Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

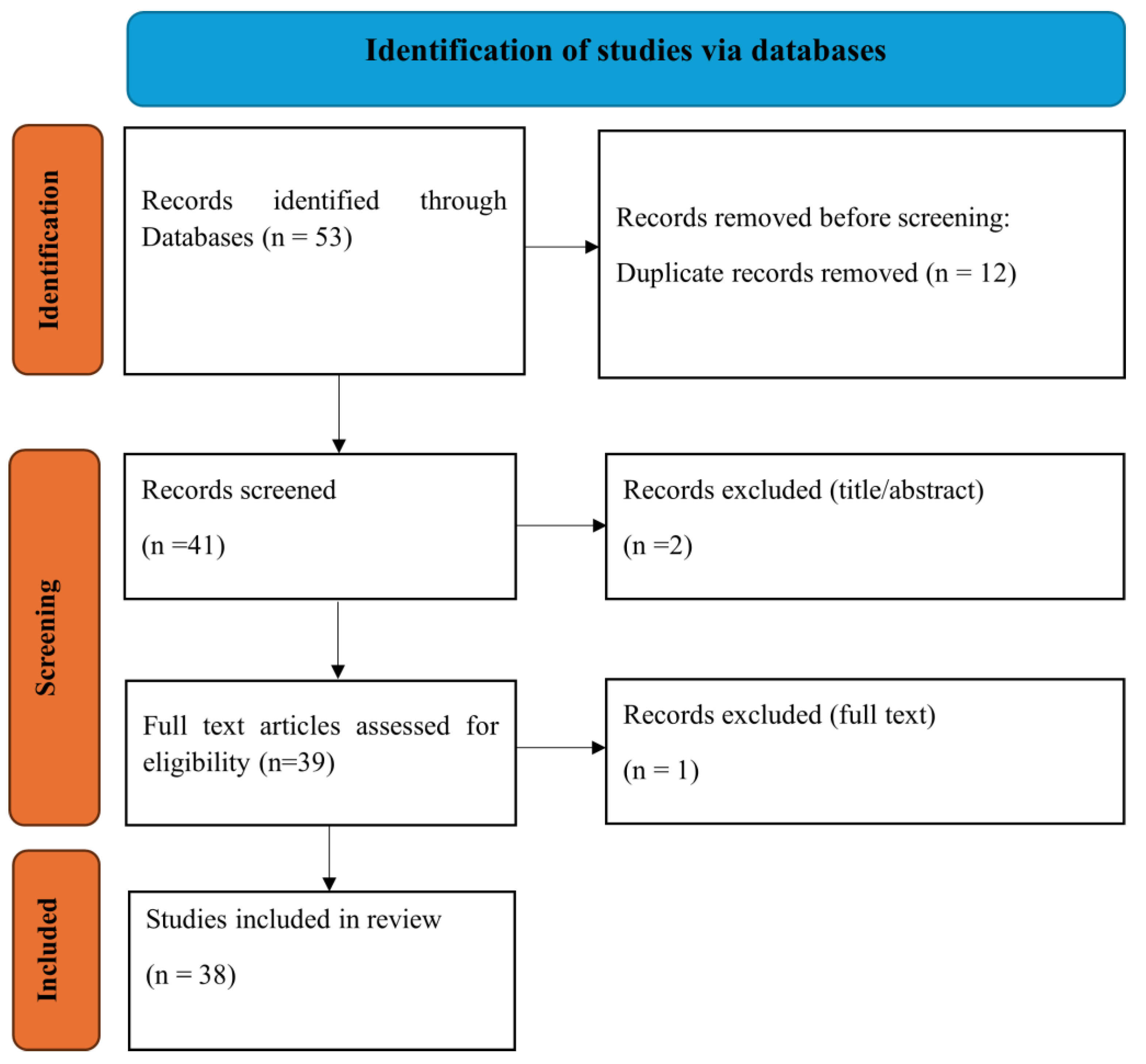

2. Methodology

2.1. Database Selection and Search Strategy

2.2. Screening and Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- It proposes or applies MPC (or a variant such as nonlinear, robust, adaptive, or stochastic MPC).

- The context’s application is clearly within autonomous or connected autonomous vehicles.

- The primary or secondary control objective includes safety-related concerns, such as collision avoidance, risk minimization, or safety-constrained planning.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria and Final Selection

- The focus was only on energy efficiency, passenger comfort, or fuel economy, without any explicit safety-related control formulation.

- The study applied MPC in domains outside of AVs.

- The work was non-peer-reviewed (e.g., technical reports, theses, or preprints without peer review).

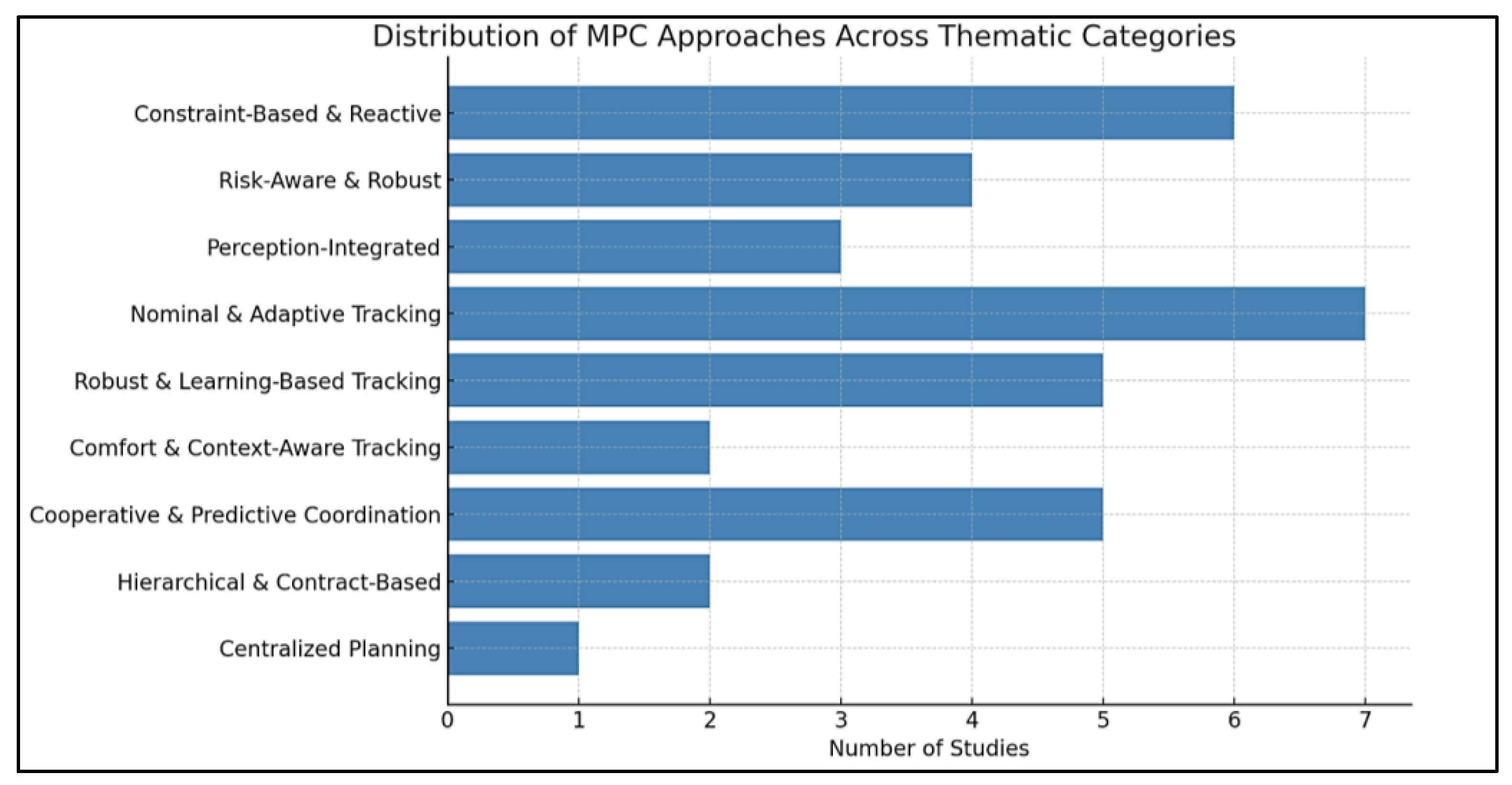

2.3. Thematic Classification and Overlap of Included Studies

- Collision Avoidance and Risk Mitigation: It focuses on obstacle detection, emergency maneuvers, and planning under risk or uncertainty.

- Trajectory Tracking and Path Following: It addresses accurate adherence to reference paths or waypoints under dynamic constraints, disturbances, or comfort objectives.

- Intersection and Coordination Tasks: It involves multi-agent planning for lane changes, merging, intersection handling, or platoon-level cooperation.

3. Thematic Synthesis of Literature

3.1. Collision Avoidance and Risk Mitigation

3.1.1. Constraint-Based and Reactive Collision Avoidance

3.1.2. Risk-Aware and Robust Control under Uncertainty

3.1.3. Perception-Aware and Learning-Augmented Safety Architectures

3.2. Trajectory Tracking and Path Following

3.2.1. Nominal and Adaptive MPC for Tracking

3.2.2. Robust and Learning-Enhanced Tracking under Uncertainty

3.2.3. Comfort-Integrated and Context-Aware Trajectory Control

3.3. Intersection and Coordination Tasks

3.3.1. Cooperative and Predictive Maneuvering

3.3.2. Hierarchical and Contract-Based Control

3.3.3. Centralized and Mission-Level Planning

4. Cross-Cutting Challenges in MPC-Based Safety Control

4.1. Challenges in Collision Avoidance and Risk Mitigation

- Oversimplified obstacle modeling: Numerous studies (e.g., [1,5]) assume deterministic obstacle behavior or rely on predefined trajectories, which restricts their applicability in complex, dynamic environments. Moreover, interactions with human-driven vehicles or pedestrians are frequently neglected.

- Constraint encoding difficulties: Methods like artificial potential fields (APFs) [6] and time-varying safety margins often face challenges in non-convex or high-speed scenarios, resulting in local minima or infeasible constrained maneuvers.

- Handling of uncertainty: Although some studies use robust or reachability-based methods (e.g., [15]), formal guarantees under significant uncertainty, particularly with moving obstacles or stochastic intent models, are uncommon. Probabilistic and learning-based approaches to uncertainty quantification remain largely underexplored.

- Limited cooperative awareness: Most MPC formulations take an ego-centric approach and do not explicitly consider shared environments or multi-agent interactions, which can undermine safety in mixed-autonomy traffic.

4.2. Challenges in Trajectory Tracking and Path Following

- Limited safety guarantees in learning-based methods: Techniques employing Gaussian Processes or neural models (e.g., [25,36]) enhance adaptability but often lack formal guarantees for safety, stability, or convergence. Integration with fallback controllers or verifiable safety monitors is rarely addressed.

- Comfort treated as secondary: While studies like [34] incorporate comfort metrics such as jerk and yaw rate, comfort is generally handled as a separate optimization objective rather than being fully integrated with safety, tracking, or constraint satisfaction.

4.3. Challenges in Intersection and Coordination Tasks

5. Future Research Directions

5.1. Risk-Sensitive and Adaptive Collision Avoidance

- Hybrid robust–learning MPC frameworks: These should combine formal guarantees, like reachability analysis or control barrier functions, with real-time uncertainty modeling using methods such as Gaussian Processes or Bayesian filters.

- Anytime MPC solvers: Designed for emergency situations, these solvers should provide suboptimal yet feasible evasive actions within tight computational limits.

- Context-aware obstacle reasoning: Incorporating semantic perception, such as object type and behavior prediction, to dynamically adjust the MPC cost function or safety constraints.

- Multi-agent evasion strategies: Cooperative collision avoidance leverages shared situational awareness and anticipates the interactive maneuvers of surrounding agents.

5.2. Robust, Transparent, and Comfort-Aware Trajectory Tracking

- Integrated comfort–safety formulations: These should penalize jerk, yaw rate, or lateral acceleration while still enforcing strict tracking and obstacle avoidance constraints.

- Certified learning-enhanced MPC: Data-driven models like Gaussian Processes or neural networks should be verified using barrier certificates, Lyapunov functions, or reachability analysis to guarantee safety and convergence.

- Multi-timescale adaptive MPC: Capable of adjusting model fidelity and prediction detail according to factors like road type, speed, or situational complexity.

- Data-driven personalization: Allowing tuning of tracking behavior based on vehicle characteristics or user preferences to enhance human-machine interaction and ride comfort.

5.3. Scalable and Integrated Coordination Architectures

- Distributed and event-triggered multi-agent MPC: Designed with provable guarantees on feasibility, stability, and convergence, even under asynchronous or lossy communication channels.

- Mixed-autonomy-aware coordination: Taking into account the unpredictable behaviors of human-driven vehicles interacting with cooperative autonomous vehicles in shared environments.

- Contract-based and hierarchical co-optimization: Combining high-level route or mission planning with low-level constraint enforcement across diverse agents.

- Unified coordination and tracking stacks: Jointly optimizing safety, efficiency, and comfort using shared prediction models and interoperable planning layers.

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Ammour, R. Orjuela, and M. Basset, “A MPC Combined Decision Making and Trajectory Planning for Autonomous Vehicle Collision Avoidance,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 24805–24817, 2022. [CrossRef]

- 2. J. Wang, S. Gong, S. Peeta, and L. Lu, “A real-time deployable model predictive control-based cooperative platooning approach for connected and autonomous vehicles,” Transp. Res. Part B Methodol., vol. 128, pp. 271–301, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Arrigoni et al., “Autonomous vehicle controlled by safety path planner with collision risk estimation coupled with a non-linear MPC,” DYNAMICS OF VEHICLES ON ROADS AND TRACKS, no. 24th Symposium of the International-Association-for-Vehicle-System-Dynamics (IAVSD). pp. 199–208, 2016.

- D. Phan et al., “Cascade Adaptive MPC with Type 2 Fuzzy System for Safety and Energy Management in Autonomous Vehicles: A Sustainable Approach for Future of Transportation,” SUSTAINABILITY, vol. 13, no. 18, 2021. [CrossRef]

- 5. M. Ammour, R. Orjuela, and M. Basset, “Collision avoidance for autonomous vehicle using MPC and time varying Sigmoid safety constraints,” IFAC PAPERSONLINE, vol. 54, no. 6th IFAC Conference on Engine Powertrain Control, Simulation and Modeling (E-COSM). pp. 39–44, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Yang, Y. Q. He, Y. Xu, and H. Zhao, “Collision Avoidance for Autonomous Vehicles Based on MPC With Adaptive APF,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1559–1570, 2024. [CrossRef]

- 7. D. Dong, H. T. Ye, W. G. Luo, J. Y. Wen, and D. Huang, “Collision Avoidance Path Planning and Tracking Control for Autonomous Vehicles Based on Model Predictive Control,” SENSORS, vol. 24, no. 16, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Ibrahim, M. Kögel, C. Kallies, and R. Findeisen, “Contract-based Hierarchical Model Predictive Control and Planning for Autonomous Vehicle,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 15758–15764, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. T. Hung and A. M. Pascoal, “Cooperative Path Following of Autonomous Vehicles with Model Predictive Control and Event Triggered Communications⁎⁎This research was supported in part by the Marine UA project under the Marie Curie Sklodowska grant agreement No 642153, the H2020 EU Marin,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 51, no. 20, pp. 562–567, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Song and K. Huh, “Driving and steering collision avoidance system of autonomous vehicle with model predictive control based on non-convex optimization,” Adv. Mech. Eng., vol. 13, no. 6, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S.-L. Lin and B.-C. Lin, “Enhancing Safety in Autonomous Vehicle Navigation: An Optimized Path Planning Approach Leveraging Model Predictive Control,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 80, no. 3, pp. 3555–3572, 2024. [CrossRef]

- 12. J. R. Wang, Y. B. Guo, Q. F. Wang, J. Gao, Y. M. Chen, and IEEE, “Event-triggered MPC for Collision Avoidance of Autonomous Vehicles Considering Trajectory Tracking Performance,” in 2022 International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM), 2022, pp. 514–520. [CrossRef]

- 13. H. Chen, Q. Liu, D. Sun, S. Yu, and H. Chen, “Fast Model Predictive Control Trajectory Tracking for Autonomous Vehicles Based on BFGS Interior Point Method,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 58, no. 29, pp. 433–438, 2024. [CrossRef]

- 14. S. Yu, B. Chen, I. M. Jaimoukha, and S. A. Evangelou, “Game-Theoretic Model Predictive Control for Safety-Assured Autonomous Vehicle Overtaking in Mixed-Autonomy Environment,” in 2024 European Control Conference (ECC), 2024, pp. 3728–3733. [CrossRef]

- 15. T. Z. Fu, H. H. Nguyen, R. Findeisen, and IEEE, “Guaranteed Collision Avoidance for Autonomous Vehicles Fusing Model Predictive Control and Data Driven Reachability Analysis,” in 2024 EUROPEAN CONTROL CONFERENCE, ECC 2024, 2024, pp. 2286–2291. [CrossRef]

- 16. M. Ibrahim, J. Matschek, B. Morabito, and R. Findeisen, “Hierarchical Model Predictive Control for Autonomous Vehicle Area Coverage,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 52, no. 12, pp. 79–84, 2019. [CrossRef]

- 17. L. Xiong, M. Liu, X. Yang, B. Leng, and IEEE, “Integrated Path Tracking for Autonomous Vehicle Collision Avoidance Based on Model Predictive Control With Multi-constraints,” 2022 IEEE 25TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS (ITSC), no. IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). pp. 554–561, 2022. [CrossRef]

- 18. C. Ko, S. Han, M. Choi, and K.-S. Kim, “Integrated Path Planning and Tracking Control of Autonomous Vehicle for Collision Avoidance based on Model Predictive Control and Potential Field,” in 2020 20th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), 2020, pp. 956–961. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, J. Qin, S. Tan, and H. Luo, “Lane change trajectory planning based on improved model predictive control with artificial potential field for autonomous vehicles in medium-high speed scenarios,” Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell., vol. 150, p. 110601, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Cheng, L. Li, H. Q. Guo, Z. G. Chen, and P. Song, “Longitudinal Collision Avoidance and Lateral Stability Adaptive Control System Based on MPC of Autonomous Vehicles,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 2376–2385, 2020. [CrossRef]

- 21. J. Nan, Z. Ge, X. Ye, A. F. Burke, and J. Zhao, “Model predictive control for autonomous vehicle path tracking through optimized kinematics,” Results Eng., vol. 24, p. 103123, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- 22. Y. Mizushima, I. Okawa, and K. Nonaka, “Model Predictive Control for Autonomous Vehicles with Speed Profile Shaping,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 52, no. 8, pp. 31–36, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Mihály, Z. Farkas, and P. Gáspár, “Model Predictive Control for the Coordination of Autonomous Vehicles at Intersections,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 15174–15179, 2020. [CrossRef]

- 24. N. Awad, A. Lasheen, M. Elnaggar, and A. Kamel, “Model predictive control with fuzzy logic switching for path tracking of autonomous vehicles,” ISA Trans., vol. 129, pp. 193–205, 2022. [CrossRef]

- 25. J. Bethge, M. Pfefferkorn, A. Rose, J. Peters, and R. Findeisen, “Model Predictive Control with Gaussian-Process-Supported Dynamical Constraints for Autonomous Vehicles,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 507–512, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiang, Z. Man, K. Xia, Y. Wu, Y. Wang, and Z. Yao, “Model predictive control–based cooperative lane-changing strategy for connected autonomous vehicle platoons merging into dedicated lanes,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 278, p. 127274, 2025. [CrossRef]

- 27. X. Sun, Y. Cai, S. Wang, X. Xu, and L. Chen, “Optimal control of intelligent vehicle longitudinal dynamics via hybrid model predictive control,” Rob. Auton. Syst., vol. 112, pp. 190–200, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Elsisi, “Optimal design of adaptive model predictive control based on improved GWO for autonomous vehicle considering system vision uncertainty,” Appl. Soft Comput., vol. 158, p. 111581, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen and X. Zhang, “Path Planning for Intelligent Vehicle Collision Avoidance of Dynamic Pedestrian Using Att-LSTM, MSFM, and MPC at Unsignalized Crosswalk,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 4285–4295, 2022. [CrossRef]

- 30. M. N. Nikkhah, A. Khastavan, and A. Nahvi, “Nonlinear Model Predictive Control for High-Speed Collision Avoidance in Autonomous Vehicles,” in 2023 11th RSI International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (ICRoM), IEEE, Dec. 2023, pp. 769–775. [CrossRef]

- 31. B. Zarrouki, J. Nunes, and J. Betz, “R2NMPC_ A Real-Time Reduced Robustified Nonlinear Model Predictive Control with Ellipsoidal Uncertainty Sets for Autonomous Vehicle Motion Control,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 58, no. 18, pp. 309–316, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. T. Hung, N. Crasta, D. Moreno-Salinas, A. M. Pascoal, and T. A. Johansen, “Range-based target localization and pursuit with autonomous vehicles: An approach using posterior CRLB and model predictive control,” Rob. Auton. Syst., vol. 132, p. 103608, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhao, H. Wei, Q. Ai, N. Zheng, C. Lin, and Y. Zhang, “Real-time model predictive control of path-following for autonomous vehicles towards model mismatch and uncertainty,” Control Eng. Pract., vol. 153, p. 106126, 2024. [CrossRef]

- 34. C. Philippe, L. Adouane, B. Thuilot, A. Tsourdos, and H.-S. Shin, “Safe and Online MPC for Managing Safety and Comfort of Autonomous Vehicles in Urban Environment,” in 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 2018, pp. 300–306. [CrossRef]

- B. Škugor et al., “Safety Manifold for Stochastic Model Predictive Control of an Autonomous Vehicle Approaching Unsignalized Crosswalks with Pedestrians,” in 2024 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SMART SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGIES, SST, E. Nyarko, T. Matic, R. Cupec, and M. Vranjes, Eds., 2024, pp. 279–285. [CrossRef]

- C. Hu, Y. Xie, L. Xie, and M. Magno, “Sparse Gaussian process-based strategies for two-layer model predictive control in autonomous vehicle drifting,” Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol., vol. 174, p. 105065, 2025. [CrossRef]

- 37. M. Soliman, B. Morabito, and R. Findeisen, “Towards Safe Exploration for Autonomous Vehicles using Dual Model Predictive Control,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 55, no. 27, pp. 387–392, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, Z. Liu, Z. Zuo, Z. Li, L. Wang, and X. Luo, “Trajectory Planning and Safety Assessment of Autonomous Vehicles Based on Motion Prediction and Model Predictive Control,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 68, no. 9, pp. 8546–8556, 2019. [CrossRef]

- 39. D. Shen, Y. Chen, L. Li, and J. Hu, “Trajectory Tracking for Autonomous Vehicles Using Robust Model Predictive Control,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 58, no. 10, pp. 94–101, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Collision Avoidance | Trajectory Tracking | Coordination | Ref. | Collision Avoidance | Trajectory Tracking | Coordination |

| [1] | ✓ | [2] | ✓ | ||||

| [3] | ✓ | [4] | Excluded | ||||

| [5] | ✓ | [6] | ✓ | ||||

| [7] | ✓ | [8] | ✓ | ||||

| [9] | ✓ | ✓ | [10] | ✓ | |||

| [11] | ✓ | [12] | ✓ | ||||

| [13] | ✓ | [14] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [15] | ✓ | ✓ | [16] | ✓ | |||

| [17] | ✓ | [18] | ✓ | ||||

| [19] [19] | ✓ | [20] | ✓ | ||||

| [21] | ✓ | [22] | ✓ | ||||

| [23] | ✓ | [24] | ✓ | ||||

| [25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [26] | ✓ | ||

| [27] | ✓ | [28] | ✓ | ||||

| [29] | ✓ | [30] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [31] | ✓ | [32] | ✓ | ||||

| [33] | ✓ | [34] | ✓ | ||||

| [35] | ✓ | [36] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [37] | ✓ | [38] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| [39] | ✓ | ||||||

| Approach | Technique / Method | Representative References | Control Objective |

| Constraint-Based and Reactive | Sigmoid/APF Safety Barriers | [5,6,18,19] | Geometric repulsion to enforce obstacle clearance |

| Time-Varying Obstacle Margins | [19] | Dynamic scaling of safety zones relative to obstacle motion | |

| Nonlinear MPC (NMPC) | [3,30] | Execute evasive actions under realistic vehicle dynamics | |

| Hard Safety Constraints | [1,10] | Enforce vehicle-boundary constraints in local maneuvering | |

| Risk-Aware and Robust Control | Monte Carlo Risk Estimation | [38] | Evaluate probability of collision across candidate paths |

| Reachability-Based MPC | [15] | Maintain invariant safe sets under bounded uncertainty | |

| Robust MPC (RMPC) | [14,35] | Guarantee safety under model mismatch and stochastic uncertainty | |

| Adaptive MPC | [17,36] | Adjust control model online based on environmental or system changes | |

| Perception-Enhanced Architectures | Pedestrian-Aware MPC (DL-based) | [29] | Forecast pedestrian intent for proactive avoidance |

| Game-Theoretic MPC | [14] | Predict and respond to other agents’ strategies in shared environments | |

| Dual-Layer MPC | [37] | Combine nominal control with independent safety override | |

| GP-Enhanced MPC | [25] | Learn residual dynamics for improved safety prediction | |

| Event-Triggered Collision Coordination | [9] | Manage collisions through decentralized planning under sparse communication |

| Approach | Technique / Method | Representative References | Control Objective |

| Nominal and Adaptive MPC | Linear/Nonlinear MPC | [11,12,13,20,22,30] | Real-time path tracking under nominal and nonlinear dynamics |

| Adaptive and Hybrid MPC | [27,28] | Adapt to changing dynamics, sensor noise, or system modes | |

| NMPC for Vehicle-Following | [7,21] | Maintain relative distance and track curvature in platooning scenarios | |

| Robust and Learning-Enhanced | Robust MPC (RMPC, LPV) | [31,33,39] | Maintain tracking under disturbances and parameter variation |

| Gaussian Process-Enhanced MPC | [25,36] | Compensate modeling error through learning-based residual correction | |

| Comfort and Context-Aware | Comfort-Aware MPC | [34] | Improve passenger comfort by minimizing jerk and yaw rate |

| Fuzzy Logic-Based Context Switching | [24] | Adapt tracking behavior to environmental or operational context | |

| Long-Range and Smooth Path Tracking | [32] | Improve stability and prediction for extended horizons |

| Approach | Technique / Method | Representative References | Control Objective |

| Cooperative and Predictive Maneuvering | Cooperative MPC (C-MPC) | [2,26] | Synchronized lane changes and merging via trajectory sharing |

| Event-Triggered Coordination | [9] | Minimize communication by triggering only on significant deviation | |

| Game-Theoretic and Reachability MPC | [14,15] | Ensure safety in multi-agent environments through behavior prediction | |

| Hierarchical and Contract-Based Control | Hierarchical MPC for Intersection | [23] | Separate scheduling and control for scalable coordination |

| Contract-Based Hierarchical MPC | [8] | Ensure compatibility between planner and controller via constraint negotiation | |

| Centralized and Mission-Level Planning | Centralized multi-Agent MPC | [16] | Allocate and coordinate multi-vehicle tasks under a unified planning framework |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).