Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

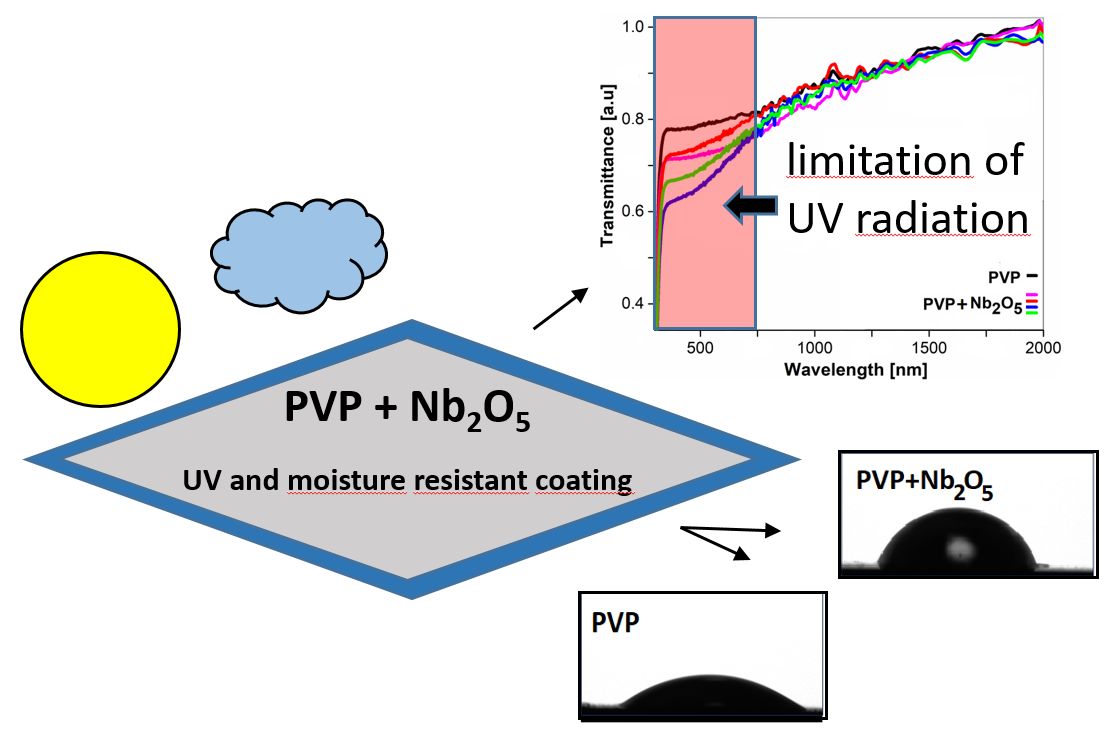

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

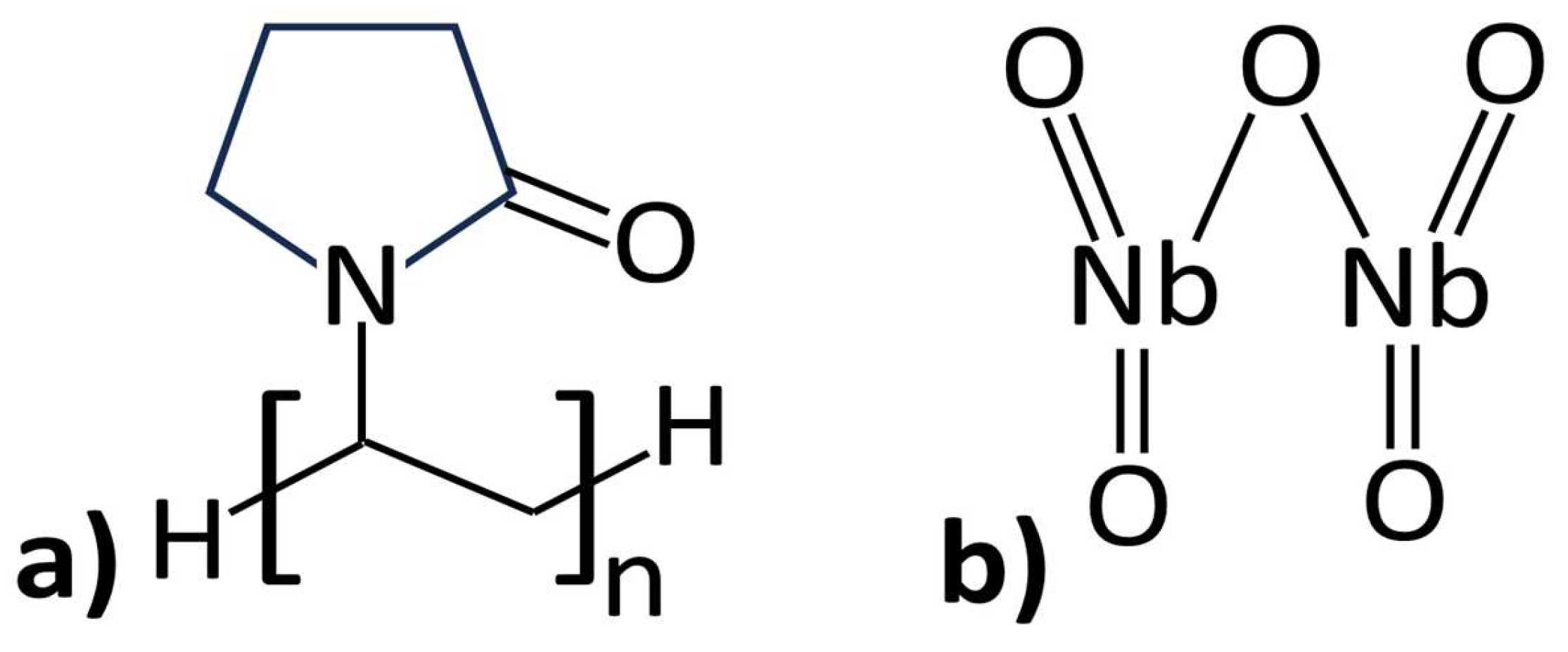

2.1. Materials and Samples Preparation

2.2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

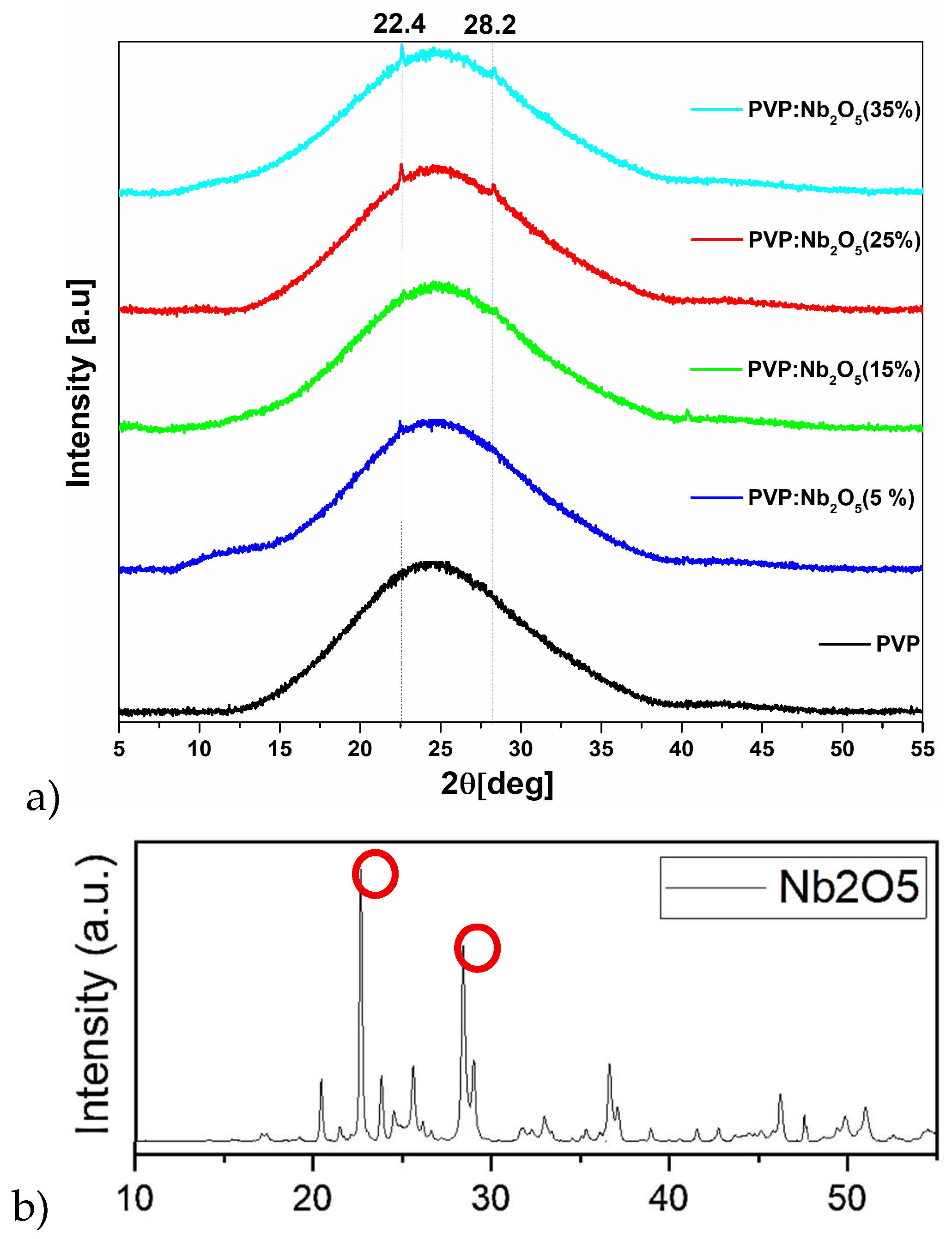

3.1. XRD Analysis

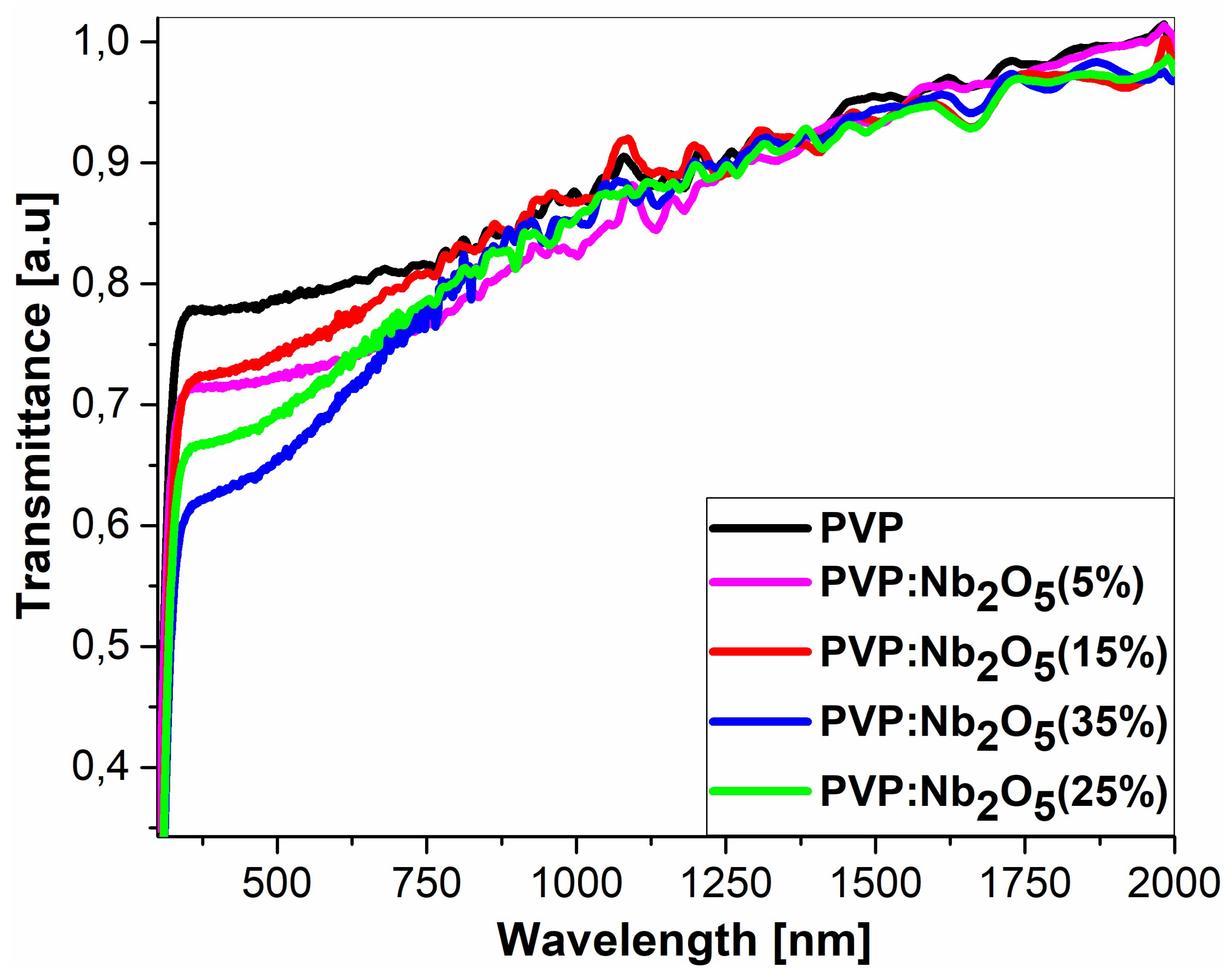

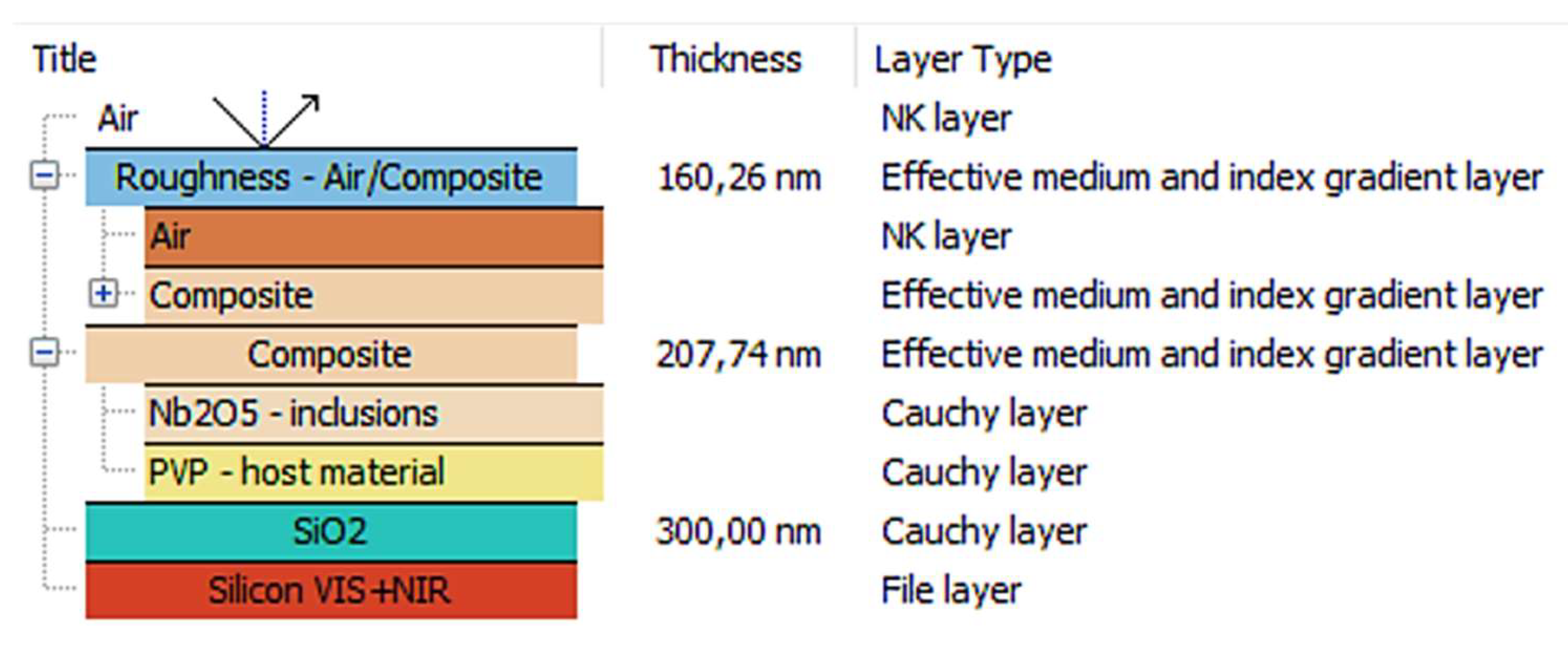

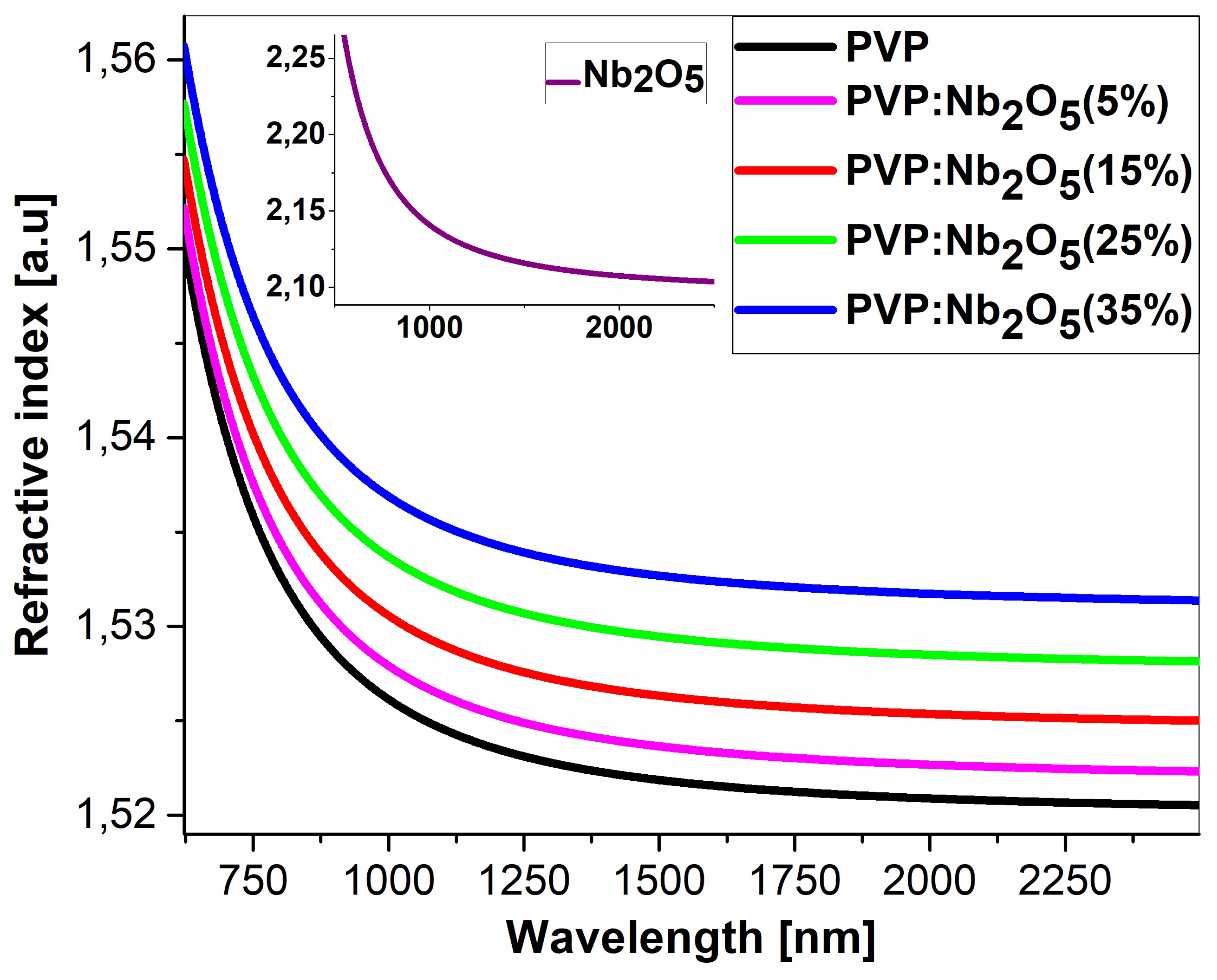

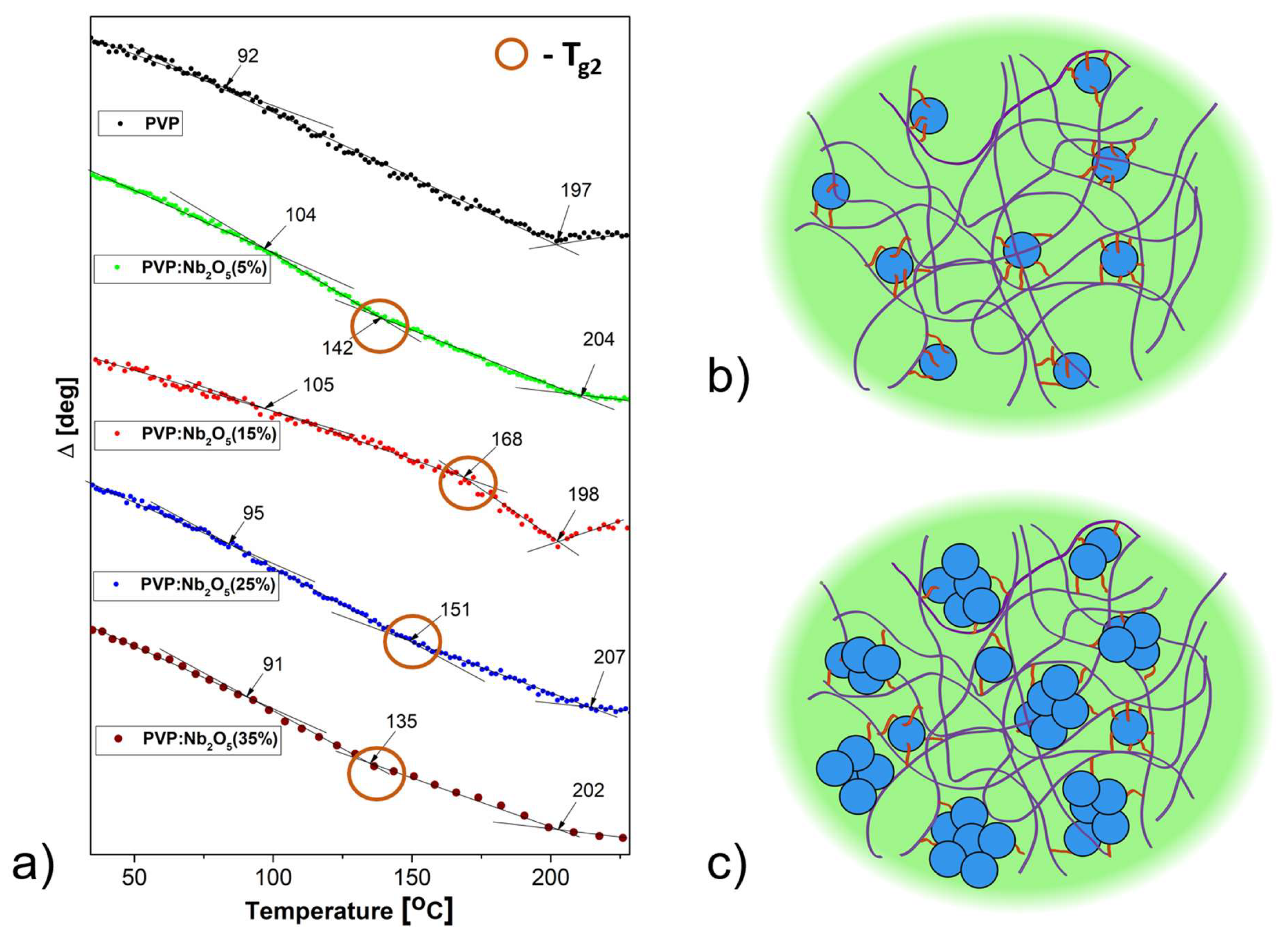

3.2. Ellipsometric Analysis

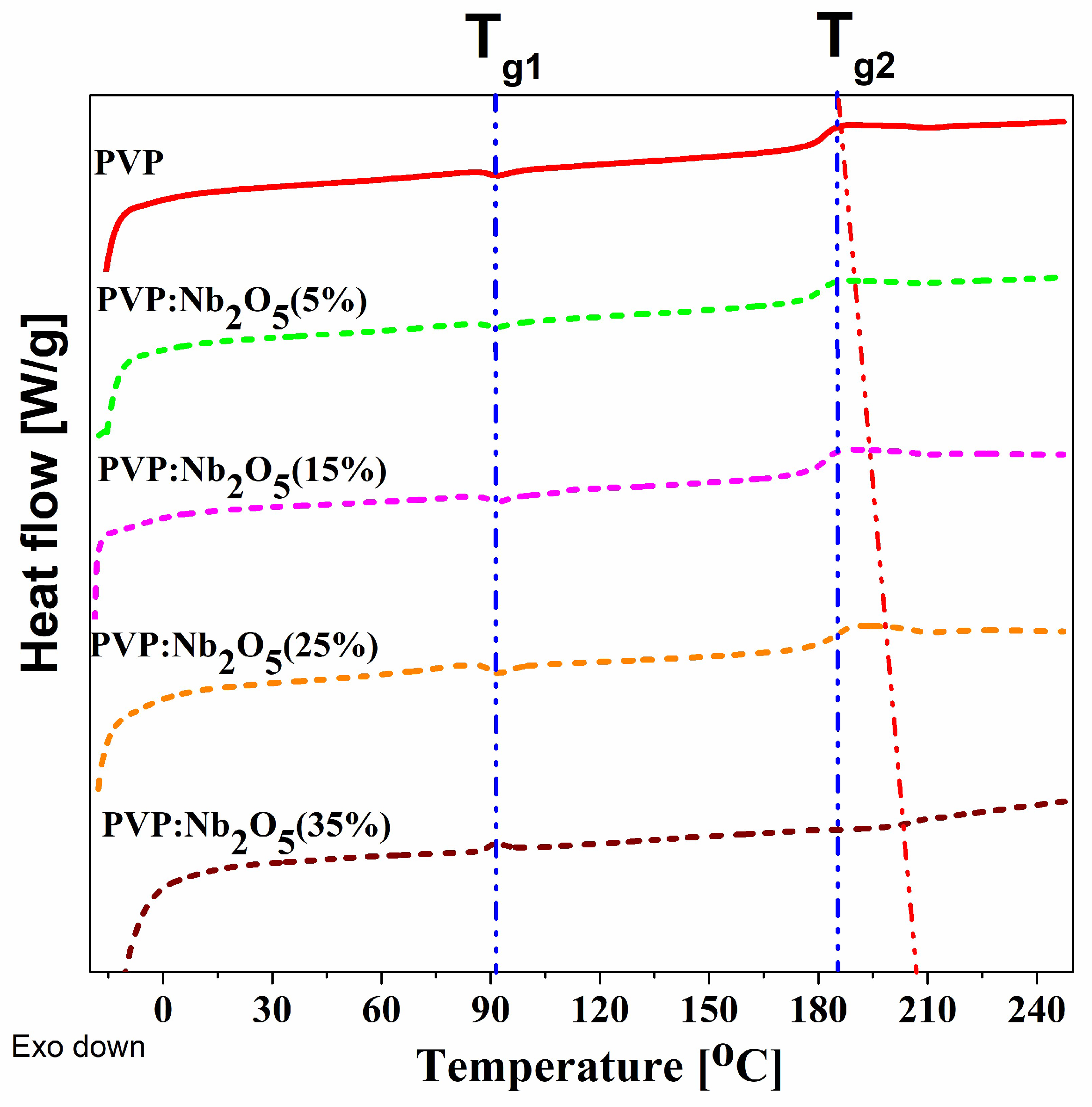

3.3. Thermal Analysis

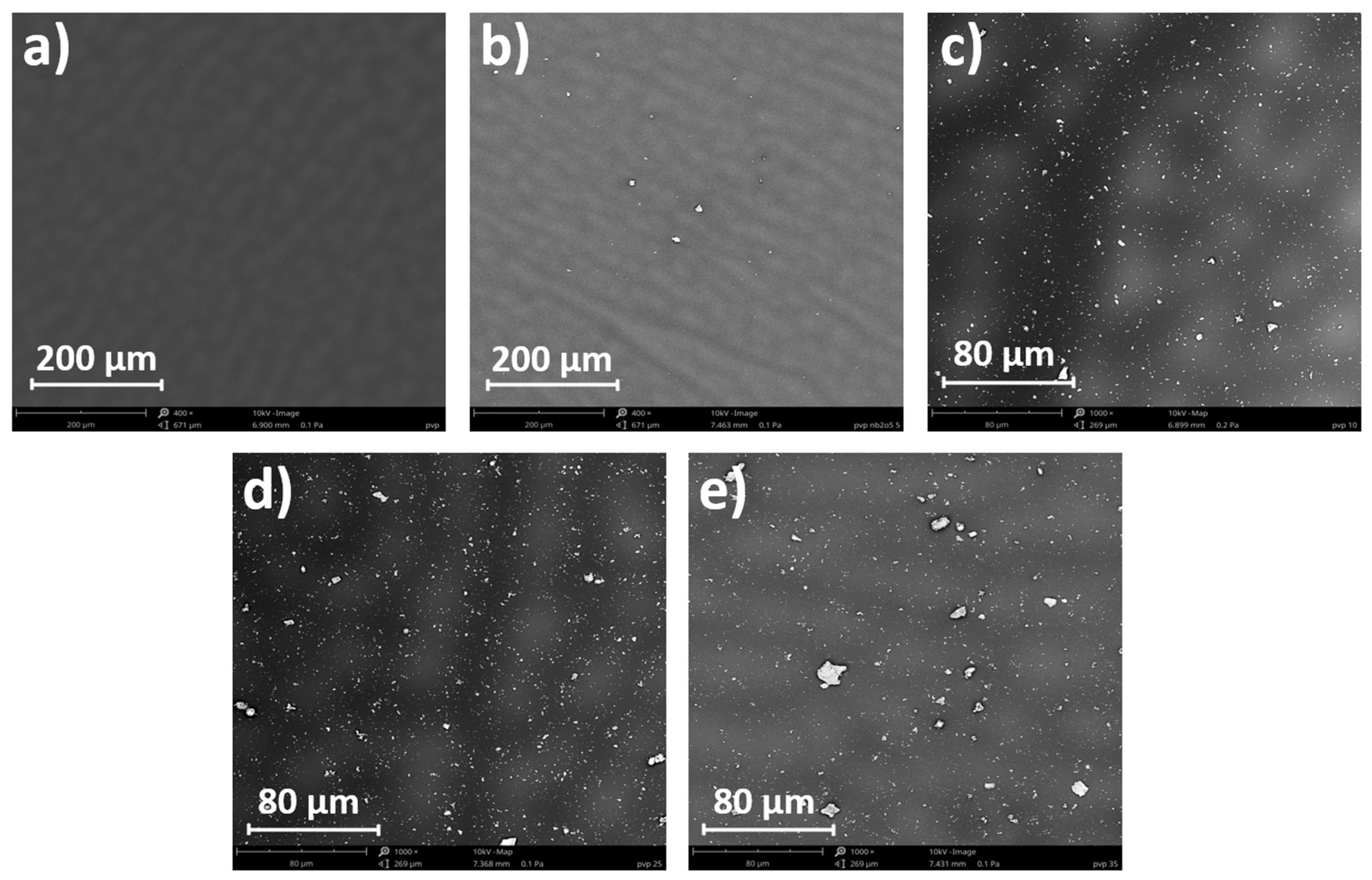

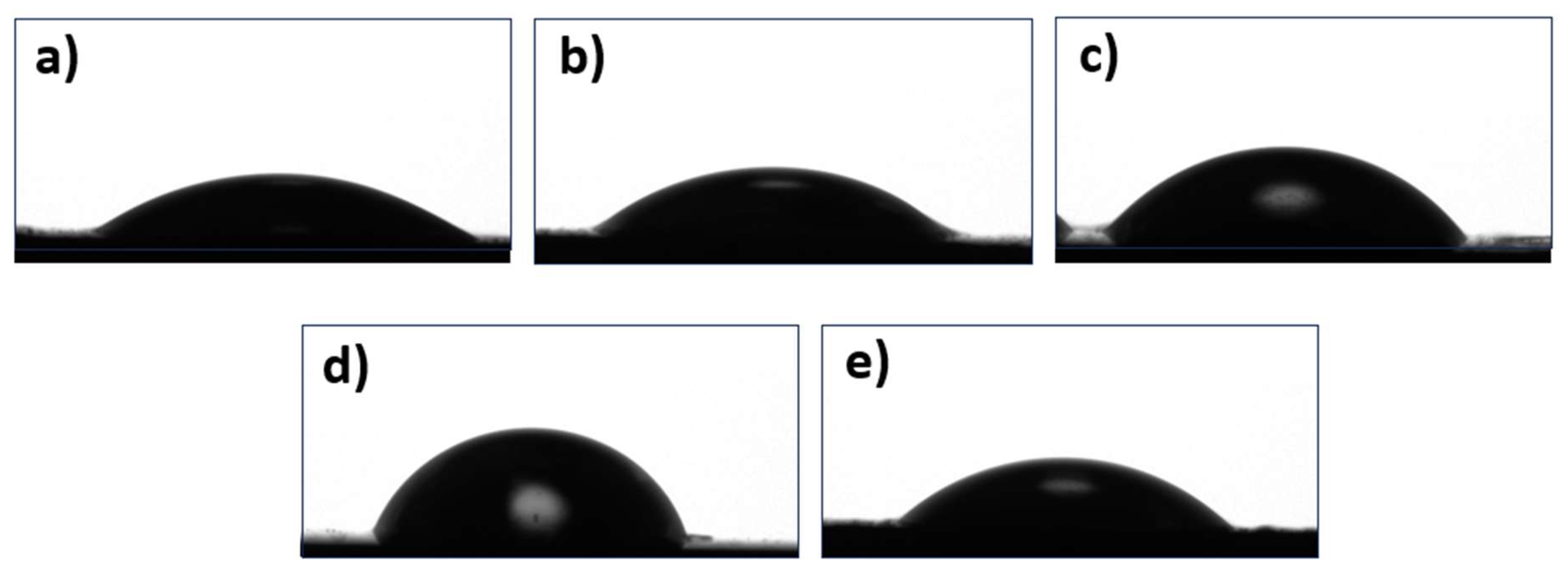

3.4. Microscopic and Contact Angle Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manias, E. The full potential of nanoparticles in imparting new functionalities in polymer nanocomposites remains largely untapped. A widely applicable, two-solvent processing approach provides a hierarchical structure, affording unparalleled composite performance enhancement. Nanocomposites: Stiffer by design. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.M.; Liou, S.J.; Lin, C.Y.; Cheng, C.Y.; Chang, Y.W.; Tsai, T.Y.; Wu, C.Y. Anticorrosively Enhanced PMMA−Clay Nanocomposite Materials with Quaternary Alkylphosphonium Salt as an Intercalating Agent. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathai, S.; Shaji, P.S. Polymer-Based Nanocomposite Coating Methods: A Review. J. Sci. Res. 2022, 14, 973–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.; Budholiya, S.; Raj, S.A.; Sultan, M.; Hui, D.; Shah, A.M.; Safri, S. Review on nanocomposites based on aerospace applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2021, 10, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Khan, K.H.; Parvez, M.M.H.; Irizarry, N.; Uddin, M.N. Polymer Nanocomposites with Optimized Nanoparticle Dispersion and Enhanced Functionalities for Industrial Applications. Processes 2025, 13, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Gandy, H.T.N.; Rahman, M.M.; Asmatulu, R. Adhesiveless honeycomb sandwich structures of prepreg carbon fiber composites for primary structural applications. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2019, 2, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Lei, B. Transparent sunlight conversion film based on carboxymethyl cellulose and carbon dots. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 151, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, M.M.; Toprak, M.S.; Kim, D.K.; Muhammed, M. Nanocomposites of polymer and inorganic nanoparticles for optical and magnetic applications. Nano Rev. 2010, 1, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, V.; Blanchet, P. Color stability for wood products during use: Effects of inorganic nanoparticles. BioResources 2011, 6, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Look, D.C. Recent advances in ZnO materials and devices. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2001, 80, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.H.; Prajapat, A.L. Biopolymer Nanocomposites for Sustainable UV Protective Packaging. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 855727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, Y.; Mohammed, M.I.; Elsaeedy, H.I.; Yahia, I.S. Optical and electrical properties of SnBr2-doped polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) polymeric solid electrolyte for electronic and optoelectronic applications. Optik 2021, 228, 166129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. S. Tarazona, M. Tafur, J. Quispe-Marcatoma, C.V. Landauro, E. Baggio-Saitovitch, D.S. Schmool. Thickness effect on the easy axis distribution in exchange biased Co/IrMn bilayers. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2019, 570, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, A. Engineering the optical properties of PVA/PVP polymeric blend in situ using tin sulfide for optoelectronics. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2020, 126, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, S.M.; Gorham, J.M.; Tana, J.; Hackley, V.A. Ultraviolet photo-oxidation of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) coatings on gold nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Nano 2017, 4, 1866–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.M.; Kim, N.Y.; Shin, S.; Lee, J.H.; Ryu, J.Y.; Eom, T.; Park, B.K.; Kim, C.G.; Chung, T.-M. Synthesis of novel volatile niobium precursors containing carboxamide for Nb2O5 thin films. Polyhedron 2021, 200, 115134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuvalingam, S.B.; Macco, B.; Knoops, H.C.M.; Melskens, J.; Kessels, W.M.M.; Bol, A.A. Comparison of thermal and plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of niobium oxide thin films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2018, 36, 041503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Pereira, M.; de Sousa Lima, F.A.; de Almeida, R.Q.; da Silva Martins, J.L.; Bagnis, D.; Barros, E.B.; Sombra, A.S.B.; de Vasconcelos, I.F. Flexible, large-area organic solar cells with improved performance through incorporation of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles in the active layer. Mater. Res. 2019, 22, e20180640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-C.; Su, Y.-H.; Hung, Y.-K.; Yeh, C.-S.; Huang, L.-W.; Gomulya, W.; Lai, L.-H.; Loi, M.A.; Yang, J.-S.; Wu, J.-J. Charge collection enhancement by incorporation of gold–silica core–shell nanoparticles into P3HT:PCBM/ZnO nanorod array hybrid solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 19854–19861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-M.; Chiang, C.-H.; Hsu, S.L.-C. The performance of polymer solar cells based on P3HT:PCBM after post-annealing and adding titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Innov. 2014, 18, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshin, A.N. Organic optoelectronics based on polymer—inorganic nanoparticle composite materials. Phys. Usp. 2013, 56, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshin, A.N.; Shcherbakov, I.P. A light-emitting field-effect transistor based on a polyfluorene–ZnO nanoparticles film. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2010, 43, 315104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshin, A.N.; Kim, D.W.; Park, S.H.; Lee, C.; Lee, S. Solution-processed polyfluorene-ZnO nanoparticles ambipolar light-emitting field-effect transistor. Org. Electron. 2011, 12, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.E.; Phenrat, T.; Marinakos, S.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, J.; Wiesner, M.R.; Tilton, R.D.; Lowry, G.V. Hydrophobic interactions increase attachment of gum arabic- and PVP-coated Ag nanoparticles to hydrophobic surfaces. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 5988–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebali, S.; Vayer, M.; Belal, K.; Sinturel, C. Engineered nanocomposite coatings: From water-soluble polymer to advanced hydrophobic performances. Materials 2024, 17, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, E.; Ali, M.K.M.; Allam, N.K. Tuning the optical properties and hydrophobicity of BiVO4/PVC/PVP composites as potential candidates for optoelectronics applications. Opt. Mater. 2024, 150, 115193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaf, F.; Sanner, A.; Straub, F. Polymers of N-vinylpyrrolidone: Synthesis, characterization and uses. Polym. J. 1985, 17, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurakula, M.; Rao, G.S.N.K. Pharmaceutical assessment of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP): As excipient from conventional to controlled delivery systems with a spotlight on COVID-19 inhibition. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.U.; Rudokaite, A.; da Silva, A.M.H.; Kirsnyte-Snioke, M.; Stirke, A.; Melo, W.C.M.A. A comprehensive review of niobium nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, applications in health sciences, and future challenges. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, O.F.; Paris, E.C.; Ribeiro, C. Synthesis of Nb2O5 nanoparticles through the oxidant peroxide method applied to organic pollutant photodegradation: A mechanistic study. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 144, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, B.; Bednarski, H.; Jarząbek, B.; Janeczek, H.; Nitschke, P. Optical and thermal properties of Nb2O5 nanocomposites. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, B.; Bednarski, H.; Jarząbek, B.; Nitschke, P.; Janeczek, H. Phase diagram of P3HT:PC70BM thin films based on variable-temperature spectroscopic ellipsometry. Polym. Test. 2020, 84, 106383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, B.; Bednarski, H.; Jarka, P.; et al. Thermal and optical properties of PMMA films reinforced with Nb2O5 nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, B.; Jarka, P.; Tański, T.; Bednarski, H.; Janeczek, H.; Gnida, P.; Fijalkowski, M. An investigation of the thermal transitions and physical properties of semiconducting PDPP4T:PDBPyBT blend films. Materials 2022, 15, 8392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, B.; Bednarski, H.; Domański, M.; Jarząbek, B.; Trzebicka, B. Thermal transitions in P3HT: PC60BM films based on electrical resistance measurements. Polymers 2020, 12, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, U. SpectraRay/3 Software Manual; Sentech Instruments GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stoumbou, E.; Stavrakas, I.; Hloupis, G.; Alexandridis, A.; et al. , A comparative study on the use of the extended-Cauchy dispersion equation for fitting refractive index data in crystals. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2013, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.I.; Gadd, G.E.; Town, G.E. Total differential optical properties of polymer nanocomposite materials. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, ICONN 2006; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; 2006; pp. 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buera, M.D.P.; Levi, G.; Karel, M. Glass transition in poly(vinylpyrrolidone): Effect of molecular weight and diluents. Biotechnol. Prog. 1992, 8, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidannyk, V.A.; Mishra, V.S.N.; Miao, S.; Djali, M.; McCarthy, N.; Nurhadi, B. The effect of polyvinylpyrrolidone addition on microstructure, surface aspects, the glass transition temperature and structural strength of honey and coconut sugar powders. J. Future Foods 2022, 2, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatica, N.; Soto, L.; Moraga, C.; Vergara, L. Blends of poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) and dihydric phenols: Thermal and infrared spectroscopic studies. Part IV. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2013, 58, 1978–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, I.; Velásquez, E.; Galotto, M.; Guarda, A. Influence of the molar mass and concentration of polyvinylpyrrolidone on the physical–mechanical properties of polylactic acid for food packaging. Polymers 2025, 17, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Dranca, I. Probing beta relaxation in pharmaceutically relevant glasses by using DSC. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, T.G.; Flory, P.J. The glass temperature and related properties of polystyrene. Influence of molecular weight. J. Polym. Sci. 1954, 14, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarka, P.; Hajduk, B.; Kumari, P.; Janeczek, H.; Godzierz, M.; Tsekpo, Y.M.; Tański, T. Investigations on thermal transitions in PDPP4T/PCPDTBT/AuNPs composite films using variable temperature ellipsometry. Polymers 2025, 17, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, B.; Jarka, P.; Bednarski, H.; et al. Thermal and optical properties of P3HT:PC70BM: ZnO nanoparticles composite films. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.P.; Lipson, J.E.G.; Keddie, J.L. Spectroscopic ellipsometry as a route to thermodynamic characterization. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 6660–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Hu, S.; Zhang, S.; Peera, A.; Reffner, J.; Torkelson, J. M. Eliminating the Tg-Confinement Effect in Polystyrene Films: Extraordinary Impact of a 2 mol % 2-Ethylhexyl Acrylate Comonomer. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 9601–9611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna, S.; Wang, T.; Torkelson, J.M. Eliminating the Tg-confinement and fragility-confinement effects in poly(4-methylstyrene) films by incorporation of 3 mol % 2-ethylhexyl acrylate comonomer. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 160, 034903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.E.; Sayed, M.A.; Algarni, H.; Khairy, Y.; Abdel-Aziz, M.M. Use of niobium oxide nanoparticles as nanofillers in PVP/PVA blends to enhance UV–visible absorption, opto-linear, and nonlinear optical properties. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2022, 28, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nb2O5 content (%) | 0 | 10 | 15 | 25 | 35 |

|

PVP weight (mg) |

20 | 18 | 17 | 15 | 13 |

|

Nb2O5 Weight (mg) |

0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 7 |

| Thin Film | PVP |

PVP: Nb2O5(5%) | PVP: Nb2O5(15%) | PVP: Nb2O5(25%) | PVP: Nb2O5(35%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Refractive index n [a.u] (for λ=2500nm) |

1.521 |

1.522 |

1.525 |

1.528 |

1.531 |

|

Fraction coefficient f [a.u] |

0 |

0.004 |

0.010 |

0.017 |

0.024 |

|

Thickness of samples on SiO2 d [nm] |

303 |

371 |

255 |

466 |

208 |

|

Roughness of samples on SiO2 r [nm] |

146 |

134 |

128 |

162 |

160 |

|

Thickness of samples on micr. cover glass d [nm] |

257 |

302 |

270 |

285 |

340 |

|

Roughness of samples on micr. cover glass r [nm] |

101 |

120 |

97 |

115 |

134 |

| DSC (powder) | Temperature ellipsometry (films) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Tg1 (℃) |

Tg2 (℃) | TgV1 (℃) |

TgV2 (℃) | TgV3 (℃) |

| PVP | 88 | 188 | 92 | - | 197 |

| PVP: Nb2O5 (5%) | 88 | 181 | 104 | 142 | 204 |

| PVP: Nb2O5 (15%) | 88 | 180 | 105 | 168 | 198 |

| PVP: Nb2O5 (25%) | 89 | 183 | 95 | 151 | 207 |

| PVP: Nb2O5 (35%) |

88 | 204 | 91 | 135 | 202 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).