1. Introduction

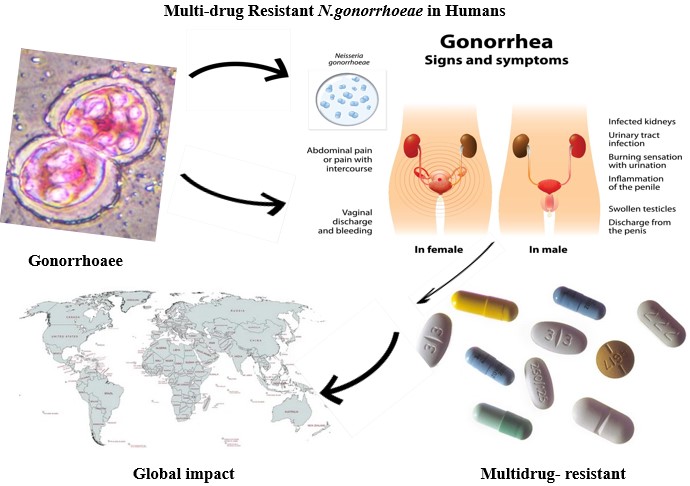

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a Gram-negative diplococcus and the etiological agent of gonorrhea, remains a major global public health challenge. As an obligate human pathogen, it is predominantly transmitted through sexual contact, infecting the urogenital tract in men and the endocervix in women, while also colonizing extragenital sites such as the rectum, pharynx, and conjunctiva [Mayor et al., 2012]. Untreated infections can result in severe reproductive health complications, including pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and heightened susceptibility to HIV acquisition and transmission [Fleming and Wasserheit, 1999; Bala and Sood, 2010]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that approximately 82.4 million new gonorrhea cases occur globally each year, underscoring the persistent burden of this sexually transmitted infection (STI) [Mahapure and Singh, 2023; WHO, 2020]. Over the past decades, N. gonorrhoeae has progressively developed resistance to nearly all major antibiotic classes, including sulfonamides, penicillins, tetracyclines, quinolones, and macrolides [Biała et al., 2024; Unemo et al., 2019; Unemo et al., 2021]. Dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin was historically recommended in many countries, including India, to preserve ceftriaxone efficacy and delay the emergence of resistance [WHO, 2024; CDC, 2020; Unemo et al., 2018]. However, recent surveillance indicates a paradox: while ceftriaxone resistance remains relatively uncommon, azithromycin resistance has escalated, accompanied by documented treatment failures with dual therapy [Radovanovic, 2022; Merrick, 2022; NSW Health, 2024]. Consequently, clinical guidelines in the United Kingdom and United States have shifted towards recommending ceftriaxone monotherapy, both to safeguard efficacy and to limit the ecological impact of azithromycin use on commensals and other pathogens [Fifer et al., 2020; Cyr et al., 2020].

Despite these adjustments, reports of reduced susceptibility and confirmed resistance to ceftriaxone the cornerstone of current therapy are increasingly concerning, including cases documented in Australia [NSW Health, 2024]. Alarming data from the WHO Enhanced Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (EGASP) in Cambodia revealed resistance to ceftriaxone in 15.4% of isolates, azithromycin non-susceptibility in 14.4%, and 6.2% of strains classified as extensively drug-resistant (XDR) [Ouk et al., 2024]. Such findings highlight the extraordinary adaptability of N. gonorrhoeae, driven by high genetic plasticity, horizontal gene transfer, and mutations affecting antimicrobial targets and efflux systems [Manoharan-Basil et al., 2021]. Moreover, asymptomatic colonization at extragenital sites facilitates silent transmission and complicates early diagnosis and control [Walker et al., 2023]. Current WHO reports further emphasize the global scale of the problem, noting widespread ciprofloxacin resistance, rising azithromycin resistance, and emerging reduced susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone [WHO, 2025]. The emergence of extensively drug-resistant strains with high-level ceftriaxone resistance often termed “super gonorrhea” represents an unprecedented clinical challenge.

In recognition of these escalating threats, the WHO has classified N. gonorrhoeae as a high-priority pathogen, underscoring the urgent need for strengthened surveillance, novel therapeutic options, and vaccine development [WHO, 2017]. However, the field remains divided on optimal strategies, with some advocating intensified stewardship of existing antibiotics, while others emphasize the exploration of non-traditional interventions, such as plant-derived bioactive compounds and host-directed therapies. The present review seeks to provide a comprehensive synthesis of current knowledge on antimicrobial resistance in N. gonorrhoeae, with a particular focus on its molecular drivers, epidemiological trends, clinical implications, and emerging countermeasures. By integrating conventional resistance mechanisms with advances in diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine development, we aim to present a holistic framework to inform research, clinical management, and public health policies.

2. Methodology

A structured literature search was performed across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and Google Scholar to identify publications relevant to antimicrobial resistance, epidemiology, diagnostics, therapeutic strategies, and vaccine development in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Peer-reviewed articles, surveillance reports, and review papers published in English were considered, with primary emphasis on studies from the past two decades, while seminal earlier works were also included to provide essential historical context. The search covered literature published from the earliest available records through June 2025, using combinations of keywords such as “Neisseria gonorrhoeae,” “antimicrobial resistance,” “epidemiology,” “molecular diagnostics,” “treatment,” “novel therapeutics,” and “vaccine development.” Reference lists of selected publications were manually screened to ensure comprehensive coverage. This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to enhance transparency and methodological rigor.

3. Taxonomy and Diversity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Neisseria gonorrhoeae belongs to the genus Neisseria, comprising Gram-negative, aerobic, oxidase-positive diplococci. Taxonomically, the genus is classified within the family Neisseriaceae, order Neisseriales, class Betaproteobacteria, and phylum Pseudomonadota (formerly Proteobacteria). Of the many Neisseria species, only N. gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis are obligate human pathogens. N. gonorrhoeae is the etiological agent of gonorrhea, a prevalent sexually transmitted infection (STI), whereas N. meningitidis causes invasive diseases such as bacterial meningitis and septicemia.

3.1. Taxonomic Classification

Domain: Bacteria

Kingdom: Monera (not officially used in modern taxonomy; now replaced by Domain Bacteria)

Phylum: Pseudomonadota (formerly Proteobacteria)

Class: Betaproteobacteria

Order: Neisseriales

Family: Neisseriaceae

Genus: Neisseria

Species: Neisseria gonorrhoeae [Oren et al., 2021]

3.2. Morphology and Arrangement

The cells of

Neisseria gonorrhoeae are Gram-negative nonmotile diplococci, approximately 0.8 μm in diameter and typically occurring in pairs (diplococci) with adjacent sides flattened, giving them a characteristic kidney bean or coffee bean shape as shown in (

Figure 1). This morphology is often observed in Gram-stained clinical specimens and cultures, particularly within or adjacent to polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs).

3.3. Phenotypic and Genotypic Diversity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Neisseria gonorrhoeae demonstrates extensive phenotypic and genotypic diversity that drives its adaptability and persistence. Phenotypically, variability in colony morphology, outer membrane protein expression, antimicrobial susceptibility, and virulence traits influences clinical outcomes and treatment responses. Genotypically, high plasticity through horizontal gene transfer, phase/antigenic variation, and frequent recombination fosters novel resistant lineages. Whole-genome sequencing has revealed substantial heterogeneity across global isolates, shaped by regional evolutionary pressures and antimicrobial use. This diversity complicates treatment, vaccine development, and surveillance. Recent evidence illustrates this complexity: in Cameroon, cgMLST identified four core genome lineages, including one harboring gyrA/parC alleles for ciprofloxacin resistance but preserved ceftriaxone susceptibility [Tayimetha et al., 2023]. In New Zealand, half of isolates (2020–2021) showed reduced ceftriaxone susceptibility, universal ciprofloxacin resistance, and multiple penA alleles with additional resistance mutations [Jamaludin et al., 2019]. Indian isolates exhibited >90% quinolone resistance, ~6.7% decreased ceftriaxone susceptibility, and numerous novel NG-MAST types, highlighting the value of genotypic over phenotypic typing [Sood et al., 2019]. Swiss isolates from MSM remained ceftriaxone-susceptible but were highly resistant to azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline, with WGS correlating resistance determinants [Jünger et al., 2024]. Collectively, these findings underscore the clinical and public health challenges posed by gonococcal diversity

3.4. Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a Gram-negative, aerobic, oxidase-positive diplococcus responsible for the sexually transmitted infection (STI) gonorrhea. Gonorrhoea is an ancient disease, with references traceable to the Bible (Leviticus 15:1–3). First described by Albert Neisser in 1879, this pathogen remains a significant global public health challenge due to its increasing resistance to multiple antibiotics and its capacity to cause serious reproductive and systemic complications if left untreated. According to WHO estimates, there are approximately 87 million new gonococcal infections worldwide each year [Rowley, et al., 2019]. Of these, around 4 million cases occur in high-income regions, including Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand. The vast majority over 80 million infections occur in low- and middle-income countries across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean [Rowley, et al., 2019]. However, an increasing incidence of gonorrhea has been reported in recent years in Europe and the United States [ECDPC, 2019; ECDC, 2020]. Neisseria gonorrhoeae appears microscopically as kidney-shaped diplococci, often found in pairs with flattened adjacent sides. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a non-motile, fastidious organism that requires complex, nutritionally enriched media such as chocolate agar and a CO₂-enriched atmosphere for optimal in vitro growth. Colonies typically appear small, round, and translucent after 24-48 hours of incubation. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a human-specific pathogen that colonizes mucosal surfaces and serves as the etiological agent of lower urogenital tract infections, causing urethritis in men and cervicitis in women. The organism is oxidase-positive and ferments glucose but not maltose, which helps differentiate it from its close relative Neisseria meningitides.

4. Virulence Factors of Neisseria gonorrhoeae

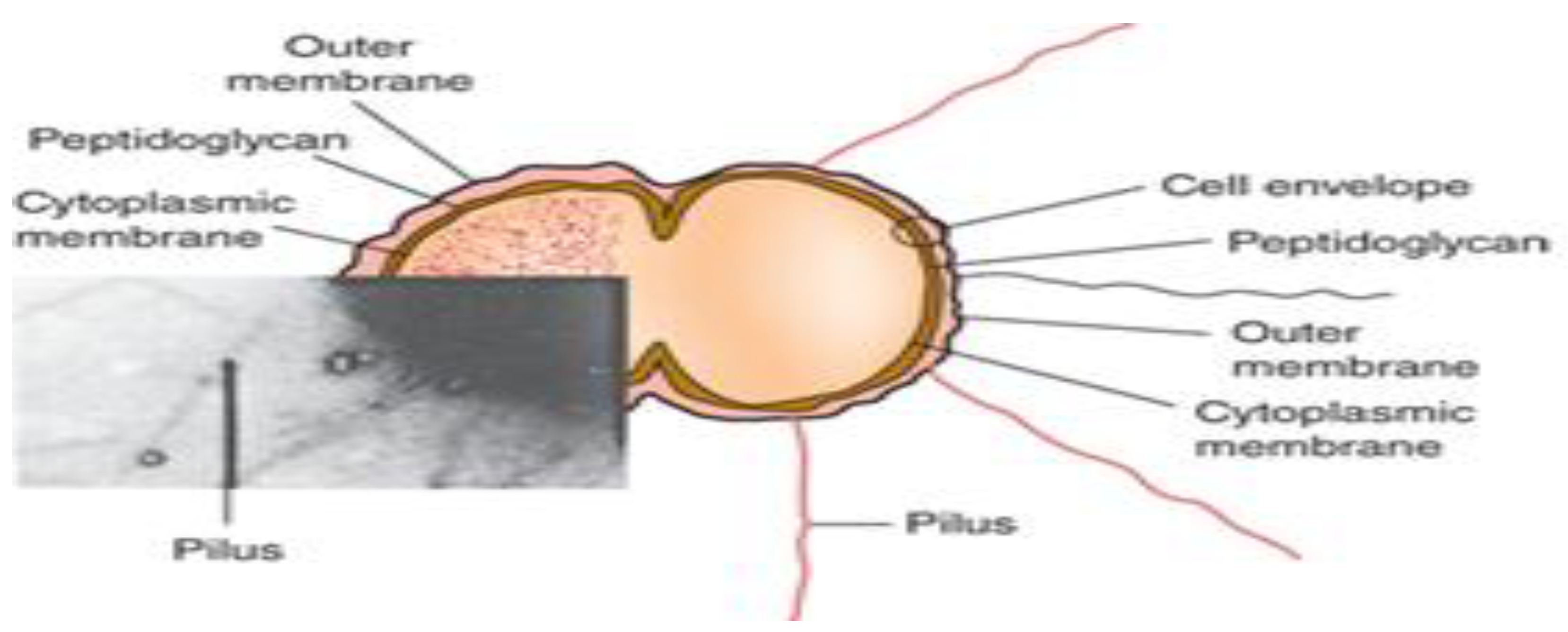

Neisseria gonorrhoeae utilizes a broad range of virulence factors to support colonization, immune evasion, and persistence within the host. Key surface components include Type IV pili, PorB, Opa, Rmp, Tbp, Lbp, and lipooligosaccharide (LOS), while IgA1-specific serine protease functions as a major extracellular virulence factor as illustrated in (

Figure 2). The bacterial cell envelope comprises a cytoplasmic membrane, periplasmic peptidoglycan layer, and an outer membrane enriched with these virulence determinants [Quillin and Seifert, 2018]. Collectively, these factors enable

N. gonorrhoeae to adhere to epithelial surfaces, evade host defenses, and establish infection.

4.1. Pili and Type IV Fimbriae

Type IV pili (T4P), also referred to as fimbriae in Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and are filamentous, surface-exposed structures primarily composed of the pilin subunit PilE [Freitag et al., 1995]. These pili play a critical role in the initial attachment of the bacterium to host epithelial cells, marking the first step in the infection process. In addition to mediating adhesion, Type IV pili facilitate twitching motility, contribute to biofilm formation, and are essential for natural transformation through DNA uptake [Taktikos et al., 2015]. The adhesion process is further strengthened by outer membrane proteins such as Opa, which enhance bacterial invasion into host tissues. Collectively, these virulence factors are crucial for the successful colonization and pathogenesis of N. gonorrhoeae.

4.2. Opa Proteins

Opa proteins are integral outer membrane proteins of Neisseria gonorrhoeae that contribute to colony opacity due to inter-bacterial aggregation, as observed under phase-contrast microscopy [Fox et al., 2014]. These proteins play a pivotal role in mediating intimate adherence to and invasion of host epithelial cells, representing a critical step following initial attachment. Each N. gonorrhoeae strain possesses multiple (typically ≥10) opa genes, and the bacterium can express none, one, or several Opa variants simultaneously, allowing for phase-variable expression and immune evasion [Swanson et al., 1992]. Following the initial attachment mediated by Type IV pili, Opa proteins facilitate tight binding and internalization into host cells, thereby advancing the infection process [Shaughnessy et al., 2019].

4.3. Outer Membrane Porins (Por Proteins)

Porins are integral outer membrane proteins that facilitate the passive transport of nutrients, ions, and small molecules across the bacterial outer membrane, contributing significantly to the survival and persistence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae within host environments [Shaughnessy et al., 2019]. Among these, the gonococcal outer membrane porin protein, Por, is the most abundant, accounting for approximately 60% of the total outer membrane protein content [Hung and Christodoulides, 2013]. While Por exhibits inter-strain size variability, each gonococcal strain typically expresses a single Por variant, which forms the basis for serological classification of strains. Two distinct classes of Por exist: PorA and PorB. PorA is associated with more invasive or complicated gonococcal infections, whereas PorB is predominantly linked to uncomplicated mucosal infections [Hill et al., 2016; Shaughnessy et al., 2019]. PorB, in particular, plays a multifunctional role, enhancing nutrient uptake, interfering with neutrophil-mediated killing, and contributing to immune evasion. Upon host cell attachment, gonococcal PorB has been shown to translocate from the bacterial outer membrane into host epithelial cell membranes and further integrate into mitochondrial membranes [Weel et al., 1991; Müller et al., 2002]. This integration results in the formation of porin channels in the mitochondrial inner membrane, leading to increased membrane permeability and the induction of host cell apoptosis [Müller et al., 1999].

4.4. LOS (lipooligosaccharide)

Lipooligosaccharide (LOS) is a major glycolipid component of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae outer membrane, structurally similar to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) but lacking the extended O-antigen polysaccharide chain [Shaughnessy et al., 2019]. Gonococcal LOS plays a crucial role in virulence and pathogenesis, contributing to mucosal tissue damage, promoting bacterial translocation across epithelial barriers, and conferring resistance to complement-mediated killing by normal human serum [Shaughnessy et al., 2019]. Functioning as a potent endotoxin, LOS elicits a robust innate immune response, including the activation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which leads to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and recruitment of immune cells. Multiple antigenic variants of LOS are expressed among gonococcal strains, facilitating immune evasion through phase variation and enhancing bacterial persistence within the host [Hung and Christodoulides, 2013].

4.5. Reduction Modifiable Protein (Rmp)

The Reduction Modifiable Protein (Rmp) is an outer membrane protein of Neisseria gonorrhoeae that associates with porin proteins (Por) to facilitate the formation of pores in the bacterial surface [Rice et al., 1994]. Rmp plays a key role in immune evasion by protecting Por and lipooligosaccharide (LOS) from the action of bactericidal antibodies [Shaughnessy et al., 2019]. Notably, the presence of anti-Rmp antibodies in women has been associated with an increased susceptibility to gonococcal infection, possibly due to the blocking of protective immune responses [Plummer et al., 1993].

4.6. Transferrin Binding Proteins (Tbp1 and Tbp2)

Neisseria gonorrhoeae relies on specialized iron acquisition systems to survive and proliferate within the iron-limited environment of the host. Under iron-deprived conditions, it expresses outer membrane proteins Tbp1 and Tbp2, which bind human transferrin to extract iron essential for bacterial growth and invasion [Shaughnessy et al., 2019]. These proteins, along with lactoferrin-binding protein (Lbp), also facilitate iron acquisition from other host sources such as haemoglobin and ferritin [Noinaj et al., 2012]. The expression of transferrin-binding proteins is critical for gonococcal infectivity and pathogenesis [Cornelissen et al., 1998].

4.7. IgA Protease

Neisseria gonorrhoeae produces IgA1-specific serine protease, a virulence factor uniquely expressed by pathogenic Neisseria species [Hill et al., 2016]. Upon secretion, the protease undergoes endo-proteolytic processing to achieve its mature, active form. During infection, the mature IgA protease specifically cleaves human IgA1 at the proline-rich hinge region of its heavy chain, thereby impairing mucosal immune defense [Edwards and Butler, 2011]. Additionally, the protease targets and cleaves lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), leading to lysosomal dysfunction and enhanced intracellular survival of the bacteria [Ayala et al., 2002].

4.8. Phase and Antigenic Variation

Neisseria gonorrhoeae employs phase variation a reversible on/off switching of gene expression primarily through slipped-strand mispairing during DNA replication. This mechanism involves frame shifts within genes containing short repetitive sequences, leading to stochastic expression of key surface antigens such as pili, Opa proteins, and lipooligosaccharide (LOS) [Hill and Davies, 2009; Hung and Christodoulides, 2013]. For instance, frame shifting in the pilE or pilC genes controls pilus expression (Pil⁺/Pil⁻), while variation in glycosyltransferase genes alters LOS structure and contributes to serum resistance [Yang and Gotschlich, 1996]. Similarly, multiple opa gene copies contain “CTCTT” repeats, where addition or deletion of repeat units brings each opa gene in or out of frame (Opa⁺/Opa⁻), allowing antigenic variation and immune evasion [Hung and Christodoulides, 2013]. Allows for rapid alteration of surface structures to evade immune detection. Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains resistant to ceftriaxone and azithromycin -the current first-line dual therapy have been increasingly reported, posing a threat to global gonorrhea control efforts. Antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae involves changes in the amino acid composition of surface-exposed proteins, enabling the emergence of new variants during infection and preventing the development of effective protective immunity [Simms and Jerse, 2005]. This variation occurs at high frequency, independent of specific antibody pressure, and primarily affects Type IV pili (PilE) and Opa proteins [Hung and Christodoulides, 2013]. Through gene conversion and recombination, gonococci alter both the quantity and sequence composition of pilin subunits, enhancing their ability to evade host immune responses [Hill and Davies, 2009].

5. Clinical Manifestations of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Infection

Neisseria gonorrhoeae primarily infects superficial mucosal surfaces lined with columnar epithelium, most commonly affecting the urogenital tract, rectum, pharynx, and conjunctiva [Brunham et al., 2015; Allan-Blitz et al., 2017]. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the anatomical site, host immune response, and gender, and include pharyngeal, rectal, urogenital infections, and conjunctivitis, particularly in neonates are summarized in (

Table 1). Gonorrheal infections may be symptomatic or asymptomatic, especially in women, which complicates diagnosis and control. If left untreated, infections can lead to serious complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and increased risk of HIV transmission [Pathela et al., 2013; Sadiq et al., 2005].

5.1. Urogenital Infections

In males, Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection primarily targets the mucosal epithelium of the anterior urethra, resulting in acute urethritis, characterized by dysuria, purulent or mucopurulent urethral discharge, itching, and occasionally testicular or rectal pain [Edwards and Apicella, 2004]. Symptoms typically appear within 2–7 days post-exposure, with an incubation range of 1 to 14 days [Harrison et al., 1979]. Inflammation leads to classical signs of redness, swelling, and a burning sensation during urination. While most men are symptomatic, a subset remains asymptomatic carriers, serving as reservoirs for transmission and at risk for complications [Handsfield et al., 1974]. Ascending infections may lead to epididymitis, prostatitis, or orchitis. In females, gonorrhea is often asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, contributing to delayed diagnosis. When present, symptoms include cervicitis, abnormal vaginal discharge, intermenstrual bleeding, and postictal bleeding. If untreated, the infection may ascend to the upper genital tract, resulting in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), a serious condition that can lead to chronic pelvic pain, tubal infertility, and ectopic pregnancy.

5.2. Rectal and Pharyngeal Infections

Neisseria gonorrhoeae can infect extragenital sites such as the pharynx and rectum, often following oral or anal sexual contact. Pharyngeal infections, acquired primarily through orogenital intercourse, are typically asymptomatic, with rare cases of exudative pharyngitis. When symptomatic, they may present with pharyngitis, tonsillitis, cervical adenitis, or low-grade fever. Rectal infections are also frequently asymptomatic, particularly in women and men who have sex with men (MSM). In symptomatic cases, proctitis may manifest as anal discomfort, pruritus, painful defecation, mucopurulent discharge, tenesmus, or scant rectal bleeding [Klausner et al., 2004]. In women, rectal involvement may occur via autoinoculation from cervical discharge or through receptive anal intercourse. These extra genital sites serve as important reservoirs for ongoing transmission and are often missed during routine urogenital screening, thus posing a challenge for gonorrhea control and contributing to the emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

5.3. Conjunctival Infections

Neisseria gonorrhoeae can cause gonococcal conjunctivitis (GC), a purulent eye infection affecting both neonates and, less commonly, adults. In newborns, the condition termed ophthalmia neonatorum is acquired during vaginal delivery from an infected mother. It typically presents within the first few days of life with conjunctival chemosis, profuse purulent discharge, eyelid edema, and preauricular lymphadenopathy. Although the global incidence is <1%, untreated GC can lead to severe complications, including corneal ulceration, perforation, systemic dissemination, and blindness [Klausner et al., 2004; Costumbrado et al, 2022]. In adults, gonococcal conjunctivitis is rare but may occur via autoinoculation from genital secretions, presenting as hyperacute conjunctivitis with rapid progression. Prompt diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy are essential to prevent vision-threatening outcomes. Importantly, GC is largely preventable through prenatal screening, maternal treatment, and prophylactic ocular therapy at birth.

5.4. Disseminated Gonococcal Infection (DGI)

Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) is a systemic complication of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection, occurring in approximately 0.5–3% of cases, and is more frequently observed in women [Bleich et al., 2012]. It results from bacteremia, often in the absence of urogenital symptoms, and is more common in individuals with complement deficiencies, particularly terminal complement component deficiencies. DGI typically presents with a triad of migratory polyarthritis, tenosynovitis, and dermatitis, often accompanied by fever. In severe cases, it can progress to septic arthritis, hepatitis, myocarditis, endocarditis, or meningitis. Early recognition and appropriate antimicrobial therapy are essential to prevent long-term complications.

5.5. Co-Infections and Synergistic Risks

Neisseria gonorrhoeae often co-infects with other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including Chlamydia trachomatis, Treponema pallidum, Trichomonas vaginalis, and HIV. A recent global meta-analysis reported co-infection prevalences among people with HIV (PWH) as follows: T. pallidum (4.8%; 95% CI: 4.7–5.0%), N. gonorrhoeae (0.8%; 95% CI: 0.6–0.9%), C. trachomatis (2.5%; 95% CI: 2.2–2.7%), and T. vaginalis (3.0%; 95% CI: 2.7–3.3%). The burden of these STIs is notably higher in Africa, Southeast Asia, and among high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TGW). Co-infection with HIV is of particular concern, as gonorrhea-induced mucosal inflammation and epithelial disruption significantly enhance HIV transmission and acquisition [Zhang, et al, 2025]. Therefore, comprehensive syndromic management and concurrent STI screening are essential for all patients diagnosed with gonorrhea to improve treatment outcomes and reduce disease transmission.

5.6. Patient Risk Factors for Neisseria gonorrhoeae Infection

Globally, more than one million sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are acquired every day [WHO, 2016], with treatable bacterial pathogens such as Treponema pallidum, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Trichomonas vaginalis contributing significantly to this burden [WHO, 2019]. Gonorrhea is a significant cause of morbidity among sexually active population. The highest prevalence rates are observed in developing regions, particularly South and Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa [WHO, 2012]. Among these, N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis represent the most common bacterial STIs and frequently occur as co-infections. The acquisition and persistence of N. gonorrhoeae are shaped by multiple demographic, behavioral, biological, and socioeconomic factors, including age, gender, sexual practices, access to healthcare, and underlying immunological status. Understanding these risk determinants is essential for informing targeted prevention efforts, enhancing disease surveillance, and guiding clinical management, particularly in light of the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

5.7. Age and Gender

Adolescents and young adults aged 15-29 years represent the population most at risk for acquiring Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. This increased vulnerability is attributed to heightened sexual activity, inconsistent condom use, and biological susceptibility. Females, in particular, are more likely to harbor asymptomatic infections, which contributes to delayed diagnosis and sustained transmission within communities. Adolescent girls and young women are disproportionately affected by gonorrhea, influenced by factors such as early sexual debut, engagement in transactional sex, and limited access to reproductive and sexual health services, including contraception, routine STI screening, and confidential clinical care [Klaper, 2024; Omeershffudin and Kumar, 2023]. These gendered and age-related disparities highlight the need for targeted public health interventions and youth-friendly sexual health services to mitigate disease burden in this vulnerable population.

5.8. Sexual Behavior

In recent years, a resurgence of gonorrhea cases has been observed in various regions, particularly in urban settings and among specific high-risk populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM) and adolescents [Akpomedaye et al., 2024]. The risk of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection is markedly elevated in association with certain sexual behaviors, including: Having multiple or anonymous sexual partners, Inconsistent or no condom use, Engagement in anal or oral sex, leading to asymptomatic rectal and pharyngeal infections Transactional sex or involvement in sex work. These behaviors are especially prevalent among key populations, including MSM, who bear a disproportionately high burden of gonorrhea, including infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. These epidemiological dynamics underscore the importance of targeted prevention strategies, frequent screening, and enhanced antimicrobial resistance surveillance in vulnerable populations.

5.9. History of Previous STIs

Multiple socio-behavioral and structural factors contribute to the vulnerability of individuals to Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. These include socioeconomic disparities, restricted access to healthcare, cultural and language barriers, and experiences of stigma or discrimination in healthcare settings [Tuddenham et al., 2021]. Such barriers can delay diagnosis and treatment, perpetuating the transmission cycle. A history of prior sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including Chlamydia trachomatis, Treponema pallidum, or previous gonorrhea is a well-documented risk factor, often reflecting ongoing high-risk sexual behaviors or reinfection from untreated partners. Effective prevention requires that healthcare providers not only conduct comprehensive risk assessments but also implement partner notification and treatment services to reduce reinfection rates and interrupt transmission within sexual networks. Additionally, targeted counseling and support services should be offered to high-risk individuals, particularly those with multiple sexual partners, inconsistent condom use, or a history of STIs [Yellman, 2020].

5.9.1. Coinfection with HIV

Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection significantly increases the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission, particularly in high-risk populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM) [Imarenezor et al., 2024; Ofiri et al., 2024]. Although gonorrhea is a non-ulcerative STI, it induces genital tract inflammation and mucosal disruption, which facilitates HIV entry during exposure and enhances HIV shedding in co-infected individuals. Epidemiological and clinical studies have consistently shown that gonorrhea acts as both a marker of high-risk sexual behavior and a facilitator of HIV spread. The inflammatory response associated with N. gonorrhoeae compromises mucosal barriers and recruits HIV target cells (e.g., CD4+ T cells and macrophages), thereby increasing HIV susceptibility and infectiousness in co-infected hosts [Xu SX et al., 2018]. Given this interaction, integrated STI/HIV screening and treatment strategies are critical, especially in key populations, to curb transmission dynamics and improve public health outcomes.

5.9.2. Low Socioeconomic Status and Limited Access to Healthcare

Socioeconomic disparities, limited access to healthcare, and low health literacy are critical determinants influencing the transmission and persistence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. Individuals in low-resource settings often face significant barriers to screening, timely diagnosis, and effective treatment, resulting in a higher burden of undiagnosed and untreated infections. Educational attainment and socioeconomic support have been shown to indirectly improve sexual health literacy, promote safer sexual behaviors, and reduce stigma associated with STIs. Interventions that target these upstream determinants such as improving education, reducing poverty, and strengthening healthcare infrastructure may significantly contribute to long-term reductions in gonorrhea incidence, especially in vulnerable populations.

5.9.3. Partner’s Risk Profile

The heightened risk of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection may be attributed to repeated high-risk sexual behaviors, including multiple sexual partnerships, inconsistent condom use, and inadequate follow-up after initial treatment. Biological predispositions or persistent, subclinical infections may further contribute to sustained vulnerability. Individuals of both sexes engaging in frequent partner change and inconsistent protective measures are at significantly increased risk of transmission [Lipsky, 2021]. Additionally, the infection status and sexual behavior of one’s partner(s) particularly those with multiple concurrent relationships or a prior history of STIs substantially influences individual risk.

5.9.4. Lack of Regular Screening

There is a critical need for tailored public health interventions targeting male populations, emphasizing the promotion of STI awareness, routine screening, and consistent condom use. Addressing behavioral risk factors such as low health-seeking behavior and inconsistent use of protection can significantly reduce gonococcal transmission within communities. Many infections, particularly pharyngeal, rectal, and cervical gonorrhea, remain asymptomatic and are often detected only through systematic screening. The lack of routine STI screening, especially in high-risk populations, contributes to the silent spread of the disease and facilitates the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant strains.

6. Molecular Characterization of Gonococcal Resistance

Molecular characterization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae is central to understanding its epidemiology and tracking the spread of antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) strains. Approaches broadly fall into two categories: (i) gene-based typing methods, which elucidate genetic relationships among isolates to monitor transmission and population structure, and (ii) detection of resistance-associated determinants, which identify specific mutations or acquired genes linked to reduced antimicrobial susceptibility.

6.1. Gene-Based Typing Methods

NG-MAST (N. gonorrhoeae Multi-Antige Sequence Typing): Targets hypervariable regions of two genes-porB (490 bp) and tbpB (390 bp). It has been widely used for epidemiological tracking, but its resolution for AMR prediction is limited, as variation can exist within sequence types [Martin et al., 2004]. MLST (Multi-Locus Sequence Typing): Analyzes partial sequences of seven conserved housekeeping genes (abcZ, adk, aroE, fumC, gdh, pdhC, and pgm) to define stable sequence types. MLST is highly reproducible and informative for global lineage and population structure studies [Enright and Spratt, 1999; Maiden et al., 1998].

NG-STAR (N. gonorrhoeae Sequence Typing for Antimicrobial Resistance) Designed specifically for AMR surveillance, NG-STAR uses allelic profiles of seven resistance-associated genes (penA, mtrR, porB, ponA, gyrA, parC, and 23S rRNA) to track and compare resistance trends worldwide [Demczuk et al., 2017]. Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS): Next-generation sequencing enables comprehensive detection of AMR genes, outbreak investigation, and comparative genomics. WGS offers the highest resolution for phylogenetic analysis and resistance prediction, while also elucidating evolutionary dynamics and global dissemination [Balloux et al., 2018; Mortimer and Grad, 2019].

6.2. Detection of Resistance Determinants

Direct Detection of AMR Markers: PCR-based assays and multiplex PCR can rapidly identify specific mutations or resistance-conferring sequences. However, these methods are generally limited to known mutations and risk cross-reactivity with commensal Neisseria species, particularly in pharyngeal samples [Roymans et al., 2000; Goire et al., 2014].

6.3. Rapid Molecular Diagnostics

Emerging diagnostics aim to overcome delays of culture-based susceptibility testing. Methods include: Conventional PCR; Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR); Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP); CRISPR-based assays; Sequencing-based platforms.

Table 2.

Molecular diagnostic approaches for Neisseria gonorrhoeae detection.

Table 2.

Molecular diagnostic approaches for Neisseria gonorrhoeae detection.

| Method |

Principle |

Key Advantages |

Limitations |

Applications/ References |

| Conventional PCR |

DNA amplification using sequence-specific primers under thermal cycling [Mullis and Faloona, 1987] |

High sensitivity and specificity; rapid compared to culture; can detect AMR genes |

Requires thermal cycler; contamination risk; post-PCR processing needed |

Early detection of N. gonorrhoeae; AMR gene surveillance [Vasala et al., 2020] |

| Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR) |

Monitors amplification in real time using fluorescent dyes (SYBR Green) or probes (TaqMan) [Tajadini et al., 2014] |

Quantitative; rapid turnaround; high sensitivity/specificity; multiplexing possible |

Higher cost; requires advanced equipment |

Detection in urogenital, rectal, pharyngeal samples; clinical diagnosis and epidemiological studies [Man et al., 2021] |

| Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) |

Isothermal DNA amplification using strand-displacing polymerase and 4–6 primers targeting multiple regions [Park et al., 2022] |

Cost-effective; rapid (<1h); high specificity; minimal equipment; suitable for POC |

Primer design complex; less widely standardized |

Field-based/POC testing; resource-limited settings [Ahmadi et al., 2025] |

| CRISPR-based assays |

Leverages Cas proteins (e.g., Cas12, Cas13) guided by gRNA to detect target DNA/RNA, often coupled with fluorescence or lateral-flow readouts [Kellner et al., 2019] |

Ultra-sensitive; rapid (<1 h); portable; amenable to multiplexing and POC applications |

Still under development for clinical adoption; may require pre-amplification |

Rapid detection of N. gonorrhoeae and AMR markers directly from

clinical specimens [Li et al., 2021; de Puig et al., 2021] |

| Sequencing-based platforms (NGS/WGS) |

High-throughput sequencing of whole genomes or targeted regions to identify species and resistance markers [Goodwin et al., 2016] |

Comprehensive; enables strain typing, AMR marker discovery, and epidemiological surveillance |

Higher cost; requires bioinformatics expertise and infrastructure |

Resistance mechanism discovery; outbreak investigation; global surveillance of AMR trends [Mortimer and Grad, 2019; Eyre et al., 2021] |

7. Emerging Diagnostic Technologies for Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Isothermal amplification techniques (NASBA, TMA, and HDA): Isothermal nucleic acid amplification methods provide rapid, sensitive alternatives to PCR for N. gonorrhoeae detection. NASBA and TMA target mRNA, enabling identification of viable pathogens and reducing false positives from residual DNA, and are incorporated into several commercial STI assays [Gaydos and Hardick, 2014]. HDA, which uses helicase to unwind DNA at a constant temperature, has demonstrated reliable detection of N. gonorrhoeae and other bacterial pathogens, with advantages for point-of-care (POC) testing in low-resource settings [Vincent et al., 2004; Tong et al., 2011; Mitani et al., 2013]. Microfluidics: Advances in microfluidic platforms have enabled integrated, sample-to-answer molecular diagnostics. A recent system achieved multiplex detection of major STIs, including N. gonorrhoeae, in <40 minutes with high concordance to conventional PCR [Liu et al., 2025]. These miniaturized devices reduce cost, turnaround time, and infrastructure needs, making them highly suitable for decentralized and POC applications.

8. Evolutionary Dynamics of Antimicrobial Resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae

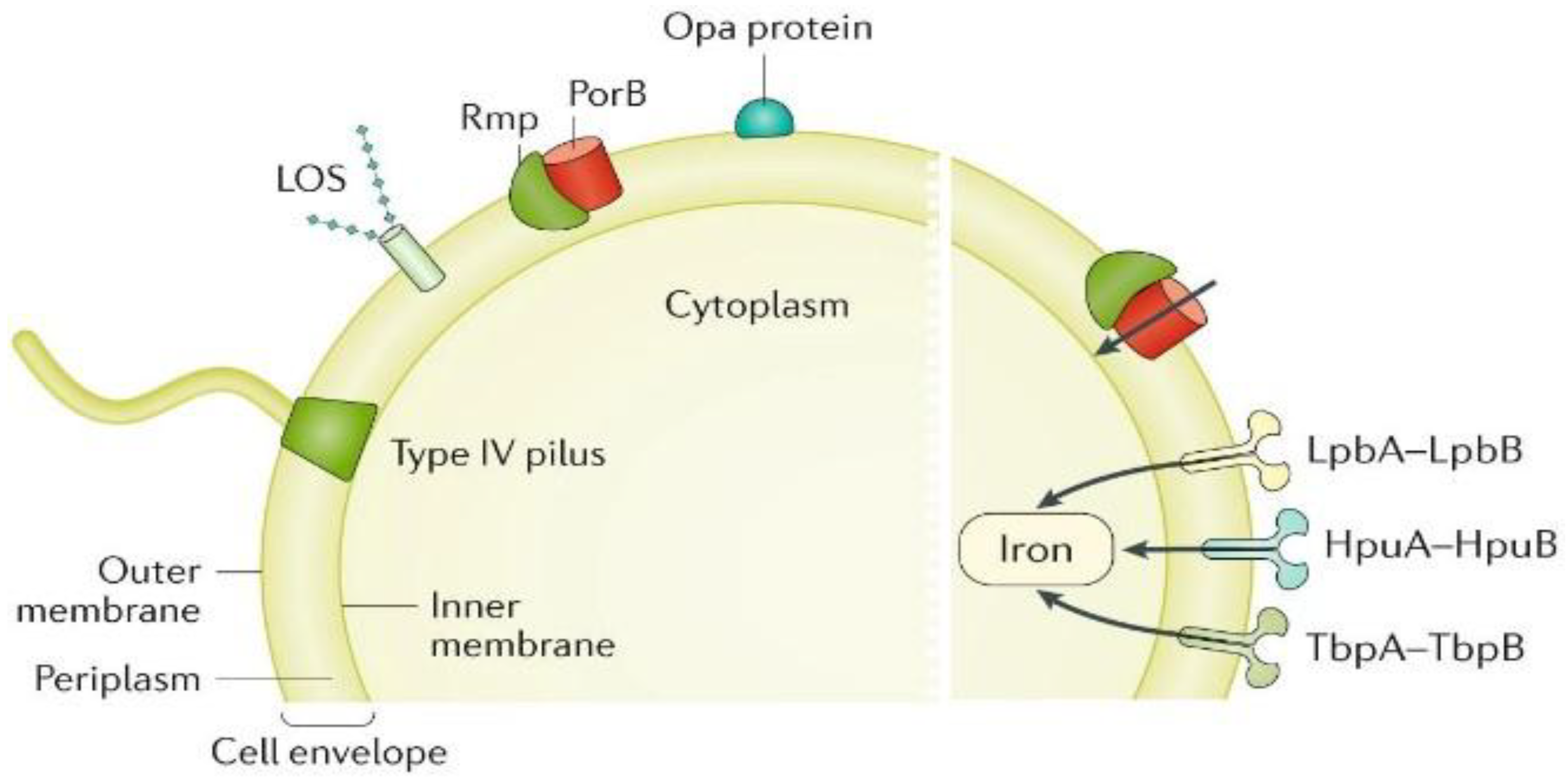

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in

Neisseria gonorrhoeae reflects the pathogen’s extraordinary genomic adaptability, shaped by natural competence, horizontal gene transfer, and frequent recombination events [Unemo and Shafer, 2014]. Point mutations, insertions, and mosaic alleles further enhance resistance, while transformation from commensal

Neisseria spp. contributes novel resistance determinants [Corander et al., 2012; Ezewudo et al., 2015]. These mechanisms collectively underpin the rapid evolution of resistance to nearly all antibiotic classes used for the treatment of gonorrhea, and the major resistance determinants are summarized in

Table 3 and illustrated in

Figure 3.

8.1. Sulfonamides Resistance

Sulfonamides were the first widely available antimicrobial agents used for the treatment of gonorrhoea. Sulfanilamide, discovered by Gerhard Domagk in 1935, achieved cure rates of 80-90% in patients [Oriel JD. 1994; Lewis, 2010]. Subsequently, sulfapyridine (introduced in 1940–1941) and sulfathiazole demonstrated improved efficacy and tolerability, particularly in cases where sulfanilamide had failed [Van Slyke et al, 1941; Mahoney et al., 1941]. However, resistance emerged rapidly; by 1944, many N. gonorrhoeae strains exhibited clinical resistance, and by the late 1940s more than 90% of isolates were resistant in vitro [Kampmeier, 1983]. Consequently, sulfonamides were largely abandoned for gonorrhoea treatment with the advent of penicillin, although agents such as sulfamethoxazole often in combination with trimethoprim continued to be used for several decades, particularly in low-resource settings [Tapsall, 2001; Tapsall et al., 2009; Lewis, 2010].

8.2. Penicillin Resistance

The discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928 marked a major milestone in antimicrobial therapy. Shortly after, Cecil Paine successfully used a crude Penicillium notatum preparation to cure gonococcal ophthalmia in a newborn in 1930 [Wainwright and Swan, 1986]. However, penicillin’s efficacy against gonococcal urethritis was not firmly established until 1943, after which it rapidly displaced sulfonamides as the first-line therapy for gonorrhoea [Mahoney et al., 1943; Van Slyke et al., 1943]. Cure rates exceeded 95%, and initial effective doses were as low as 45 mg [Van Slyke et al., 1943]. Soon after its introduction, increasing MICs were reported as chromosomal resistance determinants accumulated, necessitating progressive dose escalation to maintain clinical efficacy [Unemo and Shafer, 2011; Lewis, 2010]. By 1946, penicillin treatment failures were documented in cases requiring 0.6–1.6 million units, and resistance was confirmed in vitro [Amies, 1967; Franks, 1946]. Despite these early reports, penicillin remained highly effective until the 1960s, when rising gonorrhoea incidence during the “sexual revolution” coincided with declining cure rates and frequent treatment failures [Unemo and Shafer, 2011; Shafer et al., 2010; Willcox, 1970]. The most significant development occurred in 1976, when penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (PPNG) strains were identified in the United States and the United Kingdom [Ashford et al, 1976; Phillips, 1976]. These isolates harboured small non-conjugative plasmids (3.2 MDa in West African strains and 4.4 MDa in East Asian strains) carrying TEM β-lactamase genes, genetically similar to those found in Haemophilus influenzae and Enterobacteriales [CDC, 2012; Bignell and Fitzgerald, 2011]. In some strains, β-lactamase plasmids were mobilized by a larger 24.5 MDa conjugative plasmid, facilitating horizontal gene transfer [CDC, 2012]. By 1977, PPNG had been reported in at least 16 countries, with molecular epidemiology revealing importation from Southeast Asia and West Africa [CDC, 2012]. By the late 1970s, the global spread of plasmid-mediated resistance, coupled with chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms (including reduced permeability and altered penicillin-binding proteins), rendered penicillin ineffective for first-line treatment of gonorrhoea [Unemo and Nicholas, 2012; Unemo and Shafer, 2011; Tapsall et al., 2009; Unemo et al., 2013; ]. Consequently, alternative antimicrobials were adopted for clinical management.

8.3. Tetracycline Resistance

The first tetracycline, chlortetracycline (Aureomycin), was discovered by Benjamin Minge Duggar in 1945. Tetracyclines were introduced for the treatment of gonorrhoea in the 1950s, particularly in patients allergic to penicillin or infected with strains showing reduced penicillin susceptibility. Their oral administration also provided a practical advantage over injectable penicillin. As with penicillin, decreased susceptibility to tetracyclines emerged over time due to the accumulation of chromosomal resistance determinants under selective pressure [Reyn et al., 1958]. The situation escalated in the mid-1980s with the identification of the tetM determinant, which conferred high-level resistance (MICs 16–64 mg/L) [Morse et al, 1986]. This gene was carried on a 25.2 MDa conjugative plasmid, generated through insertion of tetM into the 24.5 MDa gonococcal plasmid, and was transferable via both conjugation and transformation. The first isolates carrying plasmid-mediated tetM resistance were reported in 1986 in the United States and soon after in the Netherlands [Roberts et al., 1988]. These plasmid-mediated resistant strains subsequently disseminated worldwide, leading to tetracycline’s removal from treatment guidelines in many countries [Unemo and Shafer, 2011; Tapsall et al., 2009; Tapsall JW. 2001; Bala et al., 2013]. More recently, tetracyclines have been revisited in the context of doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxyPEP) to prevent bacterial STIs among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women. While doxyPEP showed high efficacy against Chlamydia trachomatis and Treponema pallidum, its effectiveness against gonorrhoea was inconsistent. In one trial, tetracycline resistance in N. gonorrhoeae isolates increased from 28.6% at baseline to 38.5% among doxyPEP users, although isolate numbers were limited. These findings suggest that doxyPEP is unlikely to provide a sustainable strategy for gonorrhoea prevention in regions with high baseline tetracycline resistance.

8.4. Spectinomycin Resistance

Spectinomycin, an aminocyclitol structurally related to aminoglycosides and first isolated from Streptomyces spectabilis in 1961, was introduced in the early 1960s as a specific therapy for gonorrhoea [Easmon et al., 1984; Judson et al., 1985]. It was widely adopted following the emergence of plasmid-mediated high-level penicillin resistance, particularly in military and clinical settings. In 1981, spectinomycin was implemented as a first-line therapy in U.S. military personnel stationed in South Korea [Ashford et al., 1981]. Although effective for treating uncomplicated genital and rectal gonorrhoea, spectinomycin showed reduced efficacy against pharyngeal infection, with cure rates of only ~80% [Lindberg et al., 1982; Moran and Levine, 1995]. Resistance was first documented in the Netherlands in 1967 in a penicillin-susceptible strain [Stolz et al., 1975], and subsequently in 1981 in the Philippines in a strain also carrying plasmid-mediated penicillin resistance. By the early 1980s, spectinomycin-resistant isolates were reported from South Korea and London, with treatment failure rates of up to 8.2% within just four years of clinical use [Boslego et al., 1987; Ison, 1983]. Global resistance levels remained relatively low, but limited drug availability from the 1990s onward restricted its use in many regions, including the United States [Dillon et al., 1999]. Currently, spectinomycin is rarely employed in routine treatment and is unavailable in many countries. Importantly, if reintroduced as a first-line therapy, the potential for rapid emergence of resistance remains a concern.

8.5. Quinolones Resistance

Synthetic quinolones were first developed in the 1960s as by-products of chloroquine synthesis, with nalidixic acid approved for urinary tract infections. All later quinolones, including the fluoroquinolones, descend from this compound. Ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin, introduced in the mid-1980s, became widely used for gonorrhoea treatment due to their oral administration and high initial efficacy [Gransden et al., 1990]. Ciprofloxacin was initially prescribed at 250 mg, but clinical failures were soon reported, and the recommended dose was increased to 500 mg. Similarly, ofloxacin was used at 400 mg. Nevertheless, resistance emerged rapidly, with treatment failures associated with isolates showing ciprofloxacin MICs ≥1 mg/L and ofloxacin MICs ≥2 mg/L [Goire et al., 2011]. Mechanistically, fluoroquinolone resistance in N. gonorrhoeae is caused by chromosomal mutations in the gyrA and gyrB genes (encoding DNA gyrase) and parC (encoding topoisomerase IV), which impair drug binding. Clinically significant resistance is primarily linked to mutations in gyrA and parC, and these mutations can be horizontally transferred between strains via transformation [Vernel-Pauillac and Merien, 2006; Vernel-Pauilla et al., 2008]. Ciprofloxacin resistance first emerged as a major clinical problem in Japan and the Western Pacific region in the early 1990s [Tapsal, 2001; Vernel-Pauilla et al., 2008], leading to phased withdrawal of fluoroquinolones from treatment guidelines in several Asian countries by the mid-to-late 1990s [Unemo and Shafer, 2011]. Resistant strains then spread globally, either through clonal expansion or independent local emergence [Berglund et al., 2002; Chisholm et al., 2010]. In the United States, ciprofloxacin-resistant gonococci were first detected in Hawaii in 2000 [Iverson et al., 2004] and rapidly spread to the West Coast and subsequently nationwide, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM) [CDC, 2003]. Consequently, the CDC removed fluoroquinolones from recommended gonorrhoea treatment regimens in 2007 [CDC, 2007]. Today, fluoroquinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae is highly prevalent worldwide, with resistance rates rendering this drug class unsuitable for empirical treatment in most regions [Unemo and Nicholas, 2012; Unemo and Shafer 2011; Tapsall et al., 2009; Lewis, 2010; Unemo et al.,2013].

8.6. Macrolides Resistance

Macrolides were first discovered in 1952 when erythromycin was isolated from Streptomyces erythraeus (now Saccharopolyspora erythraea) [McGuire et al., 1952]. Although erythromycin demonstrated antimicrobial activity, it was ineffective against Neisseria gonorrhoeae in both clinical and in vitro studies [Unemo et al., 2012; Wi et al., 2017]. A semisynthetic derivative, azithromycin, developed in the 1980s, exhibited enhanced anti-gonococcal activity and soon became a key component in sexually transmitted infection (STI) management [Kannan et al., 2014]. By the mid-to-late 1990s, declining azithromycin susceptibility and resistance were reported, particularly in Latin America where the drug was extensively used to treat bacterial STIs, including gonorrhoea and Chlamydia trachomatis infections [Starnino et al., 2012; Dillon et al., 2013]. Resistance subsequently spread across Europe and North America, with high-level azithromycin-resistant isolates (MIC ≥256 mg/L) documented in Scotland, England, Argentina, Italy, the United States, and Sweden [Chisholm et al., 2010; Fifer et al., 2016; Unemo and Shafer, 2014]. Despite its global use, azithromycin is not recommended as empirical monotherapy for gonorrhoea due to rapid resistance selection and adverse events associated with the high oral dose (2 g) required for effective treatment [Workowski and Bolan, 2015]. Nonetheless, it remains a critical component of dual-antimicrobial regimens [Workowski et al, 2021; WHO, 2021].

8.7. Azithromycin Resistance

Azithromycin, a semisynthetic 15-membered macrolide derived from erythromycin, was developed in 1980. Early studies demonstrated good activity against Neisseria gonorrhoeae, including penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (PPNG), with MIC₅₀ and MIC₉₀ values of 0.12 mg/L and 0.25 mg/L, respectively [Handsfield et al., 1994]. Due to its oral bioavailability and dual activity against N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, azithromycin was proposed as a treatment option for gonorrhoea in the early 1980s. However, by the mid-to-late 1990s, decreased susceptibility was first reported in Latin America [Starnino and Galarza, 2008], and azithromycin resistance subsequently emerged in many parts of the world [Unemo and Nicholas, 2012; Wi et al., 2017]. Although clinical cure rates for genital gonorrhoea remained high with single 2-g doses, resistance was increasingly detected, particularly when azithromycin was widely used for syndromic STI management. Mechanisms of Resistance: Resistance to azithromycin in N. gonorrhoeae involves multiple mechanisms: Target site modification: Mutations in the rrl alleles encoding 23S rRNA, particularly A2059G (A2143G in gonococcal numbering) and C2611T (C2599T), reduce drug binding. High-level resistance (MIC ≥256 mg/L) arises when A2059G occurs in three or four copies of the four rrl alleles [Chisholm et al., 2010]. Efflux pump overexpression: Mutations or deletions in the mtrR repressor gene or its promoter increase expression of the MtrCDE efflux pump, reducing intracellular drug concentrations [Shafer et al., 2016]. Azithromycin exerts its antimicrobial action by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit, inhibiting peptidyl transferase activity, blocking the peptide exit tunnel, and preventing peptidyl-tRNA translocation, thereby terminating protein synthesis [Poehlsgaard and Douthwaite, 2005; Kannan et al., 2014].The first high-level azithromycin-resistant gonococcal isolates (MIC >256 mg/L) were reported in Argentina in 2001 [Galarza et al., 2009] and subsequently detected in several sub-Saharan African countries. In 2015, the first outbreak of sustained national transmission of high-level azithromycin resistance was reported in England, associated with the A2059G mutation in multiple 23S rRNA alleles [Chisholm et al., 2010]. Similar isolates have since been reported across Europe, the USA, and Asia. Given the risk of rapid selection for resistance, azithromycin is no longer recommended as monotherapy for gonorrhoea. Nevertheless, it has been widely included in dual therapy regimens (e.g., ceftriaxone plus azithromycin), primarily to enhance treatment efficacy, cover possible C. trachomatis coinfection, and potentially delay resistance emergence [WHO, 2016; Workowski et al, 2021]. Recent WHO and CDC guidelines, however, are moving away from dual therapy with azithromycin, given rising global resistance rates and antimicrobial stewardship concerns.

8.8. Ceftriaxone Resistance

Ceftriaxone, a third-generation cephalosporin, has long been regarded as the most effective antimicrobial agent for the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. Its mechanism of action involves binding with high affinity to penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2), thereby inhibiting peptidoglycan cross-linking and ultimately disrupting bacterial cell wall synthesis [Cámara et al., 2012]. However, in recent years, decreased susceptibility and increasing resistance have been documented worldwide, with resistance rates approaching 30% in some regions [Goire et al., 2012]. Resistance to ceftriaxone is primarily mediated by mutations in the penA gene, which encodes an altered PBP2 with reduced binding affinity for cephalosporins [Bignell and Unemo, 2013; Goire et al., 2012]. Specific mosaic alleles of penA are strongly associated with elevated MICs (≥0.5 μg/mL, CDC breakpoint) and clinical treatment failure [Bignell and Unemo, 2013]. Additional resistance mechanisms include mutations in penB (altering porin permeability), mtrR (leading to overexpression of the MtrCDE efflux pump), and penC, which further enhance resistance levels [Goire et al., 2012]. The global emergence of ceftriaxone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae strains, coupled with the absence of novel treatment alternatives, prompted the introduction of dual therapy regimens, most notably the combination of ceftriaxone with azithromycin [Bignell and Unemo, 2013; Unemo and Nicholas, 2012; Workowski and Berman, 2010]. Nevertheless, the persistent spread of resistant clones highlights the pressing need for novel therapeutic agents and strengthened surveillance systems.

8.9. Cephalosporins Resistance

Cephalosporins were first identified in 1948, when Giuseppe Brotzu discovered Cephalosporium acremonium (now Acremonium chrysogenum) producing cephalosporin C [Brotzu, 1948]. The first clinically useful cephalosporin, cefalotin, was introduced in 1964 following chemical modification of this compound [Abraham and Newton, 1961]. With the widespread emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance in the 1990s, third-generation extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs), particularly ceftriaxone (injectable) and cefixime (oral), became the backbone of global gonorrhoea treatment guidelines [Unemo and Nicholas, 2012; Workowski et al., 2021; WHO, 2021]. Other oral ESCs such as cefditoren and cefdinir (Japan), cefuroxime (Europe), cefpodoxime (United States), and ceftibuten (Hong Kong) were occasionally used as alternatives to cefixime when availability was limited [Bauernfeind, 1991; Tapsall et al., 2009]. In Japan, reliance on multiple oral cephalosporins at suboptimal dosages throughout the 1990s such as cefixime 300 mg single-dose therapy instead of the 400 mg recommended elsewhere likely facilitated the emergence of cephalosporin resistance [Ito et al., 2004; Yokoi et al., 2007]. By the early 2000s, cefixime treatment failures were documented in Japan [Unemo et al., 2011; Yokoi et al., 2007] and subsequently in Europe, Canada, and South America [Ohnishi et al., 2011; Unemo et al., 2012; Allen et al., 2013]. Reports of ceftriaxone treatment failures, particularly for pharyngeal infections, soon followed from Japan, Europe, and Australia [Unemo et al., 2012; Fifer et al., 2016]. Mechanisms of Resistance: Resistance to ESCs in N. gonorrhoeae is primarily mediated by alterations in penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2), encoded by the penA gene. Mosaic penA alleles: Resistance-conferring alleles (e.g., penA-34, penA-60.001, penA-237.001) are generated through interspecies recombination with commensal Neisseria spp., producing structural changes in PBP2 that reduce cephalosporin binding [Ohnishi et al., 2011; Lefebvre et al., 2021]. Porin and efflux contributions: Mutations in porB (penB) decrease porin permeability, while mtrR regulatory mutations upregulate the MtrCDE efflux pump, lowering intracellular ESC concentrations [Veal et al.,2002; Olesky et al., 2006]. Initially, ceftriaxone-resistant isolates were sporadic, arising independently in Japan, Australia, and Europe without sustained transmission [Unemo et al., 2012]. However, the situation changed with the emergence of the FC428 clone, first described in Japan in 2015 and subsequently reported in Canada, Denmark, and Australia [Lahra et al., 2016; van der Veen, 2023]. FC428 carries the mosaic penA-60.001 allele and has spread internationally through multiple genomic backbones, indicating independent recombination events [van der Veen, 2023]. Alarmingly, the prevalence of ceftriaxone resistance has increased in Asia. Recent surveillance reported resistance rates of 8.1% in China (five provinces >10%) and 16% prevalence of ceftriaxone resistance among N. gonorrhoeae isolates in Hangzhou, China, with 6.7% exhibiting high-level resistance as well as 15–27% in Cambodia and Vietnam, associated with both penA-60.001 and novel mosaic alleles such as penA-237.001 [Yang et al., 2024; Laumen et al., 2025; EGASP, 2023]. In Europe, epidemiological links to Asia-Pacific travel were confirmed in resistant isolates identified in England, underscoring international dissemination [Eyre et al., 2019]. The discovery of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) N. gonorrhoeae strains in Japan (strain H041, Kyoto), France (strain F89, Quimper), and Spain (Catalonia), exhibiting high-level resistance to all ESCs and most other therapeutic options, highlights the imminent threat of untreatable gonorrhoea [Ohnishi et al., 2011; Unemo and Shafer, 2014; Eyre et al., 2019]. Fortunately, intensive surveillance in Japan after H041’s detection suggested limited community spread, possibly due to reduced biological fitness [Ohnishi et al., 2011]. Nevertheless, ceftriaxone remains the last reliable option for first-line monotherapy, and the continued emergence of XDR strains may herald an era of pan-resistant gonorrhoea.

9. Global Epidemiology and Resistance Trends

In the absence of a vaccine, gonorrhea management has relied exclusively on antimicrobial therapy for more than eight decades. However,

Neisseria gonorrhoeae has evolved resistance to nearly all previously and currently recommended drugs, including sulfonamides, penicillins, tetracyclines, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs) [Tapsall et al., 2009; Unemo, 2015; Unemo et al., 2016], are summarized in

Table 4. High-profile extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains such as H041 and F89, first reported in Japan, France, and Spain, exhibit resistance to cefixime, ceftriaxone, and multiple other agents [Ohnishi et al., 2011; Camara et al., 2012; Unemo et al., 2012; Allen et al., 2013]. Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 82.4 million new cases of gonorrhea in 2020, with the burden highest in low- and middle-income countries where diagnostic capacity is limited [WHO, 2024]. Adolescents and young adults (15–24 years) remain the most affected group due to behavioral, biological, and social risk factors [Chico et al., 2012; WHO, 2016]. Asymptomatic infections, particularly in women, and high-risk sexual practices sustain transmission. Incidence is highest in the WHO African, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific regions, though rising cases are also observed in Europe and North America, notably among men who have sex with men (MSM) [WHO, 2018; Orzechowska et al., 2022].

International travel further accelerates the global spread of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. Resistance patterns show striking geographic variation. Fluoroquinolone resistance is now near-universal, while azithromycin resistance rates exceed 5% in many regions, with particularly high prevalence in the United States, Europe, and China [Unemo et al., 2019]. Sporadic but significant reports of ceftriaxone-resistant isolates from Japan, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Southeast Asia underscore the fragility of current last-line therapies. Alarmingly, WHO-GASP surveillance data from participating countries indicate near-universal ciprofloxacin resistance (~100%), high azithromycin resistance (up to 80%), and increasing resistance to cefixime (≈45%) and ceftriaxone (≈24%) [Unemo et al., 2019; WHO-GASP, 2024]. To strengthen monitoring, WHO has established the Global Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (GASP) and the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS), which provide standardized frameworks for resistance reporting [GLASS, 2019]. Advances in molecular and genomic surveillance are increasingly used to detect resistance determinants, trace transmission networks, and anticipate emerging threats. Collectively, these trends highlight N. gonorrhoeae as a WHO Priority Pathogen [WHO, 2017]. Without coordinated global action, including sustained surveillance, novel therapeutic development, and alternative prevention strategies, the rise of MDR and XDR strains may lead to untreatable gonorrhea and severely undermine global control efforts.

10. Surveillance of Gonococcal AMR

The rapid evolution of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in

Neisseria gonorrhoeae underscores the need for systematic surveillance to guide treatment policies and public health interventions. Global initiatives such as the WHO’s Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (WHO-GASP) and regional networks including the U.S. Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) and Euro-GASP have been pivotal in tracking resistance patterns, informing guidelines, and detecting emerging MDR and XDR strains. These programs combine standardized phenotypic testing with increasingly sophisticated molecular tools to identify resistance mutations and high-risk lineages are summarized in

Table 5. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has further transformed surveillance by enabling high-resolution tracking of gonococcal populations, mapping resistance determinants, and uncovering transmission networks. Integrating WGS with epidemiological data supports predictive modeling of resistance evolution and early detection of emerging clones. Nevertheless, surveillance remains uneven, especially in resource-limited settings where culture capacity and molecular diagnostics are lacking. Strengthening laboratory infrastructure, harmonizing methodologies, and promoting timely global data sharing are essential for comprehensive coverage. Future priorities should include the integration of WGS with functional studies using

in vitro and

in vivo models to clarify mechanisms of virulence and resistance, as well as the development of biomarkers to detect hypervirulent or extensively drug-resistant clones. Such multidisciplinary approaches are critical to preempting outbreaks and guiding therapeutic and public health strategies.

11. Diagnostic Approaches: Conventional and Immuno-Molecular Methods

In addition to nucleic acid-based assays, several conventional and immuno-molecular strategies have been applied for the detection and characterization of N. gonorrhoeae.

11.1. Immunodetection

Antibody-based assays enable rapid and cost-effective detection of gonococcal antigens without requiring nucleic acid amplification. Early enzyme immunoassays (e.g., Gonozyme EIA) demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in male urogenital samples [Papasian et al., 1984], while monoclonal antibody-based tests (e.g., Phadebact) achieved >95% specificity but were hindered by cross-reactivity with commensal Neisseria species. Despite these limitations, immunodetection retains utility in resource-constrained settings, and ongoing refinements continue to improve its specificity and point-of-care (POC) applicability.

11.2. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry has emerged as a rapid, accurate method for species-level identification of N. gonorrhoeae. Beyond routine identification, MALDI-TOF has demonstrated potential for epidemiological applications, with resistant isolates clustering according to NG-MAST genogroups [Carannante et al., 2015]. More recently, innovative adaptations such as stable isotope labeling have enabled discrimination between resistant and susceptible strains within hours, showing strong concordance with MIC-based susceptibility testing and underscoring its promise for real-time AMR surveillance [Dadwal et al., 2023].

12. Treatment of N. gonorrhoeae Infections

12.1. Emerging Therapeutics

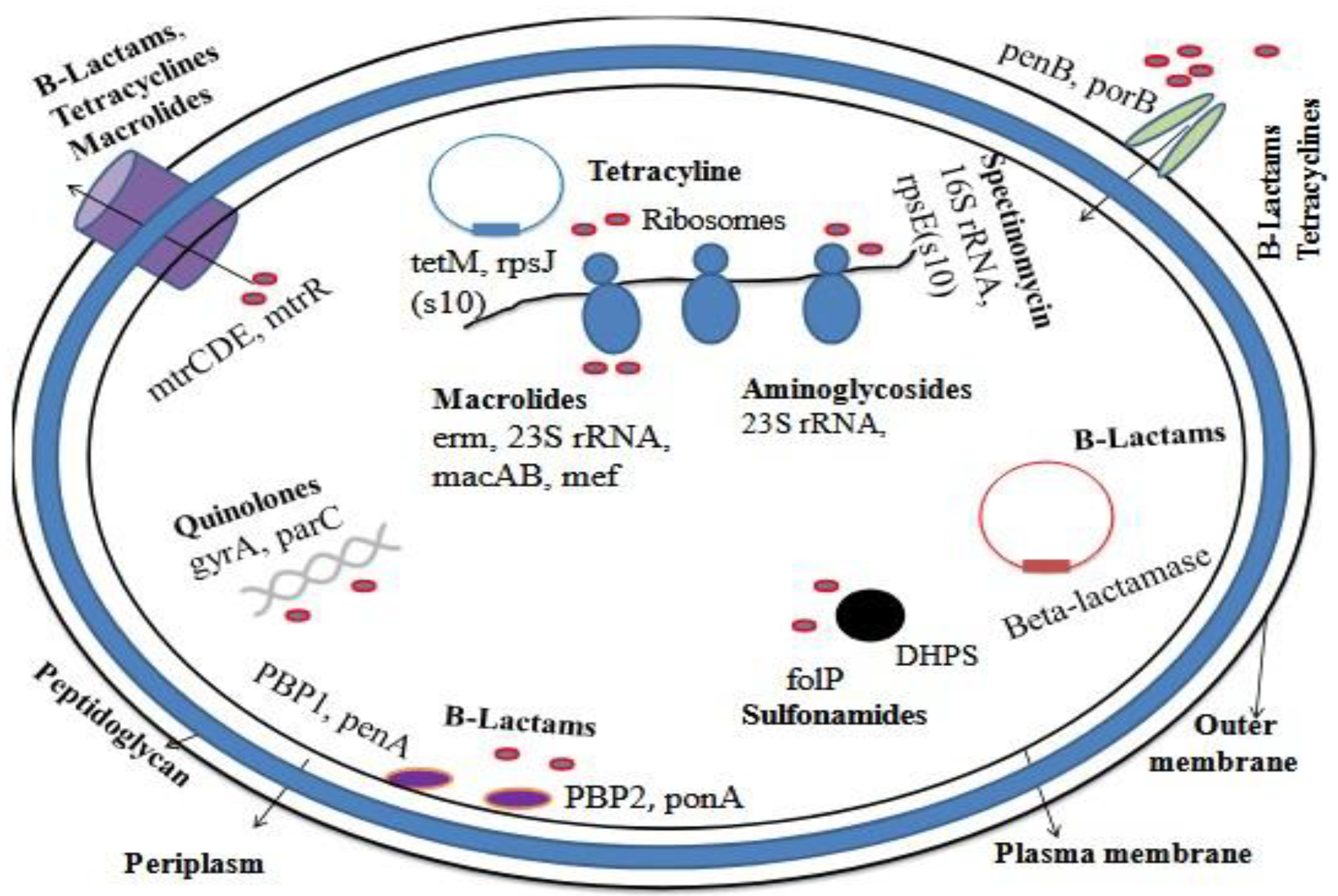

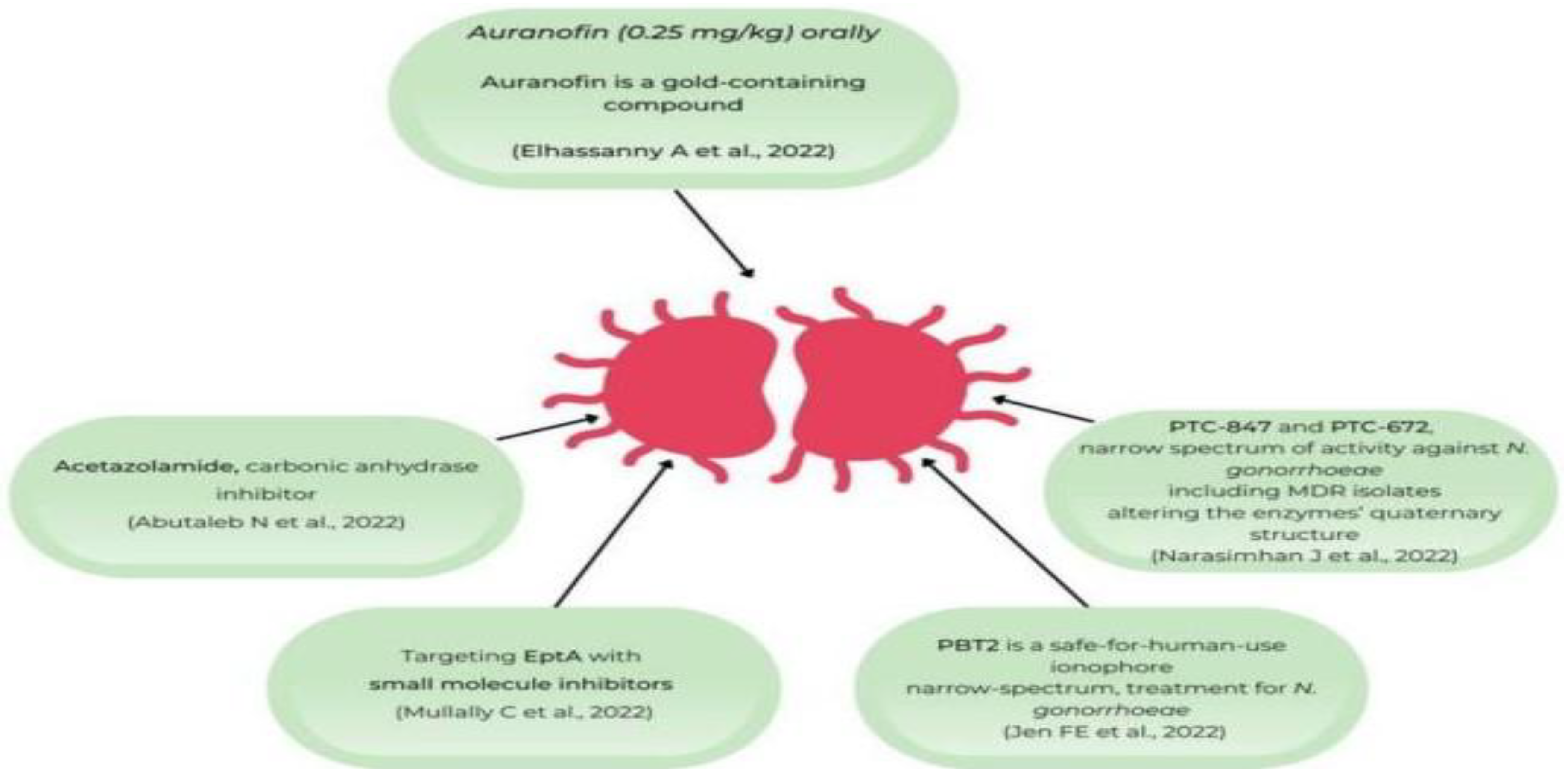

The urgent need for new treatment options against

N. gonorrhoeae is driven by escalating antimicrobial resistance and declining efficacy of current regimens. While several investigational agents have failed to achieve non-inferiority to ceftriaxone-based therapy, a number of promising candidates are in advanced development pipeline include zabofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone derivative), gepotidacin and zoliflodacin (novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors), solithromycin (a next-generation macrolide) and lefamulin (a pleuromutilin antibiotic) illustrated in

Figure 4.

12.2. Solithromycin

Solithromycin, a fluoroketolide macrolide structurally related to azithromycin, was designed to overcome ribosomal methylation and efflux-mediated resistance. It demonstrated potent in vitro activity and favorable early-phase trial outcomes. However, in a phase III trial, eradication rates (80%) did not achieve non-inferiority compared with ceftriaxone–azithromycin dual therapy (84%), and gastrointestinal side effects and hepatotoxicity limited its further development as a frontline agent [Lewis, 2019; Chen et al., 2019].

12.3. Delafloxacin

Delafloxacin, an anionic fluoroquinolone with dual targeting of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, exhibits broad-spectrum activity and stability under acidic conditions. Despite strong in vitro activity against multidrug-resistant isolates [Soge et al., 2019], a randomized clinical trial reported cure rates of 85% versus 91% for ceftriaxone, failing to meet non-inferiority criteria [Chen et al., 2019]. Given the global history of fluoroquinolone resistance, delafloxacin is currently considered investigational rather than a frontline option.

12.4. Zoliflodacin

Zoliflodacin (ETX0914), a first-in-class spiropyrimidinetrione, inhibits bacterial type II topoisomerases via a mechanism distinct from fluoroquinolones. Phase II trial data demonstrated 96% cure at urogenital sites and acceptable tolerability, although pharyngeal efficacy was slightly lower [Taylor et al., 2018]. A global phase III trial (NCT03959527) is underway to assess non-inferiority against ceftriaxone-based therapy [Wi et al., 2021].

12.5. Gepotidacin

Gepotidacin, a triazaacenaphthylene antibiotic, targets DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV through a novel binding interaction that avoids cross-resistance with fluoroquinolones. In phase II studies, single oral doses achieved >95% eradication at urogenital and rectal sites, though pharyngeal clearance was less consistent [Taylor et al., 2018]. A phase III multicenter trial (NCT04010539) is ongoing, directly comparing gepotidacin with ceftriaxone–azithromycin therapy [ClinicalTrials.gov, 2023]. If successful, gepotidacin would represent the first new oral treatment option for gonorrhea in decades.

13. Treatment of N. gonorrhoeae Infection

13.1. Historical Overview of Antimicrobials

The management of gonorrhea has evolved dramatically over the past century, reflecting both therapeutic innovation and the pathogen’s remarkable ability to develop resistance; a global at-a-glance comparison of current treatment and surveillance recommendations for

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is presented in

Table 6.

13.2. Sulfonamides

Sulfonamides represented the first effective systemic therapy for gonorrhea in the 1930s, producing high initial cure rates. However, resistance emerged rapidly within a few years, rendering them obsolete by the early 1940s [Hook and Kirkcaldy, 2018].

13.3. Penicillin and other β-Lactams

Penicillin G became the mainstay of gonorrhea treatment for nearly four decades, with escalating doses required over time as N. gonorrhoeae developed resistance through β-lactamase production and altered penicillin-binding proteins. By the late 1970s, penicillin resistance was widespread, leading to the adoption of alternative β-lactams such as ampicillin and spectinomycin. These, too, were eventually compromised by plasmid-mediated resistance and ribosomal mutations [Unemo and Shafer, 2014].

13.4. Tetracyclines and Macrolides

Tetracyclines were widely used in the 1960s and 1970s but lost utility due to high-level resistance mediated by efflux pumps and ribosomal protection proteins. Macrolides such as azithromycin were introduced in the 1990s, initially as monotherapy and later in dual therapy with ceftriaxone. However, azithromycin resistance has since risen to concerning levels globally, limiting its long-term role [Wi et al., 2021].

13.5. Fluoroquinolones

Ciprofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones gained prominence in the 1980s due to their oral efficacy, but resistance spread rapidly through gyrA and parC mutations. By the mid-2000s, fluoroquinolone resistance exceeded 20–30% in many regions, prompting global withdrawal from first-line recommendations [Deguchi and Nakane, 2010].

13.6. Cephalosporins

Third-generation cephalosporins, particularly ceftriaxone, became the cornerstone of gonorrhea treatment in the early 2000s. Dual therapy with ceftriaxone and azithromycin was recommended by the CDC and WHO to delay resistance development. Alarmingly, decreased susceptibility and treatment failures with ceftriaxone have been reported in Asia, Europe, and North America, underscoring the fragility of current regimens [Unemo et al., 2019].

13.7. Current Standard of Care

Today, high-dose ceftriaxone monotherapy (500–1000 mg intramuscularly) is the recommended regimen in most guidelines, with azithromycin no longer universally endorsed due to rising resistance. The emergence of extensively drug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae strains highlights the urgent need for novel therapies and continued surveillance [CDC, 2021; Unemo et al., 2020].

13.8. Dual therapy and Monotherapy Challenges

For more than a decade, dual therapy most notably ceftriaxone combined with azithromycin was recommended globally to enhance efficacy and delay resistance. This strategy provided synergistic bactericidal activity, lowered the risk of treatment failure, and offered partial coverage for undetected Chlamydia trachomatis coinfections [Workowski et al., 2015; Wi et al., 2021]. However, the rapid increase in azithromycin resistance and concerns about collateral damage to the human microbiome have undermined the long-term sustainability of this approach [Unemo et al., 2019]. In contrast, monotherapy with extended-spectrum cephalosporins (particularly ceftriaxone) has remained highly effective but faces increasing pressure. Reduced susceptibility and sporadic treatment failures associated with ceftriaxone highlight the pathogen’s capacity to accumulate mosaic penA alleles, mtrR promoter mutations, and porB alterations, which collectively compromise cephalosporin activity [Unemo and Shafer, 2014; Eyre et al., 2019].

Balancing between dual therapy and monotherapy has thus become a central challenge. While monotherapy with higher doses of ceftriaxone is currently the standard in several guidelines (e.g., CDC, ECDC, WHO), the absence of reliable partner drugs limits options if resistance continues to rise. The global scenario underscores the urgent need for novel antimicrobials, combination regimens with non-overlapping resistance mechanisms, and adjunctive approaches such as microbiome-sparing therapies and immunotherapeutics [Unemo et al., 2020; Unemo and Shafer, 2014].

13.9. Novel / Alternatives to Antibiotics

The accelerating spread of antimicrobial resistance in

Neisseria gonorrhoeae has prompted intensive investigation of therapeutic strategies beyond conventional antibiotics, and several innovative approaches currently under development are summarized in

Table 7. Phage therapy and lysins: Exploiting bacteriophage-derived enzymes for highly specific bacterial lysis [Olawade et al., 2024; Fischetti, 2018]. CRISPR-based antimicrobials: precision genome-editing tools designed to disrupt resistance determinants [Mayorga-Ramos et al., 2023]. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and synthetic mimics (SMAMPs): agents that damage bacterial membranes, alongside innate defense regulator (IDR) peptides that enhance host immune clearance [Mookherjee et al., 2020; Palermo et al., 2010]. Bacteriocins and probiotic strategies: natural microbial products and live biotherapeutics that suppress gonococcal colonization through competition or secretion of inhibitory compounds [Dobson et al., 2012; Maldonado-Galdeano et al., 2019]. Monoclonal antibodies and host-directed therapies: targeting gonococcal virulence factors or host pathways essential for infection [Tam et al., 1982; Demarco et al., 1986]. Anti-virulence agents: small molecules that disarm pathogens without exerting selective pressure for resistance [Rasko and Sperandio, 2010]. Plant-derived phytochemicals: a vast, underexplored reservoir of bioactive compounds with broad antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory potential, widely documented in traditional medicine [Savoia, 2012; Jadimurthy et al., 2023]. Collectively, these emerging strategies represent complementary or alternative solutions to conventional therapy and hold promise in mitigating the global threat of drug-resistant gonorrhoea.

14. Hypervirulent Neisseria gonorrhoeae

14.1. Defining Hypervirulence

Hypervirulent N. gonorrhoeae strains represent a growing concern due to their enhanced pathogenicity and frequent linkage with antimicrobial resistance. These strains demonstrate increased adherence and invasion of mucosal epithelium, greater resistance to complement-mediated killing, and improved immune evasion strategies, facilitating persistent infection and systemic dissemination [Unemo and Shafer, 2014; Quillin and Seifert, 2018; Lim et al., 2021]. Clinical reports highlight associations with disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), including septic arthritis and endocarditis. Clonal lineages such as ST-1901 and NG-MAST ST-1407 have been repeatedly implicated in global outbreaks and reduced susceptibility to extended-spectrum cephalosporins [Grad et al., 2014; Harris et al., 2018]. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has identified genetic signatures linked to hypervirulent phenotypes, particularly in porB, opa, pilE, and efflux pump systems [Echenique-Rivera et al., 2011; Sánchez-Busó et al., 2019].

14.2. Genetic and Phenotypic Determinants

Key molecular adaptations underlying hypervirulence include: PorB1b variants: Enhance resistance to complement-mediated killing [Massari et al., 2003]. Opa protein diversity: Promotes immune evasion and epithelial adhesion through phase variation [Stern et al., 1986; Sadarangani et al., 2011]. Phase-variable ModA methyltransferases: Epigenetically regulate virulence genes, influencing persistence and biofilm formation [Srikhanta et al., 2009]. MtrCDE efflux pump overexpression: Confers resistance to antimicrobials and hos peptides, enhancing bacterial fitness [Handing et al., 2018]. Enhanced iron acquisition (TbpA/B, LbpA/B): Supports proliferation in iron-limited host environments [Cornelissen and Hollander, 2011].Sialylated LOS: Mimics host glycans, enabling immune evasion and systemic spread [Gulati et al., 2015]. Collectively, these adaptations increase virulence, persistence, and treatment difficulty.

14.3. Clinical Implications

Hypervirulent strains pose significant clinical and public health challenges. They are disproportionately linked to DGI, prolonged asymptomatic carriage in urogenital and extra-genital sites, and higher rates of treatment failure when coupled with MDR and XDR phenotypes [Whiley et al., 2017; Wi et al., 2017]. Recent surveillance in Southeast Asia, Europe, and North America has identified hypervirulent XDR isolates, underscoring the urgent need for genomic surveillance, novel therapeutics, and strengthened global response strategies [Unemo et al., 2019; Eyre et al., 2022].

15. Neisseria gonorrhoeae Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic

15.1. Impact of COVID-19 Measures on Epidemiology and Testing

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted global healthcare systems, including the provision of sexual and reproductive health services. Public health measures such as lockdowns, social distancing, travel restrictions, and the repurposing of healthcare infrastructure contributed to sharp declines in sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and case detection. Worldwide, many countries reported substantial reductions in diagnostic capacity and surveillance for

Neisseria gonorrhoeae during the early phases of the pandemic. These disruptions likely resulted in underdiagnosis, missed opportunities for treatment, and continued undetected transmission, particularly among asymptomatic individuals. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on