1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disorder marked by progressive cognitive decline, remains a leading cause of morbidity in aging populations worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. Traditional monotherapeutic, pharmaceutical approaches, have yielded limited clinical benefits [

4,

5]. We and others have demonstrated that a range of metabolic abnormalities—including insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, hypovitaminosis D, hormonal imbalances, and elevated homocysteine levels—are key contributors to the pathophysiology of AD. These metabolic dysfunctions often interact and compound over time, creating biochemical and physiological disturbances that drive cognitive decline.

Recent clinical trials and observational studies have shown that addressing multiple such factors concurrently leads to superior outcomes compared to targeting a single variable [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. A multi-therapeutic, personalized approach that evaluates and treats the full range of contributing metabolic factors may be more aligned with the multifactorial nature of AD. This strategy aims not just to manage symptoms but to alter the trajectory of disease progression by restoring systemic balance and supporting neuronal resilience. Moreover, this approach is more sustainable in the long term as it promotes overall health and addresses comorbidities that commonly accompany aging and cognitive decline, such as hypertension, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

The ReCODE (Reversal of Cognitive Decline) program is a multi-therapeutic, precision medicine approach that evaluates and treats the full range of contributing metabolic, infectious, immune, vascular, and toxic factors. The program targets multiple biological mechanisms underlying AD—such as inflammation, insulin resistance, nutrient deficiencies, toxin exposure, and hormonal imbalances—through personalized lifestyle and therapeutic interventions [

20,

21]. Notably, the first clinical trial using this protocol demonstrated statistically significant cognitive improvement in 84% of patients with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage dementia over a 9-month intervention, measured by MoCA and other neuropsychological tools [

14,

15]. Complementing this trial, other independent observational studies and clinical trials have validated the benefits of multi-therapeutic approaches that evaluate and treat a range of contributing factors in varied clinical settings. These studies consistently reported improvement or stabilization in cognitive performance across diverse populations, using tools such as CNS Vital Signs, MoCA, MRI volumetrics, and laboratory-based assessments. Importantly, patients also experienced improved metabolic profiles, enhanced quality of life, and reduced medication dependency [

13,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

Depression is a frequent comorbidity in AD and related dementias, affecting up to 50% of patients. It contributes to decreased quality of life, increased caregiver burden, and potentially accelerated cognitive decline [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a validated instrument widely used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms and to monitor clinical change [

30,

31,

32]. Given the bidirectional relationship between mood and cognition, evaluating depression outcomes is important for understanding the program’s broader therapeutic effects.

The present study focuses specifically on changes in PHQ-9 scores following short-term participation in ReCODE with the aim of determining whether the multi-therapeutic program can meaningfully reduce depression in individuals with AD.

2. Methods

2.1. ReCODE Protocol Components, Software and Program Implementation

The ReCODE program (Reversal of Cognitive Decline) is a multifaceted, personalized intervention aimed at mitigating cognitive decline and enhancing brain function. It employs a precision medicine approach, tailoring interventions based on individual biochemical, genetic, and lifestyle risk factors associated with neurodegeneration. While primarily designed for individuals with subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and early-stage dementia associated AD, some individuals at more advanced stages have also reported clinical improvements [

23].

This program encompasses a broad range of metabolic and lifestyle domains known to influence cognitive health [

38]. Personalized recommendations are provided in areas such as dietary modifications, physical and cognitive exercise, sleep hygiene, stress reduction techniques, detoxification strategies, targeted supplementation, and hormone regulation. This approach led to the first published reversal of cognitive decline and is based on identifying and mitigating drivers of Alzheimer’s pathophysiology [

10].

Upon completion of initial laboratory tests, cognitive assessments, and medical questionnaires, a computer-based algorithm generates a customized treatment report that pinpoints individual risk contributors—such as systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, nutritional and hormonal imbalances, pathogenic exposures, and genomic predispositions—and identifies various subtypes of AD based on the dominant contributors [

39]. Participants receive detailed guidance from their trained physicians and healthcare teams to help them to address these contributing factors systematically.

Notably, no single causative factor was observed in isolation; rather, several interrelated contributors was identified in all participants [

20,

21]. To support implementation and adherence, participants were encouraged to engage regularly with a health coach, with the dual aim of halting further decline and promoting cognitive recovery while enhancing general well-being [

20,

21].

2.2. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The primary outcome assessed in this study was the severity of depressive symptoms, evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which is a self-administered, 9-item standard assessment point in depression trials [

30,

31,

32] that is frequently used to monitor treatment outcomes [

30]. Extensive validation studies have demonstrated PHQ-9’s strong psychometric properties, including high internal consistency and test-retest reliability [

40,

41,

42]. Furthermore, it has been shown to be a responsive and reliable measure for detecting changes in symptom severity in clinical trials [

43,

44]. Scores for each question (0–3 points) are summed, with a total range of 0–27. Higher scores indicate more severe depression [

45].

2.3. Participants, Assessment and Statistical analysis

In the present study, to cover mild symptoms, improve result sensitivity, and ensure study feasibility, a PHQ-9 score of ≥10 was set as the depression threshold [

45]. There were 170 patients with a PHQ-9 score of ≥10 that took the PHQ-9 test at two time points: baseline (Day 0) and post-treatment (Day 31 or greater).

3. Results

Overall PHQ-9 Score Changes

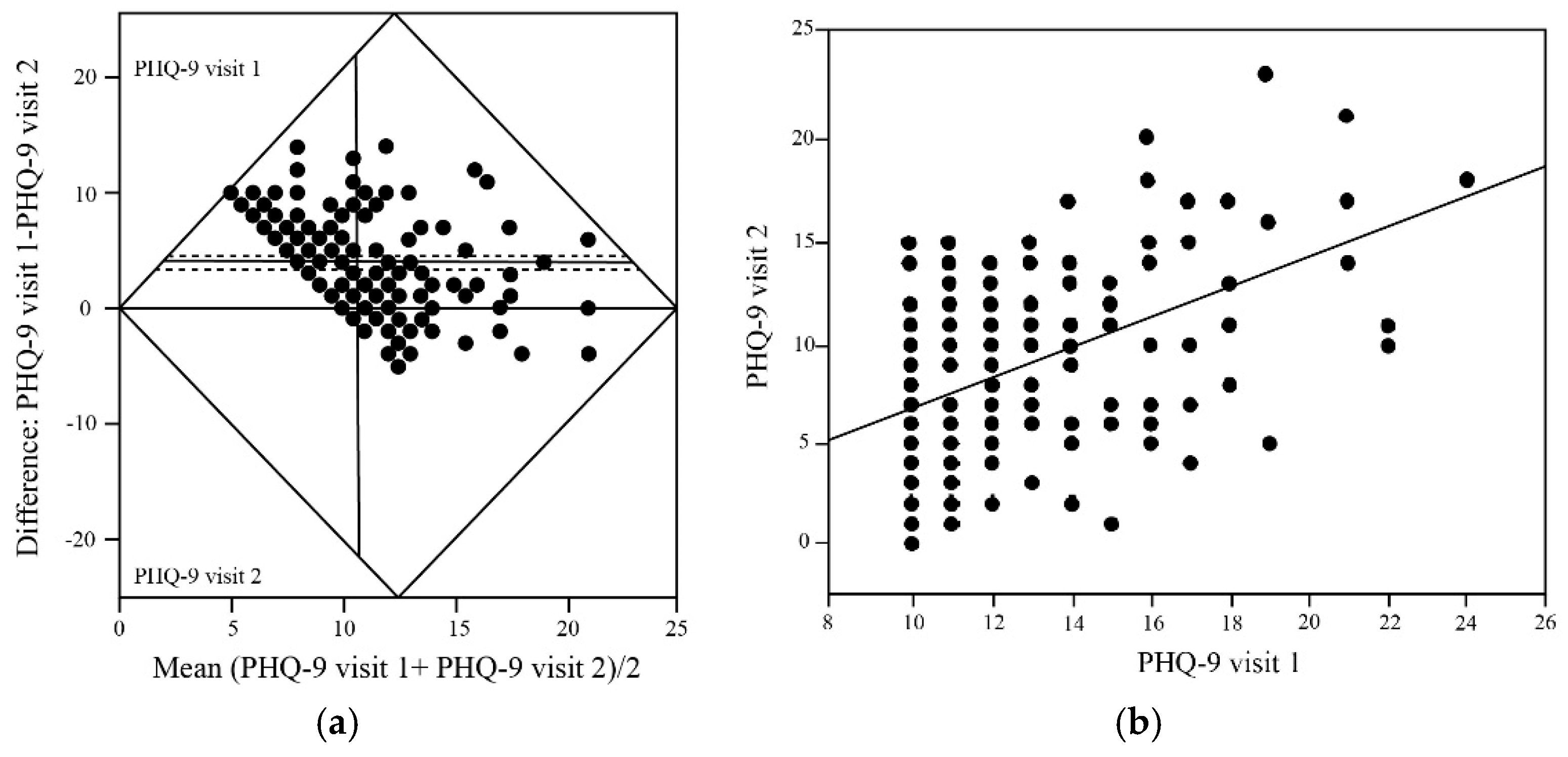

In a cohort of 170 patients who completed PHQ-9 assessments at two time-points spaced at least 31 days apart following adherence to the ReCODE program, there was a statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms. As shown in

Figure 1a, the mean baseline PHQ-9 score was 12.64 ± 5.86, indicating moderate depression severity across the study population. At follow-up, the mean PHQ-9 score decreased significantly to 8.70 ± 5.04, yielding a mean difference of 3.96 points (p < 0.0001), with participants transitioning on average from moderate depression (10-14 range) to mild depression (5-9 range). The fact that most of the data points lie above the zero line and the 95% confidence interval for the mean difference was -4.57 to -3.35, indicates a robust and consistent treatment effect across the population.

Baseline Depression Severity and Treatment Response

Bivariate analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between baseline PHQ-9 scores (visit 1) and follow-up scores (visit 2) as shown in

Figure 1b giving a broader view of group-level trends. A linear regression analysis further supports the observed reduction in depressive symptoms following participation in the ReCODE program. Notably, the regression slope of 0.746 (95% CI) was significantly less than 1.0, indicating that participants with higher baseline depression scores experienced proportionally greater absolute improvements further suggesting that the ReCODE program may be particularly beneficial for individuals with more severe baseline depression.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Depression represents a critical yet, in the context of multi-modal interventions, underexplored therapeutic target in the management of cognitive decline and early-stage AD. It is a prevalent and often underrecognized comorbidity in AD affecting quality of life, caregiver relationships, and functional independence [

33,

34]. Depression can exacerbate cognitive symptoms and is itself influenced by neurodegenerative changes, neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter imbalance, and psychosocial stressors [

35]. The high burden of depression in AD makes it a critical therapeutic target alongside cognition [

36,

37]. While previous investigations of personalized, multi therapeutic approaches have primarily focused on cognitive outcomes and biochemical parameters [

13,

16,

17,

18,

20,

21,

23,

24,

26,

27,

28,

29], the present study addresses a significant gap by examining depression as a primary endpoint.

The ReCODE program is uniquely positioned to address depression because it intervenes simultaneously on multiple physiological and lifestyle domains implicated in mood regulation. The program’s individualized protocols include: nutritional optimization, glycemic control, hormonal balance, sleep optimization, stress reduction and targeted supplementation [

13,

16,

17,

18,

20,

21,

23,

24,

26,

27,

28,

29].

The results from the present study add to the growing body of evidence from studies employing multi-therapeutic approaches to reverse or delay AD-associated dementia by demonstrating a statistically and clinically meaningful reduction in PHQ-9 depression scores over a short intervention period. These improvements were seen across all baseline severity categories, indicating broad benefits. Compared with the modest reductions in PHQ-9 scores typically reported with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) treatment (–2 to –3 points on average, without a clinically meaningful shift in severity category) [

46,

47,

48], the ReCODE intervention yielded a substantially greater mean reduction of nearly 4 points. Notably, participants transitioned from moderate to mild depression, highlighting not only statistical but also clinical significance. The robustness of this effect, supported by a narrow confidence interval and regression analysis showing greater benefits among those with more severe baseline depression, suggests that the ReCODE’s multi-therapeutic approach may have synergistic effects on mood pathways and may confer advantages over conventional pharmacotherapy in improving mood-related symptoms within populations at risk for cognitive decline.

It may be argued that improved mood (lower PHQ-9) could cause a pseudo-cognitive improvement and produce better performance on cognitive screening tests without a true change in underlying brain structure or function. Several lines of evidence argue against this interpretation: (1) Studies from our group and other independent researchers have clearly demonstrated objective, test-based cognitive gains (MoCA and computerized neurocognitive batteries) and sustained cognitive improvement in clinical cohorts treated with ReCODE and similar protocols [

13,

16,

17,

18,

20,

21,

23,

24,

26,

27,

28,

29], (2) Improvements have been observed in imaging biomarkers including regional brain volumetrics on MRI — a biological outcome not readily explained by temporary mood shifts [

13,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], (3) Lab-based biomarker improvements (e.g., reductions in inflammatory markers and improved metabolic indices) and electrophysiological changes reported in precision-medicine cohorts [

13,

16,

17,

18,

20,

21,

23,

24,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Taken together, these objective findings make it unlikely that the cognitive improvements previously reported by us and others are wholly attributable to an antidepressant effect. Thus, the observation that PHQ-9 scores decreased substantially in our cohort therefore should be interpreted as an expected, clinically important additional benefit of addressing the upstream drivers of neurodegeneration.

The PHQ-9, a validated and widely-used depression screening tool, provides a clinically meaningful outcome measure that directly translates to patient well-being and functional capacity [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Although prior studies from our group and others have emphasized the importance of tracking biochemical parameters, our decision to focus here on depression scores in the present manuscript without including biochemical parameters, reflects both methodological considerations and the current state of evidence in this field. The reasons include the following: (1) Previous publications from our research group and others have already established the consistent pattern of metabolic improvements achievable through personalized, multimodal interventions, including reductions in inflammatory markers (hs-CRP), improvements in insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR), optimization of vitamin D levels, and normalization of glucose metabolism [

13,

16,

17,

18,

20,

21,

23,

24,

26,

27,

28,

29]. (2) The present investigation seeks to expand the evidence base beyond metabolic parameters to examine patient-centered outcomes that directly impact quality of life and functional status, (3) Focusing on a single, well-validated outcome measure allows for more rigorous analysis and clearer interpretation of results, avoiding the multiple comparison issues that arise when examining numerous biochemical parameters simultaneously, (4) The PHQ-9's established clinical significance, with defined thresholds for mild, moderate, and severe depression, enables direct translation of research findings into clinical practice guidelines [

30,

45,

49] and (5) Repeating the biochemical assessments would represent redundant data collection and may detract from the central focus of this paper—namely, the value of the ReCODE program in mood improvement. We therefore reference our earlier work for biochemical outcomes, allowing the present manuscript to serve as a complementary analysis that deepens our understanding of the psychosocial dimensions of cognitive recovery.

Our results underscore the ReCODE program’s capacity to deliver meaningful improvements in mood, in addition to the cognitive, biomarker, and neuroimaging benefits reported in earlier work. This supports the hypothesis that depression is not merely an epiphenomenon of neurodegeneration but a modifiable contributor to the disease course. Therefore, monitoring depression symptoms using validated tools like the PHQ-9 may offer a low-cost, easily administered, and clinically meaningful inclusion in tracking treatment response and disease progression in early-stage AD. As the prevalence of AD rises globally, approaches that simultaneously improve cognition, mood, and systemic health are likely to become increasingly valuable. Future randomized controlled trials are warranted to confirm these results and assess the durability of benefits over longer durations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.V.R. and D.E.B.; Methodology, A.B., R.V.R., and D.E.B., Data curation, A.B., R.V.R., S.O., W.L., L.K. and D.E.B., Original draft preparation and Writing, R.V.R, and D.E.B.; Reviewing and Editing, A.B., R.V.R., S.O., W.L, C.C., A.I.B., J.G., L.K. and D.E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was a retrospective, observational analysis of routinely collected clinical data from patients enrolled in the ReCODE program. No experimental intervention beyond standard clinical practice was introduced, and no additional procedures or risks were imposed on participants. All data were de-identified prior to analysis, therefore, did not require institutional review board approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived because this study involved retrospective analysis of de-identified data collected from routine clinical practice and posed no additional risk to participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this manuscript were obtained from patient records and anonymized for publication. These data have not been deposited in a public database.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the coaches for providing support to all the individuals that enroll in the ReCODE program, Laura Lazzarini and Molly Susag for assistance with the manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

DEB is a consultant for Apollo Health and Life Seasons, neither of which was involved in this study or had any access to the study data. AB is the CEO of CNS Vital Signs but was not involved in patient care and management.

References

- El-Hayek, Y.H.; Wiley, R.E.; Khoury, C.P.; Daya, R.P.; Ballard, C.; Evans, A.R.; Karran, M.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Norton, M.; Atri, A. Tip of the Iceberg: Assessing the Global Socioeconomic Costs of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias and Strategic Implications for Stakeholders. J Alzheimers Dis 2019, 70, 323-341. [CrossRef]

- James, B.D.; Leurgans, S.E.; Hebert, L.E.; Scherr, P.A.; Yaffe, K.; Bennett, D.A. Contribution of Alzheimer disease to mortality in the United States. Neurology 2014, 82, 1045-1050. [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer's, A. 2024 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 3708-3821. [CrossRef]

- Yiannopoulou, K.G.; Anastasiou, A.I.; Zachariou, V.; Pelidou, S.H. Reasons for Failed Trials of Disease-Modifying Treatments for Alzheimer Disease and Their Contribution in Recent Research. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 97-112. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Hampel, H.; Feldman, H.H.; Scheltens, P.; Aisen, P.; Andrieu, S.; Bakardjian, H.; Benali, H.; Bertram, L.; Blennow, K.; et al. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease: Definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement 2016, 12, 292-323. [CrossRef]

- Calabro, M.; Rinaldi, C.; Santoro, G.; Crisafulli, C. The biological pathways of Alzheimer disease: a review. AIMS neuroscience 2021, 8, 86-132. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Gao, P.; Shi, L.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Long, J. Central and Peripheral Metabolic Defects Contribute to the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease: Targeting Mitochondria for Diagnosis and Prevention. Antioxid Redox Signal 2020, 32, 1188-1236. [CrossRef]

- Merlo, S.; Spampinato, S.; Canonico, P.L.; Copani, A.; Sortino, M.A. Alzheimer's disease: brain expression of a metabolic disorder? Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM 2010, 21, 537-544. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M.; Iadecola, C. Metabolic and Non-Cognitive Manifestations of Alzheimer's Disease: The Hypothalamus as Both Culprit and Target of Pathology. Cell metabolism 2015, 22, 761-776. [CrossRef]

- Bredesen, D.E. Reversal of cognitive decline: a novel therapeutic program. Aging (Albany NY) 2014, 6, 707-717.

- Theendakara, V.; Peters-Libeu, C.A.; Spilman, P.; Poksay, K.S.; Bredesen, D.E.; Rao, R.V. Direct Transcriptional Effects of Apolipoprotein E. J Neurosci 2016, 36, 685-700. [CrossRef]

- Seto, M.; Weiner, R.L.; Dumitrescu, L.; Hohman, T.J. Protective genes and pathways in Alzheimer's disease: moving towards precision interventions. Mol Neurodegener 2021, 16, 29-44. [CrossRef]

- Schechter, G.; Azad, G.K.; Rao, R.; McKeany, A.; Matulaitis, M.; Kalos, D.M.; Kennedy, B.K. A Comprehensive, Multi-Modal Strategy to Mitigate Alzheimer's Disease Risk Factors Improves Aspects of Metabolism and Offsets Cognitive Decline in Individuals with Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Alzheimer's disease reports 2020, 4, 223-230. [CrossRef]

- Toups, K.; Hathaway, A.; Gordon, D.; Chung, H.; Raji, C.; Boyd, A.; Hill, B.D.; Hausman-Cohen, S.; Attarha, M.; Chwa, W.J.; et al. Precision Medicine Approach to Alzheimer's Disease: Successful Pilot Project. J Alzheimers Dis 2022, 88, 1411-1421. [CrossRef]

- Bredesen, D.E.; Toups, K.; Hathaway, A.; Gordon, D.; Chung, H.; Raji, C.; Boyd, A.; Hill, B.D.; Hausman-Cohen, S.; Attarha, M.; et al. Precision Medicine Approach to Alzheimer's Disease: Rationale and Implications. J Alzheimers Dis 2023, 96, 429-437. [CrossRef]

- Sandison, H.; Callan, N.G.L.; Rao, R.V.; Phipps, J.; Bradley, R. Observed Improvement in Cognition During a Personalized Lifestyle Intervention in People with Cognitive Decline. J Alzheimers Dis 2023. [CrossRef]

- Keawtep, P.; Sungkarat, S.; Boripuntakul, S.; Sa-Nguanmoo, P.; Wichayanrat, W.; Chattipakorn, S.C.; Worakul, P. Effects of combined dietary intervention and physical-cognitive exercise on cognitive function and cardiometabolic health of postmenopausal women with obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2024, 21, 28. [CrossRef]

- Ornish, D.; Madison, C.; Kivipelto, M.; Kemp, C.; McCulloch, C.E.; Galasko, D.; Artz, J.; Rentz, D.; Lin, J.; Norman, K.; et al. Effects of intensive lifestyle changes on the progression of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 122. [CrossRef]

- Thunborg, C.; Wang, R.; Rosenberg, A.; Sindi, S.; Andersen, P.; Andrieu, S.; Broersen, L.M.; Coley, N.; Couderc, C.; Duval, C.Z.; et al. Integrating a multimodal lifestyle intervention with medical food in prodromal Alzheimer's disease: the MIND-AD(mini) randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 118. [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Kumar, S.; Gregory, J.; Coward, C.; Okada, S.; Lipa, W.; Kelly, L.; Bredesen, D.E. ReCODE: A Personalized, Targeted, Multi-Factorial Therapeutic Program for Reversal of Cognitive Decline. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1348-1356. [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Subramaniam, K.G.; Gregory, J.; Bredesen, A.L.; Coward, C.; Okada, S.; Kelly, L.; Bredesen, D.E. Rationale for a Multi-Factorial Approach for the Reversal of Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Disease and MCI: A Review. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 1659-1681. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, N.; Yvon, C. A review of multidomain interventions to support healthy cognitive ageing. The journal of nutrition, health & aging 2013, 17, 252-257. [CrossRef]

- Bredesen, D.E.; Sharlin, K.; Jenkins, D.; Okuno, M.; Youngberg, W.; Cohen, S.H.; Stefani, A.; Brown, R.L.; Conger, S.; Tanio, C.; et al. Reversal of Cognitive Decline: 100 Patients. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Parkinsonism 2018, 8, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Bredesen, D.E.; Amos, E.C.; Canick, J.; Ackerley, M.; Raji, C.; Fiala, M.; Ahdidan, J. Reversal of cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. Aging (Albany NY) 2016, 8, 1250-1258. [CrossRef]

- Kivipelto, M.; Solomon, A.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Antikainen, R.; Backman, L.; Hanninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER): study design and progress. Alzheimers Dement 2013, 9, 657-665. [CrossRef]

- Lista, S.; Dubois, B.; Hampel, H. Paths to Alzheimer's disease prevention: from modifiable risk factors to biomarker enrichment strategies. The journal of nutrition, health & aging 2015, 19, 154-163. [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.K.; Raji, C.; Lokken, K.L.; Bredesen, D.E.; Roach, J.C.; Funk, C.C.; Price, N.; Rappaport, N.; Hood, L.; Heath, J.R. Case Study: A Precision Medicine Approach to Multifactorial Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease & Parkinsonism 2021, 11, 18-36.

- Fotuhi, M.; Lubinski, B.; Trullinger, M.; Hausterman, N.; Riloff, T.; Hadadi, M.; Raji, C.A. A Personalized 12-week "Brain Fitness Program" for Improving Cognitive Function and Increasing the Volume of Hippocampus in Elderly with Mild Cognitive Impairment. The journal of prevention of Alzheimer's disease 2016, 3, 133-137. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.A.; Oughli, H.A.; Lavretsky, H. Complementary and Integrative Medicine for Neurocognitive Disorders and Caregiver Health. Current psychiatry reports 2022, 24, 469-480. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606-613. [CrossRef]

- Levis, B.; Sun, Y.; He, C.; Wu, Y.; Krishnan, A.; Bhandari, P.M.; Neupane, D.; Imran, M.; Brehaut, E.; Negeri, Z.; et al. Accuracy of the PHQ-2 Alone and in Combination With the PHQ-9 for Screening to Detect Major Depression: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2020, 323, 2290-2300. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Levis, B.; Riehm, K.E.; Saadat, N.; Levis, A.W.; Azar, M.; Rice, D.B.; Boruff, J.; Cuijpers, P.; Gilbody, S.; et al. Equivalency of the diagnostic accuracy of the PHQ-8 and PHQ-9: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 1368-1380. [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.; Wang, C.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, X.C.; Yu, J.T.; Tan, L. The prevalence of depression in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Alzheimer Res 2015, 12, 189-198. [CrossRef]

- Dafsari, F.S.; Jessen, F. Depression-an underrecognized target for prevention of dementia in Alzheimer's disease. Translational psychiatry 2020, 10, 160. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ye, T.; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, I.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J. Sex-specific association of depressive symptom trajectories with cognitive decline and clinical progression in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement 2025, 21, e70548. [CrossRef]

- Byers, A.L.; Yaffe, K. Depression and risk of developing dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 2011, 7, 323-331. [CrossRef]

- Wragg, R.E.; Jeste, D.V. Overview of depression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease. A. J. Psychiatry 1989, 146, 577-587. [CrossRef]

- Bredesen, D.E.; John, V. Next generation therapeutics for Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol Med 2013, 5, 795-798. [CrossRef]

- Bredesen, D.E. Metabolic profiling distinguishes three subtypes of Alzheimer's disease. Aging (Albany NY) 2015, 7, 595-600.

- Sun, Y.; Fu, Z.; Bo, Q.; Mao, Z.; Ma, X.; Wang, C. The reliability and validity of PHQ-9 in patients with major depressive disorder in psychiatric hospital. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 474. [CrossRef]

- Levis, B.; Benedetti, A.; Thombs, B.D.; Collaboration, D.E.S.D. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 2019, 365, l1476. [CrossRef]

- Karyotaki, E.; Efthimiou, O.; Miguel, C.; Bermpohl, F.M.G.; Furukawa, T.A.; Cuijpers, P.; Individual Patient Data Meta-Analyses for Depression, C.; Riper, H.; Patel, V.; Mira, A.; et al. Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 361-371. [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, T.; Moore, M.; Leydon, G.; Stuart, B.; Geraghty, A.W.A.; Yao, G.; Lewis, G.; Griffiths, G.; May, C.; Dewar-Haggart, R.; et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for monitoring primary care patients with depression (PROMDEP): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2020, 21, 441. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z. A nurse-led positive psychological intervention among elderly community-dwelling adults with mild cognitive impairment and depression: A non-randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, e5951. [CrossRef]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012, 184, E191-196. [CrossRef]

- Pettit, R.S.; Sakon, C.M.; Kinney, K.E.; Brown, C.; Gallaway, K.A.; Wagner, S.A.; Tillman, E.M. Predictors of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Treatment Failure in Persons With Cystic Fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2025, 60, e27402. [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Lu, J.; Yang, A.; Marsh, E.B. In-hospital predictors of post-stroke depression for targeted initiation of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs). BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 722. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.; Duffy, L.; Ades, A.; Amos, R.; Araya, R.; Brabyn, S.; Button, K.S.; Churchill, R.; Derrick, C.; Dowrick, C.; et al. The clinical effectiveness of sertraline in primary care and the role of depression severity and duration (PANDA): a pragmatic, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 903-914. [CrossRef]

- Kampf-Sherf, O.; Zlotogorski, Z.; Gilboa, A.; Speedie, L.; Lereya, J.; Rosca, P.; Shavit, Y. Neuropsychological functioning in major depression and responsiveness to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors antidepressants. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 82, 453-459. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).