Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

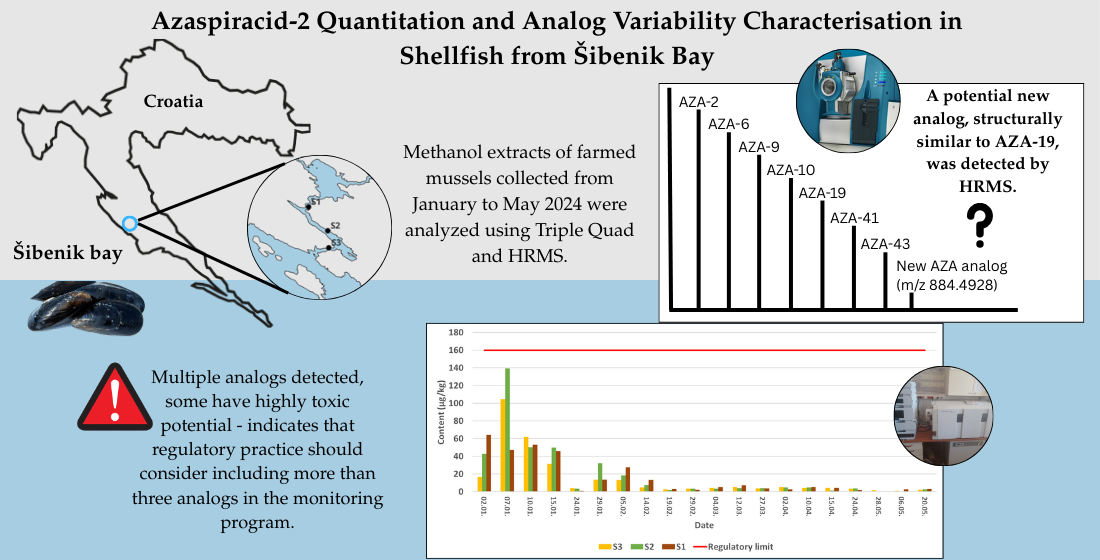

1. Introduction

2. Results

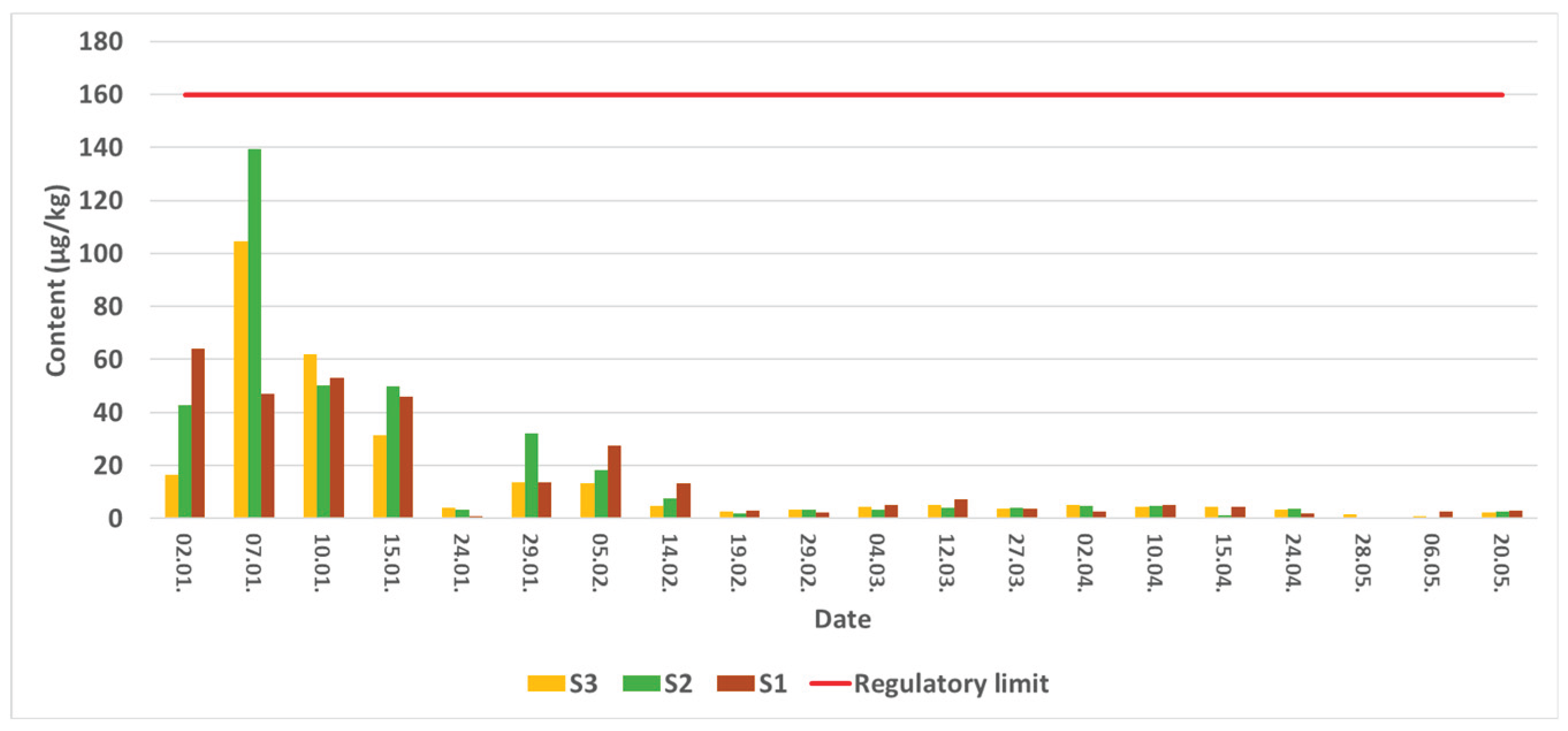

2.1. Quantitative Determination of the AZA 2 Content

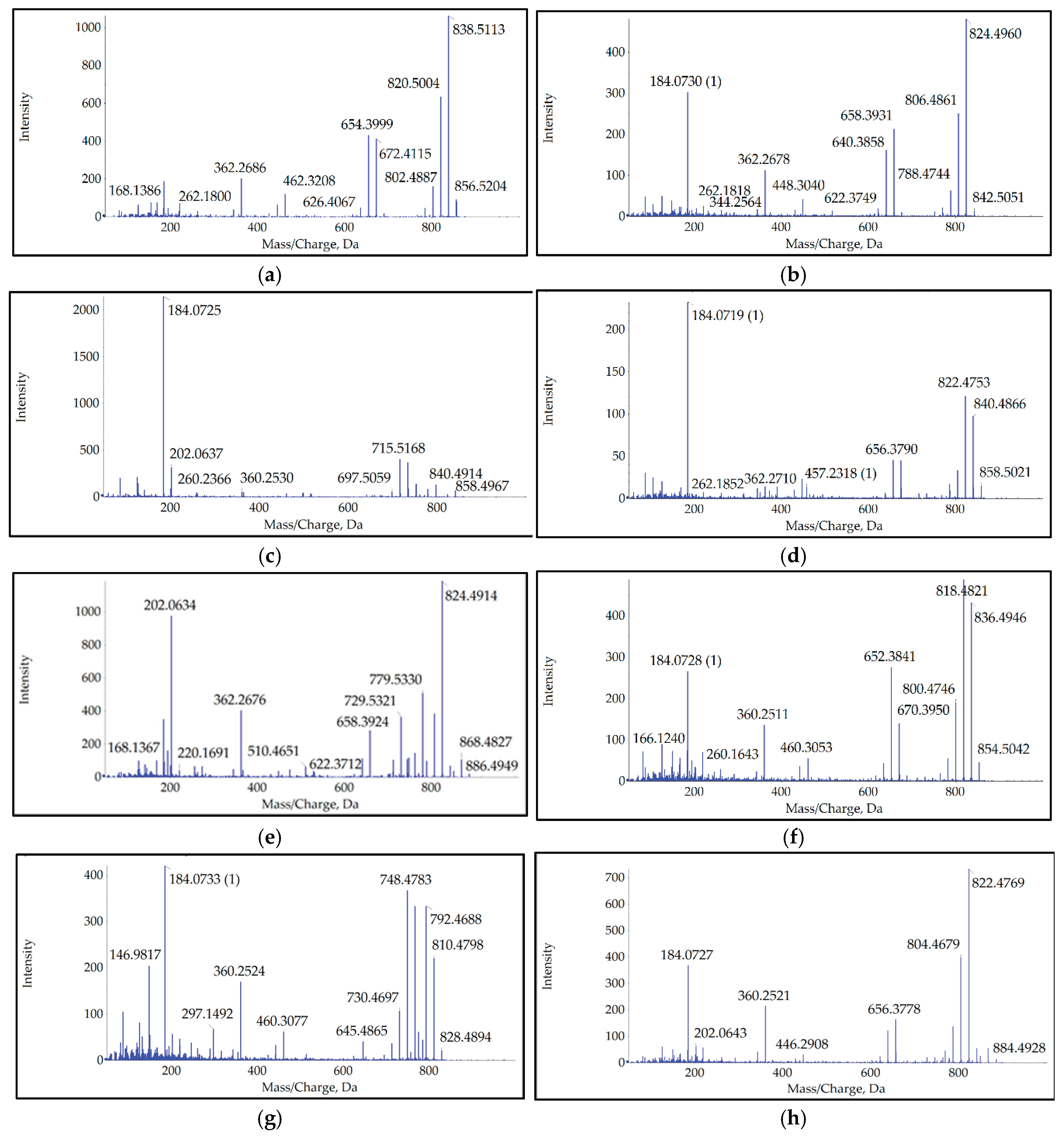

2.2. Variability of Azaspiracids at Sampling Sites – Toxin Profiles

2.3. Temporal Dynamics of an Analog Occurrence

| Date and station | AZA-2 XIC area | Analog XIC area relative to AZA-2 (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZA-2 | AZA-6 | AZA-9 | AZA-10 | AZA-19 | AZA-41 | AZA-43 | 884,5 | |

| 02.01.2024. S1 | 1,30E+05 | 56,50 | 27,4 | 18,1 | 73,5 | 41,6 | 52,7 | 26,0 |

| 02.01.2024. S2 | 3,86E+05 | 29,20 | 13,7 | 8,9 | 32,8 | 60,8 | 51,5 | 11,1 |

| 02.01.2024. S3 | 4,30E+05 | 36,50 | 17,7 | 10,8 | 35,2 | 3,2 | 52,6 | 15,8 |

| 07.01.2024. S1 | 3,51E+05 | 19,90 | 12,5 | 7,9 | 25,2 | 65,1 | 50,5 | 6,0 |

| 07.01.2024. S2 | 6,04E+05 | 15,50 | 9,2 | 6,4 | 24,3 | 62,5 | 46,7 | 7,9 |

| 07.01.2024. S3 | 1,68E+05 | 28,40 | 13,7 | 10,1 | 42,6 | 60,4 | 48,6 | 9,5 |

| 10.01.2024. S1 | 2,26E+05 | 22,00 | 27,6 | 10,6 | 42,4 | 55,8 | 48,1 | 13,4 |

| 10.01.2024. S2 | 1,55E+05 | 15,30 | 17,5 | 7,6 | 52,8 | 77,2 | 69,9 | 22,6 |

| 10.01.2024. S3 | 1,46E+05 | 18,80 | 22,3 | 8,7 | 52,2 | 75,5 | 61,1 | 21,1 |

| 24.01.2024. S1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 24.01.2024. S2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 24.01.2024. S3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 29.01.2024. S1 | 6336,45 | 130,30 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 29.01.2024. S2 | 16014,53 | 60,30 | - | - | - | 84,6 | - | - |

| 29.01.2024. S3 | 5318,2 | 146,60 | - | - | 99,3 | - | - | - |

| 05.02.2024. S1 | 10289 | 60,40 | - | - | 137,3 | - | - | - |

| 05.02.2024. S2 | 16049,5 | 32,90 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 05.02.2024. S3 | 16783,49 | 35,90 | - | - | 59,7 | - | - | - |

| 14.02.2024. S1 | 3128,26 | 174,70 | - | - | 241,0 | - | - | - |

| 14.02.2024. S2 | 3533,74 | 95,90 | - | - | 186,4 | - | - | - |

| 14.02.2024. S3 | 11010,7 | 28,30 | - | - | 56,5 | - | - | - |

| 19.02.2024. S1 | 1597,98 | 150,90 | - | - | 137,9 | - | - | - |

| 19.02.2024. S2 | 1989,23 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 19.02.2024. S3 | 1759,86 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10.04.2024. S1 | 7349,2 | 100,60 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10.04.2024. S2 | 7963,33 | 86,30 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10.04.2024. S3 | 8438,44 | 92,70 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15.04.2024. S1 | 5562,55 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15.04.2024. S2 | 7380,33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15.04.2024. S3 | 7141,97 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 24.04.2024. S1 | 7174,9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 24.04.2024. S2 | 12457,55 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 24.04.2024. S3 | 7901,95 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 28.04.2024. S1 | 5572,41 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 28.04.2024. S2 | 10633,13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 28.04.2024. S3 | 6835,4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 06.05.2024. S1 | 3958,01 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 06.05.2024. S2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 06.05.2024. S3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 20.05.2024. S1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 20.05.2024. S2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 20.05.2024. S3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

3. Discussion

3.1. Variability of Azaspiracids at Sampling Sites – Toxin Profiles

3.2. Origin of Detected Analogs

3.3. Temporal Dynamics of an Analog Occurrence

3.4. Contribution of Unregulated Analogues to Total Toxicity

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Samples

4.1.1. Sample Preparation for LC-MS/MS Analysis

4.1.2. Certified Reference Materials

4.1.3. Detection of Lipophilic Toxins Using the LC-MS/MS Method

4.1.4. Characterization of AZA Toxins Using High Resolution Mass Spectrometry

4.2. Study Area

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AZAs | Azaspiracids |

| DSP | Diarrheic Shellfish Poisoning |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography-tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| ACN | Acetonitrile |

| FA | Formic Acid |

| AF | Ammonium Formate |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| LOQ | Limit of Quantification |

| S/N | Signal to noise |

| CRMs | Certified Reference Materials |

| OA | Okadaic Acid |

| DTX-1 | Dinophysistoxin-1 |

| DTX-2 | Dinophysistoxin-2 |

| hYTX | 1-homoYessotoxin |

| PTX-2 | Pectenotoxin-2 |

| YTX | Yessotoxin |

| GYM | Gymnodimine A |

| SPX-1 | 13-desmethylspirolide C |

| FDMT1 | Freeze-Dried Mussel Tissue |

| RT | Retention Time |

| UHPLC | Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| ESI | Electrospray Ionisation |

| TOF-MS | Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry |

| SRMHR | Selected Reaction Monitoring High Resolution |

| ISVF | Ion Spray Voltage Front |

| CE | Collision Energy |

| DP | Declustering Potential |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| TEFs | Toxicity Equivalency Factors |

References

- McMahon, T.; Silke, J. Winter toxicity of unknown aetiology in mussels. Harmful Algae News, 1996, 14, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Satake, M.; Ofuji, K.; Naoki, H.; James, K.J.; Furey, A.; McMahon, T.; Silke, J.; Yasumoto, T. Azaspiracid, a new marine toxin having unique spiro ring assemblies, isolated from Irish mussels, Mytilus edulis. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1998, 120, 9967–9968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, M.; Miles, C.O.; Løvberg, K.L.E.; Kryuchkov, F.; Wright, E.J.; Mudge, E.M.; Kilcoyne, J.; Samdal, I.A. In Vitro Metabolism of Azaspiracids 1-3 with a Hepatopancreatic Fraction from Blue Mussels (Mytilus edulis). J. Agric. Food Chem., 2021, 69, 11322–11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, K. J.; Moroney, C.; Roden, C.; Satake, M. , Yasumoto, T.; Lehane, M.; Furey, A. Ubiquitous ‘benign’ alga emerges as the cause of shellfish contamination responsible for the human toxic syndrome, azaspiracid poisoning. Toxicon, 2003, 41, 145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillmann, U.; Elbrächter, M.; Krock, B.; John, U.; Cembella, A.D. Azadinium spinosum gen. et sp nov (Dinophyceae) identified as a primary producer ofazaspiracid toxins. Eur. J. Phycol. 2009, 44, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krock, B.; Tillmann, U.; Tebben, J.; Trefault, N.; Gu, H. Two novel azaspiracids from Azadinium poporum, and a comprehensive compilation of azaspiracids produced by Amphidomataceae, (Dinophyceae). Harmful Algae 2019, 82, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, U.; Elbrächter, M.; Gottschling, M.; Gu, H.; Jeong, H.J.; Krock, B.; Nézan, E.; Potvin, E.; Salas, R.; Soehner, S. The dinophycean genus Azadinium and related species – morphological and molecular characterization, biogeography, and toxins. In: Kim, H.G., B. Reguera, G.M. Hallegraeff, C.K. Lee, M.S. Han and J.K. Choi. (eds). "Harmful Algae 2012, Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Harmful Algae". International Society for the Study of Harmful Algae. 2014, 149-152.

- Tillmann, U.; Jaén, D.; Fernández, L.; Gottschling, M.; Witt, M.; Blanco, J.; Krock, B. Amphidoma languida (Amphidomatacea, Dinophyceae) with a novel azaspiracid toxin profile identified as the cause of molluscan contamination at the Atlantic coast of southern Spain. Harmful Algae 2017, 62, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krock, B.; Tillmann, U.; Voß, D.; Koch, B.P.; Salas, R.; Witt, M.; Potvin, E.; Jeong, H.J. New azaspiracids in Amphidomataceae (Dynophyceae). Toxicon 2012, 60, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, U.; Edvardsen, B.; Krock, B.; Smith, K.F.; Paterson, R.F.; Voß, D. Diversity, distribution, and azaspiracids of Amphidomataceae (Dinophyceae) along the Norwegian coast. Harmful Algae 2018, 80, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percopo, I.; Siano, R.; Rossi, R.; Soprano, V.; Sarno, D.; Zingone, A. A new potentially toxic Azadinium species (Dinophyceae) from the Mediterranean Sea, A. dexteroporum sp. nov. J. Phycol. 2013, 49, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Dell’Aversano, C.; Krock, B.; Ciminiello, P.; Percopo, I.; Tillmann, U.; Soprano, V.; Zingone, A. Mediterranean Azadinium dexteroporum (Dinophyceae) produces six novel azaspiracids and azaspiracid-35: a structural study by a multi-platform mass spectrometry approach. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toebe, K.; Joshi, A.R.; Messtorff, P. , Tillmann U., Cembella A., Uwe John U., Molecular discrimination of taxa within the dinoflagellate genus Azadinium, the source of azaspiracid toxins. J. Plankton Res. 2013, 35, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wietkamp, S.; Tillmann, U.; Clarke, D.; Toebe, K. Molecular detection and quantification of the azaspiracid-producing dinoflagellate Amphidoma languida (Amphidomataceae, Dinophyceae). J. Plankton Res. 2019, 41, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, W.; Sun, M.; Cui, Y.; Wang, L. ; Current Research Status of Azaspiracids. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reale, O.; Huguet, A.; Fessard, V. Novel Insights on the Toxicity of Phycotoxins on the Gut through the Targeting of Enteric Glial Cells. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilcoyne, J.; Nulty, C.; Jauffrais, T.; McCarron, P.; Herve, F.; Foley, B.; Rise, F.; Crain, S.; Wilkins, A.L.; Twiner, M.J.; Hess, P.; Miles, C.O. Isolation, Structure Elucidation, Relative LC-MS Response, and in Vitro Toxicity of Azaspiracids from the Dinoflagellate Azadinium spinosum. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2465–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, P.; McCarron, P.; Krock, B. Azaspiracids: chemistry, biosynthesis, metabolism, and detection. In Botana, L. M. (Ed.), Marine and Freshwater Toxins 2015, 763-788. CRC Press.

- Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin. OJ L 139, 30.4.2004, p. 55–205.

- Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Controls Guidance. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, 2022, (240) 402-2300.

- Botana, L. M.; Vilariño, N.; Alfonso, A. New insights into azaspiracid poisoning syndrome: toxicity and molecular targets. Toxins 2019, 11, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Ofuji, K.; Satake, M.; McMahon, T.; Silke, J.; James, K.J.; Naoki, H.; Oshima, Y.; Yasumoto, T. Two Analogs of Azaspiracid Isolated from Mussels,Mytilus edulis, Involved in Human Intoxication in Ireland. Nat. Toxins 1999, 7, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brombacher, S.; Edmonds, S.; Volmer, D.A. Studies on azaspiracid biotoxins. II. Mass spectral behavior and structural elucidation of azaspiracid analogs. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2002, 16, 2306–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehmann, N.; Hess, P.; Quilliam, M. A. Discovery of new analogs of the marine biotoxin azaspiracid in blue mussels (Mytilus edulis) by ultra-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 2008, 22, 549-558.

- Krock, B.; Tillmann, U.; Witt, M.; Gu, H. Azaspiracid variability of Azadinium poporum (Dinophyceae) from the China Sea. Harmful Algae 2014, 36, 22–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krock, B.; Tillmann, U.; Potvin, É.; Jeong, H.J.; Drebing, W.; Kilcoyne, J.; Al-Jorani, A.; Twiner, M.J.; Göthel, Q.; Köck, M. ; Structure elucidation and in vitro toxicity of new azaspiracids isolated from the marine dinoflagellate Azadinium poporum. MarDrugs 2015, 13, 6687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebben, J.; Zurhelle, C.; Tubaro, A.; Samdal, I.A.; Krock, B.; Kilcoyne, J.; Sosa, S.; Trainer, V.L.; Deeds, J.R.; Tillmann, U. Structure and toxicity of AZA-59, an azaspiracid shellfish poisoning toxin produced by Azadinium poporum (Dinophyceae). Harmful Algae 2023, 124, 102388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K.J.; Sierra, M.D.; Lehane, M.; Braña Magdalena, A.; Furey, A. Detection of five new hydroxyl analogues of azaspiracids in shellfish using multiple tandem mass spectrometry. Toxicon 2003, 41, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchiocchi, S.; Siracusa, M.; Ruzzi, A.; Gorbi, S.; Ercolessi, M.; Cosentino, MA.; Ammazzalorso, P.; Orletti, R. Two-year study of lipophilic marine toxin profile in mussels of the North-central Adriatic Sea: First report of azaspiracids in Mediterranean seafood. Toxicon 2015, 108, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Krock, B.; Mertens, K.N.; Nézan, E.; Chomérat, N.; Bilien, G.; Tillmann, U.; Gu, H. Adding new pieces to the Azadinium(Dinophyceae) diversity and biogeography puzzle: Non-toxigenic Azadinium zhuanum sp. nov. from China, toxigenic A. poporum from the Mediterranean, and a non-toxigenic A. dalianense from the French Atlantic. Harmful Algae 2017, 66, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Krock, B.; Giannakourou, A.; Venetsanopoulou, A.; Pagou, K.; Tillmann, U.; Gu, H. Sympatric occurrence of two Azadinium poporum ribotypes in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Harmful Algae 2018, 78, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilcoyne, J.; McCarron, P.; Twiner, M.J.; Rise, F.; Hess, P.; Wilkins, A.L.; Miles, C.O. Identification of 21,22-dehydroazaspiracids in mussels (Mytilus edulis) and in vitro toxicity of Azaspiracid-26. J. Mol. Evol. 2018, 81, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilcoyne, J.; Twiner, M.J.; McCarron, P.; Crain, S.; Giddings, S.D.; Foley, B.; Rise, F.; Hess, P.; Wilkins, A.L.; Miles, C.O. Structure Elucidation, Relative LC-MS Response and In Vitro Toxicity of Azaspiracids 7-10 Isolated from Mussels (Mytilus edulis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 5083–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilcoyne, J.; Jauffrais, T.; Twiner, M.J.; Doucette, G.J.; Aasen Bunes, J.A.; Sosa, S.; Krock, B.; Séhet, V.; Nulty, C.; Salas, R.; Clarke, D.; Geraghty, J.; Duffy, C.; Foley, B.; John, U.; Quilliam, M.A.; McCarron, P.; Miles, C.O.; Silke, J.; Cembella, A.; Tillmann, U.; Hess, P. AZASPIRACIDS – toxicological evaluation, test methods and identifcation of the source organisms (ASTOX II) Technical Report Marine Institutem Galway 2014, p. 188 Ireland (2014) (ISSN:2009-3195).

| Name | Exact mass | Calculated mass | Δ, ppm | RT, min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZA-2 | 856.5205 | 856.5211 | -0.7 | 5.78 |

| AZA-6 | 842.5051 | 842.5055 | -0.5 | 4.83 |

| AZA-9 | 858.4967 | 858.5004 | -4.3 | 3.56 |

| AZA-10 | 858.5021 | 858.5004 | 2.0 | 3.91 |

| AZA-19 | 886.4949 | 886.4953 | -0.5 | 4.09 |

| AZA-41 | 854.5044 | 854.5050 | -0.7 | 5.36 |

| AZA-43 | 828.4894 | 828.4892 | 0.2 | 4.63 |

| 884.5 | 884.4928 | 884.4791 | 15.5 | 3.89 |

| Compound name | Precursor ion (m/z) | Product ions (m/z) | Adduct | Collision energy (eV) | Fragmentor voltage (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZA-1 | 842.5 | 824.5; 806.5 | [M+H]+ | 30; 42 | 230 |

| AZA-2 | 856.5 | 838.5; 820.5 | [M+H]+ | 30;42 | 210 |

| AZA-3 | 828.5 | 810.5; 792.5 | [M+H]+ | 28;42 | 210 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).