Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate the chlorine-related challenges in Automotive Shredder Residue (ASR) by developing a de-chlorination strategy and formulating Solid Recovered Fuel (SRF) pellets with improved environmental and fuel quality. A ternary blending approach was employed using Fe–Ca-based inorganic dechlorinating agents and thorny bamboo biomass as co-materials with ASR. The de-chlorination efficiency, calorific value, and ash content of the resulting SRF were evaluated. Results indicated that the optimal dechlorinating formulation reduced the chlorine content of PVC from 43.26 wt% to 0.59 wt%, achieving a de-chlorination efficiency of 97.23%. A second-order polynomial regression model(η_DeCl = –1.5277x² + 2.5519x – 0.0225,R² = 0.9347)was developed to predict the de-chlorination performance based on the blending ratio of dechlorinating agent to ASR, demonstrating behavior consistent with first-order reaction kinetics observed in pyrolytic de-chlorination. The final ternary formulation—comprising 55% thorny bamboo, 37.5% ASR, and 7.5% dechlorinating agent—produced SRF pellets with improved overall quality, demonstrating effective chlorine control, reasonable ash content, and enhanced thermal properties suitable for regulatory compliance and practical application. Such findings meet the criteria set by EN ISO 21640:2021 (Class 2), JIS Z7311 (Grade A), and forthcoming Taiwanese SRF regulations. Based on the findings in this work it can be stated that the high de-chlorination potential of Fe–Ca-based additives for chlorine-rich waste and introduces a predictive formulation model that supports both resource circularity and clean fuel production.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Analytical Methods

3. Results

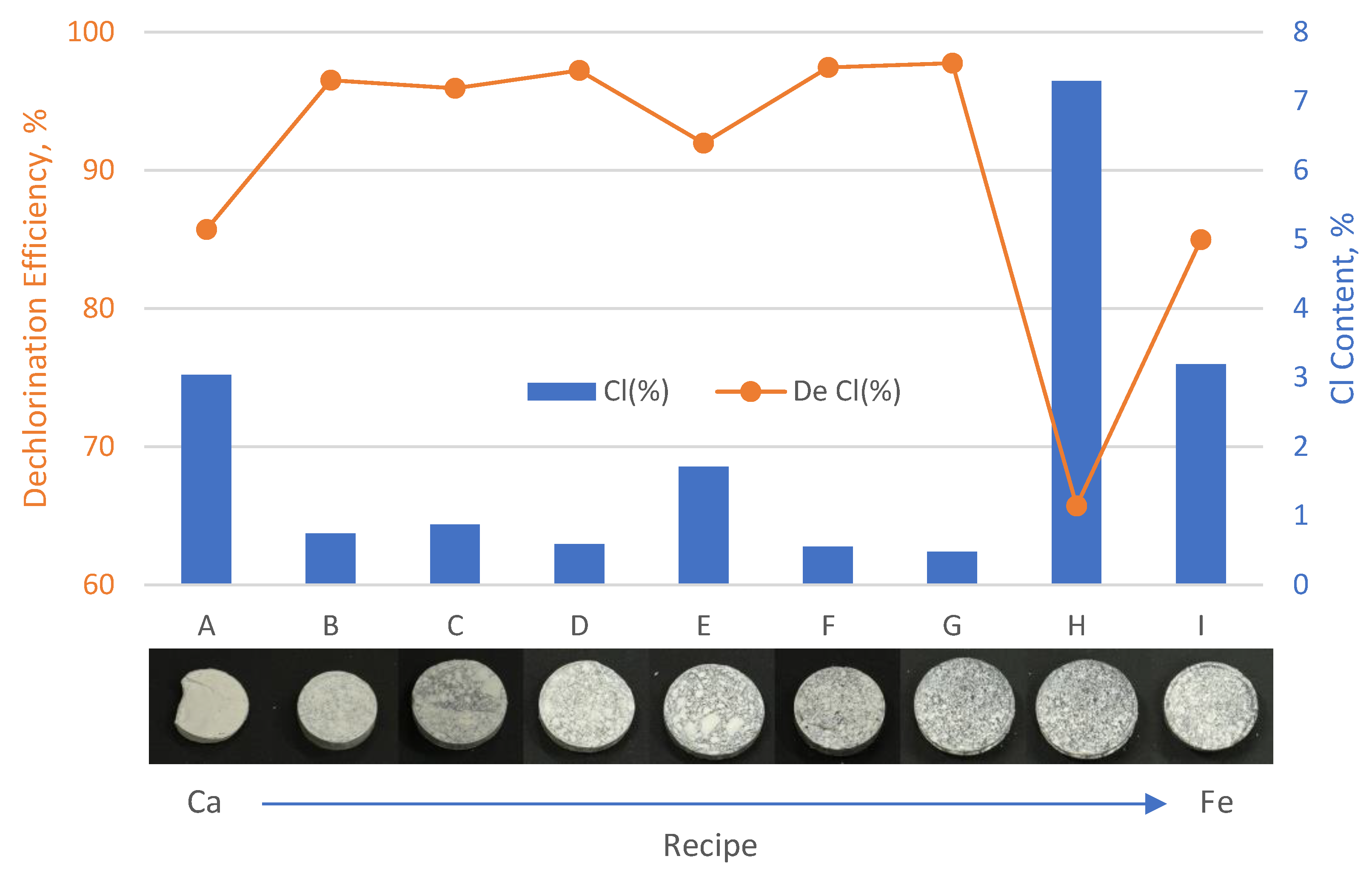

3.1. Dechlorination Efficiency of Dechlorinating Agent Formulations (A–I) on PVC

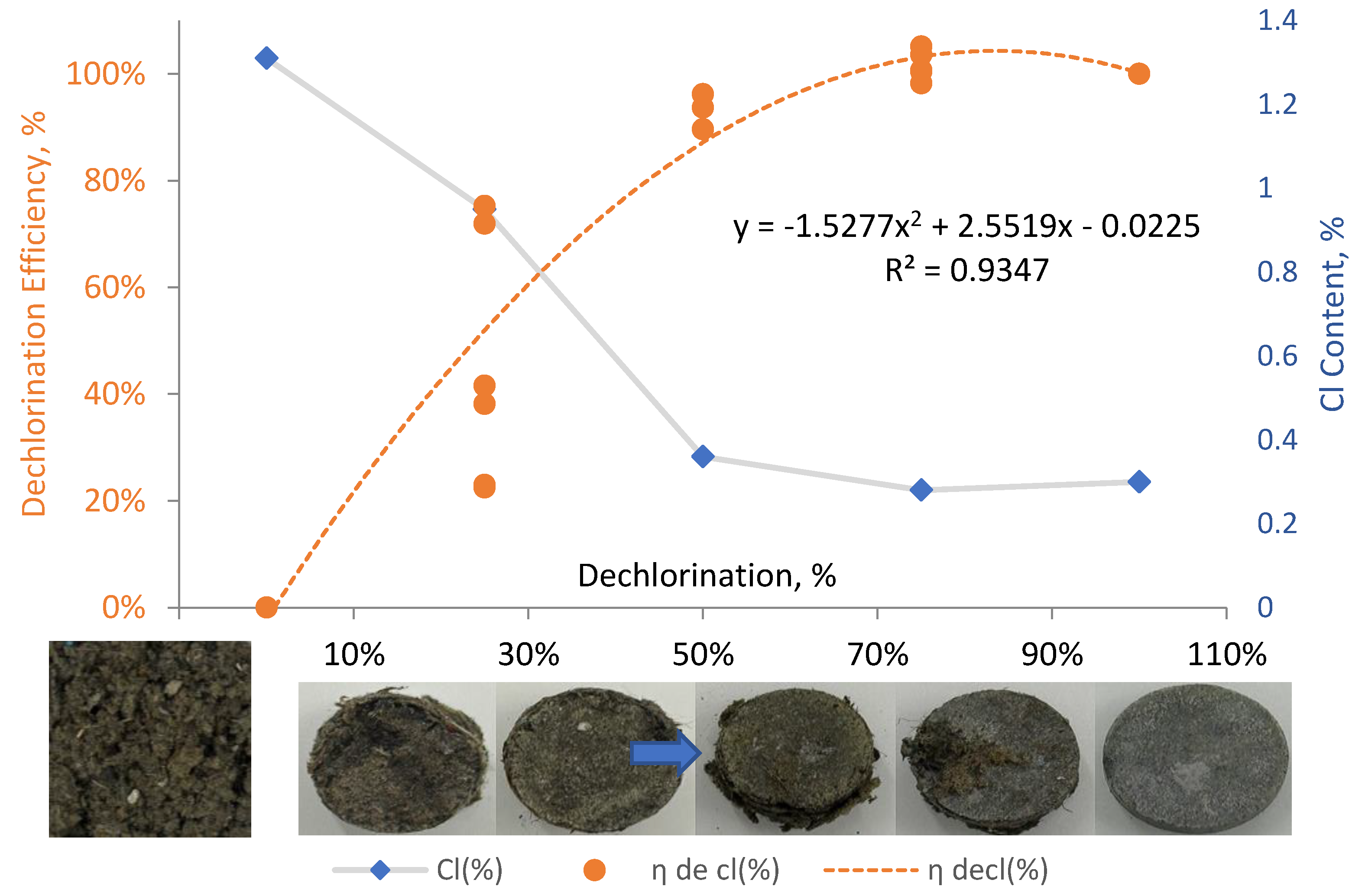

3.2. Effect of ASR and Dechlorination Agent Mixing Ratio on Chlorine Content Control

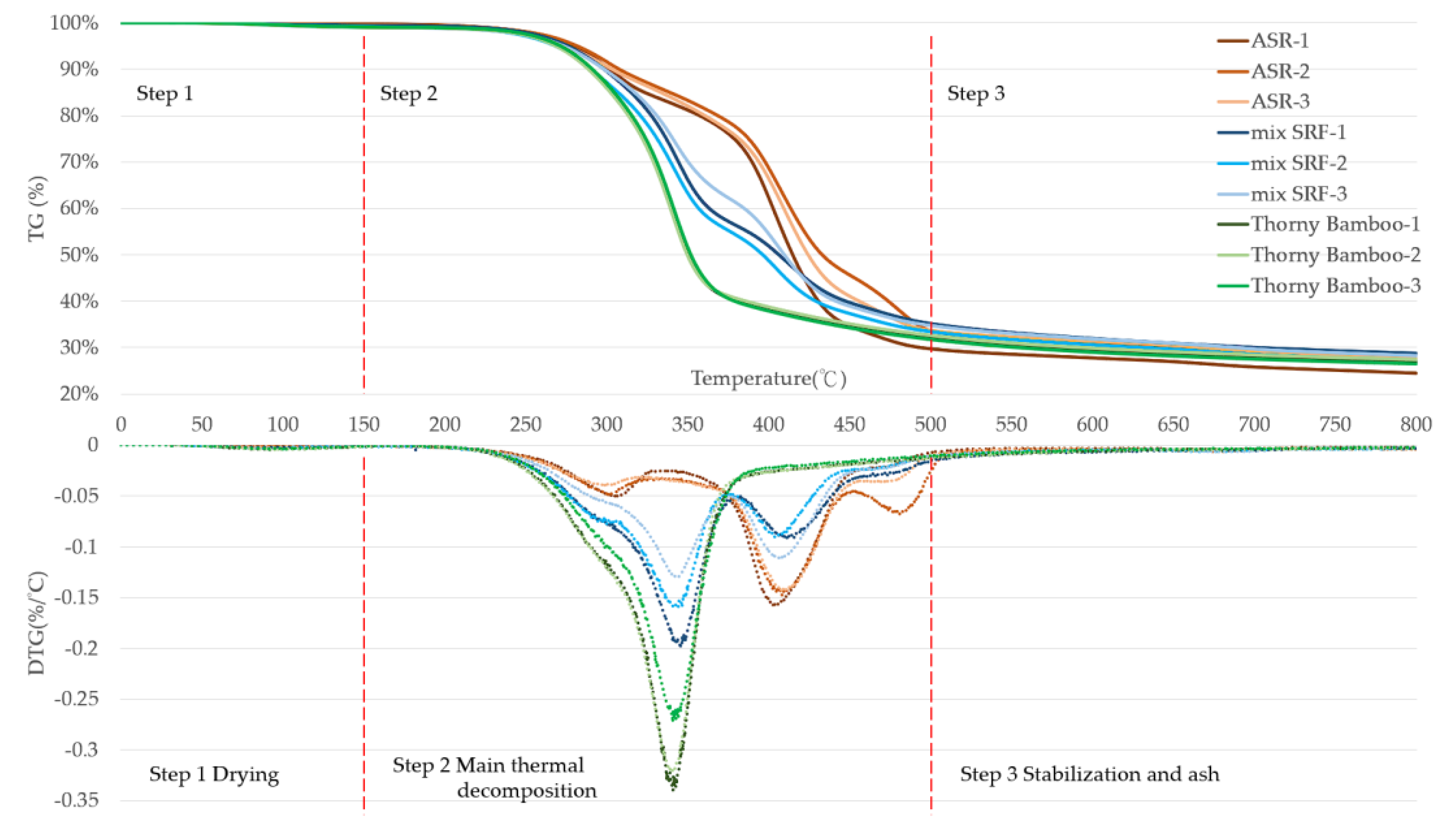

3.3. Properties of SRF Pellets Made from Thorny Bamboo / ASR / Dechlorinating Agent Ternary Mixtures

- Step 1 (<150 °C): evaporation of moisture and light volatiles.

- Step 2 (200–400 °C): pyrolysis of major combustible components (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose, plastic matrix); the DTG curve of mix SRF closely resembled that of thorny bamboo, showing a concentrated decomposition peak, indicating good thermal stability and consistent reaction behavior.

- Step 3 (>500 °C): corresponds to residual carbonization and inorganic compounds, forming ash.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of Fe–Ca-Based Dechlorinating Agents

- a.

- Excessive Fe leading to by-product formation: Under high-temperature pyrolysis or carbonization conditions, excess iron may react with chlorine to form stable iron chlorides (e.g., FeCl₃), which can reduce the conversion efficiency of intermediate compounds and thus inhibit the overall dechlorination reaction process [26].

- b.

- Lack of alkaline neutralization effect: Compared to calcium, which provides alkalinity to neutralize acidic gases and stabilize residues [33] , iron is chemically neutral or mildly acidic. When the Fe proportion is too high and Ca too low, the absence of sufficient alkaline buffering may result in ineffective suppression of HCl gas, thereby lowering chlorine volatilization and reducing overall dechlorination efficiency.

4.2. Applicability of the Chlorine Content Prediction Model

4.3. Technical Feasibility and Regulatory Compliance of Final Pellet Formulation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gerassimidou, S.; et al. Chlorine in waste-derived solid recovered fuel (SRF), co-combusted in cement kilns: A systematic review of sources, reactions, fate and implications. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2021, 51, 140–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokeš, R. , et al. Thermomechanical Treatment of SRF for Enhanced Fuel Properties. Fire 2025, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.T., C. H. Tsai, and C.C. Pan, Outlook of Solid Recovered Fuel (SRF) for the Substitution of Fossil Fuels in the Industrial Utilities, in Preprints. 2024, Preprints.

- Santini, A.; et al. Auto shredder residue recycling: Mechanical separation and pyrolysis. Waste Management 2012, 32, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, S.A.; et al. Pyrolysis and gasification-melting of automobile shredder residue. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2013, 63, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, I.; et al. Automotive shredder residue (ASR): Reviewing its production from end-of-life vehicles (ELVs) and its recycling, energy or chemicals’ valorisation. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2011, 190, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; et al. Enhancing pyrolysis of automobile shredder residue through torrefaction: Interactions among typical components. Fuel 2025, 390, 134670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, T., A. Kitajima, and M. Takeuchi, Role of Chlorine in Combustion Field in Formation of Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-dioxins and Dibenzofurans during Waste Incineration. Environmental Science & Technology, 9456. [Google Scholar]

- Acha, E.; et al. Combustion of a Solid Recovered Fuel (SRF) Produced from the Polymeric Fraction of Automotive Shredder Residue (ASR). Polymers 2021, 13, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C., H. -C. Lin, and L.-Y. Chen, Solid fuel recovered from food waste dechlorination: Proof of concept and cost analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 360, 132240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; et al. Effect of granulation on chlorine-release behavior during municipal solid waste incineration. RSC Advances 2023, 13, 24854–24864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; et al. Mitigating heavy metal volatilization during thermal treatment of MSWI fly ash by using iron(III) sulfate as a chlorine depleting agent. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 465, 133185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, S.K., M. A. Kibria, and S. Bhattacharya, A Study on Pyrolysis of Pretreated Automotive Shredder Residue—Thermochemical Calculations and Experimental Work. Frontiers in Sustainability, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Harder, M.K. and O.T. Forton, A critical review of developments in the pyrolysis of automotive shredder residue. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2007, 79, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, M.A., J. A. Conesa, and M.D. Garcia, Characterization and Production of Fuel Briquettes Made from Biomass and Plastic Wastes. Energies.

- Gopan, G., R. Krishnan, and M. Arun, Review of bamboo biomass as a sustainable energy. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies, 2733. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch, F.; et al. Energy properties of bamboo biomass and mate co-products. SN Applied Sciences 2021, 3, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku Aizuddin, K.N.A.; et al. Bamboo for Biomass Energy Production. BioResources 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgharbawy, A. , Poly Vinyl Chloride Additives and Applications-A Review. Journal of Risk Analysis and Crisis Response 2022, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; et al. Thermal degradation of PVC: A review. Waste Management 2016, 48, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awogbemi, O. and D.A. Desai, Harnessing the potentials of bamboo as a sustainable feedstock for bioenergy production. Advances in Bamboo Science 2025, 12, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; et al. Progress in biomass torrefaction: Principles, applications and challenges. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2021, 82, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodier, A., K. Williams, and N. Dallison, Challenges around automotive shredder residue production and disposal. Waste Management.

- Szydełko, A., W. Ferens, and W. Rybak, The effect of mineral additives on the process of chlorine bonding during combustion and co-combustion of Solid Recovered Fuels. Waste Management.

- Lin, X.; et al. Influence of Different Catalytic Metals on the Formation of PCDD/Fs during Co-combustion of Sewage Sludge and Coal. Aerosol and Air Quality Research 2022, 22, 220268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L., T. -l. Li, and L.-h. Ye, De-chlorination of poly(vinyl) chloride using Fe2O3 and the improvement of chlorine fixing ratio in FeCl2 by SiO2 addition. High Temperature Materials and Processes 2024, 43, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.M. , et al. Brief Overview of Refuse-Derived Fuel Production and Energetic Valorization: Applied Technology and Main Challenges. Sustainability, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-Q., C. -H. Tsai, and W.-T. Tsai Progress in Solid Recovered Fuel with an Emphasis on Lignocellulose-Based Biomass—A Mini Review Focused on Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Energies, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Comparative properties of bamboo and pine pellets. Wood and fiber science: journal of the Society of Wood Science and Technology.

- Kathiravale, S.; et al. Modeling the heating value of Municipal Solid Waste☆. Fuel 2003, 82, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, U. and F. Di Gregorio, Element partitioning in combustion- and gasification-based waste-to-energy units. Waste Management 2013, 33, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashtestani, F.; et al. Effect of the Presence of HCl on Simultaneous CO2 Capture and Contaminants Removal from Simulated Biomass Gasification Producer Gas by CaO-Fe2O3 Sorbent in Calcium Looping Cycles. Energies 2021, 14, 8167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemwell, B., Y. A. Levendis, and G.A. Simons, Laboratory study on the high-temperature capture of HCl gas by dry-injection of calcium-based sorbents. Chemosphere.

- Fekhar, B., L. Gombor, and N. Miskolczi, Pyrolysis of chlorine contaminated municipal plastic waste: In-situ upgrading of pyrolysis oils by Ni/ZSM-5, Ni/SAPO-11, red mud and Ca(OH)2 containing catalysts. Journal of the Energy Institute, 1270. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.C. and Y.C. Tsai, Dry dechlorination of solid-derived fuels obtained from food waste and polyvinyl chloride. Sci Total Environ 2022, 841, 156745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; et al. Catalytic degradation and dechlorination of PVC-containing mixed plastics via Al–Mg composite oxide catalysts. Fuel 2004, 83, 1727–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingaiah, N.; et al. Catalytic dechlorination of chloroorganic compounds from PVC-containing mixed plastic-derived oil. Applied Catalysis A: General.

- Babyak, M.A. , What you see may not be what you get: a brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosom Med 2004, 66, 411–21. [Google Scholar]

- Royston, P. and W. Sauerbrei, Improving the robustness of fractional polynomial models by preliminary covariate transformation: A pragmatic approach. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 4253. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; et al. Effect of granulation on chlorine-release behavior during municipal solid waste incineration. RSC Adv 2023, 13, 24854–24864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R., R. Ray, and C. Chapman, Advanced thermal treatment of auto shredder residue and refuse derived fuel. Fuel.

| Recipe number | PVC content (wt%) |

Chlorine reducing agent type Ca : Fe ratio |

Chlorine reducing agent content (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 50 | Ca-Fe powder 100:0 |

50 |

| B | 50 | Ca-Fe powder 87.5:12.5 |

50 |

| C | 50 | Ca-Fe powder 75:25 |

50 |

| D | 50 | Ca-Fe powder 62.5:37.5 |

50 |

| E | 50 | Ca-Fe powder 50:50 |

50 |

| F | 50 | Ca-Fe powder 37.5:62.5 |

50 |

| G | 50 | Ca-Fe powder 25:75 |

50 |

| H | 50 | Ca-Fe powder 12.5:87.5 |

50 |

| I | 50 | Ca-Fe powder 0:100 |

50 |

| NUMBER | ASR content (wt%) | Chlorine reducing agent content (wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| De-cl(D)-0% | 100 | 0 |

| De-cl(D)-25% | 75 | 25 |

| De-cl(D)-50% | 50 | 50 |

| De-cl(D)-75% | 25 | 75 |

| De-cl(D)-100% | 0 | 100 |

| Country / Standard | Classification / Grade | NCV Requirement (MJ/kg) | Chlorine Limit (%) |

Ash Limit (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISO 21640:2021 (EN) | Class 1 | ≥ 25 | ≤ 0.2 | — |

| Class 2 | ≥ 20 | ≤ 0.6 | — | |

| Class 3 | ≥ 15 | ≤ 1.5 | — | |

| Class 4 | ≥ 10 | ≤ 2.0 | — | |

| Class 5 | ≥ 3 | ≤ 3.0 | — | |

| Japan JIS Z 7311:2010(RPF) | Grade A | ≥ 33 | ≤ 0.6 | ≤ 5 |

| Grade B | ≥ 25 | ≤ 0.3 | ≤ 10 | |

| Grade C | ≥ 25 | ≤ 2.0 | ≤ 10 | |

|

South Korea (K-SRF,Bio-SRF) |

K-SRF | ≥ 14.65 | ≤ 2.0 | ≤ 20 |

| Bio-SRF | ≥ 12.56 | ≤ 0.5 | ≤ 15 | |

|

Taiwan (current guideline, 2020) |

— | ≥ 10 | ≤ 3.0 | — |

|

Taiwan (proposed 2025 guidelines) |

— | — | ≤ 1.5 | — |

| Type | N | Cl(%) | ASH(%) | η De Cl(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONTROL | 6 | 42.53 | - | - |

| A | 6 | 3.04 ± 1.50 a, b | 32.98 ± 19.28 a | 85.72 |

| B | 6 | 0.74 ± 0.41 b | 24.92 ± 8.28 a | 96.52 |

| C | 6 | 0.87 ± 0.23 b | 28.39 ± 6.11 a | 95.93 |

| D | 6 | 0.59 ± 0.17 b | 30.31 ± 6.13 a | 97.23 |

| E | 6 | 1.71 ± 1.42 b | 31.96 ± 9.01 a | 91.95 |

| F | 6 | 0.55 ± 0.22 b | 41.05 ± 6.80 a | 97.44 |

| G | 6 | 0.48 ± 0.26 b | 37.34 ± 6.08 a | 97.75 |

| H | 6 | 7.29 ± 7.11 a | 42.96 ± 2.09 a | 65.72 |

| I | 6 | 3.19 ± 2.96 a, b | 42.57 ± 10.55 a | 84.99 |

| Recipe number | N | Cl(%) | ASH(%) | ηDe Cl(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De-cl(D)0% | 6 | 1.31 ± 0.61 a | 7.21 ± 0.63 a | - |

| De-cl(D)25% | 6 | 0.95 ± 0.41 a | 2.56 ± 0.80 b | 35.64 |

| De-cl(D)50% | 6 | 0.36 ± 0.02 b | 1.93 ± 0.10 b, c | 94.06 |

| De-cl(D)75% | 6 | 0.28 ± 0.03 b | 1.53 ± 0.01 c | 101.98 |

| De-cl(D)100% | 6 | 0.30 ± 0.08 b | 1.27 ± 0.07 c | 100.00 |

| Project | N | ASH(%) | NCV(MJ/kg) | Cl(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASR | 3 | 18.41 ± 2.59 a | 14.66 ± 1.67 b | 1.31 ± 0.61 a |

| Thorny Bamboo | 3 | 4.58 ± 0.07 c | 20.63 ± 0.05 a | 0.0015 [29] b |

| mix SRF | 3 | 14.44 ± 0.74 b | 19.38 ± 0.14 a | 0.31 ± 0.04 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).