Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Scope and Contributions

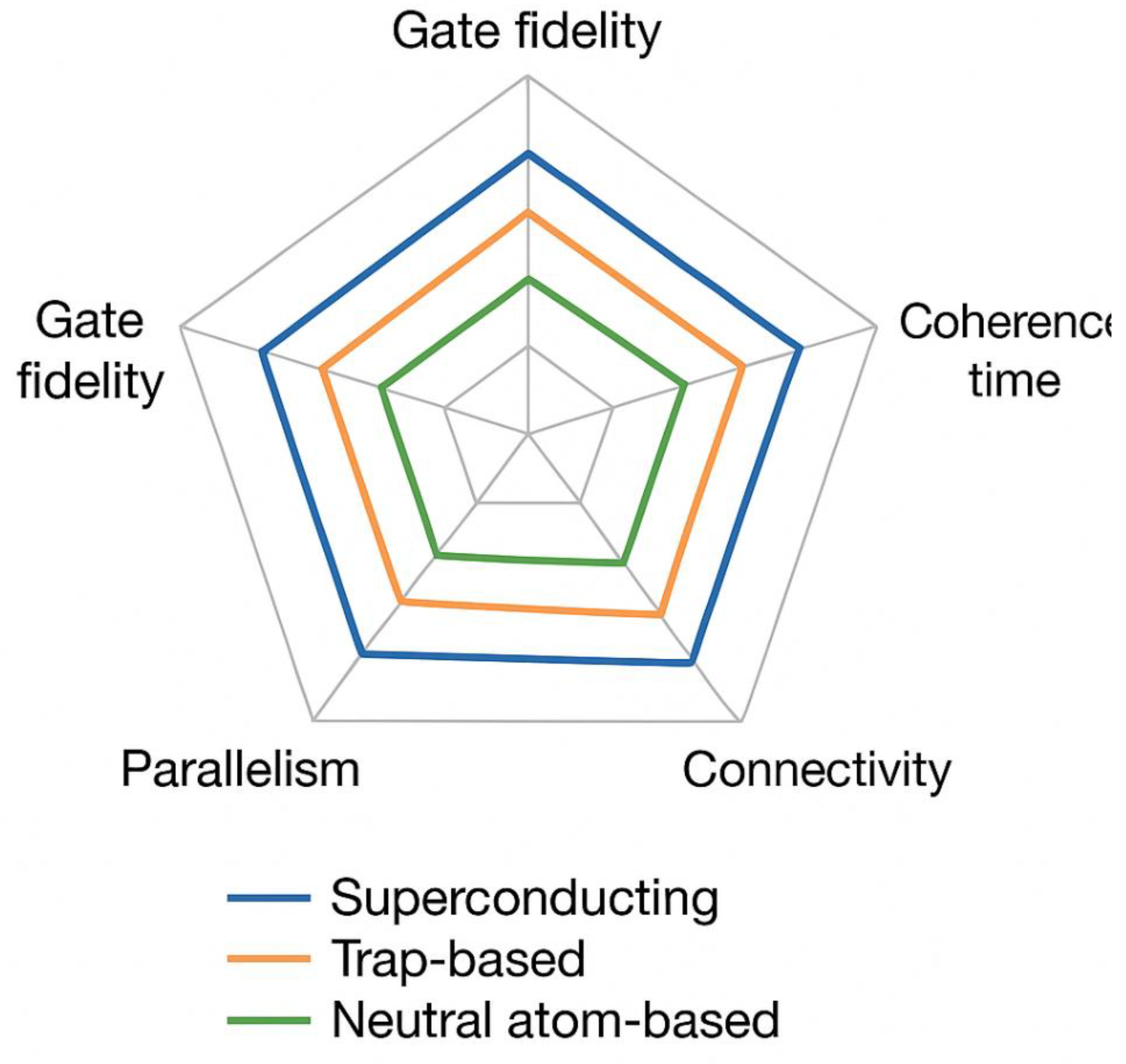

- Hardware Implementations: Detailed examination of QEC demonstrations across superconducting, trapped-ion, and emerging quantum platforms

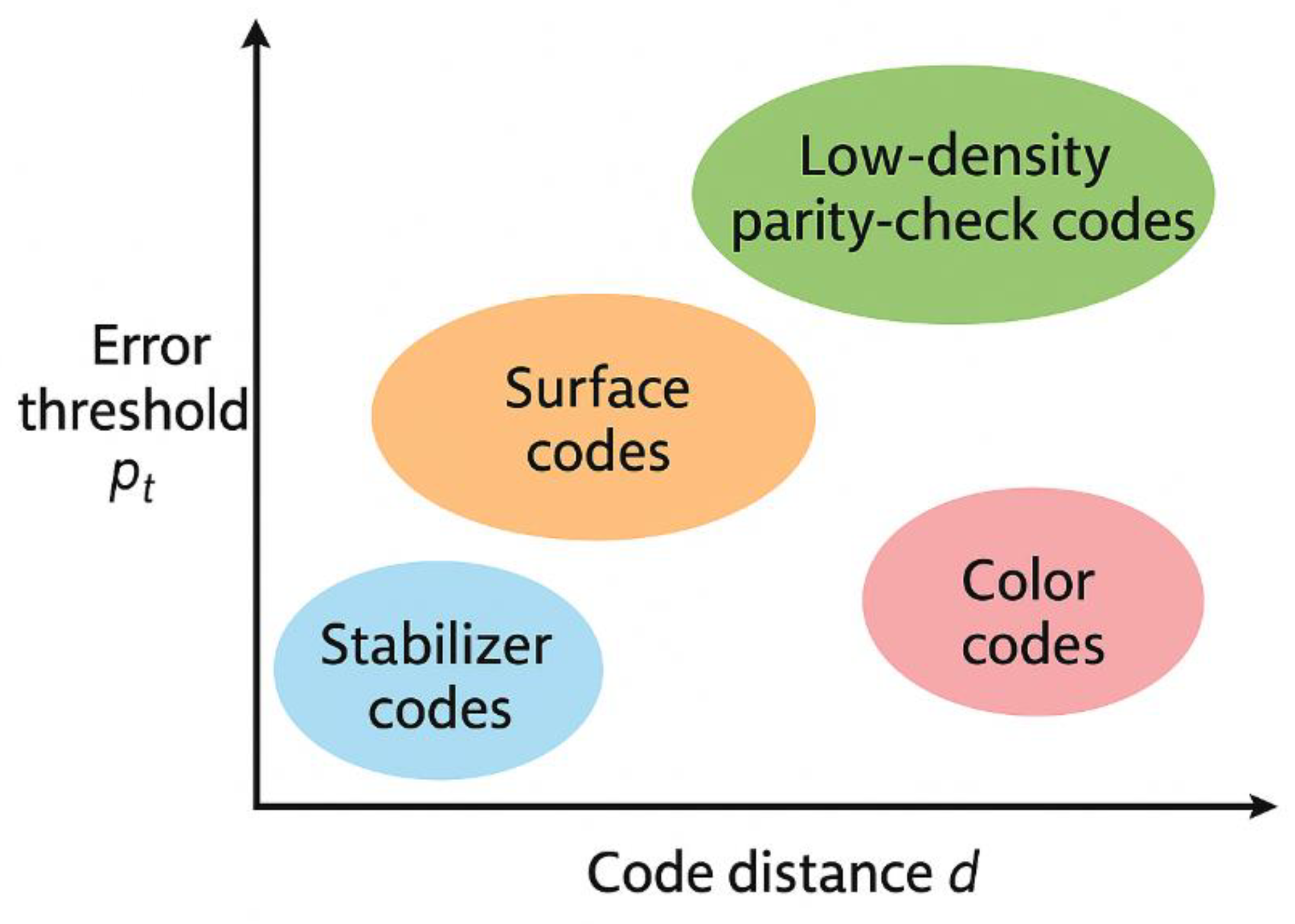

- Code Performance Analysis: Comparative evaluation of surface codes, LDPC codes, and alternative QEC schemes with quantitative metrics

- Decoder Algorithms: Assessment of classical and machine learning-based decoding approaches with complexity and performance analysis

- Fault-Tolerant Architectures: Analysis of complete quantum computing stacks from physical to logical layers

- Engineering Challenges: Identification of key obstacles to scalable fault-tolerant systems with proposed solutions

- Resource Estimation: Quantitative analysis of physical qubit requirements for practical applications

1.2. Information-Theoretic Perspective

2. Theoretical Foundations and Recent Developments

2.1. Quantum Error Models and Syndrome Entropy

- Coherent errors that preserve some quantum coherence and can interfere constructively or destructively [14]

- Leakage errors to non-computational states, effectively removing qubits from the computational space [15]

- Measurement errors in syndrome extraction, with typical error rates of 1-5% per measurement [16]

- Biased noise where different Pauli error types occur with different probabilities [17]

2.2. Fault-Tolerance Thresholds

| Code Family | Threshold (i.i.d.) | Circuit-level | Meas. Errors | Resource Overhead | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Code | 1.1% | 0.57% | 0.43% | O(d²) qubits | [21] |

| Color Code | 0.31% | 0.2% | 0.15% | O(d²) qubits | [22] |

| LDPC Codes | 1.9% | 1.2% | 0.8% | O(d log d) qubits | [23] |

| Concatenated | 3.0% | 1.0% | 0.6% | O(d^log₂ n) qubits | [24] |

| Bacon-Shor | 1.8% | 0.9% | 0.5% | O(d²) qubits | [25] |

2.3. Logical Gate Implementation and Resource Analysis

3. Hardware Platforms and Experimental Achievements

3.1. Superconducting Quantum Processors

3.1.1. Google’s Sycamore Achievements

- System: 70-qubit superconducting processor with tunable couplers

- Code: Surface code with distances d = 3, 5, 7

- Physical error rate: 0.64% per syndrome extraction cycle

- Logical error rates: – d = 3: 2.9% per cycle – d = 5: 0.8% per cycle – d = 7: 0.3% per cycle

- Cycle time: 1.6 μs for syndrome extraction

- Coherence times: T₁ ∼ 100 μs, T₂* ∼ 50 μs

- Gate fidelities: 99.4% (single-qubit), 99.2% (two-qubit)

3.1.2. IBM’s Quantum Network Progress

- Distance scaling: Demonstration of d = 3, 5, 7 surface codes with up to 127 physical qubits

- Real-time processing: Syndrome decoding with <1 μs latency using dedicated FPGA controllers [35]

- Error mitigation integration: Combining QEC with zero-noise extrapolation and symmetry verification [36]

- Modular architecture: Development of quantum-centric supercomputing with classical-quantum integration [37]

- Logical state fidelities: 99.1% logical state preparation and 98.7% logical measurement for d = 3 surface codes [38]

3.1.3. Scaling Challenges

- Coherence limitations: Current T₁ ∼ 100 μs limits achievable code distances to d ≤ 15 before decoherence dominates

- Gate fidelity requirements: Two-qubit gates at 99.2-99.5% approach but don’t consistently exceed the ∼99.9% needed for large-scale fault tolerance

- Connectivity constraints: Fixed nearest-neighbor coupling requires routing overhead for non-planar codes

- Control complexity: Classical control systems require ∼1000 control lines per 100 qubits, necessitating cryogenic electronics [39]

- Crosstalk effects: ZZ-coupling between qubits creates correlated errors that degrade QEC performance [40]

3.2. Trapped-Ion Quantum Computing

3.2.1. Quantinuum and Microsoft Collaboration

- System specifications: – H1-1: 20 qubits, 99.91% two-qubit gate fidelity – H2-1: 56 qubits, 99.8% two-qubit gate fidelity – All-to-all connectivity within register zones

- Coherence properties: >1 minute for hyperfine qubits, >10 seconds for Zeeman qubits

- QEC demonstrations: – 7-qubit Steane code with 99.2% logical state fidelity – 17-qubit surface code with below-threshold operation – LDPC code experiments leveraging all-to-all connectivity [42]

- Advanced capabilities: Real-time conditional operations with <1 μs feedback latency

3.2.2. IonQ and Alpine Quantum Technologies

- Demonstrated 3-qubit repetition codes with 99.8% logical fidelity

- All-to-all connectivity enabling flexible code implementations

- Focus on algorithmic applications with error correction [45]

- 24-qubit Ca⁺ ion system with 99.9% gate fidelities

- Demonstration of 7-qubit color codes

- Research collaboration with University of Innsbruck [46]

3.2.3. Advantages and Current Limitations

- High gate fidelities: > 99.9% two-qubit gates significantly exceed fault-tolerance thresholds

- Long coherence times: Minutes-long coherence enables complex syndrome processing

- All-to-all connectivity: Any-to-any two-qubit gates within ion chains enable diverse code implementations

- Individual addressing: Precise single-qubit control and measurement

- Identical qubits: Atomic ions provide naturally identical qubits with uniform properties

- Gate speed: 10-100 μs gate times vs. 10-100 ns for superconducting qubits

- Limited parallelism: Shared laser resources constrain simultaneous operations

- Scaling challenges: Ion chain instabilities beyond ∼100 ions, requiring complex ion shuttling

- Loading/cooling time: Minutes required to initialize large ion systems

3.3. Emerging Quantum Computing Platforms

3.3.1. Neutral Atom Arrays

- Scalability: >1000 atoms demonstrated in 2D/3D arrays [47]

- Reconfigurable connectivity: Optical tweezers enable arbitrary atom rearrangement

- Long coherence: >1 ms for Rydberg states, >100 ms for ground states

- Parallel operations: Simultaneous gates across large atom ensembles

- 1180-atom system (world’s largest neutral atom quantum computer)

- Demonstrated 7-qubit Steane code with 98.5% logical fidelity

- Focus on optimization and machine learning applications [48]

- 256-atom Aqua system for quantum simulation

- Analog quantum error correction demonstrations

- Collaboration with Harvard on topological codes [49]

3.3.2. Photonic Quantum Computing

- Decoherence immunity: Photons naturally resist thermal decoherence

- Network connectivity: Natural fit for distributed quantum computing

- Room temperature: No cryogenic requirements for photons

- Communication integration: Direct compatibility with quantum networks

- Two-photon gates: Probabilistic gates require extensive error correction overhead

- Photon loss: Primary error mechanism requiring loss-tolerant codes

- State generation: Deterministic single-photon sources remain challenging

- Detection efficiency: Imperfect photodetectors limit measurement fidelity

4. Quantum Error Correction Codes: Comprehensive Analysis

4.1. Surface Codes: The Current Gold Standard

4.1.1. Code Structure and Mathematical Framework

- Physical qubits: n = 2d² − 2d + 1 (including ancilla qubits)

- Logical qubits: k = 1 per patch

- Code distance: d (minimum weight of logical operators)

- X-type stabilizers: (d − 1)² plaquette checks

- Z-type stabilizers: (d − 1)² vertex checks

4.1.2. Performance Scaling Analysis

| Distance | Physical Qubits | Logical Error Rate | T-gate Time (ms) | Space-time Volume | Mem Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d = 3 | 17 | 10⁻³ | 1 | 1.7 × 10⁴ | |

| d = 5 | 41 | 10⁻⁵ | 10 | 4.1 × 10⁵ | |

| d = 7 | 73 | 10⁻⁷ | 100 | 7.3 × 10⁶ | |

| d = 9 | 113 | 10⁻⁹ | 1000 | 1.13 × 10⁸ | |

| d = 11 | 161 | 10⁻¹¹ | 10000 | 1.61 × 10⁹ | |

| d = 13 | 217 | 10⁻¹³ | 100000 | 2.17 × 10¹⁰ |

4.1.3. Recent Theoretical Advances

- Standard surface code: 1.1% threshold for unbiased noise

- Z-biased optimization: Up to 43% threshold for pure dephasing noise

- Practical bias ratios (10:1): 2-5× threshold improvement

-

Rectangle surface codes: Optimized aspect ratios for specific bias [54]Subsystem Surface Codes: Relaxing stabilizer requirements reduces measurement overhead:

- Gauge freedom allows flexible stabilizer measurement

- 25% reduction in syndrome measurements

- Improved performance under measurement errors

-

Simplified decoder implementation due to reduced constraint complexity [25]3D Surface Codes: Extension to three dimensions offers theoretical advantages:

- Improved scaling: Code rate approaches constant vs. O(1/d²) for 2D

- Higher threshold: ∼2.9% vs. 1.1% for 2D surface codes

- Enhanced connectivity: More stabilizer neighbors for error detection

- Implementation challenges: 3D qubit connectivity difficult with current hardware [55]

4.2. Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) Codes

4.2.1. Fundamental Properties and Advantages

- Sparse stabilizers: Each stabilizer generator acts on O(1) qubits (typically 4-12)

- Sparse qubits: Each qubit participates in O(1) stabilizer checks

- Constant rate: R = k/n = Θ(1) logical qubits per physical qubit

- Scaling distance: d = Θ(n^α) with α > 0 (ideally α = 1)

4.2.2. Breakthrough Constructions

- Stabilizer weight: O(√log n)

- First explicit construction with R > 0 and d = ω(log n)

- Based on expander graphs and algebraic geometry

-

Efficient classical preprocessing enables linear-time decodingBalanced Product Codes [57]: Practical constructions with good finite-length performance:

- Distance: d = Θ(√n)

- Rate: R = Θ(1)

- Built from pairs of classical LDPC codes

- Efficient belief propagation decoding

-

Demonstrated thresholds approaching surface code performanceLifted Product Codes: Recent family offering excellent practical performance:

- Systematic construction from group algebra

- Local connectivity properties

- High thresholds: >1.5% under circuit-level noise

- Efficient decoding algorithms [58]

4.2.3. Connectivity and Implementation Challenges

| Code Family | Max Stabilizer Weight | Max Qubit Degree | Connectivity Type | Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toric Code | 4 | 4 | Local (2D grid) | 1.1% |

| Hypergraph Product | O(√n) | O(√n) | Non-local | 0.8% |

| Balanced Product | O(√log n) | O(log n) | Limited non-local | 1.2% |

| Quantum Tanner | O(√log n) | O(log n) | Non-local | 0.1% |

| Lifted Product | 6-8 | 6-8 | Local with routing | 1.5% |

| Good LDPC | O(1) | O(1) | Non-local | >1.0% |

- Platform selection: All-to-all connectivity in trapped ions and neutral atoms

- SWAP networks: Implement non-local gates using ancillary routing qubits

- Code adaptation: Modify codes to fit available connectivity graphs

- Scheduling optimization: Temporal multiplexing of physical connections

4.3. Topological Color Codes

4.3.1. Mathematical Structure and Logical Gates

- Each plaquette corresponds to an X-type or Z-type stabilizer

- Logical operators correspond to homology classes of specific color combinations

- Code distance determined by shortest non-contractible paths

- Physical qubits: n = 3d² − 3d + 1

- Logical qubits: k = 1

- Stabilizers: (3d² − 3d) total (half X-type, half Z-type)

| Logical Gate | Surface Code | Color Code | Resource Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| X̄ | Transversal | Transversal | O(1) |

| Z̄ | Transversal | Transversal | O(1) |

| H̄ | Code deformation | Transversal | Surface: O(d), Color: O(1) |

| S̄ | Magic state | Transversal | Surface: O(log³(1/ε)), Color: O(1) |

| C̄NOT | Lattice surgery | Transversal | Surface: O(d), Color: O(1) |

| T̄ | Magic state | Magic state | O(log³(1/ε)) |

4.3.2. Performance Trade-Offs

| Property | Surface Code | Color Code | Ratio (Color/Surface) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error threshold | 1.1% | 0.31% | 0.28 |

| Physical qubits (d = 5) | 41 | 61 | 1.49 |

| Physical qubits (d = 7) | 73 | 109 | 1.49 |

| Syndrome extraction cycles | d − 1 | d − 1 | 1.0 |

| Transversal Clifford gates | 2 | 6 | 3.0 |

| Magic states per T-gate | O(log³·²(1/ε)) | O(log³·²(1/ε)) | 1.0 |

| Decoder complexity | O(n³) | O(n³) | 1.0 |

4.3.3. Recent Experimental Results

- 19-qubit triangular color code implementation

- All-to-all connectivity enabling optimal layout

- Transversal Clifford group demonstration with >99% fidelity

- Below-threshold operation with logical error rates 0.15% [43]

- 17-qubit 6.6.6 color code on superconducting processor

- Adapted layout for limited connectivity

- Logical error suppression demonstrated: 0.28% logical vs. 0.35% physical

- Transversal Hadamard implementation with 99.2% fidelity [32]

4.4. Alternative Code Families

4.4.1. Concatenated Codes

- Level-1 (inner): Small codes correct single errors (e.g., 7-qubit Steane code)

- Level-2 (outer): Protect against inner code failures

- Recursive construction: Each level reduces effective error rate

- Analysis framework: Well-understood threshold behavior

- Magic state distillation protocols

- Hybrid schemes combining with topological codes

- Specialized decoders for correlated noise environments

- Bootstrap protocols for fault-tolerant gate sets [24]

4.4.2. Bacon-Shor Codes

- Structure: 2D rectangular lattice with gauge qubits

- Stabilizers: Weight-4 operators (similar to surface codes)

- Gauge freedom: Flexibility in syndrome measurement scheduling

- Threshold: ∼1.8% for optimized parameters

- Advantages: Reduced syndrome extraction overhead, bias tolerance

- Applications: Particularly suited for dephasing-dominated noise [25]

5. Decoder Algorithms: Classical and Machine Learning Approaches

5.1. Classical Decoding Algorithms

5.1.1. Minimum-Weight Perfect Matching (MWPM)

- Syndrome processing: Extract defect locations from stabilizer measurements

- Graph construction: • Vertices: syndrome defects plus boundary points • Edges: paths between defects with weights w_ij = − log P(error on path ij) • Boundary handling: Virtual vertices for open boundary conditions

- Matching computation: Apply Edmonds’ blossom algorithm to find minimum-weight perfect matching

- Error correction: Apply Pauli operators corresponding to matched paths

| Decoder | Complexity | Threshold (%) | Memory | Parallelization | Hardware Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWPM | O(n³) | 1.1 | O(n²) | Limited | Good |

| Union-Find | O(nα(n)) | 1.07 | O(n) | Excellent | Excellent |

| Sweep Decoder | O(n²) | 0.9 | O(n) | Good | Very Good |

| MWPM+Clustering | O(n²) | 1.08 | O(n²) | Good | Good |

| Cellular Automaton | O(n) | 0.6 | O(n) | Perfect | Excellent |

| Lookup Table | O(1) | 1.1 | O(2ⁿ) | Perfect | Limited |

- Hierarchical matching: Exploit syndrome locality for average O(n²) complexity

- Parallelization strategies: Divide syndrome regions for parallel processing

- Precomputation: Cache partial solutions for common syndrome patterns

- Hardware acceleration: Custom ASIC implementations achieving <1 μs latency [59]

5.1.2. Union-Find Decoder

- Initialization: Each syndrome defect forms a separate cluster

- Growth phase: Expand clusters uniformly until they merge or reach boundaries

- Union operations: Merge overlapping clusters using union-find data structure

- Path extraction: Derive correction paths from final cluster configuration

- Complexity: O(nα(n)) where α is inverse Ackermann function

- Simplicity: Elementary operations suitable for hardware implementation

- Locality: Operations remain spatially localized

-

Memory efficiency: Linear memory requirements vs. quadratic for MWPMHardware Implementations: Recent FPGA implementations demonstrate:

- Sub-microsecond decoding for d = 5 surface codes

- Linear scaling with code size

- Power consumption <1W for embedded systems

- Real-time operation compatible with syndrome extraction cycles [60]

5.1.3. Belief Propagation for LDPC Codes

- Joint processing: Handle X and Z errors simultaneously to exploit correlations

- Degeneracy resolution: Post-processing to handle non-unique optimal corrections

- Syndrome validation: Verify decoder output satisfies all stabilizer constraints

- Scheduled updates: Optimize message passing order to accelerate convergence [58]

| Code Family | Threshold (%) | Iterations | Convergence Rate | Hardware Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypergraph Product | 0.8 | 20-50 | Good | Moderate |

| Balanced Product | 1.2 | 10-30 | Excellent | Good |

| Lifted Product | 1.5 | 15-40 | Good | Good |

| Quantum Tanner | 0.1 | 50-100 | Poor | High |

| Concatenated LDPC | 1.0 | 25-60 | Good | Moderate |

5.2. Machine Learning-Based Decoders

5.2.1. Neural Network Architectures

- Input layer: 2D syndrome array (binary or probabilistic values)

- Convolutional layers: – 3×3 and 5×5 filters to capture local error correlations – Multiple feature maps (typically 16-64 channels) – ReLU activation functions

- Pooling layers: Max pooling to reduce dimensionality while preserving features

- Fully connected layers: Dense layers for final classification

- Output layer: Separate predictions for X and Z corrections (multi-output)

- Dataset generation: Create (E, S, C) training triplets • E: Random error patterns according to noise model • S: Corresponding syndrome measurements • C: Optimal correction (from MWPM or enumeration)

- Loss function: Multi-class cross-entropy:

- 3.

- Optimization: Adam optimizer with learning rate scheduling

- 4.

- Regularization: Dropout and batch normalization to prevent overfitting

- Thresholds: 0.8-1.0% for surface codes (vs. 1.1% for MWPM)

- Inference time: <1 μs on modern GPUs for d = 5 codes

- Correlated noise: Superior performance compared to classical decoders

- Adaptability: Can learn and adapt to changing noise characteristics [61]

- Permutation invariance: Natural handling of qubit relabeling

- Scalability: Can generalize across different code sizes

- Code flexibility: Handle irregular LDPC and other non-uniform codes

- Interpretability: Learned messages relate to classical belief propagation

- Inductive bias: Built-in understanding of local error propagation [62]

5.2.2. Reinforcement Learning Approaches

- State space: S = {0, 1}^{n-k} (syndrome configurations)

- Action space: A = set of possible Pauli corrections

- Reward function: R(s, a) = {+1 if correction successful (no logical error) {-1 if logical error remains (7)

- Policy: π(a|s) gives probability of selecting correction a for syndrome s

- Deep Q-Networks (DQN): Learn action-value function Q(s, a) using neural networks

- Policy Gradient Methods: Directly optimize policy parameters using REINFORCE

- Actor-Critic: Combine value function learning with direct policy optimization

- Multi-Agent RL: Distributed decoding with multiple cooperating agents [63]

- Real-time adaptation to changing noise models

- Online learning from actual quantum hardware

- Handling of unknown error correlations

- Self-improvement through continued operation

- Training instability and slow convergence

- Sample efficiency concerns for practical deployment

- Exploration vs. exploitation trade-offs in critical applications

- Limited interpretability compared to classical algorithms

5.2.3. Hybrid Classical-ML Approaches

- Use neural networks to predict edge weights for matching graph

- Learn noise correlations not captured by i.i.d. models

- Maintain optimality guarantees while improving empirical performance

- Particularly effective for handling measurement errors and crosstalk [64]

- Combine multiple decoder outputs through learned weighting

- Classical decoders provide baseline performance and reliability

- ML components handle complex correlations and adaptation

- Confidence-based switching between classical and ML decoders

5.3. Real-Time Decoding Requirements and Hardware Implementation

5.3.1. Platform-Specific Timing Requirements

| Platform | Syndrome Cycle | Coherence Time | Decoder Latency | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting | 1-2 μs | 50-100 μs | <0.5 μs | >2 MHz |

| Trapped Ion | 10-50 μs | >1 ms | <10 μs | >100 kHz |

| Neutral Atom | 1-10 μs | 100 μs - 1 ms | <1 μs | >1 MHz |

| Photonic | 1-10 ns | N/A | <100 ns | >10 GHz |

| Silicon Quantum Dot | 1-10 μs | 1-10 ms | <1 μs | >1 MHz |

5.3.2. Hardware Acceleration Strategies

- Union-Find optimizations: – Parallel cluster operations across syndrome regions – Custom data structures optimized for union-find operations – Pipeline architecture overlapping growth and merge phases – Demonstrated <500 ns latency for d = 5 surface codes

- Memory optimization: – On-chip block RAM for syndrome storage and processing – Minimize external memory access through data locality – Custom caching strategies for frequently accessed patterns

-

Scalability: – Modular design enabling parallel processing of multiple code patches – Network-on-chip for inter-module communication – Load balancing across processing elements [65]GPU Acceleration: Graphics Processing Units excel at ML decoder inference:

- Parallel syndrome processing: – Process hundreds of syndrome patterns simultaneously – Batch inference for improved GPU utilization – Tensor operations optimized for neural network computations

- Memory hierarchy optimization: – Shared memory for frequently accessed model parameters – Coalesced memory access patterns for optimal bandwidth – Model quantization to reduce memory footprint

-

Performance achievements: – >10,000 syndrome decodings per second for d = 7 surface codes – <100 μs latency including data transfer overhead – Support for batch processing multiple quantum processors [66]Custom ASIC Development: Application-Specific Integrated Circuits for ultimate performance:

- Specialized datapaths: Hardware optimized for specific decoder algorithms

- Low-latency design: Direct integration with quantum control electronics

- Power efficiency: Critical for large-scale cryogenic deployment

- Scalable architecture: Support for multiple code instances and distances

- Industry development: Companies like Riverlane developing dedicated QEC chips [67]

6. Engineering Challenges and Practical Considerations

6.1. Correlated Noise and Realistic Error Models

6.1.1. Sources and Characterization of Error Correlations

- ZZ coupling: Always-on interactions causing correlated dephasing: H_crosstalk = ∑_{⟨i,j⟩} ζ_ij/2 Z_i ⊗ Z_j (8) where ζ_ij ranges from 1-100 kHz depending on qubit separation

- Spectator errors: Operations on target qubits inducing phase shifts on nearby idle qubits

- Frequency crowding: Unwanted resonances when qubit frequencies drift within ∼10 MHz

- Control line coupling: Shared microwave delivery causing simultaneous over/under-rotations

- Magnetic field fluctuations: Common-mode dephasing across millimeter-scale chip regions

- Temperature variations: Thermal gradients causing correlated frequency drifts

- Vibrations: Mechanical perturbations creating spatially correlated errors

- Cosmic ray events: High-energy particles affecting multiple qubits simultaneously

- 1/f noise: Low-frequency charge and flux noise with long correlation times [68]

- Readout crosstalk: Dispersive shifts affecting neighboring qubit frequencies during measurement

- State preparation errors: Imperfect ancilla initialization creating systematic syndrome biases

- Simultaneous measurement effects: Shared readout resonators coupling measurement processes

6.1.2. Quantitative Error Characterization

| Platform | 1Q Gate Error | 2Q Gate Error | Readout Error | Idle Error | Correlation Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting | 0.05-0.1% | 0.2-1.0% | 1-5% | 0.01-0.1% | 1-5 qubits |

| Trapped Ion | 0.01-0.05% | 0.1-0.5% | 0.5-2% | 0.001-0.01% | Chain-wide |

| Neutral Atom | 0.1-0.5% | 0.5-2% | 1-5% | 0.01-0.1% | Local clusters |

| Silicon QD | 0.01-0.1% | 0.1-1% | 0.5-2% | 0.1-1% | Nearest neighbors |

| Photonic | N/A | 1-10% | 5-20% | 0% | Optical network |

6.1.3. Advanced Characterization Techniques

- Apply random Clifford sequences to all qubits simultaneously

- Measure average fidelity decay as function of sequence length

- Extract both individual qubit errors and correlation terms

- Identify dominant crosstalk mechanisms and spatial patterns

- Gate Set Tomography (GST): Complete characterization of gate operations

- Cycle benchmarking: Direct measurement of QEC cycle fidelity

- Syndrome correlation analysis: Statistical analysis of syndrome pattern correlations

- Machine learning characterization: Neural networks trained to identify error patterns [69]

6.1.4. Error Mitigation and Suppression Strategies

- Dynamical decoupling: Pulse sequences to suppress crosstalk during idle periods: U_DD = ∏_k e^{-iH_k t_k} such that ⟨H_crosstalk⟩_DD ≈ 0 (9)

- Optimal frequency allocation: Computational optimization of qubit frequencies to minimize interactions

- Engineered pulse shaping: Derivative-based optimization (DRAG, GRAPE) to reduce spectator errors

- Layout optimization: Physical qubit placement minimizing problematic couplings [70]

- Tailored stabilizer codes: Codes optimized for specific error correlation patterns

- Adaptive syndrome scheduling: Measurement ordering optimized to break temporal correlations

- Flagged stabilizer codes: Additional ancillas to detect measurement errors and correlations

- Subsystem codes: Gauge degrees of freedom to accommodate correlated errors [71]

6.2. Cryogenic Control and System Integration

6.2.1. Control System Architecture Challenges

| System Scale | Logical Qubits | Physical Qubits | Control Lines | Data Rate (GB/s) | Power (kW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Demo | 1 | 50 | 200 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Near-term | 10 | 500 | 2,000 | 10 | 1 |

| Medium Scale | 50 | 5,000 | 20,000 | 100 | 10 |

| Large Scale | 100 | 10,000 | 40,000 | 200 | 20 |

| Fault-Tolerant | 1,000 | 100,000 | 400,000 | 2,000 | 200 |

| Full Scale | 10,000 | 1,000,000 | 4,000,000 | 20,000 | 2000 |

- Frequency-domain multiplexing: Multiple control signals on single physical lines

- Cryogenic electronics: Classical processing at 4K to reduce thermal load and latency

- Integrated photonics: On-chip optical control and readout systems

- Wireless control: RF/microwave links to reduce wiring complexity

- Distributed control: Modular processors with local control systems [67]

6.2.2. Thermal Management and Cryogenic Engineering

- Microwave electronics: ∼1 mW per qubit at mixing chamber level

- DC bias lines: ∼0.1 mW per line due to Johnson noise filtering

- Digital control: ∼10 μW per qubit for cryogenic CMOS

- Readout amplification: ∼1 mW per readout channel

- Total budget: Typical dilution refrigerators provide ∼10 mW at 10 mK

- Multi-stage cooling: Distributed heat sinking across temperature levels

- Pulse-tube refrigerators: Closed-cycle systems for continuous operation

- Advanced materials: Superconducting and high-thermal-conductivity interconnects

- Active thermal management: Temperature control and gradient minimization

6.2.3. Integration with Classical Computing Infrastructure

- Low-latency communication: Classical feedback within syndrome extraction cycles

- High-bandwidth data transfer: Streaming syndrome data to classical processors

- Synchronization: Precise timing coordination across quantum and classical systems

- Reliability: Fault-tolerant classical systems to match quantum reliability requirements

- Edge computing: Decoding processors co-located with quantum hardware

- Cloud integration: High-level control and algorithm execution in cloud infrastructure

- Hybrid architectures: Hierarchical processing with local real-time control and remote optimization

- Network protocols: Specialized communication protocols for quantum control networks [72]

6.3. Noise Characterization and Adaptive Methods

6.3.1. Real-Time Noise Tracking

- Process drift monitoring: Continuous tracking of gate fidelity changes

- Syndrome pattern analysis: Statistical analysis of error correlation evolution

- Predictive modeling: Machine learning models for noise prediction and preemptive correction

- Adaptive calibration: Automatic parameter optimization based on performance metrics [73]

- Decoder parameter updates: Real-time adjustment of decoding thresholds and weights

- Code switching: Dynamic selection of optimal codes for current noise conditions

- Resource reallocation: Adaptive logical qubit placement and routing

- Predictive error correction: Preemptive error correction based on noise forecasting

7. Resource Estimation for Quantum Applications

7.1. Cryptographic Applications

7.1.1. Shor’s Algorithm for Integer Factorization

- Logical qubits: 2n + 3 for the main computation registers

- Arithmetic operations: O(n³) controlled modular multiplications

- Circuit depth: O(n³) logical gate operations

- T-gates: O(n³) non-Clifford operations requiring magic state distillation

| RSA Bits | Logical Qubits | T-gates | Physical Qubits | Runtime | Success Prob. | Cost (M$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1024 | 2048 | 1.2 × 10⁷ | 4.8 × 10⁶ | 4.8 hours | 99% | 150 |

| 2048 | 4096 | 9.6 × 10⁷ | 2.0 × 10⁷ | 1.6 days | 99% | 600 |

| 3072 | 6144 | 3.2 × 10⁸ | 4.1 × 10⁷ | 3.7 days | 99% | 1,200 |

| 4096 | 8192 | 7.7 × 10⁸ | 6.8 × 10⁷ | 6.4 days | 99% | 2,000 |

- RSA-1024: Vulnerable to quantum attacks within 5-7 years of fault-tolerant systems

- RSA-2048: Current standard, requires substantial quantum resources but achievable by 2030

- ECC-256: Elliptic curve cryptography offers better classical security but similar quantum vulnerability

- Migration timeline: NIST recommends post-quantum cryptography adoption by 2030 [74]

7.1.2. Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem

| ECC Bits | Security Level | Logical Qubits | Physical Qubits | Runtime |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 256 | RSA-3072 equivalent | 1280 | 2.1 × 10⁶ | 8.2 hours |

| 384 | RSA-7680 equivalent | 1920 | 3.6 × 10⁶ | 20.1 hours |

| 521 | RSA-15360 equivalent | 2605 | 5.8 × 10⁶ | 1.9 days |

7.2. Quantum Chemistry and Materials Science

7.2.1. Molecular Electronic Structure Calculations

- Logical qubits: 2M (spin-up and spin-down orbitals)

- Hamiltonian terms: O(M⁴) two-electron integrals

- Circuit depth: O(M⁵) for full configuration interaction

- Measurement overhead: O(M⁴) expectation values

| Molecule | Orbitals | Logical Qubits | Physical Qubits | Runtime | Scientific Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂ (Hydrogen) | 4 | 8 | 800 | 1 min | Benchmark |

| LiH (Lithium Hydride) | 12 | 24 | 2,400 | 30 min | Battery materials |

| BeH₂ (Beryllium Hydride) | 16 | 32 | 3,200 | 2 hours | Catalysis |

| N₂ (Nitrogen) | 28 | 56 | 5,600 | 8 hours | Nitrogen fixation |

| Fe₂S₂ (Iron-Sulfur) | 76 | 152 | 15,200 | 3 days | Enzyme modeling |

| P450 Active Site | 100 | 200 | 20,000 | 1 week | Drug metabolism |

| Ferrocene (Fe(C₅H₅)₂) | 140 | 280 | 28,000 | 2 weeks | Organometallics |

- Catalyst design: Improved catalysts for chemical industry could save billions in energy costs

- Drug discovery: Accurate protein-drug interaction modeling accelerating pharmaceutical development

- Materials science: Design of new materials for batteries, solar cells, and superconductors

- Environmental applications: Better understanding of atmospheric chemistry and pollution remediation

7.2.2. Advanced Algorithms and Error Budgets

- Gate count reduction: Factor of 10-100 improvement over naive implementations

- Error budget optimization: Adaptive precision for different calculation stages

- Parallel processing: Distributed quantum chemistry calculations across multiple processors

- VQE with error correction: Variational algorithms enhanced with logical qubits

- Classical preprocessing: Reduce quantum circuit depth through classical optimization

- Error mitigation integration: Combine QEC with quantum error mitigation techniques [36]

7.3. Optimization and Machine Learning

7.3.1. Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA)

| Problem Type | Variables | Logical Qubits | Circuit Depth | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max-Cut | 100 | 100 | 10³ | Network optimization |

| Portfolio Optimization | 500 | 500 | 10⁴ | Financial services |

| Vehicle Routing | 1000 | 1000 | 10⁴ | Logistics |

| Drug Discovery | 2000 | 2000 | 10⁵ | Pharmaceutical |

| Supply Chain | 5000 | 5000 | 10⁵ | Manufacturing |

| Traffic Flow | 10000 | 10000 | 10⁶ | Urban planning |

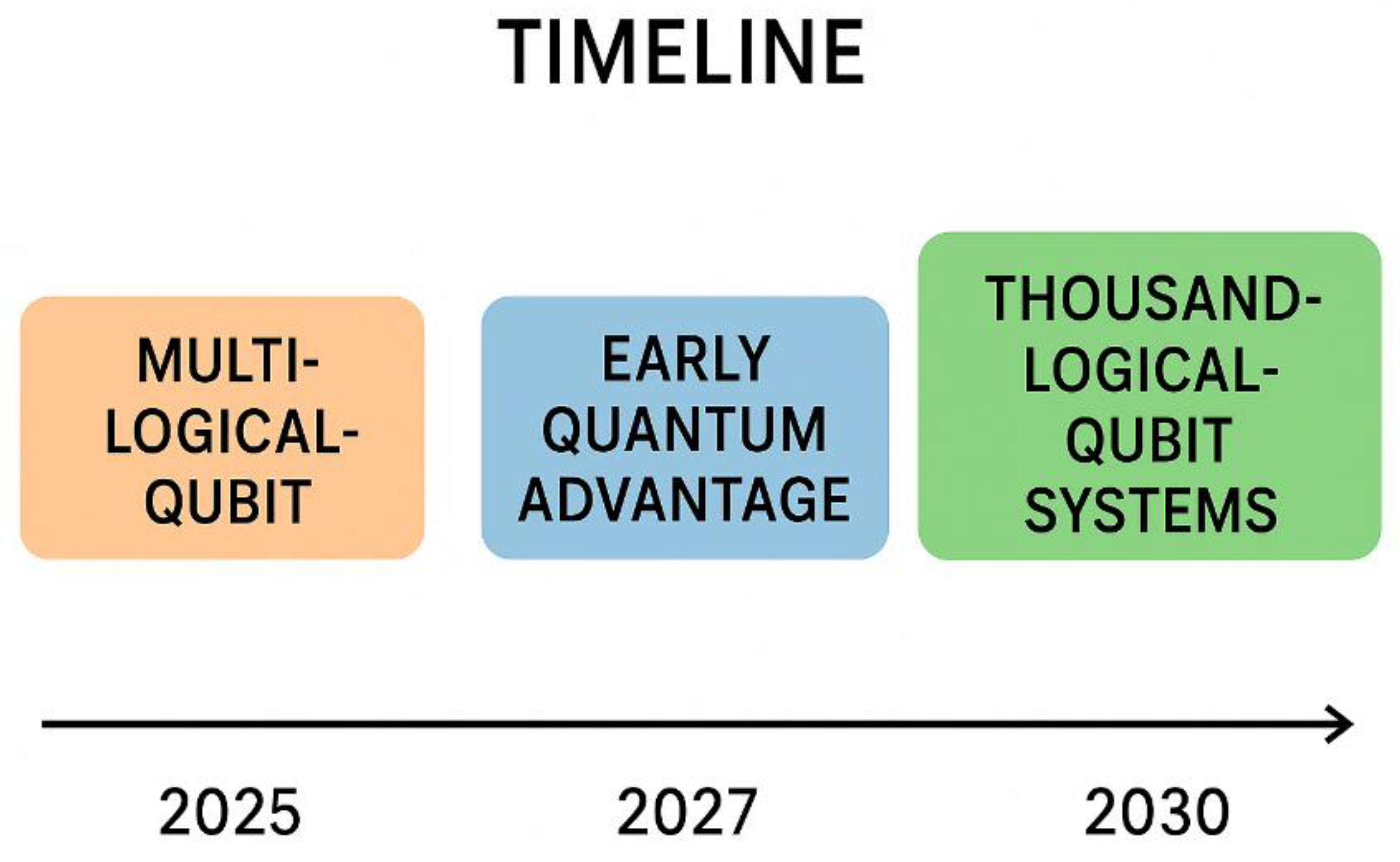

- 2025-2027: Small optimization problems with 50-100 variables

- 2028-2030: Medium-scale problems competing with classical heuristics

- 2030+: Large-scale problems beyond classical computational reach

7.3.2. Quantum Machine Learning Applications

- Training data: N data points in d dimensions

- Quantum advantage: Exponential speedup in feature space dimension

- Resource requirements: O(log(Nd)) logical qubits

- Error sensitivity: High precision requirements for kernel computations

- Parameterized quantum circuits: Trainable quantum layers

- Gradient computation: Fault-tolerant parameter-shift rules

- Hybrid architectures: Classical-quantum neural network combinations

- Applications: Natural language processing, image recognition, financial modeling [75]

8. Industry Roadmaps and Strategic Development

8.1. Leading Industry Players

8.1.1. Google Quantum AI

- Platform focus: Superconducting qubits with surface code error correction

- Architecture: Modular approach with interconnected surface code patches

- Control systems: Custom classical electronics and cryogenic integration

- Software stack: Cirq quantum programming framework with error correction integration

| Year | Milestone | Logical Qubits | Key Capability | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | Below-threshold QEC | 1 | Proof of principle | ✓ Achieved |

| 2023 | Improved thresholds | 5 | Better error rates | ✓ Achieved |

| 2024 | Multi-patch codes | 10 | Logical connectivity | In progress |

| 2025 | Small applications | 50 | Chemistry benchmarks | Target |

| 2027 | Medium-scale systems | 200 | Optimization advantage | Target |

| 2030 | Large-scale FTQC | 1000 | Commercial applications | Goal |

- R&D spending: $500M+ annually on quantum computing research

- Fabrication facilities: Custom superconducting qubit fabrication capabilities

- Talent acquisition: 200+ quantum researchers and engineers

- Industry partnerships: Collaborations with automotive, pharmaceutical, and finance sectors [76]

8.1.2. IBM Quantum Network

- Modular architecture: Multiple quantum processors connected via classical and quantum links

- Distributed computing: Workload distribution across quantum and classical resources

- Software integration: Qiskit framework with enterprise-grade tools

- Cloud deployment: Quantum computing as a service (QCaaS) model

| Year | Processor | Physical Qubits | Error Rates | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | Heron | 133 | 99.9% 2Q fidelity | Improved coherence |

| 2024 | Flamingo | 156 | 99.95% 2Q fidelity | Error correction ready |

| 2025 | Next-Gen | 200 | 99.97% 2Q fidelity | Logical qubit demos |

| 2026 | Modular-1 | 400 | 99.98% 2Q fidelity | Multi-chip systems |

| 2028 | Modular-10 | 4000 | 99.99% 2Q fidelity | Fault-tolerant apps |

| 2030 | Enterprise | 10000+ | >99.99% 2Q fidelity | Commercial advantage |

- Enterprise partnerships: 200+ companies in quantum network

- Industry verticals: Finance, automotive, energy, healthcare focus

- Education initiatives: Quantum education programs and certification

- Open source: Contributions to quantum software ecosystem [77]

8.1.3. Microsoft Azure Quantum

- Majorana fermions: Intrinsic topological protection from noise

- Theoretical advantage: Potentially higher thresholds and simpler error correction

- Technical challenges: Experimental realization remains difficult

- Partnerships: Collaboration with academic institutions and hardware providers

- Hardware agnostic: Support for multiple quantum hardware platforms

- Classical integration: Seamless hybrid classical-quantum computing

- Q# programming: Domain-specific language for quantum algorithms

- Cloud services: Scalable quantum computing infrastructure [78]

8.1.4. Quantinuum (Honeywell + Cambridge Quantum Computing)

- High fidelity: >99.9% gate fidelities reducing QEC overhead

- All-to-all connectivity: Flexible qubit interactions enabling diverse codes

- Long coherence: Minutes-long coherence times for complex algorithms

- Precise control: Individual qubit addressing and measurement

| System | Qubits | Gate Fidelity | QEC Capability | Target Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1-1 | 20 | 99.91% | Small codes | QEC demonstrations |

| H1-2 | 32 | 99.92% | Steane codes | Algorithm development |

| H2-1 | 56 | 99.9% | Surface codes | Chemistry applications |

| H3 (planned) | 100 | 99.95% | LDPC codes | Optimization problems |

| H4 (target) | 200 | 99.97% | Fault-tolerant | Commercial applications |

- Quantum chemistry: Specialized algorithms for molecular simulation

- Machine learning: Quantum advantage in pattern recognition and optimization

- Cryptography: Post-quantum cryptography development and quantum key distribution

- Enterprise solutions: Industry-specific quantum applications [79]

8.2. Emerging Companies and Alternative Approaches

8.2.1. Neutral Atom Platforms

- Scaling advantage: Demonstrated 1180-atom systems

- Reconfigurable connectivity: Optical tweezer manipulation

- Target applications: Optimization and machine learning problems

- Timeline: 100-logical-qubit systems by 2026 [48]

- Analog quantum computing: Direct Hamiltonian simulation

- Harvard collaboration: Academic research partnerships

- Specialized applications: Materials science and condensed matter physics

- Hybrid approach: Combining analog and digital quantum computing [49]

8.2.2. Photonic Quantum Computing

- Million-qubit vision: Large-scale photonic systems

- Fault-tolerant from day one: Focus on error-corrected systems

- Silicon photonics: Leveraging semiconductor manufacturing

- Timeline: Fault-tolerant systems by 2027-2030 [80]

- Continuous variable: Gaussian boson sampling and CV quantum computing

- Cloud access: PennyLane quantum software platform

- Near-term applications: Optimization and machine learning

- Research focus: Quantum advantage demonstrations [81]

8.3. Investment Trends and Market Analysis

8.3.1. Funding and Valuation Trends

- Government funding: National quantum initiatives totaling >$25B globally

- Private investment: Venture capital and corporate investment >$10B since 2020

- Strategic partnerships: Industry collaborations driving application development

- Talent acquisition: Competition for quantum scientists and engineers [82]

| Company | Valuation ($B) | Total Funding ($M) | Employees | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google Quantum AI | N/A (Internal) | >1000 | 200+ | Superconducting |

| IBM Quantum | N/A (Public) | >500 | 150+ | Superconducting |

| Quantinuum | 5.0 | 625 | 400+ | Trapped Ion |

| IonQ | 2.0 | 200 | 100+ | Trapped Ion |

| Rigetti | 1.5 | 200 | 150+ | Superconducting |

| PsiQuantum | 3.2 | 665 | 200+ | Photonic |

| Atom Computing | 0.6 | 60 | 50+ | Neutral Atom |

| Xanadu | 0.4 | 100 | 80+ | Photonic |

8.3.2. Market Size Projections

- 2024: $1.3B (mostly R&D and early applications)

- 2027: $5B (first commercial applications)

- 2030: $15B (fault-tolerant applications emerging)

- 2035: $50B+ (widespread commercial adoption)

- Financial services: $4B (portfolio optimization, risk analysis)

- Pharmaceuticals: $3B (drug discovery, molecular modeling)

- Chemicals/Materials: $2.5B (catalyst design, materials discovery)

- Cybersecurity: $2B (post-quantum cryptography, quantum key distribution)

- Logistics: $1.5B (optimization, supply chain)

- Energy: $1B (grid optimization, battery materials)

- Others: $1B (manufacturing, AI, research) [83]

9. Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing Architectures

9.1. Complete System Integration

9.1.1. Hierarchical System Architecture

- Quantum hardware: Qubits, gates, measurements, and control systems

- Classical control: Real-time feedback and synchronization systems

- Cryogenic infrastructure: Cooling systems and thermal management

- Networking: Quantum and classical communication between processors

- Syndrome extraction: Stabilizer measurement circuits and scheduling

- Classical decoding: Real-time error correction algorithms

- Logical operations: Fault-tolerant implementation of quantum gates

- Resource management: Allocation of physical qubits to logical functions

- Logical qubit management: State preparation, manipulation, and measurement

- Gate synthesis: Decomposition of logical operations into fault-tolerant circuits

- Error budgeting: Optimal allocation of error tolerance across algorithm stages

- Code selection: Dynamic choice of error correction codes for different operations

- Quantum algorithms: High-level algorithm implementation and optimization

- Classical preprocessing: Problem decomposition and parameter optimization

- Hybrid execution: Coordination between quantum and classical computation

- Result verification: Validation and error detection in algorithm outputs

9.1.2. Distributed Quantum Computing

- Star networks: Central hub connecting multiple quantum processors

- Mesh networks: Direct connections between neighboring processors

- Hierarchical networks: Multiple levels of quantum and classical processing

- Hybrid architectures: Combining local and remote quantum resources

- Quantum teleportation: State transfer between distant processors

- Distributed entanglement: Creating and maintaining entanglement across networks

- Error correction networking: Network-wide error correction protocols

- Latency management: Coordinating time-sensitive quantum operations [84]

9.2. Software Stack Development

9.2.1. Quantum Operating Systems

- Qubit allocation: Dynamic assignment of physical qubits to logical functions

- Circuit scheduling: Optimal timing of quantum operations

- Error budget management: Tracking and optimizing error accumulation

- Multi-tenancy: Supporting multiple concurrent quantum applications

- Calibration management: Automated system calibration and drift correction

- Error monitoring: Real-time tracking of system performance metrics

- Fault recovery: Automatic handling of hardware failures and errors

- Performance optimization: Dynamic tuning of system parameters

9.2.2. Programming Languages and Compilers

- Q# (Microsoft): Domain-specific language with error correction support

- Cirq (Google): Python framework for fault-tolerant circuit design

- Qiskit (IBM): Comprehensive quantum computing platform

- PennyLane (Xanadu): Quantum machine learning and optimization focus

- Error-aware optimization: Circuit optimization considering error correction overhead

- Resource allocation: Mapping logical operations to available physical resources

- Code selection: Automatic choice of optimal error correction codes

- Hardware abstraction: Portable code across different quantum platforms [85]

10. Future Perspectives and Research Directions

10.1. Theoretical Challenges and Open Problems

10.1.1. Fundamental Limitations and Trade-Offs

- Universal thresholds: Do threshold theorems hold for all physically reasonable noise models?

- Finite-size effects: How do thresholds behave for realistic finite-size quantum computers?

- Time-correlated noise: Can threshold theorems be extended to non-Markovian noise processes?

-

Measurement-dependent noise: How do measurement errors affect threshold calculations?Resource-Performance Trade-offs: Fundamental questions about optimal resource allocation:

- Code rate vs. threshold: Is there a fundamental trade-off between code efficiency and error tolerance?

- Space-time trade-offs: Can temporal error correction reduce spatial overhead?

- Energy-error trade-offs: How do thermodynamic constraints affect error correction efficiency?

- Communication-computation trade-offs: What are optimal architectures for distributed quantum computing?

10.1.2. Advanced Error Correction Concepts

- 4D topological codes: Higher-dimensional codes with better properties

- Thermal stability: Systems that maintain quantum information at finite temperature

- Active matter approaches: Using driven dissipative systems for protection

- Emergent error correction: Quantum many-body systems with built-in protection [86]

- Autonomous error correction: Systems that correct errors through designed evolution

- Reservoir engineering: Using engineered environments for error suppression

- Quantum error correction codes: Purely quantum approaches without classical feedback

- Continuous monitoring: Real-time error correction without discrete measurements

10.2. Emerging Technologies and Platforms

10.2.1. Novel Qubit Modalities

- Majorana fermions: Zero-dimensional topological superconductors

- Parafermions: Fractional quantum Hall systems with enhanced protection

- Fibonacci anyons: Non-Abelian anyons enabling universal quantum computation

- Challenges: Experimental realization remains difficult despite theoretical promise [87]

- Metal complexes: Transition metal ions with controllable spin states

- Molecular magnets: Single-molecule magnets with long coherence times

- Nuclear spins: Hyperfine interactions for precise control

- Advantages: Chemical tunability and potential for scalable synthesis [88]

- Superconducting-spin hybrids: Coupling superconducting circuits to spin systems

- Optomechanical systems: Using mechanical resonators as quantum intermediates

- Atomic-photonic interfaces: Atoms coupled to integrated photonic circuits

- Advantages: Leveraging strengths of different platforms while mitigating weaknesses

10.2.2. Advanced Integration Technologies

- Vertical integration: Stacking quantum and classical processing layers

- 3D connectivity: Improved qubit interactions and reduced routing overhead

- Thermal management: Better heat dissipation in 3D structures

- Manufacturing challenges: Complex 3D fabrication processes [89]

- Same-chip integration: Quantum and classical circuits on single substrate

- Cryogenic classical: Classical electronics operating at quantum temperatures

- Real-time communication: Ultra-low-latency quantum-classical interfaces

- Shared resources: Common control and measurement infrastructure

10.3. Algorithmic Advances and Applications

10.3.1. Next-Generation Quantum Algorithms

- Error-corrected VQE: Variational quantum eigensolver with logical qubits

- Adaptive quantum computing: Real-time algorithm adaptation based on intermediate results

- Quantum approximate optimization: QAOA with error correction for larger problem sizes

- Hybrid approaches: Seamless integration of classical optimization and quantum computation

- Quantum neural networks: Deep quantum circuits for pattern recognition

- Quantum kernel methods: Exponentially large feature spaces for classification

- Quantum generative models: Quantum GANs and variational autoencoders

- Federated quantum learning: Distributed quantum machine learning protocols [90]

10.3.2. Cross-Disciplinary Applications

- Climate modeling: Large-scale atmospheric and oceanic simulations

- Astrophysics: Simulating black holes, neutron stars, and early universe

- High-energy physics: Lattice QCD and fundamental particle interactions

- Condensed matter: Many-body quantum systems and phase transitions

- Protein folding: Accurate modeling of protein structure and dynamics

- Drug discovery: Quantum chemistry for pharmaceutical design

- Biosystem modeling: Understanding quantum effects in biological processes

- Medical imaging: Quantum-enhanced MRI and other imaging modalities [91]

10.4. Societal Impact and Policy Considerations

10.4.1. Economic Implications

| Sector | Early Impact | Significant Disruption | Market Size ($B) | Quantum Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Services | 2025-2027 | 2028-2030 | 50 | Portfolio optimization |

| Pharmaceuticals | 2026-2028 | 2030-2032 | 80 | Drug discovery |

| Chemical Industry | 2027-2029 | 2031-2033 | 40 | Catalyst design |

| Cybersecurity | 2025-2026 | 2027-2029 | 30 | Cryptography |

| Automotive | 2028-2030 | 2032-2035 | 25 | Materials, batteries |

| Energy | 2029-2031 | 2033-2036 | 35 | Grid optimization |

| Logistics | 2027-2029 | 2030-2032 | 20 | Supply chain |

- Job displacement: Potential automation of certain computational tasks

- New industries: Emerging quantum technology sectors and services

- Competitive advantage: Early adopters gaining significant market advantages

- Infrastructure investment: Massive capital requirements for quantum systems

10.4.2. Security and Policy Implications

- Y2Q problem: “Years to Quantum” countdown for cryptographic vulnerability

- Data harvesting: Current encrypted data vulnerable to future quantum attacks

- Infrastructure updates: Massive upgrade requirements for security systems

- International coordination: Need for global standards and protocols [74]

- Quantum advantage: Strategic implications of quantum computational superiority

- Technology export controls: Restrictions on quantum technology transfer

- Critical infrastructure: Protecting quantum systems from adversarial attacks

- International cooperation: Balancing collaboration with security concerns

10.4.3. Ethical and Social Considerations

- Digital divide: Ensuring broad access to quantum computing benefits

- Educational requirements: Training workforce for quantum technology

- International development: Supporting quantum capability in developing nations

- Cost considerations: Making quantum computing accessible beyond elite institutions

- Enhanced surveillance: Quantum computing enabling new monitoring capabilities

- Privacy protection: Quantum cryptography for enhanced privacy

- Regulatory frameworks: Need for updated privacy and data protection laws

- Democratic oversight: Ensuring quantum capabilities serve public interest

11. Recommendations and Strategic Priorities

11.1. Research Community Priorities

11.1.1. Fundamental Research Directions

- Realistic noise characterization: Develop comprehensive models for correlated and time-dependent errors

- Decoder optimization: Create hardware-efficient decoders for real-time operation

- Code adaptation: Design codes optimized for specific hardware platforms and noise models

- System integration: Develop complete fault-tolerant quantum computing stacks

- Scalable architectures: Design quantum systems with thousands of logical qubits

- Application-specific optimization: Tailor error correction for specific quantum algorithms

- Hybrid classical-quantum systems: Optimize the quantum-classical interface

- Distributed quantum computing: Develop protocols for networked quantum systems

- Self-correcting systems: Achieve autonomous error correction without external intervention

- Universal quantum computers: Build general-purpose fault-tolerant quantum machines

- Quantum internet: Create global quantum communication networks

- Novel error correction paradigms: Explore fundamentally new approaches to quantum error protection

11.1.2. Collaborative Research Initiatives

- Quantum error correction standards: Develop common benchmarks and protocols

- Shared research infrastructure: Create globally accessible quantum computing facilities

- Student and researcher exchange: Foster international collaboration and knowledge transfer

- Open source initiatives: Support collaborative software development efforts

- Joint research programs: Combine academic research with industrial development

- Technology transfer: Accelerate movement of research results to commercial applications

- Workforce development: Train next generation of quantum engineers and scientists

- Problem-driven research: Focus academic research on industrially relevant challenges

11.2. Industry Strategy Recommendations

11.2.1. Technology Development Priorities

- Focus on fidelity: Prioritize gate fidelity improvements over qubit count increases

- Error characterization: Invest in comprehensive noise modeling and mitigation

- Modular architectures: Design systems for scalable expansion and maintenance

- Control system integration: Develop efficient quantum-classical interfaces

- Full-stack development: Create comprehensive quantum software platforms

- Error correction integration: Build error correction into programming languages and compilers

- Application frameworks: Develop domain-specific quantum computing tools

- Cloud services: Provide accessible quantum computing infrastructure

- Early engagement: Begin quantum computing education and pilot projects now

- Problem identification: Identify specific use cases where quantum advantage is achievable

- Partnership development: Collaborate with quantum computing companies and researchers

- Infrastructure planning: Prepare IT infrastructure for quantum-classical hybrid computing

11.2.2. Investment and Business Strategy

- Long-term perspective: Quantum computing requires sustained investment over decades

- Diversified portfolio: Invest across different quantum computing approaches and applications

- Talent acquisition: Companies with strong technical teams show better long-term prospects

- Intellectual property: Strong patent portfolios provide competitive advantages

- Build vs. buy decisions: Evaluate internal development vs. partnership strategies

- Talent development: Invest in quantum education and workforce development

- Risk management: Prepare for quantum threats to current business models

- Market positioning: Establish leadership positions in quantum-relevant market segments

11.3. Policy and Governance Recommendations

11.3.1. Government Policy Priorities

- Sustained investment: Maintain long-term funding commitments for quantum research

- Interdisciplinary focus: Support research connecting quantum computing with other fields

- International collaboration: Fund collaborative research programs with allies

- Risk-tolerant funding: Support high-risk, high-reward research projects

- Technology standards: Develop standards for quantum computing systems and protocols

- Export controls: Balance security concerns with international collaboration needs

- Privacy protection: Update privacy laws for quantum computing era

- Economic policy: Consider economic implications of quantum disruption

11.3.2. International Coordination

- Quantum technology partnerships: Establish international quantum research consortiums

- Standards development: Create global standards for quantum computing and communications

- Ethics guidelines: Develop international guidelines for responsible quantum technology development

- Capacity building: Support quantum technology development in emerging economies

12. Conclusions

12.1. Key Findings and Achievements

12.2. Critical Challenges and Limitations

12.3. Timeline and Expectations

- Small-scale fault-tolerant systems with 10-100 logical qubits

- Demonstration of quantum algorithms on logical qubits

- First applications showing potential quantum advantage in specialized problems

- Medium-scale systems with 100-1000 logical qubits

- Commercial applications in optimization, chemistry, and machine learning

- Cost reductions making quantum computing accessible to more organizations

- Large-scale fault-tolerant systems with 1000+ logical qubits

- Clear quantum advantages in multiple application domains

- Integration of quantum computing into enterprise and scientific workflows

- Ubiquitous quantum computing infrastructure

- Quantum computers as essential tools for scientific and industrial applications

- New discoveries enabled by large-scale quantum simulation and computation

12.4. Strategic Implications

12.5. Recommendations for the Community

- Collaborative Research: Foster increased collaboration between theoretical researchers, experimental physicists, and engineers to accelerate the development of practical fault-tolerant systems.

- Realistic Benchmarking: Develop comprehensive benchmarks that account for realistic noise models, finite-size effects, and practical implementation constraints.

- Workforce Development: Invest significantly in education and training programs to develop the specialized workforce required for quantum technology development and deployment.

- Responsible Innovation: Engage proactively with policymakers, ethicists, and society to ensure that quantum computing development serves the broader public interest.

- International Cooperation: Maintain open scientific collaboration while addressing legitimate security concerns, ensuring that the benefits of quantum computing are broadly shared.

12.6. Final Perspective

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shor, P.W. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings 35th annual symposium on foundations of computer science; IEEE: 1994; pp. 124–134.

- Grover, L.K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proceedings of the twenty-eighth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing; 1996; pp. 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Preskill, J. Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, P.W. Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory. Physical review A 1995, 52, R2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steane, A.M. Error correcting codes in quantum theory. Physical Review Letters 1996, 77, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, D. Stabilizer codes and quantum error correction. arXiv preprint quant-ph/9705052 1997.

- Kitaev, A.Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Annals of physics 2003, 303, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.; Kitaev, A.; Landahl, A.; Preskill, J. Topological quantum memory. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2002, 43, 4452–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arute, F.; et al. Exponential suppression of bit or phase errors with repetitive error correction. Nature 2021, 595, 383–387. [Google Scholar]

- Krinner, S.; et al. Realizing repeated quantum error correction in a distance-three surface code. Nature 2022, 605, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, M.M. Quantum information theory; Cambridge University Press: 2013.

- Renes, J.M.; Dupuis, F.; Renner, R. Efficient quantum polar codes. Physical review letters 2012, 109, 050504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarovar, M.; et al. Detecting crosstalk errors in quantum information processors. Quantum 2020, 4, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallman, J.J.; Emerson, J. Noise tailoring for scalable quantum computation via randomized compiling. Physical Review A 2016, 94, 052325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, J.; Fowler, A.G.; Geller, M.R. Surface code with decoherence: An analysis of three superconducting architectures. Physical Review A 2013, 88, 062329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, M.; et al. Removing leakage-induced correlated errors in superconducting quantum error correction. Nature communications 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panos, K.; et al. Bias-preserving gates with stabilized cat qubits. Science Advances 2022, 8, eabm9901. [Google Scholar]

- Renes, J.M. Belief propagation decoding of quantum channels by passing quantum messages. New Journal of Physics 2022, 24, 032001. [Google Scholar]

- Krastanov, S.; Heywood, V.V.; Jacobs, K. Optimally adaptive quantum error correction of surface codes. Physical Review Research 2022, 4, 043203. [Google Scholar]

- Aharonov, D.; Ben-Or, M. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant error rate. SIAM Journal on Computing 2008, 38, 1207–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, A.G.; Mariantoni, M.; Martinis, J.M.; Cleland, A.N. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Physical Review A 2012, 86, 032324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landahl, A.J.; Anderson, J.T.; Rice, P.R. Fault-tolerant quantum computing with color codes. arXiv preprint 2011, arXiv:1108.5738. [Google Scholar]

- Breuckmann, N.P.; Eberhardt, J.N. Quantum low-density parity-check codes. PRX Quantum 2021, 2, 040101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliferis, P.; Gottesman, D.; Preskill, J. Quantum accuracy threshold for concatenated distance-3 codes. Quantum Information Computation 2006, 6, 97–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D. Operator quantum error-correcting subsystems for self-correcting quantum memories. Physical Review A 2006, 73, 012340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, Y.; Svore, K.M. Low-distance surface codes under realistic quantum noise. Physical Review A 2014, 90, 062320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombín, H.; Martin-Delgado, M.A. Optimal resources for topological two-dimensional stabilizer codes: Comparative study. Physical Review A 2007, 76, 012305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastin, B.; Knill, E. Restrictions on transversal encoded quantum gate sets. Physical review letters 2009, 102, 110502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravyi, S.; Kitaev, A. Universal quantum computation with ideal Clifford gates and noisy ancillas. Physical Review A 2005, 71, 022316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haah, J.; Hastings, M.B. Codes and protocols for distilling T, controlled-S, and Toffoli gates. Quantum 2018, 2, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsman, C.; Fowler, A.G.; Devitt, S.; Van Meter, R. Surface code quantum computing by lattice surgery. New Journal of Physics 2012, 14, 123011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, R.; et al. Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit. arXiv preprint, 2022; arXiv:2207.06431. [Google Scholar]

- Google Quantum, AI. Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. arXiv preprint 2023, arXiv:2301.04112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetta, J.M.; et al. IBM’s roadmap for scaling quantum technology. IBM Journal of Research and Development 2020, 64, 13–1. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, C.K.; et al. Repeated quantum error detection in a surface code. Nature Physics 2020, 16, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, S.; Cai, Z.; Benjamin, S.C.; Yuan, X. Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms and quantum error mitigation. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 2021, 90, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, C.; et al. Programmable quantum simulations of spin systems with trapped ions. Reviews of Modern Physics 2021, 93, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; et al. Exponential suppression of bit or phase flip errors with repetitive error correction. Nature 2021, 595, 383–387. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, D.J. Engineering the quantum-classical interface of solid-state qubits. npj Quantum Information 2015, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandala, A.; et al. Error mitigation extends the computational reach of a noisy quantum processor. Nature 2019, 567, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quantinuum Team. Quantum error correction with the color code. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2201.07806.

- Sivak, V.V.; et al. Real-time quantum error correction beyond break-even. Nature 2022, 616, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postler, L.; et al. Demonstration of fault-tolerant universal quantum gate operations. Nature 2022, 605, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Quantum Team. Azure Quantum development kit and Q# language. Available online: https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/products/quantum (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- IonQ Inc. Algorithmic applications with error correction. Available online: https://ionq.com/resources (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Alpine Quantum Technologies. AQT quantum computing systems. Available online: https://www.aqt.eu/ (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Ebadi, S.; et al. Quantum phases of matter on a 256-atom programmable quantum simulator. Nature 2021, 595, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atom Computing Inc. Neutral atom quantum computing platform. Available online: https://atom-computing.com/technology (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- QuEra Computing Inc. Analog quantum processing units. Available online: https://www.quera.com/technology (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Bluvstein, D.; et al. A quantum processor based on coherent transport of entangled atom arrays. Nature 2022, 604, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, D.; Kitaev, A.; Preskill, J. Encoding a qubit in an oscillator. Physical Review A 2001, 64, 012310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, M.; et al. Non-Clifford and parallelizable fault-tolerant logical gates on constant and almost-constant rate homological quantum LDPC codes via higher symmetries. arXiv preprint 2023, arXiv:2310.16982. [Google Scholar]

- Raussendorf, R.; Harrington, J. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with high threshold in two dimensions. Physical Review Letters 2007, 98, 190504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliferis, P.; Cross, A.W. Subsystem fault tolerance with the Bacon-Shor code. Physical Review Letters 2007, 98, 220502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raussendorf, R.; Harrington, J.; Goyal, K. A fault-tolerant one-way quantum computer. Annals of Physics 2006, 321, 2242–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverrier, A.; Zémor, G. Quantum Tanner codes. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2202.13641. [Google Scholar]

- Breuckmann, N.P.; Eberhardt, J.N. Balanced product quantum codes. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2021, 67, 6653–6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteleev, P.; Kalachev, G. Asymptotically good quantum and locally testable classical LDPC codes. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2111.03654. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, A.G. Minimum weight perfect matching of fault-tolerant topological quantum error correction in average O(1) parallel time. Quantum Information and Computation 2015, 15, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfosse, N.; Nickerson, N.H. Almost-linear time decoding algorithm for topological codes. Quantum 2021, 5, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varona, N.; Müller-Lennert, M. Determination of the semion code threshold using neural network decoders. Physical Review A 2018, 98, 042337. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Neural belief-propagation decoders for quantum error-correcting codes. Physical Review Letters 2022, 129, 050502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasson, P.; et al. Quantum error correction for the toric code using deep reinforcement learning. Quantum 2019, 3, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgott, O.; Gidney, C. Sparse Blossom: correcting a million errors per core second with minimum-weight matching. arXiv preprint 2023, arXiv:2303.15933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Pattison, C.A.; Manne, S.; Carmean, D.; Svore, K.; Chong, F.T.; Chamberland, C. A scalable FPGA-based decoder for fault-tolerant quantum error correction. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2205.09063. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, T.; Hermann, H.; Ribeiro, P.; Zilberberg, O. Efficient quantum error correction with neural-network decoders. arXiv preprint 2022, arXiv:2201.09271. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, D.J. Engineering the quantum-classical interface of solid-state qubits. npj Quantum Information 2015, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, M.; et al. Removing leakage-induced correlated errors in superconducting quantum error correction. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helsen, J.; et al. General framework for randomized benchmarking. PRX Quantum 2022, 3, 020357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rol, M.A.; et al. Restless tuneup of high-fidelity qubit gates. Physical Review Applied 2020, 14, 044017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberland, C.; Zhu, G.; Yoder, T.J.; Hertzberg, J.B.; Cross, A.W. Topological and subsystem codes on low-degree graphs with flag qubits. Physical Review X 2020, 10, 011022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, C.; et al. Programmable quantum simulations of spin systems with trapped ions. Reviews of Modern Physics 2021, 93, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, N.M.; et al. Machine learning for active quantum error correction. Physical Review Research 2022, 4, 043141. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/Projects/post-quantum-cryptography (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Biamonte, J.; et al. Quantum machine learning. Nature 2017, 549, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Quantum, AI. Google’s quantum computing roadmap. Available online: https://quantumai.google/roadmap (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- IBM Research. IBM Quantum Network roadmap. Available online: https://research.ibm.com/quantum/roadmap (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Microsoft Quantum. Microsoft’s approach to quantum computing. Available online: https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/products/quantum (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Quantinuum. Quantinuum roadmap and strategy. Available online: https://www.quantinuum.com/roadmap (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- PsiQuantum Corp. Million-qubit quantum computer roadmap. Available online: https://psiquantum.com/roadmap (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Xanadu Quantum Technologies. Photonic quantum computing platform. Available online: https://xanadu.ai/products (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- McKinsey & Company. Quantum computing funding remains strong, but talent gap widening. McKinsey Technology Trends Outlook 2023.

- Boston Consulting Group. The Coming Quantum Leap in Computing. BCG Technology Report 2023.

- Kimble, H.J. The quantum internet. Nature 2008, 453, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi-Abhari, A.; et al. Quantum computing with Qiskit. arXiv preprint 2021, arXiv:2105.01280. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B.J.; Loss, D.; Pachos, J.K.; Self, C.N.; Wootton, J.R. Quantum memories at finite temperature. Reviews of Modern Physics 2016, 88, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, C.; Simon, S.H.; Stern, A.; Freedman, M.; Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Reviews of Modern Physics 2008, 80, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessoli, R.; Powell, A.K. Strategies towards single molecule magnets based on lanthanide ions. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2009, 253, 2328–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, S. The challenge of scaling quantum computers. Nature Reviews Physics 2022, 4, 549–550. [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo, M.; et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; et al. Quantum chemistry in the age of quantum computing. Chemical Reviews 2019, 119, 10856–10915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).