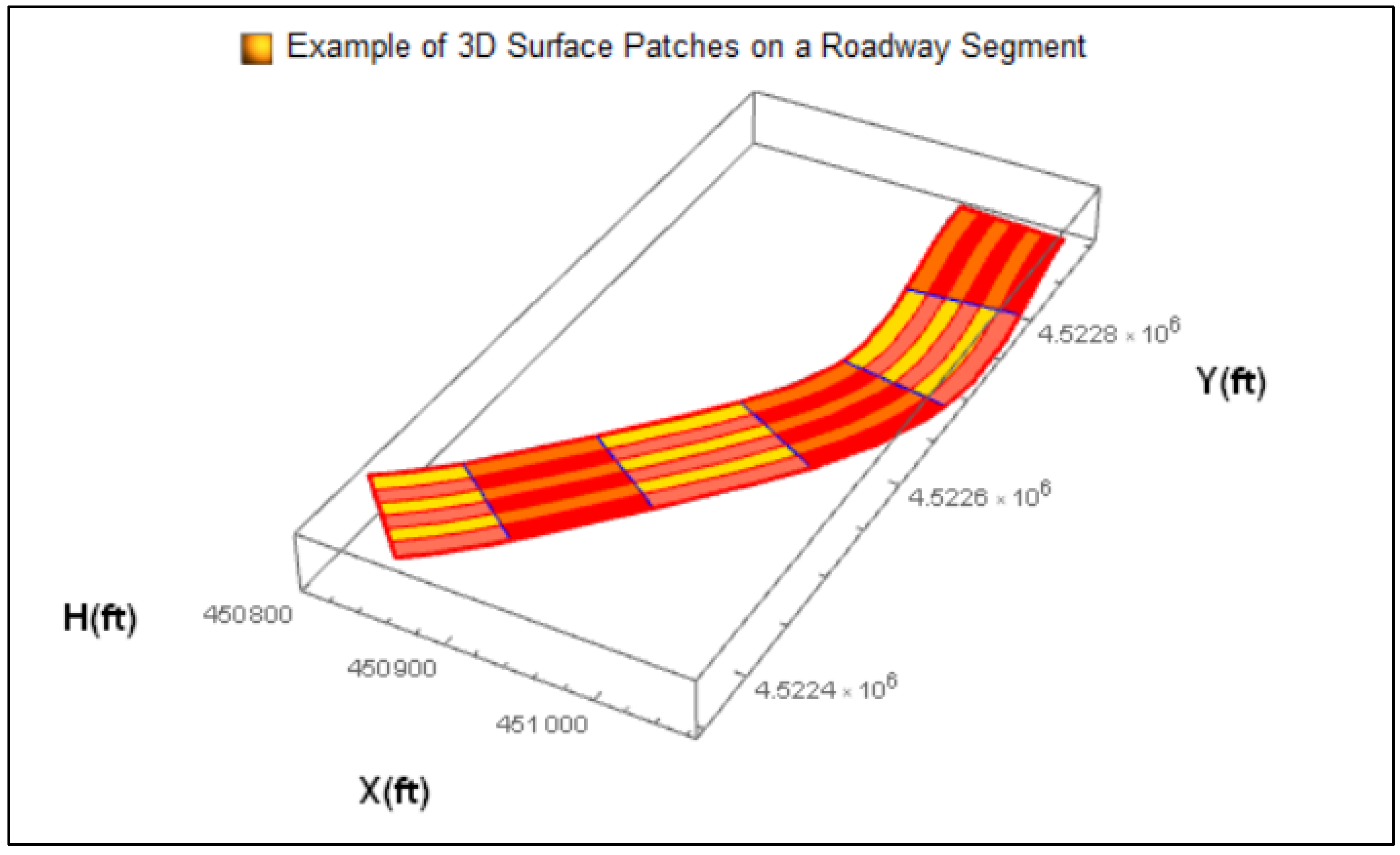

This section describes the way in which the final crash prediction models are developed. As noted above, six patch lengths, i.e. 1,500 ft, 1,000 ft, 400 ft, 200 ft, 100 ft, and 50 ft were considered. The length of the patch length denoted the way in which the 3-D roadway surface is spatially divided. However, no matter the patch length, in each patch there are four explanatory variables linked to it, namely: Number of crashes that occurred, AADT value, Gaussian Curvature (GC), and Mean Curvature (MC). In addition to the initial values of these variables, transformations were also considered, e.g. AADT2, GC2 MC3 in order to identify the optimal scale and combination of these variables. All of these transformations and the justification of the optimal scale are presented in Amiridis, K. 2019, Appendix F. Moreover, statistical interactions of the explanatory variables, e.g. Gaussian*Mean, are also considered. Finally, it should be noted here that the statistical regression model that was utilized is the Negative Binomial Regression because over-dispersion is present in the data and because it was intended to keep the statistics rather simple in order to retain the focus of the research on the use of 3-D geometric explanatory variables in highway safety rather than the statistical methods utilized per se. After all, the typical regression model that is utilized for crash prediction modeling is indeed the Negative Binomial Regression.

The analysis conducted will serve a dual purpose: 1) demonstrate the proof-of-concept of the proposed 3-D approach; and 2) evaluate the predictive power of the model. These two objectives can be viewed as independent, i.e., failure in demonstrating predictive power of the model does not mean that the proof-of-concept is violated. For example, 3-D metrics may be proven to have a statistically significant effect in crash modeling, but the reason for potential failure in adequately predicting actual crashes may simply rest on the fact that more explanatory variables are required in the model. The proof-of-concept relies on the verification that the 3-D differential geometry metrics of Gaussian and Mean curvature are statistically significant crash predictors. This can be successfully demonstrated if it is proven that the coefficients of the metrics are indeed statistically significant. It should be also noted that depending on whether historical crashes are available, two strategies come into play in order to predict crashes in the most effective way.

3.2.1. Proof-of-Concept

In order to provide the proof-of-concept in the most concrete way, all years, i.e. 2004-2017, and all seven roadways entered the same model which will be called “Integrated Model” (IM) to be distinguished from the models that will be developed for the second objective, i.e., prediction evaluation. The objective of this effort was to establish that it is meaningful to incorporate 3-D highway geometry in crash prediction models. Although the predictive power of the model was not evaluated at this point, this step was crucial because failure to address the statistical significance of the 3-D metrics in crash prediction, would yield any further discussion of prediction power evaluation meaningless. Moreover, the type of the final explanatory variables that will enter this model will function as the basis of the predictive power evaluation of the model. For example, if the variables, AADT, Gaussian2, and Mean3 are proven to be the finalists, then these exact variables would be considered in order to evaluate the predictive power of the model; a logic that holds true in most predictive models. For example, even for the variables than come into play in the SPFs in the HSM with a specific transformation, e.g., exp(AADT), does not mean that this particular transformation is the optimal in all cases; it simply means that this transformation is on average adequate.

Although not explicitly stated, a part of the statistical analysis essentially touches the field of spatial statistics since the selection of an acceptable patch length is of utmost importance because it functions as the basis of all further (traditional) statistical analysis. To proceed with this effort, a two-stage simultaneous testing was undertaken that would define the optimal patch length and model to be used. First, for each patch length considered, models with the variables of interest were developed and the most appropriate was selected in terms of statistical significance and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) evaluation criterion. Second, these models were then compared to identify the most appropriate patch for analysis and power of prediction evaluation. Since there are six patch lengths tested, six “final models” will eventually be compared to each other.

All of the combinations of the explanatory variables that were utilized until the final model was decided, for all patch length combinations, are detailed in Amiridis, K. 2019, Appendix G. The criterion according to which the models were compared was the AIC; the lower the AIC, the more informationally rich the model is. The AIC also functions as an adjusted R-square in the sense that it penalizes the number of variables that enter the model. Furthermore, in order for a model to be further considered as a finalist for additional evaluation, all of the coefficients of the explanatory variables that enter the model must be statistically significant, i.e., p-value<0.05. The demand of p-value<0.05 is associated with the fact that a significance level of 5% is considered; in fact, each p-value, depending on the number of explanatory variables that enter the model, must be less than the predefined “familywise” p-value, which in this case is set to 0.05, according to the Bonferroni, or any other type, correction (Myers et al. 2010). Roughly speaking, this means that if two explanatory variables are considered then the p-value of the coefficient of each variable must be less than approximately 0.025 ) assuming that the two explanatory variables are independent in order for the “overall p-value” to be less than 0.05.

More generally, the Bonferroni correction, or any other type of correction, should be applied when explanatory variables are simultaneously inserted in a statistical model. More specifically, the significance level has been assumed to be 5 percent, i.e., there is a 95 percent confidence that the true parameters belong in the constructed confidence interval. However, the significance level of 5% should not be applied to each coefficient, but to the model as a whole; therefore, in order for the significance level of the whole model to be kept at the 5 percent significance level, the p-value of each coefficient should be less than 5 percent. The value of each p-value in order to achieve a “family-wise” error of 5 percent is imposed by the pertinent correction method used, e.g. Bonferroni, Tukey, and by the number of variables; the more variables, the stricter, i.e. less, the p-value must be.

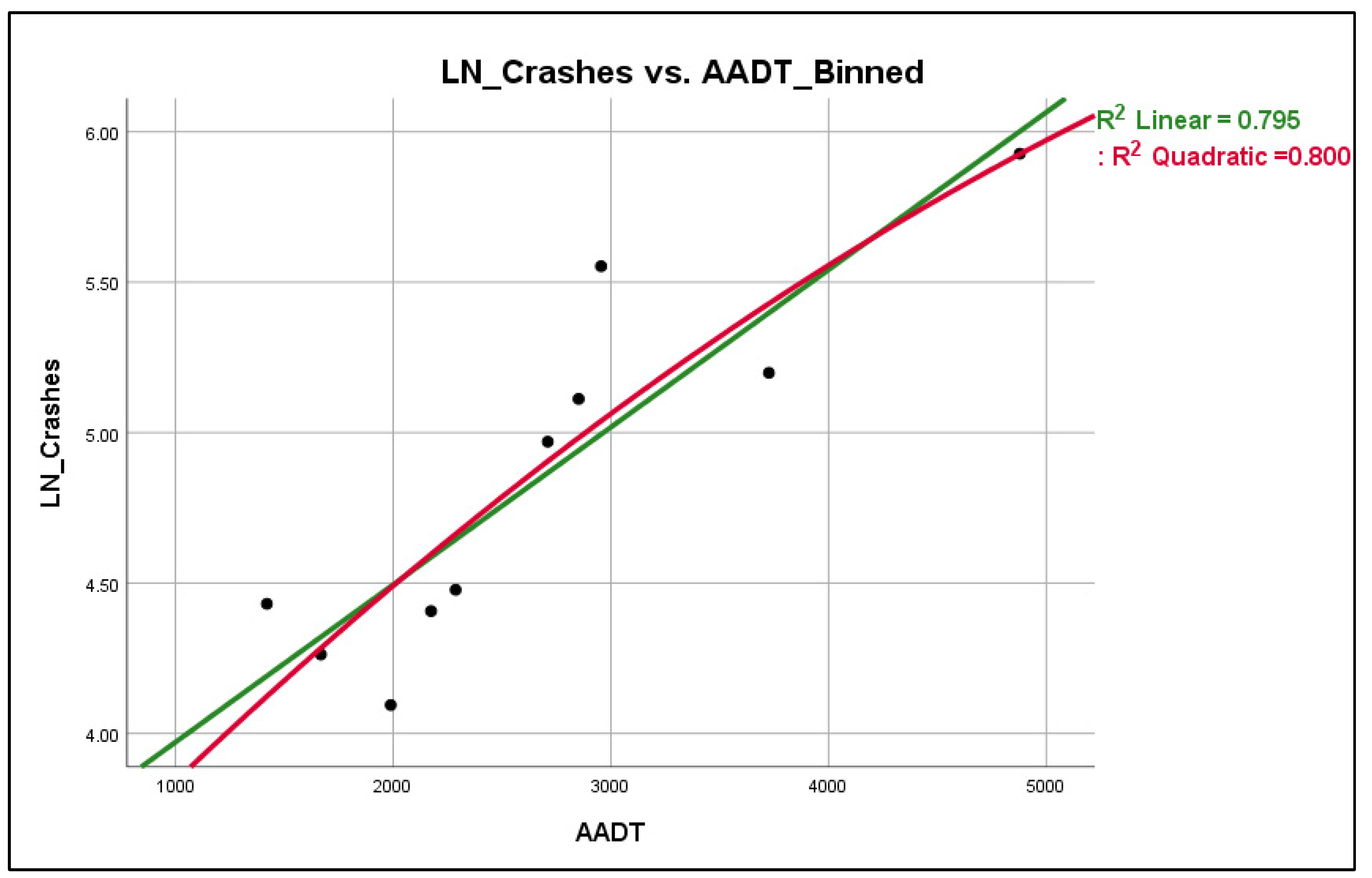

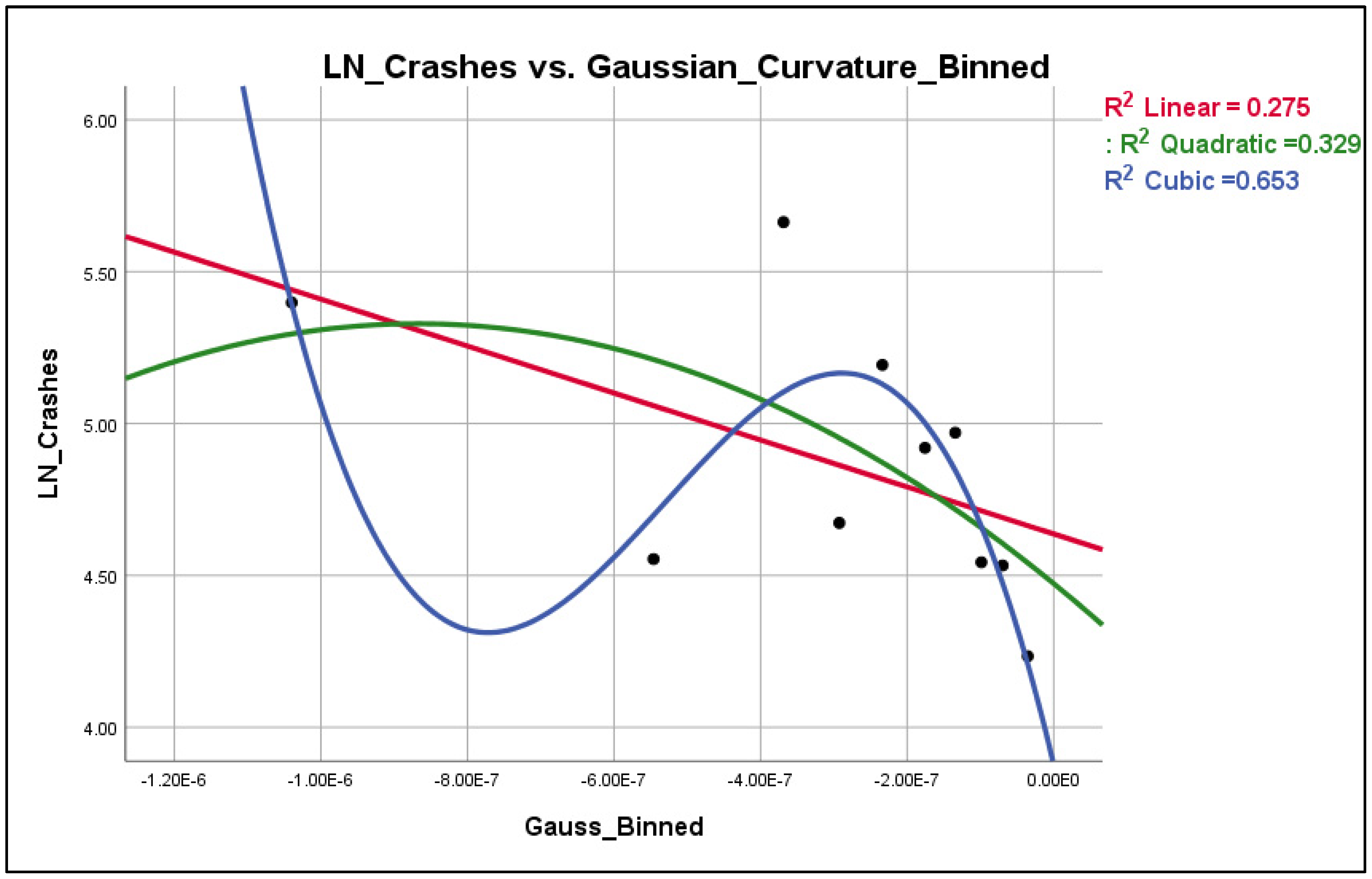

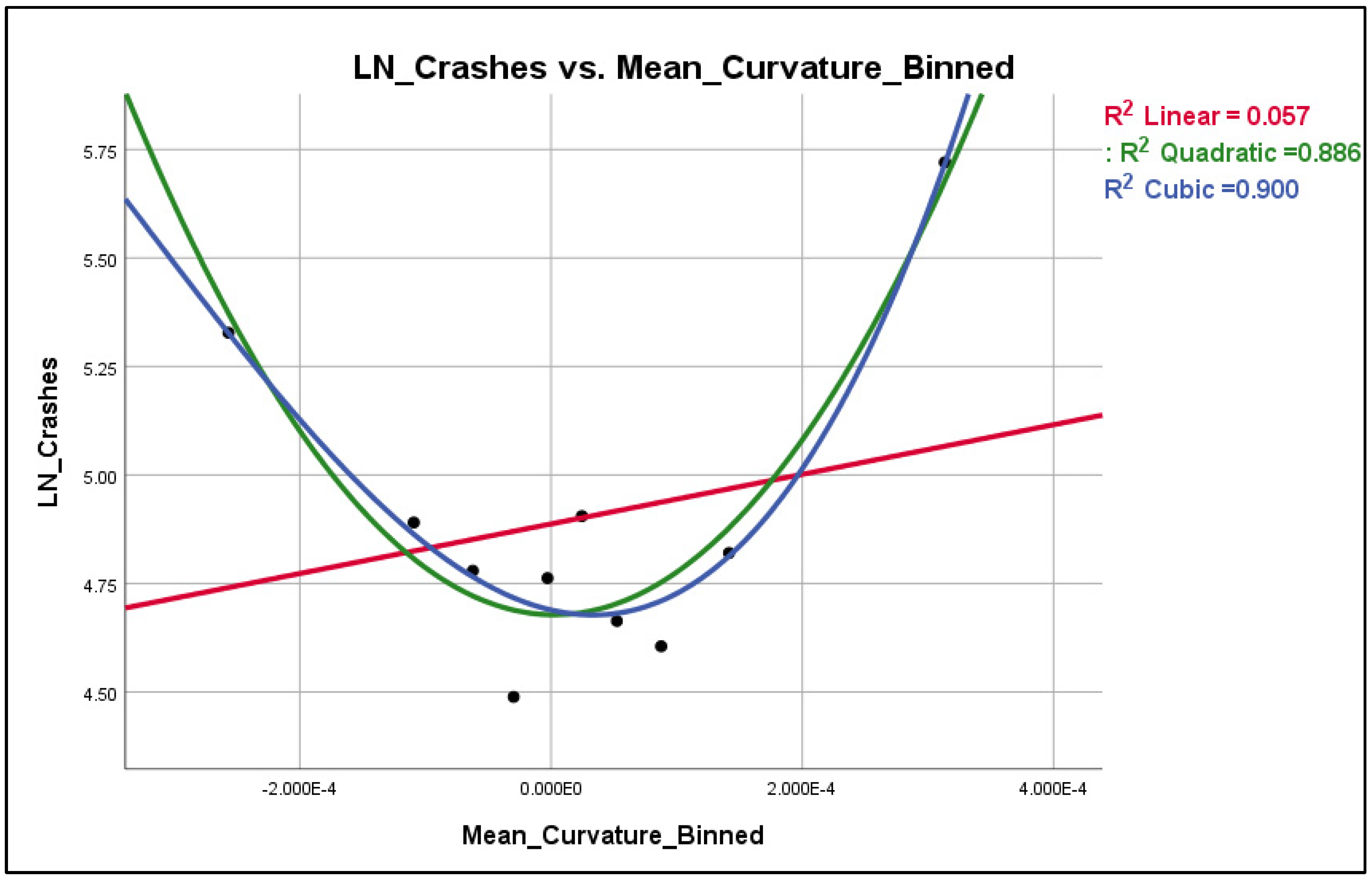

It should be noted here that the AADT, GC and MC are to be used as explanatory variables, i.e. main effects, in the statistical analysis through a multivariate regression analysis. However, even when multiple explanatory variables are intended to enter the model, the analysis should always begin by visualizing the explanatory variables vs. the dependent variable. The Negative Binomial Regression, which is the regression type that will be applied here is a member of the family of Generalized Linear Models (GLMs). Each regression member of the GLMs is associated with a function that is called the “canonical link function”, which actually represents the optimal transformation that should be applied to the dependent variable in order to satisfy desirable statistical properties such as unbiased parameters (Hardin and Hilbe 2012). In the case of the Poisson and Negative Binomial Regression, the aforementioned function is indeed the “log-link function”. If the logarithmic transformation is not applied to the dependent variable, then the so-called “identity link function” is applied, meaning that the dependent variable is simply the variable “Crashes”. Results will be produced even if the log-link function is not applied but the reliability of the results is weakened because the log-link function is the “canonical” link function for the Negative Binomial Regression. This is why the Poisson and Negative Binomial regression models are also often called log-linear models, meaning that the explanatory variables have a linear relationship with the logarithm of the dependent variable. Therefore, in this case the dependent variable will be LN(crashes).

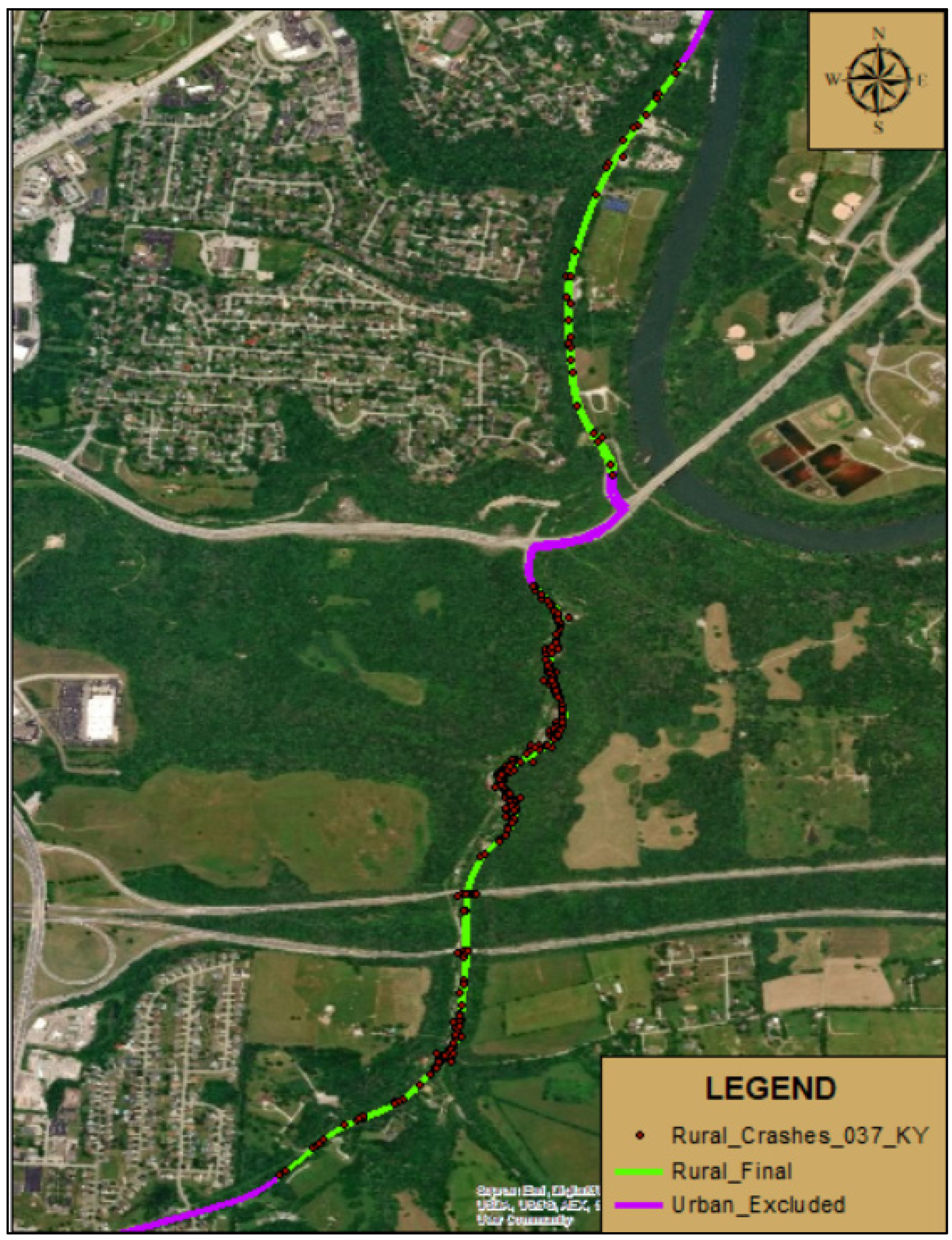

The typical visualization process in order to identify the optimal transformation of each explanatory variables is via scatterplots. The scatterplots for the explanatory variables AADT, GC, and MC are shown in

Figure 4.7, Figure 4.8 and Figure 4.9 respectively for the 100 ft patch.

Figure 4. 5.

Scatterplot LN(Crashes) vs. AADT_Binned.

Figure 4. 5.

Scatterplot LN(Crashes) vs. AADT_Binned.

Figure 4. 6.

Scatterplot LN(Crashes) vs. Average GC- Binned.

Figure 4. 6.

Scatterplot LN(Crashes) vs. Average GC- Binned.

Figure 4. 7.

Scatterplot LN(Crashes) vs. Average MC _Binned.

Figure 4. 7.

Scatterplot LN(Crashes) vs. Average MC _Binned.

According to

Figure 4.7, the AADT seems to have a rather linear relationship with LN(crashes), whereas the Gaussian curvature (Figure 4.8) seems to have a cubic relationship with LN(crashes) and the Mean curvature (Figure 4.9) has an essentially quadratic relationship with LN(crashes). However, these observations hold true only when the explanatory variables are plotted one by one against the dependent variable; in other words, there is no guarantee that the nature of these relationships will remain the same when all the explanatory variables enter the model. However, this procedure has revealed that, especially for the Mean and Gaussian curvature, there is some indication that their relationship may not be linear in nature with LN(crashes) and therefore quadratic and cubic transformations may be appropriate for testing.

For each patch, 38 variable combinations were tested until the analysis was finalized. The models considered each variable alone and in a variety of combinations in order to determine the most appropriate and meaningful combination. All these combinations for each patch length are presented in Amiridis, K. 2019, Appendix G. The process for determining whether a model was appropriate was based on an initial determination of whether all the coefficients of the model were statistically significant and accounting for the Bonferroni correction. Then the statistically significant models were compared with the AIC criterion. It is noted that, as a rule of thumb, when two models are compared and their AICs difference is greater than 10, then this difference is “significant”, meaning that the model with the lowest AIC should be kept instead (Hardin and Hilbe 2012). Finally, the assumptions according to which the model is based, e.g., normality of deviance residual distribution, must also be satisfied.

A summary of the variables used in the best models for each patch length are summarized in

Table 4.5. The final suggested models as shown in

Table 4.5 indicate that the Gaussian Curvature (GC) and Mean Curvature (MC) of 3-D surfaces play a crucial role in crash prediction since they are statistically significant in all models, in which the Bonferroni correction has also been accounted for. In fact, not only are the Gaussian and Mean Curvature statistically significant in all models, but their p-values are also less than 0.001 in all models. The insertion of these two differential geometry metrics it is actually the new aspect that this research introduces to the literature. The use of these metrics can be considered promising because the Gaussian and Mean curvatures are the cornerstones of the study of 3-D mathematical surfaces as a whole in differential geometry. Moreover, the fact that transformed geometric metric, e.g. GC

3 and MC

2, and that the 2-way interaction term GC*MC insert the model, in the 100 ft patch length model, emphasizes the complexity by which roadway geometry affects crash occurrence, a fact that cannot be revealed in such an explicit manner through conventional 2-D geometric metrics. Finally, in terms of computational statistics stability, when a variable is entered in a model with a power, e.g., quadratic, it is beneficial if the “lower power terms” are also included in the model, e.g. linear, for computational reasons. Fortunately, this is the case for both the GC

3 and MC

2 variables since the variables GC

2 and GC, as well as MC are also included in the model with p-values<0.001, meaning that even the Bonferroni correction is amply satisfied.

Table 4. 4.

Variables Present in Final Best Models for Each Patch Length.

Table 4. 4.

Variables Present in Final Best Models for Each Patch Length.

| Patch length |

Explanatory Variables |

| |

AADT |

GC |

MC |

GC2

|

GC3

|

MC2

|

MC3

|

AADT*MC |

GC*MC |

| 1500 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 1000 |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

| 400 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

| 200 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

| 100 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

| 50 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

The criterion used in order to select the most appropriate patch length was based on the overall error prediction which is estimated as the difference between the observed and model-predicted number of crashes. A summary of the predictive ability of each patch length, i.e., the associated error percentage to each, is shown in

Table 4.6; it is noted that 1,534 crashes occurred during the 2004-2017 period. Although it may be considered adequate on a practical basis to conclude that the 100 ft patch is the most pertinent patch length for the analysis, an additional statistical metric will also be considered to further validate this assertion, for the comparison among the different patch lengths. The additional statistical measurement used is the Predicted Error Sum of Squares or the so-called PRESS (Caroni and Oikonomou 2017). PRESS is used in order to compare regression models in terms of their ability to predict new values; the model preferred is the one with the smallest value of PRESS (

Table 4.6).

Table 4. 5.

Patch Length Comparison in Terms of Predictive Ability.

Table 4. 5.

Patch Length Comparison in Terms of Predictive Ability.

| Patch Length (ft) |

Predicted Crashes |

Error Percentage of Total Crashes Predicted |

PRESS |

| 1,500 |

1,295 |

-15.6% |

81.94 |

| 1,000 |

1,342 |

-12.5% |

51.63 |

| 400 |

1,582 |

3.1% |

47.40 |

| 200 |

1,546 |

0.8% |

20.90 |

| 100 |

1,532 |

-0.1% |

15.93 |

| 50 |

1,532 |

-0.1% |

15.76 |

The selected patch length for the final model corresponds to a length of 100 ft because it was observed that this patch length provides the best modeling ability. Even though a smaller patch length leads to an increase in the predictive power of the model, this was true up to a “cut-off” patch length, which in this case was estimated to be 50 ft. In this case, “cut-off” indicates that after a certain point the overall error is not practically improved with the reduction of the patch length.

The results of the model corresponding to the 50 ft patch were identical to the ones derived from the 100 ft patch (

Table 4.6). Moreover, a 100 ft patch may be considered more appropriate for transportation related applications because vehicles that have a length over 50 ft such as combination trucks, recreational cars, and buses can be analyzed in a more reliable manner by incorporating a larger surrounding roadway geometry. Therefore, for transportation related consistency, practical effect of overall error reduction as well as computational speed purposes it was decided to utilize the 100 ft patch for the crash modeling process.

The final model corresponding to the 100 ft patch length is summarized in

Table 4.7, whereas the regression model is presented in Equation 4. The AIC for the models considered ranged from 11,183 to 11,803. The final model that was kept was indeed the one with the lowest AIC of 11,183 while the second-best model had an AIC of 11,232. It is noted that all of the explanatory variables of the final have a p-value<0.001, a fact that essentially demonstrates the proof-of-concept of this research: 3-D geometric roadway metrics can successfully function as explanatory variables in crash predictive models.

Table 4. 6.

Coefficient Values of Final Model (E35) for Patch Length = 100 ft.

Table 4. 6.

Coefficient Values of Final Model (E35) for Patch Length = 100 ft.

| Variable |

Coefficient |

p-value |

| (Intercept) |

-4.2701 |

0.000 |

| AADT |

0.00037 |

0.000 |

| GC |

-797,670.9567 |

0.000 |

| GC2 |

-62,371,846,845.508 |

0.000 |

| GC3

|

-101,722,389,759,530.720 |

0.000 |

| MC |

347.8188 |

0.000 |

| MC2

|

209,377.3293 |

0.000 |

| GC*MC |

166,612,202.0693 |

0.000 |

As noted above, the presence of the Gaussian Curvature and Mean Curvature of 3-D surfaces supports the significance of these variables as crash predictors and the potential interaction with other variables; interactions that can by no means be captured in the 2-D analysis.

At this point, the “Integrated Model” in which all years and roadways are included has been finalized and presented in Equation 4 above. The IM essentially functions as a proof-of-concept for the inclusion of the 3-D metrics in crash prediction models and can, at least theoretically, be used for crash prediction purposes in other roadways. This model may be particularly useful when the purpose of an analysis is not the prediction of crashes in absolute numbers, but the comparison of alternatives, e.g. different alignments, in terms of estimating which alternative reduces crash frequency. In addition, it is suggested that the specific coefficient values (

Table 4.7) be used for crash prediction purposes only when no historical crash data are available; if crash data are available for a specific roadway segment they should be certainly used in order to incorporate the “special crash pattern” in the adjusted model to be discussed in the next section. Finally, when several years of crash data are available, it is advised that, for crash prediction purposes, the years enter the model as dummy variables. The latter is suggested in order to account for seasonal and time effects. This is further discussed in the next section in which the predictive power of the model is evaluated.

3.2.2. Model Structure and Predictive Ability Evaluation

The ultimate objective of this research is the determination of the predictive ability of the proposed model based on 3-D metrics on safety predictions. The comparison is based on the crash predictions as estimated from the model and the IHSDM. The IHSDM predicts crashes per year for a given roadway through the Empirical Bayes model. To account for the differences that arise throughout the years such as the number of crashes and AADT, IHSDM needs to develop a separate prediction for each year and this approach was considered and applied in the suggested model to obtain an accurate and fair comparison. It is therefore important to consider this in the model developed here and determine how to best approach it. There are two options for incorporating the “year effect” in this analysis: 1) use a separate model for each year developing predictions one year at a time; and 2) insert dummy variables for years to account for the different AADT for each year. The following presents this analysis and the determination of which approach is more appropriate. It should be also noted that there is no concern whether the dummy variables are statistically significant or not at this point; their purpose is to simply increase the predictive ability of the model by accounting for the yearly variation of AADT and random effects in general.

The evaluation will be accomplished by creating training data, i.e., assuming that a certain year is not included in the dataset, running the analysis, and then predicting the crashes of that year and reporting the residuals. For example, the way in which the predictive power of the model will be evaluated for year 2017 is as follows. Suppose that crash data are available for years 2004-2016 and that the intention is to predict the crashes for year 2017. The predictive model will include the explanatory variables of the IM, i.e. AADT, GC, GC

2, GC

3, MC, MC

2, and GC*MC. For the use of the dummy variable approach, in addition to the explanatory variables, a number of dummy variables equal to the number of years of crashes minus 1 is used. In this case, for the 13 years of available date (2004-2016 period) 12 (=13-1) dummy variables will be used. The crash predictions for year 2017 will be calculated in the following form (Equation 5):

or finally:

The term “-LN(13)” is present in Equation 6 in order to convert the prediction model on a per year basis since the model is based on 13 years of data. In statistical terminology, especially for GLM, this “-LN(13)” term is the so-called offset in the Negative Binomial Regression (Hardin and Hilbe 2012). The crash predictions for any other year will be calculated with the same exact procedure and rationale. The model structure is evaluated using both approaches, with and without dummy variables, and then comparing the predictions to the actual number of crashes. The approach that results in a prediction closer to the actual crashes would be the one to be used.

In

Table 4.8 the crashes prediction breakdown per year and roadway segment is presented in which there are three columns for each roadway segment: 1) Actual Crashes (AC), 2) Predicted Crashes Without the Utilization of the Dummy Variables Approach (W/O), and 3) Predicted Crashes With the Utilization of the Dummy Variables Approach (W/). In addition,

Table 4.9 presents the errors/residuals corresponding to the models with and without the dummy variable approach, as well as the corresponding Crash Improvement (CI) that has been achieved with the dummy variable approach.

Table 4. 7.

Crash Predictions Estimates.

Table 4. 7.

Crash Predictions Estimates.

| |

KY420-1 |

KY420-2 |

KY152-1 |

KY152-2 |

KY152-3 |

US68-1 |

US68-2 |

| Year |

AC |

W/O |

W/ |

AC |

W/O |

W/ |

AC |

W/O |

W/ |

AC |

W/O |

W/ |

A |

W/O |

W/ |

AC |

W/O |

W/ |

AC |

W/O |

W/ |

| 2004 |

29 |

12 |

21 |

3 |

5 |

2 |

12 |

34 |

12 |

2 |

11 |

4 |

10 |

7 |

6 |

9 |

13 |

12 |

34 |

38 |

40 |

| 2005 |

15 |

12 |

15 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

8 |

34 |

9 |

4 |

11 |

3 |

8 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

12 |

9 |

30 |

38 |

30 |

| 2006 |

20 |

11 |

18 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

9 |

33 |

10 |

2 |

10 |

4 |

4 |

7 |

5 |

17 |

13 |

10 |

29 |

38 |

34 |

| 2007 |

21 |

11 |

14 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

31 |

8 |

1 |

10 |

3 |

3 |

7 |

4 |

6 |

13 |

8 |

30 |

38 |

27 |

| 2008 |

26 |

11 |

24 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

13 |

31 |

14 |

2 |

10 |

5 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

50 |

37 |

47 |

| 2009 |

33 |

11 |

23 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

8 |

31 |

13 |

6 |

10 |

5 |

5 |

7 |

7 |

17 |

13 |

14 |

38 |

37 |

45 |

| 2010 |

34 |

10 |

32 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

25 |

31 |

18 |

7 |

10 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

10 |

22 |

12 |

19 |

51 |

38 |

63 |

| 2011 |

30 |

10 |

35 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

21 |

30 |

20 |

8 |

9 |

7 |

8 |

7 |

10 |

26 |

12 |

20 |

72 |

38 |

68 |

| 2012 |

48 |

10 |

35 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

17 |

28 |

20 |

5 |

8 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

10 |

16 |

12 |

21 |

71 |

39 |

69 |

| 2013 |

28 |

11 |

29 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

10 |

26 |

16 |

10 |

8 |

6 |

4 |

7 |

8 |

13 |

12 |

17 |

68 |

39 |

56 |

| 2014 |

5 |

12 |

19 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

13 |

24 |

11 |

1 |

7 |

4 |

10 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

12 |

11 |

53 |

39 |

37 |

| 2015 |

12 |

13 |

23 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

17 |

23 |

13 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

18 |

12 |

13 |

42 |

37 |

45 |

| 2016 |

12 |

14 |

22 |

3 |

5 |

2 |

21 |

22 |

12 |

8 |

6 |

4 |

13 |

6 |

7 |

9 |

12 |

13 |

33 |

37 |

43 |

| 2017 |

12 |

14 |

15 |

4 |

5 |

2 |

7 |

22 |

9 |

5 |

6 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

12 |

12 |

9 |

24 |

36 |

30 |

| Total |

325 |

162 |

327 |

36 |

56 |

36 |

184 |

399 |

185 |

66 |

120 |

66 |

97 |

97 |

97 |

190 |

172 |

190 |

625 |

530 |

634 |

| LEGEND |

| Notation |

Description |

| AC |

Actual Crashes |

| W/O |

Predicted Crashes Without the Utilization of the Dummy Variables Approach |

| W/ |

Predicted Crashes With the Utilization of the Dummy Variables Approach |

Table 4. 8.

Error Comparison in Crash Prediction.

Table 4. 8.

Error Comparison in Crash Prediction.

| |

KY420-1 |

KY420-2 |

KY152-1 |

KY152-2 |

KY152-3 |

US68-1 |

US68-2 |

| |

AC-W/O |

AC-W/ |

AC-W/O |

AC-W/ |

AC-W/O |

AC-W/ |

AC-W/O |

AC-W/ |

AC-W/O |

AC-W/ |

AC-W/O |

AC-W/ |

AC-W/O |

AC-W/ |

| 2004 |

17 |

8 |

-2 |

1 |

-22 |

0 |

-9 |

-2 |

3 |

4 |

-4 |

-3 |

-4 |

-6 |

| 2005 |

3 |

0 |

-4 |

-2 |

-26 |

-1 |

-7 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

-6 |

-3 |

-8 |

0 |

| 2006 |

9 |

2 |

-2 |

0 |

-24 |

-1 |

-8 |

-2 |

-3 |

-1 |

4 |

7 |

-9 |

-5 |

| 2007 |

10 |

7 |

-1 |

1 |

-28 |

-5 |

-9 |

-2 |

-4 |

-1 |

-7 |

-2 |

-8 |

3 |

| 2008 |

15 |

2 |

-1 |

0 |

-18 |

-1 |

-8 |

-3 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

-2 |

13 |

3 |

| 2009 |

22 |

10 |

-1 |

0 |

-23 |

-5 |

-4 |

1 |

-2 |

-2 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

-7 |

| 2010 |

24 |

2 |

0 |

-1 |

-6 |

7 |

-3 |

0 |

0 |

-3 |

10 |

3 |

13 |

-12 |

| 2011 |

20 |

-5 |

-3 |

-4 |

-9 |

1 |

-1 |

1 |

1 |

-2 |

14 |

6 |

34 |

4 |

| 2012 |

38 |

13 |

4 |

3 |

-11 |

-3 |

-3 |

-2 |

-2 |

-5 |

4 |

-5 |

32 |

2 |

| 2013 |

17 |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

-16 |

-6 |

2 |

4 |

-3 |

-4 |

1 |

-4 |

29 |

12 |

| 2014 |

-7 |

-14 |

-4 |

-2 |

-11 |

2 |

-6 |

-3 |

3 |

4 |

-5 |

-4 |

14 |

16 |

| 2015 |

-1 |

-11 |

-2 |

0 |

-6 |

4 |

-1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

-3 |

| 2016 |

-2 |

-10 |

-2 |

1 |

-1 |

9 |

2 |

4 |

7 |

6 |

-3 |

-4 |

-4 |

-10 |

| 2017 |

-2 |

-3 |

-1 |

2 |

-15 |

-2 |

-1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

-12 |

-6 |

| Total |

163 |

-2 |

-20 |

0 |

-215 |

-1 |

-54 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

18 |

0 |

95 |

-9 |

| CI |

161 |

20 |

214 |

54 |

0 |

18 |

86 |

| LEGEND |

| Notation |

Description |

| AC |

Actual Crashes |

| W/O |

Predicted Crashes Without the Utilization of the Dummy Variables Approach |

| W/ |

Predicted Crashes With the Utilization of the Dummy Variables Approach |

| CI |

Crash Prediction Improvement Per Roadway Segment with the Dummy Variables Approach |

The summary row in

Table 4.9 denotes that the inclusion of dummy variables results in predictions that are closer to the actual crashes than the without using them. Moreover, the insertion of dummy variables is preferred, in general, over the creation of separate models for each year because it is statistically more appropriate: the Bonferroni correction can be applied in a much more robust manner, since the familywise error is explicitly defined, and small sample size issues, which are in general present in crash datasets, are alleviated with the dummy variable approach.

Therefore, at this point it is decided to utilize the dummy variable approach in order to compare the crash predictions of the suggested model with those derived from the IHSDM. The comparison follows in the next section.

The next step involves the evaluation of the assumptions of the model developed, since every regression model is based on some statistical, mostly distribution related, assumptions. This applies in this case as well, and therefore these assumptions must be checked in order to validate the reliability of the model. In practical/applied terms, failure in assessing these assumptions would mean that the coefficients of the model are not reliable, i.e., the coefficients are inflated or deflated compared to the true parameters. Moreover, the defined confidence levels of the coefficients may not hold true, a fact that means that the exported p-values from the models may be highly distorted, which, in turn, means that although the model may be considered statistically significant based on the explanatory variables p-values, it may in fact not be statistically significant since the results may just be artificially in favor of rejecting the null hypotheses.

There are many techniques that have been suggested for the assumption assessment of regression models, but especially in the case of GLMs, this matter remains an open research problem. Therefore, for the scope of this research, the basic assumptions assessment techniques will be checked for which there is a general agreement in terms of their effectiveness and pertinence from the scientific community. More specifically, the assumption assessment was based on two elements: 1) Residuals Analysis, and 2) Influential Points Identification. Both Residential Analysis and Influential Points Identification, via the Cook’s distance concept, are explicitly described in Amiridis, K. (2019). It is noted that the assumption assessment of the final regression model which corresponds to the 100 ft. patch was conducted with success.