1. Introduction

Xenotransplantation, using genetically modified pigs, offers a promising solution to the shortage of allogeneic donor organs. Preclinical trials have demonstrated long survival times in non-human primates transplanted with hearts and kidneys from genetically modified pigs [

1]. Moreover, the first transplantations of pig organs into human patients and brain-dead individuals indicate that this emerging technology is steadily progressing toward clinical application. Genetically modified pigs are needed to prevent hyperacute, antibody-mediated and cellular rejection as well as to preserve coagulation [

2]. Furthermore, it is essential to prevent transmission of potentially zoonotic or xenozoonotic porcine microorganisms to the recipient [

3,

4]. The transmission of the porcine cytomegalovirus/porcine roseolovirus (PCMV/PRV) to the first human patient who received a pig heart in Baltimore, which contributed to the death of the patient [

5], indicates the importance of preventing such transmissions. Whereas PCMV/PRV and many other porcine viruses can be eliminated by selection of virus-negative animals, early weaning, colostrum deprivation, treatment with antiviral drugs or vaccines if available, porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERVs) cannot. The proviruses are integrated with up to 60 copies in the genome of all pigs.

PERV-A and PERV-B are present in all pigs, whereas PERV-C is not found in all pigs [

6,

7]. While PERV-A and PERV-B have been shown to infect human cells under

in vitro conditions, PERV-C is an ecotropic virus that infects only pig cells. Recombination between PERV-C and PERV-A results in recombinant viruses with a high replication rate and the capacity to infect human cell [

8]. To date, there is no evidence of transmission of these viruses in either preclinical studies or first human xenotransplantations (for review see [

9]). Despite this, various strategies have been developed to prevent PERV transmissions. First of all, the selection of PERV-C-negative animals to prevent PERV-A/C recombination. This strategy was used when PERV-C-free Auckland Island pigs were selected [

10]. Auckland Island pigs represent an inbred population of feral pigs isolated on the sub-Antarctic island for over 100 years. The animals have been maintained under pathogen-free conditions in New Zealand; they are virologically well characterized and have been used as donor sources in first clinical trials of porcine neonatal islet cell transplantation for the treatment of human diabetes patients. In the first clinical trials, no porcine viruses, including PERVs were transmitted to the human recipients. Auckland Island pig kidney cells (selected to be free of PERV-C) were imported from New Zealand, and founder animals were established by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU) [

11].

Another strategy is based on RNA interference. PERV-specific small hairpin (sh) RNA directed against sequences in the polymerase gene (pol) were expressed in pig cells

in vitro and in transgenic animals

in vivo and reduced the PERV expression [

12,

13,

14]. Although gene editing by zinc finger nucleases (ZFN) did not succeed [

15], using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) resulted in the inactivation of all PERV proviruses

in vitro [

16] and

in vivo [

17].

Another promising strategy is the generation of vaccines against PERVs in order to protect the recipient. Vaccines against the murine leukemia virus (MuLV) and the feline leukemia virus (FeLV), two gammaretroviruses closely related to PERV, were able to prevent leukemia in mice [

18] and cats [

19], respectively. 10µg of the surface envelope protein gp70 of the Friend-MuLV coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin by glutaraldehyde protected more than 90% of the mice from erythroleukemia [

18]. Live and inactivated vaccines against FeLV were found efficacious in reducing clinical signs in cats [

19].

In previous immunization studies using recombinant p15E and gp70 of PERV, binding and neutralizing antibodies were induced in different species [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. In those studies, however, Freund’s adjuvant was applied, which is not suitable for use in humans. To extend these findings, we immunized rats with newly produced and purified recombinant p15E and gp70 in combination with a type of adjuvant approved for human use. AddaVax was employed, a squalene-based oil-in-water nano-emulsion similar to MF59 that has been licensed for use in adjuvanted influenza vaccines [

25]. In addition, a modified neutralization assay and a novel method for epitope mapping were applied.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rats, Normal Rat Sera and Cells

Wistar rats were maintained and immunized by the Davids Biotechnologie GmbH (Regensburg, Germany). Five rats were immunized with the transmembrane envelope protein p15E, five rats with the surface envelope protein gp70. Additional normal Wistar rat sera were obtained from the Institute for Animal Welfare, Animal Behavior and Laboratory Animal Science, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Free University Berlin.

Human embryonic kidneys 293T(293T) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) supplemented with 10 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, PAN-Biotech, Germany) Penicillin and streptomycin were not added to the culture medium.

2.2. Cloning, Expression and Purification of the Recombinant Proteins

Two antigens were prepared and used for screening assays and immunization: the recombinant transmembrane envelope protein p15E and recombinant surface envelope protein the gp70 (

Figure 1).

The ectodomain sequence of p15E (amino acids 447-477, accession numberHQ688786) was cloned into the pCal-n vector (Stratagene Europe, Amsterdam, Netherlands) [

20]. The recombinant plasmid was transferred to

Escherichia coli DH5α (

E. coli DH5α) competent cells. Single colonies were selected for sequencing, then the recombinant p15E was expressed in

E. coli BL21 DE3 and induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at OD

600 of 0.6. After incubation for 3 h at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 x g for 30 min, at 4 °C using a Sorvall RC 6 Plus Superspeed Centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Cells were lysed by incubation in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl

2 and 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), supplemented with 1 mg/mL lysozyme, 1000 U benzonase (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and cOmplete ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the lysate was subjected to 20 s sonification cycles with 1 min cooling on ice. The suspension was diluted in a 1:1 ratio with binding buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl

2) and centrifuged at 50,000 x g for 20 min; supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm filter using. The protein was purified by calmodulin resin affinity chromatography using an ÄKTAprime plus system (both from Cytiva Life Sciences, Freiburg, Germany) with 5 mM DTT included in binding buffer and 2 mM DTT in the washing (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl

2) and elution buffers (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA).

The entire sequence of the surface envelope protein gp70 of PERV-A (amino acids 34-146, accession number Q688785) and a short stretch of the ectodomain sequence of p15E were cloned into pET22b (+) vector (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) [

21]. The p15E sequence was included to make the antigen similar to the sequence of the recombinant gp70/p15E of FeLV successfully used as Leucogen to vaccinate cats [

25]. The pET22b (+)-gp70 was transferred into

E. coli DH5α competent cells. Confirmative sequencing was performed after single-colony selection. The recombinant protein was expressed in

E. coli BL21 DE3 cells and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG in LB medium at an OD

600 of 0.6. After incubation for 3 h at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm, cells were harvested as mentioned above.

E. coli DH5α and BL21 strains were grown on LB agar or in LB medium with ampicillin (100 µg/mL) as the selective antibiotic [

21]. Cells were lysed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) with 10 mM DTT, supplemented with 1 mg/mL lysozyme by 20 s sonification cycles with 1 min intervals on ice. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 22,000 x g for 30 min at 4 °C and the insoluble pellet was lysed by incubation in lysis buffer (pH 8.0) (100 mM NaH

2PO4, 10 mM Tris/HCl 6 M GuHCl and 10 mM DTT, supplemented with 3 U/µL benzonase) overnight at 4 °C. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µM filter. Purification was performed by Ni-NTA resin affinity chromatography (Cytiva Life Sciences, Freiburg, Germany) using an ÄKTAprime plus system with 5 mM DTT included in binding (pH 8.0), two washing (pH 6.3 and pH5.0) and elution buffers (pH 4.5) (100 mM NaH

2PO

4, 10 mM Tris/HCl, 8 M urea). Purified recombinant gp70 was concentrated to 1mg/mL using Vivaspin 15R Centrifugal Concentrator (Vivaproducts, Littleton, USA) and subsequently dialyzed against PBS using dialysis cassettes (15 ml, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Recombinant proteins were characterized by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting.

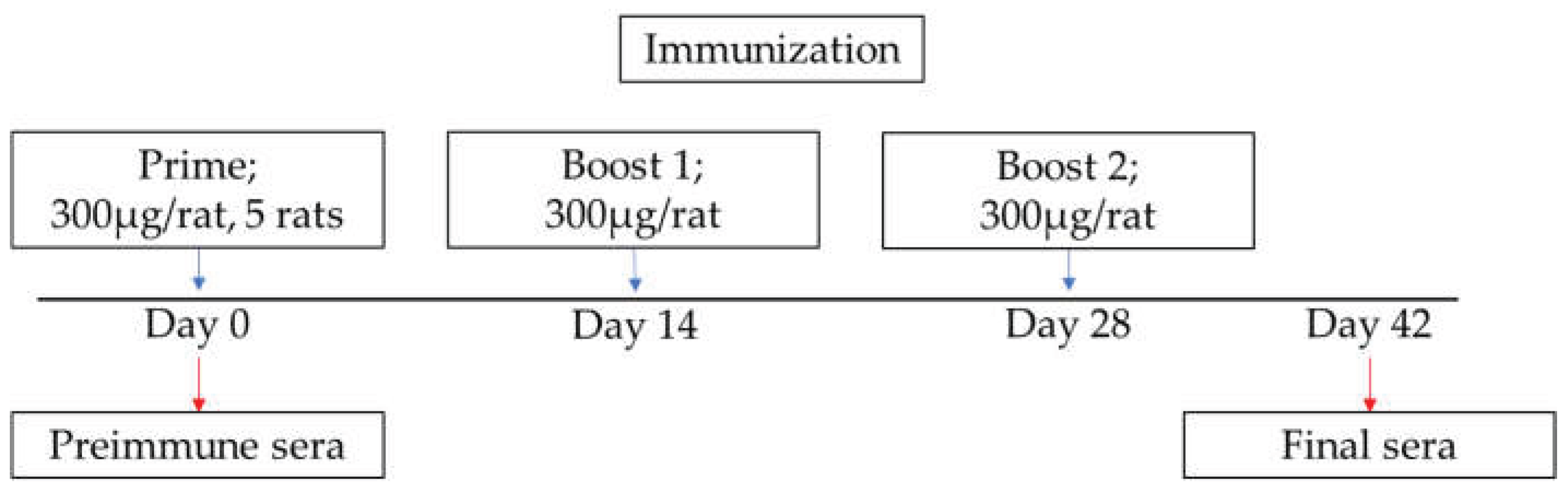

2.3. Immunization Schedule

Wistar rats (n=5 per group) were immunized with 300 µg of recombinant p15E or gp70 emulsified in AddaVax (InvivoGen, Toulouse, France) for the primary immunization, followed by two booster injections of the same dose emulsified in the same adjuvant on days 14 and 28. Preimmune sera were collected one day before immunization and immune sera were collected on days 14, 28, and 42 after the first immunization. The animal experiments were conducted by Davids Biotechnologie GmbH (Regensburg, Germany).

2.4. SDS-PAGE

Protein expressions and purifications were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, which was performed using a 17 % separating gel for p15E and a 12 % separating gel for gp70. 1 µg p15E and 100 nggp70 were mixed with 6 × SDS-PAGE loading buffer and denatured at 95 °C for 10 min in a metal heating block (Eppendorf Vertrieb Deutschland GmbH, Wesseling-Berzdorf, Germany). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained by Imperial Protein Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature and destained with double-distilled water (ddH2O) until background was clear.

2.5. Western Blotting

SDS-PAGE was performed as described above. The proteins were transferred onto 0.2 µm PVDF membranes (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) using a semi-dry transfer system (Peqlab Biotechnologie GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) at a constant current of 0.13 A for 70 min. The blot was blocked with 5 % (w/v) non-fat dry milk (NFDM) powder in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05 % Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated with positive control sera (goat sera anti-p15E, #355 and anti-gp70, #62 [

21]), rat anti-p15E (1:1000) or rat anti-gp70 (1:1000) overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (1:20,000) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG(H+L) secondary antibody (1:10,000) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed three times for 10 min with TBST between each incubation step. Blots were developed with ECL Prime Western Blot Detection Reagent (Cytiva, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.6. In Vitro Neutralization Assays

293T cells cultured in DMEM supplemented with heat inactivated 10 % FBS at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator were used for neutralization assays. Rat anti-p15E and anti-gp70 sera were heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min and serially diluted twofold in DMEM. 20 µL undiluted or serially diluted sera and 80 µL PERV supernatant (threshold cycle (Ct) <25) were mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. The mixture was added to 100 µL HEK 293T cells (5,000 cells/ 100 µL) in 96-well plates and incubated for 96 h. Lysis duplex real-time polymerase chain (real-time PCR) reaction detecting both, PERV-pol and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was performed in situ. Direct PCR Lysis Reagent (Cell) (Viagen Biotech, Los Angeles, CAa, USA) and Nuclease-Free water were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and Proteinase K (Viagen Biotech, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was added at 40 µL per 1 mL of the resulting mixture. This mixture was applied to lyse cells in situ, adding 60 µL per well. The cell lysates were incubated overnight at 55 °C for lysis and wrapped in damp paper towels to prevent evaporation, followed by heat inactivation of proteinase K at 85 °C for 1.5 h. The resulting products were used directly for real-time PCR analysis.

2.7. Duplex Real-Time PCR for the Detection of Provirus

To determine the provirus in 293T cells, a duplex real-time PCR was performed. Genomic DNA was extracted using the method described above. Real-time PCR reactions were carried out using SensiFAST Probe No-ROX kit (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, OH, USA), specific primers and probes (

Table 1) on a qTOWER

3G qPCR cycler (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany). The cycling conditions used were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 45 amplification cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 62 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s.

2.8. Epitope Mapping

The ectodomain of PERV p15E (EPISLTLAVMLGLGVAAGVGTGTAALITGPQQLEKGLGEHAAMTEDLRLEESVSNLEESLTSLSEVVLQNRRGLDLLFLREGLCAALKEECCFYVDHSGAIRDSMSKLRERLERRRRREADQGWFENRSPWMTTLLSALTGPLVVLLLLLT) was synthesized as 74 peptides of 13-mers overlapping by 11 amino acids (JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany) (

Supplementary Table 1). N-terminal acetylation of the peptides makes the peptides more stable against N-terminal degradation, and the uncharged N-acetyl group corresponds more closely to the structure of the native antigen than a charged NH

3+ group.

Peptides were covalently immobilized on the glass surface. An optimized hydrophilic linker moiety is inserted between the glass surface and the antigen derived peptide sequence to avoid false negatives caused by steric hindrances. For technical reasons all peptides contain a C-terminal glycine.

The profiling experiment was performed with a total of five rat serum samples diluted to 1:40, 1:200 and 1:1000 with blocking buffer and incubated for 1 hour at 30 °C on the Multiwell microarray slide. Each slide contained 21 individual mini-arrays (1 mini-array per sample dilution).

Subsequent to sample incubation, a secondary, fluorescently labeled anti-rat-IgG antibody, at 0.1 μg/ml, was added into the corresponding wells and left to react for 1 hour.

Additional control incubations applying the secondary antibody only (but no rat serum sample) were performed in parallel on the same microarray slide to assess false positive binding of the secondary antibody to peptides.

Serum samples were diluted in blocking buffer (Pierce International, Superblock TBS T20) and applied to microarrays for 1 h at 30 °C, then they were incubated with secondary antibody diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h at 30 °C. Secondary antibody used for detection: Anti-rat IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, Ely, United Kingdom), label Cy5, applied concentration 0.1 μg/ml. Before each incubation step, microarrays were washed with washing buffer (50 mM TBS-buffer including 0.1 % Tween-20, pH 7.2). Finally, the microarrays were dried.

After washing and drying, the microarrays were scanned using a high-resolution fluorescence scanner (Axon Genepix Scanner 4300 SL50) at 635 nm to obtain fluorescence intensity profiles. Laser settings and applied resolution were identical for all measurements. The resulting images were analyzed und quantified using spot-recognition software GenePix (Molecular Devices). For each spot, the mean signal intensity was extracted (between 0 and 65535 arbitrary units).

For further data evaluation, the so called MMC2 values were determined. The MMC2 equals the mean value of all three instances on the microarray except when the coefficient of variation (CV) – standard-deviation divided by the mean value – is larger 0.5. In this case the mean of the two closest values (MC2) is assigned to MMC2.

4. Discussion

Immunization of rats with recombinant PERV p15E and PERV gp70 induced neutralizing antibodies, indicating that these envelope proteins may serve as effective antigens in vaccines designed to protect against PERV infection.

These findings are consistent with previous studies in which goats, rats, mice, and guinea pigs were immunized with both proteins, despite several differences between those studies and the present immunization approach.

Previously, goats were immunized with 500 µg antigen, Wistar rats with 150 µg, Balb/c mice with 50 µg, and Guinea pigs with 200 µg antigen [

20,

21]. In this study, we increased the antigen dose to 300 µg in order to achieve improved immunization outcomes in Wistar rats. The immunization schedule was also different. In previous studies a second and third immunization was performed after 2 and 5 weeks, here booster immunizations were performed after 14 and 28 days (

Figure 4). The main difference is the usage of a different adjuvant. In previous studies complete Freund´s adjuvant (CFA) was used for immunization and incomplete Freund´s adjuvant (IFA) for booster immunizations [

20,

21]. CFA is composed of mineral oil (paraffin oil and mannide monooleate) and inactivated and dried mycobacteria (

M. tuberculosis). CFA contains trehalose 6,6’ dimycolate, which stimulates the macrophage inducible Ca

2+-dependent lectin receptor (Mincle). Additionally, CFA has ligands for toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, and TLR9. IFA lacks the mycobacterial components. CFA cannot be used in humans because it causes severe side effects, it triggers strong and long-lasting inflammatory reactions, and can lead to abscesses, ulcerations, necrosis, and chronic granulomas at the injection site. Therefore, we tested AddaVax, which is a squalene-based oil-in-water nano-emulsion. Its formulation is similar to that of MF59 that has been licensed in Europe for adjuvanted flu vaccines [

25]. Squalene is an oil more readily metabolized than the paraffin oil used in Freund’s adjuvants. This class of adjuvants is believed to act through recruitment and activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and stimulation of cytokines and chemokines production by macrophages and granulocytes [

25].

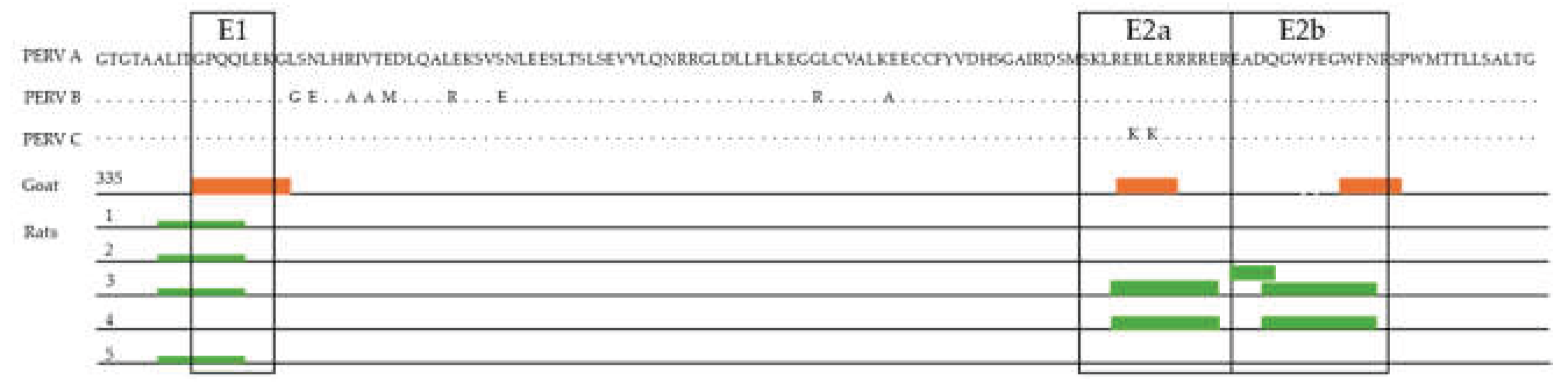

Immunization with AddaVax induced neutralizing antibodies, and in the case of sera against p15E, the antibodies recognized epitopes similar to those reported in previous studies using CFA/IFA (

Figure 9). Previously, epitope mapping was carried out using a cellulose-adsorbed peptide spot library consisting of 15-mer peptides overlapping by 12 amino acids, with detection performed by chemiluminescence [

20,

21]. In the present study, a library of 74 peptides composed of 13-mers overlapping by 11 amino acids was employed. Shorter peptides are expected to allow more precise fine mapping of the epitopes. All peptides were covalently immobilized on a glass surface, and epitope detection was performed using a fluorescently labeled anti-rat IgG antibody in combination with a high-resolution fluorescence scanner. The epitopes identified by both approaches were highly similar (

Figure 9).

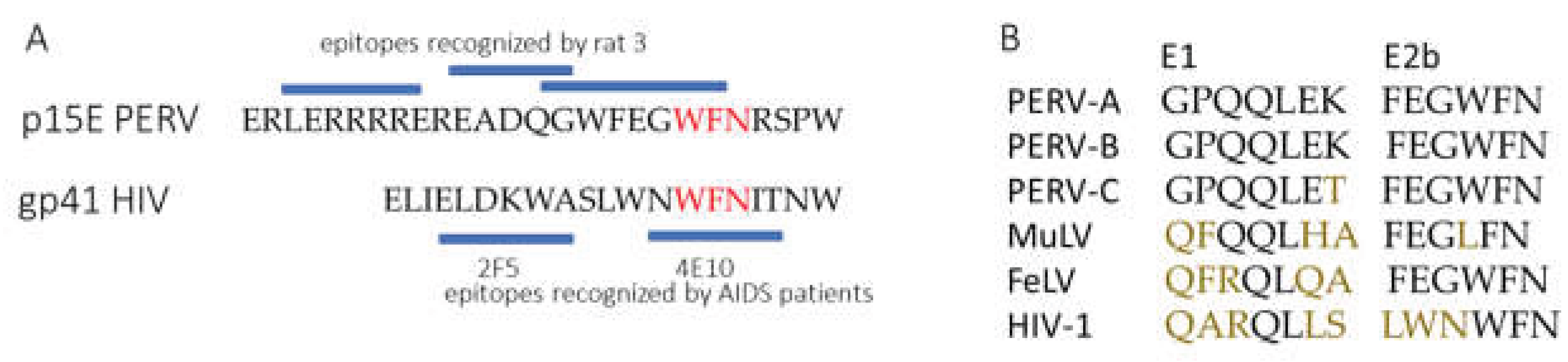

It is of great interest that the main epitope in the MPER of p15E shows a sequence homology with an epitope in gp41 of HIV-1, which is recognized by a broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody, 4E10, isolated from an AIDS patient [

29] (

Figure 10). 4E10 neutralizes diverse subtypes of HIV-1 (e.g., subtypes B, C, and E) [

29]. Not surprisingly, similar epitopes were also found when cats were immunized with p15E of FeLV [

30].

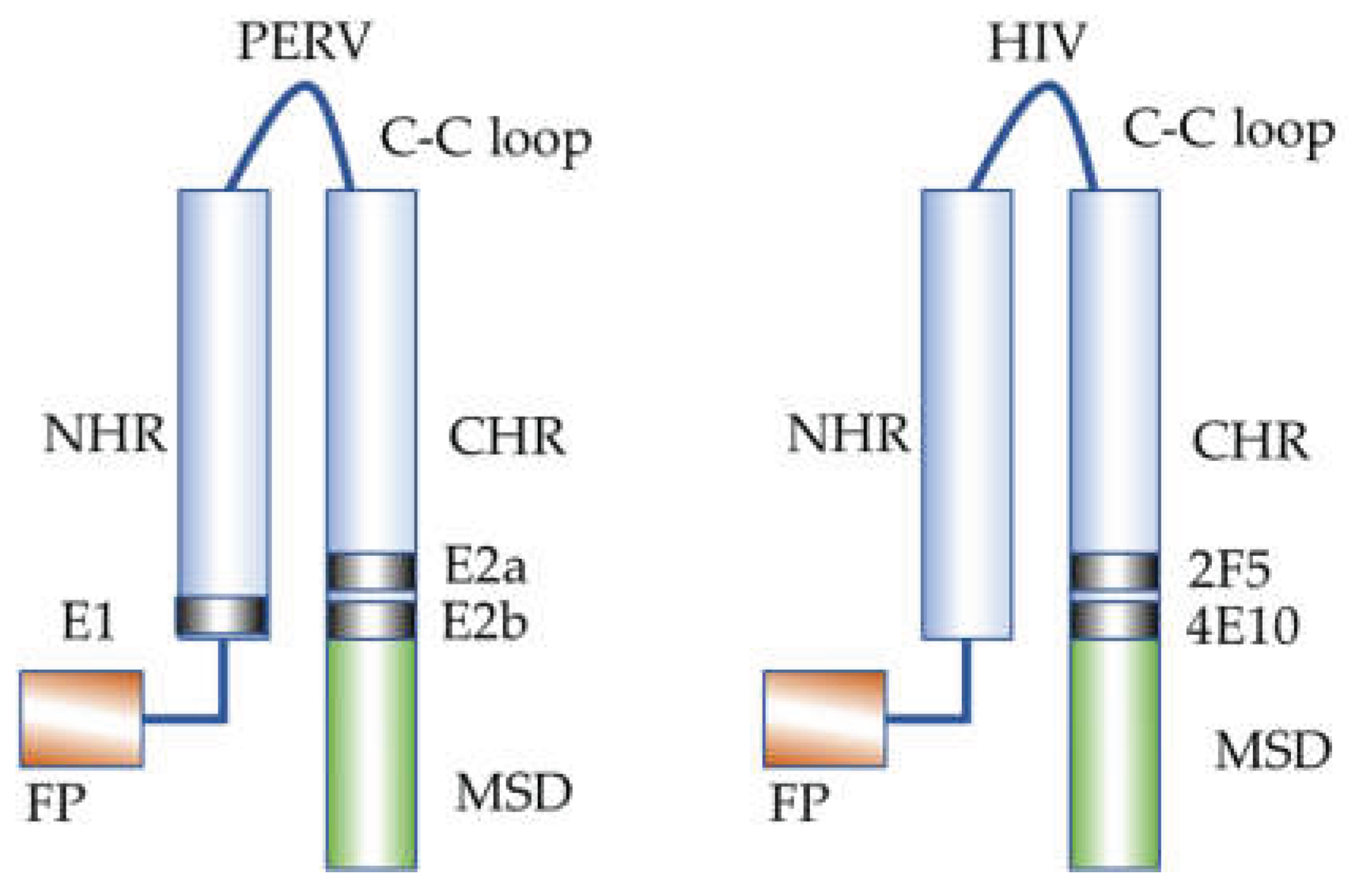

It is not only the partial sequence homology between the epitopes in the gammaretroviruses PERV and FeLV on the one hand and HIV-1 on the other hand, but also the localization of these epitopes in the MPER (

Figure 11), what is important for the understanding of the function of this domain. In more recent studies with HIV-1 it has been demonstrated that the MPER is important for env-mediated fusion and virus infectivity [

31,

32]: mutations to Ala of three of five conserved Trp residues in this region are sufficient to abrogate syncytium formation [

32]. In contrast to our success in inducing antibodies against the MPER of PERV (and FeLV), numerous attempts to induce antibodies of the type 2F5 and 4E10, broadly neutralizing HIV-1, failed [

33,

34,

35]. Immunization experiment using the backbone of p15E of PERV in which the epitopes in the FPPR and MPER were substituted by the corresponding epitopes of 2F5 and 4E10 induced binding antibodies against the HIV epitopes, but despite the exact recognition of the 2F5 epitope, no or very weak neutralization of HIV-1NL4-3 by the immune sera was demonstrated [

36].

In immunization studies using subunits of p15E, i.e., recombinant proteins corresponding to the N-terminal, the C-terminal helical region (NHR, CHR) and a p15E with a mutation in the Cys–Cys loop, no MPER-specific neutralizing antibodies were induced, indicating that the Cys-Cys loop is important [

24]. However, when the animals were immunized with the FPPR/NHR subunit or the mutated p15E alone, novel neutralizing antibodies binding to the NHR were found. The epitope was IVTEDLQALEKS, and was localized in the NHR at a position where in gp41 of HIV-1 the neutralizing antibodies D5 and HK20 are binding [

37,

38,

39]. Such antibodies were not detected in this immunization study.

Since no animal models are available to study the efficacy of PERV-neutralizing antibodies

in vivo, we immunized cats with the corresponding p15E protein of FeLV. This approach induced neutralizing antibodies that bound to epitopes similar to those recognized in PERV p15E [

30]. Upon challenge with infectious FeLV, the immunized cats were protected from leukemia [

40], demonstrating that these antibodies are capable of neutralizing the virus

in vivo.

Because immunization of different animal species with PERV p15E and gp70 consistently elicited neutralizing antibodies targeting identical epitopes critical for the infection process, it is reasonable to suggest that similar protective antibodies could also be induced in non-human primates and humans.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, J.D.; methodology, J.B., J.D., L.K.; validation, J.B., J.D., L.K.; formal analysis, J.B., J.D., L.K.; investigation, J.B., J.D., L.K.; resources, J.D.; data curation, J.B., J.D., L.K., B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D., J.B.; writing—review and editing, J.B., J.D., L.K., B.K.; supervision, J.D.; project administration, J.D.; funding acquisition, J.D., B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the recombinant envelope proteins used for immunization. (a), recombinant gp70 protein with pelB leader sequence, partial sequence of p15E and His-tag; (b), recombinant p15E protein with calmodulin binding protein (CBP). PCS, protease cleavage site, numbering according accession number AJ133817.

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the recombinant envelope proteins used for immunization. (a), recombinant gp70 protein with pelB leader sequence, partial sequence of p15E and His-tag; (b), recombinant p15E protein with calmodulin binding protein (CBP). PCS, protease cleavage site, numbering according accession number AJ133817.

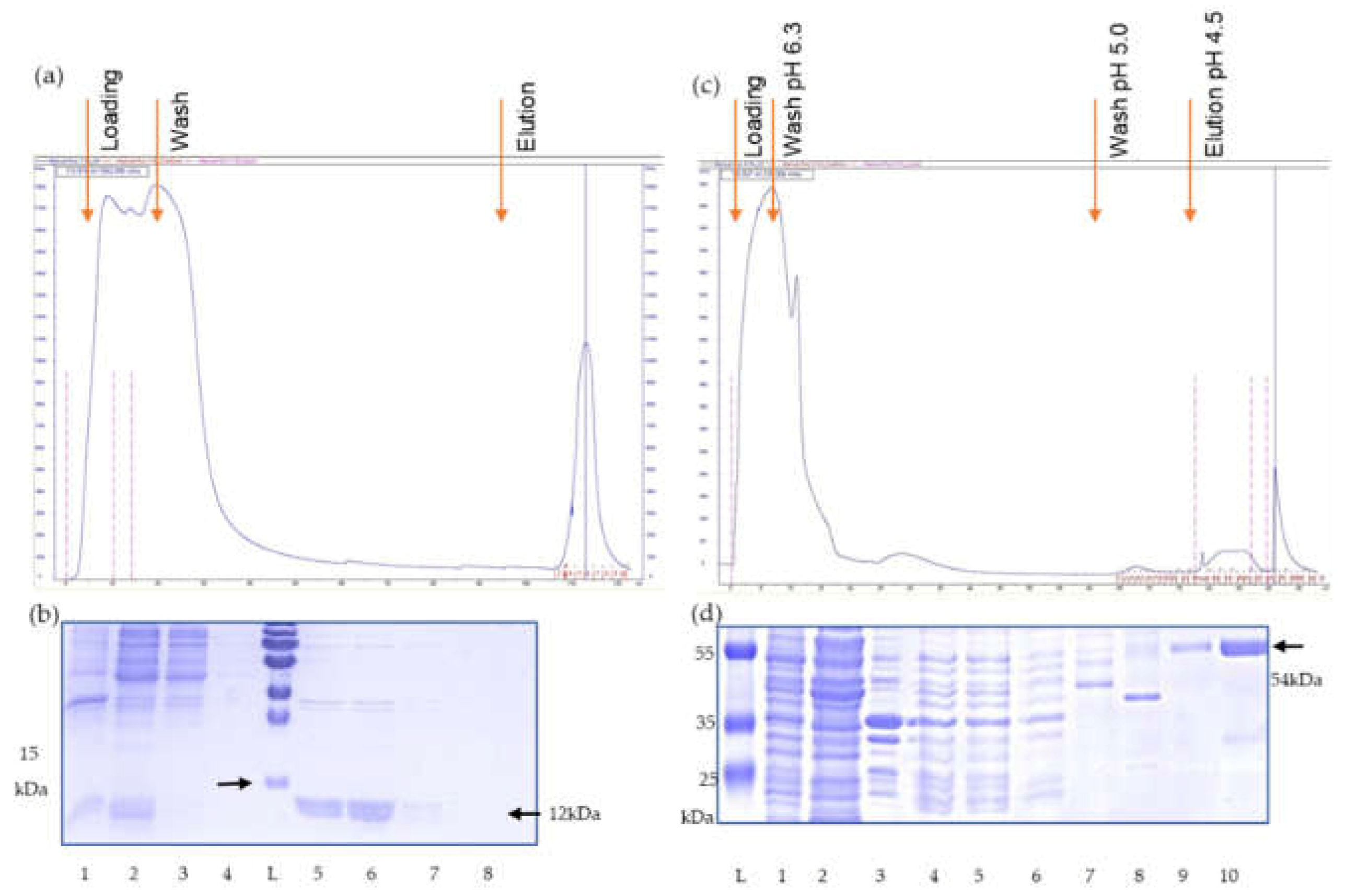

Figure 2.

(a) Elution profile of the calmodulin binding protein (CBP) affinity chromatography of recombinant p15E. (b) Coomassie blue staining of SDS-PAGE of fractions of the elution process L, protein ladder, 1, lysed cells, 2, supernatant, 3, flow through, 4, wash fraction, 5-9, elution fractions, i.e., recombinant p15E (12 kDa) protein purified by affinity chromatography. (c) Elution profile of the His tag affinity chromatography of recombinant gp70. (d) Coomassie blue staining of the SDS-PAGE of fractions of the elution process. L, protein ladder, 1, lysed cells, 2, soluble fraction, 3, insoluble fraction, 4, 5, cleared lysate filtered by 0.45µM filter, 6, flow through, 7, wash fraction, pH 6.3, 8 wash fraction at pH 5.0, 9, 10, elution fractions at pH 4.5, i.e., recombinant gp70 (54 kDa) purified by affinity chromatography.

Figure 2.

(a) Elution profile of the calmodulin binding protein (CBP) affinity chromatography of recombinant p15E. (b) Coomassie blue staining of SDS-PAGE of fractions of the elution process L, protein ladder, 1, lysed cells, 2, supernatant, 3, flow through, 4, wash fraction, 5-9, elution fractions, i.e., recombinant p15E (12 kDa) protein purified by affinity chromatography. (c) Elution profile of the His tag affinity chromatography of recombinant gp70. (d) Coomassie blue staining of the SDS-PAGE of fractions of the elution process. L, protein ladder, 1, lysed cells, 2, soluble fraction, 3, insoluble fraction, 4, 5, cleared lysate filtered by 0.45µM filter, 6, flow through, 7, wash fraction, pH 6.3, 8 wash fraction at pH 5.0, 9, 10, elution fractions at pH 4.5, i.e., recombinant gp70 (54 kDa) purified by affinity chromatography.

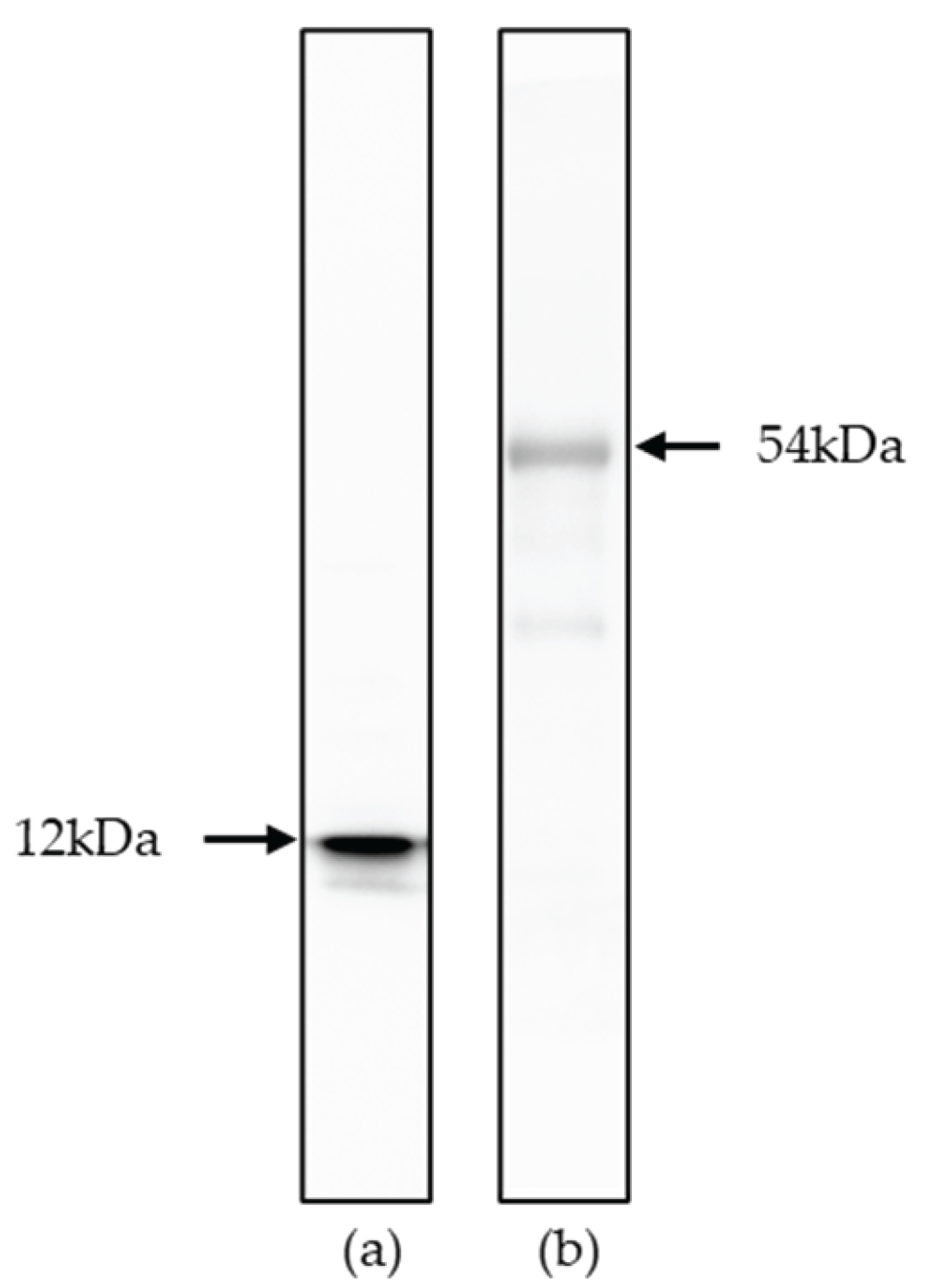

Figure 3.

(a) Western blot analysis of recombinant p15E (12 kDa) protein. Goat anti-p15E serum (1:1000) was used as primary antibody, donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (1:20,000) as secondary antibody; (b) Western blot analysis of recombinant gp70 (54 kDa) protein. Goat anti-gp70 serum (1:1000) was used as primary antibody, donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (1:20,000) as secondary antibody.

Figure 3.

(a) Western blot analysis of recombinant p15E (12 kDa) protein. Goat anti-p15E serum (1:1000) was used as primary antibody, donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (1:20,000) as secondary antibody; (b) Western blot analysis of recombinant gp70 (54 kDa) protein. Goat anti-gp70 serum (1:1000) was used as primary antibody, donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (1:20,000) as secondary antibody.

Figure 4.

Scheme of immunization and sample collection. Wistar rats were immunized with 300 µg purified p15E or gp70 protein mixed with the adjuvant AddaVax per rat for the primary immunization and followed by two boosts. Preimmune sera were collected before the immunization. On day 42 final sera were collected.

Figure 4.

Scheme of immunization and sample collection. Wistar rats were immunized with 300 µg purified p15E or gp70 protein mixed with the adjuvant AddaVax per rat for the primary immunization and followed by two boosts. Preimmune sera were collected before the immunization. On day 42 final sera were collected.

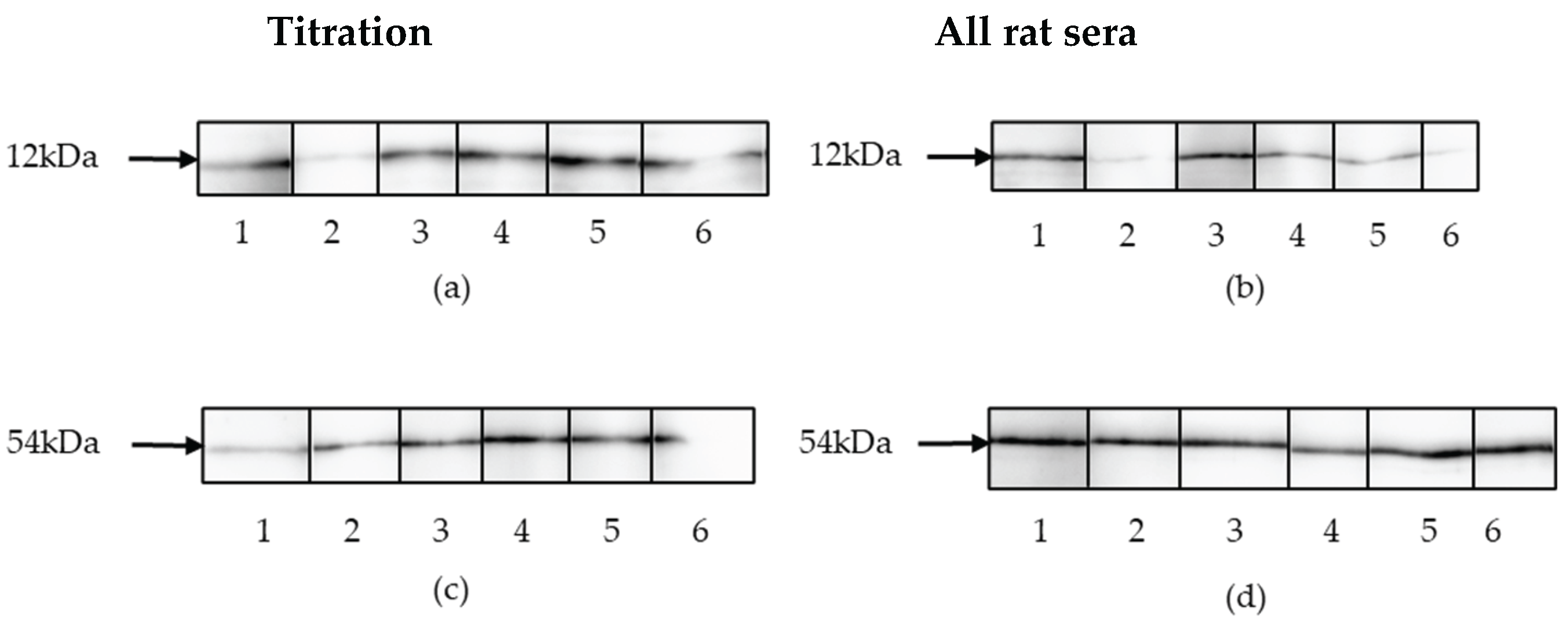

Figure 5.

Results of the Western blot analysis. (a) Titration of rat serum 1 against p15E using purified recombinant p15E protein as antigen. 1, goat serum against p15E, followed by dilutions of the rat serum 2, 1:100; 3, 1:200; 4, 1:500; 6, 1:1000; 6, 1:10,000. (b) Western blot analysis of 5 rat sera anti-p15E using purified recombinant p15E protein as antigen. 1, goat serum against p15E; 2, rat serum 1; 3, rat serum 2; 4, rat serum 3; 5, rat serum 4; 6, rat serum 5; -all at dilution 1:10,00. (c) Titration of rat serum 1 against gp70 using purified recombinant gp70 protein as antigen. 1, goat sera anti-gp70; followed by dilutions of the rat sera 2, 1:100; 3, 1:200; 4, 1:500; 5, 1:1000; 6, 1:10,000. (d) Western blot analysis of rat sera anti-gp70 using purified recombinant gp70 protein as antigen. 1, goat sera against gp70; 2, rat serum 1; 3, rat serum 2; 4, rats serum 3; 5, rat serum 4; 6, rat serum 5, all at dilution 1:1000.

Figure 5.

Results of the Western blot analysis. (a) Titration of rat serum 1 against p15E using purified recombinant p15E protein as antigen. 1, goat serum against p15E, followed by dilutions of the rat serum 2, 1:100; 3, 1:200; 4, 1:500; 6, 1:1000; 6, 1:10,000. (b) Western blot analysis of 5 rat sera anti-p15E using purified recombinant p15E protein as antigen. 1, goat serum against p15E; 2, rat serum 1; 3, rat serum 2; 4, rat serum 3; 5, rat serum 4; 6, rat serum 5; -all at dilution 1:10,00. (c) Titration of rat serum 1 against gp70 using purified recombinant gp70 protein as antigen. 1, goat sera anti-gp70; followed by dilutions of the rat sera 2, 1:100; 3, 1:200; 4, 1:500; 5, 1:1000; 6, 1:10,000. (d) Western blot analysis of rat sera anti-gp70 using purified recombinant gp70 protein as antigen. 1, goat sera against gp70; 2, rat serum 1; 3, rat serum 2; 4, rats serum 3; 5, rat serum 4; 6, rat serum 5, all at dilution 1:1000.

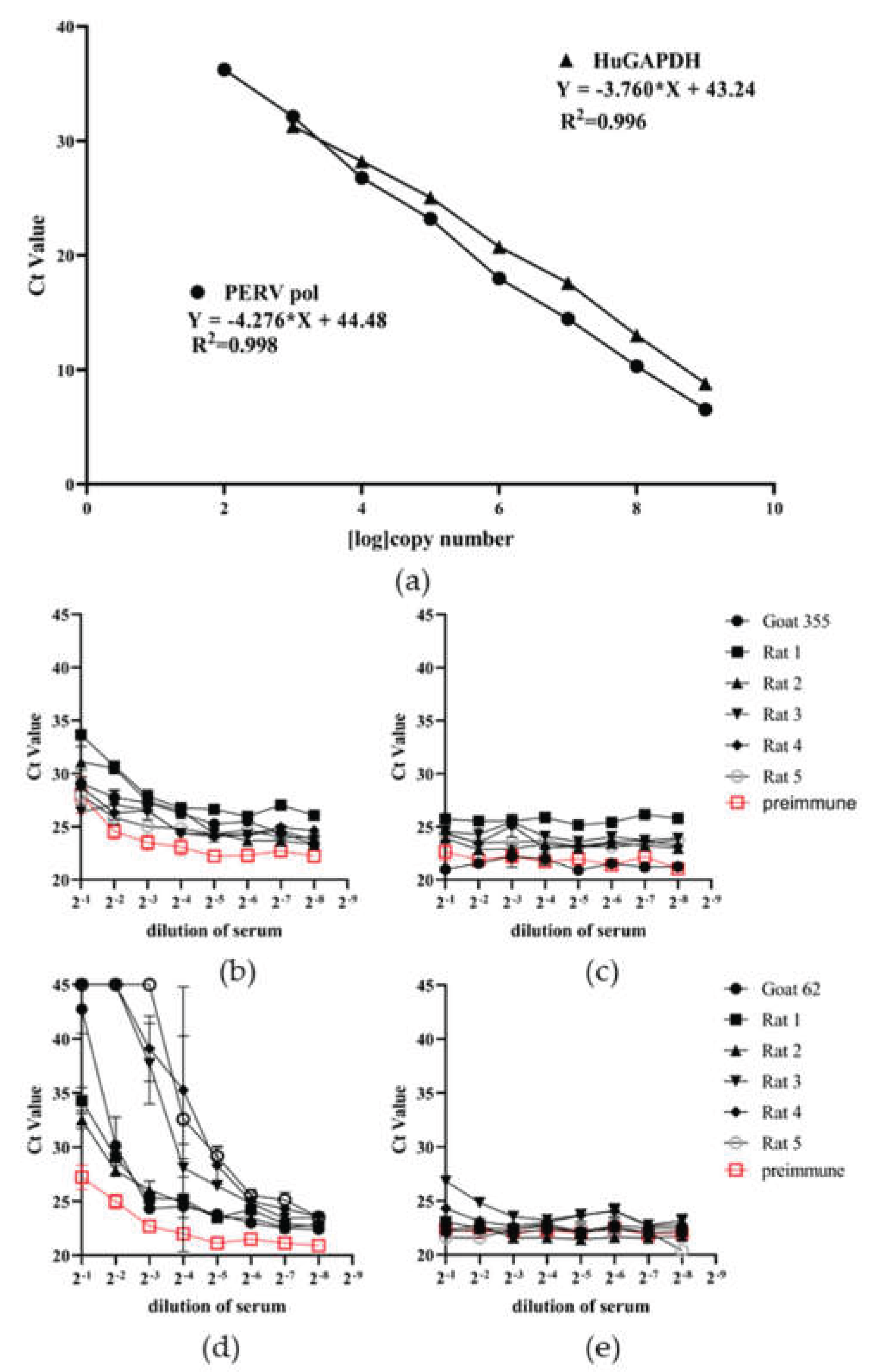

Figure 6.

Results of the neutralization assays. (a), Efficacy of the duplex real-time PCR used in the neutralization assay. A synthetic Gene block containing the sequences of the PERV pol region and of huGAPDH was in 10-fold dilution and a duplex real-time PCR was performed using primers and probes for PERV pol and huGAPDH; (b), the neutralization capacity of five rat sera against p15E, a preimmune serum and a control goat serum against p15E (serum #355) was measured detecting PERV pol using a duplex real-time PCR; (c), corresponding ct values of huGAPDH; (d), the neutralization capacity of five rat sera against gp70, a preimmune serum and goat anti-gp70 (serum #62) were measured detecting PERV pol by duplex real-time PCR; (e), corresponding ct values of huGAPDH.

Figure 6.

Results of the neutralization assays. (a), Efficacy of the duplex real-time PCR used in the neutralization assay. A synthetic Gene block containing the sequences of the PERV pol region and of huGAPDH was in 10-fold dilution and a duplex real-time PCR was performed using primers and probes for PERV pol and huGAPDH; (b), the neutralization capacity of five rat sera against p15E, a preimmune serum and a control goat serum against p15E (serum #355) was measured detecting PERV pol using a duplex real-time PCR; (c), corresponding ct values of huGAPDH; (d), the neutralization capacity of five rat sera against gp70, a preimmune serum and goat anti-gp70 (serum #62) were measured detecting PERV pol by duplex real-time PCR; (e), corresponding ct values of huGAPDH.

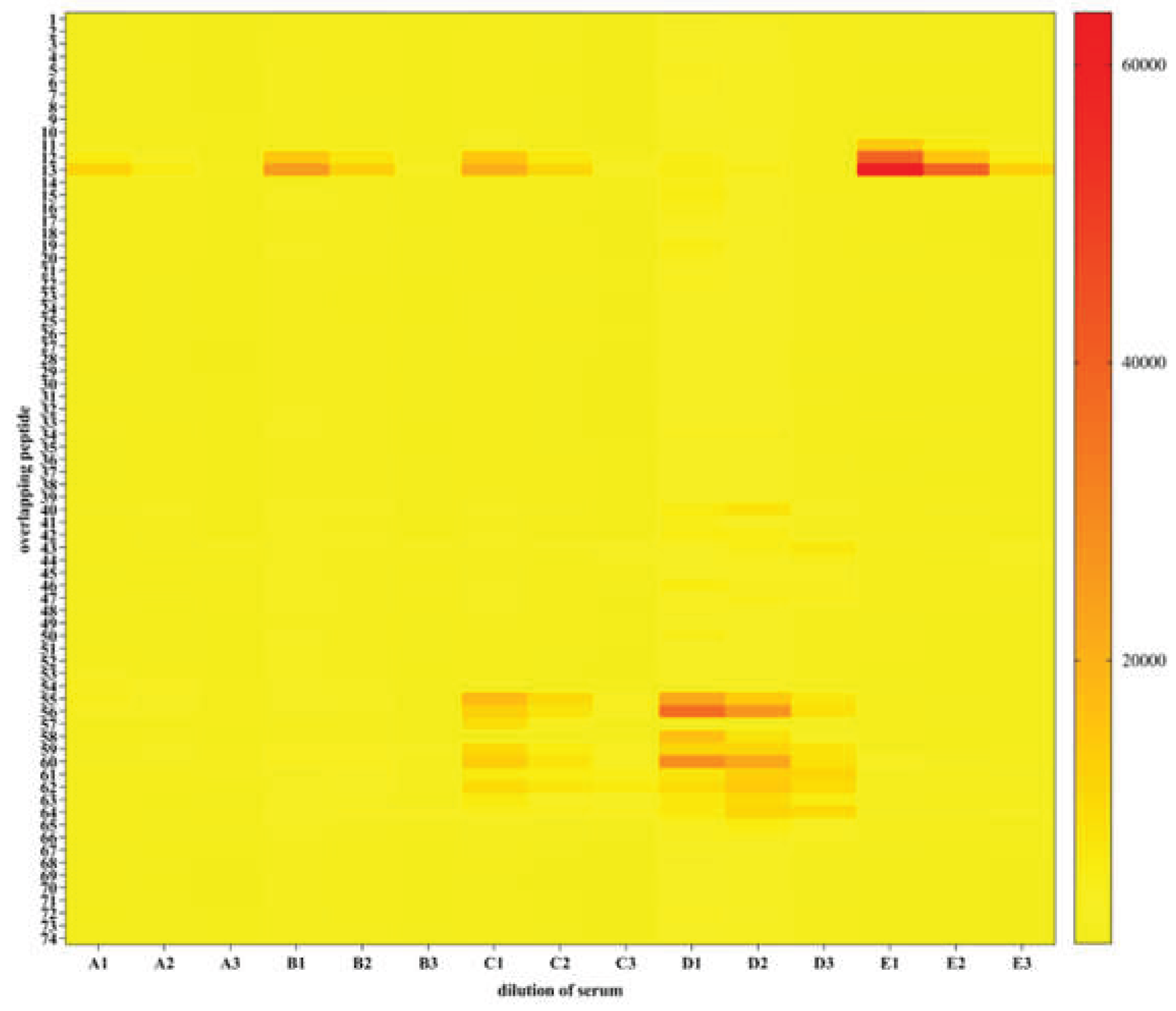

Figure 7.

Epitope mapping of five rat sera against p15E. Heatmap diagram showing all sample incubations; y-axis represents peptide sequences in the library (see

Supplementary Table 1), x-axis specifies samples applied. The MMC2 values are shown color coded ranging from white (0 or low intensity) via yellow (middle intensity) to red (high intensity). A, rats serum 1; B, rat serum 2; C, rat serum 3; D, rat serum 4; E, rat serum 5. 1, serum dilution 1:40; 2, serum dilution 1:200; 3, serum dilution 1:1000. Strong signals were obtained with control spots containing the full-length rat IgG demonstrating a correct assay performance (not shown).

Figure 7.

Epitope mapping of five rat sera against p15E. Heatmap diagram showing all sample incubations; y-axis represents peptide sequences in the library (see

Supplementary Table 1), x-axis specifies samples applied. The MMC2 values are shown color coded ranging from white (0 or low intensity) via yellow (middle intensity) to red (high intensity). A, rats serum 1; B, rat serum 2; C, rat serum 3; D, rat serum 4; E, rat serum 5. 1, serum dilution 1:40; 2, serum dilution 1:200; 3, serum dilution 1:1000. Strong signals were obtained with control spots containing the full-length rat IgG demonstrating a correct assay performance (not shown).

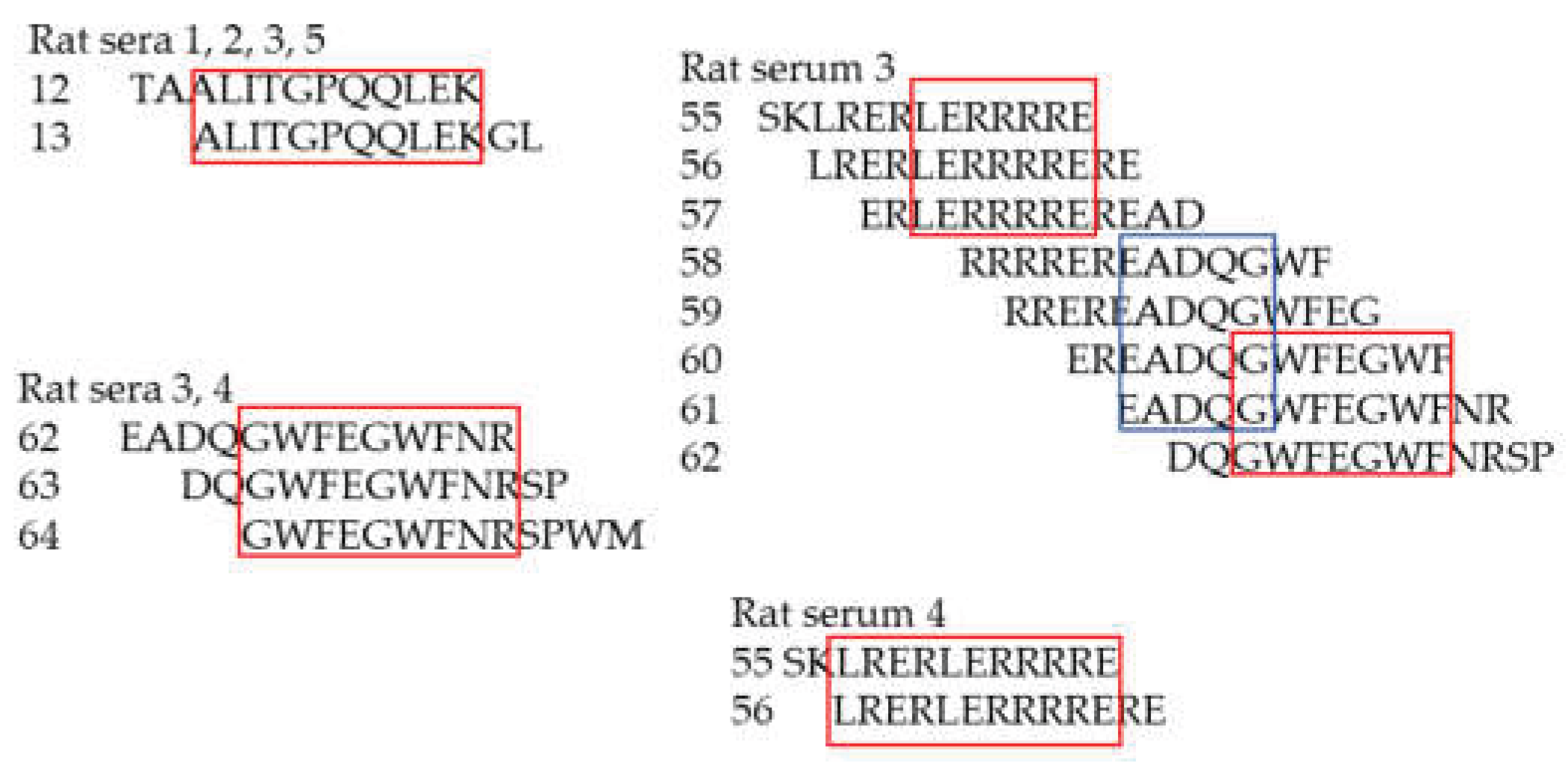

Figure 8.

Determination of the epitopes recognized by rat sera 1,2,3,4 and 5. The numbers of the rats and of the peptides are shown and the epitopes are framed.

Figure 8.

Determination of the epitopes recognized by rat sera 1,2,3,4 and 5. The numbers of the rats and of the peptides are shown and the epitopes are framed.

Figure 9.

Summary of epitopes recognized by five rat sera and one control goat serum (goat #355) against PERV p15E. The epitopes recognized by goat serum 355 were determined previously using another method, based on a cellulose-adsorbed peptide spot library of 15-mer peptides overlapping by 12 amino acids and a detection by chemiluminescence [

21].

Figure 9.

Summary of epitopes recognized by five rat sera and one control goat serum (goat #355) against PERV p15E. The epitopes recognized by goat serum 355 were determined previously using another method, based on a cellulose-adsorbed peptide spot library of 15-mer peptides overlapping by 12 amino acids and a detection by chemiluminescence [

21].

Figure 10.

A, Sequence comparison between the membrane proximal external region (MPER) of the transmembrane envelope protein PERV p15E and HIV-1 gp41. Identical amino acids are marked in red. The epitopes recognized by the immune serum from rat 3 and the epitopes recognized by the monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10, isolated from AIDS patients [

29] are shown as blue bars.

B, Sequence comparison of epitopes E1 and 2Eb of different retroviruses.

Figure 10.

A, Sequence comparison between the membrane proximal external region (MPER) of the transmembrane envelope protein PERV p15E and HIV-1 gp41. Identical amino acids are marked in red. The epitopes recognized by the immune serum from rat 3 and the epitopes recognized by the monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10, isolated from AIDS patients [

29] are shown as blue bars.

B, Sequence comparison of epitopes E1 and 2Eb of different retroviruses.

Figure 11.

Localization of the epitopes in the transmembrane envelope proteins p15E and gp41 of PERV and HIV-1, respectively, after interaction of the CHR and NHR during infection. FP, fusion peptide; NHR, N-terminal helical region; C-C loop, cysteine-cysteine loop; CHR, C-terminal helical region; MSD, membrane spanning domain.

Figure 11.

Localization of the epitopes in the transmembrane envelope proteins p15E and gp41 of PERV and HIV-1, respectively, after interaction of the CHR and NHR during infection. FP, fusion peptide; NHR, N-terminal helical region; C-C loop, cysteine-cysteine loop; CHR, C-terminal helical region; MSD, membrane spanning domain.

Table 1.

Primers and probes used for the duplex real-time PCR.

Table 1.

Primers and probes used for the duplex real-time PCR.

| Primer/probe |

Sequence 5’-3’ |

Direction |

Location (nucleotide number) |

Accession number |

Reference |

| PERV pol for |

CGACTGCCCCAAGGGTTCAA |

+ |

3568-3587 |

GenBank HM159246 |

Yang et al. [16] |

| PERV pol rev |

TCTCTCCTGCAAATCTGGGCC |

- |

3783-3803 |

| PERV pol probe |

6FAM-CACGTACTGGAGGAGGGTCACCTG-BHQ1 |

+ |

3655-3678 |

| GAPDH for |

GGCGATGCTGGCGCTGAGTAC |

+ |

365-385 |

GenBank AF261085 |

Behrendt et al. [27] |

| GAPDH rev |

TGGTTCACACCCATGACGA |

- |

495-513 |

| GAPDH probe |

HEX-CTTCACCACCATGGAGAAGGCTGGG-BHQ1 |

+ |

407-430 |