1. Introduction

Survival rates can be improved and liver transplant requirements minimized in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients through early antiviral therapy. The extent and degree of hepatic fibrosis are of utmost importance, since the prognosis and treatment of the patient will depend on the final diagnosis. Thus, accurate and on-time grading of hepatic fibrosis is essential in CHB [

1,

2,

3]. Early diagnosis of impaired hepatic function can be made via certain laboratory tests, and delaying fibrosis is possible [

4]. However, routine biochemical and hematological tests fail to detect fibrosis in almost half of the patients [

3]. Gadoxetic acid (GA) [Eovist or Primovist, Bayer HealthCare, Berlin, Germany] is a hepatocyte-specific extracellular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent. It has been widely used to evaluate focal hepatic lesions, as well as for liver fibrosis [

2,

5,

6]. Contrasted enhancement index (CEI) calculated from GA-enhanced MRI has been accepted as a more efficient biomarker in the grading of hepatic fibrosis compared to certain hematological parameters and apparent diffusion coefficient value [

1].

The most accurate method of detecting the severity of inflammation and fibrosis in CHB is liver biopsy [

1,

7]. However, can a randomly taken sample from the liver truly reflect the overall damage to the organ? Sherlock's answer to this question is:

"It is surprising how often such a small biopsy accurately reflects the changes throughout the liver." — and indeed, this is a very valid observation. In non-focal diseases such as chronic viral hepatitis, where liver changes may be unevenly distributed, a biopsy sample may be insufficient [

8,

9]. As well as, GA-enhanced MRI studies have shown that the contrast agent is not evenly distributed across all regions of the liver [

1,

2]. Therefore, a randomly taken tissue sample of 10–15 mg, representing only a small portion of an organ weighing 1500 grams, will inevitably lead to an incorrect—or at best, incomplete—histopathological diagnosis. [

7,

10,

11]. The aim of this study is to discuss and validate the utility of signal intensity (SI) measurement on GA-enhanced MRI to determine the biopsy site for effective histopathological grading in patients with CHB.

2. Materials and Methods

This single-center retrospective study covered patients with CHB who underwent biopsies from the highest and lowest intensity areas identified on hepatobiliary phase (HBP) images obtained from GA-enhanced MRI. Over a 10-year period, a total of 4,368 consecutive liver biopsies were performed in our interventional radiology unit. Of these, 3,083 were parenchymal biopsies. Among these patients, those who met the following criteria were investigated: (a) had CHB, indicated by HBsAg positivity persisting for over six months, (b) had liver MRI enhanced with GA; (c) had no previous history of hepatocellular carcinoma and other malignancies; (d) had no previous history of other parenchymal diseases such as viral hepatitis C, primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, or Wilson disease; (e) had SI measurements of each segment on HBP images. Following this detailed review, 86 patients were included for further evaluation.The final exclusion criteria for the 86 patients were as follows : incomplete MRI examination (n=17), inability to access MRI scans (n=11), refusal to undergo double-segment biopsy (n=17), and failure to perform pathological examination in at least one of the two segments (n=1). Ultimately, 80 biopsy procedures performed on 40 patients were included in the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (ID number: 2019.165.09.25) and adhered to the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

MRI

MRI images were obtained using a GE Optima 360 1.5 T scanner (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Abdominal images were obtained in the axial plane using an 8-channel torso coil. The contrast agent was used as 0.025 mmol per kilogram of body weight GA. This was followed by a 15-20 ml flush with physiological saline. The contrast-enhanced protocol consisted of a three-dimensional volumetric interpolated breath-hold T1-weighted LAVA sequence in the axial plane (repetition time, 4.01 msec ; echo time, 1.9 msec ; flip angle, 120 ; section thickness, 4.6 mm; intersection gap zero; and matrix 320x192; the field of view 400 mm). For each patient, routine triphasic MRI and HBP images in the 20th minute were obtained.

Image Analysis And Biopsy Procedure

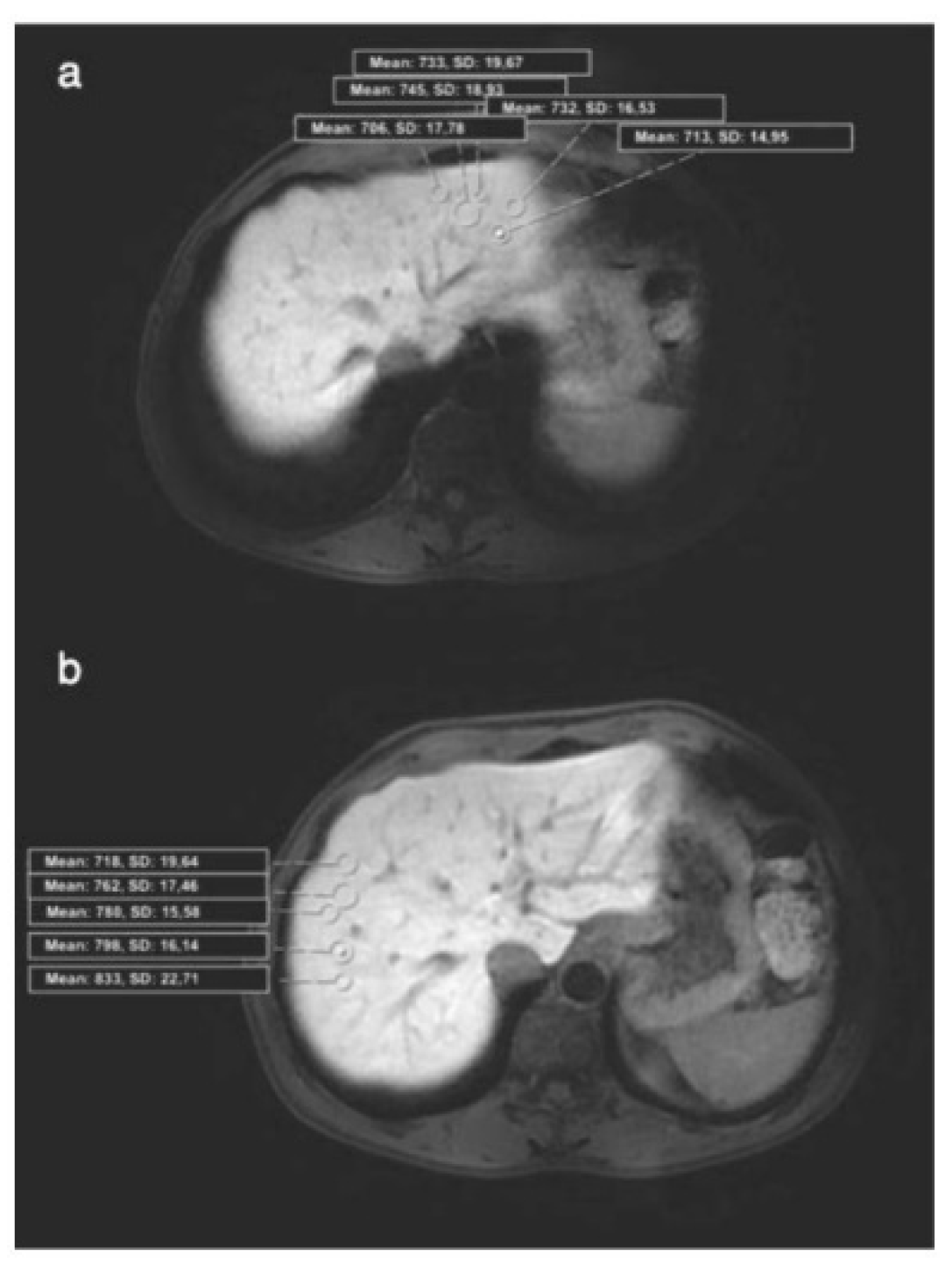

Imaging analysis was performed by a radiologist (15 years of experience in abdominal region). Images of the patients with a history of CHB were analyzed in detail due to the risk of additional pathologies; no solid hepatic lesion was detected in any of the patients. A region of interest (ROI) was drawn manually as round shapes on the liver in HBP images (mean: 20 mm

2), and SI measurements were made from almost every point (a minimum of 4 to 5 different foci) of each segment (

Figure 1. a, b ; 2. a, b). Subsequently, mean SI values were calculated for each segment. ROIs were placed carefully to avoid positioning on a possible cyst, biliary ducts, portal, or hepatic veins. According to the mean values calculated, 2 segments with maximum (group 1) and minimum (group 2) SI values were determined in each patient's liver. The median SI value was calculated for all segments and 2 more groups were formed (SI values>617 and <617). Biopsy was planned for 41 patients who have accepted the procedure, and coagulation parameters were checked the previous day. The mean duration between hepatic MRI and biopsy was 34 (4-47) days. INR, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), and the platelets of patients were normal (<1.5, <15 seconds, <45 seconds, >50.000, respectively). The ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsies were performed under local anesthesia, by an experienced radiologist (with 12 years of experience in IR) from 2 different segments (with the maximum and minimum SI values) of the liver. Full-automatic Bard needles (CR Bard, Inc., Georgia, USA) with a 2 cm shot distance were used for the procedure. Among those, 18 G was used in 30 patients, and 16 G was used in 11 patients. The total number of pieces was not over 3, and a minimum of 1 piece was obtained from each segment. No minor or major complications developed. Histopathological evaluation was performed by a pathologist who was experienced in hepatic histopathology for more than 10 years. She was blinded for MR image analysis and patient data. In one patient, a histopathological examination could not be performed on the biopsy material. Pathological examination was performed by using a modified histologic activity index (mHAI) and Ishak-Knodell Scoring System and inflammation and fibrosis scoring were assessed [

12]. According to that, the clinically significant activity limit was accepted as ≥5 for grades 1-18, and ≥2 for fibrosis staging of 1-6.

Figure 1.

(a) Axial HBP MR image shows placement of ROIs in the 2nd segment (Histopathology: mHAI:, 5/18; fibrosis:, 2/6). HBP: Hepatobiliary phase, ROI: Region of interest, mHAI: modified histologic activity index. (b) Axial HBP MR image shows placement of ROIs in the 7nd segment (Histopathology: HAI: 3/18; fibrosis: 1/6). HBP: Hepatobiliary phase, ROI: Region of interest, mHAI: modified histologic activity index.

Figure 1.

(a) Axial HBP MR image shows placement of ROIs in the 2nd segment (Histopathology: mHAI:, 5/18; fibrosis:, 2/6). HBP: Hepatobiliary phase, ROI: Region of interest, mHAI: modified histologic activity index. (b) Axial HBP MR image shows placement of ROIs in the 7nd segment (Histopathology: HAI: 3/18; fibrosis: 1/6). HBP: Hepatobiliary phase, ROI: Region of interest, mHAI: modified histologic activity index.

Figure 2.

(a) Axial HBP MR image shows placement of ROIs in the 2nd segment (Histopathology: HAI, 2/18; fibrosis, 0/6). HBP: Hepatobiliary phase, ROI: Region of interest, mHAI: modified histologic activity index; (b) Axial HBP MR image shows placement of ROIs in the 8nd segment (Histopathology: HAI, 2/18; fibrosis, 0/6). HBP: Hepatobiliary phase, ROI: Region of interest, mHAI: modified histologic activity index.

Figure 2.

(a) Axial HBP MR image shows placement of ROIs in the 2nd segment (Histopathology: HAI, 2/18; fibrosis, 0/6). HBP: Hepatobiliary phase, ROI: Region of interest, mHAI: modified histologic activity index; (b) Axial HBP MR image shows placement of ROIs in the 8nd segment (Histopathology: HAI, 2/18; fibrosis, 0/6). HBP: Hepatobiliary phase, ROI: Region of interest, mHAI: modified histologic activity index.

Statistical Analysis

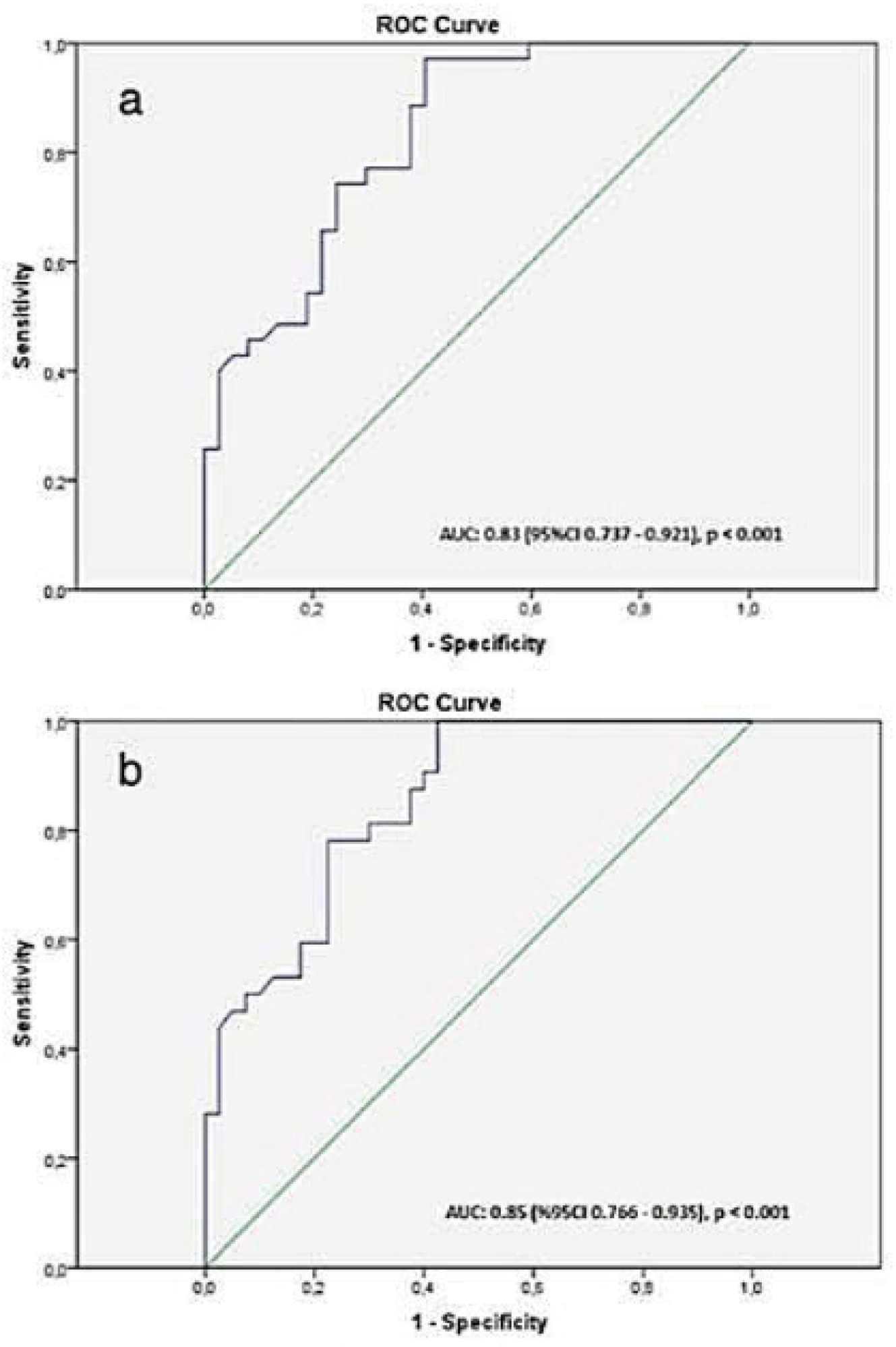

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS for Windows 22.0 (Statistical Product and Service Solutions, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) package program. In the descriptive analysis, the measurement variables are given as a mean ± standard error. The differences between groups were assessed by using Chi-square and independent-sample t-tests. The diagnostic value of the SI measurement for the evaluation of the mhai (≥5) and fibrosis score (≥2) was ssessed by using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The optimal cutoff points were determined by the Youden index as follows: Sensitivity – (1 – Specificity). The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated from the ROC curves. P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

In chronic viral hepatitis, the primary purpose of liver biopsy is to grade and stage liver damage for prognosis and treatment planning. A standard liver biopsy may represent only 1/50,000 to 1/100,000 of the entire liver [

8]. Limited tissue sampling, subcapsular sampling, or heterogeneity in the degree of fibrosis between the right and left lobes may lead to misinterpretation in 10–30% of cases [

11]. Nearly all studies agree that the diagnostic accuracy of liver biopsy increases with the amount of tissue obtained [

8,

9]. In our clinical practice, discrepancies between clinical and/or serological findings and histopathological results have been observed in certain cases, leading to diagnostic uncertainty. Based on comprehensive literature reviews on GA-enhanced MRI and our institutional experience, we developed an alternative approach, as we believed that a randomly sampled segment may not reflect overall liver damage. Instead, we performed biopsies from two different segments of the liver that exhibited the highest and lowest signal intensities on GA-enhanced MRI. In each procedure, the number of biopsy samples obtained was limited to a maximum of three, in accordance with our institutional standard protocol. This approach aimed to maximize diagnostic yield while minimizing procedural risk. In our study, we observed that biopsy specimens obtained from segments with low signal intensity (<606) on hepatobiliary phase (HBP) images in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) were more likely to show clinically significant inflammation and fibrosis. We believe that pre-biopsy signal intensity measurement on GA-enhanced MRI is a valuable and applicable method for assessing necroinflammation and fibrosis in patients with CHB.

Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis secondary to CHB are common causes of mortality. Morbidity and mortality are directly related to the progression of hepatic fibrosis in these patients [

10,

13]. It is possible to decelerate the progression and reverse back the process of fibrotic remodeling with the treatment of the underlying disease [

3,

4]. The most important parameter for this is the accurate staging of hepatic pathology. Recently, the non-invasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis has become an important area of study. Some serological indicators and biomarkers have widely been used for this purpose [

2]. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) and fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) are widely accepted reference markers in predicting fibrosis in patients with CHB [

2,

14]. The combination of AST, anti-HBC and GGT has a good prognostic performance in CHB [

15]. Fibrosis may refect to hepatic function tests, however, these tests cannot detect the regional defects of the liver [

7]. US and MR elastography may indicate the stiffness and fibrosis of the liver indirectly only. Both the limited field of vision and operator-dependency limit the optimal hepatic evaluation via the US. Elastography, on the other hand, may lead to misinterpretation or false measurements in the presence of concomitant diseases [

10,

14]. It is impossible to evaluate the whole liver via MR elastography; for example, no measurement can be obtained from the left lobe due to cardiac artifacts [

14].

GA has been accepted as the primary non-invasive biomarker of hepatobiliary disorders since it potentially indicates hepatocyte function [

2,

3,

6]. Transport of GA to hepatocytes is provided by two different systems located on the sinusoidal and canalicular membranes of the cell [

2]. It enters the cell bound to organic anion transporting polypeptide 1 and 3 (OATP1B1 and OATP1B3) and excreted via multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2= apical transporter) into the bile [

4,

7,

16]. In MRI, peak hepatic SI with GA, which is HBP, is obtained on the 20th minute after the injection [

1]. Imaging patterns of HBP are classified into two categories hypointense and hyper/iso-intense. These patterns may be explained by the expressions of OATP and MRP. In chronic hepatitis, the number and function of hepatocytes are reduced, and fibrotic tissue accumulation which prevents access to hepatocytes is observed. Consequently, OATPB1/B3 activity and contrast agent enhancement are reduced [

2]. Starting with this theory, GA-enhanced HBP MRI has been used in many studies to evaluate hepatic function and fibrosis. In the majority of the studies, this evaluation was performed using either direct measurement of hepatic contrast or some quantitative measurements such as relative liver enhancement (RLE), CEI, or T1 relaxation time. Significant outcomes have been reported in almost all of these studies correlating the extent of fibrosis and MRI parameters [

3,

4,

10,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The severe fibrosis in CHB using the quantitative coefficient of variation parameter in GA-enhanced MRI [

2]. There are many studies demonstrating the correlation between the Child-Pugh stage and the degree of parenchymal enhancement [

6,

21]. However, the most frequently used method for the evaluation of hepatic function in GA-enhanced MRI is the measurement of parenchymal SI, which we have used in our study [

1,

13,

22,

23,

24]. Additionally, In gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI, simple SI-based measurements have been proven to be as effective as more complex parameters in evaluating liver function [

24].

In chronic hepatitis, there is a strong relationship between the stage and the severity of the disease. Therefore, classification is clinically beneficial for these patients and provides a guide for the management of the disease. The most common pathological grading method is mHAI, also known as Knodell's score. A score between 1 and 3 was accepted as minimal chronic hepatitis, 4-8 was accepted as mild chronic hepatitis, 9-12 was accepted as moderate chronic active hepatitis and 13-18 was accepted as severe chronic hepatitis. For the staging, 5 stages were defined according to the degree of fibrosis and development of cirrhosis (stage 0= no fibrosis, stage 1= mild, stage 2= moderate, stage 3= severe, stage 4= active cirrhosis) [

12]. Recent guidelines recommend antiviral therapy in moderate and severe inflammations as well [

15,

25]. In this study, thresholds defined by the Health Practice Guideline prepared according to the EASL criteria were used for the treatment, and ≥5 and ≥2 were accepted as significant for mHAI and fibrosis, respectively.

A strong correlation has been demonstrated between the degree of fibrosis and RLE [

1,

4,

7,

10,

26]. Moreover, there are studies suggesting overlapping RLE values between different stages of fibrosis. Because hepatic fibrosis progression is different in each segment of the liver. Thus, pathological sampling may not reflect the actual fibrosis and the progression of fibrosis cannot be clearly segmented in the liver. In addition, it has been demonstrated that the carriers in the liver may differ in the absorption or excretion of gadolinium chelate according to their functional capacities [

2]. Therefore, uptake and accumulation of the contrast agent would not be the same in different segments of the liver, and a non-homogeneous contrast would be observed in CHB [

1,

2]. In our study also, segmentary SI measurements were different and the maximum and minimum SI measurements were mostly obtained from the right lobe.

Percutaneous hepatic biopsy, frequently used in IR practice, is the gold standard in chronic hepatitis [

1,

7,

13]. Generally, the 6-9th intercostal gap in the mid-clavicular line is preferred for biopsy due to its low risk of complications [

27]. However, heterogeneous parenchymal involvement is present in patients with chronic parenchymal disease. The hepatic enhancement measurements have been calculated from the mean ROI measurements obtained from different segments of the liver to reduce the effect of these heterogeneous parenchymal changes. Nevertheless, histopathological sampling is generally performed from a random segment of the liver, which may lead to significant differences in tissue sample results and cause the disease to be diagnosed at a lower stage than it actually is [

7,

8]. Additionally, there are also risks of sampling errors related to the sample size [

2,

13]. In CHB, an effective pathological examination requires 11–15 complete portal tracts, which corresponds to a biopsy specimen of at least 20–25 mm in length. Therefore, it is recommended to obtain more than one tissue core during biopsy. On the other hand, it has been shown that performing multiple biopsy passes does not increase the risk of major complications (9). In our daily routine practice, we have been consistently obtaining at least two tissue samples during liver biopsies for quite some time. Additionally, in this study, in which two different segments were biopsied in each patient, we did not encounter any complications. Consequently, there is a need for applying rigid criteria for liver biopsies as a reference procedure [

7].

This paper supports the suggestion that GA-enhanced MRI could be included in routine practice as a screening test in the staging of fibrosis in CHB. This approach is easy to use in clinical practice and does not necessitate additional MRI sequences, mathematical modeling, or complex analysis of MRI signal properties. The authors observed clinically significant inflammation and fibrosis values when they obtained biopsies from the segments with the lowest intensity in GA HBP compared to MRI (SI cut-off values for fibrosis grading: 599, for mHAI: 606). Inflammation and fibrosis scores were also significantly higher in liver segments below the median SI value (<617), which supported our cutoff values. In addition, although not statistically significant, they observed only 1 patient with a fibrosis score of 0/6 in both groups. Based on this study's results, the authors suggest that livers with an SI value below 606 should be biopsied from the lowest SI segment, and livers with a high SI value should be followed up. A long-term prospective study in a larger study population is required to better confirm these findings.

This study includes patients with CHB only. Because the etiology is an effective parameter on parenchymal changes and SI measurements. However, this study had some limitations: It was a retrospective, single-center, and relatively small study. The duration between biopsy and MRI was not standard for each patient. The authors compared the cellular uptake of GA with biopsy only and did not use hepatic function tests such as indocyanine green test and non-invasive indexes (APRI, FIB-4) or morphological tests such as elastography. The sample variation may be present since the biopsy of certain segments is difficult. Another relative limitation of the study is the impact of the magnetic field strengths of different scanner brands on the parameters studied. Background steatosis/ iron depositions are known to affect the absolute SI measurements on HBP. However, a recent study concluded that relative enhancement was more consistent over successive examination scanners and the field strengths and GA-enhanced MRI had various advantages over global liver function tests [

28].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.G. and R.M.; Methodology, K.A.G. and R.M.; Software, K.A.G.; Validation, K.A.G., M.F.I. and M.O.; Formal Analysis, K.A.G. and M.O.; Investigation, K.A.G., M.F.I.; Resources, K.A.G. and M.O.; Data Curation, K.A.G., M.F.I. and R.M.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, K.A.G.; Writing – Review & Editing, K.A.G., M.F.I., R.M. and M.O.; Visualization, K.A.G., M.F.I. and M.O.; Supervision, K.A.G; Project Administration, K.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.