Submitted:

05 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Globally Prevalent Resistant Sequence Types: ST1901 that is frequently associated with decreased susceptibility or resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, particularly ceftriaxone [15,16]. ST1901 has been identified in multiple countries across different continents, indicating its global spread [17].

- 2.

- Emerging Resistant Sequence Types: ST13871 associated with high-level azithromycin resistance, ST-13871 has been reported in multiple European countries and the United States [7,13]. ST14422 that Identified as a prevalent sequence type in some regions, ST14422 has been associated with resistance to multiple antibiotics, including tetracycline and ciprofloxacin [13,15]. ST11210 that has been linked to decreased susceptibility to extended-spectrum cephalosporins and resistance to fluoroquinolones in some studies [7,15] .

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Sample Collection

2.2. Bacterial Grow and Testing

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

2.4. Molecular Characterization Using NG-MAST Genotyping

3. Results

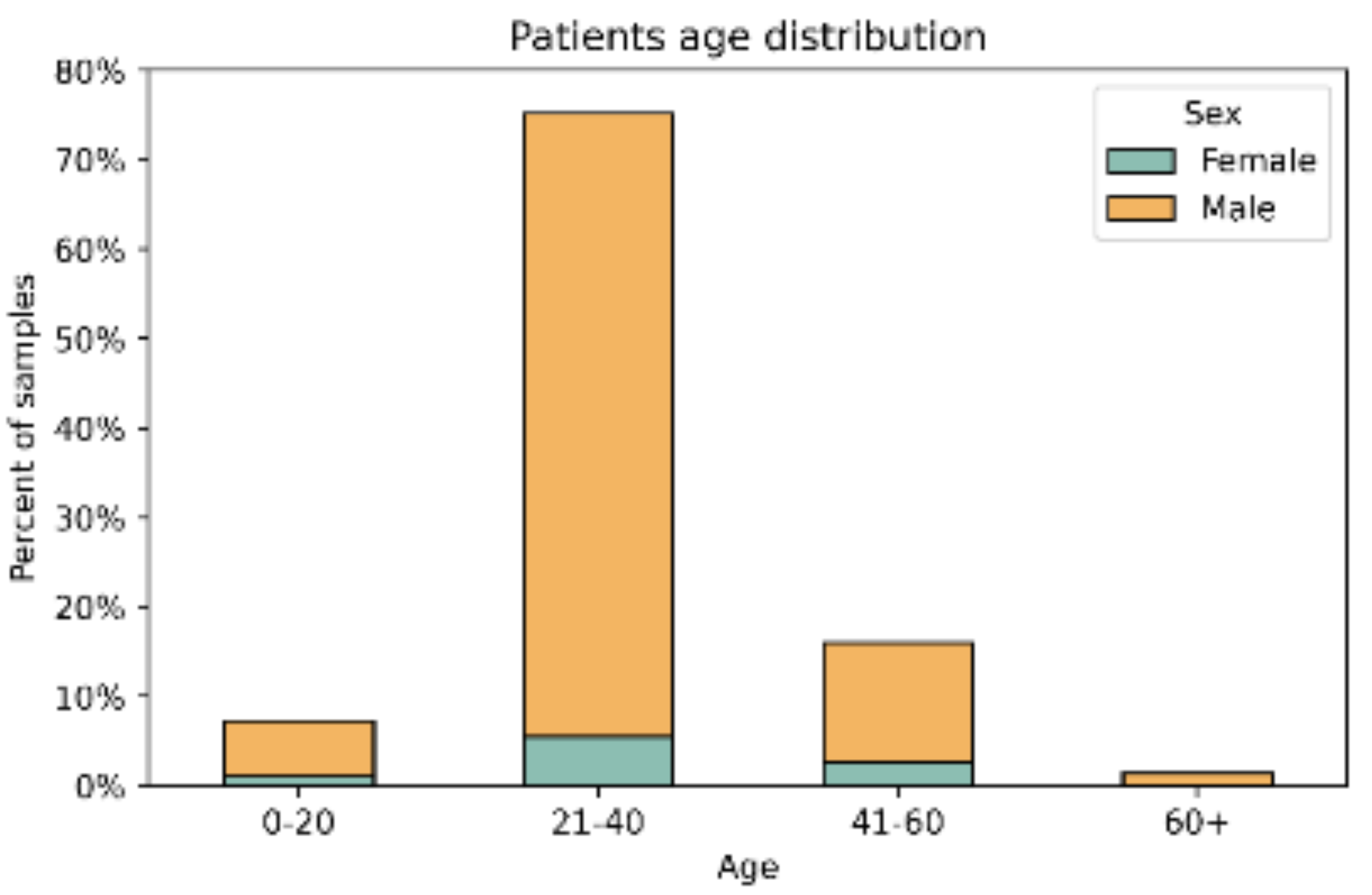

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Group

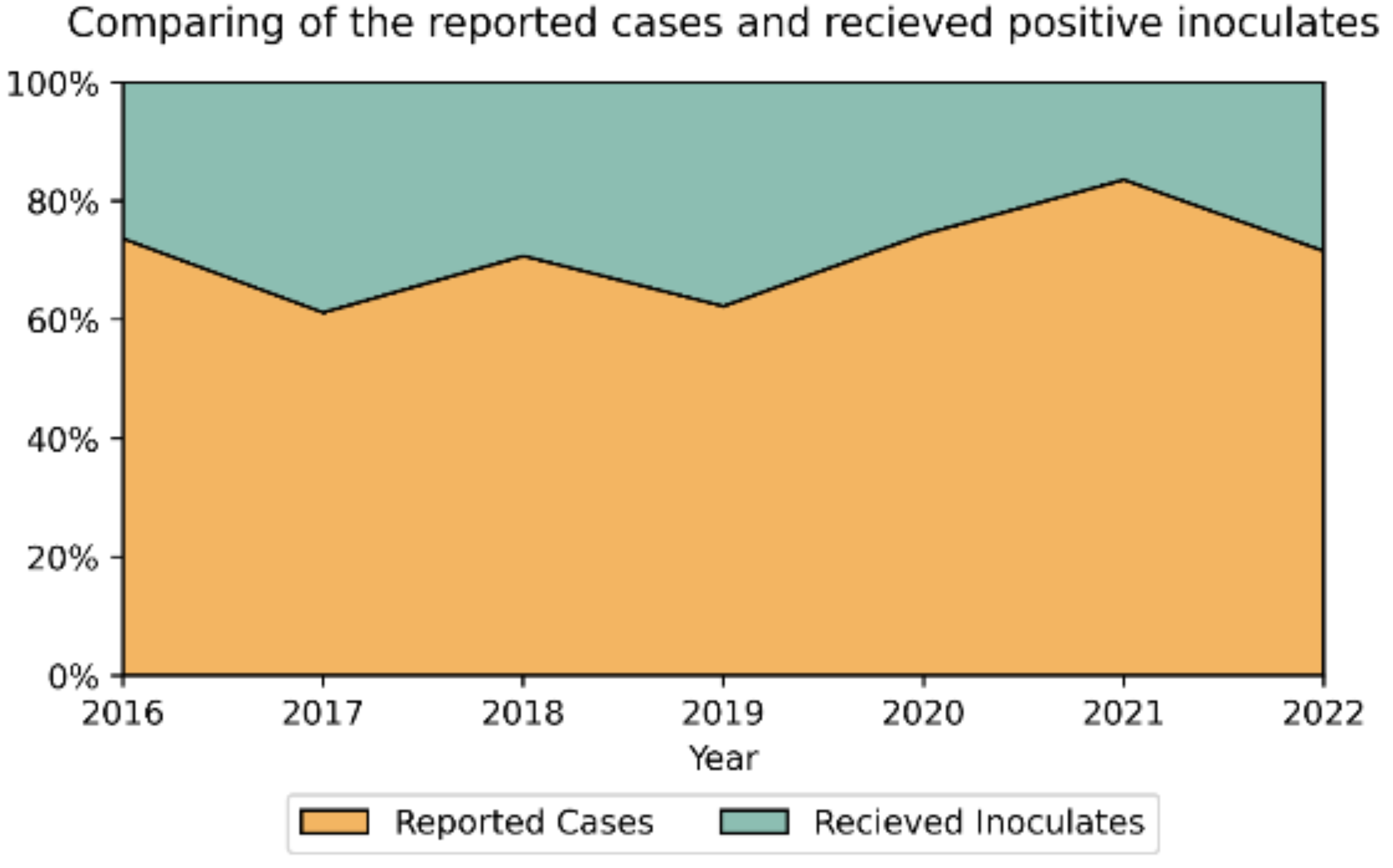

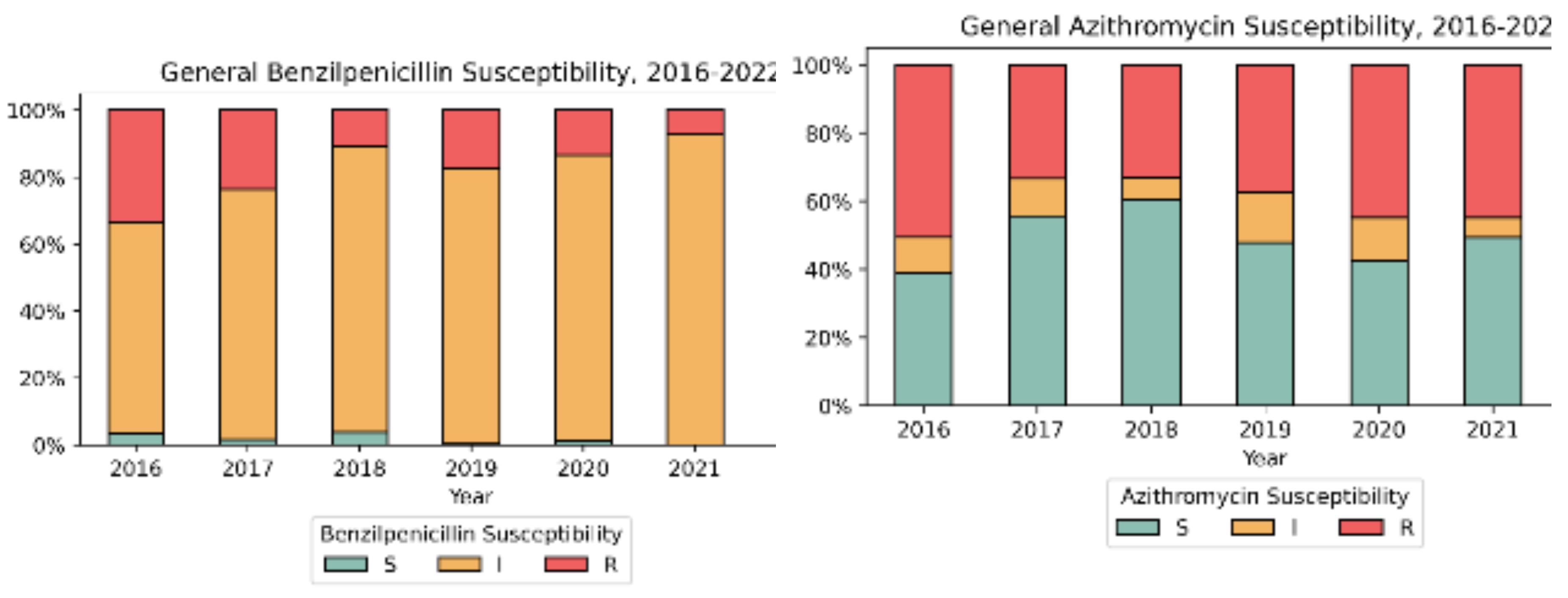

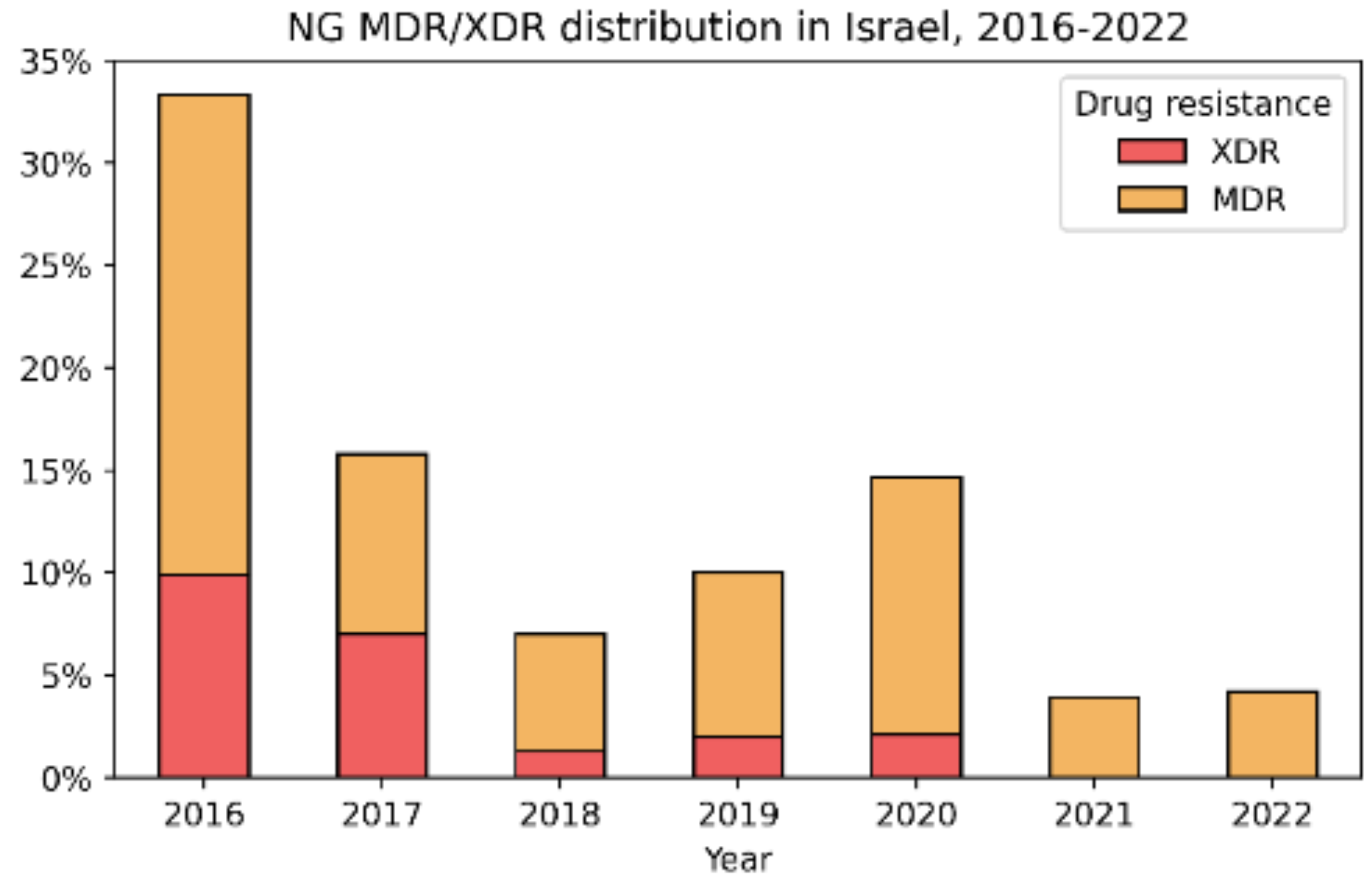

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

3.3. Molecular Characterization by NG-MAST Genotyping

4. Discussion

- Continuous importation of the pathogen through international travel

- Evolving sexual behaviors and practices

- Decreased condom use, potentially influenced by the increased adoption of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

- Expanded availability of anonymous testing facilities

- Establishment of dedicated sexual health clinics within HMOs, focusing on STI testing and treatment

- Genetic diversity: our NG-MAST results revealed a high diversity of sequence types, including several found in other countries, suggesting frequent importation [42].

- Fluctuations in AMR patterns: The variability in resistance profiles over time aligns more closely with changing patterns of imported strains rather than stable endemic transmission [43].

5. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Unemo M, Shafer WM. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st century: past, evolution, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;Jul;27(3):587-613. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Gonococcal antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance in Europe – Results summary 2017. Published online 2019.

- Barry P.; Klausner, J. The use of cephalosporins for gonorrhea: the impending problem of resistance. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2009, 10, 555-77. [CrossRef]

- Tapsall J. Multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. CMAJ, 2009, 180(3), 268–269. [CrossRef]

- Aniskevich A, Shimanskaya I, Boiko I. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates and gonorrhoea treatment in the Republic of Belarus, Eastern Europe, 2009–2019. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:520. [CrossRef]

- Ison CA, Hussey J, Sankar KN, Evans J, Alexander S. Gonorrhoea treatment failures to cefixime and azithromycin in England, 2010. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(14):19833. [CrossRef]

- Unemo M SW. Antimicrobial Resistance Expressed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae: A Major Global Public Health Problem in the 21st Century. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(3). [CrossRef]

- Unemo M SW. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st century: past, evolution, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(3)(3):587-613. [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in New Zealand 2022 surveillance Report. In: Report. The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd; 2023. https://www.esr.cri.nz/media/jt2f3hzt/esr-antimicrobial-resistance-in-neisseria-gonorrhoeae-surveillance-report-2022.pdf.

- Hooshiar MH, Sholeh M, Beig M, Azizian K, Kouhsari E. Global trends of antimicrobial resistance rates in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1284665. [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer J, Lippert K, Pleininger S, et al. Association of Phylogenomic Relatedness among Neisseria gonorrhoeae Strains with Antimicrobial Resistance. 2016;Aug;28(8):1694-1698. [CrossRef]

- Kakooza F, Kiggundu R, Mboowa G, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance and antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Africa from 2001 to 2020: A mini-review. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:2023.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Molecular Typing of Neisseria Gonorrhoeae – Results from a Pilot Study 2010–2011. ECDC; 2012. [CrossRef]

- Martin IM, Ison CA, Aanensen DM, Fenton KA, Spratt BG. Rapid sequence-based identification of gonococcal transmission clusters in a large metropolitan area. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(8):1497-1505. [CrossRef]

- Hadad R, Golparian D, Velicko I, et al. First National Genomic Epidemiological Study of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Strains Spreading Across Sweden in 2016. Front Microbiol. 2022;v.12. [CrossRef]

- Agbodzi B, Duodu S, Dela H, et al. Whole genome analysis and antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from Ghana. Front Microbiol. Published online June 29, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mitchev N, Singh R, Allam M, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms, Multilocus Sequence Typing, and NG-STAR Sequence Types of Diverse Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolates in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021;17;65(10):e0075921. [CrossRef]

- Yahara K, Ma KC, Mortimer TD. Emergence and evolution of antimicrobial resistance genes and mutations in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Genome Med. 2021;13:51. [CrossRef]

- Zimbro MJ. Difco & BBL manual: manual of microbiological culture media. BD Diagnostic; 2013.

- Carroll KC. Manual of clinical microbiology. 12th ed. ASM Press; 2019.

- Protect Microorganism Preservation System Store it, preserve it, protect it. www.tscswabs.co.uk/uploads/images/PDF-Downloads/TSC_ProtectFlyerV5.pdf.

- Ng LK, Martin IE. The laboratory diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Can J Infect Med Microbiol. 2005;16(1):15-25. [CrossRef]

- ETEST, Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing Reagent Strips to Determine On-Scale MICs. www.biomerieux-usa.com/sites/subsidiary_us/files/prn_056750_rev_03.a_etest_brochure_final_art_2.pdf.

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version. 2022;12(0). http://www.eucast.org.

- National surveillance of antimicrobial susceptibilities of Neisseria gonorrhoeae annual summary 2019. Published online 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/drugs-health-products/national-surveillance-antimicrobial-susceptibilities-neisseria-gonorrhoeae-annual-summary-2019.html.

- Nextera® DNA Library Prep Reference Guide. https://support.illumina.com/content/dam/illumina-support/documents/documentation/chemistry_documentation/samplepreps_nextera/nexteradna/nextera-dna-library-prep-reference-guide-15027987-01.pdf.

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data [Online]. Published online 2010. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Epub 2014 Apr 1 PMID 24695404 PMCID PMC4103590. 2014;1;30(15):2114-20. [CrossRef]

- Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;May;19(5):455-77. [CrossRef]

- Chemtob D. A national strategic plan for reducing the burden of sexually transmitted infections in Israel by the year 2025. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2017;6:23. [CrossRef]

- M. D, Z. M, S. G, B. S, T S. Trends in Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Israel, 2002 to 2007, With Special Reference to Fluoroquinolone Resistance. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(7):451-453.

- Green M, Anis E, Gandacu D, Grotto I. The fall and rise of gonorrhoea incidence in Israel: an international phenomenon? Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(2):116-118. [CrossRef]

- Kridin K, Ingram B, Becker D, et al. Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Northern Israel: Insights From a Large Referral Laboratory. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;1;27(1):51-55.

- Walker CK, Sweet RL. Gonorrhea infection in women: prevalence, effects, screening, and management. Int J Womens Health. 2011;3:197-206. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sánchez M. Clinical presentation of asymptomatic and symptomatic women who tested positive for genital gonorrhoea at a sexual health service in Melbourne, Australia. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:240. [CrossRef]

- Levi I, Mor Z, Anis E. MSM, risk behavior and HIV infection: integrative analysis of clinical, epidemiological and laboratory databases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;51(11):1363-1370. [CrossRef]

- Meyer T, Buder S. The Laboratory Diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Current Testing and Future Demands. Pathogens. 2020;9:91. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem KG. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in adults and adolescents. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-neisseria-gonorrhoeae-infection-in-adults-and-adolescents.

- Global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021, WHO. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/246296/WHO-RHR-16.09-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Chidiac O, AlMukdad S, Harfouche M, Harding-Esch E, Abu-Raddad LJ. Epidemiology of gonorrhoea: systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions, World Health Organization European Region, 1949 to 2021. Euro Surveill. 2024;29((9):2300226). [CrossRef]

- Clifton S, Bolt H, Mohammed H, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with MDR Neisseria gonorrhoeae in England and Wales between 2004 and 2015: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveillance surveys. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(4):923-932. [CrossRef]

- Harris SR, Cole MJ, Spiteri G, et al. Public health surveillance of multidrug-resistant clones of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Europe: a genomic survey. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(7):758-768. [CrossRef]

- Kirkcaldy RD, Weston E, Segurado AC, Hughes G. Epidemiology of gonorrhoea: a global perspective. Sex Health. 2019;16(5):401-411. [CrossRef]

- Wi T, Lahra MM, Ndowa F, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Global surveillance and a call for international collaborative action. PLoS Med. 2017;17(7). [CrossRef]

- Unemo M, Lahra MM, Cole M, et al. World Health Organization Global Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (WHO GASP): review of new data and evidence to inform international collaborative actions and research efforts. Sex Health. 2019;16(5):412-425. [CrossRef]

- Williamson DA CM. Emerging and Reemerging Sexually Transmitted Infections. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2023-2032. doi:doi:10.1056/NEJMra1907194.

- Cole. The European gonococcal antimicrobial surveillance program (Euro-GASP) appropriately reflects the antimicrobial resistance situation for Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the European Union/ European Economic Area. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1040). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global action plan to control the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Published online 2012. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44863.

- World Health Organization. Enhanced Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (EGASP): general protocol. Published online 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1347568/retrieve.

- Kirkcaldy RD, Kidd S, Weinstock HS, Papp JR, Bolan GA. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the USA: the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), January 2006-June 2012. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(4):5-10. [CrossRef]

- Lahra MM, Hogan TR, Shoushtari M, Armstrong BH. Australian Gonococcal Surveillance Programme Annual Report, 2020. Commun Intell. Published online 2018:45. [CrossRef]

- García UI. Epidemiological surveillance study of gonococcal infection in Northern Spain. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clın. 2020;38(2):59-64. [CrossRef]

- Młynarczyk-Bonikowska, B., Majewska, A., Malejczyk, M. et al. Multiresistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a new threat in second decade of the XXI century. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2020;209:95-108. [CrossRef]

- Martin I, Sawatzky P, Allen V. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Canada, 2012-2016. Can Commun Rep. 2019;45(2-3):45-53. [CrossRef]

- ASSESSMENT RAPIDRISK. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Extensively Drug-Resistant (XDR) Neisseria Gonorrhoeae in the United Kingdom and Australia – 7 May 2018. ECDC; 2018.

- Maubaret C, Caméléna F, Mrimèche M, et al. Two cases of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection combining ceftriaxone-resistance and high-level azithromycin resistance. Euro Surveill. Published online May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chisholm SA, Unemo M, Quaye N, et al. Molecular epidemiological typing within the European Gonococcal Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Programme reveals predominance of a multidrug-resistant clone. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(3). http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20358.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Gonococcal antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance in Europe, 2011. Published online 2013. [CrossRef]

- Kandinov I, Dementieva E, Kravtsov D, et al. Molecular Typing of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Clinical Isolates in Russia, 2018-2019: A Link Between penA Alleles and NG-MAST Types. Pathogens. 2020;9(11):941. [CrossRef]

- Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) and Enhanced GISP (eGISP), 2021. Published online 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gisp/gisp-egisp-protocol-august-2021.pdf.

- Kirkcaldy RD, Harvey A, Papp J. Neisseria gonorrhoeae Antimicrobial Susceptibility Surveillance — The Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, 27 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(SS-7):1-19. [CrossRef]

| Year | Number of isolates | Ratio male-to-female | Median Age Female/ Male |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 111 | 14.7 | 27/29 |

| 2017 | 228 | 6.8 | 31/30 |

| 2018 | 157 | 5.8 | 31/29 |

| 2019 | 200 | 14.6 | 41/31 |

| 2020 | 143 | 16.1 | 46/29 |

| 2021 | 152 | 8.9 | 33/28.5 |

| 2022 | 214 | 15.3 | 30/32 |

| All years | 1205 | 10* | 33*/30* |

| 12.3** | 32/30** |

| No | Year | Number o fisolates |

Resistance* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIX | AZI | TET | BEN | SPE | CIP | CTR | |||

| 1 | 2016 | 111 | 20 (18.0%) | 56 (50.5%) | 50 (46.3%) | 37 (33.3%) | 0 | 79 (71.2%) | 0 |

| 2 | 2017 | 228 | 38 (16.7%) | 76 (33.3%) | 58 (25.4%) | 54 (23.7%) | 0 | 105 (46.1%) | 0 |

| 3 | 2018 | 157 | 18 (11.5%) | 52 (33.1%) | 36 (22.9%) | 17 (10.8%) | 0 | 62 (39.5%) | 0 |

| 4 | 2019 | 200 | 14 (7.0%) | 75 (37.5%) | 56 (28.0%) | 35 (17.5%) | 0 | 109 (54.5%) | 0 |

| 5 | 2020 | 143 | 11 (7.7%) | 64 (44.8%) | 43 (30.1%) | 19 (13.3%) | 0 | 105 (73.4%) | 0 |

| 2021 | 152 | 2 (1.3%) | 68 (44.7%) | 36 (23.7%) | 11 (7.2%) | 0 | 85 (55.9%) | 0 | |

| 2022 | 214 | 2 (0.9%) | 106 (49.5%) | 53 (24.8%) | 18 (8.4%) | 0 | 111 (51.9%) | 0 | |

|

Total (Ave%±SD) |

1205 | 105 (8.7% ± 6.3) | 497 (41.2% ± 7.1) | 332 (27.6% ± 8.7) | 191 (15.9% ± 9.6) | 0 | 656 (54.4% ± 13.4) | 0 | |

| Year | Number of isolates |

Number of NG-MAST | Most common NG-MAST ST (number of isolate)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 78 | 72 | ST4269 (13), ST2318 (7), ST2997 (7), ST5441 (6), ST5049 (5), ST292 (4), ST5624 (4) |

| 2018 | 77 | 72 | ST292 (12), ST5441 (6), ST16169 (6), ST2992 (5), ST11547 (5), ST11461 (4) |

| 2022 | 124 | 72 | ST19665 (31), ST11461 (25), 14994 (10), 19762 (10), 17972 (8), 14764 (5) |

| Total | 279 | 72 | ST19665 (31), ST11461 (30), ST4269 (16), ST292 (16), ST14994 (14), ST5441 (13), ST19762 (10), ST2318 (9), ST17972 (8), ST2992 (7), ST11547 (7), ST2997 (7), ST16169 (6), ST5049 (5), ST9208 (5), ST14764 (5), ST3935 (4), ST14760 (4), ST14051 (4), ST5624 (4), ST12302 (4) |

| NG-MAST | n* | MDR,% | XDR,% | CIP** | BEN** | TET** | AZI** | CIX** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19665 | 31 | 0 | 0 | S(96.8%) R(3.2%) |

I | S(3.2%) I(93.5%) R(3.2%) |

S(9.7%) R(90.3%) |

S(96.8%) R(3.2%) |

| 11461 | 30 | 0 | 0 | S(83.3%) R(16.7%) |

I | S(3.3%) I(13.3%) R(83.3%) |

S(86.7%) R(13.3%) |

S |

| 292 | 16 | 0 | 0 | S | I | S(25.0%) I(75.0%) |

S(87.5%) I(6.2%) R(6.2%) |

S |

| 4269 | 16 | 29.4 | 64.7 | R | I(17.6%) R(82.4%) |

I(5.9%) R(94.1%) |

I(5.9%) R(94.1%) |

S(29.4%) R(70.6%) |

| 14994 | 14 | 0 | 0 | R | I(92.9%) R(7.1%) |

S(50.0%) I(50.0%) |

S(85.7%) I(7.1%) R(7.1%) |

S |

| 5441 | 13 | 0 | 0 | S | S(7.7%) I(92.3%) |

S | S(30.8%) I(30.8%) R(38.5%) |

S |

| 19762 | 10 | 10 | 0 | R | I | S(10.0%) I(80.0%) R(10.0%) |

S(20.0%) R(80.0%) |

S |

| 2318 | 9 | 45.5 | 9.1 | S(9.1%) R(90.9%) |

I(81.8%) R(18.2%) |

I(18.2%) R(81.8%) |

S(27.3%) R(72.7%) |

S(90.9%) R(9.1%) |

| 17972 | 8 | 12.5 | 0 | R | I | I(87.5%) R(12.5%) |

S(25.0%) R(75.0%) |

S |

| 2997 | 7 | 0 | 0 | S | I | I(71.4%) R(28.6%) |

I(14.3%) R(85.7%) |

S |

| 2992 | 7 | 0 | 0 | S(85.7%) I(14.3%) |

I | S(14.3%) I(85.7%) |

I(28.6%) R(71.4%) |

S |

| 11547 | 7 | 14.3 | 0 | R | I(85.7%) R(14.3%) |

S(28.6%) I(71.4%) |

S(71.4%) I(14.3%) R(14.3%) |

S(14.3%) R(85.7%) |

| 16169 | 6 | 0 | 0 | R | I | S(33.3%) I(66.7%) |

S(66.7%) R(33.3%) |

S |

| 9208 | 5 | 0 | 0 | S | I | S(40.0%) I(60.0%) |

S(40.0%) I(20.0%) R(40.0%) |

S |

| 5049 | 5 | 0 | 0 | S | I | I(80.0%) R(20.0%) |

R | S |

| 14764 | 5 | 0 | 0 | R | I | I | R | S |

| 14760 | 4 | 0 | 0 | S | S(25.0%) I(50.0%) R(25.0%) |

S(50.0%) I(50.0%) |

S | S |

| 12302 | 4 | 50 | 0 | I(25.0%) R(75.0%) |

I | I(50.0%) R(50.0%) |

R | S |

| 14051 | 4 | 50 | 0 | R | I | I(25.0%) R(75.0%) |

S(50.0%) R(50.0%) |

S |

| 5624 | 4 | 50 | 0 | R | I(50.0%) R(50.0%) |

I | R | S |

| 3935 | 4 | 0 | 0 | S | I | I | R | S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).