1. Introduction

Diet diversity (or variety) is defined as the number of different foods or food groups consumed over a given reference period [

1]. Diversity within a specific food group – such as, diversity of fruits and vegetables or diversity of food allergens, does not directly reflect overall diet diversity, but may be considered in combination with other measures to provide a more comprehensive assessment [

1,

2,

3].

Diet diversity does not directly reflect diet quality, however, studies have demonstrated that greater diet variety is associated with higher nutrient intake, improved growth outcomes, and increased microbiome diversity [

1,

4]. The European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) systematic review suggested that higher diet diversity in infancy may be linked to a reduced risk of allergic diseases later in life [

1]. Furthermore, recent EAACI guidance on healthy complementary feeding practices for allergy prevention in developed countries emphasized that complementary foods introduced in infancy should be diverse, as greater diet diversity has been shown to lower the prevalence of food allergy by the age of 6-10 years [

5].

In children with confirmed food allergy (FA), elimination of the relevant allergens from the child’s diet or from the breastfeeding mother’s diet constitutes the first-line treatment [

6,

7,

8]. While it is effective in preventing allergic reactions, it may be associated with delayed introduction of complementary foods, an increased risk of nutritional deficiencies, growth faltering, feeding difficulties, and social isolation [

9,

10].

Although elimination diets introduced for suspected or confirmed FA in children may influence overall diet diversity, the available evidence remains limited. In one case-control study involving children aged 3-18 years with physician-diagnosed IgE-mediated FA, diet diversity was comparable to that observed in children with respiratory allergies consuming a regular diet (n=160) [

11]. In another cross-sectional study of children aged 8 to 27 months, diet variety was lower in those following a cow’s milk-free diet compared with those on an unrestricted diet (n=126) [

12].

Diet diversity during early childhood is influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including infant feeding practices (e.g., breastfeeding versus formula feeding), timing of exposure to different foods and flavors, and socioeconomic status [

13,

14,

15]. Although, early feeding practices may affect diet diversity, most research to date has focused on infants, while data on diet diversity among nursery-aged children remain scared. In Poland, the PITNUTS study assessed feeding practices in the general population of children aged 5 to 36 months [

16]; however, it did not specifically address feeding practices in children with food allergies, and evidence in this area remains limited.

Current evidence on diet diversity and feeding practices in children with food allergy is limited and inconsistent. To address this gap, we conducted a cross-sectional survey aimed to evaluate overall diet diversity and feeding practices in children aged 13–36 months attending nurseries following elimination diets due to food allergy, compared to healthy peers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional survey was conducted on a convenience sample of participants using both online and paper-based questionnaires.

2.2. Participants

Children aged 13–36 months attending public or private nurseries in Warsaw and Olsztyn were eligible for inclusion in the study without restrictions regarding age (within the range), sex, ethnicity, nationality, parental education, or socioeconomic status.

The

exposure group consisted of children with physician-confirmed FA, who were currently following an elimination diet, regardless of the diagnostic method used. In Polish nurseries, a medical certificate confirming FA is required to introduce an elimination diet. Therefore, all children had such documentation. Although the oral food challenge (OFC) is considered the gold standard for FA diagnosis [

6], it is not routinely performed in Poland. In a 2020 survey conducted by our research team, 72.6% of physicians reported not using OFC to confirm FA [

17]. Nevertheless, elimination diets excluding common allergens are frequently introduced in children, most often due to strong parental beliefs regarding the causal relationship between food consumption and symptoms [

18]. For the purpose of this study we included children on elimination diets, with OFC - confirmed FA, as well as those without OFC. For all children in the exposure group, parents reported the diagnostic method, symptoms and history of anaphylaxis. IgE- and non-IgE-mediated FA were not differentiated.

The control group included healthy children on unrestricted diets, recruited from the same nurseries as those in the exposure group.

Exclusion criteria were comorbidities significantly affecting dietary intake or nutritional status (e.g., celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease), elimination diets for non-medical reasons (e.g. religious, ethical, vegetarian), enteral or parenteral nutrition, preterm birth (<37 weeks), or birth weight <2500 g.

No incentives for participation were provided, and respondents were informed that they could withdraw from the survey at any time.

2.3. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire was developed by members of Food Allergy Section of the Polish Society of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, including two pediatric gastroenterologists (A.H., E.J.-C.) and one dietitian (A.S.), all experienced in child nutrition and allergy research.

The questionnaire collected general demographic and anthropometric data (weight, height) as well as information on breastfeeding, formula feeding, consumption of plant-based beverages, introduction of complementary foods and potentially allergenic foods, and supplement use. In addition, two validated instruments were incorporated: the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ-6)[

19] and the Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale (MCH-FS)[

20].

Anthropometric measures, including body weight and length/height, were reported by parents. Although direct measurement by researchers would have been preferable, prior to initiating the survey we confirmed with the nurseries that children’ weight and length/height are routinely measured by nursing staff and communicated to parents. Based on parent-reported values, a pediatrician (A.H.) calculated weight-for-age and length/height-for age percentiles using the World Health Organization (WHO) growth charts [

21].

The frequency of consumption of 55 individual food items over the past month, grouped into 11 food categories, was assessed using the validated Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ-6) [

19]. The FFQ-6 is a standardized instrument designed to evaluate habitual frequency of food consumption. For each food item, parents reported how often it was consumed using the following categories: never or almost never, less than once per week, once per week, 2–6 times per week, once per day, and several times per day. A 2017 systematic review confirmed that the FFQ is valid as a tool for estimating dietary intake in children aged 12-36 months [

19].

Each parent was asked to complete the Polish version of the Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale (MCH-FS), a questionnaire validated for children aged 6 months to 6 years [

20]. The MCH-FS consists of 14 items addressing various aspects of feeding, including parental concerns about feeding and child growth, parental feeding strategies, children’s oral motor and sensory functions, appetite, mealtime duration, and the impact of feeding on family relationships. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale, and the total score is calculated by summing the individual item scores.

Recruitment was conducted between March 2025 and June 2025 in nurseries located in Warsaw (A.H. and A.S.) and Olsztyn (E.J.-C.). For parents of children attending nurseries in Warsaw, the questionnaire was available online via the Warsaw Nurseries website and app, whereas in Olsztyn the majority of questionnaires were collected in paper form.

2.4. Outcomes

All study outcomes referred to feeding practices, overall diet diversity and feeding difficulties in children aged 13-36 months, and included the following:

- ▪

nutritional status, assessed using the WHO weight-for-age and length/height-for-age percentiles;

- ▪

diet diversity measures, including WHO Minimum Dietary Diversity, overall diet diversity, food group diversity, and food item diversity (

Table 1);

- ▪

specific food group diversity measures, including food allergen diversity, and fruit and vegetable diversity (Table 1);

- ▪

percentage of children with feeding difficulties, defined as those achieving at least 46-points of total score on the MCH-FS [

20];

- ▪

feeding practices, including: breastfeeding and formula feeding (i.e., duration and volume of exclusive and any breastfeeding, formula feeding, number of daytime and nighttime feeds), consumption of plant-based beverages, and complementary feeding practices (i.e., timing of solid foods introduction and introduction of potentially allergenic foods);

- ▪

supplements use.

In the group of children with suspected or confirmed FA, we additionally collected the following data: family risk factors for reported FA symptoms, age and method of diagnosis, the specialist responsible for FA diagnosis and follow-up, the proportion of children with anaphylaxis, asthma, or atopic dermatitis, the proportion who had been consulted by a dietitian, and the use of hypoallergenic formulas. Furthermore, we assessed the proportion of children who had reintroduced processed forms of milk and egg, as well as, the proportion who achieved tolerance at each step of the milk and egg ladder. These data were reported separately for children with and without OFC-confirmed FA.

2.5. Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee Medical University of Warsaw (AKBE/281/2024). All participants provided voluntary informed consent to participate in the study and were informed that the data would be analyzed anonymously. Demographic data were collected only in broad categories.

2.6. Sample Size

There is a lack of epidemiological data in Poland on which to base a precise sample size calculation for this type of study. However, in a similar observational study conducted in children aged 3–18 years, which assessed diet diversity and body weight, 100 children with FA (exposure group) and 60 children with respiratory allergies (control group) were included [

11].

In a comparable Polish study conducted in the under-3 age group in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian region, the FA group included 35 children, while the healthy control group consisted of 20 children [

24].

Based on these data, a sample size of at least 200 children was considered sufficient for the purposes of the present study.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software in version 4.4.2. Descriptive statistics were used to present the participants’ baseline characteristics. Nominal variables are presented described as the number of patients (n) and percentages (%). Continuous variables are reported as means and standard deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate (depending on data distribution). For all outcomes, mean or median differences (MD) between groups, or relative risks (RR), were calculated, each with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Comparisons and associations were assessed using appropriate tests depending on distribution normality and variance homogeneity. Normality was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk test along with skewness and kurtosis. All tests were two-tailed with a significance level α = 0.05. Homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene’s test. For comparisons between two groups, t Student test was applied for normally distributed data with equal variances, t Welch test was used for unequal variances and Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed variables. For categorical data, associations were tested using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, depending on expected frequencies. In analyses involving more than two groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for parametric data and Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction was used for non-parametric data. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

Data from the online and paper-based questionnaires were available for 403 responders. Fifteen responses were excluded due to prematurity, very low birth weight and/or substantial missing data. Therefore, data from 388 parents – 61 with children on elimination diets due to FA and 327 with healthy children consuming unrestricted diet (non-FA), were included in the final analysis.

3.1. Characteristics of Survey Population

Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2. The majority of children were recruited in Warsaw (82.9%). Children in the exposure group were slightly younger than those in the control group (median = 23 [IQR 19-31] months vs 25 [IQR 20-31]) months; mean difference [MD] = -2.0 months, 95% CI: -4.0 to 0.0, p = 0.046). During their time at nurseries most children (96.4%) consumed only meals prepared at the nursery. A higher proportion of children on an elimination diet due to FA consumed meals prepared at home and provided by parents, either partially (4.9%, n=3 vs 0.9%, n=3) or fully (6.6%, n=4 vs 1.2%, n=4), compared with the non-FA group. The exposure and non-exposure groups did not differ in other characteristics, including sex distribution, mean body weight and height, or parental economic status.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study population.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study population.

| Variable |

Total

(n=388)

|

With

Food Allergy

(n=61)

|

Without

Food Allergy (n=327)

|

MD

(95% CI)

|

p |

| Recruitment site: Warsaw n (%) |

321 (82.7) |

54 (88.5) |

267 (81.7) |

- |

0.282 |

| Age, months, median (IQR) |

25.0 (19.0;31.0) |

23.0 (16.0;30.0) |

25.0 (20.0;31.0) |

-2.0 (-4.0;0.0) |

0.046 |

| Gender: male, n (%) |

186 (47.9) |

36 (59.0) |

150 (45.9) |

- |

0.081 |

| Body weight, kg, mean±SD * |

12.7±2.1 |

12.5±2.3 |

12.7±2.0 |

-0.2 (-0.7;0.4) |

0.624 |

| Height, cm, median (IQR) ** |

90.0 (84.0;94.0) |

88.0 (83.0;94.5) |

90.0 (85.0;94.0) |

-2.0 (-4.0;1.0) |

0.213 |

| Meals in nurseries, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Only foods provided by the nursery |

374 (96.4) |

54 (88.5) |

320 (97.9) |

- |

0.003 |

| Foods provided by the nursery and delivered by parents (prepared at home) |

6 (1.5) |

3 (4.9) |

3 (0.9) |

| Only foods delivered by parents (prepared at home) |

8 (2.1) |

4 (6.6) |

4 (1.2) |

| Economic situation, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sufficient for daily functioning, allowing for savings. |

278 (71.6) |

43 (70.5) |

235 (71.9) |

- |

0.402 |

| Sufficient for daily functioning, but not for savings. |

84 (21.6) |

14 (23.0) |

70 (21.4) |

| Sufficient for daily functioning, but requires giving up certain expenses. |

18 (4.6) |

2 (3.3) |

16 (4.9) |

| Requires a very frugal lifestyle to save for larger expenses. |

4 (1.0) |

0 (0.0) |

4 (1.2) |

| Money is only sufficient for basic needs. |

4 (1.0) |

2 (3.3) |

2 (0.6) |

3.2. Characteristics of Subgroup with Food Allergies

All children on elimination diet had a physician-confirmed FA diagnosis (n=61); however, only 39.3% had OFC-confirmed FA (Table S1). Almost half of parents reported using positive sIgE results to food allergens (45.9%) and/or clinical symptoms to confirm the FA diagnosis.

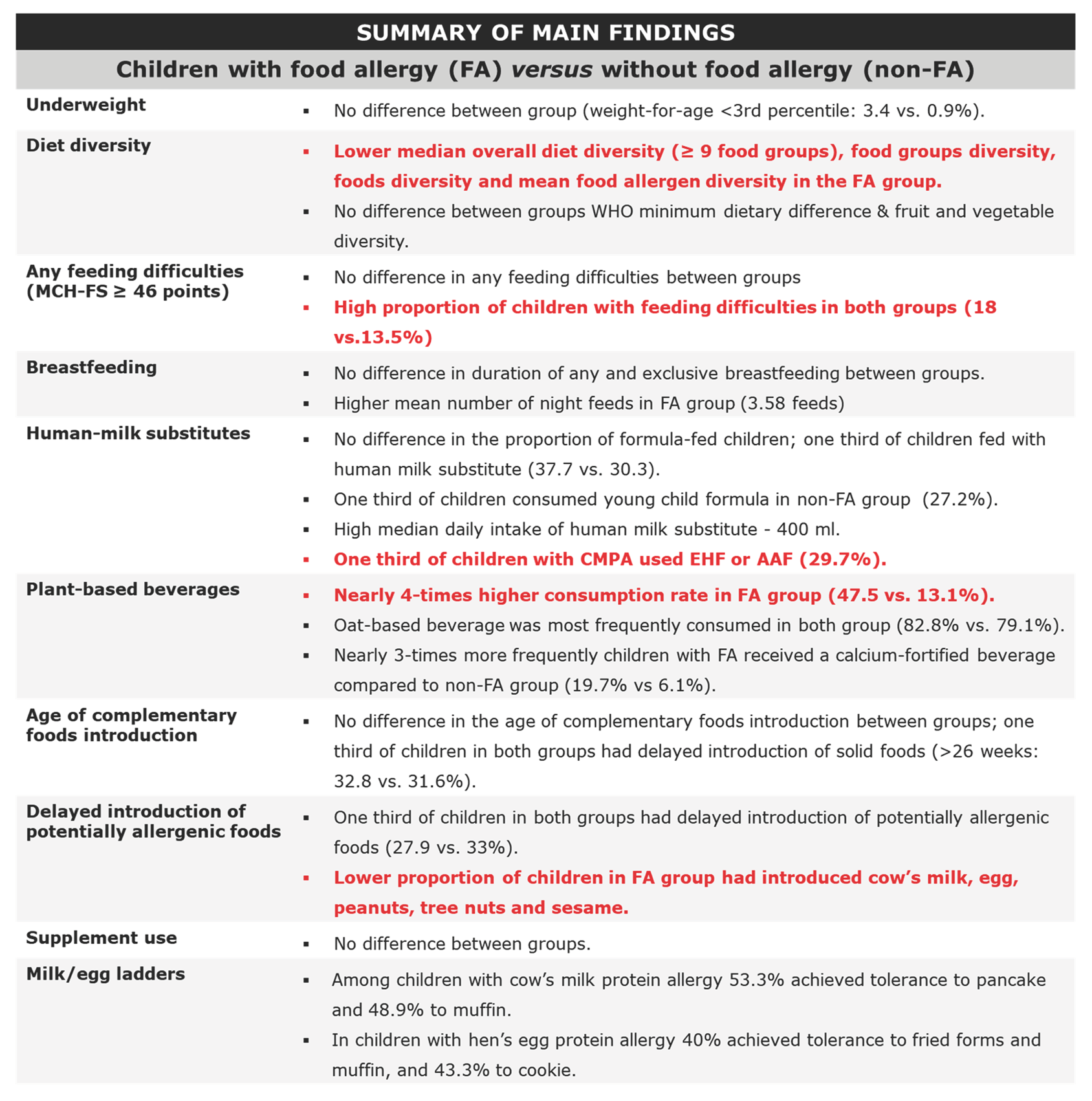

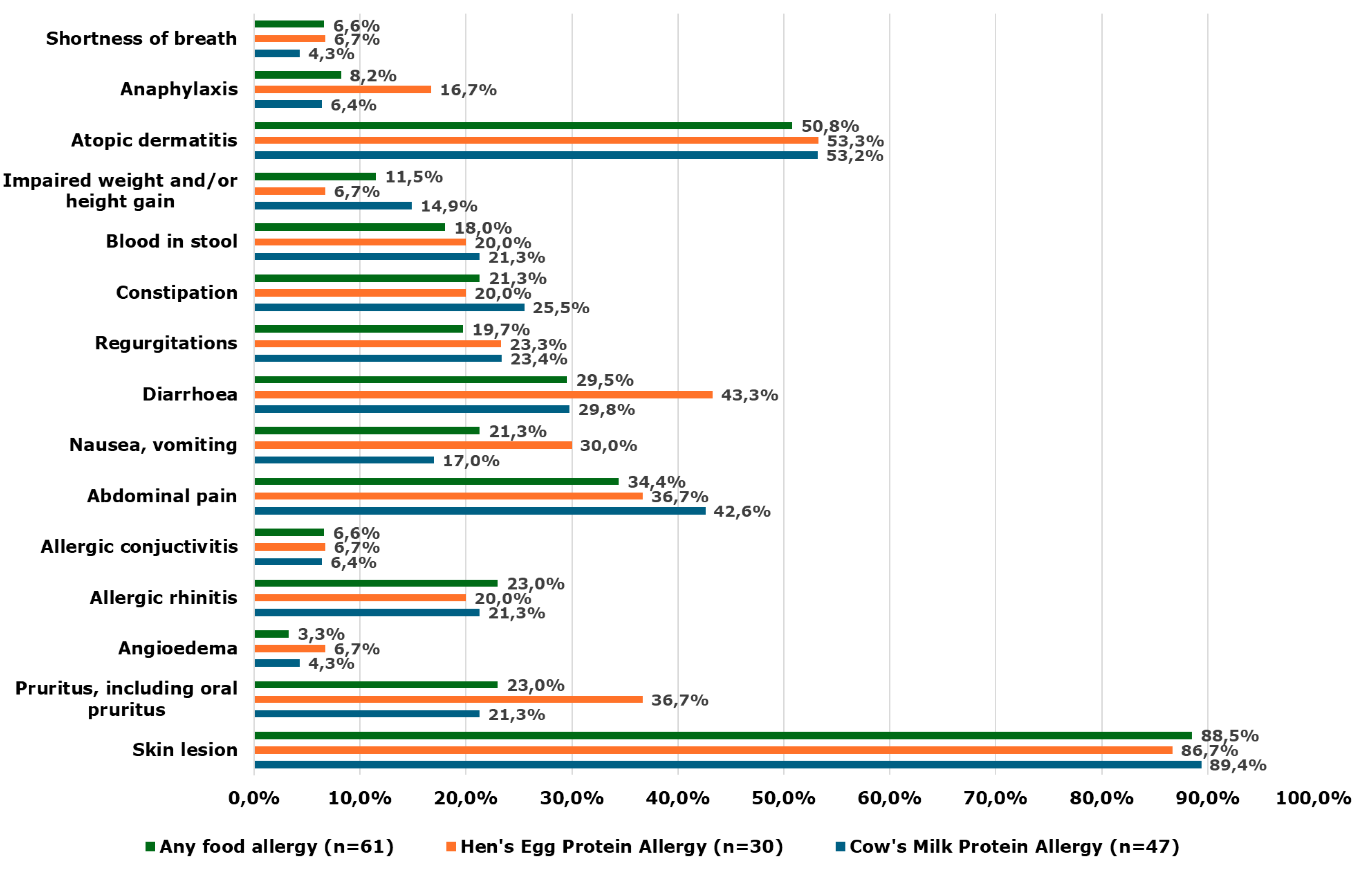

Most parents reported that their children had cow’s milk proteins allergy (CMPA) (77%), almost half of children had hen’s egg protein allergy (49.2%); Allergies to other foods were less common, including: peanuts (16.4%), soy (13.1%), nuts (11.5%), wheat (6.6%) and fish (3.3%).

Symptoms of food allergies declared by parents are presented in

Figure 1.

3.1.1. Children with Cow’s Milk Proteins Allergy (CMPA)

A total of 47 respondents reported that their children had a physician-diagnosed CMPA. According to FA diagnostic methods, only one third of parents declared that CMPA diagnosis was confirmed by OFC (34%), nearly one third (29.8%) reported positive sIgE results for cow’s milk, and in almost half diagnosis was based mainly on clinical symptoms (44.7%). Only a small proportion of parents reported the use of component-resolved diagnostics or skin prick tests (Table S2).

CMPA was diagnosed by an allergologist in half of the children, with similar proportions in the OFC-confirmed and non-OFC subgroups (56.2 and 50.0%, respectively) (Table S3). More than one-third of children were consulted by a pediatrician (37.5% vs. 42.9%), while only a minority was diagnosed by a gastroenterologist (6.2% vs. 3.6%) or other specialist (3.6%). The median age of CMPA diagnosis was comparable between the two groups (5 vs. 6 months).

Most parents reported that they children had atopic dermatitis (75% in the OFC-confirmed CMPA subgroup vs 54.8% in the non-OFC subgroup). Anaphylaxis (6.2 vs 6.5%; RR = 1.0, 95% CI, 0.1 to 9.9, p > 0.999) and asthma (6.2 vs 9.7%; RR = 0.7, 95% CI, 0.1 to 5.7, p > 0.999) were reported only in a few cases in both groups. Most children were not consulted by a dietitian in either the OFC-confirmed or non-OFC-confirmed CMPA groups (75 and 61.3%, respectively).

A significant proportion of children had coexisting food allergies to more than one food allergen –

Figure 2.

3.1.2. Children with Hen’s Egg Protein Allergy (HEA)

A total of 30 parents reported that their children had a physician-confirmed HEA. Among the reported diagnostic methods, positive sIgE results to hen’s egg were the most common (60.0%) (Table S4). Only one-third of children had OFC-confirmed HEA (33.3%) while a smaller proportion were diagnosed based on clinical symptoms (20%), component-resolved diagnostics (16.7%) or skin prick tests (10%).

In two third of children, HEA was confirmed by an allergologist, with similar proportions in the OFC-confirmed and non-OFC subgroups (60 vs 70%, respectively). Less frequently, it was diagnosed by pediatrician (40 vs 20%, respectively) and other specialist (10%, only in non-OFC group) (p = 0.449) (Table S5). The median age at HEA diagnosis was similar between the two subgroups (7.5 vs 7 months; MD = 0.5, 95% CI: -4.0 to 3.0; p = 0.791).

Half of parents reported that their children had atopic dermatitis (50% in both subgroups). Anaphylaxis and asthma were reported only in a few cases (16.7% and 10%, respectively). About half of children were not consulted by dietitian in either the OFC-confirmed or non-OFC-confirmed HEA groups (50 and 60%, respectively).

3.2. Nutritional Status (Weight and Length/Height-For-Age Percentiles)

No significant differences were observed between the FA and non-FA groups in the proportion of children at each WHO percentiles cut-off points for weight-for-age and length/height-for-age (Table 3). Underweight (≤3 percentile, WHO growth standards) was identified in a minority of children in both groups (3.4% in the FA group and 0.9% in the non-FA group). Similarly, stunting (≤3 percentile) was infrequent (1.7% in the FA group and 3.5% in the non-FA group). In contrast, high body mass (>85th percentile) affected 25.4% of children in the FA group compared with 16.8% in the non-FA group; however, this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Proportion of children at each WHO percentiles cut-off points for weight-for-age and height-for-age.

Table 3.

Proportion of children at each WHO percentiles cut-off points for weight-for-age and height-for-age.

| Variable |

Total

(n=388)

|

With

Food Allergy

(n=61)

|

Without

Food Allergy

(n=327)

|

p |

|

Weight-for-age,percentile, n (%)

|

| ≤3 |

5 (1.3) |

2 (3.4) |

3 (0.9) |

0.178 |

| 3-15 |

21 (5.6) |

2 (3.4) |

19 (6.0) |

0.551 |

| 15-85 |

281 (74.9) |

40 (67.8) |

241 (76.3) |

0.225 |

| 85-97 |

49 (13.1) |

12 (20.3) |

37 (11.7) |

0.111 |

| >97 |

19 (5.1) |

3 (5.1) |

16 (5.1) |

>0.999 |

|

Height-for-age,percentile, n (%)

|

| ≤3 |

12 (3.2) |

1 (1.7) |

11 (3.5) |

0.700 |

| 3-15 |

29 (7.8) |

4 (6.8) |

25 (8.0) |

0.958 |

| 15-85 |

204 (54.8) |

36 (61.0) |

168 (53.7) |

0.370 |

| 85-97 |

72 (19.4) |

10 (16.9) |

62 (19.8) |

0.741 |

| >97 |

55 (14.8) |

8 (13.6) |

47 (15.0) |

0.929 |

3.3. Diet Diversity

WHO minimum dietary diversity.

The median WHO minimum dietary diversity score was statistically significantly lower in the FA group compared with the non-FA group (MD = 0.0 food groups; 95%CI: -1.0 to 0.0, p<0.001), however, this difference was not clinically meaningful (Table 4). WHO minimum dietary diversity defined as ≥5 consumed food groups consumed by a child was achieved in nearly all children (98.4% vs 100%), with no difference between groups.

Overall diet diversity.

Children on an elimination diet due to FA had a lower median overall diet diversity score compared with children on an unrestricted diet (MD = -1.00 food groups; 95% CI, -2.00;-1.00, p<0.001).

Food groups diversity.

A lower median food groups diversity score was also observed in the FA group compared with the non-FA group (MD = -1.0 food groups, 95%CI: -1.0 to -1.0, p<0.001). However, the extremely narrow confidence interval suggests that this finding should be interpreted with caution and may be clinically insignificant. The proportion of children achieving a diverse diet (≥ 9 food groups) was 15% lower in the FA group compared with the non-FA group (83.6% vs 98.5%; RR = 0.9, 95% CI: 0.8 to 1.0, p<0.001).

Foods diversity.

Children in the FA group had a significantly lower median foods diversity score compared with those in the non-FA group (MD = -4.0 foods, 95% CI: -5.0 to -2.0, p < 0.001).

3.4. Specific Food Groups Diversity

Food allergen diversity.

Children in the FA group had lower mean food allergen diversity score compared with those in the non-FA group (MD = -0.9, 95% CI: -1.4 to -0.5, p < 0.001). The proportion of children with a high food allergen diversity score, defined as ≥5 potentially allergenic foods introduced, was 15% lower in the FA group compared to the non-FA group (72.1% vs 85.0%; RR = 0.9, 95% CI: 0.7 to 1.0, p = 0.023).

Fruit and vegetable diversity.

No significant differences were observed in the median fruit and vegetable diversity score between the FA group and the non-FA group (MD = 0.0, 95% CI: 0.0 to 0.0, p = 0.622). A high fruit and vegetable diversity, defined as ≥4 food groups, was achieved in both groups (95.1 versus 93.6%).

3.5. Feeding Difficulties

No significant differences were observed between the FA group and the non-FA group in the proportion of children with feeding difficulties (p = 0.470), defined as a total score of MCH-FS ≥ 46, Nevertheless, the proportion of children with feeding difficulties was significant in both groups (median = 18 versus 13.5%, n=386;

Table 4). No difference was observed between groups in the median MCH-FS total score (30.0 versus 28.0, respectively, p = 0.117).

3.6. Breastfeeding, Formula Feeding and Complementary Feeding Practices

3.6.1. Any and Exclusive Breastfeeding

No significant differences were observed between the FA group and the non-FA group in the duration of any or exclusive breastfeeding (Table 5). Approximately one fifth of children were still breastfed in both groups (19.7%, n=12 in the FA group; 21.1%, n=61 in the non-FA group). The median number of daytime human milk feeds was similar in both groups (median = 5 vs 4 feeds; MD = 1.0; 95% CI: 0.0 to -4.0, p = 0.056; n=72). However, the mean number of nighttime feeds was higher in the FA group compared with the non-FA group (3.6 vs 2.4 feeds; MD = -1.2; 95%CI: 0.2 to 2.1, p=0.015; n=70).

3.6.2. Formula Feeding

There was no significant difference in the proportion of children who were formula-fed between the FA group and non-FA group (37.7 vs 30.3%, respectively, n=389). However, the groups differed significantly regarding the type of human milk substitutes used.

Among formula-fed children, hypoallergenic human milk substitutes (amino acid formula [AAF], extensively hydrolyzed formula [EHF] and hypoallergenic formula [HA]) were used more frequently in the FA group compared with non-FA group (13% [n=3] vs 0.0%, 47.8% vs 2.1% [n=2], and 4.3% [n=1] vs 0.0% respectively; n=122). Conversely, young child formula was used less frequently in the FA group than in the non-FA group (21.7% [n=5] vs 92.7%; n=122). Follow-on formula and goat’s milk formula were used more commonly in the FA group (8.7 [n=2] vs 2.1% [n=2] and 4.3 [n=1] vs 3.1% [n=3], respectively; n=122).

The median daily intake of infant or hypoallergenic formula was similar in both group (400 ml; n=120), as was the median daily number of feeds (2 versus 2.1; n=120).

3.6.2.1. Hypoallergenic Formula in Children with Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy

One third of children with CMPA used human milk substitute (37.5 vs 25.8%, in the OFC-confirmed and non-OFC groups, respectively; RR = 1.5, 95% CI: 0.6 to 3.5, p = 0.621) (Table S3). The median daily intake of human milk substitutes among children with CMPA was high in both groups (350 vs 325 mL,; MD = 25.0, 95% CI: -50.0 to 300.0; p = 0.414).

3.6.3. Plant-Based Beverages

The proportion of children consuming plant-based beverages was nearly four times higher in the FA group compared with the non-FA group (47.5% vs 13.1%, RR = 3.6, 95%CI: 2.5 to 5.3, p < 0.001; n=388). Soy (9.8%, n=6 vs 2.4%, n=8, RR=4.0, 95% CI: 1.5 to 11.2, p = 0.013), almond (14.8%, n=9 vs 4.0%, RR=3.7, 95% CI: 1.7 to 8.3, p = 0.003) and oat drinks (39.3% vs 10.4%, RR=3.8, 95% CI: 2.4 to 5.9, p < 0.001) were consumed significantly more frequently by children with FA compared with those without FA. Coconut drinks were reported only in the FA group (16.4%). Oat-based beverages were the most frequently consumed plant-based beverage in both groups (39.3 vs 10.4%,; n=388).

Among children who consumed plant-based beverages, fewer than half received calcium-fortified products (41.4% [12/29] vs 46.5% [20/43]; n=72). Children with FA received calcium-fortified beverages three times more frequently compared to those without FA (19.7% vs 6.1%, RR = 3.2, 95%CI: 1.7 to 6.2, p = 0.001; n=388). The median daily intake of plant-based beverages was similar in both groups (110 versus 100 ml; n=68). Among children with CMPA, half consumed plant-based beverages (55.3%, n=47).

3.6.4. Complementary Feeding Practices

The mean number of meals consumed per day was similar between the FA group and the non-FA group (4.4 vs 4.6; MD = -0.2, 95% CI: -0.5 to 0.1; n=389). No significant difference was observed between groups in the age of complementary feeding introduction (p = 0.066; n=387). The majority of children in both groups were introduced to complementary foods between 17 and 26 weeks (62.3 vs 60.1%). However, in approximately one-third of children, the introduction of solid foods was delayed beyond 26 weeks (32.8 vs. 31.6%; n=387).

3.6.4.1. Introduction of Potentially Allergenic Foods

The timing of introduction of potentially allergenic foods was similar in the FA and non-FA groups, with most children introduced to these foods concurrently with other solid foods (67.2 vs 66.1%; n=388). However, in approximately one-third of children, the introduction of potentially allergenic foods was delayed (27.9 vs 33.0% n=388) (Table 5).

With regard to specific allergens, the proportion of children who had cow’s milk introduced into their diet was 24% lower in the FA group compared to the non-FA group (73.8% vs 96.6%, RR = 0.8, 95%CI, 0.7 to 0.9, p<0.001). Similarly, eggs were introduced in 17% fewer children in the FA group compared with the non-FA group (82.0% vs 98.8%; RR = 0.8, 95% CI: 0.7 to 0.9, p<0.001). Peanuts and tree nuts were also introduced less frequently in the FA group compared with the non-FA group (50.8% vs 70.0%, RR = 0.7, 95%CI: 0.6 to 0.9, p=0.005; and 54.1% vs 69.7%, RR = 0.8, 95%CI: 0.6 to 1.0, p=0.025, respectively). Likewise, sesame was introduced 23% less often in the FA group compared with the non-FA group (52.5% versus 68.5%, RR = 0.8, 95%CI: 0.6 to 1.0, p=0.023).

Table 5.

Feeding practices of children with and without food allergy (n=388).

Table 5.

Feeding practices of children with and without food allergy (n=388).

| Variable |

With

Food Allergy (n=61)

|

Respondents, n |

Without

Food Allergy (n=327)

|

Respondents, n |

MD/RR (95% CI) |

p |

| Breastfeeding duration |

| Duration of any breastfeeding, n (%) |

|

59 |

|

289 |

|

|

| <1 month |

10 (16.9) |

|

29 (10.0) |

|

- |

0.427 |

| 1.5-5 months |

10 (16.9) |

|

57 (19.7) |

|

| 6 months |

4 (6.8) |

|

22 (7.6) |

|

| 6-12 months |

19 (32.2) |

|

78 (27.0) |

|

| >12 months |

16 (27.1) |

|

103 (35.6) |

|

| Duration of exclusive breastfeeding, n (%) * |

|

53 |

|

275 |

|

|

| <1 month |

12 (22.6) |

|

73 (26.5) |

|

- |

0.418 |

| 2-5 months |

11 (20.8) |

|

50 (18.2) |

|

| 6 months |

21 (39.6) |

|

125 (45.5) |

|

| ≥12 months |

9 (17.0) |

|

27 (9.8) |

|

| Number of breastfeedings per day, median (IQR) * |

5.0 (4.0;9.0) |

11 |

4.0 (3.0;6.0) |

61 |

1.0 (0.0;4.0) |

0.056 |

| Number of breastfeedings at night, mean±SD * |

3.6±1.6 |

12 |

2.4±1.5 |

58 |

1.2 (0.2;2.1) |

0.015 |

| Formula feeding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fed with human milk substitute, n (%) |

23 (37.7) |

61 |

99 (30.3) |

327 |

1.25 (0.9;1.8) |

0.319 |

| Type of human milk substitute, n (%) * |

|

23 |

|

99 |

|

|

| AAF |

3 (13.0) |

|

0 (0.0) |

|

- |

<0.001 |

| EHF |

11 (47.8) |

|

2 (2.1) |

|

| HA |

1 (4.3) |

|

0 (0.0) |

|

| Young child formula |

5 (21.7) |

|

89 (92.7) |

|

| Follow-on formula |

2 (8.7) |

|

2 (2.1) |

|

| Goat milk formula |

1 (4.3) |

|

3 (3.1) |

|

| Human milk substitute, intake per day, ml, median (IQR) |

400.0 (260.0;520.0) |

23 |

400.0 (240.0;540.0) |

97 |

0.0 (-80.0;120.0) |

0.794 |

| Number of feedings with human milk substitute per day, mean±SD |

2.0±1.1 |

22 |

2.1±1.1 |

98 |

-0.1 (-0.6;0.4) |

0.697 |

| Plant-based beverages |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fed with plant drink, n (%) |

29 (47.5) |

61 |

43 (13.1) |

327 |

3.6 (2.5;5.3) |

<0.001 |

| Type of plant drink, n (%) * |

|

61 |

|

327 |

|

|

| Soya |

6 (9.8) |

|

8 (2.4) |

|

4.0 (1.5;11.2) |

0.013 |

| Almond |

9 (14.8) |

|

13 (4.0) |

|

3.7 (1.7;8.3) |

0.003 |

| Oat |

24 (39.3) |

|

34 (10.4) |

|

3.8 (2.4;5.9) |

<0.001 |

| Rice |

0 (0.0) |

|

1 (0.3) |

|

- |

>0.999 |

| Coconut |

10 (16.4) |

|

0 (0.0) |

|

- |

<0.001 |

| Fed with fortified plant drink, n (%) |

12 (19.7) |

61 |

20 (6.1) |

327 |

3.2 (1.7;6.2) |

0.001 |

| Plant drink intake per day, ml, median (IQR) |

110.0 (87.5;206.3) |

28 |

100.0 (42.5;170.0) |

40 |

10.0 (0.0;100.0) |

0.197 |

| Complementary feeding practices |

| Number of meals per day, mean±SD |

4.4±1.0 |

61 |

4.6±1.1 |

327 |

-0.2 (-0.5;0.1) |

0.144 |

| Age of complementary foods introduction, n (%) |

|

61 |

|

326 |

|

|

| <17 weeks |

3 (4.9) |

|

27 (8.3) |

|

- |

0.666 |

| 17-26 weeks |

38 (62.3) |

|

196 (60.1) |

|

| >26 weeks |

20 (32.8) |

|

103 (31.6) |

|

| Introduction of potentially allergenic foods, n (%) |

|

61 |

|

327 |

|

|

| Aligned with other complementary foods |

41 (67.2) |

|

216 (66.1) |

|

- |

0.056 |

| Delayed compared to other complementary foods |

17 (27.9) |

|

108 (33.0) |

|

| Not introduced yet |

3 (4.9) |

|

3 (0.9) |

|

| Introduction of food allergens, n (%) |

|

61 |

|

327 |

|

|

| Milk |

45 (73.8) |

|

316 (96.6) |

|

0.8 (0.7;0.9) |

<0.001 |

| Eggs |

50 (82.0) |

|

323 (98.8) |

|

0.8 (0.7;0.9) |

<0.001 |

| Wheat |

57 (93.4) |

|

319 (97.6) |

|

0.96 (0.9;1.0) |

0.103 |

| Fish |

58 (95.1) |

|

318 (97.2) |

|

0.98 (0.9;1.0) |

0.412 |

| Soya |

34 (55.7) |

|

172 (52.6) |

|

1.1 (0.8;1.4) |

0.756 |

| Peanuts |

31 (50.8) |

|

229 (70.0) |

|

0.7 (0.6;0.9) |

0.005 |

| Nuts |

33 (54.1) |

|

228 (69.7) |

|

0.8 (0.6;1.0) |

0.025 |

| Sesame |

32 (52.5) |

|

224 (68.5) |

|

0.8 (0.6;1.0) |

0.023 |

3.7. Supplement Use

No significant differences were observed between the FA and non-FA groups in the use of dietary supplements, including vitamin D, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), probiotics, calcium, iron, multivitamin and mineral preparations, and others (Table S6).

3.8. Association Between Complementary Feeding and Diet Diversity in Children with Food Allergy

3.8.1. Any Breastfeeding and Diet Diversity Measures

In children with FA, a longer duration of any breastfeeding was associated with a higher median food allergen diversity score (p=0.014) (Table S7). Children breastfed for 1.5–5 months (median = 6.0), 6–12 months (median = 7.0), and more than 12 months (median = 6.5) demonstrated greater food allergen diversity compared with those breastfed for less than 1 month (median = 4.0) or approximately 6 months (median = 4.5). Post-hoc analysis confirmed significantly lower median food allergen diversity among children breastfed for less than 1 month compared with those breastfed for 6-12 months. No other significant associations between breastfeeding duration and diet diversity measures were observed in this group.

3.8.2. Exclusive Breastfeeding and Diet Diversity Measures

In the FA group, no significant associations between the duration of exclusive breastfeeding and any median or mean diet diversity measures, including specific food group diversity were identified (Table S8).

3.8.3. Other Complementary Feeding practices And Diet Diversity

In the FA group, no association were observed between the other complementary feeding practices, including: consumption of human milk substitutes (Table S9), and use of plant-based beverages (Table S10), and any mean or median diet diversity indicators. Additionally, in children with CMPA, no associations between prevalence of FA symptoms, and delayed (>26 weeks) introduction of complementary foods introduction (Table S11) and of potentially allergenic foods (Table S12). Moreover, no associations between the OFC-confirmed diagnosis and selected feeding practices were confirmed in CMPA and HEA subgroups (Table S4 and S5).

3.9. Associations Between Feeding Practices and Feeding Difficulties

In the FA group, no significant associations were found between the presence of feeding difficulties (MCH-FS score ≥ 46 points) or any dietary diversity indicators and the duration of any and exclusive breastfeeding (Table S7-10).

3.10. Reintroduction Using Food Ladder

3.10.1. Milk Ladder

The median age of baked milk reintroduction (12 months) and median time from CMPA diagnosis to milk reintroduction (6 months) were similar in children with OFC-confirmed CMPA and those without OFC (

Table S3). In the majority of children baked milk reintroduction was performed at home, with similar proportions in the two groups (92.3 vs 100%; n=47). Most children (81%; 38/47) started milk reintroduction using the milk ladder, and half of them achieved tolerance to baked and fried forms (cookies, muffins and pancakes; 51.1, 48.9 and 55.3 %, respectively). Tolerance to hard cheese was achieved by one third of children (29.8%), and 21.3% consumed fried/baked hard cheese without symptoms. A small proportion of children achieved tolerance to pasteurized milk or infant formula (23.4%) and/or raw fresh milk (10,6%).

3.10.2. Egg Ladder

More than half of children (63.3% [n=19/30]) started hen’s egg reintroduction using the egg ladder (Table S5). Although the difference between the OFC-confirmed and non-OFC HEA groups was not statistically significant, a slightly lower proportion of children in the OFC-confirmed group achieved tolerance to baked and fried forms of hen’s egg (cookies, muffins and pancakes; 43.3, 40.0 and 40.0%, respectively). No children in OFC-confirmed HEA group achieved tolerance to any cooked form of egg.

4. Discussion

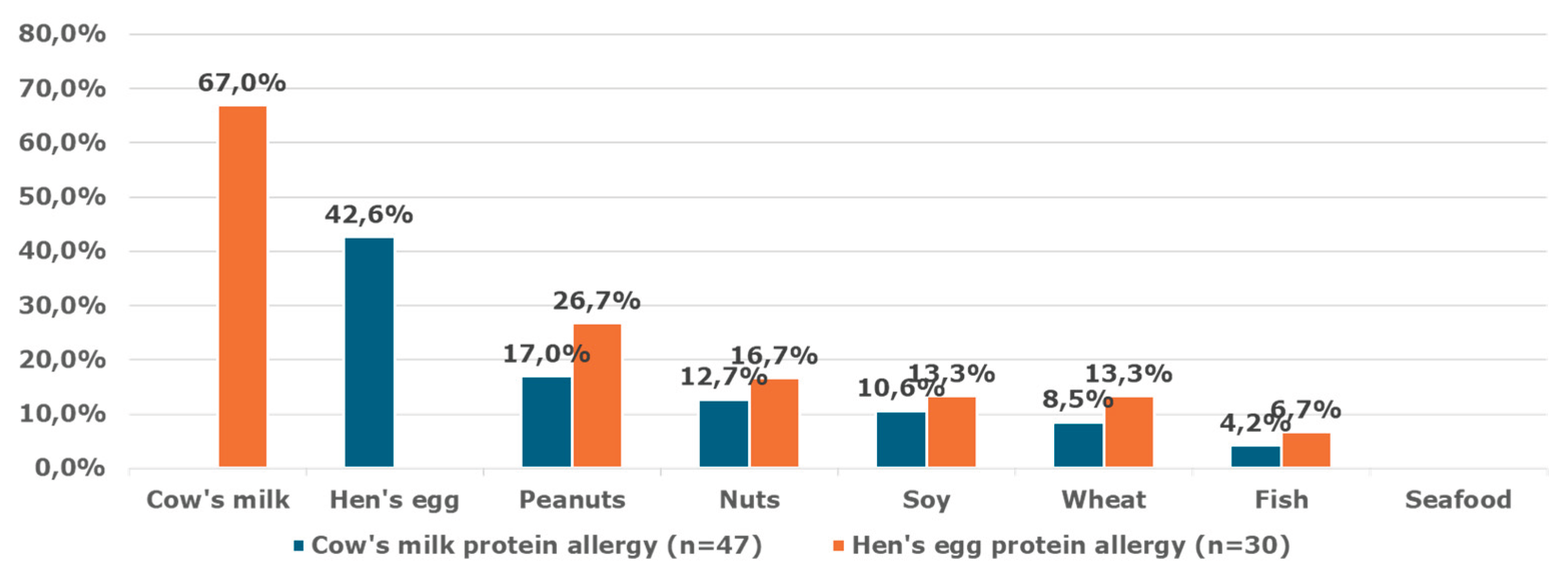

4.1. Summary of Main Results

This cross-sectional survey study conducted in Poland aimed to assess diet diversity and feeding practices in children aged 13–36 months on elimination diet due to FA who attend nurseries. A total of 388 participants were included, of whom, 61 had FA. Although the diagnosis of FA was confirmed by a physician in all cases; only one-third of children had undergone an OFC.

A summary of main findings is presented in Table 6. No differences between the FA and non-FA groups were observed in the proportion of children with underweight and stunting based on WHO growth indicators. However, approximately 20% had weight-for-age exceeding 85th percentile. Children with FA had lower overall diet diversity, food groups diversity (defined as ≥9 consumed food groups), food diversity, and mean food allergen diversity compared with the non-FA group, while no differences were identified in WHO minimum diet diversity, as well as, fruit and vegetable diversity. Although no differences in feeding difficulties were found between the FA and non-FA groups, their proportion was high in both groups (18 and 13.5%, respectively).

No differences in the duration of any and exclusive breastfeeding were observed between groups. Approximately one-fifth of children were still partially breastfed, with a higher number of night feeds observed in children with FA. One-third of all children were fed with human milk substitutes, with no significant difference in the proportion of formula-fed children found between the groups. The median intake of human milk substitute was high (~400 ml). One-third of children in the non-FA group consumed young child formula, while one-third of children in the FA group consumed extensively hydrolyzed or amino-acid formula.

Plant-based beverages were consumed nearly four times more frequently by children with FA (almost half of respondents) compared with those without FA, with oat-based drink being the most commonly chosen in both groups. While fewer than half of children received calcium-fortified plant-based beverages, their use was reported three times more often in the FA group compared with the non-FA group.

One-third of parents reported delayed introduction of solid foods (>26 weeks of infant’s age) and potentially allergenic foods in both groups. Importantly, a lower proportion of children in the FA group had introduced cow’s milk, hen’s egg, tree nuts, peanuts and sesame. Although, the lack of cow’s milk and hen’s egg introduction can, at least partially, be explained by the coexistence of CMPA and/or HEA, or tree nuts, peanuts and sesame, food allergy was reported only in a minority of children.

About half of children with CMPA and 40% children with HEA achieved tolerance to baked forms of the respective food allergens.

Table 6.

Summary of main findings.

Table 6.

Summary of main findings.

4.2. Comparison to Other Studies, Systematic Reviews and Guidelines

4.2.1. Diet Diversity in Children with FA

In children older than 12 months, the diet should be aligned with healthy family meals and include a variety of nutrient-dense, fresh, minimally processed, home-cooked and predominantly plant-based foods [

5,

25]. A more diverse diet may be associated with higher intake of immunomodulatory, nutrient-rich foods, increased gut microbial diversity and broader exposure to dietary antigens, which may contribute to the prevention of atopic and allergic diseases [

1]. Although, the lower diet diversity observed in our study may partly reflect necessary elimination of confirmed allergens, we also identified parental over-restriction of other allergens (e.g., tree nuts, peanuts, sesame) without confirmed FA.

Current guidelines from major pediatric and allergic societies recommend against delaying the introduction of food allergens. It is suggested that peanuts in age-appropriate forms and well-cooked egg should be introduced at the start of complementary feeding, any time from 4 months of age, as a strategy to reduce the risk of developing allergy later in life [

26,

27]. A 2023 umbrella systematic review summarizing evidence from 32 systematic reviews found moderate-quality evidence supporting the introduction of peanut and egg between 4 and 11 months of age to prevent food allergy [

28]. A recent UK population-based birth cohort study reported that, although most potentially allergenic foods were introduced between 6 and 9 months of age, the introduction of egg and nuts were delayed in a substantial proportion of children beyond 12 months of age (35% and 16%, respectively; n=139) [

29]. Furthermore, infants with a family history of allergy were more likely to avoid certain foods in their diet due to parental concerns about allergy.

Most parents reported atopic dermatitis and other skin manifestations as the primary symptoms of their child’s food allergy. In a South Korean study conducted in children with atopic dermatitis aged 1 month to 18 years, dietary restriction without medical evaluation, based solely on parental judgement was introduced in 39.7% of children (n=191) [

30]. A recent systematic review of 10 randomized controlled trials (n=599) showed that dietary restriction in children with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis resulted in only slight, clinically non-significant improvements in eczema severity, pruritus and sleeplessness [

31]. These findings emphasize the need of appropriate nutritional education and timely referral to dietitian trained in food allergy management, to ensure adequate elimination of relevant allergens while avoiding unnecessary dietary -restrictions [

9,

10]. Nevertheless, our study also revealed that most parents had not consulted a dietitian regarding their child’s FA, which may reflect both limited awareness and limited access to dietetic services in Poland.

4.2.2. Human Milk Substitutes Over One Year of Life

A high intake of infant and hypoallergenic formula observed in this population may contribute to reduced diet diversity. In our study, one-third of children continued formula feeding beyond 12 months of age. The European Society of Paediatric Gastroentereology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) does not recommend the routine use of young child formula in children aged 1-3 years, but acknowledges its potential role in specific populations as a part of a strategy to increase intake of iron, vitamin D and polyunsaturated fatty acids [

32]. Similarly, the 2025 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on maternal and child nutrition state that infant formula is not required beyond 1 year of age [

25].

The continuation of hypoallergenic formula consumption in children with FA aged 13 months and older remains a matter of debate. According to the recent EAACI guidance on complementary feeding, in children with FA or growth faltering, continuation of infant or hypoallergenic formula may be considered [

5]. Similarly, the British Society for Allergy & Clinical Immunology (BSACI) guidelines recommend that in children under 2 years of age with CMPA who are not breastfed, a suitable substitute milk should be used, in older children this is no longer necessary, whenever child has adequate intake of energy, protein, calcium and vitamins [

33].

4.2.3. Plant-Based Beverages over 1 Year of Life

In our study, some children replaced human milk substitutes with plant-based beverages. Plant-based beverages have been widely criticized as nutritionally inadequate for supporting growth in young children and are generally not recommended in children under 3 years of age with CMPA [

34]. Nevertheless, parental interest in using plant-based beverages instead of commercial formula is growing. Therefore, experts suggest that fortified plant-based beverages may be considered and successfully introduced in a carefully selected group of children over 1 year of age who meet specific nutritional criteria i.e., a well-balanced and diverse diet, absence of feeding difficulties and micronutrient deficiencies, consumption of at least two-third of their daily energy from solid foods and intake of no more than 500 ml of milk substitute per day [

35]. In clinical practice, it should be emphasized to parents that only calcium-fortified plant-based beverages are appropriate, as our study found that fewer than half of children received fortified products [

35,

36].

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess diet diversity in children aged 13-36 months with physician-confirmed food allergy compared to healthy children recruited from the general population (nurseries). Therefore, these findings may be applicable not only to children with severe allergic symptoms typically referred to academic hospitals, but also to the broader population of children with mild and moderate allergic symptoms.

A significant proportion of parents reported that their children had not undergone OFC to confirm the diagnosis of FA. Although OFC may be omitted in cases with very high specific IgE levels, large skin prick test wheals, or a clear history of anaphylaxis [

6], we cannot exclude the possibility that some cases in our study were misdiagnosed. However, these findings reflect the real-world situation in Poland, where a high proportion of FA diagnoses are not confirmed by OFC (as previously discussed in the

Methods) [

17]. To minimize this potential bias, we analysed and reported outcomes separately for children with OFC-confirmed and non-OFC confirmed FA; however, no significant differences was observed between these subgroups.

The relatively large study sample and the use of standardized, validated tools for identifying feeding difficulties (MCH-FS) and assessing dietary diversity (FFQ-6) are important strength of this study. However, we used convenience sampling, which likely attracted parents more interested in infant feeding or those perceiving feeding issues in their children. In addition, the survey included only children from two large Polish cities (Warsaw and Olsztyn) with parents reporting good socio-economic status. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to children from smaller towns, rural areas, or families with lower socio-economic status. Due to cross-sectional nature our study may also be subject of non-response bias, as participants who agreed to contribute may differ systematically from those who declined. Furthermore, the parental self-reported data, particularly retrospective information such as breastfeeding duration, or age of complementary food introduction, may be affected by recall bias.

Finally, as with any cross-sectional study, the nature of this study precludes any causal interferences. Nevertheless, we found strong correlations between physician-declared FA and several feeding practices, including: higher consumption of plant-based beverages, delayed introduction of potentially allergenic foods and lower diet diversity.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that children aged 13-36 months following elimination diet due to FA are at risk of reduced diet diversity and food allergens diversity. Additionally, our findings clarified major feeding issues in children with FA, including delayed introduction of potentially allergenic foods, over-restriction of potentially allergenic foods, replacing human milk substitutes with plant-based beverages and high number of night breastfeeds. Individualized nutritional counseling for children with FA should be promoted to support appropriate allergen introduction, ensure adequate diet variety and prevent over-restriction. Further research in populations with lower socio-economic status, as well as more in-depth studies assessing potential factors influencing diet diversity are needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary File 1. Supplementary Tables S1-S12.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. A.H. and B.J-C.; methodology A.S. and A.H.; formal analysis, A.S., A.H. and J.P.; investigation, A.S., A.H. and D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., A.H. and D.W.; writing—review and editing, E.J-C. and J.P.; supervision, A.H.; funding acquisition, A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Medical University of Warsaw and education grant by the Nutricia Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Medical University of Warsaw (AKBE/281/2024 and date of approval: 18 Nov 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants agreed voluntarily to participate in the study and were informed that the data would be analyzed anonymously.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and/or generated during this study is available from a given author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all participants who made this study possible. Special thanks are extended to the nursery staff for their crucial assistance in disseminating the survey and encouraging parents to participate.

Conflicts of Interest

A.S. has participated as a speaker for Nestlé, Mead Johnson and receives research support from Nutricia. A.H. has participated as a clinical investigator, advisory board member, and speaker for several companies, including BioGaia, Danone, Dicofarm, HIPP, Nestlé, NNI, Nutricia, and Mead Johnson. E.J-C. has participated as a speaker for companies manufacturing infant formulas, i.e., Nutricia and Mead Johnson. D.W. and J.P. declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAF |

Amino acid formula |

| BSACI |

British Society for Allergy & Clinical Immunology |

| CI |

Confidence intervals |

| CMPA |

Cow’s milk proteins allergy |

| DHA |

Docosahexaenoic acid |

| EAACI |

European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology |

| ESPGHAN |

European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition |

| EHF |

Extensive hydrolyzed formula |

| FA |

Food allergy |

| FFQ |

Food Frequency Questionnaire |

| HF |

Hypoallergenic formula |

| HEA |

Hen’s egg protein allergy |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| MD |

Mean or median difference |

| MCH-FS |

Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale |

| NICE |

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| Non-FA |

No food allergy |

| OFC |

Oral food challenge |

| RR |

Relative risk |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Venter C, Greenhawt M, Meyer RW, Agostoni C, Reese I, du Toit G, et al. EAACI position paper on diet diversity in pregnancy, infancy and childhood: Novel concepts and implications for studies in allergy and asthma. Allergy. 2020;75(3):497-523.

- Venter C, Maslin K, Holloway JW, Silveira LJ, Fleischer DM, Dean T, et al. Different Measures of Diet Diversity During Infancy and the Association with Childhood Food Allergy in a UK Birth Cohort Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(6):2017-26.

- Venter C, Groetch M. Emerging concepts in introducing foods for food allergy prevention. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2025;28(3):263-73.

- Lee BR, Jung HI, Kim SK, Kwon M, Kim H, Jung M, et al. Dietary Diversity during Early Infancy Increases Microbial Diversity and Prevents Egg Allergy in High-Risk Infants. Immune Netw. 2022;22(2):e17.

- Vlieg-Boerstra B, Netting M, Vassilopoulou E, Reese I, Jensen-Jarolim E, Marchand S, et al. Guidance for healthy complementary feeding practices for allergy prevention in developed countries: An EAACI interest group report. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2025;36(7):e70150.

- Vandenplas Y, Broekaert I, Domellöf M, Indrio F, Lapillonne A, Pienar C, et al. An ESPGHAN Position Paper on the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Cow’s Milk Allergy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;78(2):386-413.

- Santos AF, Riggioni C, Agache I, Akdis CA, Akdis M, Alvarez-Perea A, et al. EAACI guidelines on the management of IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy. 2025;80(1):14-36.

- Meyer R, Venter C, Bognanni A, Szajewska H, Shamir R, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, et al. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) Guideline update - VII - Milk elimination and reintroduction in the diagnostic process of cow’s milk allergy. World Allergy Organ J. 2023;16(7):100785.

- Venter C, Meyer R, Bauer M, Bird JA, Fleischer DM, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, et al. Identifying Children at Risk of Growth and Nutrient Deficiencies in the Food Allergy Clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12(3):579-89.

- Durban R, Groetch M, Meyer R, Coleman Collins S, Elverson W, Friebert A, et al. Dietary Management of Food Allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2021;41(2):233-70.

- Papachristou E, Voutsina M, Vagianou K, Papadopoulos N, Xepapadaki P, Yannakoulia M. Dietary Intake, Diet Diversity, and Weight Status of Children With Food Allergy. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2024;124(12):1606-13.e5.

- Maslin K, Dean T, Arshad SH, Venter C. Dietary variety and food group consumption in children consuming a cows’ milk exclusion diet. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2016;27(5):471-7.

- Cole NC, An R, Lee SY, Donovan SM. Correlates of picky eating and food neophobia in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2017;75(7):516-32.

- Fewtrell M, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Domellöf M, Embleton N, Fidler Mis N, et al. Complementary Feeding. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2017;64(1):119-32.

- Venter, C. Immunonutrition: Diet Diversity, Gut Microbiome and Prevention of Allergic Diseases. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2023;15(5):545-61.

- Weker H, Barańska M, Riahi A, Strucińska M, Więch M, Rowicka G, et al. Nutrition of infants and young children in Poland - Pitnuts 2016. Dev Period Med. 2017;21(1):13-28.

- Stróżyk A, Horvath A, Jarocka-Cyrta E, Bogusławski S, Szajewska H. Discrepancy between Guidelines and Clinical Practice in the Management of Cow’s Milk Allergy in Children: An Online Cross-Sectional Survey of Polish Physicians. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2022;183(9):931-8.

- McHenry M, Watson W. Impact of primary food allergies on the introduction of other foods amongst Canadian children and their siblings. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology. 2014;10(1):26.

- Lovell A, Bulloch R, Wall CR, Grant CC. Quality of food-frequency questionnaire validation studies in the dietary assessment of children aged 12 to 36 months: a systematic literature review. J Nutr Sci. 2017;6:e16.

- Bąbik K, Dziechciarz P, Horvath A, Ostaszewski P. The Polish version of the Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale (MCH-FS): translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation. Pediatria Polska - Polish Journal of Paediatrics. 2019;94(5):299-305.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Child growth standards.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Infant and young child feeding. Available at https://www.who.int/data/nutrition/nlis/info/infant-and-young-child-feeding (accessed: 06 Aug 2025).

- Roduit C, Frei R, Depner M, Schaub B, Loss G, Genuneit J, et al. Increased food diversity in the first year of life is inversely associated with allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(4):1056-64.

- Kuśmierek M, Chęsy A, Krogulska A. Diet Diversity During Infancy and the Prevalence of Sensitization and Allergy in Children up to 3 Years of Age in the Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodeship, Poland. Clinical Pediatrics. 2024;63(3):375-87.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Maternal and child nutrition: nutrition and weight management in pregnancy, and nutrition in children up to 5 years. Opublikowany: 15.01.2025 r.

- Halken S, Muraro A, de Silva D, Khaleva E, Angier E, Arasi S, et al. EAACI guideline: Preventing the development of food allergy in infants and young children (2020 update). Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32(5):843-58.

- World Health Organization (WHO) guideline on the complementary feeding of infants and young children aged 6-23 months 2023: A multisociety response. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;79(1):181-8.

- Soriano VX, Ciciulla D, Gell G, Wang Y, Peters RL, McWilliam V, et al. Complementary and Allergenic Food Introduction in Infants: An Umbrella Review. Pediatrics. 2023;151(2).

- Helps S, Mancz G, Dean T. Introduction time of highly allergenic foods to the infant diet in a UK cohort and association with a family history of allergy. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2025.

- Youm S, Lee E, Lee J. Environmental and dietary factors to be checked for treatment of atopic dermatitis in rural children. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021;64(12):661-3.

- Oykhman P, Dookie J, Al-Rammahy H, de Benedetto A, Asiniwasis RN, LeBovidge J, et al. Dietary Elimination for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(10):2657-66.e8.

- Hojsak I, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Domellöf M, Embleton N, Fidler Mis N, et al. Young Child Formula: A Position Paper by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(1):177-85.

- Luyt D, Ball H, Makwana N, Green MR, Bravin K, Nasser SM, et al. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk allergy. Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 2014;44(5):642-72.

- Merritt RJ, Fleet SE, Fifi A, Jump C, Schwartz S, Sentongo T, et al. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Position Paper. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2020;71(2):276-81.

- Venter C, Roth-Walter F, Vassilopoulos E, Hicks A. Dietary management of IgE and non-IgE-mediated food allergies in pediatric patients. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2024;35(3):e14100.

- Rachtan-Janicka J, Gajewska D, Szajewska H, Włodarek D, Weker H, Wolnicka K, et al. The Role of Plant-Based Beverages in Nutrition: An Expert Opinion. Nutrients. 2025;17(9).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).