3.1. Geospatial Incidence of NTDs in Para State, 2016-2022

Spatio-temporal analysis has become an essential tool for understanding the dynamics of infectious diseases across different geographical contexts. This study on Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) highlights distinct patterns of case concentration, influenced by environmental, climatic, and socio-economic factors.

Diseases such as Dengue, Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL), and Leprosy showed high standard deviations, indicating considerable variation in incidence across different locations or time periods. Diseases such as Tuberculosis (TB) and Schistosomiasis exhibited lower relative variation, suggesting a more uniform distribution (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Incidence rates of NTDs in the state of Para.

Table 1.

Incidence rates of NTDs in the state of Para.

| DTN |

Incidence* (min) |

Incidence* (max.) |

Average |

St. Dv. |

Moran I |

| ACD |

1.90 |

342.50 |

172.20 |

240.84 |

0.645 |

| Dengue |

5.00 |

7,626.00 |

3,815.50 |

5,388.86 |

0.287 |

| VL |

2.95 |

818.00 |

410.48 |

576.32 |

0.312 |

| CL |

1.75 |

4,174.00 |

2,087.88 |

2,950.22 |

0.528 |

| Schistosomiasis |

0.46 |

3.40 |

1.93 |

2.07 |

0.018 |

|

TB♦

|

12.50 |

31.19 |

21.85 |

13.21 |

0.206 |

| Leprosy |

26.00 |

2,386.00 |

1,206.00 |

1,668.00 |

0.228 |

In

Table 2, the categorisation by clusters—High-High, Low-High, High-Low, and Low-Low—allows for the identification of high-risk areas, transitional zones, and regions of low incidence, contributing to a better understanding of the geographical distribution of diseases.

Dengue, VL, CL, Leprosy, TB, ACD, and Schistosomiasis all presented High-High clusters, indicating regions with high incidence surrounded by similarly affected areas. The southeast of Pará stands out as an epicentre for multiple diseases, particularly Dengue and Leishmaniasis. Since the 80s, sustainable dengue control in Brazil requires urban infrastructure improvements, technological innovation, and community engagement and Urbanization, poor sanitation, and high population density have created ideal conditions for

Aedes aegypti proliferation[

12]. The southeastern Pará, Brazil, urbanized rapidly due to migration, strategic river location, and extractive industries like rubber, nuts, and mining since the 20th century[

13].

Leprosy and TB, diseases associated with poverty and urbanisation, showed concentration in the metropolitan region of Belém. Leprosy remains a public health concern in Tucuruí, with frequent cases among youth and working adults. Delayed diagnoses and disabilities highlight the need for education, early detection, and professional training[

14].

Low-High clusters indicate municipalities with low incidence surrounded by areas of high incidence, suggesting epidemiological transition zones. Examples include the southeast of Pará for VL and Dengue, and the northeast for TB.

Low-Low clusters represent low-risk areas, encompassing municipalities and neighbouring regions with low incidence rates. These cover a large portion of Pará’s mesoregions, including the metropolitan region of Belém and the Baixo Amazonas. Some municipalities—such as Bagre, Bragança, Mãe do Rio, Redenção, Santa Izabel do Pará, São Sebastião da Boa Vista, and Vigia—did not present significant data, which may indicate absence of cases, underreporting, or limitations in data collection.

Table 2.

Municipalities that showed clusters and statistical significance for the incidence of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) in the state of Pará between 2016 and 2022.

Table 2.

Municipalities that showed clusters and statistical significance for the incidence of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) in the state of Pará between 2016 and 2022.

| Clusters |

Dengue |

Visceral Leishmaniasis |

Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

Leprosy |

Tubersulosis♦ |

Acute Chagas Disease |

Schistosomiasis |

| High - High |

12 municipalities: SoutheastofPará |

10 municipalities: Southeast of Pará |

13 municipalities: Baixo amazonas |

7 municipalities: Southeast of Pará |

8 municipalities: Metropolitan of Belém |

13 municipalities: Metropolitan of Belém |

3 municipalities: Southeast of Pará |

| Low - High |

6 municipalities: Southeast e Southwestern of Pará |

3 municipalities: Southeast of Pará |

2 municipalities: Southeast of Pará |

5 municipalities: Southeast of Pará e Metropolitan of Belém |

3 municipalities: Nordeste paraense |

Afua, Mocajuba, Ponta Pedras |

8 municipalities: Southeast of Pará |

| Low - Low |

28 municipalities: região Metropolitan of Belém. |

24 municipalities: Southwestern of Pará e baixo Amazonas |

50 municipalities: all mesoregions |

35 municipalities: all mesoregions |

municipalities: Southeast of Pará |

8 municipalities: Southeast e Southwestern of Pará |

7 municipalities: Southeast of Pará |

| High - Low |

inhagapi |

Garrafão do Norte |

NOT REPORTED |

NOT REPORTED |

Breves, Marabá, Redenção, Santa Cruz of Arari, Santarém, Tucuruí |

NOT REPORTED |

Bagre, Bragança, Mãe do Rio, Redenção, Santa Izabel of Pará, São Sebastião da Boa Vista, Vigia |

| P value |

Dengue |

Visceral Leishmaniasis |

Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

Leprosy |

Tubersulosis |

Acute Chagas Disease |

Schistosomiasis |

| 0.05 |

36 municipalities |

32 municipalities |

31 municipalities |

39 municipalities |

19 municipalities |

38 municipalities |

10 municipalities |

| 0.01 |

14 municipalities |

Santarém, São Geraldo do Araguaia, Piçarra, Xinguara, Iguarape Asul, Castanhal, Bannach, Breves |

21 municipalities |

10 municipalities |

Inhangapi, Marabá, Piçarra, Portel, Xinguara |

9 municipalities |

Parauapebas, Dom Eliseu |

| 0.001 |

Anajás,Bagre, Breves, Redenção, Rio Maria |

Garrafão do Norte, Floresta do Araguaia, Curionópolis |

15 municipalities |

Santarém |

Benevides, Breves, Santa Bárbara do Pará, Santo Antônio do Tauá |

Santarém |

Bragança, Mãe do Rio, Redenção, Santa Izabel do Pará, São Sebastião da Boa Vista, Vigia, Bagre |

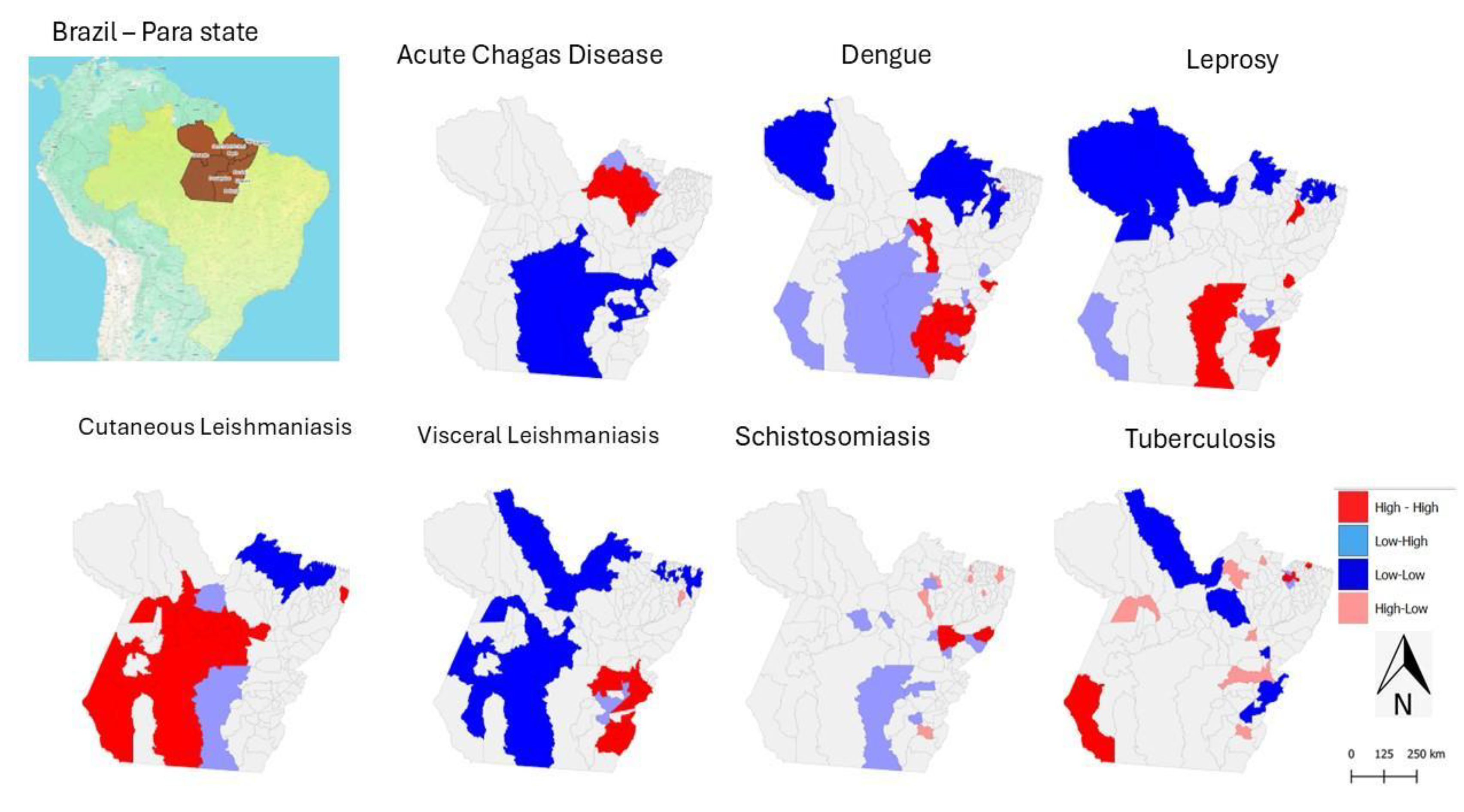

Through geospatial analysis, it was possible to identify areas with high incidence rates, as shown in the map (

Figure 2), highlighting both high and low incidence areas for each of the diseases. This spatial information supports the understanding of the factors influencing the spread of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs), such as the socio-economic, geographical, and environmental characteristics of different regions within the state of Pará.

The NTDs considered transitory include Dengue, ACD, Schistosomiasis, Leprosy, CL and VL. Previous studies that have conducted joint mapping of multiple diseases emphasise the importance of geographical space as a strategic unit for the development of public policies and decision-making in health, particularly in the context of multi-disease burdens [

4,

15,

16].

Using the analytical method applied to identify areas with high NTD incidence within the state of Pará, it was observed that many of these diseases exhibit distinct concentration patterns, which can guide further studies aimed at reducing their impact on the health of the population in Pará. Moreover, the spatial analysis of incidence rates over the years 2016 to 2020 revealed trends and temporal variations in the occurrence of NTDs.

Figure 2.

Spatial Distribution of Neglected Tropical Disease Incidence Rates in Pará, Brazil (2016–2022). Source: The authors – Adapted from the Notifiable Diseases Information System; Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

Figure 2.

Spatial Distribution of Neglected Tropical Disease Incidence Rates in Pará, Brazil (2016–2022). Source: The authors – Adapted from the Notifiable Diseases Information System; Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

Figure 2 shows that the incidence rates of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) in the state of Pará vary from one disease to another. Acute Chagas disease (ACD) has a higher concentration of cases in the Metropolitan Region of Belém. This indicates that the area has a significant number of recorded cases of this disease compared to other regions of the state.

Regarding dengue, higher concentrations of cases were observed in the western and southern regions of the state, suggesting that these areas present environmental and urban conditions conducive to the proliferation of the

Aedes aegypti vector. The high incidence may be associated with unplanned urbanisation, poor sanitation, and high population density in regional urban centres. Other studies highlighted that dengue in Pará peaks during the rainy season and climate-sensitive transmission demands targeted interventions in high-risk municipalities[

17]. Also, the disease epidemics in Brazil follow seasonal traveling waves, typically starting in northwestern states like Acre and Rondônia, then moving eastward to coastal and northeastern regions[

18].

Acute Chagas disease (ACD) stood out in High-High clusters in the Metropolitan Region of Belém and in southeastern Pará, respectively. Other study, when analyzing 696 cases of ACD from 2007 to 2015 in Belém, Abaetetuba and Breves, found that Belém alone accounted for 40.66% of reported cases, suggesting a shift from traditional rural transmission to urban outbreaks, likely driven by oral transmission, which accounted for 82.33% of cases[

19].

For schistosomiasis, cases are mainly concentrated in the southern and southeastern municipalities of Pará—regions characterised by riverside areas and poor sanitation conditions. The presence of contaminated water bodies and the population’s frequent exposure to these environments favour the maintenance of the disease’s transmission cycle [

20]. In this study, although detailed schistosomiasis data were less prominent in the sources, southeastern Pará is known for persistent endemic transmission, especially in rural and peri-urban communities with poor sanitation. In schistosomiasis cases, one remarkable characteristic of Pará state is that is not as prominent as the Northeast and Southeast of Brazil, indicating localized outbreaks or probable underreported endemicity[

21].

Tuberculosis (TB), on the other hand, has the city of Belém as its main focus, showing the highest incidence rates. This pattern may be related to high population density, social vulnerability, and the concentration of at-risk populations, such as residents of peripheral areas and people deprived of liberty. It may also reflect a higher rate of case reporting compared to other municipalities in the state. TB remains a major public health challenge in Pará, showing regional disparities require tailored interventions and strengthening local health systems and addressing socioeconomic inequalitiesmesore[

22]. In Tucurui area, a study highlighted that young, low-educated males are most affected and pulmonary TB was predominantly reported[

23].

Although cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) have been recorded in various regions of the state, the highest concentration was identified in the Lower Amazon region. This area, with vast forest zones and extractive activities, facilitates human contact with disease vectors, especially in rural and riverside communities[

24]. In Brazil, ACL incidence varies significantly across space and time, influenced by environmental conditions and rural settings contribute to this variability[

25].

Regarding leprosy, although it does not present the highest absolute number of cases, it is distributed across many municipalities, with Altamira standing out. This indicates a wide territorial dispersion of the disease, even with moderate incidence, which reinforces the need for active surveillance and early diagnosis strategies. This study found the Belém Metropolitan Area emerging as the most prominent transmission zone, with statistically significant clusters, highlighting the need for targeted surveillance and intervention strategies in urban centers (

Figure 2). Other study between 2019 and 2023 showed that Pará reported 12,231 leprosy cases, with 2019 having the highest count (3,554). Marituba, with a specialized treatment center, accounted for 13.4% of cases, followed by Belem and Parauapebas [

26].

The highest incidences of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) were recorded in the region known as South and Southeast Pará—areas that historically present favourable conditions for disease transmission, such as the presence of vectors, animal reservoirs, and social vulnerabilities that hinder access to healthcare services and vector control. In the case of VL in the Amazonian cities, the presence of open peridomestic yards increases the contact vector-host and these behaviors, especially with dogs contributed to the spread of

Leishmania chagasi[

27]. Understanding sandfly communication helps explain spatial patterns of infection and can inform vector control strategies.

It is worth noting that the southeastern region of the state of Pará stands out as an area with a high epidemiological burden for four major Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs): dengue, schistosomiasis, VL, and leprosy (see

Figure 2). This pattern of concentration may be attributed to a combination of environmental, socioeconomic, and structural factors.

The Marajó region presented a very specific pattern of ACD (acute Chagas disease) incidence throughout the study period. This can be explained by the strong association with oral transmission of the etiological agent (

Trypanosoma cruzi), particularly through the consumption of contaminated food such as açaí, as this region is a major producer. Additionally, Marajó has geographical and socioeconomic characteristics conducive to the spread of the disease, such as relative isolation, low sanitation coverage, and challenges in sanitary inspection[

28].

Dengue and visceral leishmaniasis (VL) showed greater territorial spread compared to other diseases, affecting a wide range of regions across the state. The former is classically associated with unplanned urbanisation, which facilitates the proliferation of

Aedes aegypti; deficiencies in basic sanitation; and high population mobility, which reintroduces susceptible individuals to new serotypes[

12]. The latter has a different profile, linked to deforestation and environmental degradation, agricultural expansion and mining, and recent spatial transformations in land use, which ultimately promote contact between humans, sandflies, and wild and/or domestic reservoir [

29].

Dengue and CL had the highest number of municipalities classified as High-High, indicating strong spatial concentration. CL also had the highest number of municipalities in Low-Low, suggesting large areas with low incidence. Leprosy and tuberculosis showed more distributed patterns, with presence across multiple types of clusters.

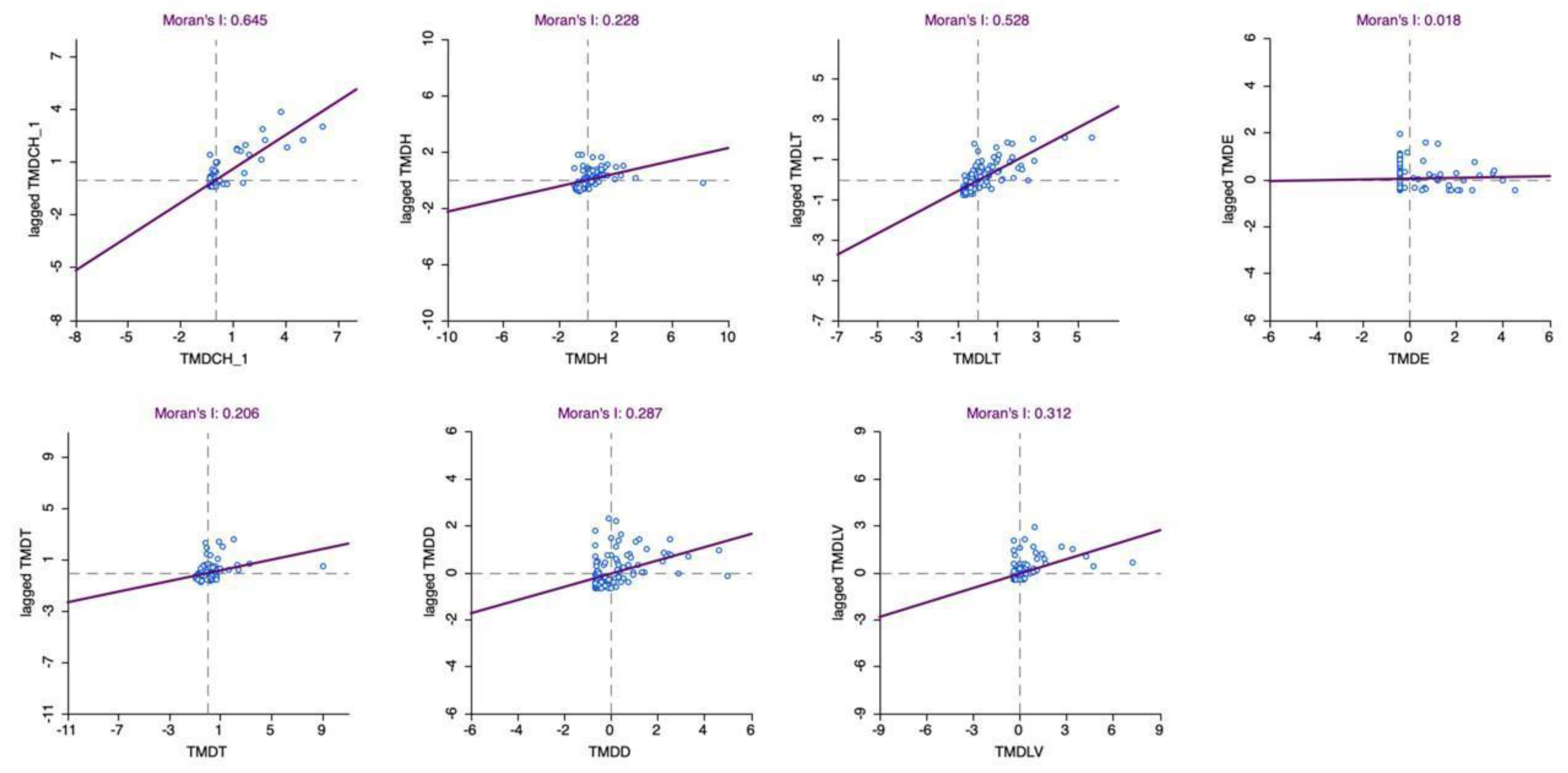

The analysis of statistical significance in the spatial distribution using the Moran’s I LISA index, applied to the average incidence of NTDs in the state of Pará between 2016 and 2022, enabled the identification of statistically significant spatial autocorrelation patterns (

Table 1). Through the detection of local clusters, it was possible to identify areas with high concentrations of cases (High-High), as well as regions with low incidence (Low-Low), revealing critical and priority zones for public health intervention.

When analysing the map (

Figure 3) showing the significance level of the Moran’s I LISA distribution, it is possible to observe areas where the incidence of NTDs presents either positive or negative spatial significance. Darker areas on the map indicate regions of positive significance, that is, where high incidence rates occur in neighbouring regions. Conversely, lighter areas represent regions of negative significance, indicating a dispersion of NTD cases—areas of low incidence located near those with high incidence.

Figure 3.

Spatial Distribution of Moran’s I LISA Significance Levels for the Average Incidence of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Pará, Brazil (2016–2022). Source: Notifiable Diseases Information System; Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Legend: The maps represent statistical significance based on the incidence rates of acute Chagas disease, dengue, leprosy, cutaneous leishmaniasis, visceral leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, and tuberculosis. The areas were classified into three categories: “Not significant”, “Low significance”, and “High significance”, according to the green colour scale. All data were considered at a significant level of p = 0.05.

Figure 3.

Spatial Distribution of Moran’s I LISA Significance Levels for the Average Incidence of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Pará, Brazil (2016–2022). Source: Notifiable Diseases Information System; Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Legend: The maps represent statistical significance based on the incidence rates of acute Chagas disease, dengue, leprosy, cutaneous leishmaniasis, visceral leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, and tuberculosis. The areas were classified into three categories: “Not significant”, “Low significance”, and “High significance”, according to the green colour scale. All data were considered at a significant level of p = 0.05.

Therefore, this distribution highlights the regions in the state of Pará where the incidence of NTDs shows a significant pattern of spatial organisation. These areas may indicate the presence of common risk factors or environmental characteristics that favour the persistence of these diseases. It is important to emphasise that the interpretation of results from this method should consider other factors, such as demographic characteristics, socioeconomic conditions, the presence of vectors, and public health policies. These additional elements can help in understanding the observed spatial patterns and in guiding strategies for the prevention and control of NTDs in Pará.

Through geospatial analysis, it was possible to identify areas with high incidence rates for different NTDs, as illustrated in the maps (

Figure 2). For example, dengue showed a high concentration pattern (High-High cluster) in 12 municipalities in southeastern Pará, while cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) had a wide dispersion, with 13 municipalities of high local incidence mainly located in the Lower Amazon region.

In contrast, leprosy and tuberculosis displayed distinct patterns: leprosy was concentrated in 7 municipalities in the southeast, while tuberculosis had higher incidence in the Metropolitan Region of Belém, with 8 municipalities classified as High-High. Acute Chagas disease and schistosomiasis showed more localised patterns, with emphasis on the Metropolitan Region of Belém and the southeast of the state, respectively.

When jointly analysing the maps in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, it becomes evident that some diseases, such as dengue and CL, have a greater capacity for territorial spread, while others, such as ACD, tend to occur in more restricted clusters. These spatial insights are essential for understanding the factors influencing the spread of NTDs, such as the socioeconomic, geographic, and environmental characteristics of different regions in Pará. Moreover, they enable the identification of priority areas for intervention, contributing to the planning of more effective surveillance and control actions.

Figure 4: Maps of the state of Pará showing the spatial clustering of acute Chagas disease, dengue, leprosy, cutaneous leishmaniasis, visceral leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, and tuberculosis, measured by the categories High-High, representing neighbourhoods with high values (Hot Spot); Low-Low, representing neighbourhoods with low values (Cold Spot). Additionally, High-Low indicates a hot spot surrounded by low values, and Low-High represents a cold spot surrounded by high values. Source: The authors – Adapted from the Notifiable Diseases Information System; Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

Figure 4.

Municipal-level Spatial Clustering of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Pará, Brazil, Based on Local Indicators of Spatial Association (Anselin Local Moran’s I), 2016–2022.

Figure 4.

Municipal-level Spatial Clustering of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Pará, Brazil, Based on Local Indicators of Spatial Association (Anselin Local Moran’s I), 2016–2022.

The maps in

Figure 4 provide strategic information for identifying priority areas for intervention, as they show a high concentration of multiple diseases (High-High) or the simultaneous presence of diseases in different critical clusters.

In this context, southeastern Pará is a priority region due to the high incidence of dengue, visceral leishmaniasis (VL), leprosy, acute Chagas disease (ACD), and schistosomiasis. Municipalities such as Redenção, Marabá, Xinguara, Parauapebas, and Rio Maria appear in multiple significant clusters (p < 0.01 or p < 0.001) (

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Scatterplot of Neglected Tropical Diseases Incidence in Pará, Brazil (2016–2022). Source: The authors – Adapted from the Notifiable Diseases Information System; Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

Figure 5.

Scatterplot of Neglected Tropical Diseases Incidence in Pará, Brazil (2016–2022). Source: The authors – Adapted from the Notifiable Diseases Information System; Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.