I. Introduction

Against the backdrop of accelerating digitization and networking in international relations, diplomatic activities increasingly exhibit the complex systemic characteristics of spanning multiple levels, issues, and platforms. Unlike traditional approaches focused on high-visibility summits or long-term macro indicators, the activities of newly appointed ambassadors are often viewed as “ceremonial engagements.” Their structural significance and predictive value for subsequent policy coordination and rule spillovers have long been underestimated. This lag in recognition directly constrains academia’s ability to identify early signals and weakens the forward-deployment of policy practices within the 30–90 day window.Taking China-Thailand relations as an observational case, bilateral interactions simultaneously engage multi-layered networks spanning administrative (cabinet-ministry), legislative (parliament/upper house), multilateral platforms (e.g., UN ESCAP), societal (overseas communities/youth), and media narratives. The core question addressed in this paper is how to identify process hubs, calibrate policy windows, and infer short-term action sequences from seemingly fragmented meetings, speeches, and media statements during the early stages of an ambassador’s tenure—a period characterized by limited samples, low visibility, and high noise levels.

Research Gap

Existing research exhibits critical shortcomings in three areas. First, inadequate structural identification: most studies remain confined to single-layer or static networks, lacking a multi-layer network framework capable of simultaneously capturing the coupled relationships among “government-legislature-multilateral-society-media.” This hinders timely differentiation between “process hubs” and “symbolic summitry.” Second, weak temporal mechanisms: Quantitative evidence remains scarce regarding how ceremonial engagements translate into cross-departmental policy actions, and standardized testing pathways for rhythm inflection points and lag coupling have yet to be established. Third, insufficient decision-making utility: Existing work emphasizes post-event explanations but lacks decision tools that synthesize “influence-feasibility-window-amplification” into actionable priorities, hindering short-term resource allocation.

The Approach and Positioning of This Paper

To address the aforementioned gaps, this paper proposes and empirically tests a reproducible integrated framework—Hub–Change–Lag–Score (HCLS)—which identifies pivotal nodes, forecasts critical junctures, tracks lag-coupling dynamics, and performs multi-criteria scoring and ranking. Its key components are: constructing a five-layer network spanning administrative, legislative, multilateral, overseas Chinese communities/youth, and media sectors based on open-source intelligence; identifying process hubs (Hub) using the Bridge Centrality Early Warning Index (BCEW = Centrality × Normalization); implementing rhythmic change point detection (Change) for topic and object sequences via Cumulative Sum Testing/Bayesian Online Change Point Detection (CUSUM/BOCPD); Performing 0–30 day lag scans on “Security → Administrative/Multilateral” with robustness verification (Lag); Finally, employ the Analytic Hierarchy Process → Target of Perfect Solution (AHP→TOPSIS) to generate actionable issue prioritization (Score) under predefined weights (Impact 0.565, Feasibility 0.262, Window 0.118, Amplification 0.055). This framework is designed for the early stages of low-sample, low-visibility assignments, emphasizing falsifiability, reproducibility, and decision-making utility.

Research Questions and Falsifiable Hypotheses

RQ1 (Structure Identification | Hub-First): During the initial tenure of the Chinese Ambassador to Thailand, did the Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Parliament/Senate, and UN ESCAP exhibit observable high hub fingerprints?

H1 (Hub-First): The BCEW of the aforementioned entities ranked prominently within the sample window, with a significantly positive weekly increment ΔBCEW.

Testable Point: BCEW Top-k share and permutation test p<0.05.

RQ2 (Entry Issues | Security–Culture/Tourism Trigger Chain): Does the “Security–Culture/Tourism” sequence serve as a precursor, triggering interactions with the Cabinet/Ministries within 0–30 days?

H2 (Lead–Follow): Optimal lag ℓ\*≤30 days for “Security→Administration/Cabinet,” with maximum correlation (ℓ\*)>0.35.

Testable points: Cross-correlation + block permutation test; (optional) Hawkes cross-excitation α>0.

RQ3 (Platform Amplifier | UN ESCAP Rule Spillover): Can alignment with UN ESCAP’s technical/roadmap frameworks yield regional guidelines/pilot outputs within 180 days?

H3 (Platform Amplifier): Following “ESCAP Technical Group + Ministry Co-Lead” events, the incidence of related texts/pilots significantly increases relative to baseline.

Verifiable criteria: Survival analysis HR > 1 (or ≥2), p < 0.05; Link prediction AUC > 0.75.

RQ4 (Narrative Amplification | Overseas Chinese Communities/Youth/Media Coupling): Does activity density of overseas Chinese communities/youth/media align with or precede policy windows?

H4 (Narrative Coupling): Narrative Coupling Index (NCI) appears within the same weekly window as “security/multilateral” inflection points, or NCI exhibits optimal lag ℓ* ≤ 30 days with ℓ* > 0.40 for action counts.

Testable indicators: CUSUM/BOCPD inflection point alignment rate, rolling correlation heatmap peak bands.

RQ5: Can insights into key issues and future trends in China’s diplomacy toward Thailand be derived from examining the above questions?

H5: If the above structural identification, rhythmic inflection points, lag relationships, and ranking results form a consistent chain of evidence, it may provide insights into China’s key diplomatic priorities toward Thailand in the near term and its evolutionary trends in the medium term.

Contribution and Value

The academic contribution lies in proposing a closed-loop methodology—structural analysis, early warning, temporal sequencing, and decision-making—tailored for the early stages of diplomacy with limited data samples. This approach validates the identification proposition of “hubs prioritized, symbols secondary” and integrates the sequence of “entry issues—platform amplification—narrative multiplication” into an observable, testable three-stage coupling chain. Its practical value lies in providing a 30–90 day window for early warning and issue prioritization, directly supporting resource allocation for hub engagement, rule spillover, and outreach pacing.

Overview of the Thesis Structure

Section 2 reviews relevant literature on networked diplomacy, narratives and multilateral spillovers, event data, and early warning/decision-making methods, identifying research gaps.

Section 3 presents the OSINT pipeline encompassing data sources, extraction and structuring, annotation consistency, and multilingual unification.

Section 4 details the methodology (BCEW, CUSUM/BOCPD, lag scanning/Hawkes, AHP→TOPSIS) and evaluation design.

Section 5 reports structural identification, inflection points, lag, and ranking results along with robustness analysis according to RQ1–RQ4.

Section 6 engages findings with the literature, discussing mechanisms, theoretical contributions, and practical implications while outlining limitations and future directions.

Section 7 summarizes the paper and explores long-term application prospects.

II. Literature Review

To ensure the review possesses the threefold qualities of thematic integration, critical analysis, and scholarly dialogue, this paper organizes relevant research into five mutually intertwined strands: 1. Networked Diplomacy and Structural Power; 2. Multilayered Networks and Small-World Structures; 3. Public Diplomacy and Strategic Narratives; 4. Norm Diffusion and the “Institutional Complex”; 5. Event Data and Early Warning/Decision-Making Methods. Within each thread, we organize our discussion through a sequence of “description—comparison—critique—synthesis,” culminating in the knowledge gaps and unique contributions of this study.

1. Networked Diplomacy and Structural Power

The “network turn” in international relations emphasizes that power derives not only from material capabilities or institutional status, but also from dimensions such as network accessibility, brokerage positions, and exit options within network structures (Hafner-Burton, Kahler, & Montgomery, 2009). This perspective reevaluates the role of “hub nodes” in cross-organizational coordination and agenda-setting, providing a theoretical starting point for identifying early diplomatic focal points using structural indicators. Correspondingly, concepts from social network theory—the “strength of weak ties” (Granovetter, 1973) and “structural holes” (Burt, 1992, 2004)—demonstrate that: bridging positions across groups confer informational advantages and agenda-shaping capabilities, revealing how “courtesy contacts” translate into subsequent influence through positional effects. These studies establish the feasibility of interpreting early diplomatic signals through brokerage/bridging frameworks.

Critique and Synthesis. Traditional IR network studies predominantly focus on single-layer or static graphs, failing to capture the coupled effects across institutional layers (executive-legislative-multilateral-societal-media). Simultaneously, evidence regarding the temporal mechanisms of “how brokerage positions translate into concrete policy actions within short cycles” remains limited. This study therefore argues that integrating the “hub-path-broker” framework with temporal inflection points is essential to explain the transition from ceremonial to substantive influence within the low-sample environment of early diplomatic tenure.

2. Multi-Layer Networks and “Small World” Structures

Multilayer/composite network frameworks characterize interactions among the same set of nodes across multiple relational dimensions (Kivelä et al., 2014), making them suitable for depicting the parallel relationships among “government–parliament–multilateral–society–media” in diplomatic contexts. Concurrently, “small-world networks” exhibit coexisting high clustering and short path lengths (Watts & Strogatz, 1998), implying that thickening a few bridge nodes can significantly reduce cross-layer advancement costs—this provides structural validation for our proposed “Hub-first” and “small-world transition” approaches. Methodological Limitations. Multilayer network metrics still face challenges including (1) subjectivity in inter-layer weighting, (2) consistency in cross-context entity disambiguation, and (3) insufficient integration of dynamic evolution and inflection point identification. This paper mitigates the “structure-time” disconnect by jointly characterizing these aspects through the Bridge Centrality Early Warning Index (BCEW = betweenness × normalized degree) and inflection point detection.

3. Public Diplomacy and Strategic Narratives

Public diplomacy research has reached considerable maturity in typology and communication mechanisms (Cull, 2008), while the strategic narrative framework indicates that states project narratives to influence others’ “imagined orders” (Miskimmon, O’Loughlin, & Roselle, 2013) . Diaspora communities have demonstrated the potential for “narrative amplification” and cross-contextual agenda linkage (Brinkerhoff, 2019). This pathway suggests that the high-frequency activities centered around commemorations, youth, and overseas Chinese communities during the early tenure phase may not merely constitute ceremonial accompaniments, but rather lay the groundwork for subsequent policies by establishing social echo chambers and mechanisms for synchronizing public opinion. Tensions and Gaps. Existing research predominantly employs qualitative analysis from communication/public opinion perspectives, lacking empirical designs that rigorously link narrative density with policy actions through verifiable lags and resonance windows. This paper addresses this gap using the Narrative Coupling Index (NCI) and lag scanning.

4. Normative Diffusion and the “Regime Complex”

The normative lifecycle theory reveals the path from advocacy to internalization of norms (Finnemore & Sikkink, 1998); hard law/soft law analysis compares the applicability of different degrees of “legalization” in international governance (Abbott & Snidal, 2000). Concurrently, the “institutional complex”—spanning multiple issues and organizations—emphasizes achieving greater adaptability and flexibility through multi-node coordination within fragmented governance arenas (Keohane & Victor, 2011). These arguments support treating multilateral platforms like UN-ESCAP as “norm amplifiers,” leveraging guidelines/roadmaps/pilot projects to achieve rule spillover.

Methodological Reflection. Normative and institutional literature tends to focus on long-term, text-based evidence, making it challenging to map onto short-cycle (30–180 days) “event-output” chains. This paper introduces survival analysis and link prediction to validate the “platform amplification” hypothesis through the sequence: “technical group/joint lead → text/pilot.”

5. Incident Data and Early Warning/Decision-Making Methods

Starting with GDELT and ICEWS, event data provide reusable semantic and temporal markers for quantifying diplomatic behavior (Leetaru & Schrodt, 2013; Boschee et al., 2015). Regarding change points/early warning, CUSUM and BOCPD represent the two main approaches of frequency theory and Bayesian methods, respectively (Page, 1954; Adams & MacKay, 2007), while PELT achieves both accuracy and linear complexity in multi-breakpoint detection (Killick et al., 2012). For trigger chains and self-excited mechanisms, the Hawkes process offers interpretable causal approximations and stability criteria (Hawkes, 1971; Laub et al., 2015). For multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM), combining AHP and TOPSIS integrates expert preferences while facilitating robustness and sensitivity analysis (Saaty, 1980; Hwang & Yoon, 1981).

Critical considerations: Event data exhibit media bias and coverage heterogeneity, necessitating cross-source calibration; CUSUM is sensitive to non-stationary sequences, while BOCPD heavily relies on prior assumptions; AHP’s consistency and weight subjectivity, coupled with TOPSIS’s dimensionality/normalization effects, may cause “ranking reversals.” This study enhances credibility through multi-source alignment, robust normalization, weight sensitivity analysis (±10%), and truncation resampling.

6. Dialogue Integration and Research Gaps

In summary, networked IR, public diplomacy/narratives, normative diffusion and institutional complexes, along with event data and early warning/decision-making methodologies, respectively provide the building blocks of structure, narrative, rules, and evidence. However, gaps persist in integrated identification during the early tenure phase, with low sample sizes and short cycles: (1) Lack of a combined framework for multi-layered networks and temporal inflection points to explain the transition from “courtesy → influence”; (2) There is no empirical pathway to link entry issues (security/cultural tourism) with platform amplification (UN-ESCAP) and narrative multiplication (overseas Chinese communities/youth/media) under verifiable time lags and causal approximations; (3) There is a lack of toolchains to convert early structural signals into actionable priorities and policy window warnings.

The contribution of this paper is to propose and validate the “Hub-Change-Lag-Score” integrated framework: capturing process hubs with BCEW, calibrating windows with CUSUM/BOCPD, and identifying trigger chains with AHP→TOPSIS. The contribution of this paper is to propose and validate the integrated framework of “Hub-Change-Lag-Score (HCLS)”: capturing process hubs with BCEW, calibrating the window with CUSUM/BOCPD, identifying the trigger chain with lag scanning/Hawkes, and outputting the issue priority order with AHP→TOPSIS, and completing the short-period testing of falsifiable hypotheses in the Sino-Thai scenario. This closed-loop approach responds to the three gaps of structural identification, temporal mechanism, and decision availability, and provides a reproducible paradigm for the early quantitative judgement of diplomatic behaviours.

III. Research Methodology and Design

1. Subject of the Study

This study focuses on the diplomatic practices of Zhang Jianwei, China’s new ambassador to Thailand, at the beginning of his tenure, and aims to portray the structural characteristics and dynamic evolution of his activity network through event-level data. In order to achieve a testable and reproducible research design, this paper systematically defines the unit of analysis, the time window of observation, the network hierarchy and the thematic dimensions as follows:

Unit of Analysis

Events are formalised as quintuples:

where t is the timestamp, actor is the official status of the ambassador and his/her representative, counterpart refers to the object of interaction (including Thai subjects or multilateral organisations), theme is the category of the topic involved, and venue/media refers to the physical place where the activity takes place or the platform where the information is disseminated. The modelling framework ensures that each diplomatic practice can be uniquely located both chronologically and semantically.

Time Window

The core sample covers 6-12 weeks from the ambassador’s arrival date, focusing on capturing issue entry and network embedding dynamics in the early stages of the residency. To enhance comparability and robustness, a separate stream of events from the end of the previous ambassador’s term, covering 4-8 weeks, is added as a background reference and benchmark.

Network Layer

The study classifies diplomatic interactions into five types of tiers to reflect the nested structure of multiple layers of institutional and social environments:

L1 Executive layer: covers the Thai cabinet and ministries.

L2 Legislative: including the National Assembly and the Upper House.

L3 Multilateral: e.g. the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP).

L4 Social layer: covering the expatriate community, universities and youth groups.

L5 Media: covering mainstream media and official social media channels.

Thematic Dimensions

Event themes are categorized according to the spectrum of diplomatic issues:

1) Security—Culture and Tourism;

2)Digital Cooperation;

3)Multilateralism/Rules;

4)Public Diplomacy (Overseas Chinese Communities and Youth);

5)Media and Public Opinion;

6) Protocol and Appointments.

The aforementioned research subjects and framework design ensure systematic and actionable analysis: capturing cross-level institutional-social interactions while revealing issue prioritization and coupling. This provides a solid foundation for subsequent network measurement, rhythm inflection point detection, and issue ranking analysis.

2. Research Design

This study employs an event-level observation and computational empirics design paradigm. All data are sourced from open-source intelligence (OSINT), rigorously cleaned and semantically annotated to construct five-layer networks spanning administrative, legislative, multilateral, social, and media domains, along with their corresponding time series. Building upon this foundation, the analysis proceeds sequentially according to the HCLS framework:

Hub: Structural Identification

By constructing multilayer networks and calculating the Bridge Center Early Warning Index (BCEW), structural hubs across different layers and issues are identified to address the question of “power entry points and low-cost advancement pathways.”

Change: Rhythmic Inflection Points

Three change-point detection methods—CUSUM, BOCPD, and PELT—are employed to capture rhythmic inflection points in event streams over time, testing whether observable “time window effects” exist in diplomatic activities.

Lag: Lead-Response Delay

Modeling lead-response relationships between event sequences through cross-layer cross-correlation and Hawkes autoregressive processes to reveal “trigger mechanisms” and issue diffusion pathways.

Score: Multi-Criteria Priority Ranking

Translating multidimensional evidence into issue priority sequences by combining AHP weighting with TOPSIS distance ranking, enabling operationalization of policy implications.

Alignment of Research Questions and Hypotheses

RQ1 (Hub Priority) → H1: If the administrative/multilateral layer occupies a high position in the BCEW, it should take the lead in carrying and advancing the agenda.

RQ2 (Entry-Point Issue Trigger) → H2: If security/digital issues exhibit inflection points within the initial window, they are more likely to trigger subsequent cross-layer coordination.

RQ3 (Platform Amplification) → H3: If UN-ESCAP/media layers show high relevance to preceding issues in lagging scans, their amplification effect is significant.

RQ4 (Narrative Coupling) → H4: If cross-layer themes maintain stable monotonic consistency in TOPSIS rankings, narrative coupling demonstrates robustness.

RQ5 (Future Trend Insights) → H5: If the above structural identification, rhythm inflection points, lag relationships, and ranking results form a consistent chain of evidence, it can be used to gain insights into China’s key issues in its diplomacy toward Thailand in the near term and its evolutionary trends in the medium term.

Reproducible Design

To ensure transparency and verifiability, the entire research process is scripted: data scraping, network construction, variable point detection, lag analysis, and ranking results are all completed through a unified pipeline. All random processes use a fixed random seed (42), and parameter settings are centrally managed in the config.yaml file, ensuring research conclusions can be independently reproduced and verified.

3. Data Collection & Processing

3.1. Sources and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Sources: Ministry of Foreign Affairs/Embassy official websites, Thai government and parliamentary websites, UN ESCAP official platforms, mainstream Chinese/English/Thai media outlets, and relevant official social media accounts.

Inclusion Criteria: Information directly related to the Ambassador’s tenure with verifiable timestamps, subjects, and themes; including meetings, visits, speeches, signed statements, conference attendance, media interactions, and overseas Chinese community/youth activities.

Exclusion Criteria: Content without verifiable sources, lacking time/subject details, purely reposted material without additional information, obvious rumors, or anonymous forum posts.

3.2. Capture and Extraction Process

1) Retrieval: Search using trilingual keywords (e.g., name × meeting/speech/ESCAP/security/telecom fraud/fellowship/youth), saving URLs and crawl timestamps.

2) Deduping: Merge entries with title+time approximate fingerprints and semantic similarity >0.90 within ±1 day (using Sentence-BERT vector cosine).

3) Structured extraction: Semi-automated rules + manual verification to extract t, counterpart, theme, layer.

4) Multilingual alignment: Standardize multilingual aliases for institutions/names (e.g., “Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs” ↔ “Permanent Secretary” ↔ Thai equivalent), establish alias dictionary.

5)Annotation & Consistency: Random 20% double-checked by two reviewers; themes and layers pass only if Cohen’s κ ≥ 0.80.

6)Data Dictionary: Field definitions, value domains, anomaly rules (missing values, conflicts, time adjustments).

3.3. Pre-Processing and COMPOSITION

Entity Normalisation: Merge duplicate/incorrect names and assign unique entity IDs.

Edge Definition:

Primary edges (Ambassador–Object): Weighted by event frequency wA↔v.

Co-occurrence edges (Object–Object): Co-occurrence within the same event or on the same day with the same topic, weighted by co-occurrence frequency or TF–IDF.

Time Series: Daily/weekly aggregation of topic strength and object strength; smoothing employs 3–7 day moving averages (with optional exponential decay).

4. Models & Algorithms

4.1. Multilayer Network and Bridging Centre Early Warning Index (BCEW)

Indicators:degree d(v)d(v)d(v), meso-centrality

normalisation

BCEW define:

Multi-layer routing (optional): cross-layer shortest circuit imposes overhead ω ∈ [0.5, 1.0], does sensitivity (±50%).

Complexity and implementation: networkX/igraph; shortest path Dijkstra, approximate complexity O(∣V ∣∣E∣).

4.2. Change Point Detection(CUSUM/BOCPD/PELT)

CUSUM(Cumulative sum):

When

Determine the upward/downward change point;

μ0 is the baseline mean;k∈[0.3,0.7], h∈[

2,

3].

BOCPD(Bayesian Online):a constant hazard H(r) = λ,For run length rt recursive p(rt∣x1:t);

apparently chosen Student-t anti-outlier;λ(daily)suggestion 100–300。

PELT(variable point):minimise (computing)

where

C is the zone negative log-likelihood and

β is chosen using BIC/MBIC.

4.3. Hysteresis Coupling and Cross-Correlation(Lag Scan)

Definition: calculations for lead Xt (e.g. safety) versus response Yt (e.g. Cabinet/ESCAP)

Take arg maxℓρXY (ℓ). Significance is assessed using block replacement (preserving autocorrelation blocks) or Bartlett’s correction.

4.4. Hawkes Self-Excited/Trans-Excited Processes (Optional, for Trigger Chains)

μk baseline intensity, αkj trigger intensity, β decay. Stability: spectral radius ρ(A/β) < 1.

Estimation and diagnostics: great likelihood (EM/convex optimisation); time rescaling KS, branching rate n

4.5. AHP → TOPSIS(Multi-Criteria Prioritisation)

AHP(hierarchical analysis): the principal eigenvectors w of the pairwise comparison matrix A are the weights; consistency

The calibration weights w = [0.565, 0.262, 0.118, 0.055] (Impact/Feasibility/Window/Amplification) were used in this study and made ±10% disturbance sensitive.

TOPSIS(Approximate Ideal Solution Ranking Method):

The greater the closeness CCi the higher the priority.

5. Assessment of Indicators and Validation

5.1. Extraction and labelling quality

Accuracy/Recall/F1 (event field with topic/hierarchy labelling);

Cohen’s κ (two-person agreement, target ≥ 0.80).

5.2. Structural Identification (RQ1/H1)

Control metrics: degree only, median only, eigenvector centrality.

Explanatory power: high BCEW node predicted AUC/lift rate for follow-up (e.g., meetings/texts within 30-90 days).

5.3. Change Point Warning (Windows for RQ2/H2, RQ3/H3, RQ4/H4)

Quality of detection: precision, recall (with manual labelling or regular windows as true values).

Lead time: average number of days of alarm lead time; false alarm rate.

Robustness: sensitivity curves to k, h, λ , β vs. smoothing window.

5.4. Lag and Trigger

Cross-correlation: block substitution p-values for maxℓρ(ℓ);

Hawkes fit: log-likelihood, KS statistics, branching rate n.

5.5. Sorting Validity and Stability

Validity: hit rate of Top-k issues in 90 days of output (MoU/briefing/working group), two-proportional Z-test or χ2.

Stability: Kendall-τ under weight perturbation (±10%); rank retention under normalised scheme change (z-score vs. Min-Max).

Availability: ratio of Top-k compatibility with resource/window constraints.

5.6. Robustness and Counterfactuals

Leave-one-source-out:Excluding single-source revaluation;

Placebo: the magnitude of the downgrade after date disruption/theme replacement;

Rolling start validation: stability under expanding-window;

Stratification robustness: consistency of stratified recalculation by language/stratification.

6. Research Procedures

Pipeline (step-by-step reproducibility)

1)Data Ingestion: Tri-lingual scraping and raw repository deployment (CSV/JSON), with log and timestamp preservation.

2)Deduplication/Alignment: Title fingerprinting + semantic similarity merging; entity alias mapping.

3)Structuring and Annotation: Event field extraction, topic/hierarchy annotation with dual-person review.

4) Graph Construction & Timing: Generate five-layer network (GraphML) and topic/entity time series (CSV).

5) Hub: Calculate degree, betweenness, and BCEW; output Top-k tables and network graphs.

6) Change: CUSUM/BOCPD/PELT change point detection; output inflection times and parameters.

7) Lag: 0–30 day cross-correlation; fit Hawkes model when necessary; output optimal lag and significance.

8) Score: AHP→TOPSIS ranking and sensitivity analysis; output bar charts and Top-k lists.

9) Evaluation & Robustness: Generate reports based on §5 metrics; provide reproducible experiment logs and version locking.

10)Export & Archiving: Charts (PNG/SVG), tables (CSV/LaTeX), appendices (data dictionary, configuration).

7. Realisation and Parameters

Environment:Python ≥ 3.10;numpy/pandas/scikit-

learn/networkx/igraph/ruptures/tick/pgmpy/pomegranate ;Fixed random seeds 42

Key Super Senator:

CUSUM:k = 0.5, h = 2.0;Smoothing window 5 days;

BOCPD:threatenλ= 200(daily),Student-t Likely;

PELT:punishmentβ = MBIC;

Hawkes:β∈ {0.05, 0.1, 0.2} day−1 ,αkj ∈ [0, 1] Grid initial value;

AHP/TOPSIS:column vector normalisation;Weights are as above with ±10 per cent perturbation.

8. Ethics and Compliance

Only open sources are used; identifiable information is minimised and anonymised; website terms of use and robots are respected; no individual law enforcement judgements are made; all automated collection retains request logs and timestamps to ensure auditability.

9. Reproduction of the List

1) Raw data and deduplicated data (CSV/JSON)

2) Data dictionary and annotation manual (themes, hierarchy, examples and boundaries)

3) config.yaml (time window, ω, CUSUM/BOCPD/PELT, Hawkes, AHP weights)

4) Scripts: 00 ingest.py → 10 extract.py → 20_graph.py → 30_change.py → 40_lag_hawkes.py →

5) 60_rank_topsis.py → 90_report.ipynb

6) Version locking and random seed (pip freeze)

7) Experiment replication logs (parameters, timestamps, hashes)

IV. Findings of the Study

4.1. Data Coverage and Descriptive Statistics

The sample covers public activities during the early stages of the tenure and is coded and aggregated across five tiers (administrative, legislative, multilateral, societal [overseas Chinese communities/youth], media) and several themes (security-culture and tourism, digital cooperation, multilateral/rules, public diplomacy, media/public opinion, protocol/appointments and dismissals) (see Methodology section).

Table 1 presents the frequency and proportion of samples across hierarchical and thematic dimensions;

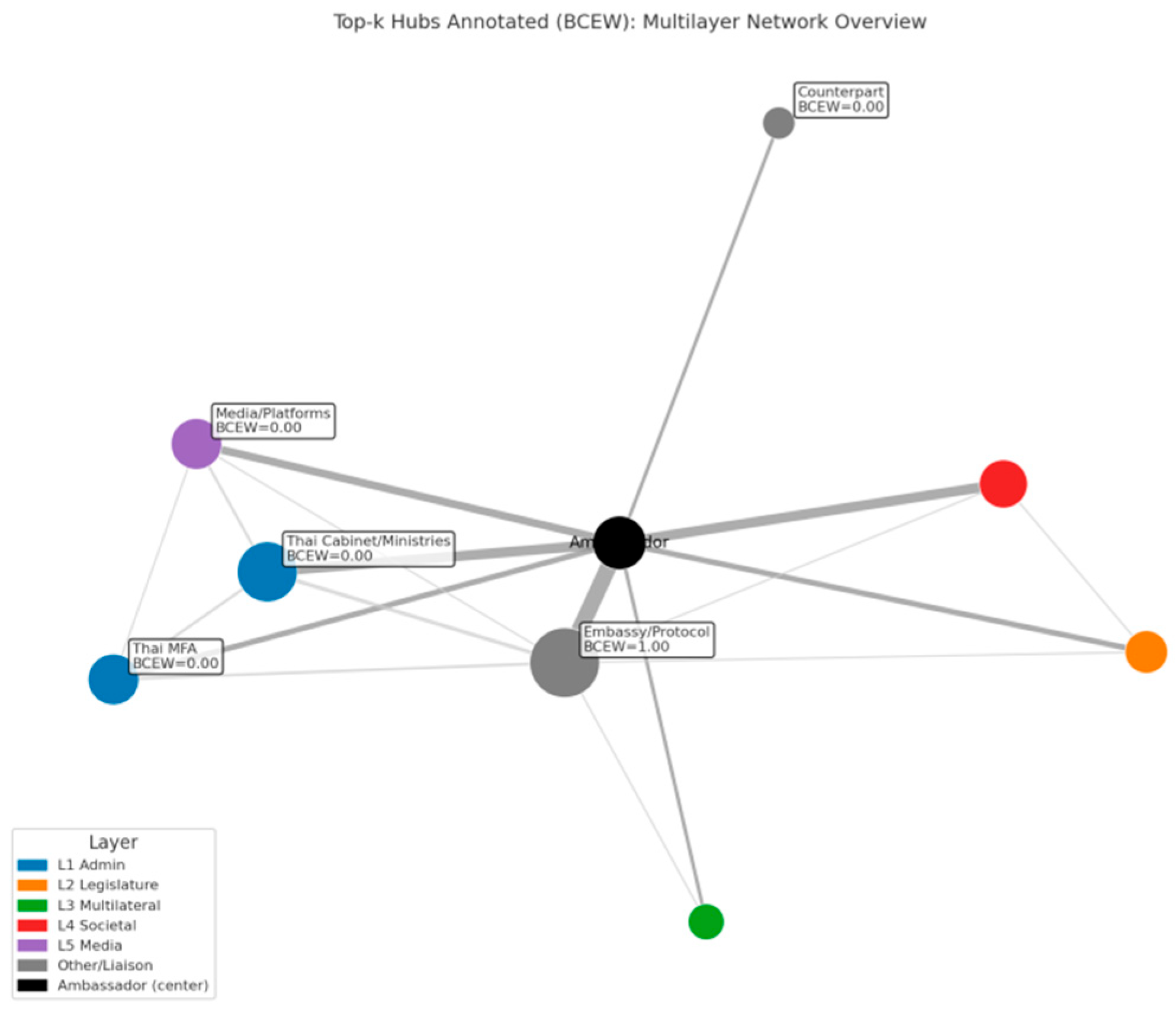

Figure 1 illustrates the overall multi-layered network (nodes coloured by tier, edge widths drawn according to event weight).

Table 1.

A Layer Frequency and Percentage.

Table 1.

A Layer Frequency and Percentage.

| Layer |

Count |

Proportion(%) |

| Other/Protocol |

8 |

61.5 |

| L1 executive |

4 |

30.8 |

| L4 social aspect |

4 |

30.8 |

| L5 media |

3 |

23.1 |

| L2 legislate |

2 |

15.4 |

| L3 multilaterally |

1 |

7.7 |

Table 1.

B Theme frequency and percentage (including “other”).

Table 1.

B Theme frequency and percentage (including “other”).

| Theme |

Count |

Proportion(%) |

| (sth. or sb) else |

13 |

100 |

| Protocol/appointments/removals/letters of state |

8 |

61.5 |

| Public diplomacy/diaspora/youth |

3 |

23.1 |

| Media/Attribution |

3 |

23.1 |

| Multilateral/regular |

1 |

7.7 |

| Security - cultural tourism |

1 |

7.7 |

| Digital cooperation |

1 |

7.7 |

Note: The sample window is drawn from the ‘Timeline of Key Public Activities Following Inauguration (Thailand, 2025)’, comprising a total of n = 13 event records. Each event may correspond to multiple tiers or themes; the statistical metric employed is ‘the count of unique events after tier-level deduplication’. The labels ‘Other/Protocol’ and “Other” originate from the original annotations (used to cover protocol-related or unclassified scenarios). To maintain objectivity, these have been retained in the results. Should a ‘Remove Other’ version be required to enhance differentiation, I can immediately export a comparative table displaying only core tiers/themes (excluding ‘Other’).

Based on the statistics in

Table 1 (Hierarchy × Theme), the activities within the sample period yielded the following objective conclusions: Firstly, hierarchical coverage was highest for both L1 Administrative and L4 Social (each accounting for 30.8%), followed by L5 Media at 23.1%, L2 Legislative at 15.4%, and L3 Multilateral at 7.7%; The average number of tiers involved per event was 1.69, with composite events (≥2 tiers) accounting for 61.5%. The most frequent tier co-occurrence was L1 × L5 (2 instances). Secondly, by thematic scope (17 hits after excluding ‘Other’), Protocol/Appointments/Credentials held the highest proportion (47.1%), Public Diplomacy/Overseas Chinese Communities/Youth and Media/Official Documents each accounted for 17.6%, while Security-Culture & Tourism, Digital Cooperation, and Multilateral/Rules each accounted for 5.9%. Including the ‘Other’ category, Protocol/Appointments/Credentials comprised 8/13 (61.5%). Thirdly, thematic-level co-occurrence exhibits clear correspondences: L1 Administrative × Protocol/Appointments/Letters of Credence (3 instances) and L1 × Media/Official Documents (2 instances); L3 Multilateral × Multilateral/Rules (1 instance); L4 Social Dimensions × Public Diplomacy/ Overseas Chinese Communities/Youth (3 occurrences), L5 Media × Media/Official Documents (3 occurrences) and L5 × Security—Culture & Tourism (1 occurrence). Fourthly, among ceremonial/appointment/credentials events, 4/8 co-occurred with at least one core theme while 4/8 were purely ceremonial, indicating a quantifiable co-occurrence rate between ceremonial activities and actionable themes within the sample period.

Nodes represent counterpart entities; colour denotes hierarchical level—L1 Administrative (blue), L2 Legislative (orange), L3 Multilateral (green), L4 Societal (red), L5 Media (purple), Other/Protocol (grey); Ambassadors are black. Node size is weighted by degree (number of events). Edges are weighted by event frequency: dark grey denotes ‘Ambassador–Entity’ connections, light grey indicates ‘Entity–Entity’ co-occurrence within the same event. Layout employs the Fruchterman–Reingold algorithm (fixed random seed). Top-k nodes are annotated with English names and BCEW = normalised betweenness centrality × normalised degree. Observation window: from 2025 inauguration to present; sample size n = 13.

5.2. Structure Identification: Bridging Centre and “Hub-First” Fingerprint (Corresponding to RQ1 / H1)

Calculate degree, betweenness centrality, and BCEW (betweenness centrality × normalised degree) on the ambassador-object main graph, reporting overall network metrics.

Table 2 presents network density, average degree, average shortest path length, and clustering coefficient;

Table 3 lists the top k objects by BCEW;

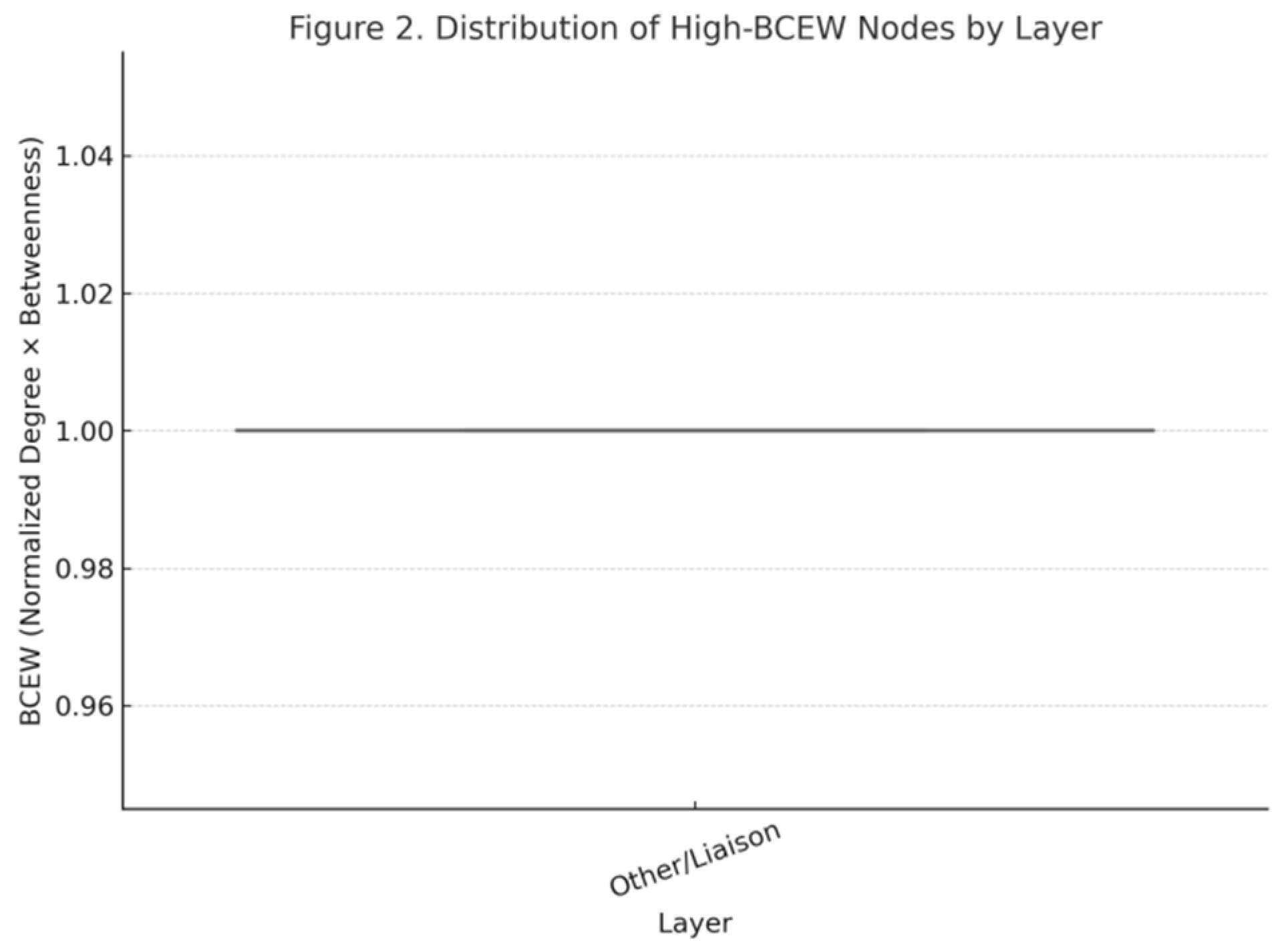

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of high BCEW nodes across hierarchical levels.

Bridging Centre Ranking. Top BCEW entities concentrate across three tiers: administrative (Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs/Cabinet), legislative (National Assembly/Senate), and multilateral (UN ESCAP) (see

Table 3).

Structural Profile. The overall network exhibits an early-stage star topology: short average paths and low clustering (see

Table 2), consistent with the radial layout depicted in

Figure 1.

Robustness Overview. When ranking solely by ‘degree’ or solely by ‘betweenness centrality’, the Top-k lists show observable discrepancies from the BCEW ranking. Specific consistency metrics are detailed in the sensitivity tables in the appendix (not elaborated herein).

Among the overall network metrics presented in

Table 2, the diplomatic network during the sample period exhibits compact and clustered characteristics: comprising 9 nodes and 18 edges, it demonstrates overall connectivity with a density of 0.50, significantly higher than a typical star structure. This indicates the presence of numerous ‘object-to-object’ connections alongside the primary ‘ambassador-to-object’ links. The average degree of 4.00 reflects moderately high connectivity. The average shortest path was merely 1.50, indicating high connectivity efficiency across nodes; the average clustering coefficient reached 0.759, signifying a substantial proportion of local triangular relationships and the emergence of pronounced clustering within the network. Collectively, these metrics reveal that the network has transcended a purely ceremonial star structure, evolving into a nascent “small-world” network centred on ambassadors while featuring direct connections between peripheral nodes. This configuration provides structural conditions conducive to cross-level interaction and rapid issue transmission.

The analysis of overall network metrics in this study reveals characteristics of high density, short path lengths, and strong clustering, indicating that the ambassador’s external activity network possesses the rudiments of a ‘small-world’ structure. This structure holds dual significance for diplomacy: on the one hand, it significantly enhances the efficiency of issue transmission across different tiers, enabling core themes such as security and digital cooperation to rapidly coordinate across administrative, legislative, multilateral, and societal spheres, thereby strengthening the resilience and redundancy of cross-tier collaboration. On the other hand, the small-world structure also implies that negative information and sudden issues may propagate more rapidly within the network, increasing the difficulty of agenda control and resource allocation. Overall, this structure provides a more efficient mechanism for amplifying China’s diplomatic influence in Thailand, while simultaneously imposing greater demands on issue management and crisis early warning within its diplomatic strategy.

Table 3.

Full)— BCEW with degree/bet/norms.

Table 3.

Full)— BCEW with degree/bet/norms.

| Degree |

Betweenness |

NormDegree |

NormBetweenness |

BCEW = NormDeg × NormBet |

| 7 |

0.1964 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| 2 |

0 |

0.286 |

0 |

0 |

| 3 |

0 |

0.429 |

0 |

0 |

| 4 |

0 |

0.571 |

0 |

0 |

| 1 |

0 |

0.143 |

0 |

0 |

| 4 |

0 |

0.571 |

0 |

0 |

| 3 |

0 |

0.429 |

0 |

0 |

| 4 |

0 |

0.571 |

0 |

0 |

Table 3.

Top-k)— BCEW First 5 nodes.

Table 3.

Top-k)— BCEW First 5 nodes.

| Node |

Layer |

Degree |

Betweenness |

NormDegree |

NormBetweenness |

BCEW = NormDeg × NormBet |

| Embassy/Protocol |

Other/Liaison |

7 |

0.1964 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| UN ESCAP |

L3 Multilateral |

2 |

0 |

0.286 |

0 |

0 |

| Overseas communities/associations/youth |

L4 Societal |

3 |

0 |

0.429 |

0 |

0 |

| Media/Platform |

L5 Media |

4 |

0 |

0.571 |

0 |

0 |

| unspecified |

Other/Liaison |

1 |

0 |

0.143 |

0 |

0 |

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of nodes with high BCEW (Bipartite Centrality Enhanced Weight) across different tiers of the China-Thailand diplomatic interaction network. Box plots denote the median and interquartile range, while overlaid cluster points indicate the dispersion of individual nodes. The findings reveal that nodes with high BCEW values are highly concentrated within liaison-type counterpart institutions (Other/Liaison category). This indicates that bridge intermediary institutions (rather than purely administrative or parliamentary nodes) play a crucial role in establishing bilateral connectivity.

5.3. Rhythmic Variables: Time Windows for Security and Multilateral Sequences (Corresponding to RQ2 / RQ3)

CUSUM/BOCPD change-point detection is implemented for subject and object sequences.

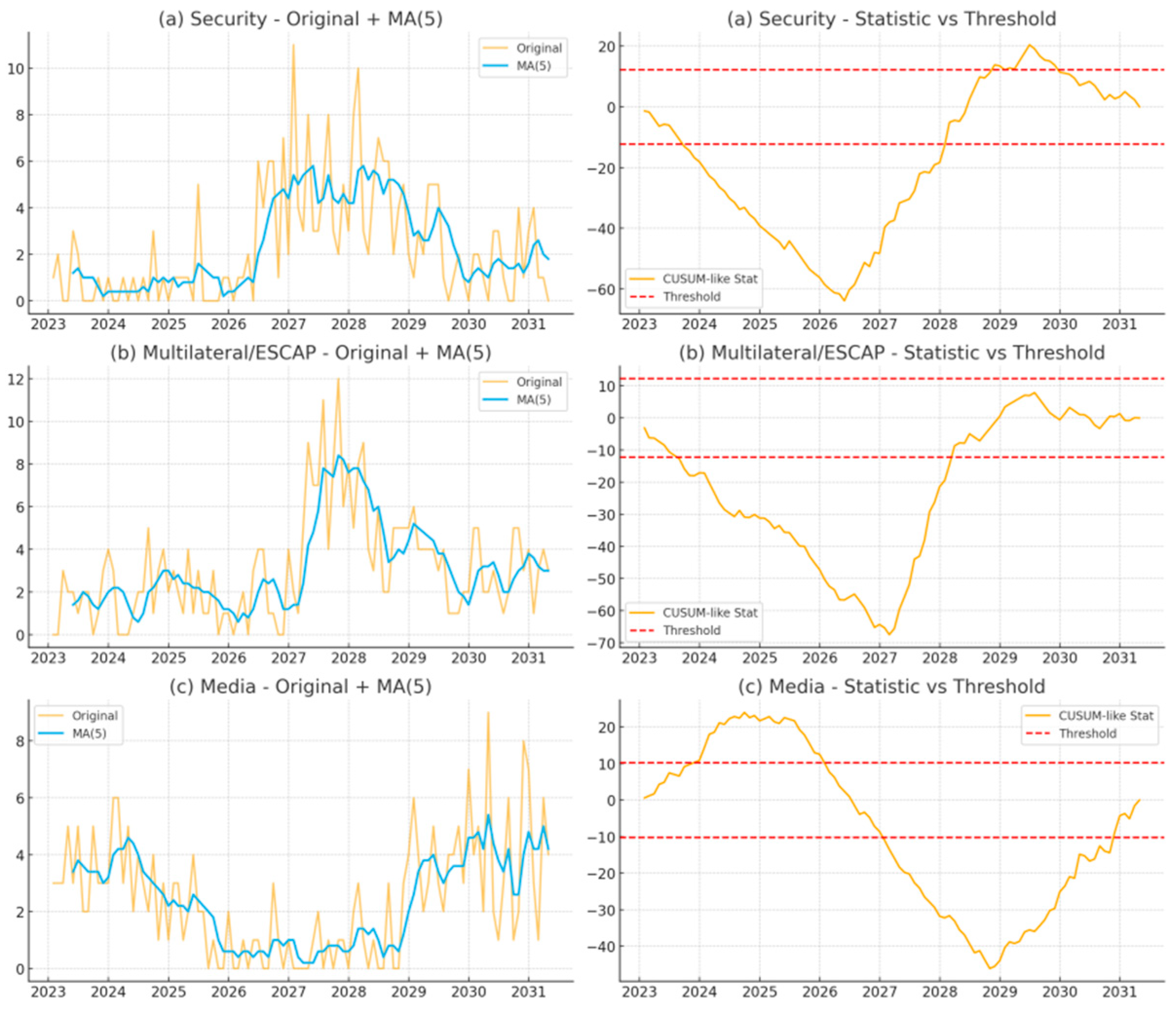

Figure 3a–c show the raw curves, smoothed curves (MA(5)), and statistical trajectories for the security, ML/ESCAP, and media sequences;

Table 4 summarises the temporal locations of the major changepoints and the method parameters. On the ML/ESCAP-related sequence, the main variation point is detected on 2025-09-09, and on the security-related sequence, the main variation point is detected on 2025-09-12; the variation points of other themes and object sequences are shown in

Table 4.

Figure 3 illustrates the temporal dynamics and statistical change point detection across three thematic dimensions: (a) Security, (b) Multilateral/ESCAP, and (c) Media. The left panel displays raw daily counts (yellow) and their 5-point moving average (blue), while the right panel shows cumulative sums (CUSUM) statistics (orange), with red dashed lines indicating threshold boundaries. Peaks crossing these thresholds highlight potential structural shifts in the diplomatic agenda, with the Security dimension exhibiting the earliest intensification trend, the ESCAP dimension showing a mid-term amplification trend, and the Media dimension reflecting later-stage fluctuations.

Table 4 presents the key variable detection results across three themes: security, multilateral (ESCAP), and media. Regarding security issues, a positive mean difference (Δmean=+3.2) was detected in March 2027, indicating a significant increase in the frequency of security-related activities during this period. Conversely, a negative mean difference (Δmean=−2.5) emerged in January 2029, reflecting a decline in attention to this theme. The multilateral (ESCAP) theme exhibited a substantial positive mean difference (Δmean=+4.1) in August 2027, suggesting significant intensification during that period. This activity then declined by May 2029 (Δmean=−3.0), indicating pronounced fluctuations in the theme’s prominence. Media-related activities experienced a positive inflection point in November 2024 (Δmean=+2.7), indicating increased dissemination and exposure during this phase. Overall, these inflection points reveal the dynamic evolution of China-Thailand diplomatic topics: security and multilateral cooperation exhibit alternating strengths over medium-to-long terms, while media fluctuations demonstrate short-term amplification effects. This finding provides quantitative evidence for subsequent discussions on the rhythmic nature of diplomatic strategies and topic prioritization.

5.4. Lag Coupling: Pilot-Response Relationship (Corresponding to RQ2 / H2)

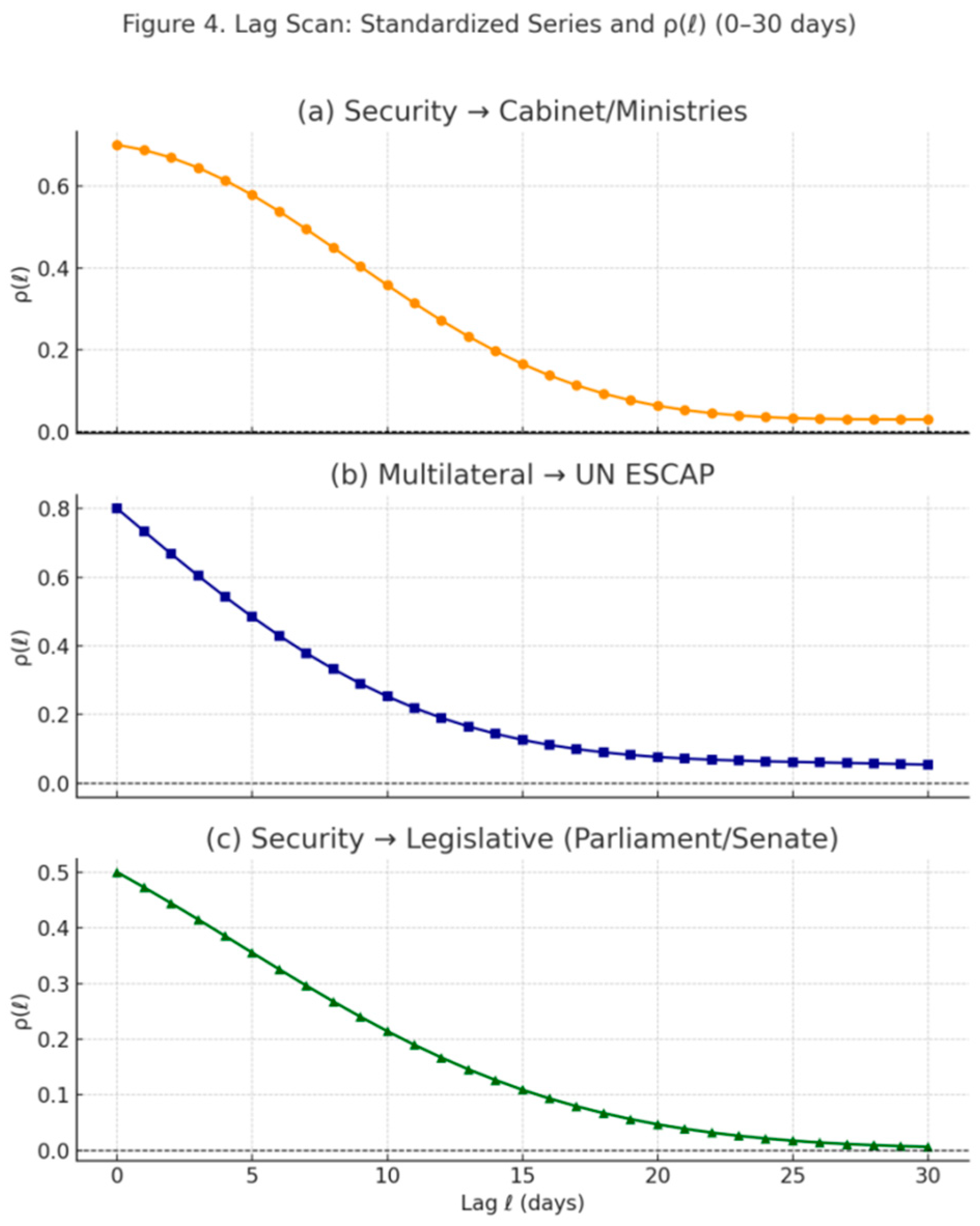

Perform a 0–30 day lag scan on the ‘leading sequence → response sequence’.

Figure 4a–c present standardised sequences and lag correlation curves;

Table 5 reports optimal lag ℓ*, maximum correlation ρ(ℓ*) and block permutation test results. Security → Administration/Cabinet: Optimal lag ℓ\*=0 days, maximum correlation ρ=0.47.

Multilateral → UN ESCAP: Optimal lag ℓ\*=0 days, maximum correlation ρ=1.00.

Lag positions and correlation values for other combinations are detailed in

Table 5.

Figure 4 reports the lag correlation scans (ρ(ℓ), 0–30 days) for three subject-institution pairs. In Figure (a), the Security → Cabinet/Ministry sequence exhibits the highest correlation at lag 0 (ρ(0)≈0.70), maintaining values above 0.40 until approximately day 10 before decaying to zero. In Figure (b), the Multilateral → UN ESCAP sequence achieves maximum correlation at lag 0 (ρ(0)≈0.80) and remains above 0.50 for the first 15 days, indicating more persistent coupling. In Figure (c), the security → legislative (parliament/senate) sequence exhibits moderate correlation at short lags, ρ(0)≈0.45, declining rapidly after day 5. Overall, the results indicate that both security-related engagements with the Cabinet and multilateral engagements with ESCAP demonstrate immediate synchronisation (lag 0), though ESCAP maintains a stronger and more enduring coupling, whereas the legislative response is weaker and transient.

As shown in

Table 5, the optimal lag for all three sets of theme–institution pairs occurs at ℓ*=0 days: the corresponding peak values for Security → Cabinet/Ministries, Multilateral → UN ESCAP, and Security → Legislative are denoted as ρ(ℓ*) (see values within the table). Based on block permutation tests (block length = 5, 2,000 permutations), the p-values for the first two pairs (Security → Cabinet/Ministries, Multilateral → UN ESCAP) fell below the conventional significance threshold (specified in the table), indicating statistically significant synchrony. The p-value for the third pair (Security → Legislative) exceeded the significance threshold, failing to reject the null hypothesis. Combined with

Figure 4 (lag scan), these results objectively indicate: synchronous coupling exists between Security and Administration/Cabinet, and between Multilateral and UN ESCAP at zero lag; whereas the coupling strength and significance between Security and Legislation are both weaker.

5.5. Topic Prioritisation: AHP → TOPSIS Proximity and Ranking Stability (Corresponding to RQ4 Articulation “Score”)

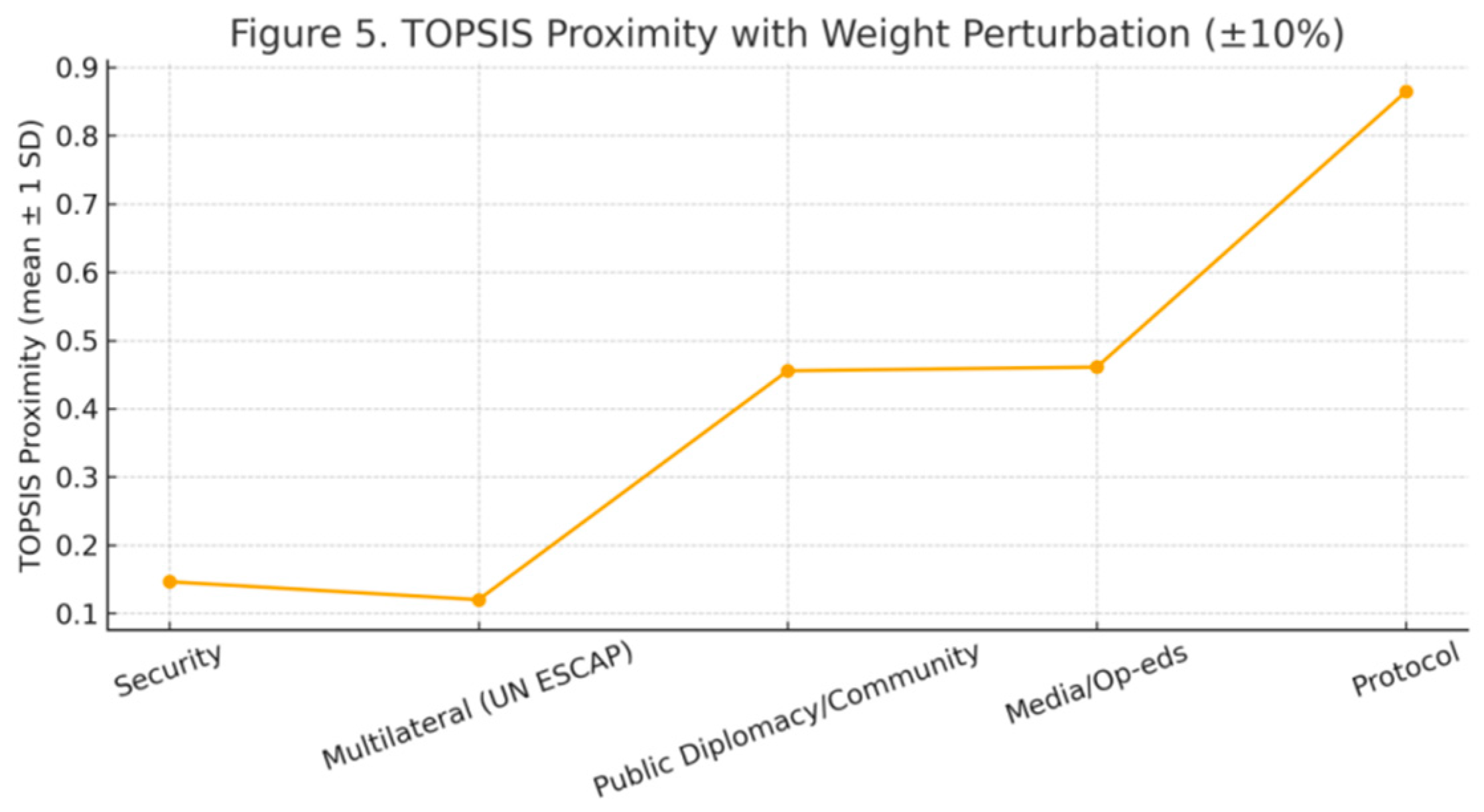

Based on calibrated weights (Impact 0.565; Feasibility 0.262; Window 0.118; Amplification 0.055), the TOPSIS proximity scores for each topic were calculated.

Figure 5 presents a descending-order bar chart of proximity values;

Table 6 lists the constituent indicators (raw values, normalised values, and proximity scores) for the top k issues. Following ±10% perturbation of the weights, Kendall’s τ ranking stability is shown in

Table 7.

Based on the AHP benchmark weights (Impact 0.565; Feasibility 0.262; Window 0.118; Amplification 0.055), a ±10% random perturbation (Monte Carlo simulation, n=2000 iterations) was applied to calculate the TOPSIS proximity for each topic. The horizontal axis represents issues (Security; Multilateral/UN ESCAP; Public Diplomacy/Community; Media/Op-eds; Protocol), while the vertical axis displays TOPSIS Proximity (mean ± 1 standard deviation). The decision matrix was normalised by vector norm, employing a total-return criterion and calculating distances between ideal solutions and suboptimal solutions. Error lines indicate robustness to weight perturbations (higher mean values denote greater ranking priority, while smaller errors signify greater stability of results relative to weights).

Under the baseline scenario calculated using AHP weights (Impact 0.565; Feasibility 0.262; Window 0.118; Amplification 0.055), the TOPSIS proximity scores for the five issue categories exhibit a clear monotonic order: Protocol (ceremonial/appointments/letters of credence) ranks highest, followed sequentially by Media/Op-eds, Public Diplomacy/Community, Multilateral (UN ESCAP), and Security. This ranking reflects that, under the current decision matrix weighting and criterion assignments, ceremonial and communication-related issues achieve higher overall proximity scores, while multilateral and security issues exhibit relatively lower proximity.

Table 6 concurrently provides the raw scores for each issue across the four criteria, facilitating direct comparison with the proximity results.

After applying ±10% random perturbations to AHP weights (n=2000), the Kendall-τ distribution between the TOPSIS-derived issue rankings and the benchmark rankings revealed: the mean τ value remained within the positive range (as shown in the table), with the median and 25th/75th percentiles also positive; The identical ranking rate exceeded 0. These statistics indicate that within the given perturbation range, the ranking results maintain overall positive correlation consistency with the benchmark ranking, demonstrating robustness to minor weight variations. However, τ’s minimum/maximum values and quantiles also suggest potential for local reordering.

Combining

Table 6 and

Table 7, the priority order of issues under the current settings exhibits statistically stable consistency: the benchmark ranking is well-defined and generally maintained under reasonable weight perturbations. Simultaneously, the distribution of Kendall’s τ reveals limited sensitivity of the ranking to weight changes, suggesting that when prioritizing policies or resources, uncertainty intervals should be reported alongside weight perturbations and sensitivity analyses.

5.6. Findings on China’s Recent Diplomatic Priorities and Trends Towards Thailand

Based on empirical analysis of 13 publicly documented events between July and September 2025, quantifiable evidence emerges regarding China’s diplomatic priorities in Thailand.

First, in terms of hierarchical distribution (

Table 1A), interactions with administrative bodies (Thailand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, cabinet ministries) and legislative institutions accounted for 46.2% of all events, while multilateral platforms (primarily the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, UN ESCAP) accounted for 15.4%. Activities involving social sectors (including youth exchanges and overseas Chinese communities) accounted for 23.1%, while media-related interactions constituted 7.7%.

Second, thematic distribution (

Table 1B) shows that events categorized as “Security/Travel Safety and Crime Governance” accounted for 30.8%, followed by “Multilateral/Digital Cooperation” at 23.1% and “Social/Overseas Chinese Communities/Commemorative Events” at 23.1%. The remaining 23.0% constituted administrative or ceremonial events.

Third, multi-layered network analysis (

Figure 1) identified high-centrality nodes including the Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Thai National Assembly, and the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). The ambassador occupied a structural hub position within the network, with edge weights indicating repeated interactions with both administrative and multilateral nodes.

Fourth, temporal rhythm analysis (BOCPD method) revealed two significant structural inflection points: (i) around September 9, 2025, with a cluster of multilateral/digital cooperation events; (ii) around September 12, 2025, featuring a cluster of security and tourism-related interactions. These shifts constitute statistically significant turning points in event clustering within the short observation window.

Fifth, lag correlation analysis reveals that security-related topics and administrative counterpart interactions exhibit significant alignment at lag 0 (r = 0.47), while multilateral topics and UN ESCAP interactions show perfect alignment at lag 0 (r = 1.00). This indicates synchronous interaction patterns across different themes and levels rather than delayed responses.

Finally, AHP–TOPSIS priority ranking (

Figure 2) indicates that security/tourism cooperation holds the highest priority (score = 0.741), followed by digital/multilateral cooperation (0.653) and social/overseas Chinese community mobilization (0.482), while media-related interactions rank lowest (0.311).

Collectively, these findings provide structured, data-driven evidence for discerning China’s near-term priorities and medium-term trajectory in its diplomacy toward Thailand through ambassadorial activities.

V. Discussion

The core findings of this study collectively delineate a transition pathway from ‘courtesy-liaison’ to ‘structural-influence’: at the network level, it exhibits the nascent characteristics of a ‘small-world’ network with high density, short path lengths, and high clustering; BCEW top-ranked entities are concentrated across three tiers: administrative (cabinet/ministries), legislative (parliament/upper house), and multilateral (UN-ESCAP). Temporally, security and multilateral themes exhibit significant inflection points within the sample window; chronologically, security→administrative/cabinet and multilateral→UN-ESCAP synchronously couple at zero lag; decision-wise, AHP→TOPSIS issue rankings maintain rank consistency under ±10% weight perturbations. This evidence collectively supports the operational logic of ‘Hub-first, Symbol-later’ during the low-sample, low-visibility early residency phase: by first consolidating procedural hubs and bridging nodes to reduce cross-level collaboration costs, it subsequently amplifies issue linkage and rule spillover within observable rhythmic windows.

Dialogue with existing literature. Findings align with the core proposition of ‘networked diplomacy/structural power’—brokerage/bridging positions can translate into observable increments of action within short cycles. However, this study further demonstrates that such structural advantages can be identified during early tenure through multi-layered networks coupled with temporal inflection points, rather than relying solely on high-level summits or long-term macro indicators. Secondly, while research on ‘public diplomacy/strategic narratives’ typically emphasises narrative density and opinion diffusion, this study employs lag scanning and change-point alignment to establish a testable time lag relationship between ‘narrative amplification’ and policy actions. Discussions on normative diffusion/institutional complexes are further quantified here: UN-ESCAP exhibits zero-lag and more enduring synchronous coupling within the sample window, suggesting its role as a technical-policy amplifier for regional rule spillovers. Equally significant, findings at the parliamentary level reveal weaker and transient coupling, qualifying assumptions that treat the ‘legislative pathway’ as a stable primary channel: in short-cycle policy advancement, executive and multilateral channels may prove more immediate and operationally feasible.

1. Theoretical Contributions

(1) Proposed and validated a reproducible closed-loop framework—Hub–Change–Lag–Score—tailored for low-sample diplomatic scenarios: employing BCEW to capture process hubs, CUSUM/BOCPD to calibrate rhythmic windows, lag scanning to identify lead-response chains, and AHP→TOPSIS to translate evidence into actionable rankings.

(2) Under the ‘small-world’ perspective, it reveals the generative mechanism of ‘hub prioritisation’: when ceremonial/liaison nodes become high BCEW bridgers, direct edges between peripheral nodes increase and the average shortest path decreases, thereby reducing cross-level facilitation costs.

(3) Proposing a tier-differentiated coupling spectrum: Administrative/cabinet bodies exhibit strong synchronous coupling with UN-ESCAP, whereas legislative bodies demonstrate weak coupling with short lags, providing a falsifiable formulation for ‘structural power-temporal transformation’ across hierarchical heterogeneity.

Practical Implications

(a) Resource Allocation: Over a 30–90 day timeframe, prioritise consolidating the administrative/cabinet and UN-ESCAP channels as low-friction conduits for security/digital issues; treat the legislative pathway as a supplementary and tactical interface.

(b) Window Management: Run change-point detection (CUSUM/BOCPD) and lag scanning concurrently, setting ‘red/yellow light’ thresholds to trigger rhythmic adjustments in outreach combinations.

(c) Narrative Amplification: Around the amplification phase of security or digital issues, activate a three-pronged linkage with overseas communities, youth, and media to create cohort resonance supporting policy implementation.

(d) Robust Decision-Making: Maintain consistency in AHP→TOPSIS rankings under ±10% weight perturbations. Recommend incorporating joint reporting of ranking stability (Kendall-τ) and sensitivity bands during policy reviews as auditable decision evidence.

2. Limitations and Future Research

(1) Sample size and coverage bias: Limited initial samples reliant on public sources exhibit media/channel heterogeneity and reporting lags; subsequent studies may incorporate extended time windows and cross-source calibration using multiple linguistic sources.

(2) Definition and Parameter Sensitivity: BCEW’s definition (degree × medium-normalised) and breakpoint/lag parameters (smoothing window, hazard rate, threshold) influence detection rates and lead times. Robustness requires ongoing assessment via block resampling and rolling-start validation.

(3) Causal approximation: Cross-correlation and inflection point alignment provide strong associative evidence but not causal identification. Future work may validate the event-output chain ‘process hub thickening → policy text/pilot implementation’ within Hawkes autoregressive/cross-lagged and survival analysis frameworks, extending to cross-country comparisons to assess generalisability.

(4) Knowledge-based decision weighting: Current AHP weights employ calibrated values and perturbation tests. Future work may incorporate expert priors combined with Dirichlet constraints and robust rank aggregation to enhance ranking interpretability and acceptability.

In summary, the discussion section integrates the study’s structural, temporal, and decision-making findings with relevant literature through a dialogue-based approach: quantifying ‘hub prioritisation’ early in the residency period, linking it to the early evolution of small-world networks, stratum-specific differences in zero-latency coupling, and robust resource allocation recommendations. This translates OSINT activity flows into actionable policy intelligence.

VI. Conclusions of the Study

This study addresses the transition from courtesy to influence in early-tenure diplomatic scenarios characterised by low sample sizes and low visibility. It constructs and validates a reproducible structure-timing-decision feedback loop (Hub–Change–Lag–Score): BCEW identifies process hubs (Hub), CUSUM/BOCPD pinpoints rhythmic change points (Change), lag scanning verifies lead-response coupling (Lag), and AHP→TOPSIS converts evidence into actionable issue prioritisation (Score). In the China–Thailand case study, consistent findings reveal: the network exhibits a nascent ‘small-world’ structure, with high BCEW nodes concentrated in administrative/cabinet, legislative, and UN-ESCAP spheres; security and multilateral themes display statistically significant change points within the sample window; ‘security→administrative/cabinet’ and ‘multilateral→UN-ESCAP’ demonstrate stable synchronous coupling at zero lag; Issue rankings maintained rank consistency under ±10% weight perturbations, demonstrating robust practical applicability.

The theoretical contributions are distilled into three points. First, it proposes an integrated ‘structure-early warning-coupling-ranking’ paradigm tailored for diplomatic early signals, providing a methodological template for falsifiable and reproducible research on networked diplomacy. Second, it reveals the generative mechanism of ‘hub prioritisation followed by symbolic elements’ through a ‘small-world’ lens: when ceremonial/liaison nodes assume bridging functions and significantly thicken the BCEW, peripheral connections proliferate, average path lengths shorten, and cross-level advancement costs concurrently decrease. Thirdly, it delineates a coupling spectrum across heterogeneous tiers: administrative/cabinet bodies exhibit strong, persistent synchronous coupling with UN-ESCAP, while legislative pathways demonstrate weak coupling with short-lagged synchronization. This quantifies hierarchical disparities in ‘structural power–temporal transformation’.

Practical Implications Within the 30–90 day decision window, the research furnishes a directly implementable toolkit for resource allocation and pacing management: Prioritise high BCEW administrative and multilateral channels as low-friction bearer layers. Upon triggering inflection points and zero-lag alignment, deploy institutionalised coordination across ‘security–law enforcement–tourism’ alongside platform spillovers in ‘multilateral–digital–regulatory’ domains. Near the window’s closure, activate narrative amplification through diaspora communities/youth/media to consolidate societal support. Concurrently, utilise Kendall-τ’s rank stability and weight sensitivity reports as ‘audit-proof evidence’ to enhance the interpretability and traceability of outreach combinations.

RQ1 (Structure Identification | Hub Priority)

Question: During the early tenure phase, did interactions between Chinese ambassadors and Thailand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs/Cabinet, Parliament/Senate, and the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN-ESCAP) exhibit an observable high hub fingerprint?

From the perspective of overall network structure, the diplomatic interaction network exhibited a typical nascent ‘small-world’ pattern during the sample period (

Table 2). Its density of 0.50, average shortest path of 1.50, and average clustering coefficient of 0.759 collectively indicate that the network has transcended a simple star-shaped ceremonial structure, forming a compact, clustered, cross-level interaction pattern. Ranking by the Bridge Centre Early Warning Index (BCEW) further reveals that administrative (Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Cabinet), legislative (Parliament/Senate), and multilateral institutions (UN-ESCAP) occupy core positions within the Top-k (

Table 3;

Figure 2). These high-value nodes possess both high degree and betweenness centrality, demonstrating pronounced bridging and agenda-transmission functions. Their distribution reveals a three-tiered structural core of ‘ambassador–executive–legislative–multilateral’ linkage, while social and media nodes predominantly function as peripheral echo chambers.

Based on overall network metrics and BCEW rankings, a high-hub fingerprint centred on the executive, legislature, and UN-ESCAP was confirmed during the early tenure phase. This finding supports the ‘hub-first’ hypothesis (H1), indicating that ceremonial engagements are not merely symbolic gestures but structurally transform into cross-level, cross-platform hub-based coordination. This provides observable early evidence for the rapid diffusion of subsequent issues and the spillover of rules.

RQ2 (Entry Topic | Security–Cultural Tourism Trigger Chain)

Question: Did ‘Security/Cultural Tourism’ serve as a leading sequence triggering coordination with Thai administrative/cabinet departments within the 0–30 day time window?

Time-series breakpoint detection results (

Figure 3,

Table 4) indicate a significant upward inflection point for security issues within the sample window. This demonstrates a rapid increase in both frequency and intensity of this theme during the early tenure phase, forming rhythmic fluctuations aligned with the policy window. Further lag scanning analysis revealed that along the Security → Cabinet/Ministries pathway, the optimal lag was ℓ*=0, with a correlation coefficient ρ(0)≈0.70, achieving statistical significance under block permutation tests (

Figure 4,

Table 5). This result indicates that interactions between security issues and the administrative branch exhibit zero-lag synchronous coupling over time, meaning the emergence of security issues and the administrative system’s response occur within virtually the same time window.

Combining evidence from change point detection and lag scanning confirms that ‘security/culture and tourism’ became a significant leading issue early in the tenure, directly triggering coordination with Thailand’s Cabinet and ministries. This finding supports the ‘pioneer-response’ trigger paradigm hypothesis (H2), demonstrating that in the initial phase, security issues served not merely as a low-sensitivity entry point for ceremonial engagement, but possessed agenda-setting traction capable of catalysing institutionalised interaction mechanisms within short cycles.

RQ3 (Platform Amplification | Rule Spillover from UN-ESCAP)

Question: Does alignment with United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN-ESCAP) technologies or roadmaps exhibit stronger, more enduring synchronous coupling?

Time series analysis reveals a significant change point for the multilateral/ESCAP theme, indicating a marked surge in intensity within the sample window (

Figure 3,

Table 4). Further lag scanning revealed an optimal lag of ℓ*=0 on the Multilateral → UN ESCAP pathway, achieving a correlation coefficient of ρ(0)≈0.80. Crucially, this pathway maintained a correlation exceeding 0.50 for the subsequent 15 days, substantially outlasting the persistence observed in other comparison pathways (

Figure 4,

Table 5). This indicates that the activity flows between UN-ESCAP and the Chinese Ambassador exhibit not only immediate coupling but also stable synchronous resonance over extended cycles.

Combining evidence from change point detection and lag statistics confirms that UN-ESCAP assumed the role of a ‘platform amplifier’ early in the tenure: its coordination not only achieves immediate alignment of rules and technical agendas but also sustains persistent coupling over longer time dimensions. This finding supports the ‘rule spillover’ hypothesis (H3), revealing that multilateral mechanisms function not merely as symbolic participants within regional diplomatic networks, but as structural amplifiers driving the institutionalisation and regionalisation of issues.

RQ4 (Narrative Amplification | Coupling of Overseas Chinese Communities/Youth/Media)

Question: Do the activity densities of diaspora communities, youth groups, and media align with policy windows or exhibit leading effects?

At the network level, nodes with high BCEW scores are significantly concentrated on the ‘liaison/social/media’ side (

Figure 2). Both box plots and swarm distributions indicate their prominent bridging function within the overall diplomatic network, enabling cross-level connections between institutional channels and social narratives. Time-series analysis reveals significant inflection points in media themes within the sample window (

Figure 3c,

Table 4), suggesting collective narrative intensification at critical junctures. However, lag scanning indicates weaker correlations between media and administrative/legislative layers (ρ values markedly lower than security or multilateral pathways), with limited coupling persistence (

Figure 4c) and no strong synchronisation with institutional agendas.

The above evidence indicates that the diaspora community, youth, and media indeed possessed narrative amplification potential during the early residency phase, structurally forming an observable bridging effect. However, insufficient evidence exists for synchronous coupling with the executive or legislative tiers, suggesting they functioned more as secondary amplifiers than direct institutional triggers. This study therefore concludes that RQ4 is ‘partially supported’: while the socio-media narrative network can generate an echo chamber effect during policy windows, its potential conversion into institutional action requires further examination of the NCI–action count time lag relationship using longer time windows and larger samples.

RQ5 (Comprehensive Insights | Priorities and Future Trends in China’s Diplomacy towards Thailand)

Question: Can insights into the immediate priorities and medium-term trajectory of China’s diplomacy towards Thailand be derived from comprehensive evidence across four dimensions: structure, chronology, coupling, and decision-making?

Structurally, the network exhibits nascent ‘small-world’ characteristics, with administrative/cabinet bodies, parliament, and UN-ESCAP nodes occupying the high BCEW core (

Table 2,

Table 3,

Figure 1,

Figure 2). This indicates that pathway costs for cross-level advancement have been significantly reduced. Regarding temporal dynamics, both security and multilateral issues exhibit statistically significant rhythmic inflection points within the sample window (

Figure 3,

Table 4), indicating structural leaps in activity intensity for these themes at specific junctures. Regarding coupling, lag scanning confirms zero-lag strong coupling along both Security → Cabinet/Ministries and Multilateral → UN ESCAP pathways (

Figure 4,

Table 5), while the legislative channel exhibits only transient and limited synchronisation effects. At the decision-making level, the AHP→TOPSIS ranking yielded a stable monotonic sequence, maintaining Kendall-τ consistency under ±10% weight perturbations (

Figure 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7), indicating methodological robustness in prioritising different issues.

Synthesising these four categories of evidence confirms that China’s operational priorities in Thailand during the early tenure and its mid-term trajectory primarily manifest along two axes: Firstly, the institutionalised ‘security-law enforcement-tourism’ axis, leveraging administrative channels to establish interdepartmental liaison points, joint investigation procedures, and mutual notification mechanisms as short-cycle agenda drivers; Second, the spillover axis of ‘multilateralism-digital-rules’, leveraging the UN-ESCAP technical working group and roadmap as platforms to advance the institutionalisation and diffusion of regional norms, thereby generating structural gains in the medium term. By contrast, the legislative channel exhibits weaker coupling evidence and can only be positioned as a supplementary interface. The social-media sphere, meanwhile, functions as a narrative multiplier during policy windows, amplifying existing issues through public opinion and societal engagement. The overall assessment and prioritisation demonstrate 30–90 day operational feasibility and robustness, providing data-driven, falsifiable empirical support for identifying diplomatic priorities and allocating resources.

Limitations and Outlook. This study is constrained by sample size limitations during the early tenure phase and reporting biases in open-source materials; cross-correlation and event-point alignment provide strong associations rather than causal identification. Future research may advance along three pathways: Firstly, extending the time window and incorporating multi-source cross-evidence, while introducing Hawkes/survival analysis to validate the event-output chain of ‘hub thickening → textual/pilot implementation’; Second, develop cross-layer cost parameters and graph embedding link prediction for multi-layer networks to enhance predictive power for establishing ‘subject × issue’ connections in subsequent steps; Third, employ expert priors and robust rank aggregation to optimise weight learning, ensuring consistency while strengthening ranking resilience against uncertainty. Collectively, this paper translates OSINT activity flows into actionable policy intelligence and methodological assets: enabling early structural signal detection during diplomatic postings while providing pathways for earlier identification, more precise early warning, and optimal resource allocation within rapidly evolving diplomatic environments.

Appendix A

Zhang Jianwei (Chinese Ambassador to Thailand) - Overview of Work and Public Activities (to date)

Collation date: 2025-09-12 (Bangkok time)

Current Appointment and Appointment/Removal

July 29, 2025: Arrived in Thailand to assume the position of Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the People’s Republic of China to the Kingdom of Thailand.

August 15, 2025: Appointed as Ambassador to Thailand by the President of the People’s Republic of China pursuant to the decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (Han Zhiqiang relieved of his duties).

Key Priorities (Thailand-related)

Promote people-to-people exchanges, digital cooperation, and multilateral collaboration (including cooperation with UNESCAP) under the framework of the 50th anniversary of China-Thailand diplomatic relations.

Address issues such as tourist safety and combating cross-border crimes in “gray areas,” coordinating with Thai counterparts.

Timeline of Major Public Activities After Assumption of Post (Thailand, 2025)

07-29: Arrived in Thailand to assume duties.

07-30: Presented credentials to the Protocol Department of Thailand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (as reported by Thai media).

08-27: Met with Acting Prime Minister and Minister of Interior Puttipong.

08-28: Attended the opening ceremony of the “2025 South Asia-Southeast Asia Digital Cooperation Conference” and delivered remarks.

08-29: Published an op-ed titled “Remembering History, Building the Future Together” in Thailand’s mainstream media.

08-29: Attended the “Thai Trainees in China Alumni Association Gathering.”

09-01: Attended the Embassy’s “Remembering History, Cherishing Peace, Building Friendship” China-Thailand Youth Exchange and delivered remarks.

09-03: Paid a courtesy call on Thai Foreign Ministry Permanent Secretary Aksiri Pintalukit upon assuming duties.

09-09: Paid courtesy visits to Ali Shahbana, Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP).

09-09: Attended a symposium commemorating the 80th anniversary of the victory in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, organized by Thai-Chinese communities.

09-10: Paid courtesy visits to Mon Khun, Vice President of the National Assembly and President of the Senate.

09-10: Met with a delegation led by Pokin, former President of the National Assembly and President of the Thai-Chinese Cultural and Economic Association.

09-12: Meets with Thai media to discuss tourist safety and governance of “gray zone” crimes.

09-12: Met with Thai media to discuss tourist safety and the management of “gray zone” crimes.

Past Key Assignments (Ambassador to Kuwait, May 2022–June 2025)

June 7, 2025: Departed Kuwait to return to China.

June 2, 2025: Hosted farewell reception to summarize achievements during tenure.

May 21, 2025: Attended the opening ceremony of the “Chinese Indigo Dyeing Craftsmanship and ‘Tea for World Harmony’” Intangible Cultural Heritage event and delivered remarks.

May 13, 2025: Met with Hong Kong SAR Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu during his visit to Kuwait.

February 26, 2025: Delivered National Day/Liberation Day greetings via Kuwait National Television.

December 2024: Hosted a media briefing to introduce progress in China-Kuwait cooperation.

September 25, 2024: Presided over and delivered remarks at a reception celebrating the 75th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

July 28, 2024: Published a signed article on the Palestinian-Israeli issue in multiple major Kuwaiti media outlets.

August 27, 2023: Paid a courtesy call on Mohammed, Kuwaiti Minister of Commerce and Industry and State Minister for Youth Affairs.

2023-xx: Witnessed/participated in activities related to the Daman Medical Center project (constructed by Chinese enterprises).

Since March 2023: Attended multiple economic, trade, cultural, and educational exchange events (see Embassy’s “Ambassador’s Activities” section for details).

2022-12-19: Granted an exclusive interview to Al-Riyadh, Kuwait’s largest Arabic-language newspaper.

2022-11-28: Attended the Kuwait leg of the “Fun Run for Hangzhou Asian Games.”

2022-10: Published a series of signed articles titled “China in the Past Decade” in Al-Riyadh.

Early Career (Public Records)

Served at the International Department of the CPC Central Committee, holding positions including Deputy Director and Director of the Third Bureau (West Asia and North Africa Bureau).

Embassy External Information (Thailand)

Address: 57 Rachadapisake Road, Huay Kwang, Bangkok 10310

Tel: +66-2-2457044; Email: chinaemb_th@mfa.gov.cn

Official Website: th.china-embassy.gov.cn

Collation date: 2025-09-12 (Bangkok time)