1. Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 virus continues to evolve, and Omicron sub-variants with increased transmissibility and immune escape have spread worldwide [

1]. Boosting the immune response acquired through vaccination has been recommended, particularly for the elderly and individuals at higher risk of severe COVID-19 [

2]. Although the disease is often asymptomatic or mild in children, they can still transmit the virus to susceptible individuals [

3]. Ideally, vaccination and booster doses are needed in all age groups to effectively control viral circulation and the emergence of new variants [

4].

The heterologous three-dose schedule of protein subunit anti-COVID-19 vaccines SOBERANA

® 02 (two doses administrated 28 days apart) and SOBERANA

® Plus (one dose given 28 days after the second dose) has demonstrated safety, immunogenicity and efficacy in both adult and pediatric populations [

5,

6,

7,

8]. In particular, a phase I/II clinical trial in children and adolescents aged 3-18 years (

https://rpcec.sld.cu/trials/RPCEC00000374-En) showed a robust neutralizing and cellular immune response, including the induction of immunological memory, with only 2.6% of participants reporting systemic adverse events [

8,

9]. Both humoral and cellular immune responses following primary immunization persisted for at least 5-7 months, with some cross-reactivity observed against the BA.1 Omicron sub-variant [

10]. Consistent with the results obtained during clinical development, post-authorization mass vaccination in Cuba demonstrated strong protection against symptomatic and severe disease caused by the Omicron variant in the pediatric population, with protection sustained over the six months follow-up period [

11].

The emergence of new Omicron sub-variants challenges the ability of licensed vaccines to induce specific neutralizing responses, prompting the development of updated mRNA vaccines [

12]. However, with only a few manufacturers capable of rapidly developing updated vaccines as new sub-variants emerge, high prices and vaccine shortages have limited immunization—particularly among children—and hindered booster administration [

13]. An alternative and less-explored strategy is to evaluate the neutralizing capacity against new sub-variants conferred by first-generation COVID-19 vaccines given as boosters in previously vaccinated individuals.

This study evaluates the safety and cross-reactive immunogenicity against Omicron sub-variants in children and adolescents who received a booster dose of SOBERANA® Plus vaccine at least six months after the primary vaccination with the three-dose schedule of the SOBERANA® 02 and SOBERANA® Plus vaccines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Approvals

A phase I/II open-label, multicenter, and adaptive study (

https://rpcec.sld.cu/trials/RPCEC00000374-En) was designed to evaluate the safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity of the primary vaccination consisting of two doses of SOBERANA

® 02 (SARS-CoV-2 recombinant receptor-binding domain, RBD, chemically conjugated to tetanus toxoid adjuvanted on alumina) and a third dose of SOBERANA

® Plus (recombinant dimeric RBD adjuvanted on alumina) 28 days apart, in children 3-18 y/o (herein stage 1). The safety and immunogenicity results of this primary immunization are published [

8].

The Ethics Committee of the “Juan Manuel Marquez” Pediatric Hospital and the National Regulatory Agency CECMED approved a modification of the study to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity in the same participants after the application of a booster dose of SOBERANA® Plus (herein Stage 2). The booster dose was administered at least 6 months after the third dose of the heterologous regimen.

2.2. Stage 2. Subjects and Ethics

A new signed informed consent was obtained from the parents, and consent was also obtained from the adolescents (participants aged 12-18 years). The children with COVID-19 diagnosis (confirmed by RT-PCR) during the follow-up period were excluded from receiving the booster dose of SOBERANA® Plus.

2.3. Safety Assessment

Following the administration of the booster dose, safety was evaluated by active professional surveillance for one hour after vaccination, at 24 hours, and on day 28. In addition, adverse events were daily recorded by the parents until day 28.

2.4. Immunogenicity Assessment

Blood samples were taken from all subjects before and 28 days after the booster dose. All pre-booster serum samples were tested for SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein to detect previous asymptomatic infections. The study population was divided into N-positive and N-negative children for data analysis. A subset of 17 serum samples (28%) from children classified as N-negative before vaccination (n=61) were selected using simple random sampling for pseudovirus-based neutralization assay (PBNA).

Immunogenicity was assessed as: (a) anti-RBD IgG antibodies by quantitative ultramicro enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (UMELISA SARS-CoV-2 anti-RBD); (b) the inhibitory capacity of the antibodies to block the RBD-hACE2 interaction, determined by competitive ELISA and expressed molecular virus neutralization titer (mVNT50); (c) conventional virus neutralization titer (cVNT50) vs. D614G (CU2010-2025, hCoV-19/Cuba/DC01/2020/GIDAID: EPI_ISL_7495115|2020-06-05) and omicron (BA.1. 21K, RRR, hCoV-19/Cuba/DC-RRR/2201/GISAID: EPI_ISL_12691753|2022-05-15) variants; and (d) pseudovirus-based neutralization assay (PBNA) vs. D614G, Omicron EG.5.1 and Omicron XBB.1.5. Procedures for immunologic techniques (a-c) were as previously described [

8].

PBNA: 200 TCID50 of pseudovirus (bearing SARS-CoV-2 Spike variants D614G, omicron EG.5.1 or omicron XBB.1.5) were preincubated in 96-well cell culture plates (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with heat-inactivated samples (dilutions 1:60 to 1:14580) for one hour at 37 °C. Then, 2 x104 HEK293T/hACE2 cells treated with DEAE-Dextran (Sigma-Aldrich) were added. Results were read after 48 hours using the EnSight Multimode Plate Reader and BriteLite Plus Luciferase reagent (PerkinElmer, USA). IC50 values were defined as the sample dilution inducing a 50% reduction of viral infectivity and were calculated by non-linear regression of inhibition curves using the GraphPad Prism Software [

14].

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein in serum samples was performed by the UMELISA protein N assay (Immunoassay Center, Havana, Cuba). Briefly, 10 µL of a 1/20 dilution of serum in Tris 0,371 mol/L-sheep serum 5% were added to ELISA plates (Greiner Bio-one, Germany) coated with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (CIGB, Cuba). Plates were incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C in a humid chamber. After washing the plates, 10 µL of alkaline phosphatase anti-human IgG in Tris 0,05 mol/L + Tween 20 0,05% + BSA 1% were added to each well and incubated as previously. After a wash step, 10 µL/well of 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate substrate was added. Fluorescence was read in a SUMA reader (CIE, Immunoassay Center, Havana, Cuba) after 30 minutes incubation in the dark. Samples with a fluorescent value higher than 30 were considered as positive: this cut off value was calculated as the mean of negative control samples plus 3 standard deviations.

2.5. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

We utilized the “OpenClinic” medical record system (

http://openclinic.sourceforge.net) to electronically store all data. Safety and reactogenicity were expressed as frequencies (%). Anti-RBD IgG concentration was expressed as median and interquartile range; molecular virus neutralization titer (mVNT50) and conventional virus neutralization titer (cVNT50) were expressed as geometric mean (GMT) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The Wilcoxon signed-Rank Test was used for before-after statistical comparison and Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between N-positive and N-negative individuals. For PBNA, the statistic differences were assessed using paired Student t test with log-transformed variables.

Statistical analyses were done using SPSS version 25.0; EPIDAT version 12.0 and Prism GraphPad version 6.0. An alpha signification level of 0.05 was used.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristic of Subjects and Flow Chart

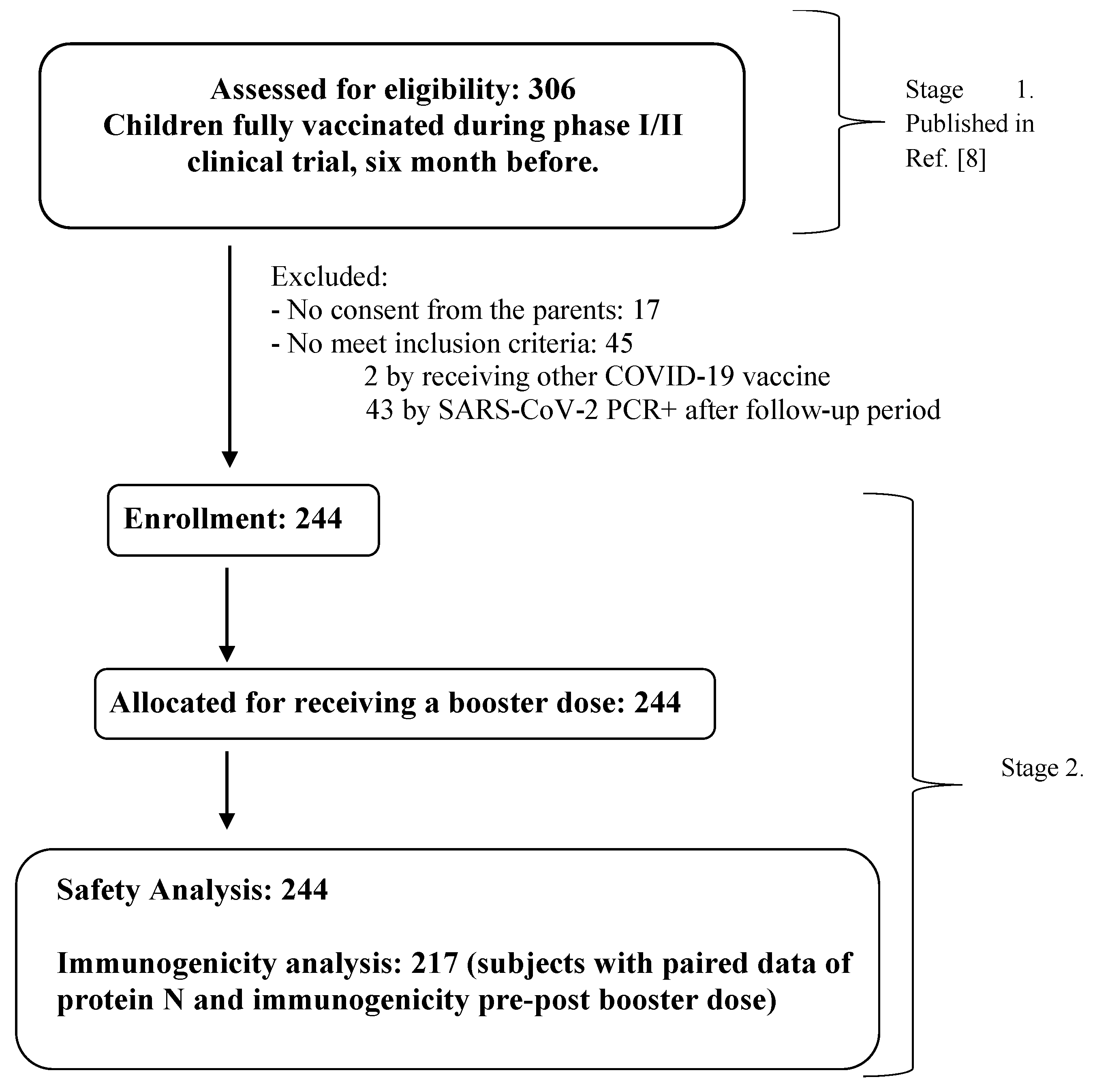

From February to April 2022, the 306 children who had completed the primary 3-dose vaccination (clinical trial stage 1) were invited to receive a booster dose of SOBERANA

® Plus. Of these, 62 were excluded because they were positive for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR (n=43), no consent granted from children’s parents (n=17) or the children received another COVID-19 vaccine (n=2).

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the 244 children included in Stage 2. A total of 217 subjects were included in the immunogenicity analysis, with pre- and post-booster results and also protein N determination (

Figure 1).

3.2. Safety After Applying the Booster Dose with SOBERANA® Plus

The participants (244 children) received a booster dose of SOBERANA

® Plus at least 6 months after the third dose of the heterologous schedule (in some children it was administered at 7 months). Safety was assessed for 28 days after the booster dose in all participant. The frequency of children with adverse events (AEs) after the booster dose was 18%, with no differences between the 3-11 and 12-18-year age groups. No serious or severe AEs were reported. Local events (85.2%) predominated over systemic events (14.8%) (

Table 2). The 97.7% of AEs were considered mild, and all recovered spontaneously (

Tables S1 and S2, Supplementary Information).

Local pain was the most common AE (10.7%), followed by swelling (6.6%), erythema (6.1%), and local warm (5.7%). Fever occurred in less than 1% of subjects (

Table S2, Supplementary Information). Nine children experienced unsolicited AEs (headache, functional impotence of the arm, and injection site pruritus) that were considered vaccine-related (

Table S3, Supplementary Information).

3.3. Immune Response After Applying the Booster Dose with SOBERANA® Plus

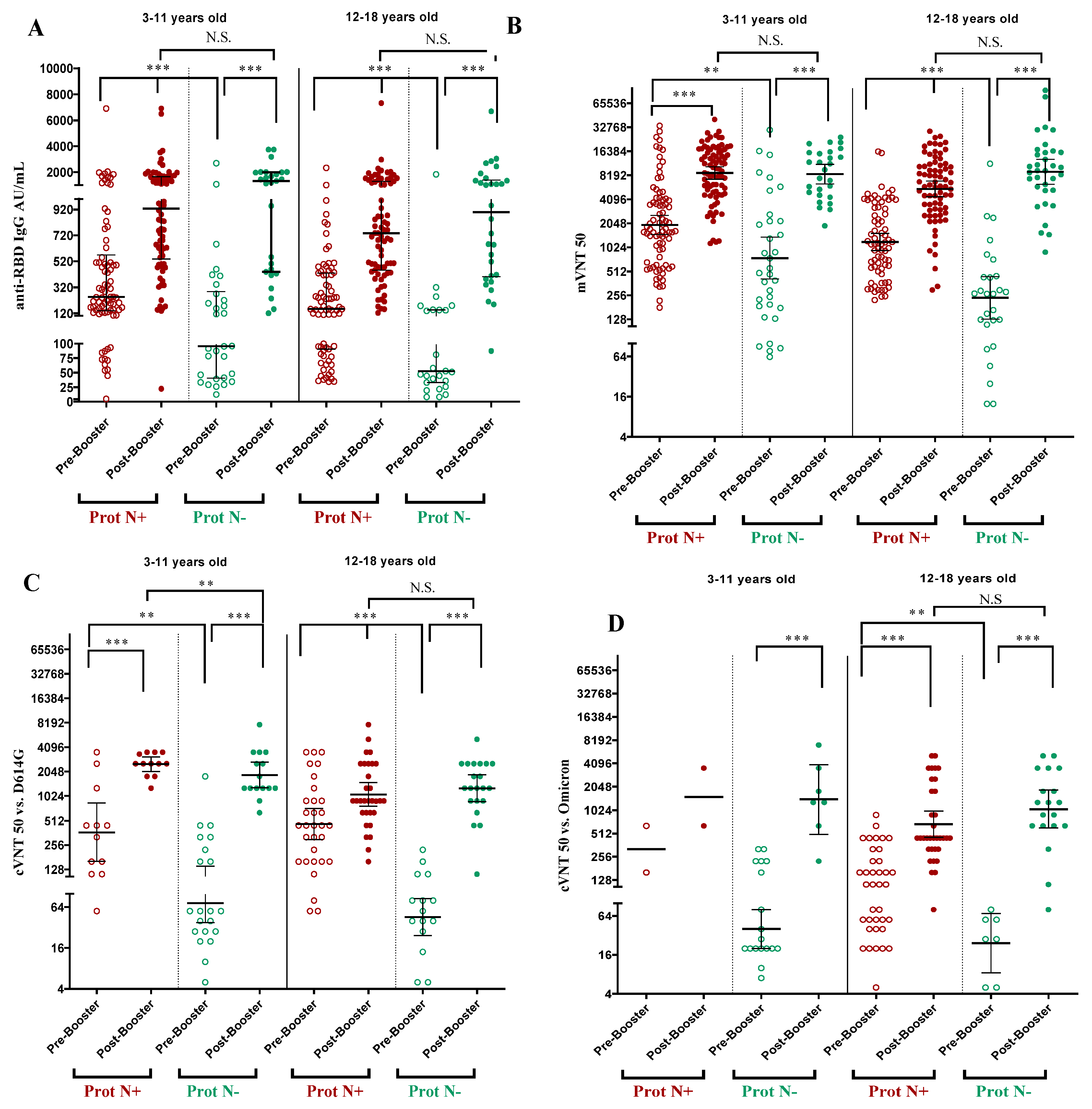

The immune response was assessed before and 28 days after the booster dose of SOBERANA

® Plus in children aged 3-18 years old. Children with immunological evaluations (n=217) were classified as N negative (n=61) or N positive (n=156) according to the detection of N protein in the serum before the booster dose. The children with previous asymptomatic infection (N-positive) had significantly higher IgG levels and neutralization titers than the N-negative children before the booster doses (

Figure 2),

Table S4, Supplementary Information).

Comparison of the immune response before and after the booster dose for paired samples showed a significant increase after vaccination for all variables, in both 3-11 and 12-18 age groups and in both N-negative and N-positive children (

Figure 2).

Anti-RBD IgG increased significantly from 87.4 UA/mL (CI 95% 37.4; 178.5) to 1062.4 AU/mL (CI 95% 421.6; 1867.2) in N-negative children aged 3-18 years, whereas in N-positive children the increase was from 231.6 AU/mL (CI 106.9; 489.8) to 791.0 (CI 488.2; 1465.6) (

Table S4, Supplementary Information). By age subgroup, there was no significant difference in IgG response after booster dose in children with or without previous asymptomatic infection (

Figure 2A).

The neutralizing activity of the antibody was determined by molecular (mVNT50) and conventional (cVNT50) neutralization assays using the D614G and Omicron BA.1 virus strain in a subset of samples. The mVNT50 and cVNT50 against D614G increased significantly after the booster doses in children aged 3-11 and 12-18 years, even if they were N-positive or N-negative (

Figure 2B,C). In the global population of children aged 3-18 years and N-protein negative, the cVNT50 against D614G resulted in a GMT of 1487.4 (CI 95% 1142.5; 1936.5) and against the omicron BA.1 variant 1141.4 (CI 95% 721.9; 1804.7) (

Figure 2D;

Table S4, Supplementary Information). Due to the small sample size, it was not possible to compare cVNT50 with Omicron BA.1 variant in the subgroup of N-positive children aged 3-11 years. When comparing N-positive and N-negative children, no statistical differences (p>0,05) were found for all immunological variables, except for cVNT50 against D614G in children aged 3-11 y/o, where N-positive had higher response (p=0.002).

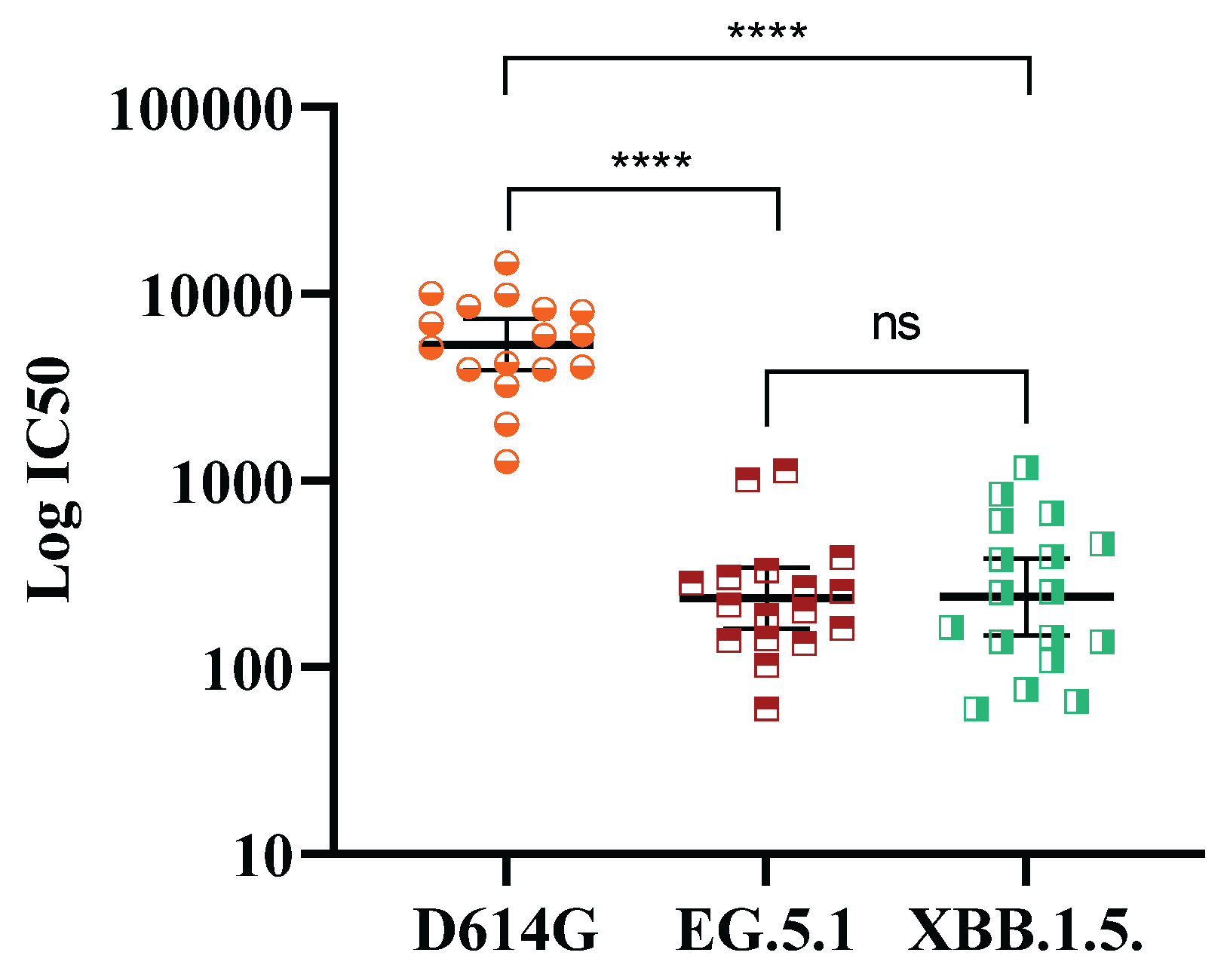

Deepening into the cross-response against evolving Omicron subvariants, 17 post-booster random samples from N negative subjects were tested by pseudovirus-based neutralization assay. As observed in

Figure 3, a booster dose of SOBERANA

® Plus elicited neutralization titers against omicron subvariants EG.5.1 and XBB.1.5 ranged 102 to 103, although is significantly lower (p<0.0001) compared with D614G.

4. Discussion

This study describes the safety and the immune response in children who received a booster dose of protein subunit vaccine SOBERANA® Plus at least six months after completing the primary vaccination series, which consisted of two doses of SOBERANA® 02 followed by a third dose of SOBERANA® Plus.

An excellent safety profile was observed following administration of the booster. The frequency of local pain (10.7%) was lower after the booster than after the third dose of the heterologous schedule of SOBERANA

® vaccines (47.7%) [

8]. Other AEs—such as swelling (6.6%), local warm (5.7%), and erythema (6.1%)—were reported at slightly higher frequencies after booster compared to the third dose of primary series (3.1%, 1.1%, 1.7%, respectively) [

8]. Fever, induration and low-grade fever were each reported at a frequency below 2%.

In a phase III study with another subunit vaccine, Nuvaxovid, administration of a booster dose approximately nine months after the primary series in adolescents aged 12-17 years resulted in injection site tenderness, headache, fatigue, injection site pain, muscle pain and malaise with reported frequencies ranging from 47% to 72% within seven days after the booster [

15].

Although the humoral response induced by the heterologous schedule of SOBERANA

® vaccine regimen declined with time [

10], administration of a SOBERANA

® Plus booster significantly increased all immunological parameters in children aged 3-18 years. Notably, no differences were observed between N-negative and N-positive participants following the booster dose.

Remarkably, a booster dose of SOBERANA

® Plus, containing RBD from the original SARS-CoV-2 strain, induced high neutralizing antibody titers in N-negative children aged 3-18 years. Compared to pre-booster levels, neutralizing antibodies increased by 24.7-fold against D614G variant and a 55.9-fold against Omicron BA.1 subvariant. This finding aligns with previous observations showing enhanced neutralizing activity against Omicron variant following booster doses of original—strain vaccines. In children aged 5-11 years who received a BNT162b2 booster 7-9 months after completing primary vaccination, neutralizing antibody levels were about 10- and 22-fold higher against ancestral and Omicron (B.1.1.529) variants, respectively [

16]. Another study in children and adolescents 3-17 y/o who received a booster dose of inactivated CoronaVac vaccine, 10-12 months after primary two-dose series, reported 28-to 47-fold and 11-to 20-fold increases in neutralizing antibodies against prototype and omicron strains, respectively, depending on dose and schedule. However, neutralizing titers against the prototype strain were 18-25 times higher than those against Omicron [

17].

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has continued to evolve, with Omicron subvariants acquiring mutations in the RBD and spike protein that confer antibody escape [

18], making it more difficult for first-generation vaccines to effectively neutralize them [

19]. A study with individuals aged 3-83 years who received up to four doses of inactivated, protein-subunit, or recombinant vectored vaccines showed that, in infection-naive individuals, the application of three or four doses led to a significant increase of neutralizing antibodies against prototype strain and Omicron subvariants BF.7, BQ.1, BQ.1.1 XBB.1, and XBB.1.5,—although responses against XBB.1, and XBB.1.5 were weaker [

20]. In our study, a booster dose with ancestral RBD-based SOBERANA

® Plus vaccine showed a neutralizing capacity against EC.5.1 and XBB.1.5 subvariants, albeit at lower levels compared to D614G.

This study has some limitations. First, the immune response was assessed only 28 days after the booster, as no long-term follow-up was planned. Second, T-cell responses were not evaluated. Another limitation—previously discussed in the publication of the Stage 1 of the trial [

8]—was the absence of placebo or control group. Stage 1 was conducted during the Delta variant wave in Cuba (weeks 22-42, 2021), a period marked by a sharp rise in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality across all age groups, including children. Under those circumstances, conducting a placebo-controlled clinical trial was considered unethical.

In conclusion, administration of a SOBERANA® Plus booster dose elicited a substantial increase in both total and neutralizing antibodies against both D614G and Omicron BA.1 with no safety concerns. Neutralizing activity was also detected against the EG.5.1 and XBB.1.5 Omicron subvariants. Although updated vaccines are recommended to better match circulating subvariants, our findings underscore the value of first-generation RBD-based vaccines as booster doses in children and adolescents, maintaining the recognition of new variants of virus with an excellent safety profile.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Global characterization of adverse events after the booster dose with SOBERANA® Plus vaccine; Table S2: Frequency of solicited adverse events after the booster dose with SOBERANA® Plus vaccine; Table S3: Unsolicited adverse events after the booster dose with SOBERANA® Plus vaccine; Table S4: Antibody response before and 28 days after booster dose with SOBERANA® Plus vaccine, in children classified as protein N negative or positive.

Author Contributions

DGR, MRG, BPM and CVS conceptualized the study. RPG and YRD were clinical investigator of the trial. CVS performed the statistical analysis. RPN, LRN, DSM, YCR, SFC, ENR, OCS, BSR, THG, APD evaluated the immunological samples. SFC, YCR, DSM, YVB, VVB were responsible for vaccine development and manufacturing. DGR and SFC drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Funds for Sciences and Technology from the Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment (FONCI-CITMA-Cuba, contract 2020–20).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of “Juan Manuel Marquez” Pediatric Hospital and endorsed by the Cuban National Pediatric Group. The Cuban National Regulatory Agency (Centre for State Control of Medicines and Medical Devices, CECMED) approved the trial (Stage 1: June10th, 2021, Authorization Reference: 05.010.21BA) and the modification of the study that included the follow-up of safety and immunogenicity six months after primary schedule and after booster administration (Stage 2: February 17, 2022; Authorization Reference: 06.004.22BM).

Informed Consent Statement

During recruitment, the medical investigators provided to the parents, both orally and written, all information about the vaccine and potential risks and benefits. Both parents signed the informed consent for including their children in the trial. The decision to participate was not remunerated. The parents signed an informed consent for including their children in this study and the results were informed to them. Trial registry: RPCEC00000374 (Cuban Public Registry of Clinical Trials and WHO International Clinical Registry Trials Platform) [

21].

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would especially thank the parents and children who participated in this study. We thank Dr. Lila Castellanos for her scientific advice and corrections.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors DGR, SFC, BPM, MRG, RPN, LRN, DSM, YCR, YVB, VVB declare to be employees at Finlay Vaccine Institute. The rest of the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. No author received an honorarium for contributing to this paper.

References

- W.H.O. COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update- 12 March 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update-edition-177 (accessed March 14, 2025).

- W.H.O. COVID-19 advice for the public: Getting vaccinated. 8 October 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/advice (accessed March 14, 2025).

- Paul, L.A.; Daneman, N.; Schwartz, K.L.; et al. Association of age and pediatric household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175(11), 1151-1158. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Zhu, F.C. The era of SARS-CoV-2 variants calls for an urgent strategy for COVID-19 vaccination in children. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, 666-667. [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Romani, ME; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of anti-SARS-CoV-2 heterologous scheme with SOBERANA 02 and SOBERANA Plus vaccines: Phase IIb clinical trial in adults. Med 2022, 3, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Mostafavi, E.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of a protein-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6(4), e2310302. [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Romani, ME; et al. Safety and efficacy of the two doses conjugated protein-based SOBERANA-02 COVID-19 vaccine and of a heterologous three-dose combination with SOBERANA PLUS: double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet Regi Health—Am 2023, 18, 100423. [CrossRef]

- Puga-Gómez, R.; et al. Open label phase I/II clinical trial of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine (FINLAY-FR-2) in combination with receptor binding domain-protein vaccine (FINLAY-FR-1A) in children. Int J Infect Dis 2023, 126, 164-73. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Nicado, R.; Massa, C.; Rodríguez-Noda, L.M.; Müller, A.; Puga-Gómez, R.; Ricardo-Delgado, Y.; Paredes-Moreno, B.; Rodríguez-González, M.; García-Ferrer, M.; Palmero-Álvarez, I.; et al. Comparative Immune Response after Vaccination with SOBERANA® 02 and SOBERANA® plus Heterologous Scheme and Natural Infection in Young Children. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1636. [CrossRef]

- García-Rivera, D.; Puga-Gómez, R.; Fernández-Castillo, S.; Paredes-Moreno, B.; Ricardo-Delgado, Y.; Rodríguez-González, M.; et al. Safety and durability of the immune response after vaccination with the heterologous schedule of anti-COVID-19 vaccines SOBERANA®02 and SOBERANA® Plus in children 3–18 years old. Vaccine: X 2025, 22, 100595. [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Romani, ME; et al. Real-world effectiveness of the heterologous SOBERANA-02 and SOBERANA-Plus vaccine scheme in 2–11 years-old children during the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron wave in Cuba: a longitudinal case-population study. Lancet Regi Health—Am. 2024, 34, 100750. [CrossRef]

- Link-Gelles, R.; Ciesla, A.A.; Mak, J.; et al. Early estimates of updated 2023–2024 (monovalent XBB.1.5) COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection attributable to co-circulating Omicron variants among immunocompetent adults—Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, September 2023–January 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024; 73, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C. Why COVID Vaccines for Young Children Have Been Hard to Get. November 21, 2023. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-covid-vaccines-for-young-children-have-been-hard-to-get/(accessed March 14, 2025).

- Pradenas, E. et al. Stable neutralizing antibody levels 6 months after mild and severe COVID-19 episodes. Med (NY) 2021, 2, 313–320. [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Summary of Product Characteristics. Nuvaxovid. December 20, 2021. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/nuvaxovid-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed March 14, 2025).

- COVID-19 Update. Booster Dose of the Pfizer Vaccine for Children 5-11 Years Old. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2022, 64, 94.

- Wang, L.; Wu, Z.; Ying, Z.; Li, M.; Hu, Y.; Shu, Q.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity following a homologous booster dose of CoronaVac in children and adolescents. Nat Commun 2022, 13(1), 6952. [CrossRef]

- Planas, D.; Staropoli, I.; Michel, V.; Lemoine, F.; Donati, F.; Prot, M.; et al. Distinct evolution of SARSCoV-2 Omicron XBB and BA.2.86/JN.1 lineages combining increased fitness and antibody evasion. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2254. [CrossRef]

- Kurhade, C.; Zou, J.; Xia, H.; et al. Low neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1 and XBB.1 by parental mRNA vaccine or a BA.5 bivalent booster. Nat Med. 2023, 29, 344–347. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; et al. The contributions of vaccination and natural infection to the production of neutralizing antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 prototype strain and variants. Int J Infect Dis. 2024, 144, 107060. [CrossRef]

- International register clinical trials. Identifier RPCEC00000374. Phase I–II study, sequential during phase I, open-label, adaptive and multicenter to evaluate the safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of a heterologous two-dose schedule of the prophylactic anti-SARS- CoV-2 vaccine candidate, FINLAY-FR- 2 and a dose of FINLAY-FR-1A. 2021 Available online: https://rpcec.sld.cu/trials/RPCEC00000374-En.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).