1. Introduction

In recent years, behavioral plasticity has emerged as a crucial adaptive strategy through which animals respond to environmental change, drawing significant attention from the fields of ecology, behavioral science, and evolutionary biology [

1,

2,

3]. This term refers to an animal’s ability to adjust its behavior in response to environmental fluctuations, individual needs, or social interactions [

4]. Research into behavioral plasticity—how animals modify their behavioral patterns in response to changing environments, resource variability, or social dynamics—not only advances our understanding of ecological adaptation mechanisms but also provides critical insights into predicting biodiversity trends under the influence of human activity and climate change [

5,

6].

Numerous studies have demonstrated behavioral plasticity across diverse animal groups. For example, research on the ant (

Myrmica graminicola) in Parisian forests and urban parks revealed that habitat fragmentation forces the winged morphs—normally adapted for long-distance dispersal—to adopt a short-distance dispersal strategy [

7]. Reintroduced Chinese giant salamanders (

Andrias davidianus) have been observed adjusting their movement distances to accommodate local variations in temperature and precipitation [

8]. Devarajan et al. (2025) analyzed 89,000 mammalian activity records and found that while nearly half of the species maintained traditional diurnal or nocturnal activity patterns, many exhibited pronounced diel plasticity under human disturbance [

4]. In temperate deciduous forests, red-backed voles (

Myodes regulus) displayed significant expansion or contraction of their home ranges in response to changes in elevation, lunar phase, and ground vegetation cover [

9]. Hernández Carrasco et al. (2025) further highlighted that seasonal climate fluctuations can drive animals to adjust spatial behaviors—such as home range size—to align with temporal shifts in resource availability and habitat conditions [

10]. Additionally, white-tailed deer (

Odocoileus virginianus) have been found to reduce daytime feeding while increasing nocturnal foraging to compensate for energy needs under thermal stress conditions [

11].

Rewilding, although a potent strategy for restoring populations of endangered species [

12,

13], remains a high-risk endeavor. Its success is often constrained or compromised by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors such as habitat degradation, climatic mismatch, behavioral inflexibility, disease and genetic risks, and human-wildlife conflict [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. For instance, the rewilding Arabian oryx in Oman faced population limitations due to drought and illegal hunting [

19]. Similarly, rewilding American bison (

Bison bison) experienced selective predation pressure from wolves [

20]. In Zambia’s project for recoverying African lions, significant community resistance emerged owing to concerns over livestock predation, lack of shared economic benefits, and distrust in project governance—social factors that critically hinder rewilding efforts [

21]. Thus, post-release monitoring and studies of adaptive responses are essential components of rewilding programs [

22,

23,

24]. However, research on behavioral plasticity in rewilding species remains scarce.

The Milu (Père David’s deer,

Elaphurus davidianus) is a rare deer endemic to China. Historically extinct in the wild, it has recovered gradually through captive breeding and reintroduction efforts [

25]. Originally, Milu inhabited the warm, moist, floodplain wetlands of the Yangtze and Yellow River basins [

26]. Since 1998, conservation efforts have focused on rewilding programs aimed at reestablishing self-sustaining populations within its historical range, including the Dongting and Poyang Lakes in the Yangtze Basin and the intertidal wetlands along the Yellow Sea coast [

25,

27,

28]. Several studies have monitored the behavior of rewilding Milu using GPS tracking. In the Yellow Sea coastal wetland, female Milu showed pronounced seasonal shifts in home range size influenced by human activity and food availability—expanding into farmland during winter and spring, and contracting to tidal meadows and reedbeds within protected zones in summer and autumn [

27]. Similarly, in the Dongting Lake region, Milu had significantly larger winter home ranges than in summer [

29]. Ambient temperature further influenced their daily activity pattern: Milu at Dongting Lake rested mostly before 09:00 and after 18:00, with a foraging peak at 14:00, and exhibited sharply increased vigilance following disturbances [

30].

Milu have been successfully rewilding in nine field release events within China’s Yangtze River basin and Huaihai tidal wetlands [

25]. These regions are not only warm, humid lowland swamp habitats, but also the historical range of Milu and the sites with the highest archaeological fossil occurrences of this species [

31,

32]. In contrast, Inner Mongolia’s Daqingshan lies on the mid-altitude Mongolian Plateau, characterized by a typical temperate continental climate, complex terrain, and more severe living conditions. These harsher environmental factors present significant challenges to Milu's survival. Therefore, investigating the behavioral adaptation mechanisms—specifically changes in home range, dispersal behavior, and activity rhythm—of Milu in extreme environments is crucial for understanding their survival strategies and assessing the adaptive capacity of rewilding populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

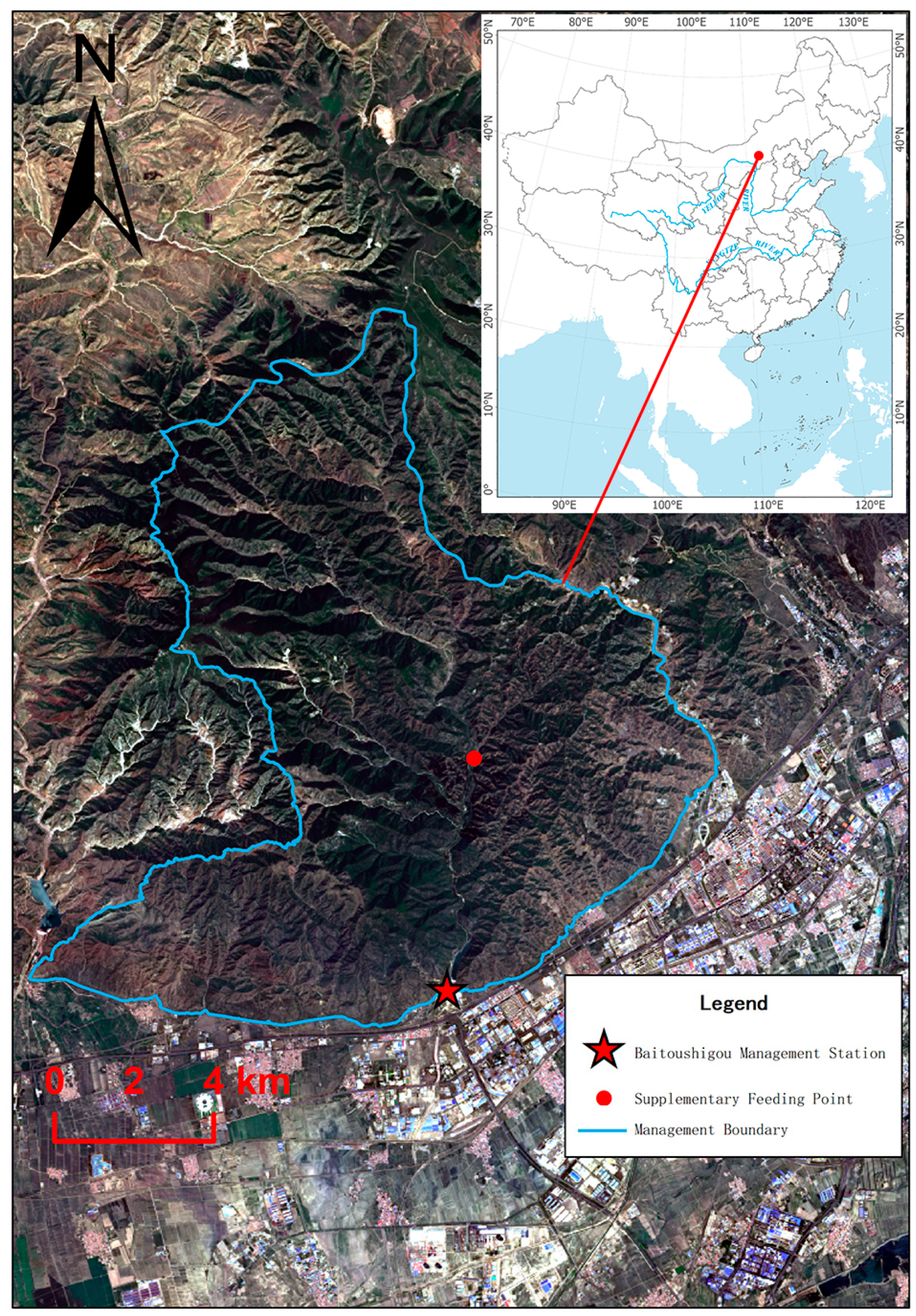

To establish more wild distribution areas for Milu and to enhance and consolidate Milu conservation achievements, we have carried out this rewilding program in the Daqingshan Nature Reserve, where is located in the Yinshan Mountains of central-western Inner Mongolia, encompassing parts of the Hohhot, Baotou, and Ulanqab administrative regions. The reserve stretches approximately 217 km from east to west, with an average north-south width of about 18 km, covering a total area of 388,900 ha, making it the largest forest-ecosystem nature reserve in northern China. Daqingshan, located on the southeastern margin of the Mongolian Plateau, borders the Yellow River Plain to the south, where Milu were once widely distributed historically. Located in the mid-temperate zone with a typical continental climate, the reserve has an average elevation of approximately 1,850 m, with its highest peak reaching 2,338 m. The annual average temperature ranges between 3 °C and 5 °C, and the annual precipitation is approximately 320–450 mm. Prior to the program, we conducted feasibility analyses on water, food, shelter, and human interference, among other factors.

The rewilding site for the Milu in this study is situated in the buffer zone at Baishitougou Management Station (E111.468683°, N40.822307°) of Daqingshan Nature Reserve (

Figure 1). The management station is primarily located in a natural secondary forest area, featuring multiple natural springs and perennial unfrozen streams. The main vegetation includes trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants such as: Chinese pine (

Pinus tabuliformis), White birch (

Betula platyphylla), Dahurian larch (

Larix gmelinii), Juniper (

Juniperus rigida), Mongolian linden (

Tilia mongolica), Siberian apricot (

Prunus sibirica), David poplar (

Populus davidiana), Mountain elm (

Ulmus glaucescens), Hazelnut (

Corylus heterophylla), Meadow sweet (

Spiraea salicifolia), Yellow rose (

Rosa xanthina), Feather grass (

Stipa capillata), Chinese leygrass (

Leymus chinensis), Lambsquarters (

Chenopodium album). The winter minimum temperature can drop to –30 °C. This site is in the reserve’s buffer zone and lies in a remote, uninhabited area with virtually no human disturbance, making it an ideal location for studying the deer’s autonomous adaptation behaviors in extreme environments. There was an iron fence barrier (E111.454377°, N40.803294°) in the southern preventing the Milu from spreading south into the urban area of Hohhot

2.2. Animals and Data Collection

27 milu were rewilding to Daqingshan from Nanhaizi, Beijing, and Dafeng, Jiangsu Province. Prior to rewilding, GPS satellite-tracking collars (HQAN40L, 800 g, 5-year battery life, solar-powered, Hunan Global Messenger Technology Co., Ltd., China) were fitted on 11 Milu (3 males and 8 females). To minimize the impact of collaring on natural behavior, the deer were anesthetized one month before release and the collars were installed to ensure adequate acclimation time before data collection [

33]. These GPS collars were equipped with tri-axial accelerometer sensors to continuously record activity data [

33,

34]. The sensors monitor real-time acceleration on the X, Y, and Z axes, with a default sensitivity threshold of 0.15 g (gravitational acceleration). Whenever acceleration on any axis exceeded this threshold, the device recorded an additional step, thereby quantifying the deer’s activity level. The GPS location and activity information were automatically saved every two hours. This data was then retrieved using Hunan Global Messenger's satellite tracking software (version 3.0401). In addition to using collars for home range and dispersal behavior, we conduct daily field observations and monitoring of the deer population.

Seasons were delineated based on local climatic conditions: spring (March to May), summer (June to August), autumn (September to November), and winter (December to February). Due to the limited effective collar time for some individuals and the absence of data for September 2021, average home-range areas and dispersal distances for both sexes were calculated using data from four seasons only: 2021 autumn (October–November 2021), 2021 winter (December 2021–February 2022), 2022 spring (March-May 2022), and 2022 summer (June–August 2022). The average diurnal activity rhythms for both sexes span from October 2021 to September 2022, covering a total of 12 months. We provided supplementary feed (hay and concentrated feed) once a year from November to April of the following year. Two individuals—F7 and M10—still have active collars. We analyzed their heatmaps over 14 seasons, from autumn 2021 to winter 2024 and examined differences in diel activity rhythms over 41 months (October 2021 to February 2025).

2.3. Data Analysis

All data were compiled and summarized using Excel 2021, and the results are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). The circadian rhythm graphs were produced with GraphPad Prism 5. Home range data (kernel density estimator (KDE), isopleth 95%), distances from the release site, and activity heatmaps were obtained from the v3.0401 Hunan Global Messenger Technology Satellite Tracking Data Management System, which employed a Gaussian kernel function for heatmap generation. Satellite imageryobtained from

https://earthexplorerusgs.gov/. Additionally, we used ArcGiSPro software to create the maps.

To analyze the sexual and seasonal differences in the circadian activity rhythms from Autumn 2021 to Summer 2022, the circular statistics, Watson one-sample and two-sample tests in R was used to determine whether the activity rhythms were significant. Compare the sexual differences of Milu in the 95% KDE and 50% KDE home range areas , as well as the farthest dispersal distances in each season, using t-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests in R. After the normality test, we used the paired-samples t-test in SPSS to examine the differences in home range and dispersal distance between seasons.

3. Results

Of the 27 rewilding Milu, over the past four years, two individuals died from an accident and succumbed to a gastrointestinal illness. All other individuals had survived, and the population had now increased to 64, indicating that the rewilding Milu population had successfully adapted to the local climatic conditions.

Table 1.

Basic information of rewilding Milu in Daqing Mountain.

Table 1.

Basic information of rewilding Milu in Daqing Mountain.

| No. |

Age (Years) |

sex |

monitoring period |

Valid fixes |

| F1 |

≥5 |

♀ |

2021.10.1-2022.9.30 |

9,831 |

| F2 |

≥5 |

♀ |

2021.10.1-2022.9.30 |

9,805 |

| M3 |

3.5 |

♂ |

2021.10.1-2022.9.30 |

6,880 |

| F4 |

3.5 |

♀ |

2021.10.1-2022.9.30 |

8,827 |

| F5 |

4.5 |

♀ |

2021.10.1-2022.9.30 |

10,257 |

| F6 |

2.5 |

♀ |

2021.10.1-2022.9.30 |

8,724 |

| F7 |

3.5 |

♀ |

2021.10.1-2025.2.28 |

17,228 |

| F8 |

4.5 |

♀ |

2021.10.1-2022.9.30 |

8,528 |

| F9 |

3.5 |

♀ |

2021.10.1-2022.9.30 |

9,775 |

| M10 |

4.5 |

♂ |

2021.10.1-2025.2.28 |

16,122 |

| M11 |

3.5 |

♂ |

2021.10.1-2022.9.30 |

4,796 |

| Total |

|

|

|

110,733 |

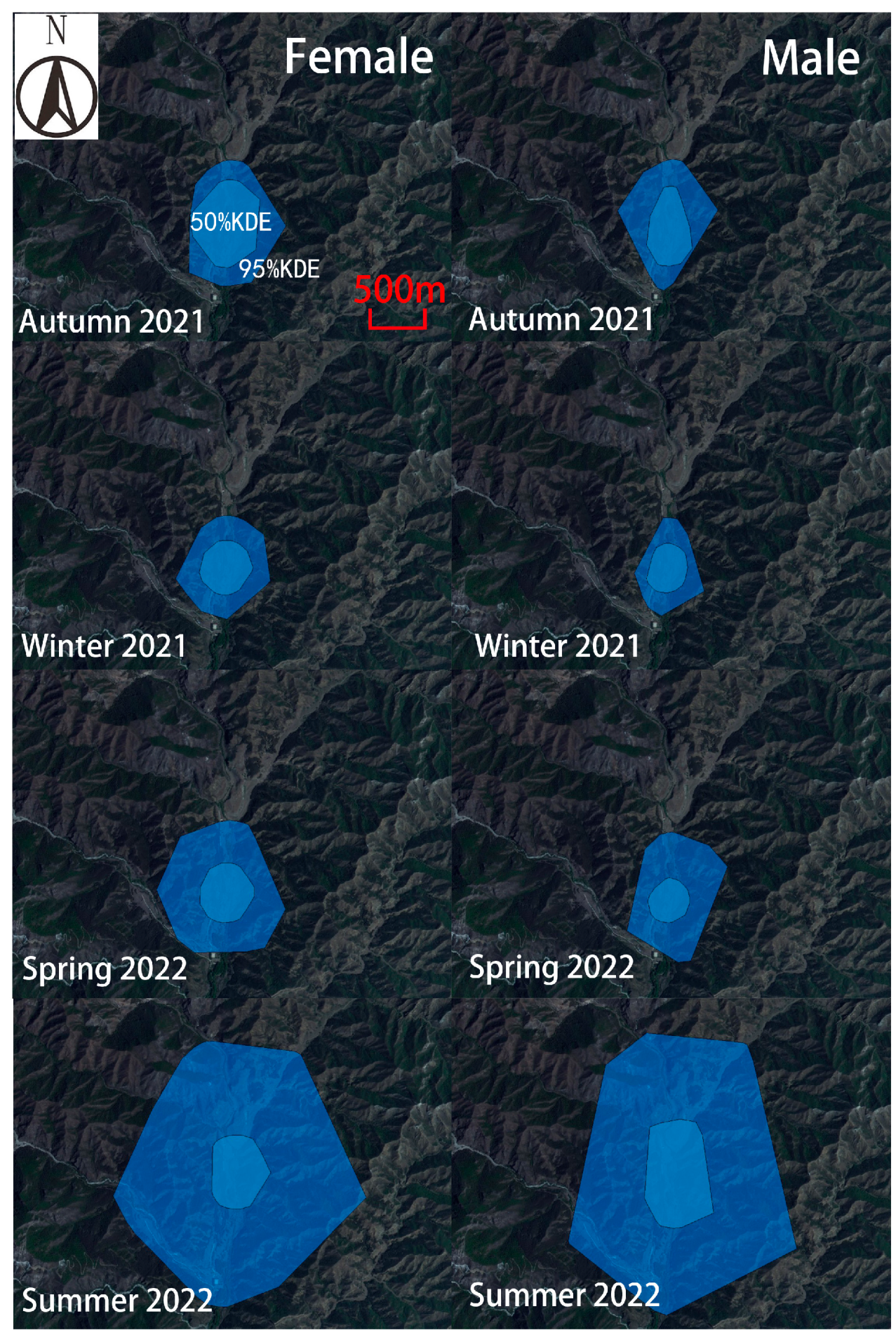

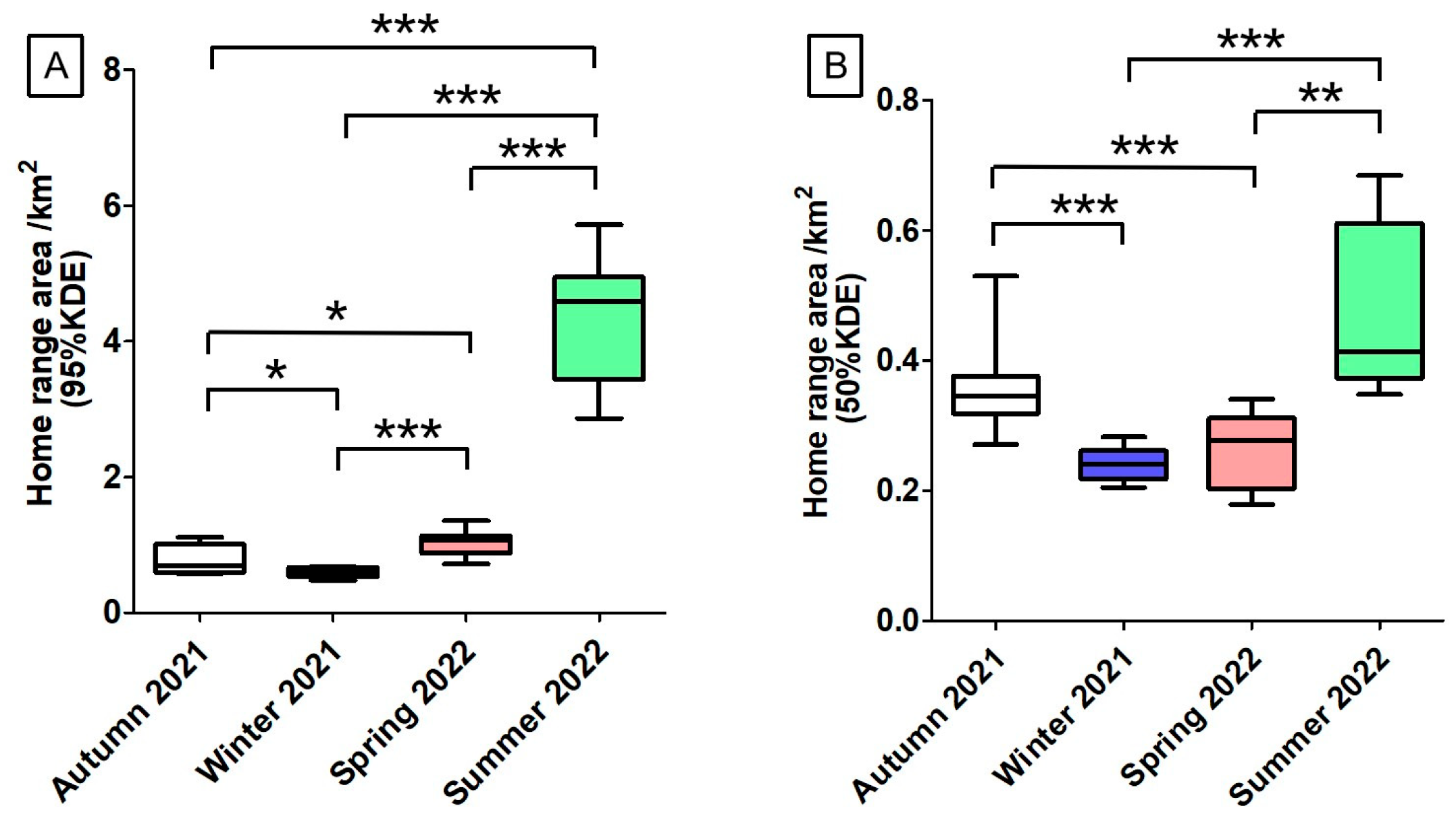

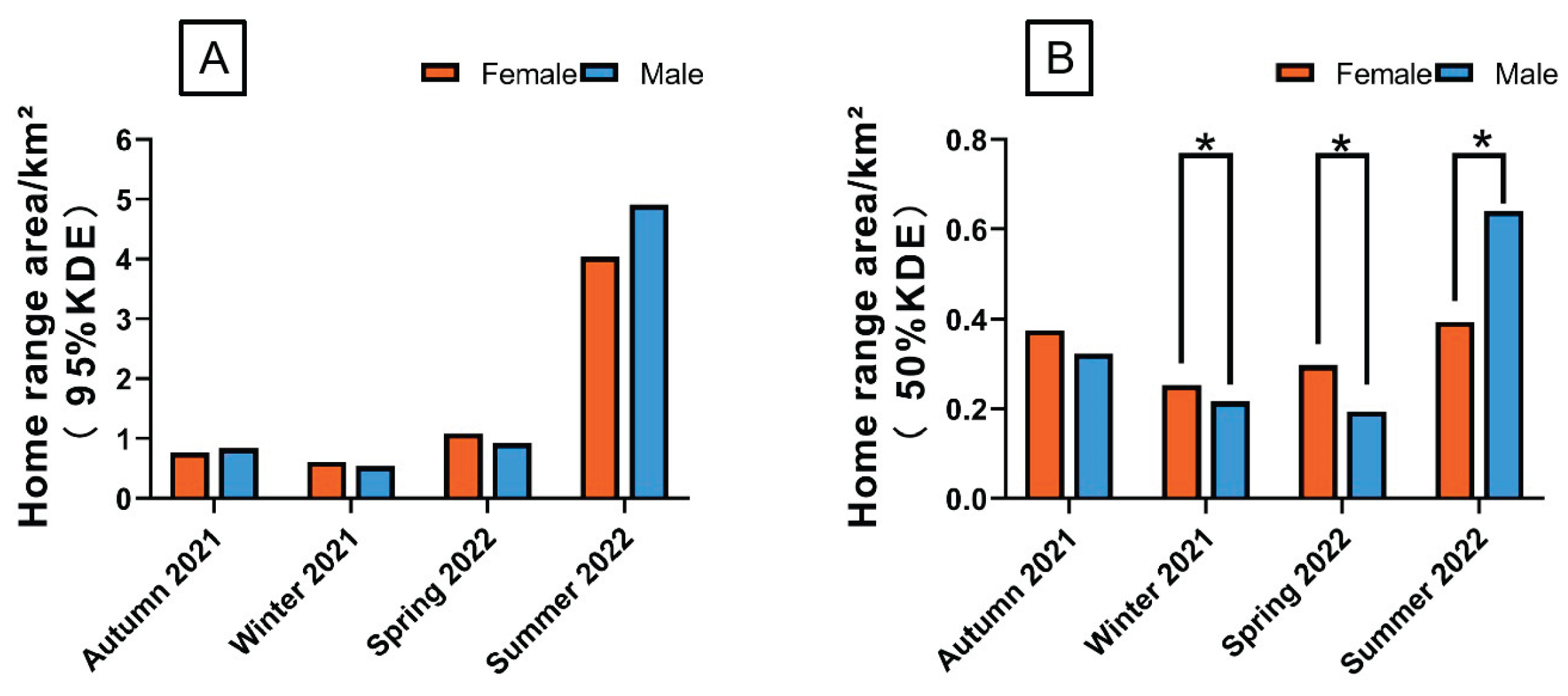

3.1. Home Range Area Analysis

During autumn 2021, winter 2021, spring 2022, and summer 2022, for these 10 Milu deer, there were significant differences in home range area (95% KDE) among the four seasons (

p > 0.05) (

Figure 3A). The male home-range areas (95% KDE) were 0.84 ± 0.06 km², 0.54 ± 0.002 km², 0.92 ± 0.02 km², and 4.91 ± 0.06 km². The corresponding values for females were 0.77 ± 0.04 km², 0.61 ± 0.005 km², 1.08 ± 0.04 km², and 4.04 ± 0.96km², respectively (

Figure 4A). Across all four seasons, the differences in home-range area between sexes were not statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U test,

p > 0.05).

During autumn 2021, winter 2021, spring 2022, and summer 2022, for these 10 Milu deer, home range areas (50% KDE) varied significantly across seasons (

p > 0.05), with the exception of no statistically significant differences between autumn 2021 and summer 2022 (

t=-2.052,

p = 0.068), as well as between winter 2021 and spring 2022 (

t=-1.750,

p =0.111) (

Figure 3B). The male home-range areas (50% KDE) were 0.32 ± 0.02 km², 0.22 ± 0.007 km², 0.19 ± 0.01 km², and 0.64 ± 0.04 km². The corresponding values for females were 0.38 ± 0.07 km², 0.25 ± 0.02 km², 0.3 ± 0.03 km², and 0.39 ± 0.04 km², respectively (

Figure 4B). Except for autumn (U = 17.0,

p = 0.358), significant differences between sexes were found in winter 2021 (

t = 3.42,

p = 0.019), spring 2022 (

t = 8.321,

p = 0.000), and summer 2022 (

t = -9.365,

p = 0.003).

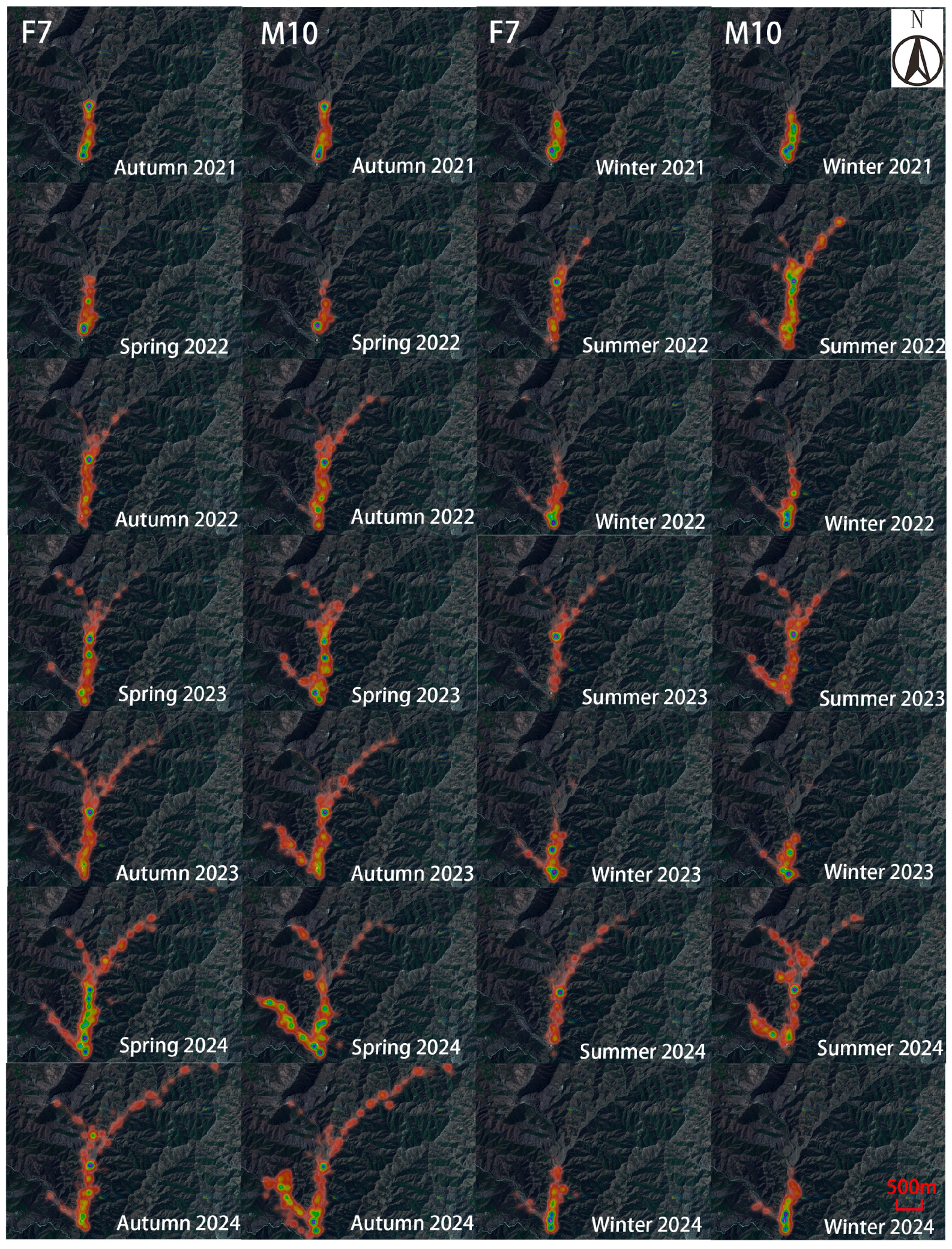

The Milu exhibited the largest activity range during the summer of 2022 (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The individuals F7 and M10 showed pronounced seasonal differences in their activity heatmaps (

Figure 5). Combined with daily monitoring observations, the results indicate that although the Milu’s activity range was smallest in winter, the range expanded year over year in spring, summer, and autumn following the rewilding, resulting in a continuous enlargement of their activity range over time (

Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Home range of rewilding Milu from Autumn 2021 to Summer 2022.

Figure 2.

Home range of rewilding Milu from Autumn 2021 to Summer 2022.

Figure 3.

Seasonal home range area of rewilding male and female Milu in Daqingshan (A is 95%KDE, B is 50%KDE. Statistically significant differences between seasons: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Seasonal home range area of rewilding male and female Milu in Daqingshan (A is 95%KDE, B is 50%KDE. Statistically significant differences between seasons: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Seasonal home range area of rewilding Milu in the Daqingshan (A is 95%KDE, B is 50%KDE. Statistically significant differences between sexes: *p<0.05)).

Figure 4.

Seasonal home range area of rewilding Milu in the Daqingshan (A is 95%KDE, B is 50%KDE. Statistically significant differences between sexes: *p<0.05)).

Figure 5.

Heatmaps of activity for F7 and M10 from Autumn 2021 to Winter 2024 in the Daqingshan.

Figure 5.

Heatmaps of activity for F7 and M10 from Autumn 2021 to Winter 2024 in the Daqingshan.

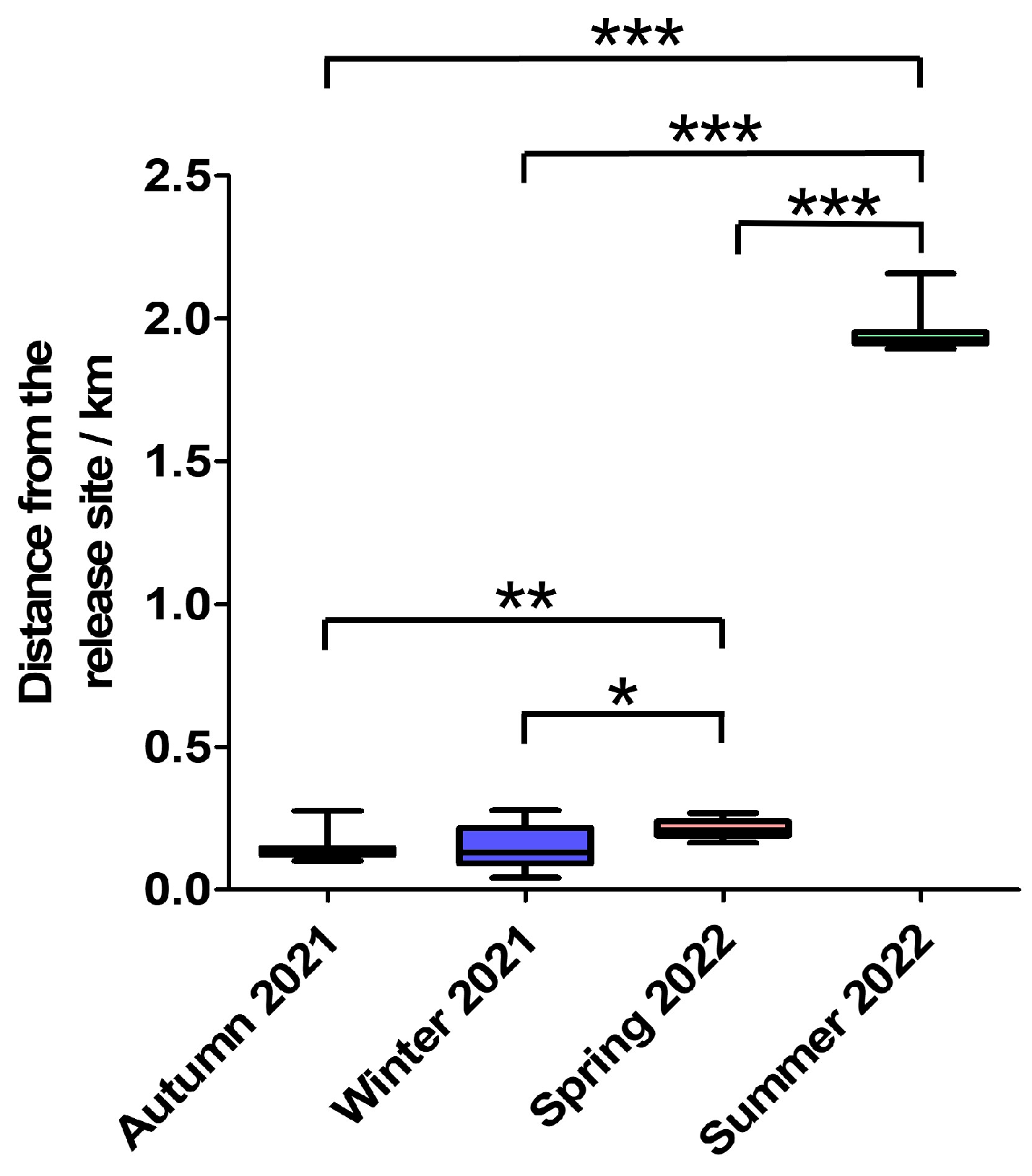

3.2. Dispersal Distance Analysis

During autumn 2021, winter 2021, spring 2022, and summer 2022, the mean dispersal distances for male milu were 115.45 ± 12.50 m, 106.08 ± 71.64 m, 225.43 ± 54.41 m, and 1992.99 ± 144.49 m, respectively. For females, the corresponding values were 164.50 ± 52.83 m, 166.41 ± 5536.22 m, 204.41 ± 19.69 m, and 1932.11 ± 18.78 m (

Figure 6). A statistically significant difference in dispersal distance between sexes was observed only in Autumn 2021 (U = 22.0,

p = 0.0485). For these 10 Milu deer, there were significant differences in dispersal distances among the four seasons, except between autumn 2021 and winter 2021 (

t=0.058,

p =0.955). Although the Milu’s dispersal distance was smallest in winter, the dispersal distance gradually increased during autumn from 2021 to 2024, while the dispersal distance in spring and summer also increased year by year starting from 2022 to 2024.

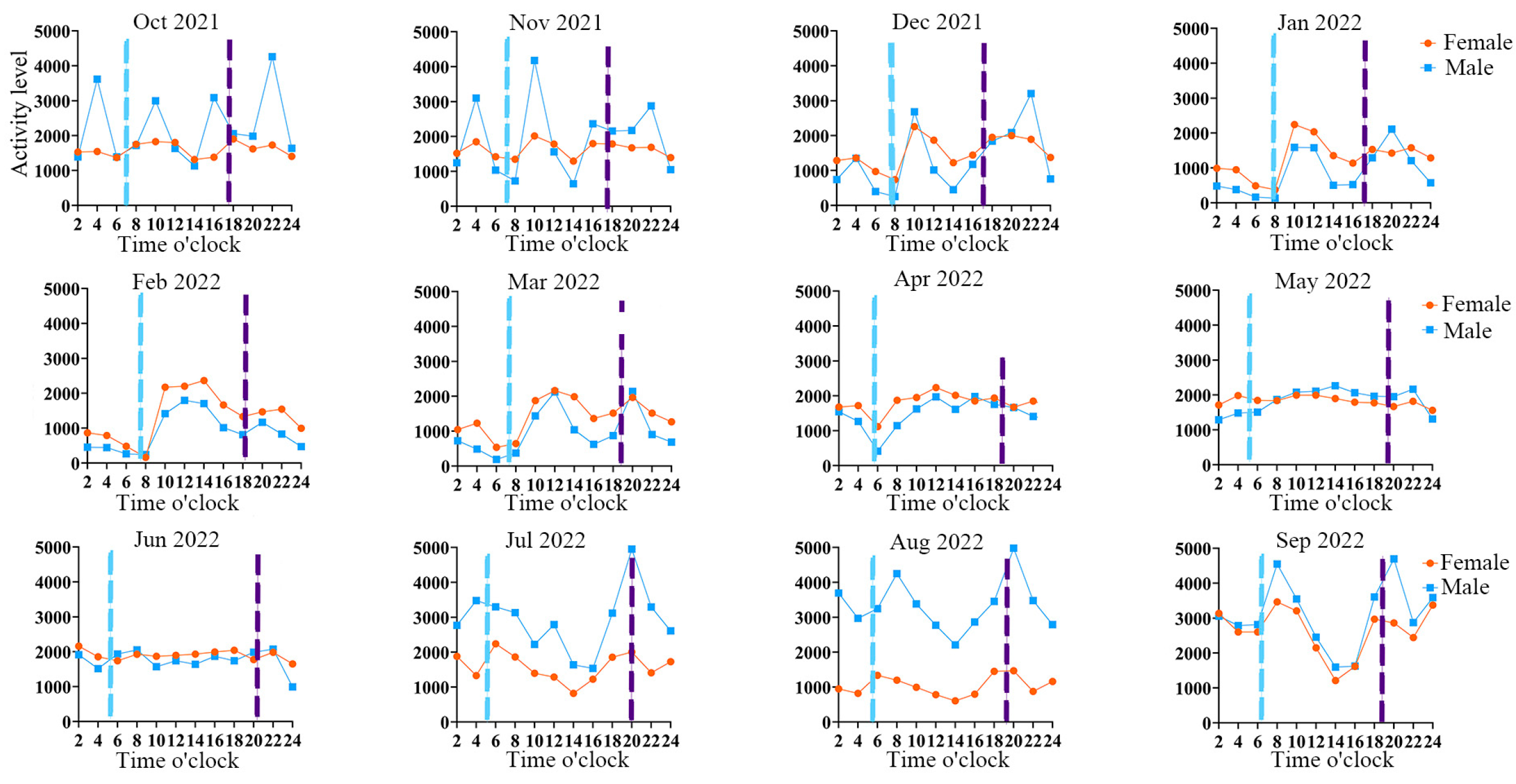

3.3. Activity Rhythms Analysis

The Milu’s activity rhythms exhibit between zero (effectively resulting in zero observable cyclic patterns) and four peak periods (

Figure 7), and Watson's two-sample statistical analysis indicated significant differences in the diurnal activity rhythms between sexes from October 2021 to September 2022 (

p < 0.01). In October 2021 and from April to June 2022, female Milu had effectively resulting in zero observable cyclic patterns in activity peaks. From December 2021 to March 2022, activity levels of both male and female Milu during nighttime were significantly lower than during daytime. From July to September 2022, both males and females displayed two main activity peaks around 08:00 and 20:00, while from December 2021 to March 2022, their peaks occurred around 10:00 and 22:00. During the first three months after release (October to December 2021), there was a clear difference in activity rhythms between sexes: males exhibited 2–4 peaks (at 04:00, 10:00, 16:00, and 22:00), whereas females showed 1–2 peaks (at 10:00 and 20:00). From January to September 2022, although male activity was notably higher than female activity during July to September 2022, the activity rhythms and peak patterns of both sexes remained closely aligned. From Autumn 2021 to Summer 2022, both male and female Milu exhibited significant activity peaks in all four seasons (

p < 0.01). Except for the winter of 2021 when the difference in activity rhythms between sexes was significant(U²= 0.584,

p = 0.028), it was not significant in the other three seasons (

p > 0.05).

Apart from November 2021 and July–September 2022—when the activity rhythm curves of individuals F7 and M10 differ markedly—for the other 37 months, the trends in their activity curves are consistently similar. Observations over 41 consecutive months indicate that during December to March, both F7 and M10 exhibit low activity levels at night (00:00–08:00), with increased activity during daytime hours (10:00–20:00). Except for a pronounced activity peak in F7 during July–September 2022, the activity peaks from April to November are not distinct.

4. Discussion

According to theory, the accumulation of knowledge triggers subsequent changes in animal movement behavior; hence, movement behavior can serve as a key indicator of rewilding progress [

35]. In this study, we collected 110,773 valid location records from 11 Milu and investigated home-range areas, activity rhythms, and dispersal distances of the Milu released in Daqingshan. This is the first study to reveal the behavioral adaptive strategies of a rewilding endangered herbivore that originally inhabited flat, temperate regions when exposed to the harsh winter conditions of mid-altitude mountainous environments.

4.1. Seasonal Variation in Home Range Patterns of the Rewilding Milu

Cervid species exhibit significant differences in home-range areas based on sex, season, and species. In terms of sex, males typically have larger home ranges than females—especially during the breeding season. For example, male red deer (Cervus elaphus) can have home ranges exceeding 200 km², while females occupy only 50–150 km² [

36]; male white-tailed deer expand their ranges to 5–10 km² during the rut, whereas females remain stable at 0.5–3 km² [

37]. Across species, larger cervids such as red deer and moose have significantly larger ranges than smaller species like roe deer (Capreolus capreolus, 0.5–2 km²) and sika deer (Cervus nippon, 1–5 km²) [

38]. Migratory caribou (Rangifer tarandus) may have annual home ranges reaching 5,000–10,000 km² [

39]. Influencing factors include anthropogenic factors (habitat fragmentation [

37], urbanization [

40], and supplemental feeding [

38]) as well as natural factors (food resource distribution [

41,

39] and predation pressure [

36]).

Seasonal variation exhibits two typical patterns: most cervid species—such as North American elk (

Cervus canadensis) (winter 5–10 km² / summer 15–30 km²) and moose (

Alces alces) (winter 10–50 km² / summer 50–200 km²)—show reduced home-range sizes in winter [

36,

41], whereas existing studies indicate that Milu exhibit larger winter and smaller summer home ranges. For example, the Dongting Lake population had a winter home range of 187.39 km² (summer 14.34 km²) [

42], and the Yellow Sea tidal flat population had 28.18 km² in winter versus 3.49 km² in summer [

27], associated with water-level fluctuations and food distribution. In this study, we found that Milu in Daqingshan had smaller winter home ranges and larger summer home ranges, likely due to reliance on supplementary feeding in winter leading to food aggregation [

43], and because males expand home ranges during the rut in summer in search of mates. This contrast reflects the spatial-temporal heterogeneity of resources across regions—for instance, in Poland, moose summer home ranges (9.0 km²) are smaller than winter ones (15.9 km²) [

44]. Sex differences are mainly due to males requiring larger movement ranges because of their body size and physiological needs [

45], whereas females need stable, high-quality food sources for reproduction and rearing. These findings indicate that cervid home-range dynamics are the result of interacting factors including resource distribution, breeding behavior, and human management [

46], which align with the results of our study.

4.2. Plasticity in Dispersal Behavior of the Rewilding Milu

Rewilding animals released into unfamiliar environments must explore their surroundings to acquire essential survival knowledge [

35]. Dispersal behavior post-release varies among species. In the Petit Luberon State Forest in southern France, rewilding roe deer (

Capreolus capreolus) dispersed minimally, remaining largely near the release site—75 % of individuals stayed within 4 km—likely due to favorable terrain and low human disturbance [

47]. Among white-tailed deer in lower latitudes, 33 % of adult males adopted a “mobile strategy,” with activity ranges averaging 65 km²—far exceeding the 3.6 km² of resident individuals—especially during the breeding season [

48]. In our study, dispersal distances increased over time: individuals F7 and M10 extended their dispersal annually, reaching up to 5 km. This indicates gradual acclimatization to the local climate and expanding range. In contrast, Milu in the Dongting Lake plain and wetlands dispersed up to 20 km — vastly exceeding the dispersal observed in Daqingshan [

49].

Based on the “exploration-exploitation trade-off” theory, some scholars have proposed using site fidelity to the release point as a behavioral indicator. Reintroduced individuals transition from an initial phase of slow exploration around the release area to a dual-phase strategy of “large-scale linear movement + core-area intensive activity,” coupled with periodic returns to fixed zones [

35]. Roe deer reintroduced in Petit Luberon State Forest (southern France) exhibited minimal dispersion—roaming behavior near the release point—with activity ranges of only 3–5 km² during the first two months; after 3–6 months, groups began moving to more distant areas (5–15 km²) [

50]. In our study, the deer similarly displayed site fidelity to areas near the release location. Although the winter conditions at the Baishitougou management station in Daqingshan were extremely harsh—cold and lacking fresh grass—the canyons offered unrestricted movement and relatively abundant edible herbs. Despite this, the deer still preferred to return to the release site for human-provisioned forage. GPS trajectory analysis revealed that even during the summer when fresh tender grass was plentiful, the animals frequently lingered near the release site—perhaps because they felt more secure in a familiar environment.

Research shows that, overall, male cervids tend to disperse farther than females [

51,

52], which aligns with the gene flow patterns of most polygynous ungulates: males promote genetic exchange between populations through long-distance movements, while females typically remain near their natal site to reinforce matrilineal bonds. In cervids such as roe deer, males are more inclined to disperse and possess greater dispersal capacity than females [

51,

52]. A study of 158 North American elk revealed that nearly all long-distance dispersers were males, with maximum distances reaching 98 km [

52]. Research on the naturally rewilded Milu population in the Dongting Lake region showed that male groups dispersed more frequently than female and mixed groups; 50% of male dispersal groups comprised only a single adult male, and the mean dispersal distance of male groups (13.73 ± 8.74 km) exceeded that of females (8.95 ± 2.16 km) [

49]. However, in this study, there was no significant difference in dispersal distance between males and females. This may be related to the habitat type at the release site and the provision of supplemental feeding. The Baishitougou management station in Daqingshan is situated in a montane forest ecosystem with steep terrain and multiple canyons; because of the southern fence barrier, deer could only disperse northward along the canyon networks. The deer were also cautious in their movements, even in the food-rich summer, resulting in slow exploratory dispersal. Additionally, landscape connectivity is a key factor affecting population dispersal, and the canyon topography is not conducive to the dispersal of rewilding deer [

53]. Influenced by seasonal food availability and human disturbance, Milu in the Yellow Sea tidal flats spread farther during the lean winter months [

27]. In this study, summer dispersal distances were 7–10 times greater than those in other seasons.

4.3. Crepuscular Peaks and Seasonal Plasticity in Diel Activity Rhythms of the Rewilding Milu

In this study, the diel activity rhythm of the rewilding Milu exhibited between zero (effectively resulting in zero observable cyclic patterns) and four activity peaks, with a pronounced dawn and dusk peak overall across seasons and sexes, classifying them as typical crepuscular animals. The diurnal activity rhythms of cervids typically follow a crepuscular pattern, with primary activity peaks occurring at dawn and dusk (e.g., 05:00–08:00 and 16:00–19:00), but based on species characteristics and environmental pressures they can be subdivided into three main types: crepuscular species (e.g., white-tailed deer (

Odocoileus virginianus)) optimize survival by avoiding daytime heat and nocturnal predator risk [

54]; roe deer shift significantly to night-time activity in areas with strong human disturbance to evade human presence [

55]; and intermittent-activity species (e.g., red deer (

Cervus elaphus)) display multiple short activity bouts throughout the day, an adaptive strategy for responding to seasonal resource fluctuations [

56]. Some species, such as reindeer living in Arctic environments, even show no diel rhythmicity [

57].

Human disturbance is another significant factor affecting diurnal behavioral differences in herbivores [

46]. In the absence of hunting disturbance,

cervid species such as white-tailed deer, moose, and roe deer all display primary activity peaks at dawn and dusk [

58]. When hunting pressure increases, sika deer tend to shift their activity from a dawn-dusk pattern toward more nocturnal behavior [

58]. Moose in non-tourist areas maintain natural crepuscular rhythms, but in tourist zones, their diurnal activity decreases by 70%, while nocturnal activity doubles [

59]. Although the Milu in this study are located in an uninhabited zone without hunting or other human disturbances, they still exhibit noticeable monthly and seasonal differences in their diel rhythms. Many herbivores also exhibit seasonal differences in behavioral rhythms. Light and temperature are important factors in regulating circadian rhythms: large-bodied herbivores often avoid extreme heat by shifting their activities to nighttime [

60]. European roe deer display a mixed nocturnal and crepuscular activity pattern in summer, rather than the typical crepuscular pattern seen in winter, as a behavioral adaptation to heat stress in high-temperature environments [

61]. Based on 41 months of data, Milu showed significantly lower activity levels during the night—from midnight to 08:00—than during the day in the colder period from December to March; from April to November, their nocturnal activity remained relatively high. During the early rewilding period (October 2021–December 2021), the deer exhibited large fluctuations in diel rhythms, and the activity curves for males and females did not align, because this period represented the initial phase of adaptation. Subsequently, the diurnal activity rhythm curves for both sexes became similar, indicating that after three months the deer gradually acclimated their activity rhythms to the local environment.

5. Conclusions

Understanding the behavioral plasticity of rare and endangered species can provide scientific foundations for rewilding programs and improve their success rates. Under harsher conditions, rewilding Milu exhibited high behavioral plasticity in home range size, dispersal behavior, and activity rhythms, adjusting according to season, sex, and environmental conditions. For example, during summer—when food is abundant and it is the breeding season—males showed significantly increased home ranges and dispersal distances, while activity timing remained focused at dawn and dusk. In contrast, during winter—with scarce resources—the home range contracted and activity became highly concentrated (supplementary feeding in winter leading to food aggregation). Differences in sex roles and energy strategies jointly drive these changes, complementing each other: seasonal variations in home range size driven by food availability and reproductive behavior, cautious and site-faithful dispersal behavior in relation to release locations, and flexible diel rhythms—all aid Milu in optimizing foraging and risk avoidance under varying seasonal and environmental pressures. These behavioral patterns collectively reflect the strong behavioral plasticity of captive-bred Milu individuals when they are rewilding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.C.and Z.C.; Data Curation, J.M. and J.B.; Formal Analysis, J.M., B.C., R.S., and H.M.; Funding Acquisition, K.C., Z.C.; Investigation, J.M., Z.C., R.S., H.M. and C.F.; Methodology, K.C., J.B.and Z.Z.; Project Administration, Z.Z. and C.F.; Supervision, Q.Z. and Q.G.; Writing—Original Draft, J.M. and Z.C.; Writing— Review and Editing, J.B., Z.C.and K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Fund of Beijing Municipal Financial Projects [grant numbers: 25CD008, 25CA005] and the Fund of National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFF1306404-1)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Cheng Zong for his invaluable guidance and extend special thanks to Mr. Renbenta Hao and Dr. Hua Ju for their valuable assistance throughout the project.

References

- Chapple, D. G.; Naimo, A. C.; Brand, J. A.; et al. Biological Invasions as a Selective Filter Driving Behavioral Divergence. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 33755. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33755-2.

- Burton, A. C.; Beirne, C.; Gaynor, K. M.; et al. Mammal Responses to Global Changes in Human Activity Vary by Trophic Group and Landscape. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 924–935. [CrossRef]

- Palagi, E.; Bergman, T. J. Bridging Captive and Wild Studies: Behavioral Plasticity and Social Complexity in Theropithecus gelada. Animals 2021, 11, 3003. [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, K.; Fidino, M.; Farris, Z. J.; et al. When the Wild Things Are: Defining Mammalian Diel Activity and Plasticity. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eado3843. [CrossRef]

- Riddell, E. A.; Odom, J. P.; Damm, J. D.; et al. Plasticity Reveals Hidden Resistance to Extinction under Climate Change in the Global Hotspot of Salamander Diversity. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4(7), eaar5471. [CrossRef]

- Charline, C.; Dany, G.; Maxime, A.; et al. Behavioral Variation in Natural Contests: Integrating Plasticity and Personality. Behav. Ecol. 2021, araa127. [CrossRef]

- Finand, B.; Loeuille, N.; Bocquet, C.; et al. Habitat Fragmentation through Urbanization Selects for Low Dispersal in an Ant Species. Oikos 2024, 2024(3), e10325. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H.; et al. Abiotic and Biotic Influences on the Movement of Reintroduced Chinese Giant Salamanders (Andrias davidianus) in Two Montane Rivers. Animals 2021, 11, 1480. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Eom, T.; Lee, D.; et al. Variations in Home Range and Core Area of Red-Backed Voles (Myodes regulus) in Response to Various Ecological Factors. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16704. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carrasco, D.; Tylianakis, J. M.; Lytle, D. A.; et al. Ecological and Evolutionary Consequences of Changing Seasonality. Science 2025, 388, eads4880. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, C. L.; Demarais, S.; Brooks, C. P.; et al. Behavioral Plasticity Mitigates the Effect of Warming on White-Tailed Deer. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10(5), 2579–2587. [CrossRef]

- Geremia, C., Hamilton, E. W., Merkle, J. A. Yellowstone’s free-moving large bison herds provide a glimpse of their past ecosystem function. Science, 2025, 389(6763): 904-908. [CrossRef]

- Seddon, P. J.; Griffiths, C. J.; Soorae, P. S.; et al. Reversing Defaunation: Restoring Species in a Changing World. Science 2014, 345, 406–412. [CrossRef]

- Cartledge, E. L.; Bellis, J.; White, I.; et al. Current and Future Climate Suitability for the Hazel Dormouse in the UK and the Impact on Reintroduced Populations. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2024, 6, e13254. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R. E.; Farquharson, K. A.; Bruford, M. W.; et al. Global Meta-Analysis Shows Action Is Needed to Halt Genetic Diversity Loss. Nature 2025, 638(8051), 704–710. [CrossRef]

- Banes, G. L.; Galdikas, B. M. F.; Vigilant, L. Reintroduction of Confiscated and Displaced Mammals Risks Outbreeding and Introgression in Natural Populations, as Evidenced by Orang-Utans of Divergent Subspecies. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22026. [CrossRef]

- Molloy, S. W.; Burbidge, A. H.; Comer, S.; et al. Using Climate Change Models to Inform the Recovery of the Western Ground Parrot Pezoporus flaviventris. Oryx 2020, 54, 52–61. [CrossRef]

- Warne, R. K.; Chaber, A. Assessing Disease Risks in Wildlife Translocation Projects: A Comprehensive Review of Disease Incidents. Animals 2023, 13, 3379. [CrossRef]

- Mesochina, P.; Bedin, E.; Ostrowski, S. Reintroducing Antelopes into Arid Areas: Lessons Learnt from the Oryx in Saudi Arabia. C. R. Biol. 2003, 326 Suppl. 1, S158–S165. [CrossRef]

- Jung, T. S.; Larter, N. C.; Lewis, C. J.; et al. Wolf (Canis lupus) Predation and Scavenging of Reintroduced Bison (Bison bison): A Hallmark of Ecological Restoration to Boreal Food Webs. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2023, 69, 16. [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Walters, L.; McCallum, J.; Montgomery, R.; et al. Systematic Review of Conservation Interventions to Promote Voluntary Behavior Change. Conserv. Biol. 2022, 37, e14000. [CrossRef]

- Canessa, S.; Ottonello, D.; Rosa, G.; et al. Adaptive Management of Species Recovery Programs: A Real-World Application for an Endangered Amphibian. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 236, 202–210. [CrossRef]

- Frietsch, M.; Loos, J.; Hr, K. L.; et al. Future-Proofing Ecosystem Restoration through Enhancing Adaptive Capacity. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 4736. [CrossRef]

- Muths, E.; Dreitz, V.; et al. Monitoring Programs to Assess Reintroduction Efforts: A Critical Component in Recovery. Anim. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 31, 47–56. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Tian, X.; Zhong, Z.; et al. Reintroduction, Distribution, Population Dynamics and Conservation of a Species Formerly Extinct in the Wild: A Review of Thirty-Five Years of Successful Milu (Elaphurus davidianus) Reintroduction in China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 31, e01860. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.-H.; R.B. (2016). Elaphurus davidianus [EB/OL]. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T7121A22159785. [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Li, C.; et al. Seasonal Home Range Patterns of the Reintroduced and Rewild Female Père David’s Deer Elaphurus davidianus. Biol. Rhythm Res. 2017, 48(3), 485–497. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Jiang, J. J. M.; et al. Causes of Endangerment or Extinction of Some Mammals and Its Relevance to the Reintroduction of Père David’s Deer in the Dongting Lake Drainage Area. Biodiv. Sci. 2005, 13(5), 451–461. https://www.biodiversity-science.net/CN/Y2005/V13/I5/451.

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Seasonal Differences of the Milu’s Home Range at the Early Rewilding Stage in Dongting Lake Area, China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 35, e02057. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z.; et al. Behavioural Rhythms during the Adaptive Phase of Introduced Milu/Père David’s Deer (Elaphurus davidianus) in the Dongting Lake Wetland, China. Pak. J. Zool. 2017, 49, 1657–1664. [CrossRef]

- Beck, B. B.; Wemmer, C. M.; et al. The Biology and Management of an Extinct Species: Père David’s Deer; Noyes Publications: Park Ridge, NJ, USA, 1983; 193. https://lccn.loc.gov/83002364.

- Cao, K.; Qiu, L.; Chen, B.; et al. Chinese Milu Deer; Xue Lin Press: Shanghai, China, 1990.

- Stiegler, J.; Gallagher, C. A.; Hering, R.; et al. Mammals Show Faster Recovery from Capture and Tagging in Human-Disturbed Landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 52381. [CrossRef]

- Sarout.; B. N. M.; Waterhouse, A.; Duthie, C.; et al. Assessment of Circadian Rhythm of Activity Combined with Random Regression Model as a Novel Approach to Monitoring Sheep in an Extensive System. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 207, 26–38. [CrossRef]

- Oded Berger,TAL.; David Saltz.; et al. Using the movement patterns of reintroduced animals to improve reintroduction success, CURR ZOOL , 2014, 60, 515-526. [CrossRef]

- Katie, V. Stopher.; Daniel, H. Nussey.; Tim H. Clutton-Brock.; Fiona Guinness.; Alison Morris.; Josephine.; M. Pemberton.;et al. The red deer rut revisited: female excursions but no evidence females move to mate with preferred males, Behav. Ecol., 2011, 22, 808-818, . [CrossRef]

- Tierson, W C.; Mattfeld, G F.; Sage, R W.;et al.Seasonal Movements and Home Ranges of White-Tailed Deer in the Adirondacks.J. Wildl. Manag , 1985, 49, 760-769. [CrossRef]

- Takii, A .; Izumiyama, S .; Mochizuki, T.;et al.Seasonal Migration of Sika Deer in the Oku-Chichibu Mountains, Central Japan.Mamm. Study , 2012, 37, 127-137. [CrossRef]

- Mcgreer, M T .; Mallon, E E .; Vennen, L M V.;et al.Selection for forage and avoidance of risk by woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) at coarse and local scales.ECOSPHERE , 2016, 6(12). [CrossRef]

- Walter, W.D.; Evans, T.S.; Stainbrook, D.; et al. Heterogeneity of a landscape influences size of home range in a North American cervid. Sci Rep 8, 14667 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Dussault, C .;Courtois .; Réhaume.; Ouellet, J P.;et al.Space use of moose in relation to food availability.Can. J. Zool , 2005, 83(11):1431-1437. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S .; Zhao, Y .; Xu, Z .;et al.Home Range Characteristics of the Released Female Milu (Père David's Deer, Elaphurus davidianus) Population during Different Periods and Effects of Water Submersion in Dongting Lake, China.Pak. J. Zool , 2022, 54(3). [CrossRef]

- Saldo, E A.; Jensen, A J.; Muthersbaugh, M S.; et al. Unintended Consequences of Wildlife Feeders on Spatiotemporal Activity of White-tailed Deer, Coyotes, and Wild Pigs. J. Wildl. Manage , 2024,88. [CrossRef]

- Tomasz, B.; Rafa, K.; Weronika, M L.; et al. Annual Movement Strategy Predicts Within-Season Space Use by Moose. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol , 2021,75. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Bao, H.; Bencini, R.; et al. Macro-Nutritional Adaptive Strategies of Moose (Alces alces) Related to Population Density. Animals , 2019,10:73. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Banjade, M.; Ahn, J.; et al. Seasonal Variations and Sexual Differences in Home Range Sizes and Activity Patterns of Endangered Long-Tailed Gorals in South Korea. Animals , 2025,15. [CrossRef]

- Calenge, C.; Maillard, D.; Invernia, N.; et al. Reintroduction of roe deer Capreolus capreolus into a Mediterranean habitat: female mortality and dispersion. Wildl. Biol , 2005, 11(2): 153-161. [CrossRef]

- Resop, J P.; Hendrix, C.; Wynn-Thompson, T.; et al. Channel Morphology Change after Restoration: Drone Laser Scanning versus Traditional Surveying Techniques. Hydrology, 2024, 11(4): 54. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y C.; Yang, D D.; Zou, S J.; et al. Sex-biased dispersal in naturally re-wild Milu in the Dongting Lake Region, China.Acta Ecol. Sin, 2015, 35(13): 4416-4424. [CrossRef]

- King, S R B.; Gurnell, J; et al. Habitat use and spatial dynamics of takhi introduced to Hustai National Park, Mongolia. Biol. Conserv , 2005, 124(2): 277-290. [CrossRef]

- Coulon, A.; Cosson, J F.; Morellet, N.; et al. Dispersal is Not Female Biased in a Resource-Defence Mating Ungulate, the European Roe Deer. P ROY SOC B-BIOL SCI , 2005,273:341-348. [CrossRef]

- Killeen, J.; Thurfjell, H.; Ciuti, S.; et al. Habitat Selection During Ungulate Dispersal and Exploratory Movement at Broad and Fine Scale with Implications for Conservation Management. Mov. Ecol , 2014,2:13. [CrossRef]

- La Morgia, V.; Malenotti, E.;Badino, G.; et al. Where do we go from here? Dispersal simulations shed light on the role of landscape structure in determining animal redistribution after reintroduction. Landscape Ecol , 2011, 26: 969-981. [CrossRef]

- Cueva-Hurtado, L.; Jara-Guerrero, A.; Cisneros, R.; et al. Activity patterns of the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in a neotropical dry forest: changes according to age, sex, and climatic season. Therya, 2024, 15(2): 242-252. [CrossRef]

- Thel, L.; Garel, M.; Marchand, P.; et al. Too hot or too disturbed? Temperatures more than hikers affect circadian activity of females in northern chamois. Anim. Behav , 2024, 210: 347-367. [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.I.S.Activity patterns of red and roe deer: differences between sexes. MS thesis. Universidade de Coimbra (Portugal), 2021.

- Loe, L E, Bonenfant, C, Mysterud, A, et al. Activity pattern of arctic reindeer in a predator-free environment: no need to keep a daily rhythm. OECOLOGIA , 2007, 152, 617-624. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.; Takahashi, H.; Igota, H.; et al. Effects of Culling Intensity on Diel and Seasonal Activity Patterns of Sika Deer (Cervus nippon). Sci. Rep. 2019,9. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, W.; Göran E.; Holger, D. The impact of human recreational activities: moose as a case study. Alces 2011, 47, 17-25.

- Vallejo-Vargas, A.F.; Sheil, D.; Semper-Pascual, A., et al. Consistent Diel Activity Patterns of Forest Mammals among Tropical Regions. Nat. Commun. 2022,13. [CrossRef]

- Eom, T.; Lee, J.; Lee, D.; et al. Adaptive Response of Siberian Roe Deer Capreolus Pygargus to Climate and Altitude in the Temperate Forests of South Korea. Wildl. Biol. 2023,2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).