Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Housing

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Radio-frequency Wave Data Collection

2.4. Data Preprocessing

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

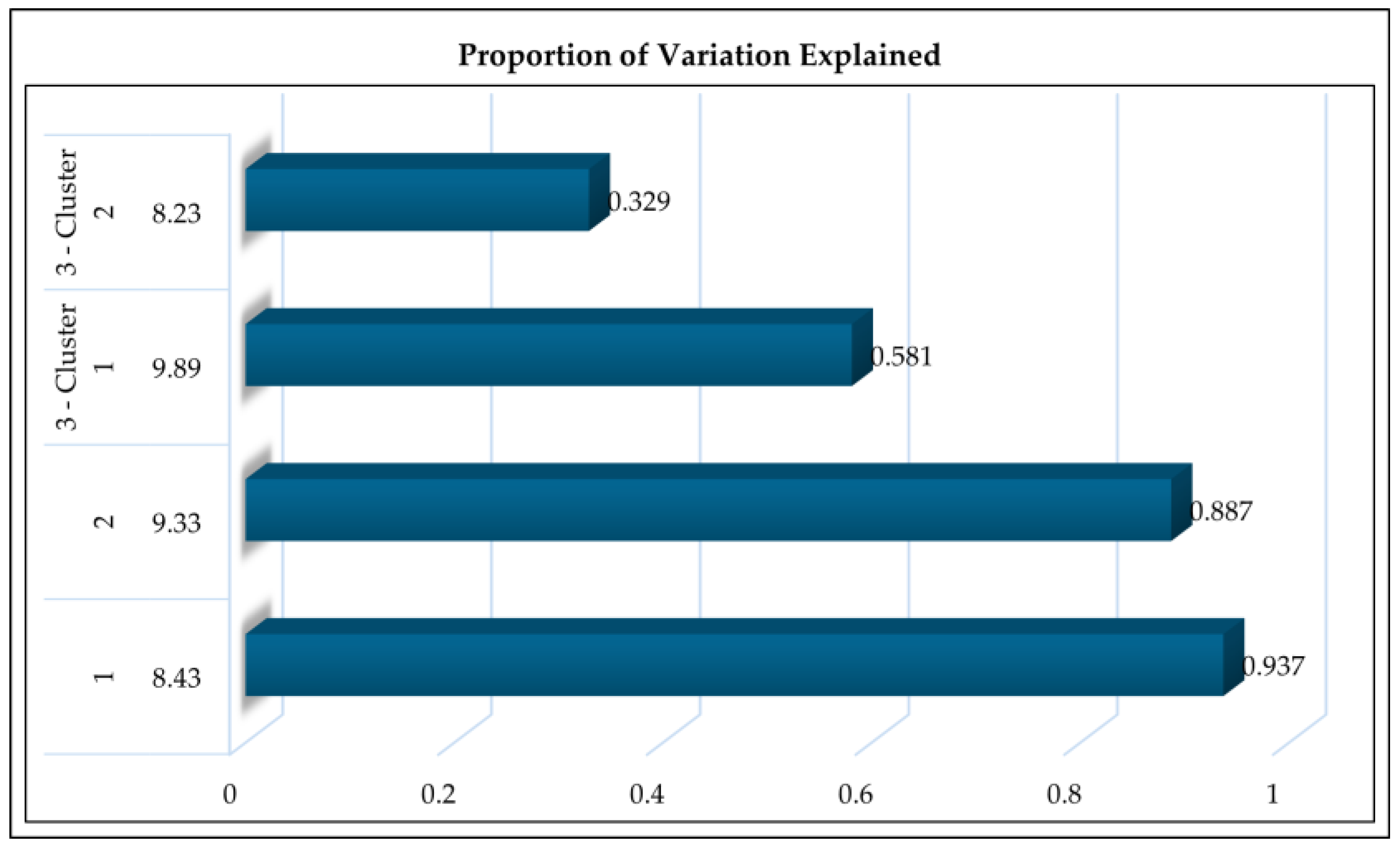

3.1. Variable Clustering

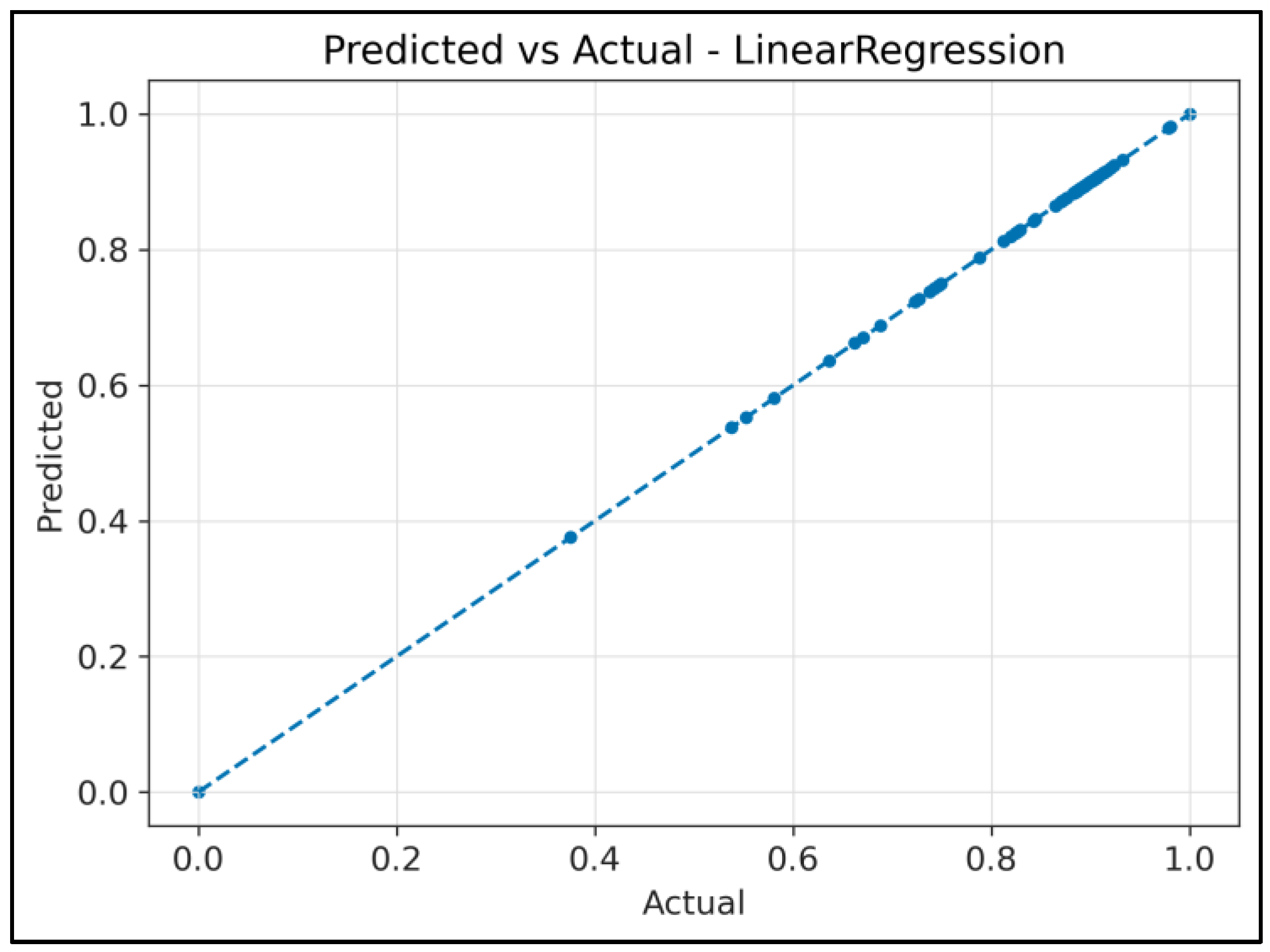

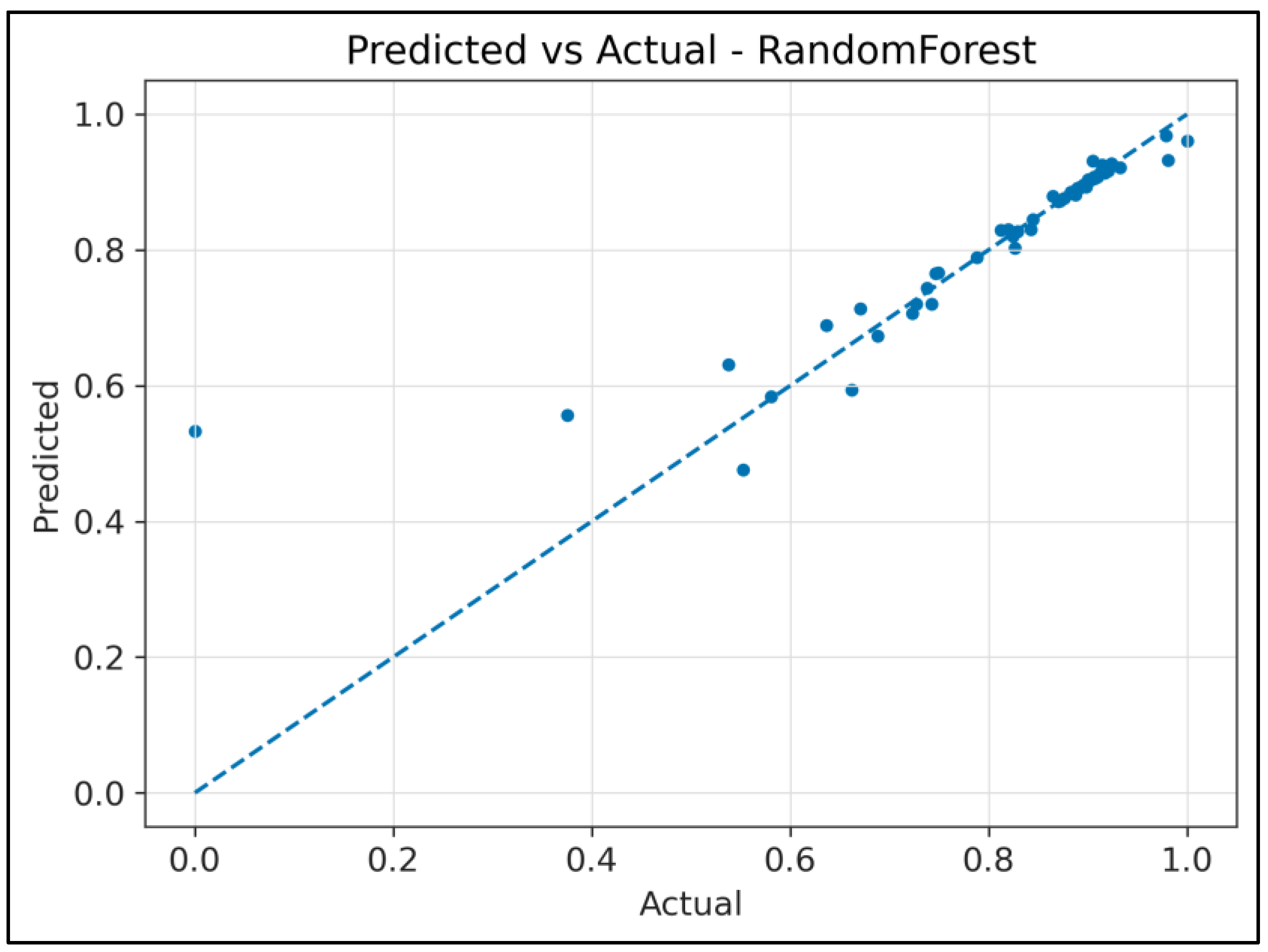

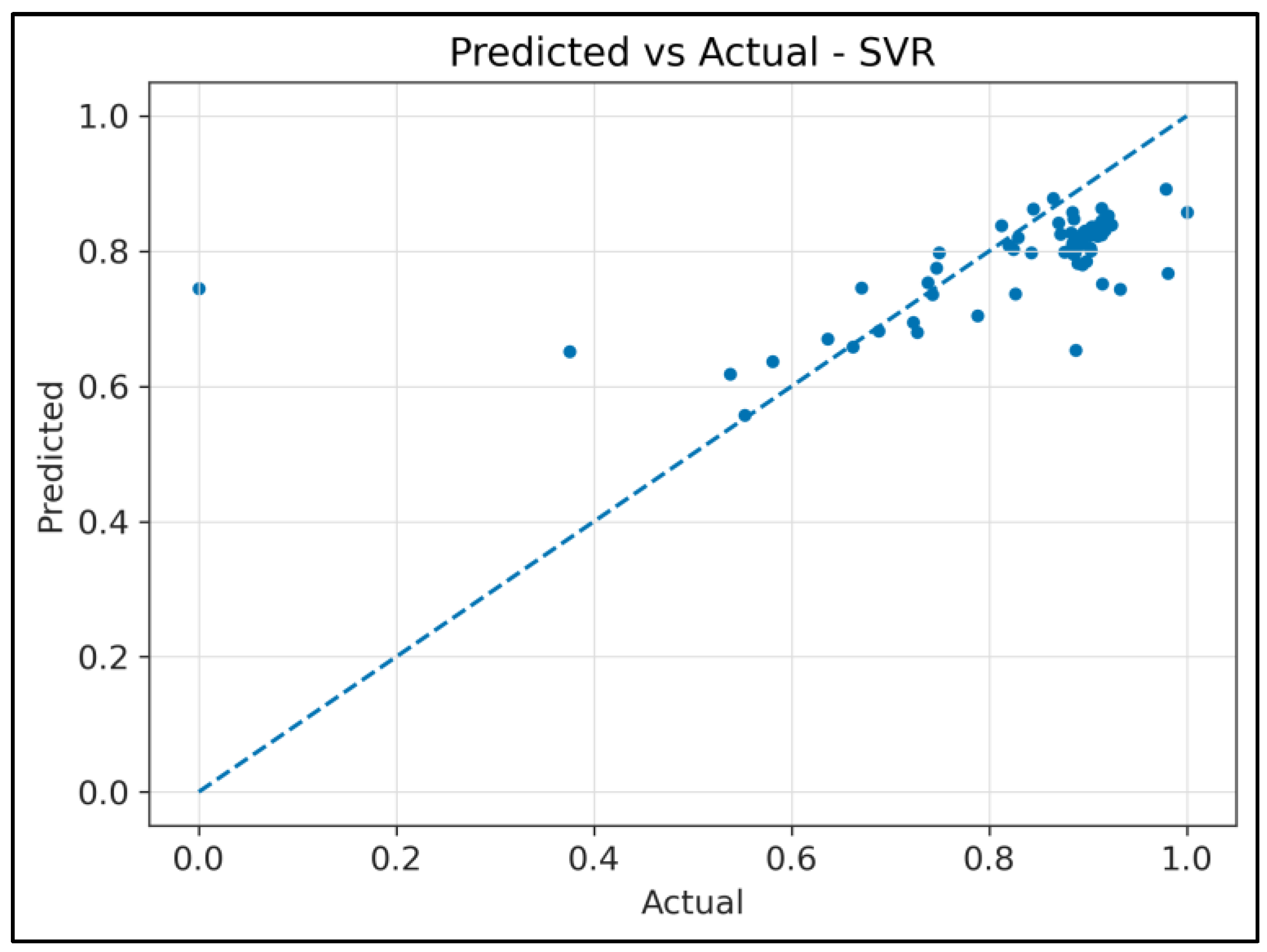

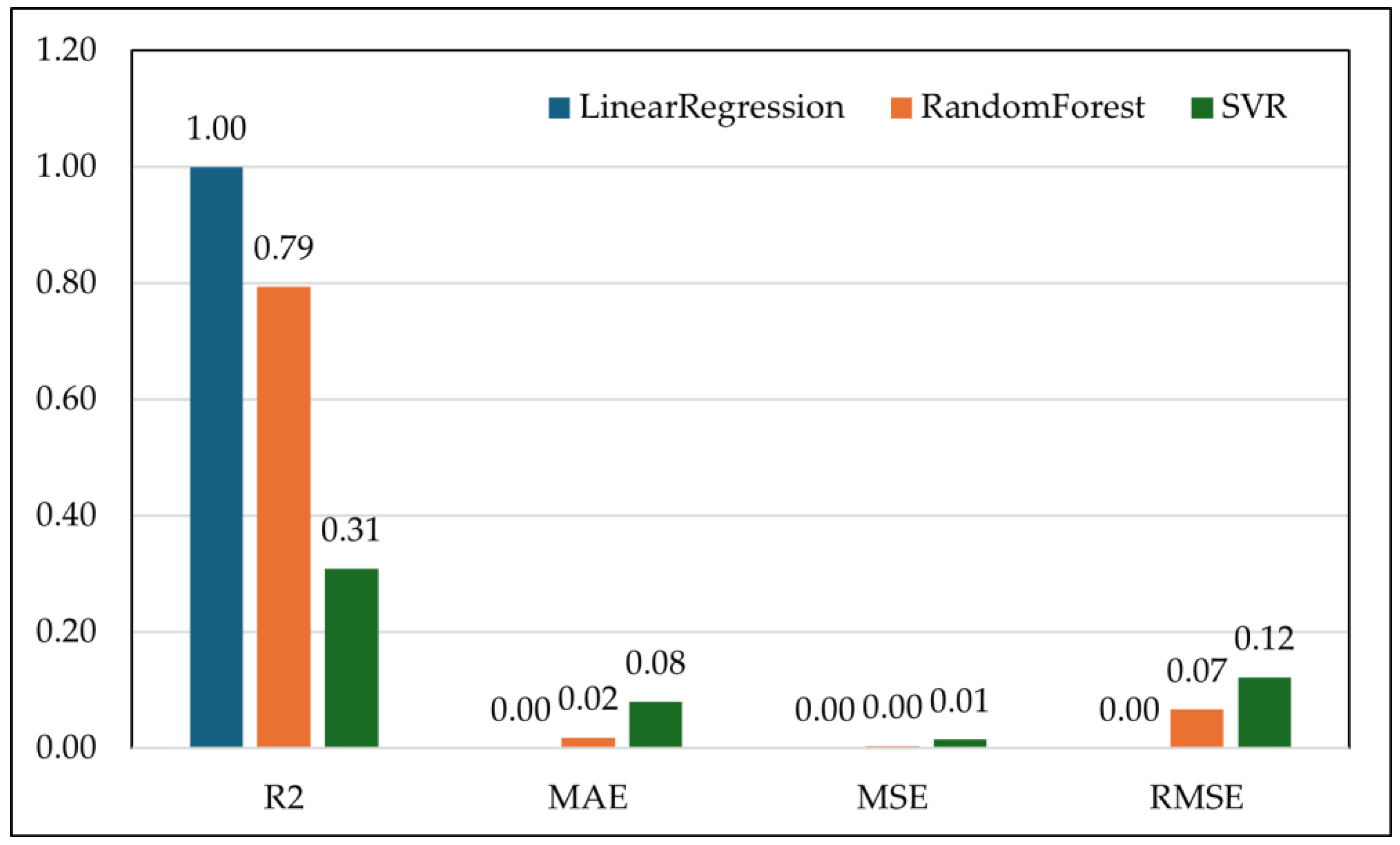

4.2. Regression Analysis: RF Waves Predicting FAMACHA© Scores

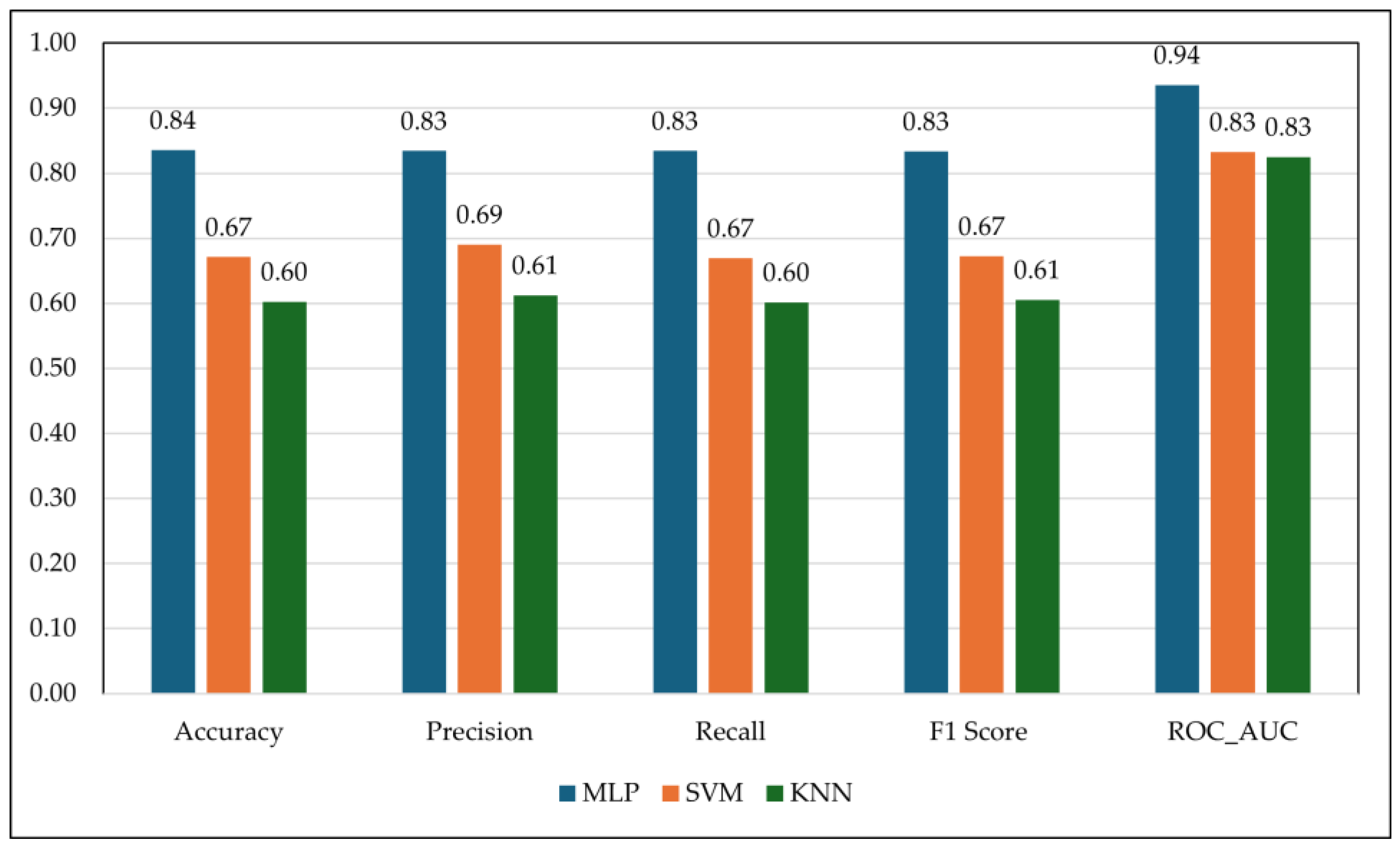

4.3. Classification Analysis: RF waves features for Discrete Animal health Detection

6. Conclusions and Future Research:

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sejian V, Silpa MV, Lees AM, Krishnan G, Devaraj C, Bagath M, Anisha JP, Reshma Nair MR, Manimaran A, Bhatta R, Gaughan JB. Opportunities, challenges, and ecological footprint of sustaining small ruminant production in the changing climate scenario. Agroecological footprints management for sustainable food system. 2020 Dec 17:365-96.

- Lu CD. The role of goats in the world: Society, science, and sustainability. Small Ruminant Research. 2023 Oct 1; 227:107056.

- Fauziah N, Aviani JK, Agrianfanny YN, Fatimah SN. Intestinal parasitic infection and nutritional status in children under five years old: a systematic review. Tropical medicine and infectious disease. 2022 Nov 12;7(11):371.

- Abdalhamed AM, Zeedan GS, Abou Zeina HA. Isolation and identification of bacteria causing mastitis in small ruminants and their susceptibility to antibiotics, honey, essential oils, and plant extracts. Veterinary world. 2018 Mar 26;11(3):355. [CrossRef]

- Dahhir H, Talb O, Asim M. Preliminary study of seroprevalence of border disease virus (bdv) among sheep and goats in mosul city, iraq. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2019;7(7):566-9.

- https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.aavs/2019/7.7.566.569. [CrossRef]

- Paul TK, Rahman MK, Haider MS, Saha SS. Fatal haemonchosis (H. contortus) in Garole sheep at coastal region in Bangladesh. Research in Agriculture Livestock and Fisheries. 2020 Apr 26;7(1):107-12. [CrossRef]

- Getachew T, Alemu B, Sölkner J, Gizaw S, Haile A, Gosheme S, Notter DR. Relative resistance of Menz and Washera sheep breeds to artificial infection with Haemonchus contortus in the highlands of Ethiopia. Tropical animal health and production. 2015 Jun;47(5):961-8. [CrossRef]

- Singh D, Swarnkar CP. Worm control approaches and their impact on status of anthelmintic resistance at an organized sheep farm. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2017 May 1;87(5):568-72.

- Wagener MG, Neubert S, Punsmann TM, Wiegand SB, Ganter M. Relationships between body condition score (BCS), FAMACHA©-score and haematological parameters in alpacas (Vicugna pacos), and llamas (Lama glama) presented at the veterinary clinic. Animals. 2021 Aug 27;11(9):2517.

- Niciura SC, Sanches GM. Machine learning prediction of multiple anthelmintic resistance and gastrointestinal nematode control in sheep flocks. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária. 2024 Mar 18;33(1):e019023. [CrossRef]

- Moreira RT, de Alencar Mota AL, Câmara AC, Soto-Blanco B, Borges JR. FAMACHA©: Predictive value for control of Haemochus sp. in sheep from Brazilian Cerrado. Semina: Ciências Agrárias. 2021 Jul 2;42(5):2825-38. [CrossRef]

- Sajovitz F, Adduci I, Yan S, Wiedermann S, Tichy A, Joachim A, Wittek T, Hinney B, Lichtmannsperger K. Correlation of Faecal Egg Counts with Clinical Parameters and Agreement between Different Raters Assessing FAMACHA©, BCS and Dag Score in Austrian Dairy Sheep. Animals. 2023 Oct 13;13(20):3206. [CrossRef]

- Singh D, Swarnkar CP. Worm control approaches and their impact on status of anthelmintic resistance at an organized sheep farm. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2017 May 1;87(5):568-72. [CrossRef]

- Walker JG, Ofithile M, Tavolaro FM, van Wyk JA, Evans K, Morgan ER. Mixed methods evaluation of targeted selective anthelmintic treatment by resource-poor smallholder goat farmers in Botswana. Veterinary Parasitology. 2015 Nov 30;214(1-2):80-8. [CrossRef]

- Rebez EB, Sejian V, Silpa MV, Kalaignazhal G, Thirunavukkarasu D, Devaraj C, Nikhil KT, Ninan J, Sahoo A, Lacetera N, Dunshea FR. Applications of artificial intelligence for heat stress management in ruminant livestock. Sensors. 2024 Sep 11;24(18):5890.

- Mehrotra P, Chatterjee B, Sen S. EM-wave biosensors: A review of RF, microwave, mm-wave and optical sensing. Sensors. 2019 Feb 27;19(5):1013.

- Vander Vorst A, Rosen A, Kotsuka Y, Djajaputra D. RF/microwave interaction with biological tissues. Medical Physics. 2007 Feb 1;34(2):786-7.

- O’Brien C, Alamar MC. An overview of non-destructive technologies for postharvest quality assessment in horticultural crops. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology. 2025 Apr 14:1-9.

- Siddique A, Gupta A, Sawyer J, Garner LJ, Morey A. Rapid detection of poultry meat quality using S-band to KU-band radio-frequency waves combined with machine learning—A proof of concept. Journal of Food Science. 2024 Dec;89(12):9608-21.

- Origlia C, Rodriguez-Duarte DO, Tobon Vasquez JA, Bolomey JC, Vipiana F. Review of microwave near-field sensing and imaging devices in medical applications. Sensors. 2024 Jul 12;24(14):4515.

- Nie L. , Berckmans D. , Wang C. , & Li B.. Is continuous heart rate monitoring of livestock a dream or is it realistic? a review. Sensors 2020;20(8):2291. [CrossRef]

- Khunteta S. , Saikrishna P. , Agrawal A. , Kumar A. , & Chavva A.. Rf-sensing: a new way to observe surroundings. IEEE Access 2022;10:129653-129665. [CrossRef]

- Dayoub M. , Shnaigat S. , Tarawneh R. , Al-Yacoub A. , Al-Barakeh F. , & Al-Najjar K.. Enhancing animal production through smart agriculture: possibilities, hurdles, resolutions, and advantages. Ruminants 2024;4(1):22-46. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt C. , Henderson S. , Brzozek C. , & Benke G.. Instruments to measure environmental and personal radiofrequency-electromagnetic field exposures: an update. Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine 2022;45(3):687-704. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair M. , Zhang Y. , Descovich K. , & Phillips C.. Farm animal welfare science in china—a bibliometric review of chinese literature. Animals 2020;10(3):540. [CrossRef]

- Balehegn M. , Duncan A. , Tolera A. , Ayantunde A. , Issa S. , Karimou M. et al.. Improving adoption of technologies and interventions for increasing supply of quality livestock feed in low- and middle-income countries. Global Food Security 2020;26:100372. [CrossRef]

- Kopler I. , Marchaim U. , Tikász I. , Opaliński S. , Kokin E. , Mallinger K. et al.. Farmers’ perspectives of the benefits and risks in precision livestock farming in the eu pig and poultry sectors. Animals 2023;13(18):2868. [CrossRef]

- Adesogan AT, Gebremikael MB, Varijakshapanicker P, Vyas D. Climate-smart approaches for enhancing livestock productivity, human nutrition, and livelihoods in low-and middle-income countries. Animal Production Science. 2025 Apr 14;65(6).

- Lhermie G. , Pica-Ciamarra U. , Newman S. , Raboisson D. , & Waret-Szkuta A.. Impact of peste des petits ruminants for sub-saharan african farmers: a bioeconomic household production model. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2021;69(4). [CrossRef]

- Al-Salihi K.. The epidemiology of foot-and-mouth disease outbreaks and its history in iraq. Veterinary World 2019;12(5):706-712. [CrossRef]

- Fu L. , Wang L. , Liu L. , Zhang L. , Zhou Z. , Zhou Y. et al.. Effects of inoculation with active microorganisms derived from adult goats on growth performance, gut microbiota and serum metabolome in newborn lambs. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Bogomolov M, Peterson CB, Benjamini Y, Sabatti C. Hypotheses on a tree: new error rates and testing strategies. Biometrika. 2021 Sep 1;108(3):575-90.

- Rahman MS, Al-Farsi K, Al-Maskari SS, Al-Habsi NA. Stability of electronic nose (e-nose) as determined by considering date-pits heated at different temperatures. International journal of food properties. 2018 Jan 1;21(1):850-7.

- Burke JM, Kaplan RM, Miller JE, Terrill TH, Getz WR, Mobini S, Valencia E, Williams MJ, Williamson LH, Vatta AF. Accuracy of the FAMACHA system for on-farm use by sheep and goat producers in the southeastern United States. Veterinary parasitology. 2007 Jun 20;147(1-2):89-95.

- Van Wyk JA, Bath GF. The FAMACHA system for managing haemonchosis in sheep and goats by clinically identifying individual animals for treatment. Veterinary research. 2002 Sep 1;33(5):509-29.

- Bhagat RC, Patil SS. Enhanced SMOTE algorithm for classification of imbalanced big-data using random forest. In2015 IEEE international advance computing conference (IACC) 2015 Jun 12 (pp. 403-408). IEEE.

- Wang S, Dai Y, Shen J, Xuan J. Research on expansion and classification of imbalanced data based on SMOTE algorithm. Scientific reports. 2021 Dec 15;11(1):24039.

- Blagus R, Lusa L. SMOTE for high-dimensional class-imbalanced data. BMC bioinformatics. 2013 Mar 22;14(1):106.

- Hussin SK, Abdelmageid SM, Alkhalil A, Omar YM, Marie MI, Ramadan RA. Handling imbalance classification virtual screening big data using machine learning algorithms. Complexity. 2021;2021(1):6675279.

- Yates LA, Aandahl Z, Richards SA, Brook BW. Cross validation for model selection: a review with examples from ecology. Ecological Monographs. 2023 Feb;93(1):e1557.

- Malakouti SM. Babysitting hyperparameter optimization and 10-fold-cross-validation to enhance the performance of ML methods in predicting wind speed and energy generation. Intelligent Systems with Applications. 2023 Sep 1; 19:200248.

- Ali H, Muthudoss P, Chauhan C, Kaliappan I, Kumar D, Paudel A, Ramasamy G. Machine learning-enabled NIR spectroscopy. Part 3: hyperparameter by design (HyD) based ANN-MLP optimization, model generalizability, and model transferability. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2023 Dec 7;24(8):254.

- Grefenstette E, Amos B, Yarats D, Htut PM, Molchanov A, Meier F, Kiela D, Cho K, Chintala S. Generalized inner loop meta-learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.01727. 2019 Oct 3.

- Srinivasan DV, Moradi M, Komninos P, Zarouchas D, Vassilopoulos AP. A generalized machine learning framework to estimate fatigue life across materials with minimal data. Materials & Design. 2024 Oct 1; 246:113355.

- Ley S. , Schilling S. , Fišer O. , Vrba J. , Sachs J. , & Helbig M.. Ultra-wideband temperature dependent dielectric spectroscopy of porcine tissue and blood in the microwave frequency range. Sensors 2019;19(7):1707. [CrossRef]

- Spliethoff J. , Tanis E. , Evers D. , Hendriks B. , Prevoo W. , & Ruers T.. Monitoring of tumor radio frequency ablation using derivative spectroscopy. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2014;19(9):097004. [CrossRef]

- Antanaitis R. , Džermeikaitė K. , Krištolaitytė J. , Stankevičius R. , Daunoras G. , Televičius M. et al.. Changes in parameters registered by innovative technologies in cows with subclinical acidosis. Animals 2024;14(13):1883. [CrossRef]

- Meyer JP, McAvoy KE, Jiang J. Rehydration capacities and rates for various porcine tissues after dehydration. PLoS One. 2013 Sep 4;8(9):e72573.

- Gong A, Wei X, Liu Y, Chen Z, Fan B, Jia A, Wu S. SSA-sMLP: A venous thromboembolism risk prediction model using separable self-attention and spatial-shift multilayer perceptrons. Thrombosis Research. 2025 May 6:109334.

- Huan R, Ji L, Lu H, Zheng S, Chen P, Liang R. MUDIFEI: Multi-dimensional Feature Extraction and Interaction Model for Human Transition Action Recognition based on Sensor Data. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2025 Jul 23(99):1-.

- Poddar H. From neurons to networks: Unravelling the secrets of artificial neural networks and perceptrons. InDeep Learning in Engineering, Energy and Finance 2024 Dec 26 (pp. 25-79). CRC Press.

- Rahman MM. A Deep Learning Approach for Computational Electromagnetics. McGill University (Canada); 2023.

- Ayodele B. , Mustapa S. , Kanthasamy R. , Zwawi M. , & Cheng C.. Modeling the prediction of hydrogen production by co-gasification of plastic and rubber wastes using machine learning algorithms. International Journal of Energy Research 2021;45(6):9580-9594. [CrossRef]

- Taki O. , Rhazi K. , & Mejdoub Y.. Stirling engine optimization using artificial neural networks algorithm. ITM Web of Conferences 2023;52:02010. [CrossRef]

- Santorelli A, Abbasi B, Lyons M, Hayat A, Gupta S, O’Halloran M, Gupta A. Investigation of anemia and the dielectric properties of human blood at microwave frequencies. IEEE Access. 2018 Oct 2;6:56885-92.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).