Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Princeples and Methods

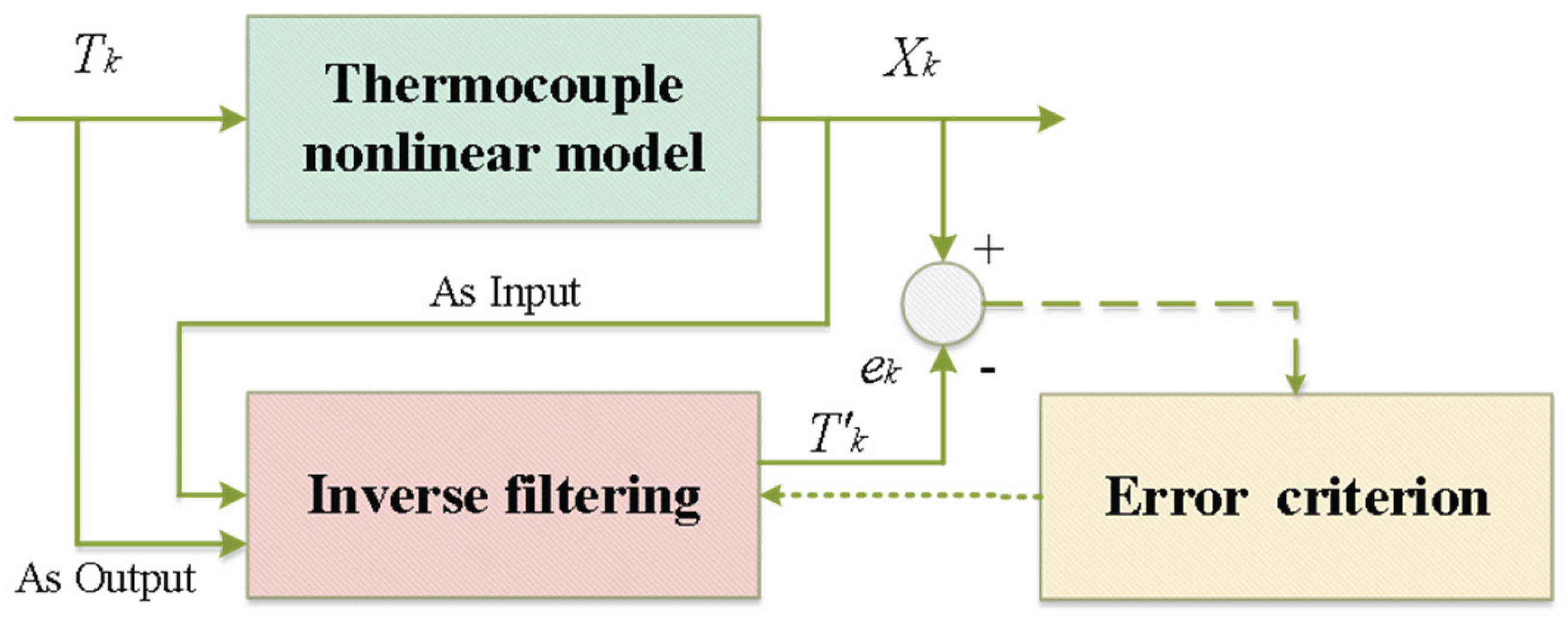

2.1. Principle of Thermocouple Dynamic Inverse Filtering

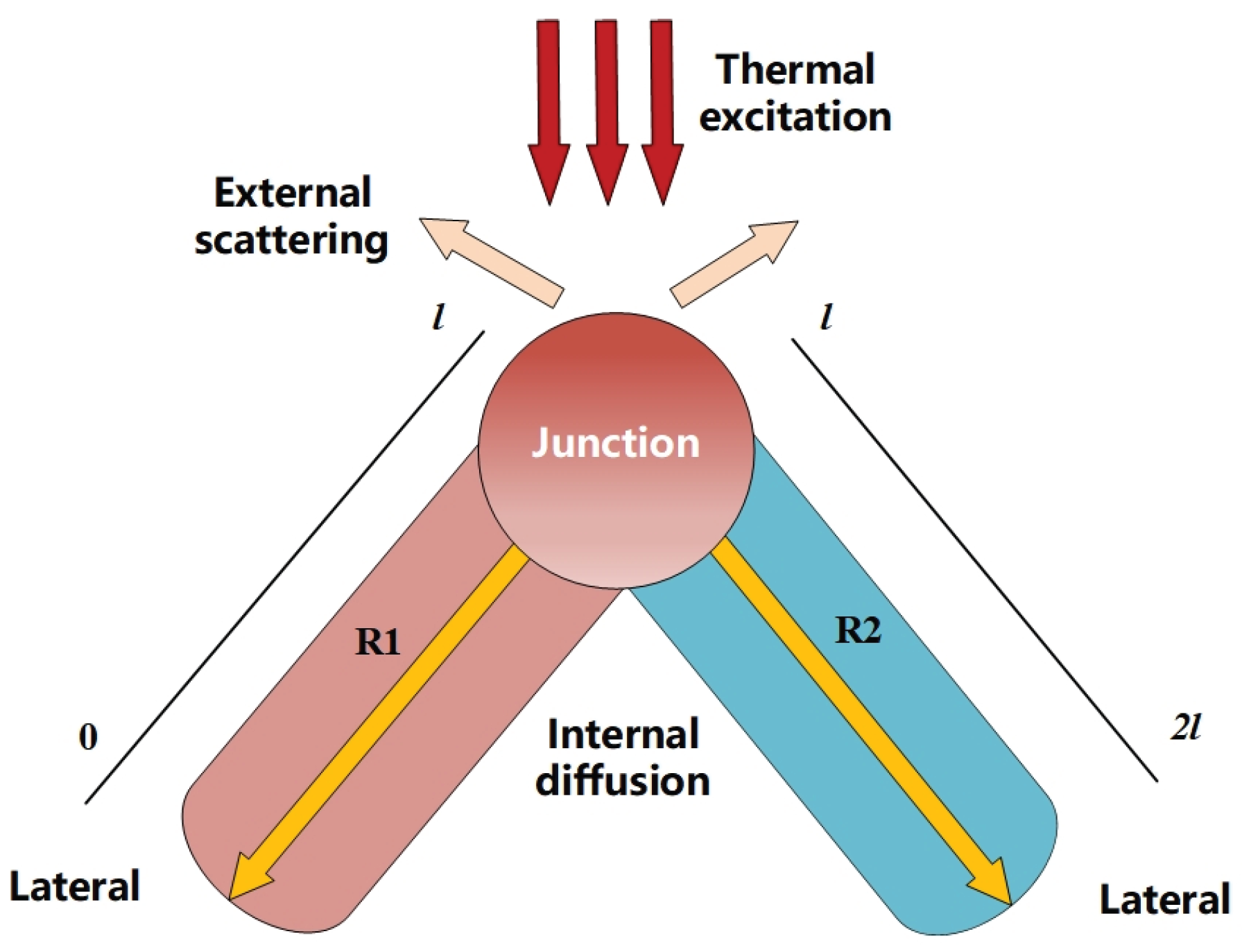

2.2. Inverse Problem Analysis

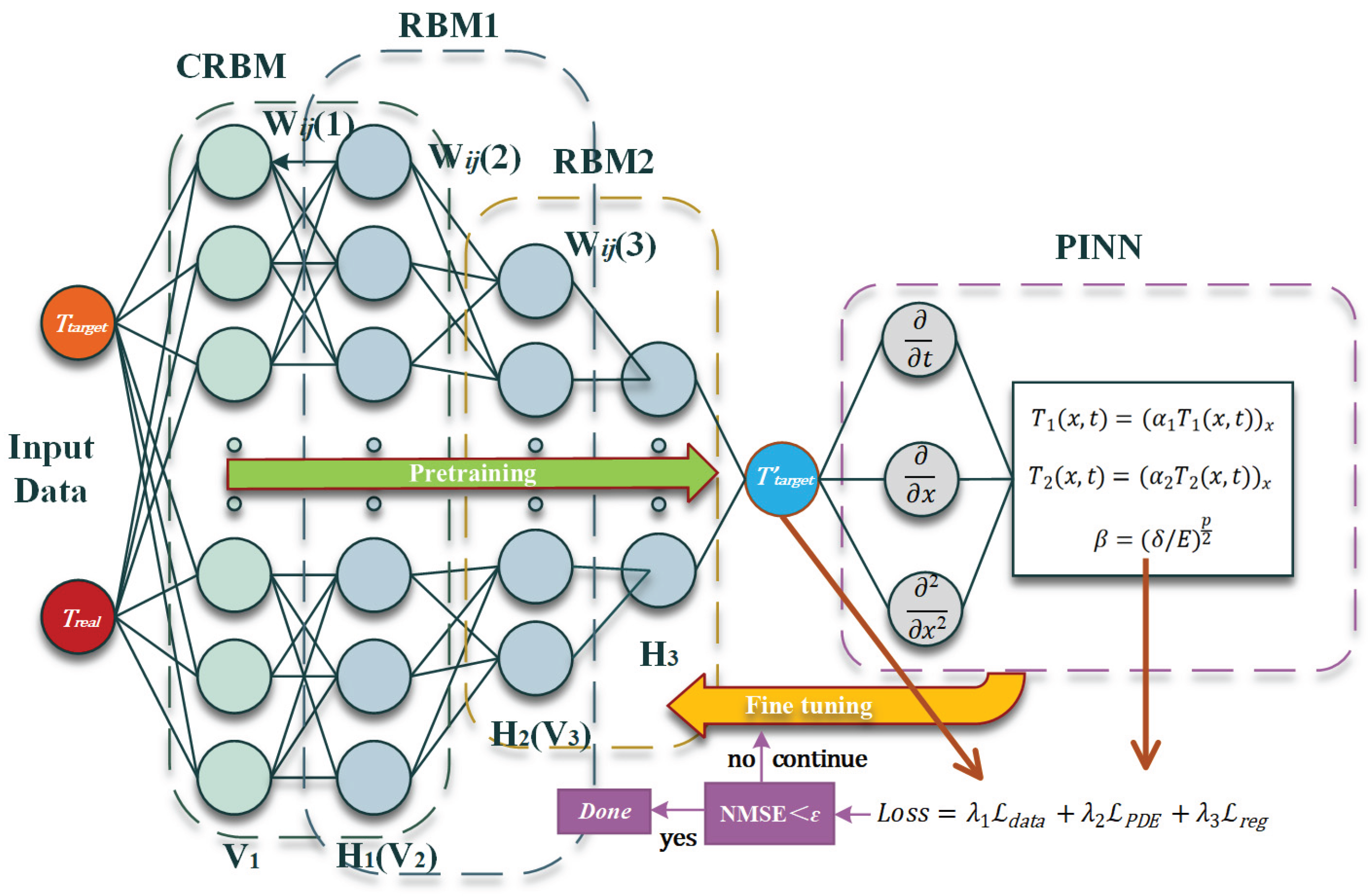

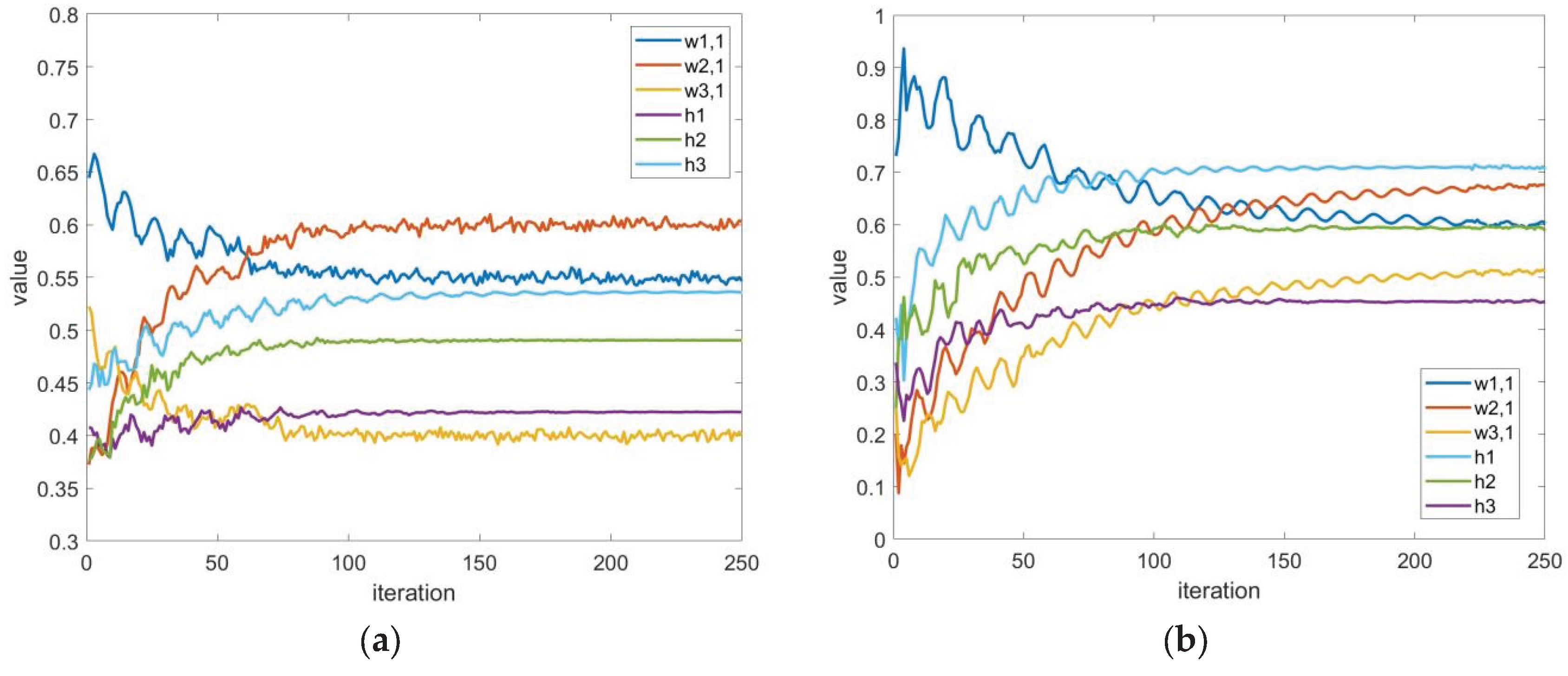

2.3. Improved CRBM-DBN-PINN Model

3. Experiment

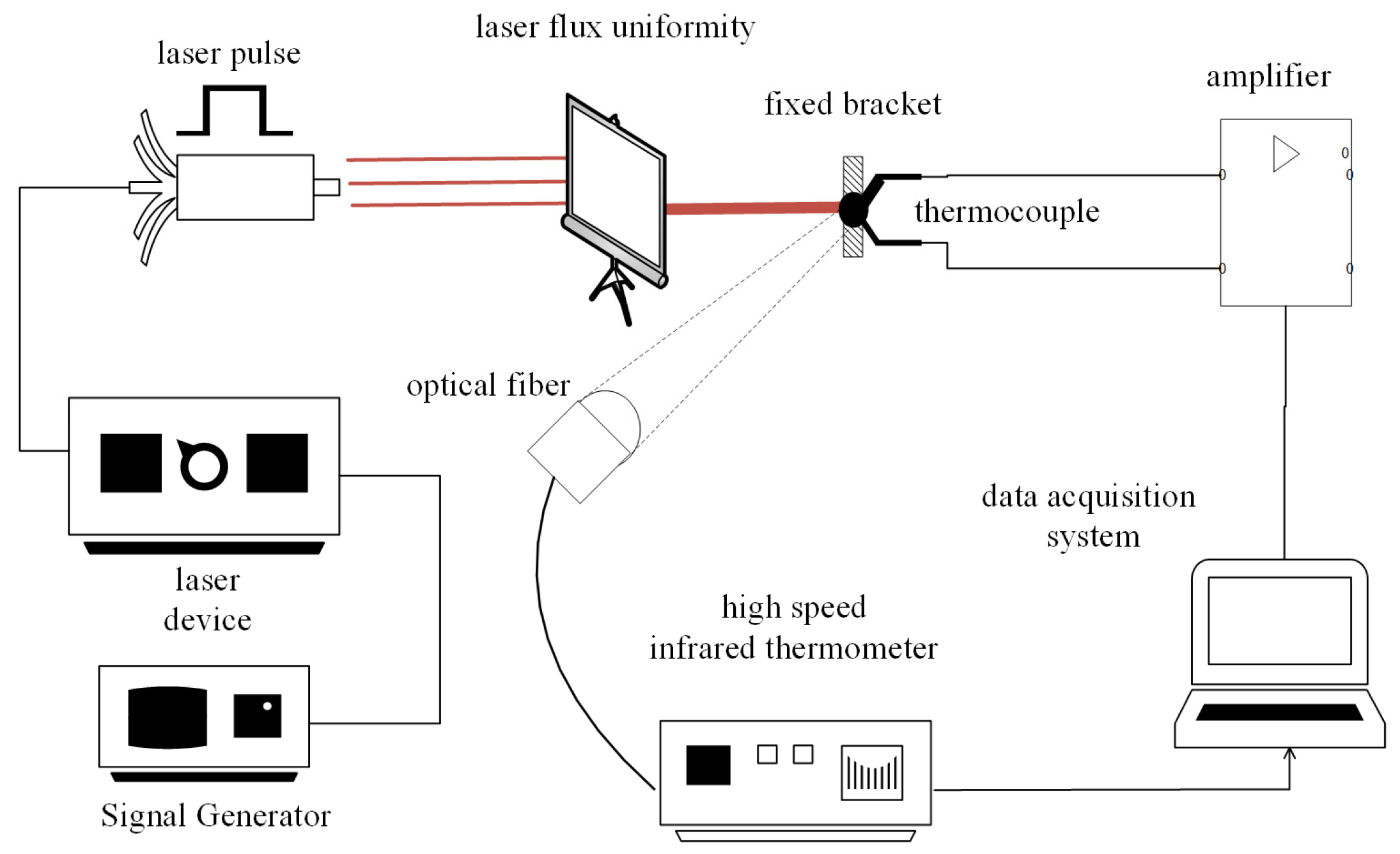

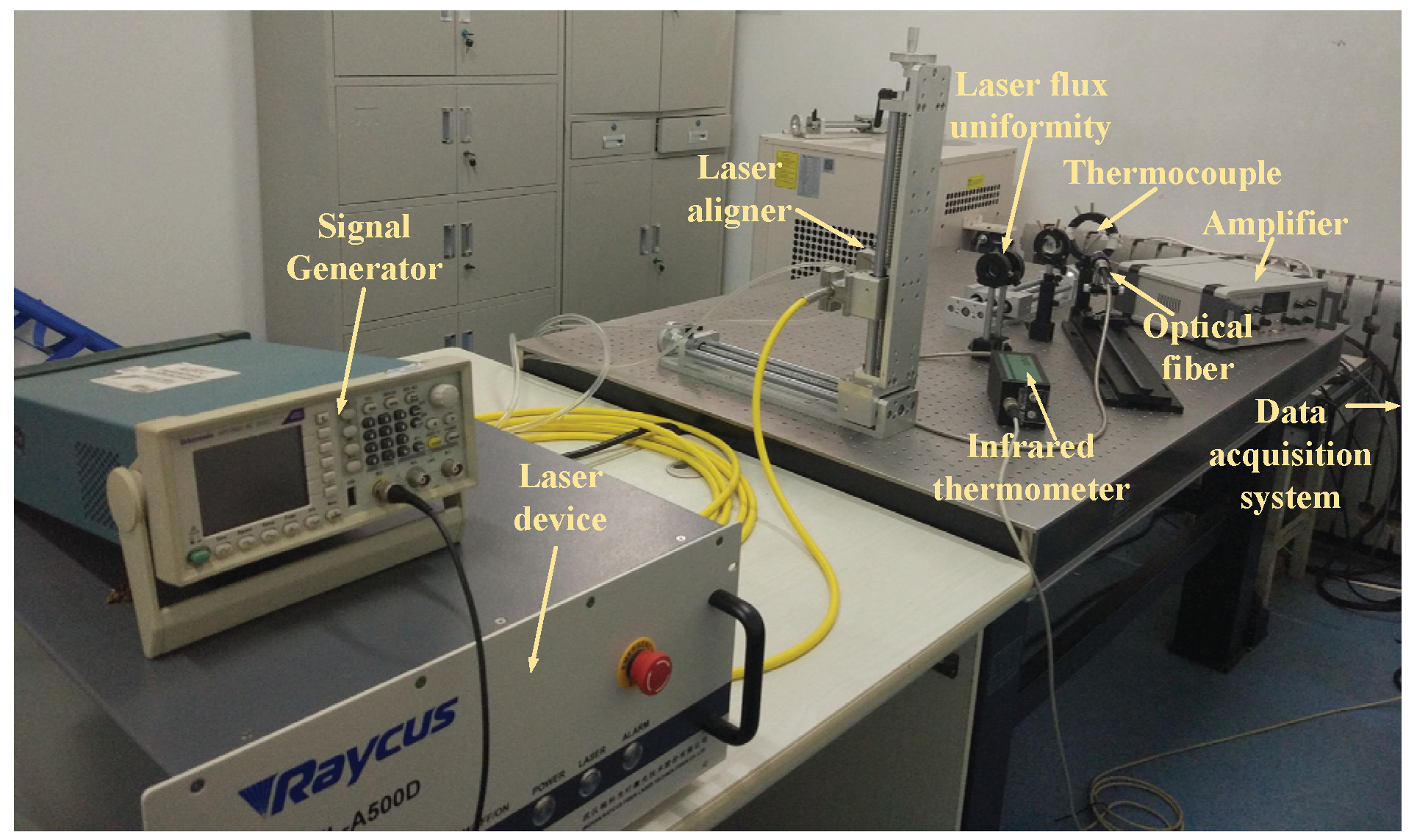

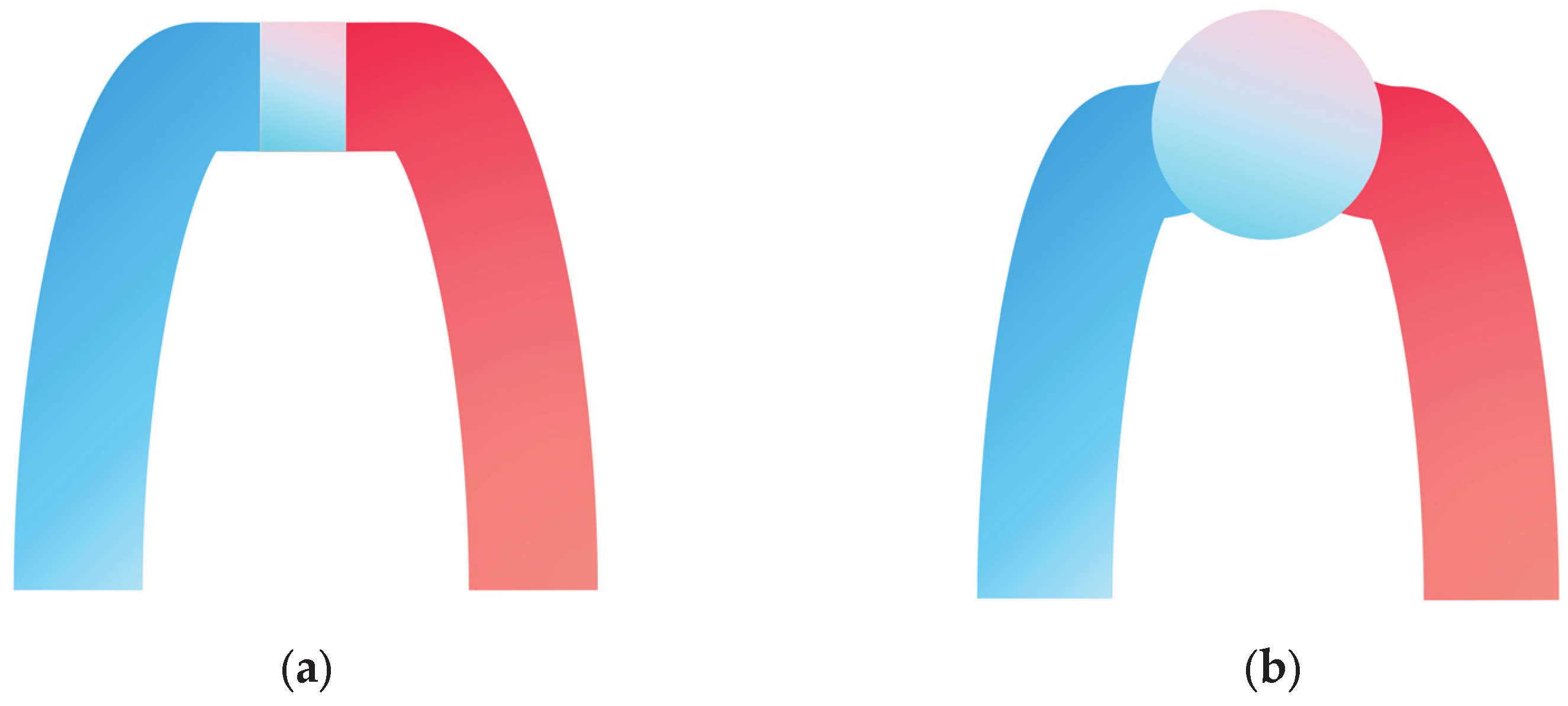

3.1. Laser Narrow Pulse Calibration Platform

3.2. Experimental Steps

4. Results and Analysis

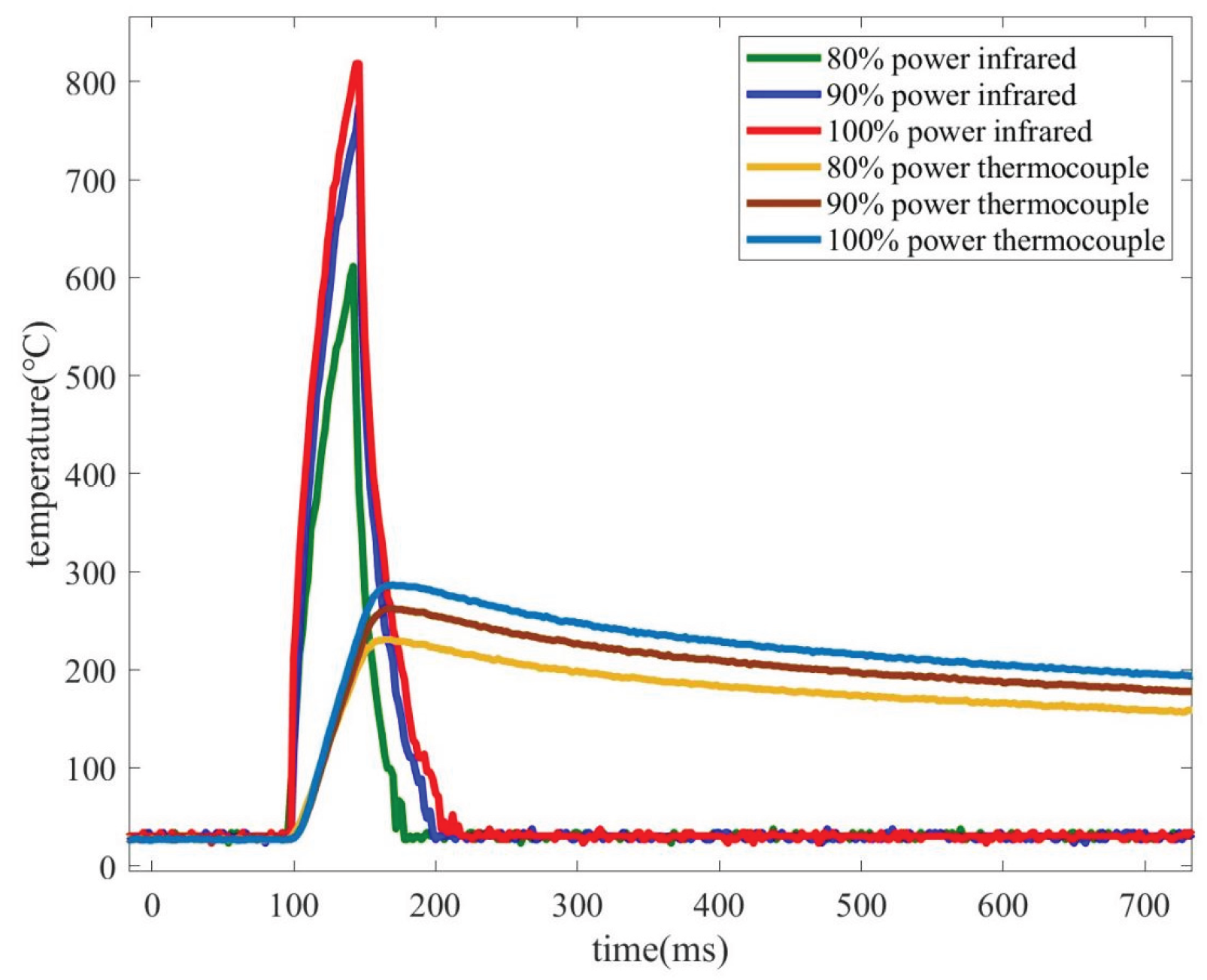

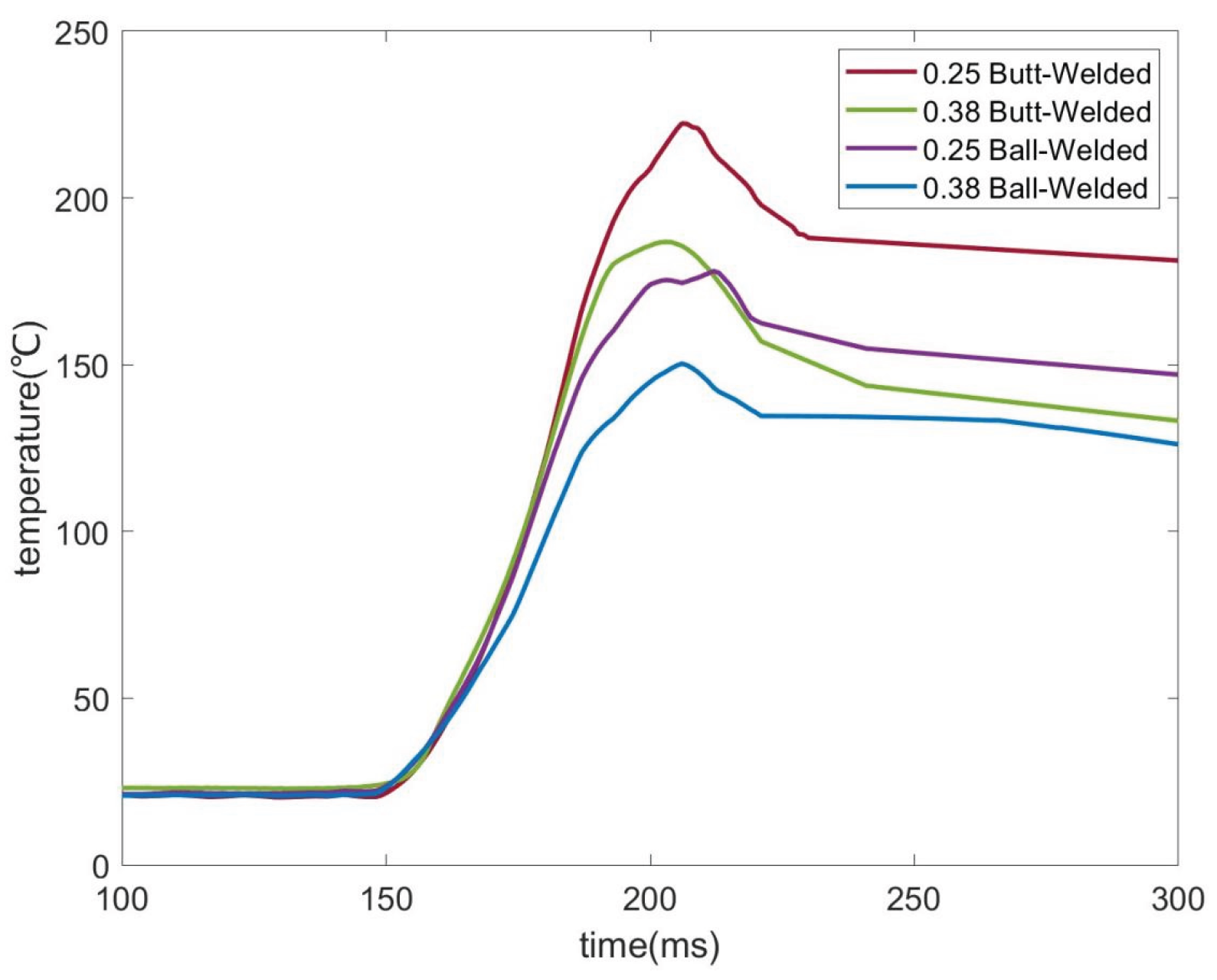

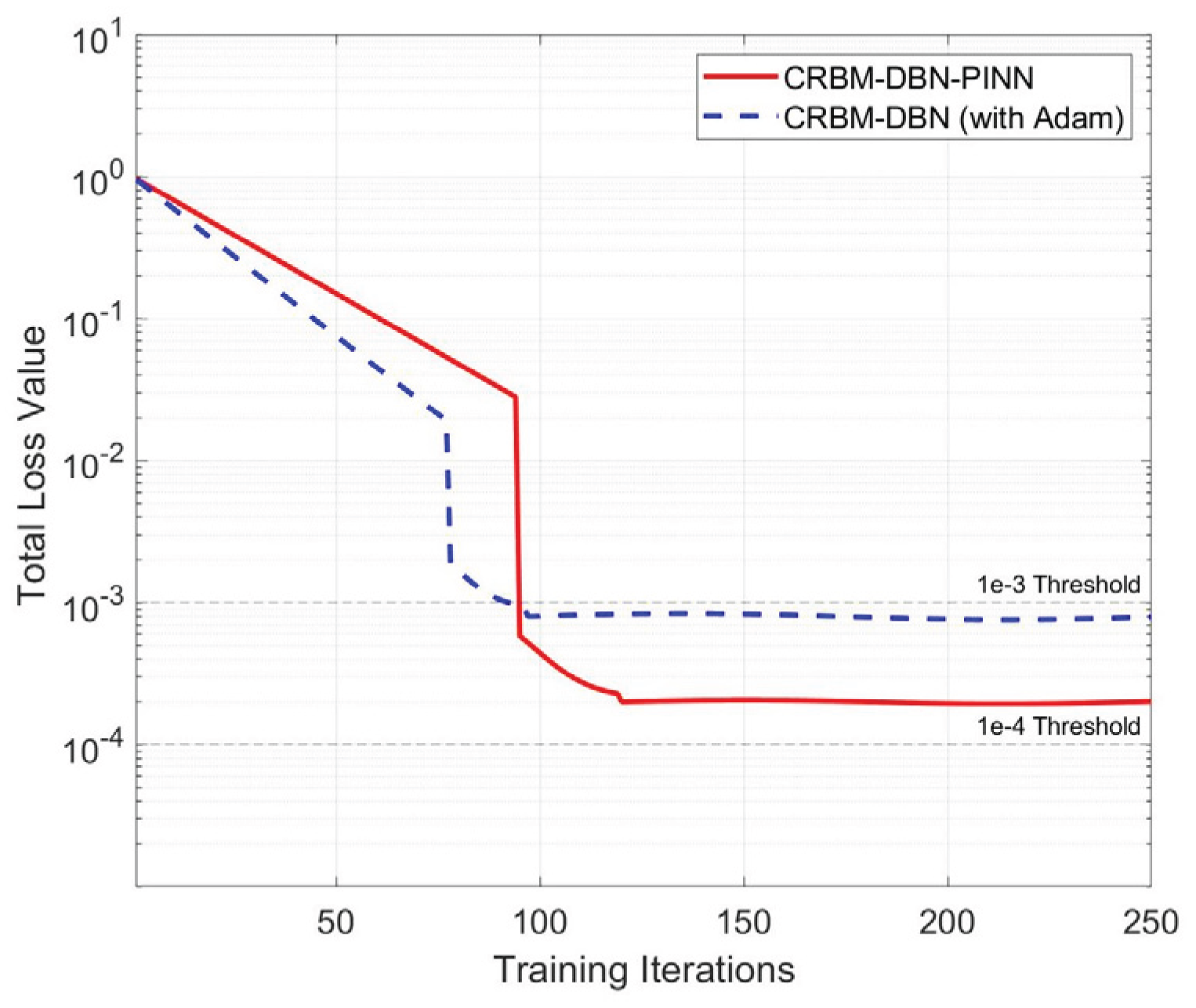

4.1. Model Accuracy Analysis

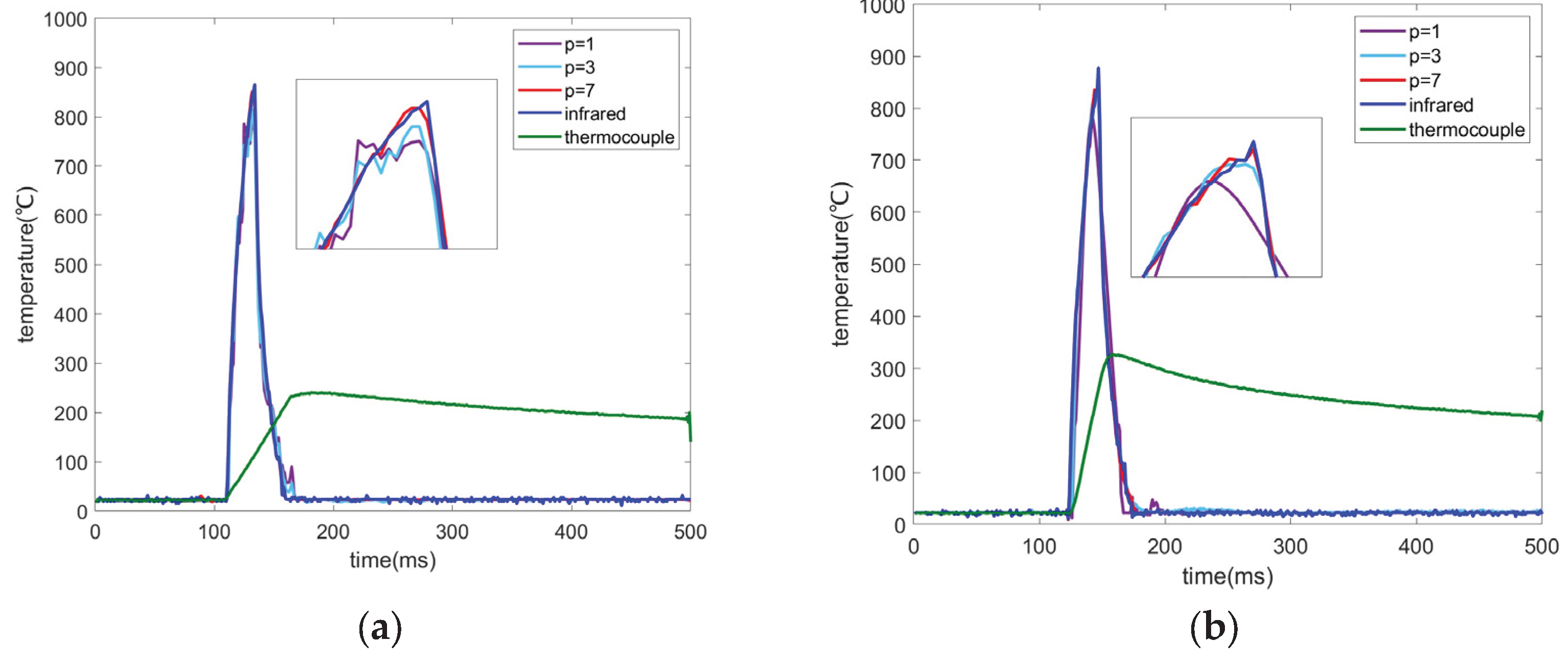

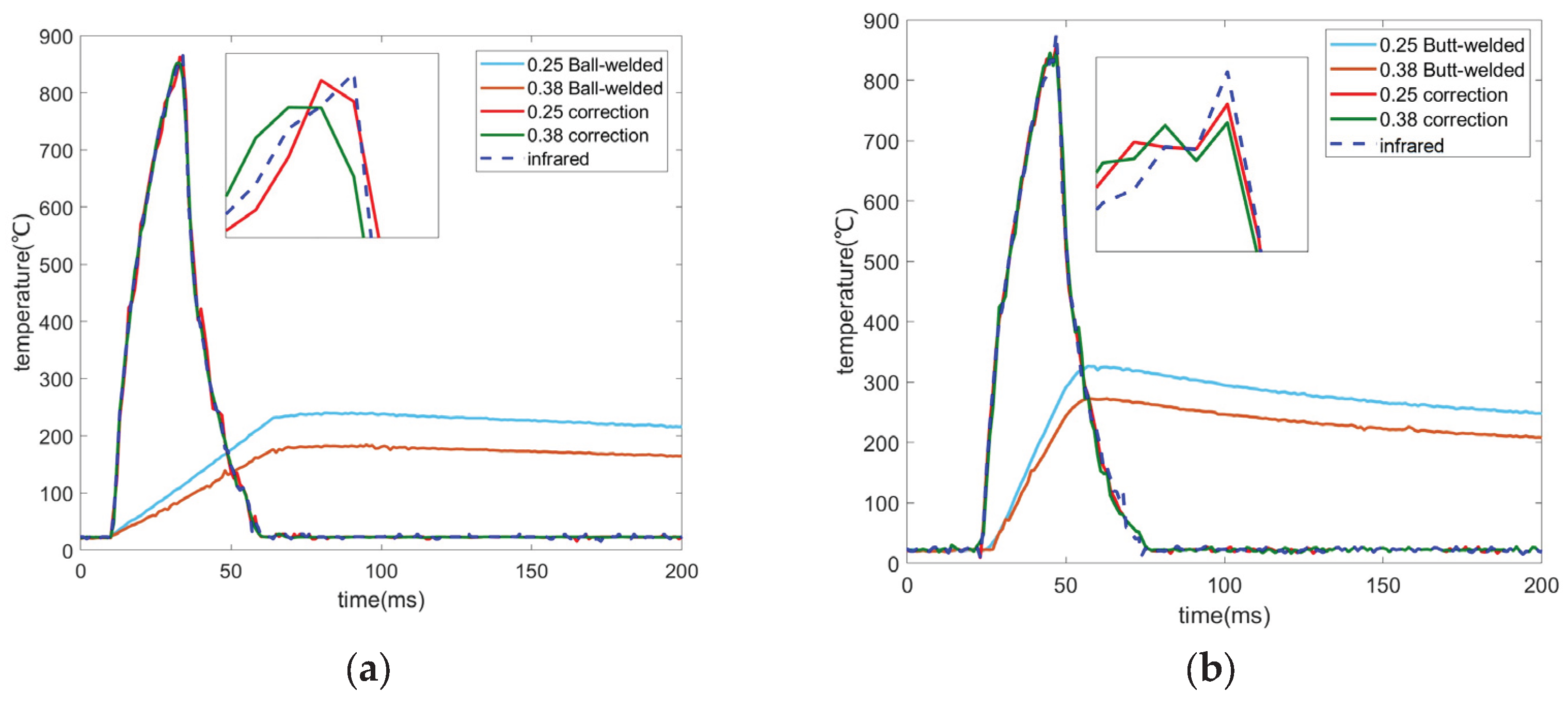

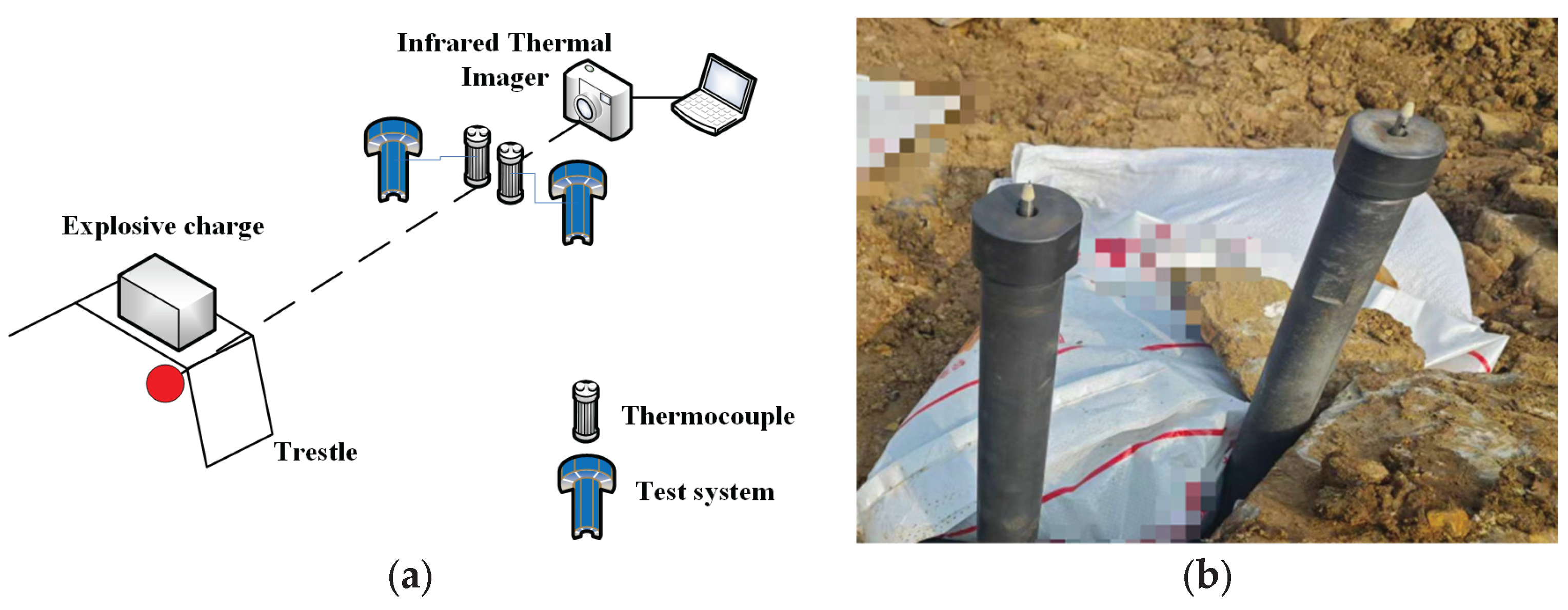

4.2. Blast Test and Result Analysis

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z. L., Wang, G., Yin, J. P., Xue, H. X., Guo, J. Q., Wang, Y., Huang, M. G. Development and Performance Analysis of an Atomic Layer Thermopile Sensor for Composite Heat Flux Testing in an Explosive Environment. Electronics 2023, 12(17), 18, 3582. [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, D., Battista, F., Gallo, G., Mungiguerra, S., Savino, R. Experimental Firing Test Campaign and Nozzle Heat Transfer Reconstruction in a 200 N Hybrid Rocket Engine with Different Paraffin-Based Fuel Grain Lengths. Aerospace 2023, 10(6), 20, 546. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Y., Huang, Y., He, Y., Zhu, Y. Q., Wang, Z. H. Review of Development and Comparison of Surface Thermometry Methods in Combustion Environments: Principles, Current State of the Art, and Applications [Review]. Processes 2022, 10(12), 40, 2528. [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, K., Benko, P. Analysis of the Upper Bound of Dynamic Error Obtained during Temperature Measurements. Energies 2022, 15(19), 13, 7300. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. Y., Wang, Z. H., Gui, L. J. Contact mode thermal sensors for ultrahigh-temperature region of 2000–3500k. Rare Metals 2019, (8). [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. X., Lin, Z. Y., Zhang, Z. J., Li, Y. F., Chen, H. Z., Liu, J. Q., Li, C. Fabrication and Calibration of Pt-Rh10/Pt Thin-Film Thermocouple. Micromachines 2023, 14(1), 15, 4. [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z. H., Wu, R. X., Wang, Q. Y., Li, B. B., Li, C. Z., & Yin, X. Y. Heat transfer error analysis of high-temperature wall temperature measurement using thermocouple. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2024, 59, 13, Article 104518. [CrossRef]

- Jaremkiewicz, M.. Reduction of dynamic error in measurements of transient fluid temperature. Archives of Thermodynamics 2011, 32(4), 55-66. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. X., Meng, X. F. Study on transient temperature generator and dynamic compensation technology. Applied Mechanics & Materials 2014, 511-512, 161-164. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Y., Huang, Y., He, Y., Zhu, Y. Q., Wang, Z. H. Review of Development and Comparison of Surface Thermometry Methods in Combustion Environments: Principles, Current State of the Art, and Applications [Review]. Processes 2022, 10(12), 40, Article 2528. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. K., Zhang, Z. J., Li, Y. F., Wang, W. Z. C-type two-thermocouple sensor design between 1000 and 1700 °C. Review of Scientific Instruments 2024, 95(10), 12, 105119. [CrossRef]

- Chu, J. R., Wang, S. L., Gan, R. L., Wang, W. H., Li, B. R., Yang, G. Dynamic compensation by coupled triple-thermocouples for temperature measurement error of high-temperature gas flow. Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control 2024, 46(5), 952-961. [CrossRef]

- Woolley, J. W., Woodbury, K. A. Thermocouple Data in the Inverse Heat Conduction Problem. Heat Transfer Engineering 2011, 32(9), 811-825. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Y., Frankel, J. I., Keyhani, M. Nonlinear, rescaling-based inverse heat conduction calibration method and optimal regularization parameter strategy. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 2016, 30(1), 67-88. [CrossRef]

- Samadi, F., Woodbury, K., Kowsary, F. Optimal combinations of tikhonov regularization orders for ihcps. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 2021, 161(000), 106697. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Zhang, P., Wang, Y., Sun, C., & Xia, X. Real-time identification of severe heat loads over external interface of lightweight thermal protection system. Thermal science and engineering progress 2023, 37. [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J. I., Chen, H.. Analytical developments and experimental validation of a thermocouple model through an experimentally acquired impulse response function. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2019, 141, 1301-1314. [CrossRef]

- J.-G. Bauzin, M.-B. Cherikh, N. Laraqi, Identification of thermal boundary conditions and the thermal expansion coefficient of a solid from deformation measurements, Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2021, 164, 106868. [CrossRef]

- Farahani, S. D., Kisomi, M. S. Experimental estimation of temperature-dependent thermal conductivity coefficient by using inverse method and remote boundary condition. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer 2020, 117, 104736. [CrossRef]

- Z.-Y. Zhou, B. Ruan, et al. A new method to identify non-steady thermal load based on element differential method, Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 213, 124352. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. C., Chen, H. C., Qi, L., Wu, Z. Calibration Method for Inverse Heat Conduction Problems Under Sensor Delay and Attenuation. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 2025, 39(3), 595-606. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A., Zafar, S. Ann based direct modelling of t type thermocouple for alleviating non linearity. Communications in Computer and Information Science2020, 1229. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J., Wang, L. Nonlinear system modeling and application based on restricted Boltzmann machine and improved BP neural network. Appl Intell 2021, 51, 37–50. [CrossRef]

- Dai, H., Shang, S. P., Lei, F. M., Liu, K., Zhang, X. N., Wei, G. M., Xie, Y. S., Yang, S., Lin, R., Zhang, W. J. CRBM-DBN-based prediction effects inter-comparison for significant wave height with different patterns. Ocean Engineering 2021, 236, 10, 109559. [CrossRef]

- F. TIAN, C. YANG. Deep belief network-hidden markov model based nonlinear equalizer for vcsel based optical interconnect. Science China(Information Sciences) 2020, 63(06), 155-163. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang, Z. Chen, H. Chen, Z. Mao. Spatiotemporal-response-correlation-based model predictive control of heat conduction temperature field, J. Process Control 2024, 140, 103257. [CrossRef]

- S. Basir, I. Senocak, Physics and equality constrained artificial neural networks: application to forward and inverse problems with multi-fidelity data fusion, J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 463, 111301. [CrossRef]

- B. Moseley, A. Markham, T. Nissen-Meyer. Finite basis physics-informed neural networks(FBPINNs): a scalable domain decomposition approach for solving differential equations, Adv. Comput. Math. 2023, 49(4), 62. [CrossRef]

- H. Son, S.W. Cho, H.J. Hwang, (2023). Enhanced physics-informed neural networks with augmented Lagrangian relaxation method (AL-PINNs), Neurocomputing 548, 126424. [CrossRef]

- J. Bai, G.-R. Liu, A. Gupta, L. Alzubaidi, X.-Q. Feng, Y. Gu. Physics-informed radial basis network (PIRBN): a local approximating neural network for solving nonlinear partial differential equations, Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 415, 116290. [CrossRef]

- F. Sahli Costabal, S. Pezzuto, P. Perdikaris. Δ -PINNs: physics-informed neural networks on complex geometries, Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107324. [CrossRef]

- X. Jiang, X. Wang, Z. Wen, E. Li, H. Wang, Practical uncertainty quantification for space-dependent inverse heat conduction problem via ensemble physics-informed neural networks, Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 147, 106940. [CrossRef]

- K.-Q. Li, Z.-Y. Yin, N. Zhang, J. Li. A PINN-based modelling approach for hydromechanical behaviour of unsaturated expansive soils. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 169, 106174. [CrossRef]

- Fang, B. L., Wu, J. J., Wang, S., Wu, Z. J., Li, T. Z., Zhang, Y., Yang, P. L., & Wang, J. G. Measurement method of metal surface absorptivity based on physics-informed neural network. Acta Physica Sinica 2024, 73(9), 8, 094301. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, Q. Ren. A versatile inversion approach for space/temperature/time related thermal conductivity via deep learning, Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 186, 122444. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Liang, Y., Shang, Y. B., & Liu, D. H. Identification of ablation surface evolution using physics-informed neural network. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 167, 13, 109310. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., & Zhang, Z. Dynamic error correction of filament thermocouples with different structures of junction based on inverse filtering method. Micromachines 2020, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. Z., Liu, B. D., Xu, P. C., & Wang, P. Y. Influence of protection tube on thermocouple effect length. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2021, 26, 11, 101178. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., & Zhang, Z. Inverse filtering method of bare thermocouple for transient high-temperature test with improved deep belief network. IEEE Access 2021, PP(99). [CrossRef]

| p value | 0.25mmbutt-welded | 0.25mmball-welded | ||||

| Peak value (°C) | Infrared value (°C) | RE% | Peak value(°C) | Infrared value(°C) | RE% | |

| 1 | 790.0 | 878.6 | 10.1 | 783.8 | 865.2 | 9.4 |

| 3 | 831.3 | 5.4 | 814.0 | 5.9 | ||

| 7 | 858.1 | 2.3 | 852.3 | 1.5 | ||

| Junction | Average peak temperature (°C) | Average Infrared temperature (°C) | Peak relative error (%) | Risetime improved(ms) | R2 |

| 0.25mm butt-welded | 858.4 | 864.9 | 0.75 | 11 | 0.947 |

| 0.25mm ball-welded | 857.1 | 869.4 | 1.41 | 31 | 0.924 |

| 0.38mm butt-welded | 847.1 | 859.8 | 2.06 | 11 | 0.925 |

| 0.38mm ball-welded | 850.9 | 868.9 | 2.07 | 31 | 0.916 |

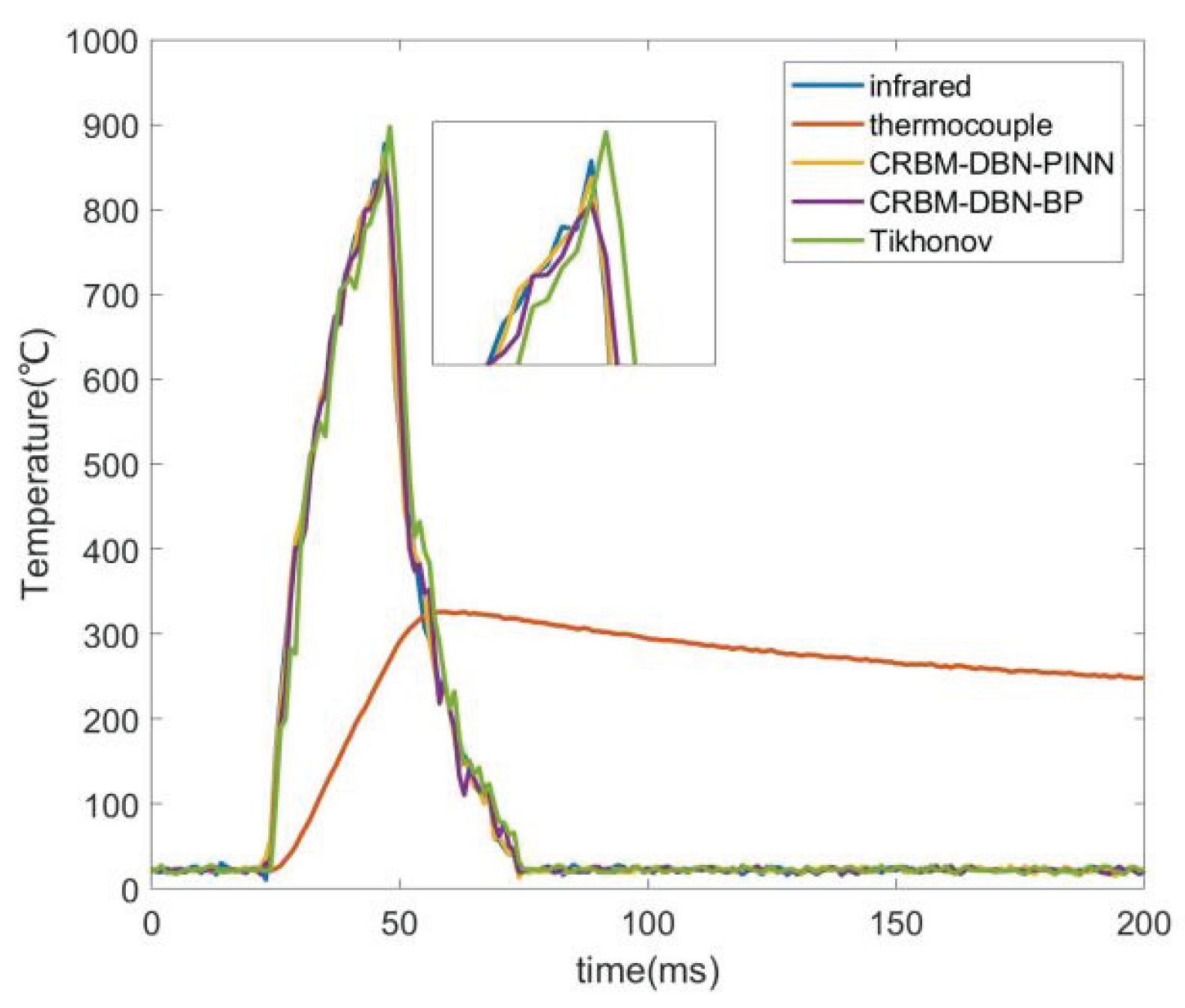

| Correction algorithm | Average peak temperature (°C) | Averageinfrared temperature (°C) | Peak relative error (%) | Risetime improved(ms) | R2 |

| Tikhonov | 897.4 | 877.5 | -2.2 | 10 | 0.833 |

| CRBM-DBN-BP | 859.5 | 2.05 | 12 | 0.902 | |

| CRBM-DBN-PINN | 870.2 | 0.83 | 12 | 0.948 |

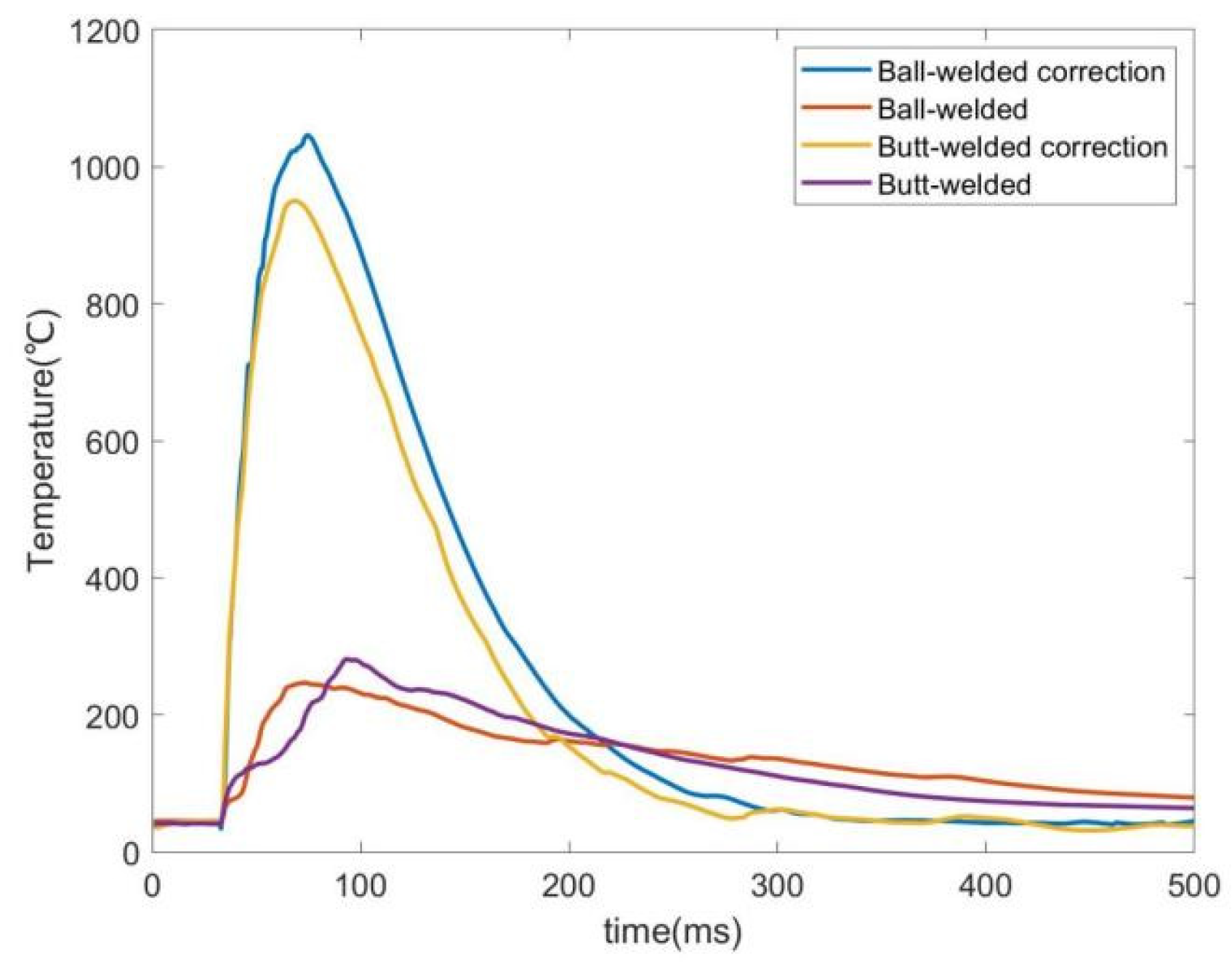

| Junction | Original peak (°C) | Corrected peak (°C) | Theoretical peak (°C) | RE% (original and theoretical) | RE% (revised and theoretical) | Risetime improved(ms) |

| Ball-welded | 273.4 | 949.9 | 1103.1 | 75.2% | 13.7% | 26 |

| Butt-welded | 246.5 | 1045.7 | 77.7% | 5.1% | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).