1. Introduction

For individuals with visual or mobility impairments, navigating is a daily challenge. The complexity of navigation increases in environments without accessible construction. Traditional assistive tools, such as canes and guide dogs, provide essential support, but they are limited in their ability to dynamically detect and interpret obstacles or provide detailed spatial awareness. Electronic Travel Aid (ETA) devices have emerged, enabling individuals with impairments to detect obstacles by determining their position, distance, and size in real time, thereby facilitating navigation. Recent advances in computer vision and 3D sound generation pave the way for innovative solutions that improve the independent mobility of individuals with impairments [

1].

Computer vision uses cameras and other sensors to capture the surrounding environment in real time and process images to avoid obstacles. Techniques such as depth estimation, semantic segmentation, and edge detection allow these systems to accurately recognize objects, pathways, and potential hazards [

2]. Nowadays, computer vision performance has improved thanks to machine learning approaches.

The goal of computer vision is to create two- or three-dimensional representations of the world. Nowadays, applications of 3D representations are used in several fields, such as robotics [

3,

4], rescue operations [

5], and autonomous vehicles [

6,

7,

8,

9]; and places digitizing mapping [

10,

11]. Several technologies have been used to acquire information to generate 3D representations, including LiDARs, stereoscopic cameras, RGB-D cameras, and time-of-flight cameras. Based on the above, computer vision is a non-trivial problem spanning several tasks, such as obstacle detection, border segmentation, classification, and image generation. There are several approaches to these tasks. The most common is Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs).

Spatial sound generation, also known as 3D sound, translates the information processed by cameras in a way that is helpful for users. Spatial audio generation involves synthesizing audio through equalized headphones so that listeners perceive it as if they are present in a real scenario, even if they are not [

12]. Spatial sound incorporates the acoustic and anthropometric characteristics of the environment and human sound perception. This enables users to understand distances, directions, and object types through sound alone [

13]. This creates an intuitive, immersive guidance system that does not require constant physical interaction [

14].

The sound wave that arrives at the listener’s ears is affected by diffraction, absorption, and other phenomena [

15], depending on the direction of the wavefront incidence. The human head and torso act as natural acoustic filters between the position of the sound source and the entrance of each ear canal. These filters can be modeled as finite impulse response (FIR) systems known as head-related impulse responses (HRIRs). HRIRs are responsible for supplying a 3D sound sensation in simulated environments and providing directional cues that allow humans to distinguish sound source locations [

16]. It is worth noting that the HRIR corresponds to the system’s acoustic response in the time domain when excited by an impulsive signal, whereas the Head-Related Transfer Function (HRTF) is the equivalent representation of this response in the frequency domain. Both describe the same filtering characteristics of the head–torso–pinna system, differing only in the analysis domain. To achieve a more realistic sound, one must also consider how sound waves propagate in indoor or outdoor environments before reaching the listener’s ears.

Auralization generates audible sound from simulated, synthetized or measured data. It is typically used to show how sound propagates in a given environment. Similar to visualization, auralization allows users to experience how a space will sound, even if they are not present. It involves signal processing, acoustic modeling, and spatial audio techniques to produce realistic auditory experiences in architecture, virtual reality, and noise control applications. Auralization generates spatial sound by applying the convolution product of an anechoic sound and an impulse response. However, generating spatial sound in real time is computationally expensive. A common approach to reducing the required computational resources is to decrease the number of mathematical operations and/or simplify the models involved in the auralization process. It is worth mentioning that such a strategy may significantly reduce the sensation of 3D sound and, therefore, compromise the listener’s ability to recognize the direction of the sound source.

The integration of computer vision and 3D sound allows for the creation of multisensory navigation systems that enhance the safety, confidence, and autonomy of individuals with impairments. This concept has been explored in several studies, including those by [

8,

14,

17], and others. The recent rise of edge computing and wearable artificial intelligence can provide assistive devices that are even more responsive and adaptable [

18]. These approaches could enhance accessibility and empower individuals with impairments to have greater freedom and independence in their daily lives.

This research aims to present a prototype of assisted navigation for the visually impaired using 3D audio and computer vision with stereoscopic cameras, which were developed by the LASINAC laboratory of the National Polytechnic School of Ecuador. The prototype generates spatial audio through equalized headphones while the user navigates with pink noise in the background. This noise provides users with an auralization process that uses a public HRIR corresponding to the direction of arrival of an obstacle, which is obtained by processing images captured by stereoscopic cameras, to give them the notion of the localization of an obstacle. The sound gain increases when the obstacle is close and decreases when it is far away. In addition to detecting obstacles, the prototype can recognize them using the YOLO convolutional neural network.

1.1. Related Works

The integration of 3D audio technologies with computer vision systems for developing assistive navigation devices for visually impaired individuals has evolved through distinct technological paradigms, each contributing unique methodological approaches and scientific innovations to the field. The foundational work in this domain established the critical importance of spatial audio rendering combined with environmental perception systems. The early work of [

17] presented the application of artificial neural networks for interpolating Head Related Impulse Responses (HRIRs) in 3D sound systems, employing a committee of feed-forward multi-layer ANNs with 2-4 neurons in single hidden layers to process azimuth and elevation coordinates, achieving optimal accuracy with errors below -22 dB while demonstrating 50% computational efficiency improvement over traditional bilinear interpolation methods. Building upon similar principles, [

19] developed the NAVIG system, which integrated stereoscopic cameras operating at

pixels with binaural 3D audio spatialization through Head Related Transfer Functions (HRTFs), implementing the biologically-inspired SpikeNet algorithm for ultra-rapid image recognition capable of processing 750 visual shapes at 15 fps, while achieving 78±22% recognition rates in morphological earcon classification tests and demonstrating object localization accuracy within 22cm for indoor positioning.

Advanced localization and mapping systems have subsequently emerged as sophisticated solutions that leverage precise spatial reconstruction capabilities combined with multi-sensor fusion approaches. In 2017, Xu et al. [

8] developed a comprehensive vehicle localization methodology utilizing stereoscopic camera technology integrated with 3D point cloud maps, employing particle filtering frameworks and gradient-based image matching algorithms that achieved centimeter-level accuracy with RMS errors ranging from 0.08-0.31 meters across diverse environmental conditions, while demonstrating GPU-accelerated processing capabilities with 105ms computation times through multi-path Viterbi stereo algorithms and information-theoretic matching metrics. This precision-oriented approach was further enhanced by [

20], who designed an intelligent smart cane incorporating 2D LiDAR and RGB-D camera sensors powered by NVIDIA Jetson Nano B01, implementing Cartographer SLAM algorithms with localization accuracy of 1 m ± 7 cm and processing speeds of 25–31 FPS, while integrating an improved YOLOv5 model augmented with Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) that achieved obstacle detection speeds of 25–26 FPS and recognition accuracy rates of 84.6% for pedestrian crossings and 71.8% for vehicles.

Real-time environment reconstruction systems have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in transforming spatial perception through innovative audio feedback mechanisms and comprehensive environmental analysis. The study [

21] presents the development of EchoSee, a mobile application utilizing Apple’s ARKit framework with LiDAR scanning technology to generate dynamic 3D mesh reconstructions at 60 frames per second, implementing raycasting algorithms within Unity game engine to place six spatialized audio sources at predetermined angular offsets producing distinct pure tones, resulting in 39.8% reduction in obstacle collisions and significant improvements in Safety Performance Index scores through mathematical models quantifying seeking behavior and trajectory analysis algorithms. Complementing this approach, the authors of [

22] investigated intelligent wearable auditory display frameworks that processed real-time video streams through heterogeneous sensor fusion combining LiDAR, radar, and thermal sensors, employing time-frequency domain analysis through Wavelet and Fourier transforms for feature extraction and implementing convolutional neural networks with multi-layer perceptron algorithms for object recognition, while utilizing dynamic Bayesian networks and theory of evidence for spatial state estimation and fuzzy logic mapping for speech synthesis generation.

Artificial intelligence-powered object detection and recognition systems have contributed to sophisticated machine learning methodologies that enhance environmental perception accuracy and computational efficiency. In 2022, Ashiq et al. [

23] implemented MobileNet architecture achieving 83.3% accuracy on ImageNet dataset containing over 1,000 object categories, utilizing Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) with 0.7 threshold for frame optimization and integrating GPS/GSM modules for real-time location tracking while demonstrating superior performance with 9.1/10 total score in comparative analysis against existing devices. The study of [

24] advanced this domain through the Object Detection Model for Visually Impaired (ODMVI) framework, employing comprehensive five-phase approaches including Wiener filtering for preprocessing, multi-kernel k-means segmentation with hybridized sigmoid and Laplacian kernels, and multiple feature extraction incorporating Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT), Speeded-Up Robust Features (SURF), and Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), achieving remarkable accuracy of 76.78% and precision of 65.67% while outperforming conventional CNN algorithms. The work of [

25] contributed uncertainty-aware visual perception systems utilizing Intel RealSense D435 RGB-D stereoscopic cameras with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) trained on human eye-tracking data, implementing fuzzy logic-based risk assessment with three membership functions and achieving 85.7% accuracy, 86.0% sensitivity, and 85.2% specificity through lightweight LB-FCN architecture and morphological gradient-based ground plane removal techniques. In 2025, Das et al. [

26] developed the PathFinder system employing a novel Depth-First Search (DFS) algorithm combined with monocular depth estimation techniques, comparing six distinct approaches including Vision Language Models, Vision Transformer classification, and patch-based depth representation using Large Language Models, achieving competitive accuracy rates of 37.67% for indoor and 38.33% for outdoor navigation with response times of 0.399 seconds for indoor scenes and 1.332 seconds for outdoor environments, significantly outperforming AI-powered alternatives requiring 3-10 times longer processing periods while maintaining lower Mean Absolute Error values of 25.78° and 26.00° respectively.

Comprehensive analytical studies have provided systematic evaluations of technological convergences and empirical evidence for evidence-based development strategies. The study of [

27] presents a bibliometric analysis of 528 publications spanning 2010-2020 using CiteSpace analytical methods, revealing that computer vision techniques, particularly Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) and deep convolutional neural networks, increasingly integrated with spatial audio processing algorithms, while identifying smartphone-based implementations leveraging ARCore and ARKit frameworks as dominant platforms incorporating stereo audio feedback mechanisms and demonstrating exponential growth trends in artificial intelligence approaches after 2015. In 2019, Real and Araujo [

28] systematically analyzed Electronic Travel Aids evolution, identifying convergence requirements including 3D audio processing through HRTF algorithms, computer vision techniques with SLAM for centimeter-level positioning accuracy, and stereo-vision systems for environmental reconstruction, while highlighting smartphone-based solutions with Ultra-Wide Band technology achieving 15-20 cm accuracy as optimal technological convergence. The work of [

29] presents the review of 191 research articles published between 2011-2020, documenting diverse implementations including spatial audio cues, RGB-D cameras, Microsoft Kinect sensors, and deep learning algorithms, while identifying critical gaps in power consumption optimization and demonstrating prevalence of embedded systems utilizing Arduino platforms and IoT infrastructure. In 2023, Theodorou et al. [

30] classified 40 peer-reviewed studies utilizing RGB-D cameras, LIDAR, IMUs, and computer vision algorithms including semantic segmentation and point cloud processing, emphasizing practical implementation challenges where only 14% of reviewed solutions were deemed viable for real-world use, while identifying core technological features including low-latency navigation feedback, accurate indoor localization, and adaptive obstacle avoidance as essential requirements for commercial viability in assistive navigation systems.

1.2. Outline

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2, “Materials and Methods,” describes how the prototype functions.

Section 3, “Results”, shows the evaluation of the prototype carried out on twenty people, ten of whom were visually impaired.

Section 4, “Conclusions,” outlines the relevant findings and future work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Prototype

The stereoscopic camera, which is mounted on the user’s chest, captures two images simultaneously to enable real-time depth perception. A single board computer (SBC) processes these images and computes the position of nearby obstacles in the environment. Once the positions of the obstacles are determined, the system generates spatial audio cues that are reproduced through equalized headphones. This allows the user to perceive the direction of the obstacles via 3D sound. The prototype also plays an audio alert when an obstacle is detected by pressing a button located on the bottom right of the vest. Obstacle recognition and classification are performed using CNN with images captured by the camera.

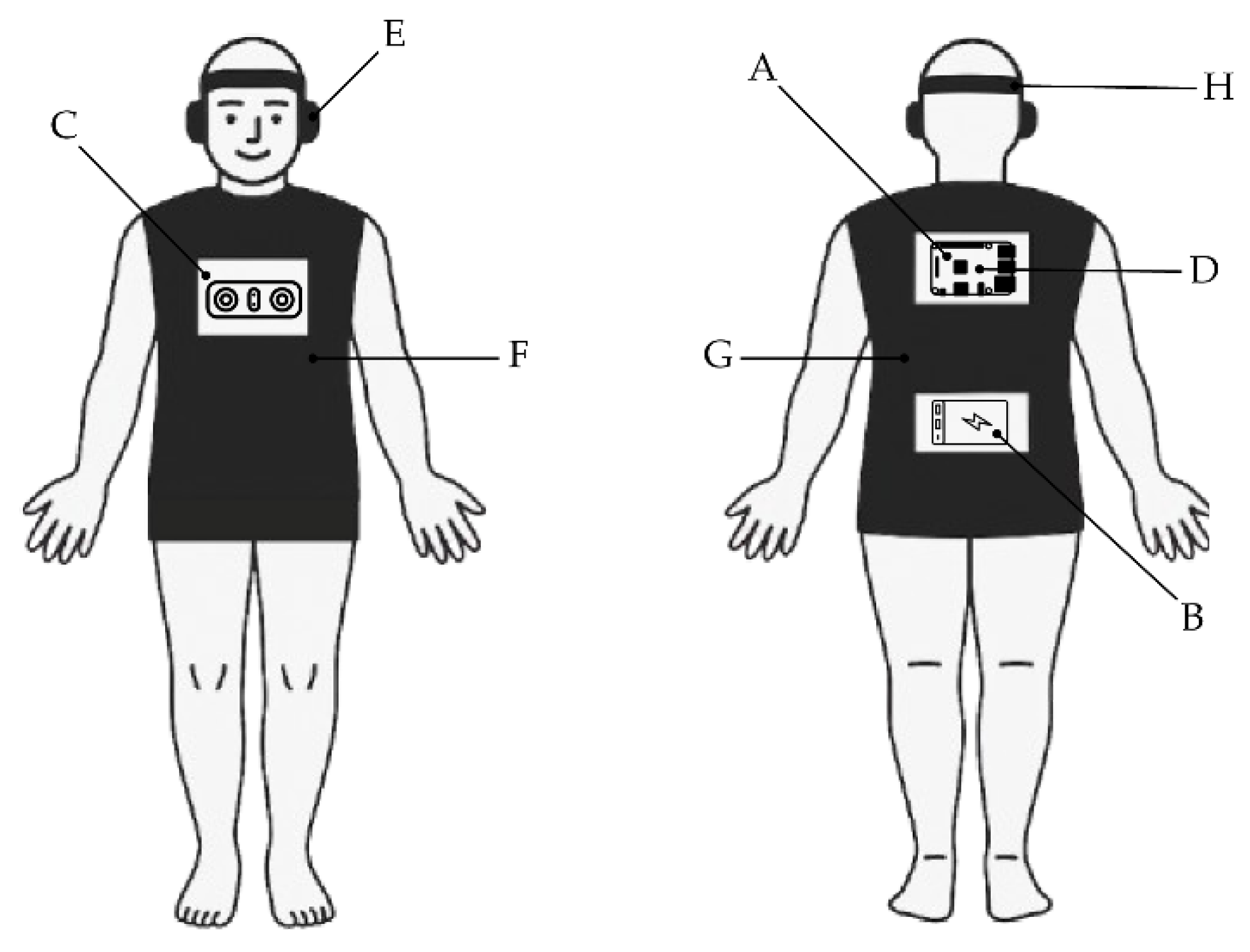

Figure 1 illustrates the overall prototype setup, including the minicomputer (A), power bank (B), stereoscopic camera (C), inertial sensors (D), headphones (E), wearable vest (F and G), headband (H), and obstacle detection button (G). The headband houses an inertial measurement unit (IMU) that tracks the user

’s head orientation in real time. This orientation data is essential for transforming the obstacle

’s position from the camera coordinate system to auditory space. This ensures that the spatial audio is generated in alignment with the user

’s relative position. The prototype uses a ZED stereoscopic camera, an NVIDIA Jetson TX SBC for processing, and a lithium polymer battery as the power source.

The prototype operation is divided into three modules: Data Acquisition and Point Cloud Positioning; User Orientation Detection and 3D Audio Generation; and Obstacle Detection and Classification. The following subsections detail each module.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Point Cloud Processing

The first step is to acquire images from a stereoscopic camera with aligned axes mounted on the prototype.

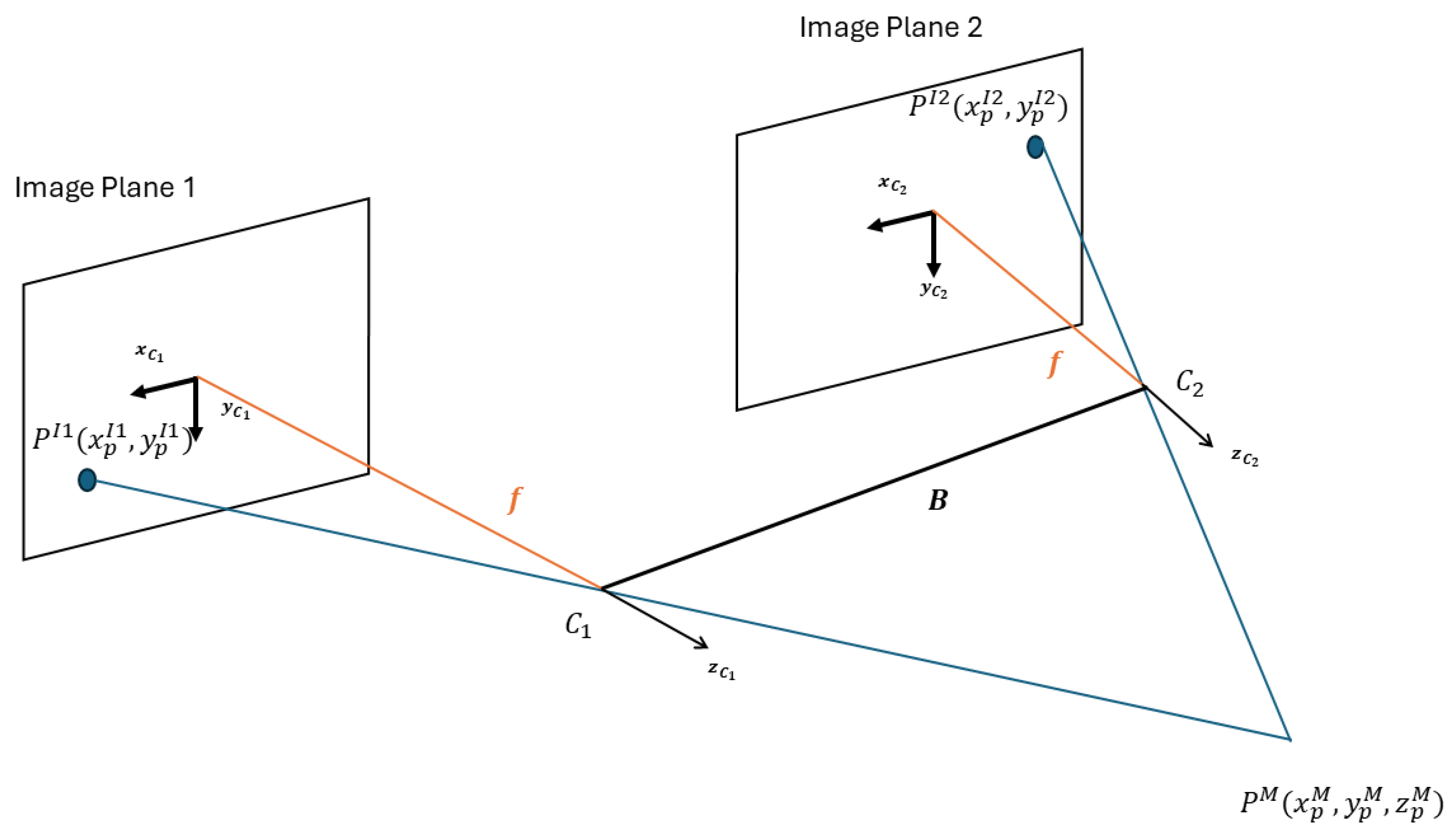

Figure 2 shows the scheme of the stereoscopic camera with aligned axes.

Next, the pixel representing a point in the real world is located in both images [

31] to determine the disparity

. Then, triangulation is used to represent the pixel in 3D coordinates in the user reference by applying the following equations:

where

is the focal distance,

stands for the distance between lenses, and

refers to the disparity. The coordinates

,

, and

represent the depth, horizontal, and vertical positions of a point in the user coordinate system, respectively.

is the position in the

axis in the first and second images.

stands for the position on the first image in the

axis.

In image processing, a point cloud refers to a collection of discrete data points from each pixel of an image in three-dimensional space. These data points represent the surfaces of objects or environments [

32]. Each point in the cloud contains spatial coordinates

and may include additional attributes, such as color, intensity, or normal vectors. Thus, point cloud is defined by:

where

is the point containing the position

in Cartesian coordinates and an additional dimension,

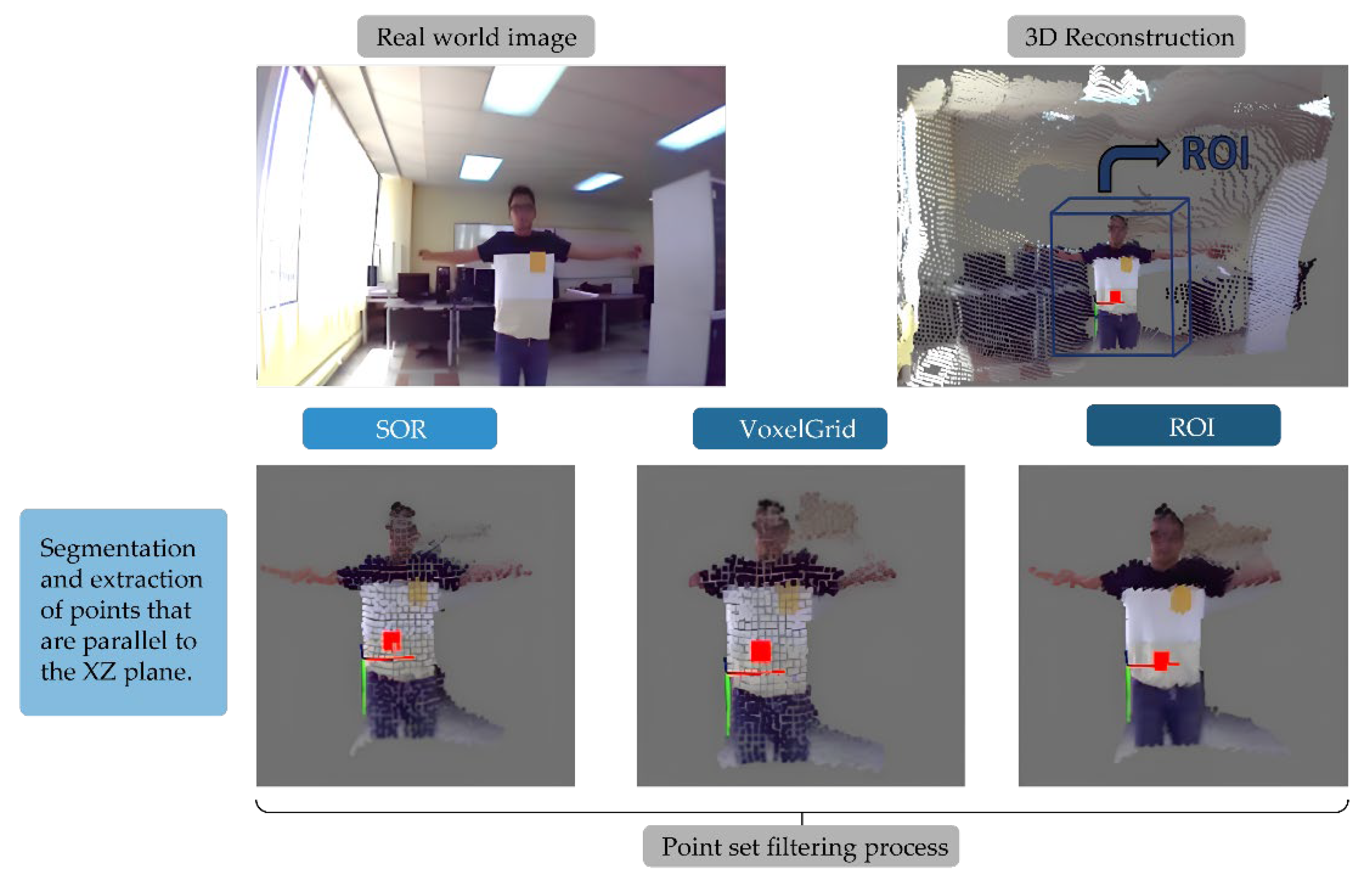

. The resulting point cloud from the aforementioned process is passed through the

Passthrough filter from the Point Cloud Library (PCL) of the Robot Operating System (ROA) to determine the Region of Interest (ROI). The ROI refers to a set of points that could contain the closest possible obstacle [

33]. In order to determine the location of the obstacle, the center of a cloud of points representing the ROI must be calculated. In this regard, two additional PCL library filters,

VoxelGrid and

SOR, were applied. These filters minimize atypical points in the ROI to reduce the number of samples. Next, the

SAC-RANSAC segmentation algorithm from the PCL library is executed to eliminate coplanar points in the cloud that don’t represent an obstacle to navigation.

Figure 3 shows the results of processing the point cloud.

Finally, the position of the nearest obstacle is computed by applying a moving average filter to the current centroid and the three previous centroids. The centroid is obtained by selecting the thirty points closest to the camera after applying point cloud processing to the images captured by the camera. The moving average filter was defined as follows:

where,

refers to the number of centers,

is the number of taps, and

stands for the shift.

2.3. User Orientation Detection and Audio Generation

The second module uses an inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensor on the user’s headband to convert obstacle positions from camera coordinates to auditory space. Then, 3D audio is generated by applying segmented convolution between the Head-Related Impulse Response (HRIR) closest to the obstacle’s position — gathered from a public database — and pink noise.

The rotation matrices then transform the obstacle position from camera coordinates to auditory space, given the head rotation (azimuth) obtained from the IMU sensor. The rotation matrices for the

and

axes were defined as follows:

where

is the azimuth angle. The user position considering the listener head as a reference is defined as:

After that, the Direction of Arrival (DOA) of the obstacle is computed by converting its position in auditory space to polar coordinates. Once the DOA is known, the closest HRIR can be determined. Next, 3D audio is generated by applying the auralization technique. This technique performs segmented convolution between the waterfall sound (waterfall sound was chosen because it is considered relaxing) and the HRIR corresponding to the user’s orientation and position. The waterfall sound provides three-dimensional sound indicating the direction of the cloud’s average point.

The corresponding HRIR was chosen from the CIPIC public HRIR database [

34]. These HRIRs were measured using a KEMAR dummy head in an anechoic chamber. Due to the sampling rate of 44,100 Hz, each HRIR has 512 samples, which cover the complete audible spectrum. Reducing the latency ensures realistic reproduction of real-time audio. Therefore, an audio block of 512 samples was used, resulting in a latency of 11.61 ms (512/44,100 Hz).

The convolution product in the time domain is given by:

where,

is the output signal of length

.

stands for the input signal of length

, and

is the impulse response signal of length

.

represents the summation index, while

and

denote the discrete Fourier transforms of the input signal and impulse response, respectively.

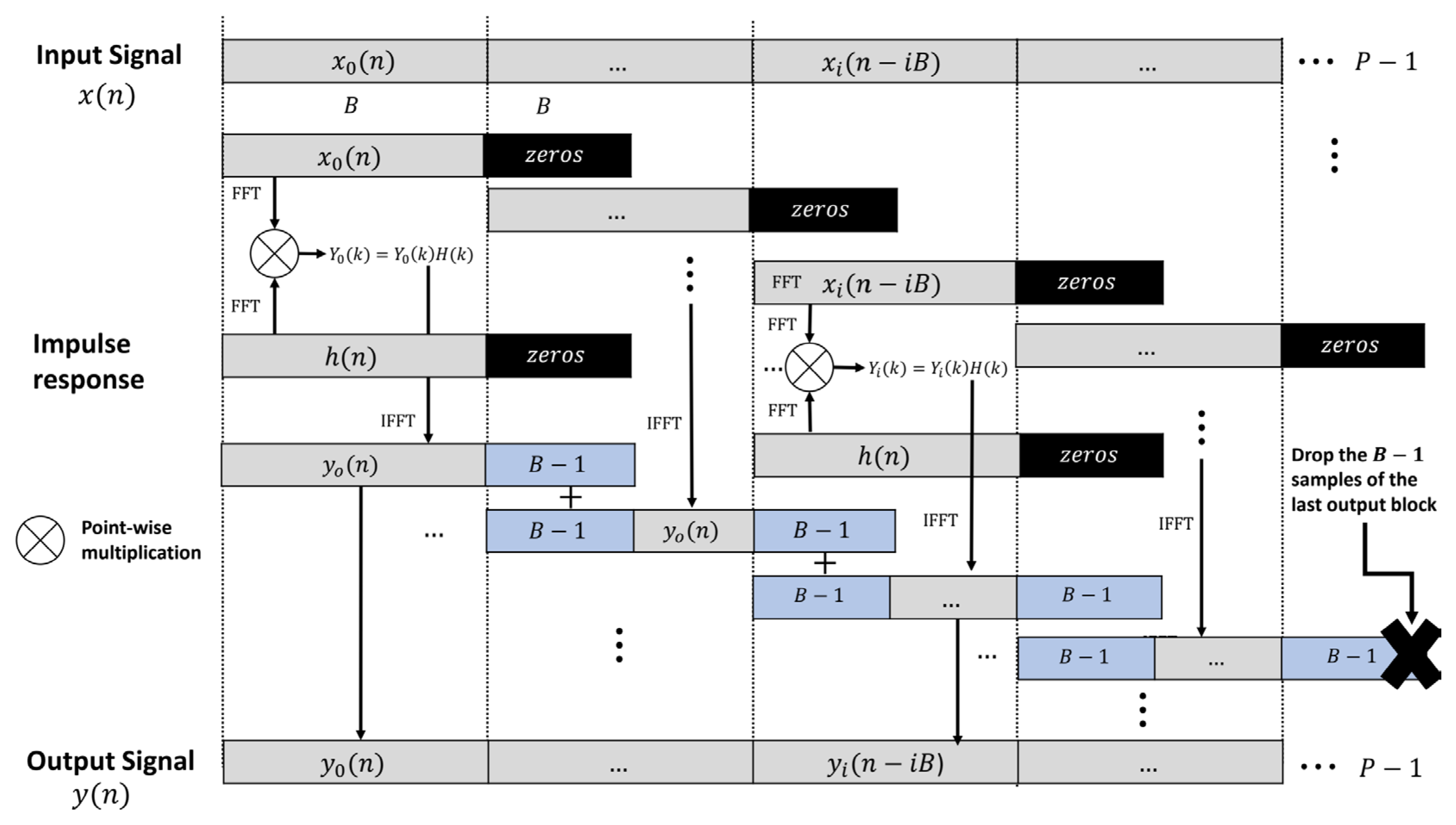

Our method applies fast Fourier transform (FFT) segmented convolution, which leverages the convolution theorem property which states that convolution in the time domain corresponds to the product of two signals in the frequency domain as established in Eq. (13).

The principle of segmented convolution divides the input signal,

, into blocks of length

. These blocks are represented as:

where

is the number of

blocks. If

is not a multiple of

, the last block must be zero-padded to match the

length. The discrete Fourier transform operations are denoted by

and its inverse by

.

The convolution of

and

can be expressed as follows:

where, the

block convolution,

, refers to the convolution of

and

. Each

is

samples long. This study applied overlap-add segmented convolution, which consists of summing the first

samples of

with the last

samples of

(i.e., overlapped samples).

Figure 4 depicts the overlap-add convolution process. More details on overlap-save convolution can be found in [

15].

The virtual reality effect is achieved by updating the head-related impulse responses (HRIRs) based on the head’s orientation and position at a given moment, since the principles governing linear, time-invariant systems are appropriate for this formulation. However, sudden head movements during testing can cause abrupt changes, leading to clicks or other undesirable audio artifacts [

35]. To address this issue, a crossfade effect is applied to the convolution of the sound with the current pair of HRIRs, which correspond to the listener’s present position, and the predicted pair of HRIRs obtained through linear interpolation. Consequently, listeners perceive smooth audio transitions during movement despite the loading of upcoming HRIRs [36].

has been divided into blocks of length B. Each input block is zero padded before applying the convolution product, resulting in an output for each block. The last samples of the previous output are added to the first samples of the current --- overlapped-add. The final samples of the last convolution block are discarded, represented by “x”.

It is worth mentioning that audio generation is a core feature of the Assisted Navigation System. It processes and generates 3D sound to emulate the sensation of sound coming from a specific location, a process known as auralization. This allows people with visual impairments to navigate.

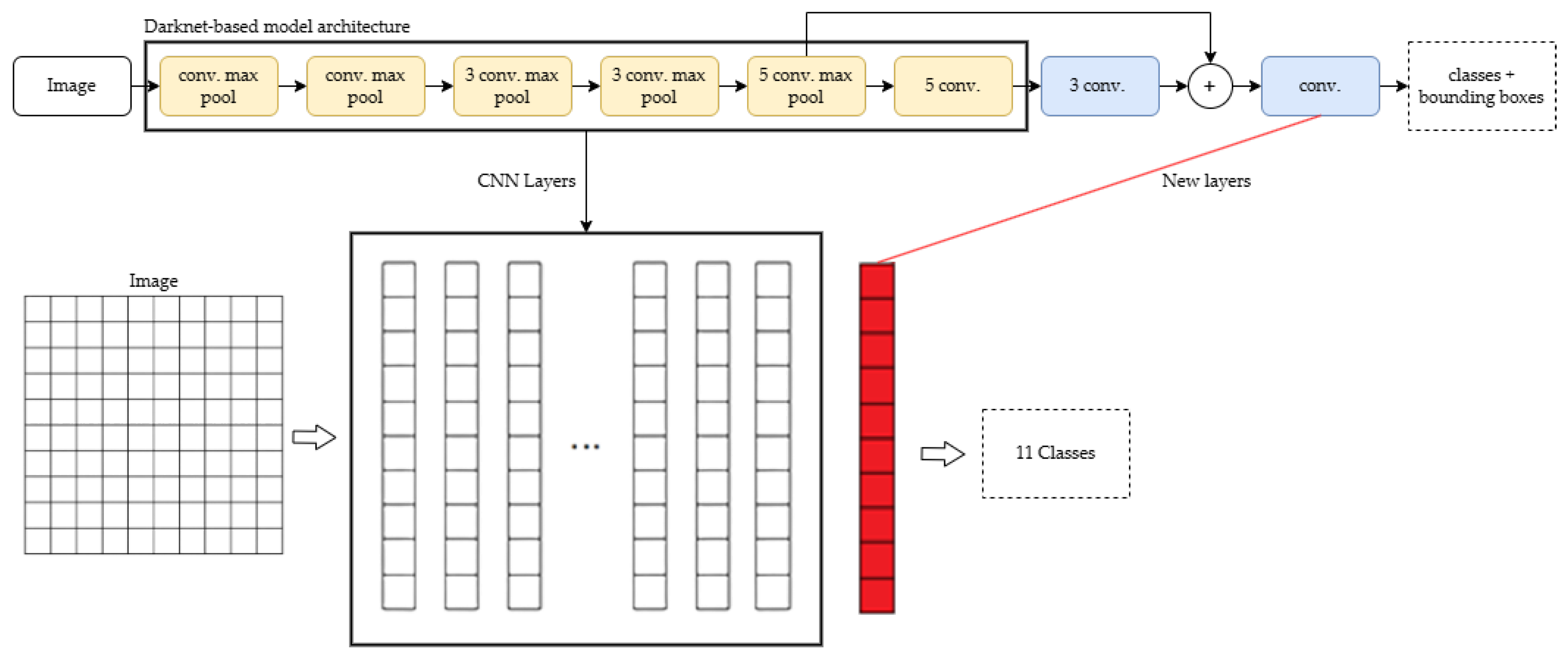

2.4. Obstacle Detection

The proposed prototype has an additional capability that allows it to recognize and detect obstacles. This is achieved by training a CNN architecture with fine-tuning and transfer learning techniques based on the Darknet computer vision model called “You Only Look Once” (YOLO). The trained YOLO can identify and classify objects in real time from images provided by the stereoscopic camera. Fine-tuning and transfer learning are neural network techniques that modify the final layers and hyperparameters of well-known, pre-trained architectures, such as Darknet or Google CNN, to classify new objects in images.

The prototype modifies the YOLO architecture by replacing the output layer with eleven neurons that correspond to the nine base architecture objects and two additional objects, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The additional objects are poles and ladders. The database consists of two parts: a public database (Pascal VOC [

35]) containing images of the first nine objects, and an additional database with images of the new objects obtained from other public databases and a data augmentation process. The final database comprised 30,764 images of the eleven objects. The database was divided into 75% for training and 25% for validation.

The computer vision unit determines an object as an obstacle when its size within the captured image is greater than 25 cm in depth and height. Then, classification through the trained and modified YOLO begins, determining the corresponding label or class. Once the identification process is complete, the processing unit emits a synthesized sound through the headphones with the name of the class or object with the highest probability, as determined by YOLO. This warns the user as long as the system is activated.

The performance of the modified YOLO model in object detection was evaluated using the mean average precision (

), intersection over union (

), and

metrics during the training and validation of the data.

is a metric used to evaluate object detection models; it measures the average precision across all classes and

thresholds. It is calculated as the mean of the average precision (AP) for each class. AP is the area under the precision-recall curve, defined as:

where

is the number of classes and

stands for the Average Precision (AP) of the

class. The

metric measures the overlap between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes. It is a ratio that quantifies the alignment of the predicted box with the actual object, defined as:

where

is the area of overlap between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes and

is the total area covered by both boxes. Recall measures the model’s ability to correctly identify positive samples. In object detection, Recall is the ratio of correctly detected objects to the total number of ground truth objects, which is computed as:

where

is the number of true positives and

refers to the number of false negatives.

3. Results

The results are divided into two sections. The first section presents the results of tests conducted with visually impaired users and with users whose eyes were covered. These tests evaluated the system’s ability to provide navigation guidance and obstacle avoidance. Reaction times, movement accuracy, and user comfort were also analyzed. The second section analyzes the results of the object detection model.

3.1. User Evaluation

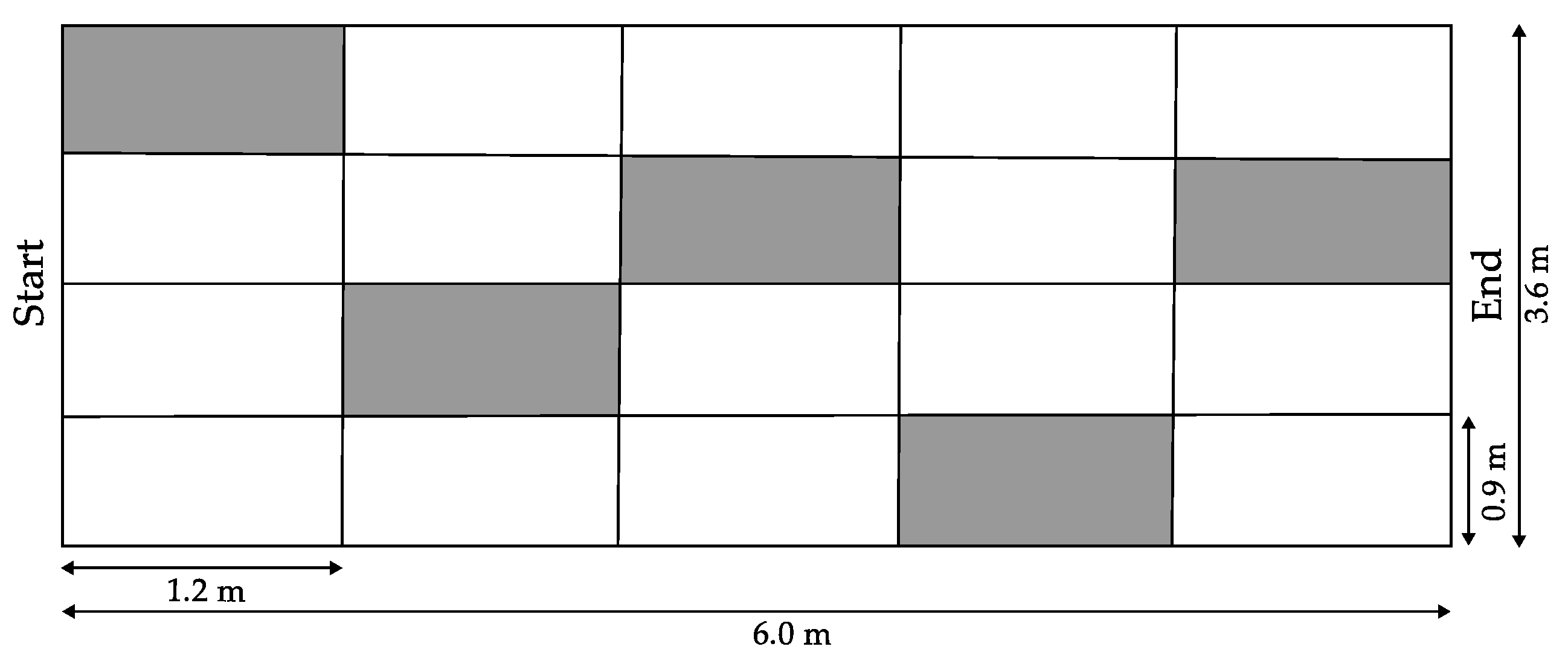

The experiment involved completing a route and avoiding obstacles in a work area within a closed environment using the prototype to evaluate the system. Ten visually impaired people and ten blindfolded people participated in the experiment. During the experiment, participants were unable to use their hands or a cane.

The tests were conducted in an area measuring: 6.0 m long and 3.6 m wide, forming a grid of five columns and four rows, each 1.2 m long and 0.9 m wide as depicted in

Figure 6. Five obstacles were placed randomly within the grid’s cells. The experiment was repeated ten times, with the locations of the obstacles changing each time. It is worth mentioning that these obstacles were students standing in the shaded area of

Figure 6.

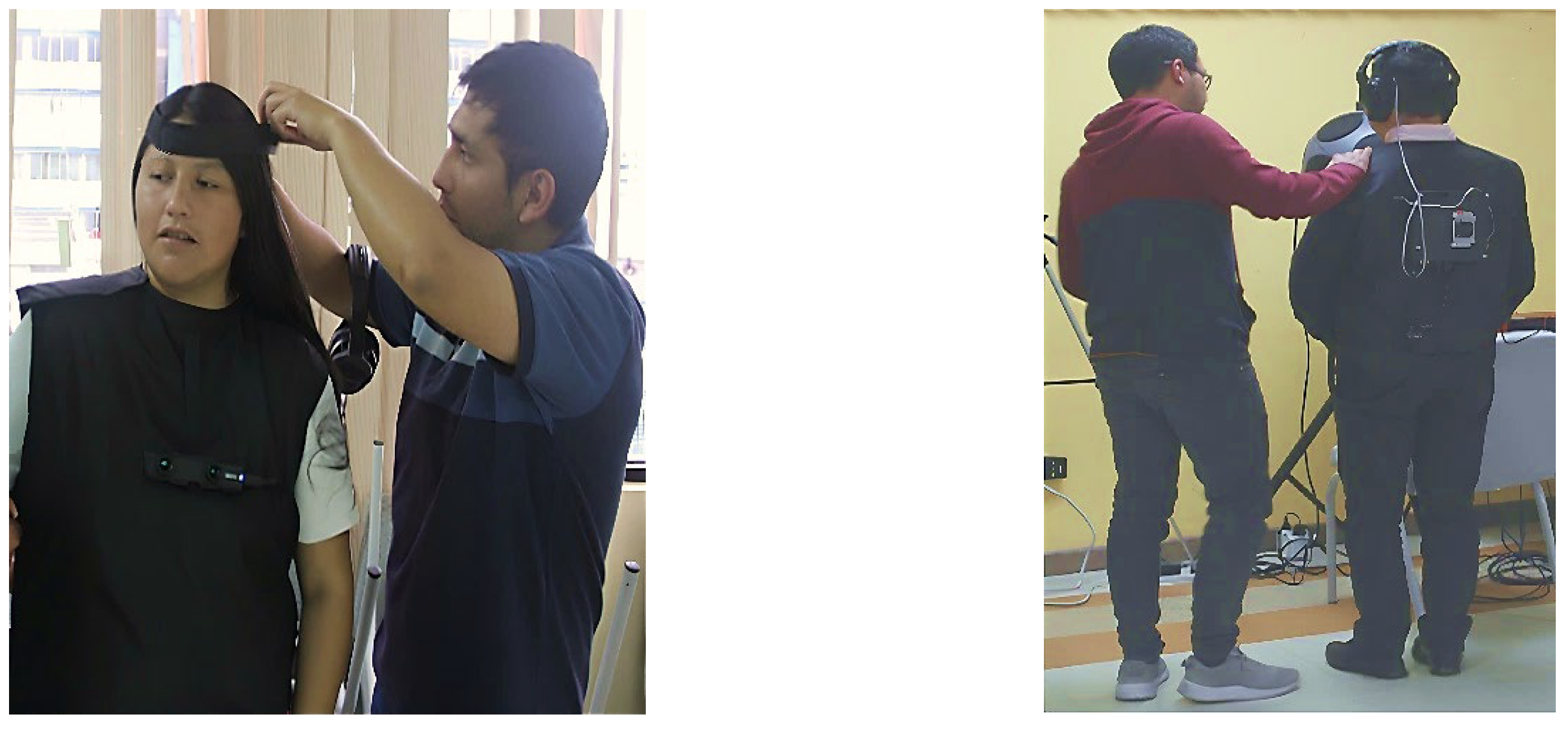

The experiment lasted approximately one hour per person. During the first 10 minutes, the participants were given general information about the procedure. Then, their anthropometric measurements (height, ear size, etc.) were taken. Next, the participant wore the prototype, and a brief explanation of how to use it lasted approximately 10 minutes, as shown in

Figure 7. Finally, the 40-minute experiment began.

The experiment consisted of participants passing through ten scenarios. It is worth mentioning that the grid was marked on the floor of the EPN University classroom. Five obstacles were randomly placed in cells of the grid. The participant’s goal was to reach the sound source without colliding with an obstacle or stepping off the grid. The sound source was located at the end of the grid and emitted a sound that guided the participant to the final destination.

The table below shows the number of collisions and time required for blindfolded participants to cross each scenario. On average, participants collided 0.35 times and took around 48 seconds to complete the scenario.

Table 1.

Average collision and times for each participant.

Table 1.

Average collision and times for each participant.

| Participant number |

Average collision |

Average time (s) |

| 1 |

0.7 |

23.61 |

| 2 |

0.5 |

87.52 |

| 3 |

0.2 |

53.42 |

| 4 |

0.7 |

79.38 |

| 5 |

1.0 |

58.61 |

| 6 |

0.3 |

47.91 |

| 7 |

0.0 |

94.36 |

| 8 |

0.5 |

41.34 |

| 9 |

0.0 |

62.13 |

| 10 |

0.3 |

41.14 |

| 11 |

0.5 |

52.59 |

| 12 |

0.0 |

21.22 |

| 13 |

0.5 |

20.95 |

| 14 |

1.1 |

31.05 |

| 15 |

0.6 |

27.39 |

| 16 |

0.0 |

45.48 |

| 17 |

0.0 |

55.47 |

| 18 |

0.0 |

31.46 |

| 19 |

0.0 |

43.49 |

| 20 |

0.0 |

41.48 |

| Average |

0.5 |

48.00 |

The results show that all subjects could perceive the spatial sound of a waterfall, which warns of an obstacle nearby. However, the level of perception and confidence varied among participants because perception of sound differs from person to person due to anthropometric characteristics that cause perception distortions. Additionally, limited training time and familiarity with the device affected the results.

The results for visually impaired and blindfolded participants revealed similar overall performance metrics in terms of collision rates and completion times. However, the visually impaired participants demonstrated greater navigational confidence and faster adaptation, likely due to their experience navigating environments without visual cues.

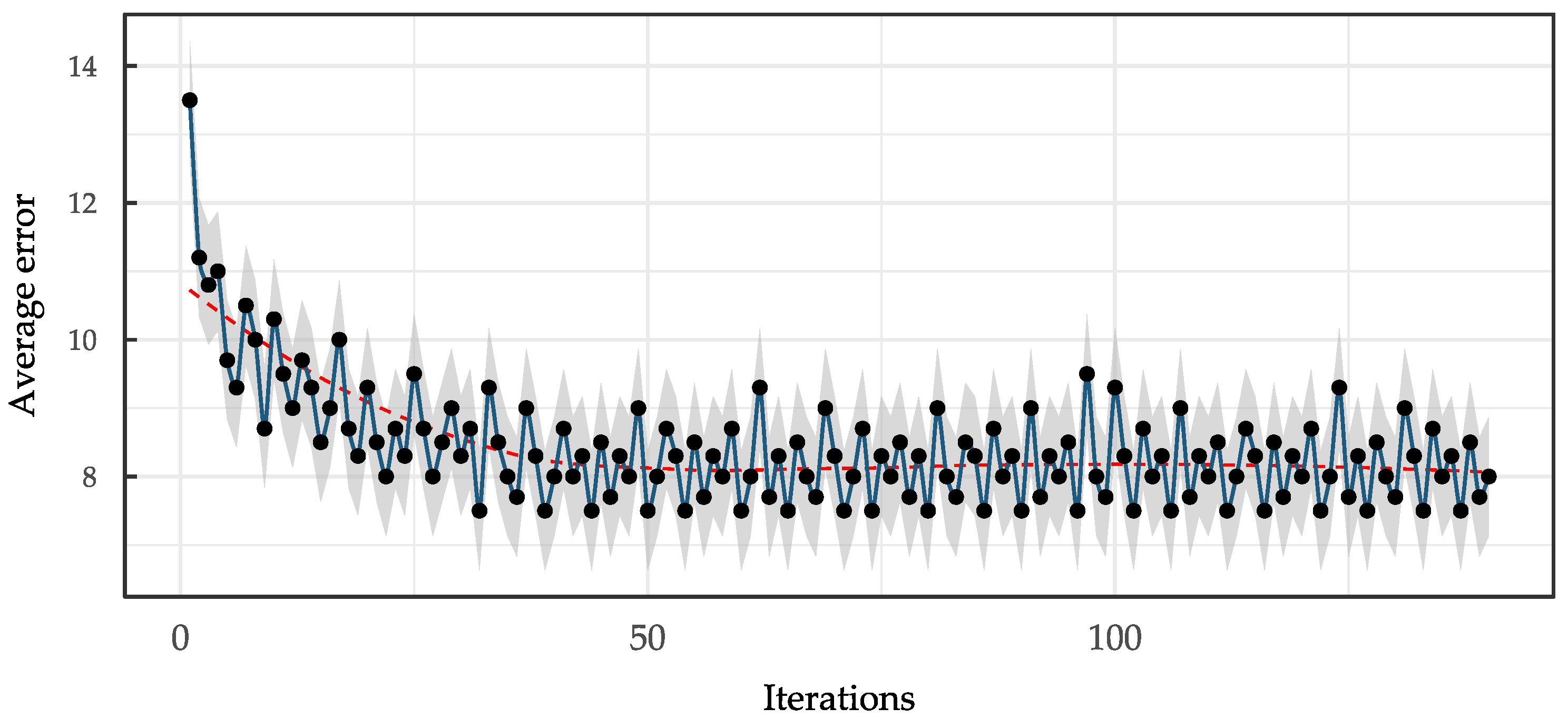

3.2. Object Detection Evaluation

Evaluating the fine-tuned YOLO architecture for obstacle detection in outdoor environments provided valuable insights into the model’s performance and practical application in visually impaired navigation systems. Eleven object classes were selected based on their prevalence as potential mobility obstacles in urban outdoor environments if their heights exceeding 25 centimeters, which could pose navigation hazards for visually impaired individuals. These classes include bicycle, bus, horse, car, cat, motorcycle, dog, person, train, poles, and stairs. These classes represent the objects most frequently encountered that could impede safe pedestrian movement.

Training was conducted over 150,000 iterations, with fine-tuning exclusively on the final four convolutional layers of the Darknet architecture. This process demonstrated convergence characteristics that justified the transfer learning approach. As shown in

Figure 8, the average training error decreased progressively to an almost stable value of 8. The most significant reduction occurred within the first 50,000 iterations, after which it stabilized. After 75,000 iterations, the convergence pattern exhibited minimal oscillation, indicating stable learning dynamics and successful knowledge transfer from the pre-trained weights. The model selected at iteration 99,000 achieved a margin of error of 0.730507%, which is substantially below the established threshold of 8%, confirming the reliability of the fine-tuning process.

Table 2 shows the overall confusion matrix obtained during the evaluation process, as well as the overall metrics summarizing the results for all classes.

A performance evaluation revealed a nuanced trade-off between the precision and recall metrics, highlighting the strengths and limitations of the fine-tuned approach. The system achieved an impressive precision rate of 95.00%, indicating that the vast majority of detected objects were correctly classified into one of the eleven defined classes. However, the recall rate of 33.19% revealed a significant limitation in the model’s ability to detect all relevant objects in the evaluation dataset. This disparity suggests that, while the system rarely produces false positives, it exhibits conservative detection behavior and may miss numerous obstacles that should be identified for safe navigation.

The mean average precision (mAP) analysis yielded a performance score of 68.20%, which is competitive with established detection systems but falls short of YOLO’s original benchmark of 73.40%. Individual class performance varied considerably. Traditional vehicle categories, such as cars and buses, achieved moderate success rates of 68.12% and 71.74%, respectively. However, animal classes presented particular challenges. The system completely failed to detect cats and horses during evaluation. This limitation can be attributed to the relative scarcity of animal instances in typical urban navigation scenarios and the difficulty of detecting these classes using image-based approaches alone without additional depth or contextual information. Performance metrics for each class are presented in

Table 3.

As summarized in

Table 3, the computational efficiency analysis demonstrated the practical viability of the system for real-time navigation applications. The average processing time is 42.49 ms per image, the system substantially exceeded the sub-second requirement established for navigation systems. This indicates that the fine-tuned model could effectively operate on the target hardware configuration. Probability distributions across detected classes revealed varying confidence levels. Dogs achieved the highest average confidence at 76.05%, followed by buses at 68.12% and cars at 63.48%. These variations in confidence reflect the model’s learned feature representations and the relative clarity of distinguishing characteristics within each object category.

A comparative analysis against established detection frameworks, including Fast R-CNN (68.4% mAP), Faster R-CNN (70.4% mAP), and the original YOLO (73.4% mAP), revealed that the fine-tuned model performs competitively while offering the distinct advantage of identifying specialized obstacle classes relevant to navigation assistance. The inclusion of poles and stairs, which are absent from standard detection datasets, is a notable contribution to assistive navigation technology despite their modest performance rates of 51.49% and 59.36%, respectively. These infrastructure elements are critical for navigation assistance for the visually impaired, as they represent common urban obstacles that standard object detection systems typically overlook.

Collectively, the results demonstrate that, although fine-tuning achieved reasonable detection performance for core navigation obstacles, the conservative detection behavior and class-specific limitations suggest that future implementations would benefit from training all network layers. This approach could improve recall performance while maintaining the precision standards necessary for reliable assistive navigation systems.

4. Discussion

This study presented an initial approach to assistive navigation for the visually impaired, integrating 3D audio processing and computer vision technologies. The research team developed and evaluated a functional prototype to explore the feasibility of combining these technologies for assistive applications in controlled environments. Experimental evaluations revealed promising preliminary results: Participants achieved an average collision rate of 0.5 and completed navigation scenarios in an average of 48 seconds. These outcomes demonstrated the system’s potential effectiveness; all participants successfully perceived spatial audio cues indicating nearby obstacles. Integrating stereoscopic cameras with real-time 3D audio generation via auralization techniques showed promise as a viable approach for providing intuitive navigation assistance.

The object detection component achieved notable performance metrics for this initial implementation: the fine-tuned YOLO architecture demonstrated 95.00% precision in obstacle classification. However, the recall rate of 33.19% indicated conservative detection behavior, representing a significant limitation requiring further development. This suggests that while the system rarely produced false positives, it frequently missed relevant obstacles. The mean average precision (mAP) of 68.20% falls short of the original YOLO benchmark of 73.40%, indicating room for improvement in future iterations. The computational efficiency analysis revealed that the system processed images at a rate of 42.49 ms, meeting real-time requirements for navigation applications.

Compared to related work, this study primarily contributed through integrating 3D audio spatialization with computer vision-based obstacle detection. Lucio Naranjo et al.’s theoretical framework [

17] focused on head-related impulse response (HRIR) interpolation using artificial neural networks and achieved a 60% improvement in computational efficiency. In contrast, the current research implemented a complete system with hardware deployment and user testing. However, it acknowledged limitations in detection performance. Katz et al.’s NAVIG system [

19] combined GPS positioning with 3D audio spatialization and achieved 78 ± 22% recognition rates in morphological earcon classification. This study explored an alternative approach, implementing real-time computer vision–based obstacle detection to reduce reliance on pre-existing infrastructure. However, this introduced challenges in detection reliability. EchoSee, presented by Schwartz et al. [

21], achieved a 39.8% reduction in collision avoidance performance using LiDAR-based 3D mesh reconstruction. Although the present research’s average collision rate of 0.5 per scenario is higher than EchoSee’s results, this initial prototype used more accessible technology with stereoscopic cameras. This represents a different technological approach with distinct trade-offs.

The smart cane system developed by Mai et al. [

20] incorporated 2D LiDAR and RGB-D cameras with SLAM algorithms, achieving 84.6% recognition accuracy for pedestrian crossings. This study examined a different configuration with a chest-mounted camera system and integrated 3D audio feedback. However, direct performance comparisons require further research in controlled studies. This initial prototype had two main limitations: the low recall rate and the inability to detect certain object categories, notably cats and horses, which indicated conservative detection behavior. Performance variations among participants highlighted the importance of individual anthropometric characteristics in spatial audio perception and indicated the need for personalized calibration procedures in future implementations. These limitations are being addressed in the ongoing development process.

Table 4 summarizes the advantages and limitations of this study and others like it.

This research advanced assistive navigation technology by demonstrating the feasibility of integrating affordable stereoscopic cameras with advanced computer vision algorithms and 3D audio processing. Future work will focus on improving recall performance by enhancing training datasets, implementing personalized audio calibration procedures, and investigating the integration of additional sensory modalities. The goal is to develop more robust navigation assistance systems for individuals who are visually impaired.

5. Conclusions

This research project successfully developed and evaluated an assistive navigation initial prototype for the visually impaired that integrated advanced 3D audio processing and computer vision technologies. The study demonstrated that this early implementation, which utilized a stereoscopic camera for depth perception, real-time auralization techniques, and convolutional neural network object detection, provided a promising foundation for intuitive navigation assistance. Experimental validation of the preliminary system revealed significant findings that advance the field of assistive technology and establish a solid framework for future development efforts. Remarkably, the prototype achieved computational efficiency by processing visual information in just 42.49 ms per image. This substantially exceeded the real-time requirements for navigation applications, confirming the system’s potential for practical deployment in more advanced iterations. Integrating segmented, convolutional 3D audio generation with head-related impulse response functions enabled users to perceive spatial obstacle information via directional sound cues. This eliminated the need for extensive training, demonstrating the viability of this approach for future enhancements. Studies evaluating user performance involving both visually impaired and blindfolded participants demonstrated measurable improvements in navigation. On average, there was a collision rate of 0.5 per scenario, and the average completion time was 48 seconds across diverse obstacle configurations. These results provide an encouraging baseline for ongoing research initiatives. The object detection component, based on a fine-tuned YOLO architecture, achieved a precision rate of 95.00% in obstacle classification. However, it exhibited conservative detection behavior, as reflected by its recall rate of 33.19%. This indicates clear opportunities for improvement in subsequent development phases. With a mean average precision of 68.20%, the component was competitive with established detection frameworks and offered specialized obstacle recognition capabilities relevant to navigation assistance. This laid the groundwork for enhanced performance in future iterations. The research contributions went beyond algorithmic optimization to include a fully functional initial prototype that was rigorously evaluated by actual users.

The experimental results conclusively demonstrated that affordable stereoscopic cameras, when combined with sophisticated computer vision algorithms and 3D audio processing, could effectively provide navigation assistance in this early implementation stage without relying on expensive LiDAR sensors or GPS infrastructure. The system’s ability to operate in GPS-denied environments while maintaining real-time performance characteristics establishes its potential for widespread deployment with continued refinement. The research validated that auralization techniques, specifically the application of segmented convolution with appropriate head-related transfer functions, could generate precise enough spatial audio cues to enable obstacle avoidance in complex navigation scenarios. This provides a robust foundation for advanced system development. Furthermore, integrating object classification capabilities enhances environmental awareness beyond simple obstacle detection by providing users with contextual information about their surroundings. This initial study confirmed that assistive technologies based on computer vision can achieve practical performance levels while maintaining the computational efficiency necessary for portable applications.

Author Contributions

Investigation, J.F.L.-N., D.S. and R.A.T.; conceptualization, J.F.L.-N., D.S., R.A.T., L.B; Methodology, E.P.H.-G., J.F.L.-N., D.S., and R.A.T.; supervision, E.P.H.-G., J.F.L.-N., D.S., R.A.T., and L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.P.H.-G., J.F.L.-N., D.S., and R.A.T.; writing—review and editing, E.P.H.-G., J.F.L.-N., D.S., R.A.T., and L.B.; funding acquisition, J.F.L.-N., and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Polytechnic School - EPN of Ecuador (

www.epn.edu.ec accessed on 28 May 2025).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the National Polytechnic School - EPN of Ecuador for their support in carrying out this research. Additionally, we extend our gratitude to people who participate in evaluating the prototype. Thanks for your time and predisposition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- D. D. Brilli, E. Georgaras, S. Tsilivaki, N. Melanitis, and K. Nikita, “AIris: An AI-Powered Wearable Assistive Device for the Visually Impaired,” in 2024 10th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference for Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), IEEE, Sep. 2024, pp. 1236–1241. [CrossRef]

- J. Redmon and A. Farhadi, “YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement,” arXiv:1804.02767 [cs.CV], Apr. 2018, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02767.

- Y. Zou, W. Chen, X. Wu, and Z. Liu, “Indoor localization and 3D scene reconstruction for mobile robots using the Microsoft Kinect sensor,” in IEEE 10th International Conference on Industrial Informatics, IEEE, Jul. 2012, pp. 1182–1187. [CrossRef]

- T. Gee, J. James, W. Van Der Mark, P. Delmas, and G. Gimel’farb, “Lidar guided stereo simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) for UAV outdoor 3-D scene reconstruction,” in 2016 International Conference on Image and Vision Computing New Zealand (IVCNZ), IEEE, Nov. 2016, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee, D. Har, and D. Kum, “Drone-Assisted Disaster Management: Finding Victims via Infrared Camera and Lidar Sensor Fusion,” in 2016 3rd Asia-Pacific World Congress on Computer Science and Engineering (APWC on CSE), IEEE, Dec. 2016, pp. 84–89. [CrossRef]

- D. Zermas, I. Izzat, and N. Papanikolopoulos, “Fast segmentation of 3D point clouds: A paradigm on LiDAR data for autonomous vehicle applications,” in 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), IEEE, May 2017, pp. 5067–5073. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, J. Wang, X. Wang, and Y. Zhang, “3D-LIDAR based branch estimation and intersection location for autonomous vehicles,” in 2017 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), IEEE, Jun. 2017, pp. 1440–1445. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, V. John, S. Mita, H. Tehrani, K. Ishimaru, and S. Nishino, “3D point cloud map based vehicle localization using stereo camera,” in 2017 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), IEEE, Jun. 2017, pp. 487–492. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim, B. Liu, and H. Myung, “Road-feature extraction using point cloud and 3D LiDAR sensor for vehicle localization,” in 2017 14th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots and Ambient Intelligence (URAI), IEEE, Jun. 2017, pp. 891–892. [CrossRef]

- S.-C. Yang and Y.-C. Fan, “3D Building Scene Reconstruction Based on 3D LiDAR Point Cloud,” in 2017 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics - Taiwan (ICCE-TW), IEEE, Jun. 2017, pp. 127–128. [CrossRef]

- A. Borcs, B. Nagy, and C. Benedek, “Instant Object Detection in Lidar Point Clouds,” IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett., vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 992–996, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Sanaguano-Moreno, J. F. Lucio-Naranjo, R. A. Tenenbaum, and G. B. Sampaio-Regattieri, “Rapid BRIR generation approach using Variational Auto-Encoders and LSTM neural networks,” Appl. Acoust., vol. 215, p. 109721, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. R. Begault, 3D Sound for Virtual Reality and Multimedia. Moffett Field, California: NASA Ames Research Center, 2000. [Online]. Available: https://human-factors.arc.nasa.gov/publications/Begault_2000_3d_Sound_Multimedia.pdf.

- F. Yao, W. Zhou, and H. Hu, “A Review of Vision-Based Assistive Systems for Visually Impaired People: Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions,” IEEE Trans. Human-Machine Syst., vol. 51, pp. 145–158, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Vorländer, Auralization. in RWTHedition. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. Blauert, Spatial Hearing. The MIT Press, 1996. [CrossRef]

- J. Lucio, R. Tenenbaum, H. Paz, L. Morales, and C. Iñiguez, “3D sound applied to the design of assisted navigation devices for the visually impaired,” Latin-American J. Comput., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 49–60, 2015, [Online]. Available: https://lajc.epn.edu.ec/index.php/LAJC/article/view/90.

- G. I. Okolo, T. Althobaiti, and N. Ramzan, “Assistive Systems for Visually Impaired Persons: Challenges and Opportunities for Navigation Assistance,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 11, p. 3572, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. F. G. Katz et al., “NAVIG: augmented reality guidance system for the visually impaired,” Virtual Real., vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 253–269, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Mai et al., “A Smart Cane Based on 2D LiDAR and RGB-D Camera Sensor-Realizing Navigation and Obstacle Recognition,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 3, p. 870, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. S. Schwartz, S. King, and T. Bell, “EchoSee: An Assistive Mobile Application for Real-Time 3D Environment Reconstruction and Sonification Supporting Enhanced Navigation for People with Vision Impairments,” Bioengineering, vol. 11, no. 8, p. 831, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Khan, A. Hussain, B. Khan, R. Nawaz, and T. Baker, “Novel Framework for Outdoor Mobility Assistance and Auditory Display for Visually Impaired People,” in 2019 12th International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering (DeSE), IEEE, Oct. 2019, pp. 984–989. [CrossRef]

- F. Ashiq et al., “CNN-Based Object Recognition and Tracking System to Assist Visually Impaired People,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 14819–14834, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Pardeshi, N. Wagh, K. Kharat, V. Pawar, and P. Yannawar, “A Novel Approach for Object Detection Using Optimized Convolutional Neural Network to Assist Visually Impaired People,” 2023, pp. 187–207. [CrossRef]

- G. Dimas, D. E. Diamantis, P. Kalozoumis, and D. K. Iakovidis, “Uncertainty-Aware Visual Perception System for Outdoor Navigation of the Visually Challenged,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 8, p. 2385, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Das, A. D. Das, and F. Sadaf, “Real-Time Wayfinding Assistant for Blind and Low-Vision Users,” Apr. 2025, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2504.20976. 2097.

- X. Zhang, X. Yao, L. Hui, F. Song, and F. Hu, “A Bibliometric Narrative Review on Modern Navigation Aids for People with Visual Impairment,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 16, p. 8795, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Real and A. Araujo, “Navigation Systems for the Blind and Visually Impaired: Past Work, Challenges, and Open Problems,” Sensors, vol. 19, no. 15, p. 3404, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Khan, S. Nazir, and H. U. Khan, “Analysis of Navigation Assistants for Blind and Visually Impaired People: A Systematic Review,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 26712–26734, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Theodorou, K. Tsiligkos, and A. Meliones, “Multi-Sensor Data Fusion Solutions for Blind and Visually Impaired: Research and Commercial Navigation Applications for Indoor and Outdoor Spaces,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 12, p. 5411, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Corke, W. Jachimczyk, and R. Pillat, Robotics, Vision and Control, vol. 147. in Springer Tracts in Advanced Robotics, vol. 147. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Rusu and S. Cousins, “3D is here: Point Cloud Library (PCL),” in 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, IEEE, May 2011, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- D. Scharstein, R. Szeliski, and R. Zabih, “A taxonomy and evaluation of dense two-frame stereo correspondence algorithms,” in Proceedings IEEE Workshop on Stereo and Multi-Baseline Vision (SMBV 2001), IEEE Comput. Soc, 2002, pp. 131–140. [CrossRef]

- V. R. Algazi, R. O. Duda, D. M. Thompson, and C. Avendano, “The CIPIC HRTF database,” in Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Workshop on the Applications of Signal Processing to Audio and Acoustics (Cat. No.01TH8575), IEEE, pp. 99–102. [CrossRef]

- M. Everingham, L. Van Gool, C. K. I. Williams, J. Winn, and A. Zisserman, “The Pascal Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge,” Int. J. Comput. Vis., vol. 88, no. 2, pp. 303–338, Jun. 2010. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).