1. Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the leading gynecologic cancer and the fourth leading cancer diagnosis in Europe and North America [

1]. Given that endometrial carcinomas frequently present as low-grade tumors diagnosed in early stages, disease associated mortality remains low. However, a subset of low-grade early-stage tumors can demonstrate aggressive behavior [

2]. The introduction of endometrial cancer molecular profiles has significantly improved our understanding of tumor biology and has provided a valuable prognostic tool [

3,

4]. However, most cases belonging to this specific subset of endometrial carcinomas are classified as no specific molecular profile (NSMP) or Mismatch Repair-deficient (dMMR), which are associated with variable disease outcomes. As a result, there are ongoing efforts to further refine the molecular classification of these carcinomas.

In recent years, there has been a surge in molecular biomarkers that can potentially explain the variable tumor behavior of low-grade early-stage endometrial carcinomas [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Of these,

CTNNB1 gene mutations have demonstrated to be associated with an adverse prognosis [

9,

10]. Tumors harboring

CTNNB1 mutations show increased risk of relapses, and distant metastases.

CTNNB1 gene encodes the β-catenin protein, which is involved in canonical Wnt signaling pathway. This pathway is involved in various biological processes including tumor growth, migration, and metastasis [

11,

12,

13]. In addition, this pathway has been associated with other relevant aspects of tumor biology like anti-tumor immune response evasion [

14] or epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) [

15]. Indeed, Wnt pathway dysregulation is associated with several malignancies, including colorectal carcinoma, head and neck tumors, and infrequent pediatric neoplasms [

16,

17,

18]. However, the biological implications of these mutations in low-grade early-stage endometrial tumors remains incompletely understood.

Proteomics has long been considered a powerful tool to interrogate the molecular landscape of malignancies [

19]. Recently, researchers have used proteomics to characterize endometrial carcinomas [

20,

21,

22]. The use of this comprehensive technology has facilitated the discovery of relevant protein expression markers associated with low grade endometrial cancer biology [

21]. REcently, there have been efforts to optimize the performance of this type of “omic” technologies using Formalyn Fixed Paraffin Embedded (FFPE) Tissue samples [

23]. Therefore, combining shotgun proteomics with FFPE samples which are readily available in the clinical setting is a promising approach to improve biomarker discovery and our understanding of tumor biology. In the present work, we aim to harness the power of shotgun proteomics to further explore the biological impact of

CTNNB1 mutations using FFPE samples from low-grade early-stage endometrial carcinomas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection and CTNNB1 Mutation Determination

For proteomic analysis tumor samples from low-grade (FIGO Grade G1 or G2) early stage (FIGO stage 2018 I or II) endometrioid endometrial carcinomas (EEC) were selected from the archives of Hospital Universitario La Paz. To be eligible, patients must have been treated with histerectomy between 2003 and 2015. Formalin Fixed Paraffin Embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks obtained from hysterectomy specimens were used for proteomic analysis. To interrogate

CTNNB1 mutation status we performed

CTNNB1 exon 3 sequencing as previously published [

10]. We selected FFPE tissue samples containing at least 50% of viable tumor cells. DNA from these samples was obtained by QIAamp FFPE tissue kit (Qiagen) and used for PCR and Sanger sequencing. CTNNB1 exon 3, encompassing the region of GSK-3β phosphorylation site, was amplified with these specific primers (5′-3′): GATTT-GATGGAGTTGGACATGG and TGTTCTTGAGTGGAAGGACTGAG. Only pathogenic (COSMIC scores > 0.7) variants were considered.

2.2. Protein Extraction and Processing

Tissue samples were sectioned using a microtome (10 µm thick), transferred into 1.5 ml tubes, and deparaffinized by incubation with xylol for 5 min at 56°C followed by sequential ethanol washes (100%, 95%, 80%, and 50%). The samples were boiled by heating for 2 h at 95°C (500 rpm). Tissue samples were air-dried followed by resuspension in EasyPep Lysis Buffer. Protein concentration of the samples was measured using Qubit Protein Assay. Sample preparation for reduction, alkylation, trypsin digestion, and cleanup were performed according to the EasyPep protocol.

2.3. TMT Labelling and LC-MS

TMT labelling was performed as previously described [

24]. In brief, TMT reagents (0.8 mg) were dissolved in aceto-nitrile (40 μL) of which 20 μL was added to the peptides (50 μg). Peptide quantification was performed by Thermo Scientific™ Pierce™ Quantative Colorimetric Peptide assay to determine peptide concentration before LC-MS loading and TMT experiments. Normalized digested samples were labeled by incubation at room temperature for 1h (500 RMP) with TMT10plex reagents. The reaction was quenched with hydroxylamine to a final concentration of 0.3% (v/v). TMT-labeled samples were pooled at a 1:1 ratio across all 10 samples. For each experiment, the pooled sample was vacuum centrifuged to near dryness. Pierce High pH Reversed-Phase Fractionation Kits were used to fractionate TMT-labeled digest samples into eight fractions by an increasing acetonitrile step-gradient elution. Fractions were dried in a vacuum centrifuge and resuspended in 0.1% formic acid prior to LC-MS analysis.

Afterwards, the fractions were mixed into six fractions, dried under vacuum, then resuspended in 12 µl and quantified by fluorimetry (QuBit) as previously described [

25]. One μg of each sample was subjected to nano-Liquid Chromatography coupled to Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry using a nano Easy 100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled online to an Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) [

23]. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [

26] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD068004.

2.4. Validation Cohort

Proteomic, transcriptomic, CIBERSORT cell deconvolution scores and whole exome sequencing data from the CPTAC-endometrial carcinoma consortium was accessed from the LinkedOmics repository [

27]. Patients diagnosed with low-grade early stage endometrioid endometrial carcinomas were selected. Samples without tumor purity information were also excluded from the analysis.

CTNNB1 mutation status was obtained from the whole exome sequencing curated data including all mutation types of

CTNNB1. Normalized proteomic data and transcriptomic data as well as CIBERSORT data were used in further analyses.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To identify differentially expressed proteins we first analyzed differential expressions in the discovery cohort. We calculated the Log2FC as well as t-test followed by q-value correction using the qvalue Bioconductor R package (version 2.36.0). Proteins with a q value below 0.1 were subjected to further screening using the validation cohort. Further analyses were conducted on proteins that exhibited consistent differential expression profiles in both the discovery and validation cohorts, and that were among the top 10% of proteins that were either upregulated or downregulated in both groups.

Differentially expressed proteins were further analyzed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). We obtained pathway gene sets using the msigdbr R package (version 7.5.1). First, we identified pathways that contained at least one protein of interest from the Gene Ontology and Kegg pathway collections. We then performed GSEA using the fgsea Bioconductor R package (version 1.30.0). Proteomic data from both the discovery and validation cohorts along with transcriptomic data from the validation cohort were used to calculate the Normalized Enrichment Score for all the selected pathways. Pathway Enrichment Scores were subsequently screened by filtering out pathways that showed inconsistent up- or down-regulation profiles across the three data sets. Finally, pathways that ranked among the top 15% upregulated or downregulated in all three data sets were considered for further validation studies.

2.6. Quantitative PCR Analysis

RNA samples were isolated from representative FFPE tissue blocks from low-grade, early-stage primary EEC with and without

CTNNB1 mutation using QIAGEN RNeasy Mini kit following manufacturer instructions. RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed in an Mx3005p (Agilent) using the SYBR

® Green Quantitative RT-qPCR Kit (Merck). Expression of target RNAs was normalized using ACTB, GADPH, and PPIA genes as internal controls [

28]. A list of primers for VDAC1, VDAC2, Wnt5A, ROR2, and CAMK2A can be found in

Supplementary Table S1. Results were analyzed using the CT method [

29].

2.7. Tissue Based Analyses

To perform quantitative immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical analysis we constructed Tissue Micro arrays (TMAs) as previously reported [

30]. Each TMAs contained two 1.2mm cores per cancer sample obtained from hysterectomy specimen FFPE tissue blocks. Prior to analysis, TMA cores showing significant artefacts (tissue detachment) or an absence of tumor tissue were excluded.

Multiplex immunofluorescence was performed as previously published by our group [

30]. In brief, each TMA section was subjected to iterative rounds of antibody staining against CK (1:150, AE1/AE3; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), CD8 (1:150, 4B11; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), FOXP3 (1:50, 236A/E7; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and CD68 (1:75, PG-M1; Dako-Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Antibody binding was followed by tyramide signal amplification (TSA) visualization with fluorophores Opal-690, Opal-540, Opal-570, and Opal-620. Nuclei were counter-stained with DAPI (Akoya Biosciences). Immunofluorescence imaging and spectral unmixing were performed using the PhenoImager platform (Akoya Biosciences). Cell segmentation was performed using the SimpleSeg Bioconductor R package (version 1.4.1). Afterwards marker expression (quantile 97.5) was calculated for each cell and image channel, and cell expression was normalized using the COMBAT algorithm implemented in the mxnorm R package (version 1.0.3). Using protein expression data, cell phenotyping was conducted. To this end, we first identified positive/negative thresholds for each marker and phenotyping decision trees were designed to identify Tumor cells, CD8 T cells, Macrophages, and FOXP3 Treg cells. Cells not fulfilling criteria for any of the above-mentioned cell-types were classified as “other”. Total tissue area was approximated using cell coordinate information. To identify tumor and stromal compartments, tumor masks were constructed based on the spatial location of cells classified as tumor cells. To this end, we first filtered out spatially isolated tumor cells using a DBSCAN algorithm implemented in the dbscan R package (Version 1.1.12). Clustered cells were then used to approximate a concave hull and build tumor masks using the sf R package (Version 1.0.18).

After cell-density quantification, we conducted spatial interaction analyses using SpatialExperiment (version 1.12.0) and imcRtools (version 1.8.0) R packages. We analyzed the spatial interaction/repulsion pattern of CD8, Macrophage, Tregs, and Tumor cells. To this end, we first constructed a spatial neighborhood graph, using Delaunay triangulation for every cell-cell potential interaction. Homotypic and heterotypic cell interactions were quantified by dividing graph edges between graph nodes. Afterwards images were classified based on their cell-cell interaction patterns using a k-means algorithm with k=4. Spatial interaction clusters were compared across CTNNB1 mutated and Wild-type (WT) samples.

To analyze ROR2 protein expression, TMA sections were stained with a monoclonal anti-human ROR2 antibody (1:100, ROR2 2535-2835, QED bioscience). Sections were counter-stained using hematoxylin (Leica). An expert pathologist who was blind to CTNNB1 mutation status evaluated the samples. The average percentage of stained cells were calculated for every tissue core. Both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was considered irrespective of staining intensity.

To review the presence of squamous differentiation, a pathologist that was blind to

CTNNB1 mutation status was requested to review the hematoxilyn and eosin-stained tissue slides. First, whole tissue slides samples belonging to the discovery cohort used in the proteomic analysis were evaluated. Next, to evaluate the presence of squamous differentiation in the samples from the validation cohort, digitalized HE slides were downloaded from the Cancer Imaging Archive [

31]. Images were annotated using very large image viewer (VLIV) [

32] by the same pathologist.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics of Discovery and Validation Cohorts

The clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of the discovery and valida-tion cohorts have been recently published [

10,

21,

30], and summarized in

Table 1. A total of 18 tumors were analyzed in the discovery cohort (12 WT, 6 harboring

CTNNB1 mutations), whereas 60 tumors were included in the validation cohort (37 WT, 23

CTNNB1 mutated). Both

CTNNB1 WT and

CTNNB1 mutated tumors showed similar clinical and pathological characteristics. However, we observed that

CTNNB1 mutated tumors appeared in slightly older patients in the discovery cohort, with the opposite observance for the validation cohort. No dMMR tumor subtypes were included in the discovery cohort. However, immunohistochemical findings categorized six patients (10% of the validation cohort) as dMMR. Notably, no

POLE mutations were found in the discovery or validation cohort.

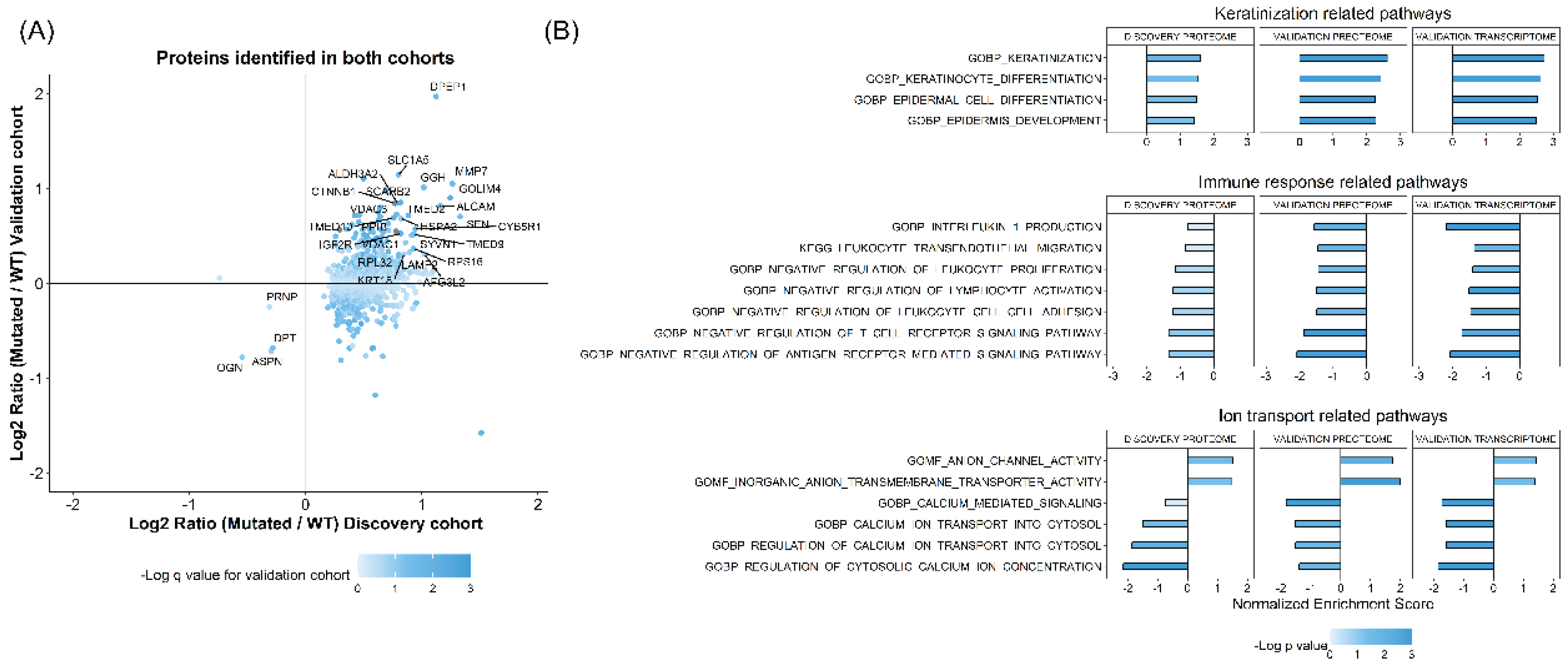

3.2. Protein Quantification and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

FFPE tissue samples from the 18 discovery cohort patients were subjected to shotgun proteomic analysis using a Q Exactive mass spectrometer and TMT10plex. A total of 1618 proteins were identified and quantified. As an initial screening strategy, we performed differential protein expression analysis between WT and

CTNNB1 mutated tumors, resulting in 1032 proteins with a q value below 0.1. The expression pattern of these proteins was further screened in the validation samples. Among these proteins, 934 were identified and quantified in the validation cohort, 474 showed the same up/down-regulation profile, and 30 were among the top 10% of up- or down-regulated proteins in both the discovery and the validation cohorts (

Figure 1A). The validated proteins displayed diverse biological functions. First, we identified β-catenin (encoded by

CTNNB1 gene) protein to be upregulated in

CTNNB1 mutated samples compared to WT samples. Second, we found several ion channels and amino acid transporters to be dysregulated in

CTNNB1 mutated samples, including VDAC1, VDAC3, and SLC1A5. We also identified several proteases and lysosomal associated proteins to be differentially expressed, like LAMP2, SCARB2, MMP7, GGH, and DPEP1. Additionally, other proteins associated with cell cytoskeletal system and cell adhesion were also dysregulated, including KRT18 and ALCAM. Finally, we also identified several proteins associated with protein translation and endoplasmic reticulum function, likeTMED2, TMED9, TMED10, RPL32, and RPS16.

Given the heterogeneous biological backgrounds of the differentially expressed proteins, we conducted a Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to further investigate the impact of

CTNNB1 mutations on the tumor proteome. To this end, we selected 1444 pathways from the GO and Kegg pathway repositories, that included at least one of our 30 proteins of interest. The Net Enrichment (NE) Score of these pathways was compared across the proteomic data of the discovery and validation sample sets as well as the transcriptomic data of the validation cohort. We selected pathways that showed a NE score within the highest or lowest 15% across the three datasets. After filtering, 24 pathways were found to be consistently dysregulated (

Figure 1B). These could be grossly classified into pathways associated with keratinization or squamous cell differentiation, immune microenvironment shaping, and cellular calcium homeostasis regulation.

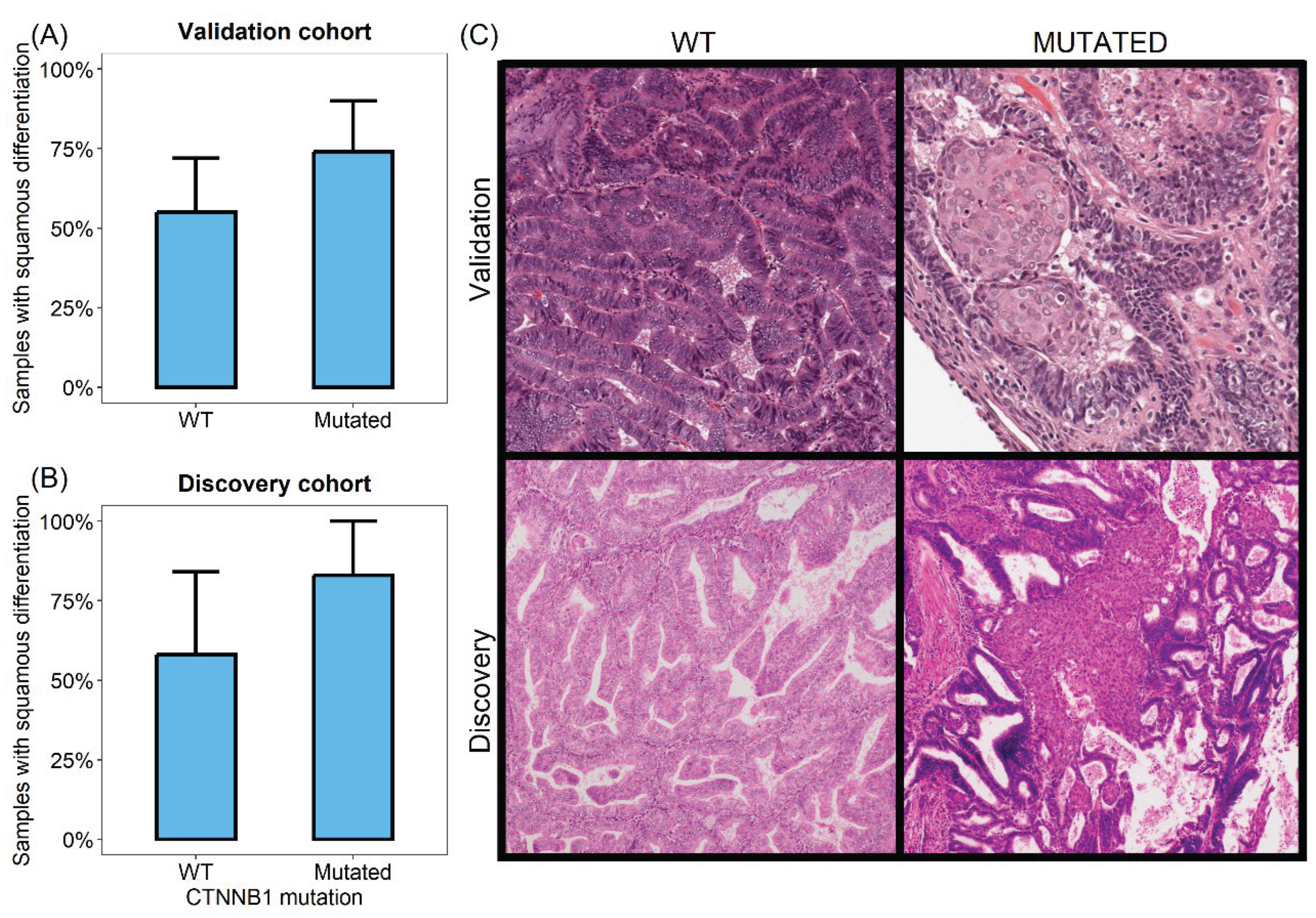

3.3. CTNNB1 Mutated Tumors Show Increased Squamous Differentiation Capabilities

Several of the differentially activated pathways in

CTNNB1 mutated tumors were related to keratinization and epidermal growth. This finding was consistently observed across proteomic and transcriptomic databases. To further validate this observation, we reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin slides of the validation cohort and annotated the presence of squamous differentiation. We found that squamous differentiation was more frequent in samples harboring

CTNNB1 mutation compared to WT controls (

Figure 2). Among the six

CTNNB1 mutated tumors, five (83%) showed squamous differentiation, in contrast to the 58% of WT samples (7 out of 12) (Fisher exact test = 0.6). Similarly, in the validation cohort, among the 36 evaluable CTNNNB1 WT cases, 20 (56%) showed squamous differentiation. Conversely, 17 out of the 23 cases exhibiting

CTNNB1 mutations (74%) showed this morphologic characteristic (Fisher exact test = 0.179).

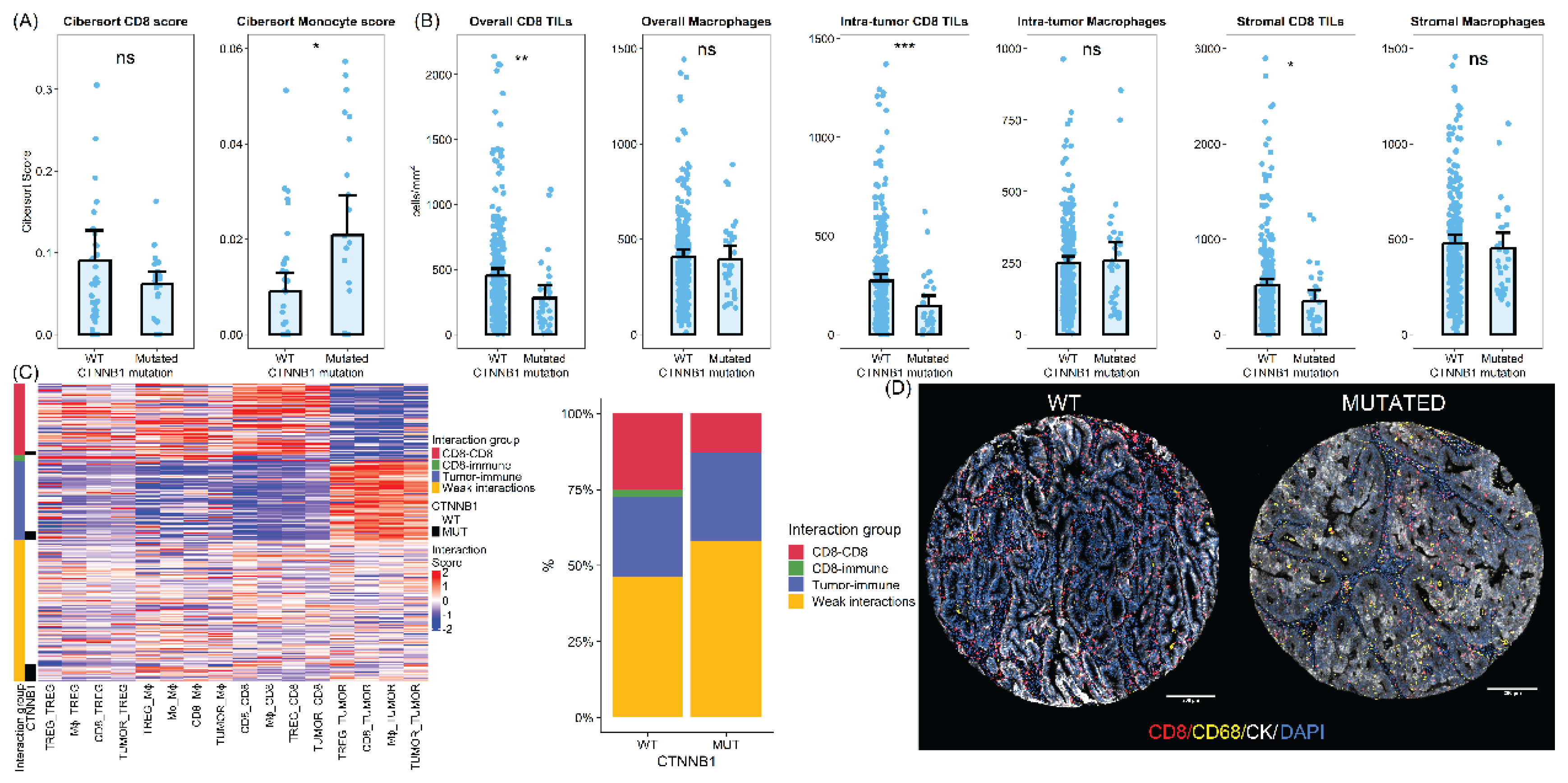

3.4. CTNNB1 Mutated Tumors Show Differences in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment

Most of the differentially activated pathways were associated with immune response regulation. Differentially downregulated pathways were associated with a variety of immune regulation processes.

In this sense, we identified that

CTNNB1 mutated samples were associated with downregulation of IL-1 production pathways. Therefore, to further explore this finding, we analyzed the mRNA expression level of IL1 pathway related interleukins and receptors using the validation RNAseq dataset. We found that compared to

CTNNB1 WT carcinomas, samples harboring

CTNNB1 mutations showed significantly decreased levels of IL1A (p value = 0.045), IL1B (p value = 0.12), and caspase 1 (p value = 0.037) (

Supplementary Figure S1), while demonstrating similar IL1R1 and IL1R2 expression levels.

Additionally, we observed downregulation of leukocyte transendothelial migration and leukocyte cell-cell adhesion pathways. Consistent with this result, major cell adhesion molecules were found to be downregulated at the transcriptomic level. Specifically, we found that

CTNNB1 mutated carcinomas showed significantly downregulated levels of ITGAL, ITGAM, and ITGB2, which are involved in leukocyte transendothelial migration. Finally, several pathways associated with lymphocyte functions, including T cell receptor (TCR) signaling regulation and lymphocyte activation, were dysregulated. Accordingly, key members of the TCR signaling pathway, like CD3E and NFKB1, were significantly downregulated in

CTNNB1 mutated tumors. Moreover, INF-gamma mRNA expression level also showed a non-significant downregulated profile in

CTNNB1 mutated samples (

Supplementary Figure S1).

To further investigate the differences in the immune profile between

CTNNB1 mutated and WT samples, we assessed different immune populations in the validation cohort deconvoluting the transcriptomic data using the CIBERSORT algorithm. We identified a net enrichment of the myeloid monocyte population in

CTNNB1 mutated samples (average CIBERSORT score 0.02 Vs 0.009, two-sided t-test = 0.016). On the other hand, CD8 T cells were less abundant in

CTNNB1 mutated tumors compared to WT samples although this difference did not reach statistical significance (average CIBERSORT score 0.061 Vs 0.09, two-sided t-test = 0.16) (

Figure 3).

Additionally, we analyzed a large cohort of low-grade early-stage endometrial carcinomas. A total of 303 tissue cores (31 cores from

CTNNB1 mutated and 272 cores from WT tumors) from 176 patients were evaluated using quantitative immunofluorescence. On average,

CTNNB1-mutated tumors exhibited lower CD8 cell density (452 vs 280 CD8 cells per mm

2, two-sided t-test p-value < 0.01). This lower CD8 infiltration in

CTNNB1 mutated samples was consistent across both intratumoral and stromal compartments (two-sided t-test p-value <0.001 for intratumor CD8 TILs and 0.013 for stromal TILs). In addition, we found a slight but non-significant increase in CD68 positive macrophages in the tumoral compartment with no differences in the stromal compartment (

Figure 3).

To further understand immune microenvironment differences between

CTNNB1 mutated and wild-type tumors we analyzed spatial interaction patterns. We observed different patterns of homotypic and heterotypic cell-cell interaction between samples. After clustering, we identified four groups of samples according to cell-cell interaction patterns. The most common pattern of cell-cell interaction was characterized by weak spatial interactions (low spatial clustering overall) and was therefore termed weak interaction patterns. It was the most frequently found pattern in both

CTNNB1 mutated and wild-type samples. However,

CTNNB1 samples were enriched in these spatial interaction patterns, with more than 50% of samples being classified as weakly interactive. The second spatial interaction pattern was enriched in immune cells spatially interacting with tumor cells and tumor cells showing homotypic interactions. Therefore, we labelled these samples as Tumor-immune interactions. These samples were equally found in both types of samples. Finally, we identified two additional clusters enriched in homotypic and heterotypic interactions between immune cells. These clusters represented more than 25% of

CTNNB1 WT tumors but were only rarely seen in their mutated counterparts (13%) (Fisher exact test p value = 0.46) (

Figure 3).

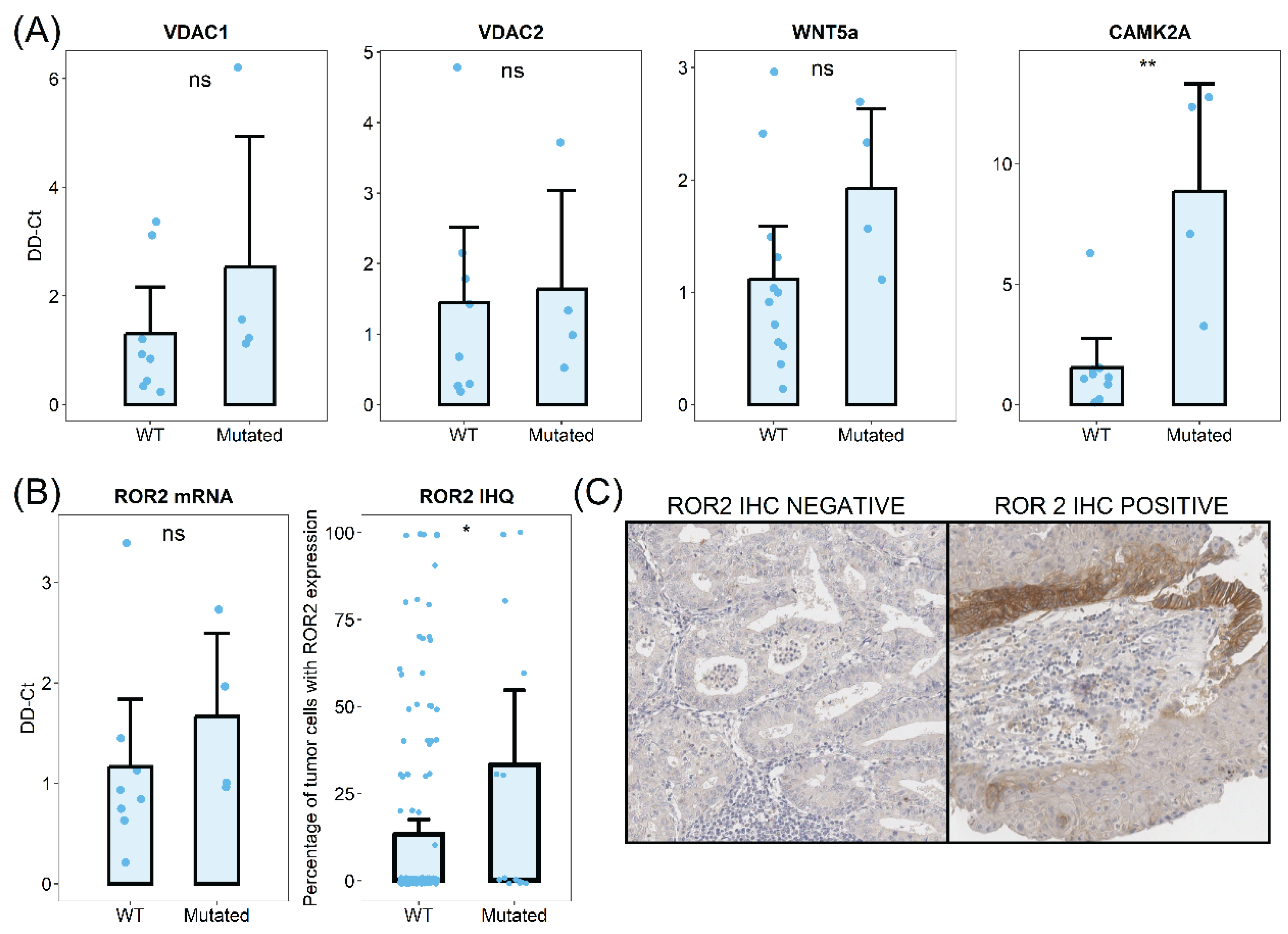

3.5. CTNNB1 Mutated Tumors Show Dysregulation of Intracellular Calcium and Calcium Dependent Wnt Pathway Signaling

Six of the differentially activated pathways were associated with cytosolic calcium homeostasis. We identified anion channels and transporter-related pathways as consistently dysregulated in

CTNNB1 mutated tumors. Given that our differential protein expression analysis identified mitochondrial anion channels VDAC1 and VDAC3 as two of the most upregulated proteins in

CTNNB1 mutated samples, we first validated this upregulation using qPCR analysis. We analyzed discovery cohort samples and observed an increase of VDAC1 mRNA levels in

CTNNB1 mutated samples and a moderate increase of VDAC2 mRNA levels (

Figure 4).

We hypothesized that the dysregulation of cytosolic calcium regulation could be involved in Wnt signaling through non-canonical pathways, including Wnt/Ca

2+. To evaluate this hypothesis, we analyzed the mRNA levels of Wnt/Ca

2+ related mediators by qPCR on FFPE tissue samples.The primary ligand of Wnt/Ca

2+ receptor, Wnt5a, was upregulated in

CTNNB1 mutated tumors (

Figure 4). The transmembrane signaling transductor ROR2 also showed increased levels in samples with β-catenin mutations (

Figure 4). Finally, the Calcium Calmodulin Kinase II, which plays a key role in signal transduction, was also upregulated in

CTNNB1 mutated tumors. To further investigate these findings, we analyzed the ROR2 expression in a large cohort of low-grade early-stage endometrial carcinomas (150 samples from

CTNNB1 wild-type tumors and 15 from mutated counterparts). ROR2 immunohistochemistry revealed increased higher protein expression levels in

CTNNB1 mutated samples. On average,

CTNNB1 mutated tumors showed 33.3% of ROR2 positive cells, while only 13.3% of WT tumor cells showed ROR2 positivity.

4. Discussion

β-catenin mutations have been observed in a variety of malignancies. The activation of the Wnt pathway in malignant tumors has been demonstrated to be a critical factor in the promotion of tumor growth, migration, and metastasis [

11,

13]. Although the prognostic impact of

CTNNB1 mutations in low-grade early-stage endometrial carcinoma has already been described [

9,

10], the biological mechanisms underlying the aggressive behavior of these tumors remain incompletely understood. In this study, we investigate the proteome of low-grade early-stage endometrial carcinomas to explore the biologic impact of

CTNNB1 mutations.

We observed here a marked dysregulation of cell differentiation processes in

CTNNB1 mutated endometrial tumors. Specifically, tumor harboring mutations in β-catenin gene showed increased activity of squamous differentiation pathways. The formation of immature squamous morules has been previously described in endometrial carcinomas [

33,

34]. Squamous differentiation is a characteristic observed in various non-squamous epithelial neoplasms, including urothelial and breast carcinomas, and is usually associated with poor prognosis or advanced tumor stages [

35,

36]. Although there are some conflicting results, the significance of squamous differentiation in endometrial carcinomas has also been proposed as an adverse prognostic factor [

37,

38]. Our findings support the idea that Wnt pathway activation may contribute to a more aggressive phenotype in low-grade early-stage carcinomas by promoting squamous differentiation.

Additionally, we found that

CTNNB1 mutated tumors are associated with singular immune microenvironment features. Tumor specific immune response is supposed to influence the biological behavior of carcinomas [

39], and previous studies have highlighted the prognostic relevance of immune infiltration profiles in low-grade early-stage carcinomas [

30]. Wnt pathway activation has been previously linked with an immunosuppressive microenvironment [

14,

40]. Tumors showing alterations in Wnt pathway are on average less infiltrated by lymphocytes. Furthermore, previous reports have indicated that tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are deficiently primed by antigen presenting cells in

CTNNB1 mutated animal tumor models [

40]. Our findings are in line with previously published papers. We have found that the immune microenvironment of low-grade early-stage endometrial carcinomas is characterized by dysregulation of pathways associated with cytokine secretion, leukocyte migration, and lymphocyte activation. Further, these tumors showed an overall decrease in the number of CD8+ lymphocytes and increased myeloid cells. Furthermore, our spatial interaction analyses have revealed that

CTNNB1 mutated tumors exhibit not only a decrease in CD8+ infiltrating lymphocytes, but also distinct spatial interaction patterns compared to their WT counterparts. We have seen that

CTNNB1 mutated tumors show lower CD8 homotypic interactions, as well as heterotypic interactions with other immune cells. This diminished spatial interaction pattern could be associated with the lower T cell activation that has been described in these tumors. Overall, these findings support the notion that

CTNNB1 mutated endometrial carcinomas adopt a more aggressive phenotype due to enhance immune evasion mechanisms. Our results suggest that immunotherapy approaches aimed at low-grade early-stage carcinomas should consider

CTNNB1 mutation status when developing treatment strategies.

Furthermore, we have observed an association between

CTNNB1 mutations and elevated calcium ion transport,and Wnt/Ca²⁺ pathway activity. Canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation is mediated by interaction of Wnt ligands with Frizzled receptors, leading to the translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus. On the other hand, Wnt/Ca

2+ pathway activation is dependent on Wnt5a signaling, ROR1, and ROR2 activation, and subsequent increase in cytosolic calcium levels [

41,

42,

43] . However, the interdependence between these two pathways remains an area of active research. In the present work, we identified a potential connection between Wnt/β-catenin and Wnt/Ca

2+ signaling pathways. Our findings are supported by previously published works [

44] that have described calcium as a key mediator for β-catenin nuclear entry. These interaction favors the signaling capacity of

CTNNB1 and increases the activity of the Wnt pathway. Furthermore, other authors have found that tumors with

CTNNB1 mutation that show nuclear protein translocation have higher mRNA expression levels of Trop2, a protein known to regulate intracellular calcium levels [

45]. As the inhibition of Wnt pathway signaling is a promising therapeutic approach [

46], our findings suggest that inhibition of Wnt/Ca

2+ pathway could improve the therapeutic potential of Wnt signaling inhibition. In addition, recent studies suggest a connection between intracellular calcium regulating protein expression and tumor immune microenvironment through INF-gamma signaling regulation [

47]. This suggests a potential connection between

CTNNB1 mutation, and the immune microenvironment and calcium dysregulation found in the present study. Further studies are needed to validate the biological interplay between these two pathways.

5. Conclusions

The tumor proteome of CTNNB1 mutated low-grade early-stage carcinomas differs from their WT counterparts. Proteome dysregulation is associated with several key biological pathways including squamous differentiation, immune evasion and cell calcium homeostasis regulation. Our results support the idea that CTNNB1 mutations have an impact on the biological behavior of these tumors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Figure S1: mRNA expression according to validation RNAseq data for CTNNB1 mutated and WT tumors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization ALJ, IRC, APG, and DH; methodology ALJ and APG; formal analysis ALJ, EB, RA, CdA; resources DH; data curation ALJ; writing—original draft preparation ALJ, APG, DH; writing—review and editing IRC, EB, RA, CdA, AB, LY, RBM, AMC, VdR, MM, VHS, and AR; funding acquisition APG, DH. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) (PI21/00920), co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund ‘A way to achieve Europe’ (FEDER).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee of University Hospital La Paz (protocol code HULP: PI-3108, 28 February 2018).

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD068004.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted using the IdiPAZ Biobank Resource, which we thank for its excellent technical support

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TMA |

Tissue MicroArray |

| GO |

Gene Ontology |

| GSEA |

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| MIF |

Multiplex Immuno Fluorescence |

| TILs |

Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes |

| WT |

Wild-Type |

References

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Piñeros M, Znaor A, et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. [Internet]. International Agency for Research on Cancer; [cited 2023 Aug 3]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today.

- Jeppesen MM, Jensen PT, Gilså Hansen D, Iachina M, Mogensen O. The nature of early-stage endometrial cancer recurrence—A national cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2016 Dec;69:51–60. [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013 May 2;497(7447):67–73.

- Kommoss S, McConechy MK, Kommoss F, Leung S, Bunz A, Magrill J, et al. Final validation of the ProMisE molecular classifier for endometrial carcinoma in a large population-based case series. Ann Oncol. 2018 May;29(5):1180–8. [CrossRef]

- Trovik J, Wik E, Werner HMJ, Krakstad C, Helland H, Vandenput I, et al. Hormone receptor loss in endometrial carcinoma curettage predicts lymph node metastasis and poor outcome in prospective multicentre trial. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 2013 Nov;49(16):3431–41. [CrossRef]

- Asano H, Hatanaka KC, Matsuoka R, Dong P, Mitamura T, Konno Y, et al. L1CAM Predicts Adverse Outcomes in Patients with Endometrial Cancer Undergoing Full Lymphadenectomy and Adjuvant Chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020 July;27(7):2159–68. [CrossRef]

- Ramon-Patino JL, Ruz-Caracuel I, Heredia-Soto V, Garcia de la Calle LE, Zagidullin B, Wang Y, et al. Prognosis Stratification Tools in Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer: Could We Improve Their Accuracy? Cancers. 2022 Feb 12;14(4):912. [CrossRef]

- Jamieson A, Huvila J, Chiu D, Thompson EF, Scott S, Salvador S, et al. Grade and Estrogen Receptor Expression Identify a Subset of No Specific Molecular Profile Endometrial Carcinomas at a Very Low Risk of Disease-Specific Death. Mod Pathol. 2023 Apr;36(4):100085.

- Costigan DC, Dong F, Nucci MR, Howitt BE. Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical Correlates of CTNNB1 Mutated Endometrial Endometrioid Carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol Off J Int Soc Gynecol Pathol. 2020 Mar;39(2):119–27. [CrossRef]

- Ruz-Caracuel I, López-Janeiro Á, Heredia-Soto V, Ramón-Patino JL, Yébenes L, Berjón A, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognostic significance of CTNNB1 mutation in low-grade, early-stage endometrial endometrioid carcinoma. Virchows Arch Int J Pathol. 2021 Dec;479(6):1167–76. [CrossRef]

- Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2017 Mar;36(11):1461–73.

- McMellen A, Woodruff ER, Corr BR, Bitler BG, Moroney MR. Wnt Signaling in Gynecologic Malignancies. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 June 16;21(12):4272. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Que H, Li Q, Wei X. Wnt/β-catenin mediated signaling pathways in cancer: recent advances, and applications in cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2025 June 10;24(1):171. [CrossRef]

- Luke JJ, Bao R, Sweis RF, Spranger S, Gajewski TF. WNT/β-catenin Pathway Activation Correlates with Immune Exclusion across Human Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2019 May 15;25(10):3074–83.

- Xue W, Yang L, Chen C, Ashrafizadeh M, Tian Y, Sun R. Wnt/β-catenin-driven EMT regulation in human cancers. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2024 Feb 9;81(1):79. [CrossRef]

- He K, Gan WJ. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in the Development and Progression of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2023;15:435–48. [CrossRef]

- Xie J, Huang L, Lu YG, Zheng DL. Roles of the Wnt Signaling Pathway in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front Mol Biosci. 2021 Jan 5;7:590912. [CrossRef]

- Nakatani Y, Masudo K, Miyagi Y, Inayama Y, Kawano N, Tanaka Y, et al. Aberrant nuclear localization and gene mutation of beta-catenin in low-grade adenocarcinoma of fetal lung type: up-regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway may be a common denominator for the development of tumors that form morules. Mod Pathol Off J U S Can Acad Pathol Inc. 2002 June;15(6):617–24. [CrossRef]

- Lawrie LC, Fothergill JE, Murray GI. Spot the differences: proteomics in cancer research. Lancet Oncol. 2001 May;2(5):270–7. [CrossRef]

- Dou Y, Kawaler EA, Cui Zhou D, Gritsenko MA, Huang C, Blumenberg L, et al. Proteogenomic Characterization of Endometrial Carcinoma. Cell. 2020 Feb;180(4):729-748.e26.

- López-Janeiro Á, Ruz-Caracuel I, Ramón-Patino JL, De Los Ríos V, Villalba Esparza M, Berjón A, et al. Proteomic Analysis of Low-Grade, Early-Stage Endometrial Carcinoma Reveals New Dysregulated Pathways Associated with Cell Death and Cell Signaling. Cancers. 2021 Feb 14;13(4):794. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Calle A, López-Janeiro Á, Mendes ML, Perez-Hernandez D, Echevarría I, Ruz-Caracuel I, et al. In-depth quantitative proteomics analysis revealed C1GALT1 depletion in ECC-1 cells mimics an aggressive endometrial cancer phenotype observed in cancer patients with low C1GALT1 expression. Cell Oncol Dordr Neth. 2023 June;46(3):697–715. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Calle A, Garranzo-Asensio M, Poves C, Sanz R, Dziakova J, Peláez-García A, et al. In-Depth Proteomic Analysis of Paraffin-Embedded Tissue Samples from Colorectal Cancer Patients Revealed TXNDC17 and SLC8A1 as Key Proteins Associated with the Disease. J Proteome Res. 2024 Nov 1;23(11):4802–20. [CrossRef]

- Zecha J, Satpathy S, Kanashova T, Avanessian SC, Kane MH, Clauser KR, et al. TMT Labeling for the Masses: A Robust and Cost-efficient, In-solution Labeling Approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2019 July;18(7):1468–78. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Calle A, Coronel R, Garranzo-Asensio M, Solís-Fernández G, Rábano A, de Los Ríos V, et al. Proteomics analysis of prefrontal cortex of Alzheimer’s disease patients revealed dysregulated proteins in the disease and novel proteins associated with amyloid-β pathology. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2023 May 7;80(6):141. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol Y, Bandla C, Kundu DJ, Kamatchinathan S, Bai J, Hewapathirana S, et al. The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025 Jan 6;53(D1):D543–53. [CrossRef]

- Vasaikar SV, Straub P, Wang J, Zhang B. LinkedOmics: analyzing multi-omics data within and across 32 cancer types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 Jan 4;46(D1):D956–63.

- Romani C, Calza S, Todeschini P, Tassi RA, Zanotti L, Bandiera E, et al. Identification of optimal reference genes for gene expression normalization in a wide cohort of endometrioid endometrial carcinoma tissues. PloS One. 2014;9(12):e113781. [CrossRef]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001 Dec;25(4):402–8. [CrossRef]

- López-Janeiro Á, Villalba-Esparza M, Brizzi ME, Jiménez-Sánchez D, Ruz-Caracuel I, Kadioglu E, et al. The association between the tumor immune microenvironments and clinical outcome in low-grade, early-stage endometrial cancer patients. J Pathol. 2022 Dec;258(4):426–36. [CrossRef]

- https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/collection/cptac-ucec [Internet]. Cancer Imaging Archive.

- Frederic Delhoume. Very Large Image Viewer [Internet]. Available from: https://github.com/delhoume/vliv.

- Meljen VT, Mittenzwei R, Wong J, Puechl A, Whitaker R, Broadwater G, et al. Endometrial Adenocarcinomas With No Specific Molecular Profile: Morphologic Features and Molecular Alterations of “Copy-number Low” Tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2021 Nov;40(6):587–96. [CrossRef]

- Niu S, Lucas E, Molberg K, Strickland A, Wang Y, Carrick K, et al. Morules But Not Squamous Differentiation are a Reliable Indicator of CTNNB1 (β-catenin) Mutations in Endometrial Carcinoma and Precancers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022 Oct 1;46(10):1447–55. [CrossRef]

- Mitra AP, Bartsch CC, Bartsch G, Miranda G, Skinner EC, Daneshmand S. Does presence of squamous and glandular differentiation in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder at cystectomy portend poor prognosis? An intensive case-control analysis. Urol Oncol. 2014 Feb;32(2):117–27. [CrossRef]

- Li HS, Chen Y, Zhang MY, Cheng K, Zhou YW, Liu JY. Increased proportion of the squamous cell carcinoma component is associated with worse survival in resected gastric adenosquamous carcinoma: A STROBE compliant cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Sept 4;99(36):e21980.

- Andrade DAP de, da Silva VD, Matsushita G de M, de Lima MA, Vieira M de A, Andrade CEMC, et al. Squamous differentiation portends poor prognosis in low and intermediate-risk endometrioid endometrial cancer. PloS One. 2019;14(10):e0220086.

- Aslan K, Öz M, Ersak B, Müftüoğlu HK, Moraloğlu Tekin Ö, Meydanli MM. The prognostic value of squamous differentiation in endometrioid type endometrial cancer: a matched analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol J Inst Obstet Gynaecol. 2022 Apr;42(3):494–500. [CrossRef]

- van Weverwijk A, de Visser KE. Mechanisms driving the immunoregulatory function of cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023 Apr;23(4):193–215.

- Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015 July 9;523(7559):231–5. [CrossRef]

- Kühl M. The WNT/Calcium pathway: biochemical mediators, tools and future requirements. Front Biosci. 2004;9(1–3):967.

- Ford CE, Qian Ma SS, Quadir A, Ward RL. The dual role of the novel Wnt receptor tyrosine kinase, ROR2, in human carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2013 Aug 15;133(4):779–87. [CrossRef]

- Quezada MJ, Lopez-Bergami P. The signaling pathways activated by ROR1 in cancer. Cell Signal. 2023 Apr;104:110588.

- Thrasivoulou C, Millar M, Ahmed A. Activation of intracellular calcium by multiple Wnt ligands and translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus: a convergent model of Wnt/Ca2+ and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. J Biol Chem. 2013 Dec 13;288(50):35651–9.

- Parrish ML, Osborne-Frazier ML, Broaddus RR, Gladden AB. Differential Localization of β-Catenin Protein in CTNNB1 Mutant Endometrial Cancers Results in Distinct Transcriptional Profiles. Mod Pathol Off J U S Can Acad Pathol Inc. 2025 May 8;38(9):100791. [CrossRef]

- Fatima I, Barman S, Rai R, Thiel KW, Chandra V. Targeting Wnt Signaling in Endometrial Cancer. Cancers. 2021 May 13;13(10):2351. [CrossRef]

- Yuan S, Sun R, Shi H, Chapman NM, Hu H, Guy C, et al. VDAC2 loss elicits tumour destruction and inflammation for cancer therapy. Nature. 2025 Apr;640(8060):1062–71. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).