Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- The possibility of combining several cell types in one assay (e.g. epithelial and immune cells)

- The 3D spatial organization of the tissues

- The use of human-derived host cells

Materials and Methods

Mammalian Cells

OrganoPlate Seeding

Bacteria co-Culture in OrganoPlate

Cytokine Secretion

TEER Measurements

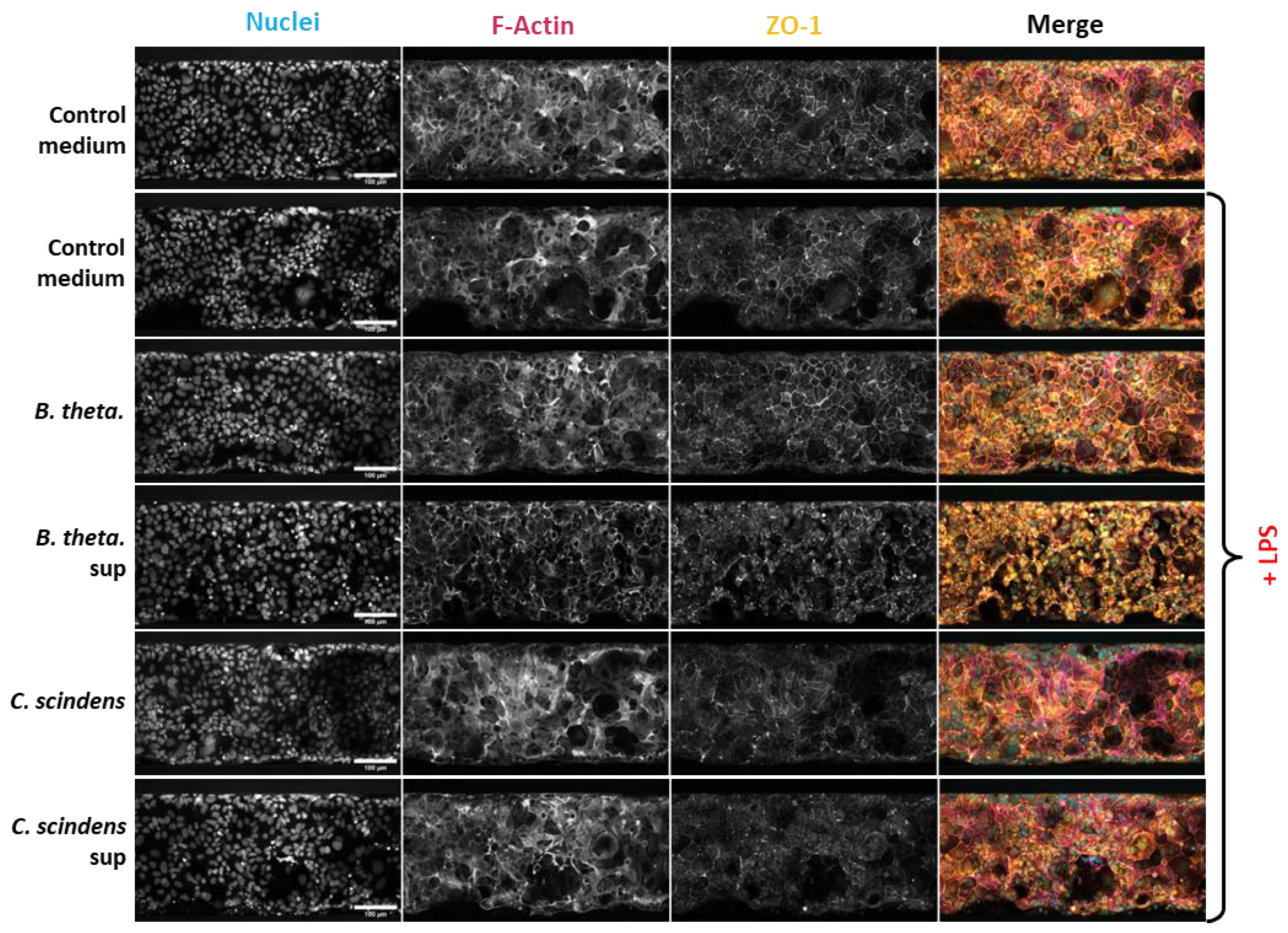

Immunohistochemistry and Microscopy

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

Figures and legends

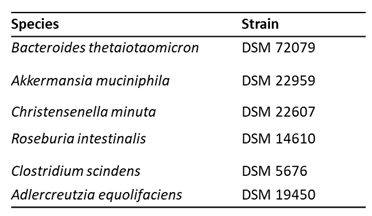

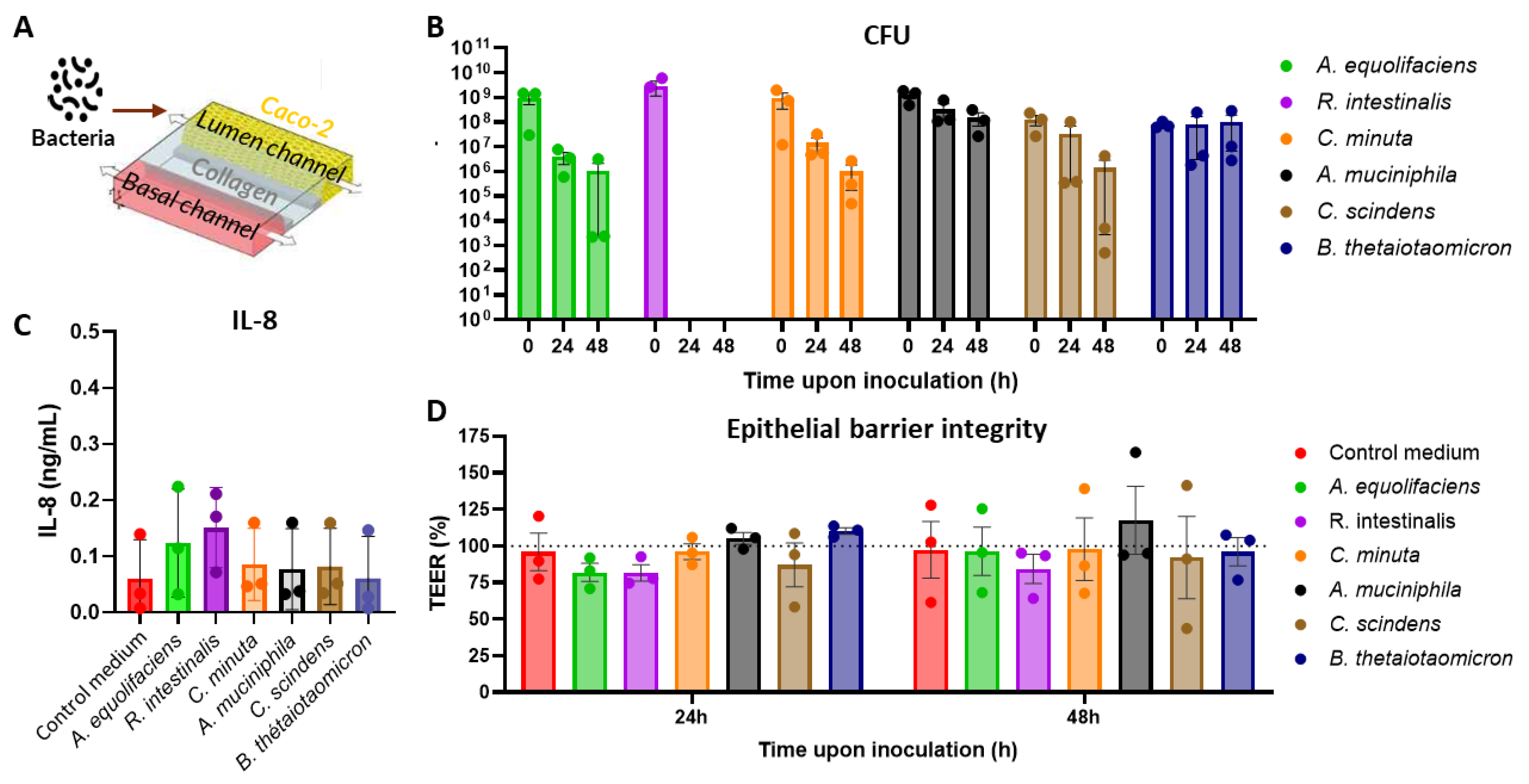

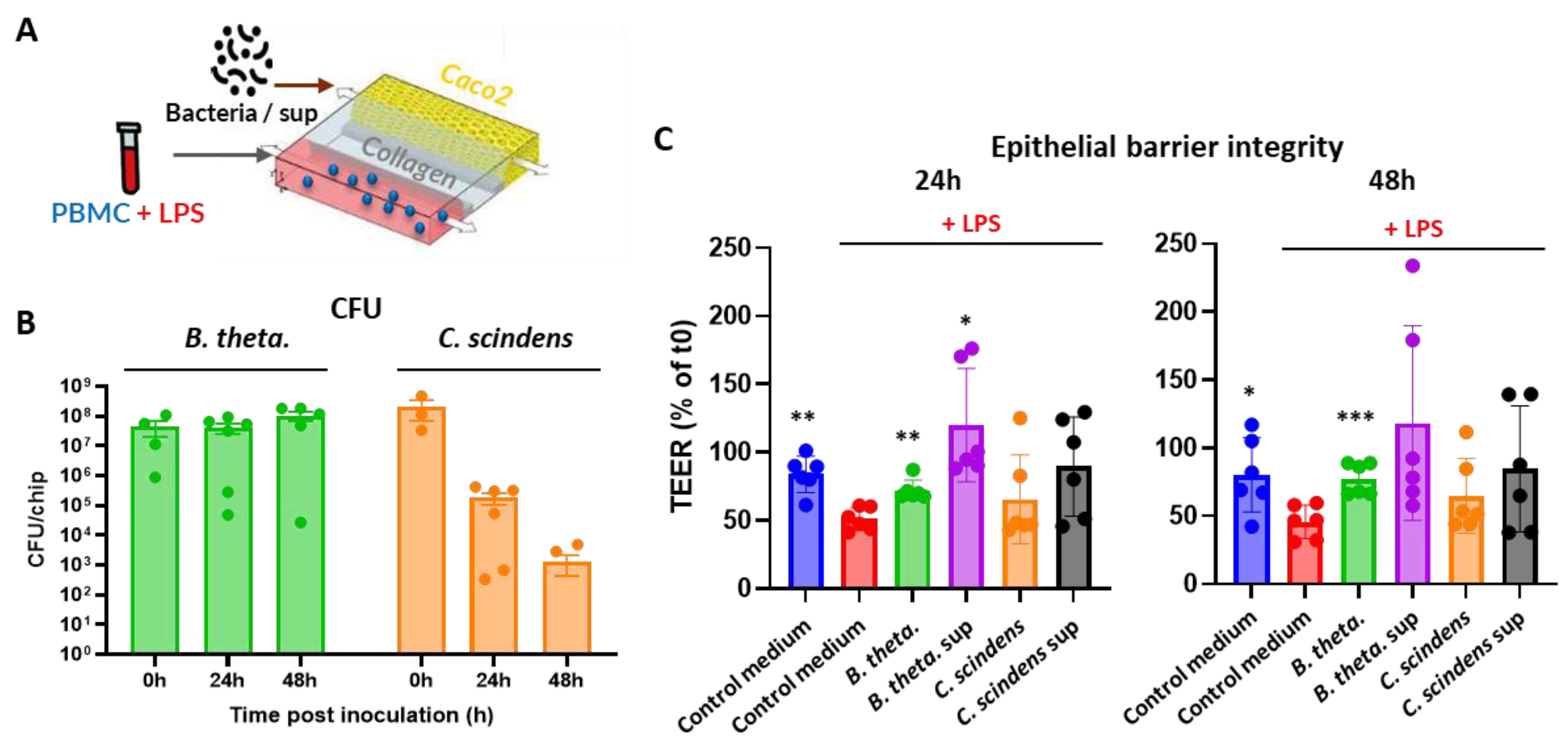

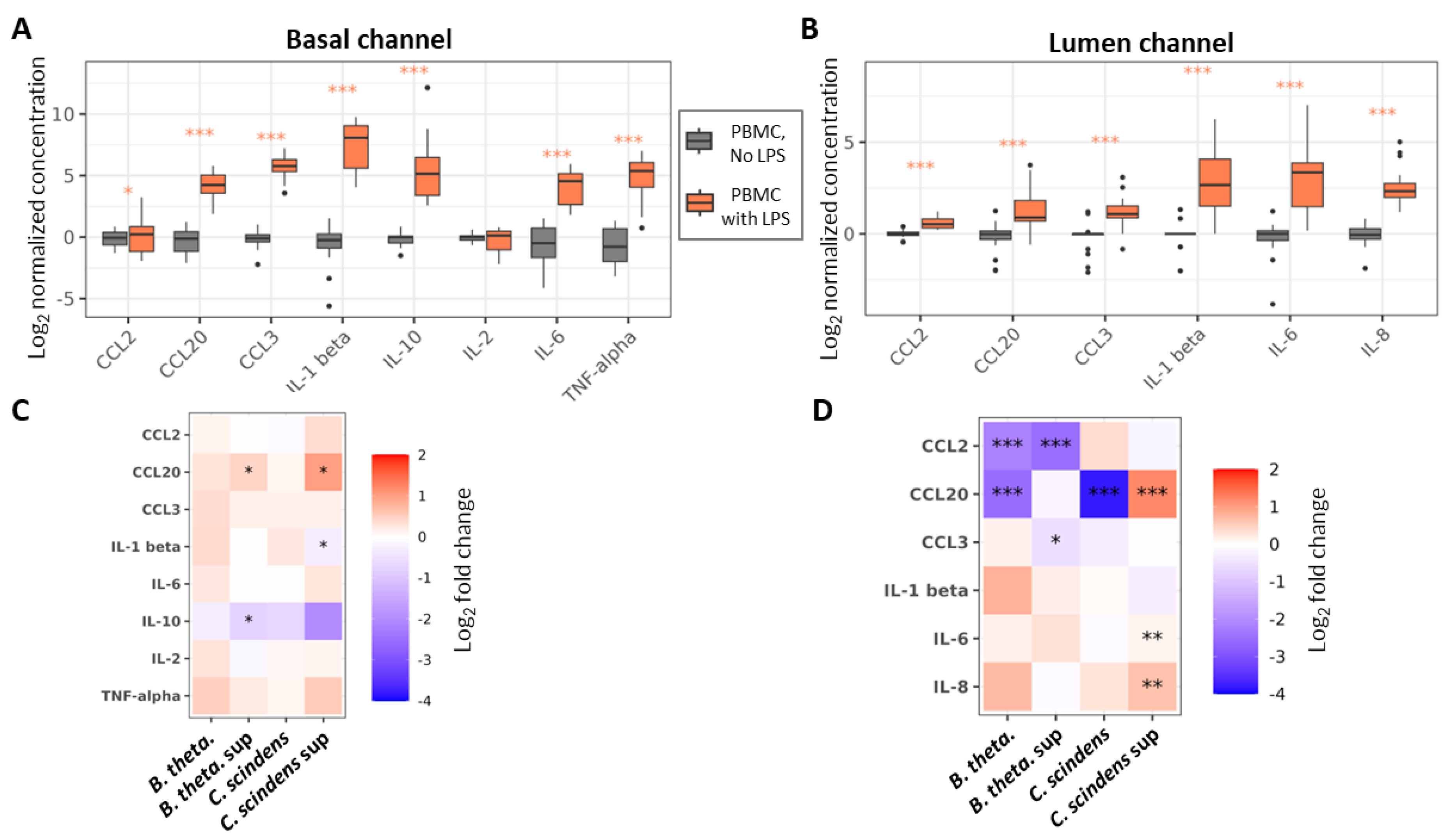

|

Conflict of interest statement

References

- Buckley A, Turner JR: Cell Biology of Tight Junction Barrier Regulation and Mucosal Disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2018, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Moonwiriyakit A, Pathomthongtaweechai N, Steinhagen PR, Chantawichitwong P, Satianrapapong W, Pongkorpsakol P: Tight junctions: from molecules to gastrointestinal diseases. Tissue barriers 2023, 11(2):2077620. [CrossRef]

- Di Tommaso N, Gasbarrini A, Ponziani FR: Intestinal Barrier in Human Health and Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18(23). [CrossRef]

- Stolfi C, Maresca C, Monteleone G, Laudisi F: Implication of Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Gut Dysbiosis and Diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Kinashi Y, Hase K: Partners in Leaky Gut Syndrome: Intestinal Dysbiosis and Autoimmunity. Front Immunol 2021, 12:673708. [CrossRef]

- Régnier M, Van Hul M, Knauf C, Cani PD: Gut microbiome, endocrine control of gut barrier function and metabolic diseases. The Journal of endocrinology 2021, 248(2):R67-r82. [CrossRef]

- Mou Y, Du Y, Zhou L, Yue J, Hu X, Liu Y, Chen S, Lin X, Zhang G, Xiao H et al: Gut Microbiota Interact With the Brain Through Systemic Chronic Inflammation: Implications on Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, and Aging. Front Immunol 2022, 13:796288. [CrossRef]

- Kayama H, Okumura R, Takeda K: Interaction Between the Microbiota, Epithelia, and Immune Cells in the Intestine. Annual review of immunology 2020, 38:23-48. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh S, Whitley CS, Haribabu B, Jala VR: Regulation of Intestinal Barrier Function by Microbial Metabolites. Cellular and molecular gastroenterology and hepatology 2021, 11(5):1463-1482. [CrossRef]

- Neurath MF: Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature Reviews Immunology 2014, 14(5):329-342.

- Barbara G, Barbaro MR, Fuschi D, Palombo M, Falangone F, Cremon C, Marasco G, Stanghellini V: Inflammatory and Microbiota-Related Regulation of the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier. Frontiers in nutrition 2021, 8:718356. [CrossRef]

- Chelakkot C, Ghim J, Ryu SH: Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Experimental & molecular medicine 2018, 50(8):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Capaldo CT, Nusrat A: Cytokine regulation of tight junctions. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2009, 1788(4):864-871.

- Martyniak A, Medyńska-Przęczek A, Wędrychowicz A, Skoczeń S, Tomasik PJ: Prebiotics, Probiotics, Synbiotics, Paraprobiotics and Postbiotic Compounds in IBD. Biomolecules 2021, 11(12). [CrossRef]

- Tsai YL, Lin TL, Chang CJ, Wu TR, Lai WF, Lu CC, Lai HC: Probiotics, prebiotics and amelioration of diseases. Journal of biomedical science 2019, 26(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Wong CH, Siah KW, Lo AW: Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. Biostatistics (Oxford, England) 2019, 20(2):273-286.

- Pocock K, Delon L, Bala V, Rao S, Priest C, Prestidge C, Thierry B: Intestine-on-a-Chip Microfluidic Model for Efficient in Vitro Screening of Oral Chemotherapeutic Uptake. ACS biomaterials science & engineering 2017, 3(6):951-959. [CrossRef]

- Chi M, Yi B, Oh S, Park DJ, Sung JH, Park S: A microfluidic cell culture device (μFCCD) to culture epithelial cells with physiological and morphological properties that mimic those of the human intestine. Biomedical microdevices 2015, 17(3):9966. [CrossRef]

- Belotserkovsky I VC, Beitz B, Ben Abdallah B, Poissonier S, Bellais S, Hesketh A, Roelens M, Meza Torres J, Mouharib M, Sunshine J, Shaffer M, Parrino J, Silverman J, COSIPOP Study group, Daillere R, Vedrine C: Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG protect intestinal epithelium against inflammation-mediated damage in an immunocompetent in-vitro model Preprint 2025.

- Beaurivage C, Naumovska E, Chang YX, Elstak ED, Nicolas A, Wouters H, van Moolenbroek G, Lanz HL, Trietsch SJ, Joore J et al: Development of a Gut-On-A-Chip Model for High Throughput Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20(22). [CrossRef]

- Gijzen L, Marescotti D, Raineri E, Nicolas A, Lanz HL, Guerrera D, van Vught R, Joore J, Vulto P, Peitsch MC et al: An Intestine-on-a-Chip Model of Plug-and-Play Modularity to Study Inflammatory Processes. SLAS TECHNOLOGY: Translating Life Sciences Innovation 2020:247263032092499. [CrossRef]

- Bounab Y, Eyer K, Dixneuf S, Rybczynska M, Chauvel C, Mistretta M, Tran T, Aymerich N, Chenon G, Llitjos JF et al: Dynamic single-cell phenotyping of immune cells using the microfluidic platform DropMap. Nature protocols 2020, 15(9):2920-2955. [CrossRef]

- Meslier V, Plaza Oñate F, Ania M, Nehlich M, Belotserkovsky I, Bellais S, Thomas V: Draft Genome Sequence of Isolate POC01, a Novel Anaerobic Member of the Oscillospiraceae Family, Isolated from Human Feces. Microbiology resource announcements 2022, 11(1):e0113421. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1995, 57(1):289-300. [CrossRef]

- Singhal R, Shah YM: Oxygen battle in the gut: Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factors in metabolic and inflammatory responses in the intestine. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2020, 295(30):10493-10505. [CrossRef]

- van Deventer SJ: Review article: Chemokine production by intestinal epithelial cells: a therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997, 11 Suppl 3:116-120; discussion 120-111.

- Vebr M, Pomahačová R, Sýkora J, Schwarz J: A Narrative Review of Cytokine Networks: Pathophysiological and Therapeutic Implications for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Pathogenesis. Biomedicines 2023, 11(12). [CrossRef]

- Delday M, Mulder I, Logan ET, Grant G: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron Ameliorates Colon Inflammation in Preclinical Models of Crohn's Disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2019, 25(1):85-96. [CrossRef]

- Luo Y, Lan C, Ren W, Wu A, Yu B, He J, Chen D: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron: A symbiotic ally against diarrhea along with modulation of gut microbial ecological networks via tryptophan metabolism and AHR-Nrf2 signaling. Journal of advanced research 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pan M, Barua N, Ip M: Mucin-degrading gut commensals isolated from healthy faecal donor suppress intestinal epithelial inflammation and regulate tight junction barrier function. Front Immunol 2022, 13:1021094. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Hao Z, Du J, Gao Y, Yang S, Zhou Y: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron relieves colon inflammation by activating aryl hydrocarbon receptor and modulating CD4(+)T cell homeostasis. International immunopharmacology 2021, 90:107183. [CrossRef]

- Buffie CG, Bucci V, Stein RR, McKenney PT, Ling L, Gobourne A, No D, Liu H, Kinnebrew M, Viale A et al: Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature 2015, 517(7533):205-208. [CrossRef]

- Abt MC, McKenney PT, Pamer EG: Clostridium difficile colitis: pathogenesis and host defence. Nature reviews Microbiology 2016, 14(10):609-620.

- Daniel SL, Ridlon JM: Clostridium scindens: history and current outlook for a keystone species in the mammalian gut involved in bile acid and steroid metabolism. FEMS microbiology reviews 2025, 49. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Huang YJ, Trapecar M, Wright C, Schneider K, Kemmitt J, Hernandez-Gordillo V, Yoon JY, Poyet M, Alm EJ et al: An immune-competent human gut microphysiological system enables inflammation-modulation by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10(1):31. [CrossRef]

- Jalili-Firoozinezhad S, Gazzaniga FS, Calamari EL, Camacho DM, Fadel CW, Bein A, Swenor B, Nestor B, Cronce MJ, Tovaglieri A et al: A complex human gut microbiome cultured in an anaerobic intestine-on-a-chip. Nature biomedical engineering 2019, 3(7):520-531.

- Marzorati M, Vanhoecke B, De Ryck T, Sadaghian Sadabad M, Pinheiro I, Possemiers S, Van den Abbeele P, Derycke L, Bracke M, Pieters J et al: The HMI module: a new tool to study the Host-Microbiota Interaction in the human gastrointestinal tract in vitro. BMC Microbiol 2014, 14:133. [CrossRef]

- Shah P, Fritz JV, Glaab E, Desai MS, Greenhalgh K, Frachet A, Niegowska M, Estes M, Jager C, Seguin-Devaux C et al: A microfluidics-based in vitro model of the gastrointestinal human-microbe interface. Nat Commun 2016, 7:11535. [CrossRef]

- Shin W, Wu A, Massidda MW, Foster C, Thomas N, Lee DW, Koh H, Ju Y, Kim J, Kim HJ: A Robust Longitudinal Co-culture of Obligate Anaerobic Gut Microbiome With Human Intestinal Epithelium in an Anoxic-Oxic Interface-on-a-Chip. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2019, 7:13. [CrossRef]

- Fofanova TY, Karandikar UC, Auchtung JM, Wilson RL, Valentin AJ, Britton RA, Grande-Allen KJ, Estes MK, Hoffman K, Ramani S et al: A novel system to culture human intestinal organoids under physiological oxygen content to study microbial-host interaction. PLoS One 2024, 19(7):e0300666. [CrossRef]

- Singh UP, Singh NP, Murphy EA, Price RL, Fayad R, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS: Chemokine and cytokine levels in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cytokine 2016, 77:44-49. [CrossRef]

- Reinecker HC, Loh EY, Ringler DJ, Mehta A, Rombeau JL, MacDermott RP: Monocyte-chemoattractant protein 1 gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells and inflammatory bowel disease mucosa. Gastroenterology 1995, 108(1):40-50. [CrossRef]

- MacDermott RP, Sanderson IR, Reinecker HC: The central role of chemokines (chemotactic cytokines) in the immunopathogenesis of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases 1998, 4(1):54-67. [CrossRef]

- Banks C, Bateman A, Payne R, Johnson P, Sheron N: Chemokine expression in IBD. Mucosal chemokine expression is unselectively increased in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. The Journal of pathology 2003, 199(1):28-35. [CrossRef]

- Meitei HT, Jadhav N, Lal G: CCR6-CCL20 axis as a therapeutic target for autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity reviews 2021, 20(7):102846. [CrossRef]

- Lee AY, Eri R, Lyons AB, Grimm MC, Korner H: CC Chemokine Ligand 20 and Its Cognate Receptor CCR6 in Mucosal T Cell Immunology and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Odd Couple or Axis of Evil? Front Immunol 2013, 4:194. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov AI, Parkos CA, Nusrat A: Cytoskeletal Regulation of Epithelial Barrier Function During Inflammation. The American journal of pathology 2010, 177(2):512-524. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).