Submitted:

20 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology of Myocarditis

1.2. Diagnostic Work-Ups

1.3. Natural Course of Myocarditis

1.4. Elimination of the Pathogen Versus Progression to Chronic Active Inflammation

2. An illustrative Case Report

3. Discussion and Literature Review

3.1. Myocarditis Caused by Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) and Opportunistic Bacterial Streptococcus pneumoniae Infection: A Brief Literature Review

3.2. Progression from Acute to Chronic Active Myocarditis

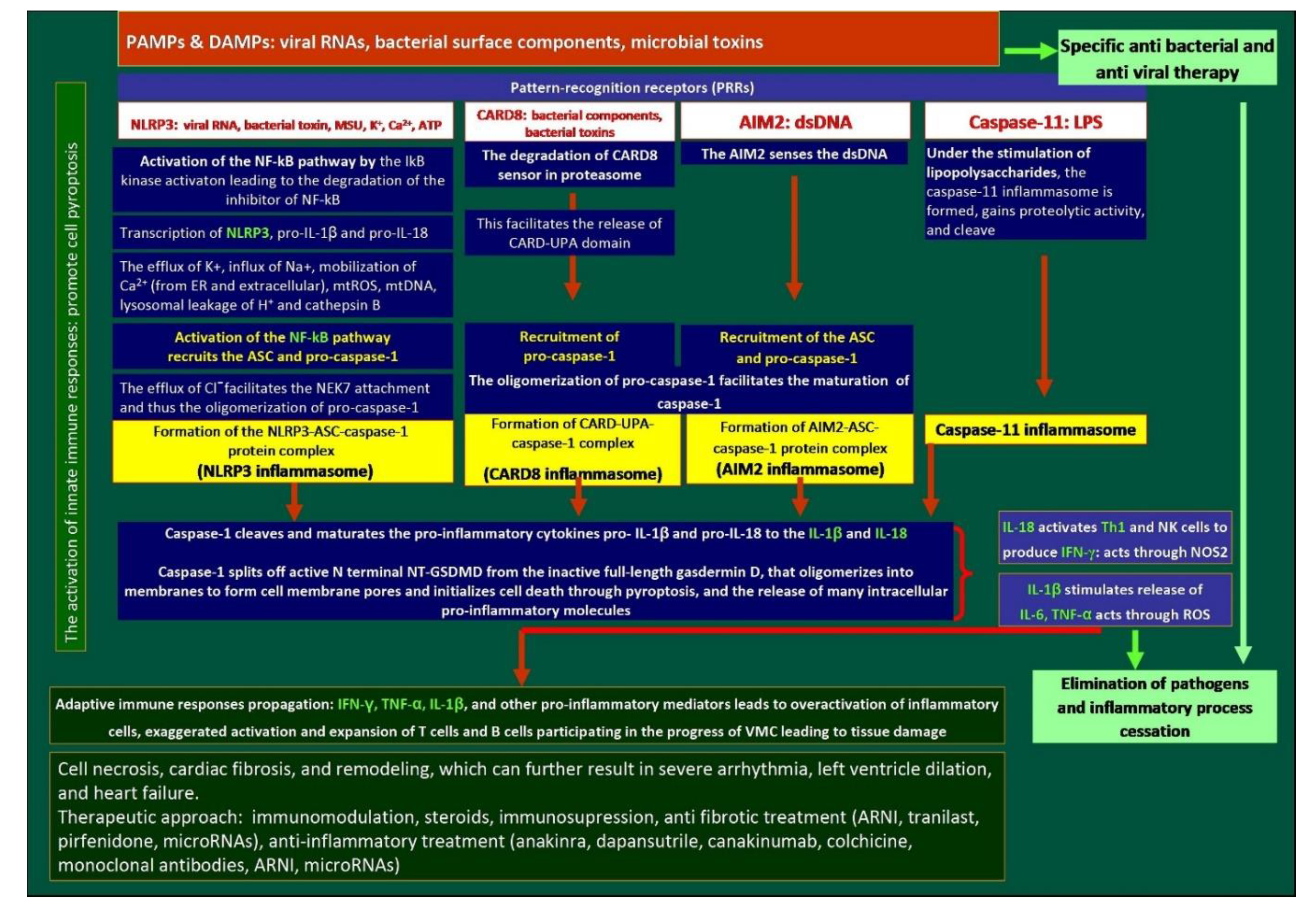

3.3. Role of Inflammasomes in Myocarditis

3.3.1. The NLRP3 Pathway

3.3.2. CARD8 Pathway

3.3.3. AIM2 Pathway

3.3.4. Caspase-11 Inflammasome

3.4. Post-Infectious Phase

3.5. Therapeutic Approaches in VMC Based on Pathogen and Disease Phase

3.5.1. Specific Antiviral Therapy in Acute Phase of Myocarditis

3.5.2. Immunosuppression in Active and Chronic Active Myocarditis

3.6. Targeting Inflammasomes: A Future for Myocarditis?

3.6.1. Inhibition of NF-κB Pathway

3.6.2. Direct NLRP3 Inhibitors

3.6.3. Colchicine

3.6.4. Dapansutrile (OLT1177)

3.6.5. INF200

3.6.6. Canakinumab

3.6.7. Anakinra and IL-1 Receptor Accessory Protein Monoclonal Antibody

3.6.8. Monoclonal Antibodies and Drugs Targeting IL-18

3.7. Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor (ARNI)

3.7.1. Off-Label Use of ARNI

3.7.2. ARNI in Acute Myocardial Infarction: RCT Results

3.7.3. ARNI in Doxorubicin-Induced DCM

3.7.4. Potential of ARNIs in Acute Myocarditis: A Review of the Literature

3.8. Role of Cardiac Fibrosis and Anti-fibrotic Treatment Approaches

3.9. MicroRNAs in VMC

| Study | Pathogen | microRNA | Down vs Up-regulated |

Rationale for use of individual microRNA | Therapeutic approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goldberg et al. 2018 [223] | enteroviral, adenoviral or parvoviral B19 myocarditis | miR-208a, miR-208b, miR-499, and miR-21 | Up or Down | upward or downward dynamics depending on the phase of infection | No data |

| Gong et al. 2023 [228] |

miR-21 |

Down | miR-21 downregulation protects myocardial cells against LPS-induced apoptosis and inflammation through Rcan1 signaling | No data | |

| Li et al. 2022 [229] | miR-21 | Down | miR-21 downregulation protects myocardial cells against LPS-induced apoptosis and inflammation by targeting Bcl-2 and CDK6 | No data | |

| Yang et al. 2018 [230] | miR-21 | Down | miR-21 deficiency promoted inflammatory cytokine production and worsened cardiac function in cardiac ischemia through targeting KBTBD7 | No data | |

| Bao et al. 2014 [234] | Coxsackie B3 myocarditis | miR-155, miR-148 | Up | miR-155 and miR-148a were shown to reduce cardiac injury during acute phase in humans by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway | miR-155 reduced cardiac myoblast cytokines expression. Increased survival in miR-155 treated mice |

| Corsten MF et al. 2012 [235] | CVB3 myocarditis in humans and susceptible mice | miR-155, miR-146b, miR-21 | Up | Inhibition of miR-155 by a systemically delivered LNA-anti-miR attenuated cardiac infiltration by monocyte-macrophages, decreased T lymphocyte activation, and reduced myocardial damage during acute myocarditis in mice | LNA-anti-miR-155 may reduce inflammation activity in mice with CVB3 |

| Zhang Y, et al 2016 [236] |

CVB3 myocarditis | miR-155 | Up | miR-155 is upregulated in CVB3 myocarditis, and localized primarily in heart-infiltrating macrophages and CD4+ T lymphocytes, promoting macrophage polarization to pro inflammatory M1. Silencing miR-155 led to increased levels of alternatively-activated macrophages (anti-inflammatory M2) | miR-155 may be a potential therapeutic target for VMC |

| Liu et al. 2013 [237] |

CVB3 myocarditis | miR-146b | Up | miR-146b was highly expressed in mice with CVB3. Its inhibition reduced inflammatory lesions and suppressed Th17 cells differentiation. | inhibiting miR-146b may lead to a reduction in the severity of myocarditis |

| Blanco-Domínguez et al. [239] | A murine model of viral/autoimmune myocarditis in mice | miR-721 | Up | Increased expression levels of miR-721 in a murine model of viral/autoimmune myocarditis. miR-721, synthesized by Th17 cells, was detectable in the plasma of mice with myocarditis but absent in infarcted mice. A murine model of viral/autoimmune myocarditis in mice | antagomir-miR-721: potential to silence Th17 cells and thus suppress inflammatory pathways in VMC |

| Li, J. et al. 2021 [240] | CVB3-infected mice | miR-425-3p | Up | Reduction in IL-6, IL-12, TNF-α in VMC mice treated with miR-425-3p compared to non-treated VMC mice | MiR-425-3p inhibits myocardial inflammation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in CVB3 myocarditis |

| Li W et al. 2020 [241] | CVB3-infected mice | miR-1/133a | Up | miR-1/133 mimics up-regulated the expression of miR-1 and miR-133, the potassium channel genes Kcnd2 and Kcnj2, as well as Bcl-2, and down-regulated the expression of the potassium channel suppressor gene Irx5, L-type calcium channel subunit gene a1c (Cacna1c), Bax, and caspase-9 in the myocardium of VMC mice. MiR-1/133 also up-regulated the protein levels of Kv4.2 and Kir2.1, and down-regulated the expression of CaV1.2 |

miR-1/133 mimics attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis and electrical remodeling in mice with VMC |

| Deng et al., 2014 [244] | hMPV infection |

142 miRs upregulated 32 miRs downregulated let-7f |

Up Down Up |

let-7f was significantly upregulated and exhibited antiviral effects: its inhibitors increased viral replication | Let-7f mimics reduced viral replication |

| Wu et al., 2020 [245] | hMPV infection | miR-16, miR-30a | Up | miR-16 regulation depended on type I IFN signaling, whereas miR-30a was IFN independent, suggesting potential therapeutic targets | No data |

| Martínez-Espinoza et al. 2023 [246] | hMPV infection | miR-4634 | Up | hsa-miR-4634 enhances viral immune evasion by inhibiting type I IFN responses and IFN-stimulated genes, increasing viral replication in macrophages and epithelial cells | No data |

| Srivastava et al. 2023 [247] | SARS-CoV-2 | miR-335-3p | Up | miR-335-3p expression level predicted COVID infection severity | No data |

| Salvado et al 2025 [248] | Parvovirus B19 |

miR-4799-5p, miR-5690, miR-335-3p, miR-193b-5p, and miR-6771-3p were highly expressed in the B19V transcripts | Up | promising biomarkers of infection progression | No data |

| Eilam-Frenkel et al 2018 [249] | Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) |

miR-146a let-7c, miR-345, miR-221 |

Up Down |

miR-146a-5p were up-regulated, whereas let-7c, miR-345-5p, and miR-221 were downregulated by prolonged RSV infection | No data |

| Zhang Y et al. 2016 [250] | Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) | miR-29a | Up | Respiratory syncytial virus non-structural protein 1 facilitates virus replication through miR-29a-mediated inhibition of IFN-alpha receptor. | No data |

| Chen et al. 2022 [251] | Fulminant myocarditis | miR-29b, miR-125b | Up | miR-29b demonstrated higher sensitivity and specificity for the fulminant myocarditis. Upregulation of miR-29b and miR-125b in plasma of patients with fulminant myocarditis positively correlated with the area of myocardial edema and was negatively correlated with the LVEF. | No data |

| Taubel et al., 2021 [254] | HF | miR-132 | Up | Randomized, phase 1b controlled trial evaluating the impact of CDR132L (antagomir-miR-132) on cardiac function over 3 months in a chronic HF model. Treatment with CDR132L significantly improved systolic and diastolic cardiac function, reduced cardiac fibrosis, and attenuated adverse remodeling | Demonstrated the therapeutic potential of targeting microRNA-132 for HF management |

| HF-REVERT, 2025 [255] | HF after myocardial infarction | miR-132 | Up | Randomized, phase 2, controlled study in patients with HFrEE following myocardial infarction showed safety of antagomir-132 treatment, without the effect on left ventricular remodeling | Demonstrated safety of the treatment with antagomir-132 |

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ammirati, E. , Moslehi J.J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Myocarditis. JAMA. 2023;329:1098. [CrossRef]

- Golpour, A.; Patriki, D.; Hanson, P.J.; McManus, B.; Heidecker, B. Epidemiological Impact of Myocarditis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brociek E, Tymińska A, Giordani AS, Caforio AL, Wojnicz R, Grabowski M, Ozierański K. Myocarditis: Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Their Implications in Clinical Practice. Biology. 2023;12:874. [CrossRef]

- Pollack, A. , Kontorovich A.R., Fuster V., Dec G.W. Viral myocarditis—diagnosis, treatment options, and current controversies. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015;12:670. [CrossRef]

- Caforio AL, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(33):2636-2648d. [CrossRef]

- Bacterial cardiomyopathy: A review of clinical status and meta-analysis of diagnosis and clinical management. Trends in Research 2019, 2(3). [CrossRef]

- Tschöpe, C. , Ammirati, E., Bozkurt, B., Caforio, A. L. P., Cooper, L. T., Felix, S. B., Hare, J. M., Heidecker, B., Heymans, S., Hübner, N., Kelle, S., Klingel, K., Maatz, H., Parwani, A. S., Spillmann, F., Starling, R. C., Tsutsui, H., Seferovic, P., Van Linthout, S. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: current evidence and future directions. Nature reviews. Cardiology, 2021, 18(3), 169–193. [CrossRef]

- Golpour, A.; Patriki, D.; Hanson, P.J.; McManus, B.; Heidecker, B. Epidemiological Impact of Myocarditis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordani, A.S.; Simone, T.; Baritussio, A.; Vicenzetto, C.; Scognamiglio, F.; Donato, F.; Licchelli, L.; Cacciavillani, L.; Fraccaro, C.; Tarantini, G.; et al. Hydrocarbon Exposure in Myocarditis: Rare Toxic Cause or Trigger? Insights from a Biopsy-Proven Fulminant Viral Case and a Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauwet, L.A. , Cooper L.T. Antimicrobial agents for myocarditis: Target the pathway, not the pathogen. Heart. 2009;96:494–495. [CrossRef]

- Siripanthong, B. , Nazarian, S., Muser, D., Deo, R., Santangeli, P., Khanji, M. Y., Cooper, L. T., Jr, & Chahal, C. A. A. Recognizing COVID-19-related myocarditis: The possible pathophysiology and proposed guideline for diagnosis and management. Heart rhythm, 2020, 17(9), 1463–1471. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. , Dai, Z., Mo, P., Li, X., Ma, Z., Song, S., Chen, X., Luo, M., Liang, K., Gao, S., Zhang, Y., Deng, L., Xiong, Y. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Older Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China: A Single-Centered, Retrospective Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(9):1788-1795. [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, E; Lupi, L; Palazzini, M; et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes of COVID-19 associated acute myocarditis. Circulation 2022, 145, 1123–1139.

- Zuin, M. , Rigatelli, G., Bilato, C., Porcari, A., Merlo, M., Roncon, L., Sinagra, G. One-Year Risk of Myocarditis After COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2023; 39(6): 839-844. [CrossRef]

- Magyar K, Halmosi R, Toth K, Alexy T. Myocarditis after COVID-19 and influenza infections: insights from a large data set. Open Heart. 2024 Nov 14;11(2):e002973. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen B, Prasad V. COVID-19 vaccine induced myocarditis in young males: A systematic review. Eur J Clin Invest. 2023;53(4):e13947. [CrossRef]

- Yao Z, Liang M, Zhu S. Infectious factors in myocarditis: a comprehensive review of common and rare pathogens. Egypt Heart J. 2024;76(1):Published 2024. 24 May. [CrossRef]

- Dion CF, Ashurst JV. Streptococcus pneumoniae. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; , 2023. 8 August.

- Brown, A. O. , Mann, B., Gao, G., Hankins, J. S., Humann, J., Giardina, J., Faverio, P., Restrepo, M. I., Halade, G. V., Mortensen, E. M., et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae Translocates into the Myocardium and Forms Unique Microlesions That Disrupt Cardiac Function. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(9):ePublished 2014 Sep 18. [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, A.T. , Orihuela, C. J. Anatomical site-specific contributions of pneumococcal virulence determinants. Pneumonia 2016, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H. , Kruckow, K. L., D'Mello, A., Ganaie, F., Martinez, E., Luck, J. N., Cichos, K. H., Riegler, A. N., Song, X., Ghanem, E., Saad, J. S., Nahm, M. H., Tettelin, H., & Orihuela, C. J. Anatomical Site-Specific Carbohydrate Availability Impacts Streptococcus pneumoniae Virulence and Fitness during Colonization and Disease. Infect Immun. 2022;90(1):e0045121. [CrossRef]

- Piazza, I.; Ferrero, P.; Marra, A.; Cosentini, R. Early Diagnosis of Acute Myocarditis in the ED: Proposal of a New ECG-Based Protocol. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazner, M, Bozkurt, B. et al. 2024 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Strategies and Criteria for the Diagnosis and Management of Myocarditis: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. JACC. 2025 Feb, 85 (4) 391–431. doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2024.10.

- Ramantauskaitė, G; Okeke, K.A.; Mizarienė, V. Myocarditis: Differences in Clinical Expression between Patients with ST-Segment Elevation in Electrocardiogram vs. Patients without ST-Segment Elevation. J Pers Med. 2024 Oct 13;14(10):1057. [CrossRef]

- Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(37):3503-3626. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S. , Li, C., Amarasekera, A. T., Bhat, A., Chen, H. H. L., Gan, G. C. H., & Tan, T. C. Echocardiographic parameters of cardiac structure and function in the diagnosis of acute myocarditis in adult patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Echocardiography. 2024;41(2):e15760. [CrossRef]

- Supeł, K.; Wieczorkiewicz, P.; Przybylak, K.; Zielińska, M. 2D Strain Analysis in Myocarditis—Can We Be Any Closer to Diagnose the Acute Phase of the Disease? J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudar I, Aichouni N, Nasri S, Kamaoui I, Skiker I. Diagnostic criteria for myocarditis on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: an educational review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85(8):3960-Published 2023 Jul 6. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, F.; Uribarri, A.; Larrañaga-Moreira, J.M.; Ruiz-Guerrero, L.; Pastor-Pueyo, P.; Gayán-Ordás, J.; Fernández-González, B.; Esteban-Fernández, A.; Barreiro, M.; López-Fernández, S.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy. Consensus document of the SEC-Working Group on Myocarditis. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 2024, 77, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, E. , Buono, A., Moroni, F., Gigli, L., Power, J.R., Ciabatti, M., Garascia, A., Adler, E.D., Pieroni, M. State-of-the-Art of Endomyocardial Biopsy on Acute Myocarditis and Chronic Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2022;24(5):597-609. [CrossRef]

- E, Kaur S, Jaber WA. Modern tools in cardiac imaging to assess myocardial inflammation and infection. Eur Heart J Open. 2023;3(2):oead019. [CrossRef]

- Gao Q, Yi W, Gao C, Qi T, Li L, Xie K, Zhao W, Chen W. Cardiac magnetic resonance feature tracking myocardial strain analysis in suspected acute myocarditis: diagnostic value and association with severity of myocardial injury. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):162. [CrossRef]

- Kociol, R.D. , Cooper L.T., Fang J.C., Moslehi J.J., Pang P.S., Sabe M.A., Shah R.V., Sims D.B., Thiene G., Vardeny O., et al. Recognition and Initial Management of Fulminant Myocarditis. Circulation. 2020;141:E69–E92. [CrossRef]

- Lasica, R.; Djukanovic, L.; Savic, L.; Krljanac, G.; Zdravkovic, M.; Ristic, M.; Lasica, A.; Asanin, M.; Ristic, A. Update on Myocarditis: From Etiology and Clinical Picture to Modern Diagnostics and Methods of Treatment. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kindi, S.G. , Xie, R., Kirklin, J.K., Cowger, J., Oliveira, G.H., Krabatsch, T., Nakatani, T., Schueler, S., Leet, A., Golstein, D., et al. Outcomes of Durable Mechanical Circulatory Support in Myocarditis: Analysis of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support Registry. ASAIO J. 2022;68(2):190-196. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Jung, H.O.; Kim, H.; Bae, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Jeo, D.S. 10-year survival outcome after clinically suspected acute myocarditis in adults: A nationwide study in dunishthe pre-COVID-19 era. PLoS ONE 18(1): e0281296. [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, E. , Cipriani, M., Moro, C., Raineri, C., Pini, D., Sormani, P., Mantovani, R., Varrenti, M., Pedrotti, P., Conca, C., et al. Clinical Presentation and Outcome in a Contemporary Cohort of Patients With Acute Myocarditis: Multicenter Lombardy Registry. Circulation. 2018;138(11):1088-1099. [CrossRef]

- Hashmani, S.; Manla, Y.; Al Matrooshi, N.; Bader, F. Red Flags in Acute Myocarditis, Cardiac Failure Review 2024;10:e02. doi.org/10.15420/cfr.2023.

- Nagai, T. , Katsuki, M., Amemiya, K., Takahashi, A., Oyama-Manabe, N., Ohta-Ogo, K., Imanaka-Yoshida, K., Ishibashi-Ueda, H., Anzai, T. Chronic Active Myocarditis and Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy - Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment. Circ J. Published online , 2025. 31 May. [CrossRef]

- Florent Huang, for the FULLMOON Study Group. Fulminant myocarditis proven by early biopsy and outcomes. Eur. Heart J., 2023, 44, 5110–5124. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kindi SG, Outcomes of Durable Mechanical Circulatory Support in Myocarditis: Analysis of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support Registry. ASAIO J. 2022 Feb 1;68(2):190-196. [CrossRef]

- Ghanizada M, Kristensen SL, Bundgaard H, Rossing K, Sigvardt F, Madelaire C, et al. Long-term prognosis following hospitalization for acute myocarditis—a matched nationwide cohort study. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2021; 55(5):264–9. doi.org/10.1080/14017431.2021. 1900.

- Martens CR, Accornero F. Viruses in the Heart: Direct and Indirect Routes to Myocarditis and Heart Failure. Viruses. 2021;13(10):Published 2021 Sep 24. [CrossRef]

- Falleti J, Orabona P, Municinò M, Castellaro G, Fusco G, Mansueto G. An Update on Myocarditis in Forensic Pathology. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Apr 3;14(7):760. [CrossRef]

- van den Hoogen, B. G., J. C. de Jong, J. Groen, T. Kuiken, R. de Groot, R. A. Fouchier, and A. D. Osterhaus. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 719-724.

- Uddin S, Thomas M. Human Metapneumovirus. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.

- Hennawi HA, Khan A, Shpilman A, Mazzoni JA. Acute myocarditis secondary to human metapneumovirus: a case series and mini-review. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2024 Dec 31;2024(6):e202452. [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf A, Peipoch L, Duport P, Darrieux E, Reguerre Y, Ramful D, Alessandri JL, Levy Y. First Case of Acute Myocarditis Caused by Metapneumovirus in an Immunocompromised 14-year-old Girl. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022 Jun;26(6):745-747. [CrossRef]

- Wang SH, Lee MH, Lee YJ, Liu YC. Metapneumovirus-Induced Myocarditis Complicated by Klebsiella pneumoniae Co-Infection: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2024 Dec 27;25:e946119. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Xie, Z.; Xu, L. Receptors and host factors: key players in human metapneumovirus infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1557880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harburger, D. S. , and Calderwood, D. A. Integrin signalling at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, V. , Quiccione, M. S., Tafuri, S., Avallone, L., and Pavone, L. M. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans in viral infection and treatment: A special focus on SARS-coV-Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(12):6574. [CrossRef]

- Ballegeer, M.; Saelens, X. Cell-Mediated Responses to Human Metapneumovirus Infection. Viruses 2020, 12, 542; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X. , Liu, T. , Shan, Y., Li, K., Garofalo, R. P., and Casola, A. Human metapneumovirus glycoprotein G inhibits innate immune responses. PloS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson RL, Fuentes SM, Wang P, Taddeo EC, Klatt A, Henderson AJ, He B. Function of small hydrophobic proteins of paramyxovirus. J Virol. 2006;80(4):1700–9.

- Bao X, Kolli D, Liu T, Shan Y, Garofalo RP, Casola A. Human metapneumovirus small hydrophobic protein inhibits NF-kappaB transcriptional activity. J Virol. 2008 Aug;82(16):8224-9. [CrossRef]

- Lê VB, Dubois J, Couture C, Cavanagh MH, Uyar O, Pizzorno A, et al. Human metapneumovirus activates NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome via its small hydrophobic protein which plays a detrimental role during infection in mice. PLoS Pathog 15(4): e1007689. [CrossRef]

- Ren R, Wu S, Cai J, Yang Y, Ren X, Feng Y, et al. The H7N9 influenza A virus infection results in lethal inflammation in the mammalian host via the NLRP3-caspase-1 inflammasome. Sci Rep. 2017; 7 (1):7625. [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava G, Leo´n-Jua´rez M, Garcı´a-Cordero J, Meza-Sa´nchez DE, Cedillo-Barro´n L. Inflammasomes and its importance in viral infections. Immunol Res. 2016; 64(5):1101–17. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Li, L., Liu, L., Zhang, T., and Sun, M. (2023). Neutralising antibodies against human metapneumovirus. Lancet Microbe 4, e732–e744. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00134-9. [CrossRef]

- Martı́nez-Espinoza, I. , Bungwon, A. D., and Guerrero-Plata, A. Human metapneumovirus-induced host microRNA expression impairs the interferon response in macrophages and epithelial cells. Viruses 2023, 15, v15112272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños-Lara Mdel, R. , Ghosh, A. , and Guerrero-Plata, A. Critical role of MDA5 in the interferon response induced by human metapneumovirus infection in dendritic cells and in vivo. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, T. M. , Zhang, Y. , Kenney, A. D., Zhang, L., Zani, A., Lu, M., et al. IFITM3 restricts human metapneumovirus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1582–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, V. B. , Riteau, B. , Alessi, M. C., Couture, C., Jandrot-Perrus, M., Rhéaume, C., et al. Protease-activated receptor 1 inhibition protects mice against thrombindependent respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus infections. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirogane,Y. Takeda,M., Iwasaki, M., Ishiguro,N.,Takeuchi, H., Nakatsu,Y., et al. Efficient multiplication of human metapneumovirus in Vero cells expressing the transmembrane serine protease. TMPRSSJ. Virol. 2008, 82, 8942–8946. [CrossRef]

- Ogonczyk Makowska D, Hamelin ME, Boivin G. Engineering of live chimeric vaccines against human metapneumovirus. Pathogens. 2020;9(2):135. [CrossRef]

- August A, Shaw CA, Lee H, Knightly C, Kalidindia S, Chu L, Essink BJ, Seger W, Zaks T, Smolenov I, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an mRNA-based human metapneumovirus and parainfluenza virus type 3 combined vaccine in healthy adults. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022, 9(7), ofac206. [CrossRef]

- Ma S, Zhu F, Xu Y, Wen H, Rao M, Zhang P, Peng W, Cui Y, Yang H, Tan C, Chen J, Pan P. Development of a novel multi-epitope mRNA vaccine candidate to combat HMPV virus. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023 Dec 15;19(3):2293300. [CrossRef]

- Pereira JM, Xu S, Leong JM, Sousa S. The Yin and Yang of Pneumolysin During Pneumococcal Infection. Front Immunol. 2022;13:Published 2022 Apr 22. [CrossRef]

- Fillon S, Soulis K, Rajasekaran S, Benedict-Hamilton H, Radin JN, et al. Platelet-activating factor receptor and innate immunity: uptake of Gram-positive bacterial cell wall into host cells and cell-specific pathophysiology. J Immunol 2006, 177: 6182–6191. doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.177.9. 6182.

- Zhang Y, Liang S, Zhang S, Zhang S, Yu Y, Yao H, Liu Y, Zhang W, Liu G. Development and evaluation of a multi-epitope subunit vaccine against group B Streptococcus infection. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11(1):2371–82.

- Chen, R. , Zhang, H., Tang, B. et al. Macrophages in cardiovascular diseases: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Sig Transduct Target Ther 9, 130 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hu M, Deng F, Song X, Zhao H, Yan F. The crosstalk between immune cells and tumor pyroptosis: advancing cancer immunotherapy strategies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024 Jul 10;43(1):190. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Zhou Z, Zheng Y, Yang S, Huang K, Li H. Roles of inflammasomes in viral myocarditis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023 ;13:1149911. 15 May. [CrossRef]

- Turner MD, Nedjai B, Hurst T, Pennington DJ. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 Nov;1843(11):2563-2582. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C. , Xu, S. , Jiang, R. et al. The gasdermin family: emerging therapeutic targets in diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Veerdonk FL, Netea MG, Dinarello CA, Joosten LA. Inflammasome activation and IL-1β and IL-18 processing during infection. Trends Immunol. 2011 Mar;32(3):110-6. [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani AA, Alhamlan FS, Al-Qahtani AA. Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins in Infectious Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2024 Jan 4;9(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Han Xiao, Hao Li, Jing-Jing Wang, Jian-Shu Zhang, Jing Shen, Xiang-Bo An, Cong-Cong Zhang, Ji-Min Wu, Yao Song, Xin-Yu Wanget al. IL-18 cleavage triggers cardiac inflammation and fibrosis upon β-adrenergic insult, European Heart Journal, Volume 39, Issue 1, , Pages 60–69. 01 January. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yin, D. Pathophysiological Effects of Various Interleukins on Primary Cell Types in Common Heart Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K.; Nakanishi, K.; Tsutsui, H. Interleukin-18 in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:229-65. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen I, Miao EA. Pyroptotic cell death defends against intracellular pathogens. Immunol Rev. 2015 May;265(1):130-42. [CrossRef]

- Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013 Jun;13(6):397-411. [CrossRef]

- Ihim SA, Abubakar SD, Zian Z, Sasaki T, Saffarioun M, Maleknia S, Azizi G. Interleukin-18 cytokine in immunity, inflammation, and autoimmunity: Biological role in induction, regulation, and treatment. Front Immunol. 2022 Aug 11;13:919973. [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Okamura H. Interleukin-18 is a unique cytokine that stimulates both Th1 and Th2 responses depending on its cytokine milieu. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001 Mar;12(1):53-72. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Shyam, S. ; Das, S; Nandi, D. Global transcriptome analysis identifies nicotinamide metabolism to play key roles in IFN-γ and nitric oxide modulated responses. bioRxiv 2025.01.17.633516; [CrossRef]

- Camilli G, Blagojevic M, Naglik JR, Richardson JP. Programmed Cell Death: Central Player in Fungal Infections. Trends Cell Biol. 2021 Mar;31(3):179-196. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J. , Sterling, K., Wang, Z. et al. The role of inflammasomes in human diseases and their potential as therapeutic targets. Sig Transduct Target Ther 9, 10 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Li, D. , Wu, M. Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 6, 291 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Olsen MB, Gregersen I, Sandanger Ø, Yang K, Sokolova M, Halvorsen BE, Gullestad L, Broch K, Aukrust P, Louwe MC. Targeting the Inflammasome in Cardiovascular Disease. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021 Nov 3;7(1):84-98. [CrossRef]

- Wen Y, Liu Y, Liu W, Liu W, Dong J, Liu Q, Hao H, Ren H. Research progress on the activation mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome in septic cardiomyopathy. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023 Oct;11(10):e1039. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Zhao W, Lv Y, Li H, Li J, Zhong M, Pu D, Jian F, Song J, Zhang Y. NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis exacerbates coxsackievirus A16 and coxsackievirus A10-induced inflammatory response and viral replication in SH-SY5Y cells. Virus Res. 2024 Jul;345:199386. [CrossRef]

- El Gendy A, Abo Ali FH, Baioumy SA, Taha SI, El-Bassiouny M, Abdel Latif OM. NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (rs10754558) gene polymorphism in chronic spontaneous urticaria: A pilot case-control study. Immunobiology. 2025 Jan;230(1):152868. [CrossRef]

- Remnitz, A.D.; Hadad, R.; Keane, R.W.; Dietrich, W.D.; de Rivero Vaccari, J.P. Comparison of Methods of Detecting IL-1β in the Blood of Alzheimer’s Disease Subjects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badacz, R.; Przewłocki, T.; Legutko, J.; Żmudka, K.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. microRNAs Associated with Carotid Plaque Development and Vulnerability: The Clinician’s Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliaro, P.; Penna, C. Inhibitors of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Ischemic Heart Disease: Focus on Functional and Redox Aspects. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Ma, X.; Yang, X.; Xiao, S.; Ouyang, S.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, Z. E. coli Nissle 1917 improves gut microbiota composition and serum metabolites to counteract atherosclerosis via the homocitrulline/Caspase 1/NLRP3/GSDMD axis. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2025, 318, 151642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Zhao Y, Shao F. Non-canonical activation of inflammatory caspases by cytosolic LPS in innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015 Feb;32:78-83. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Duran, I. , Quintanilla, A., Tarrats, N. et al. Cytoplasmic innate immune sensing by the caspase-4 non-canonical inflammasome promotes cellular senescence. Cell Death Differ 29, 1267–1282 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lupino E, Ramondetti C, Piccinini M. IκB kinase β is required for activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in CD3/CD28-stimulated primary CD4(+) T cells. J Immunol. 2012 Mar 15;188(6):2545-55. [CrossRef]

- Abdrabou, A.M. The Yin and Yang of IκB Kinases in Cancer. Kinases Phosphatases 2024, 2, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez KE, Bhaskar K, Rosenberg GA. Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD-mediated release of matrix metalloproteinase 10 stimulates a change in microglia phenotype. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022 Oct 11;15:976108. [CrossRef]

- Bazzone LE, King M, MacKay CR, Kyawe PP, Meraner P, Lindstrom D, Rojas-Quintero J, Owen CA, Wang JP, Brass AL, Kurt-Jones EA, Finberg RW. A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase 9 Domain (ADAM9) Is a Major Susceptibility Factor in the Early Stages of Encephalomyocarditis Virus Infection. mBio. 2019 Feb 5;10(1):e02734-18. [CrossRef]

- Spector, Lauren1,2; Subramanian, Naeha1,2,*. Revealing the dance of NLRP3: spatiotemporal patterns in inflammasome activation. Immunometabolism 7(1):p e00053, January 2025. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury SM, Ma X, Abdullah SW, Zheng H. Activation and Inhibition of the NLRP3 Inflammasome by RNA Viruses. J Inflamm Res. 2021 Mar 26;14:1145-1163. [CrossRef]

- Beyerstedt S, Casaro EB, Rangel ÉB. COVID-19: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and tissue susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021 May;40(5):905-919. [CrossRef]

- Sagris, M.; Theofilis, P.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Tsioufis, C.; Oikonomou, E.; Antoniades, C.; Crea, F.; Kaski, J.C.; Tousoulis, D. Inflammatory Mechanisms in COVID-19 and Atherosclerosis: Current Pharmaceutical Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun J, Li Y. Pyroptosis and respiratory diseases: A review of current knowledge. Front Immunol. 2022 Sep 30;13:920464. [CrossRef]

- Ingram T, Evbuomwan MO, Jyothidasan A. A case report of sepsis-induced dilated cardiomyopathy secondary to human metapneumovirus infection. Cureus. e: 2024;16(4), 2024.

- Wang SH, Lee MH, Lee YJ, Liu YC. Metapneumovirus-Induced Myocarditis Complicated by Klebsiella pneumoniae Co-Infection: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2024 Dec 27;25:e946119.

- Hennawi HA, Khan A, Shpilman A, Mazzoni JA. Acute myocarditis secondary to human metapneumovirus: a case series and mini-review. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2024 Dec 31;2024 (6):e202452. [CrossRef]

- Cox RG, Mainou BA, Johnson M, et al. Human metapneumovirus is capable of entering cells by fusion with endosomal membranes. PLoS Pathog. e: 2015;11(12), 2015.

- Soto JA, Galvez NMS, Benavente FM, et al. Human metapneumovirus: Mechanisms and molecular targets used by the virus to avoid the immune system. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2466.

- Van Den Bergh A, Bailly B, Guillon P, et al. Antiviral strategies against human metapneumovirus: Targeting the fusion protein. Antiviral Res. 1: 2022;207, 2022.

- Tsigkou, V.; Oikonomou, E.; Anastasiou, A.; Lampsas, S.; Zakynthinos, G.E.; Kalogeras, K.; Katsioupa, M.; Kapsali, M.; Kourampi, I.; Pesiridis, T.; Marinos, G.; Vavuranakis, M.-A.; Tousoulis, D.; Vavuranakis, M.; Siasos, G. Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications of Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients with Heart Failure. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. , Tian, Y. , Wang, H. et al. Dual Regulation of Nicotine on NLRP3 Inflammasome in Macrophages with the Involvement of Lysosomal Destabilization, ROS and α7nAChR. Inflammation 2025, 48, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Moura, A.K.; Hu, J.Z.; Wang, Y.-T.; Zhang, Y. Lysosome Functions in Atherosclerosis: A Potential Therapeutic Target. Cells 2025, 14, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanaban, A.M.; Ganesan, K.; Ramkumar, K.M. A Co-Culture System for Studying Cellular Interactions in Vascular Disease. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casella M, Gasperetti A, Compagnucci P, Narducci ML, Pelargonio G, Catto V, Carbucicchio C, Bencardino G, Conte E, Schicchi N, Andreini D, Pontone G, Giovagnoni A, Rizzo S, Inzani F, Basso C, Natale A, Tondo C, Russo AD, Crea F. Different Phases of Disease in Lymphocytic Myocarditis: Clinical and Electrophysiological Characteristics. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2023 Mar;9(3):314-326. [CrossRef]

- Heymans S, et al. Inflammation as a therapeutic target in heart failure? Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115(7):1189-1201. [CrossRef]

- Ying, C. Viral Myocarditis. Yale J Biol Med. 2024 Dec 19;97(4):515-520. [CrossRef]

- Vicenzetto C, Giordani AS, Menghi C, Baritussio A, Scognamiglio F, Pontara E, Bison E, Peloso-Cattini MG, Marcolongo R, Caforio ALP. Cellular Immunology of Myocarditis: Lights and Shades-A Literature Review. Cells. 2024, 13(24), 2082. [CrossRef]

- Badrinath A, Bhatta S, Kloc A. Persistent viral infections and their role in heart disease. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1030440].

- Tavazzi G, Pellegrini C, Maurelli M, Belliato M, Sciutti F, Bottazzi A, et al. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020 May;22(5):911–5.

- Kühl U, Pauschinger M, Schwimmbeck PL, Seeberg B, Lober C, Noutsias M, et al. Interferon-β treatment eliminates cardiotropic viruses and improves left ventricular function in patients with myocardial persistence of viral genomes and left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2: 2003 Jun;107(22), 2003.

- Schultheiss HP, Piper C, Sowade O, Waagstein F, Kapp JF, Wegscheider K, et al. Betaferon in chronic viral cardiomyopathy (BICC) trial: effects of interferon-β treatment in patients with chronic viral cardiomyopathy. Clin Res Cardiol. 2016 Sep;105(9):763–73.

- Hang, W. , Chen, C., Seubert, J.M. et al. Fulminant myocarditis: a comprehensive review from etiology to treatments and outcomes. Sig Transduct Target Ther 5, 287 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Hafezi-Moghadam, A.; et al. Acute cardiovascular protective effects of corticosteroids are mediated by non-transcriptional activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat. Med. 8, 473–479 (2002).

- Mason, J. W.; et al. A clinical trial of immunosuppressive therapy for myocarditis. The Myocarditis Treatment Trial Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chimenti C, Russo MA, Frustaci A. Immunosuppressive therapy in virus-negative inflammatory cardiomyopathy: 20-year follow-up of the TIMIC trial. Eur Heart J 2022; 43: 3463 – 3473.

- Wojnicz R, Nowalany-Kozielska E, Wojciechowska C, Glanowska G, Wilczewski P, Niklewski T, et al. Randomized, placebocontrolled study for immunosuppressive treatment of inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy: Two-year follow-up results. Circulation 2001; 104: 39 – 45. 55.

- Frustaci A, Chimenti C, Calabrese F, Pieroni M, Thiene G, Maseri A. Immunosuppressive therapy for active lymphocytic myocarditis: Virological and immunologic profile of responders versus nonresponders. Circulation 2003; 107: 857 – 863. 56.

- Frustaci A, Russo MA, Chimenti C. Randomized study on the efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy in patients with virusnegative inflammatory cardiomyopathy: The TIMIC study. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 1995 – 2002. 57.

- Merken J, Hazebroek M, Van Paassen P, Verdonschot J, Van Empel V, Knackstedt C, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy improves both short- and long-term prognosis in patients with virus-negative nonfulminant inflammatory cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail 2018; 11: e004228.

- Caforio ALP, Giordani AS, Baritussio A, Marcolongo D, Vicenzetto C, Tarantini G, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of tailored immunosuppressive therapy in immune-mediated biopsy-proven myocarditis: A propensity-weighted study. Eur J Heart Fail 2024; 26: 1175 – 1185.

- Hahn EA, Hartz VL, Moon TE, O'Connell JB, Herskowitz A, McManus BM, Mason JW. The Myocarditis Treatment Trial: design, methods and patients enrollment. Eur Heart J. 1995 Dec;16 Suppl O:162-7. [CrossRef]

- Gupta SC, Sundaram C, Reuter S, Aggarwal BB. Inhibiting NF-κB activation by small molecules as a therapeutic strategy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 Oct-Dec;1799(10-12):775-87. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. , Lin, L., Zhang, Z. et al. Targeting NF-κB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas RHCN, Fraga CAM. NF-κB-IKKβ Pathway as a Target for Drug Development: Realities, Challenges and Perspectives. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(16):1933-1942. [CrossRef]

- Georgiopoulos G, Makris N, Laina A, Theodorakakou F, Briasoulis A, Trougakos IP, Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Stamatelopoulos K. Cardiovascular Toxicity of Proteasome Inhibitors: Underlying Mechanisms and Management Strategies: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol. 2023 Feb 21;5(1):1-21. [PubMed]

- Chin, CG. , Chen, YC. , Lin, FJ. et al. Targeting NLRP3 signaling reduces myocarditis-induced arrhythmogenesis and cardiac remodeling. J Biomed Sci 2024, 31, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino M, Coe A, Aljabi A, Talasaz AH, Van Tassell B, Abbate A, Markley R. Effect of colchicine on 90-day outcomes in patients with acute myocarditis: a real-world analysis. Am Heart J Plus. 2024 Oct 24;47:100478. [CrossRef]

- Collini, V. , De Martino M. Efficacy and safety of colchicine for the treatment of myopericarditis. Heart. Jan 18 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kavgacı A, Incedere F, Terlemez S, Kula S. Successful treatment of two cases of acute myocarditis with colchicine. Cardiology in the Young. 2023;33(9):1741-1742. [CrossRef]

- Pappritz, K. , Lin J., El-Shafeey M., et al. Colchicine prevents disease progression in viral myocarditis via modulating the NLRP3 inflammasome in the cardiosplenic axis. ESC Heart Fail. Apr 2022;9(2):925–941. [CrossRef]

- Deftereos SG, Giannopoulos G, Vrachatis DA, et al. Effect of Colchicine vs Standard Care on Cardiac and Inflammatory Biomarkers and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized With Coronavirus Disease 2019: The GRECCO-19 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e2013136. [CrossRef]

- Wohlford, George F et al. “Phase 1B, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Dose Escalation, Single-Center, Repeat Dose Safety and Pharmacodynamics Study of the Oral NLRP3 Inhibitor Dapansutrile in Subjects With NYHA II-III Systolic Heart Failure.” Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology vol. 77,1 49-60. 24 Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shuangcui et al. “NLRP3 inflammasome as a novel therapeutic target for heart failure.” Anatolian journal of cardiology vol. 26,1 (2022): 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Ridker, Paul M et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. NEJM 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [CrossRef]

- Silvis MJM, Demkes EJ, Fiolet ATL, Dekker M, Bosch L, van Hout GPJ, Timmers L, de Kleijn DPV. Immunomodulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Atherosclerosis, Coronary Artery Disease, and Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2021 Feb;14(1):23-34. [CrossRef]

- Morton AC, Rothman AM, Greenwood JP, Gunn J, Chase A, Clarke B, Hall AS, Fox K, Foley C, Banya W, Wang D, Flather MD, Crossman DC. The effect of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist therapy on markers of inflammation in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: the MRC-ILA Heart Study. Eur Heart J. 2015 Feb 7;36(6):377-84. [CrossRef]

- Abbate A, Trankle CR, Buckley LF, Lipinski MJ, Appleton D, Kadariya D, Canada JM, Carbone S, Roberts CS, Abouzaki N, et al. Interleukin-1 Blockade Inhibits the Acute Inflammatory Response in Patients With ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Mar 3;9(5):e014941. [CrossRef]

- Cavalli G, Foppoli M, Cabrini L, Dinarello CA, Tresoldi M, Dagna L. Interleukin-1 Receptor Blockade Rescues Myocarditis-Associated End-Stage Heart Failure. Front Immunol. 2017 Feb 9;8:131.

- Ma, P.; et al. IL-1 Signaling Blockade in Human Lymphocytic Myocarditis. Circ Res 2025, doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.125. 3265. [Google Scholar]

- Kerneis, M.; Cohen, F.; Combes, A.; Amoura, Z.; Pare, C.; Brugier, D.; Puymirat, E.; Abtan, J.; Lattuca, B.; Dillinger, J.-G.; et al. ACTION Study Group, Rationale and design of the ARAMIS trial: Anakinra versus placebo, a double blind randomized controlled trial for the treatment of acute myocarditis, Volume 1267, Issue 1, 7/2023, Pages 1-73, ISSN 1875-2136. [CrossRef]

- Lema, D.A.; et al. IL1RAP Blockade With a Monoclonal Antibody Reduces Cardiac Inflammation and Preserves Heart Function in Viral and Autoimmune Myocarditis. Circ Heart Fail. e: 2024;17, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li S, Jiang L, Beckmann K, Højen JF, Pessara U, Powers NE, de Graaf DM, Azam T, Lindenberger J, Eisenmesser EZ, Fischer S, Dinarello CA. A novel anti-human IL-1R7 antibody reduces IL-18-mediated inflammatory signaling. J Biol Chem. 2021 Jan-Jun;296:100630. [CrossRef]

- Jiang L, Lunding LP, Webber WS, Beckmann K, Azam T, Højen JF, Amo-Aparicio J, Dinarello A, Nguyen TT, Pessara U, et al. An antibody to IL-1 receptor 7 protects mice from LPS-induced tissue and systemic inflammation. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1427100. [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y. , Nariai, Y. , Obayashi, E., Tajima, Y., Koga, T., Kawakami, A., Urano, T., Kamino, H. Generation of antagonistic monoclonal antibodies against the neoepitope of active mouse interleukin (IL)-18 cleaved by inflammatory caspases. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics, 2022, 727, 109322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee P, Khan Z. Sacubitril/Valsartan in the Treatment of Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction Focusing on the Impact on the Quality of Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Cureus. 2023, 15(11), e48674. [CrossRef]

- McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Dual angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition as an alternative to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: rationale for and design of the Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM-HF). Eur J Heart Fail 2013, 15, 1062–1073.

- Song Y, Zhao Z, Zhang J, Zhao F, Jin P. Effects of sacubitril/valsartan on life quality in chronic heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Aug 3;9:922721. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui H, Momomura SI, Saito Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan in Japanese patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction- results from the PARALLEL-HF study. Circ J. 2021, 85, 584–594.

- McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014, 371, 993–1004.

- Piepoli MF, Hussain RI, Comin-Colet J, Dosantos R, Ferber P, Jaarsma T, Edelmann F: OUTSTEP-HF: randomised controlled trial comparing short-term effects of sacubitril/valsartan versus enalapril on daily physical activity in patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 127–135.

- Velazquez, E. J. , Morrow, D. A., DeVore, A. D., Duffy, C. I., Ambrosy, A. P., McCague, K., Rocha, R., Braunwald, E., PIONEER-HF Investigators. Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(6):539-548. [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.L.; et al. Sacubitril/Valsartan in Advanced Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction Rationale and Design of the LIFE Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2020, 8(10), 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann DL, Givertz MM, Vader JM, et al.Effect of treatment with sacubitril/valsartan in patients with advanced heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 17–25.

- Manzi L, Buongiorno F, Narciso V, Florimonte D, Forzano I, Castiello DS, Sperandeo L, Paolillo R, Verde N, Spinelli A, et al. Acute Heart Failure and Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathies: A Comprehensive Review and Critical Appraisal. Diagnostics (Basel). 2025 Feb 23;15(5):540. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi RK, Polhemus DJ, Li Z, Yoo D, Koiwaya H, Scarborough A, et al. Combined angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors improve cardiac and vascular function via increased NO bioavailability in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018, 7:8268. [CrossRef]

- Shi YJ, Yang CG, Qiao WB, Liu YC, Dong GJ. Sacubitril/valsartan attenuates myocardial inflammation, hypertrophy, and fibrosis in rats with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;961:176170. [CrossRef]

- Volpe, M. , Rubattu, S. , & Battistoni, A. ARNi: A Novel Approach to Counteract Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2092; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caobelli F, Cabrero JB, Galea N, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with acute myocarditis and chronic inflammatory cardiomyopathy : A review paper with practical recommendations on behalf of the European Society of Cardiovascular Radiology (ESCR). Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;39(11):2221-2235. [CrossRef]

- She J, Lou B, Liu H, Zhou B, Jiang GT, Luo Y, Wu H, Wang C, Yuan Z. ARNI versus ACEI/ARB in Reducing Cardiovascular Outcomes after Myocardial Infarction. ESC Heart Fail. 2021 Dec;8(6):4607-4616. [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Lewis EF, Granger CB, Køber L, Maggioni AP, Mann DL, McMurray JJV, Rouleau JL, Solomon SD, et al.; PARADISE-MI Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition in Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2021 Nov 11;385(20):1845-1855. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Zhang, J.; Honbo, N.; Karliner, J.S. Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiology 2010, 115(2), 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn VS, Sharma K. Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition for Doxorubicin-Mediated Cardiotoxicity: Time for a Paradigm Shift. JACC CardioOncol. 2020, 2(5), 788-790. [CrossRef]

- Wei S, Ma W, Li X, et al. Involvement of ROS/NLRP3 Inflammasome Signaling Pathway in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2020;20(5):507-519. [CrossRef]

- Polegato BF, Minicucci MF, Azevedo PS, et al. Acute doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity is associated with matrix metalloproteinase-2 alterations in rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35(5):1924-1933. [CrossRef]

- Boutagy, N.E. , Feher A., Pfau D. Dual angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition with sacubitril/valsartan attenuates systolic dysfunction in experimental doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. J Am Coll Cardiol CardioOnc. 2020;2:774–787. [CrossRef]

- Bell E, Desuki A, Karbach S, Göbel S. Successful treatment of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy with low-dose sacubitril/valsartan: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2022 Sep 23;6(10):ytac396. [PubMed]

- Hu, F. , Yan, S., Lin, L. et al. Sacubitril/valsartan attenuated myocardial inflammation, fibrosis, apoptosis and promoted autophagy in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity mice via regulating the AMPKα–mTORC1 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biochem 480, 1891–1908 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Dindas, F.; Turkey, U.; Gungor, H.; Ekici, M.; Akokay, P.; Erhan, F.; Dogdus, M.; Yilmaz, M.B. Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibition by sacubitril/valsartan attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in a pretreatment mice model by interfering with oxidative stress, inflammation, and Caspase 3 apoptotic pathway. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2021, 25, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Jang, G.; Hwang, J.; Wei, X.; Kim, H.; Son, J.; Rhee, S.-J.; Yun, K.-H.; Oh, S.-K.; Oh, C.-M.; et al. Combined Therapy of Low-Dose Angiotensin Receptor–Neprilysin Inhibitor and Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitor Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction in Rodent Model with Minimal Adverse Effects. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliariello V, Di Mauro A, Ferrara G, Bruzzese F, Palma G, Luciano A, Canale ML, Bisceglia I, Iovine M, Cadeddu Dessalvi C, et al. Cardio-Renal and Systemic Effects of SGLT2i Dapagliflozin on Short-Term Anthracycline and HER-2-Blocking Agent Therapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Antioxidants (Basel). 2025, 20, 14(5), 612. [CrossRef]

- Lo SH, Liu YC, Dai ZK, Chen IC, Wu YH, Hsu JH. Case Report: Low Dose of Valsartan/Sacubitril Leads to Successful Reversal of Acute Heart Failure in Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Front Pediatr. 2021 Feb 25;9:639551. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez AV, Pasupuleti V, Scarpelli N, Malespini J, Banach M, Bielecka-Dabrowa AM. Efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan in heart failure compared to renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arch Med Sci. 2023;3:565-76. [CrossRef]

- Cemin R, Casablanca S, Foco L, Schoepf E, Erlicher A, Di Gaetano R, Ermacora D. Reverse Remodeling and Functional Improvement of Left Ventricle in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure Treated with Sacubitril/Valsartan: Comparison between Non-Ischemic and Ischemic Etiology. J Clin Med. 2023;12:621. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Zou Y, Li Y, Wang H, Sun W, Liu B. The history and mystery of sacubitril/ valsartan: From clinical trial to the real world. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1102521. [CrossRef]

- Nesukay, E.G.; Kovalenko, V.M.; Cherniuk, S.V.; Kyrychenko, R.M.; Titov, I.Y.; Hiresh, I.I.; Dmytrychenko, O.V.; Slyvna, A.B. Choice of RAAS Blocker in the treatment of Heart Failure in Acute Myocarditis”. Ukrainian Journal of Cardiology, 2024, 31, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang W, Xie BK, Ding PW, Wang M, Yuan J, Cheng X, Liao YH, Yu M. Sacubitril/Valsartan Alleviates Experimental Autoimmune Myocarditis by Inhibiting Th17 Cell Differentiation Independently of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 727838. [CrossRef]

- Bellis, A.; Mauro, C.; Barbato, E.; Trimarco, B.; Morisco, C. The Rationale for Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin Inhibitors in a Multi-Targeted Therapeutic Approach to COVID-Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zile MR, O’Meara E, Claggett B, Prescott MF, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, et al. Effects of sacubitril/valsartan on biomarkers of extracellular matrix regulation in patients with HFrEF. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019, 73, 795–806. [CrossRef]

- Rao W, Li D, Zhang Q, Liu T, Gu Z, Huang L, Dai J, Wang J, Hou X. Complex regulation of cardiac fibrosis: insights from immune cells and signaling pathways. J Transl Med. 2025 Feb 28;23(1):242. [CrossRef]

- Thomas TP, Grisanti LA. The Dynamic Interplay Between Cardiac Inflammation and Fibrosis. Front Physiol. 2020 Sep 15;11:529075. [CrossRef]

- Dziewięcka, E.; Banyś, R.; Wiśniowska-Śmiałek, S.; Winiarczyk, M.; Urbańczyk-Zawadzka, M.; Krupiński, M.; Mielnik, M.; Lisiecka, M.; Gąsiorek, J.; Kyslyi, V.; et al. Prevalence and prognostic implications of the longitudinal changes of right ventricular systolic function on cardiac magnetic resonance in dilated cardiomyopathy. Kardiol Pol. 2025, 83(1), 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Bodegård, J.; Mullin, K.; Gustafsson, S.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Sundström, J. Suspected de novo heart failure in outpatient care: the REVOLUTION HF study. Eur Heart J. 2025, 46(16), 1493–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podolec, J.; Baran, J.; Siedlinski, M.; Urbanczyk, M.; Krupinski, M.; Bartus, K.; Niewiara, L.; Podolec, M.; Guzik, T.; Tomkiewicz-Pajak, L.; et al. Serum rantes, transforming growth factor-1 and interleukin-6 levels correlate with cardiac muscle fibrosis in patients with aortic valve stenosis. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 69, 615–623. [Google Scholar]

- Kablak-Ziembicka, A.; Badacz, R.; Okarski, M.; Wawak, M.; Przewłocki, T.; Podolec, J. Cardiac microRNAs: diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Arch Med Sci 2023; 19 (5): 1360–1381.

- Heidenreich, P.A., Bozkurt, B., Aguilar, D., Allen, L.A., Byun, J.J., Colvin, M.M., Deswal, A., Drazner, M.H., Dunlay, S.M., Evers, L.R., et al, ACC/AHA Joint Committee Members. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 2022, 145(18), e895–e1032.

- Huang S, Chen B, Su Y, Alex L, Humeres C, Shinde AV, Conway SJ, Frangogiannis NG. Distinct roles of myofibroblast-specific Smad2 and Smad3 signaling in repair and remodeling of the infarcted heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 2019, 132, 84–97.

- Nevers T, Salvador AM, Velazquez F, Ngwenyama N, Carrillo-Salinas FJ, Aronovitz M, Blanton RM, Alcaide P, Th1 effector T cells selectively orchestrate cardiac fibrosis in nonischemic heart failure. J Exp Med, 2017, 214, 3311–3329. [CrossRef]

- Duangrat, Ratchanee et al. Dual Blockade of TGF-β Receptor and Endothelin Receptor Synergistically Inhibits Angiotensin II-Induced Myofibroblast Differentiation: Role of AT1R/Gαq-Mediated TGF-β1 and ET-1 Signaling. Int J Mol Scie 2023, 24, 8 6972. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. , Kwan, J. Y.Y., Yip, K. et al. Targeting metabolic dysregulation for fibrosis therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020, 19, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita-Sánchez M, Castillo-Domínguez JC, Mesa-Rubio D, Ruiz-Ortiz M, López-Granados A, Suárez de Lezo J. Se deben mantener los inhibidores de la enzima de conversión de la angiotensina a largo plazo en pacientes que normalizan la fracción de eyección tras un episodio de miocarditis aguda? [Should Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors be continued over the long term in patients whose left ventricular ejection fraction normalizes after an episode of acute myocarditis?]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2006, 59(11), 1199-1201.

- Kayyale, A.A.; Timms, P.; Xiao, H.B. ACE inhibitors reduce the risk of myocardial fibrosis post-cardiac injury: a systematic review. Br J Cardiol 2025;32:72–6. [CrossRef]

- Seko, Y. Effect of the angiotensin II receptor blocker olmesartan on the development of murine acute myocarditis caused by coxsackievirus BClin Sci (Lond). 2006, 110, 379-86. [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. M. , Lighthouse, J. K., Mickelsen, D. M., Small, E. M. Sacubitril/Valsartan Decreases Cardiac Fibrosis in Left Ventricle Pressure Overload by Restoring PKG Signaling in Cardiac Fibroblasts. Circulation. Heart failure, 2019, 12(4), e005565. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Long Q, Yang H, Yang H, Tang Y, Liu B, Zhou Z, Yuan J. Sacubitril/Valsartan inhibits M1 type macrophages polarization in acute myocarditis by targeting C-type natriuretic peptide. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024 May;174:116535. [CrossRef]

- Ding N, Wei B, Fu X, Wang C, Wu Y. Natural Products that Target the NLRP3 Inflammasome to Treat Fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2020 Dec 17;11:591393. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Shen Q. Tranilast reduces cardiomyocyte injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion via Nrf2/HO-1/NF-κB signaling. Exp Ther Med. 2023 Feb 22;25(4):160. [CrossRef]

- Huang LF, Wen C, Xie G, Chen CY. [Effect of tranilast on myocardial fibrosis in mice with viral myocarditis]. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2014 Nov;16(11):1154-61.

- AbdelMassih A, Agha H, El-Saiedi S, El-Sisi A, El Shershaby M, Gaber H, Ismail HA, El-Husseiny N, Amin AR, ElBoraie A, et al. The role of miRNAs in viral myocarditis, and its possible implication in induction of mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines-induced myocarditis. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2022;46(1):267. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.A., Dodd, S., Clayton, D. et al. Pirfenidone in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med 2021, 27, 1477–1482 (). [CrossRef]

- Młynarska, E.; Badura, K.; Kurcinski, S.; Sinkowska, J.; Jakubowska, P.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. The Role of MicroRNA in the Pathophysiology and Diagnosis of Viral Myocarditis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabłak-Ziembicka A, Badacz R, Przewłocki T. Clinical Application of Serum microRNAs in Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease. J Clin Med. 2022 Nov 20;11(22):6849. [CrossRef]

- Grodzka, O.; Procyk, G.; Gąsecka, A. The Role of MicroRNAs in Myocarditis—What Can We Learn from Clinical Trials? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D. Next-generation miRNA therapeutics: from computational design to translational engineering. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bruscella, P.; Bottini, S.; Baudesson, C.; Pawlotsky, J.M.; Feray, C.; Trabucchi, M. Viruses and MiRNAs: More Friends than Foes. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasławska, M.; Grodzka, A.; Peczyńska, J.; Sawicka, B.; Bossowski, A.T. Role of miRNA in Cardiovascular Diseases in Children—Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang J and Han, B. Dysregulated CD4+ T Cells and microRNAs in Myocarditis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.; Tirosh-Wagner, T.; Vardi, A.; Abbas, H.; Pillar, N.; Shomron, N.; Nevo-Caspi, Y.; Paret, G. Circulating MicroRNAs: A Potential Biomarker for Cardiac Damage, Inflammatory Response, and Left Ventricular Function Recovery in Pediatric Viral Myocarditis. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2018, 11, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou DM, Aziz EE, Kazem YS. Elgabrty S, Taha HS. The diagnostic value of circulating microRNA-499 versus high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T in early diagnosis of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Comp Clin Pathol 2021; 30: 565-70.

- Gacoń, J.; Badacz, R.; Stępień, E.; Karch, I.; Enguita, F.J.; Żmudka, K.; Przewłocki, T.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. Diagnostic and prognostic micro-RNAs in ischaemic stroke due to carotid artery stenosis and in acute coronary syndrome: A four-year prospective study. Kardiol. Pol. 2018, 76, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Xu L, Tian L, Sun Q. Circulating microRNA-208 family as early diagnostic biomarkers for acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Medicine 2021; 100: e27779.

- Badacz, R.; Przewlocki, T.; Gacoń, J.; Stępień, E.; Enguita, F.J.; Karch, I.; Żmudka, K.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. Circulating miRNA levels differ with respect to carotid plaque characteristics and symptom occurrence in patients with carotid artery stenosis and provide information on future cardiovascular events. Adv. Interv. Cardiol. 2018, 14, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Tao, L.; Li, X. MicroRNA-21-3p/Rcan1 Signaling Axis Affects Apoptosis of Cardiomyocytes of Sepsis Rats. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2023, 42, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, G.; Wang, L. MiR-21 Participates in LPS-Induced Myocardial Injury by Targeting Bcl-2 and CDKInflamm. Res. 2022, 71, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z. MicroRNA-21 Prevents Excessive Inflammation and Cardiac Dysfunction after Myocardial Infarction through Targeting KBTBDCell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 769.

- Wang J, Han B. Front. Immunol., 2020 Sec. T Cell Biology Volume 2020, 1. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kang Z, Zhang L, Yang Z. Role of non-coding RNAs in the pathogenesis of viral myocarditis. Virulence. 2025 Dec;16(1):2466480.

- Procyk, G.; Grodzka, O.; Procyk, M.; Gąsecka, A.; Głuszek, K.; Wrzosek, M. MicroRNAs in Myocarditis—Review of the preclinical In Vivo Trials. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao JL, Lin L. MiR-155 and miR-148a reduce cardiac injury by inhibiting NF-κB pathway during acute viral myocarditis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014 Aug;18(16):2349-56.

- Corsten, M.F.; Papageorgiou, A.; Verhesen, W.; Carai, P.; Lindow, M.; Obad, S. ; Summer, G; et al. MicroRNA Profiling Identifies MicroRNA-155 as an Adverse Mediator of Cardiac Injury and Dysfunction During Acute Viral Myocarditis. Circulation Research 2012, 111. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Zhang, M. , Li, X. et al. Silencing MicroRNA-155 Attenuates Cardiac Injury and Dysfunction in Viral Myocarditis via Promotion of M2 Phenotype Polarization of Macrophages. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 22613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L. ;Wu,W. F.; Xue, Y.; Gao, M.; Yan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Pang, Y.; Yang, F. MicroRNA-21 and -146b Are Involved in the Pathogenesis of Murine Viral Myocarditis by Regulating TH-17 Differentiation. Arch. Virol. 2013, 158, 1953–1963. [Google Scholar]

- Xu HF, Ding YJ, Zhang ZX, et al. MicroRNA-21 regulation of the progression of viral myocarditis to dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10(1):161–168. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Domínguez R, Sánchez-Díaz R, de la Fuente H, et al. A novel circulating MicroRNA for the detection of acute myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384 (21):2014–2027. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Tu J, Gao H, et al. MicroRNA-425-3p inhibits myocardial inflammation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in mice with viral myocarditis through targeting tgf-βImmun Inflamm Dis. 2021;9(1):288–298. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Liu M, Zhao C, Chen C, Kong Q, Cai Z, Li D. MiR-1/133 attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis and electrical remodeling in mice with viral myocarditis. Cardiol J. 2020;27(3):285-294. [CrossRef]

- Baños-Lara, M.D.R.; Zabaleta, J.; Garai, J.; Baddoo, M.; Guerrero-Plata, A. Comparative analysis of miRNA profile in human dendritic cells infected with respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus. BMC Res Notes 2018, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasławska, M.; Grodzka, A.; Peczyńska, J.; Sawicka, B.; Bossowski, A.T. Role of miRNA in Cardiovascular Diseases in Children—Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J. , Ptashkin, R. N., Wang, Q., Liu, G., Zhang, G., Lee, I., et al. Human metapneumovirus infection induces significant changes in small noncoding RNA expression in airway epithelial cells. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2014, 3, e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Choi, E.-J.; Lee, I.; Lee, Y.S.; Bao, X. Non-Coding RNAs and Their Role in Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) and Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) Infections. Viruses 2020, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Espinoza I, Bungwon AD, Guerrero-Plata A. Human Metapneumovirus-Induced Host microRNA Expression Impairs the Interferon Response in Macrophages and Epithelial Cells. Viruses. 2023, 15(11):2272. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Garg, I.; Singh, Y.; Meena, R.; Ghosh, N.; Kumari, B.; Kumar, V.; Eslavath, M.R.; Singh, S.; Dogra, V.; et al. Evaluation of Altered MiRNA Expression Pattern to Predict COVID-19 Severity. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvado, V.d.A.; Alves, A.D.R.; Coelho, W.L.d.C.N.P.; Costa, M.A.; Guterres, A.; Amado, L.A. Screening out microRNAs and Their Molecular Pathways with a Potential Role in the Regulation of Parvovirus B19 Infection Through In Silico Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilam-Frenkel, B.; Naaman, H.; Brkic, G.; Veksler-Lublinsky, I.; Rall, G.; Shemer-Avni, Y.; Gopas, J. MicroRNA 146–5p, miR-let-7c-5p, miR-221 and miR-345–5p are differentially expressed in Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) persistently infected HEp-2 cells. Virus Res. 2018, 251, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Sun, X. Respiratory syncytial virus non-structural protein 1 facilitates virus replication through miR-29a-mediated inhibition of interferon-alpha receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 478, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.H.; He, J.; Zhou, R.; Zheng, N. Expression and Significance of Circulating microRNA-29b in Adult Fulminant Myocarditis. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao 2022, 44, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, K.; Imanaka-Yoshida, K. The Pathogenesis of Cardiac Fibrosis: A Review of Recent Progress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foinquinos, A. , Batkai, S. , Genschel, C. et al. Preclinical development of a miR-132 inhibitor for heart failure treatment. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täubel J, Hauke W, Rump S, Viereck J, Batkai S, Poetzsch J, Rode L, Weigt H, Genschel C, Lorch U, Theek C, Levin AA, Bauersachs J, Solomon SD, Thum T. Novel antisense therapy targeting microRNA-132 in patients with heart failure: results of a first-in-human Phase 1b randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Heart J. 2021 Jan 7;42(2):178-188. [CrossRef]

- Bauersachs J, Solomon SD, Anker SD, Antorrena-Miranda I, Batkai S, Viereck J, Rump S, Filippatos G, Granzer U, Ponikowski P, de Boer RA, Vardeny O, Hauke W, Thum T. Efficacy and safety of CDR132L in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction after myocardial infarction: Rationale and design of the HF-REVERT trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024 Mar;26(3):674-682. [CrossRef]

- Kawai, C. From Myocarditis to Cardiomyopathy: Mechanisms of Inflammation and Cell Death Learning From the Past for the Future. Circulation. 1999;99:1091-1100.

- Martens, P.; Cooper, L.T.; Tang, W.H.W. Diagnostic Approach for Suspected Acute Myocarditis: Considerations for Standardization and Broadening Clinical Spectrum. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinge SAU, Zhang B, Zheng B, Qiang Y, Ali HM, Melchiade YTV, Zhang L, Gao M, Feng G, Zeng K, Yang Y. Unveiling the Future of Infective Endocarditis Diagnosis: The Transformative Role of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing in Culture-Negative Cases. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2025 Aug 22;15(1):108. [CrossRef]

- Podolec, J.; Przewłocki, T.; Kabłak-Ziembicka, A. Optimization of Cardiovascular Care: Beyond the Guidelines. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Menger J, Collini V, Gröschel J, Adler Y, Brucato A, Christian V, Ferreira VM, Gandjbakhch E, Heidecker B, Kerneis M, Klein AL, Klingel K, Lazaros G, Lorusso R, Nesukay EG, Rahimi K, Ristić AD, Rucinski M, Sade LE, Schaubroeck H, Semb AG, Sinagra G, Thune JJ, Imazio M; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2025 ESC Guidelines for the management of myocarditis and pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2025 Aug 29:ehaf192. [CrossRef]

| Study | Medication / comparator | Type of the study | Study design | Main findings | Outcomes | Remarks / limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors of the NLRP3 pathway | ||||||

| Chin, CG et al., 2024 [142] | MCC950 vs placebo | Experimental, animal model | Rats with myosin peptide–induced myocarditis (experimental group) were treated with an NLRP3 inhibitor (MCC950; 10 mg/kg, daily for 14 days) or left untreated | Rats treated with MCC950 improved their LV-EF and reduced the frequency of premature ventricular contraction | Changes in heart structure may be mitigated by inhibiting NLRP3 signaling. | A study on animal model |

| Golino M et al. 2024 [143] | Colchicine vs placebo in 1:1 proportion | Retrospective multi-center study in the US of patients hospitalized with acute myocarditis |

In total 1137 patients with acute myocarditis treated with colchicine within 14 days of diagnosis vs whose not obtaining colchicine | The incidence of the all-cause death was 3.3% vs. 6.6% (HR, 0.48, 95% CI, 0.33–0.71; p < 0.001), ventricular arrhythmias: 6.1% vs. 9.1% (HR, 0.65, 95% CI, 0.48–0.88; p < 0.01), and acute HF: 10.9% vs. 14.7% (HR 0.72, 95% CI, 0.57–0.91; p < 0.01) in patients treated with colchicine or not, respectively. | Patients with acute myocarditis treated with colchicine within 14 days of diagnosis have better outcomes at 90 days | Short-term outcomes |

| Collini et al., 2024 [144] | 45.1% of patients were treated with colchicine | Retrospective cohort study | A total of 175 patients with pericarditis and myocarditis, 88.6% with idiopathic/viral aetiology of myocarditis | In multivariable Cox regression analysis, women (HR 1.97, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.73; p=0.037) and corticosteroid use (HR 2.27, 95% CI 1.15 to 4.47; p=0.018) were risk factors of recurrence, and colchicine use prevented recurrences (HR 0.39, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.76; p=0.005). | After a median follow-up of 25.3 (IQR 8.3–45.6) months, colchicine use was associated with a lower incidence of recurrences (respectively, 19.2% vs 43.8%; p=0.001) and a longer event-free survival (p=0.005) |

Concomitant pericarditis and myocarditis |

| Pappritz et al 2022 [146] | Colchicine (5 µmol/kg p.o. daily) vs vehicle (PBS) | Preclinical, experimental | Murine model of CVB3-induced myocarditis; treatment started 24 h post-infection for 7 days | Colchicine significantly improved LV-EF, reduced viral load, and decreased inflammatory cell infiltration (ASC⁺, caspase-1⁺, IL-1β⁺ cells) in myocardium and spleen. | Reduced fibrosis markers, cardiac troponin I, and lower collagen deposition. | Preclinical only |

| GRECCO-19 trial, 2020 [147] | 52.4% of a total 105 patients were treated with colchicine | RCT phase 3 | to explore the potential of colchicine to attenuate COVID-19–related myocardial injury | Patients who received colchicine had significantly improved time to clinical deterioration. There were no significant differences in hs-Tn or CRP levels | a significant clinical benefit from colchicine in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 | Cardiac complications of COVID-19 infection |

| NCT05855746 [ https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05855746] | Colchicine vs placebo | RCT phase 3 | Three-hundred adults with acute myocarditis; primary endpoint at 6 months: composite of re-hospitalization, recurrent chest pain, arrhythmias, changes in LGE percentage by CMR | No results, as yet | Results expected post 2028 | Results not yet available |

| CMP-MYTHiC NCT06158698 [https://cdek.pharmacy.purdue.edu/trial/NCT06158698/] |

Colchicine vs placebo | RCT phase 3 | In total 80 adults with chronic inflammatory cardiomyopathy and impaired LV-EF or ventricular arrhythmias to receive colchicine or placebo for 6 months, with outcomes assessed by imaging, biomarkers, and arrhythmic burden. | No results, as yet | Results expected post 2026 | Chronic myocarditis, small population |

| Wohlford GF, et al, 2020 [148] | Dapansutrile (OLT1177) | RCT phase 1B |

Patients with HFrEF, dose escalation, single-center, repeat dose safety and pharmacodynamics study of dapansutrile in stable patients with HFrEF | Improvements in LV-EF [from 31.5% (27.5–39) to 36.5% (27.5–45), P = 0.039] and in exercise time [from 570 (399.5–627) to 616 (446.5–688) seconds, P = 0.039] were seen in the dapansutrile 2000 mg cohort. | Treatment with dapansutrile was well tolerated and safe over a 14-day treatment period. | A study for HFrEF, not specifically in myocarditis |

| Wang et al. 2022 [149] | INF200 (1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-one) | preclinical | Experiments on heart stress in rats | INF200 works by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome, which in turn reduces inflammation and its associated detrimental effects on the heart | Reduced cardiac biomarkers and ischemia–reperfusion injury in diet-induced metabolic heart stress in rats | A study on animal models |

| IL-1 receptor antagonists | ||||||

| CANTOS TRIAL [150] | Canakinumab: IL-1 receptor antagonist given s.c. in dose 50mg, 150 mg, or 300 mg, vs placebo |

RCT phase 3 | A total of 10,061 patients with prior MI and high hsCRP (≥2 mg/L) given s.c. canakinumab at 50 mg, 150 mg, or 300 mg every 3 months |

The 150 mg dose of canakinumab significantly reduced the incidence of recurrent cardiovascular events compared to placebo. |

the canakinumab dose of 150 mg was associated with a reduced occurrence of the primary endpoint, and reduction in IL-6 and CRP levels | A study for myocardial infraction, not specifically in myocarditis |

| MRC-ILA [152] | Anakinra given s.c. IL-1ra vs placebo, 1:1 allocation | RCT phase 2 | 182 patients with NSTEMI; treatment for 14 days; primary endpoint: 7-day CRP | Significant CRP reduction (≈ 50% vs placebo); no difference in 30-day or 3-month MACE. | Lower inflammation; no clinical benefit; unexpected rise in CV events at one-year follow-up | A study for myocardial infraction, not specifically in myocarditis |

| VCU-ART3 [153] | Anakinra 100 mg once daily or twice daily vs placebo | RCT phase 2 | 99 STEMI patients within 12 h of symptom onset; 14-day treatment; primary endpoint: CRP level to day 14; follow-up to 12 months for echocardiographic remodeling and MACE | Not yet fully published, but early phase results showed significant CRP reduction during treatment | Primary: reduced inflammation (CRP AUC); secondary: pending data on LV remodeling and MACE over 12 months. | A study for myocardial infraction, not specifically in myocarditis |

| ARA-MIS Trial (Kerneis et al) [156] | Anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist: IL-1ra) 100 mg vs placebo | RCT phase 2 | 120 patients hospitalized with CMR-proven acute myocarditis, without severe hemodynamic instability or cardiogenic shock | No significant difference from myocarditis complications within 28 days. Significant reduction in systemic inflammatory markers such as CRP and IL-6. | Safety confirmed; well tolerated, but no efficacy signal in low-risk patients | Short course, low-risk population, low incidence of complicated myocarditis in both groups. |

| Lema et al. 2024 [157] | IL1RAP monoclonal antibody vs placebo, or vs anakinra/IL-1Ra | Preclinical, mice model | Induced CVB3-mediated myocarditis or experimental autoimmune myocarditis in mice, followed by the treatment with anti-mouse IL1RAP monoclonal antibody vs placebo, or IL-1Ra treatment | IL1RAP blockade with a monoclonal antibody, compared with placebo and IL1Ra, reduced inflammatory monocytes, T cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in the heart in CVB3-mediated VMC, and preserved heart function on echocardiography in autoimmune myocarditis | The effect on the reduction in inflammation was higher in IL1RAP blockade compared with anti-IL-1Ra treatment alone, and placebo | Study in viral and autoimmune myocarditis |

| Interleukin-18 inhibitors | ||||||

| Li et al. 2021 [158] | Anti–IL-1R7 monoclonal antibody vs isotype control | Preclinical, in vitro human cells + in vivo mouse models | Assessed suppression of IL-18–mediated signaling in human PBMCs and whole blood; in mice, evaluated protection against LPS- or Candida-induced hyperinflammation | Blockade of IL-1R7 strongly inhibited IL-18–induced NF-κB activation and downstream cytokines (IFNγ, IL-6, TNFα) in mice, significantly reduced systemic inflammation and protected tissues (lung, liver) from LPS-induced injury | Demonstrated proof-of-concept that IL-1R7 blockade effectively attenuates IL-18–driven inflammation. | No direct myocarditis model used. |

| Jiang L et al. 2024 [159] | anti-human IL-1R7 antibody | Mice model | A novel humanized monoclonal antibody which specifically blocks the activity of human IL-18 and its inflammatory signaling in human cell and whole blood cultures was tested in hyperinflammation in acute lung injury model | In the current study, anti-IL-1R7 supressed LPS-induced inflammatory cell infiltration in lungs and inhibited subsequent IFN- γ production | An IL-1R7 antibody protects mice from LPS-induced tissue and systemic inflammation | Aimed to combat macrophage activation syndrome and COVID-19 infection |

| Study | Medication / comparator | Type of the study | Study design | Main findings | Outcomes | Remarks / limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARNI | ||||||

| PARADIGM-HF [165] | Sac/Val vs. enalapril | RCT phase 3 | In total 8442 patients with chronic HF, NYHA class II–IV symptoms, an elevated plasma BNP or NT-proBNP level, and an LVEF of ≤35% | The primary outcome of CVD or hospitalization for HF was significantly lower in ARNI arm compared with enalapril arm (21.8% vs 26.5%; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.73 to 0.87; P<0.001). | ARNI use reduced risk of CVD by 16%, hospitalization for HF by 21% and decreased the symptoms and physical limitations of HF. | Study terminated earlier due to high benefits from ARNI use. Only 0.7% of patients in NYHA functional class IV symptoms |