Submitted:

21 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pharmacological Background of Monensin

3. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Anticancer Action

3.1. Induction of Cell Death Pathways

3.2. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

3.3. Disruption of Ion Homeostasis

3.4. Modulation of Oncogenic Signaling Pathways

3.5. Inhibition of Tumor Progression and Metastasis

3.6. Overcoming Drug Resistance

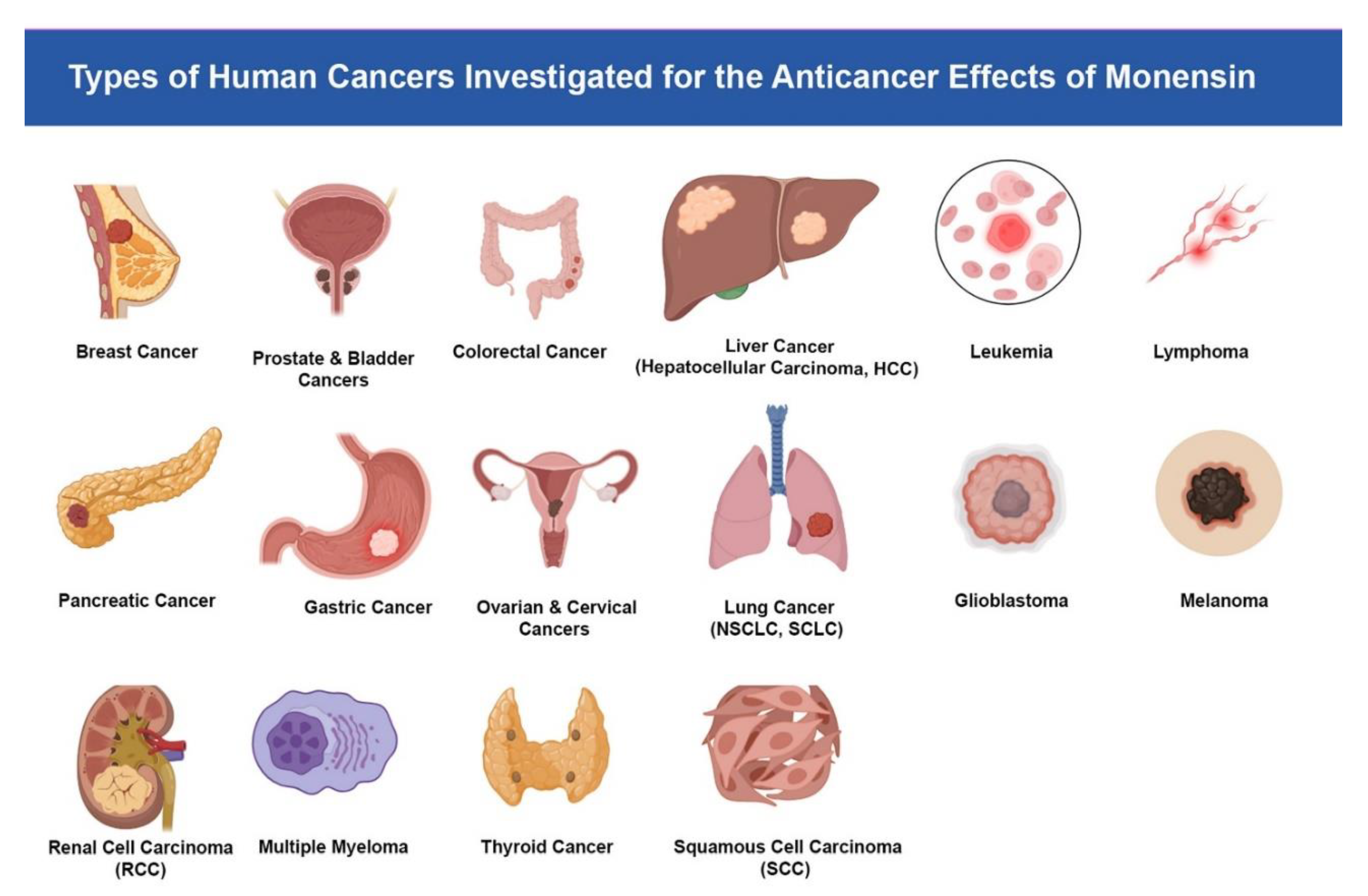

4. Preclinical Evidence in Specific Cancer Types

Breast Cancer

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

4.2. Prostate Cancer

4.3. Colorectal Cancer

- Immune signaling modulation (TLR/IRF3)

- Growth and survival pathways (IGF1R, Elk1, AP-1, Myc/Max)

- Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling

- Cell cycle regulation and apoptosis

- Drug resistance mechanisms (ATP7A, NHE)

- Invasion and metastasis (MMPs, uPA/uPAR)

- Potentiation of immunotoxins

4.4. Liver Cancer (Hepatocellular Carcinoma, HCC)

4.5. Leukemia

4.6. Lymphoma

4.7. Pancreatic Cancer

4.8. Gastric Cancer

4.9. Ovarian Cancer

4.10. Cervical Cancer

4.11. Lung Cancer (NSCLC, SCLC)

4.12. Glioblastoma

Glioblastoma Multiform (GBM)

4.13. Melanoma

4.14. Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC)

4.15. Multiple Myeloma

4.16. Thyroid Cancer

4.17. Bladder Cancer

4.18. Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

5. Advantages and Challenges

Advantages

Challenges

6. Clinical Implications and Future Perspectives

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Statement of ethics

Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Acknowledgements

Competing Interests

References

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayes N, Vito A, Mossman K. Tumor Heterogeneity: A Great Barrier in the Age of Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matĕjů J, Karnetová J, Nohýnek M, Vanĕk Z. Propionate and the production of monensins in Streptomyces cinnamonensis. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 1988, 33, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muwalla MM, Abo-Shehada MN, Tawfiq F. Effects of monensin on daily gain and natural coccidial infection in Awassi lambs. Small Ruminant Research. 1994, 13, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachliel E, Finkelstein Y, Gutman M. The mechanism of monensin-mediated cation exchange based on real time measurements. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996, 1285, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran V, Ilamathi HS, Dutt S, Lakshminarayana TS, Ghosh PC. Chemotherapeutic potential of monensin as an anti-microbial agent. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2018, 18, 1976–1986. [Google Scholar]

- Aowicki D, Huczyński A. Structure and antimicrobial properties of monensin A and its derivatives: summary of the achievements. Biomed Res Int. 2013, 2013, 742149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singh M, Kalla NR, Sanyal SN. Effect of monensin on the enzymes of oxidative stress, thiamine pyrophosphatase and DNA integrity in rat testicular cells in vitro. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2006, 58, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza AC, Machado FS, Celes MR, Faria G, Rocha LB, Silva JS, Rossi MA. Mitochondrial damage as an early event of monensin-induced cell injury in cultured fibroblasts L929. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2005, 52, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia M, Shi M, Zhao Y, Li Y, Liu X, Zhao L. The role of ATF3 in the crosstalk between cellular stress response and ferroptosis in tumors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2025, 213, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayekh K, Johnson-Obaseki S, Corsten M, Villeneuve PJ, Sekhon HS, Weberpals JI, Dimitroulakos J. Monensin inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor trafficking and activation: synergistic cytotoxicity in combination with EGFR inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 2559–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon MJ, Kang YJ, Kim IY, Kim EH, Lee JA, Lim JH, Kwon TK, Choi KS. Monensin, a polyether ionophore antibiotic, overcomes TRAIL resistance in glioma cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress, DR5 upregulation and c-FLIP downregulation. Carcinogenesis. 2013, 34, 1918–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serter Kocoglu S, Secme M, Oy C, Korkusuz G, Elmas L. Monensin, an Antibiotic Isolated from Streptomyces Cinnamonensis, Regulates Human Neuroblastoma Cell Proliferation via the PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway and Acts Synergistically with Rapamycin. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023, 12, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fu B, Fang L, Wang R, Zhang X. Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by monensin in cervical cancer. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2024, 28, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tumova L, Pombinho AR, Vojtechova M, Stancikova J, Gradl D, Krausova M, Sloncova E, Horazna M, Kriz V, Machonova O, Jindrich J, Zdrahal Z, Bartunek P, Korinek V. Monensin inhibits canonical Wnt signaling in human colorectal cancer cells and suppresses tumor growth in multiple intestinal neoplasia mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma SP, Das P. Monensin induces cell death by autophagy and inhibits matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7) in UOK146 renal cell carcinoma cell line. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2018, 54, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakaya H, Kamoi K, Tran AM, Cochran DL. Effects of Monensin on the Immunocytochemical Detection of Matrix Metalloproteinase 3 in Human Periodontal Ligament Cells. Nihon Shishubyo Gakkai Kaishi (Journal of the Japanese Society of Periodontology). 1996, 38, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste M, Huang Q, Li M, Moose D, Zhao L, Stamnes MA, Schultz M, Wu M, Henry MD. High content screening identifies monensin as an EMT-selective cytotoxic compound. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tan X, Cardin DL, Wang S, Xu Y, Russell WK. Monensin suppresses EMT-driven cancer cell motility by inducing Golgi pH-dependent exocytosis of GOLIM4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025, 122, e2501347122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ling Y, Priebe W, Perezsoler R. Intrinsic cytotoxicity and reversal of multidrug-resistance by monensin in kb parent and mdr cells. Int J Oncol. 1993, 3, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang T, Hu S, Song X, Wang J, Zuo R, Yun S, Jiang S, Guo D. Combination of monensin and erlotinib synergistically inhibited the growth and cancer stem cell properties of triple-negative breast cancer by simultaneously inhibiting EGFR and PI3K signaling pathways. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2024, 207, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain M, Garrard A, Poppenga R, Chen B, Valento M, Halliday Gittinger M. Survival after severe rhabdomyolysis following monensin ingestion. Journal of Medical Toxicology. 2017, 13, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butaye P, Devriese LA, Haesebrouck F. Antimicrobial growth promoters used in animal feed: effects of less well-known antibiotics on gram-positive bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003, 16, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang M, Xu N, Xu W, Ling G, Zhang P. Potential therapies and diagnosis based on Golgi-targeted nano drug delivery systems. Pharmacol Res. 2022, 175, 105861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr CL, Pennington TH. The effect of monensin on virion production and protein secretion in pseudorabies virus-infected cells. J Gen Virol. 1984, 65 Pt 6, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melroy D, Jones RL. The effect of monensin on intracellular transport and secretion of α-amylase isoenzymes in barley aleurone. Planta. 1986, 167, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollenhauer HH, Rowe LD, Witzel DA. Effect of monensin on the morphology of mitochondria in rodent and equine striated muscle. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1984, 26, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henn D, Lensink AV, Botha CJ. Ultrastructural changes in cardiac and skeletal myoblasts following in vitro exposure to monensin, salinomycin, and lasalocid. PLoS One. 2024, 19, e0311046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng Y, Zhang J, Wang Z, Yan Z, Qiao M, Ye J, Wei Q, Wang J, Wang X, Zhao L, Lu S, Tang S, Mohammed MK, Liu H, Fan J, Zhang F, Zou Y, Liao J, Qi H, Haydon RC, Luu HH, He TC, Tang L. Antibiotic monensin synergizes with EGFR inhibitors and oxaliplatin to suppress the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 17523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao X, Ma Y, Luo J, Xu K, Tian P, Lu C, Song J. Blocking the WNT/β-catenin pathway in cancer treatment:pharmacological targets and drug therapeutic potential. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e35989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang X, Wu X, Zhang Z, Ma C, Wu T, Tang S, Zeng Z, Huang S, Gong C, Yuan C, Zhang L, Feng Y, Huang B, Liu W, Zhang B, Shen Y, Luo W, Wang X, Liu B, Lei Y, Ye Z, Zhao L, Cao D, Yang L, Chen X, Haydon RC, Luu HH, Peng B, Liu X, He TC. Monensin inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth of chemo-resistant pancreatic cancer cells by targeting the EGFR signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 17914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vraila M, Asp E, Melo FR, Grujic M, Rollman O, Pejler G, Lampinen M. Monensin induces secretory granule-mediated cell death in eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023, 152, 1312–1320.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumova L, Pombinho AR, Vojtechova M, Stancikova J, Gradl D, Krausova M, Sloncova E, Horazna M, Kriz V, Machonova O, Jindrich J, Zdrahal Z, Bartunek P, Korinek V. Monensin inhibits canonical Wnt signaling in human colorectal cancer cells and suppresses tumor growth in multiple intestinal neoplasia mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon MJ, Kang YJ, Kim IY, Kim EH, Lee JA, Lim JH, Kwon TK, Choi KS. Monensin, a polyether ionophore antibiotic, overcomes TRAIL resistance in glioma cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress, DR5 upregulation and c-FLIP downregulation. Carcinogenesis. 2013, 34, 1918–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charvat RA, Arrizabalaga G. Oxidative stress generated during monensin treatment contributes to altered Toxoplasma gondii mitochondrial function. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 22997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bharti H, Singal A, Raza M, Ghosh PC, Nag A. Ionophores as Potent Anti-malarials: A Miracle in the Making. Curr Top Med Chem. 2019, 18, 2029–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova J, Kamenova K, Petrova E, Vladov I, Gluhcheva Y, Dorkov P. Comparative study on the effects of salinomycin, monensin and meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid on the concentrations of lead, calcium, copper, iron and zinc in lungs and heart in lead-exposed mice. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2020, 58, 126429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragwidge JM, Scholl S, Schumacher K, Gendall AR. NHX-type Na+(K+)/H+ antiporters are required for TGN/EE trafficking and endosomal ion homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs226472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song X, Akasaka H, Wang H, Abbasgholizadeh R, Shin JH, Zang F, Chen J, Logsdon CD, Maitra A, Bean AJ, Wang H. Hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 down-regulates the oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinase AXL in pancreatic cancer. J Biol Chem. 2020, 295, 2348–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kawano M, Ueno A, Ashida Y, Matsumoto N, Inoue H. Effects of sialagogues on ornithine decarboxylase induction and proto-oncogene expression in murine parotid gland. J Dent Res. 1992, 71, 1885–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Sun Q, Chen S, Yu X, Jing H. Monensin Inhibits Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer via Disrupting Mitochondrial Respiration and AMPK/mTOR Signaling. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2022, 22, 2539–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan X, Cardin DL, Wang S, Xu Y, Russell WK. Monensin suppresses EMT-driven cancer cell motility by inducing Golgi pH-dependent exocytosis of GOLIM4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025, 122, e2501347122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang Y, Wang Y, Read E, Fu M, Pei Y, Wu L, Wang R, Yang G. Golgi Stress Response, Hydrogen Sulfide Metabolism, and Intracellular Calcium Homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu F, Zhong H, Chang Y, Li D, Jin H, Zhang M, Wang H, Jiang C, Shen Y, Huang Y. Targeting death receptors for drug-resistant cancer therapy: Codelivery of pTRAIL and monensin using dual-targeting and stimuli-responsive self-assembling nanocomposites. Biomaterials. 2018, 158, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbaniak A, Heflin B, Siegel E, Reed MR, Nix JS, Yee EU, Jędrzejczyk M, Klejborowska G, Stępczyńska N, Huczyński A, Nagalo MB, Chambers TC, Post S, Eoff RL, MacNicol MC, Tiwari AK, Kelly T, Tackett AJ, MacNicol AM. Monensin and Its Analogs Exhibit Activity Against Breast Cancer Stem-Like Cells in an Organoid Model. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 Jul 9:2025.07.05.663311. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fiorilla S, Tasso F, Clemente N, Trisciuoglio T, Boldorini R, Carini R. Monensin Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in Mice by a Na+-Dependent Cytotoxic Action Unrelated to Cytostatic Effects. Cells. 2025, 14, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang J, Dong Y, Xu J, Qian X, Cai Y, Chen Y, Zhang P, Gao D, Cui Z, Cui Y. TM9SF3 is a Golgi-resident ATG8-binding protein essential for Golgi-selective autophagy. Dev Cell. S: 27, 1534. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Cui Y. TM9SF3 is a mammalian Golgiphagy receptor that safeguards Golgi integrity and glycosylation fidelity. Autophagy. 1: 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang T, Hu S, Song X, Wang J, Zuo R, Yun S, Jiang S, Guo D. Combination of monensin and erlotinib synergistically inhibited the growth and cancer stem cell properties of triple-negative breast cancer by simultaneously inhibiting EGFR and PI3K signaling pathways. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2024, 207, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Jiang P, Shen X, Lyu J, Liu C, Li L, Huang Y. Cascade Delivery to Golgi Apparatus and On-Site Formation of Subcellular Drug Reservoir for Cancer Metastasis Suppression. Small. 2023, 19, e2204747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marjanović M, Mikecin Dražić AM, Mioč M, Paradžik M, Kliček F, Novokmet M, Lauc G, Kralj M. Salinomycin disturbs Golgi function and specifically affects cells in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Sci. 2023, 136, jcs260934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva SV, Lima MA, Hodgson L, Freitas VM, Rodríguez-Manzaneque JC. ADAMTS-1 has nuclear localization in cells with epithelial origin and leads to decreased cell migration. Exp Cell Res. 2023, 433, 113852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hansen MB, Postol M, Tvingsholm S, Nielsen IØ, Dietrich TN, Puustinen P, Maeda K, Dinant C, Strauss R, Egan D, Jäättelä M, Kallunki T. Identification of lysosome-targeting drugs with anti-inflammatory activity as potential invasion inhibitors of treatment resistant HER2 positive cancers. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2021, 44, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gu J, Huang L, Zhang Y. Monensin inhibits proliferation, migration, and promotes apoptosis of breast cancer cells via downregulating UBA2. Drug Dev Res. 2020, 81, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo-Abrahão T, Lacerda-Abreu MA, Gomes T, Cosentino-Gomes D, Carvalho-de-Araújo AD, Rodrigues MF, Oliveira ACL, Rumjanek FD, Monteiro RQ, Meyer-Fernandes JR. Characterization of inorganic phosphate transport in the triple-negative breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0191270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bareford LM, Phelps MA, Foraker AB, Swaan PW. Intracellular processing of riboflavin in human breast cancer cells. Mol Pharm. 2008, 5, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketola K, Vainio P, Fey V, Kallioniemi O, Iljin K. Monensin is a potent inducer of oxidative stress and inhibitor of androgen signaling leading to apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 3175–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim SH, Kim KY, Yu SN, Park SG, Yu HS, Seo YK, Ahn SC. Monensin induces PC-3 prostate cancer cell apoptosis via ROS production and Ca2+ homeostasis disruption. Anticancer research. 2016, 36, 5835–5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He Z, Zhang Y, Mehta SK, Pierson DL, Wu H, Rohde LH. Expression profile of apoptosis-related genes and radio-sensitivity of prostate cancer cells. J Radiat Res. 2011, 52, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye Z, Rohde LH, Wu H. Radio-sensitization of Prostate Cancer Cells by Monensin Treatment and its associated Gene Expression Profiling Changes. In54th Annual Meeting of the Radiation Research Society 2008 Jan 1.

- Ketola K, Vuoristo A, Oresic M, Kallioniemi O, Iljin K. Abstract A62: Monensin-induced oxidative stress reduces prostate cancer cell motility and cancer stem cell markers. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2011, 10 (Suppl. 11). [Google Scholar]

- Kaneski CR, Constantopoulos G, Brady RO. Effect of dimethylsulfoxide on the proliferation and glycosaminoglycan synthesis of rat prostate adenocarcinoma cells (PAIII) in vitro: isolation and characterization of DMSO-resistant cells. Prostate. 1991, 18, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seçme M, Kocoglu SS. Investigation of the TLR4 and IRF3 signaling pathway-mediated effects of monensin in colorectal cancer cells. Med Oncol. 2023, 40, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou Y, Deng Y, Wang J, Yan Z, Wei Q, Ye J, Zhang J, He TC, Qiao M. Effect of antibiotic monensin on cell proliferation and IGF1R signaling pathway in human colorectal cancer cells. Ann Med. 2023, 55, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tumova L, Pombinho AR, Vojtechova M, Stancikova J, Gradl D, Krausova M, Sloncova E, Horazna M, Kriz V, Machonova O, Jindrich J, Zdrahal Z, Bartunek P, Korinek V. Monensin inhibits canonical Wnt signaling in human colorectal cancer cells and suppresses tumor growth in multiple intestinal neoplasia mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park WH, Kim ES, Jung CW, Kim BK, Lee YY. Monensin-mediated growth inhibition of SNU-C1 colon cancer cells via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2003, 22, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Owatari S, Akune S, Komatsu M, Ikeda R, Firth SD, Che XF, Yamamoto M, Tsujikawa K, Kitazono M, Ishizawa T, Takeuchi T, Aikou T, Mercer JF, Akiyama S, Furukawa T. Copper-transporting P-type ATPase, ATP7A, confers multidrug resistance and its expression is related to resistance to SN-38 in clinical colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 4860–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paduch R, Kandefer-Szerszeń M. Expression and activation of proteases in co-cultures. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2011, 63, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miraglia E, Viarisio D, Riganti C, Costamagna C, Ghigo D, Bosia A. Na+/H+ exchanger activity is increased in doxorubicin-resistant human colon cancer cells and its modulation modifies the sensitivity of the cells to doxorubicin. Int J Cancer. 2005, 115, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin T, Rybak ME, Recht L, Singh M, Salimi A, Raso V. Potentiation of antitumor immunotoxins by liposomal monensin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh M, Griffin T, Salimi A, Micetich RG, Atwal H. Potentiation of ricin A immunotoxin by monoclonal antibody targeted monensin containing small unilamellar vesicles. Cancer Lett. 1994, 84, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin TW, Pagnini PG, McGrath JJ, McCann JC, Houston LL. In vitro cytotoxicity of recombinant ricin A chain-antitransferrin receptor immunotoxin against human adenocarcinomas of the colon and pancreas. J Biol Response Mod. 1988, 7, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffin TW, Childs LR, FitzGerald DJ, Levin LV. Enhancement of the cytotoxic effect of anti-carcinoembryonic antigen immunotoxins by adenovirus and carboxylic ionophores. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987, 79, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Batra S, Alenfall J. Effect of diverse categories of drugs on human colon tumour cell proliferation. Anticancer Res. 1991, 11, 1221–1224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clemente N, Baroni S, Fiorilla S, Tasso F, Reano S, Borsotti C, Ruggiero MR, Alchera E, Corrazzari M, Walker G, Follenzi A, Crich SG, Carini R. Boosting intracellular sodium selectively kills hepatocarcinoma cells and induces hepatocellular carcinoma tumor shrinkage in mice. Commun Biol. 2023, 6, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu Q, Liao S, Wei T, Liu S, Yang C, Tang J. Development of a novel prognostic signature based on cytotoxic T lymphocyte-evasion genes for hepatocellular carcinoma patient management. Discov Oncol. 2025, 16, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park WH, Lee MS, Park K, Kim ES, Kim BK, Lee YY. Monensin-mediated growth inhibition in acute myelogenous leukemia cells via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. International journal of cancer. 2002, 101, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park WH, Kim ES, Kim BK, Lee YY. Monensin-mediated growth inhibition in NCI-H929 myeloma cells via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. International journal of oncology. 2003, 23, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Yusenko MV, Trentmann A, Andersson MK, Ghani LA, Jakobs A, Paz MF, Mikesch JH, von Kries JP, Stenman G, Klempnauer KH. Monensin, a novel potent MYB inhibitor, suppresses proliferation of acute myeloid leukemia and adenoid cystic carcinoma cells. Cancer letters. 2020, 479, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivas RV, Melsen LR, Compans RW. Effects of monensin on morphogenesis and infectivity of Friend murine leukemia virus. Journal of Virology. 1982, 42, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin DT, Kinkade Jr JM, Parmley RT. Biochemical and ultrastructural effects of monensin on the processing, intracellular transport, and packaging of myeloperoxidase into low and high density compartments of human leukemia (HL-60) cells. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1987, 257, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng C, Long M, Lu Y. Monensin synergizes with chemotherapy in uveal melanoma through suppressing RhoA. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 2023, 45, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertler AA, Schlossman DM, Borowitz MJ, Blythman HE, Casellas P, Frankel AE. An anti-CD5 immunotoxin for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: enhancement of cytotoxicity with human serum albumin-monensin. International journal of cancer. 1989, 43, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park WH, Seol JG, Kim ES, Kang WK, Im YH, Jung CW, Kim BK, Lee YY. Monensin-mediated growth inhibition in human lymphoma cells through cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Br J Haematol. 2002, 119, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torun A, Zdanowicz A, Miazek-Zapala N, Zapala P, Pradhan B, Jedrzejczyk M, Ciechanowicz A, Pilch Z, Skorzynski M, Słabicki M, Rymkiewicz G, Barankiewicz J, Martines C, Laurenti L, Struga M, Winiarska M, Golab J, Kucia M, Ratajczak MZ, Huczynski A, Calado DP, Efremov DG, Zerrouqi A, Pyrzynska B. Potassium/sodium cation carriers robustly upregulate CD20 antigen by targeting MYC, and synergize with anti- CD20 immunotherapies to eliminate malignant B cells. Haematologica. 2025, 110, 1555–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Di Virgilio S, Rampelberg M, Greimers R, Schnek G, Hooghe R. The effects of monensin on blood-borne arrest and glycosylation of BL/VL3 lymphoma cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 1992, 10, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park WH, Kim ES, Kim BK, Lee YY. Monensin-mediated growth inhibition in NCI-H929 myeloma cells via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2003, 23, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park WH, Kim ES, Jung CW, Kim BK, Lee YY. Monensin-mediated growth inhibition of SNU-C1 colon cancer cells via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2003, 22, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz TD, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Hearne A, Schuh W, Wittner J, Schulz SR, Winkler TH, Jäck HM, Mielenz D. TFG is required for autophagy flux and to prevent endoplasmic reticulum stress in CH12 B lymphoma cells. Autophagy. 2021, 17, 2238–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Augustine EC, Kensinger RS. Endocytosis and degradation of ovine prolactin by Nb2 lymphoma cells: characterization and effects of agents known to alter prolactin-induced mitogenesis. Endocrinology. 1990, 127, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Luit AH, Budde M, Verheij M, Van Blitterswijk WJ. Different modes of internalization of apoptotic alkyl-lysophospholipid and cell-rescuing lysophosphatidylcholine. Biochem J. 2003, 374 Pt 3, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang X, Wu X, Zhang Z, Ma C, Wu T, Tang S, Zeng Z, Huang S, Gong C, Yuan C, Zhang L, Feng Y, Huang B, Liu W, Zhang B, Shen Y, Luo W, Wang X, Liu B, Lei Y, Ye Z, Zhao L, Cao D, Yang L, Chen X, Haydon RC, Luu HH, Peng B, Liu X, He TC. Monensin inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth of chemo-resistant pancreatic cancer cells by targeting the EGFR signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 17914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pádua D, Figueira P, Pombinho A, Monteiro I, Pereira CF, Almeida R, Mesquita P. HMGA1 stimulates cancer stem-like features and sensitivity to monensin in gastric cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2024, 442, 114257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pádua D, Barros R, Amaral AL, Mesquita P, Freire AF, Sousa M, Maia AF, Caiado I, Fernandes H, Pombinho A, Pereira CF, Almeida R. A SOX2 Reporter System Identifies Gastric Cancer Stem-Like Cells Sensitive to Monensin. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tokui T, Takatori T, Shinozaki N, Ishigami M, Shiraishi A, Ikeda T, Tsuruo T. Delivery and cytotoxicity of RS-1541 in St-4 human gastric cancer cells in vitro by the low-density-lipoprotein pathway. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao S, Wang W, Zhou B, Cui X, Yang H, Zhang S. Monensin suppresses cell proliferation and invasion in ovarian cancer by enhancing MEK1 SUMOylation. Exp Ther Med. 2021, 22, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng Y, Zhang J, Wang Z, Yan Z, Qiao M, Ye J, Wei Q, Wang J, Wang X, Zhao L, Lu S, Tang S, Mohammed MK, Liu H, Fan J, Zhang F, Zou Y, Liao J, Qi H, Haydon RC, Luu HH, He TC, Tang L. Antibiotic monensin synergizes with EGFR inhibitors and oxaliplatin to suppress the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 17523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hansen MB, Postol M, Tvingsholm S, Nielsen IØ, Dietrich TN, Puustinen P, Maeda K, Dinant C, Strauss R, Egan D, Jäättelä M, Kallunki T. Identification of lysosome-targeting drugs with anti-inflammatory activity as potential invasion inhibitors of treatment resistant HER2 positive cancers. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2021, 44, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fu B, Fang L, Wang R, Zhang X. Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by monensin in cervical cancer. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2024, 28, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Choi HS, Jeong EH, Lee TG, Kim SY, Kim HR, Kim CH. Autophagy Inhibition with Monensin Enhances Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis Induced by mTOR or Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors in Lung Cancer Cells. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2013, 75, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ochi K, Suzawa K, Tomida S, Shien K, Takano J, Miyauchi S, Takeda T, Miura A, Araki K, Nakata K, Yamamoto H, Okazaki M, Sugimoto S, Shien T, Yamane M, Azuma K, Okamoto Y, Toyooka S. Overcoming epithelial-mesenchymal transition-mediated drug resistance with monensin-based combined therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020, 529, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan X, Cardin DL, Wang S, Xu Y, Russell WK. Monensin suppresses EMT-driven cancer cell motility by inducing Golgi pH-dependent exocytosis of GOLIM4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025, 122, e2501347122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chung BM, Raja SM, Clubb RJ, Tu C, George M, Band V, Band H. Aberrant trafficking of NSCLC-associated EGFR mutants through the endocytic recycling pathway promotes interaction with Src. BMC Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary I, Doherty G, Moran E, Clynes M. The multidrug-resistant human lung tumour cell line, DLKP-A10, expresses novel drug accumulation and sequestration systems. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997, 53, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou Y, Liu Q, Dai X, Yan Y, Yang Y, Li H, Zhou X, Gao W, Li X, Xi Z. Transdifferentiation of type II alveolar epithelial cells induces reactivation of dormant tumor cells by enhancing TGF-β1/SNAI2 signaling. Oncol Rep. 2018, 39, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastroianni A, Invernizzi L, Tagliabue E, Fassina G, Albini A, Ménard S, Colnaghi MI. Alteration of laminin production in small-cell lung carcinoma: possible correlation with the absence of the basement membrane. Tumour Biol. 1993, 14, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derbyshire EJ, Henry RV, Stahel RA, Wawrzynczak EJ. Potent cytotoxic action of the immunotoxin SWA11-ricin A chain against human small cell lung cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1992, 66, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Urbaniak A, Reed MR, Heflin B, Gaydos J, Piña-Oviedo S, Jędrzejczyk M, Klejborowska G, Stępczyńska N, Chambers TC, Tackett AJ, Rodriguez A, Huczyński A, Eoff RL, MacNicol AM. Anti-glioblastoma activity of monensin and its analogs in an organoid model of cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wan W, Zhang X, Huang C, Chen L, Yang X, Bao K, Peng T. Monensin inhibits glioblastoma angiogenesis via targeting multiple growth factor receptor signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020, 530, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko M, Makena MR, Schiapparelli P, Suarez-Meade P, Mekile AX, Lal B, Lopez-Bertoni H, Kozielski KL, Green JJ, Laterra J, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Rao R. The endosomal pH regulator NHE9 is a driver of stemness in glioblastoma. PNAS Nexus. 2022, 1, pgac013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schraen-Maschke S, Zanetta JP. Role of oligomannosidic N-glycans in the proliferation, adhesion and signalling of C6 glioblastoma cells. Biochimie. 2003, 85, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chignola R, Foroni R, Candiani C, Franceschi A, Pasti M, Stevanoni G, Anselmi C, Tridente G, Colombatti M. Cytoreductive effects of anti-transferrin receptor immunotoxin in a multicellular tumor spheroid model. Int J Cancer. 1994, 57, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin T, Rybak ME, Recht L, Singh M, Salimi A, Raso V. Potentiation of antitumor immunotoxins by liposomal monensin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zovickian J, Johnson VG, Youle RJ. Potent and specific killing of human malignant brain tumor cells by an anti-transferrin receptor antibody-ricin immunotoxin. J Neurosurg. 1987, 66, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin T, Rybak ME, Recht L, Singh M, Salimi A, Raso V. Potentiation of antitumor immunotoxins by liposomal monensin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basque J, Martel M, Leduc R, Cantin AM. Lysosomotropic drugs inhibit maturation of transforming growth factor-beta. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008, 86, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Businaro R, Fabrizi C, Fumagalli L, Lauro GM. Synthesis and secretion of alpha 2-macroglobulin by human glioma established cell lines. Exp Brain Res. 1992, 88, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benya RV, Kusui T, Shikado F, Battey JF, Jensen RT. Desensitization of neuromedin B receptors (NMB-R) on native and NMB-R-transfected cells involves down-regulation and internalization. J Biol Chem. 1994, 269, 11721–11728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin H, Li J, Zhang H, Li Y, Zeng S, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Deng F. Monensin may inhibit melanoma by regulating the selection between differentiation and stemness of melanoma stem cells. PeerJ. 2019, 7, e7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zeng C, Long M, Lu Y. Monensin synergizes with chemotherapy in uveal melanoma through suppressing RhoA. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2023, 45, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumol TF, Reisfeld RA. Biosynthesis and secretion of fibronectin in human melanoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 1983, 21, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumova L, Pombinho AR, Vojtechova M, Stancikova J, Gradl D, Krausova M, Sloncova E, Horazna M, Kriz V, Machonova O, Jindrich J, Zdrahal Z, Bartunek P, Korinek V. Monensin inhibits canonical Wnt signaling in human colorectal cancer cells and suppresses tumor growth in multiple intestinal neoplasia mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukao H, Ueshima S, Sakai T, Okada K, Matsuo O. Effect of monensin on secretion of t-PA from melanoma (Bowes). Cell Struct Funct. 1989, 14, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negroiu G, Dwek RA, Petrescu SM. Tyrosinase-related protein-2 and -1 are trafficked on distinct routes in B16 melanoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005, 328, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth JA, Ames RS, Fry K, Lee HM, Scannon PJ. Mediation of reduction of spontaneous and experimental pulmonary metastases by ricin A-chain immunotoxin 45-2D9-RTA with potentiation by systemic monensin in mice. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 3496–3501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saeki H, Oikawa A. Stimulation by ionophores of tyrosinase activity of mouse melanoma cells in culture. J Invest Dermatol. 1985, 85, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 27. Jara JR, Martinez-Liarte JH, Solano F. Transport of L-tyrosine by B16/F10 malignant melanocytes: characterization of the process. Pigment Cell Res. 1990, 3, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma SP, Das P. Monensin induces cell death by autophagy and inhibits matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7) in UOK146 renal cell carcinoma cell line. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2018, 54, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park WH, Jung CW, Park JO, Kim K, Kim WS, Im YH, Lee MH, Kang WK, Park K. Monensin inhibits the growth of renal cell carcinoma cells via cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2003, 22, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiao GF, Yan X, Chen Z, Zhang RJ, Liu TZ, Hu WL. Identification of a Novel Immune-Related Prognostic Biomarker and Small-Molecule Drugs in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC) by a Merged Microarray-Acquired Dataset and TCGA Database. Front Genet. 2020, 11, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park WH, Kim ES, Kim BK, Lee YY. Monensin-mediated growth inhibition in NCI-H929 myeloma cells via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2003, 23, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Puvvula PK, Martinez-Medina L, Cinar M, Feng L, Pisarev A, Johnson A, Bernal-Mizrachi L. A retrotransposon-derived DNA zip code internalizes myeloma cells through Clathrin-Rab5a-mediated endocytosis. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1288724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li Y, Sun Q, Chen S, Yu X, Jing H. Monensin Inhibits Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer via Disrupting Mitochondrial Respiration and AMPK/mTOR Signaling. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2022, 22, 2539–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pooley L, Shakur Y, Rena G, Houslay MD. Intracellular localization of the PDE4A cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase splice variant RD1 (RNPDE4A1A) in stably transfected human thyroid carcinoma FTC cell lines. Biochem J. 1997, 321 Pt 1, 177–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Plattner VE, Wagner M, Ratzinger G, Gabor F, Wirth M. Targeted drug delivery: binding and uptake of plant lectins using human 5637 bladder cancer cells. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008, 70, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamou S, Shimizu N. Glycosylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and its relationship to membrane transport and ligand binding. J Biochem. 1988, 104, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamou S, Hirai M, Rikimaru K, Enomoto S, Shimizu N. Biosynthesis of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human squamous cell carcinoma lines: secretion of the truncated receptor is not common to epidermal growth factor receptor-hyperproducing cells. Cell Struct Funct. 1988, 13, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr RB, Kamen BA. UMSCC38 cells amplified at 11q13 for the folate receptor synthesize a mutant nonfunctional folate receptor. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 3905–3911. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).