Submitted:

20 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Trace Elements

1.2. Trace elements and Metabolism

1.3. Trace Elements and Environmental Factors

1.4. Trace Elements with Pathological Consequences

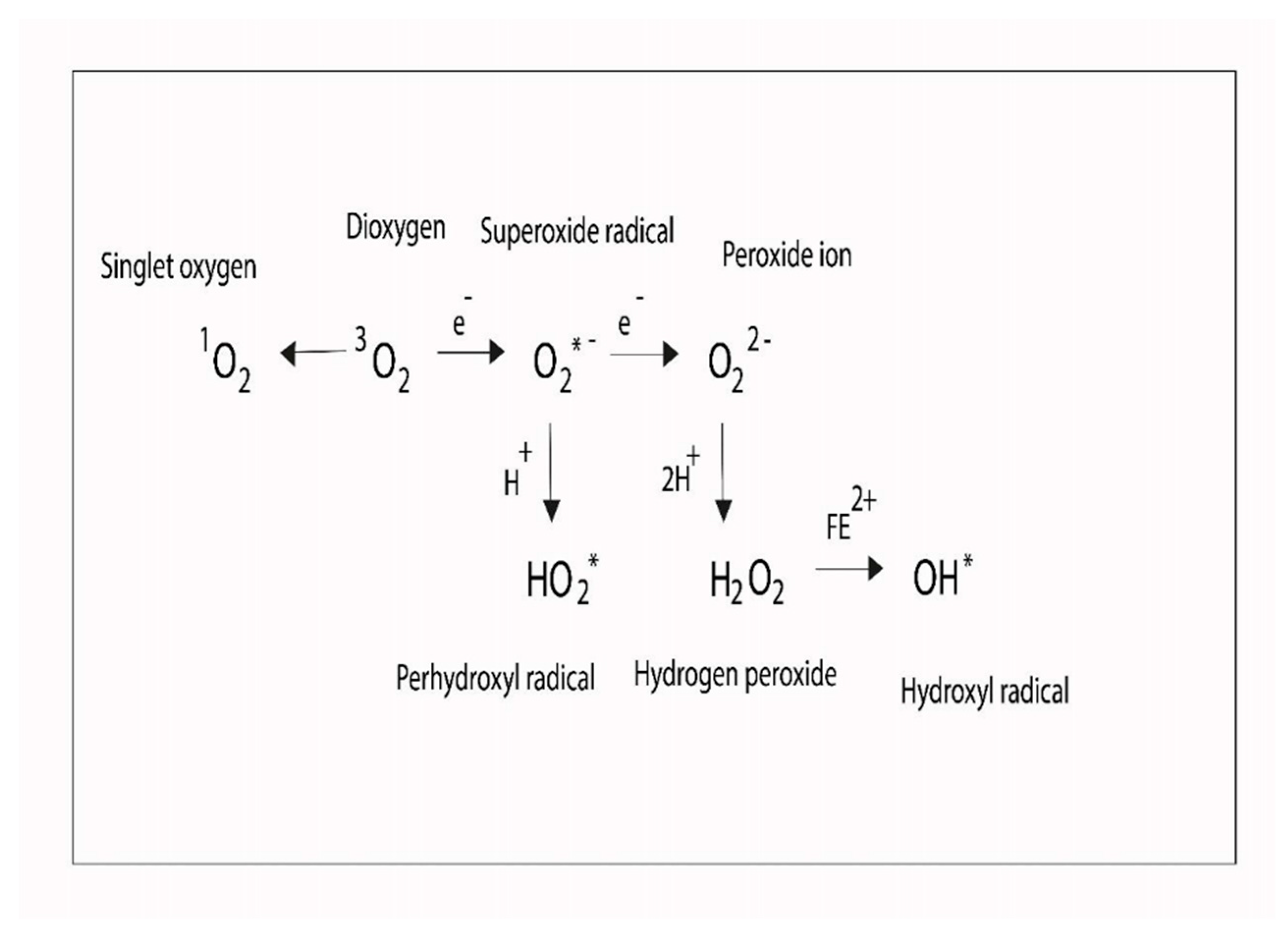

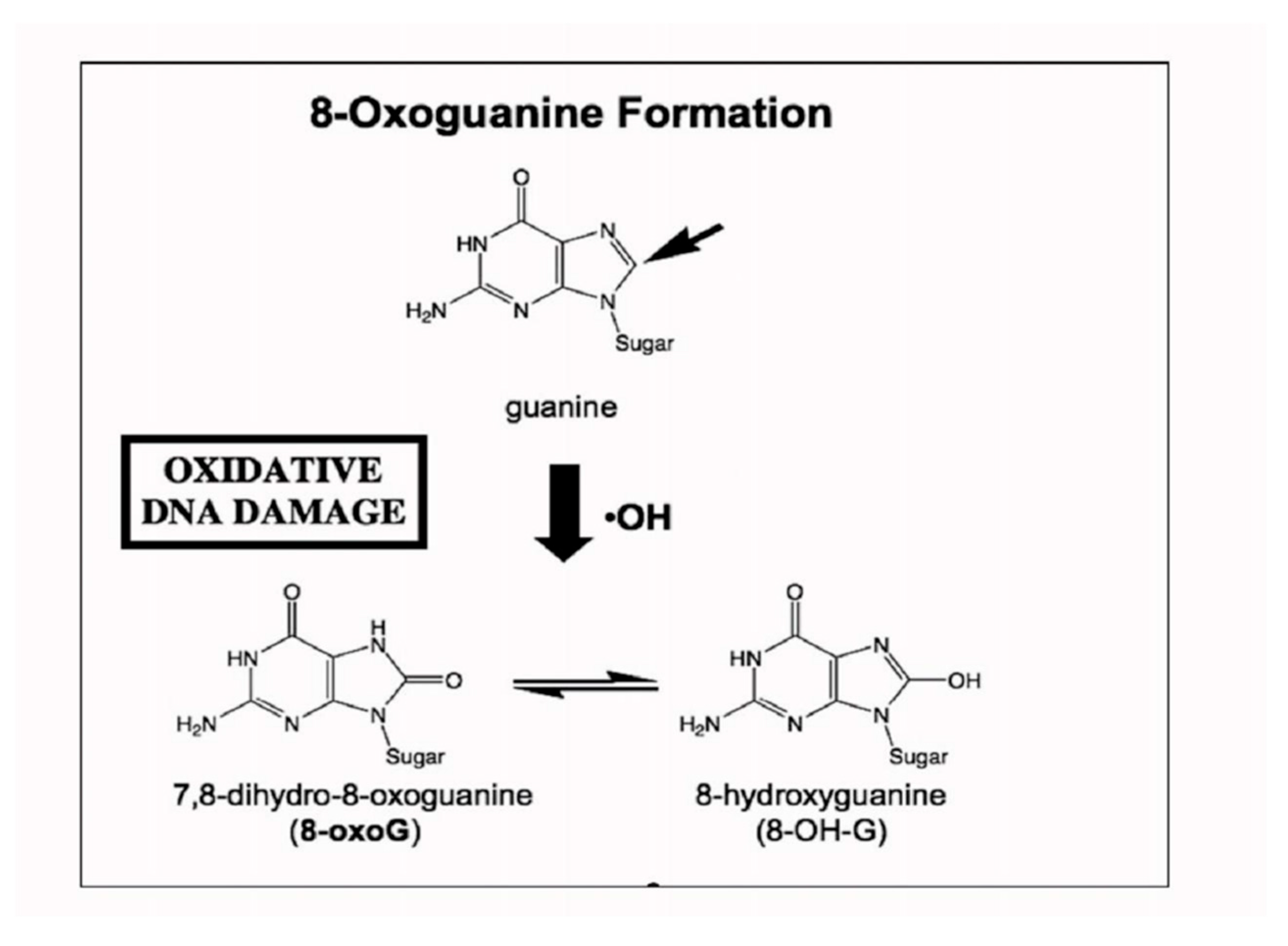

1.5. Trace Element Metabolism and Redox Imbalance

2. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Authors’ information

Ethics Statements

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and nutrition aboard [FNA], National Research Council. Recommended Dietary Allowances. 10th ed. Washington D.C. National Academy Press, 1989.

- Irlam, J.H.; Visser, M.M.; Rollins, N.N.; Siegfried, N. Micronutrient supplementation in children and adults with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010, 8, CD003650. [Google Scholar]

- Henche Morilla, A.L.; Romero Montero, C.; Llorente González, C. Levels of oligo-elements and trace elements in patients at the time of admission in intensive care units. Nutr Hosp 1990, 5, 338–344. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, Humphrey John Moule. Trace elements in biochemistry. Academic Press 1966, ISBN 9780121209506.

- Shier Butler; Lewis David; Jackie Ricki. Hole’s Human Anatomy. Fourteenth Edition; McGraw Hill Education: New York, 2016; p. 59. ISBN 978-0-07-802429-0. [Google Scholar]

- Stephanie L Raehsler; Rok Seon Choung; Eric V Marietta; et al. Accumulation of heavy metals in people on a gluten-free diet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 16, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah Swayze; Michael Rotondi; Jennifer L Kuk. The association between blood and urinary concentrations of metal metabolites, obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia among US Adults: NHANES 1999-2016. J Environ Public Health 2021, 2358060, eCollection 2021. [CrossRef]

- Can Qu; Ruixue Huang. Linking the low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol [LDL] level to arsenic acid, dimethylarsinic, and monomethylarsonic: Results from a National Population-Based Study from the NHANES, 2003-2020. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam Khairul; Qian Qian Wang; Yu Han Jiang; et al. Metabolism, toxicity and anticancer activities of arsenic compounds. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 23905–23926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneka Hoonjan; Vaibhav Jadhav; Purvi Bhatt. Arsenic trioxide: Insights into its evolution to an anticancer agent. J Biol Inorg Chem 2018, 23, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandita Medda, Subrata Kumar De, Smarajit Maiti. Different mechanisms of arsenic related signaling in cellular proliferation, apoptosis and neo-plastic transformation. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2021, 208, 111752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadi Esmaeili; Ava Safaroghli-Azar; Atieh Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi; et al. Activation of PPARγ intensified the effects of arsenic trioxide in acute promyelocytic leukemia through the suppression of PI3K/Akt pathway: Proposing a novel anticancer effect for pioglitazone. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2020, 122, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin Wang; Bhramar Mukherjee; Sung Kyun Park. Associations of cumulative exposure to heavy metal mixtures with obesity and its comorbidities among U.S. adults in NHANES 2003-2014. Environ Int 2018, Pt 1, 683–694. [CrossRef]

- Xu Yao; Xu Steven Xu; Yaning Yang; et al. Stratification of population in NHANES 2009-2014 based on exposure pattern of lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic and their association with cardiovascular, renal and respiratory outcomes. Environ Int 2021, 149, 106410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alison P Sanders; Matthew J Mazzella; Ashley J Malin; et al. Combined exposure to lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic and kidney health in adolescents age 12-19 in NHANES 2009-2014. Environ Int 2019, 131, 104993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatanaidu Karri; Marta Schuhmacher; Vikas Kumar. Heavy metals [Pb, Cd, As and MeHg] as risk factors for cognitive dysfunction: A general review of metal mixture mechanism in brain. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2016, 48, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatanaidu Karri; David Ramos; Julia Bauzá Martinez; et al. Differential protein expression of hippocampal cells associated with heavy metals [Pb, As, and MeHg] neurotoxicity: Deepening into the molecular mechanism of neurodegenerative diseases. J Proteomics 2018, 187, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatanaidu Karri; Marta Schuhmacher Professor; Vikas Kumar. A systems toxicology approach to compare the heavy metal mixtures [Pb, As, MeHg] impact in neurodegenerative diseases. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 139, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emel Koseoglu; Rahmi Koseoglu; Murat Kendirci; et al. Trace metal concentrations in hair and nails from Alzheimer’s disease patients: Relations with clinical severity. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2017, 39, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashi Himoto; Tsutomu Masaki. Current trends of essential trace elements in patients with chronic liver diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, S.K.; Torres-Espínola, F.J.; García-Valdés, L.; et al. The impacts of maternal iron deficiency and being overweight during pregnancy on neurodevelopment of the offspring. Br J Nutr 2017, 118, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, B.; Ciccarelli, S.; Agostino, R.; et al. Trace elements, oxidative status and antioxidant capacity as biomarkers in very low birth weight infants. Environ Res 2017, 156, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnieszka Kamińska; Giovanni Luca Romano; Robert Rejdak; et al. Influence of trace elements on neurodegenerative diseases of the eye-the glaucoma model. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maha M Al-Bazi; Taha A Kumosani; Abdulrahman L Al-Malki; et al. Association of trace elements abnormalities with thyroid dysfunction. Afr Health Sci 2021, 21, 1451–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksandar Stojsavljević; Branislav Rovčanin; Jovana Jagodić; et al. Alteration of trace elements in multinodular goiter, thyroid adenoma, and thyroid cancer. Biol Trace Elem Res 2021, 199, 4055–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabian, F.; Mohri, M.; Heidarpour, M. Relationships between oxidative stresses, haematology and iron profile in anaemic and non-anaemic calves. Vet Rec 2017, 181, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, C.O.; da Cunha, J.; Levy, D.; et al. Hepcidin: Homeostasis and diseases related to iron metabolism. Acta Haematol 2017, 137, 220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, T.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Haloperidol, a sigma receptor 1 antagonist, promotes ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 491, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusnir, R.; Imberti, C.; Hider, R.C.; et al. Hydroxypyridinone chelators: From iron scavenging to radiopharmaceuticals for PET imaging with gallium-68. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, E116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, B.; Sterling, J.; Song, Y.; et al. Conditional müller cell ablation leads to retinal iron accumulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017, 58, 4223–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Comin-Colet, J.; de Francisco, A.; et al. Iron deficiency across chronic inflammatory conditions: International expert opinion on definition, diagnosis, and management. Am J Hematol 2017, 92, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehou, S.; Shahrokhi, S.; Natanson, R.; et al. Antioxidant and trace element supplementation reduce the inflammatory response in critically ill burn patients. J Burn Care Res Aug 2017, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çavuşoğlu, Y.; Altay, H.; Çetiner, M.; et al. Iron deficiency and anemia in heart failure. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars 2017, 45, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xin Yang; Zhe Tang; Jing Li; et al. Esophagus cancer and essential trace elements. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1038153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehar Iqbal; Inayat Ali. Dietary trace element intake and risk of breast cancer: A mini review. Biol Trace Elem Res 2022, 200, 4936–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.H.; Kandil, S.M.; Zeid, M.S.; et al. Kidney injury in infants and children with iron-deficiency anemia before and after iron treatment. Hematology 2017, 22, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, T.D.; Wood, J.C. How we manage iron overload in sickle cell patients. Br J Haematol 2017, 177, 703–716. [Google Scholar]

- Kraml, P. The role of iron in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Physiol Res 2017, 66, S55–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamnongkan, W.; Thanan, R.; Techasen, A.; et al. Upregulation of transferrin receptor-1 induces cholangiocarcinoma progression via induction of labile iron pool. Tumour Biol 2017, 39, 1010428317717655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarda, C.C.D.; Santiago, R.P.; Fiuza, L.M.; et al. Heme-mediated cell activation: The inflammatory puzzle of sickle cell anemia. Expert Rev Hematol 2017, 10, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crielaard, B.J.; Lammers, T.; Rivella, S. Targeting iron metabolism in drug discovery and delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017, 16, 400–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, K.P.; Oliveira, S.R.; Kallaur, A.P.; et al. Disease progression and oxidative stress are associated with higher serum ferritin levels in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2017, 373, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajbouj, K.; Shafarin, J.; Abdalla, M.Y.; et al. Estrogen-induced disruption of intracellular iron metabolism leads to oxidative stress, membrane damage, and cell cycle arrest in MCF-7 cells. Tumour Biol 2017, 39, 1010428317726184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzamiglio, S.; De Bortoli, M.; Taverna, E.; et al. Expression of iron-related proteins differentiate non-cancerous and cancerous breast tumors. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franěk, T.; Kotaška, K.; Průša, R. Manganese and selenium concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of seriously ill children. J Clin Lab Anal 2017, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian L Görlich; Qian Sun; Viola Roggenkamp; et al. Selenium status in paediatric patients with neurodevelopmental diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstead, H.H.; Prasad, A.S.; Penland, J.G.; et al. Zinc deficiency in Mexican American children: Influence of zinc and other micronutrients on T cells, cytokines, and antiinflammatory plasma proteins. Am J Clin Nutr 2008, 88, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, K.Z.; Rosado, J.L.; Montoya, Y.; et al. Effect of vitamin A and zinc supplementation on gastrointestinal parasitic infections among Mexican children. Pediatrics 2007, 120, e846–e855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalpando, S.; Pérez-Expósito, A.B.; Shamah-Levy, T.; et al. Distribution of anemia associated with micronutrient deficiencies other than iron in a probabilistic sample of Mexican children. Ann Nutr Metab 2006, 50, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, A. Minerals and trace elements in milk. Adv Food Nutr Res 1992, 36, 209–252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Das, R.R. Zinc for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011, 16, CD001364. [Google Scholar]

- Vernacchio, L.; Kelly, J.P.; Kaufman, D.W.; et al. Vitamin, fluoride, and iron use among US children younger than 12 years of age: Results from the Slone Survey 1998-2007. J Am Diet Assoc 2011, 111, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi CH, Akin O., Harmanci K; et al. (2011) Serum heavy metal and antioxidant element levels of children with recurrent wheezing. Allergol Immunopathol [Madr] Jan 12. Epub ahead of print.

- Van Santen, S.; de Mast, Q.; Luty, A.J.; et al. Iron homeostasis in mother and child during placental malaria infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011, 84, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.A.; Soofi, S.B.; Bhutta, Z.A. Effect of zinc in tablet and suspension formulations in the treatment of acute diarrhoea among young children in an emergency setting of earthquake affected region of Pakistan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2010, 20, 837–838. [Google Scholar]

- Troesch, B.; van Stujivenberg, M.E.; Smuts, C.M.; et al. A micronutrient powder with low doses of highly absorbable iron and zinc reduces iron and zinc deficiency and improves weight-for-age Z-scores in South African children. J Nutr 2011, 141, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, P.; Murray-Kolb, L.E.; Khatry, S.K.; et al. Prenatal micronutrient supplementation and intellectual and motor function in early school-aged children in Nepal. JAMA 2010, 304, 2716–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhsen, K.; Barak, M.; Henig, C.; et al. Is the association between Helicobacter pylori infection and anemia age dependent? Helicobacter 2010, 15, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habis, A.; Hobson, W.L.; Greenberg, R. Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis in a toddler with iron deficiency anemia. Pediatr Emerg Care 2010, 26, 848–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasricha, S.R.; Flecknoe-Brown, S.C.; Allen, K.J.; et al. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anaemia: A clinical update. Med J Aust 2010, 193, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlet, J.B.; Hermine, O.; Darnige, L.; et al. Iron-deficiency anemia in Castleman disease: Implication of the interleukin 6/hepcidin pathway. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e1608–e1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelishadi, R.; Hashemipour, M.; Adeli, K.; et al. Effect of zinc supplementation on markers of insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation among prepubescent children with metabolic syndrome. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2010, 8, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tascilar, M.E.; Ozgen, I.T.; Abaci, A.; et al. Trace elements in obese Turkish children. Biol Trace Elem Res.

- Riojas-Rodríguez, H.; Solís-Vivanco, R.; Schilmann, A.; et al. Intellectual function in Mexican children living in a mining area and environmentally exposed to manganese. Environ Health Perspect 2010, 118, 1465–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahyar, A.; Ayazi, P.; Fallahi, M.; et al. Correlation between serum selenium level and febrile seizures. Pediatr Neurol 2010, 43, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gara, S.N.; Madaki, A.J.; Thacher, T.D. A comparison of iron and folate with folate alone in hematologic recovery of children treated for acute malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010, 83, 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, W.; Dardenne, M. Nutritional imbalances and infections affect the thymus: Consequences on T-cell-mediated immune responses. Proc Nutr Soc 2010, 69, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, M.; Hotz, C.; Zeder, C.; et al. A comparison of the bioavailability of ferrous fumarate and ferrous sulfate in non-anemic Mexican women and children consuming a sweetened maize and milk drink. Eur J Clin Nutr 2011, 65, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylewski, M.L.; Bender, J.C.; Smith, A.M.; et al. The selenium status of pediatric patients with burn injuries. J Trauma 2010, 69, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuma, Y.; Nouso, K.; Makino, Y.; et al. Clinical trial: Oral zinc in hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010, 32, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, H.I.; Kazi, T.G.; Kazi, N.; et al. Evaluation of essential trace and toxic elements in biological samples of normal and night blindness children of age groups 3-7 and 8-12 years. Biol Trace Elem Res 2010. Sep 4. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Remer, T.; Johner, S.A.; Gärtner, R.; et al. Iodine deficiency in infancy - a risk for cognitive development. Dtsch Med Wochenschr, 1551. [Google Scholar]

- Balay, K.S.; Hawthorne, K.M.; Hicks, P.D.; et al. Orange but not apple juice enhances ferrous fumarate absorption in small children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010, 50, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, R.B.; Fröehlich, P.E.; Pitrez, E.H.; et al. MR findings of the brain in children and adolescents with portal hypertension and the relationship with blood manganese levels. Neuropediatrics 2010, 41, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, N.V.; Raymond, L.J. Dietary selenium’s protective effects against methylmercury toxicity. Toxicology 2010, 278, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazy, A.A.; Zaher, M.M.; Abd El-Hafez, M.A.; et al. Relation between anemia and blood levels of lead, copper, zinc and iron among children. BMC Res Notes 2010, 12, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondo, M.; Moreno, J.; Casado, M.; et al. Selenium concentration in cerebrospinal fluid samples from a pediatric population. Neurochem Res 2010, 35, 1290–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alireza Mohammadi; Ehsan Rashidi; Vahid Ghasem Amooeian. Brain, blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and serum biomarkers in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2018, 265, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarah Rehou; Shahriar Shahrokhi; Rimona Natanson; et al. Antioxidant and trace element supplementation reduce the inflammatory response in critically ill burn patients. J Burn Care Res 2018, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran Shayganfard. Are essential trace elements effective in modulation of mental disorders? Update and perspectives. Biol Trace Elem Res 2022, 200, 1032–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanni Forte; Beatrice Bocca; Andrea Pisano; et al. Trace elements in sputum as biomarkers for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The levels of trace. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacewicz, M.; Socha, K.; Soroczyńska, J.; et al. Concentration of selenium, zinc, copper, Cu/Zn ratio, total antioxidant status and c-reactive protein in the serum of patients with psoriasis treated by narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy: A case-control study. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2017, 44, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . Shahidi-Dadras, M.; Namazi, N.; Younespour, S. Comparative analysis of serum copper, iron, ceruloplasmin, and transferrin levels in mild and severe psoriasis vulgaris in Iranian patients. Indian Dermatol Online J 2017, 8, 250–253. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Cao, H.; Luo, J.; et al. Effects of molybdenum and cadmium on the oxidative damage and kidney apoptosis in Duck. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2017, 145, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, F.N.C.; Fermino, B.L.; Haskel, M.V.L.; et al. The relationship between copper, iron, and selenium levels and alzheimer disease. Biol Trace Elem Res 2018, 181, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirksen, K.; Spee, B.; Penning, L.C.; et al. Gene expression patterns in the progression of canine copper-associated chronic hepatitis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meramat, A.; Rajab, N.F.; Shahar, S.; et al. DNA damage, copper and lead associates with cognitive function among older adults. J Nutr Health Aging 2017, 21, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogórek, M.; Gąsior, Ł.; Pierzchała, O.; et al. Role of copper in the process of spermatogenesis. Postepy Hig Med Dosw 2017, 71, 663–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.W.; Shao, Y.Z.; Zhao, H.J.; et al. Analysis of 28 trace elements in the blood and serum antioxidant status in chickens under arsenic and/or copper exposure. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2017, 24, 27303–27313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, P.; Nobakht, M.; Mirhafez, S.R.; et al. Alterations in lipid profile, zinc and copper levels and superoxide dismutase activities in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. Am J Med Sci 2017, 353, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahi, G.A.; Boyvin, L.; Méité, S.; et al. Assessments of serum copper and zinc concentration, and the Cu/Zn ratio determination in patients with multidrug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis [MDR-TB] in Côte d’Ivoire. BMC Infect Dis 2017, 17, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak Alghamdi; Janelle Gutierrez; Slavko Komarnytsky. Essential minerals and metabolic adaptation of immune cells. Nutrients 2022, 15, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Jing Huang; Guang-Xian Nan. Oxidative stress-induced angiogénesis. J Clin Neurosc 2019, 63, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joaquim Rovira; Anna Hernández-Aguilera; Fedra Luciano-Mateo; et al. Trace elements and paraoxonase-1 activity in lower extremity artery disease. Biol Trace Elem Res 2018, 186, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazıroğlu, M.; Muhamad, S.; Pecze, L. Nanoparticles as potential clinical therapeutic agents in Alzheimer’s disease: Focus on selenium nanoparticles. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2017, 10, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltaci, A.K.; Yuce, K.; Mogulkoc, R. Zinc metabolism and metallothioneins. Biol Trace Elem Res 2018, 183, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, M.; Shentu, Y.P.; Zeng, J.; et al. Zinc mediates the neuronal activity-dependent anti-apoptotic effect. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doboszewska, U.; Wlaź, P.; Nowak, G. Zinc in the monoaminergic theory of depression: Its relationship to neural plasticity. Neural Plast 2017, 3682752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharaf, M.S.; Stevens, D.; Kamunde, C. Zinc and calcium alter the relationship between mitochondrial respiration, ROS and membrane potential in rainbow trout [Oncorhynchus mykiss] liver mitochondria. Aquat Toxicol 2017, 189, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebke Alker; Hajo Haase. Zinc and sepsis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariaee, N.; Farid, R.; Shabestari, F.; et al. Trace elements status in sera of patients with allergic asthma. Rep Biochem Mol Biol 2016, 5, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.; Zhang, X.; Xie, L. Prognostic value of serum zinc levels in patients with acute HC/zinc chloride smoke inhalation. Medicine [Baltimore] 2017, 96, e8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanganeh, N.; Siahpoushi, E.; Kheiripour, N.; et al. Brucellosis causes alteration in trace elements and oxidative stress factors. Biol Trace Elem Res 2018, 182, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H.; Mohammadi, G.R.; Maleki, M.; et al. Relationships between oxidative stress, liver, and erythrocyte injury, trace elements and parasite burden in sheep naturally infected with dicrocoelium dendriticum. Iran J Parasitol 2017, 12, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Eljaoudi, R.; Elomri, N.; Laamarti, M.; et al. Antioxidants status in type 2 diabetic patients in Morocco. Turk J Med Sci 2017, 47, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Mishra, B.B. Study of lipid peroxidation, nitric oxide end product, and traceelement status in type 2 diabetes mellitus with and without complications. Int J Appl Basic Med Res 2017, 7, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniela Cannas; Eleonora Loi; Matteo Serra; et al. Relevance of essential trace elements in nutrition and drinking water for human health and autoimmune disease risk. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Zinc protects against cadmium-induced toxicity by regulating oxidative stress, ions homeostasis and protein synthesis. Chemosphere 2017, 188, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slepchenko, K.G.; Lu, Q.; Li, Y.V. Cross talk between increased intracellular zinc [Zn2+] and accumulation of reactive oxygen species in chemical ischemia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2017, 313, C448–C459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, S.I. Metallothionein is a potential therapeutic strategy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Pharm Des 2017, 23, 5001–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanchan Karki; Shahi, K.S.; Rashmi Bisht; et al. Biochemical investigation of tissue oxidative stress and angiogenesis with associated trace elements in breast disease patients in Uttarakhand, India. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 2019, 38, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Major Elements [mg/L] | Trace Elements [µg/L] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cl- | 19,295 ± 135 | Mn | 5.235 ± 0.046 |

| Na | 10,690 ± 110 | Fe | 1.773 ± 0.012 |

| SO₄²⁻ | 2701 ± 37 | Zn | 0.785 ± 0.002 |

| Ca | 416 ± 15 | Cu | 0.635 ± 0.025 |

| K | 390 ± 10 | V (Vanadium) | 1.45 ± 0.7 |

| HCO3⁻ | 145 ± 12 | Ni (Nickel) | 0.327 ± 0.012 |

| Mg | 128 ± 5 | Pb | 0.045 ± 0.025 |

| Br | 62 ± 5 | Cd (Cadmium) | 0.035 ± 0.008 |

| BO3−3 (Borate) | 27 ± 2 | Hg | Undetected |

| Sr (Strontium) | 13.2 ± 0.5 | As (Arsenic) | Undetected |

| F⁻ | 1.35 ± 0.02 | ||

| Symbol | Biological Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Zn | Joint tx involving Zn and micronutrients elevates neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio of T helper cells/CD8-positive T cells, and of CD4[+] to CD8[+] and CD4[+]CD45RA[+] to CD4[+]CD45RO[+]. | [47] |

| Zn | Retinol in combination wih Zn decreases Giardiasis. Zn intake elevates the incidence of Ascaris lumbricoides and lessens Entamoeba histolytica-associated diarrhea. | [48] |

| Fe | Erythrocytopenia is linked to Iron-depleted state, lower concentration do folic acid and retinol deficiency. | [49] |

| Se | Mineral and micronutrients proportions in infant formulas for full-term infants are generally higher than in human breast milk. However, Se levels in these formulas is far from adequate and needs to be increased in some formulas. | [50] |

| Zn | The incidence rate ratio [IRR] of developing a cold [IRR 0.64; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.88] [P = 0.006], school absence [P = 0.0003] and prescription of antibiotics [P < 0.00001] was lower in people using Zn supplement. | [51] |

| Fe | Approximately a quarter of US children less than 12-year old, and 30% of 2-year-olds, use dietary supplements, F- and Fe at least once a week. | [52] |

| Se, Zn | Increeased blood Pb and Hg, and Elevated levels of serum lead and mercury, and Zn and Se deficiency could infer antioxidant system alterations in children with recurrent wheezing. | [53] |

| Fe | Maternal iron regulatory hormone did not show a statistically significant change in thee course of infection in the placenta as well as in erythropenia. | [54] |

| Zn | Zn diminishes the occurrence of diarrhea as well as optimizes recovery outcomes of this sickness. | [55] |

| Fe, Zn | The powder form of these micronutrients promotes high native iron absorption in cereal/legume-based complementary foods. | [56] |

| Zn | Prenatal iron/folic acid supplementation has been positively linked with some features of cognitive capacity, e.g., active memory, response inhibition and fine motor functioning in children living in iron-deficient areas. | [57] |

| Zn | Zn is not affected by human immunodeficiency infection in both children and adults, rather it is found to be benefitial in these patients with diarrhea. | [58] |

| Fe | H. pylori infection is linked with increased rate of anemia in school children independently of socioeconomic variables. | [59] |

| Fe | Severe anemia due to inadequate dietary iron intake is associated with sagittal sinus venous thrombosis in children. | [60] |

| Fe | Oral iron therapy, in appropriate doses and for a sufficient duration, is an effective first-line strategy for most patients. The same happens in selected patients for whom intravenous [IV] iron therapy is indicated. | [61] |

| Fe | Iron-regulatory hormone (hepcidin) production in humans is regulated by Interleukin-6 (IL-6). This means that iron deficiency is a causal link between IL-6 and anemia of chronic disease. | [62] |

| Zn | Zinc supplement exhibits a considerable diminution in the mean BMI. However, this promising benefit has not been explore in obese children and needs to be an object of study. | [63] |

| Se, Fe | These micronutrients probably induce changes in the profile of trace elements in the blood of patients with childhood obesity. | [64] |

| Mn | Environmental inhalation exposure to manganese is negatively correlated with cognitive capacity in school children. | [65] |

| Se | Se blood level in febrile-seizure pediatric patients was substantially decreased when compared with nonseizure control group. This suggests a probable link between low serum selenium concentration and simple febrile seizures. | [66] |

| Fe | Iron administration improved hematologic recovery in children with malarial anemia. Children 6-60 months of age with blood film-positive malaria and anemia [hematocrit < 33%] should receive iron [2 mg/kg/day] plus folate [5 mg/day] or folate alone. | [67] |

| Zn | A combined vitamin and micronutrients can induce deep alterations in the thymus as seen in thymus-zinc associated atrophy. | [68] |

| Fe | In healthy children and those with non-anemic iron deficient, iron(II) fumarate and iron(II) sulfate are well absorbed and could serve as a useful fortification compound for complementary foods designed to prevent iron deficiency. | [69] |

| Se | In children with burns, selenium status is decreased showing that selenium intake for healthy children is likely insufficient for this population. | [70] |

| Zn | In hepatic encephalopathy, Zn administrationconstitutes an effective treatment and improves the quality of life of these patients. | [71] |

| Zn | In the scalp and blood of children suffering from night blindness, Zn, Ca, K, and Mg levels were found to be low. | [72] |

| I | It is recommended that iodine intake of 4-month old infants should be increased from the current dose of 40 µg/d to at least 60 µg/d. | [73] |

| Fe | The administration of ferrous fumarate with orange juice enhances the absorption of iron by almost 2-folds in more than six-year old children. | [74] |

| Mn | In the basal ganglia of patients with portal hypertension, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain depicted high T1 hyperintensity frequency [64%] correlating positively with blood manganese levels. | [75] |

| Se | Studies of populations exposed to Methyl-Mercury [MeHg] by eating Se-rich ocean fish observed improved child IQs instead of harm. | [76] |

| Fe | Lead level >/= 10 µg/dl strongly correlated with anemia, decreased iron absorption and affectation of hematological parameters. High serum Pb levels were linked with decreased blood iron and ferritin. | [77] |

| Se | Selenium concentrations in Cerebrum Spinal Fluid (CSF) were 32 times lower versus plasma values. There was an association observed between CSF Se and GPX activity. | [78] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).