1. Introduction

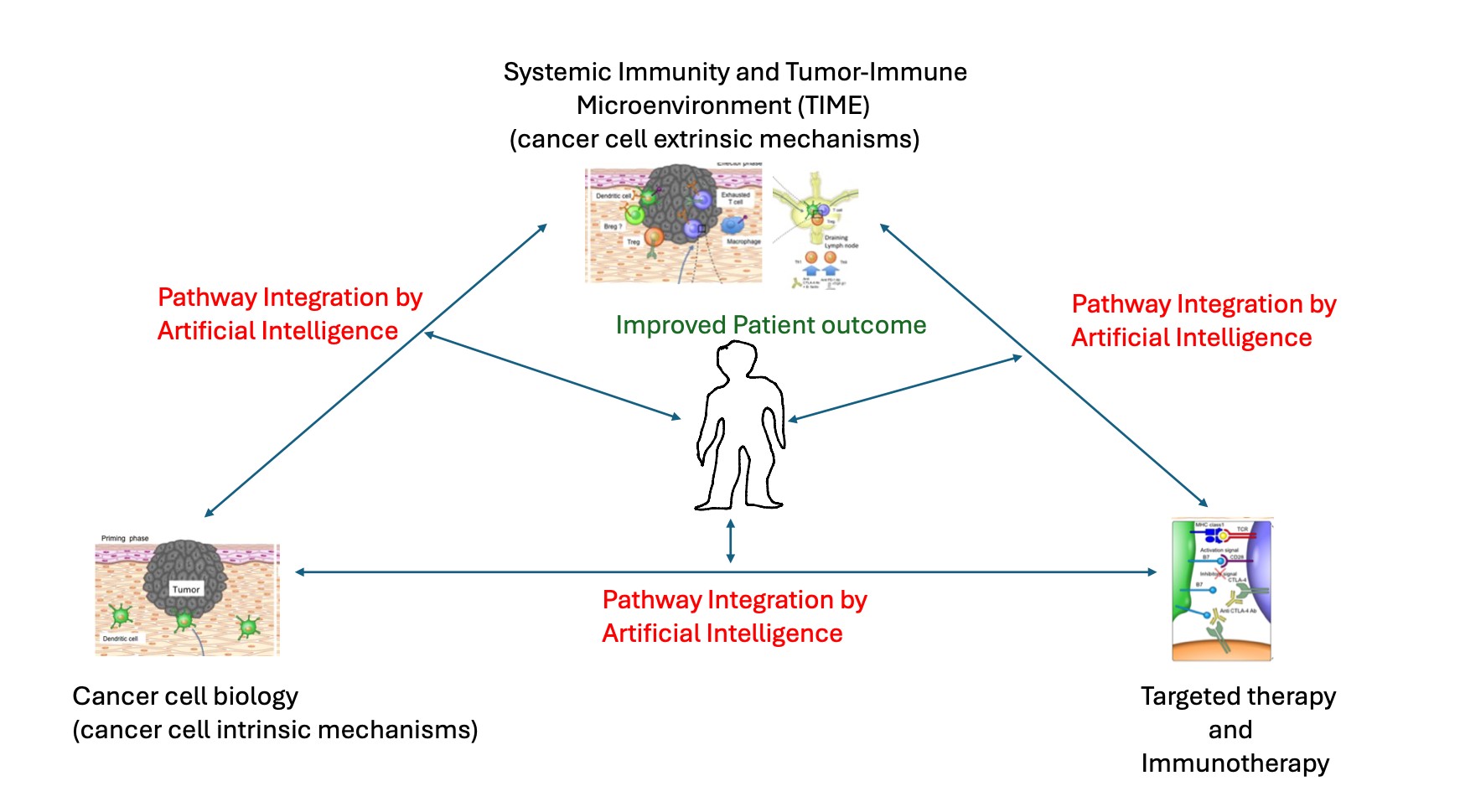

Advances in cancer cell biology, the systemic and tumour immune microenvironment, and precision cancer therapy have led to significant progress in patient outcomes. Together, they are the preeminent determinants of cancer clinical management. Current strategies in precision oncology can be organized thematically around this triad of biological processes. They contribute in distinctive ways to the outcomes in cancer patient care. At the same time, a highly dynamic cellular and molecular cross-talk occurs between them, modulating and altering their molecular and cellular processes in a pro- or anti-cancer manner. The directional shift resulting from the imbalance between these processes drives cancer progression and ultimately determines disease outcome and treatment effectiveness.

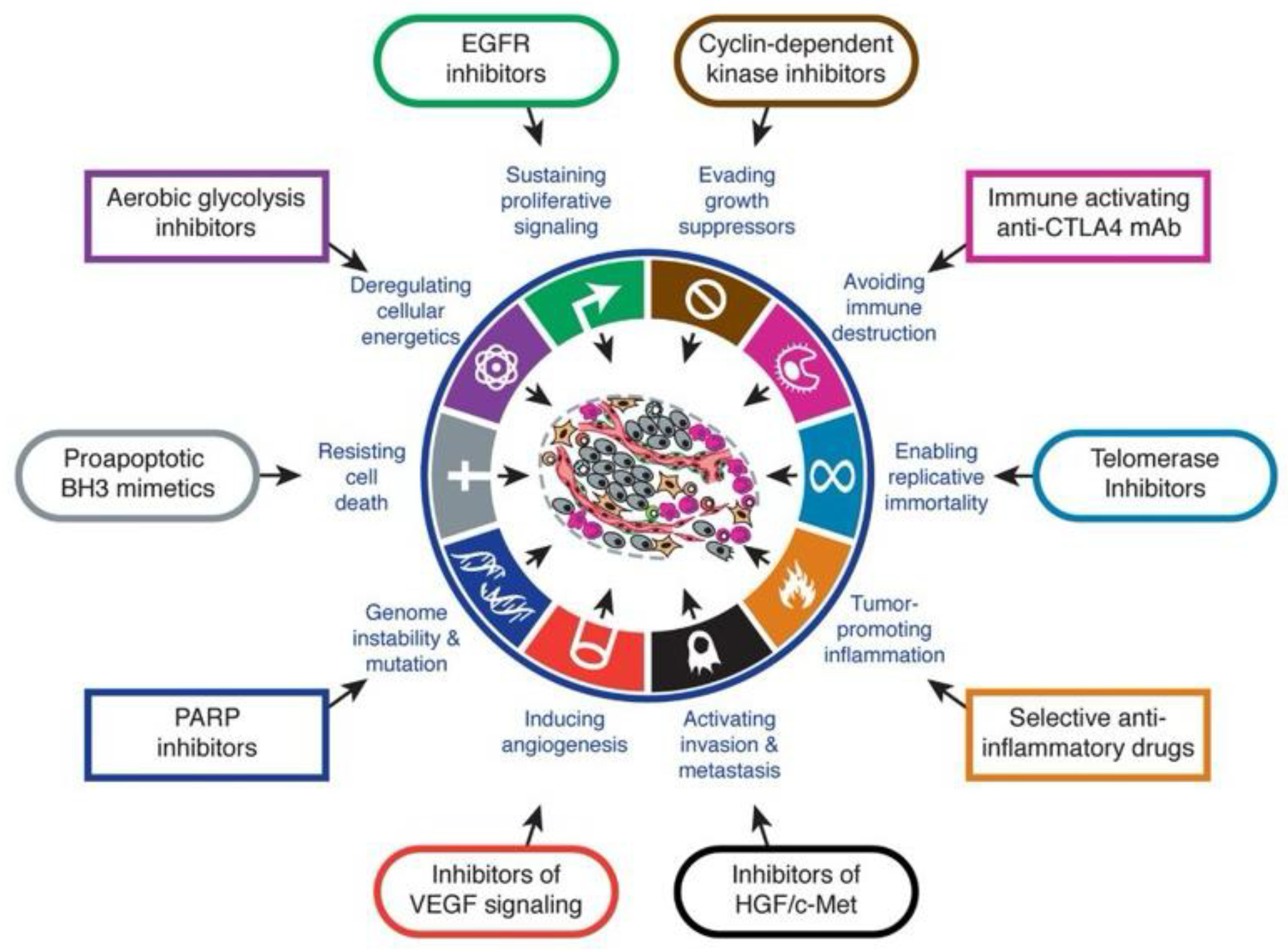

Over the past few decades, substantial progress has been made in elucidating the molecular underpinnings that promote these processes, leading to a redefinition of cancer. Traditionally understood as an evolving genetic disease of dysregulated cellular and molecular clonal processes, driven by the progressive accumulation of genetic, genomic and epigenomic, transcriptional alterations, Hanahan and Weinberg, surveying progress in the field, expanded and conceptualized this definition into a comprehensive framework, which they termed the Hallmarks of Cancer[

1]. This framework has continued to grow to incorporate advances in the understanding of cancer development over the decades. The initial cancer hallmarks were predominantly cancer cell intrinsic or autonomous processes, that is, they described cellular and molecular mechanisms originating within the cancer cell. Since then, the framework has expanded to include non-autonomous or extrinsic cancer cell mechanisms, including the tumour microenvironment, the host immune system, and the microbiome [

2]. Mutations within the genome of the cancer cell hijack normal intrinsic cellular pathways including cell signaling, signal transduction, cell cycle and its regulation, DNA replication and repair and homeostasis, apoptosis and cellular energetics etc for its own advantage. The resultant gain-of-function or loss of function proffers a growth/survival advantage on the initial cancer cell clone or subsequent subclone promoting cancer cell dominance. The Cancer Genome Atlas has comprehensively catalogued mutations, gene expression, and epigenomic alterations that occur in many specific cancer types[

3,

4]. These alterations can be functionally classified and grouped into the specific cancer hallmarks they mediate[

5]. The knowledge of their functional significance have aided drug development that specifically target unique components of the hallmarks of cancer[

6]. Designated as targeted therapies, these agents have advanced the principle of personalized medicine, in which therapy is tailored in accordance with the specific alterations in the cancer genome, leading to more effective and less toxic outcomes[

7]. Cancer molecular diagnostics is well established in identifying druggable targets, particularly with the wide implementation of Next-Generation sequencing[

8]. Of the identified hallmarks of cancer, some categories e.g. avoiding immune destruction, angiogenesis, microbiome, tumour-promoting inflammation etc., illustrate the importance of cancer cell extrinsic mechanisms to cancer evolution and progression[

2,

9]. The advent of highly successful immunotherapeutic strategies, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors, in a wide variety of cancer types, highlights the growing clinical relevance of these hallmarks[

10]. And the need to incorporate them in cancer molecular diagnostics and therapeutics prediction. Similar to cell intrinsic features of the cancer cell, these cancer cell extrinsic hallmarks demonstrate high complexity. For instance, the immunobiology of cancer is highly complex in its cellular constituents, bioactive molecules and molecular mechanisms[

10]. It is frequently defined by the specific cancer context. It is patient-specific, and it is highly dynamic. Elucidating its mechanisms and applying this in a patient-specific context within a clinical setting is a necessary goal of personalized medicine[

11]. These advances pose a new challenge for molecular diagnostics in the context of personalized medicine. This review aims to conceptualize molecular diagnostics with the framework of the hallmarks of cancer. This approach illustrates the challenges of translating advances into the clinical laboratory. The review discusses novel approaches and expert opinions on how to meet these challenges. The need for a comprehensive, multi-modal platform that can incorporate advances in cancer genomics, immunobiology and other hallmarks of cancer into diagnostic precision oncology is dissected. The emerging tools of machine learning, computational biology and artificial learning will facilitate the integration of the large body of information generated into actionable knowledge (

Figure 1).

In summary, the molecular mechanisms of lung cancer, their diagnostic and targeted therapeutic approaches are categorized into the cancer hallmarks. The complex interplay between the categories shows how novel prognostic, predictive and therapeutic approaches may arise using an integrative approach. The new age of bioinformatics, machine learning and artificial intelligence makes integrative and predictive information ripe for clinical utility.

3. Cell Intrinsic Molecular Mechanisms of NSCLC and Targeted Therapy

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), cancer cells acquire the property of unrestrained growth from persistent stimulation through several mechanisms, including the accumulation of random mutations. This is the hallmark of cancer that sustains proliferative signalling. Constitutively activating mutations liberate cancer cells from the controlled and synchronized growth of normal tissue or growth homoestasis. Growth-promoting signaling pathways that undergo aberrant perturbation in NSCLC include RAS-RAF-MAPK pathway, PI3K-protein kinase B (Akt) and mTOR Pathway[

5]. These perturbations result from upstream constitutionally activating mutations in genes within these pathways. NSCLC-specific oncogenes include EGFR, ERBB2, MYC, KRAS, BRAF, MET, CCND1, CDK4, ALK fusion, BCL2, NTRK fusions, ROS1 fusions, and RET fusions, among others[

13]. These driver oncogenes present as targets for kinase inhibitor therapy. Many small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) against lung cancer oncogenes have received FDA approval or are undergoing clinical trials. Examples include 1

st, 2

nd and 3

rd generation EGFR TKI (gefitinib, Erlotinib, Afatinib, Osimertinib); TKIs against ALK fusion, ROS1 fusion and MET amplification (Crizotinib); RET (

Selpercatinib, Pralsetinib); KRAS (adagrasib, Sotorasib); BRAF(Vemurafenib); HER2 (Pyrotinib), etc.[

6]

NSCLC utilizes the cancer hallmark of evading growth suppressor as a tumorigenic mechanism through resisting inhibitory signals. NSCLC acquire mutations in tumour suppressor genes (TSG), including the central gatekeepers, such as TP53 and RB1. In fact, TP53 is one of the most frequently occurring mutations in NSCLC. Mutations in TSG confer a growth advantage on NSCLC tumour cells. TP53 coordinates intracellular signals and modulates multiple processes like cell-cycle progression, and apoptosis [

14]. RB transduces extracellular signals and relays these processes to cell growth and proliferative processes like the cell cycle[

15]. These two genes act in concert with a network of other genes, resulting in functional redundancy. Other evasive mechanisms in growth suppression include loss of contact inhibition, due to the failure of cell-surface adhesion, mediated by genes like CDH1 (E-cadherin) and NF2 (Merlin)[

16]. The epithelial polarity gene LKB1 acts to maintain tissue integrity and epithelial structure organization[

17]. In NSCLC, mutated genes that function as tumour suppressor genes include TP53, RB1, STK11, CDKN2A, FHIT, RASSF1A and PTEN[

18]. TP53 has proved a difficult gene for therapeutic targeting. Potential therapeutic approaches that target this gene include p53 gene therapy [

19], pharmacologic restoration of p53 function[

20], MDM2 inhibition[

21], etc. Indirect approaches use TP53 co-mutation status to inform different therapeutic strategy, including combination of EGFR-TKIs with chemotherapy, anti-angiogenic drugs, or with immunotherapy [

22].

Apoptosis and autophagy are major mechanisms in NSCLC for coordinated cell death and anti-tumour activity[

23]. Apoptosis is attenuated in cancer cells and plays an important role in progression to high-grade malignancy and therapy resistance[

24]. Genetic alterations that alter the apoptotic machinery include the BCL-2 gene family, DNA-damage sensors including TP53 via Noxa and Puma proteins, MYC and others [

25]. Autophagy is a system for recycling and degrading damaged cellular organelles or cytoplasmic contents[

26]. The cancer cells upregulate this process to overcome microenvironmental stress and support proliferation. Signalling pathways that NSCLC cells utilize to recruit the autophagic circuitry for their benefit include PI3-kinase, AKT, and mTOR pathways[

27]. The BCL family of genes interact with the autophagic pathway through beclin-2. Apatinib is a small molecular anti-angiogenic drug undergoing clinical trials that triggers autophagic and apoptotic cell death in lung cancer. It upregulates Cleaved caspase 3, cleaved caspase 9 and Bax, and downregulates Bcl-2 in NSCLC cells [

24].

Genomic instability is a characteristic oncogenic mechanism in NSCLC. Impairing genomic integrity and surveillance machinery enhances the multistep accumulation of mutations that confer competitive advantage on NSCLC subclones. This machinery acts to detect and activate the DNA damage repair processes and cellular mechanisms that intercept or inactivate genotoxic products. Their mechanism of action is similar to caretaker genes, which act like tumour suppressor genes. An important player in this process is the enzyme telomerase, a key gene in the maintenance of the DNA ends called telomeres[

28]. The loss of telomeric DNA contributes to karyotypic instability and genomic alterations like amplification and deletion of chromosomal segments[

29]. Copy number changes can be detected by genomic methods including comparative genomic hybridization and next generation sequencing[

30]. In NSCLC, these genomic changes include specific allelic loss at 3p, 4p, 9p and 17p. Copy number alterations results in amplification of MYC, RAS, EGFR, NKX2-1,ERBB2, SOX2,BCL2, FGFR2 AND CRKL; and inactivation of RB1, CDKN2A, STK11 AND FHIT[

18]. Homologous Recombination repair-Deficiency (HRD) testing is an predictive assay for PARP inhibitors[

31]. It assesses genomic instability arising from mutations in HRD genes by assessing loss of heterozygosity (LOH)[

32], telomeric allelic imbalance (TAI)[

33] and large-scale transitions (LST) as well as mutations in BRCA1/2 genes and other HRD genes[

34]. It is widely used clinically in ovarian cancers. Clinical trials are evaluating its utility in NSCLC as well[

35].

The cancer hallmark of activating invasion and metastasis is a key mechanism in the progression of early-stage curable lung cancer to late-stage disease with distant metastasis. Often called the Invasion-metastasis cascade, a serial acquisition of mutations enable cell-cell detachment, enzymatic lysis of the extracellular matrix, then migration and intravasation into nearby blood and lymphatic vessels [

36]. After transit in the circulation, extravasation into the parenchyma distant tissue leads to micrometastasis. Colonization occurs when the cancer cells establish viable, growing lesion. Cancers cells reengineer an embryonic program in a process called Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) to initiate and facilitate this process [

37]. At emergence in distant tissue and with colonization, the cancer cells revert the processes via the process of Mesenchymal to Epithelial Transition (MET)[

38]. In lung cancer, pathways and genes associated with the EMT include COX-2, LKB1,

WNT, NOTCH, TGFβ, PI3K-Akt, and JAK-STAT pathways.

NSCLC utilizes the Induction of angiogenesis in its growth and progression. Unlike normal adult tissue, in which transient angiogenesis occurs only as part of the wound healing process or in female reproductive cycling, cancer cells permanently activate an angiogenic switch, leading to neovascularization that sustains the expanding tumour [

39]. Inducers of this process include well-characterized proteins like vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGFR), proangiogenic signals, e.g. fibroblast growth factors (FGF). Other factors that promote angiogenesis in lung cancer include EGF, FGF-2 and HIF[

40].

Normal cells have limited growth and division cycles after which senescence or cell death occurs. However, in NSCLC, cells escape this restriction and acquire replicative immortality. The enabling of replicative immortality in NSCLC is a hallmark of cancer. This mechanism occurs through the activation of the enzyme, telomerase. Telomerase typically functions to maintain telomere length. Alterations in its function promote cancer cell immortality and enhance tumorigenesis in NSCLC [

41]. Implicated mechanisms include the accumulation of mutations in the context of impaired caretaker gene functions, and other non-telomeric functions e.g., DNA-damage repair, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. High telomerase activity is associated with advanced diseases in NSCLC. Strategies targeting telomerase include antisense oligonucleotide against human telomerase RNA and immunotherapy[

42,

43]. Explanatory models for replicative immortality include genetic diversity from clonal evolution, cancer stem cell adaptability and cancer cell plasticity[

44].

The unregulated and excessive growth of NSCLC cells alters energy metabolism in response to increased demand for fuel and nutrients [

45]. This hallmark of cancer, deregulating cellular energetics, results in a metabolic reprogramming that switches energy metabolism to predominantly glycolysis, even in the presence of oxygen. Aerobic glycolysis is facilitated by the upregulation of the glucose transporter, GLUT1, and the glycolytic pathway. Lung cancer oncogenes, e.g RAS, MYC, TP53 play a mediatory role. Gain-of-function mutations in IDH 1/2 are implicated in cancer cell energy metabolism [

46]. Evidence suggests they arise by clonal selection for their biochemical property to alter energy metabolism.

The altered epigenome of NSCLC cells facilitates tumour heterogeneity, unrestrained self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation[

47]. These features are related to the stem-ness seen in cancer cells and present a major challenge to cancer therapy through the development of treatment resistance. Epigenetic reprogramming occurs through mechanisms including DNA methylation, histone modification by methylation and acetylation, and the action of non-coding RNA including microRNA, pi-RNAs,circRNAs and other sncRNAs. DNA methylation is mediated by genes such as DNMT family of methyl transferases,

UHRF1 and TET[

48]

. MicroRNAs implicated in lung cancer regulation include tumour inhibitory forms e.g.

let-7 miRNA that regulates NRAS, KRAS, MYC AND HMGA2. Others include miR-29a/b/c, miR-34-a/b/c, miR-16 etc [

49]. Oncogenic miRNAs enhance cancer development by promoting cell proliferation and antagonizing apoptosis. Examples include the miR-17-92 cluster, which targets PTEN, E2F1-3, and BIM, miR-21, miR-93, etc. [

50]. MicroRNAs are potential prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers in lung cancer [

49]. In NSCLC, distinct methylation patterns differentiate smokers from nonsmokers. In smokers, high promoter methylation of p16, MGMT, RASSF1, MTHFR, and FHIT occur at high frequency, while methylation profiles in RASSF2, TNFRSF10C, BHLHB5 and BOLL are more commonly observed in nonsmokers [

18]. Since epigenetic modifications are reversible and can be altered by pharmacological agents, they present a potential therapeutic target in cancer treatment. Epigenetic drugs have been approved by the FDA, predominantly in hematologic malignancies, e.g. Azacitidine (MDS), Decitabine (MDS), Romidepsin (Cutaneous T cell lymphoma), etc . In NSCLC, DNMT inhibitors and HDACs are being explored for their benefits in lung cancer [

51]. DNA methylation detection may also provide ways of early detection of early-stage NSCLC in tissue and plasma [

52].

In NSCLC, loss-of-function TP53 mutations may play a role in oncogene-induced senescence, thereby promoting tumorigenesis [

53]. Senescence is a physiologic response to cellular stress characterized by stable cell cycle arrest and release of damage signals of pro-inflammatory factors e.g. chemokines, cytokines, growth factors, proteases [

54]. While acute senescence is considered anti-tumoural, chronic senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) promotes many hallmarks of cancer and facilitates a microenvironment favourable to tumour development. TP53 induces cell senescence via p21. Advances in the understanding of this process will enable treatment strategies that combine pro-senescence treatments with senolytic or senomorphic agents e.g. the HDAC inhibitor Panobinostat, which have been shown to possess senolytic effects in senescent cancer cells [

55].

Tumour cell plasticity is a cancer hallmark seen in NSCLC. The cytomorphologic features of NSCLC, e.g. adenocarcinoma vs squamous cell carcinoma, its state of differentiation e.g. well-differentiated to poorly differentiated, is a result of tumour plasticity. Phenotypic plasticity is an adaptive response to environmental changes that cancer cells acquire and deploy to maintain a fitness advantage by modifying their phenotypic traits [

56]. These phenotypic adaptations, including metastatic competency, immune evasion, and treatment resistance, mitigate anti-cancer processes and arise throughout the course of cancer development and evolution. Genetic and non-genetic mechanisms, such as epigenetic modifications of the genome, underlie mechanisms of phenotypic switching. Cancer cells may undergo transdifferentiation, blocked differentiation or dedifferentiation in response to environmental cues. In the process, the cancer cells take on a phenotypic state that is conducive to growth and survival [

57]. The molecular and cellular mechanisms of cancer phenotypic plasticity are complex and diverse. Some are repurposed processes in normal development and wound healing.

Understanding the underlying mechanisms will uncover potential targets against shape-shifting cancer adaptive processes that underpin the inevitability of cancer progression [

44]. Transdifferentiation in lung cancer may occur through the

dysregulation of pathways that promote or suppress plasticity. Upregulated pathways during transdifferentiation include the cell cycle/DNA damage repair pathways, genes in the PRC2 complex, the AKT pathway, and the Wnt pathways. Down-regulation pathways include antitumor immune response pathways [

58]

. Dedifferentiation may be mediated by HIF1 alpha and HIF2 alpha via SOX2 and Oct4 [

59]. Other studies in lung cancer show that the epigenetic switch between SOX2 and SOX9 is a potential regulator of cancer plasticity and progression [

60]. Amplification of SOX2 is also implicated in squamous cell carcinoma phenotype [

61].

4. Cell Extrinsic Molecular Mechanisms of NSCLC and Immunotherapy

The tumour immune microenvironment (TIME) is an ecosystem of diverse cells, engineered by the interplay of the growing cancer cell and the immune system[

62]. Three important cancer hallmarks arise from the TIME include tumour-promoting inflammation, the polymorphic microbiome and immune evasion. All three play an important role in NSCLC.

The innate Immune cells consisting of cells such as neutrophils, eosinophils, macrophages, mast cells, and myeloid derived suppressor cells, exhibit both tumour promoting and anti-tumour effects through the production of numerous bioactive molecules including growth factors, survival and angiogenic factors, extracellular matrix proteases that aid invasion, metastasis and facilitate other cancer hallmarks. Macrophages are important tumour associated inflammatory cells. Traditionally categorized as M1 (classical) and M2 (Tumour-promoting), macrophage classification has evolved to account for the

macrophage phenotypic diversity, resulting from differing ontogeny and local stimuli[

63]

. They promote survival, development and tumour dissemination via processes like angiogenesis, EMT and immunosuppression[

64]. Factors such as interleukin (IL-1) and TNF-alpha lead to the activation of the NF-kB and STAT3 pathways, which not only induce tumour-forming mutations and produce a self-sustaining cycle that maintains the tumour inflammatory microenvironment. Inflammatory factors associated with lung cancer include IL-1Beta, IL-4, IL-6, IL-11, IL-12, TNF-alpha, MCP-1 and TGF-Beta.

The polymorphic microbiome is a diverse community of resident microorganisms on barrier tissue, particularly the gastrointestinal system, lung, breast and urogenital system. They have an important role in cancer development and progression. Their effects may promote or impede the acquisition of cancer hallmark characteristics. Their emerging importance in NSCLC is only beginning to be understood. Oral taxa e.g. Streptococcus, Veillonella etc dominate the lower airways of NSCLC patients[

65]. Tumour promotion can occur through mutagenesis by genotoxic bacterial toxins, and other biomolecules. They may act directly, through DNA damage or by disrupting genome repair mechanisms. An example is the E. Coli PKS locus, which is mutagenic to the human genome [

66]. They may also mimic receptor agonists that stimulate epithelial proliferation through pathways such as ERK, PI3K and MAPK[

65]. The microbiota interacts with various cellular and physiologic processes including the adaptive and innate immune system, cellular energetic and metabolism, histone modification, cell-cycle progression, modulating their cancer activity [

67]. In NSCLC, the composition of intestinal flora may be a predictive factor for the selection of immunotherapy[

68].

The understanding of the Immune evasion in NSCLC, a critically important cancer hallmark, has led to advances in therapeutic modalities. Oncogenic mutations occur at a constant rate in normal human cells despite cellular mechanisms to prevent or correct errors during DNA replication. The three systemic processes whereby immunity interacts with cancer development have been extensively studied [

69]. These are:

1. Immune surveillance

2. Immunoselection

3. Immunosubversion

Immunosurveillance is the process whereby systemic immunity detects and destroys cancer precursors before they develop and become clinically apparent. Immunoselection (immunoediting) refers to the emergence of non-immunogenic tumour cell variants as a result of cytotoxic selective pressure. Immunosubversion is the active suppression or hijacking of systemic immunity for the cancer cell’s growth advantage. These three processes highlight a tiered system of active interaction or cross-talk between the cancer cell and the immune system. A dynamic balance is usually maintained. Its disruption leads to progression to the next phase. Thus, failure in elimination (immunosurveillance) results in an equilibrium during which immunoselection favours an advantaged clone. After this, escape and hijacking of the immune system (immunosubversion) lead to overt cancer.

Immune cross-talk between the cancer cell and systemic immunity and the tumour immune microenvironment occurs in a specific and highly choreographed manner [

70]. As the cancer cell harnesses specific hallmarks or cell intrinsic mechanisms to promote its malignant efficacy, the same mechanism may also influence the systemic or microenvironment immunity in a cell extrinsic way to potentiate the cancer-promoting effect of the hallmark. For instance, aberrant JAK-STAT signaling leads to uncontrolled proliferation. However, it also acts on the immune system via interleukin 6 to inhibit the inflammatory response [

71].

The cycle of activation and response of cellular immunity against malignant cells by T cells occurs through a series of site-specific stages called the immune cycle [

72]. Tumour antigens (neoantigens) at the tumour microenvironment are released into the lymphatic system on cancer cell death. At this stage, interaction occurs with antigen-presenting cells (APC) and the antigens are processed and presented on the cell surface in the context of the MHC class I molecule. An encounter of APC with T-cells leads to priming and activation mediated by specific T-cell receptor antigen binding that is facilitated by the MHC class I molecule and other costimulatory molecules, such as B7. The activated T cells are trafficked through the vasculature back into the tumour microenvironment, where antigen recognition and tumour cell killing occurs. A cast of important proteins play critical role in this process. Our focus is on two primary immune checkpoint molecules, PD-1 and CTLA-4.

PD-1 (programmed death -1) is a cell surface receptor that binds to its ligand PDL-1, also a cell surface molecule [

73]. Binding of PD-1 to PDL-1 impairs TCR signaling and T cell activation. PD-1 is expressed on T-cells, B-cells, myeloid and NK cells. PD-L-1 is expressed on hematopoietic, antigen-presenting cells and non-hematopoietic cells [

74].

CTLA4 (Cytotoxic T-lymphoctye associated protein 4) is a costimulatory protein receptor for the T-cell receptor (TCR) and is expressed on regulatory T-cells and activated T-cells. It binds competitively with CD28 to the ligands B7.1 and B7.2 and suppresses T cell response.

PD-1/PDL1 and CTLA4 facilitate central and peripheral tolerance of systemic immunity (

Figure 3)[

75]. They promote negative selection of self-recognizing lymphocytes in primary and secondary lymphoid organs. They also act in the process of immune exhaustion. Immune exhaustion refers to progressive effector T cell impairment arising from persistent antigen encounter. This mechanism occurs as a normal physiologic process to mitigate against tissue destruction from chronic infections. Immune exhaustion also occurs to regulate the anti-cancer response. Within the context of cancer progression, the cancer cell exploits the normal PDL-1 function as an immune evasion mechanism.

PD-1/PDL1 and CTLA4 show similarities and differences in their roles in checkpoint inhibition. Both act against autoreactive T cells and to foster T-cell impairment. CTLA-4 function occurs at the initial priming stage of naïve T cell activation. The site of its function is primarily at the lymph nodes. It binds mainly to costimulatory molecules on professional APC, e.g. B7, leading to its sequestration and diminution of its TCR stimulatory function as well as other possible immune inhibitory roles through Treg cells. PD-1 regulates previously activated T cells at a later effector phase in the T cell cycle. PD1/PDL-1 activity occurs within peripheral tissue. PD-1 binds to several ligands, which may be expressed by immune and non-immune cells, including PDL-1/PDL-2 activates signaling leading to reduced T cell activation.

PDL1 expression occurs in a wide variety of cancers. It is expressed in 20-30% of NSCLC, 24-49% of melanoma, 70% of epithelial ovarian cancers, 20% of triple negative breast cancer, at various rates in gastrointestinal malignancies, including 5% of colorectal cancer, 11-30% of cholangiocarcinoma, as well as diverse tumours such as head and neck, urothelial carcinoma etc.

4.1. Immunotherapy in Cancer

Like targeted therapy against driver mutations in cancer, the immune system offers an increasing menu of therapeutic modalities. Various modalities have been studied and implemented in harnessing the immune system as an anticancer strategy. The most promising include immune checkpoint blockade, therapeutic cancer vaccines, bi-specific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) and adoptive cell therapies (ACT) [

76].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors: ICI acts by blocking the interaction of inhibitory surface receptors of T-cells (PD-1/PDL-1, CTLA4) and their cognate ligands. This blockade leads to an increase in T cell activation and proliferation, enhancing anti-tumour activity. Numerous immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have been approved or are in late phase of clinical trial development. These include anti-CTLA-4 inhibitors (Ipilumumab and Tremelimumab) and anti-PD1(Pembrolizumab, Nivolumab) and anti-PDL-1 drugs (Durvalumab and Atezolimab). These drugs show activity against a wide range of cancers, including NSCLC, melanoma, kidney, prostate, pancreatic, cervical, colorectal, ovarian, urothelial, glioblastoma, head and neck, hematologic malignancies, etc.

Therapeutic cancer vaccines (TCA): TCA deliver tumour antigens to the systemic immunity and elicit an anti-tumour endogenous T cell response. The antigens delivered may be common to several cancer types, as a result of shared mutant variants of oncogenes e.g. KRAS, TP53, or personalized neoantigens specific to a patient’s cancer. Antigen delivery methods include injection of naked or encapsulated DNA, RNA, or peptide, irradiated tumor cells, genetically modified autologous tumour cells that secrete immune activating proteins, e.g. HLA antigens etc. Sipuleucel-T is an FDA approved dendritic cell vaccine therapy for metastatic, castration resistant prostate cancer [

76].

bi-specific T-cell engagers (BiTEs): These are recombinant proteins consisting of two distinct single-chain variable fragments linked by a short sequence. One fragment binds T cell activating molecular e.g. CD3, while the other targets a tumour-associated antigen (TAA). Synchronous binding of the pair to their targets induces T-cell activation, and ultimately tumour cell destruction. The versatility of BiTes lies in its adaptability to any cell surface TAA. Its use is predominantly in hematologic malignancies.

Adoptive cell therapies (ACT): ACT is the infusion of genetically engineered or tumor-infiltrating T-cells, after ex vivo expansion, as therapy against tumor cells. They may be modified to express a transgenic TCR or a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that on tumour antigen binding, elicit a cytotoxic effect. CAR-T cells are target-versatile and MCH-independent. Thus far, they have found greater efficacy in hematologic malignancies than in solid tumours. Factors such as tumor heterogeneity, low lymphocyte penetration and the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment limit their effectiveness in solid tumours. Other cells types may be used in ACT, including cytokine-induced killer cells (CIK), cascade-primed cells (CAPRI), etc [

11].

Antibody Drug Conjugates: This represents a class of therapy in which a monoclonal antibody is chemically linked to a cytotoxic drug. ADCs combine the specificity of tumour antigen-targeting antibodies with the toxicity of chemotherapy. ADCs also effect cytolysis through mechanisms like immunogenic cell death, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and dendritic cell activation [

77].

Cytokine therapy: Cytokines are important regulators of the immune system through their paracrine and autocrine effects. They are actively being investigated in clinical trials as combinatorial agents. They may have potential therapeutic roles with checkpoint inhibitors and other immunotherapies in potentiating the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) of these therapies through their immunomodulatory effect [

78].

Oncolytic Viruses: Oncolytic viruses facilitate tumour lysis by selectively replicating within tumours and activating cytolytic and immune mechanisms for tumour destruction. These category of immunotherapy is still undergoing active develop and clinical trials with promising initial results [

79]). Thus far, only Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) has received FDA approval. T-VEC is a herpes simplex virus for advance melanoma. After tumour infection and replication, it synthesizing granulocyte macrophage colony factor to facilitate antitumour response in melanoma [

80].

Immunotherapy and synergy with Immunogenic cell death (ICD): ICD is a newly defined mechanism of tumour cell killing by therapeutic modalities including radiotherapy and chemotherapy. It is characterized by exuberant and extensive cell lysis with release of intra-tumour cell fractions, i.e. danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs); enhanced activation, uptake and presentation of tumour antigens by dendritic cells, increased cross-priming and proliferation of tumour-specific cytotoxic T cells and production of tumour-specific antibodies [

77]. Eliciting the immunogenic response can serve as a means of transforming an immunologically cold tumour, otherwise insensitive to immunotherapy, into a hot and immunotherapy-sensitive cancer [

81]. This suggests a role of combinatorial strategies of ICD inducers with immunotherapy. ICD inducers include immunomodulatory agents such as Tumour Necrosis Factor receptor superfamily member 9 (TNFRSF9), CD40, immunostimulatory cytokines, immunomodulatory agents e.g., IDO1 and cancer vaccines. Numerous strategies are being evaluated in preclinical and clinical trials, including chemotherapy[

81], radiotherapy[

82], targeted anticancer therapy[

83], etc

4.2. Immune Subtypes in Cancer

The constitutional genetic variability in human immune system is a significant determinant of the composition of the tumour microenvironment and its immune response to the tumour. The vast field of immunogenomics aims to characterize the tumour-immune relationship, utilizing multiple approaches including Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, single cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics and bioinformatic technology and artificial intelligence [

84]. Immunogenomics also identifies predictive biomarkers for susceptibility to immunotherapy. Immunogenomics can classify cancers into immune subtypes based on immune cell type composition, function and response, giving prognostic and mechanistic information. The identification of cancer-immune cross-talk in different classes of immune subtypes may serve as potential targets of immunotherapy. Neoantigen prediction by computational methods can guide adoptive cell therapy and cancer vaccines [

84]. Multiple studies using diverse approaches demonstrate that immune subtypes can play a role in prognosis and guide treatment decisions. Immune subtypes may be based on specific cancer types or on several different types of cancer to identify broad themes and immune signatures that define the immune cell types. A comprehensive analysis of 10,000 tumours using the TCGA data identified six immune subtypes across 33 diverse cancer types [

85]. These subtypes were designated as wound healing, interferon- gamma, inflammatory, lymphocyte depleted, immunologic quiet and TGF-Beta dominant. Different Immune signatures were enriched in specific cancer types. For example, Wound healing was enriched in colorectal cancer and Rectal adenocarcinoma, inflammatory was enriched in kidney, prostate carcinoma. Overall survival was correlated with these signatures, demonstrating cross-talk between cell intrinsic and cell extrinsic process. The inflammatory signatures had the best prognosis, TGF-Beta had the least favourable prognosis, and the others fell in the intermediate range. Another TCGA study, using a cancer immunogram visualization approach across 32 cancer types, discovered four major cycle patterns that were characterized by “hot”, “cold”, “exhausted”, “inert” or “radical” features [

86]. These had prognostic and predictive capabilities for immune checkpoint inhibitors. The interplay between tumour and its microenvironment suggests that immune subtype may be unique and predictive for specific cancer types. Other studies looking specifically at lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) have developed different predictive models and classification systems. For instance, one study identified immunodeficiency and immunocompetent subtypes [

87]. The immunocompetent subtype displayed microenvironmental activation with a high expression of immune checkpoint genes. A different study classified LUAD into two prognostic subtypes, high-risk and low-risk [

88]. The high-risk group showed activation of cell cycle signaling and high frequency of TP53 mutations. The high-risk subtype was suggested to be more amenable to immune checkpoint blockade therapy than those with the low-risk subtype. A different study of a cohort of LUAD and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) identified three immune subtypes. This study suggested a potential role for sex differences in NSCLC and differential response to immunotherapy. A subtype appeared to respond better to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and/or combined antiangiogenic therapy than other NSCLC subtypes [

89].

4.3. Biomarkers for Immune Checkpoint Inhibition (ICI)

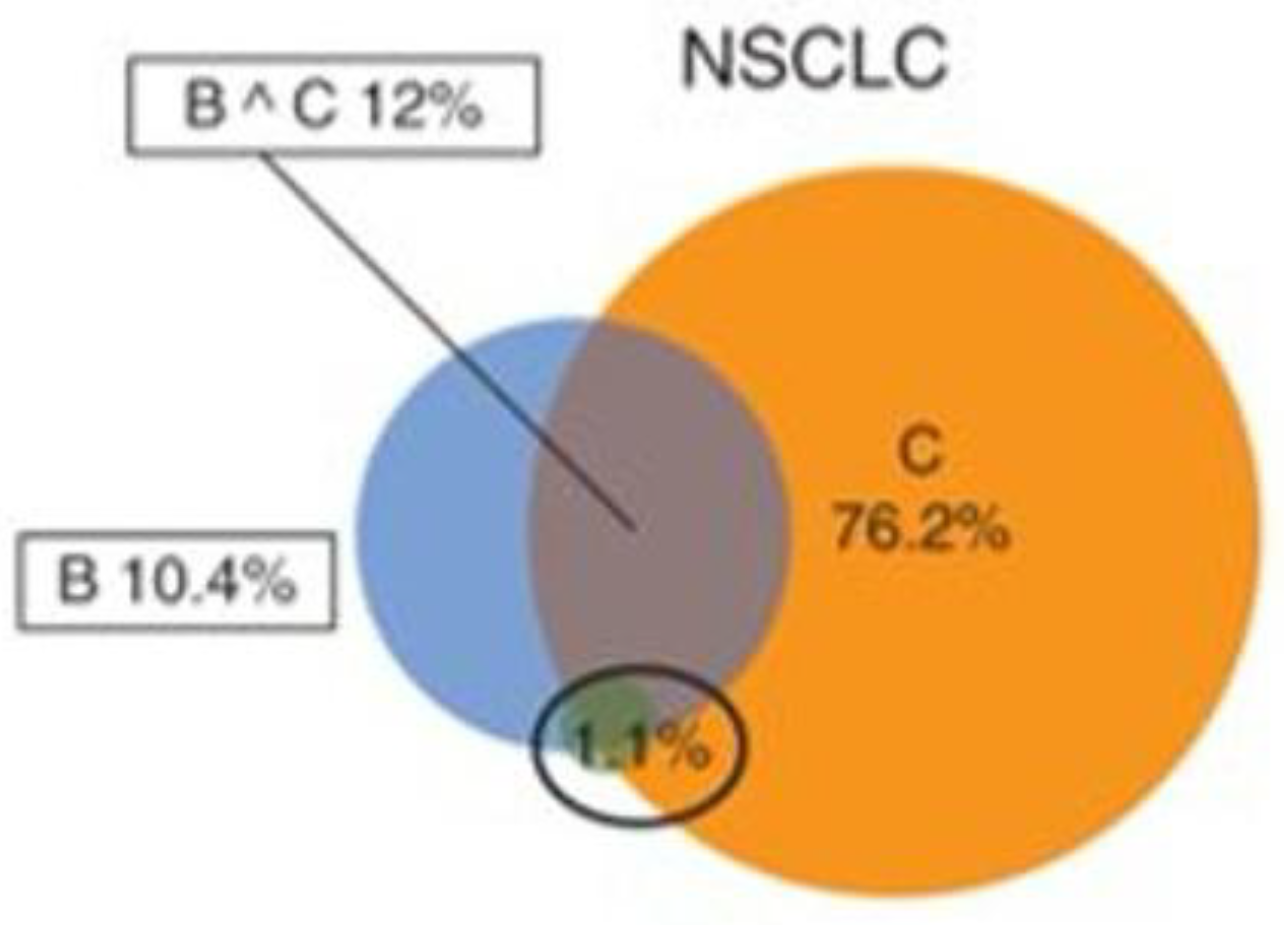

Despite the remarkable efficacy of ICIs in diverse types of cancers, widespread usage in treatment has encountered roadblocks. First, only a limited number of patients (12%) achieve a durable clinical benefit with monotherapy [

90]. There is also an increased risk of immune related drug toxicities, such as hyperprogression of tumour with worsened outcomes even in certain patients with clear indication [

91]. In addition to these, the high cost of these drugs requires judicious use only in cases with potential benefits. These factors demonstrate the necessity for biomarkers in ICIs.

The most established biomarkers for ICI responsiveness currently in clinical use include PDL1 IHC, tumour mutational burden, microsatellite instability or its equivalent, mismatch repair genes (dMMR) IHC, and tumour infiltrating lymphocytes [

92]. Emerging biomarkers include the microbiome [

93].

PD-1/PDL1 expression is an important biomarker in NSCLC. Expression of the checkpoint proteins, PD-1/PDL-1 can be assessed by immunohistochemistry and are currently used routinely as a ICI biomarker [

73]. Several FDA approved assays have been demonstrated to have strong clinical utility as predictive biomarkers in clinical trials [

73,

94]. While the implementation in a clinical immunohistochemistry laboratory is now routine and widespread, a number of practical challenges exist. Different antibodies have received approval for specific monoclonal therapies [

95]. The different scoring methods are used for specific antibodies, each having its own cutoff [

96]. Different scoring methods include the following:

(a) The combined positive score (CPS): the percentage of PD-L1 stained cells (tumour cells, lymphocytes and macrophages versus by the total number of viable tumour cells (for SP142 antibody);

(b) The total tumour proportionality (TC): The percentage of PDL-1 stained tumour cells versus total number of viable tumour cells (for SP142 antibody)

(c) The tumour infiltrating immune cell score (IC): percentage of the area of tumour infiltrated by PD-L1 stained cells versus the total tumour area (for the SP142 antibody)

(d) Tumour proportional score: The percentage of PDL-1 stained tumour cells versus total number of viable tumour cells (using 22C3 or SP263 antibody).

Each immunotherapy has its own companion diagnostic assay. Nivolumab uses Dako 28-8. The scoring system is TC, the cutoff is > 1-5% for NSCLC and > 5% for RCC. Atezolizumab uses Ventana SP142 as its companion diagnostic. It uses the TC or IC system with a cut off of > 5% for urothelial CA (IC) and 10% for NSCLC (IC) or >= 50% (TC).

As these antibodies run on different platforms (Dako vs Ventana), the high cost of the platform renders dual possession in a regular clinical IHC lab untenable. Interobserver variability introduces some degree of measurement uncertainty. Variability also occurs from different specimen types, e.g. surgical vs core vs FNAs; formalin fixation vs frozen samples etc. Intratumoural heterogeneity may add a layer of variability. Despite these challenges, a number of initiatives at standardization are ongoing with promising results [

97]. Early findings show that a well-validated antibody assay on a different platform may perform comparably to the FDA-approved version.

Tumour mutational burden (TMB) is an important biomarker for ICIs [

98]. TMB refers to the total number of mutations per megabase of interrogated genomic sequence present in a tumour specimen. Its diagnostic activity relies on the fact that the number of mutations in a tumour is directly correlated with the likelihood of the production of immunogenic neoantigens by that tumour [

99]. A high fraction of immunogenic neoantigens increases the chances of T cell recognition and cancer cell destruction. The technical definition, however, is dependent on the methodology used for TMB detection. Whole exome sequencing is the gold standard. At its adoption, TMB was defined as non-synonymous mutations in coding regions, excluding germline polymorphisms, which were subtracted using matched normal samples. Studies show that TMB-High tumours correlate with better outcome after ICI therapy. Challenges also exist in the clinical utility of TMB as a ICI biomarker [

100].

Different NGS TMB assays have been developed using either the gold standard WES or a targeted NGS panel (tNGS) [

101]. Examples include MSK-IMPACT from Sloan-Memorial Kettering Molecular Lab, FoundationOne CDx, Trusight (illumine), Oncomine (Thermofisher), Qiagen comprehensive gene panel. The number of genes in the panel ranges from 22,000 for the WES to 160 in the Qiagen comprehensive cancer panel. The corresponding size in megabases is from 30 to 0.7. While WES and MSK-IMPACT exclude synonymous mutations and perform germline analysis and subtraction, the others do not. Other variations include the number of mutations detected per 10 m/MB in the genome which ranges from 306 by WES to 7 by Qiagen. Studies demonstrate that the coefficient of variation increases with decreasing size of the targeted panel. This implies that the accuracy is correlated with the size of the panel. Though TMB provides significant prediction benefit in ICI, limitations include the fact that a high TMB score does not always equate to immunogenic neoantigen production. Response rates to ICI in TMB-High tumours is only 45%. Also, TMB only assesses an intrinsic cancer cell property of genomic mutations, while important factors mediated by the important role of host immune microenvironment in T cell mediated cancer cytotoxicity including T-cell infiltration, the balance between activating and suppressive cytokines, the type of checkpoint exploited by the cancer, among others are not assessed. Other host factors that lie outside the domain of TMB but significantly impact immune responsiveness include the MHC class and the T cell receptor landscape. The type of tumour also impacts TMB interpretation. Furthermore, TMB cutoffs varies for specific tumour types. For instance, in various clinical trials using TMB as a biomarker, the cut-off varied for different tumour types and testing drug. In the Checkmate 026 trial for Nivolumab in NSCLC, the TMB cutoff using WES was > 243 mut/ exome. In the Checkmate 038 trial for Nivolumab in Melanoma, the TMB cutoff in WES was >100 mut/exome. This variability is further augmented when using different therapies, in different tumour types and different TMB detection methods [

98]. TMB is thus an imperfect predictor for ICI responsiveness. The response rate in TMB classes shows ICI responsiveness in 5% of TMB-low, 25% of TMB-Intermediate, 45% of TMB-High and 65% of TMB-very high.

The influence of Genomic factors can be seen in TMB performance. Mutational signatures of mutagenic processes e.g UV signatures in chronic sun damaged melanoma, smoking in lung cancer, aflatoxin B1, viruses, defective MMR frequently produce TMB-High tumours [

100]. Cancer causing viruses also influence TMB, with HPV positive cancers harbouring higher TMB in comparison with their negative counterpart. Other mutational signatures, e.g. BRCA1/2, APOBEC deficiency, neoantigen load, TP53 mutations, Polymerase ε (POLE) also influence TMB scores.

Mismatch repair genes recognize and correct DNA replication errors. Clinically relevant genes in these group include MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6 [

102]. DNA replication errors consist of insertion and deletions, resulting from base pair mismatch. Defects in this mechanism cause hypermutation, which accumulates within short tandem repeats in the genome. Screening for defective MMR genes (dMMR) is performed by immunohistochemistry or molecular testing by PCR or NGS. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Translational Research and Precision Medicine Working Group published recommendations for the MSI testing for immunotherapy in cancer [

103]. The working group performed a meta-analysis of 3 ICI biomarkers MSI, TMB and PDL-1. They recommended the most appropriate methodology for dMMR testing. The primary recommended methodologies were immunohistochemical testing for MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6; PCR-based testing for MSI using microsatellite markers. Microsatellite markers should include at least BAT-25 and BAT-26. NGS may be the preferred method for analysis in rare and low-incidence tumours, particularly those not belonging to the lynch syndrome spectrum. The committee also compared the performance of MSI, TMB and PDL1 as predictive biomarkers. There was a low concordance of TMB, MSI and PDl-1 in all cancer types, when all three were studied together (

Figure 4). Supporting previous findings that these biomarkers measured independent cellular mechanisms in cancer. Concordance showed a moderate increase in specific cancer types when two of these biomarkers were considered. There was also a correlation with response rate to ICIs.

The College of American Pathologists also published guideline recommendations for IHC testing in the setting of ICI, with endorsement by the American Society of Clinical Oncologist [

104]. The recommendations were generally similar to that of ESMO.

Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) impacts ICI response in a number of ways [

105]. Peptide neoantigens are loaded on MHC molecules via the ubiquitin proteosome complex and transported to the cell surface, where they function in antigen recognition with T cell receptors. Maximum heterozygosity of MHCs potentiates the antigen presentation by the host of a higher range of neoantigens. Some specific MHC subtypes are innately better at preferentially presenting antigens enriched in tumours. HLA loss of expression and abnormalities of β-microglobulin may result in ICI resistance. MHC also functions in tumour mediated selection of poorly bound neoantigens in immune evasion. Mutations in MHC may also lead to immune evasion. Thus, MHC genotyping is a potential biomarker for immunotherapy.

The TCR repertoire is an important component of ICI responsiveness [

106]. High TCR clonality, which implies T-cell diversity has been correlated with better survival. The absence of T cell response either due to impaired or lack of T cell reactivity, or from active removal of anti-tumour reactive T cells affects ICI response.

Specific genomic mutations that occur during the oncogenic process also plays a role in ICI performance [

100]. Genomic alterations, PDL-1 amplification, Mutations in serpin genes, CDK12, SMARCA4, PBRM1 are associated with improved outcomes. Alterations in other genes including JAK1/2, STK11 are associated with blunted response. Adverse effects such as hyperprogression after ICIs have been associated with genetic alterations such as MDM2 amplification, EGFR aberrations.