1. Introduction

Arterial hypertension (H) remains the most common disease [

1,

2]. H causes damage to a number of target organs (heart, brain, kidneys, and blood vessels), which leads to significant increase in cardiovascular and overall mortality [

1,

2,

3]. While, unfortunately, the coverage of treatment and the effectiveness of the treatment of this disease remains insufficient.

The results of most studies indicate that less than half of patients achieve target levels of blood pressure (BP) [

4]. According to a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies involving 104 million people in 200 countries and territories, the average rate of control of H was 23% for women and 18% for men. Moreover, the effectiveness of antihypertensive therapy is especially low in low- and middle-income countries [

5].

Achieving target BP is most difficult in cases of association of H with a number of metabolic diseases, the most common of which is abdominal obesity (AO) [

6]. When H is combined with AO, there is a more rapid and pronounced development of such pathological changes as activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, atherogenic dyslipidemia (DLP), insulin resistance (IR), hypeuricemia (HUE) and subclinical inflammation [

6,

7,

8,

9].

This contributes to the formation of severe and often resistant H, the accelerated development of target organ damage and arteriosclerosis, which significantly increases the incidence of cardiovascular and renal complications [

1,

4,

6,

7,

10]. Therefore, in patients with H and O, especially those with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe H, it is necessary to start intensive therapy early with three antihypertensive agents with complementary mechanisms of action, primarily in the form of fixed-dose combinations or single-pill combinations (SPCs) [

11,

12,

13,

14]. One of the pathogenetically justified combination therapy regimens is a three-drug SPC of the following three drugs: perindopril (P) (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), indapamide (I) (thiazide-like diuretic (T-LD) and amlodipine (A) (long-acting dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (CCB) [

15,

16]. To note, the expediency of using SPC of these drugs in uncontrolled H has already been shown in a number of studies [

16,

17,

18]. However, the long-term effectiveness of this SPC, its effect on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) parameters, target organs and metabolic disturbances, as well as its advantages over the free combination (FC) (non-fixed combination) of these drugs in comorbid patients with H and O require further study. The aim of the study was to evaluate the advantages of SPC (P/I/A) in comparison with their FC in achieving effective control of H for a long time in patients with O.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population and Study Design

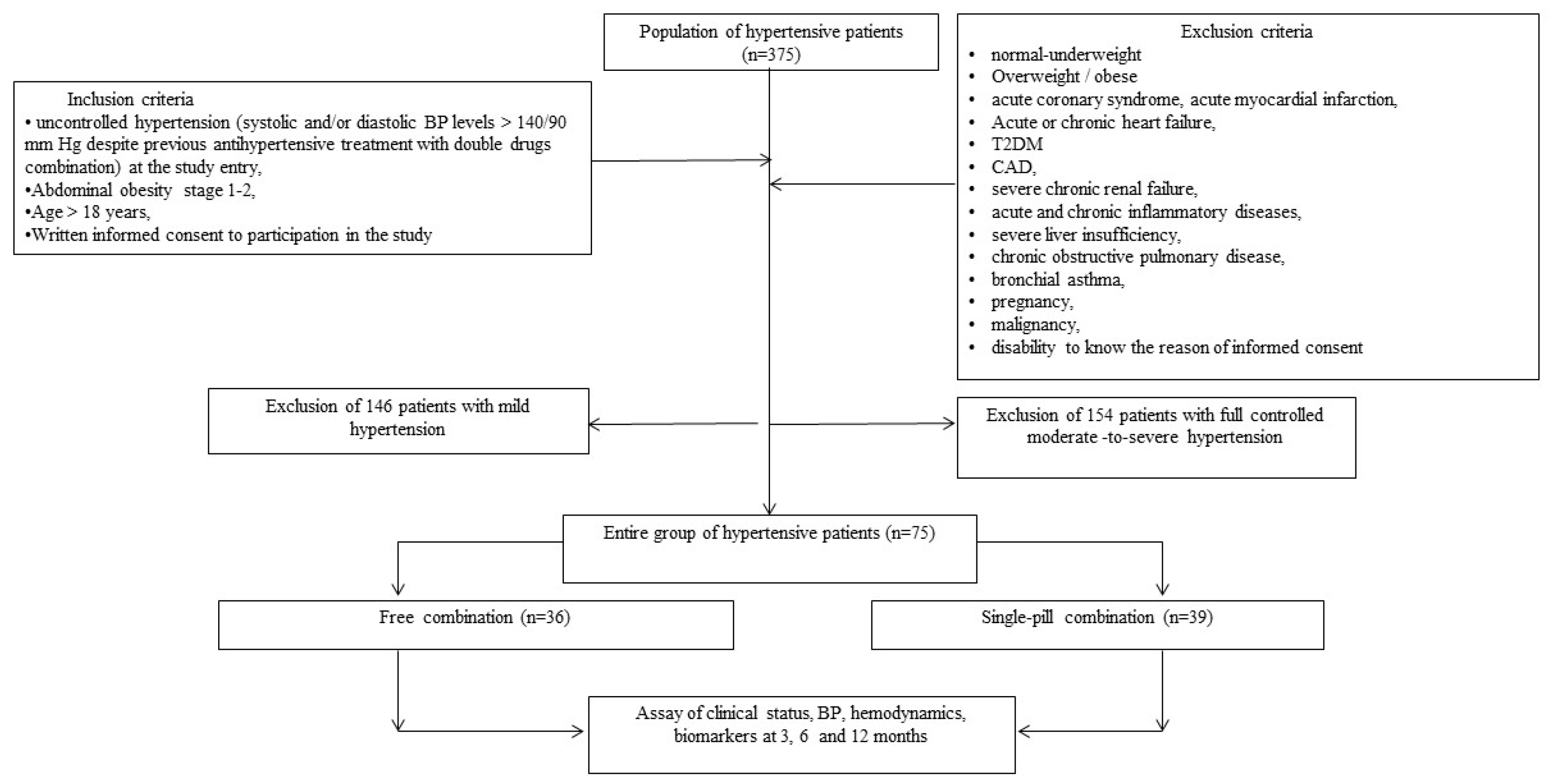

We selected from our database of 375 patients with arterial hypertension, seventy five individuals with uncontrolled grade 2-3 H (moderate/severe H) and stage 1-2 O (45 men/30 women, age 48 -66 years) were selected for 12-month study. The general scheme of the study, including inclusion and non-inclusion criteria, is shown in the

Figure 1.

Among the examined patients, 45 received a FC of following antihypertensive drugs: P, I and A, and 36 - SPC of these drugs. Patients were examined at the beginning and after 3, 6 and 12 months of treatment.

The study presented is open-label, and randomized, parallel-group and controlled. In accordance with the purpose among 75 included patients, two groups were distinguished: group 1–36 patients, who received a FC of three drugs: P, I and A orally once a day (non-fasting in the morning) in daily doses: 4-8 mg; 1.25-2.5 mg and 5-10 mg, respectively; group 2–39 patients, who received a SPC (P/I/A) in the following doses: 4 mg/1.25mg/5 mg; 4 mg/1.25mg/10 mg; 8 mg/2.5 mg/5 mg and 8 mg/2.5mg/10 mg in the same manner.

Prior to inclusion in the present study, all patients received two (80%) - and three (20%) -component FC of antihypertensive drugs: two-component FC (ACEI/angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB)+ thiazide diuretic (TD)/T-LD (47%), ACEI/ARB+ CCB (all-long-acting dihydropyridine) (24%) and beta-blocker (BB)+T-LD (9%)); three-component FC (ACEI/ARB+CCD (all-long-acting dihydropyridine)+TD. At the same time, no one has reached target BP levels prior to enrollment in the study. It should be especially noted that both groups of patients were comparable in terms of the nature of therapy before the start of this study.

Before the start of the study and after 3, 6 and 12 months, a general clinical examination was performed, which included the office BP measurement; ABMP was additionally performed before the start of the study and after 6 and 12 months. For target levels of BP after treatment were taken levels of systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) <140/90 mm Hg.

Patients with DLP were prescribed atorvastatin (orally once a day in daily doses from 20 to 40 mg). Target blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were considered: in very-high risk patients <1.4 mmol/L and in high risk <1.8 mmol/L [

19]. In addition, all patients were recommended life-style correction.

2.2. Diagnosis of Hypertension and Definition of Uncontrolled Hypertension

Diagnosis of the grade of H was carried out in accordance with recommendations 2018 [

1]. Criteria for the diagnosis of uncontrolled H: SBP and/ or DBP >140/90 mm Hg despite previous antihypertensive treatment with double drugs combination [

1].

2.3. Diagnosis of Dyslipidemia

Criteria for the diagnosis of DLP: total cholesterol (TC) level> 5.2 mmol/L, and/or LDL-C level> 3.0 mmol/L, and/or triglyceride (TG) level>1.7 mmol/L, and /or lipid-lowering drugs treatment (in accordance with recommendations 2016 [

1]).

2.4. Diagnosis of Obesity

Criteria for the diagnosis of O: increase in body mass index (BMI) (≥30 kg/m2) and increase in waist circumference (WC): for men ≥ 90 cm, for women ≥ 80 cm [

21].

2.5. Diagnosis of Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was diagnosed in the presence of at least three of the following components: WC ≥ 90 cm in men or ≥ 80 cm in women; high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <1.03 mmol/L in men or <1.3 mmol/L in women; TG levels ≥ 1.7 mmol/L; BP ≥130/85 mmHg or antihypertensive drugs treatment and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L [

22].

2.6. Diagnosis of Hyperuricemia

Criteria for the diagnosis of hypeuricemia: serum uric acid >360 mmol/L [

23].

2.7. Assessment of Anthropometric Parameters

In the work, the following anthropometric parameters were evaluated: weight, height, body mass, BMI, WC, and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) using standard methods [

24]. OMRON (Japan) scales and stadiometer were used to measure weight and height.

2.8. Treatment Adherence Assessment

Adherent to treatment were considered patients who fully adhered to the recommended treatment regimen at various stage of the study (after 3 months, 6 months and 12 months).

2.9. BP Measurement

A sphygmomanometer (Microlife BP AG 1-10, Hungary) was used to measure office BP.

2.10. Conducting an ECG Study

Three-channel FX-326U ECG recorder (Fukuda, Japan) was used to record the ECG in 12 standard lead.

2.11. Assessment of ABPM Parameters

AVRM-02/0 machine (Meditech, Hungary) was used to carry out the ABPM. The generally accepted parameters of ABPM were analyzed in accordance with the modern protocol [

25].

2.12. Echocardiography

Diagnostic ultrasound complex SSD 280 LS (Aloka, Japan) was used to carry out echocardiography in M- and B-modes with a 2.5 MHz phased probe. Registration and analysis of standard echocardiographic parameters were carried out in accordance with modern recommendations [

1]).

2.13. Ultrasound Examination of Common Carotid Artery (CCA)

Ultrasound scanner (LOGIQ-5, Japan) with a 7.5 MHz linear array probe and color flow mapping was used to carry out B-mode CCA ultrasound examination and to assess the carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) [

26]. An increase in the IMT or the presence of atheromatous plaques was recorded based on the criteria given in current guidelines [ 1].

2.14. Assessment of Glomerular Filtration Rate and Insulin Resistance

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated [

27]. IR was calculated using the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR) [

28].

2.15. Blood Sampling and Biomarkers Evaluation

The study assessed a number of laboratory parameters and biomarkers (plasma glucose, serum urea, creatinine, uric acid, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels) using modern methods. Collection, processing and storage of blood samples were carried out in accordance with standard requirements in the laboratory of immune-chemical and molecular-genetic researches of GI “L.T. Malaya Therapy National Institute of the NAMS of Ukraine”.

2.16. Generative Artificial Intelligence Declaration

All authors confirm that generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has not been used in this paper (e.g., to generate text, data, or graphics, or to assist in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation).

2.17. Statistical Processing

Statistical processing of the results was carried out using the software SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative and qualitative variables were used in the statistical analysis. Qualitative data were presented as percentages; quantitative - in the form of mean (M) and standard deviation (±SD) or 95% confidence interval (CI). The Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare quantitative indicators. The frequency of signs in groups was compared using Pearson’s χ2 test and Fisher’s F-test. The post-hoc ANOVA method with Duncan’s test was used to study the influence of factors. The critical level of significance for testing statistical hypotheses in the study was equal to 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Clinical Characteristics

Clinical features of patients before the start of the study The basic characteristics of patient of both treatment groups (FC group (group 1) and SPC group (group 2)) are given in the

Table 1.

It was revealed that both groups of patients were characterized by a high frequency of such metabolic disorders as MetS, DLP, IR, as well as such asymptomatic hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD) as LVH and increased carotid IMT and/or atheromatous plaques The frequency of other metabolic disorders (fasting hyperglycemia (FHG) and HUE, and HMOD (increased pulse BP (PBP) and CKD stage IIIa) was less. When comparing patients of the group 1 with patients of the group 2, no significant differences were found. Groups 1 and 2 did not significant differ in the frequency of H of 2 and 3 grades, O of 1 and 2 stages (

Table 1), as well as in the in age (54±13 years and 59±14 years, respectively (p>0.05) and sex (61% and 59% of men, respectively (p>0.05) and 39% and 41% of women, respectively (p>0.05).

3.2. Antihypertensive Efficacy of SPC of P/I/A in Comparison with FC of These Agents Among Enrolled Patients According to Changes in Office BP

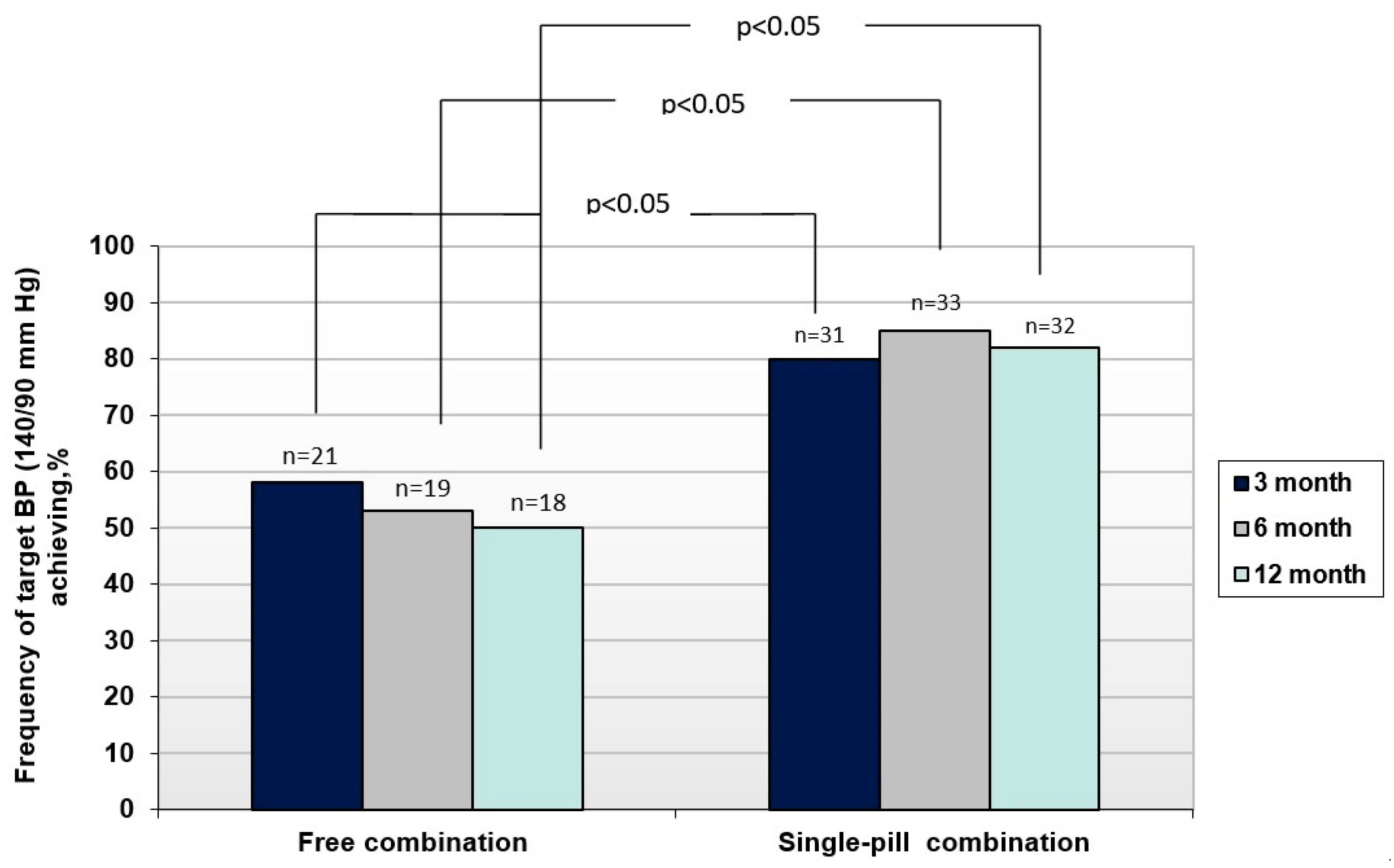

A significantly higher antihypertensive efficacy of SPC compared to FC was established. This was evidenced by a significantly higher frequency of achieving BP control in SPC group compared to a free one. Significantly higher frequency of achievement of target BP level when using a SPC of P/I/A in comparison with FC in the examined patients was found already 3 months after the start of treatment (80% versus 58%, p<0.05) (

Figure 2). The BP target levels at 3, 6, and 12 months were achieved in significantly more numbers of patients of SPC group than in FC group (p<0.05 for all cases). The high efficiency of SPC was maintained throughout the study and target BP level in these group of patients was achieved after 6 months in 85% of the patients and after 12 months- in 82%. At the same time, with prolonged use of FC, the frequency of BP control even decreased: after 6 months in 53% of patients (p<0.05), and after 12 months - in 50% of patients (p<0.05)

3.3. Impact of SPC and FC of P/I/A on ABPM Parameters in Both Patient Groups

Table 2 shows changes in ABPM parameters in hypertensive patients with AO throughout the study. First of all, it should be pointed out that the compared groups of patients before the start of therapy did not differ significantly depending on the analyzed ABPM parameters.

Unfortunately, the use of FC did not lead to significant positive dynamics of the ABPM indicators analyzed in the work among the surveyed patients even after 12 months. At the same time, after 12 months of treatment with the use SPC, there was a significant decrease in the average daily, average day-time and night-time SBP and DBP in patients with H and O. These changes were accompanied, on the one hand, by a significant decrease in time-index 24-hour SBP/ DBP and in average daily SBP/DBP variability, and, on the other hand, by a significant increase in the degree of night-time SBP/DBP reduction. That is, SPC, with its long-term use, contributes to the normalization of daily BP profile as a whole as opposed to the FC.

3.4. Adherence to SPC of P/I/A Versus FC of These Antihypertensive Agents Among Enrolled Patients

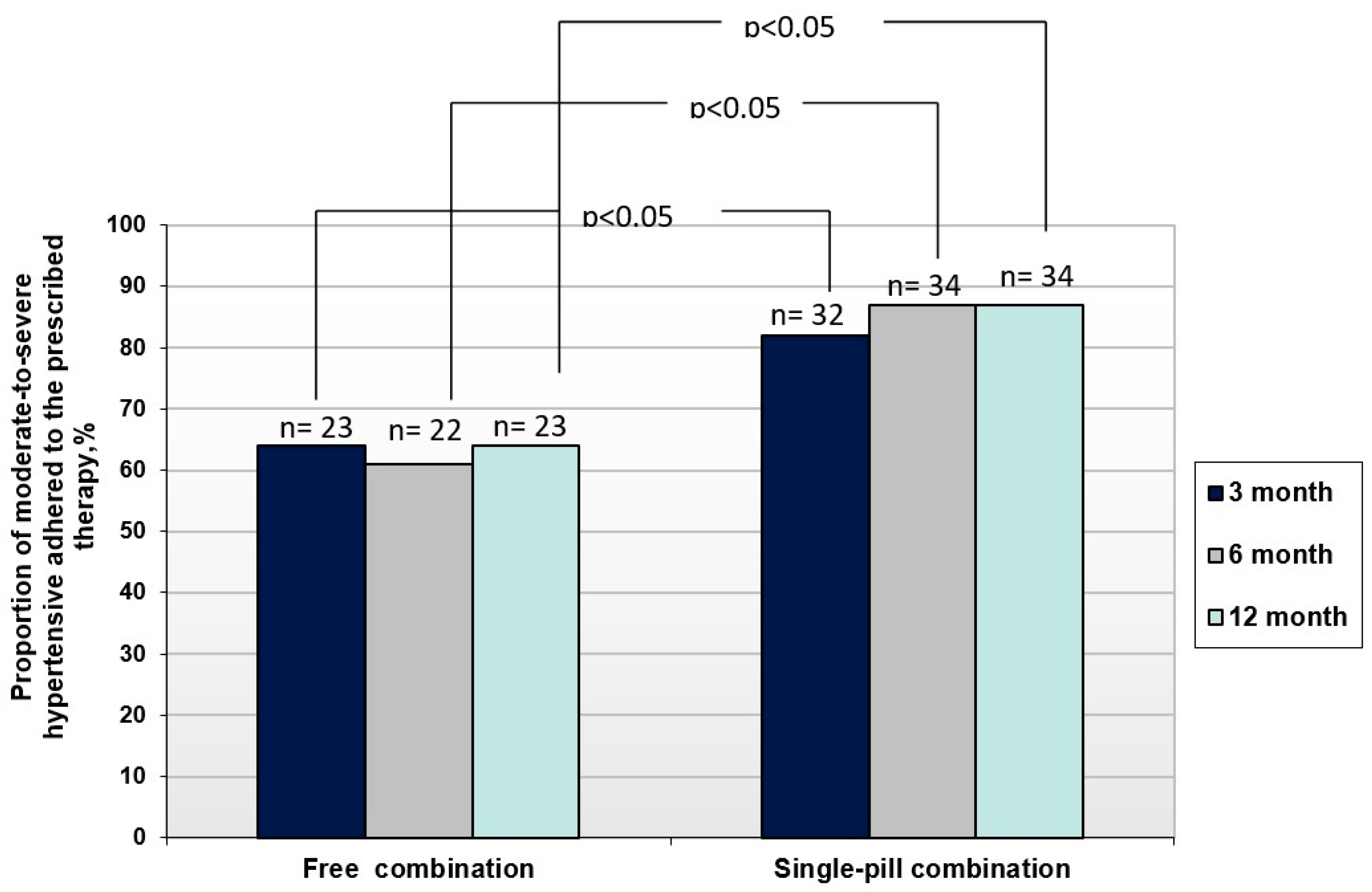

Significant differences in the antihypertensive efficacy of SPC and FC of P/I/A found in the work were also associated with significant differences in adherence to these therapy options in the compared groups of patients. Thus, in the SPC group of patients, adherence to therapy throughout the entire observation period was significantly higher (p<0.05), than in FC group: 82% versus 64%, 87% versus 61% and 87% versus 64% (after 3,6 and 12 months, respectively) (

Figure 3).

The number of adherent patients was significantly higher in SPC group than in FC (p<0.05 for all cases).

3.5. The Frequency of Using Different Doses of P/I/A in the Treatment Arms of Free Combination and Single-Pill Combination

Of particular interest was the analysis of doses of P, I and A when used as SPC and FC at the end of 12 months of treatment. It was found that low P/I/ A doses were used significantly more often in SPC group than in free one (

Table 3). Moreover, 36% of patients who were prescribed FC of P/I/ A did not adhere to these recommendations after 12 months (

Table 3).

Significant differences in the frequency of using different doses of drugs in the form of their SPC and FC were also identified among those patients in whom target BP levels were achieved at the end of 12 months of treatment. It was found that maximum doses of P/ I/A (8 mg / 2.5 mg / 10 mg) were used significantly less frequently to achieve BP control in SPC group (53%) than in FC (89%). And, conversely, in the group of patients who were on SPC, target BP levels were more often achieved using the minimum and average doses of drugs than in the group of patients who were on FC (

Table 4).

3.6. Impact of SPC and FC of P/I/A on Metabolic Parameters in Both Patient Groups

Analysis of changes in metabolic parameters in the examined patients was carried out taking into account the fact that, in addition to antihypertensive therapy, all patients with DLP received atorvastatin at doses of 20-40 mg once a day. The use of atorastatin in SPC group significantly more often (p<0.05) led to the achievement of target LDL-C levels (71%) than in FC group (44%). Adherence to treatment with atorvastatin was also significantly higher (p=0.05) among patients who received SPC of P/I/A than among patients who received FC of these drugs (77% versus 56%). It was found that SPC and FC of P/I/A against the background of average atorvastatin did not significantly affect carbohydrate metabolism (HOMA-IR, fasting glucose levels) and purine metabolism (SUA levels, frequency of HUE) in the dynamics of 12-month therapy. At the same time, in the group of patients who received SPC of P/I/A, a significant decrease in BMI was found (from 34.23±0.33 kg/m2 to 32.44±0.48 kg/m2 (p <0.05) after 12 months of treatment.

3.7. Influence of SPC and FC of P/I/A on Asymptomatic HMOD in Both Patient Groups

A significant decrease in the frequency of elevated PBP was found under the influence of SPC of P/I/A against the background of average atorvastatin doses after 12 months of treatment: from 41% to 21% (p<0.05). In FC group of patients the incidence of elevated PBP did not decrease. At the same time, there were no significant changes in the frequency of other asymptomatic HMOD, such as LVH, carotid IMT >0.9 mm, atheromatous plaques and CKD under the influence of SPC and free combination of P/I/A during the indicated observation period.

3.8. Safety of SPC of P/I/A Versus FC of These Antihypertensive Agents Among Enrolled Patients

Both SPC and FC of P/I/A against the background of average atorvastatin doses for 12 months was well tolerated. Side effects were reported only in a small proportion of patients: drowsiness (in 2 patients (6%) in the FC group), hypotension (in 2 (6%) in the SPC group), nausea and decreased appetite (in 2 patients (6%) in the FC group). However, they were observed for a shot time and the patients continues taking the drugs.

4. Discussion

When discussing the results of the study, it should be emphasized that in order to effectively control H in patients with O, in the overwhelming majority of cases, combined antihypertensive therapy is required due to the uncontrolled nature of H and a high risk of complications [

6,

7,

9]. Along with it, the use of multicomponent therapy in FC reduces adherence to it and its effectiveness [

29,

30,

31]. In addition, if it is necessary to increase the number and doses of drugs used in patients, the so-called “medical inertia, i.e., failure to adequately intensify or up-titrate treatment” may occur, which prevents the achievement of optimal control of H [

32]. In this regard, the most preferred is the use of SPCs, primarily in the form of three-drug SPCs, in patients with H and O [

12,

18,

30].

Three-drug SPC of P, I and A was chosen as the optimal therapy option in the study, which has already shown sufficient efficacy in a number of studies [

16,

17,

18]. However, it remains insufficiently studied: the possibility of maintaining the antihypertensive efficacy of this combination for a long time, its effect on the parameters of the AMBP, on the severity of asymptomatic HMOD and metabolic disorders, and safety in long-term use.

The study showed a significantly higher antihypertensive efficiency of SPC compared with FC in uncontrolled H in combination with O. The frequency of achieving target BP levels when using SPC was significantly higher than when using FC from the very beginning of its use [

31] and remained at the same high level throughout the entire observation period. In addition, SPC, with its long-term use (12 months), normalized the daily BP profile in contrast to FC.

Moreover, in the group of patients treated with SPC, adherence to therapy throughout the entire observation period was significantly higher than in the group of patients treated with FC.

It is important that with the use of SPC, smaller doses were required to achieve BP control than with the use of FC. Also, a significantly smaller number of patients required maximum doses of P, I and A to achieve target BP levels when they were used in the form of SPC compared with FC.

Given the significant frequency of metabolic disorders in these patients, it was important that long-term use of both SPC and FC did not adversely affect lipid, carbohydrate and purine metabolism. Moreover, when atorvastatin was used against the background of SPC, the frequency of LDL-C control was significantly higher than when it was used against the background of FC. In addition, adherence to atorvastatin was also higher in SPC group than in FC group. That is, a more convenient combination of antihypertensive drugs may increase adherence to lipid-lowering therapy and its effectiveness.

Interestingly, at the end of the treatment period, there was a decrease in severity of O in patients who received SPC, in contrast to patients who received FC. It should be noted that patients in both groups received recommendations for lifestyle modification, which included recommendations for weight loss. But, probably, patients who were on SPC turned out to be more adherent to such recommendations.

Of considerable interest was the study of the effect of SPC and FC on asymptomatic HMOD, since over time they have a pronounced progression of asymptomatic HMOD, especially in the absence of sufficient control of H [

1,

7,

9]. It was found that the early and long-term use of the combination of P, I and A in these patients, both in the form of SPC and FC, contributed to the inhibition of the progression of asymptomatic HMOD. Moreover, in patients who received SPC, there was a significant decrease after 12 months of treatment in the frequency of such asymptomatic HMOD as elevated PBP, in contrast to patients who received FC. It was also practically significant that the use of both SPC and FC of P, I and A for 12 months in the vast majority of patients was not accompanied by side effects and was safe.

Thus, in patients with uncontrolled H associated with O, a higher efficacy of SPC of P,I and A was established in comparison with FC of the same drugs, which persisted for a long time (12 months). The higher efficiency of SPC in this patients was associated with higher adherence, favorable effect on metabolic parameters and the severity of asymptomatic HMOD in comparison with FC. All of the above points to the prospect wider application of SPC of P,I and A for the treatment of such a complex category of patients as patients with uncontrolled H and with O.

4.1. Study Limitations

As the first limitation may be that not a very big cohort of patients were included in the work. A small number of patients were unable to identify differences between SPC and FC in terms of their effect on the severity of asymptomatic HMOD after 12 months of treatment. The second limitation is that the frequency of reaching BP <130/80 mm Hg was not analyzed. The third limitation may be that the effectiveness of the compared therapy options was not analyzed depending on the initial BP profile according to the ABPM data. However, despite these limitations, the work convincingly demonstrated the important advantages of using SPC in patients with uncontrolled H and with O.

5. Conclusions

SPC of P, I and A shows greater efficiency than FC, and makes it possible to maintain BP within the target levels for a long time in patients with uncontrolled H associated with O. The high efficiency of SPC associated with significantly increased adherence to therapy in comparison with FC. To achieve target BP levels with SPC, lower doses of drugs were required than with FC. SPC and FC in patients with H and O contributed to the inhibition of asymptomatic HMOD progression, did not adversely affect metabolic parameters, and were characterized by high safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SMK. and AEB; methodology, SMK and AEB; software, VIP.; validation, SMK and AEB; formal analysis, OVM and MYP; investigation, OVM and MYP; resources, OVM and MYP; data curation, OVM and MYP; writing—original draft preparation, SMK, OVM, MYP, VIP and AEB; writing—review and editing, SMK, OVM, MYP, VIP and AEB; visualization, OVM and MYP; supervision, SMK; project administration, SMK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by approved by the local Ethical Committee of GI “L.T. Malaya Therapy National Institute of the National Academy of Medical Science of Ukraine” (18.01.2018). Before the start of the study all patients signed a voluntary informed consent to participate in this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study cannot be deposited into data repositories or published as supplementary information in the journal due to the lack of consent of the patients included in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients for their participation in this long-term twelve-month study, and the doctors, nurses, and administrative staff in the Government Institution “L.T. Malaya Therapy National Institute of the National Academy of Medical Science of Ukraine” (Kharkiv, Ukraine).

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors did not use generative artificial intelligence and artificial intelligence-assisted technologies in the writing process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABPM |

Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring |

| ACE |

angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| AH |

arterial hypertension |

| Aml |

amlodipine |

| AO |

abdominal obesity |

| BMI |

body mass index |

| BP |

blood pressure |

| CAD |

coronary artery disease |

| CCA |

common carotid artery |

| CCB |

calcium channel blocker |

| CI |

confidence interval |

| CKD |

chronic kidney disease |

| DBP |

diastolic blood pressure |

| DBP(24) |

average daily diastolic blood pressure |

| DBP(D) |

average daytime diastolic blood pressure |

| DBP(N) |

average night-time diastolic blood pressure |

| DBPV(24) |

average daily diastolic blood pressure variability |

| DNDBPR |

degree of night-time diastolic blood pressure reduction |

| DNSBPR |

degree of night-time systolic blood pressure reduction |

| eGFR |

estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| FHG |

fasting hyperglycemia |

| HbA1c |

Hemoglobin A1c |

| HDL-C |

high density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HMOD |

hypertension-mediated organ damage |

| HOMA-IR |

homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance |

| HUA |

hyperuricemia |

| IMT |

intima-media thickness |

| Ind |

indapamide |

| IR |

insulin resistance |

| LDL-C |

low density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LVH |

left ventricular hypertrophy |

| LVMM |

left ventricular myocardial mass |

| LVMMI |

left ventricular myocardial mass index |

| MetS |

metabolic syndrome |

| P |

perindopril |

| PBP |

pulse blood pressure |

| SBP |

systolic blood pressure |

| SBP(24) |

average daily systolic blood pressure |

| SBP(D) |

average daytime systolic blood pressure |

| SBP(N) |

average night-time systolic blood pressure |

| SBPV(24) |

average daily systolic blood pressure variability |

| SUA |

serum uric acid |

| TC |

total cholesterol |

| TD |

thiazide diuretic |

| TG |

triglycerides |

| TIDBP(24) |

time-index 24-hour diastolic blood pressure |

| TISBP(24) |

time-index 24-hour systolic blood pressure |

| TLD |

thiazide-like diuretic |

References

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Rosei, E.A.; Azizi, M.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifkova, R.; Blankestijn, P. Hypertensive as a cardiovascular risk factor. In: Manual of Hypertension of the European Society of Hepertension. Third Edition. Edited by G. Mancia, G. Grassi, K.P. Tsioufis, A.F. Dominiczak, E. Agabiti Rosei. CRC Press. 2019:7-17.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Hypertension in Adults: Diagosis and Management. NICE Guideline [NG136]. 2019. Available online: https:// www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136 (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Brant, L.C.C.; Passaglia, L.G.; Pinto-Filho, M.M.; de Castilho, F.M.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; et al. The burden of resistant hypertension across the world. Curr Hypertens Rep 2022, 24, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: A pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Lancet 2021, 398, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redon, J.; Martinez, F.; Pichler, G. The metabolic syndrome in hypertension. In: Manual of Hypertension of the European Society of Hepertension. Third Edition. Edited by G. Mancia, G. Grassi, K.P. Tsioufis, A.F. Dominiczak, E.Agabiti Rosei. CRC Press. 2019:135-147.

- Landsberg, L. Obesity. In.: Hypertension: A Companion to Braunwald’s Hear Disease. Third edition. G.L. Bakris, M.J. Sorrentino. 2018, 328-334.

- Koval, S.M.; Snihurska, I.O.; Mysnychenko, O.V.; Lytvynova, O.M. Insulin resistance and its relationships with cardiac-metabolic factors in patients with arterial hypertension with obesity. Probl. Endocr. Pathol. 2022, 2, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Koval, S.M.; Snihurska, I.O.; Vysotska, O.; Strashnenko, H.M.; Wójcik, W.; et al. Prognosis of essential hypertension progression in patients with abdominal obesity. In book: Information Technology in Medical Diagnostics II, Wójcik, Pavlov& Kalimoldayev (Eds). London: Taylor&Francis Group, 2019: 275-288. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, M.; Amar, L.; Lorthioir, A.; Madjalian, A.M. Resistant hypertension: Medical treatment. In: Manual of Hypertension of the European Society of Hepertension. Third Edition. Edited by G. Mancia, G. Grassi, K.P. Tsioufis, A.F. Dominiczak, E. Agabiti Rosei. CRC Press. 2019:135-147.

- Mahfoud, F.; Kieble, M.; Enners, S.; Kintscher, U.; Laufs, U.; Bohm, M.; Schulz, M. Use of fixed-dose combination antihypertensives in Germany between 2016 and 2020: An example of guideline inertia. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2023, 112, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savare, L.; Rea, F.; Corrao, G.; Mancia, G. Use of initial and subsequent antihypertensive combination treatment in the last decade: Analysis of a large Italian database. J Hypertens 2022, 40, 1768–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirk, D.; Noll, S.; Burnier, M.; Rimoldi, S.; Noll, G.; et al. First Line CombinAtion Therapy in the Treatment of Stage II and III Hypertension (FLASH). Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, B.M.; Kjeldsen, S.E.; Narkiewicz, K.; Kreutz, R.; Burnier, M. Single-pill combinations, hypertension control and clinical outcomes: Potential, pitfalls and solutions. Blood Press 2022, 31, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnier, M. Single-pill combination treatments in hypertension. In: Manual of Hypertension of the European Society of Hepertension. Third Edition. Edited by G. Mancia, G. Grassi, K.P. Tsioufis, A.F. Dominiczak, E. Agabiti Rosei. CRC Press. 2019:337-343.

- Borghi, C.; Jayagopal, P.B.; Konradi, A.; Bortolotto, L.A.; Esposti, L.D.; Perrone, V.; Snyman, J.R. Adherence to Triple Single-Pill Combination of Perindopril/Indapamide/Amlodipine: Findings from Real-World Analysis in Italy. Adv Ther 2023, 40, 1765–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaa, A.; Townsendb, D.M.; Schiavonc, L.; Torina, G.; Lentie, S.; et al. Long-term effect of the perindopril/indapamide/amlodipine single-pill combination on left ventricular hypertrophy in outpatient hypertensiv subjects. Biomed. Pharmacotherapy. 2019, 120, 109539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habboush, S.; Sofy, A.A.; Masoud, A.T.; Cherfaoui, O.; Farhat, A.M.; et al. Efficacy of Single-Pill, Triple Antihypertensive Therapy in Patients with Uncontrolled Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2022, 29, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk: The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur. Heart J. 2019, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catapano, A.L.; Graham, I.; Backer, G.D.; Wiklund, O.; Chapman, M.J.; et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) Developed with the special contribution of the European Assocciation for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Atherosclerosis 2016, 253, 281–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, K.G.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- on Detection ENCEPNEP, of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) T. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee For International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2006, 65, 1312–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio report of a WHO expert consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

- O’Brien, E.; Parati, G.; Stergiou, G.; Asmar, R.; Beilin, L.; et al. European Society of Hypertension Position Paper on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring. J. Hypertens. 2013, 31, 1731–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Marcos, M.A.; Recio-Rodríguez, J.I.; Patino-Alonso, M.C.; Agudo-Conde, C.; Gómez-Sanchez, L.; et al. Protocol for measuring carotid intima-media thickness that best correlates with cardiovascular risk and target organ damage. Am. J. Hypertens. 2012, 25, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F.; et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; et al. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parati, G.; Kjeldsen, S.; Coca, A.; Cushman, W.C.; Wang, J. Adherence to single-pill versus free-equivalent combination therapy in hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension 2021, 77, 692–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persu, A.; Lopez-Sublet, M.; Algharably, E.A.E.; Kreutz, R. Starting antihypertensive drug treatment with combination therapy: Controversies in hypertension - pro side of the argument. Hypertension 2021, 77, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, S.M.; Snihurska, I.O.; Starchenko, T.G.; Penkova, M.Y.; Mysnychenko, O.V.; Berezin, A.E.; et al. Efficacy of fixed dose of triple combination of perindopril-indapamide-amlodipine in obese patients with moderate-to-severe arterial hypertension: An open label 6-month study. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2019, 6, 3501–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallares-Carratala, V.; Bonig-Trigueros, I.; Palazon-Bru, A.; Esteban-Giner, M.J.; Gil-Guillen, V.F.; et al. Clinical inertia in hypertension: A new holistic and practical concept within the cardiovascular continuum and clinical care process. Blood Press 2019, 28, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).