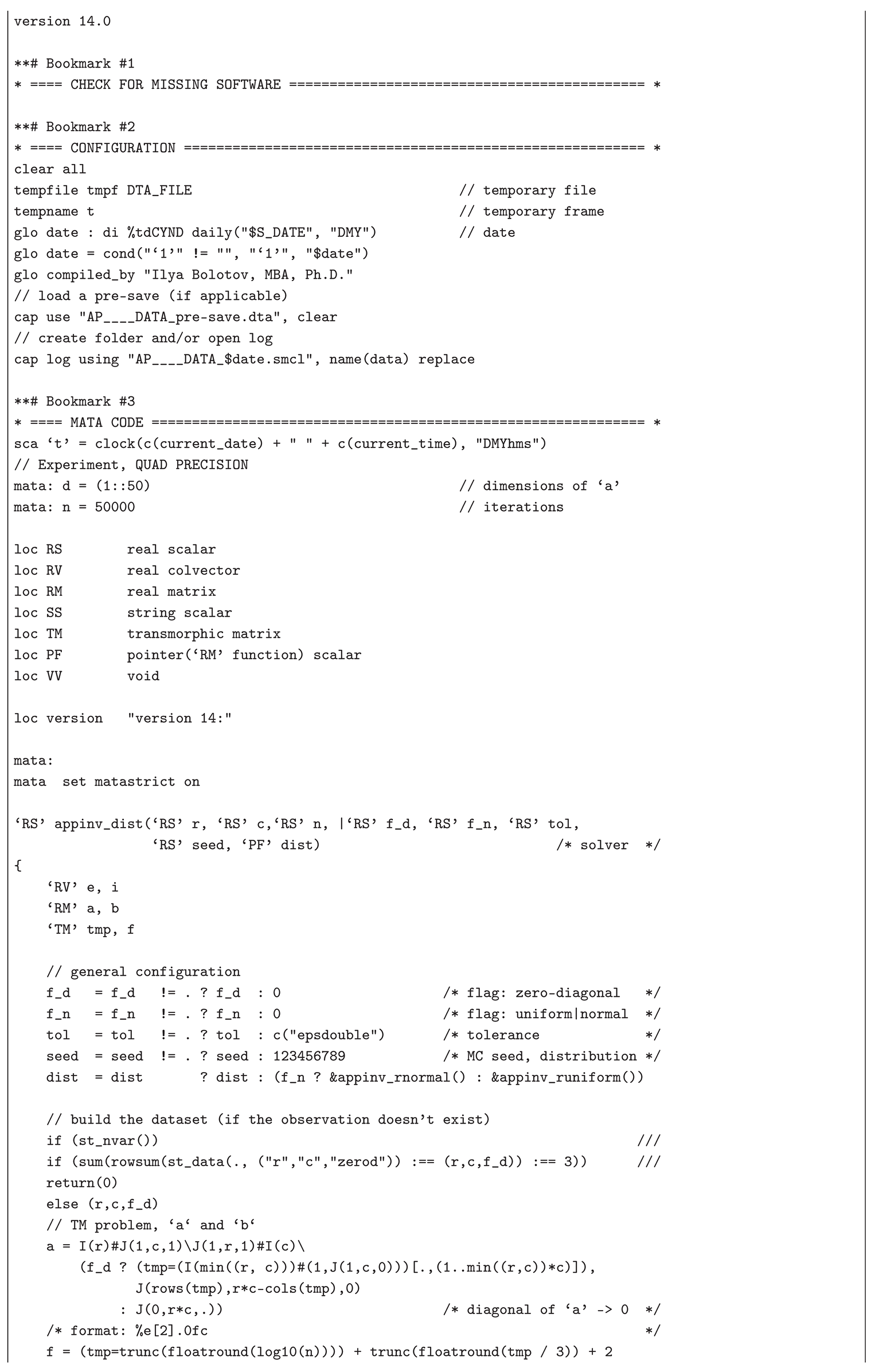

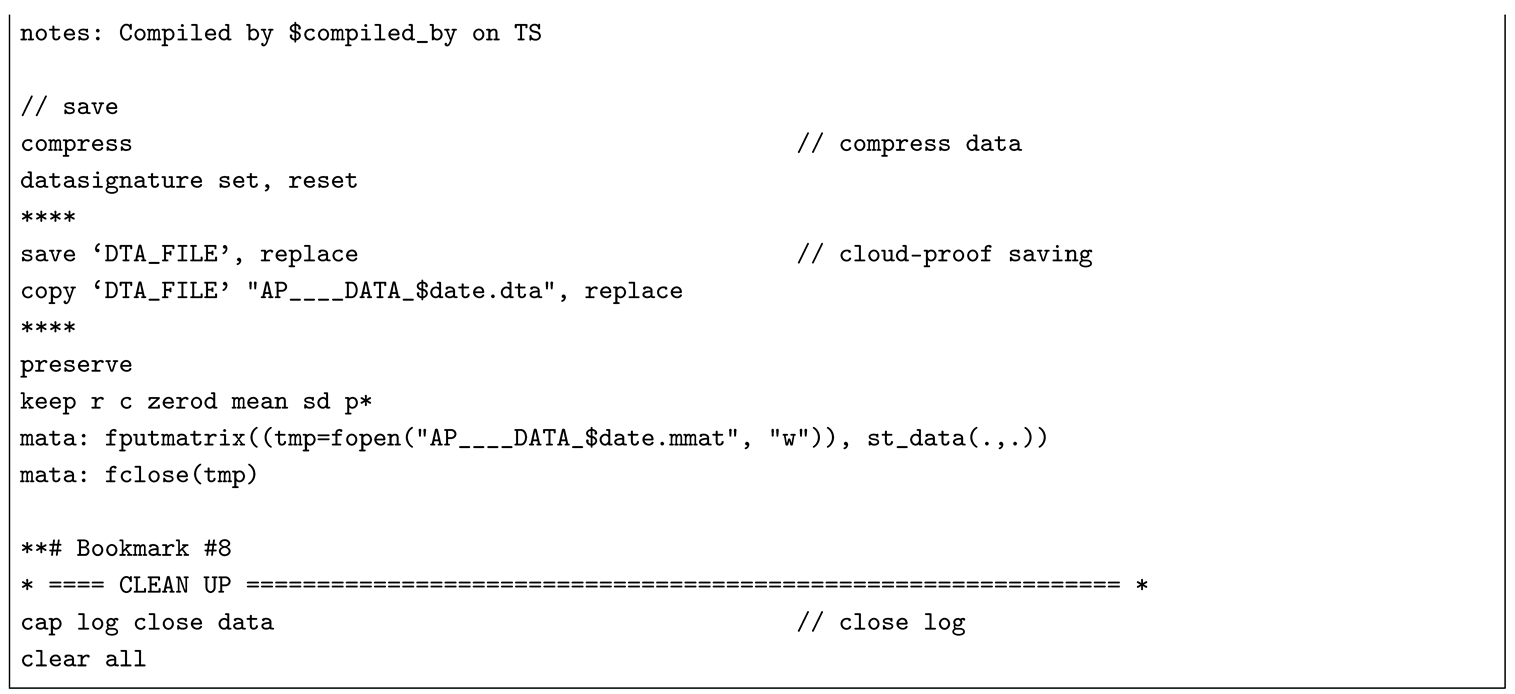

The Monte Carlo experiment and the simulated examples presented below illustrate the applicability of the CLSP to the AP (TM), CMLS (RP), and LPRLS/QPRLS problems. The standardized form of

in the APs (TMs), i.e.,

, with given

and

r, enables

large-scale simulation of the distribution of NRMSE — a robust goodness-of-fit metric for the CLSP — through

repeated random trials under varying matrix dimensions

, row and column group sizes

i and

j, and composition of

, inferring asymptotic percentile means and standard deviations for practical implementations (e.g., the

t-test for the mean). This text presents the results of a simulation study on the distribution of the NRMSE from the first-step estimate

(implementable in standard econometric software without CLSP modules) for

,

,

,

, and

, conducted in Stata/MP (set to version 14.0) with the help of Mata’s 128-bit floating-point cross-product-based

quadcross() for greater precision and SVD-based

svsolve() with a strict tolerance of

c("epsdouble") for increased numerical stability, and a random-variate seed

123456789 (see

Appendix B.1 containing a list of dependencies [

97] and the Stata .do-file). In this 50,000-iterations Monte Carlo simulation study, spanning matrix dimensions from 1×2 and 2×1 up to 50×50, random normal input vectors

were generated for each run, applied with and without zero diagonals (i.e., if, under

,

is reshaped into a (

)-matrix

, then

). Thus, a total of 249.9 million observations (

) was obtained via the formula

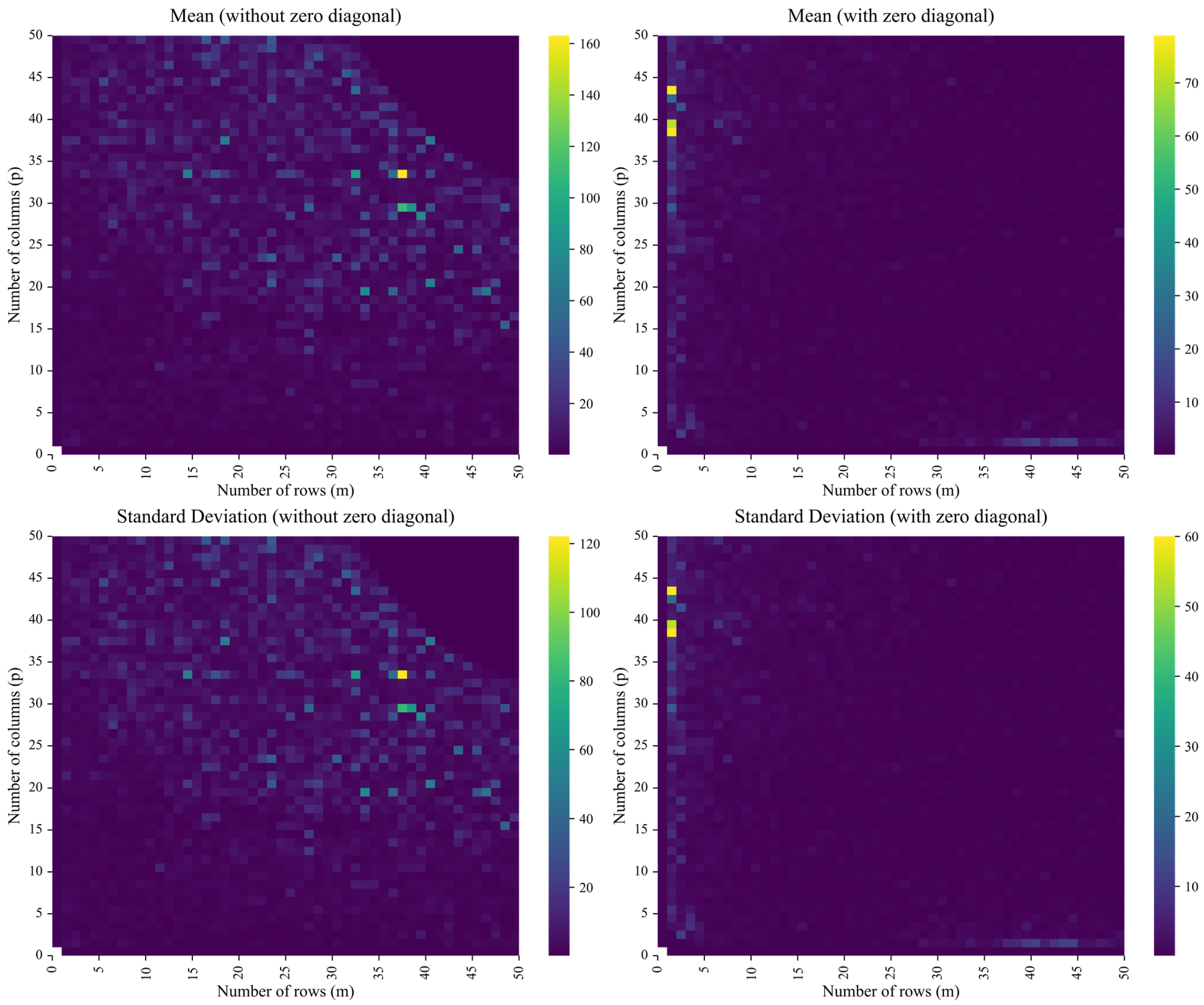

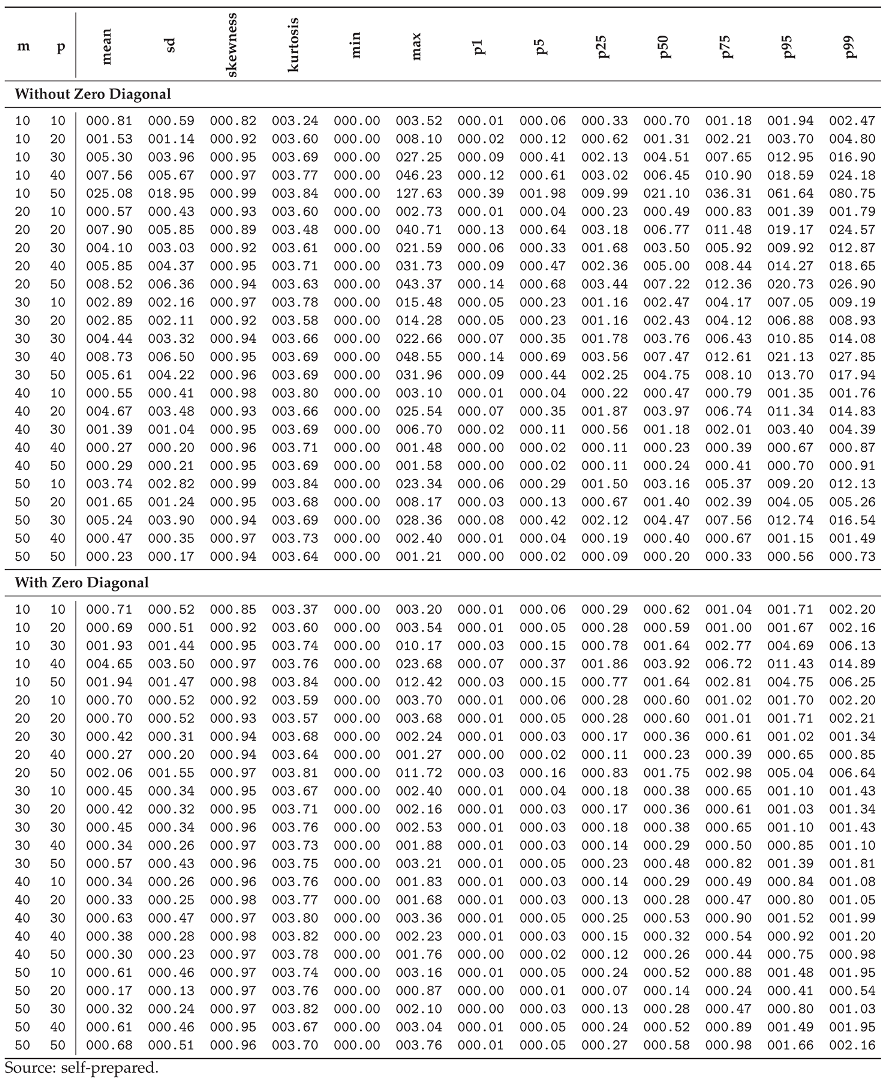

, resulting in 4,998 aggregated statistics of the asymptotic distribution, assuming convergence:

mean,

sd,

skewness,

kurtosis,

min,

max, as well as

p1–p99, as presented in

Figure 6 (depicting the intensity of its first two moments,

mean and

sd) and

Table 2 (reporting a subset of all thirteen statistics for

).

From the results of the Monte Carlo experiment, it is observable that: (1) the NRMSE from the first-step estimate and its distributional statistics exhibit increasing stability and boundedness as matrix dimensions increase — specifically, for , both the mean and sd of NRMSE tend to converge, indicating improved estimator performance (e.g., under no diagonal restrictions, at , and , while at , and ); (2) the zero-diagonal constraints () reduce the degrees of freedom and lead to a much more uniform and dimensionally stable distribution of NRMSE across different matrix sizes (e.g., at , mean drops to and sd to , while at , mean rises slightly to and sd to ); and (3) the distribution of NRMSE exhibits mild right skew and leptokurtosis — less so for the zero-diagonal case: under no diagonal restriction, the average skewness is with a coefficient of variation of (i.e., ), and the average kurtosis is with a variation of ; whereas under the zero-diagonal constraint, skewness averages with only variation, and kurtosis averages with variation (i.e., ). To sum up, the larger and less underdetermined (i.e., in an AP (TM) problem, the larger the block of ) the canonical system , the lower the estimation error (i.e., the mean NRMSE) and its variance, and, provided a stable limiting law for NRMSE exists, the skewness and kurtosis from the simulations drift toward 0 and 3, respectively, consistent with — but not proving — a convergence toward a standard-normal distribution.

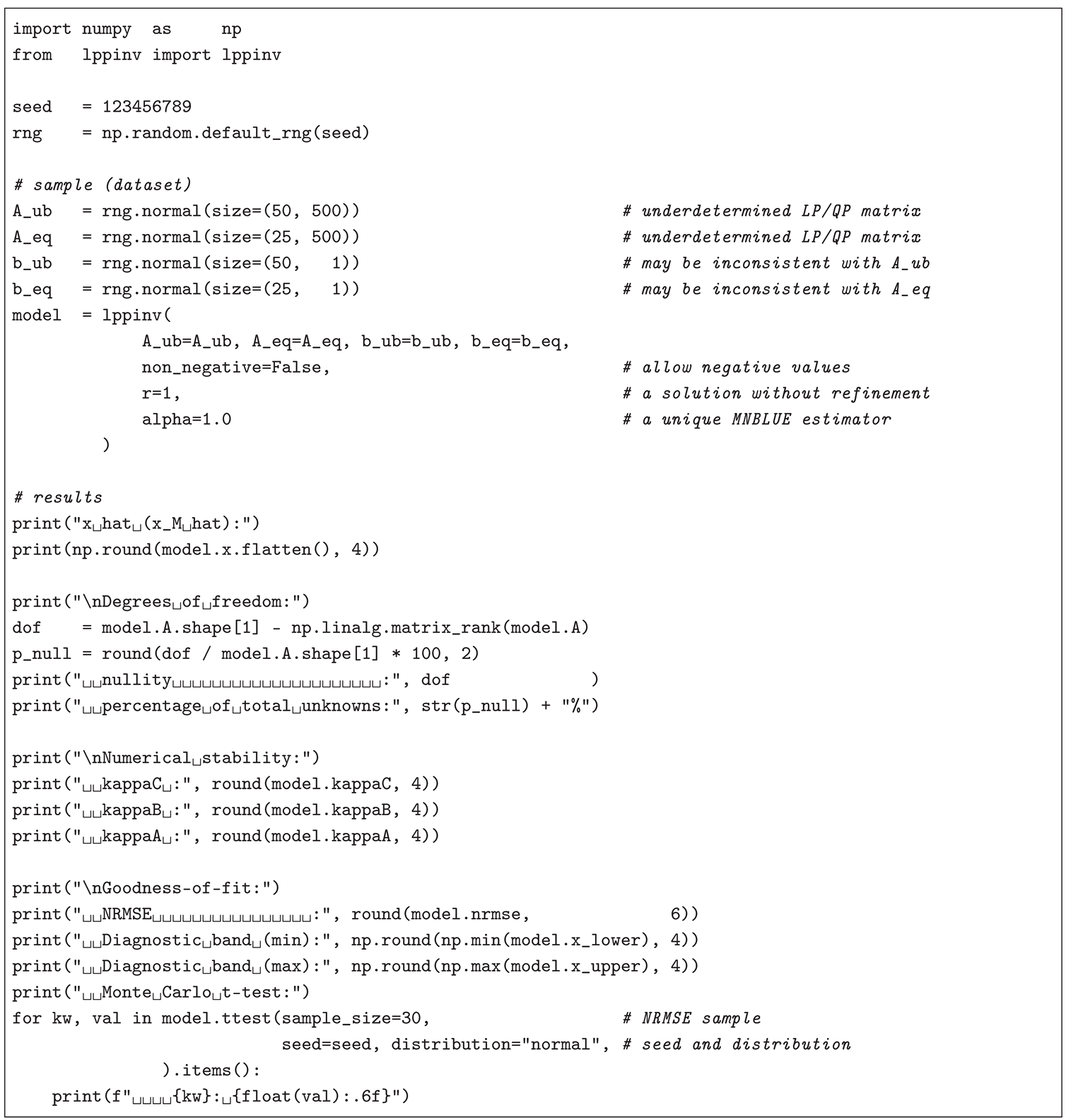

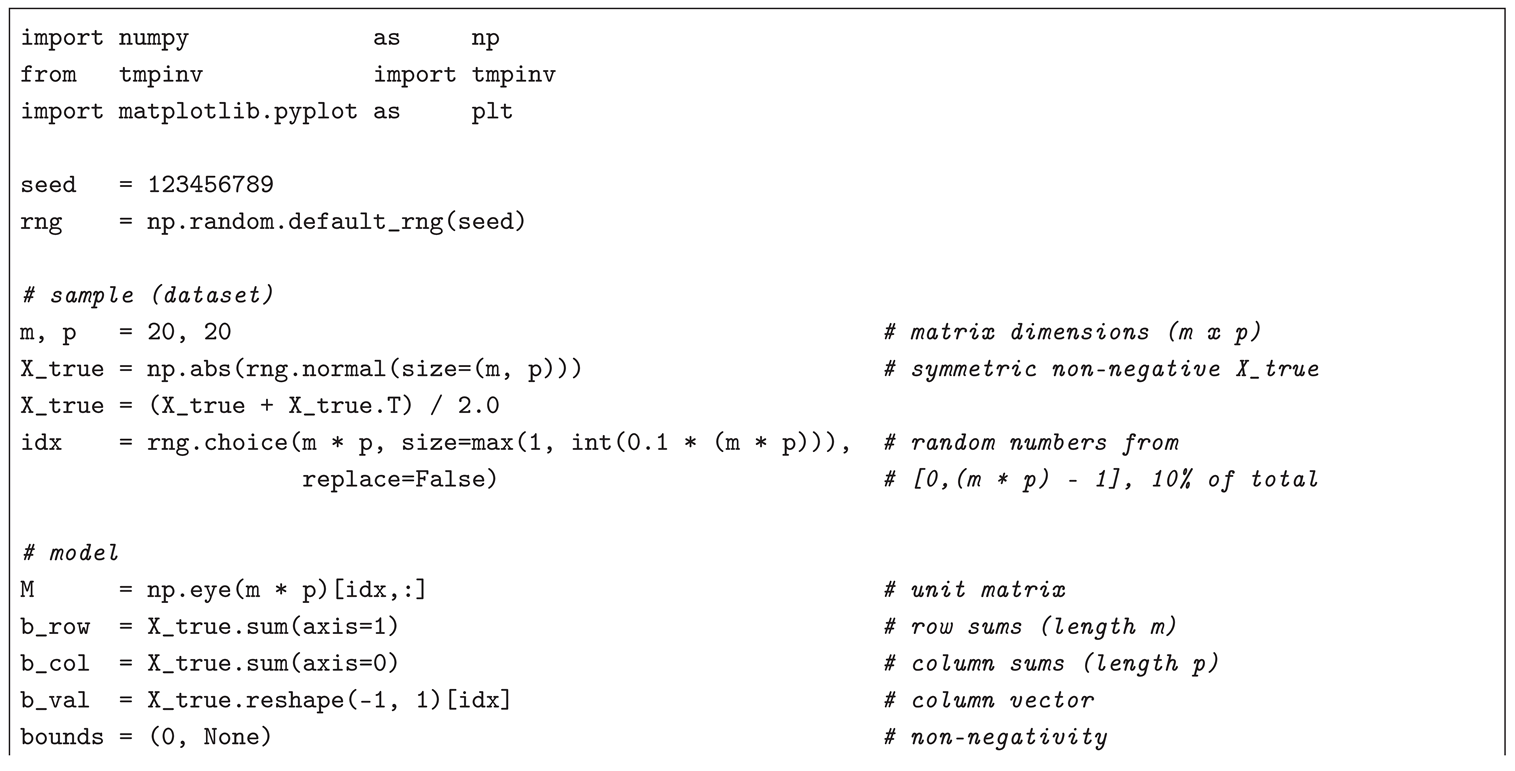

For an illustration of the applicability of the CLSP to the APs (TMs), CMLS (RPs), and LPRLS/QPRLS, the author-developed cross-platform Python 3 module,

pyclsp (version ≥ 1.3.0, available on PyPI) [

98], — together with its interface co-modules for the APs (TMs),

pytmpinv (version ≥ 1.2.0, available on PyPI) [

99], and the LPRLS/QPRLS,

pylppinv (version ≥ 1.3.0, available on PyPI) [

100] (a co-module for the CMLS (RPs) is not provided, as the variability of

within the

,

, block of

prevents efficient generalization), — is employed for a sample (dataset) of

i random elements

(scalars, vectors, or matrices depending on context) and their transformations, drawn independently from the standard normal distribution, i.e.,

, under the mentioned random-variate seed

123456789 (configured for consistency with the above-described Monte Carlo experiment). Thus, using the cases of (a) a (non-negative symmetric) input-output table and (b) a (non-negative) zero-diagonal trade matrix as two

AP (TM) numerical examples, this text simulates problems similar to the ones addressed in Pereira-López et al. [

95] and Bolotov [

16]: an underdetermined

is estimated — from row sums, column sums, and

k known values of two randomly generated matrices (a)

and (b)

,

, subject to (a)

and (b)

— via CLSP assuming

,

,

, and

. The Python 3 code, based on

pytmpinv and two other modules, installable by executing

pip install matplotlib numpy pytmpinv==1.2.0, for (a)

and

and (b)

— estimated with the help of

-MNBLUE across

reduced models

assuming an estimability constraint of

— and

, with a non-iterated (

), unique (

), and MNBLUE (

) (two-step) CLSP solution, is implemented in (a) Listing and (b) Listing (e.g., to be executed in a Jupyter Notebook).

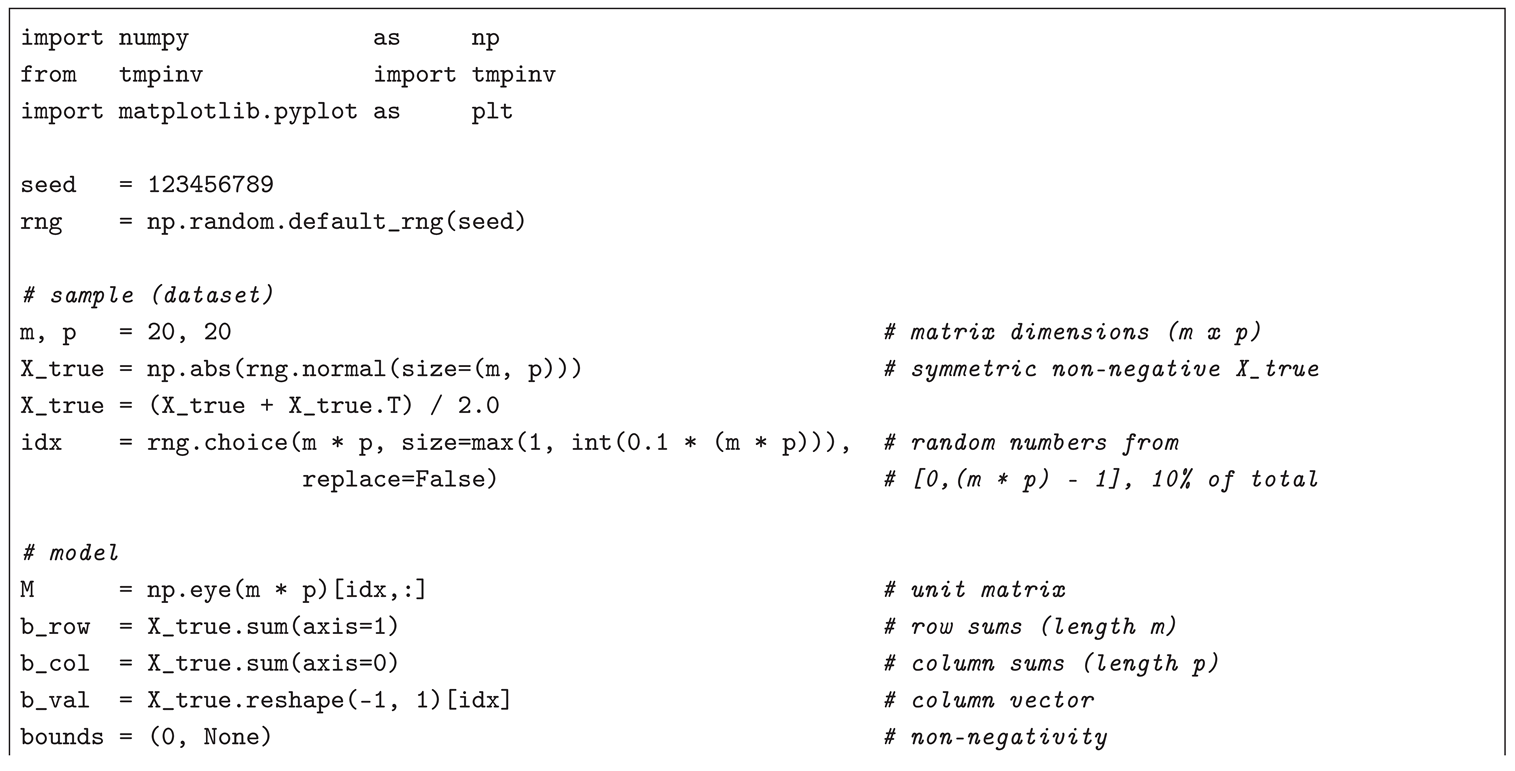

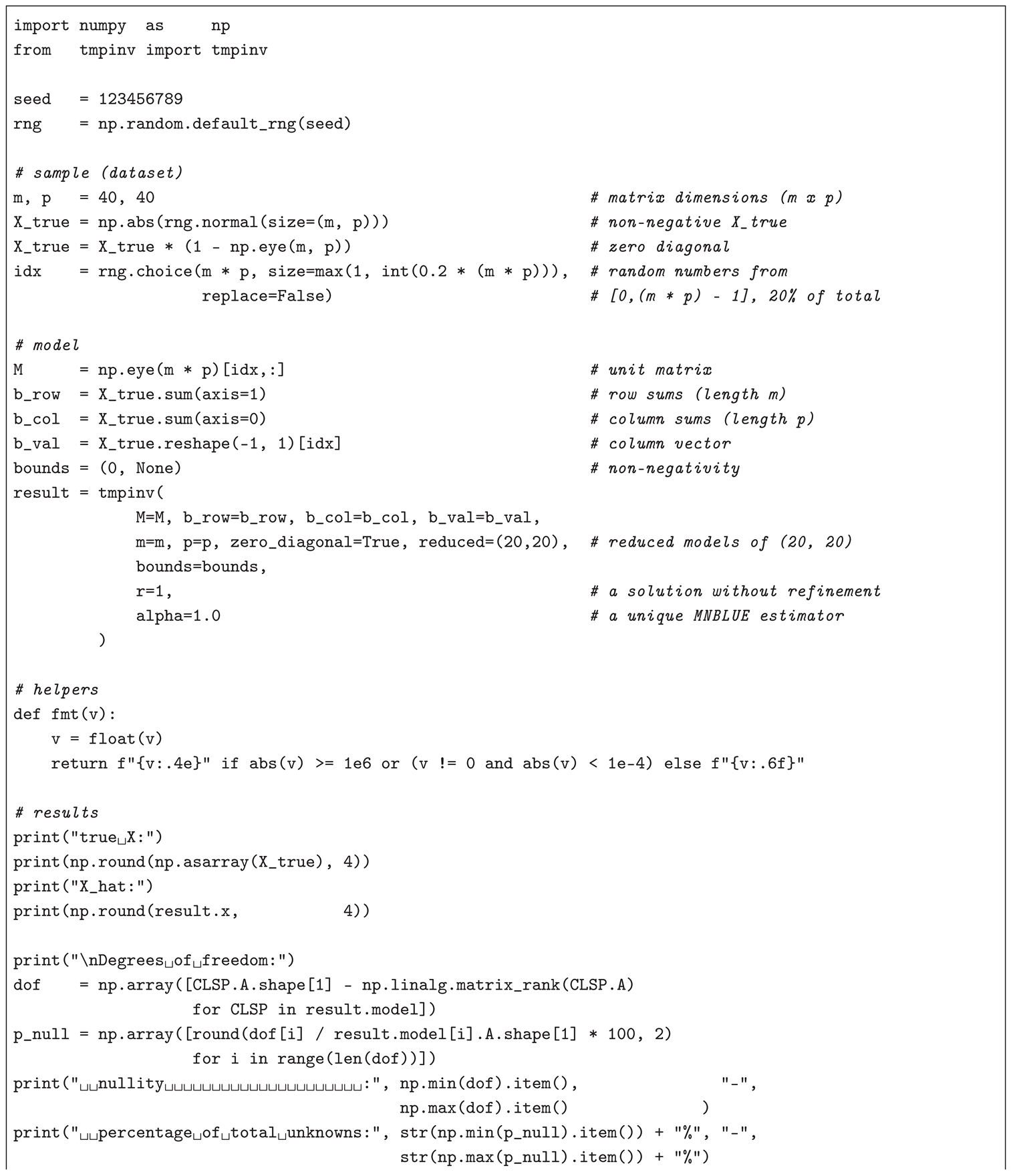

|

Listing 1. Simulated numerical example for a symmetric input-output-table-based AP (TM) problem. |

|

|

In case (a) (see Listing for code), the number of model (target) variables is with a nullity of , corresponding to 80.25% of the total unknowns. Given the simulation of , a matrix unknown in real-world applications, — i.e., CLSP is used to estimate the elements of an existing matrix from its row sums, , column sums, , and a randomly selected 10% of its entries, , — the model’s goodness of fit can be measured by a user-defined (i.e., CLSP achieves an improvement of over a hypothetical naïve predictor reproducing the known 10% entries of and yielding a , but still a modest value of , i.e. a relatively large error, ) with lying within wide condition-weighted diagnostic intervals reflecting the ill-conditioning of the strongly rectangular , , and only the left-sided Monte Carlo-based t-test for the mean of the NRMSE (on a sample of 30 NRMSE values obtained by substituting with ) suggesting consistency with expectations (i.e., with the ). In terms of numerical stability, with a low , as confirmed by the correlogram produced in matplotlib, indicating a well-chosen constraints matrix, even given the underdeterminedness of the model (which also prevents a better fit).

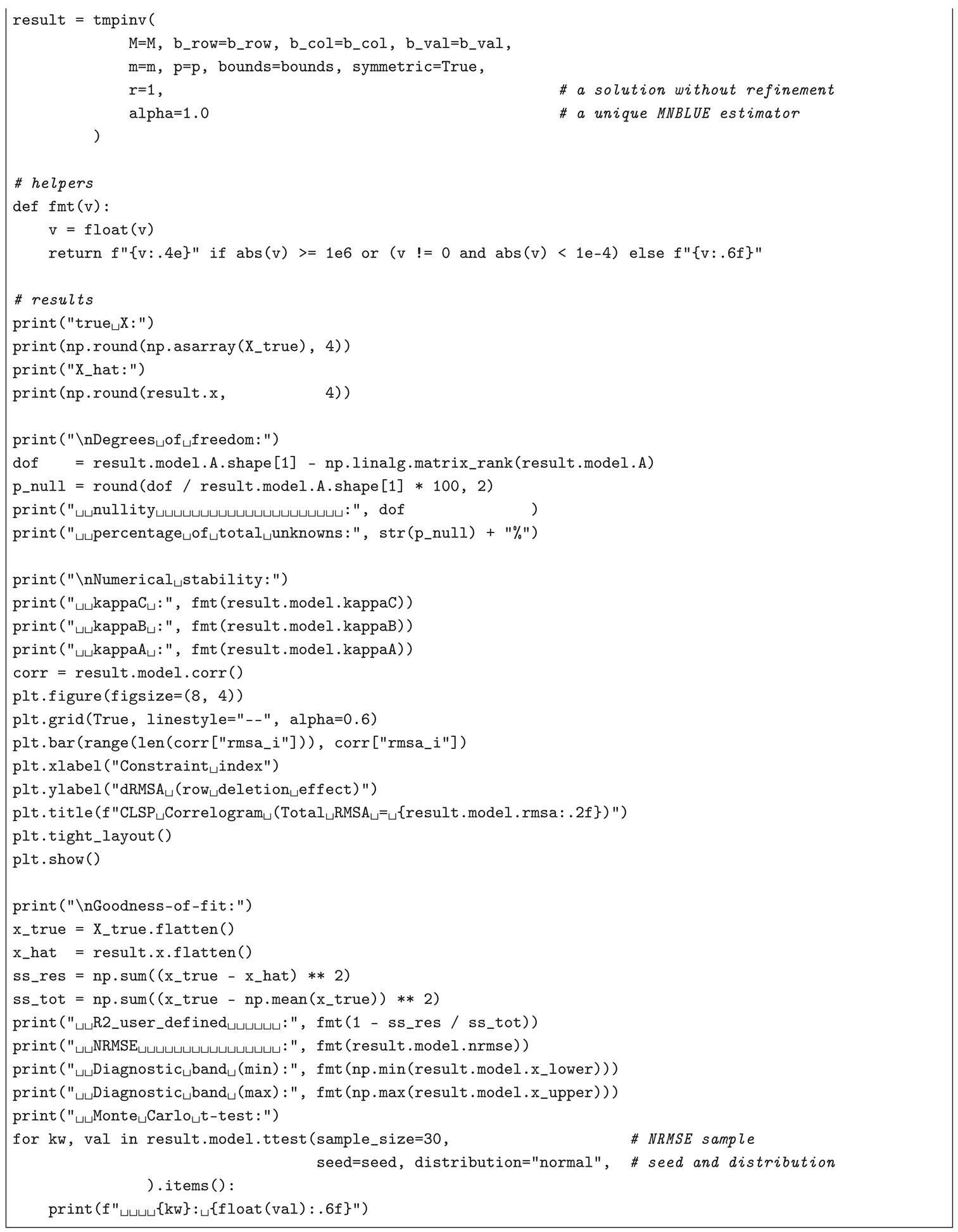

|

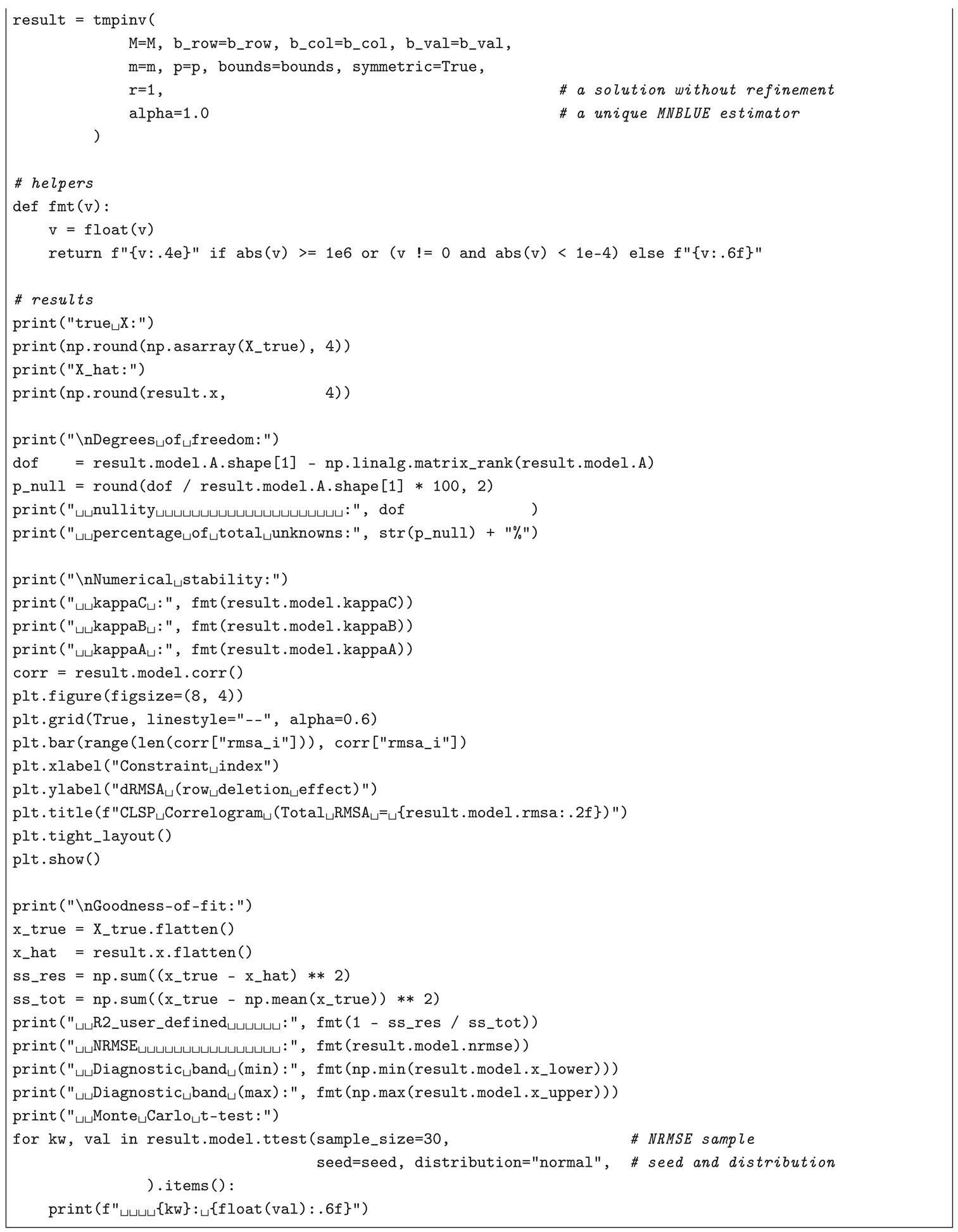

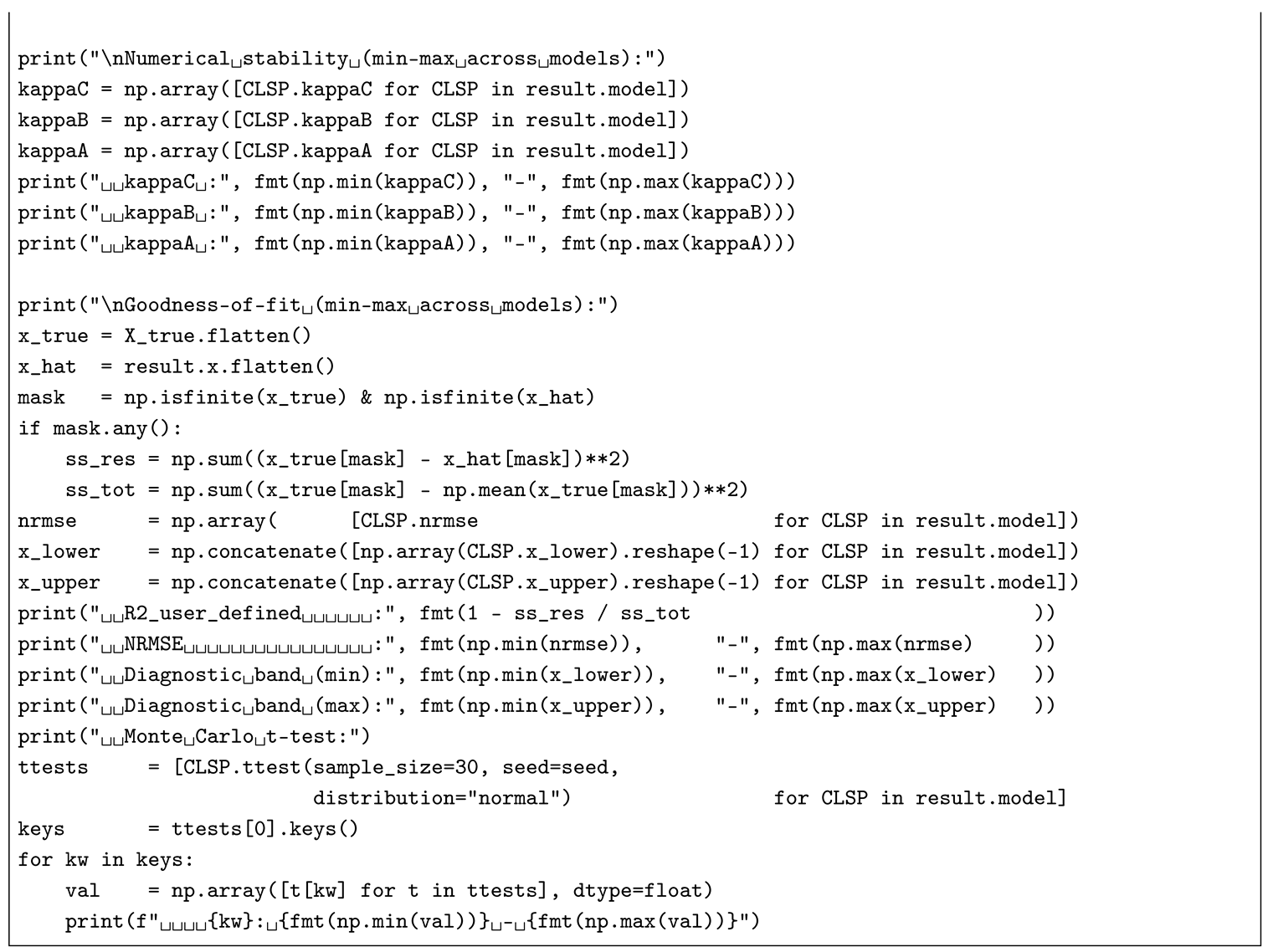

Listing 2. Simulated numerical example for a (non-negative) trade-matrix-based AP (TM) problem. |

|

|

In case (b) (see Listing for code), the corresponding number of model (target) variables in each of the reduced design submatrices , , is — where and , one row and one column being reserved for and , which enter as and the vector of slack variables , so that (i.e., the slack matrix compensates for the unaccounted row and column sums in the reduced models as opposed to the full one, such as case (a)) — with a nullity (per reduced model), corresponding to 25.00%–72.68% of the total unknowns (per reduced model) — to compare, a full model, under the same inputs and no computational constraints (i.e., ), would have a nullity , corresponding to 73.00% of the total unknowns. In the examined example, — based on , , and a randomly selected 20% of entries of the true matrix , — the reduced-model block solution’s goodness of fit could not be efficiently measured by a user-defined (i.e., the block matrix constructed from reduced-model estimates led to , but to an error proportionate to the one in case (a), (per reduced model)) — in contrast, a full model would achieve , but at a cost of a greater error, — with lying within strongly varying condition-weighted diagnostic intervals , where (per reduced model) and (per reduced model), and varying results of Monte Carlo-based t-tests for the mean of the (on a sample of 30 values obtained by substituting with ), where p-values range –1.000000 (left-sided), 0.000000–1.000000 (two-sided), and –1.000000 (right-sided) (per reduced model) — alternatively, a full model would lead to wider condition-weighted diagnostic intervals (i.e., reflecting the ill-conditioning of the strongly rectangular , ) and only the left-sided Monte Carlo-based t-test for the mean of the NRMSE (on a sample of 30 NRMSE values obtained by substituting with ) suggesting consistency with expectations (i.e., with the ). In terms of numerical stability, (per reduced model), which indicates well-conditioning of all the reduced models — conversely, in a full model, (therefore, a full model ensures an overall better fit but a lower fit quality, i.e., a trade-off).

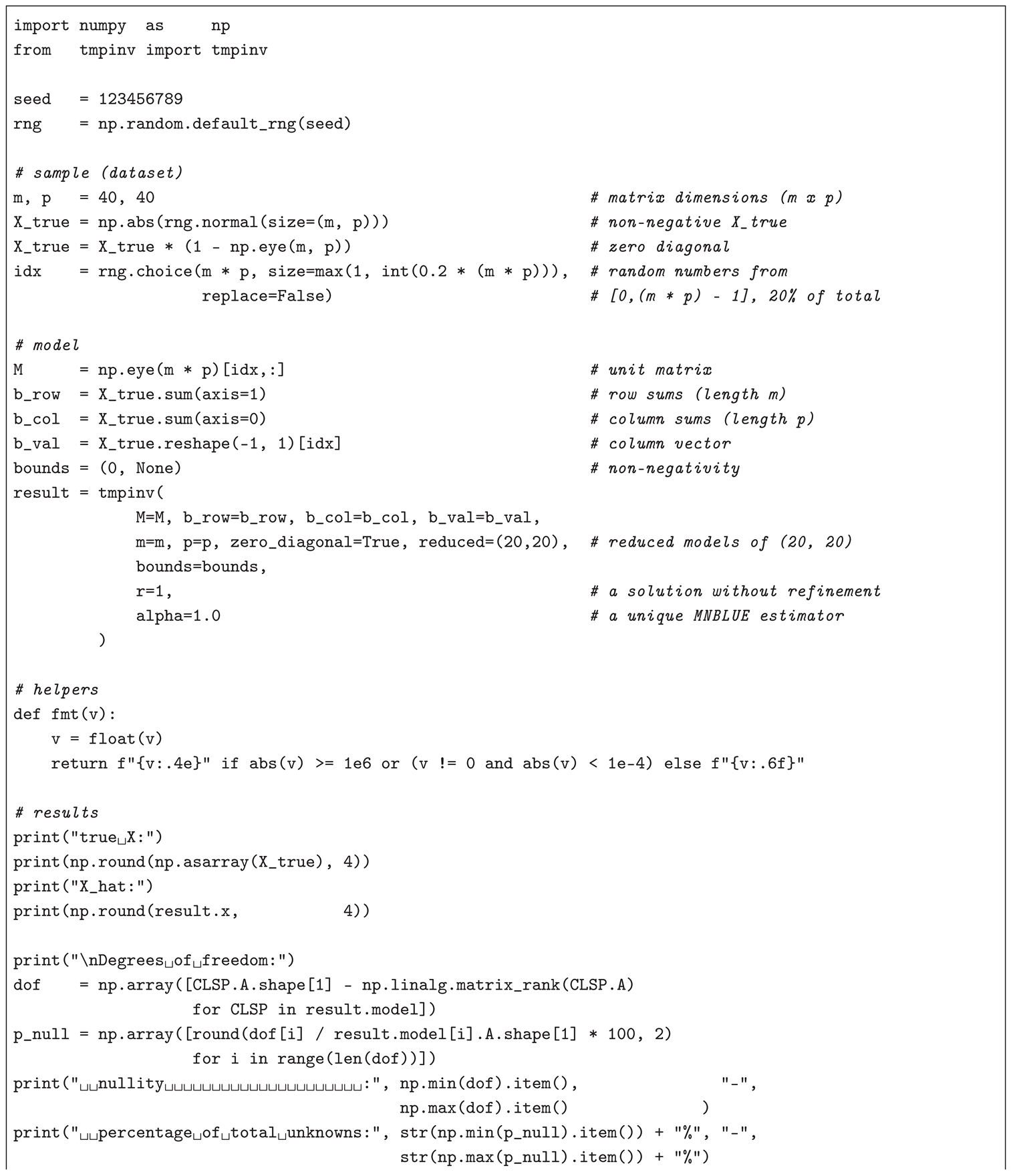

As the

CMLS (RP) numerical example, this text addresses a problem similar to the one solved in Bolotov [

15], Bolotov [

96]: a coefficient vector

from a (time-series) linear regression model in its classical (statistical) notation

with

denoting

n-th order differences (i.e., the discrete analogue of

) — where

is the dependent variable,

is the vector of regressors with a constant,

is the model’s error (residual),

c is a constant, and

is the set of stationary points — is estimated on a simulated sample (dataset) with the help of CLSP assuming

and

,

. The Python 3 code, based on

numpy and

pyclsp modules, installable by executing

pip install numpy pyclsp==1.3.0, for

,

,

,

, where

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

, with a non-iterated (

), unique (

), and MNBLUE (

) two-step CLSP solution (consistent with the ones from cases (a) and (b) for APs (TMs)), is implemented in Listing (e.g., for a Jupyter Notebook).

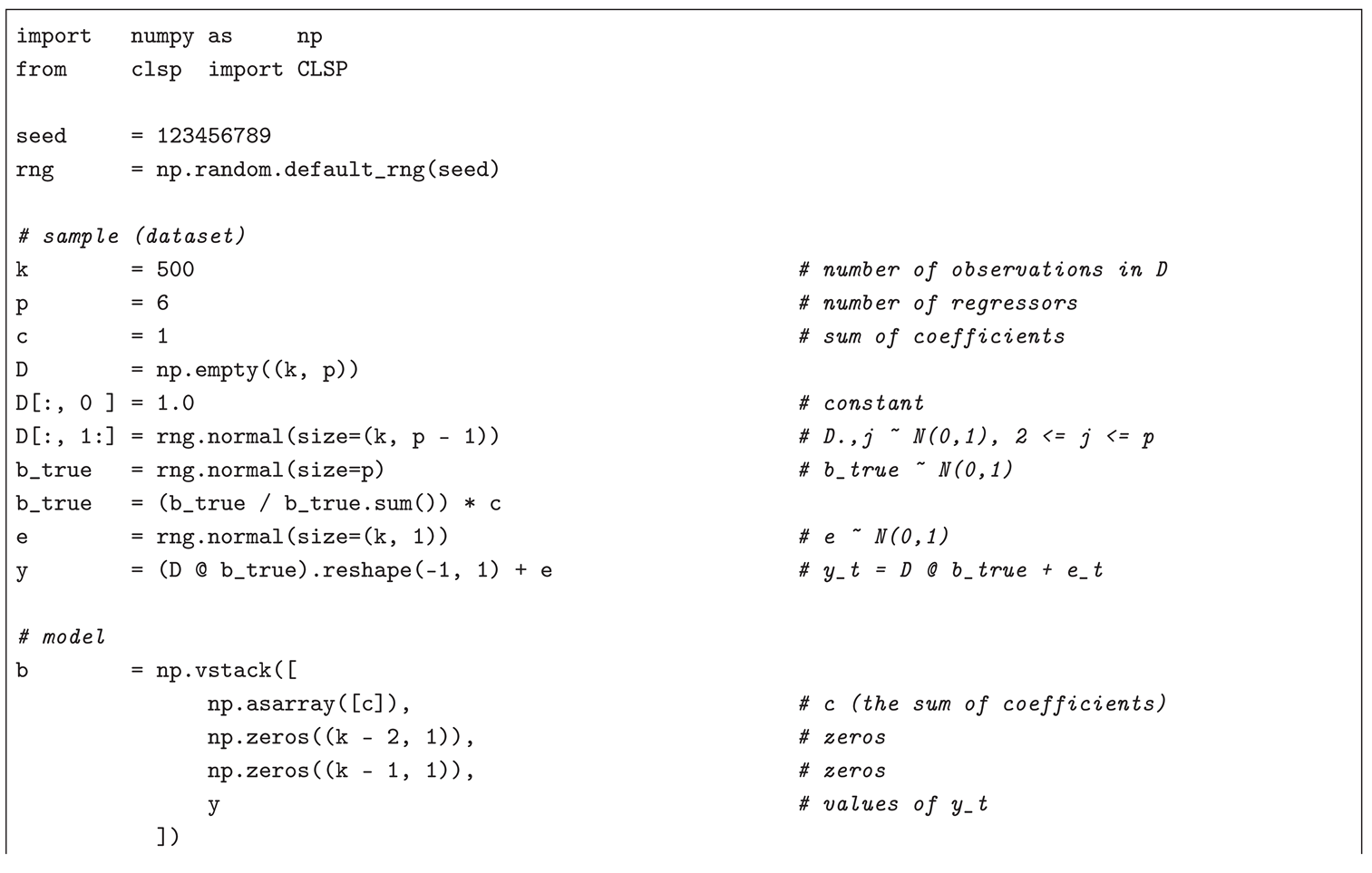

|

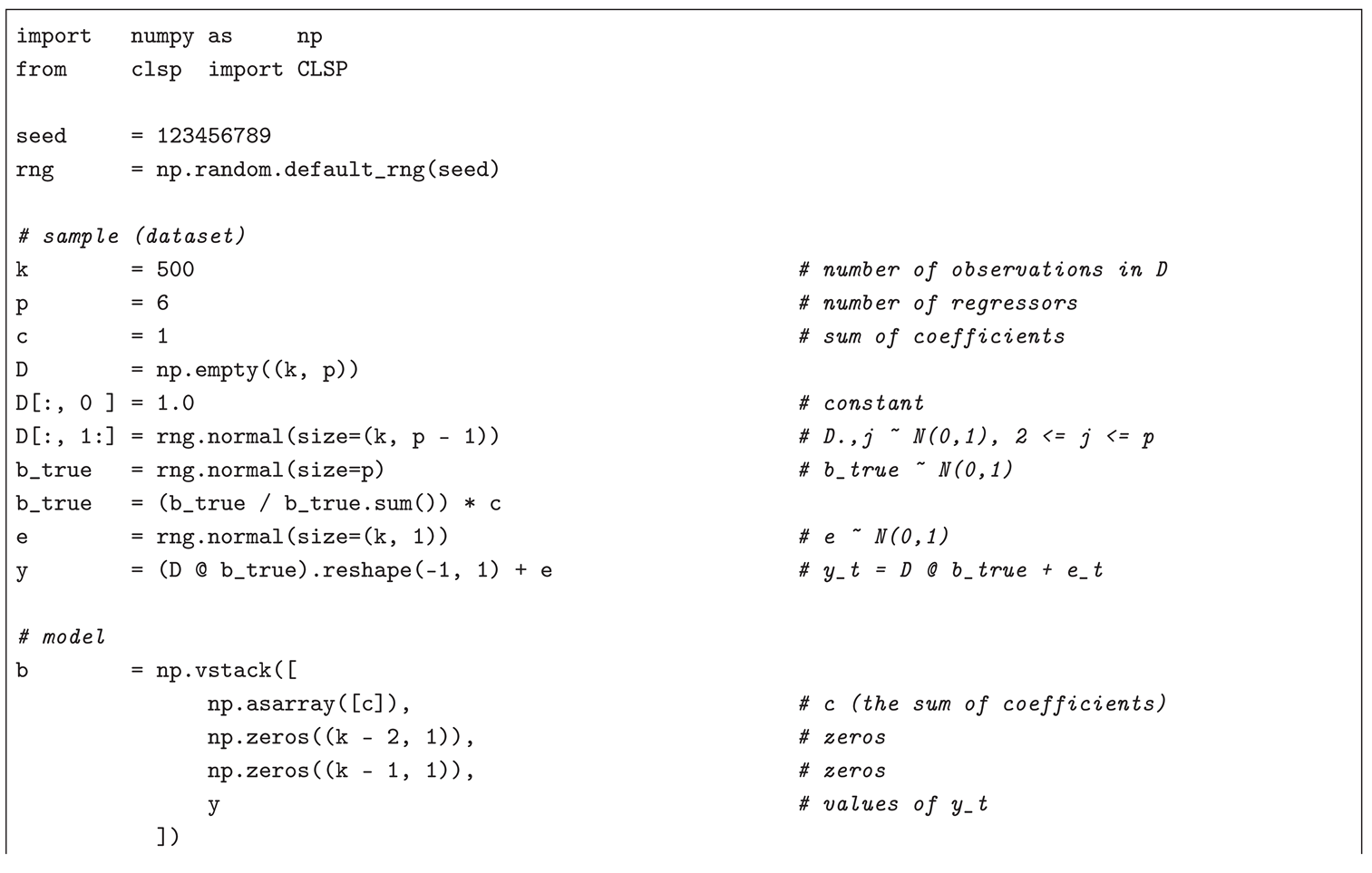

Listing 3. Simulated numerical example for a (time-series) stationary-points-based CMLS (RP) problem. |

|

|

Compared to the true values , the CMLS (RP) estimate is with a modest (i.e., a greater error, ), moderate condition-weighted diagnostic intervals , and only the right-sided Monte Carlo-based t-test for the mean of the (on a sample of 30 values obtained by substituting with ) — in the example under scrutiny, is preferable to NRMSE due to — suggesting consistency with expectations (i.e., with the ). Similarly, in terms of numerical stability, , indicating that the constraint block is ill-conditioned, most likely, because of the imposed data- (rather than theory-) based definition of stationary points, which rendered Step 2 infeasible () (limiting the fit quality).

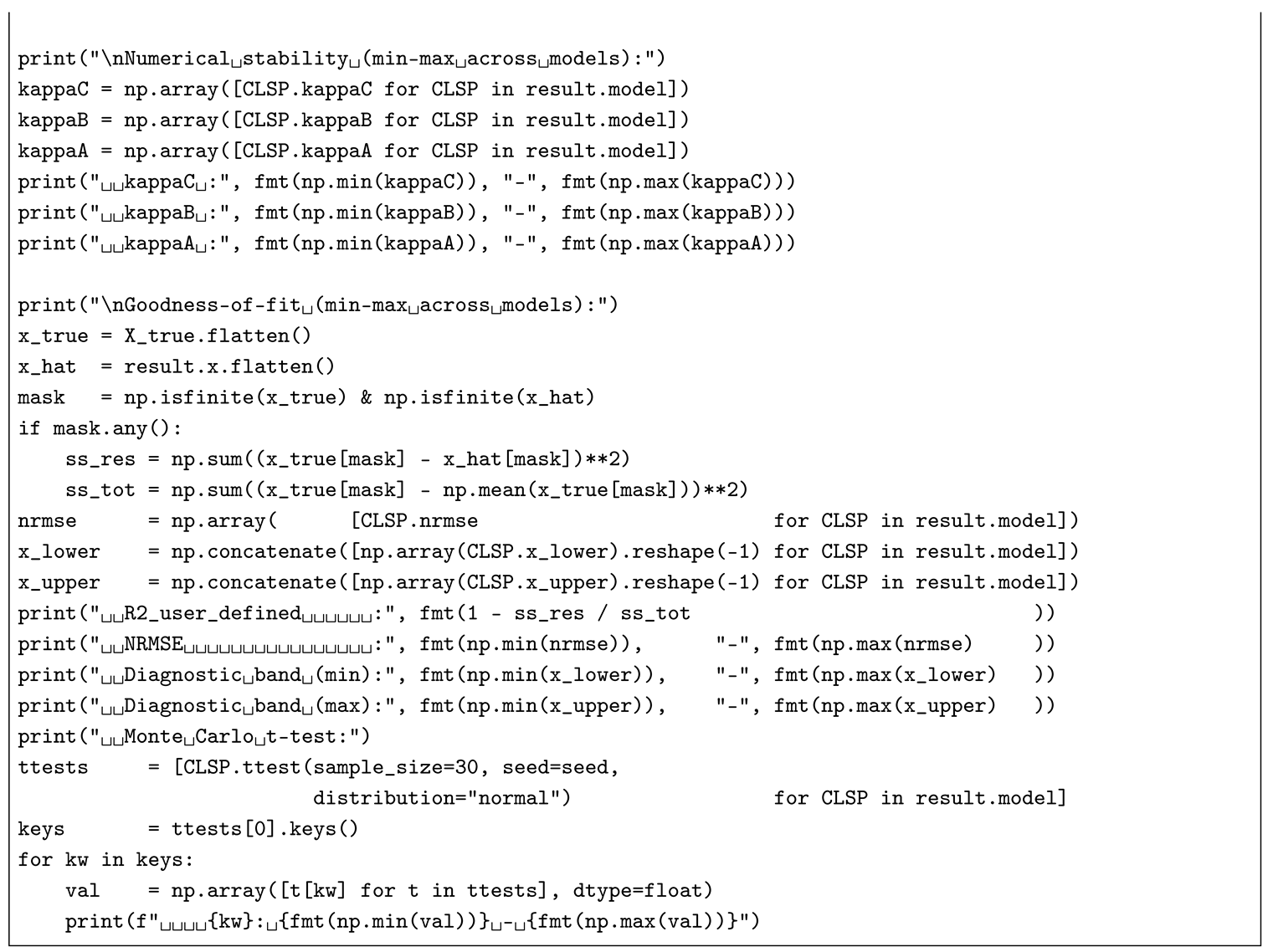

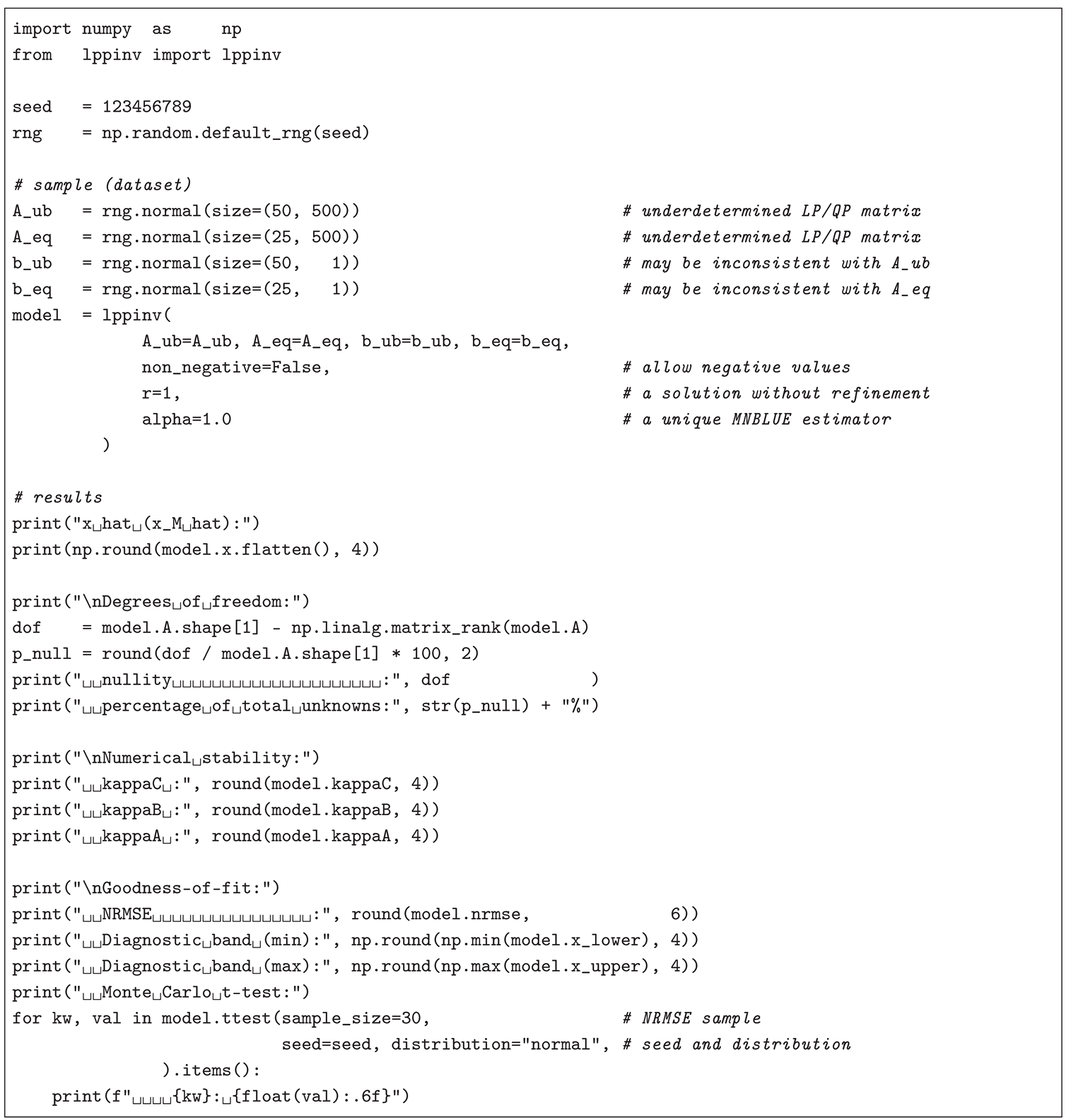

Finally, in the case of a

LPRLS/QPRLS numerical example, this text simulates potentially ill-posed LP (QP) problems, similar to the ones addressed in Whiteside et al. [

93] and Blair [

76], Blair [

94]: a solution

in its classical LP (QP) notation

(

),

— where

is a symmetric positive definite matrix,

,

, and

— is estimated from two randomly generated (coefficient) matrices

,

, and

,

, and two (right-hand-side) vectors

,

, and

,

, via CLSP assuming

,

, and

, where

and

are permutation matrices, while omitting

and

. The Python 3 code, based on

numpy and

pylppinv modules, installable by executing

pip install numpy pylppinv==1.3.0, for

,

, and

, with a non-iterated (

), unique (

), and MNBLUE (

) (two-step) CLSP solution (analogously consistent with the ones from cases (a) and (b) for APs (TMs) and the one from CMLS (RPs)), is implemented in Listing (e.g., for a Jupyter Notebook).

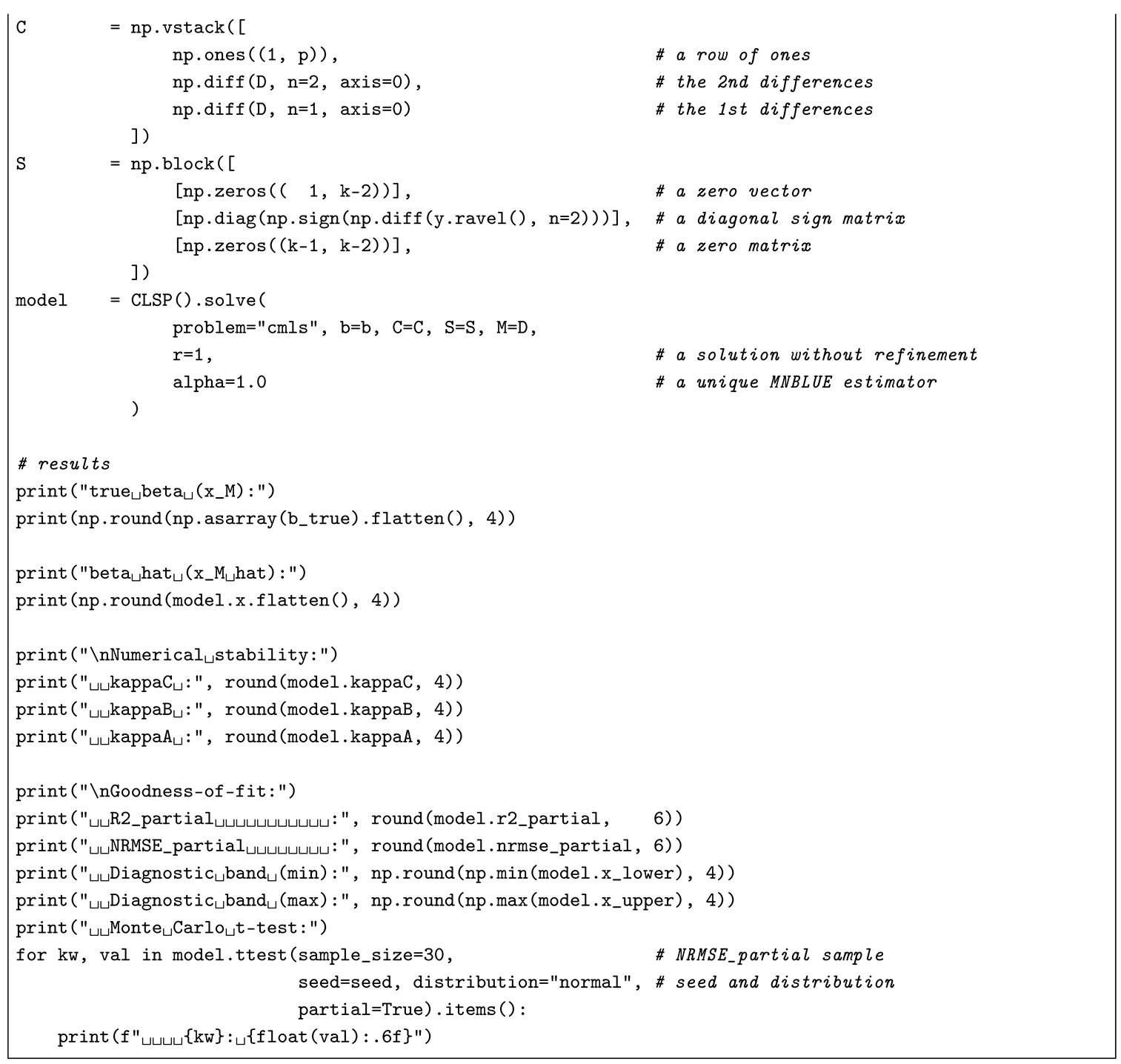

|

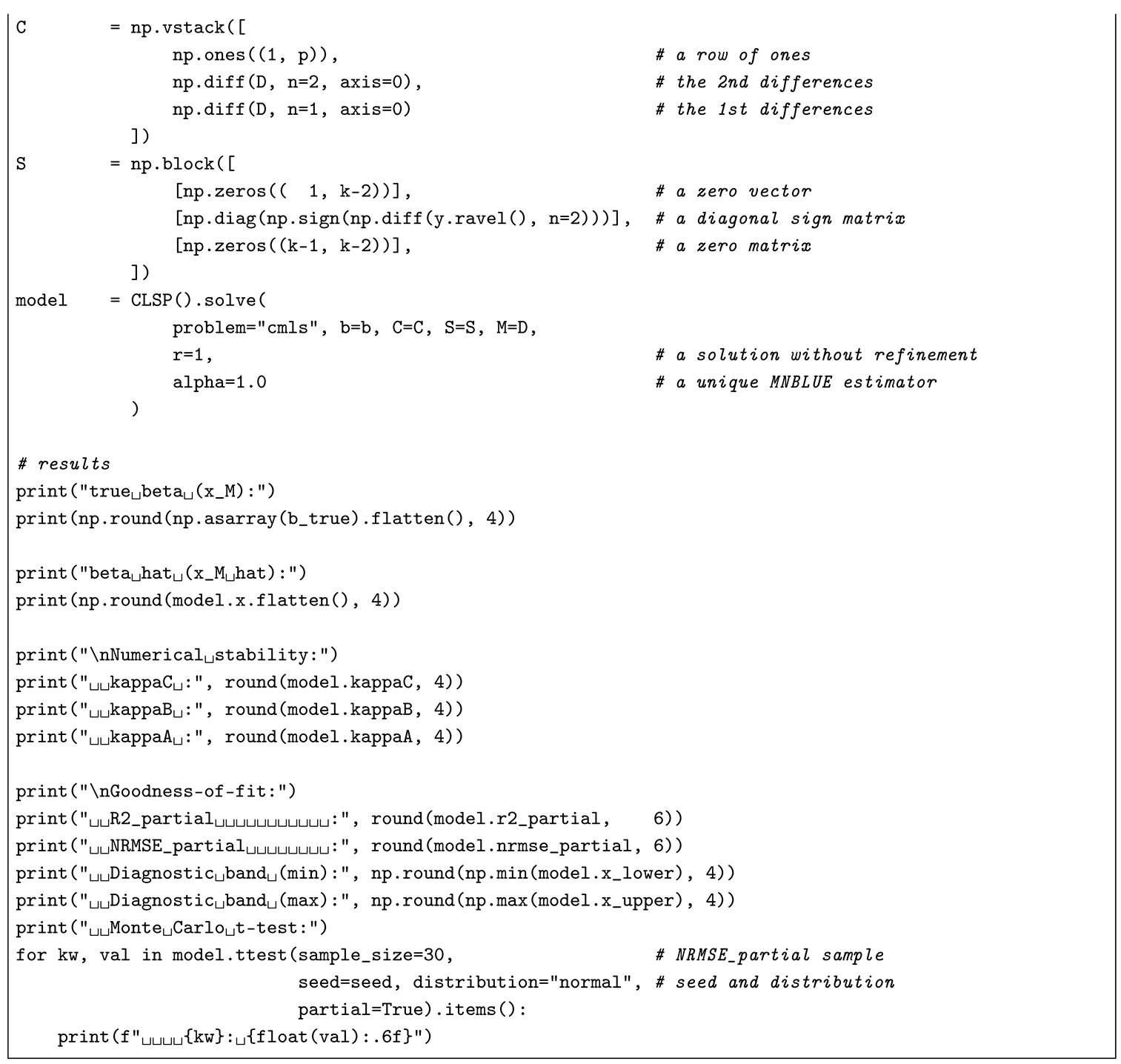

Listing 4. Simulated numerical example for a underdetermined and potentially infeasible LP (QP) problem. |

|

The nullity (i.e., underdeterminedness) of the CLSP design matrix, , is , corresponding to 86.36% of the total unknowns, accompanied by a greater (relatively high) error, , moderate condition-weighted diagnostic intervals , and only the right-sided Monte Carlo-based t-test for the mean of the NRMSE (on a sample of 30 NRMSE values obtained by substituting with ) suggesting consistency with expectations (i.e., with the ). Similarly, in terms of numerical stability, , indicating that the constraint block is well-conditioned despite a strongly rectangular . Hence, CLSP can be efficiently applied to AP (TM), CMLS (RP), and LPRLS/QPRLS special cases using Python 3, and the reader may wish to experiment with the code in Listings – by relaxing its uniqueness (setting ) or the MNBLUE characteristic (setting ).