Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

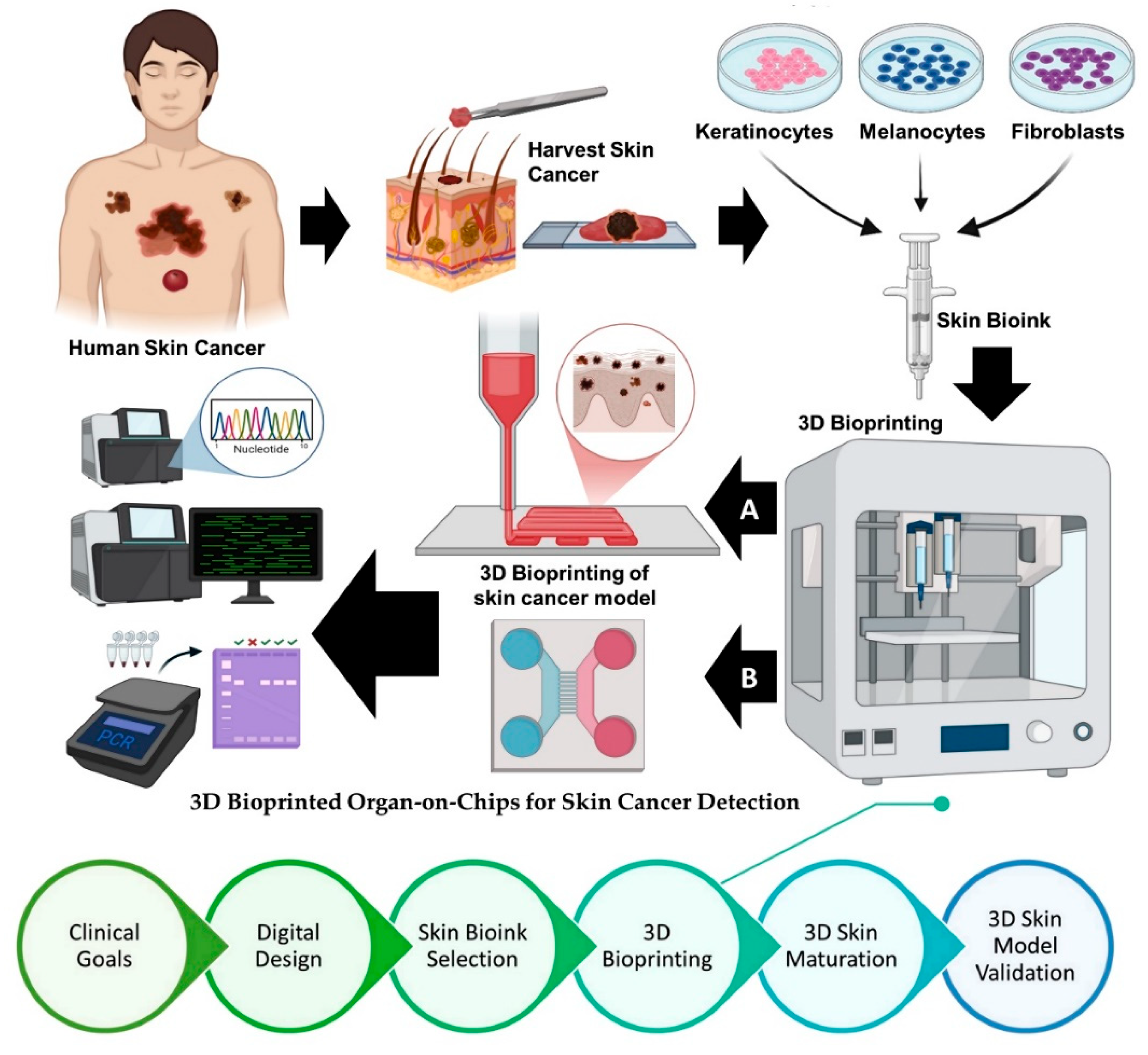

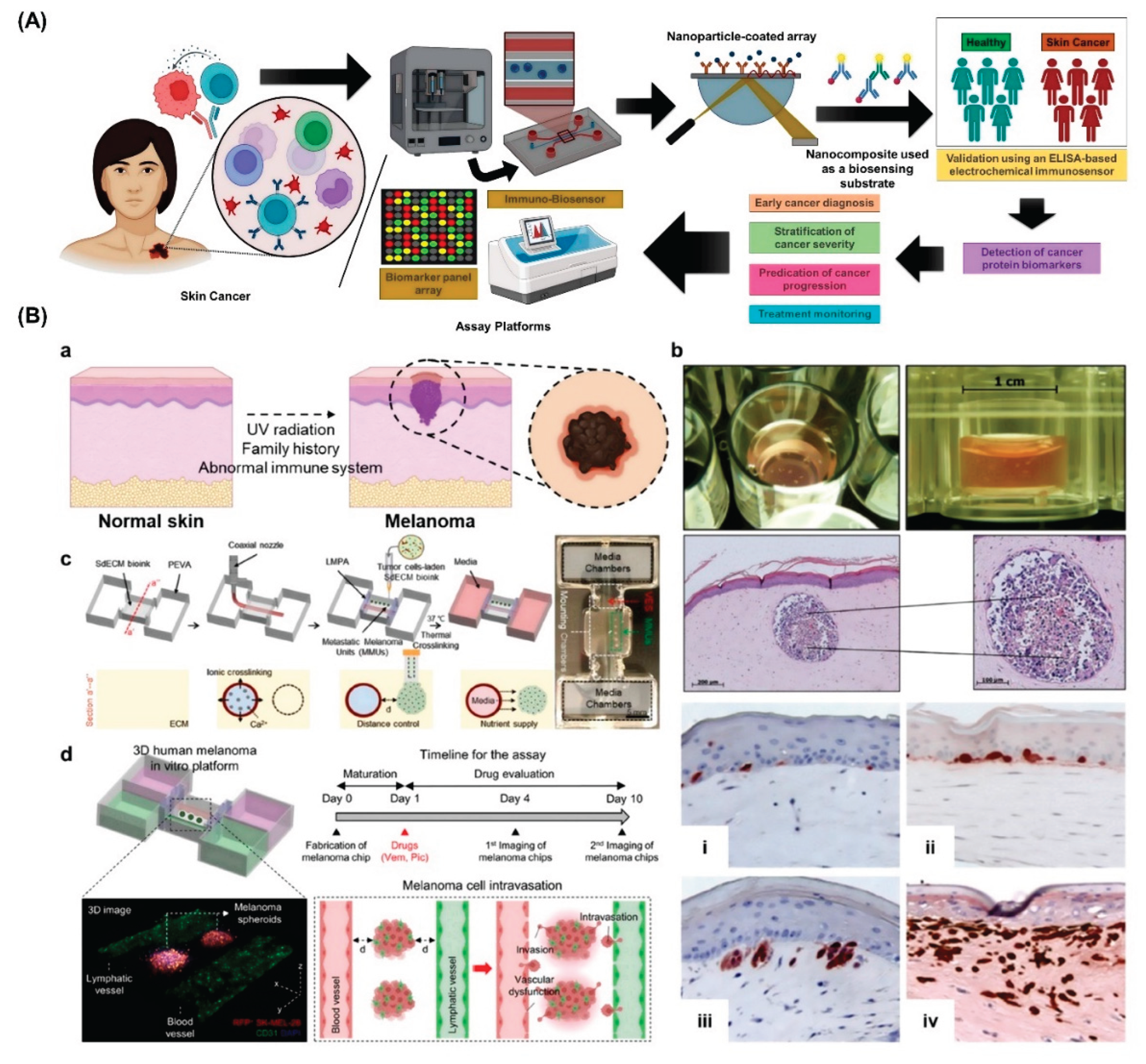

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

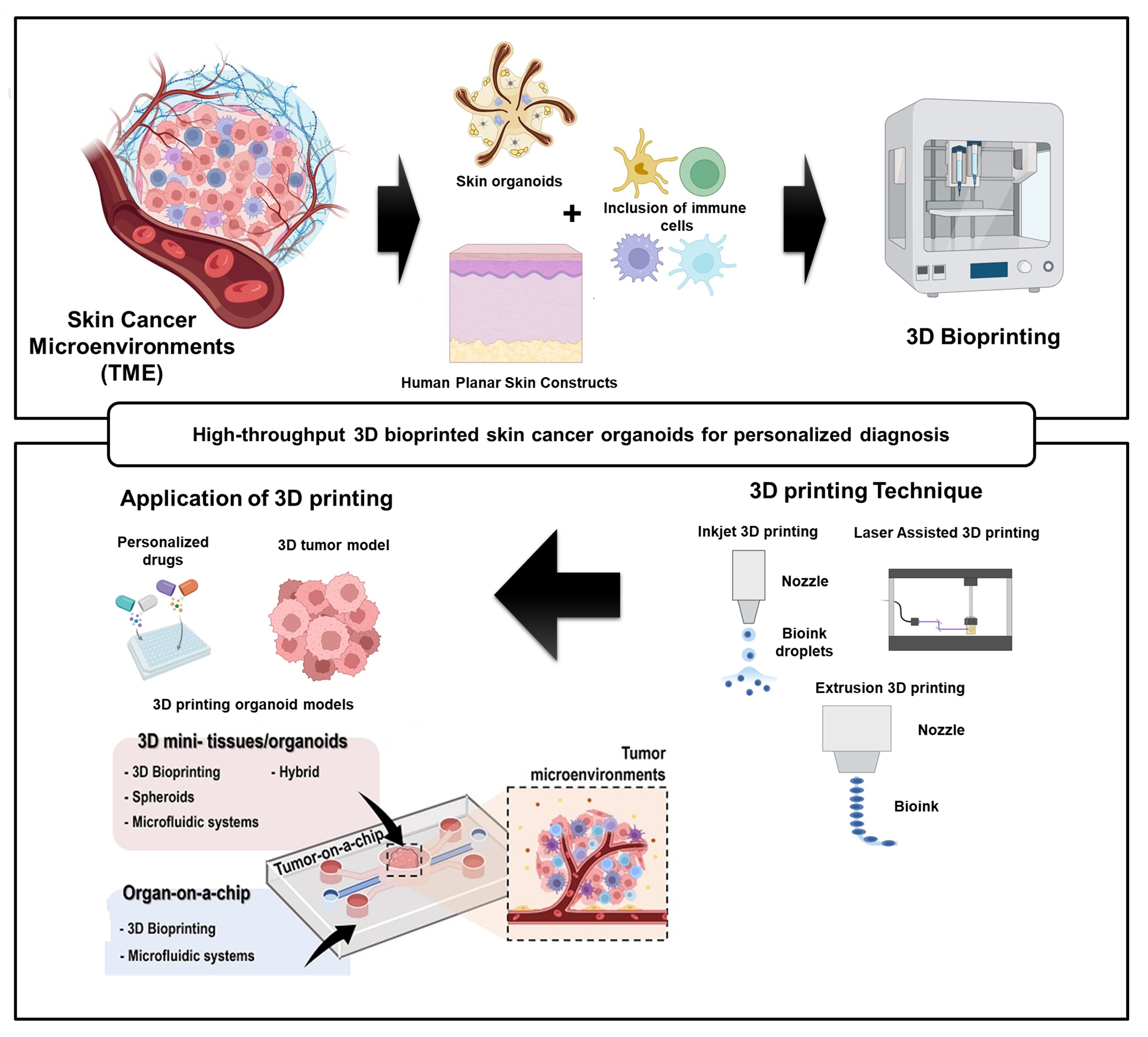

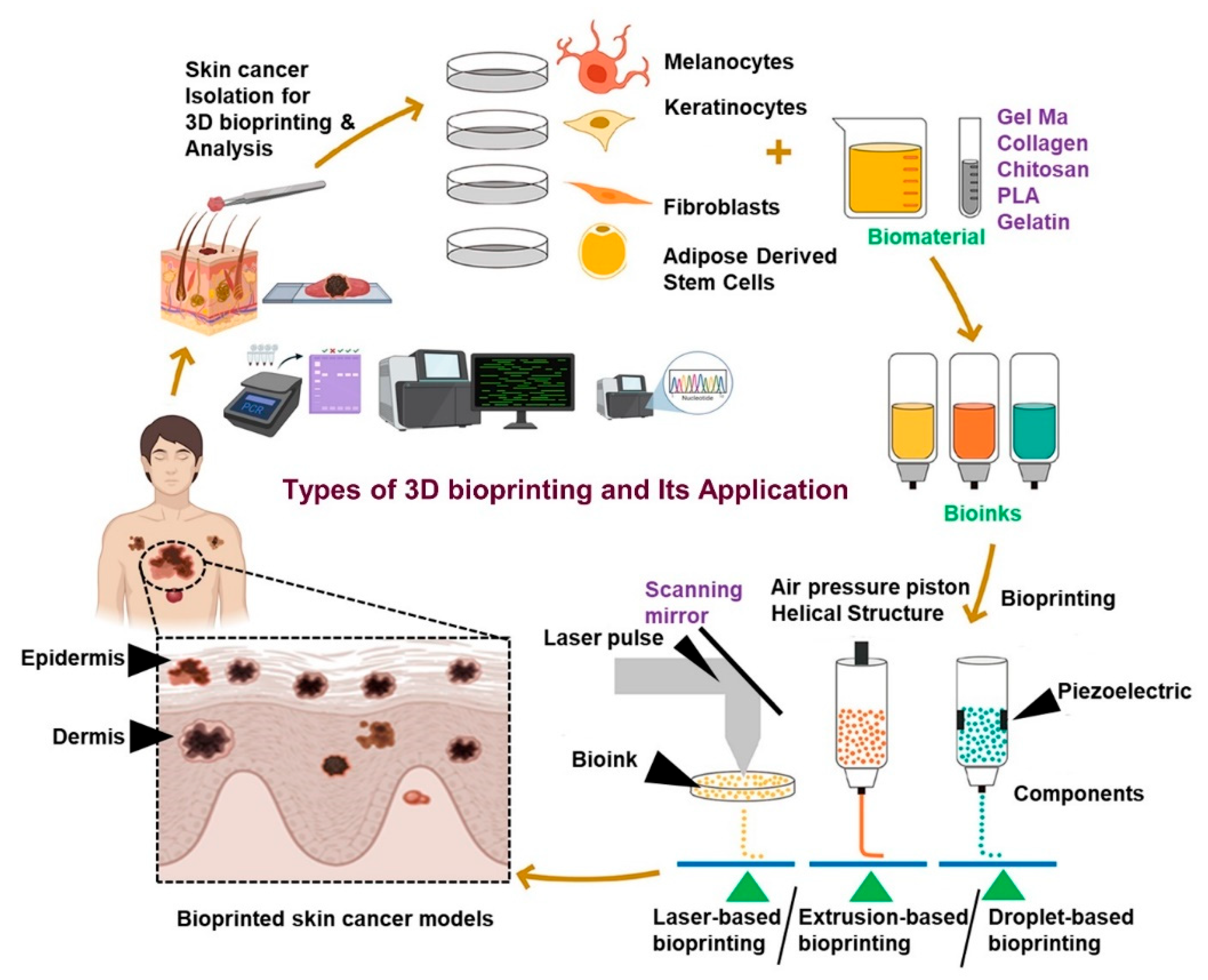

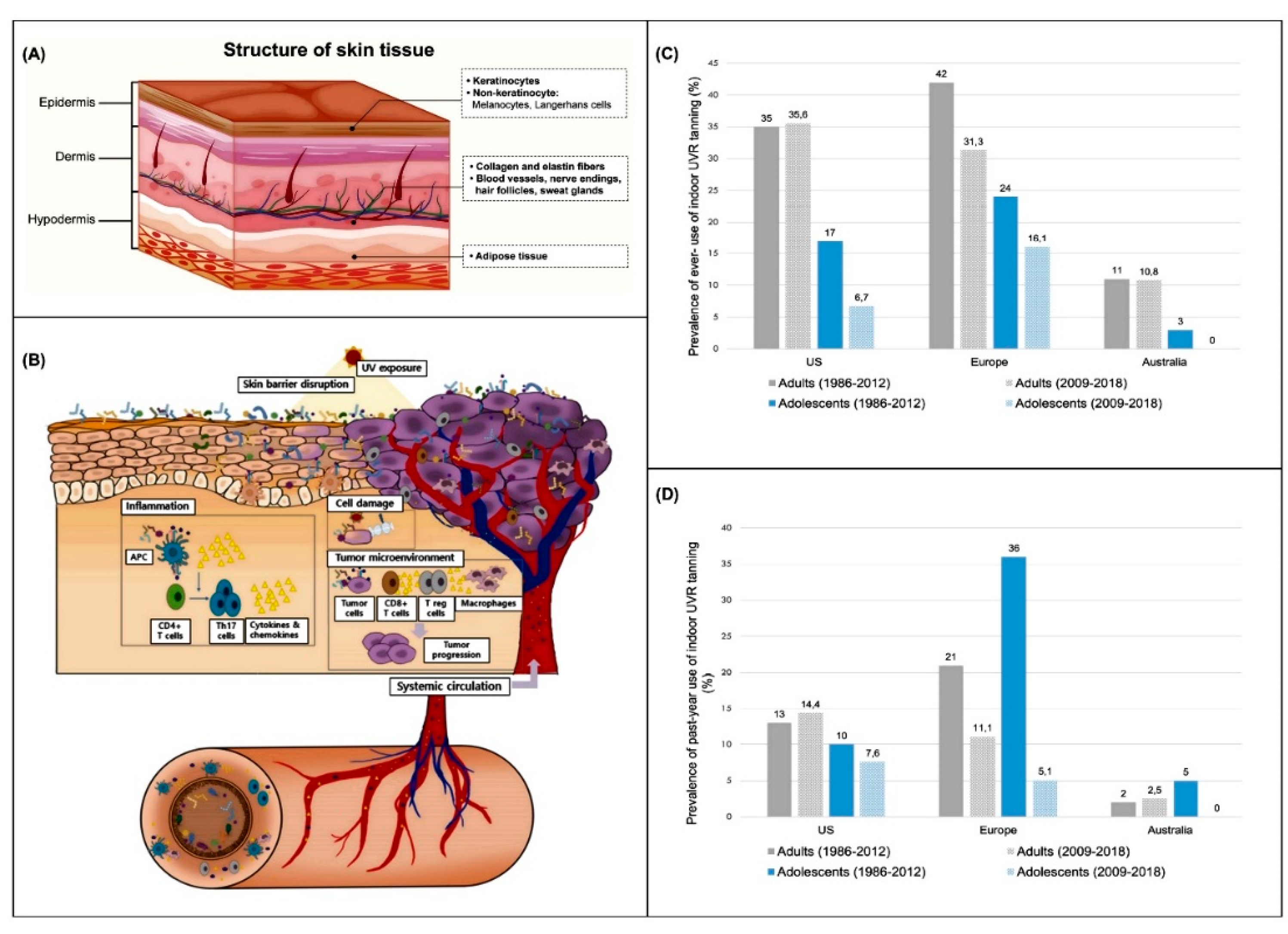

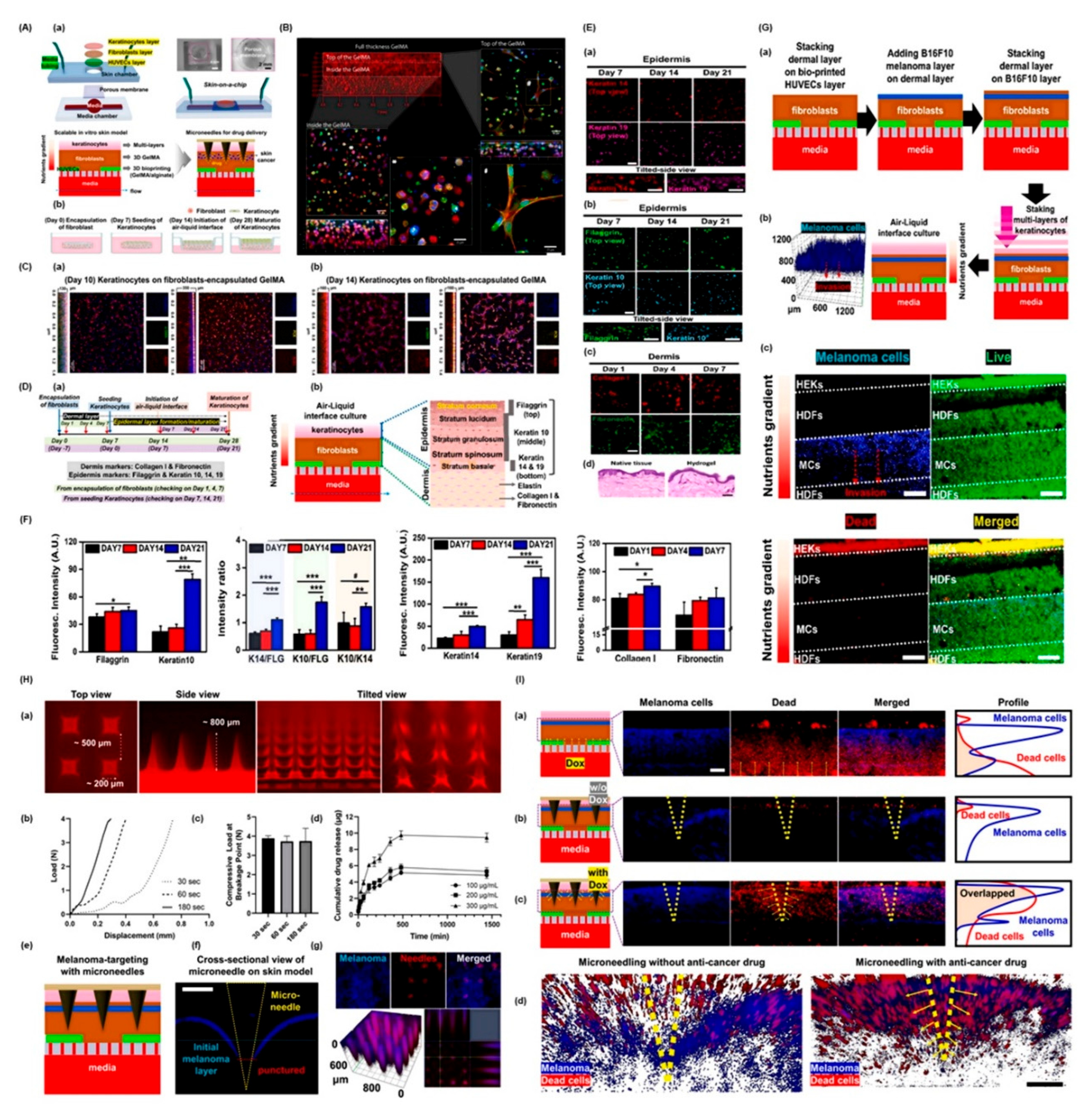

2. Advances in Skin Cancer Modeling

3. Bioprinting Technologies for Skin Cancer Organoids

4. High-Throughput Strategies for Organoid Fabrication

5. 3D Bioprinted Organ-on-Chips for Skin Cancer Detection: A Converging Platform for Precision Diagnostics

6. Applications in Diagnosis and Personalized Therapy

7. Future Perspectives

| Model Type | Method | Cell Composition | Matrix Used | Purpose | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical Melanoma Organoids | Co-culture with fibroblasts | Human skin fibroblasts; melanoma cell lines (WM1366/1205Lu) | Bovine Collagen I | Explore stromal influence on tumor development and resistance | Limited to a single healthy cell type; lacks layered skin structure | [127] |

| Co-culture with endothelial cells | HUVECs; melanoma cell lines (A375/M21) | - | Investigate tumor angiogenesis | Absence of healthy skin cells; non-functional capillary networks | [128] | |

| Three-cell model | Fibroblasts (CCD-1137Sk), keratinocytes (HaCaT), melanoma cells (SK-MEL-28) | Endogenous Collagen IV | Model early-stage melanoma, assess chemotherapy response | No cornified epidermal layer formed | [129] | |

| Five-cell model | Primary fibroblasts, keratinocytes, melanocytes, adipocytes; melanoma cells (SK-MEL-28) | - | Tumor-stroma crosstalk in melanoma | Does not replicate melanoma penetration | Unpublished | |

| Immune-Competent Melanoma Organoids | Air-liquid interface culture | Stromal and immune cells from tumor biopsies | Type I Collagen | Personalized immunotherapy | No healthy skin or epidermal stratification | [130,131,132] |

| Combined lymph node model | Melanoma tissue; lymph node-derived immune cells | Hyaluronic acid/Collagen hydrogel | Personalized treatment screening | Few patient samples; lacks full skin context | [133] | |

| Autologous lymphocyte co-culture | Melanoma tissue; peripheral lymphocytes | Matrigel | Candidate selection for immunotherapy | Limited patient scope; lacks full skin structure | [134] | |

| Melanoma on Planar Skin Constructs | Spheroid/Cell injection | Keratinocytes, fibroblasts; melanoma cell lines (WM35, SK-MEL-28, SBCL2, etc.) | DED, Collagen I, Alvetex scaffold | Study melanoma invasion and drug responses | Missing cell types like melanocytes, vasculature | [135,136,137] |

| Vascularized melanoma model | HMVECs, keratinocytes, fibroblasts; melanoma lines | - | Drug screening in vascularized environment | Time-consuming; low throughput | [138] | |

| Immunocompetent Planar Models | Activated immune cell addition | Keratinocytes; CD4+ T cells or Langerhans cells | DED, Collagen I | Psoriasis, allergy, drug testing | Donor mismatch and limited skin cell diversity | [139,140,141,142] |

| Bioprinted with macrophages | Keratinocytes, fibroblasts, macrophages (M1/M2) | Custom bioink with nanofibrillated cellulose, fibrinogen, etc. | Chronic inflammation (e.g., atopic dermatitis) | Lacks melanocytes, vasculature | [143] | |

| Bioprinted wound models | Keratinocytes, fibroblasts, HUVECs, macrophages | Collagen I + plasma-based fibrin bioink | Wound healing and inflammation | Missing melanocytes | [144] | |

| Immune-Competent Skin Constructs with Melanoma | Co-culture with melanoma and immune cells | Keratinocytes, fibroblasts, melanocytes, melanoma cells, dendritic or T cells | Collagen I, DED | Tumor-immune interaction, progression, and immunotherapy | No vasculature; no leukocyte extravasation | [145,146,147,148] |

| Melanoma-on-a-Chip Systems | Microfluidic integration | Keratinocytes, fibroblasts, melanoma cells (WM-115) | Collagen | Cell-cell crosstalk studies | No stratified skin architecture | [149] |

| Skin-on-chip with immune components | HaCaT, U937 or HL-60 cells, HUVECs | Collagen I | Allergy and immune response modeling | Lacks full dermal/immune composition | [150,151,152] | |

| Melanoma-immune chip systems | Melanoma spheroids, immune cells from biopsy | Collagen I | Immunotherapy and drug screening | No healthy skin structure; immune cell recruitment limited | [153,154] | |

| Vascularized chip with immune cells | HUVECs, melanoma cells (BLM), whole blood | Gelatin | Inflammation modeling | No skin layers included | [155] | |

| Circulating melanoma-neutrophil interactions | Melanoma A-375/A-375 MA2, neutrophils | Fibrin | Tumor cell extravasation, metastasis | Not representative of skin architecture | [156] |

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roky, A.H.; et al. Overview of skin cancer types and prevalence rates across continents. Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapy 2025, 3, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, N.; et al. Skin cancer: understanding the journey of transformation from conventional to advanced treatment approaches. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayyati Kohnehshahri, M.; et al. Current status of skin cancers with a focus on immunology and immunotherapy. Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorino, C.; et al. Immunotherapy in melanoma: advances, pitfalls, and future perspectives. Front Mol Biosci 2024, 11, 1403021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; et al. Advancements in melanoma immunotherapy: the emergence of Extracellular Vesicle Vaccines. Cell Death Discovery 2024, 10, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolathur, K.K.; et al. Molecular Susceptibility and Treatment Challenges in Melanoma. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; et al. Tumor microenvironment: Nurturing cancer cells for immunoevasion and druggable vulnerabilities for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Letters 2025, 611, 217385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, K.; et al. Aspects of the Tumor Microenvironment Involved in Immune Resistance and Drug Resistance. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 656364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; et al. Extracellular matrix dynamics in tumor immunoregulation: from tumor microenvironment to immunotherapy. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2025, 18, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almawash, S. Revolutionary Cancer Therapy for Personalization and Improved Efficacy: Strategies to Overcome Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, M.K.; et al. Mechanisms of Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Melanoma and Strategies to Overcome It. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.C.; Zappasodi, R. A decade of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy in melanoma: understanding the molecular basis for immune sensitivity and resistance. Nat Immunol 2022, 23, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, A.K.; Gao, G.; Kim, B.S. Applications of 3D bioprinting technology in induced pluripotent stem cells-based tissue engineering. Micromachines 2022, 13, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; et al. In-bath Bioprinting of Pre-vascularized Skin Patches with Different Geometrical Patterns for Effective Skin Regeneration. 한국정밀공학회 2023, 677. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.-Y.; et al. Organoids as Tools for Investigating Skin Aging: Mechanisms, Applications, and Insights. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.R.; et al. The Human Microbiota and Skin Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessinioti, C.; Stratigos, A.J. An Epidemiological Update on Indoor Tanning and the Risk of Skin Cancers. Current Oncology 2022, 29, 8886–8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, M.R.; et al. International Prevalence of Indoor Tanning: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatology 2014, 150, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Acevedo, A.J.; et al. Indoor tanning prevalence after the International Agency for Research on Cancer statement on carcinogenicity of artificial tanning devices: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Dermatology 2020, 182, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, M.; et al. A Study on the Effect of Bioprinted Skin Patches with Various Vascular Patterns on Wound Healing. 한국정밀공학회 2024, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Kapałczyńska, M.; et al. 2D and 3D cell cultures - a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Arch Med Sci 2018, 14, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; et al. Spheroids in cancer research: Recent advances and opportunities. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2024, 100, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipiya, V.V.; et al. Comparison of primary and passaged tumor cell cultures and their application in personalized medicine. Explor Target Antitumor Ther 2024, 5, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; et al. Tumor-microenvironment-on-a-chip: the construction and application. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, P. Rebuilding the microenvironment of primary tumors in humans: a focus on stroma. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2024, 56, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristini, N.; et al. Exploring bone-tumor interactions through 3D in vitro models: Implications for primary and metastatic cancers. J Bone Oncol 2025, 53, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; et al. Safety assessment of drugs in pregnancy: An update of pharmacological models. Placenta 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budharaju, H.; Singh, R.K.; Kim, H.-W. Bioprinting for drug screening: A path toward reducing animal testing or redefining preclinical research? Bioactive Materials 2025, 51, 993–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakopoulou, P.; et al. Recent progress in translational engineered in vitro models of the central nervous system. Brain 2020, 143, 3181–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.S.; Jaenisch, R.; Mooney, D.J. Engineered tissues and strategies to overcome challenges in drug development. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2020, 158, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshafiei, M.; et al. Advancements in tissue and organ 3D bioprinting: Current techniques, applications, and future perspectives. Materials & Design 2024, 240, 112853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Q.; Zourob, M. 3D Bioprinting at the Frontier of Regenerative Medicine, Pharmaceutical, and Food Industries. Front Med Technol 2020, 2, 607648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, A.C.; et al. Three-Dimensional Printing/Bioprinting and Cellular Therapies for Regenerative Medicine: Current Advances. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2025, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; et al. 3D Biomimetic Models to Reconstitute Tumor Microenvironment In Vitro: Spheroids, Organoids, and Tumor-on-a-Chip. Adv Healthc Mater 2023, 12, e2202609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; et al. Cancer-on-a-chip for precision cancer medicine. Lab on a Chip 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristini, N.; et al. Exploring bone-tumor interactions through 3D in vitro models: Implications for primary and metastatic cancers. Journal of Bone Oncology 2025, 53, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; et al. Vascularization strategies for human skin tissue engineering via 3D bioprinting. International Journal of Bioprinting 2024, 10, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cong, L.; Cong, X. Patient-Derived Organoids in Precision Medicine: Drug Screening, Organoid-on-a-Chip and Living Organoid Biobank. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 762184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jin, P. Advances and Challenges in 3D Bioprinted Cancer Models: Opportunities for Personalized Medicine and Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2025, 17, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Román, M.; et al. Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer: A Genetic Update and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; et al. Global, regional, and national trends in the burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer: insights from the global burden of disease study 1990–2021. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.M.R.; et al. Wnt Signaling Pathways in Keratinocyte Carcinomas. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riihilä, P.; Nissinen, L.; Kähäri, V.M. Matrix metalloproteinases in keratinocyte carcinomas. Exp Dermatol 2021, 30, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainese-Marque, O.; et al. Contribution of Keratinocytes in Skin Cancer Initiation and Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; et al. Advancement in cancer vasculogenesis modeling through 3D Bioprinting Technology. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manduca, N.; et al. 3D cancer models: One step closer to in vitro human studies. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1175503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, P.; et al. Preclinical models in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. British Journal of Cancer 2023, 128, 1819–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionita, I.; et al. Experimental Models for Rare Melanoma Research—The Niche That Needs to Be Addressed. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; et al. Application of Animal Models in Cancer Research: Recent Progress and Future Prospects. Cancer Manag Res 2021, 13, 2455–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; et al. In vitro and in vivo experimental models for cancer immunotherapy study. Current Research in Biotechnology 2024, 7, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, L.; Agarwal, S.; Tanner, K. Preclinical models for drug discovery for metastatic disease. Cell 2023, 186, 1792–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Patient-derived xenograft models in cancer therapy: technologies and applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; et al. Challenges and Prospects of Patient-Derived Xenografts for Cancer Research. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, M.; et al. Patient-Derived Xenografts of Non Small Cell Lung Cancer: Resurgence of an Old Model for Investigation of Modern Concepts of Tailored Therapy and Cancer Stem Cells. BioMed Research International 2012, 2012, 568567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biray Avci, C.; et al. Tumor microenvironment and cancer metastasis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1442888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Master Tumor Microenvironment Modifiers. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, K.; He, T. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: heterogeneity, tumorigenicity and therapeutic targets. Mol Biomed 2024, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, A.-M.; et al. Tissue mechanics in tumor heterogeneity and aggression. Trends in Cancer 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, M.E.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts as abettors of tumor progression at the crossroads of EMT and therapy resistance. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, M.; et al. 3D Bioprinting-Assisted Engineering of Stem Cell-Laden Hybrid Biopatches With Distinct Geometric Patterns Considering the Mechanical Characteristics of Regular and Irregular Connective Tissues. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2025, 2502763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustine, R.; et al. 3D Bioprinted cancer models: Revolutionizing personalized cancer therapy. Transl Oncol 2021, 14, 101015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzaglia, C.; Huang, Y.Y.S.; Shields, J.D. Advancing tumor microenvironment and lymphoid tissue research through 3D bioprinting and biofabrication. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2025, 217, 115485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; et al. Advances in 3D skin bioprinting for wound healing and disease modeling. Regen Biomater 2023, 10, rbac105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; et al. Development of 3D bioprinting: From printing methods to biomedical applications. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 15, 529–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budharaju, H.; Sundaramurthi, D.; Sethuraman, S. Embedded 3D bioprinting – An emerging strategy to fabricate biomimetic & large vascularized tissue constructs. Bioactive Materials 2024, 32, 356–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor-Ozkerim, P.S.; et al. Bioinks for 3D bioprinting: an overview. Biomater Sci 2018, 6, 915–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.; et al. 3D Bioprinting: An Enabling Technology to Understand Melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, I.; et al. 3D Bioprinting as a Powerful Technique for Recreating the Tumor Microenvironment. Gels 2023, 9, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Koehler, K.R. Skin organoids: A new human model for developmental and translational research. Exp Dermatol 2021, 30, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teertam, S.K.; Setaluri, V.; Ayuso, J.M. Advances in Microengineered Platforms for Skin Research. JID Innovations 2025, 5, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Z.X.; et al. Bioengineered skin organoids: from development to applications. Mil Med Res 2023, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; et al. Converging bioprinting and organoids to better recapitulate the tumor microenvironment. Trends in Biotechnology 2024, 42, 648–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.G.; Choi, Y.M.; Jang, J. 3D Bioprinting-Based Vascularized Tissue Models Mimicking Tissue-Specific Architecture and Pathophysiology for in vitro Studies. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9, 685507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; et al. Using Spheroids as Building Blocks Towards 3D Bioprinting of Tumor Microenvironment. Int J Bioprint 2021, 7, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; et al. High-throughput solutions in tumor organoids: from culture to drug screening. Stem Cells 2025, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; et al. Biomaterial-assisted organoid technology for disease modeling and drug screening. Materials Today Bio 2025, 30, 101438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; et al. Construction of tumor organoids and their application to cancer research and therapy. Theranostics 2024, 14, 1101–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; et al. 3D bioprinting platform development for high-throughput cancer organoid models construction and drug evaluation. Biofabrication 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; et al. AI-driven 3D bioprinting for regenerative medicine: From bench to bedside. Bioactive Materials 2025, 45, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebon, P.J.; et al. Drug screening at single-organoid resolution via bioprinting and interferometry. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; et al. Exploring the Angiogenic Potential of Skin Patches with Endothelial Cell Patterns Fabricated via In-Bath 3D Bioprinting Using Light-Activated Bioink for Enhanced Wound Healing. Biomaterials 2025, 123575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, A.S.; et al. Organ-on-a-Chip: Ubi sumus? Fundamentals and Design Aspects. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T. Organ-on-a-chip microengineering for bio-mimicking disease models and revolutionizing drug discovery. Biosensors and Bioelectronics X 2022, 11, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, S.; et al. Applications of Microfluidics and Organ-on-a-Chip in Cancer Research. Biosensors (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierke, C.T. Bioprinting of Cells, Organoids and Organs-on-a-Chip Together with Hydrogels Improves Structural and Mechanical Cues. Cells 2024, 13, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; et al. Emerging Molecular and Clinical Challenges in Managing Lung Cancer Treatment during the Covid-19 Infection. Journal of Cancer and Tumor International 2024, 14, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, N.R.; et al. A human skin-on-a-chip platform for microneedling-driven skin cancer treatment. Materials Today Bio 2025, 30, 101399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiung, N.; et al. Organoid-based tissue engineering for advanced tissue repair and reconstruction. Materials Today Bio 2025, 33, 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; et al. Bridging the organoid translational gap: integrating standardization and micropatterning for drug screening in clinical and pharmaceutical medicine. Life Med 2024, 3, lnae016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto de Barros, N.; et al. Engineered organoids for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2023, 203, 115142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; et al. Scalable production of uniform and mature organoids in a 3D geometrically-engineered permeable membrane. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwangbo, H.; et al. Tumor-on-a-chip models combined with mini-tissues or organoids for engineering tumor tissues. Theranostics 2024, 14, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosmans, C.; et al. Towards single-cell bioprinting: micropatterning tools for organ-on-chip development. Trends in Biotechnology 2024, 42, 739–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani Dabbagh, S.; et al. 3D bioprinted organ-on-chips. Aggregate 2023, 4, e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaebler, D.; Hachey, S.J.; Hughes, C.C.W. Improving tumor microenvironment assessment in chip systems through next-generation technology integration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2024, 12, 1462293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannitelli, S.M.; et al. On-chip recapitulation of the tumor microenvironment: A decade of progress. Biomaterials 2024, 306, 122482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; et al. On-chip modeling of tumor evolution: Advances, challenges and opportunities. Materials Today Bio 2023, 21, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenuwara, G.; et al. Biosensor-Enhanced Organ-on-a-Chip Models for Investigating Glioblastoma Tumor Microenvironment Dynamics. Sensors 2024, 24, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, S.R.; et al. Vessel-on-a-chip models for studying microvascular physiology, transport, and function in vitro. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2021, 320, C92–C105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; et al. Revolutionizing Drug Discovery: The Impact of Distinct Designs and Biosensor Integration in Microfluidics-Based Organ-on-a-Chip Technology. Biosensors (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; et al. Engineering microneedles for biosensing and drug delivery. Bioactive Materials 2025, 52, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, A.R.; et al. Organ-on-chip platforms for nanoparticle toxicity and efficacy assessment: Advancing beyond traditional in vitro and in vivo models. Materials Today Bio 2025, 33, 102053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Organ-on-a-Chip Applications in Microfluidic Platforms. Micromachines 2025, 16, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; et al. The blood–brain barrier: Structure, regulation and drug delivery. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; et al. Long-lasting Response of Human Circulating T-follicular Helper Cells (cTfh) To Post SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Immunization. Asian Journal of Immunology 2024, 7, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; et al. 3D biofabrication of diseased human skin models in vitro. Biomaterials Research 2023, 27, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; et al. Organoids: development and applications in disease models, drug discovery, precision medicine, and regenerative medicine. MedComm (2020) 2024, 5, e735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzelmann, E.; et al. iPSC-derived and Patient-Derived Organoids: Applications and challenges in scalability and reproducibility as pre-clinical models. Current Research in Toxicology 2024, 7, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; et al. Harnessing the power of artificial intelligence for human living organoid research. Bioactive Materials 2024, 42, 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.A.; et al. Translating complexity and heterogeneity of pancreatic tumor: 3D in vitro to in vivo models. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2021, 174, 265–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, N.; et al. A simple high-throughput approach identifies actionable drug sensitivities in patient-derived tumor organoids. Commun Biol 2019, 2, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skala, M.C.; Deming, D.A.; Kratz, J.D. Technologies to Assess Drug Response and Heterogeneity in Patient-Derived Cancer Organoids. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2022, 24, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kabani, A.; et al. Exploring Experimental Models of Colorectal Cancer: A Critical Appraisal from 2D Cell Systems to Organoids, Humanized Mouse Avatars, Organ-on-Chip, CRISPR Engineering, and AI-Driven Platforms—Challenges and Opportunities for Translational Precision Oncology. Cancers 2025, 17, 2163. [Google Scholar]

- Makesh, K.Y.; et al. A Concise Review of Organoid Tissue Engineering: Regenerative Applications and Precision Medicine. Organoids 2025, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.; et al. Enabling Technologies for Personalized and Precision Medicine. Trends Biotechnol 2020, 38, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, R. Transforming Clinical Research: The Power of High-Throughput Omics Integration. Proteomes 2024, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; et al. Novel research model for in vitro immunotherapy: co-culturing tumor organoids with peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cancer Cell Int 2024, 24, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, N.J.; et al. Modelling the tumor immune microenvironment for precision immunotherapy. Clinical & Translational Immunology 2022, 11, e1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorintan, S.T.; Angelius, C.; Torizal, F.G. Organoid Models in Cancer Immunotherapy: Bioengineering Approach for Personalized Treatment. Immuno 2024, 4, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; et al. Advanced tumor organoid bioprinting strategy for oncology research. Materials Today Bio 2024, 28, 101198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; et al. 3D Bioprinting in Cancer Modeling and Biomedicine: From Print Categories to Biological Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 44076–44100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; et al. Flourishing tumor organoids: History, emerging technology, and application. Bioeng Transl Med 2023, 8, e10559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, V.; et al. Innovative bioinks for 3D bioprinting: Exploring technological potential and regulatory challenges. J Tissue Eng 2025, 16, 20417314241308022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.C.; et al. Animal-derived products in science and current alternatives. Biomaterials Advances 2023, 151, 213428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatoniene, J.; et al. The Future of Medicine: How 3D Printing Is Transforming Pharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, E.H.; et al. Fibroblasts contribute to melanoma tumor growth and drug resistance. Molecular pharmaceutics 2011, 8, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, H.; et al. Tumor cells and their crosstalk with endothelial cells in 3D spheroids. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 10428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klicks, J.; et al. A novel spheroid-based co-culture model mimics loss of keratinocyte differentiation, melanoma cell invasion, and drug-induced selection of ABCB5-expressing cells. BMC cancer 2019, 19, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.T.; et al. Organoid modeling of the tumor immune microenvironment. Cell 2018, 175, 1972–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powley, I.R.; et al. Patient-derived explants (PDEs) as a powerful preclinical platform for anti-cancer drug and biomarker discovery. British journal of cancer 2020, 122, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; et al. Nanoparticle-enabled innate immune stimulation activates endogenous tumor-infiltrating T cells with broad antigen specificities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2016168118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Votanopoulos, K.I.; et al. Model of patient-specific immune-enhanced organoids for immunotherapy screening: feasibility study. Annals of surgical oncology 2020, 27, 1956–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiani, T.; et al. Alternative macrophage polarisation associated with resistance to anti-PD1 blockade is possibly supported by the splicing of FKBP51 immunophilin in melanoma patients. British Journal of Cancer 2020, 122, 1782–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridas, P.; et al. Quantitative comparison of the spreading and invasion of radial growth phase and metastatic melanoma cells in a three-dimensional human skin equivalent model. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörsmann, H.; et al. Development of a human three-dimensional organotypic skin-melanoma spheroid model for in vitro drug testing. Cell death & disease 2013, 4, e719. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, D.S.; et al. A novel fully humanized 3D skin equivalent to model early melanoma invasion. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2015, 14, 2665–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourland, J.; Fradette, J.; Auger, F.A. Tissue-engineered 3D melanoma model with blood and lymphatic capillaries for drug development. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 13191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.U.; et al. Recapitulating T cell infiltration in 3D psoriatic skin models for patient-specific drug testing. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallmeyer, L.; et al. TSLP is a direct trigger for T cell migration in filaggrin-deficient skin equivalents. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosten, I.J.; et al. MUTZ-3 derived Langerhans cells in human skin equivalents show differential migration and phenotypic plasticity after allergen or irritant exposure. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2015, 287, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Bogaard, E.H.; et al. Crosstalk between keratinocytes and T cells in a 3D microenvironment: a model to study inflammatory skin diseases. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2014, 134, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lègues, M.; et al. The world’s first 3D bioprinted immune skin model suitable for screening drugs and ingredients for normal and inflamed skin. IFSCC Magazine 2020, 4, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jara, C.P.; et al. Demonstration of re-epithelialization in a bioprinted human skin equivalent wound model. Bioprinting 2021, 24, e00102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielon, E.; et al. Micro-environmental cross-talk in an organotypic human melanoma-in-skin model directs M2-like monocyte differentiation via IL-10. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy 2020, 69, 2319–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielon, E.; et al. A reconstructed human melanoma-in-skin model to study immune modulatory and angiogenic mechanisms facilitating initial melanoma growth and invasion. Cancers 2023, 15, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Blasio, S.; et al. The tumour microenvironment shapes dendritic cell plasticity in a human organotypic melanoma culture. Nature communications 2020, 11, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; et al. Remodeling of the collagen matrix in aging skin promotes melanoma metastasis and affects immune cell motility. Cancer discovery 2019, 9, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, J.M.; et al. Microfluidic model with air-walls reveals fibroblasts and keratinocytes modulate melanoma cell phenotype, migration, and metabolism. Lab on a Chip 2021, 21, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; et al. Investigations on T cell transmigration in a human skin-on-chip (SoC) model. Lab on a Chip 2021, 21, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, Q.; Ting, F.C.W. In vitro micro-physiological immune-competent model of the human skin. Lab on a Chip 2016, 16, 1899–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, B.S.; et al. Microfluidic skin chip with vasculature for recapitulating the immune response of the skin tissue. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2020, 117, 1853–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R.W.; et al. Ex vivo profiling of PD-1 blockade using organotypic tumor spheroids. Cancer discovery 2018, 8, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; et al. Targeting TBK1 to overcome resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Nature 2023, 615, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Sanchez, N.A.; Goette, M. Role of cell surface proteoglycans in cancer immunotherapy. in Seminars in cancer biology. 2020. Elsevier.

- Chen, M.B.; et al. Inflamed neutrophils sequestered at entrapped tumor cells via chemotactic confinement promote tumor cell extravasation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 7022–7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, M.; et al. Organ-on-a-chip: Quo vademus? Applications and regulatory status. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2025, 249, 114507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; et al. Integrated applications of microfluidics, organoids, and 3D bioprinting in in vitro 3D biomimetic models. IJB 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; et al. Organ-on-a-chip meets artificial intelligence in drug evaluation. Theranostics 2023, 13, 4526–4558. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lin, D.; Feng, N. Harnessing organoid technology in urological cancer: advances and applications in urinary system tumors. World J Surg Oncol 2025, 23, 295. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; et al. Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bioprinting Technique | Specific Bioinks Used | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser-based Bioprinting (e.g., Laser-Assisted, DLW, LIFT) | - Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) - Collagen - Cell-laden hydrogels - Photosensitive hydrogels |

- High spatial resolution (micron-scale precision) - Minimal thermal or mechanical stress on cells - Enables fabrication of complex, multicellular structures, including microvasculature - Supports multi-material patterning |

- Requires photosensitive bioinks - Low throughput for large-scale constructs - High equipment cost and operational complexity - Risk of photothermal damage - Limited bioink compatibility |

| Extrusion-based Bioprinting | - Collagen - Fibrin(ogen) - Gelatin - Hyaluronic acid - Alginate (with embedded cancer cells) - ECM-derived inks - Composite hydrogels |

- Cost-effective and technically simple - Accommodates high -viscosity and high cell -density materials - Suitable for large, tissue-scale constructs - Compatible with diverse bioinks, both natural and synthetic |

- Lower resolution (~100–200 μm) - Shear stress may affect cell viability - Soft constructs prone to collapse without support - Limited fidelity in recreating fine microarchitecture - Balance needed between printability and biofunctionality |

| Droplet-based Bioprinting (e.g., Inkjet, Microvalve, EHD Jetting) | - Collagen - Fibrin – PEG -based hydrogels - Plasma-derived matrices - Low-viscosity bioinks |

- Allows precise droplet -based patterning - High cell viability due to non-contact deposition - Well-suited for multilayered, thin constructs - High reproducibility and low material waste |

- Restricted to low-viscosity materials - Susceptible to nozzle clogging - Poor suitability for thick or volumetric structures - Lacks inherent porosity and mechanical robustness - Limited construct size and load-bearing capacity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).