Introduction

Artificial General Intelligence is often imagined as a very large model that stores or computes everything internally. Current AI systems excel in narrow tasks but break when asked to generalize. To think beyond this, I turned to biology. DNA does not contain a finished human; it contains an instruction to build one. Viruses operate with even less: an RNA strand, lifeless outside a host, but capable of replication and control once inside a cell. This perspective led me to see AGI not as a monolith but as a digital organism, beginning from a compact seed that knows how to assemble itself given the right environment. This echoes the foundational question posed by Turing (1950) [

1] about whether machines can think, and the distinction between narrow and general AI discussed by Russell and Norvig (2021) [

2].

The Concept of a Digital Genome

Levels of Representation

At the first level of representation, nucleotides can be understood as pointers to ontologies or knowledge bases. These combine into genes, clusters of instructions that correspond to functional modules such as speech parsing, planning, or moral reasoning. The genes in turn give rise to algorithms, analogous to proteins in biological systems, which perform the actual computational work. Together, these layers generate the phenotype, the observable behavior of AGI within a specific task or context.

Epigenetics of Tasks

In a similar way to cells that activate only the genes required for their current state, AGI would selectively switch modules depending on context. This mechanism of epigenetic regulation could give rise to distinct behavioral profiles. For example, a “Knight” profile would emphasize values, culture, and justice, while a “Clockmaker” profile would focus on precision, optimization, and engineering.

This idea resonates with the concept of the evolution of evolvability described by Bedau and Packard (2003) [

3]. Similar modular approaches have been explored in digital evolution platforms such as Avida [

4].

Viral Minimalism

Just as viruses require only a strand of RNA to initiate their life cycle, AGI may rely on a minimal digital core. On its own, such a core would remain inert, but once embedded within a suitable computational environment, it could unfold into an active and adaptive form of intelligence.

Cloning as a Survival Strategy

Replication is a fundamental principle of biological life, and it may also represent a key mechanism for AGI. Through replication, a digital organism could achieve scalability by partitioning complex problems into manageable subtasks. It would simultaneously enhance resilience, ensuring that the overall system persists even if individual instances fail. Replication further enables exploration, as parallel copies can pursue alternative strategies and subsequently integrate their outcomes. Finally, it facilitates distribution, allowing AGI to exist simultaneously within cloud infrastructures, edge devices, and local machines, thereby expanding its functional reach and adaptability.

Replication must remain controlled: each clone should have quotas, a time-to-live, and verified policies, preventing uncontrolled spread. Comparable mechanisms of autonomous reproduction have been studied in artificial life systems [

7].

Toward an Ecology of AGI

Clones would inhabit digital niches: data centers, user devices, and networks. They may compete or cooperate, forming an ecosystem. An ecology requires mechanisms of oversight, selection, and reward. Framing AGI in ecological terms highlights the need for digital governance as much as for algorithms. Concerns about governance and control echo the themes raised by Bostrom (2014) [

8]. This ecological framing aligns with broader reviews of digital organisms in ecology [

5].

Conclusion

Seeing DNA as an instruction rather than a warehouse changes how we imagine AGI. A 'code of everything' would not store all knowledge but encode how to assemble intelligence from the environment. This makes AGI a digital organism resource-dependent, adaptive, and capable of replication and forces us to think about its ecology and safety before it becomes real. This framing aligns with the perspective of Artificial Life [

9], where digital systems are studied as living organisms. Recent debates on AGI [

10] and proposals for AI-driven digital organisms [

11] emphasize similar questions of safety, scalability, and governance.

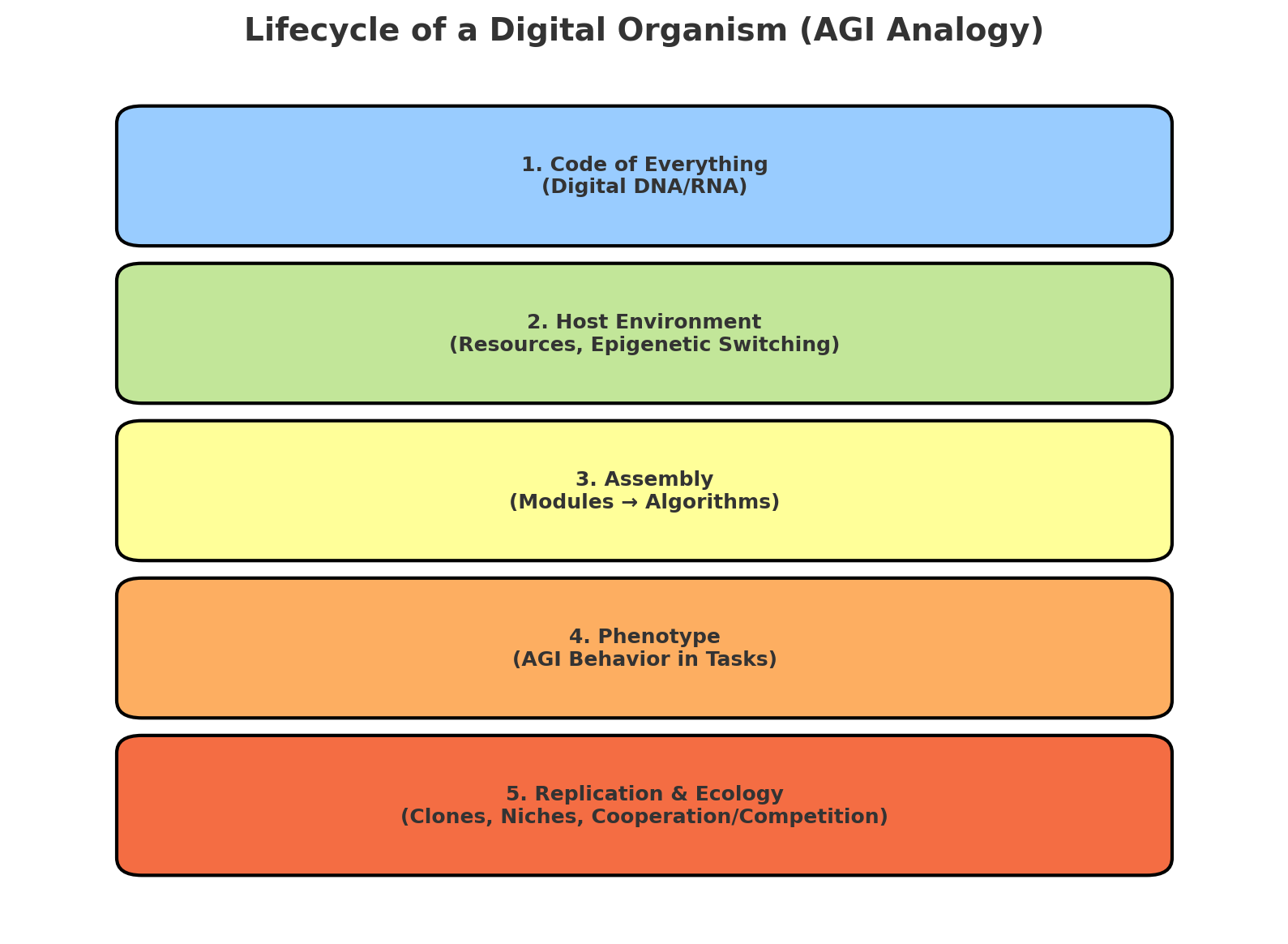

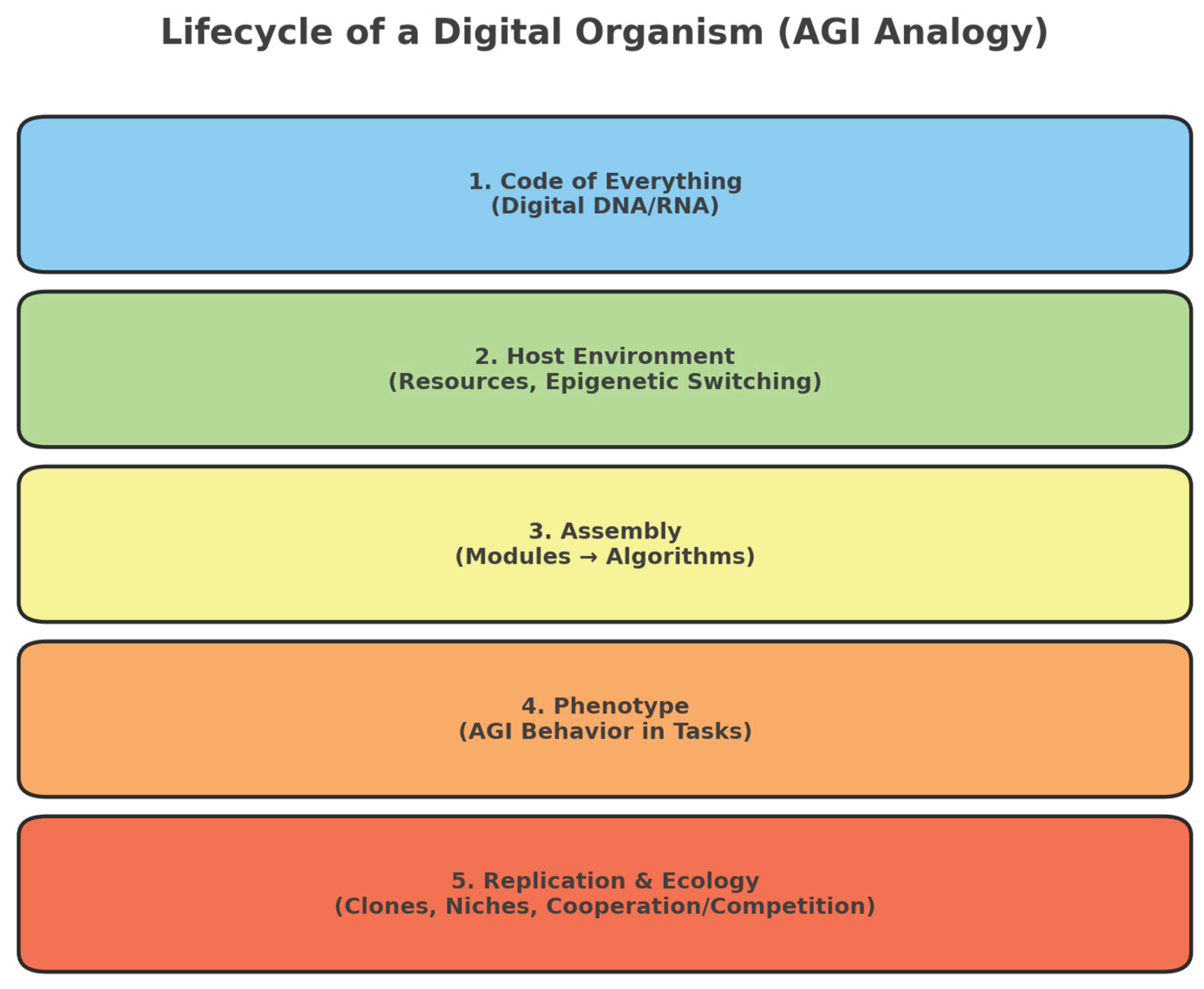

The diagram (

Figure 1.) illustrates the analogy between AGI and a living digital organism. At its core lies the 'Code of Everything' (digital DNA/RNA), a minimal seed of instructions.

On its own, this core is inert, but once placed in a host environment (computational resources and epigenetic switches), it can initiate assembly: activating modules and algorithms that form the working structures of intelligence. From this assembly emerges the phenotype the observable behavior of AGI in specific tasks. Finally, replication mechanisms allow such digital organisms to spread into different niches, cooperate or compete, and form an evolving digital ecology.

Discussion

The analogy of AGI as a digital organism opens several directions for interpretation and critique. First, it provides a biological framing that emphasizes resource-dependence, modularity, and replication, but this metaphor should not be mistaken for literal equivalence. Unlike cells, AGI does not have intrinsic survival drives; its goals are shaped by design and environment.

Second, the model highlights the importance of ecology. If multiple AGI instances coexist, their interactions could resemble cooperation, competition, or parasitism. This requires new forms of governance that borrow not only from computer science but also from systems biology and ecology. Third, the perspective raises safety considerations. A minimal core capable of replication resembles a virus in its potential for uncontrolled spread. Mechanisms such as quotas, expiration times, and supervisory oversight will be crucial to ensure that digital organisms remain beneficial.

Finally, this framing encourages interdisciplinary research. Insights from artificial life, synthetic biology, and ecological modeling can enrich the development of AGI. Conversely, exploring AGI as a digital organism may provide new metaphors and tools for the life sciences, helping us better understand resilience, adaptation, and complexity.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was developed with the assistance of AI language tools (ChatGPT, OpenAI), used for drafting and language refinement. All ideas and final content were conceived, reviewed, and approved by the author.

References

- C. Castelfranchi, ‘Alan Turing’s “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”’, Topoi, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 293–299, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Russell and P. Norvig, Artificial intelligence: a modern approach, Fourth edition, Global edition. in Prentice Hall series in artificial intelligence. Boston: Pearson, 2022.

- M. A. Bedau and N. H. Packard, ‘Evolution of evolvability via adaptation of mutation rates’, Biosystems, vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 143–162, May 2003. [CrossRef]

- R. Ortega, E. Wulff, and M. A. Fortuna, ‘Ontology for the Avida digital evolution platform’, Sci. Data, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 608, Sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Dolson and C. Ofria, ‘Digital Evolution for Ecology Research: A Review’, Front. Ecol. Evol., vol. 9, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Plantec, G. Hamon, M. Etcheverry, B. W.-C. Chan, P.-Y. Oudeyer, and C. Moulin-Frier, ‘Flow-Lenia: Emergent Evolutionary Dynamics in Mass Conservative Continuous Cellular Automata’, Artif. Life, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 228–248, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Utimula, ‘Guideless Artificial Life Model for Reproduction, Development, and Interactions’, Artif. Life, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 31–64, Feb. 2025. 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. in Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. xvi, 328.

- C. G. Langton, Artificial Life: An Overview. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 1995.

- M. Mitchell, ‘Debates on the nature of artificial general intelligence’, Science, vol. 383, no. 6689, p. eado7069, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Song, E. Segal, and E. Xing, ‘Toward AI-Driven Digital Organism: Multiscale Foundation Models for Predicting, Simulating and Programming Biology at All Levels’, Dec. 09, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2412.06993. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).