Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Microbiome

Foundation of the Gut-Organ Axes

Modern Microbiome Disruption & Associated Human Health

Landscape of Biotic Innovation

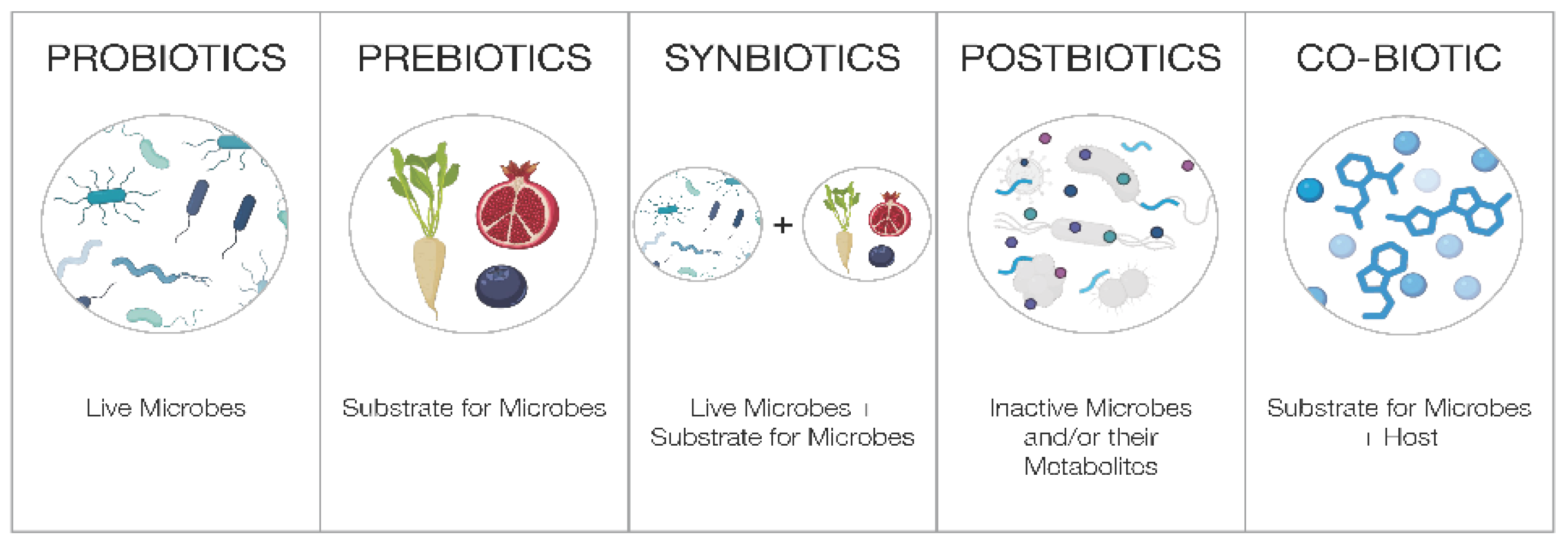

- Probiotics are defined as “Live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.” [48]. Supplements that use probiotic ingredients for a health benefit must be formulated at a clinically relevant dose, with well-documented strains, delivered to ensure the appropriate viability of the strains at the end of shelf life. The majority of probiotics are intended for the intestinal tract, supporting gut and digestive health, with a few documented to have systemic effects working along the gut-organ axes. Of note, fermented foods are not probiotics and they have a separate definition [49].

- Prebiotics are defined as “A substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit.” [50]. While prebiotics are commonly believed to be only fiber, this is not the case as prebiotic substances can be non-fiber, such as polyphenols, and certain types of oligosaccharides that are selectively metabolized. As with probiotics, prebiotics should be formulated at clinically studied doses for its intended effects. Unfortunately, the terms prebiotic and probiotic are widely misused, leading to incorrect perceptions that foods like onions, cereals, or garlic are prebiotic (without defining the compound, its amount and the dosage needed to confer a health benefit), and that for example any Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium strain is a probiotic (without performing appropriate clinical studies to prove the strain’s efficacy and competitiveness).

- Synbiotics are defined as “A mixture comprising of live microorganisms and substrate(s) selectively utilized by host microorganisms that confers a health benefit on the host.” [51]. Synbiotics may be complementary, where the prebiotic ingredients are not targeting the co-administered probiotic strains, or synergistic, where the prebiotics are selectively utilized by the co-administered probiotic. The benefit of synbiotics, especially synergistic synbiotics, is that it promotes the survival of the bacterial strain that feeds on the prebiotic substrate in the host, and the health benefits of both ingredients may be amplified.

- Lastly, postbiotics are defined as “A preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host.” [52]. Recently, the International Probiotic Association (IPA) led a global effort to standardize the commercial definition of postbiotics, and further classified postbiotics into four distinct subcategories: (1) complex non-viable microbial preparations (CX; inactive microbial cells/fractions in unpurified culture medium), (2) intact non-viable microbial cells (IC; inactive whole microbial cells, separated from culture medium), (3) fragmented microbial cells (FC; fragmented microbial cells, separated from culture medium), and (4) microbial metabolic products (MM; metabolic products of microbial cells within their unpurified or partially purified culture medium) [53]. The global acceptance of the definition and these four subcategories remains to be achieved. While purified microbial metabolites have been purposely excluded by both ISAPP and IPA in their published definitions of postbiotics, many believe that they are also important considerations in this category. Nevertheless, postbiotics provide manufacturing benefits over probiotics since they do not contain viable microbial cells. However, they must still be clinically validated and show health benefits on the intended host. Interestingly, postbiotics do not have to be derived from a clinically validated probiotic strain, so long as the postbiotic preparation has a proven health benefit.

Co-Biotics

A New Category of Biotics

Co-Biotic Examples

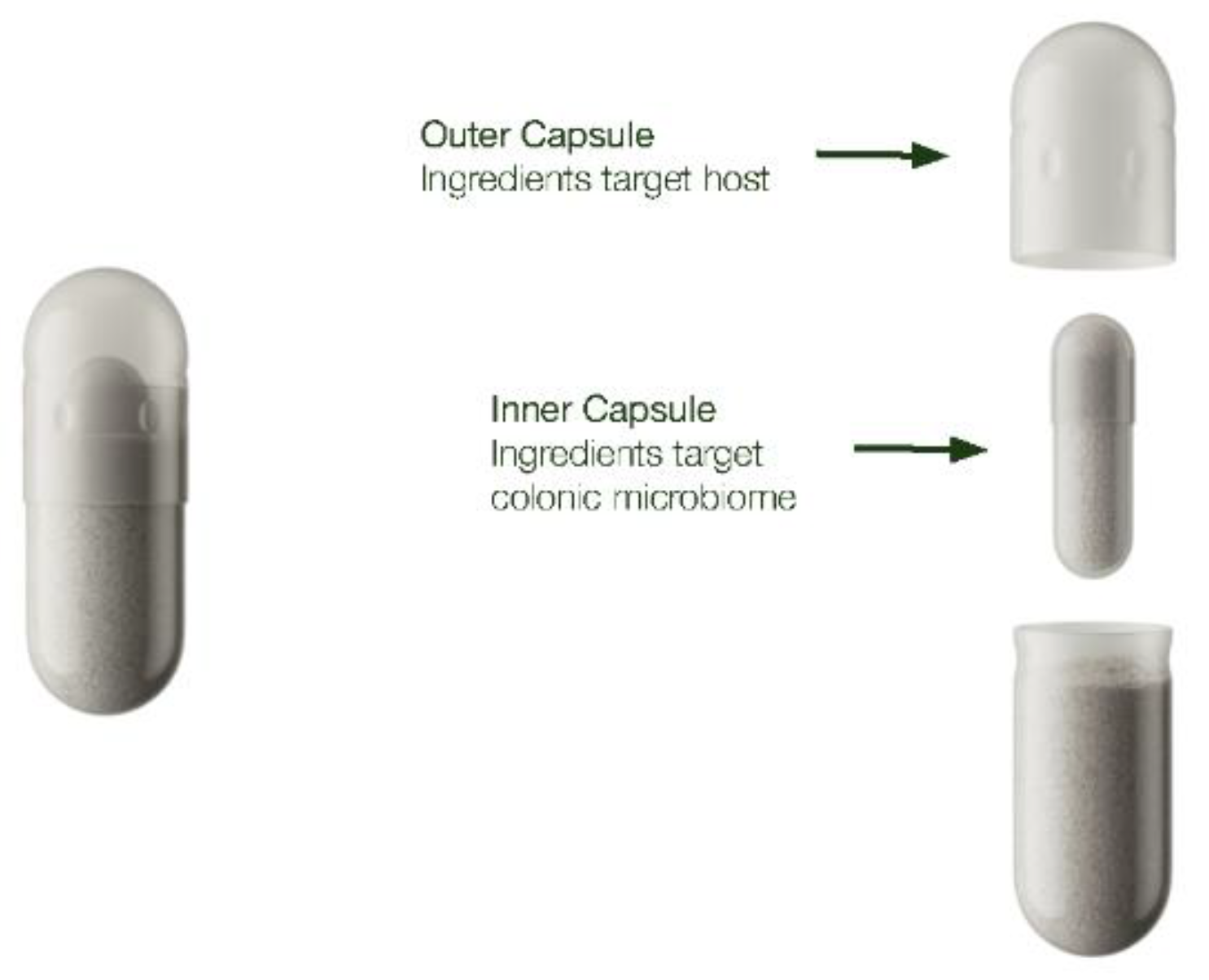

Delivery Mechanisms

Ensuring Microbiome Delivery

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davenport, ER; et al. The human microbiome in evolution. BMC Biol 2017, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, AH; et al. Cospeciation of gut microbiota with hominids. Science 2016, 353, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, TA; et al. Codiversification of gut microbiota with humans. Science 2022, 377, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat S, Asha null, Sharma KK. Gut-organ axis: a microbial outreach and networking. Lett Appl Microbiol 2021, 72, 636–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J; et al. Gut-microbiota-derived metabolites maintain gut and systemic immune homeostasis. Cells 2023, 12, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, JS; et al. Microbiota-gut-brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais LH, Schreiber HL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota-brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z; et al. Butyrate reduces appetite and activates brown adipose tissue via the gut-brain neural circuit. Gut 2018, 67, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H; et al. Depletion of acetate-producing bacteria from the gut microbiota facilitates cognitive impairment through the gut-brain neural mechanism in diabetic mice. Microbiome 2021, 9, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, JA; et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 16050–16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bs, S; et al. Evaluation of GABA production and probiotic activities of Enterococcus faecium BS5. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2021, 13, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J; et al. Effects of Bifidobacterium breve 207-1 on regulating lifestyle behaviors and mental wellness in healthy adults based on the microbiome-gut-brain axis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Nutr 2024, 63, 2567–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, JM; et al. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell 2015, 161, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, HX; et al. Lactobacillus plantarum DR7 alleviates stress and anxiety in adults: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Benef Microbes 2019, 10, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, KE; et al. A randomized controlled trial to examine the impact of a multi-strain probiotic on self-reported indicators of depression, anxiety, mood, and associated biomarkers. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1219313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace CJK, Milev RV. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of probiotics on depression: clinical results from an open-label pilot study. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 618279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H; et al. Bifidobacterium longum 1714TM strain modulates brain activity of healthy volunteers during social stress. Am J Gastroenterol 2019, 114, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Sanchez, M; et al. The gut-skin axis: a bi-directional, microbiota-driven relationship with therapeutic potential. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2473524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, MR; et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2096995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhaș, MC; et al. Transforming psoriasis care: probiotics and prebiotics as novel therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 11225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzhalii E, Hornuss D, Stremmel W. Intestinal-borne dermatoses significantly improved by oral application of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 5415–5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togawa, N; et al. Improvement of skin condition and intestinal microbiota via Heyndrickxia coagulans SANK70258 intake: A placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group comparative study. Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif 2024, 126, 112533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnoli, LIM; et al. Targeting the gut-eye axis: an emerging strategy to face ocular diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang AT, Marsland BJ. Microbes, metabolites, and the gut-lung axis. Mucosal Immunol 2019, 12, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu CL, Schnabl B. The gut-liver axis and gut microbiota in health and liver disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; et al. The gut-heart axis: unveiling the roles of gut microbiota in cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med 2025, 12, 1572948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, AM; et al. Gut-bladder axis enters the stage: Implication for recurrent urinary tract infections. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1066–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation promotes hair growth through gut microbiome and metabolic regulation. Life Sci 2025, 379, 123887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y. Exploring clues pointing toward the existence of a brain-gut microbiota-hair follicle axis. Curr Res Transl Med 2024, 72, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn J, Hayes RB. Environmental influences on the human microbiome and implications for noncommunicable disease. Annu Rev Public Health 2021, 42, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K; et al. Diet-induced dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the effects on immunity and disease. Nutrients 2012, 4, 1095–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vich Vila, A; et al. Impact of commonly used drugs on the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onali, T; et al. Berry supplementation in healthy volunteers modulates gut microbiota, increases fecal polyphenol metabolites and reduces viability of colon cancer cells exposed to fecal water- a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Biochem 2025, 141, 109906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, RL; et al. An alarming decline in the nutritional quality of foods: the biggest challenge for future generations’ health. Foods 2024, 13, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, NA; et al. Toxicomicrobiomics: the human microbiome vs. pharmaceutical, dietary, and environmental xenobiotics. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassaing, B; et al. Randomized controlled-feeding study of dietary emulsifier carboxymethylcellulose reveals detrimental impacts on the gut microbiota and metabolome. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindell AE, Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M, Patil KR. Multimodal interactions of drugs, natural compounds and pollutants with the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol 2022, 20, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, K; et al. Ultra-processed foods and food additives in gut health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 21, 406–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison A, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress, depression, diet, and the gut microbiota: human-bacteria interactions at the core of psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2019, 28, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neroni, B; et al. Relationship between sleep disorders and gut dysbiosis: what affects what? Sleep Med 2021, 87, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegierska, AE; et al. The connection between physical exercise and gut microbiota: implications for competitive sports athletes. Sports Med Auckl NZ 2022, 52, 2355–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weersma RK, Zhernakova A, Fu J. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut 2020, 69, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javdan, B; et al. Personalized mapping of drug metabolism by the human gut microbiome. Cell 2020, 181, 1661–1679.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdel, C; et al. Exploring the potential impact of probiotic use on drug metabolism and efficacy. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother 2023, 161, 114468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraj, BH; et al. Evolutionary concepts in the functional biotics arena: a mini-review. Food Sci Biotechnol 2021, 30, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revankar NA, Negi PS. Biotics: An emerging food supplement for health improvement in the era of immune modulation. J Parenteral Ent Nutr 2024, 39, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C; et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, ML; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on fermented foods. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, GR; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, KS; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 17, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, S; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmetti, S; et al. Commercial and regulatory frameworks for postbiotics: an industry-oriented scientific perspective for non-viable microbial ingredients conferring beneficial physiological effects. Trends Food Sci Technol 2025, 163, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenway F, Wang S, Heiman M. A novel cobiotic containing a prebiotic and an antioxidant augments the glucose control and gastrointestinal tolerability of metformin: a case report. Benef Microbes 2014, 5, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

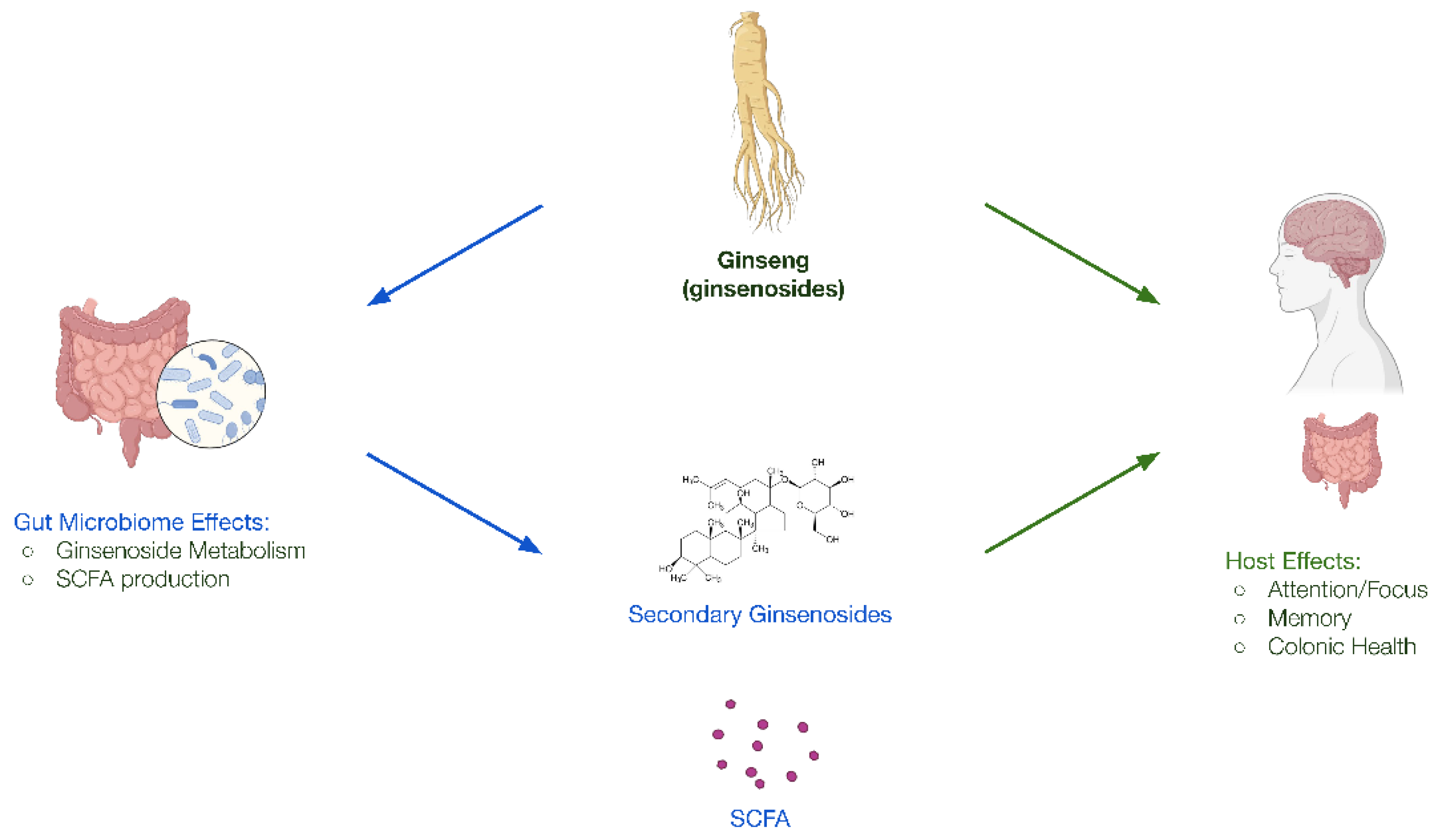

- Bell, L; et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial investigating the acute and chronic benefits of American Ginseng (Cereboost®) on mood and cognition in healthy young adults, including in vitro investigation of gut microbiota changes as a possible mechanism of action. Eur J Nutr 2022, 61, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormal, V; et al. Effect of hydroponically grown red Panax Ginseng on perceived stress level, emotional processing, and cognitive functions in moderately stressed adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay JL, Scholey AB, Kennedy DO. Panax ginseng (G115) improves aspects of working memory performance and subjective ratings of calmness in healthy young adults. Hum Psychopharmacol 2010, 25, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholey, A; et al. Effects of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) on neurocognitive function: an acute, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Psychopharmacol 2010, 212, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L; et al. Neuroprotective mechanisms of ginsenoside Rb1 in central nervous system diseases. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 914352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radad K, Moldzio R, Rausch W-D. Ginsenosides and their CNS targets. CNS Neurosci Ther 2011, 17, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J-F; et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 promotes neurotransmitter release by modulating phosphorylation of synapsins through a cAMP-dependent protein kinase pathway. Brain Res 2006, 1106, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L; et al. The interaction between ginseng and gut microbiota. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1301468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim YK, Yum K-S. Effects of red ginseng extract on gut microbial distribution. J Ginseng Res 2022, 46, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, RL; et al. Quercetin reduces blood pressure in hypertensive subjects. J Nutr 2007, 137, 2405–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mury, P; et al. Quercetin reduces vascular senescence and inflammation in symptomatic male but not female coronary artery disease patients. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T; et al. Quercetin ingestion alters motor unit behavior and enhances improvement in muscle strength following resistance training in older adults: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Eur J Nutr 2025, 64, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H-T; et al. Quercetin suppresses inflammatory cytokine production in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Exp Ther Med 2021, 22, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D; et al. Antioxidant activities of quercetin and its complexes for medicinal application. Molecules 2019, 24, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmering, R; et al. The growth of the flavonoid-degrading intestinal bacterium, Eubacterium ramulus, is stimulated by dietary flavonoids in vivo. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2002, 40, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Castaño, GP; et al. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron starch utilization promotes quercetin degradation and butyrate production by Eubacterium ramulus. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoefer, L; et al. Anaerobic degradation of flavonoids by Clostridium orbiscindens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69, 5849–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpino FM, Figueiredo LM. Resveratrol supplementation and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 4465–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushki M, Dashatan NA, Meshkani R. Effect of resveratrol supplementation on inflammatory markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Ther 2018, 40, 1180–1192.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadipoor, N; et al. Resveratrol supplementation efficiently improves endothelial health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytother Res 2022, 36, 3529–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X; et al. The role and mechanism of SIRT1 in resveratrol-regulated osteoblast autophagy in osteoporosis rats. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 18424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J-M; et al. Resveratrol up-regulates SIRT1 and inhibits cellular oxidative stress in the diabetic milieu: mechanistic insights. J Nutr Biochem 2012, 23, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X; et al. Activation of Sirt1 by resveratrol inhibits TNF-α induced inflammation in fibroblasts. PloS One 2011, 6, e27081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z; et al. Discovery of an ene-reductase initiating resveratrol catabolism in gut microbiota and its application in disease treatment. Cell Rep 2025, 44, 115517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M; et al. Resveratrol and its derivates improve inflammatory bowel disease by targeting gut microbiota and inflammatory signaling pathways. Food Sci Hum Wellness 2022, 11, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, V; et al. Resveratrol as a promising nutraceutical: implications in gut microbiota modulation, inflammatory disorders, and colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M; et al. Gut microbiota composition in relation to the metabolism of oral administrated resveratrol. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M; et al. Resveratrol attenuates trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)-induced atherosclerosis by regulating TMAO synthesis and bile acid metabolism via remodeling of the gut microbiota. mBio 2016, 7, e02210–e02215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrosa, M; et al. Effect of a low dose of dietary resveratrol on colon microbiota, inflammation and tissue damage in a DSS-induced colitis rat model. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 2211–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA panel on dietetic products, nutrition and allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on substantiation of health claims related to thiamine and energy-yielding metabolism (ID 21, 24, 28), cardiac function (ID 20), function of the nervous system (ID 22, 27), maintenance of bone (ID 25), maintenance of teeth (ID 25), maintenance of hair (ID 25), maintenance of nails (ID 25), maintenance of skin (ID 25) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J 2009, 7, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on dietetic products, nutrition and allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to riboflavin (vitamin B2) and contribution to normal energy-yielding metabolism (ID 29, 35, 36, 42), contribution to normal metabolism of iron (ID 30, 37), maintenance of normal skin and mucous membranes (ID 31, 33), contribution to normal psychological functions (ID 32), maintenance of normal bone (ID 33), maintenance of normal teeth (ID 33), maintenance of normal hair (ID 33), maintenance of normal nails (ID 33), maintenance of normal vision (ID 39), maintenance of normal red blood cells (ID 40), reduction of tiredness and fatigue (ID 41), protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage (ID 207), and maintenance of the normal function of the nervous system (ID 213) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J 2010, 8, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain KS, Amarasena S, Mayengbam S. B Vitamins and their roles in gut health. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, VT; et al. Vitamins, the gut microbiome and gastrointestinal health in humans. Nutr Res N Y N 2021, 95, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J; et al. Dietary Vitamin B1 intake influences gut microbial community and the consequent production of short-chain fatty acids. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, RE; et al. In vitro validation of colon delivery of vitamin B2 through a food grade multi-unit particle system. Benef Microbes 2024, 16, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, VT; et al. Effects of colon-targeted vitamins on the composition and metabolic activity of the human gut microbiome- a pilot study. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckirdy, S; et al. Micronutrient supplementation influences the composition and diet-originating function of the gut microbiome in healthy adults. Clin Nutr 2025, 51, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiwaki, H; et al. Meta-analysis of shotgun sequencing of gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2024, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsyth, CB; et al. Increased intestinal permeability correlates with sigmoid mucosa alpha-synuclein staining and endotoxin exposure markers in early Parkinson’s disease. PloS One 2011, 6, e28032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman P, Clemens RA, Hayes AW. Bioavailability of micronutrients obtained from supplements and food: A survey and case study of the polyphenols. Toxicol Res Appl 2017, 1, 2397847317696366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan SC, Savage GP. Oxalate content of foods and its effect on humans. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 1999, 8, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson GP, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol 2016, 14, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yersin S, Vonaesch P. Small intestinal microbiota: from taxonomic composition to metabolism. Trends Microbiol 2024, 32, 970–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, A; et al. Fat-soluble vitamin intestinal absorption: absorption sites in the intestine and interactions for absorption. Food Chem 2015, 172, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, RC. Intestinal absorption of water-soluble vitamins. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1996, 212, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solnier, J; et al. A pharmacokinetic study of different quercetin formulations in healthy participants: a diet-controlled, crossover, single- and multiple-dose pilot study. Evidence Based Complement Altern Med 2023, 2023, 9727539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakral S, Thakral NK, Majumdar DK. Eudragit: a technology evaluation. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2013, 10, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, V; et al. Microencapsulation of probiotics for enhanced stability and health benefits in dairy functional foods: a focus on pasta filata cheese. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Piano, M; et al. Evaluation of the intestinal colonization by microencapsulated probiotic bacteria in comparison with the same uncoated strains. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010, 44 (Suppl 1), S42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangmann, D; et al. Targeted microbiome intervention by microencapsulated delayed-release niacin beneficially affects insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M; et al. The construction of a double-layer colon-targeted delivery system based on zein-shellac complex and gelatin-isomaltooligosaccharide Maillard product: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Food Res Int 2025, 200, 115477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakoeswa, CRS; et al. Lactobacillus plantarum IS-10506 supplementation reduced SCORAD in children with atopic dermatitis. Benef Microbes 2017, 8, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautio, J; et al. Prodrugs: design and clinical applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008, 7, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha VR, Kumria R. Colonic drug delivery: prodrug approach. Pharm Res 2001, 18, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z; et al. Oral tributyrin treatment affects short-chain fatty acid transport, mucosal health, and microbiome in a mouse model of inflammatory diarrhea. J Nutr Biochem 2025, 138, 109847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biotic Category | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Probiotic | Live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host [45]. |

|

| Prebiotic | A substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit [47]. |

|

| Synbiotic | A mixture comprising of live microorganisms and substrate(s) selectively utilized by host microorganisms that confers a health benefit on the host [48]. |

|

| Postbiotic | A preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host [49]. |

|

| Co-biotic | A substrate comprising of bioactive molecular compounds that, when delivered to permit both host absorption and microbial accessibility, simultaneously modulate biological processes in both the host and its resident microbiota, to confer a targeted health benefit |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).