Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

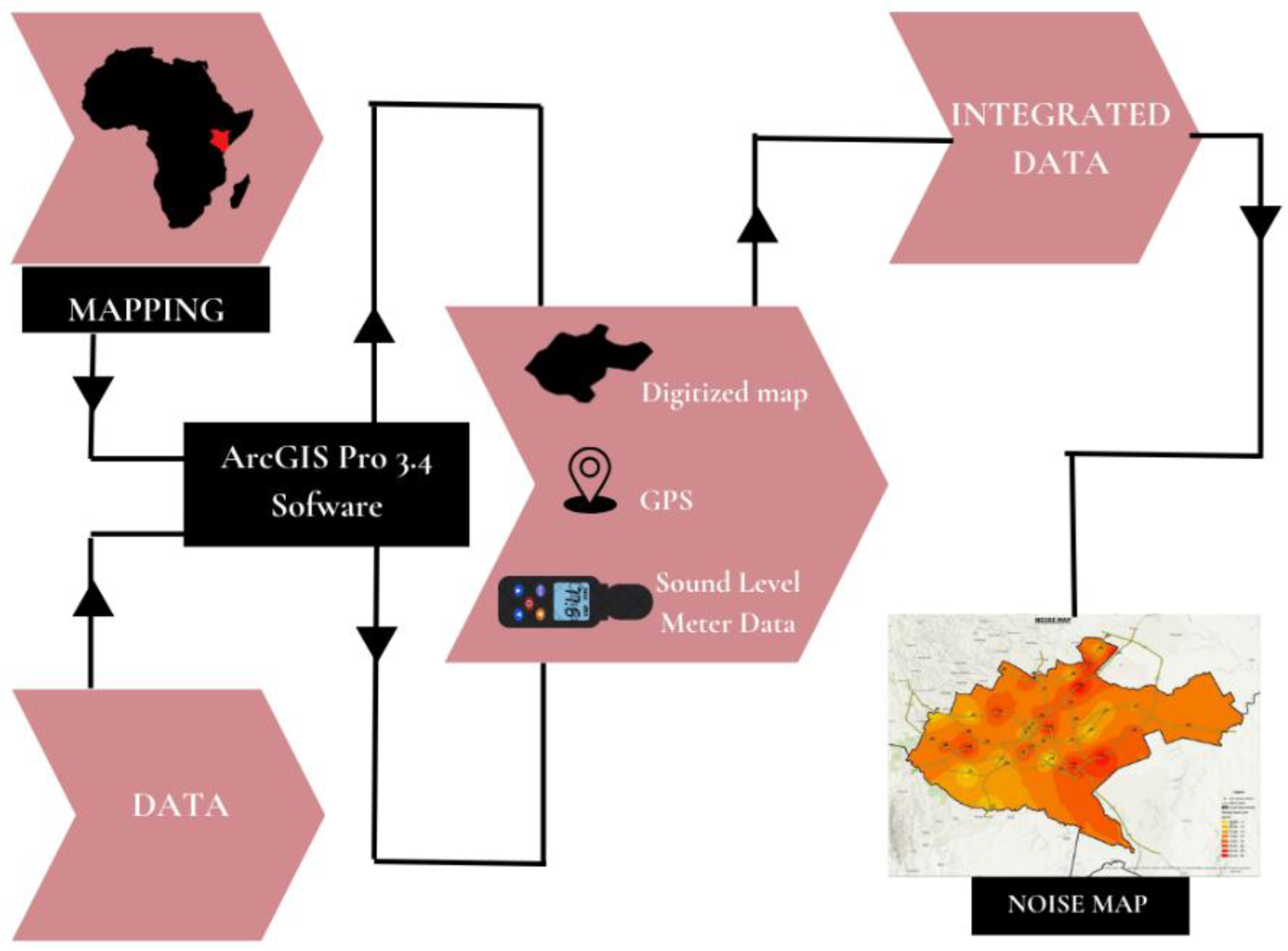

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Site Selection

2.2. Data Acquisition

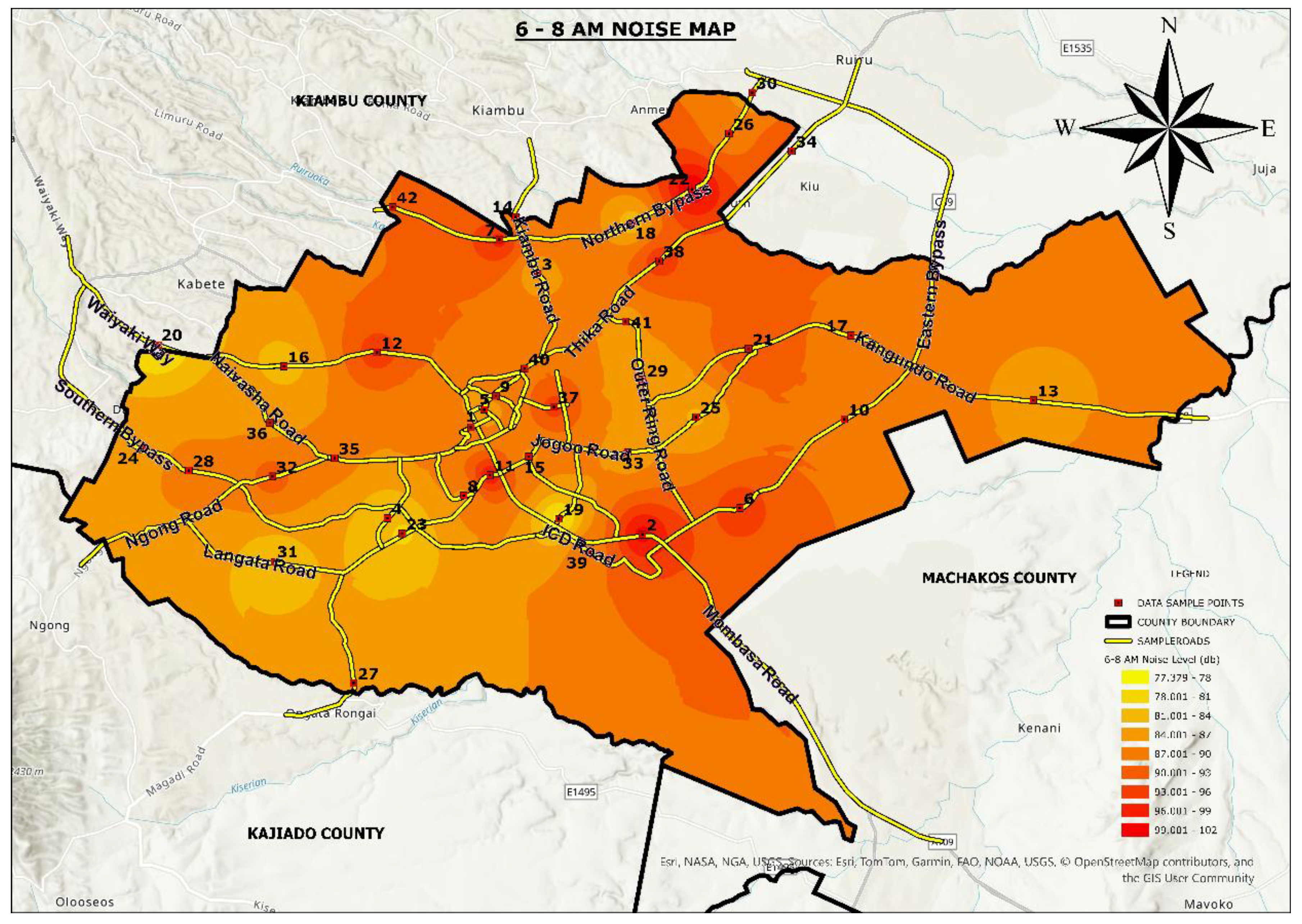

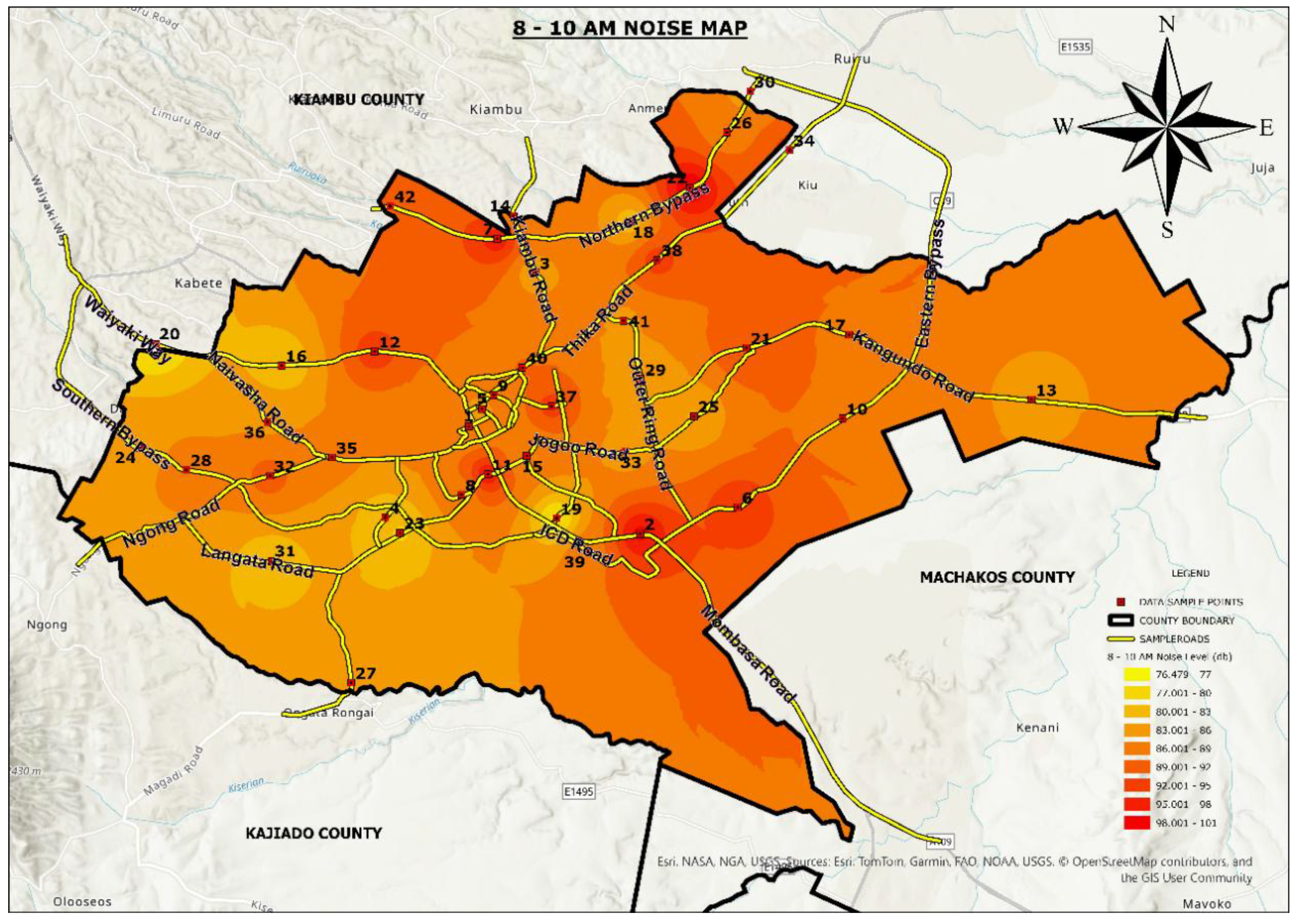

2.3. RTN Noise Mapping

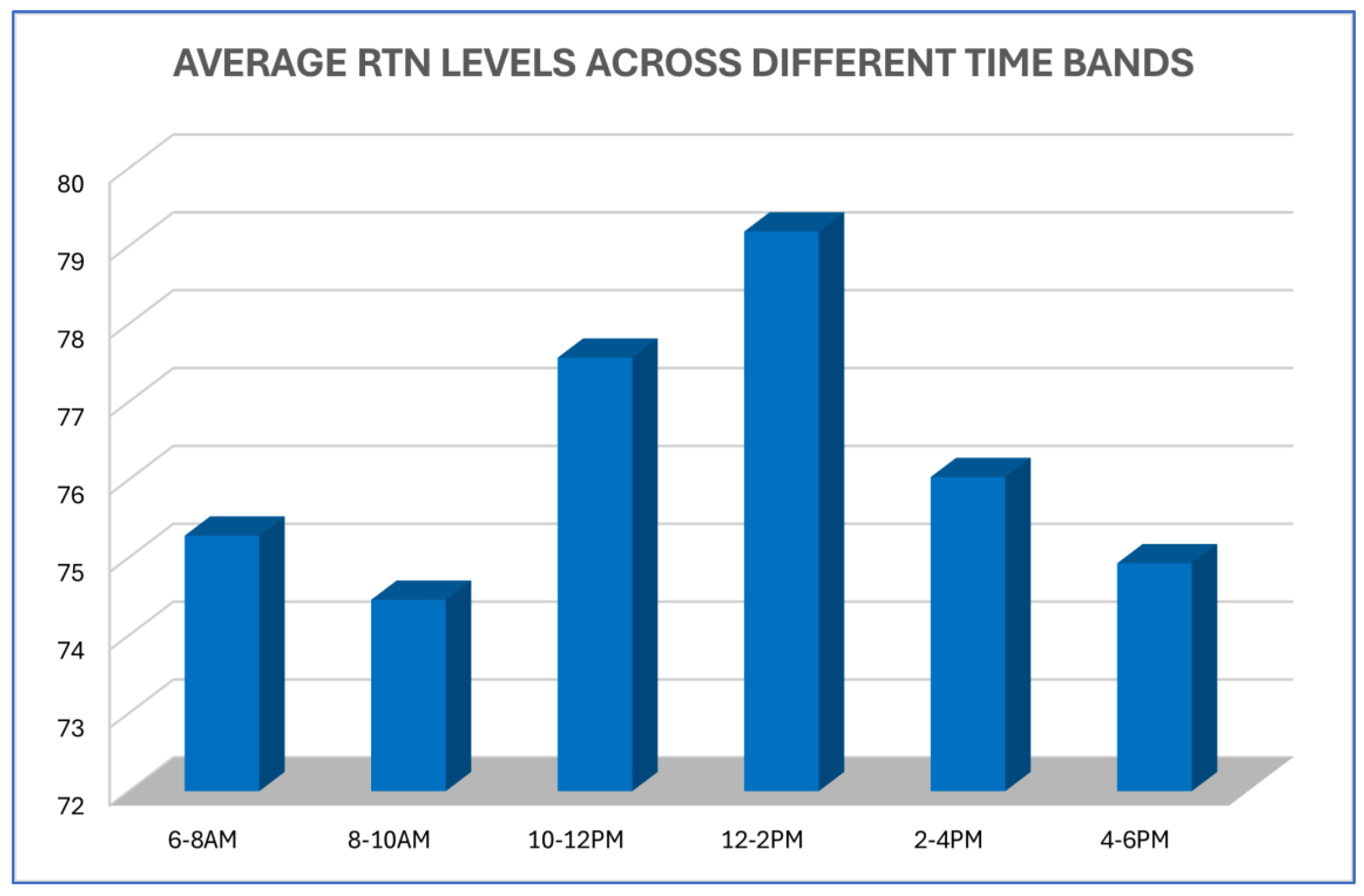

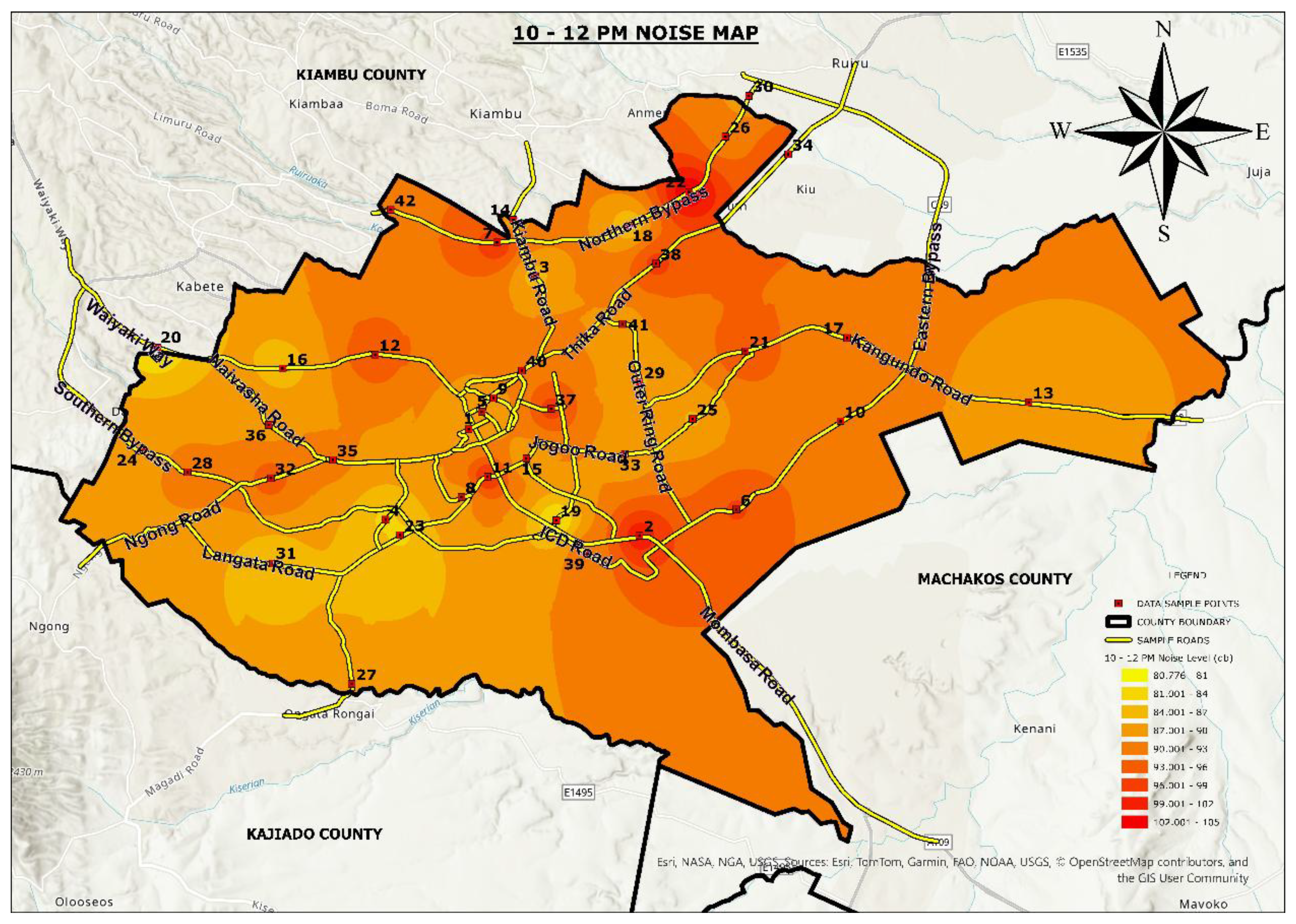

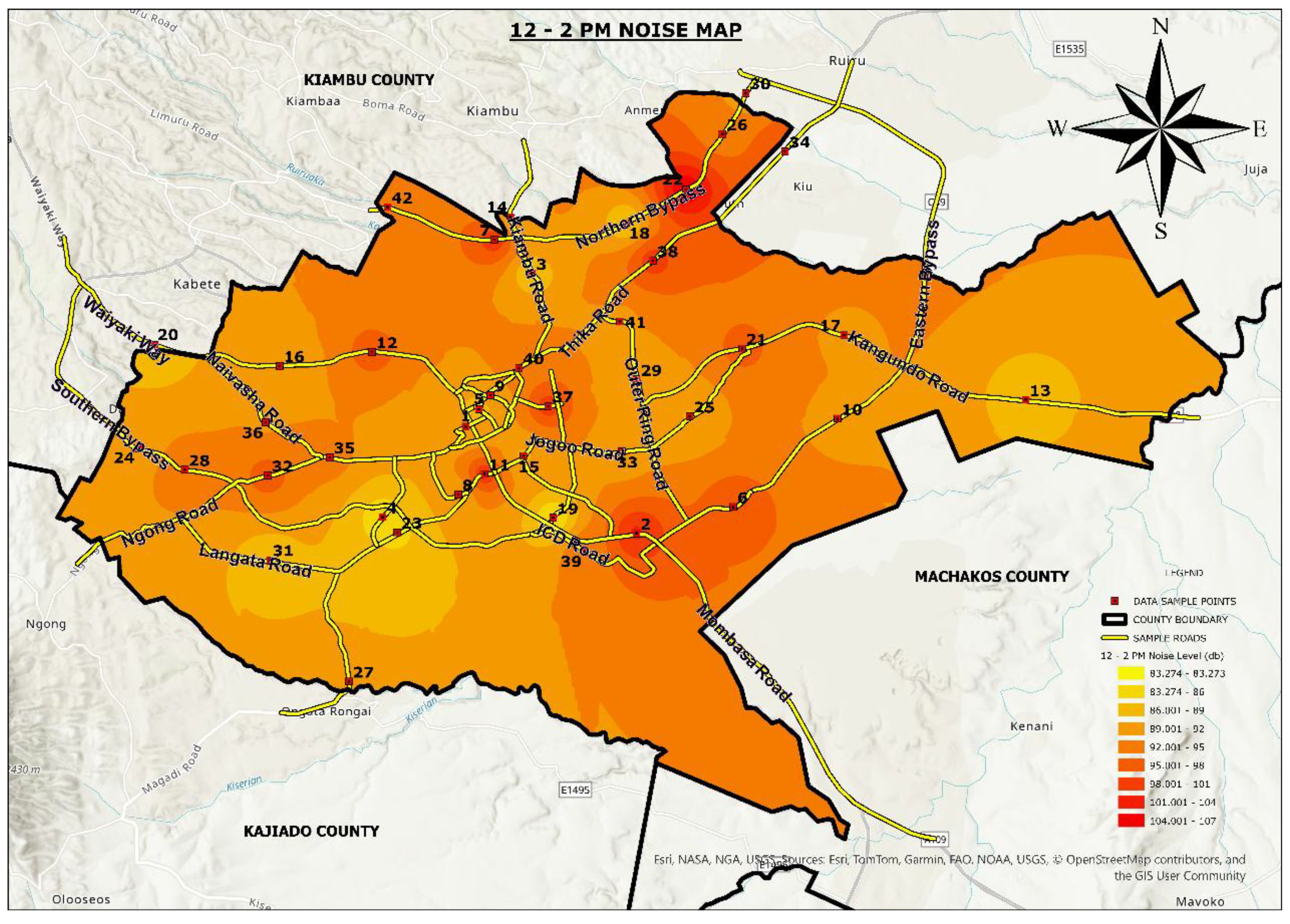

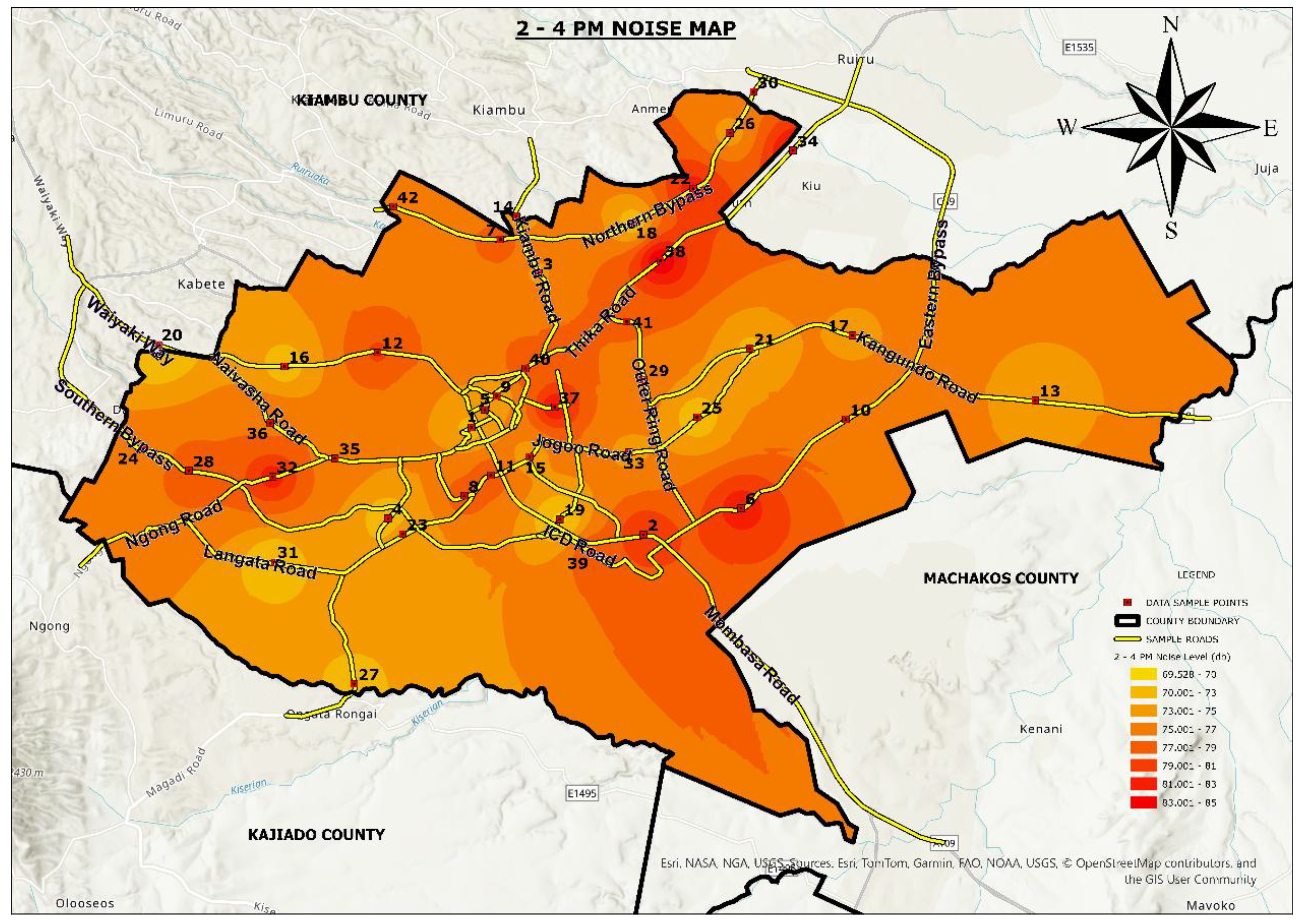

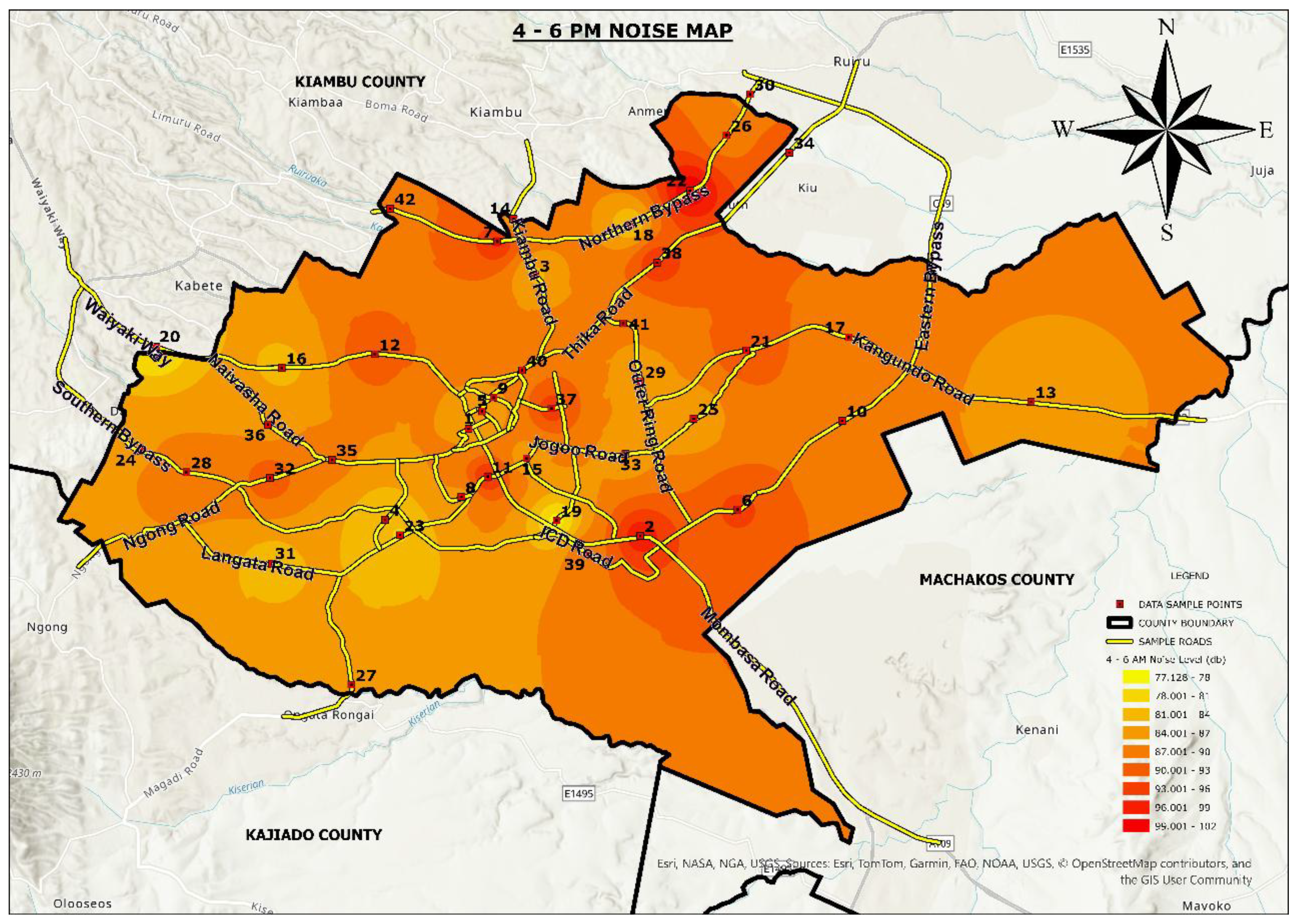

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Appendix 1

| Place | X-Coord | Y-Coord | 6 AM-8 AM | 8 AM-10 AM | 10 AM-12 PM | 12 PM-2 PM | 2 PM-4 PM | 4 PM-6 PM |

| 1 | 256896.83 | 9857588.15 | 72.82 | 71.62 | 73.67 | 74.57 | 71.67 | 71.07 |

| 2 | 264136.81 | 9853108.54 | 82.14 | 80.99 | 83.04 | 83.79 | 80.99 | 80.34 |

| 3 | 259705.60 | 9864042.77 | 75.19 | 74.09 | 76.14 | 76.84 | 74.74 | 73.49 |

| 4 | 253374.75 | 9853775.07 | 71.5 | 71.3 | 73.35 | 74.05 | 71.35 | 70.65 |

| 5 | 257452.84 | 9858326.03 | 74.9 | 75.15 | 76.9 | 77.9 | 75.2 | 74.6 |

| 6 | 268248.56 | 9854218.08 | 82.07 | 82.02 | 84.07 | 84.77 | 82.07 | 81.47 |

| 7 | 258096.36 | 9865454.82 | 78.21 | 78.56 | 80.61 | 81.31 | 78.61 | 78.01 |

| 8 | 256590.06 | 9854730.41 | 77.65 | 78 | 80.05 | 80.75 | 78 | 77.35 |

| 9 | 257947.14 | 9858910.23 | 73.42 | 73.32 | 75.37 | 76.07 | 73.32 | 72.77 |

| 10 | 272667.35 | 9857939.17 | 77.69 | 76.79 | 78.84 | 79.54 | 76.79 | 76.24 |

| 11 | 258094.93 | 9867236.88 | 76.81 | 75.81 | 77.86 | 78.56 | 75.81 | 75.26 |

| 12 | 257702.58 | 9855591.69 | 79.64 | 78.79 | 80.84 | 81.54 | 78.84 | 78.24 |

| 13 | 252935.73 | 9860718.79 | 80.02 | 79.17 | 81.22 | 81.92 | 79.22 | 78.62 |

| 14 | 280644.38 | 9858744.19 | 75.05 | 74.2 | 76.25 | 76.95 | 74.25 | 73.65 |

| 15 | 258775.95 | 9866407.85 | 74.2 | 73.35 | 75.4 | 76.1 | 73.4 | 72.7 |

| 16 | 259340.90 | 9856361.23 | 74.69 | 73.84 | 75.89 | 76.59 | 73.84 | 73.29 |

| 17 | 249008.64 | 9860131.61 | 70.39 | 67.99 | 73.29 | 77.24 | 71.99 | 70.54 |

| 18 | 272942.89 | 9861441.77 | 74.64 | 74.09 | 75.64 | 76.89 | 74.44 | 73.64 |

| 19 | 263693.17 | 9866165.94 | 71.83 | 70.68 | 74.18 | 75.43 | 71.78 | 70.78 |

| 20 | 260611.02 | 9853750.71 | 67.81 | 66.91 | 71.21 | 73.71 | 69.51 | 67.56 |

| 21 | 243719.36 | 9861018.07 | 68.21 | 66.81 | 71.76 | 75.26 | 70.06 | 67.91 |

| 22 | 268614.18 | 9860885.34 | 72.38 | 71.63 | 74.63 | 75.38 | 72.68 | 71.63 |

| 23 | 266227.84 | 9867581.20 | 79.91 | 78.96 | 83.11 | 84.91 | 81.71 | 80.16 |

| 24 | 253993.82 | 9853130.38 | 71.95 | 71.1 | 75.2 | 77.15 | 73.9 | 72.4 |

| 25 | 243042.87 | 9856654.09 | 73.39 | 72.54 | 76.54 | 78.625 | 75.54 | 74.44 |

| 26 | 266390.05 | 9858026.26 | 69.32 | 68.47 | 72.42 | 74.52 | 71.57 | 70.07 |

| 27 | 267772.27 | 9869917.36 | 71.9 | 70.8 | 74.85 | 76.85 | 74.2 | 71.8 |

| 28 | 251958.55 | 9846860.37 | 70.61 | 69.46 | 73.31 | 75.41 | 72.56 | 70.51 |

| 29 | 244992.07 | 9855764.76 | 75.89 | 75.04 | 78.69 | 80.99 | 78.29 | 76.39 |

| 30 | 264131.37 | 9859591.32 | 73.43 | 72.58 | 76.23 | 78.53 | 75.47 | 74.48 |

| 31 | 268760.56 | 9871638.60 | 74.43 | 73.58 | 77.23 | 79.53 | 75.99 | 75.03 |

| 32 | 248613.98 | 9851927.16 | 68.73 | 67.88 | 71.53 | 73.83 | 70.98 | 69.53 |

| 33 | 248517.89 | 9855522.13 | 79.65 | 78.8 | 82.7 | 84.75 | 81.885 | 80.4 |

| 34 | 263515.43 | 9856549.12 | 73.6 | 72.8 | 75.95 | 77.75 | 74.475 | 73.1 |

| 35 | 270432.25 | 9869181.99 | 82.63 | 81.68 | 85.08 | 87.38 | 83.18 | 81.93 |

| 36 | 251145.89 | 9856292.64 | 75.49 | 74.64 | 78.34 | 80.69 | 76.49 | 75.34 |

| 37 | 248423.11 | 9857765.12 | 76.13 | 75.28 | 78.98 | 81.33 | 76.83 | 75.78 |

| 38 | 260390.54 | 9858451.41 | 80.59 | 79.74 | 83.79 | 85.79 | 82.89 | 81.39 |

| 39 | 264838.81 | 9864569.18 | 82.65 | 81.4 | 85.1 | 87.45 | 84.55 | 83.45 |

| 40 | 261941.98 | 9852338.53 | 76.91 | 75.71 | 79.36 | 81.66 | 78.46 | 77.05 |

| 41 | 259152.23 | 9860048.07 | 77.36 | 76.51 | 80.41 | 82.46 | 78.51 | 77.16 |

| 42 | 263418.15 | 9862017.95 | 76.02 | 75.17 | 78.82 | 81.12 | 77.42 | 76.72 |

References

- Arseni, M., Voiculescu, M., Georgescu, L. P., Iticescu, C., & Rosu, A. (2019). Testing different interpolation methods based on single beam echosounder river surveying: Case study—Siret River. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 8(11), 507. [CrossRef]

- Bartier, P. (1996). Multivariate interpolation to incorporate thematic surface data using inverse distance weighting (IDW. Computers & Geosciences. [CrossRef]

- Basner, M., Babisch, W., Davis, A., Brink, M., Clark, C., Janssen, S., and Stansfeld, S. (2014). Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. The Lancet, 383(9925), 1325–1332. [CrossRef]

- Bélisle, E., Huang, Z., Le Digabel, S., and Gheribi, A. (2015). Evaluation of machine learning interpolation techniques for prediction of physical properties. Computational Materials Science, 98, 162–172. [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, G. S., Shit, P. K., & Maiti, R. (2018). Comparison of GIS-based interpolation methods for spatial distribution of soil organic carbon (SOC). Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, 17, 114–126. [CrossRef]

- Boumpoulis, V., Michalopoulou, M., & Depountis, N. (2023). Comparison between different spatial interpolation methods for the development of sediment distribution maps in coastal areas. Earth Science Informatics, 16, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Dey, J., Laxmi, V., Kalawapudi, K., Singh, T., Vijay, R., Motghare, V. M., and Kumar, R. (2021). Strategic noise mapping of Mumbai city, India: A GIS-based approach. Applied Acoustics, 48, 202–212.

- Esmeray, E., and Eren, S. (2021). GIS-based mapping and assessment of noise pollution in Safranbolu, Karabuk, Turkey. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(10), 15413–15431. [CrossRef]

- Garg, N., Sinha, A., Dahiya, M., Gandhi, V., Bhardwaj, R., & Akolkar, A. (2017). Evaluation and analysis of environmental noise pollution in seven major cities of India. Archives of Acoustics, 42(2), 175–188. [CrossRef]

- İlgürel, N., Akdağ, N., and Akdağ, A. (2016). Evaluation of noise exposure before and after noise barriers: A simulation study in Istanbul. Journal of Environmental Engineering and Landscape Management, 24(4), 293–302. [CrossRef]

- İmamoglu, M. Z., & Sertel, E. (2016). Analysis of different interpolation methods for soil moisture mapping using field measurements and remotely sensed data. International Journal of Environment and Geoinformatics, 3(3), 11–25.

- Islam, R., Sultana, A., Reja, M. S., Seddique, A. A., & Hossain, M. R. (2024). Multidimensional analysis of road traffic noise and probable public health hazards in Barisal city corporation, Bangladesh. Heliyon, 10(15), e35161. [CrossRef]

- Jalilzadeh, R. (2007). Evaluation of noise pollution using GIS: Case study of the 9th district of Tehran, Iran. Proceedings of the MapAsia 2007 Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, August 14–16.

- Morillas, J. M. B., Escobar, V. G., Sierra, J. A. M., Vílchez-Gómez, R., and Trujillo Carmona, J. (2002). An environmental noise study in the city of Cáceres, Spain. Applied Acoustics, 63(10), 1061–1070. [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T., Schmidt, F. P., Steven, S., Herzog, J., Daiber, A., & Sørensen, M. (2018). Environmental noise and the cardiovascular system. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 71(6), 688-697. [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T., Sørensen, M., Gori, T., Schmidt, F. P., Rao, X., Brook, F. R., Chen, L. C., Brook, R. D., and Rajagopalan, S. (2017). Environmental stressors and cardio-metabolic disease: Part II—Mechanistic insights. European Heart Journal, 38(8), 557–564. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E., and King, E. (2014). Environmental noise pollution: Noise mapping, public health, and policy. Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E., and King, E. A. (2010). Strategic environmental noise mapping: Methodological issues concerning the implementation of the EU Environmental Noise Directive and their policy implications. Environment International, 36(3), 290–298. [CrossRef]

- Ozer, S., Yilmaz, H., Yesil, M., & Yesil, P. (2009). Evaluation of noise pollution caused by vehicles in the city of Tokat, Turkey. Scientific research and essay, 4(11), 1205-1212.

- Partheeban, P., Krishnamurthy, K., Partheeban, N. E., Krishnan, S., and Baskaran, A. (2022). Urban road traffic noise on human exposure assessment using geospatial technology. Environmental Engineering Research, 27(5), 210249. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, V., Tripathi, B. D., and Mishra, V. K. (2008). Evaluation of traffic noise pollution and attitudes of exposed individuals in working place. Atmospheric Environment, 42(16), 3892–3898. [CrossRef]

- Singh Upendrasingh R., Shivendra Kumar Jha, (2023) Integrating GIS in Road Traffic Noise Assessment: A Review of Methods and Applications. Journal of Neonatal Surgery, 12, 74-78.

- Thanh, B. P. P., & Hạnh, N. T. X. (2021). Mapping and distribution of noise using IDW interpolation algorithm in Thuan An city, Binh Duong province. Thu Dau Mot University Journal of Science, 3(4), 64–76. [CrossRef]

- Ware, C., Knight, W., & Wells, D. (1991). Memory intensive statistical algorithms for multibeam bathymetric data. Computers & Geosciences, 17(7), 985-993. [CrossRef]

- Wawa, E. A., & Mulaku, G. C. (2015). Noise pollution mapping using GIS in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Geographic Information System, 7(5), 486-493. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M. I., Dubey, R., Bharadwaj, S., Kumar, A., Paswan, K. K., Srivastava, A., ... & Biswas, S. (2023). GIS based road traffic noise mapping and assessment of health hazards for a developing urban intersection. In Acoustics (Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 87-119). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., Zhang, M., Gao, X., Gao, J., & Kang, J. (2024). Analysis of traffic noise spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors in high-density cities. Applied Acoustics, 217, 109838. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).