1. Introduction

The question of what constitutes the fundamental structure of reality has long preoccupied philosophy, physics, and metaphysics. From Plato’s theory of Forms [

15] to contemporary digital physics [

7,

12,

19,

22,

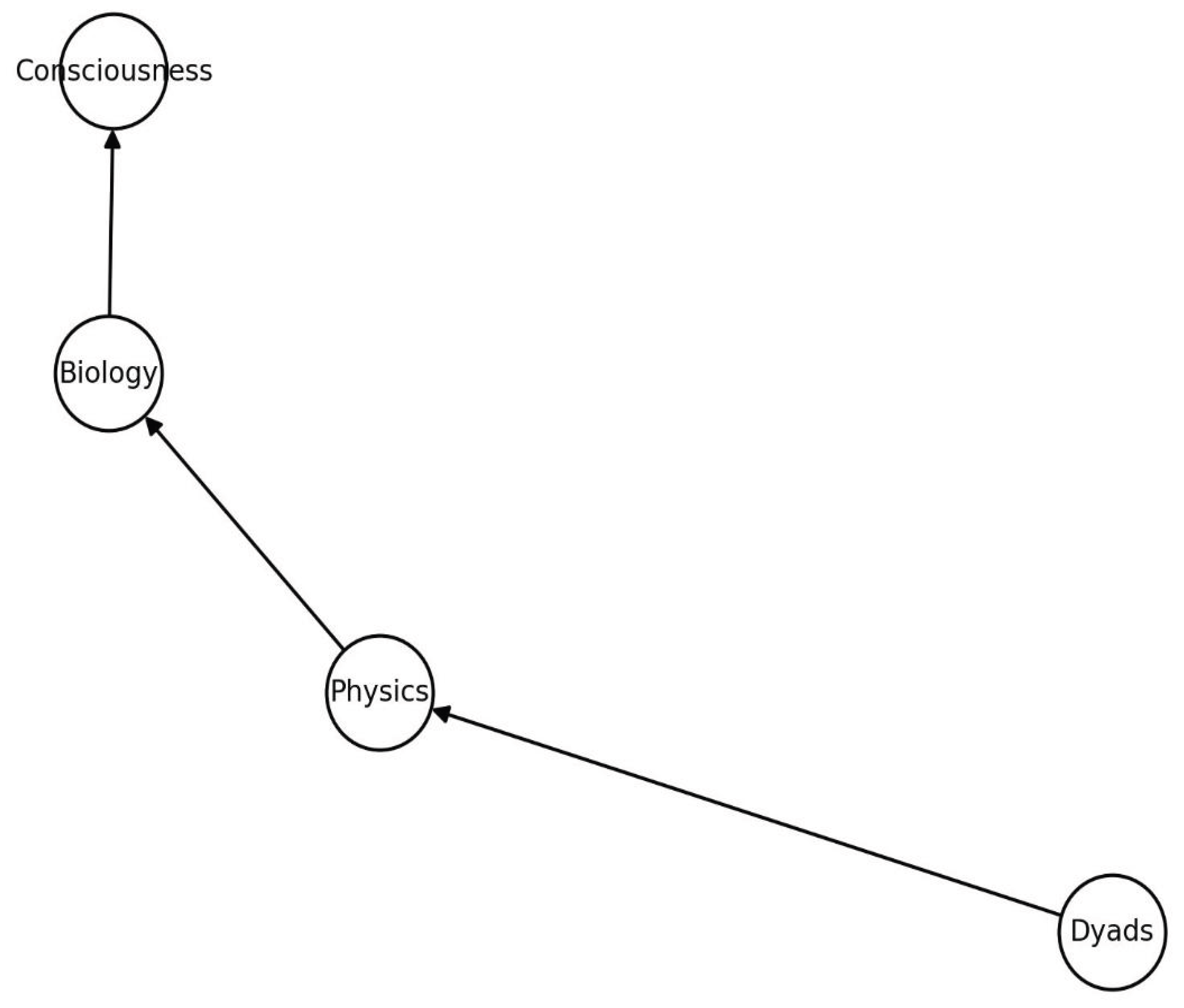

24], thinkers have sought to identify the most basic units of existence and the principles by which they interact. One of the persistent tensions in this endeavour is between relational and substantialist ontologies: whether reality is composed of discrete entities with intrinsic properties or of relations that define entities only through their interactions. Dyadic-Code Eternalism (DCE), also termed Dyadic Logos Theory, proposes a novel resolution to this debate by grounding existence in dyads—elementary pairs of informational relations. Unlike atomist or monadic models, DCE treats the dyad as irreducible: it is not a combination of pre-existing units, but the foundational form of existence itself. The dynamics of these dyads, governed by informational laws referred to as the Dyadic Logos, generate higher-order complexity, including the experience of time, the emergence of consciousness, and the evolution of cosmological structures. In situating itself within the broader metaphysical discourse, DCE draws upon three key traditions. First, it extends the [

13,

17,

18] eternalist conception of time, which posits that all temporal moments exist equally in a four-dimensional block universe. Second, it integrates insights from digital physics, which conceives of the universe as computational or informational in nature. Third, it engages with complexity theory and emergence, arguing that macro-level structures are irreducible to micro-level units but instead arise from patterns of relational interaction. The ambition of this paper is to provide a systematic exposition of DCE in both philosophical and theoretical terms. It proceeds by first situating the theory in its intellectual context, drawing on historical debates in metaphysics and philosophy of time. It then develops the core theoretical framework of DCE, introducing dyads as fundamental entities and articulating the principles of their interaction. From there, the paper explores the implications of this ontology for time, causality, and consciousness, as well as its resonance with scientific approaches in quantum theory and information science. The central hypothesis advanced is that reality is constituted not by things but by coded relations between pairs of informational units, and that the apparent flow of time and structure of reality are emergent consequences of the underlying dyadic code.

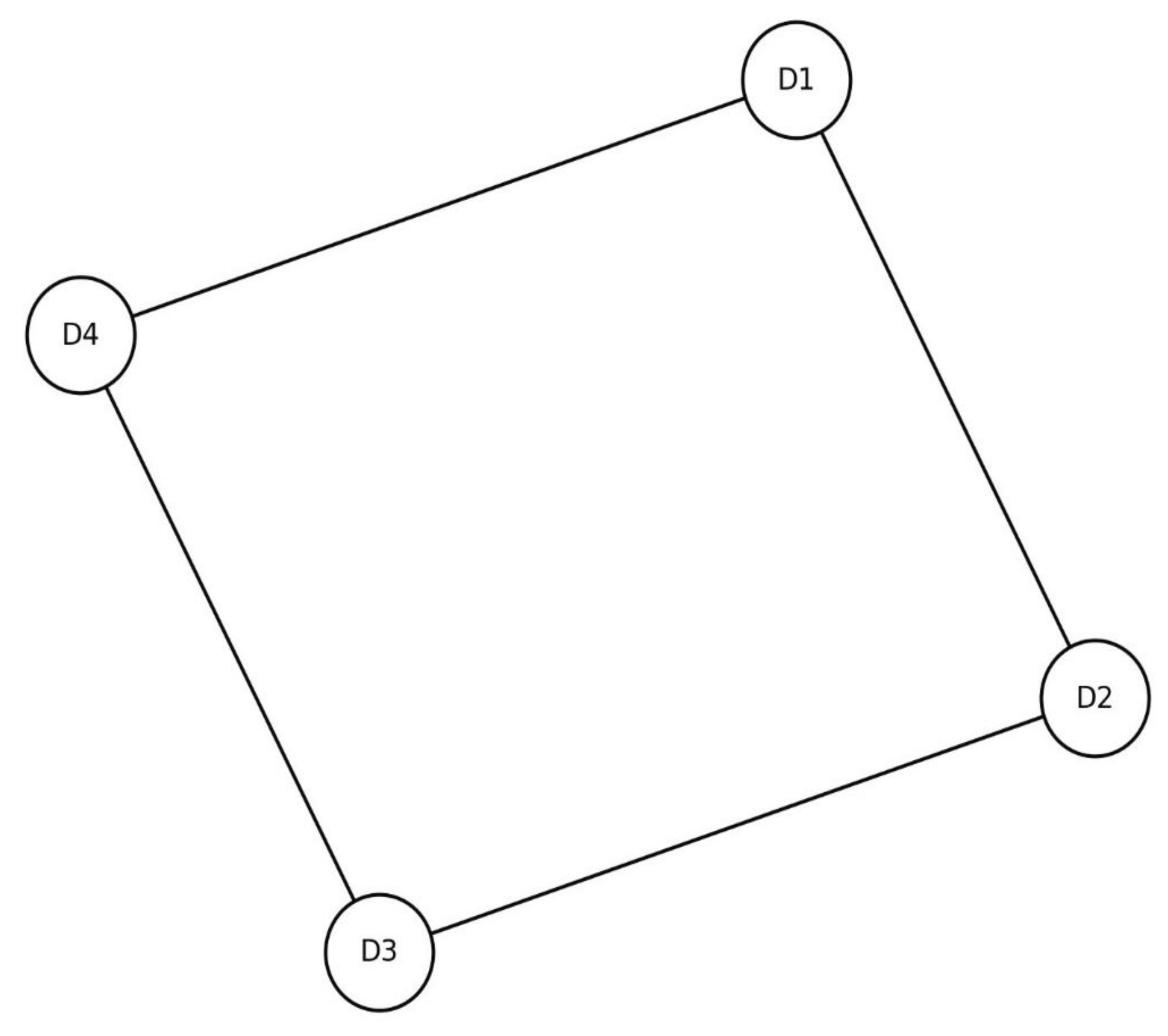

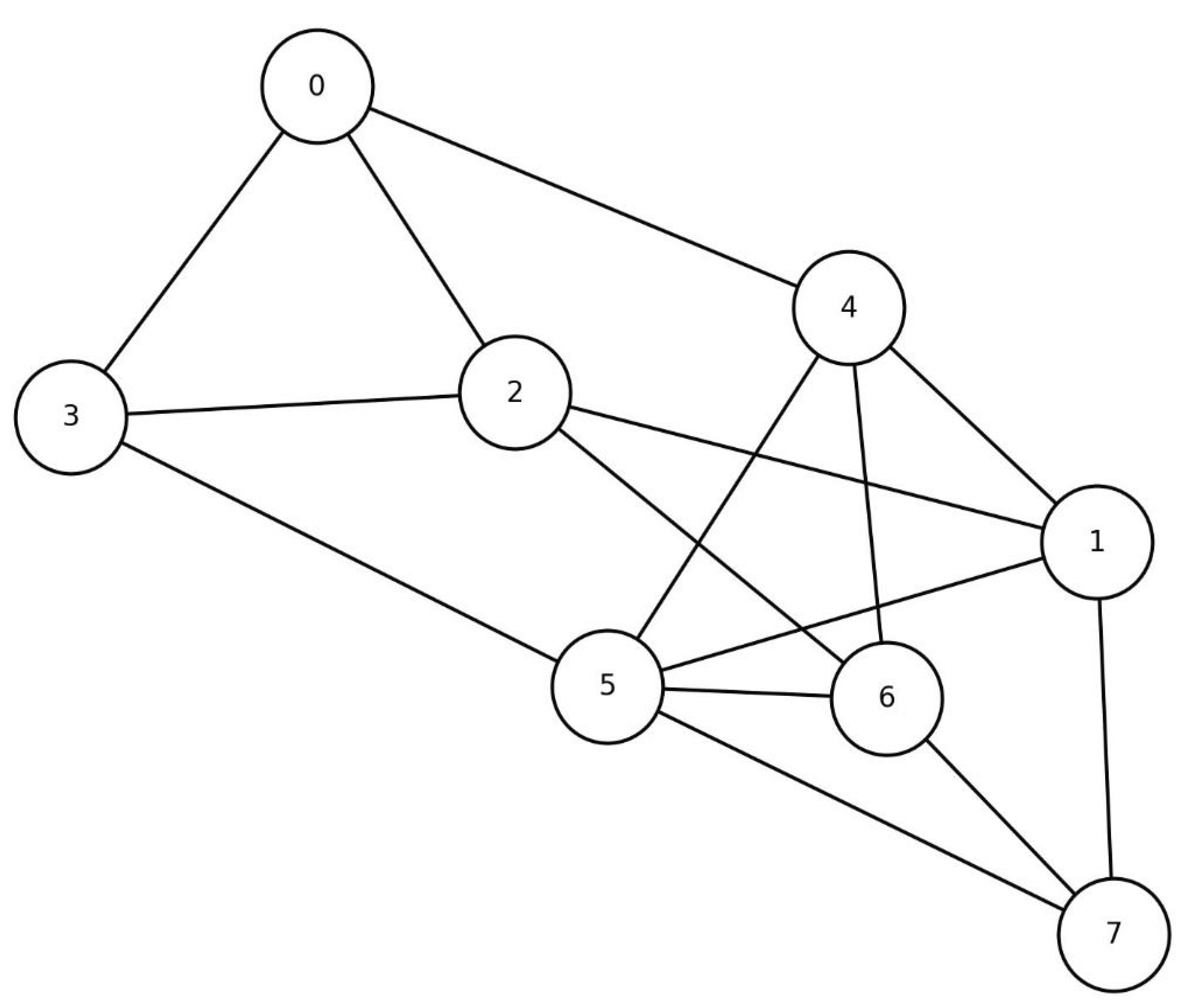

Figure 1.

Dyadic Interaction Network.

Figure 1.

Dyadic Interaction Network.

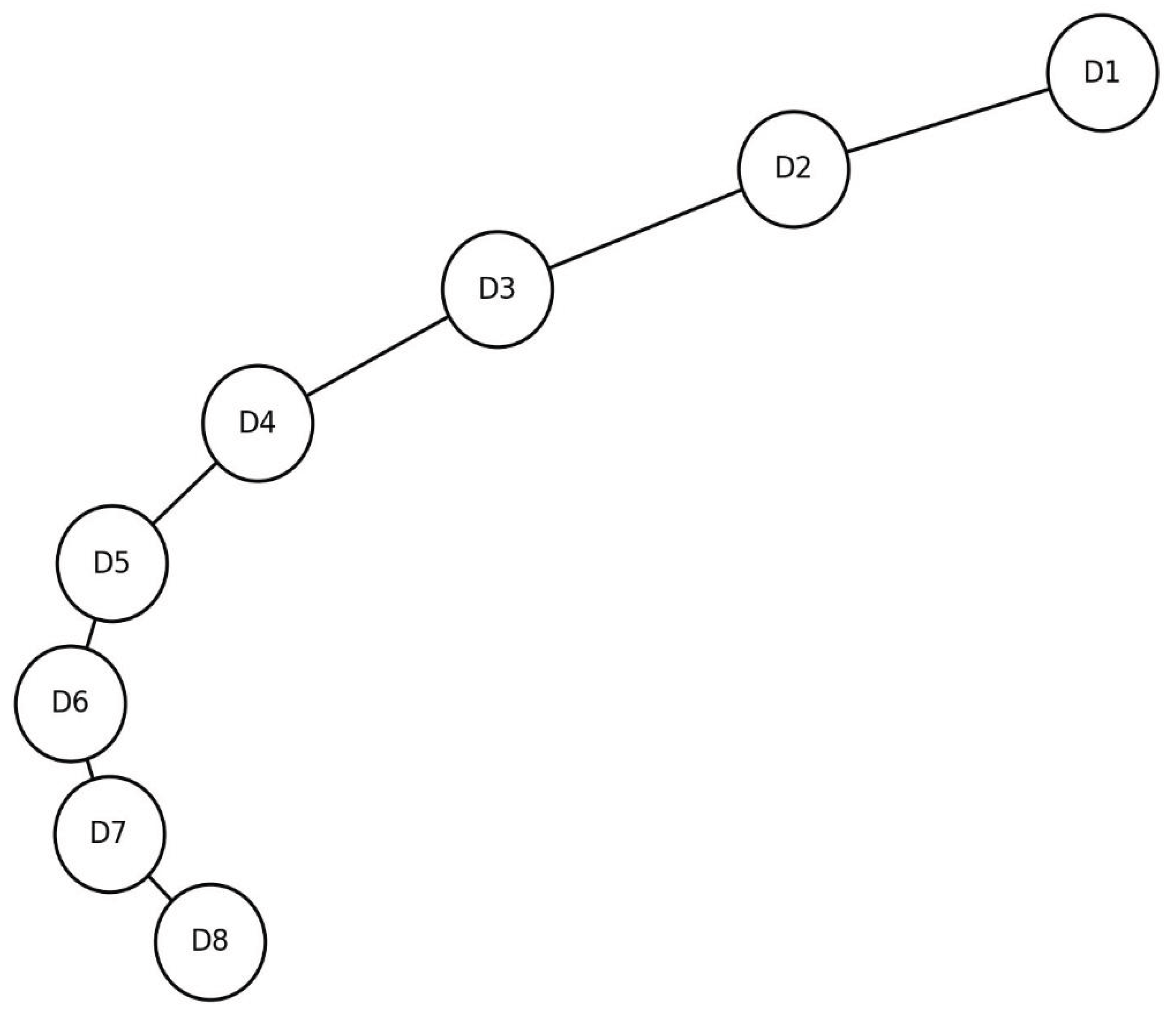

2. Historical and Philosophical Background

Any new metaphysical framework benefits from being situated within the wider history of philosophy and science. Dyadic-Code Eternalism (DCE) emerges from a lineage of debates concerning the structure of reality, the ontology of time, and the role of information in physical theory. This section reviews these traditions, clarifying both the continuities and departures that define DCE. Classical metaphysics often centred on substance [

1], yet relational alternatives were present from the outset. Heraclitus emphasised flux and opposition [

8]; Plato’s Timaeus depicts a cosmos structured by mathematical ratios [

15]; Leibniz defended a relational view of space and time [

11]; and Hegel articulated dialectical pairs [

9]. DCE inherits the conviction that relationality is primary and advances the stronger thesis that the dyad is the atomic form of relation. In philosophy of time, eternalism [

13,

17,

18] maintains that all points in time—past, present, and future—are equally real. While this view accords with relativity’s denial of an absolute ``now,’’ it has struggled to account for temporal phenomenology. DCE modifies eternalism by treating temporal structure as emergent from ordered dyadic interactions. The block is not a container of events but a persistent informational network. In digital physics [

7,

12,

19,

22,

24], reality is informational. DCE converges with this tradition yet shifts the primitive from bits to dyads: code is intrinsically relational. Finally, in complexity theory [

10,

14,

16], macro-order arises from local rules. DCE generalises this insight by grounding all emergence in dyadic networks. By synthesising these strands, DCE proposes that dyads are primitive, that time is emergent and eternalist, and that consciousness and law are expressions of dyadic organisation..

Figure 2.

Historical Influences on DCE (schematic layering/ordering over time).

Figure 2.

Historical Influences on DCE (schematic layering/ordering over time).

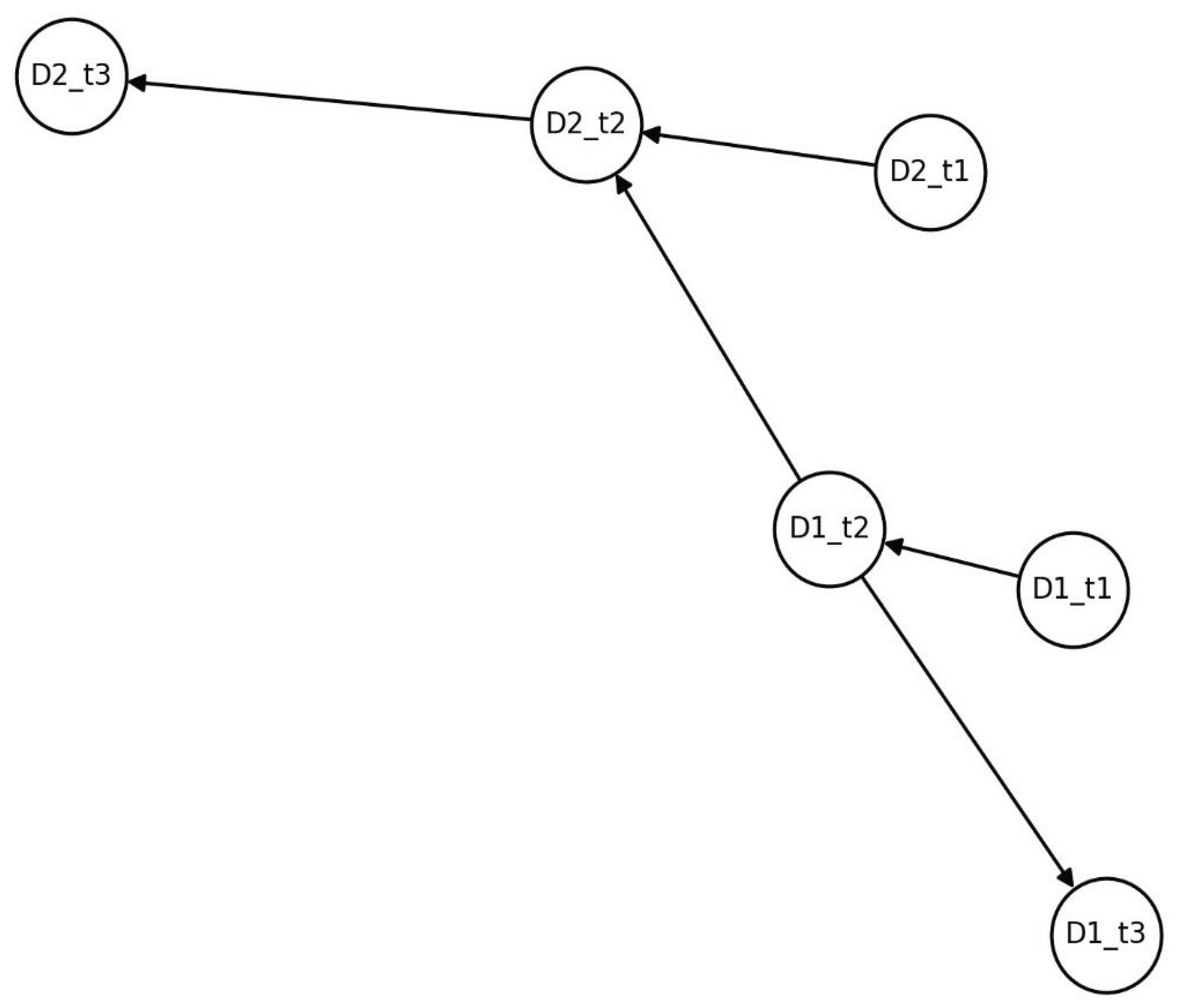

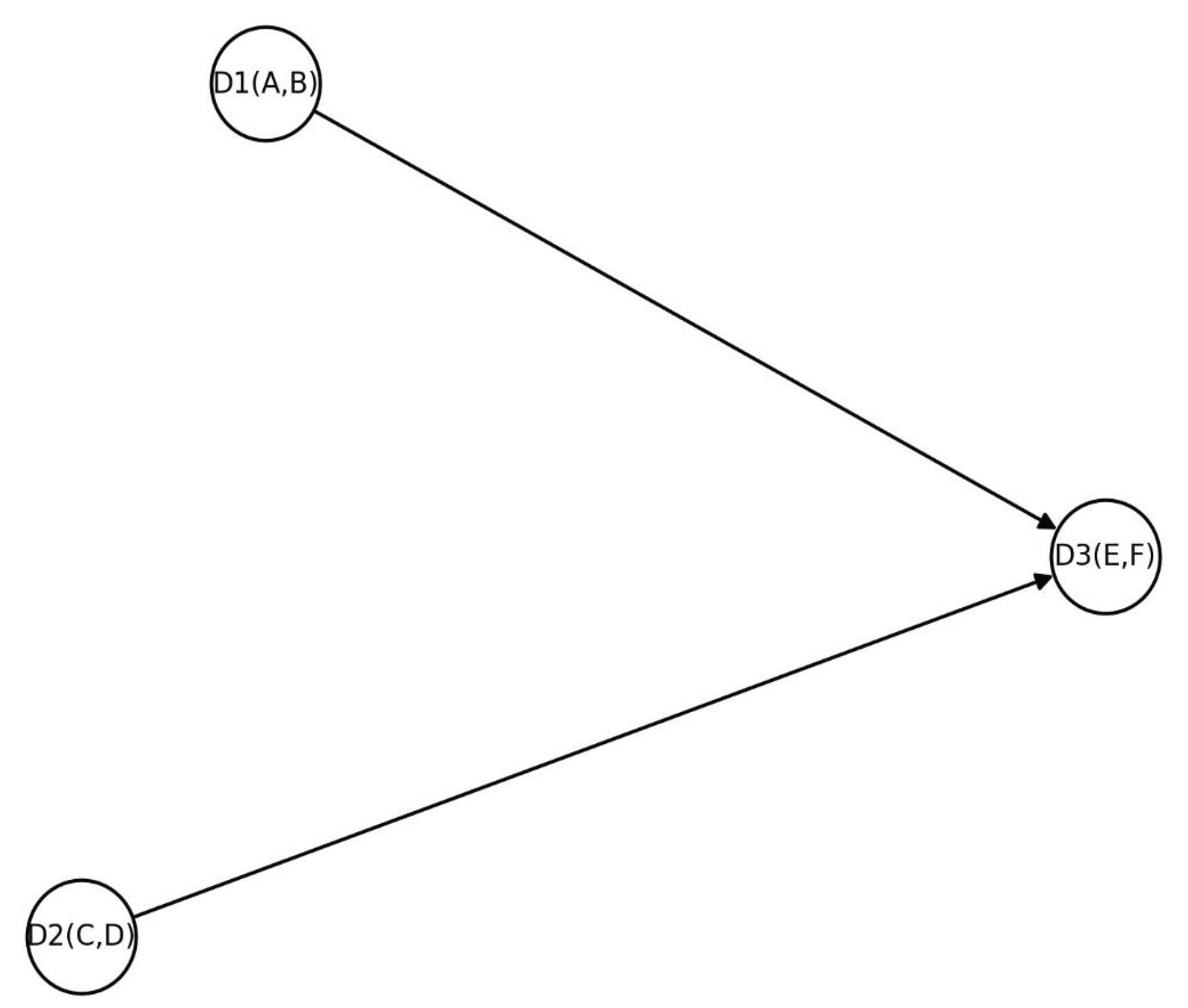

3. The Dyadic-Code Eternalism Model

Having situated DCE within its historical context, we articulate its formal core. DCE advances the claim that the dyad—an ordered pair of informational states—is the fundamental unit of reality. The structure of the universe is conceived as an interconnected network of dyads whose interactions, governed by the principles of Dyadic Logos, give rise to emergent order. A dyad is a minimal unit of informational relation: an ordered pair (A,B). Unlike a bit, which carries a discrete value (0 or 1), a dyad encodes both informational content and relational context. Dyads interact via a function F such that D_k = F(D_i, D_j), where F can be deterministic, probabilistic, or conditional. The interaction generates new relational structure rather than merely exchanging information. Reality as a whole may be modelled as a dyadic network in which nodes represent dyads and edges represent interaction pathways. The network evolves through successive applications of interaction rules. Time, on this account, is emergent from the ordered relations of dyadic interactions; the block universe is a persistent dyadic network whose layers correspond to orders of relation rather than a separate temporal dimension.

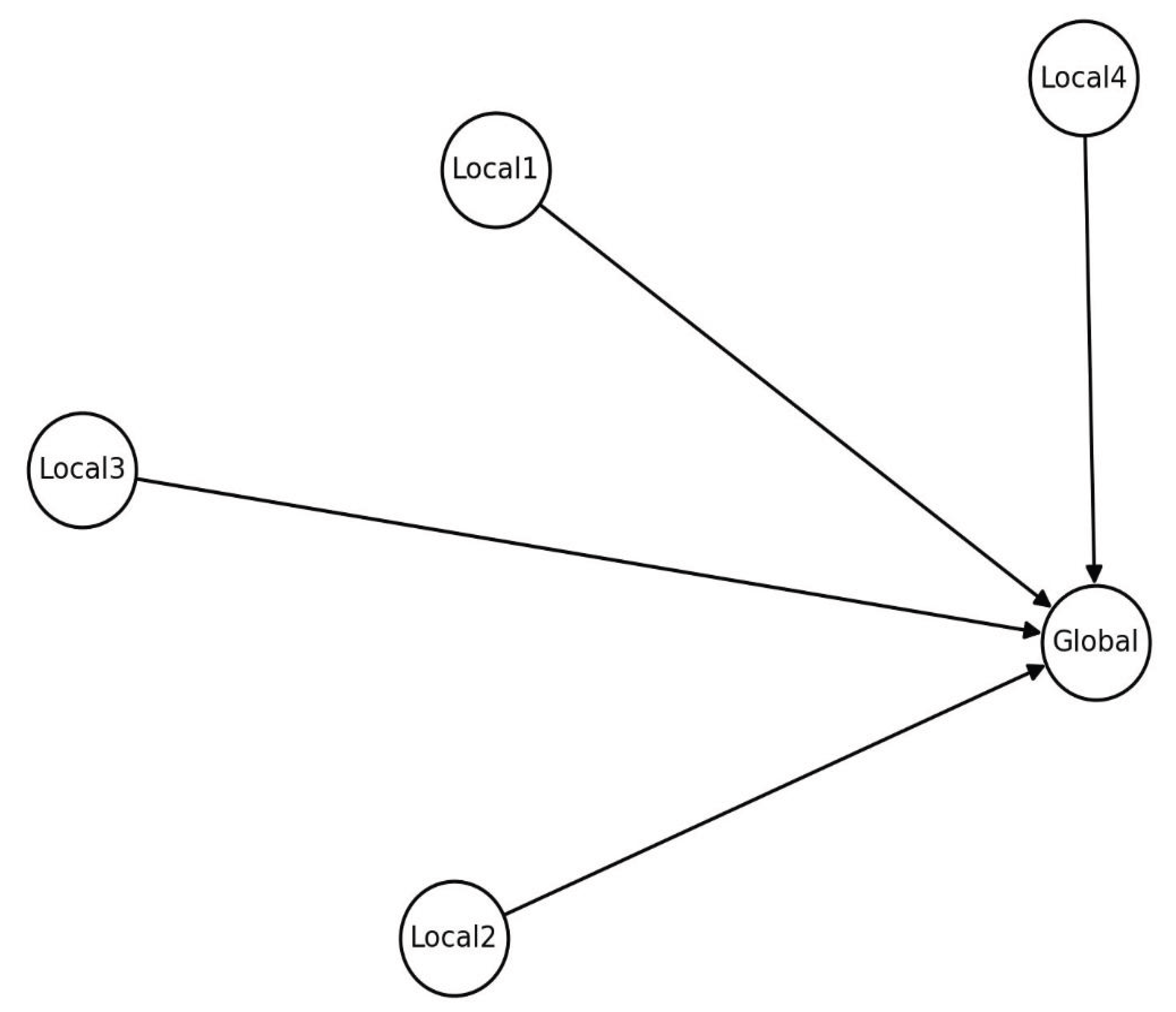

Figure 3.

Formal Dyadic Interaction.

Figure 3.

Formal Dyadic Interaction.

4. Dyadic Logos: Principles and Laws

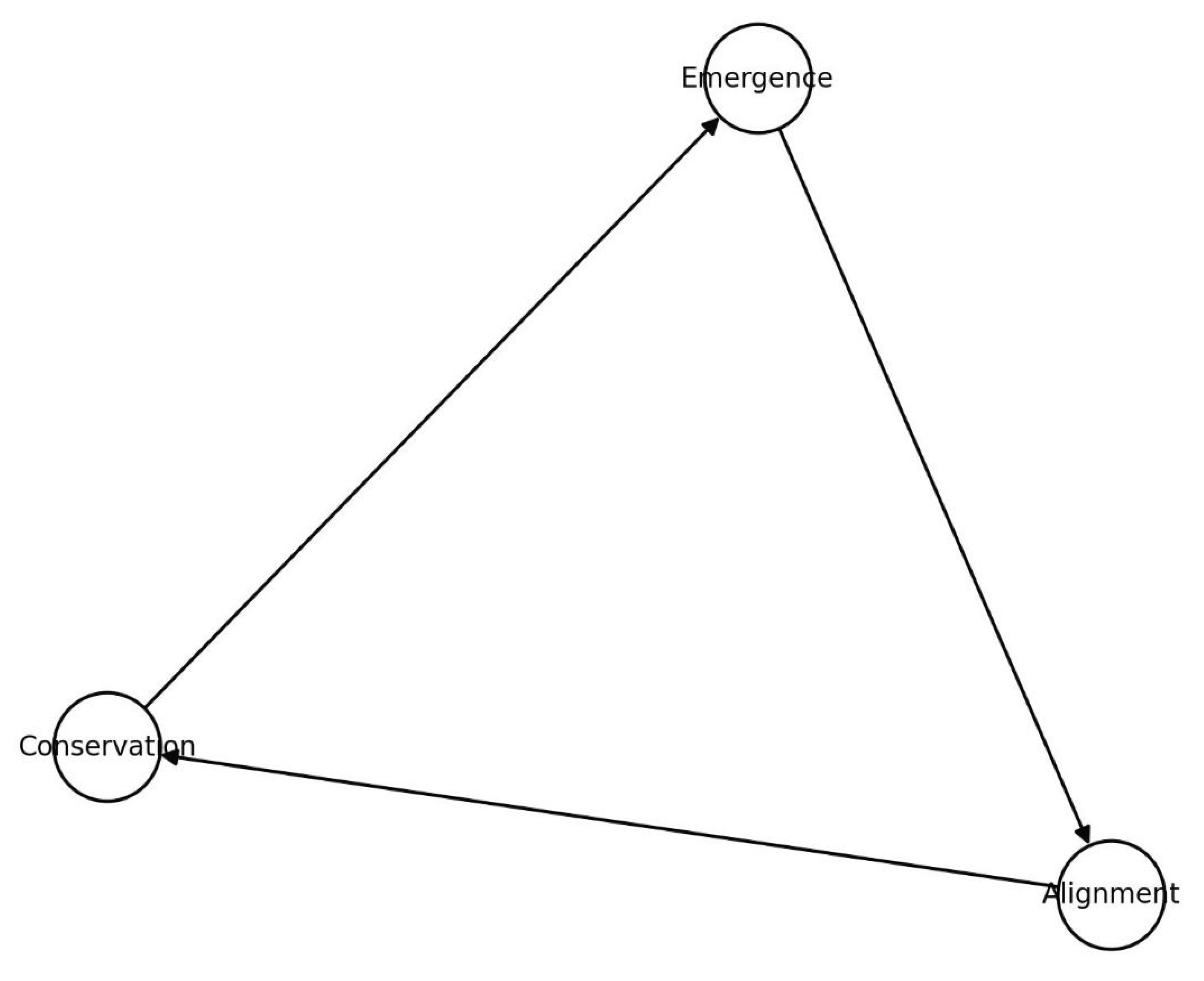

The Dyadic Logos names the intrinsic logic of dyadic interaction. It is not an external lawgiver but the structural grammar of reality: the patterns that govern how dyads connect, transform, and persist. Three foundational principles are posited: (1) Conservation of Dyadic Information—interactions preserve informational content, though it may be redistributed; (2) Relational Emergence—higher-order properties arise from network organisation, not from individual units; (3) Adaptive Alignment—dyadic systems tend toward patterned stability or equilibrium. Together these principles ensure persistence, generate complexity, and orient systems toward coherence. The Logos also bears on consciousness: conscious states arise when dyadic networks attain high levels of informational integration, with context-sensitive relations enabling meaning and global patterning.

Figure 4.

Laws of Dyadic Logos.

Figure 4.

Laws of Dyadic Logos.

5. Implications and Applications

DCE’s implications span metaphysics, science, and applied domains. Philosophically, DCE reframes eternalism [

13,

17,

18]: temporal passage is an emergent feature of dyadic ordering, while the persistence of the network grounds the equal reality of temporal relations. Causality appears as a structural property of dyadic transformations rather than a primitive arrow. Freedom is compatibilist: lawful yet emergent from irreducible complexity. In physics and cosmology, symmetry and conservation can be modelled as manifestations of informational conservation; quantum entanglement as persistent dyadic linkage regardless of spatial separation [

12,

22]; and spacetime as emergent relational layering. In complexity and biology, dyadic models apply to organisational patterns across scales [

10,

14,

16]. In consciousness science, integration of dyadic networks correlates with holistic experiential states [

20,

21]. Technologically, dyadic simulations can model emergent systems; AI architectures might exploit dyadic networks for adaptive, context-sensitive intelligence; and ethical reflection can re-centre on relational alignment.

Figure 5.

Emergent Consciousness of Dyadic Networks.

Figure 5.

Emergent Consciousness of Dyadic Networks.

6. Case Studies and Models

Conceptual case studies render the framework tangible. In a Dyadic Universe Simulation [

2], the only primitives are dyads and Logos-based rules. Iterative interactions yield stable clusters (analogous to particles), expanding networks (spacetime-like growth), and recurrent relational regularities (law-like patterns). A second case concerns consciousness: dyads representing neural or sub-neural relations achieve dense connectivity and global integration, producing holistic informational states corresponding to awareness. These models do not prove the ontology but demonstrate its generative adequacy across domains.

Figure 6.

Dyadic Universe Simulation (schematic clusters and links).

Figure 6.

Dyadic Universe Simulation (schematic clusters and links).

Figure 7.

Consciousness Emergence Model.

Figure 7.

Consciousness Emergence Model.

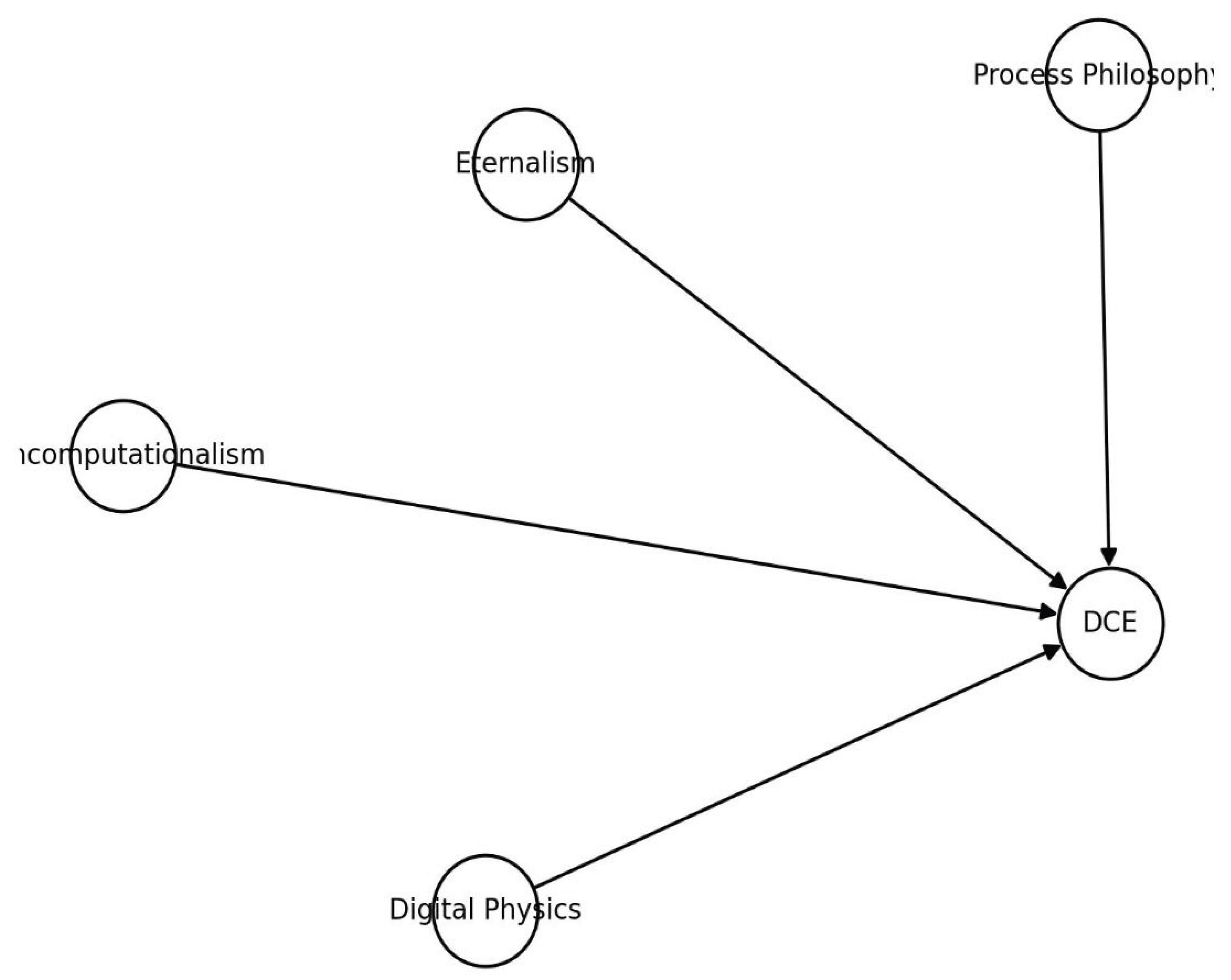

7. Comparison with Existing Theories

Comparison clarifies novelty. Classical eternalism treats events as basic and often neglects emergence and consciousness. Digital physics [

7,

12,

19,

22,

24] posits bits or qubits as primitives, but these are context-free compared to dyads’ intrinsically relational character. Pancomputationalism views reality as computation, which DCE grounds ontologically in dyadic structure. Process philosophy [

23] aligns in privileging processes, yet DCE specifies dyads as irreducible units of process. Quantum information approaches resonate with DCE’s informationalism and gain a relational foundation for entanglement and superposition.

Figure 8.

Comparisons with Existing Theories.

Figure 8.

Comparisons with Existing Theories.

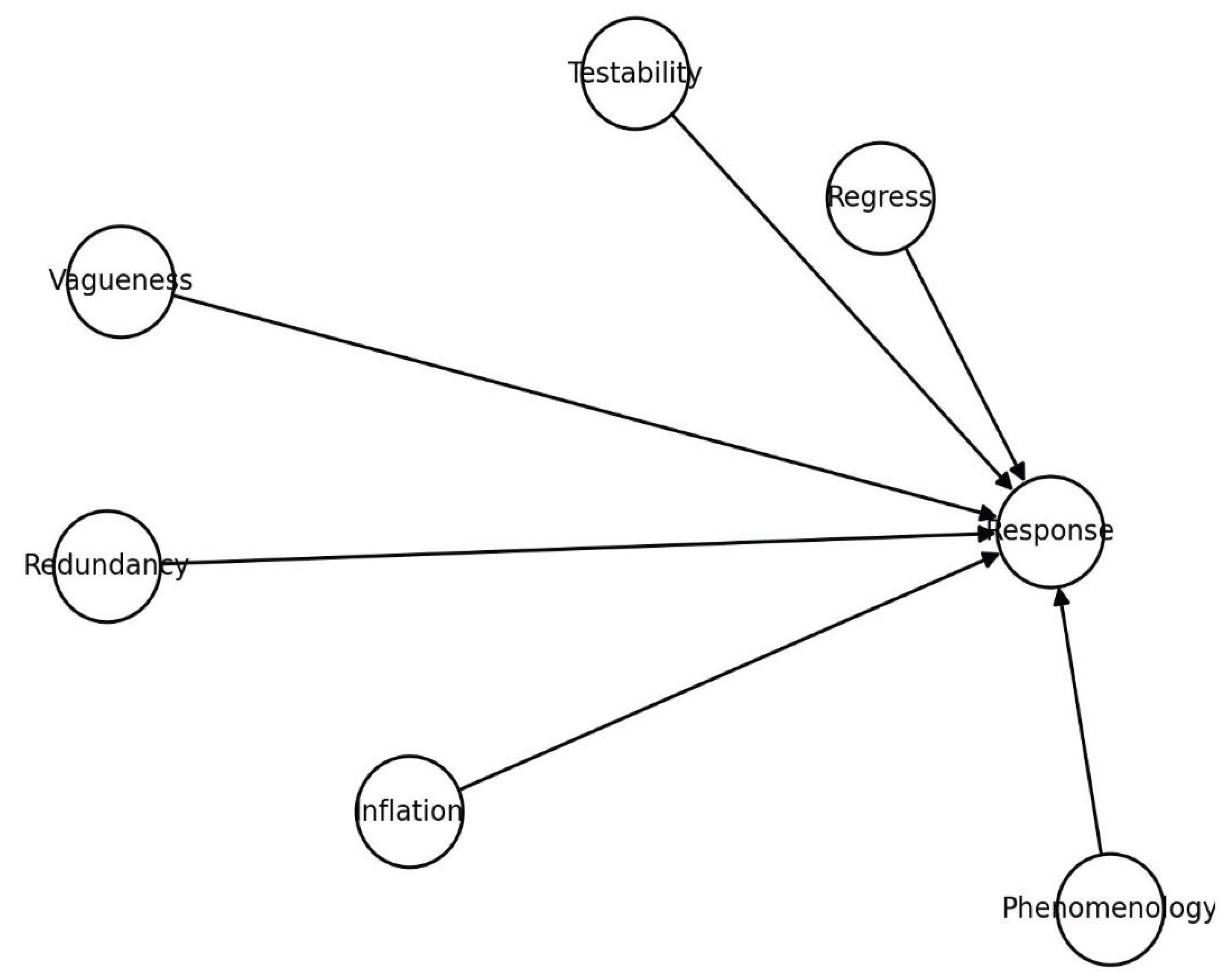

8. Critiques and Objections

Several objections merit consideration. (1) Testability: while dyads are not directly observable, dyadic models can yield testable correlates (e.g., measures of informational integration in neuroscience [

20,

21]). (2) Ontological Inflation: dyads reduce, rather than inflate, ontology by embedding relation within the primitive. (3) Redundancy with Digital Physics: dyads differ from bits by encoding context intrinsically [

7,

12,

19,

22,

24]. (4) Infinite Regress: the relata of a dyad do not pre-exist the relation; the dyad is irreducible. (5) Vagueness of Logos: made precise via the three principles and formal simulation. (6) Phenomenology of Time: subjective flow is an emergent cognitive phenomenon within an eternalist dyadic network.

Figure 9.

Objections vs Responses (dialectical map).

Figure 9.

Objections vs Responses (dialectical map).

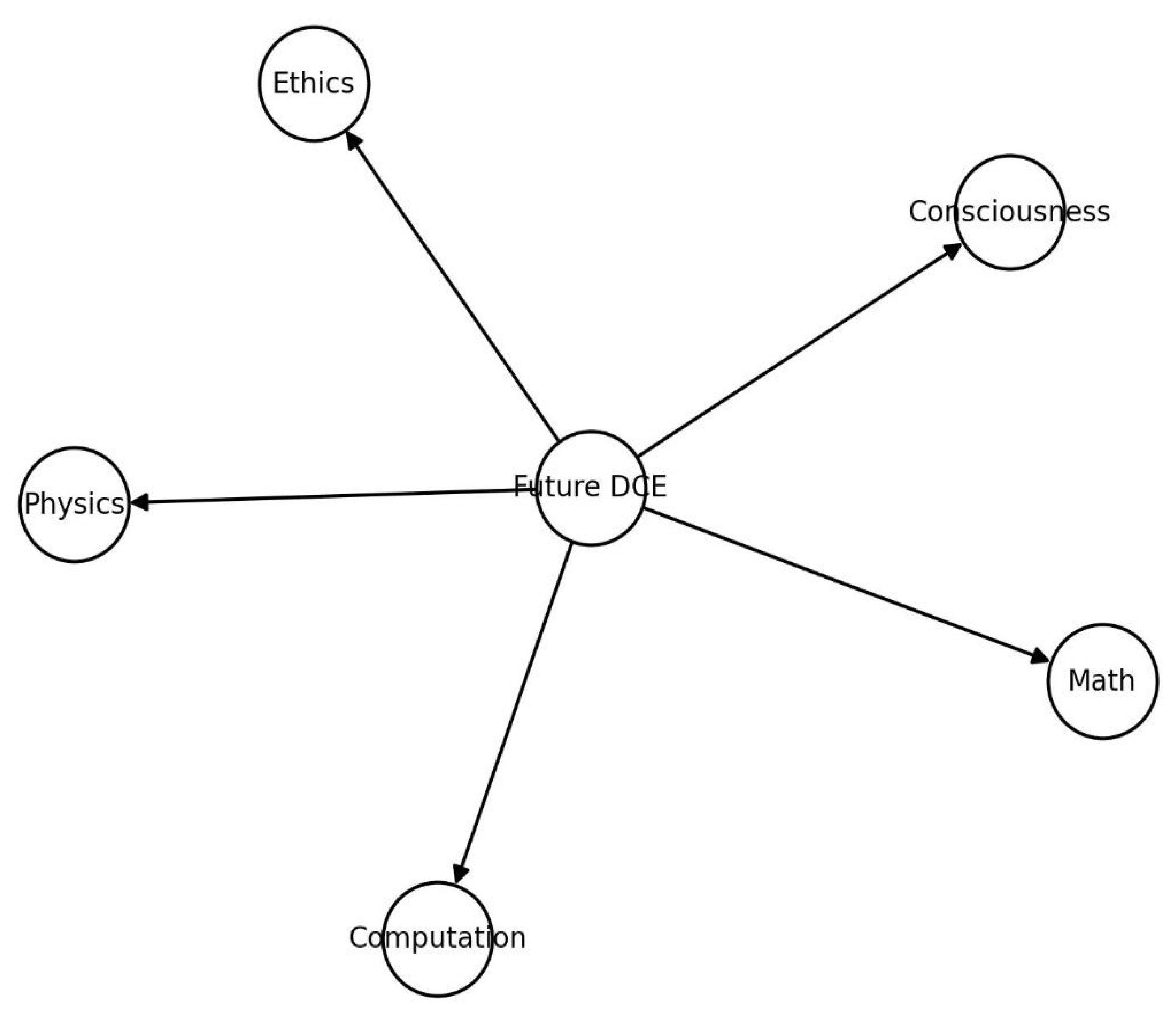

9. Future Directions

Future work proceeds along three tracks. First, formaldevelopment: an algebra of dyads, network and category-theoretic formulations. Second, computational modelling: minimal dyadic universes, benchmarks against cellular automata, and dyadic AI architectures. Third, integration with physics and mind sciences: representations of entanglement and spacetime layering; correlates of dyadic integration with conscious states; and ethical reframing around relational alignment. Interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential to refine, test, and extend the framework.

Figure 10.

Future Research Pathways.

Figure 10.

Future Research Pathways.

10. Conclusions

This paper has articulated DCE as a coherent, relational-informational ontology. Dyads, as primitive relational pairs, and the Dyadic Logos, as intrinsic interaction grammar, jointly account for persistence, emergence, and temporal organisation. DCE reframes time, causality, and freedom; unifies insights from metaphysics, physics, and cognitive science; and motivates concrete research programmes in modelling and formalisation. While speculative, DCE is generative: it seeks not closure but an open, fertile landscape of inquiry in which reality is intelligible as a persistent web of dyadic relations.

References

- Aristotle, The Complete Works of Aristotle (J. Barnes, Ed.). Princeton University Press, 1984.

- N. Bostrom, ``Are you living in a computer simulation?,’’ Philosophical Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 211, pp. 243--255, 2003. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Chalmers, The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. Oxford University Press, 1996.

- D. J. Chalmers, Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy. W. W. Norton, 2022.

- T. Deacon, Incomplete Nature: How Mind Emerged from Matter. W. W. Norton, 2011.

- D. C. Dennett, Consciousness Explained. Little, Brown and Company, 1991. [CrossRef]

- E. Fredkin, ``An introduction to digital philosophy,’’ International Journal of Theoretical Physics, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 189--247, 2003.

- Heraclitus, Fragments: The Collected Wisdom of Heraclitus (B. Haxton, Trans.). Viking, 2001.

- G. W. F. Hegel, The Science of Logic (G. di Giovanni, Trans.). Cambridge University Press, 2010 (orig. 1812).

- S. Kauffman, At Home in the Universe: The Search for the Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity. Oxford University Press, 1995. [CrossRef]

- G. W. Leibniz, Philosophical Essays (R. Ariew \& D. Garber, Eds.). Hackett Publishing, 1989.

- S. Lloyd, Programming the Universe: A Quantum Computer Scientist Takes on the Cosmos. Knopf, 2006.

- J. M. E. McTaggart, ``The unreality of time,’’ Mind, vol. 17, no. 68, pp. 457--474, 1908. [CrossRef]

- M. Mitchell, Complexity: A Guided Tour. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Plato, Timaeus (D. J. Zeyl, Trans.). Hackett Publishing, 2008.

- Prigogine, From Being to Becoming: Time and Complexity in the Physical Sciences. W. H. Freeman, 1980. [CrossRef]

- H. Putnam, ``Time and physical geometry,’’ Journal of Philosophy, vol. 64, no. 8, pp. 240--247, 1967.

- W. Stoeger, ``Eternalism, the block universe, and cosmology,’’ in Studies in Science and Theology, vol. 6, pp. 185--200, 1998.

- M. Tegmark, Our Mathematical Universe: My Quest for the Ultimate Nature of Reality. Vintage, 2014.

- G. Tononi, ``An information integration theory of consciousness,’’ BMC Neuroscience, vol. 5, no. 42, 2004. [CrossRef]

- G. Tononi and C. Koch, ``Consciousness: Here, there and everywhere?,’’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, vol. 370, no. 1668, 2015.

- J. A. Wheeler, ``Information, physics, quantum: The search for links,’’ in W. H. Zurek (Ed.), Complexity, Entropy, and the Physics of Information, pp. 3--28, Addison-Wesley, 1990.

- N. Whitehead, Process and Reality. Macmillan, 1929.

- K. Zuse, Rechnender Raum. Friedrich Vieweg \& Sohn, 1969.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).