Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K. Wrońska, M. Hałasa, and M. Szczuko, “The Role of the Immune System in the Course of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: The Current State of Knowledge.,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 13, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q.-Y. Zhang et al., “Lymphocyte infiltration and thyrocyte destruction are driven by stromal and immune cell components in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.,” Nat Commun, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 775, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Groenewegen, C. F. Mooij, and A. S. P. van Trotsenburg, “Persisting symptoms in patients with Hashimoto’s disease despite normal thyroid hormone levels: Does thyroid autoimmunity play a role? A systematic review.,” J Transl Autoimmun, vol. 4, p. 100101, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Razvi, S. Mrabeti, and M. Luster, “Managing symptoms in hypothyroid patients on adequate levothyroxine: a narrative review.,” Endocr Connect, vol. 9, no. 11, pp. R241–R250, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. M. McLean and D. N. Podell, “Bone and joint manifestations of hypothyroidism.,” Semin Arthritis Rheum, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 282–90, Feb. 1995. [CrossRef]

- W.-H. Chen, Y.-K. Chen, C.-L. Lin, J.-H. Yeh, and C.-H. Kao, “Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, risk of coronary heart disease, and L-thyroxine treatment: a nationwide cohort study.,” J Clin Endocrinol Metab, vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 109–14, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Sundus, S. A. Khan, S. Zaidi, C. Chhabra, I. Ahmad, and H. Khan, “Effect of long-term exercise-based interventions on thyroid function in hypothyroidism: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.,” Complement Ther Med, vol. 92, p. 103196, Sep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Klasson, S. Sadhir, and H. Pontzer, “Daily physical activity is negatively associated with thyroid hormone levels, inflammation, and immune system markers among men and women in the NHANES dataset.,” PLoS One, vol. 17, no. 7, p. e0270221, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Metsios, R. H. Moe, and G. D. Kitas, “Exercise and inflammation.,” Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, vol. 34, no. 2, p. 101504, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Weyh, K. Krüger, and B. Strasser, “Physical Activity and Diet Shape the Immune System during Aging.,” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 3, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Sharif, A. Watad, N. L. Bragazzi, M. Lichtbroun, H. Amital, and Y. Shoenfeld, “Physical activity and autoimmune diseases: Get moving and manage the disease.,” Autoimmun Rev, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 53–72, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Luo et al., “The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise on autoimmune diseases: A 20-year systematic review.,” J Sport Health Sci, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 353–367, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Cvek et al., “Vitamin D and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: Observations from CROHT Biobank,” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 2793, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Brčić et al., “Genome-wide association analysis suggests novel loci for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis,” J Endocrinol Invest, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 567–576, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. H. S. Pearce et al., “2013 ETA Guideline: Management of Subclinical Hypothyroidism,” Eur Thyroid J, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 215–228, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Z. Kusić et al., “Croatia has reached iodine sufficiency,” J Endocrinol Invest, vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 738–742, Aug. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. Cvek et al., “Presence or severity of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis does not influence basal calcitonin levels: observations from CROHT biobank,” J Endocrinol Invest, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 597–605, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Cvek et al., “Vitamin D and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: Observations from CROHT Biobank.,” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 8, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Wik et al., “Proximity Extension Assay in Combination with Next-Generation Sequencing for High-throughput Proteome-wide Analysis,” Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, vol. 20, p. 100168, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhong, X. Zhang, and W. Chong, “Interleukin-24 Immunobiology and Its Roles in Inflammatory Diseases.,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 2, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Wozniak, J. Floege, T. Ostendorf, and A. Ludwig, “Key metalloproteinase-mediated pathways in the kidney.,” Nat Rev Nephrol, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 513–527, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Jaoude and Y. Koh, “Matrix metalloproteinases in exercise and obesity.,” Vasc Health Risk Manag, vol. 12, pp. 287–95, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Purroy et al., “Matrix metalloproteinase-10 deficiency delays atherosclerosis progression and plaque calcification.,” Atherosclerosis, vol. 278, pp. 124–134, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Matilla et al., “A Role for MMP-10 (Matrix Metalloproteinase-10) in Calcific Aortic Valve Stenosis.,” Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 1370–1382, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wei et al., “Type-specific dysregulation of matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors in end-stage heart failure patients: relationship between MMP-10 and LV remodelling.,” J Cell Mol Med, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 773–82, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. L. Clase, P. J. Mitchell, P. J. Ward, C. M. Dorman, S. E. Johnson, and K. Hannon, “FGF5 stimulates expansion of connective tissue fibroblasts and inhibits skeletal muscle development in the limb.,” Dev Dyn, vol. 219, no. 3, pp. 368–80, Nov. 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. Chen et al., “Metabolic differences in MSTN and FGF5 dual-gene edited sheep muscle cells during myogenesis.,” BMC Genomics, vol. 25, no. 1, p. 637, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M.-M. Chen et al., “A MSTNDel73C mutation with FGF5 knockout sheep by CRISPR/Cas9 promotes skeletal muscle myofiber hyperplasia.,” Elife, vol. 12, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu et al., “The effects of exercise on FGF21 in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis.,” PeerJ, vol. 12, p. e17615, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Peterson, K. A. Richardson, and L. Funderburk, “Effect of exercise on Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 levels in healthy males and females.,” PLoS One, vol. 20, no. 5, p. e0321738, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Cuevas-Ramos et al., “Exercise increases serum fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) levels.,” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 5, p. e38022, 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. Corallini, E. Rimondi, and P. Secchiero, “TRAIL and osteoprotegerin: a role in endothelial physiopathology?,” Front Biosci, vol. 13, pp. 135–47, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Kakareko, A. Rydzewska-Rosołowska, E. Zbroch, and T. Hryszko, “TRAIL and Cardiovascular Disease-A Risk Factor or Risk Marker: A Systematic Review.,” J Clin Med, vol. 10, no. 6, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Biolo, P. Secchiero, S. De Giorgi, V. Tisato, and G. Zauli, “The energy balance positively regulates the levels of circulating TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand in humans.,” Clin Nutr, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 1018–21, Dec. 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Davenport, H. Kenny, D. T. Ashley, E. P. O’Sullivan, D. Smith, and D. J. O’Gorman, “The effect of exercise on osteoprotegerin and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in obese patients.,” Eur J Clin Invest, vol. 42, no. 11, pp. 1173–9, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. İşgüven, Y. Gündüz, and M. Kılıç, “Effects of Thyroid Autoimmunity on Early Atherosclerosis in Euthyroid Girls with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis.,” J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 150–6, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Liao, R. L. Rabin, J. R. Yannelli, L. G. Koniaris, P. Vanguri, and J. M. Farber, “Human Mig chemokine: biochemical and functional characterization.,” J Exp Med, vol. 182, no. 5, pp. 1301–14, Nov. 1995. [CrossRef]

- J. Li et al., “Association between Circulating Levels of CXCL9 and CXCL10 and Physical Frailty in Older Adults.,” Gerontology, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 279–289, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. H. Seo et al., “Chemokine CXCL9, a marker of inflammaging, is associated with changes of muscle strength and mortality in older men.,” Osteoporos Int, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 1789–1796, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. C. Hu et al., “Physical activity affects DNA methylation-derived inflammation markers in a community-based Parkinson’s disease study.,” Brain Behav Immun Health, vol. 46, p. 101014, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. He, H. Wang, G. Yang, L. Zhu, and X. Liu, “The Role of Chemokines in Obesity and Exercise-Induced Weight Loss.,” Biomolecules, vol. 14, no. 9, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Anderson et al., “Functional characterization of the human interleukin-15 receptor alpha chain and close linkage of IL15RA and IL2RA genes.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 270, no. 50, pp. 29862–9, Dec. 1995. [CrossRef]

- H. Lee, S.-H. Park, and E.-C. Shin, “IL-15 in T-Cell Responses and Immunopathogenesis.,” Immune Netw, vol. 24, no. 1, p. e11, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. H. Duitman, Z. Orinska, E. Bulanova, R. Paus, and S. Bulfone-Paus, “How a cytokine is chaperoned through the secretory pathway by complexing with its own receptor: lessons from interleukin-15 (IL-15)/IL-15 receptor alpha.,” Mol Cell Biol, vol. 28, no. 15, pp. 4851–61, Aug. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Busquets, M. Figueras, V. Almendro, F. J. López-Soriano, and J. M. Argilés, “Interleukin-15 increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. An antidiabetogenic effect of the cytokine.,” Biochim Biophys Acta, vol. 1760, no. 11, pp. 1613–7, Nov. 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. Sun, Y. Ma, M. Gao, and D. Liu, “IL-15/sIL-15Rα gene transfer induces weight loss and improves glucose homeostasis in obese mice.,” Gene Ther, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 349–56, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Khalafi et al., “Interleukin-15 responses to acute and chronic exercise in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis.,” Front Immunol, vol. 14, p. 1288537, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Emdad et al., “Recent insights into apoptosis and toxic autophagy: The roles of MDA-7/IL-24, a multidimensional anti-cancer therapeutic.,” Semin Cancer Biol, vol. 66, pp. 140–154, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Wiley and J. A. Winkles, “TWEAK, a member of the TNF superfamily, is a multifunctional cytokine that binds the TweakR/Fn14 receptor.,” Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, vol. 14, no. 3–4, pp. 241–9, 2003. [CrossRef]

- C. N. Lynch, Y. C. Wang, J. K. Lund, Y. W. Chen, J. A. Leal, and S. R. Wiley, “TWEAK induces angiogenesis and proliferation of endothelial cells.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 274, no. 13, pp. 8455–9, Mar. 1999. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Donohue et al., “TWEAK is an endothelial cell growth and chemotactic factor that also potentiates FGF-2 and VEGF-A mitogenic activity.,” Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 594–600, Apr. 2003. [CrossRef]

- R. Schönbauer et al., “Regular Training Increases sTWEAK and Its Decoy Receptor sCD163-Does Training Trigger the sTWEAK/sCD163-Axis to Induce an Anti-Inflammatory Effect?,” J Clin Med, vol. 9, no. 6, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Sato et al., “TWEAK promotes exercise intolerance by decreasing skeletal muscle oxidative phosphorylation capacity.,” Skelet Muscle, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 18, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Sato, Y. Ogura, and A. Kumar, “TWEAK/Fn14 Signaling Axis Mediates Skeletal Muscle Atrophy and Metabolic Dysfunction.,” Front Immunol, vol. 5, p. 18, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Ono, M. Hayashi, F. Sasaki, and T. Nakashima, “RANKL biology: bone metabolism, the immune system, and beyond.,” Inflamm Regen, vol. 40, p. 2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Kostenuik, “Osteoprotegerin and RANKL regulate bone resorption, density, geometry and strength.,” Curr Opin Pharmacol, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 618–25, Dec. 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Jabbar, J. Drury, J. N. Fordham, H. K. Datta, R. M. Francis, and S. P. Tuck, “Osteoprotegerin, RANKL and bone turnover in postmenopausal osteoporosis.,” J Clin Pathol, vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 354–7, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Chi, L. Qiu, J. Ma, W. Wu, and Y. Zhang, “The association of osteoprotegerin and RANKL with osteoporosis: a systematic review with meta-analysis.,” J Orthop Surg Res, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 839, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Tobeiha, M. H. Moghadasian, N. Amin, and S. Jafarnejad, “RANKL/RANK/OPG Pathway: A Mechanism Involved in Exercise-Induced Bone Remodeling.,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2020, p. 6910312, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Marques et al., “Effects of resistance and aerobic exercise on physical function, bone mineral density, OPG and RANKL in older women.,” Exp Gerontol, vol. 46, no. 7, pp. 524–32, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Y. S. Lee, R. Eri, A. B. Lyons, M. C. Grimm, and H. Korner, “CC Chemokine Ligand 20 and Its Cognate Receptor CCR6 in Mucosal T Cell Immunology and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Odd Couple or Axis of Evil?,” Front Immunol, vol. 4, p. 194, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Z.-R. Shi et al., “The Chemokine, CCL20, and Its Receptor, CCR6, in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.,” J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 107–117, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Kulkarni et al., “CCR6 signaling inhibits suppressor function of induced-Treg during gut inflammation.,” J Autoimmun, vol. 88, pp. 121–130, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Ziegler, S. M. Jensen, P. Schjerling, A. L. Mackey, J. L. Andersen, and M. Kjaer, “The effect of resistance exercise upon age-related systemic and local skeletal muscle inflammation.,” Exp Gerontol, vol. 121, pp. 19–32, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- ”Effects of Resistance Exercise Intensity on Cytokine and Chemokine Gene Expression in Atopic Dermatitis Mouse Model,” J Mens Health, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 14, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Chen, K. K. Aenlle, K. M. Curtis, B. A. Roos, and G. A. Howard, “Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D together stimulate human bone marrow-derived stem cells toward the osteogenic phenotype by HGF-induced up-regulation of VDR.,” Bone, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 69–77, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhen et al., “Hepatocyte growth factor improves bone regeneration via the bone morphogenetic protein-2-mediated NF-κB signaling pathway.,” Mol Med Rep, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 6045–6053, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Huang et al., “Hepatocyte growth factor overexpression promotes osteoclastogenesis and exacerbates bone loss in CIA mice.,” J Orthop Translat, vol. 27, pp. 9–16, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Yasuda et al., “Exercise-induced hepatocyte growth factor production in patients after acute myocardial infarction: its relationship to exercise capacity and brain natriuretic peptide levels.,” Circ J, vol. 68, no. 4, pp. 304–7, Apr. 2004. [CrossRef]

- P. Wahl et al., “Effects of high intensity training and high volume training on endothelial microparticles and angiogenic growth factors.,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 4, p. e96024, 2014. [CrossRef]

| Less than an hour | Between 1-2 hours | Over 2 hours | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| 2-3 times a week | 8 | 16 | 16 |

| Once a week | 4 | 8 | 8 |

| Occasionally | 0 | 0 | 0 |

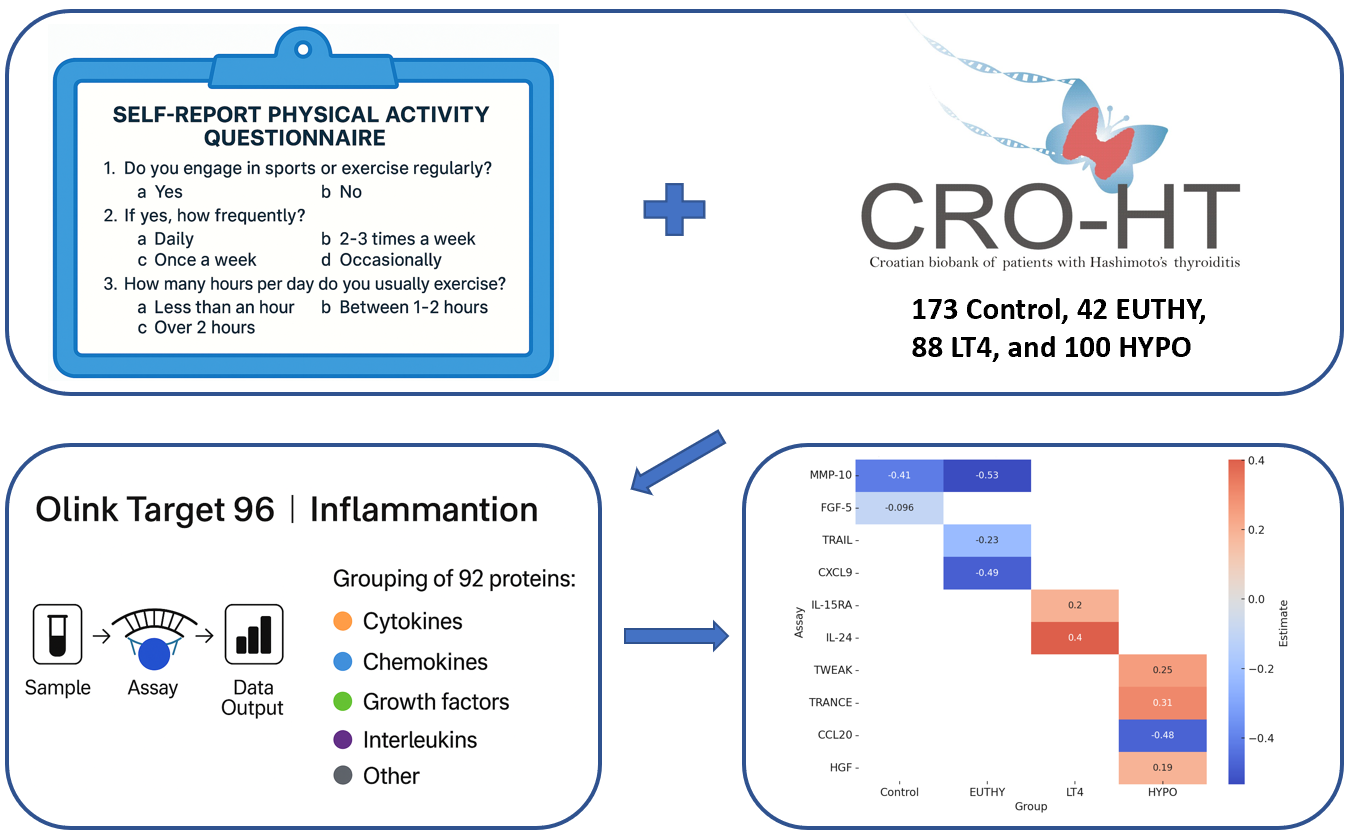

| Phenotype | Control | EUTHY | LT4 | HYPO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 173 | N = 42 | N = 88 | N = 100 | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age, years | 39,24 (11,88) | 34,39 (12,67) | 40,48 (13,87) | 39,05 (13,22) |

| BMI, kg/m² | 23,58 (3,92) | 23,80 (3,80) | 24,21 (4,25) | 24,19 (4,22) |

| T3, nmol/L | 1,55 (0,22) | 1,62 (0,42) | 1,64 (0,32) | 1,51 (0,39) |

| T4, nmol/L | 102,92 (20,30) | 98,52 (22,92) | 114,47 (26,78) | 94,18 (27,05) |

| fT4, pmol/L | 12,89 (1,62) | 12,64 (1,53) | 13,09 (2,40) | 10,50 (2,50) |

| TSH, mIU/L | 1,61 (0,67) | 2,11 (0,96) | 4,89 (8,78) | 15,89 (24,93) |

| TgAt, IU/ml | 17,36 (17,46) | 730,52 (1177,64) | 575,48 (1126,23) | 618,80 (1048,81) |

| TpOAb, IU/ml | 5,73 (5,88) | 522,37 (483,10) | 546,01 (575,37) | 620,51 (692,42) |

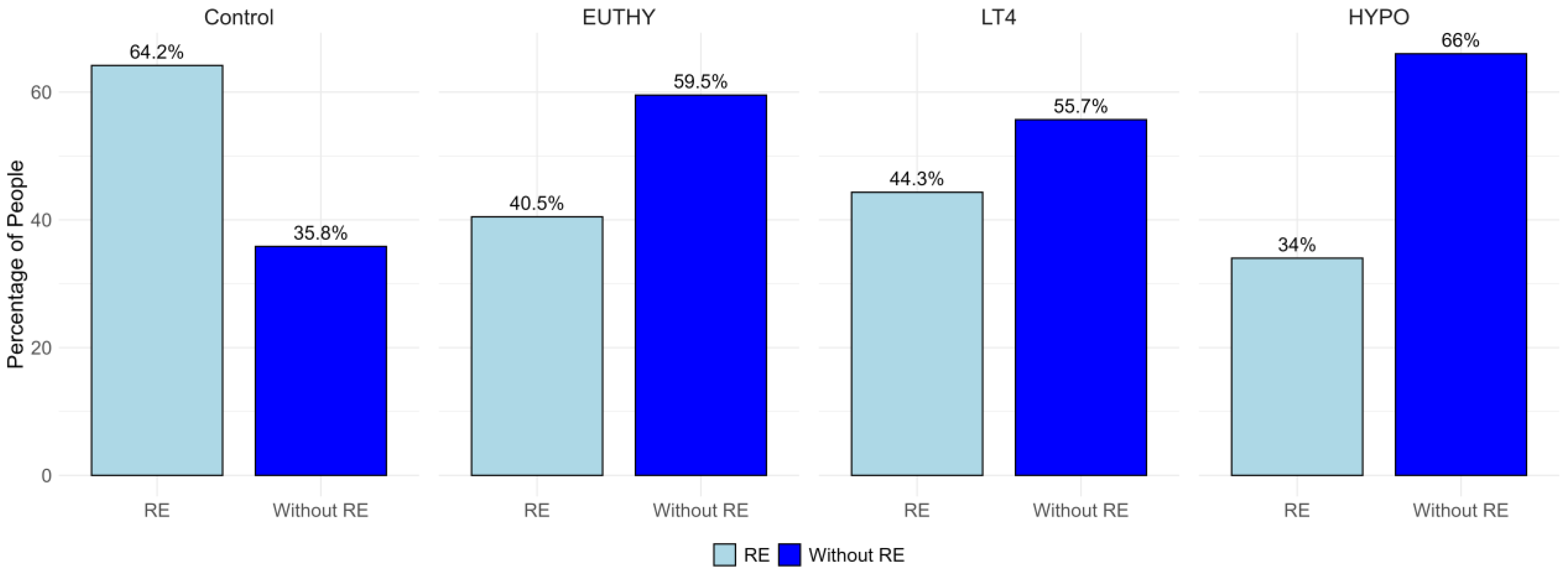

| RE, hours/month | 5,80 (5,68) | 4,57 (6,34) | 5,45 (6,79) | 4,00 (6,15) |

| Control (RE = 111, Without RE = 62) | |||

| Assay | Estimate* | p-value | adjusted p-value |

| MMP-10 | -0,4133 | 0,0026 | 0,0065 |

| FGF-5 | -0,0957 | 0,0058 | 0,0292 |

| EUTHY (RE = 17, Without RE = 25) | |||

| Assay | Estimate | p-value | adjusted p-value |

| MMP-10 | -0,5335 | 0,0070 | 0,0175 |

| TRAIL | -0,2298 | 0,0150 | 0,0375 |

| CXCL9 | -0,4858 | 0,0165 | 0,0412 |

| LT4 (RE = 39, Without RE = 49) | |||

| Assay | Estimate | p-value | adjusted p-value |

| IL-15RA | 0,1958 | 0,0042 | 0,0126 |

| IL-24 | 0,4020 | 0,0098 | 0,0163 |

| HYPO (RE = 34, Without RE = 66) | |||

| Assay | Estimate | p-value | adjusted p-value |

| TWEAK | 0,2526 | 0,0019 | 0,0047 |

| TRANCE | 0,3096 | 0,0272 | 0,0340 |

| CCL20 | -0,4781 | 0,0218 | 0,0364 |

| HGF | 0,1936 | 0,0275 | 0,0459 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).