Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

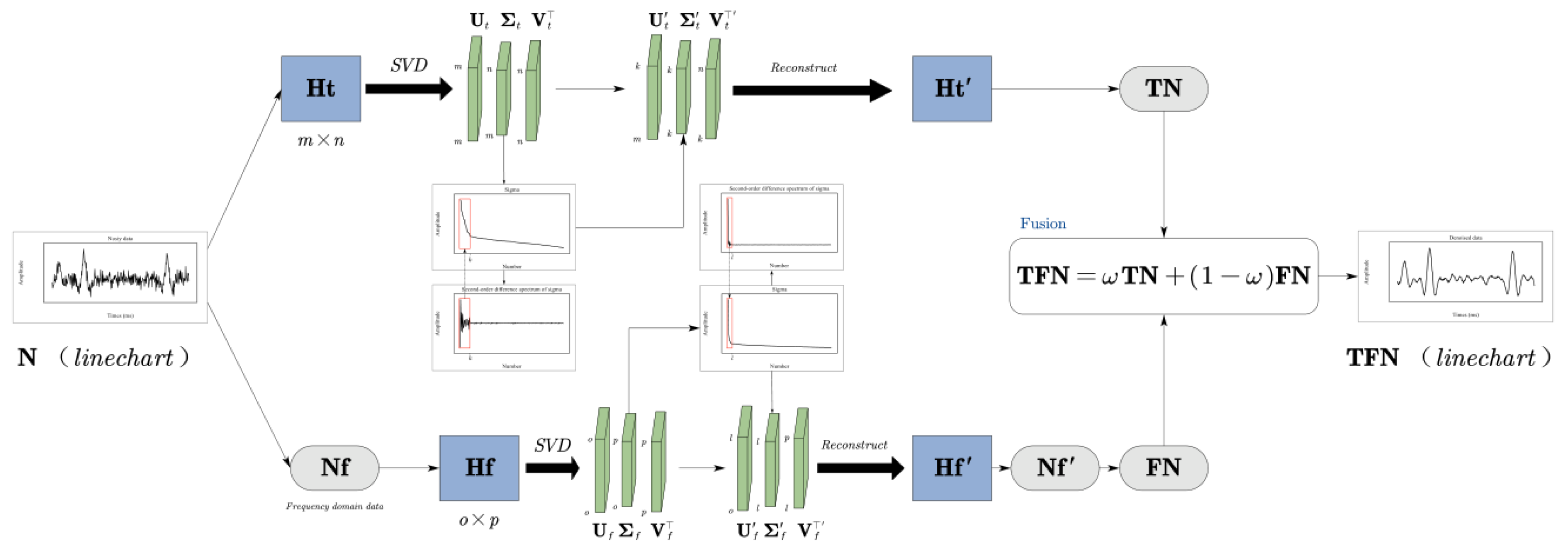

2. Theory

2.1. SVD Denoising

2.2. Frequency Domain SVD Denoising

2.3. Adaptive Selection of Singular Values

2.4. Adaptive Weight Fusion

3. Experiments

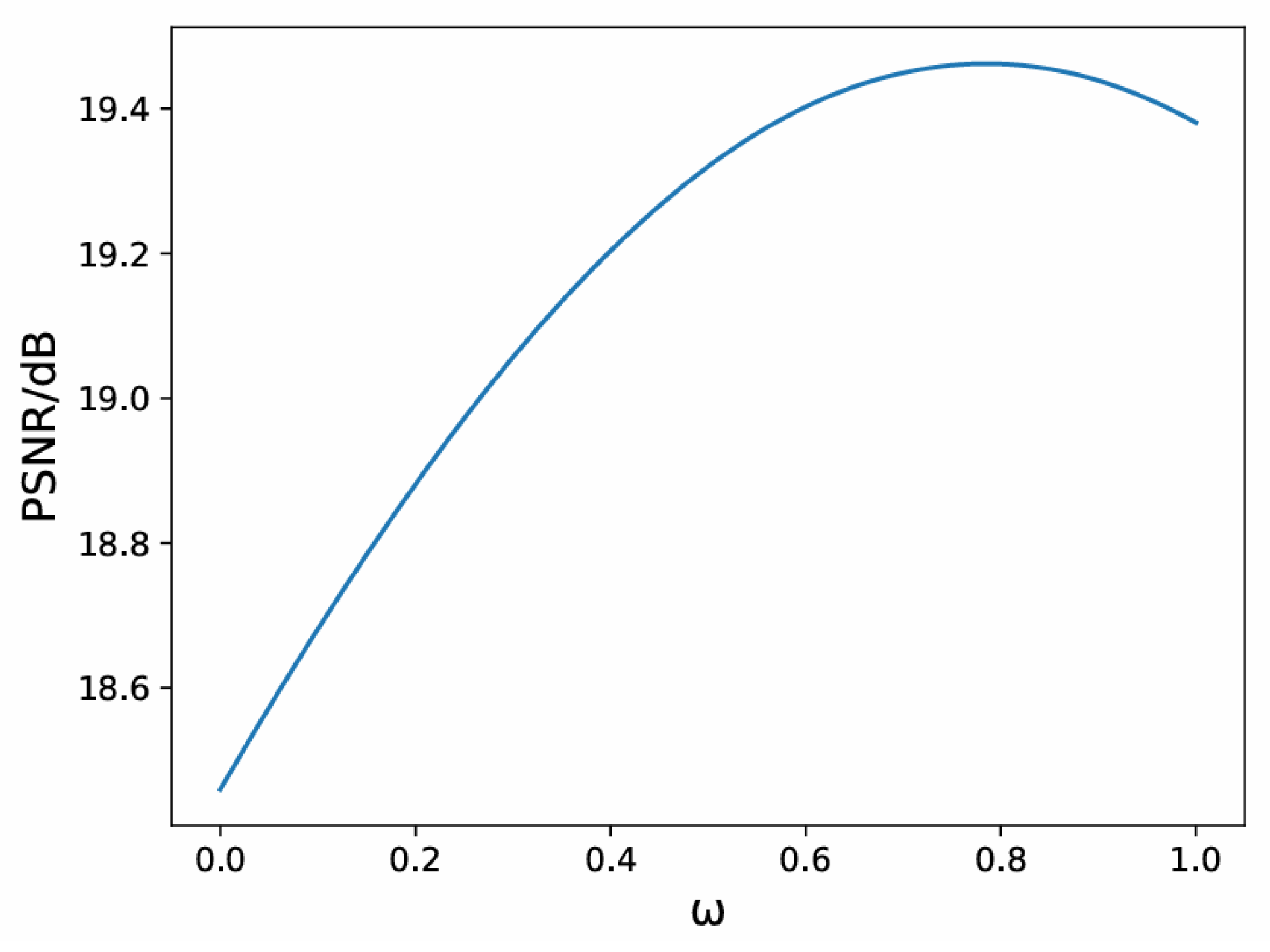

3.1. Adaptive Weight Fusion

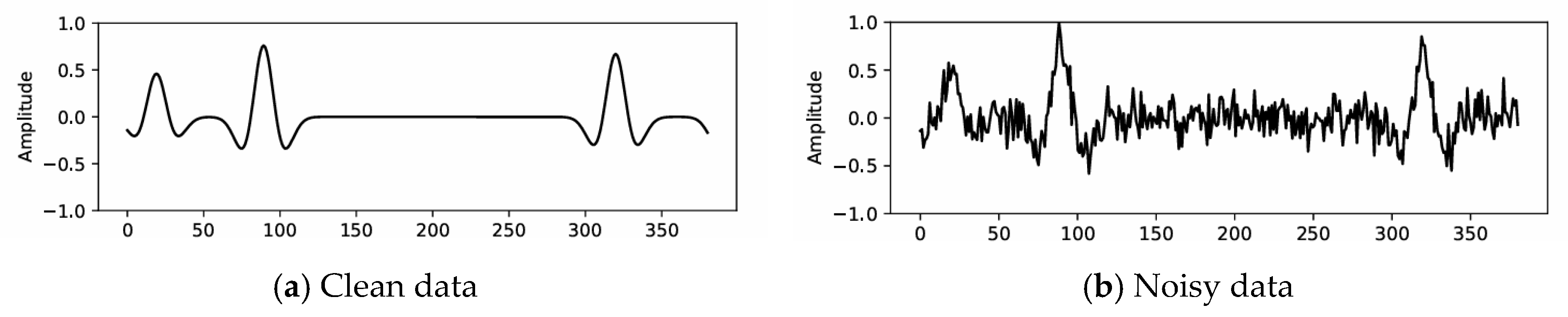

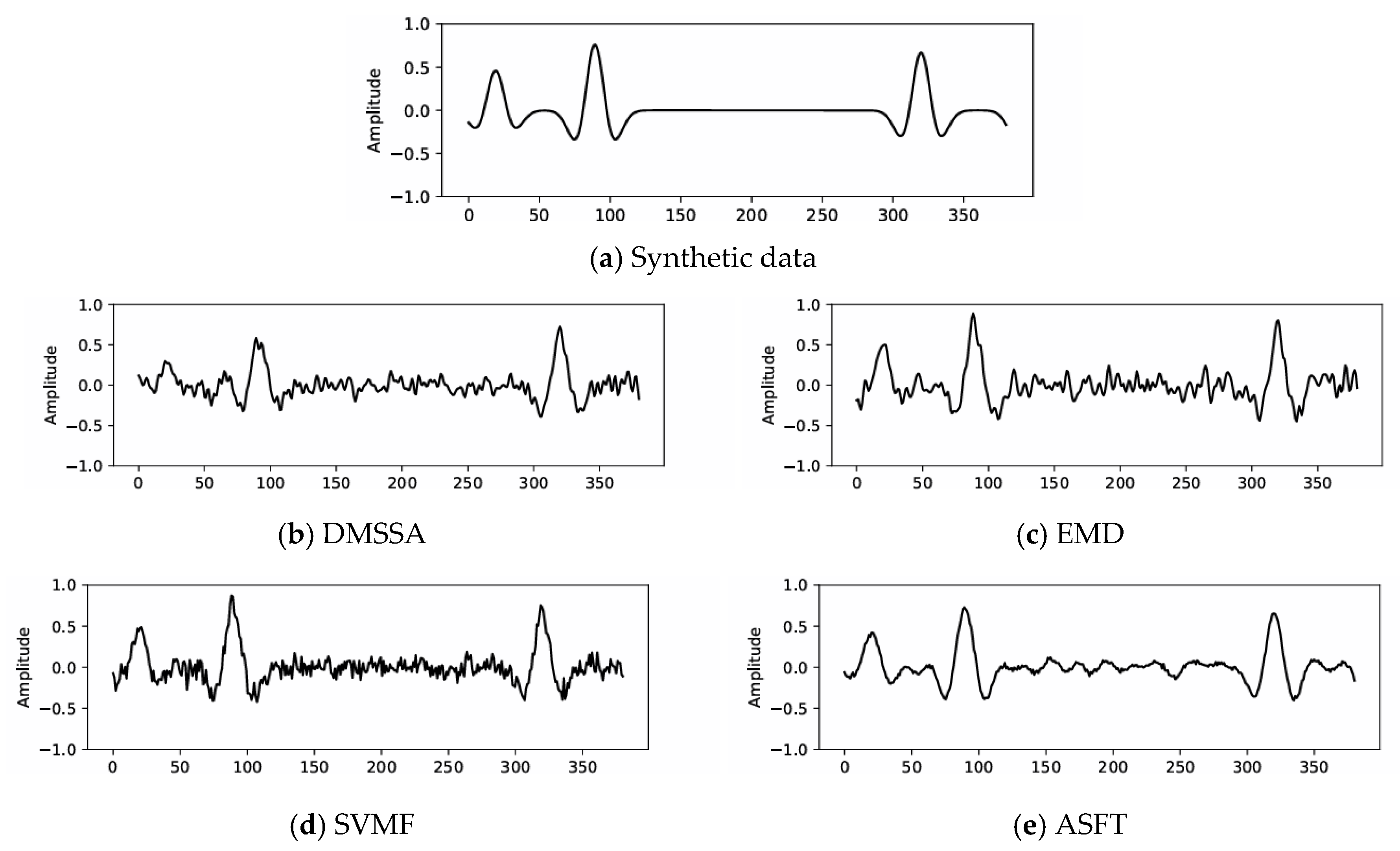

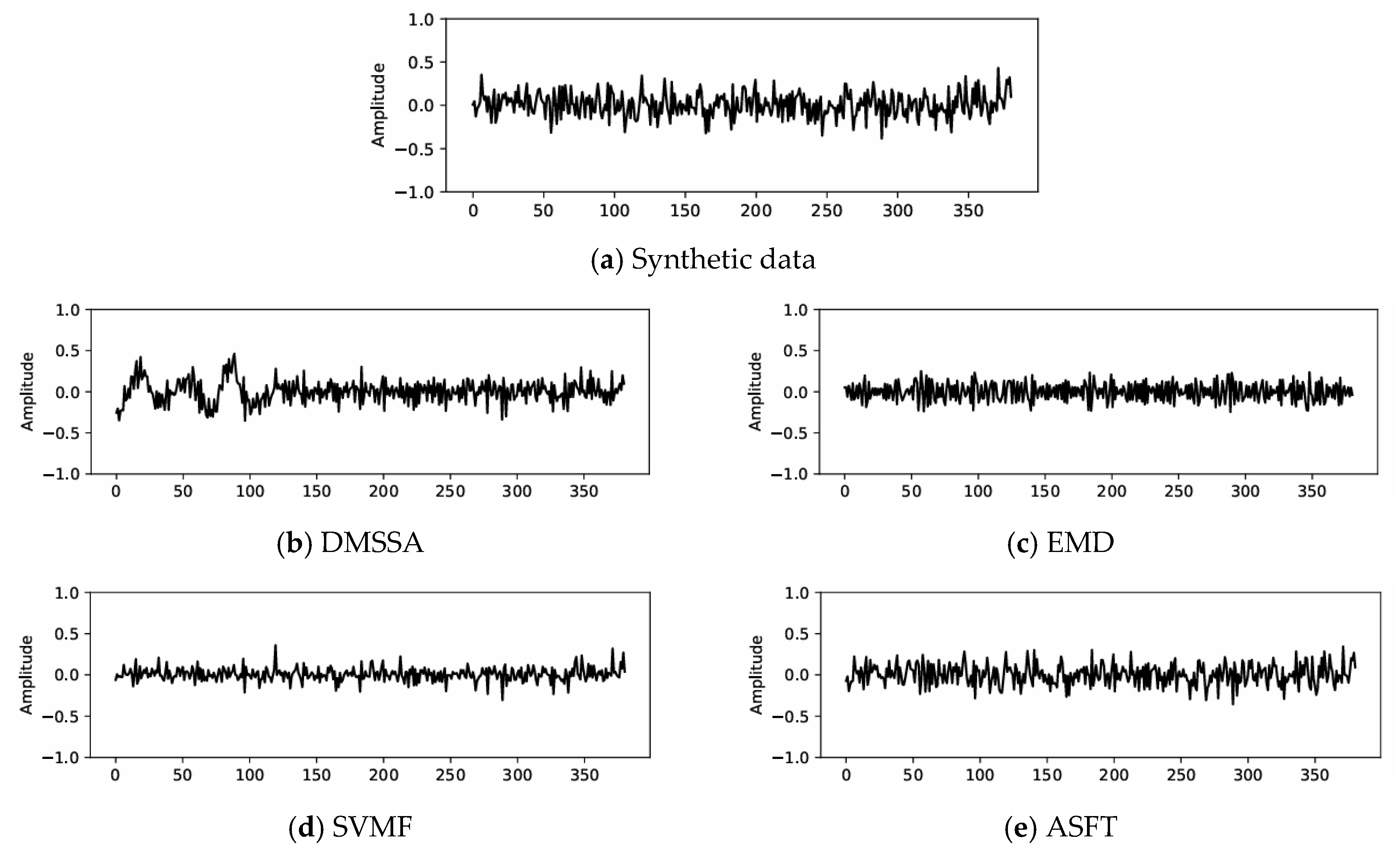

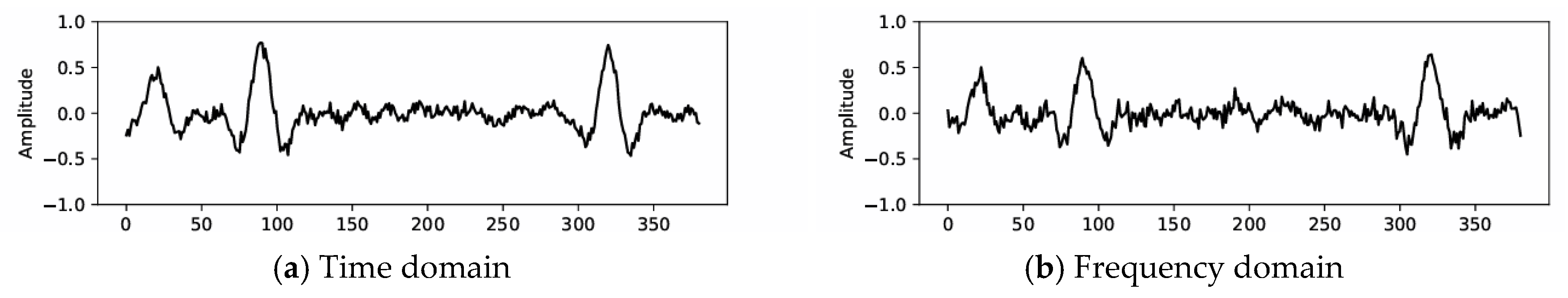

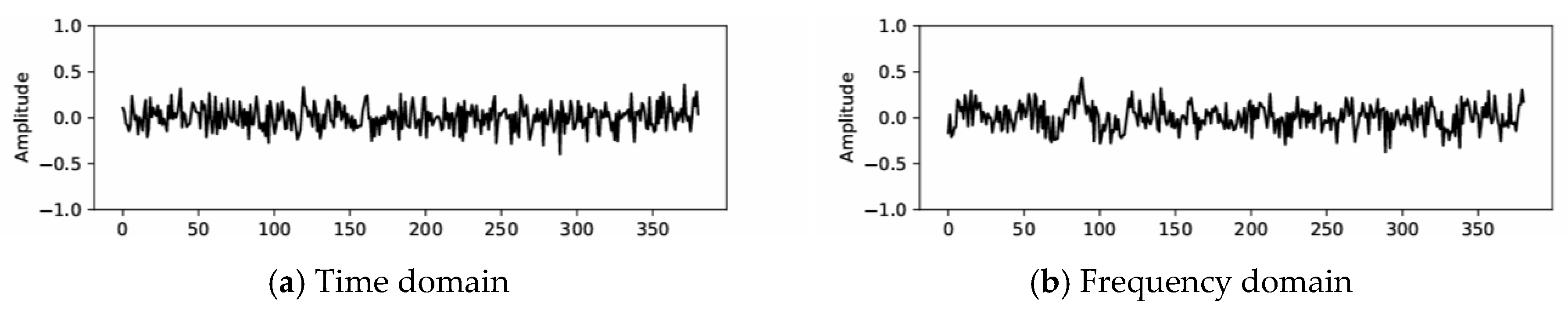

3.2. Synthetic Data

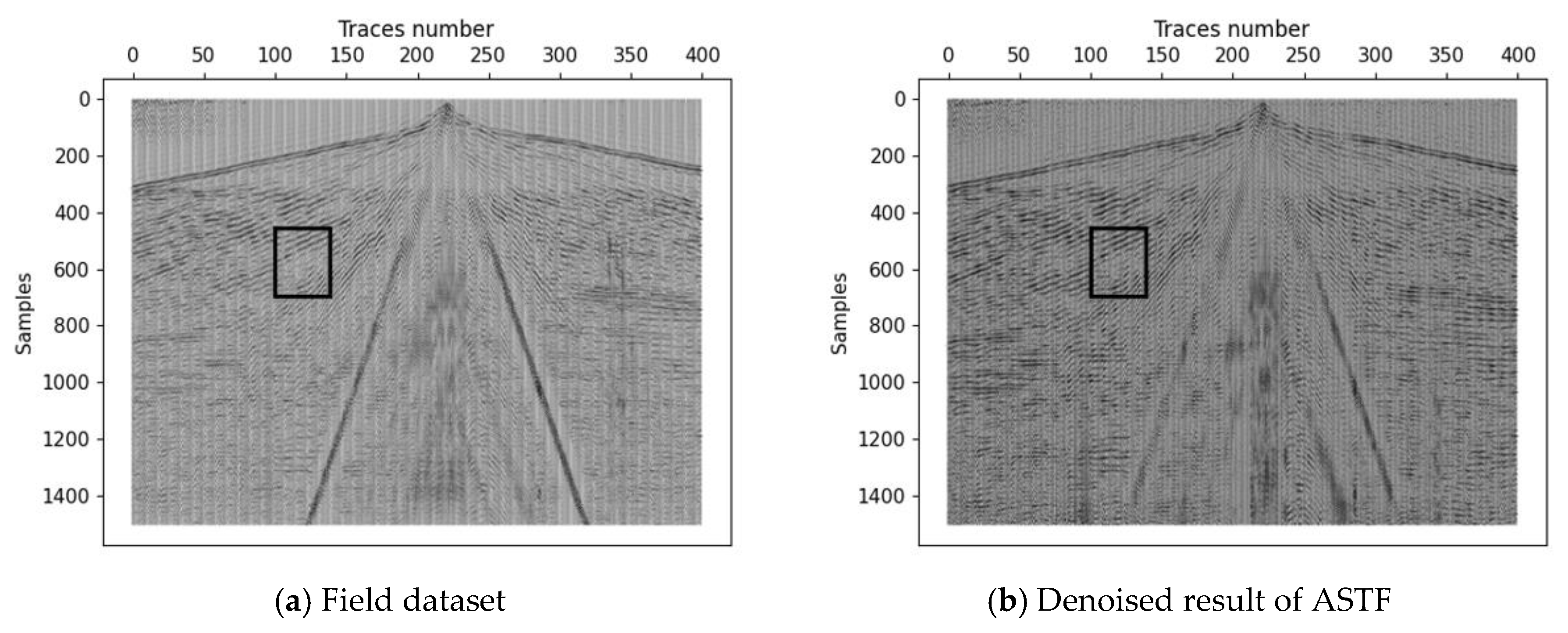

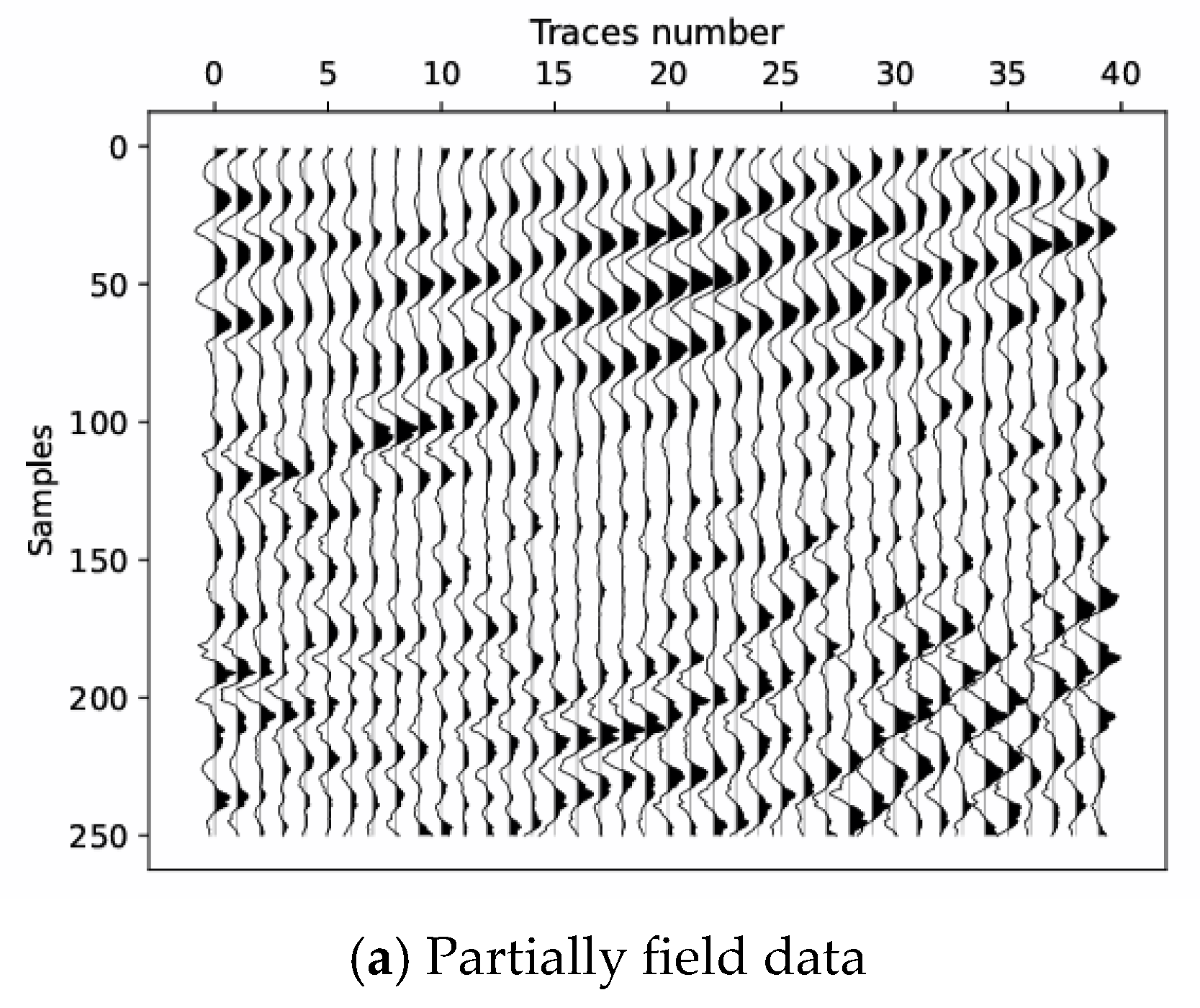

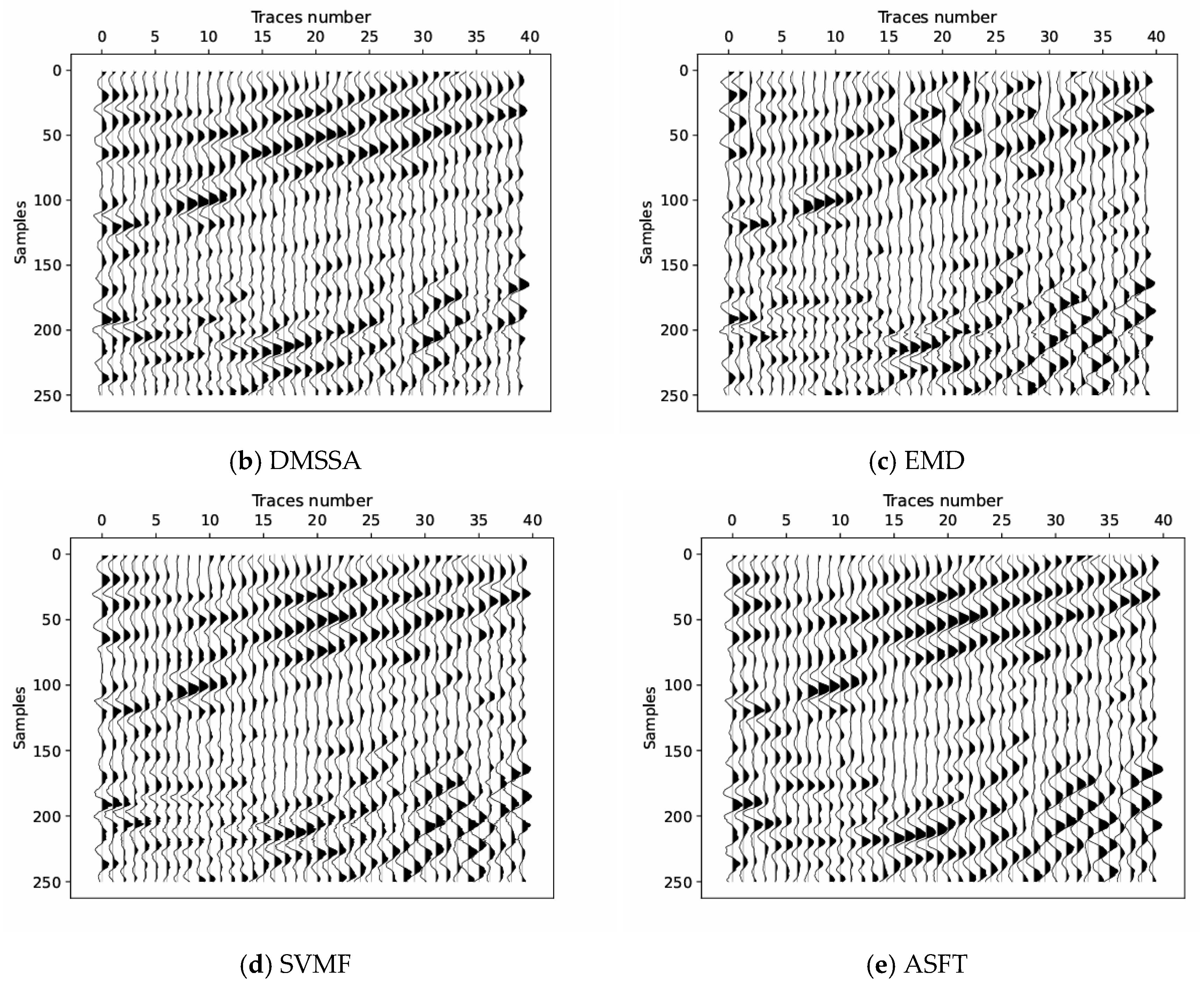

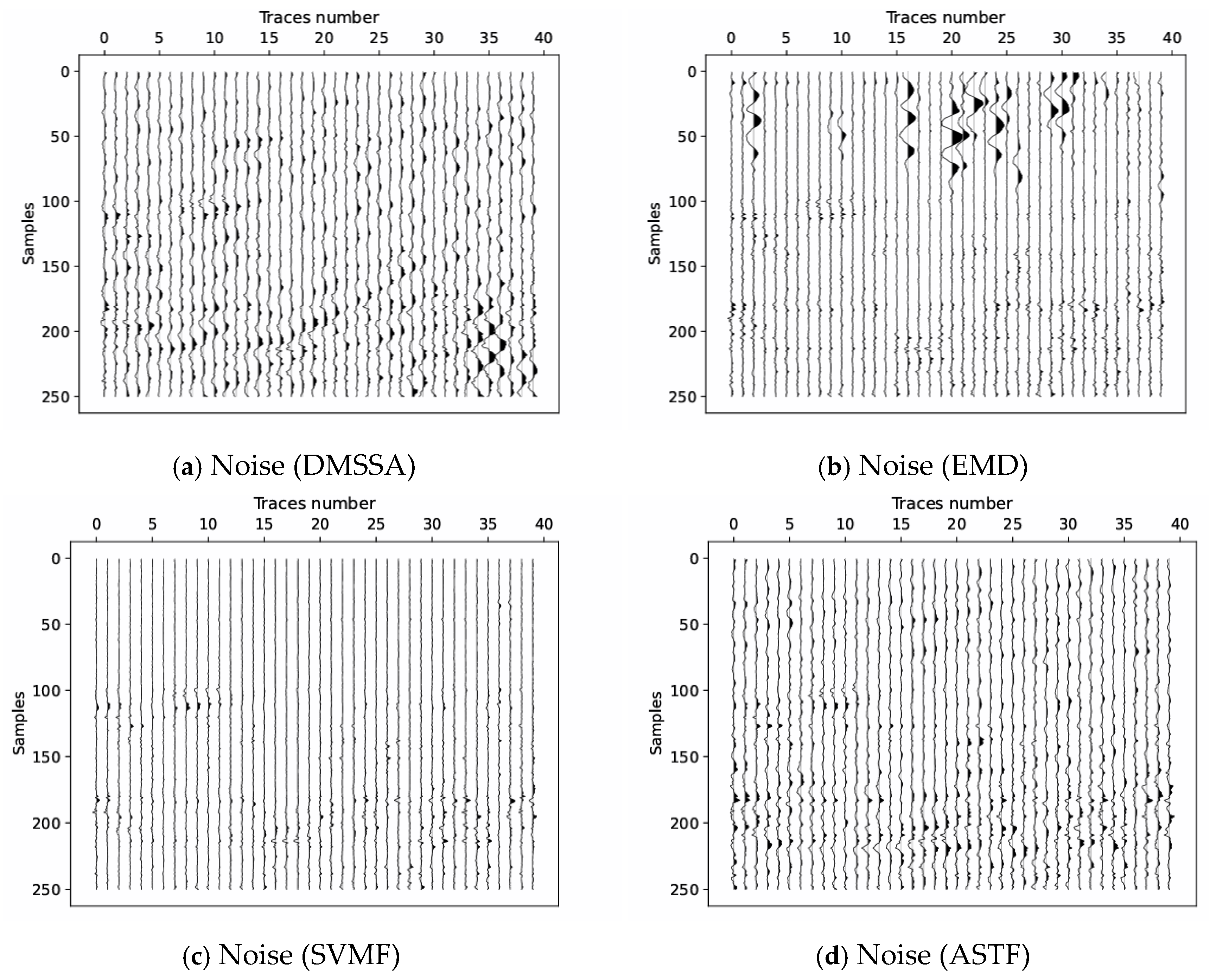

3.3. Field Data

4. Conclusions

References

- Wang H, Cao S, Jiang K, Wang H, Zhang Q. Seismic data denoising for complex structure using BM3D and local similarity. Journal of Applied Geophysics 2019, 170, 103759. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926985119300114.

- Chen, Wei. Random noise reduction using a hybrid method based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition. Journal of Seismic Exploration 2017 06;26:227–249.

- Feng Z. Seismic random noise attenuation using effective and efficient dictionary learning. Journal of Applied Geophysics 2021;186:104258. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926985121000057.

- Han J, van der Baan M. Empirical mode decomposition for seismic time-frequency analysis. Geophysics 2013 02;78(2):O9–O19. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Marfurt K. Instantaneous spectral attributes to detect channels. Geophysics 2007 03;72. [CrossRef]

- Shan H, Ma J, Yang H. Comparisons of wavelets, contourlets and curvelets in seismic denoising. Journal of Applied Geophysics 2009;69(2):103–115. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926985109001050.

- Anvari R, Nazari Siahsar MA, Gholtashee S, Roshandel Kahoo A, Mohammadi M. Seismic Random Noise Attenuation Us-ing Synchrosqueezed Wavelet Transform and Low-Rank Signal Matrix Approximation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017 11;55:6574–6581. [CrossRef]

- Morlet J. Wave propagation and sampling theory. Geophysics 1982 01;47:203–236. [CrossRef]

- Neelamani R, Baumstein AI, Gillard DG, Hadidi MT, Soroka WL. Coherent and random noise attenuation using the curvelet transform. The Leading Edge 2008 02;27(2):240–248. [CrossRef]

- Górszczyk A, Malinowski M, Bellefleur G. Enhancing 3D post-stack seismic data acquired in hardrock environment using 2D curvelet transform. Geophysical Prospecting 2015 03;63:903–918. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y. Dip-separated structural filtering using seislet transform and adaptive empirical mode decomposition based dip filter. Geophysical Journal International 2016;206(1):457–469. [CrossRef]

- Lv H. Noise suppression of microseismic data based on a fast singular value decomposition algorithm. Journal of Applied Geophysics 2019;170:103831. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926985119302587.

- Gerbrands JJ. On the relationships between SVD, KLT and PCA. Pattern Recognition 1981;14(1):375–381. https: //www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0031320381900820, 1980 Conference on Pattern Recognition.

- Golyandina N, Nekrutkin V, Zhigljavsky AA. Analysis of time series structure: SSA and related techniques. Chapman & Hall/CRC 2001;p. 28–29. [CrossRef]

- G T, S CSG. Tube wave suppression in high frequency mine seismic data by singular value decomposition. Exploration Geophysics 1995;26:512–517. [CrossRef]

- LP S, SY Z. Singular value decomposition-based reconstruction algorithm for seismic traveltime tomography. IEEE Trans Image Process 1999;8:1152–4. [CrossRef]

- Maïza B, der Baan Mirko V. Local singular value decomposition for signal enhancement of seismic data. Geophysics 2007 02;72(2):V59–V65. [CrossRef]

- Ma J, Wang J, Liu G. Seismic data noise attenuation and interpolation using singular value decomposition in frequency domain. Geophysical Prospecting for Petroleum 2016;55:205–213.

- Time-frequency denoising of microseismic data, vol. All Days of SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting; 2016, sEG-2016-13681108. [CrossRef]

- Zhao H, Li Y, Zhang C. SNR Enhancement for Downhole Microseismic Data Using CSST. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2016;13(8):1139–1143. [CrossRef]

- Liang X, Li Y, Zhang C. Noise suppression for microseismic data by non-subsampled shearlet transform based on singular value decomposition. Geophysical Prospecting 2018;66(5):894–903. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ 10.1111/1365-2478.12576.

- Hu Y, Huang J, Tian Z, Pan S. Ground microseismic data denoising based on single-channel singular value decompose- tion and amplitude ratio. Geophysical Prospecting for Petroleum 2019;58:47–56+66.

- Lari HH, Naghizadeh M, Sacchi MD, Gholami A. Adaptive singular spectrum analysis for seismic denoising and interpo-lation. GEOPHYSICS 2019;84(2):V133–V142. [CrossRef]

- Sabbione J, Velis D, Sacchi M. Microseismic data denoising via an apex-shifted hyperbolic Radon transform; 2013. p. 2155–2161.

- Chen Y, Zhang D, Jin Z, Chen X, Zu S, Huang W, et al. Simultaneous denoising and reconstruction of 5-D seismic data via damped rank-reduction method. Geophysical Journal International 2016;206(3):1695–1717. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Fomel S. EMD-seislet transform. GEOPHYSICS 2018;83(1):A27–A32. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Zu S, Wang Y, Chen X. Deblending of simultaneous source data using a structure-oriented space-varying me dian filter. Geophysical Journal International 2019 02;216:1214–1232. [CrossRef]

- Kalman, Dan. A singularly valuable decomposition: The SVD of a matrix. College Mathematics Journal 1996;27(1):2–23.

- Trickett S. F-xy Cadzow noise suppression. Seg Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 2008 01;27:2586–2590.s. [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Shots | Traces | Samples | Sampling interval | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dataset1 | 1 | 200 | 1501 | 2ms | Synthetic |

| dataset2 | 1 | 200 | 1501 | 2ms | Synthetic |

| dataset3 | 1 | 200 | 1501 | 2ms | Synthetic |

| dataset4 | 1 | 200 | 1501 | 2ms | Synthetic |

| field dataset | 500 | 400 | 1501 | 4ms | XinJiang |

| Dataset | Dataset1 | Dataset2 | Dataset3 | Dataset4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | SNR(dB) | PSNR(dB) | PSNR(dB) | PSNR(dB) | PSNR(dB) |

| 1 | 16.10 | 11.67 | 14.56 | 16.94 | |

| DMSSA | 3 | 18.78 | 12.76 | 16.62 | 20.80 |

| 5 | 19.87 | 13.18 | 17.35 | 22.65 | |

| 1 | 15.87 | 11.67 | 14.02 | 15.45 | |

| EMD | 3 | 19.50 | 12.77 | 16.20 | 19.41 |

| 5 | 21.29 | 13.11 | 17.27 | 21.58 | |

| 1 | 16.84 | 11.73 | 14.74 | 16.94 | |

| SMF | 3 | 20.77 | 12.71 | 16.80 | 21.25 |

| 5 | 22.66 | 13.09 | 17.53 | 23.11 | |

| 1 | 18.96 | 12.62 | 16.43 | 20.46 | |

| ASTF | 3 | 22.57 | 13.44 | 18.08 | 25.14 |

| 5 | 23.93 | 13.86 | 18.74 | 27.06 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).