Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

21 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model and Data

2.1. MLGEFS

2.2. GEFS

2.3. Data and Study Cases

3. Comparison of MLGEFS and GEFS

3.1. Similarities

3.1.1. Forecast Accuracy

3.1.2. Ensemble Spread

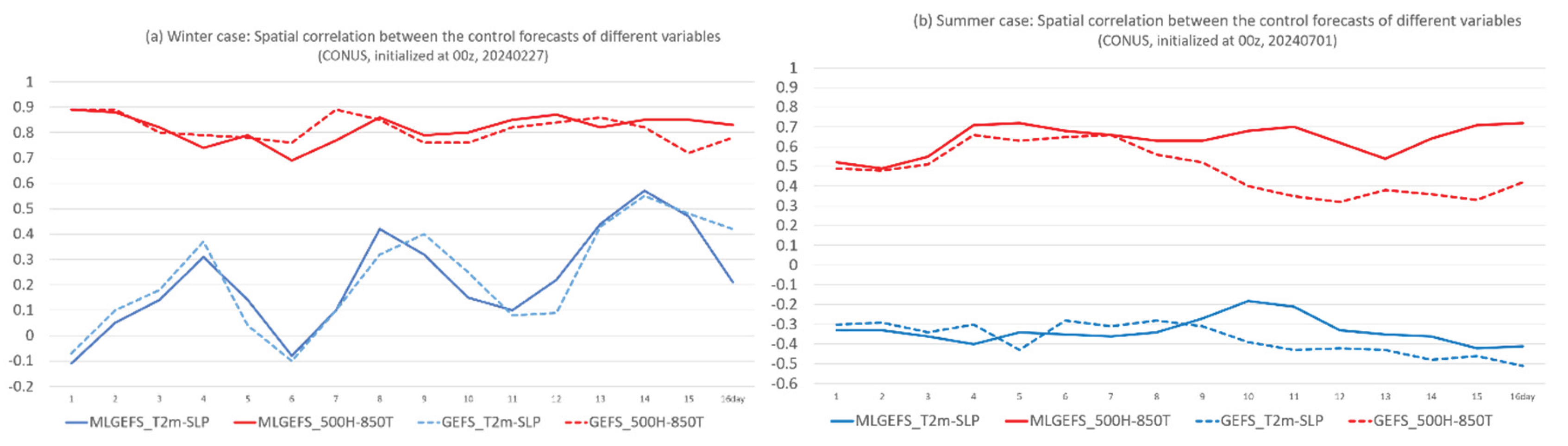

3.1.3. Inter-Variable Correlation

3.2. Differences

3.2.1. Effectiveness of Ensemble Averaging

3.2.2. Nonlinearity

3.2.3. Randomness or Chaos

3.2.4. Blurriness

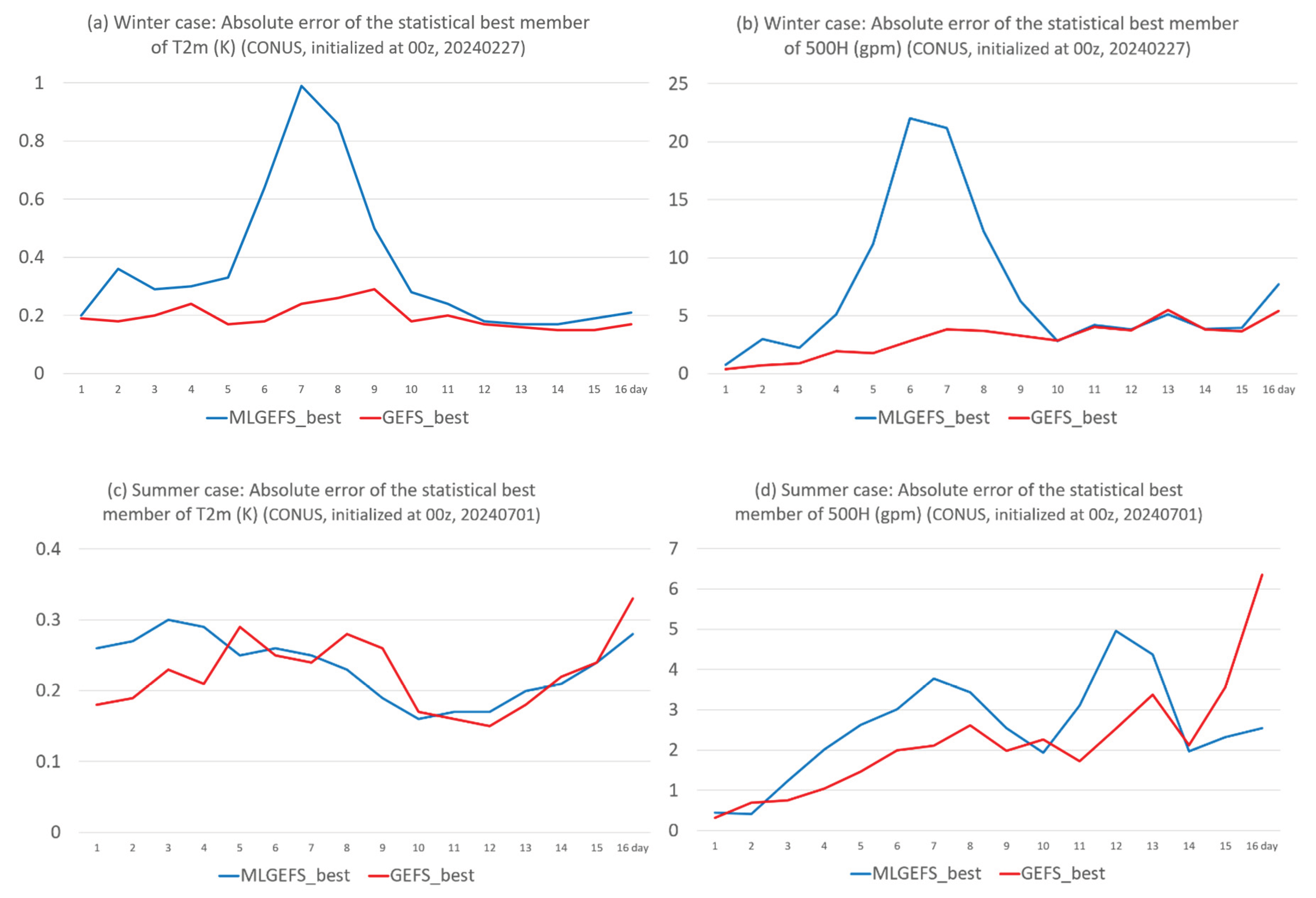

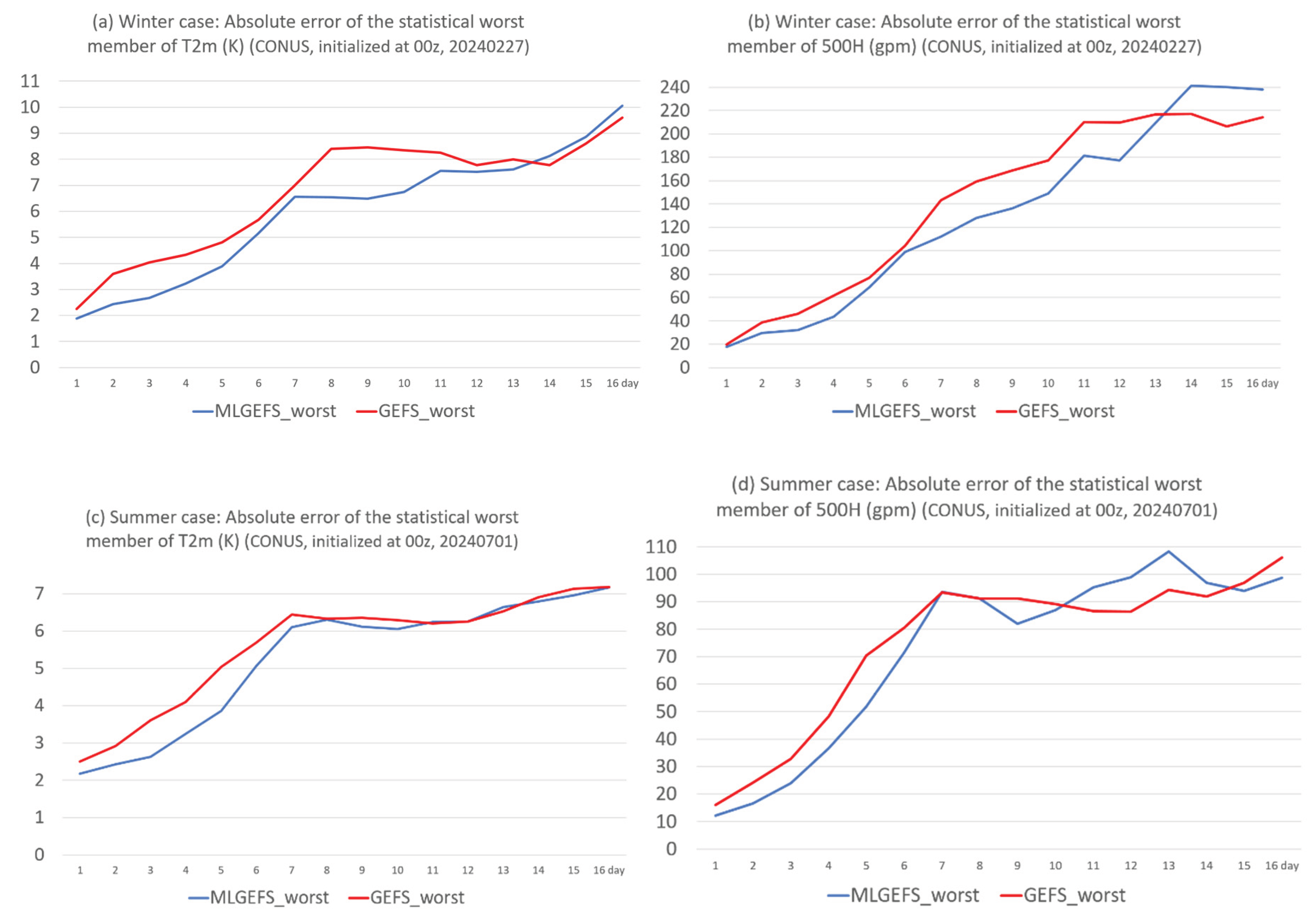

3.3. How Much Extra Information Provided by MLGEFS Beyond GEFS?

4. Summary

- (1)

- In terms of forecast accuracy (error and bias), MLGEFS performs very similarly to the physics-based model GEFS, suggesting that the AI model may have implicitly learned the internal “physics” of NWP systems by memorizing physical relationships across various synoptic scenarios during its training period. MLGEFS also exhibits fundamental meteorological behaviors—such as baroclinic and convective instabilities—comparable to those seen in GEFS. To what extent is this similarity attributable to the shared initial conditions used by both models? This remains an open question for further discussion.

- (2)

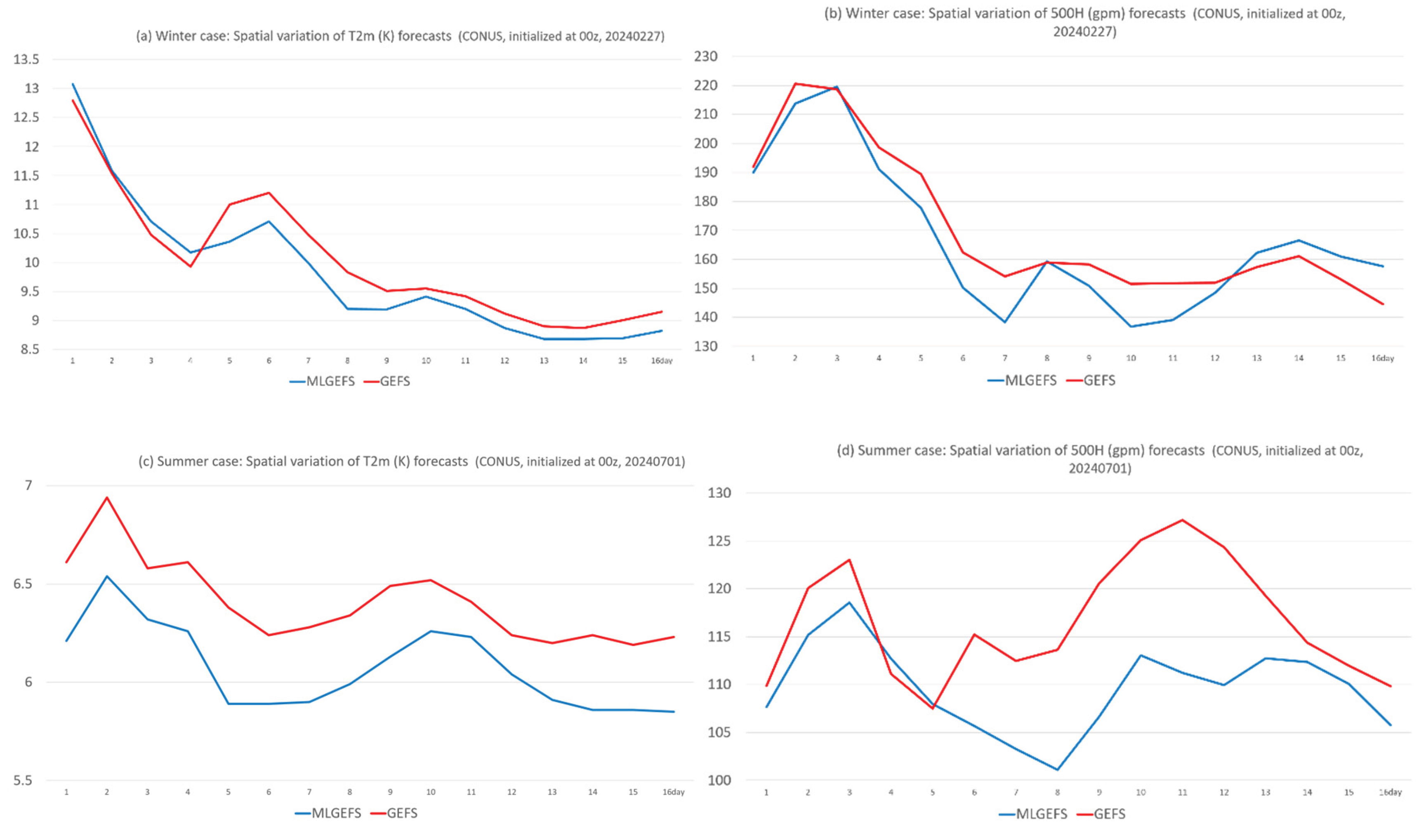

- MLGEFS exhibits a smaller ensemble spread at the beginning but gradually catches up and even surpasses that of GEFS after two weeks. The growth trend and spatial structure of MLGEFS’s ensemble spread are similar—or parallel—to those of GEFS, which may be attributed to their comparable relationships between spread and atmospheric instabilities (baroclinic and convective). Although GEFS demonstrates a quantitatively stronger spread–error relationship, particularly in the early forecast period, MLGEFS closely mirrors this behavior and even outperforms GEFS at longer lead times.

- (3)

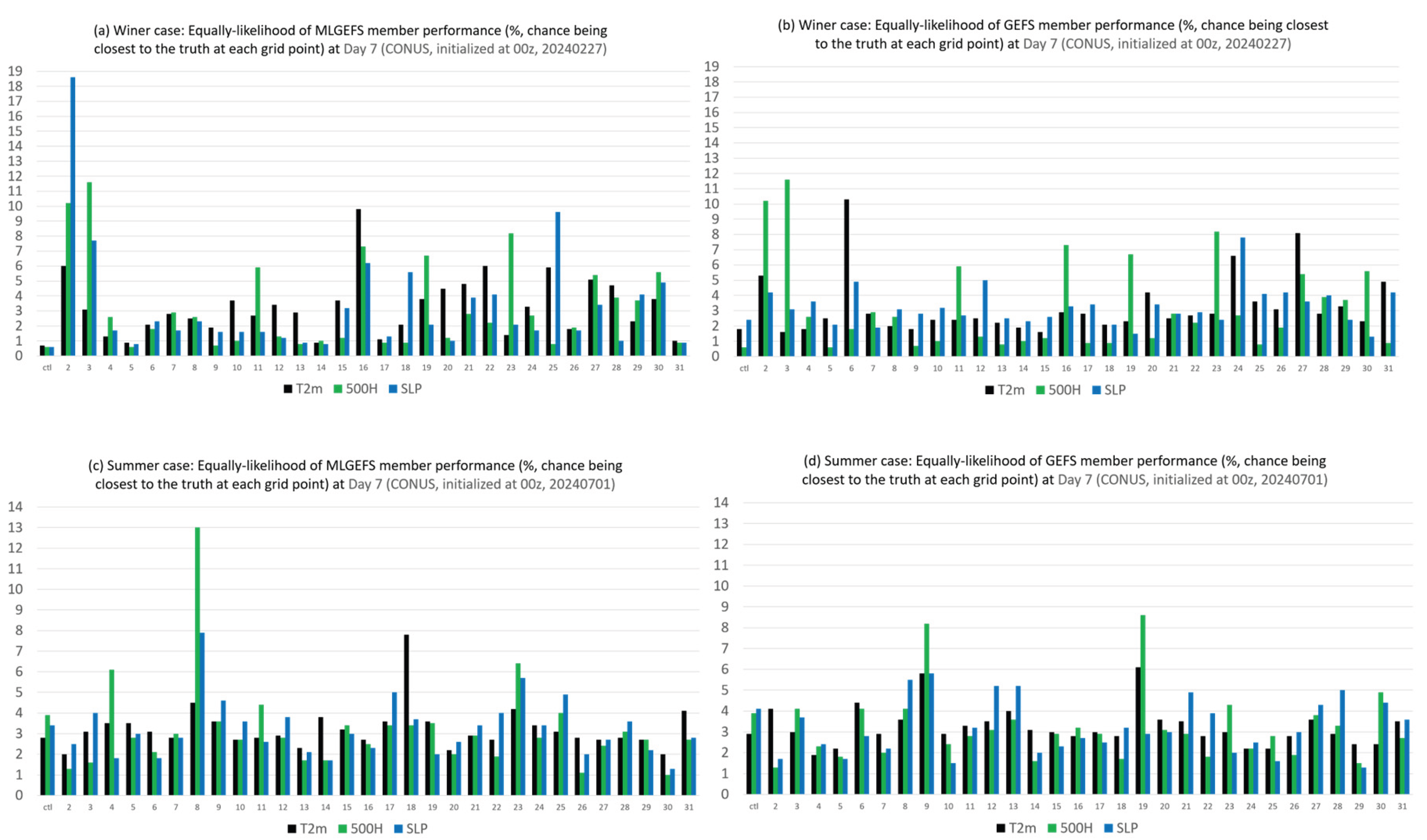

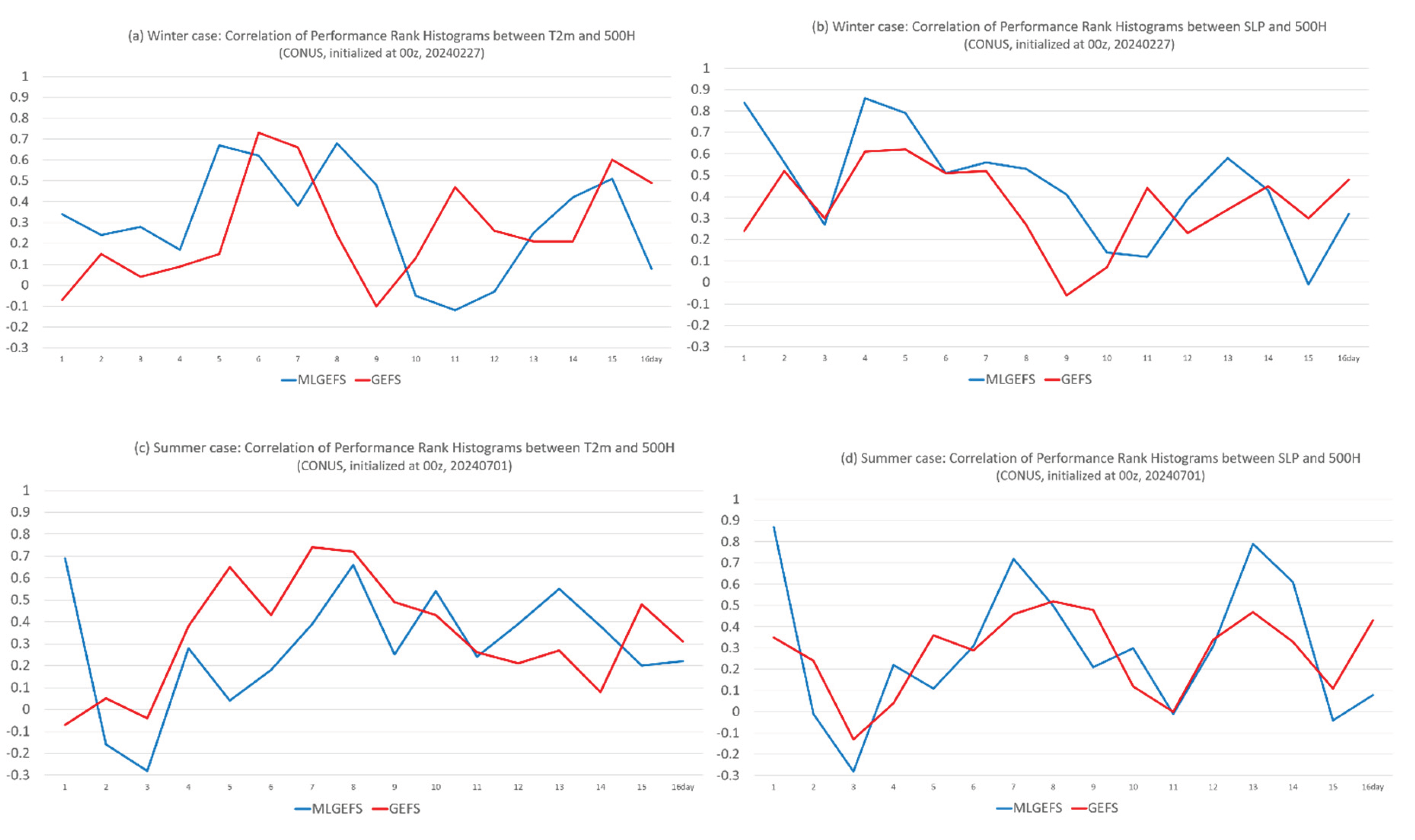

- The output variables from MLGEFS are interconnected in a manner similar to those in a physics-based model. This interconnection is observed in both single forecast settings and ensemble group forecast settings. It further suggests that the AI model may “understand” the physical relationships inherent in NWP models, rather than relying solely on linear statistical properties. A side result (the “fifth difference”) observed from the performance-rank histogram (Figure 11) is that ensemble members in MLGEFS exhibit less uniform performance compared to those in GEFS. This implies that ensemble post-processing may play a more important role in AI-based ensemble systems than in physics-based NWP ensembles.

- (4)

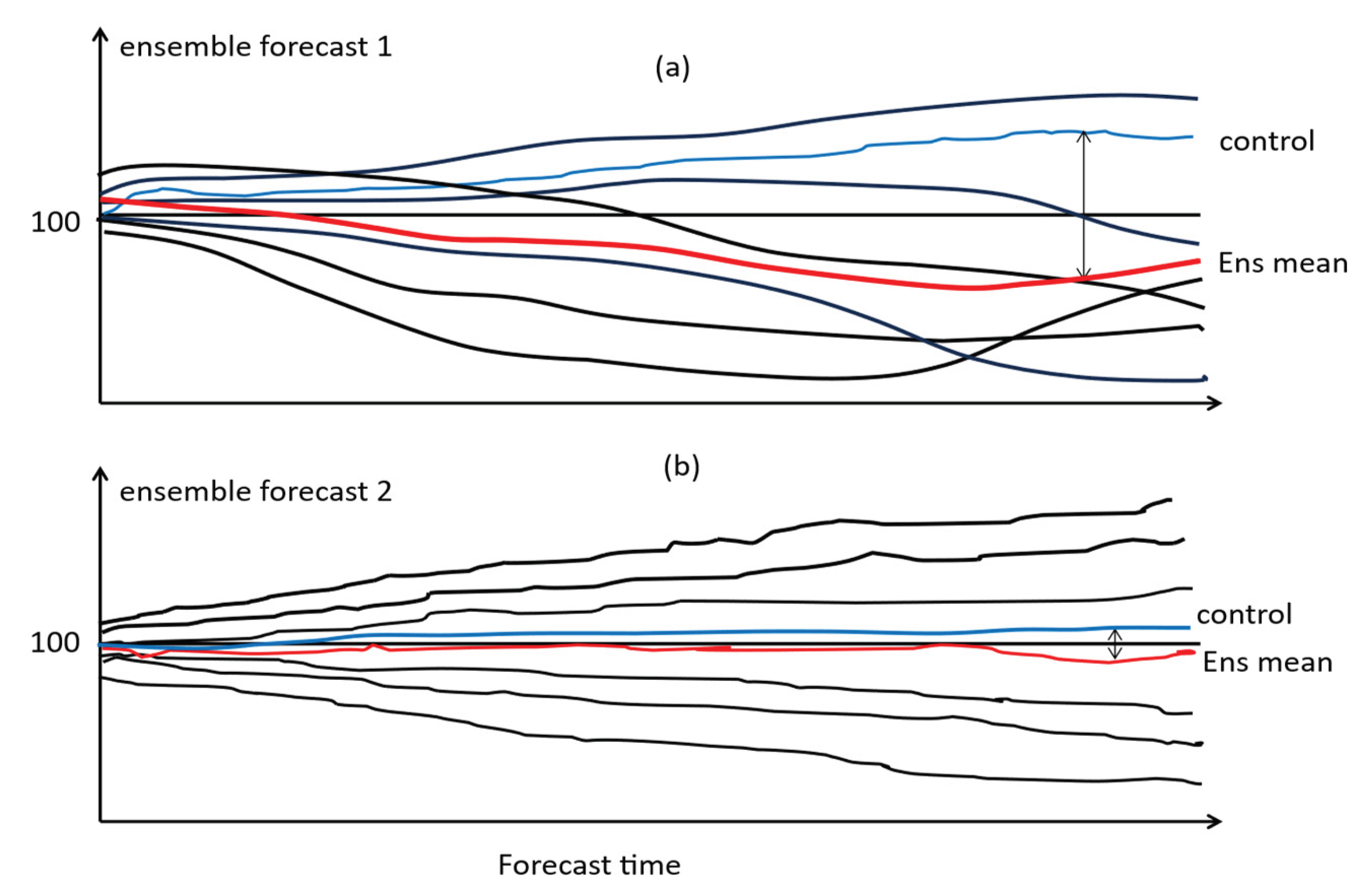

- One of the key advantages of running an ensemble weather forecast is the ability to filter out unpredictable features and improve the ensemble mean forecast through averaging across individual members. Although ensemble averaging is more effective in enhancing the ensemble mean forecast over the control forecast during the first few days, it is generally less effective in the AI-based ensemble MLGEFS compared to the physics-based ensemble GEFS. In MLGEFS, the ensemble mean forecast does not consistently outperform the control member, whereas in GEFS, it reliably does. This difference may be related to the nonlinearity characteristics of MLGEFS (see point (5) below).

- (5)

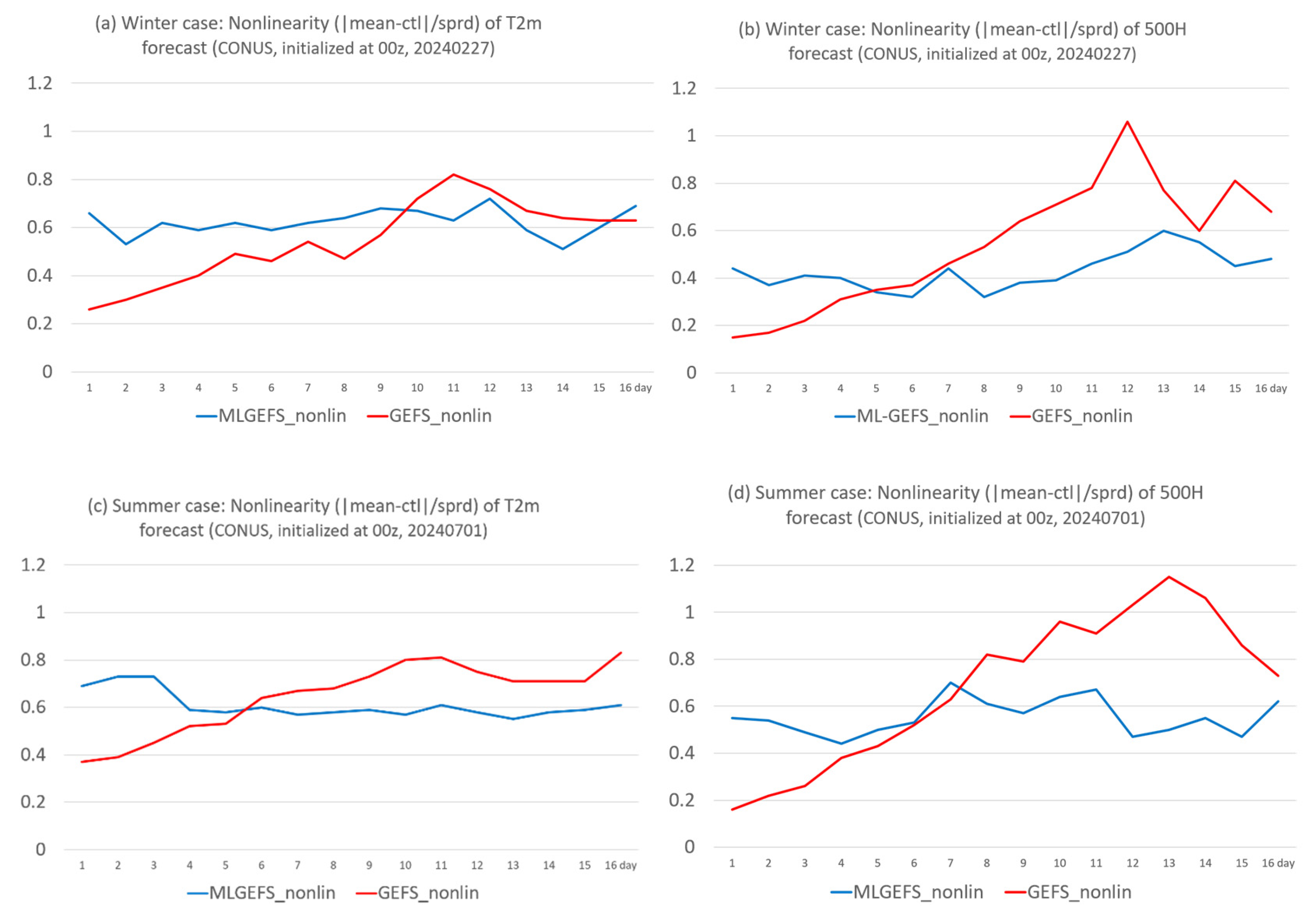

- Unlike in a physics-based model, where nonlinearity generally increases with forecast lead time and varies with flow regimes, nonlinearity in MLGEFS remains nearly constant throughout the ensemble forecast period (Days 1–16).

- (6)

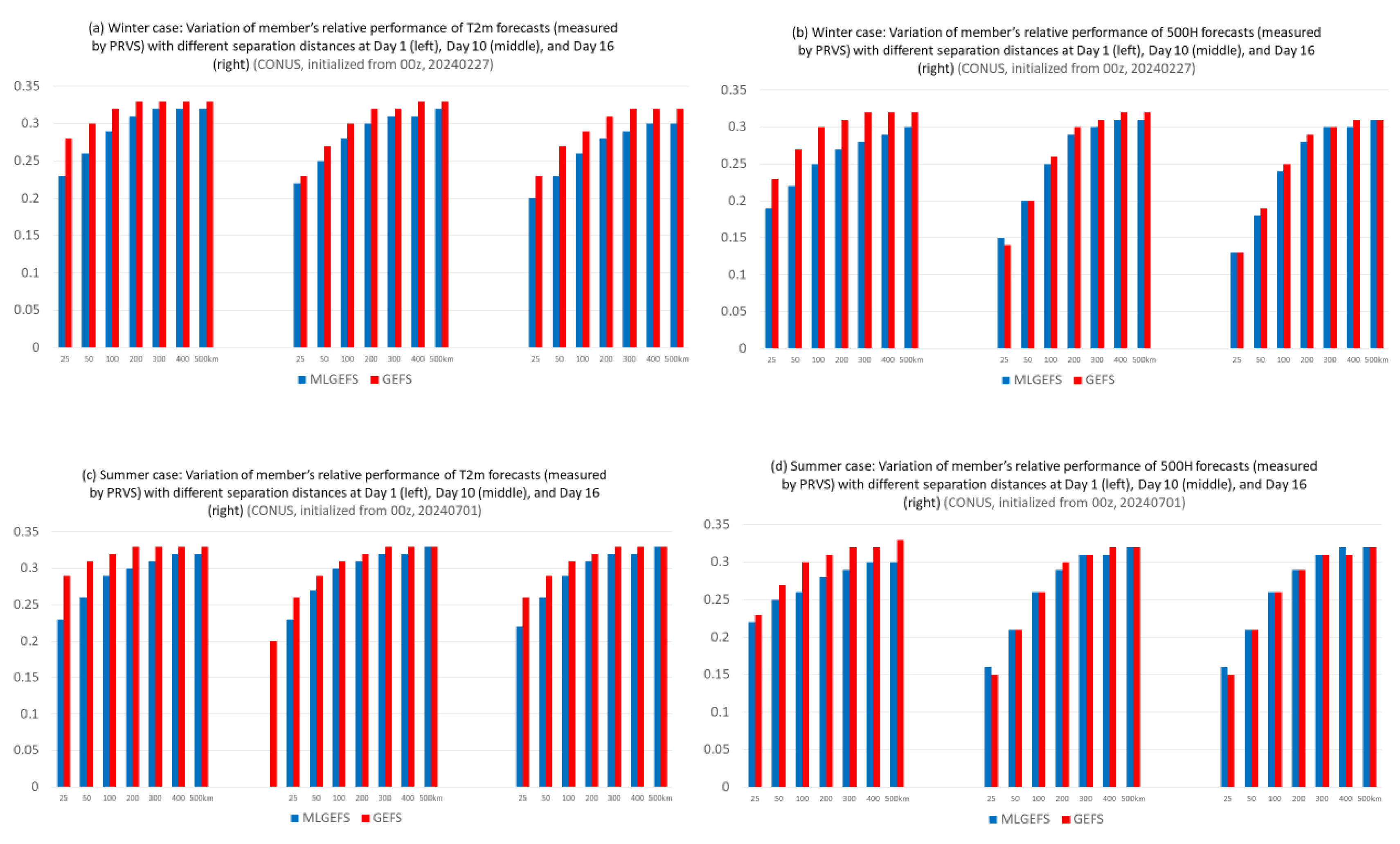

- MLGEFS exhibits a less chaotic nature than GEFS, particularly at shorter forecast lead times. The spatial variation in ensemble members’ relative performance ranks—i.e., the frequency of rank changes or “flipping”—is lower in MLGEFS than in GEFS. This may result in less uniform performance among members, with a few consistently outperforming the others. Such behavior suggests that ensemble post-processing (forecast calibration) may be even more essential for AI-based ensembles than for physics-based NWP ensembles (also see the point (3) above). A question that arises from comparing points (5) and (6) is whether the relationship between nonlinearity and chaos differs across forecasting systems like MLGEFS and GEFS. This could be a valuable topic for future research.

- (7)

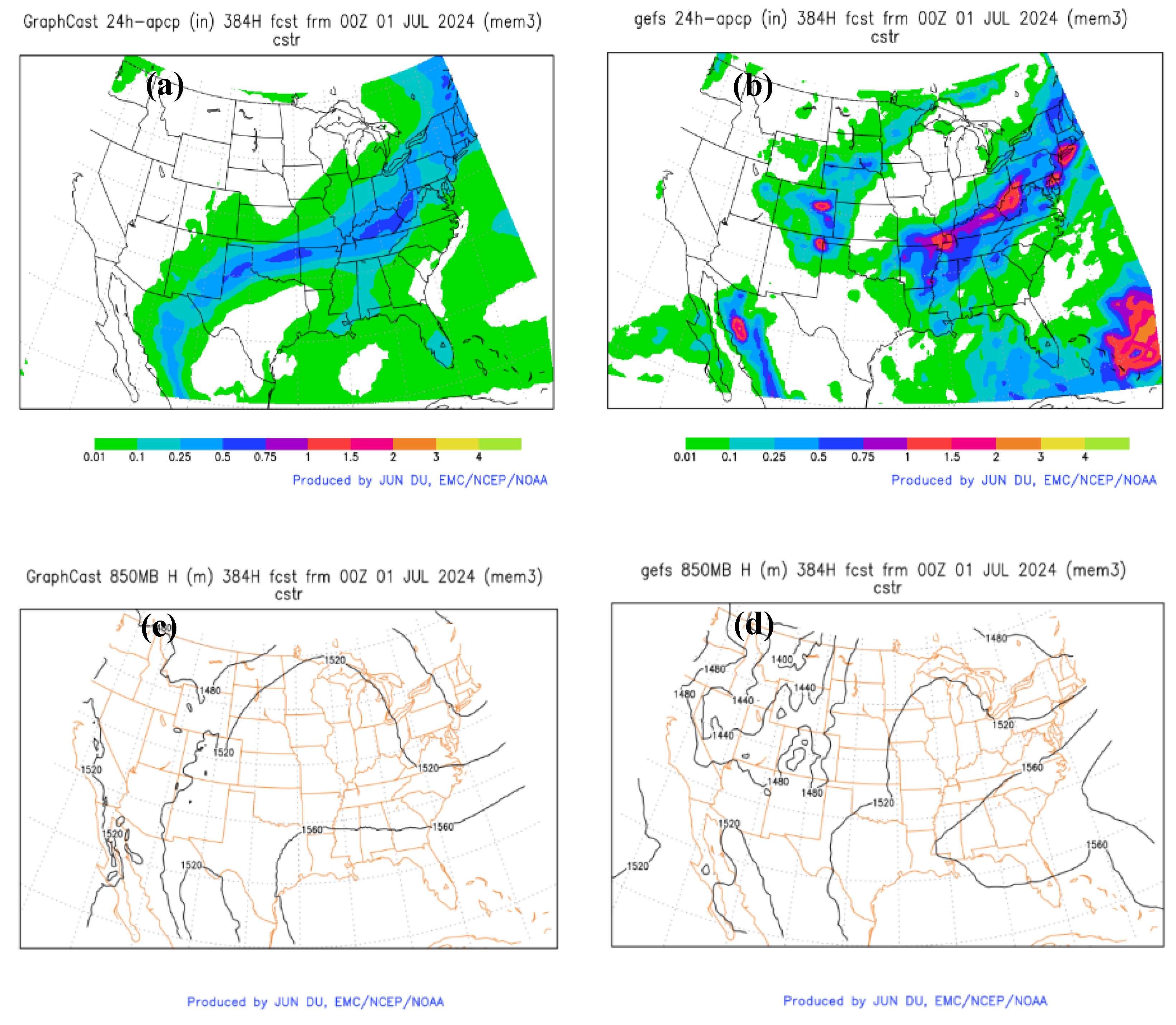

- The AI-based model MLGEFS tends to produce spatially smoother fields than the physics-based NWP model GEFS. To address this issue, improvements to the AI model architecture may be necessary—such as incorporating diffusion models—an area for AI scientists to explore further.

- (8)

- Finally, by examining the forecast errors of both the best and worst members, we investigated whether the current version of MLGEFS introduces any new forecast information beyond what GEFS already provides. Our findings suggest that MLGEFS contributes little additional forecast information—either positive or negative—compared to GEFS. In other words, the forecast information from MLGEFS is largely encompassed by GEFS. The good news is that MLGEFS does not introduce unreliable or misleading outputs into the final forecast products, as some have feared. However, the downside is that its overall contribution remains limited. This outcome may be attributed to the smaller ensemble spread in the current version of MLGEFS. To enhance the value of MLGEFS, more sophisticated ensemble perturbation methods are needed—ones that can increase the diversity of useful forecast information while minimizing the risk of introducing poor-quality predictions. A diffusion-model-based approach, such as GenCast, could be a promising candidate for future testing. Several other strategies may be worth exploring: (a) Noise-aware training or ensemble learning with stochastic perturbations to better capture chaotic dynamics; (b) Training with regime-aware or physics-informed loss functions; (c) Replacing autoregressive rollouts with diffusion models or transformers; (d) Developing improved ensemble perturbation strategies Additionally, because AI models are significantly more computationally efficient than physics-based models, dramatically increasing ensemble size is feasible in AI-based ensemble prediction systems—offering another pathway to enhance forecast diversity and value (Mahesh et al., 2024 and 2025 [32,33]).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic nonperiodic flow. J. Atmos. Sci., 1963, 20, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buizza, R.; Du, J.; Toth, Z.; Hou, D. Major operational ensemble prediction systems (EPS) and the future of EPS. In the book of Handbook of Hydrometeorological Ensemble Forecasting (edited by Q. Duan et al.), 2018, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp1-43. [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Berner, J.; Buizza, R.; Charron, M.; Houtekamer, P.; Hou, D.; Jankov, I.; Mu, M.; Wang, X.; Wei, W.; Yuan, H. Ensemble methods for meteorological predictions. In the book of Handbook of Hydrometeorological Ensemble Forecasting (edited by Q. Duan et al.), 2018, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp1-52. [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Mullen, S. L. , and Sanders, F. Short-range ensemble forecasting of quantitative precipitation. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1997, 125, 2427–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.J.; Kain, J.S.; Stensrud, D.J.; Xue, M.; Kong, F.; Coniglio, M.C.; Thomas, K.W.; Wang, Y.; Brewster, K.; Gao, J.; Weiss, S.J.; Bright, D.; Du, J. Probabilistic precipitation forecast skill as a function of ensemble size and spatial scale in a convection-allowing ensemble, Mon. Wea. Rev. 2011, 139, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, J. , and Coauthors. FourCastNet: A global data-driven high-resolution weather model using adaptive fourier neural operators. 2022, 2202.11214.

- Lam, R.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Willson, M.; Wirnsberger, P.; Fortunato, M.; Pritzel, A.; et al. Graphcast: Learning skillful medium-range global weather forecasting. Science 2023, 382, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, K.; Xie, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Gu, X.; Tian, Q. Accurate medium range global weather forecasting with 3-D neural networks. Nature 2023, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S., and Coauthors. AIFS—ECMWF’s data-driven forecasting system. 2024, URL https: //arxiv.org/abs/2406.01465, 2406.01465.

- Chen, L.; Zhong, X.; Li, H.; et al. A machine learning model that outperforms conventional global subseasonal forecast models. Nature Communications 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert-Uphoff, I.; Hilburn, K. The outlook for AI weather prediction. Nature 2023, 619, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, I. and co-authors. GenCast: Diffusion-based ensemble forecasting for medium-range weather. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.15796v2,. [CrossRef]

- Alet, F., Price, I., and El-Kadi A., & others. Skillful joint probabilistic weather forecasting from marginals. 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.10772.

- Radford, J. T., Ebert-Uphoff, I., DeMaria, R., Tourville, N., and Hilburn, K. Accelerating Community-Wide Evaluation of AI Models for Global Weather Prediction by Facilitating Access to Model Output. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2024.

- Bouallegue, Z. B. , and Coauthors. The rise of data-driven weather forecasting: A first statistical assessment of machine learning–based weather forecasts in an operational-like context. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2024, 105, E864–E883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton-Perez, A. J. , and Coauthors. Do AI models produce better weather forecasts than physics-based models? A quantitative evaluation case study of storm ciaran. NPJ Climate and Atmospheric Science 2024, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaria, R. Evaluation of tropical cyclone track and intensity forecasts from purely ML-based weather prediction models, illustrated with FourCastNet. 2024, https: //ams.confex.com/ams/104ANNUAL/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/436711.

- Wang, J.; Tabas, S. S., Cui, L., Du, J., Fu, B., Yang, F., Levit, J., Stajner, I., Carley, J., Tallapragada, V., and Gross, B. Machine learning weather prediction model development for global ensemble forecasts at EMC. EGU24 AS5.5 -- Machine Learning and Other Novel Techniques in Atmospheric and Environmental Science: Application and Development. Vienna, Austria, April 18, 2024.

- Wang, J.; Tabas, S. S., Fu, B., Cui, L., Zhang, Z., Zhu, L., Peng, J., and Carley, J. 2025. Development of a hybrid ML and physical model global ensemble system. 2025, NCEP Office Note, No. 522, 23pp. [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, P.W. and co-authors. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. 2018, arXiv:1806.01261v3. [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H. , Bell B., Berrisford, P, and coauthors. The ERA4 global reanalysis. QJRMS 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. J. , Putman, W., and Harris, L. FV3: the GFDL finite-volume cubed-sphere dynamical core (Version 1), NWS/NCEP/EMC, 2017, https://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/FV3-Technical-Description.pdf.

- Zhou, X. , and Coauthors. The Development of the NCEP Global Ensemble Forecast System Version 12. Wea. and Forecasting 2022, 37, 1069–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Zhu, Y.; Guan, H.; Sinsky, E.; Yang, B.; Xue, X.; Pegion, P.; Yang, F. Weather to seasonal prediction from the UFS coupled Global Ensemble Forecast System. Weather and Forecasting 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleist, D. T. , and Ide, K. An OSSE-based evaluation of hybrid variational-ensemble data assimilation for the NCEP GFS, Part I: System description and 3D-hybrid results. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2015, 143, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, G. J. , and Masanam, S. Dynamical Tests of a Deep Learning Weather Prediction Model. Artificial Intelligence for the Earth Systems 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavita, M. . On some limitations of current machine learning weather prediction models. Geophysical Research Letters 2024, 51, e2023GL107377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhou, B. A dynamical performance-ranking method for predicting individual ensemble member’s performance and its application to ensemble averaging. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2011, 129, 3284–3303. [Google Scholar]

- Selz, T.; Craig, G.C. Can artificial intelligence-based weather prediction models simulate the butterfly effect? Geophysical Research Letters 2023, 50, e2023GL105747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J. Performance Rank Variation Score (PRVS) to measure the variation in ensemble member’s relative performance with an introduction to “Transformed Ensemble” post-processing method. Meteorology 2025, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonich, P. T. , and Hakim, G. J. Testing the Limit of Atmospheric Predictability with a Machine Learning Weather Model. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, A., Collins, W., Bonev, B., & co-authors. Huge Ensembles Part I: Design of Ensemble Weather Forecasts using Spherical Fourier Neural Operators. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, A. , Collins, W., Boney, B., & co-authors. Huge Ensembles Part II: Properties of a Huge Ensemble of Hindcasts Generated with Spherical Fourier Neural Operators. 2025, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2408.01581.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).