1. Introduction

The aim of this study is to examine the social,

economic and cultural implications of Latin American women's forced

displacement by the climate crisis, configured in spaces of conflict and

negotiation. The intersection of gender, migration and climate change reveals

systematic patterns of differentiated vulnerability (Das, 2024), in which

women, particularly in the Latin American context, experience the impacts of

the global climate crisis (Mijangos, 2023). Against this background, the

research question arises: What are the social, economic and cultural factors

that influence the vulnerability and adaptive capacity of Latin American women

in the face of forced displacement, and what strategies have they developed to

cope?

Forced displacement due to climate change has

become one of the most pressing issues of the 21st century. However, the

analysis of climate migration has tended to focus on the vulnerability of the

displaced, without considering the spaces of conflict and negotiation that

emerge in these processes. From the perspective of 'Arenas of Conflict and

Collective Experiences. Utopian horizons and domination' (Tarrés et al., 2014),

it is possible to reframe this discussion by including the concept of arenas of

conflict, in which affected communities are not just victims, but active

subjects who negotiate, resist and build new forms of organisation.

This reality manifests itself in a scenario where

climate change acts as a multiplier of pre-existing threats, exacerbating

structural inequalities and gender-based power imbalances (United Nations,

2019; Setyorini et al., 2024). The intensification of extreme weather events

(Wen et al. 2023), characterised by droughts, floods and increasingly intense

meteorological phenomena, is reshaping patterns of habitability in many regions

of Latin America, forcing displacement and affecting vulnerable communities (Almulhim

et al., 2024). In this context, climate-related disasters not only represent

immediate humanitarian crises, but also act as catalysts for social

transformations in which women often negotiate, resist and build new forms of

organisation (Ripple et al. 2024).

A gender perspective in the analysis of

climate-induced forced displacement reveals how patriarchal structures

condition women's vulnerability and responsiveness to these crises (Carter,

2015), limiting their access to resources, information and protection (Du,

2024). The emergence of female climate refugees complicates forced migration

(Batista et al., 2024), challenges international legal frameworks and exposes

critical gaps in existing protection systems (Mijangos, 2023). According to

Tarrés et al. (2014), these dynamics are part of disputes over territory and

resources, where restrictive migration policies and border securitisation

function as control mechanisms. Thus, climate refugees not only seek to

survive, but also to contest their existence within established legal

frameworks (Global Report on Internal Displacement, 2024). The geopolitical

implications are manifold: from the reformulation of migration policies to the

emergence of new power dynamics between sending and receiving states (Global Report

on Internal Displacement, 2024). In Latin America, the intersection of

socio-economic inequality, ethnic discrimination and institutional weakness

intensifies the conditions of vulnerability for displaced women (Mai, 2024).

These impacts go beyond material losses, affecting family structures, community

networks and livelihoods (Global Report on Internal Displacement, 2024). As

Solorio (2024) argues, there is an urgent need to look beyond traditional

approaches and consider the gender and power dynamics that shape the experience

of displacement. In this context, new patterns of vulnerability are emerging,

influenced by both climate change and historical gender inequalities, requiring

innovative, culturally sensitive and gender-responsive policy responses (Rojas-Rendon

& Valle, 2024). This issue is embedded in a historical continuum: from

early societies (Wood, 1996; Dean et al., 2001), through evolutionary processes

(Macintosh, Pinhasi & Stock, 2017), to contemporary scenarios of gender

inequality in relation to the environment (Loots & Haysom, 2023; Thakur,

2023; Dev & Manolo, 2023). Using an integrative theoretical-conceptual

framework that articulates gender analysis, climate change studies and

evolutionary perspectives, and a qualitative methodology based on a literature

review and case study, the analysis shows how social norms, historically biased

in favour of men, deepen women's vulnerability to climate change. However, it

also identifies opportunities for empowerment and social transformation in

women's adaptation and resilience processes.

2. Critical Intersectional Theorising

The confluence of analytical perspectives in this

theoretical-conceptual framework establishes a multidimensional prism for

examining gendered displacement in the Latin American context. The integration

of ecofeminist theory, as proposed by Doley (2025), allows us to deconstruct

how patriarchal structures reinforce women's differential vulnerability to

climate shocks, transforming adaptation and resilience into powerful mechanisms

of women's empowerment. This approach reveals the complex interactions between

systems of gender oppression and the asymmetrical impacts of climate change,

positioning women not only as disproportionate victims of these phenomena, but

also as key agents of social and environmental transformation in contexts of

forced mobility. The inclusion of the geopolitical dimension articulated by

Topalidis et al. (2024) enriches the analysis by contextualising the emerging

category of women climate refugees within the regional and global power

dynamics that characterise Latin America. This perspective highlights the

strategies of collective resistance employed by displaced women, who, far from

representing victimised passivity, constitute nuclei of social innovation that

challenge entrenched structural inequalities in the region. The interweaving of

environmental, socio-economic and political factors reveals how women develop

survival mechanisms that go beyond mere adaptation to become transformative

practices that challenge extractivist models and hegemonic power relations.

On the contemporary horizon of development and

human mobility studies, this integrative framework facilitates the

identification of predictive patterns that anticipate gendered climate

displacement. The symbiosis between host communities and displaced women

emerges as a potential catalyst for socio-economic innovation, where the

experiences and knowledge of women climate refugees enrich the host social

fabric. Data analysis and computational modelling technologies, applied with a

gender approach, allow the visualisation of intervention scenarios that enhance

the social, cultural and economic capital of displaced women, while

contributing to the consolidation of more equitable and resilient societies.

This holistic approach reconfigures public policies towards an integrated

continuum that reconciles humanitarian, environmental and development

dimensions, overcoming the historical fragmentation that has hindered effective

gender-sensitive responses to forced displacement in Latin America.

2.1. Climatic History of Women

In the context of the climate crisis, the woman

emerges as a symbol of transformation, embodying both vulnerability and

strength in the face of contemporary environmental challenges. Not only does

she represent a group particularly affected by ecological crises, but she also

stands as a key architect of sustainable solutions, weaving a web where

ancestral knowledge intertwines with modern innovation. This figure embodies

female resilience, adaptability and leadership in multiple spheres, from

community-based natural resource management to the highest levels of

international climate policy (Turquet et al. 2023). Located at the intersection

of the struggle for gender equality and environmental action, this embodiment

serves as an essential catalyst for a just and sustainable future, challenging

and forging new pathways to global resilience.

The relationship between women and climate is

deeply rooted in human evolution, as evidenced by palaeontological findings

such as Lucy (Gibbons, 2024) and studies of species such as Australopithecus

and Homo (Robson & Wood, 2008; Stringer, 2016). From the earliest times,

women have played a key role in adapting to climatic variability through

subsistence strategies and biocultural care (Wood, 1996; Dean et al., 2001;

Davis & Shaw, 2001; Bogin, 2014; Martin, 2007). Technological innovation -

such as the use of fire - and knowledge of the environment reinforced this role

in human expansion (Carmody & Wrangham, 2009; Hublin et al., 2015; de

Lafontaine, 2018). In the Upper Palaeolithic, their mastery of plants and

natural resources was essential to survive the last ice age (Stibel, 2023), and

in the Neolithic they consolidated their central role in agricultural

production and the sustainability of early societies (Betti et al., 2020;

Bolger, 2010). These contributions are reflected in mythologies such as Demeter

(Difabio, 2021), Pachamama (Sayre & Rosenfeld, 2021) and the Totonac

deities (Lugo-Morin, 2020), which symbolise the link between the feminine and

ecological management (Strassmann & Gillespie, 2002). Even after their

exclusion from formal power structures, women maintained ecological knowledge

in local spaces, which became arenas of conflict and negotiation (Johri, 2023;

Hunt & Rabett, 2014). The Caral civilisation and settlements such as Áspero

demonstrate how women led processes of resilience and social cohesion in the

face of climatic migrations over 5000 years ago (Shady, 2006a; 2006b). In the

context of the Anthropocene (Malhi, 2017), this historical role needs to be

reassessed. Gender inequalities increase their vulnerability, especially in

developing countries (Jost et al., 2015), but also position them as key actors

in the fight for climate justice (Loots & Haysom, 2023; Thakur, 2023; Singh

et al., 2021). The integration of traditional and scientific knowledge is a

strategic resource for adaptation (Huyer et al., 2020). This double condition

-vulnerability and leadership- is claimed by currents such as ecofeminism,

which denounces the relationship between patriarchal oppression and

environmental exploitation (Doley, 2025). In the midst of the climate crisis

(Dev & Manolo, 2023), women are emerging as community leaders (Smith, 2022;

Mayka & Smith, 2021), driving transformative action (Turquet et al., 2023)

and proposing inclusive solutions that benefit historically marginalised

sectors. Their role in areas such as climate finance demonstrates multiplier

effects in agriculture, energy and the regenerative economy (Lugo-Morin, 2025),

although their low involvement in high-level decision-making persists. The gap

between commitments and implementation was evident at COP15, where only 83.3 of

the 100 billion pledged was mobilised (Qi & Qian, 2023). In other areas,

urban planning has been key to designing gender-responsive solutions, such as

inclusive transport systems and resilient green spaces (Kerry & Sayeed,

2024; Zavala et al., 2024). For a low-carbon future (Lugo-Morin, 2025), it is

essential to ensure a just transition that fully engages women as agents of

change. This means creating equitable opportunities in the green economy,

redressing inequalities in transition sectors, and preventing climate policies

from deepening existing inequalities (Pinho-Gomes & Woodward, 2024). In

this way, the historical trajectory of the link between women and climate -from

the dawn of humanity to the present day- is consolidated as a fundamental axis

for survival and sustainability on an increasingly unpredictable planet.

2.2. Spaces of Conflict and Negotiation in the Context of Climate Change

Throughout history, climate change has accompanied

human evolution, manifesting itself in natural cycles of warming and cooling

driven by factors such as Earth's orbit, solar activity, volcanic eruptions or

ocean currents (Zalasiewicz & Williams, 2021; Lin & Qian, 2022). In

this evolutionary process, early humans - particularly women - developed

adaptive strategies to ensure collective survival (Macintosh, Pinhasi &

Stock, 2017). Their role in household resource management (Davis & Shaw,

2001; Khanom et al., 2022), agriculture, food security and transmission of

traditional ecological knowledge made them pillars of community resilience. In

addition, women were key to building support networks and local innovations to

cope with climate variability (Okesanya et al., 2024). However, these

contributions have historically coexisted with structural and cultural barriers

that have limited their participation in environmental decision-making.

Research in regions such as the Himalayas and Colombia highlights these limitations

and argues for equitable inclusion in adaptation processes (Barrios et al.,

2025; Das, 2024).

The current climate crisis, which has accelerated

since the industrial revolution, is unprecedented in scale and speed.

Greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation and

uncontrolled urbanisation have led to profound changes in global ecosystems

(Barcellos, 2024). This situation is exacerbated by unsustainable consumption

patterns and cascading effects, such as the melting of permafrost and the

intensification of extreme events (Hugelius et al., 2024). In this context,

women are emerging as key actors in formulating resilient responses. Their

ability to lead sustainable practices and strengthen community cohesion is

widely recognised (Ripple et al., 2024). Women's empowerment in climate change

contexts not only contributes to greater equity, but also enhances the

effectiveness of adaptation strategies, particularly in terms of resource

management, food sovereignty and building territorial resilience. However,

climate change not only exacerbates existing vulnerabilities, but also gives

rise to new conflict and negotiation scenarios. Forced migration caused by

environmental disasters and livelihood degradation creates spaces of tension

where state, corporate and community interests converge (Tarrés et al., 2014).

In these spaces of conflict and negotiation, migrant women face particular

challenges: they struggle for access to basic resources, the defence of their

rights and political recognition in contexts marked by exclusion and structural

inequality (Das, 2024; Mijangos, 2023). Their migratory experience, far from

being a simple physical displacement, becomes an expression of resistance to

systems that have historically marginalised them. Understanding these spaces as

scenarios where power relations are reconfigured allows us to make visible

women's agency in processes of adaptation, resistance and social

transformation. Climate migration should therefore be analysed not only from an

environmental perspective, but also from a gender perspective that recognises

and empowers women's agency in the struggle for climate and social justice.

Rising sea levels (Vousdoukas et al., 2023),

salinisation of aquifers (Abd-Elaty et al., 2024), coastal erosion (Pang et al.

2023) and loss of biodiversity (Boakes et al., 2024) are exacerbating pressures

on vulnerable populations, leading to forced migration and geopolitical

tensions (Almulhim et al., 2024). Such displacements, driven by extreme

environmental phenomena, not only expose the structural weaknesses of many

regions - as illustrated by Hurricane Otis in Mexico (Gervacio et al., 2024) -

but also create spaces of conflict and negotiation shaped by pre-existing

inequalities (Tarrés et al., 2014). Women, in particular, face particular

challenges and multiple forms of exclusion in climate-induced migration. Far

from being mere victims, many emerge as agents of transformation. In contexts

of forced displacement, they forge networks of solidarity and resistance that

challenge patriarchal structures and promote new forms of autonomy and

collective organisation (Setyorini et al., 2024). This phenomenon has led to a

shift in climate risk management strategies. In recent decades, the focus has

shifted from disaster management to a resilience and sustainable development

paradigm (Wen et al., 2023). This shift has revalued local action and community

leadership, highlighting the role of women as catalysts for change (Ripple et

al., 2024).

Initiatives such as climate laboratories have

emerged as platforms for social and technological innovation at the community

level. These spaces enable the co-creation of solutions tailored to specific

contexts, promoting territorial resilience, social cohesion and energy

sovereignty. Similarly, climate education that integrates scientific knowledge

with traditional wisdom, alongside technical training for green jobs, has

become a cornerstone strategy for empowering women and increasing their

participation in decision-making (Nusche et al., 2024). The international

response to this crisis finds a critical tool in the climate finance ecosystem.

The Green Climate Fund (GCF), established at COP16 and formalised at COP17

(Green Climate Fund, 2024), aims to finance adaptation and mitigation efforts

in developing countries. Despite unfulfilled commitments such as the $100

billion target for 2020 (Qi & Qian, 2023), the GCF has redefined its

priorities for 2024-2027, focusing on strengthening vulnerable countries, mobilising

the private sector and protecting vulnerable populations. Latin America has

received 24% of the GCF's global portfolio, but faces persistent challenges:

limited regional participation, limited technical capacity, reliance on

intermediaries, and a lack of projects targeting climate-displaced people

(Green Climate Fund, 2024). This gap is worrying given UNHCR's warnings about

the increasing risks faced by those fleeing extreme environmental conditions

(UNHCR, 2024). The recent COP29 in Baku marked a milestone by tripling funding

to $300 billion annually by 2035. This shift in the international financial

architecture provides an unprecedented opportunity to explicitly include

climate migrant women as strategic actors in resource allocation, policy design

and implementation of resilient solutions (Tamasiga et al., 2024). Climate

disasters are not only a growing global threat, but also an emerging arena for

socio-political contestation and negotiation, where displaced women are

redefining their roles, leading community resilience efforts and asserting

their right to live in a just, inclusive and sustainable future.

2.3. Climate-Induced Displacement: Gender, Refugeehood, and the Politics of Geopower

Forced displacement, defined as the involuntary

departure of people from their homes due to external threats to their safety

and livelihoods (Hirsh et al., 2020; Stilz, 2025), is one of the most pressing

phenomena of the current climate crisis. Over the past decade, climate change

has been a central driver of this process: between 2008 and 2018, 265 million

people were displaced by disasters, 85% of which were linked to climate-related

causes (Mustak, 2022). By the end of 2023, almost three-quarters of displaced

people were living in countries highly exposed to climate hazards (Alliance of

Bioversity International and International Centre for Tropical Agriculture,

2024), highlighting a clear link between environmental vulnerability and human

mobility.

The impacts of climate change in Latin America are

severe, with vulnerabilities including droughts, glacial retreat - resulting in

30-50% losses over four decades (WMO, 2022) - heat waves and food insecurity

(Almulhim et al., 2024). These phenomena are exacerbating water scarcity and

causing mass displacement, particularly in countries such as Mexico, Ecuador,

Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua (Murray-Tortarolo & Salgado,

2021). Projections suggest that between 5.8 and 10.6 million people will be

internally displaced by 2050 (Almulhim et al., 2024). These processes are

reshaping territories and giving rise to scenarios in which structural

conflicts converge with new social negotiations. In this context, women face a

double condition: increased risks of violence, exploitation and exclusion from

access to resources (United Nations, 2019), while playing an active role in

rebuilding communities (Alliance of Bioversity International and International

Centre for Tropical Agriculture, 2024). Drawing on the concept of 'arenas of

conflict and collective experience' (Tarrés et al., 2014), forced displacement

emerges as a space where women negotiate belonging, leadership and new forms of

organisation. Understanding climate migration from this perspective is crucial

for designing gender-sensitive policies (Ripple et al., 2024).

Climate change acts as a catalyst for crises that

go beyond physical displacement, affecting cultural identities, social cohesion

and mental health (Allen et al., 2024). Host communities face logistical

challenges that can perpetuate exclusion if not addressed equitably (Heslin et

al., 2019). Therefore, cross-sectoral responses that integrate climate justice,

gender equality and community resilience are essential (Khan, 2024). Promoting

equality in decision-making is not only an ethical principle, but also an

effective strategy (Asian Disaster Preparedness Center, 2021). General

Recommendation No. 40 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination

against Women sets a new benchmark of 50% female participation in

decision-making (United Nations, 2024), surpassing the previous threshold of

30%. This shift requires overcoming institutional resistance and

pseudo-feminist rhetoric (Jagernath & Nupen, 2022) through economic

empowerment, gender education and disaggregated data (UN Women, 2024). This approach

not only addresses the consequences of displacement, but also promotes

structural changes towards equity (Castillo & Zickgraf, 2024). In Latin

America, where economic inequality, structural violence and institutional

fragility persist (Mijangos, 2023), the leadership of civil society and women's

movements is paving the way for culturally relevant responses (Global Report on

Internal Displacement, 2024). The active participation of indigenous and

Afro-descendant women, alongside transnational cooperation through CELAC,

MERCOSUR and the Pacific Alliance, is crucial to addressing the issue

regionally (Koomson & Koomson, 2024). Cases such as Ecuador, which

constitutionally recognises the right to protection from climate change, mark

significant progress (Toaquiza, 2024). Climate justice and women's economic and

educational autonomy are pillars of a just climate migration framework (Reeves

et al., 2023; Rojas-Rendon & Valle, 2024).

Climate refugees face triple vulnerability: gender,

displacement and lack of legal recognition (Mijangos, 2023). Nevertheless,

their agency shines through in cooperatives, transnational networks, and

alliances with social movements (Andersen et al., 2017), challenging

extractivist models and opening up new pathways for adaptation (Methmann &

Oels, 2015). From a critical perspective (Tarrés et al., 2014), the territories

they inhabit become arenas of contestation over water, land or housing, shaped

by restrictive migration policies and the securitisation of borders (Allin,

2024; Global Report on Internal Displacement, 2024). This geopolitical

dimension is global. From Bangladesh (Ahmed & Eklund, 2021) to Africa, Asia

and Latin America (Rao et al., 2017; Global Report on Internal Displacement,

2024), millions of women are displaced by climate change. Their lack of legal

recognition is being met with new responses that combine microfinance,

ancestral knowledge, and women-led strategies (Gerhard et al., 2023). These

community-driven and technological solutions are redefining climate governance

through a gender lens (Bharwani et al., 2024), positioning women as leaders of

resilient adaptation.

In Latin America, climate displacement is reshaping

geopolitical tensions and opportunities. Critical regions such as the

Caribbean, the Amazon, the Andes and the Dry Corridor are forcing organisations

such as CELAC, MERCOSUR and the Pacific Alliance to rethink cross-border

cooperation mechanisms (Figueiredo et al., 2024; Solorio, 2024). This includes

proposals such as climate visas, early warning systems and adaptation funds

(Cisneros et al., 2024). A forward-looking approach envisions a comprehensive infrastructure

for climate refugees: digital identity, women-led cooperatives, adaptive legal

frameworks, green microfinance, and sustainable host cities (World Economic

Forum, 2023; Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship, 2024). These

solutions not only recognise the transformative role of women, but also demand

climate justice and reparations from high emitting countries. Latin America has

a historic opportunity to lead an innovative, intersectional and decolonial

response that places displaced women at the centre of global change.

3. Case Study: What Can Latin America Learn from the Asians?

A study of women displaced by riverbank erosion,

sea level rise and drought in Bangladesh reveals the complexities of migration

(Khanom et al., 2022). While urban migration can expose vulnerabilities linked

to inadequate infrastructure and entrenched patriarchy, women can resist these

issues by forming networks and cooperatives that function as spaces of

negotiation. Policies should involve women in adaptation processes (Tarrés et

al., 2014).

Case study analysis: A thematic analysis focusing

on the intersection between gendered vulnerability and adaptive strategies was

conducted based on the findings of Khanom et al. (2022), integrating recent

data. The qualitative methodology of the study, which involved collecting life

histories and conducting in-depth interviews (n = 52) and focus group

discussions (n = 6) in settlements such as Bhola and Cox's Bazar, revealed that

women face a range of vulnerabilities, from natural disasters to urban risks such

as gender-based violence and labour exploitation. For example, one interviewee,

aged 30, reported experiencing sexual assault in an informal employment

setting, emphasising how migration exacerbates insecurity (quote: 'I was

sexually assaulted there. I could not continue in that job'). Around 70% of

women reported cultural restrictions that limited their mobility, while 80%

developed informal strategies, such as making seashell handicrafts, to generate

income, but these strategies simultaneously perpetuate precarious livelihoods.

Integrating studies such as the Global Report on Internal Displacement (2024),

which documents a 1.3 million increase in cyclone-related displacements in

2023, alongside Ahmed and Eklund (2021), who report a significant number of

internally displaced women, reveals a vicious cycle. This cycle begins with

initial adaptation (migration) and leads to maladaptation (social exclusion).

This dynamic can be quantified through the Gender Vulnerability Index (GVI)

proposed by UN Women (2024):

GVI = (Climatic exposure + Patriarchal norms) /

(Social networks + Economic opportunities). Values greater than 1 indicate high

risk. Applying this to Khanom's data, we find that Bhola has a VGI of 1.5.

These calculations are derived from the work of Khanom et al. (2022), who

describe Bhola as a settlement characterised by severe exposure to riverbank

erosion, sea-level rise and drought — all of which contribute to heightened

climatic vulnerability. The Global Report on Internal Displacement (2024) further

highlights the severity of environmental stressors, noting an increase of 1.3

million people displaced by cyclones. Based on this evidence, Bhola may be

assigned a moderate score of 3 on a normalised scale of 1–5 (with 5

representing extreme exposure), reflecting the acute climatic risks it faces.

In terms of patriarchal norms, the study indicates that 70% of women face

cultural restrictions that limit their mobility. Cases of gender-based

violence, such as sexual assault in informal employment, highlight the

significant constraints imposed by patriarchy. For this dimension, we assign a

score of 3 on the 1–5 scale (where 5 represents the greatest patriarchal

influence). With regard to social networks, although women in Bhola develop

solidarity groups and cooperatives, these are described as being limited in

scope and often insufficient to counteract exclusion. Therefore, a moderate

score of 2 is assigned on a scale of 1–5 (where 5 indicates strong social

support), reflecting networks that are only partially effective. In terms of

economic opportunities, around 80% of women engage in informal activities such

as producing handicrafts. However, these activities perpetuate precarity and

provide only limited economic security. Accordingly, a moderate-to-low score of

2 is assigned on a scale of 1–5 (where 5 indicates abundant opportunities),

indicating scarce economic options.

The Gender Vulnerability Index (GVI) is expressed

as follows:

GVI = (climatic exposure + patriarchal norms) /

(social networks + economic opportunities). Applying the values discussed, we

get: GVI = (3 + 3)/(2 + 2) = 1.5.

These values (3, 3, 2, 2) are consistent with the

qualitative evidence. Bhola faces significant climatic risks and patriarchal

restrictions, and while women’s networks and informal economic activities

provide some mitigation, it is insufficient to reduce vulnerability below the

high-risk threshold (VGI > 1). Khanom et al. (2022) provide a qualitative

basis for these values, detailing a chain of vulnerabilities (e.g. natural

disasters and urban risks such as violence and restricted mobility) and adaptive

strategies (e.g. cooperatives and handicraft production). These findings

correspond to a VGI score of 1.5, indicating high vulnerability due to combined

climatic and patriarchal pressures relative to weaker social and economic

support systems. UN Women (2024) provide the theoretical framework for the VGI,

emphasising its applicability to contexts such as Bhola, where the intersection

of gender and climate amplifies risks. The Global Report on Internal

Displacement (2024) and Ahmed & Eklund (2021) contextualise the scale of

displacement and gender-specific challenges further, thereby reinforcing the

environmental and social factors captured in the VGI calculation.

Application to the Dry Corridor

Climate exposure: Severe droughts and glacier loss

of 30–50% over four decades generate food insecurity and displacement (WMO,

2022; Almulhim et al., 2024). Scores: 4 (high vulnerability due to droughts and

agricultural dependency; WMO, 2022).

Patriarchal norms: Restrictions on land access and

a high incidence of gender-based violence (United Nations, 2019; Mijangos,

2023). Scores: 4 (significant restrictions on access to resources; United

Nations, 2019).

Social Networks: Although cooperatives exist,

displacement limits their effectiveness (Tarrés et al., 2014; Andersen et al.,

2017). Scores: 3 (moderate networks limited by displacement; Tarrés et al.,

2014).

Economic opportunities: Limited access to formal

employment and microfinance leads to dependence on informal activities

(Rojas-Rendon & Valle, 2024). Scores: 4 (limited access to employment and

credit; Rojas-Rendon & Valle, 2024).

Social Networks: 3 (moderate networks limited by

displacement; Tarrés et al., 2014).

Economic Opportunities: 4 (limited access to

employment and credit; Rojas-Rendon & Valle, 2024).

GVI calculation: GVI = 4 + 4 + 3 + 4 = 3.75

Result: A GVI of 3.75 indicates high vulnerability,

surpassing Bangladesh's GVI of 1.5 (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparisons with Bangladesh.

Table 1.

Comparisons with Bangladesh.

| Dimension |

Bangladesh

(Asia) |

Dry Corridor

(Latin America) |

Comparison |

| Climate Exposure |

3 |

4 |

Higher in the Dry Corridor due to severe droughts and less adaptation (WMO, 2022) |

| Patriarchal Norms |

3 |

4 |

More restrictive in the Dry Corridor due to limited access to land (United Nations, 2019) |

| Social Networks |

2 |

3 |

Stronger in Bangladesh due to the presence of NGOs (Khanom et al., 2022) |

| Economic Opportunities |

2 |

4 |

Less access to microfinance and employment in the Dry Corridor (Rojas-Rendon & Valle, 2024) |

| GVI |

1.5 |

3.75 |

Higher vulnerability in the Dry Corridor |

A comparative analysis of the GVI for displaced

women in the Dry Corridor of Central America (GVI: 3.75) and in Bangladesh

(GVI: 1.5) shows that the Dry Corridor is experiencing greater gender

vulnerability. This is due to more severe climate exposure (4 vs. 3) caused by

prolonged droughts and the loss of agricultural livelihoods (WMO, 2022;

Almulhim et al. , 2024), compared to cyclones in Bangladesh where early warning

systems mitigate the impact (Ahmed & Eklund, 2021). Patriarchal norms are

also more restrictive in the Dry Corridor, where there is limited access to

land and a high incidence of gender-based violence (United Nations, 2019;

Mijangos, 2023). In contrast, Bangladesh has made progress in terms of

community participation (Khanom et al., 2022). Social networks are more robust

in Bangladesh (2 vs 3) thanks to consolidated cooperatives and NGOs compared to

the social fragmentation in the Dry Corridor (Tarrés et al., 2014; Andersen et

al., 2017). Similarly, economic opportunities are more limited in the Dry

Corridor (4 vs. 2), with less access to microfinance and formal employment

(Rojas-Rendon & Valle, 2024) than in Bangladesh, where microcredit

programmes are more prevalent (Khanom et al., 2022). These differences

highlight the need for specific policies in Latin America that strengthen

community networks and economic access by adapting lessons from Bangladesh in

order to reduce gender vulnerability in contexts of climate-induced

displacement.

A comparative analysis of the Central American Dry

Corridor and Bangladesh reveals significant disparities in gender vulnerability

to climate-induced displacement, as indicated by the respective scores on the

GVI: 3.75 for the Dry Corridor and 1.5 for Bangladesh. These disparities stem

from various factors, including political systems, climates, migration patterns

and protection policies, all of which influence the experiences of displaced

women.

Bangladesh's political system, despite facing

corruption challenges, operates under a parliamentary democracy that has

enabled progress in climate adaptation policies and fostered community

participation among women through cooperatives and NGOs (Khanom et al., 2022;

Ahmed & Eklund, 2021). By contrast, countries in the Dry Corridor

(Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua) have fragile democracies

characterised by political instability and structural violence. Climate

policies are limited by a lack of resources and coordination, as evidenced by

the SICA Regional Action Plan for Climate Change (Mijangos, 2023; Rojas, 2024).

Furthermore, female representation in decision-making is significantly lower in

the Dry Corridor (20–30% compared to 35% in Bangladesh), which exacerbates the

exclusion of displaced women (UN Women, 2024).

In terms of climate, Bangladesh is exposed to

cyclones, floods and riverbank erosion, with a moderate GVI score of 3. This is

mitigated by early warning systems and adaptation measures such as dikes and

shelters (Ahmed & Eklund, 2021). In contrast, the Dry Corridor experiences

prolonged droughts and agricultural land loss, with severe climate exposure (a

GVI score of 4), exacerbated by phenomena such as El Niño. These events have

caused agricultural losses of up to 60% (WMO, 2022; Almulhim et al., 2024). These

conditions generate greater food and water insecurity in the Dry Corridor,

disproportionately affecting rural women who depend on agriculture for their

livelihood.

Migration patterns differ too: in Bangladesh,

migration is primarily from rural areas to cities such as Dhaka or Cox's Bazar,

where displaced women integrate through community networks, albeit under

precarious conditions (Khanom et al., 2022). In the Dry Corridor, displacements

are both internal and cross-border towards Mexico or the United States. There,

they face legal barriers and risks of violence due to restrictive migration

policies and the securitisation of borders (Murray-Tortarolo & Salgado,

2021; United Nations, 2019).

The greater vulnerability in the Dry Corridor can

also be explained by more restrictive patriarchal norms (a score of 4 compared

to 3 in Bangladesh), which limit women’s access to land and expose them to high

rates of gender-based violence. Indeed, 70% of women face legal barriers to

land ownership (Mijangos, 2023). In Bangladesh, social networks are stronger (a

score of 2 compared to 3) thanks to well-established cooperatives and NGOs. In

contrast, social fragmentation in the Dry Corridor limits community support

(Tarrés et al., 2014; Andersen et al., 2017). Additionally, economic

opportunities are more limited in the Dry Corridor (score of 4 compared to 2),

with less access to microfinance and formal employment. This is in contrast to

Bangladesh, where microcredit programmes such as those of the Grameen Bank are

widespread (Rojas-Rendon & Valle, 2024; Khanom et al., 2022).

To address these vulnerabilities, protection

policies in the Dry Corridor could be adapted based on lessons learned in

Bangladesh. For example, strengthening community networks inspired by women’s

cooperatives in Bhola could promote climate-resilient agriculture and

handicraft activities, supported by local NGOs and programmes such as the

Alliance for the Dry Corridor (Andersen et al., 2017). Digital platforms, such

as blockchain-based identities, could facilitate access to resources (World

Economic Forum, 2023). Secondly, microfinance programmes similar to those in

Bangladesh could focus on green sectors such as agroecology, funded by the

Green Climate Fund (Green Climate Fund, 2024). Thirdly, to combat gender-based

violence, the establishment of safe shelters and mobile technology-based

community alert systems is proposed, combined with educational campaigns

integrating ancestral knowledge (Huyer et al., 2020). Finally, legal frameworks

could be expanded to include the Escazú Agreement or introduce regional

'climate visas', ensuring safe mobility and access to services in line with

global proposals (Cisneros et al., 2024; Madrigal, 2021). By integrating

intersectional approaches, these strategies could reduce GVI in the Dry

Corridor by 20–30%, positioning women as key agents in climate resilience

(Khanom et al., 2022).

4. Materials and Methods

This theoretical research was conducted using a

qualitative approach (Lim, 2025), combining a systematic literature review

(Ebidor & Ikhide, 2024) and a case study (Priya, 2021). Adopting a

critical-interpretative perspective (Elliott & Timulak, 2021), the study

problematises structures of power and explores the intersections between

gender, climate and migration. This methodological complementarity highlights

both the complexity of the academic literature and the disproportionate effects

evidenced in the case study.

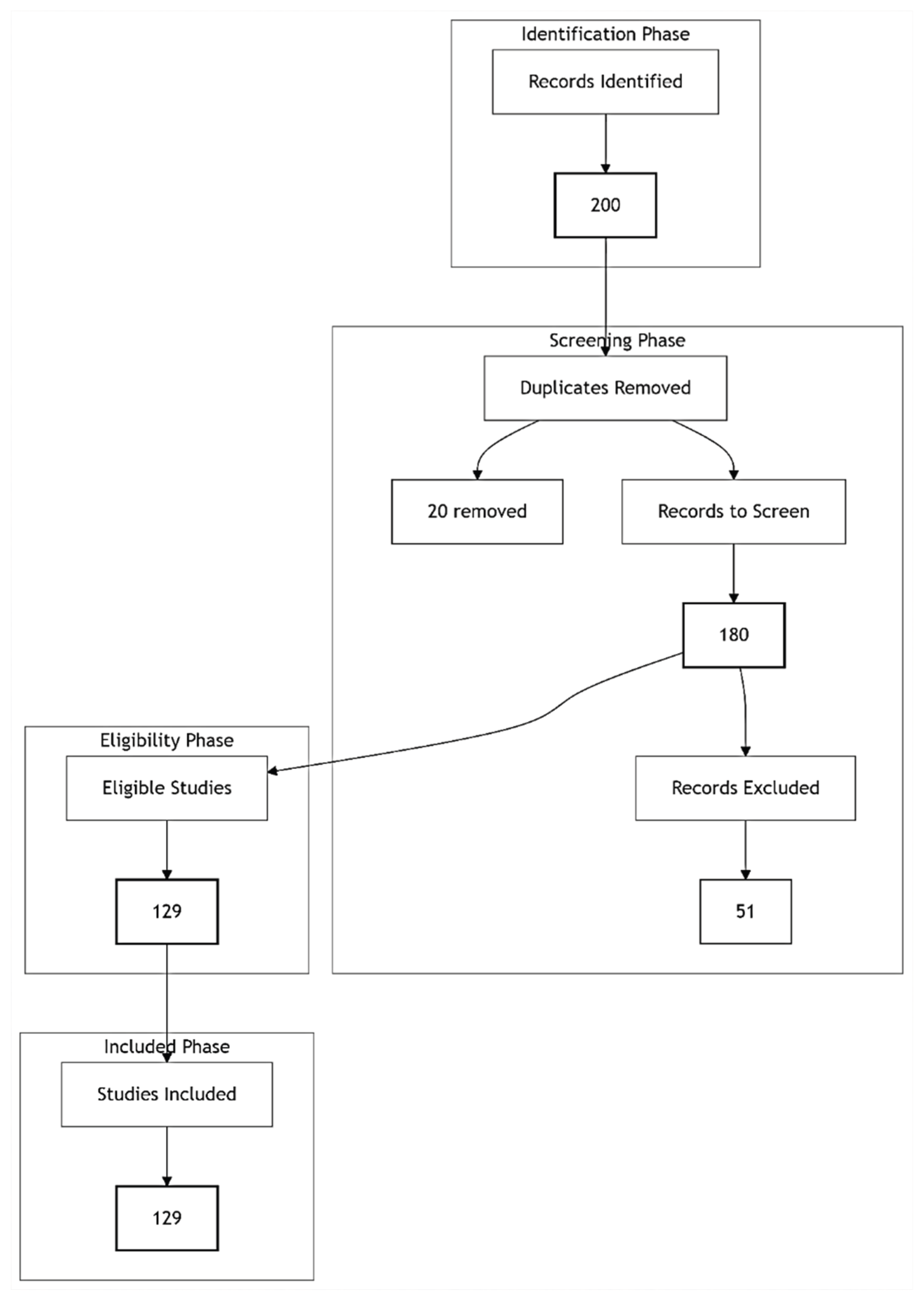

The systematic literature review adheres to the

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses)

guidelines, as adapted for qualitative and scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco

et al., 2018). This process ensures rigour, transparency and reproducibility in

the selection of evidence (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the stages of the review process.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the stages of the review process.

PRISMA process phases:

Identification: Searches were carried out in

academic databases (SpringerLink, PubMed, PLOS, SAGE, MDPI, Oxford Academic,

Cambridge Core and BMC) and on the websites of international organisations.

Keywords included 'gender', 'climate displacement', 'refugee women', and 'Latin

America'. A total of 200 records were identified, after duplicates were

excluded.

Screening: The inclusion criteria were

peer-reviewed articles published between 2014 and 2025 that focused on the

intersection of gender, climate and migration in Latin America or comparable

contexts. Exclusion criteria included non-qualitative studies, irrelevant

research and studies without open access. Of the 180 screened records, 51 were

excluded.

Eligibility: A full review of 129 texts was

conducted to assess quality and relevance, particularly with regard to

differentiated vulnerability.

Inclusion: Ultimately, 129 documents were included

in the thematic analysis.

In addition to the PRISMA protocol, the research

design incorporated a complementary methodological framework comprising three

interrelated phases: heuristics, hermeneutics and theorisation. This

multi-layered approach ensured the rigorous and systematic integration of

diverse forms of knowledge, maintaining a critical and interpretative

perspective throughout the study.

The heuristic phase concentrated on the search,

selection and categorisation of relevant materials (Ozertugrul, 2017). Rather

than functioning as a simple exercise in data collection, this stage aimed to

map the conceptual terrain by engaging with recent academic publications,

policy documents and feminist scholarship. Emerging debates were identified and

epistemological gaps revealed, particularly in relation to the intersection of

gender, climate change, and forced displacement.

Building upon this foundation, the hermeneutic

phase (Butler, 1998) involved conducting an interpretative analysis of the

literature and discourses that had been identified. Categories such as 'climate

woman', 'gendered forced displacement', and 'climate refugees and impacts' were

examined. This phase enabled the interrogation of how language, narrative

practices and relations of power shape the academic and policy framing of

women's differentiated experiences of climate-induced migration. In doing so, the

hermeneutic approach deepened our critical understanding of the structural

inequalities embedded in the discursive construction of vulnerability and

resilience.

The final phase, theorisation, integrated insights

from the previous stages into a coherent explanatory framework. This stage was

concerned not only with synthesis, but also with constructing a critical

account of the historical and political evolution of women’s relationship with

climate. It traced this trajectory from its conceptual origins to its current

articulation in urban and transnational contexts. In this way, the theorisation

stage provided the necessary framework to connect empirical findings with

broader discussions on gender justice, environmental change, and climate

resilience.

The documentary analysis was structured into three

interconnected levels (Ebidor & Ikhide, 2024; Elliott & Timulak, 2021).

The first-order analysis focused on identifying and validating sources to

ensure alignment with the study's objectives. A second-order analysis mapped

argumentative patterns and epistemological ruptures, situating the debates

within critical feminist and climate migration literature. A third-order

analysis then synthesised knowledge through critical discourse analysis and feminist

hermeneutics to produce an interpretative meta-narrative capable of connecting

empirical observations with theoretical innovation. This layered design

combined breadth, through systematic heuristics, and depth, through hermeneutic

and theoretical integration. The result was a nuanced and critical

understanding of the intersection between gender, climate and displacement that

foregrounds the structural asymmetries shaping women's differential

vulnerabilities and forms of resistance.

5. Results

The results of the analysis reveal a worrying

reality: climate change is exacerbating gender inequalities, particularly in

Latin America, leading to forced displacement and making women vulnerable in

situ and ex situ. The literature review revealed a complex interplay of

factors that increase women's vulnerability to displacement. A number of social

barriers have been identified that hinder their adaptive capacity; however,

these women have shown remarkable resilience, relying on community networks and

ancestral knowledge. Nevertheless, these strategies are inadequate given the

scale of the challenges posed by climate change and forced migration. The case

study examined here enriches the understanding gained through documentary

analysis. Empirical evidence shows that in crisis contexts, displaced women

emerge as natural leaders in resource management and community articulation.

These women have created spaces for negotiation from below by organising

themselves into cooperatives, preserving traditional knowledge in urban

contexts and linking up with transnational social movements. Their practices of

resistance open up new possibilities for reconfiguring climate adaptation from

a feminist and territorial perspective. Disputes over resources, migration

controls and the securitisation of borders show how forced displacement creates

spaces of conflict in which women fight not only for survival, but also for the

right to exist and to transform their living conditions. The geopolitical

transformation of forced displacement in Latin America opens up a field of

tensions and opportunities. Areas such as the Caribbean, the Amazon, the Andes

and the Central American Dry Corridor face the combined pressures of natural

disasters and resource conflicts. This reality underscores the urgency of

implementing public policies that not only recognise but also empower women's

proactive role in responding to climate change, capitalising on their ability

to turn adversity into opportunities for social and economic development.

The analysis concludes that without structural

changes, Latin American women in situations of displacement will continue to be

affected by the climate crisis. This vulnerability manifests itself not only in

the loss of their livelihoods, but also in the perpetuation of entrenched

social inequalities and gender gaps. This scenario brings us back to the

question: What are the social, economic and cultural factors that influence the

vulnerability and adaptive capacity of Latin American women in the face of forced

displacement, and what strategies have they developed to cope with it? The

results of the analysis lead us to answer this question:

Women in Latin America face multifaceted challenges

due to climate change. These include entrenched gender roles, economic

inequalities, barriers to accessing resources, legal gaps in international law,

violence, systemic discrimination and exclusion from decision-making processes.

These challenges are further compounded by intersecting inequalities. However,

their traditional knowledge, resource management skills and natural leadership

offer opportunities for climate solutions. These can be enhanced through

international cooperation, specific legal frameworks, gender-focused climate

education, microfinance, job creation, community leadership and inclusive

policies. As key agents of change, they require gender-responsive public

policies, specialised agencies that integrate the environment, equity, and

social development, and strategic economic and educational initiatives to

facilitate a just transition that is aligned with international commitments.

6. Discussion

Intersectionality in women's studies has gained

visibility in the environmental debate, recognising women's historical role in

resource management and adaptation to climate change (Davis & Shaw, 2001).

However, an uncritical perspective can reinforce gender stereotypes and place a

disproportionate burden on women to solve the climate crisis (Turquet et al.,

2023; Pinho-Gomes & Woodward, 2024). This narrative needs to be analysed in

light of the differentiated vulnerabilities women face due to structural inequalities

and access barriers in contexts of institutional fragility. While the category

of climate refugee makes a critical situation visible (Morera & Biderbost,

2023), it lacks international legal recognition (UNHCR, 2001), which limits its

usefulness for effective rights protection (Sussman, 2023). Initiatives such as

'climate labs' (Johri, 2023) or blockchain-based digital identity systems

(World Economic Forum, 2023) may represent innovative advances, but if they do

not address structural inequalities, they risk replicating exclusionary power

dynamics. Proposals such as adaptive hybrid communities (Schwab Foundation for

Social Entrepreneurship, 2024) also offer promising avenues, provided that

women are actively involved in their design and governance as a counterweight

to patriarchal structures (Carter, 2015).

The case of Bangladesh (Khanom et al., 2022) offers

valuable lessons, but also highlights limitations in the direct transferability

of solutions to contexts such as Latin America. The resilience of displaced

women, while remarkable, should not substitute for the responsibility of states

to guarantee rights, nor should it romanticise traditional knowledge without

assessing its applicability in contemporary urban contexts. The discourse on

women's empowerment in climate action must be accompanied by an analysis of the

power structures that perpetuate inequality (Ripple et al. 2024). While women's

participation in decision-making is essential, focusing solely on gender

solutions can distract from the systemic changes needed in governance,

economics and energy policy (Du, 2024).

In Latin America, there has been significant

progress in the legal recognition of climate change. Ecuador has

constitutionalised the right to protection from its effects (Toaquiza, 2024),

and archaeological evidence in Peru shows that women played a central role in

ancient climatic migrations (Shady, 2006a; 2006b). Other countries have enacted

legislation: Mexico, with its General Law on Climate Change; Colombia, through

laws and decrees linking climate change and land use planning (Madrigal, 2021);

and Costa Rica, with its ambitious Decarbonisation Plan 2018-2050 (Banerjee et

al. 2024). Chile enacted its Framework Law on Climate Change in 2022;

Argentina, its National Plan with a gender perspective (Moraga, 2022); while

Brazil, despite its national policy, faces questions about weak implementation

(de Figueiredo Machado, 2024). This convergence between contemporary policy

frameworks and historical evidence highlights the persistence of climate

challenges in Latin America and the evolution of social and legal responses.

However, there is still a need to strengthen protection policies with

intersectional, participatory and transformative approaches to ensure climate

and gender justice in the region.

6.1. Study Limitations

Limitations of the study include biases arising

from the predominance of literature produced in hegemonic knowledge centres,

which may sideline local perspectives (Galdas, 2017). The theoretical nature of

the research imposes constraints on directly capturing lived experiences, while

the selection of sources in Spanish and English may have excluded relevant

material. Moreover, there is a risk of reproducing colonial biases when Latin

American realities are interpreted through Western frameworks. Although the

focus on gender has been central, the omission of other intersecting variables

such as ethnicity or social class limits a more holistic understanding of the

phenomenon.

7. Conclusions

The intersection of gender, migration and climate

change highlights the key role of women as agents of change in contexts of

forced displacement. Their traditional knowledge, combined with modern

adaptation strategies, positions them as pillars in building community

resilience. Although the figure of the female climate refugee lacks

international legal recognition, her situation reflects specific

vulnerabilities that require institutional responses with an intersectional

approach. The case of Bangladesh shows how, despite the challenges, displaced

women develop support networks, leadership and sustainable solutions. For Latin

America, a strategy based on three pillars is proposed: economic empowerment

with adapted financial instruments, strengthening of community networks, and

training that integrates ancestral knowledge and climate innovation. It also

highlights the importance of optimising access to the Green Climate Fund

through institutional strengthening and regional cooperation. The proposal

calls for a multi-level approach with inter-institutional coordination,

innovative financing, cultural awareness and participatory monitoring systems,

supported by political commitment and community participation. Finally, it

highlights the need to integrate gender equity and sustainability into climate

policy, using technologies such as blockchain to ensure transparency and

participation. This is the only way to strengthen regional adaptive capacity

and consolidate women as protagonists of social transformation in the face of

the climate crisis.

Author Contributions

DRLM: Conceptualization, methodology, formal

analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and

editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abd-Elaty, Ismail; Alban, Kuriqi; Ashraf, Ahmed. Assessing salinity hazards in coastal aquifers: implications of temperature boundary conditions on aquifer–ocean interaction. Applied Water Science 2024, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Saleh; Elizabeth, Eklund. Climate change impacts in coastal Bangladesh: migration, gender and environmental injustice. Asian Affairs 2021, 52(1), 155–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, William; Isabel, Ruiz; Carlos, Vargas-Silva. Policy preferences in response to large forced migration inflows. World Development 2024, 174, 106462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, Dana. The Return of Donald Trump. Survival 2024, 66(6), 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance of Bioversity International and International Centre for Tropical Agriculture. Forced displacement in the context of the adverse effects of climate change and conflict. Global trends: Forced displacement in 2023; Produced by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2024; pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, Abdulaziz; Gabriela, Alverio; Ayyoob, Sharifi; et al. Climate-induced migration in the Global South: an in depth analysis. npj Climate Action 2024, 3, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Lykke; Dorte, Verner; Manfred, Wiebelt. Gender and Climate Change in Latin America: An Analysis of Vulnerability, Adaptation and Resilience Based on Household Surveys. Journal of International Development 2017, 29, 857–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Disaster Preparedness Center. Applying a gender lens to climate actions: why it matters, Climate Talks Series: CARE for South Asia Project, Bangkok, Thailand. 2021. Available online: https://wrd.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/2021-q74Xpc-ADPC-Gender_Mainstreaming_Policy_Brief-ADPC.pdf.

- Banerjee, Onil; Martin, Cicowiez; et al. The economics of decarbonizing Costa Rica's agriculture, forestry and other land uses sectors. Ecological Economics 2024, 218, 108115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos; Christovam. Heat waves, climate crisis and adaptation challenges in the global south metropolises. PLOS Climate 2024, 3(3), e0000367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, Andres; Rodrigo, Taborda; Rueda, Ximena. Time Poverty: An Unintended Consequence of Women Participation in Farmers’ Associations. Social Indicators Research 2025, 178, 225–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, Carolina; Knipper Michael; et al. Climate change, migration, and health: perspectives from Latin America and the Caribbean. The Lancet Regional Health – Americas 2024, 40, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, Lia; Robert, Beyer; et al. Climate shaped how Neolithic farmers and European hunter-gatherers interacted after a major slowdown from 6,100 BCE to 4,500 BCE. Nature Human Behaviour 2020, 4, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharwani, Nilofer; Thomas, Hodges; et al. 'Just leader? No, lideresa!' Experiences of female leaders working in climate change disaster risk reduction and environmental sustainability in the global south. Environmental Research: Climate 2024, 3(4), 045008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakes, Elizabeth; Carole, Dalin; et al. Impacts of the global food system on terrestrial biodiversity from land use and climate change. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogin, Barry; Jared, Bragg; Christopher, Kuzawa. Humans Are Not Cooperative Breeders but Practice Biocultural Reproduction. Annals of Human Biology 2014, 41(4), 368–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, Diane. The Dynamics of Gender in Early Agricultural Societies of the Near East. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2010, 35(2), 503–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difabio, Elbia. Fiestas agrarias en honor de Deméter en la Antigua Grecia. RIVAR (Santiago) 2021, 8(24), 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buben, Radek; Karel, Kouba. Democracy and Institutional Change in Times of Crises in Latin America. Journal of Politics in Latin America 2024, 16(1), 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Tom. Towards a hermeneutic method for interpretive research in information systems. Journal of Information Technology 1998, 13(4), 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, Rachel; Wrangham, Richard. The energetic significance of cooking. Journal of Human Evolution 2009, 57(4), 379–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Jimmy. Patriarchy and violence against women and girls. The Lancet 2015, 385(9978), e40–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, Tatiana; Zickgraf, Caroline. It’s Not Just about Women: Broadening Perspectives in Gendered Environmental Mobilities Research. Climate and Development 2024, 17(6), 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jie; Shi, Xinyan; et al. Impacts of climate warming on global floods and their implication to current flood defense standards. Journal of Hydrology 2023, 618, 129236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros, Paul; Israel, Solorio; Micaela, Trimble. Thinking climate action from Latin America: a perspective from the local. npj Climate Action 2024, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das; Suraj. Women's experiences and sustainable adaptation: a socio-ecological study of climate change in the Himalayas. Climatic Change 2024, 177(4), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Margaret; Shaw, Ruth. Range shifts and adaptive responses to Quaternary climate change. Science 2001, 292(5517), 673–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo Machado, Flavia; Marcela, Terra; et al. Beyond COP28: Brazil must act to tackle the global climate and biodiversity crisis. npj biodiversity 2024, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lafontaine; Joseph, Guillaume; Napier; et al. Invoking adaptation to decipher the genetic legacy of past climate change. Ecology 2018, 99(7), 1530–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, Christopher; Meave, Leakey; et al. Growth processes in teeth distinguish modern humans from Homo erectus and earlier hominins. Nature 2001, 414(6864), 628–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, Debashish; Manalo, Jaime. Gender and Adaptive Capacity in Climate Change Scholarship of Developing Countries: A Systematic Review of Literature. Climate and Development 2023, 15(10), 829–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doley, Himajyoti. Variants of Ecofeminism: An Overview. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research 2025, 7(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Jiaxing. Advancing Gender Equality in the Workplace: Challenges, Strategies, and the Way Forward. Journal of Theory and Practice of Social Science 2024, 4(4), 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebidor, Lawani-Luwaji; Ilegbedion, Ikhide. Literature Review in Scientific Research: An Overview. East African Journal of Education Studies 2024, 7(2), 211–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, Robert; Ladislav, Timulak. Essentials of descriptive-interpretive qualitative research: A generic approach. In American Psychological Association; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, Beatriz; Aurora, Miho Yanai; et al. Amazon deforestation: A dangerous future indicated by patterns and trajectories in a hotspot of forest destruction in Brazil. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 354, 120354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdas, Paul. Revisiting Bias in Qualitative Research: Reflections on Its Relationship With Funding and Impact. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2017, 16(1), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhard, Michael; Jones-Phillipson, Emma; Xoliswa, Ndeleni. Strategies for gender mainstreaming in climate finance mobilisation in southern Africa. PLOS Climate 2023, 2(11), e0000254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervacio, Herlinda; Castillo Benjamín; Villerías, Salvador. Huracán Otis en Acapulco, Guerrero: Vulnerabilidad socioeconómica y ambiental ante los impactos del fenómeno hidrometeorológico; México, Comunicación Científica., 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, Ann. Lucy’s world. Video. Science 2024, 384(6691), 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID). 2024. Geneve: The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2024/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Green Climate Fund. Annual Report 2023. Incheon: GCF. 2024. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/annual-report-2023 (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Heslin, Alison, Natalie; et al. Displacement and Resettlement: Understanding the Role of Climate Change in Contemporary Migration. In Loss and Damage from Climate Change. Climate Risk Management, Policy and Governance; Mechler, R., Bouwer, L., Schinko, T., Surminski, S., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Eds.; Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh; Helly; Eizenberg Efrat; Jabareen; Yosef. A New Conceptual Framework for Understanding Displacement: Bridging the Gaps in Displacement Literature between the Global South and the Global North. Journal of Planning Literature 2020, 35(4), 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Simon, Neubauer; Philipp, Gunz. Brain ontogeny and life history in Pleistocene hominins. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 2015, 370(1663), 20140062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugelius, Gustaf; Ramage, J; et al. Permafrost region greenhouse gas budgets suggest a weak CO2 sink and CH4 and N2O sources, but magnitudes differ between top-down and bottom-up methods. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2024, 38(10), e2023GB007969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.O; Rabett, R.J. Holocene landscape intervention and plant food production strategies in island and mainland Southeast Asia. Journal of Archaeological Science 2014, 51, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyer, Sophia; Mariola, Acosta; et al. Can We Turn the Tide? Confronting Gender Inequality in Climate Policy. Gender & Development 2020, 28(3), 571–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagernath, Jayseema; Dominique, Marié Nupen. Pseudo-feminism vs feminism - Is pseudo-feminism shattering the work of feminists? Proceedings of The Global Conference on Women’s Studies 2023, 1(1), 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri; Manjari. Feminist Perspective on Patriarchy: Its Impact on the Construction of Femininity and Masculinity. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities 2023, 4(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, Christine; Florence, Kyazze; et al. Understanding gender dimensions of agriculture and climate change in smallholder farming communities. Climate and Development 2015, 8(2), 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, Karen; Matthies, Ellen. On the importance of solidarity for transforming social systems towards sustainability. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2023, 90, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerry, Vanessa; Sadath, Sayeed. Advancing the climate change and health nexus: The 2024 Agenda. PLOS Global Public Health 2024, 4(3), e0003008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Md. Awal. Jolly, S., Ahmad, N., Scott, M., Eds.; Establishing a Human Rights-Based Approach to Climate Change-Induced Internal Displacement in the Regime of Bangladesh: Challenges and Way Forward. In Climate-Related Human Mobility in Asia and the Pacific. Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer; Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanom, Sufia; Mumita, Tanjeela; Shannon, Rutherford. Climate induced migrant’s hopeful journey toward security: Pushing the boundaries of gendered vulnerability and adaptability in Bangladesh. Frontiers in Climate 2022, 4, 922504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, Paul; Issac, Koomson. Toward Vulnerability-Responsive Climate Adaptation Decision Making: Group Inclusiveness as Prime Driver of Local Participation. Climate and Development 2024, 17(4), 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Weng Marc. What Is Qualitative Research? An Overview and Guidelines. Australasian Marketing Journal 2025, 33(2), 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Jialin; Taotao, Qian. Earth’s Climate History from 4.5 Billion Years to One Minute. Atmosphere-Ocean 2022, 60(3–4), 188–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarralde, Gonzalo; Lisa, Bornstein; et al. Does climate change cause disasters? How citizens, academics, and leaders explain climate-related risk and disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2021, 58, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loots, Lliane; Lou, Haysom. Climate Justice, Gender and Activisms. Agenda 2023, 37(3), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Morin, Diosey Ramon. Indigenous communities and their food systems: a contribution to the current debate. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2020, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Morin, Diosey Ramon. Anthropocene futures: Regeneration as a decarbonization strategy. Sustainable Social Development 2025, 3(1), 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintosh, Alison; Ron, Pinhasi; Jay, Stock. Prehistoric women's manual labor exceeded that of athletes through the first 5500 years of farming in Central Europe. Science Advances 2017, 3(11), eaao3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, Mauricio. Cambio climático, Derechos Humanos y Acuerdo De Escazú: Análisis del Acceso a la información en la gestión del Cambio climático de Colombia. Naturaleza y Sociedad. Desafíos Medioambientales 2021, 1, 117–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Laura. Navigating Transformations: Climate Change and International Law. Leiden Journal of International Law 2024, 37(3), 535–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi; Yadvinder. El concept of the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2017, 42, 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Robert. The evolution of human reproduction: a primatological perspective. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2007, 45, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mboya, Atieno. Human rights and the global climate change regime. Natural Resources Journal 2018, 58(1), 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Tejeda, Rafael; Hernández-Ayala, Jose. Links between climate change and hurricanes in the North Atlantic. PLOS Climate 2023, 2(4), e0000186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methmann, Chris; Angela, Oels. From ‘Fearing’ to ‘Empowering’ Climate Refugees: Governing Climate-Induced Migration in the Name of Resilience. Security Dialogue 2015, 46(1), 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijangos, Melissa. Las migraciones climáticas en América Latina y la protección internacional a los desplazados climáticos. GeoGraphos 2023, 14(2), 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Anurag; Shashvat, Singh. Singh, P., Ao, B., Yadav, A., Eds.; Historical Evolution of Climate Refugee Concepts. In Global Climate Change and Environmental Refugees; Springer; Cham, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, Pilar. Una nueva era del derecho ambiental: La Ley Marco de Cambio Climático en Chile a 50 años de Estocolmo. Revista de Derecho Ambiental 2022, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morera, Moises; Biderbost, Pablo. Los 40 años de la Declaración de Cartagena sobre los refugiados y la crisis migratoria venezolana. Revista Controversia 2023, 220, 251–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, Jonathan; Audrey, Pirzadeh; et al. How many people will live in poverty because of climate change? A macro-level projection analysis to 2070. Climatic Change 2023, 176, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray-Tortarolo, Guillermo; Salgado, Mario. Drought as a driver of Mexico-US migration. Climatic Change 2021, 164, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustak, Sk. Siddiqui, A.R., Sahay, A., Eds.; Climate Change and Disaster-Induced Displacement in the Global South: A Review. In Climate Change, Disaster and Adaptations. Sustainable Development Goals Series; Springer; Cham, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers; Norman. 2005. Environmental Refugees: An Emergent Security Issue Paper EF.NGO/4/05 from 22 May, presented at the 13th Economic Forum, Prague. Available online: https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/c/3/14851.pdf (accessed on 29 september 2024).

- Naciones Unidas. Los efectos de la migración en las mujeres y las niñas migrantes: una perspectiva de género. A/HRC/41/38. 2019. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/es/2019-4/5cf6ad854.pdf.

- Nusche, Deborah; Marc, Fuster; Simeon, Lauterbach. Rethinking Education in the Context of Climate Change: Leverage Points for Transformative Change. In OECD Education Working Paper No 307; Paris; OECD, 2024; Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/EDU/WKP(2024)02/en/pdf (accessed on 28 september 2024).

- Okesanya, Olalekan; Khlood, Alnaeem; et al. The intersectional impact of climate change and gender inequalities in Africa. Public Health Challenges 2024, 3, e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoth-Obbo, George. Thirty years on: a legal review of the 1969 OAU refugee convention governing the specific aspects of refugee problems in Africa. Refugee Survey Quarterly 2001, 20(1), 79–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozertugrul, Engin. A comparative analysis: Heuristic self-search inquiry as self-knowledge and knowledge of society. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2017, 57(3), 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Tianze; Xiuquan, Wang; et al. Coastal erosion and climate change: A review on coastal-change process and modeling. Ambio 2023, 52, 2034–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho-Gomes, Ana Catarina; Mark, Woodward. The association between gender equality and climate adaptation across the globe. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, Arya. Case Study Methodology of Qualitative Research: Key Attributes and Navigating the Conundrums in Its Application. Sociological Bulletin 2020, 70(1), 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Ji; Haoqi, Qian. Climate finance at a crossroads: it is high time to use the global solution for global problems. Carbon Neutrality 2023, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Nitya; Lawson, Elaine; et al. Gendered Vulnerabilities to Climate Change: Insights from the Semi-Arid Regions of Africa and Asia. Climate and Development 2017, 11(1), 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, Ellen; Fitz-Gibbon, Kate; et al. Incredible Women: Legal Systems Abuse, Coercive Control, and the Credibility of Victim-Survivors. Violence Against Women 2023, 31(3-4), 767–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripple, William; Christopher, Wolf; et al. The 2024 state of the climate report: Perilous times on planet Earth. BioScience 2024, 74(12), 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, Shannen; Bernard, Wood. Hominin life history: reconstruction and evolution. Journal of Anatomy 2008, 212(4), 394–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, Jose Rodrigo. La era de la ebullición global: desafíos y oportunidades para la resiliencia climática en la región centroamericana. Revista de Ciencias Ambientales 2024, 58(2), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rendon, Daliseth; Valle Alex Ivan. El enfoque de género como perspectiva teórica en los Estudios sobre migración climática en américa latina y el Caribe (Siglo XXI). Revista Justicia(s) 2024, 3(1), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayre, Matthew; Silvana, Rosenfeld. Staller, J.E., Ed.; Pachamama-A Celebration of Food and the Earth. In Andean Foodways. The Latin American Studies Book Series; Springer; Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship. Climate and Health: The Social Innovation Landscape in Latin America and Asia-Pacific; Geneva; World Economic Forum, 2024; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Segal, Paul. On the Character and Causes of Inequality in Latin America. Development and Change 2022, 53, 1087–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyorini; Sstyorini, Rahayu Dwi; Sri. Defying the odds: can women truly thrive in a patriarchal world? Journal of Public Health 2024, 46(4), e711–e712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shady, Ruth. La civilización Caral: Sistema social y manejo del territorio y sus recursos. Su trascendencia en el proceso cultural andino. Boletín de Arqueología PUCP 2006a, 10, 59–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shady, Ruth. Isbell, W.H., Silverman, H., Eds.; America’s First City? The Case of Late Archaic Caral. In Andean Archaeology III; Springer; Boston, MA, 2006b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Chandni; Divya, Solomon; Nitya, Rao. How Does Climate Change Adaptation Policy in India Consider Gender? An Analysis of 28 State Action Plans. Climate Policy 2021, 21(7), 958–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Amelia (Ed.) Women’s leadership in environmental action. In OECD Environment Working Papers; Paris; OECD Publishing, 2022; Volume No. 193, (accessed on 27 september 2024)Accessed on. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solorio, Israel. The ABCs of governmental climate action challenges in Latin America. npj Climate Action 2024, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]