1. Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a Gram-positive encapsulated diplococcus and a leading cause of invasive bacterial infections worldwide. It is classically associated with community-acquired pneumonia, meningitis, otitis media, and bacteremia [

1]. CNS involvement most commonly presents as meningitis, while other manifestations such as brain abscess, subdural empyema, or spinal cord infections are exceedingly rare [

2]. Among these, bacterial myelitis is defined as inflammation of the spinal cord resulting from direct infection. It is an infrequent entity, particularly when caused by

S. pneumoniae. The diagnosis of bacterial myelitis is often delayed due to its non-specific clinical presentation and the rarity of the condition, which frequently mimics more common inflammatory or autoimmune etiologies such as multiple sclerosis or idiopathic transverse myelitis [

3].

Most reported cases of bacterial myelitis occur in immunocompromised individuals or in the setting of direct extension from adjacent infected structures (e.g., vertebral osteomyelitis, epidural abscess) or after neurosurgical procedures [

4]. In contrast, spontaneous hematogenous spread leading to isolated pneumococcal myelitis in an otherwise immunocompetent host is an exceptional finding, with only a few cases described in the literature to date [

5,

6].

Reactive arthritis (ReA) is a sterile inflammatory arthritis that typically develops 1 to 4 weeks after a bacterial infection, most commonly involving the gastrointestinal or urogenital tract [

7]. It is considered part of the spondyloarthropathy spectrum and is often associated with

Chlamydia trachomatis,

Salmonella,

Shigella,

Yersinia, and

Campylobacter species [

8]. Although

Streptococcus pneumoniae is not commonly implicated as a trigger of ReA, rare reports suggest that pneumococcal infections may act as a stimulus for aberrant immune responses in genetically predisposed individuals, even in the absence of joint disease [

9].

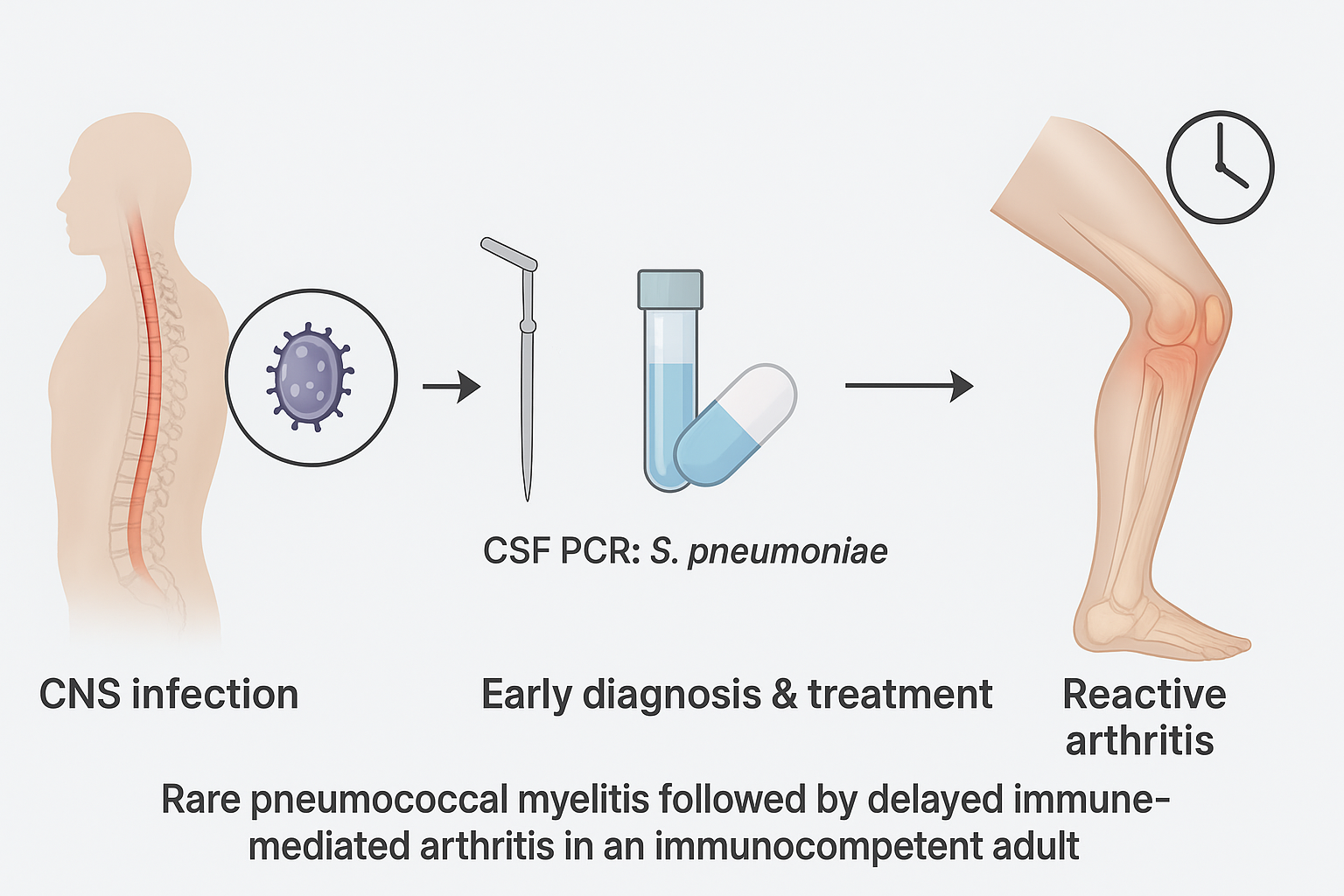

The co-occurrence of bacterial myelitis and reactive arthritis in the same patient, both potentially attributable to S. pneumoniae, has not been previously documented in the medical literature. This case highlights a unique and diagnostically challenging clinical scenario, underscoring the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis in patients presenting with acute neurological deficits and systemic symptoms, even in the absence of classical risk factors for CNS infection or reactive arthritis.

2. Case Presentation

A 68-year-old man with a medical history of arterial hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and multiple lumbar disc herniations presented to the emergency department with a 4-day history of high-grade fever (maximum temperature: 40 °C), urinary retention, and diffuse pain localised to the lower abdomen and both lower limbs. He denied recent trauma, surgeries, or infectious exposures, and was not on immunosuppressive therapy.

On physical examination, the patient appeared febrile but hemodynamically stable. Neurological assessment revealed significant motor impairment of the lower limbs, with the inability to maintain leg elevation for more than 10 seconds. Deep tendon reflexes were absent in both lower limbs. Sensory examination was non-significant, with no deficits in superficial or deep modalities. Plantar reflexes were flexor bilaterally, and no signs of cranial nerve involvement or meningeal irritation were present. Bladder catheterisation confirmed urinary retention with a residual volume of>500 mL.

Laboratory investigations demonstrated neutrophilic leukocytosis (WBC 22550 mm³, 80% neutrophils), elevated C-reactive protein (CRP 12.8 mg/dL), and markedly increased procalcitonin (26 ng/mL), indicating a severe systemic bacterial infection. Liver and renal function tests were within normal limits (

Table 1).

Given the combination of neurological findings and systemic inflammatory markers, infectious myelitis was suspected. Lumbar puncture revealed CSF with 144 white blood cells/mm³ (predominantly polymorphonuclear leukocytes), elevated protein (915 mg/dL), and normal glucose (60 mg/dL; serum glucose: 102 mg/dL). Gram stain was negative, but multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on CSF tested positive for

Streptococcus pneumoniae. Blood cultures remained negative (

Table 2).

High-dose intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 12 hours) was initiated immediately, with clinical and laboratory improvement. Due to technical limitations, spinal MRI with gadolinium was performed four days after starting antibiotics. The scan showed non-specific T2 hyperintensity in the thoracic spinal cord, without contrast enhancement or evidence of abscess or vertebral involvement, and was considered non-diagnostic.

After 14 days of hospitalisation, the patient was discharged with partial recovery of motor function and referred to a neurorehabilitation program.

Two weeks later, he developed fever (38.5 °C), right ankle pain, swelling, erythema, and limited joint mobility. Ultrasound revealed intra- and periarticular effusion. Arthrocentesis yielded turbid synovial fluid with >20,000 cells/mm³, negative for crystals, Gram stain, and cultures. Blood cultures and autoimmune tests were also negative. A diagnosis of reactive arthritis was made based on clinical context and exclusion of septic arthritis. Treatment with oral prednisone (0.5 mg/kg/day for 21 days) led to the complete resolution of symptoms. At follow-up, the patient remained afebrile, with no recurrence of joint or neurologic symptoms, and continued rehabilitation, showing progressive improvement in mobility.

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Myelitis refers to inflammation of the spinal cord and encompasses a broad range of infectious, autoimmune, paraneoplastic, and idiopathic etiologies. Clinically, it typically presents with varying degrees of motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunction below the level of spinal cord involvement. Hallmark symptoms include limb weakness, sensory level disturbances, sphincter dysfunction (urinary retention or incontinence), and gait abnormalities. The pattern of neurological deficits depends on the anatomical location and extent of the lesion along the spinal cord [

10].

The aetiology of myelitis can be classified into infectious (viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic), post-infectious/parainfectious (such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis), autoimmune (e.g., neuromyelitis optica, multiple sclerosis), and idiopathic causes. Viral pathogens (e.g., Herpes Simplex Virus, Varicella Zoster Virus, enteroviruses) are the most common infectious causes of acute transverse myelitis. In contrast, bacterial involvement is relatively rare and often secondary to hematogenous dissemination or local extension from adjacent structures [

11].

The pathogenesis of bacterial myelitis typically involves invasion of the spinal cord parenchyma via bloodstream seeding or contiguous spread, leading to direct tissue damage, inflammation, and oedema. Inflammatory cytokines and bacterial toxins exacerbate tissue injury and can result in rapid neurological deterioration if not promptly treated [

12].

Streptococcus pneumoniae, a leading cause of community-acquired meningitis and bacteremia, is an extremely rare agent of isolated spinal cord infection. Only a handful of cases of pneumococcal myelitis have been described in the literature, often in immunocompromised hosts or patients with a history of meningeal or sinus infections [

13]. In our patient, no obvious local or systemic source of pneumococcal infection was identified, suggesting hematogenous dissemination with preferential tropism to spinal cord structures.

Our patient exhibited a classic subacute presentation of myelitis: urinary retention, fever, and bilateral lower limb weakness with areflexia, yet preserved sensation and absent pyramidal signs. The absence of the sensory level and Babinski sign complicated the early localisation. However, the urinary retention and bilateral lower limb involvement were suggestive of involvement of the conus medullaris or lower thoracic spinal cord.

Laboratory investigations revealed a marked systemic inflammatory response with elevated CRP (12.8 mg/dL) and very high procalcitonin levels (26 ng/mL), strongly suggestive of bacterial infection [

14]. CSF analysis showed neutrophilic pleocytosis, increased protein content, and normal glucose—a profile consistent with bacterial meningo-myelitis. CSF culture was negative, likely due to early antibiotic administration; however, PCR testing confirmed

S. pneumoniae infection, demonstrating the added diagnostic value of molecular testing in partially treated CNS infections [

15].

Spinal MRI was performed four days after antibiotic initiation and did not reveal active enhancement or oedema, consistent with the known reduction in imaging sensitivity following treatment [

16]. Despite this, the clinical picture and laboratory findings were sufficient for diagnosis.

After antibiotic treatment and partial neurological recovery, the patient developed acute monoarthritis of the right ankle with localised oedema and erythema, but without fever or systemic signs of infection. Synovial fluid analysis demonstrated sterile inflammation, with negative bacterial culture. In the context of a recent pneumococcal infection and no alternative cause, this was consistent with ReA.

ReA is a sterile inflammatory arthritis triggered by a distant infection, classically involving the urogenital or gastrointestinal tract. However, respiratory infections—including those caused by

Streptococcus pneumoniae—have also been implicated, though infrequently [

17]. The underlying immunopathology of ReA involves cross-reactivity between microbial antigens and host tissues, molecular mimicry, and the deposition of immune complexes. HLA-B27 positivity is a well-known risk factor, although our patient tested negative, reinforcing that ReA can occur outside of the spondyloarthropathy spectrum [

18].

Corticosteroid therapy (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/day) led to complete clinical remission of the arthritis, supporting its immune-mediated origin. No recurrence of symptoms was observed during follow-up.

This case provides multiple key insights:

Myelitis should be considered in patients with febrile paraparesis or urinary retention, especially when imaging or clinical examination is inconclusive.

Pneumococcal myelitis is an infrequent entity, but should be included in the differential diagnosis of acute spinal cord dysfunction

PCR testing of CSF is indispensable for identifying bacterial pathogens in patients with negative cultures, especially those who have been pretreated with antibiotics.

MRI findings can be non-specific, particularly when performed after the initiation of therapy, highlighting the importance of early imaging and a strong clinical suspicion.

Reactive arthritis can follow CNS bacterial infections, including pneumococcal myelitis, and should be considered in cases of sterile monoarthritis occurring after convalescence.

Prompt diagnosis and multidisciplinary management involving neurologists, infectious disease specialists, and rehabilitation professionals are essential for improving both functional and systemic outcomes.

List of Abbreviations

CNS: central nervous system

CSF: cerebrospinal fluid

ReA: reactive arthritis

PCR: polymerase chain reaction

CRP: C-reactive protein

Authors' contributions

RLN, SM, FF, GT, LDG, GMAR, CDM: case report concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. AP, FC: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Availability of data and materials

not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- van de Beek D, Brouwer MC, Thwaites GE, Tunkel AR. Advances in treatment of bacterial meningitis. Lancet. 2012;380(9854):1693–702.

- Muthukumar N, Rajagopal V, Dhandapani S. Pneumococcal spinal infections: rare presentations and diagnostic pitfalls. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2015;6(3):395–398.

- West, TW. Transverse myelitis—a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med. 2013;16(88):167–177.

- Berntsson SG, Wiberg K, Hesselgard K, et al. Bacterial spinal cord infections in adults: a 10-year nationwide retrospective study in Sweden. Eur Spine J. 2022;31(3):706–714.

- Audebert HJ, Schenkel J, Ziemann U, et al. Transverse myelitis associated with pneumococcal sepsis. J Neurol. 2001;248(10):939–940.

- Totsuka T, Ishizaka S, Shimizu T, et al. Acute transverse myelitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in a healthy adult. Intern Med. 2016;55(12):1619–1622.

- Townes, JM. Reactive arthritis after enteric infections in the United States: the problem of definition. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(2):247–254.

- Hannu, T. Reactive arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(3):347–357.

- Galindo-Fernandez C, de la Iglesia-Fernandez M, et al. Unusual presentation of pneumococcal reactive arthritis: a case report and literature review. Reumatol Clin. 2016;12(4):225–227.

- Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group. Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology. 2002;59(4):499–505. [CrossRef]

- Beh SC, et al. Infectious myelitis. Neurol Clin. 2013;31(1):225–248. [CrossRef]

- Koul R, et al. Spinal cord involvement in bacterial infections. J Child Neurol. 2004;19(3):179–183. [CrossRef]

- Thömke F, et al. Spinal cord involvement in bacterial meningitis. Eur Neurol. 2001;46(1):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Meisner M. Update on procalcitonin measurements. Ann Lab Med. 2014;34(4):263–273. [CrossRef]

- Boers SA, et al. Bacterial meningitis: molecular diagnostics and resistance detection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020;33(3):241–247. [CrossRef]

- Young NP, et al. Neuroimaging in infectious and inflammatory disorders of the spine. Semin Roentgenol. 2014;49(1):90–104. [CrossRef]

- Ozgul A, et al. Reactive arthritis associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(1):107–110. [CrossRef]

- Colmegna I, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR. HLA-B27-associated reactive arthritis: pathogenetic and clinical considerations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(2):348–369. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Laboratory findings at admission.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings at admission.

| White blood cells |

22550 mm3

|

| Neutrophils |

80% |

| Platelets |

233000 uL |

| Haemoglobin |

11.4 g/dL |

| C-reactive protein |

12.8 mg/dL |

| Procalcitonin |

26 ng/mL |

| Creatinine/clearance |

0.95 mg/dL / 72 ml/min |

| Sodium/ Potassium |

133/4.28 mEq/L |

| GOT/AST |

19 U/L |

| GPT/ALT |

30 U/L |

| Total bilirubin |

1.06 mg/dL |

| INR |

1.03 |

Table 2.

CSF findings at admission.

Table 2.

CSF findings at admission.

| WBC |

144 mmc |

| Polymorphonuclear leukocytes |

121 mmc |

| Proteins |

915 mg/dL |

| Glucose |

60 mg/dL |

| Albumin |

480.6 mg/dL |

| Polymerase chain reaction (Biofire FILMARRAY) |

Positive for S. pneumoniae |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).