Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Aging (senescence) is characterized by development of diverse senescent pathologies and diseases, leading eventually to death. The major diseases of aging, including cardiovascular disease, cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), are multifactorial disorders, resulting from complex interactions between multiple etiologies. Here we propose a general account of how different determinants of aging can interact to generate late-life disease. This account, initially drawn from studies of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, depicts senescence as the product a two stage process. The first stage involves the diverse causes of disease prior to aging, that cause disruption of normal biological function. These include infection, mechanical injury and mutation (somatic and inherited). Second, etiologies largely confined to aging: deleterious, late-life consequences of evolved wild-type gene action, including antagonistic pleiotropy. Prior to aging, diverse insults lead to accumulation of various forms of injury that is largely contained, preventing progression to pathology. In later life, wild-type gene action causes loss of containment of latent disruptions, which form foci for pathology development. Pathologies discussed here include late-life recrudescence of infection, osteoarthritis, cancer and consequences of late-life deleterious mutations. Such latent injury foci are analogous to seeds which in later life, in the context of programmatic senescent changes, germinate and develop into disease.

Keywords:

Introduction

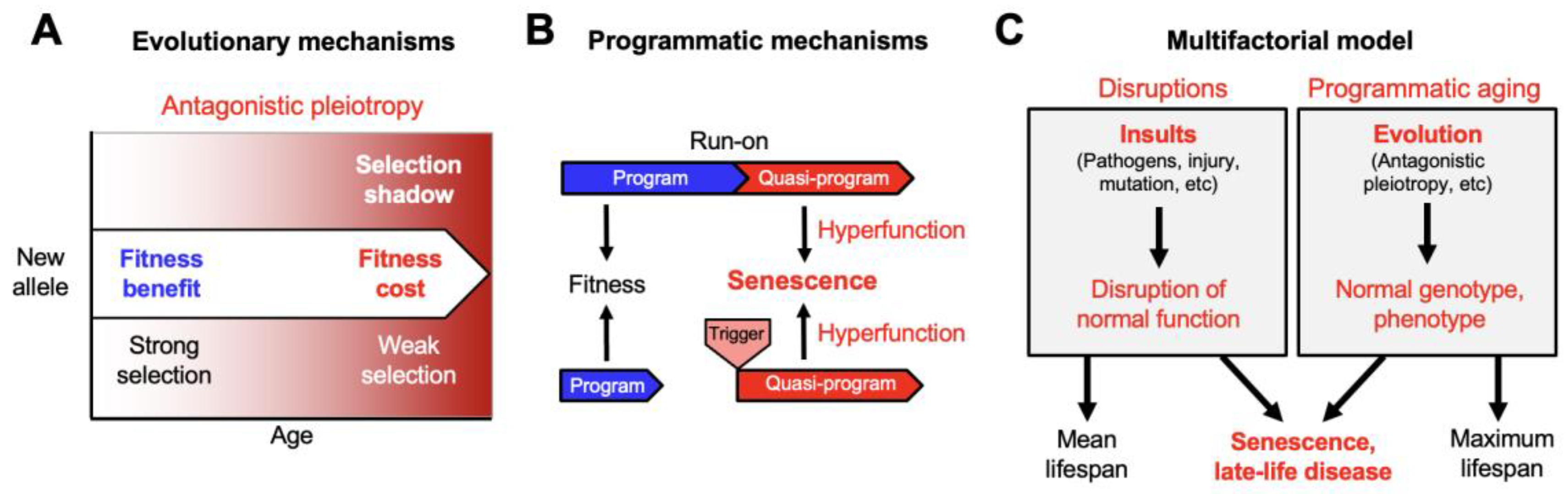

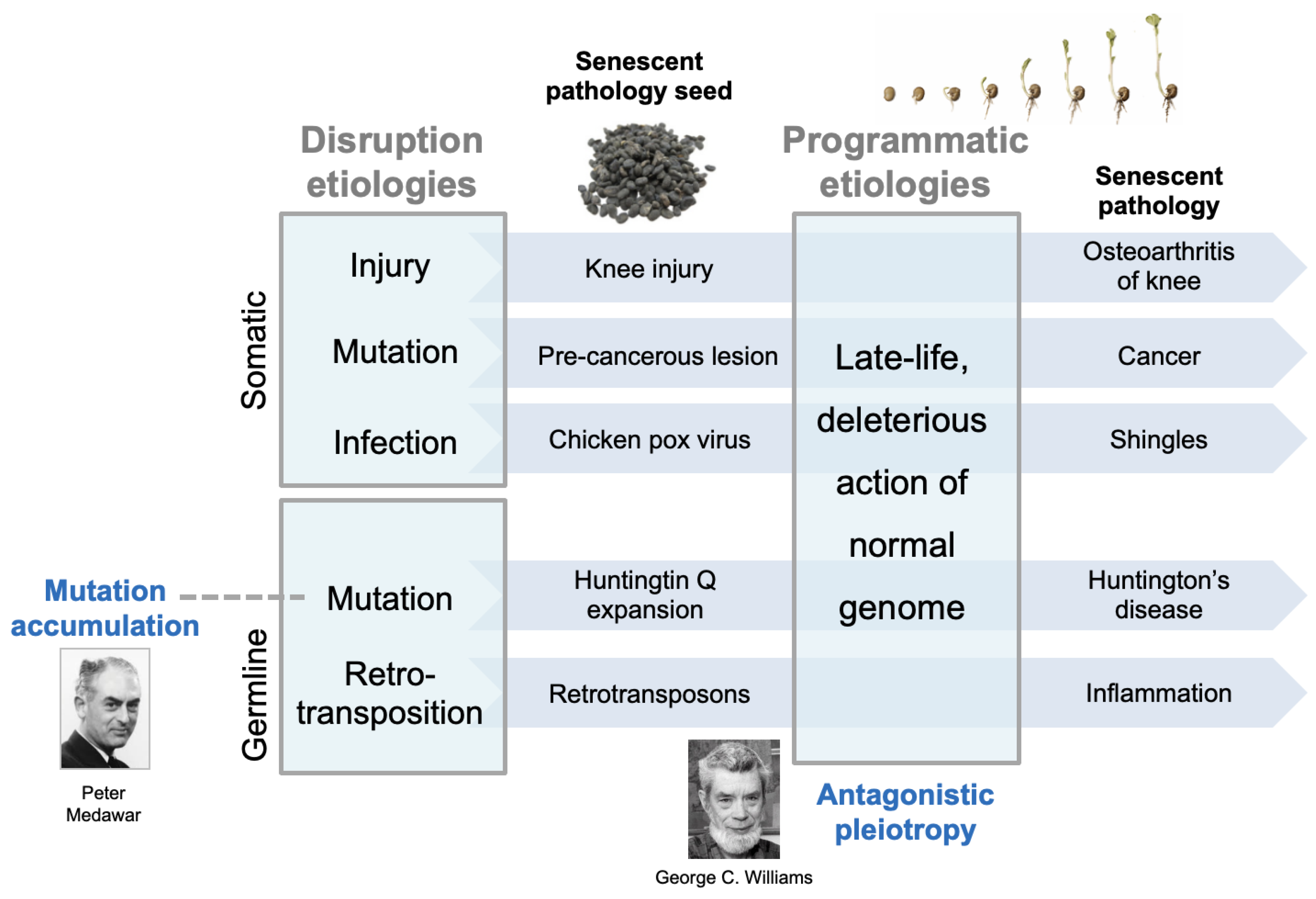

The Multifactorial Model

How Distinct Causes of Senescence Interact: A Two Stage Model

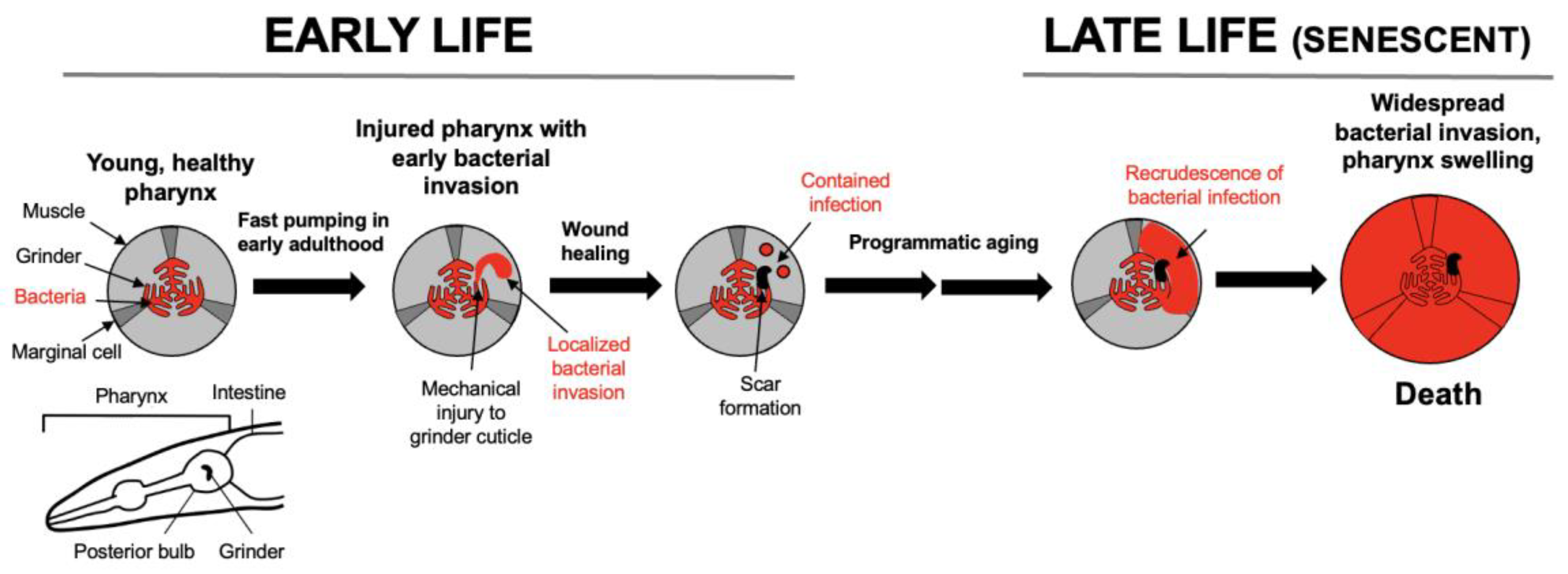

Origins of the Model: Senescence of the C. elegans Pharynx

Senescent Recrudescence of Early Life Infection

Early Mechanical Injury as a Focus for Late-Life Disease

Early Somatic Mutation and Late-Life Cancer

Inherited Mutations and Late-Life Disease

Retrotransposon Activation

Final Remarks

The Multifactorial Model is an Evolutionary Physiology Account

The Multifactorial Model and Anti-Aging Treatments

Acknowledgments

References

- Al Anouti, F.; Taha, Z.; Shamim, S.; Khalaf, K.; Al Kaabi, L.; Alsafar, H. An insight into the paradigms of osteoporosis: From genetics to biomechanics. Bone Rep. 2019, 11, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amole, M.; Khouzam-Skelton, N. Diagnosing post-polio syndrome in the elderly, a case report. Geriatrics 2017, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, P.; Doll, R. The age distribution of cancer and a multi-stage theory of carcinogenesis. Br J Cancer 1954, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.A. What causes Alzheimer's disease? Folia Neuropathol. 2013, 51, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.R.; Rose, M.R. Conceptual Breakthroughs in The Evolutionary Biology of Aging; Academic Press, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Austad, S.; Hoffman, J. Is antagonistic pleiotropy ubiquitous in aging biology? Evol Med Public Health 2018, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Wijers, M.E.; Sieben, C.J.; Zhong, J.; Saltness, R.A.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Verzosa, G.C.; Pezeshki, A.; Khazaie, K.; Miller, J.D.; van Deursen, J.M. Naturally occurring p16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 2016, 530, 184–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechah, Y.; Capo, C.; Mege, J.; Raoult, D. Epidemic typhus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008, 8, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. Aging and immortality: quasi-programmed senescence and its pharmacologic inhibition. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 2087–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. Paradoxes of aging. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 2997–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. Aging: ROS or TOR. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 3344–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. MTOR-driven quasi-programmed aging as a disposable soma theory: Blind watchmaker vs. intelligent designer. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 1842–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. From causes of aging to death from COVID-19. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 10004–10021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V.; Pardee, A.B. Conceptual biology: unearthing the gems. Nature 2002, 416, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J. Aging and cancer: the double-edged sword of replicative senescence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997, 45, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013, 75, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, B.G.; Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Conover, C.A.; Campisi, J.; van Deursen, J.M. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science 2016, 354, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouraki, V.; Seshadri, S. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Genet. 2014, 87, 245–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coggon, D.; Reading, I.; Croft, P.; McLaren, M.; Barrett, D.; Cooper, C. Knee osteoarthritis and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001, 25, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, A. The Biology of Senescence, Third edition ed.; Elsevier: New York, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.; Inskip, H.; Croft, P.; Campbell, L.; Smith, G.; McLaren, M.; Coggon, D. Individual risk factors for hip osteoarthritis: obesity, hip injury, and physical activity. Am J Epidemiol. 1998, 147, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppé, J.P.; Desprez, P.Y.; Krtolica, A.; Campisi, J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010, 5 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Lago, D.; Villa, G.; Miguoli, R.; Annoni, G.; Vergani, C. An unusual case of breast cancer relapse after 30 years of disease-free survival. Age Ageing 1998, 27, 649–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cecco, M.; Criscione, S.; Peckham, E.; Hillenmeyer, S.; Hamm, E.; Manivannan, J.; Peterson, A.; Kreiling, J.; Neretti, N.; Sedivy, J. Genomes of replicatively senescent cells undergo global epigenetic changes leading to gene silencing and activation of transposable elements. Aging Cell. 2013a, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cecco, M.; Criscione, S.; Peterson, A.; Neretti, N.; Sedivy, J.; Kreiling, J. Transposable elements become active and mobile in the genomes of aging mammalian somatic tissues. Aging 2013b, 5, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cecco, M.; Ito, T.; Petrashen, A.; Elias, A.; Skvir, N.; Criscione, S.; Caligiana, A.; Brocculi, G.; Adney, E.; Boeke, J.; Le, O.; Beauséjour, C.; Ambati, J.; Ambati, K.; Simon, M.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V.; Slagboom, P.; Helfand, S.; Neretti, N.; Sedivy, J. L1 drives IFN in senescent cells and promotes age-associated inflammation. Nature 2019, 566, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, A.; Gu, W.; Castoe, T.; Batzer, M.; Pollock, D. Repetitive elements may comprise over two-thirds of the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Guardia, Y.; Gilliat, A.F.; Hellberg, J.; Rennert, P.; Cabreiro, F.; Gems, D. Run-on of germline apoptosis promotes gonad senescence in C. elegans. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 39082–39096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Magalhães, J.P. Programmatic features of aging originating in development: aging mechanisms beyond molecular damage? FASEB J. 2012, 26, 4821–4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, J.P.; Church, G.M. Genomes optimize reproduction: aging as a consequence of the developmental program. Physiology 2005, 20, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, M.; Ohtani, N.; Youssef, S.A.; Rodier, F.; Toussaint, W.; Mitchell, J.R.; Laberge, R.M.; Vijg, J.; Van Steeg, H.; Dollé, M.E.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.; de Bruin, A.; Hara, E.; Campisi, J. An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev Cell. 2014, 31, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DePinho, R.A. The age of cancer. Nature 2000, 408, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz de Leon, A.; Cronkhite, J.; Katzenstein, A.; Godwin, J.; Raghu, G.; Glazer, C.; Rosenblatt, R.; Girod, C.; Garrity, E.; Xing, C.; Garcia, C. Telomere lengths, pulmonary fibrosis and telomerase (TERT) mutations. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilman, V.M. An integrated, four-component mechanism of aging, Development, Aging and Disease: A New Rationale for an Intervention Strategy; Harwood Academic Publishers, 1994; pp. 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Englund, M.; Lohmander, L. Risk factors for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis fifteen to twenty-two years after meniscectomy. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 2811–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faucher, J.-F.; Socolovschi, C.; Aubry, C.; Chirouze, C.; Hustache-Mathieu, L.; Raoult, D.; Hoen, B. Brill-Zinsser Disease in Moroccan Man, France, 2011. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2012, 18, 171–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatt, T.; Partridge, L. Horizons in the evolution of aging. BMC Biol. 2018, 16, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimov, E.R.; Gems, D. Shorter life and reduced fecundity can increase colony fitness in virtual C. elegans. Aging Cell. 2020, 19, e13141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimov, E.R.; Gems, D. Death happy: Adaptive death and its evolution by kin selection in organisms with colonial ecology. Philos Trans R Soc B 2021, 376, 20190730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gems, D. What is an anti-aging treatment? Exp Gerontol. 2014, 58, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gems, D. Understanding hyperfunction: an emerging paradigm for the biology of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2022, 74, 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gems, D. How aging causes osteoarthritis: an evolutionary physiology perspective. Annals Rheum Dis. 2025, 33, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gems, D. On Aging. What Causes It and How It Leads to the Maladies of Old Age; Columbia University Press, 2026. [Google Scholar]

- Gems, D.; de la Guardia, Y. Alternative perspectives on aging in C. elegans: reactive oxygen species or hyperfunction? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gems, D.; Doonan, R. Antioxidant defense and aging in C. elegans: is the oxidative damage theory of aging wrong? Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gems, D.; Kern, C.C. Is “cellular senescence” a misnomer? Geroscience 2022, 44, 2461–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gems, D.; Kern, C.C. Biological constraint, evolutionary spandrels and antagonistic pleiotropy. Ageing Res Rev. 2024, 101, 102527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gems, D.; Kern, C.C.; Nour, J.; Ezcurra, M. Reproductive suicide: similar mechanisms of aging in C. elegans and Pacific salmon. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 688788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glocker, M.O.; Guthke, R.; Kekow, J.; Thiesen, H.J. Rheumatoid arthritis, a complex multifactorial disease: on the way toward individualized medicine. Med Res Rev. 2006, 26, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glyn-Jones, S.; Palmer, A.J.; Agricola, R.; Price, A.J.; Vincent, T.L.; Weinans, H.; Carr, A.J. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2015, 386, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova, V.; Boeke, J.; Helfand, S.; Sedivy, J. Sleeping dogs of the genome. Science 2014, 346, 1187–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandison, R.C.; Piper, M.D.; Partridge, L. Amino-acid imbalance explains extension of lifespan by dietary restriction in Drosophila. Nature 2009, 462, 1061–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, J.B.S. New Paths in Genetics; Allen and Unwin: London, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, D.E.; Strong, R.; Sharp, Z.D.; Nelson, J.F.; Astle, C.M.; Flurkey, K.; Nadon, N.L.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Frenkel, K.; Carter, C.S.; Pahor, M.; Javors, M.A.; Fernandez, E.; Miller, R.A. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 2009, 460, 392–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, B. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part I. Caspian J Internal Med. 2011, 2, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Higashi, Y.; Gautam, S.; Delafontaine, P.; Sukhanov, S. IGF-1 and cardiovascular disease. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2019, 45, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisama, F.M.; Oshima, J.; Martin, G.M. How research on human progeroid and antigeroid syndromes can contribute to the longevity dividend initiative. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016, 6, a025882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochberg, N.; Horsburgh, C.J. Prevention of tuberculosis in older adults in the United States: obstacles and opportunities. Clin Infect Dis. 2013, 56, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope-Simpson, R.E. The nature of Herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965, 58, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, C.J.; O'Donnell, M.; Chamblee, S.; Moreland, J.; Johnson, J.; Marsh, B.; Narita, M.; Johnson, L.; von Reyn, C. Revisiting rates of reactivation tuberculosis a population-based approach. Am J Resp Critical Care Med. 2010, 182, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, A.; Palange, P. COPD: a multifactorial systemic disease. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2011, 5, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhakoski, R.; Heliövaara, M.; Impivaara, O.; Kröger, H.; Knekt, P.; Lauren, H.; Arokoski, J. Risk factors for the development of hip osteoarthritis: a population-based prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009, 48, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, J.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Lina, B.; Fuchs, F.; Foray, S.; Janatova, I.; Aymard, M.; Kopecka, H. Post-polio syndrome: poliovirus persistence is involved in the pathogenesis. J Neurol. 1999, 246, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.; Bennion, J.; Sorvillo, F.; Bellomy, A. Trends in tuberculosis mortality in the United States, 1990-2006: a population-based case-control study. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, C.C.; Srivastava, S.; Ezcurra, M.; Hsiung, K.C.; Hui, N.; Townsend, S.; Maczik, D.; Zhang, B.; Tse, V.; Kostantellos, V.; Bähler, J.; Gems, D. C. elegans ageing is accelerated by a self-destructive reproductive programme. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, C.C.; Townsend, S.; Salzmann, A.; Rendell, N.; Taylor, G.; Comisel, R.M.; Foukas, L.; Bähler, J.; Gems, D. C. elegans feed yolk to their young in a form of primitive lactation. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, T.B.L. Evolution of ageing. Nature 1977, 270, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, T.B.L.; Rose, M.R. Evolution of senescence: late survival sacrificed for reproduction. Phil Trans R Soc London 1991, 332, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kokjohn, T.; Maarouf, C.; Daugs, I.; Hunter, J.; Whiteside, C.; Malek-Ahmadi, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Kalback, W.; Jacobson, S.; Sabbagh, M.; Beach, T.; Roher, A. Neurochemical profile of dementia pugilistica. J Neurotrauma 2013, 30, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, J.; Wensink, M.; Rozing, M.; van Bodegom, D.; Westendorp, R. Intrinsic and extrinsic mortality reunited. Exp Gerontol. 2015, 67, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaître, J.-F.; Moorad, J.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Maklakov, A.A.; Nussey, D.H. From hallmarks of ageing to natural selection: A unified framework for genetic and physiological evolutionary theories of ageing. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohr, J.; Galimov, E.R.; Gems, D. Does senescence promote fitness in Caenorhabditis elegans by causing death? Ageing Res Rev. 2019, 50, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maklakov, A.A.; Chapman, T. Evolution of ageing as a tangle of trade-offs: energy versus function. Proc Biol Sci. 2019, 286, 20191604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikkavasagan, G.; Dezateux, C.; Wade, A.; Bedford, H. The epidemiology of chickenpox in UK 5-year olds: an analysis to inform vaccine policy. Vaccine 2010, 28, 7699–7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.C.; Robinson, M. Military-related traumatic brain injury and neurodegeneration. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014, 10, S242–S253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuiston, J.; Knights, E.; Demartino, P.; Paparello, S.; Nicholson, W.; Singleton, J.; Brown, C.; Massung, R.; Urbanowski, J. Brill-Zinsser disease in a patient following infection with sylvatic epidemic typhus associated with flying squirrels. Clin Infectious Diseases 2010, 51, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medawar, P.B. An Unsolved Problem Of Biology; H.K. Lewis: London, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, N.; Gilden, D.; Cohrs, R.; Mahalingam, R.; Nagel, M. Varicella zoster virus infection: clinical features, molecular pathogenesis of disease, and latency. Neurol Clin. 2008, 26, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesse, R.M.; Williams, G.C. Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine; Random House, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Niccoli, T.; Partridge, L. Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Curr Biol. 2012, 22, R741–R752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, A.; Nordström, P. Traumatic brain injury and the risk of dementia diagnosis: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS Medicine 2018, 15, e1002496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omalu, B.; DeKosky, S.; Hamilton, R.; Minster, R.; Kamboh, M.; Shakir, A.; Wecht, C. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a National Football League player: part II. Neurosurgery 2006, 59, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omalu, B.; DeKosky, S.; Minster, R.; Kamboh, M.; Hamilton, R.; Wecht, C. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a National Football League player. Neurosurgery 2005, 57, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvari, S.; Hamedi, S.; Mohammadianpanah, M.; Nasrolahi, H.; Mosalaei, A.; Talei, A.; Ahmadloo, N.; Ansari, M. Very Late Relapse in Breast Cancer Survivors: a Report of 6 Cases. Iranian J Cancer Prev. 2013, 6, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W.H. Varicella and herpes zoster vaccines: WHO position paper. Weekly Epidemiological Record 2016, 25, 265–288. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, M.; Behr, M.; Dowdy, D.; Dheda, K.; Divangahi, M.; Boehme, C.; Ginsberg, A.; Swaminathan, S.; Spigelman, M.; Getahun, H.; Menzies, D.; Raviglione, M. Tuberculosis. Nat Rev Disease Primers 2016, 2, 16076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, V.I.; Bokov, A.; Van Remmen, H.; Mele, J.; Ran, Q.; Ikeno, Y.; Richardson, A. Is the oxidative stress theory of aging dead? Biochim Biophys Acta 2009, 1790, 1005–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.R. Evolutionary Biology of Aging; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, S.; Lindquist, S. Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature 1998, 396, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, M.; White, T.; Iijima, K.; Haak, A.; Ligresti, G.; Atkinson, E.; Oberg, A.; Birch, J.; Salmonowicz, H.; Zhu, Y.; Mazula, D.; Brooks, R.; Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, H.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Prakash, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Robbins, P.; Aubry, M.; Passos, J.; Kirkland, J.; Tschumperlin, D.; Kita, H.; LeBrasseur, N. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 14532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmader, K.; George, L.; Burchett, B.; Pieper, C.; Hamilton, J. Racial differences in the occurrence of herpes zoster. J Infect Dis. 1995, 171, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharief, M.; Hentges, R.; Ciardi, M. Intrathecal immune response in patients with the post-polio syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991, 325, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, L.; Etheridge, T.; Szewczyk, N.L. Consolidating multiple evolutionary theories of ageing suggests a need for new approaches to study genetic contributions to ageing decline. Ageing Res Rev. 2024, 100, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, A.; Purgus, R.; Olmer, M.; Raoult, D. Brill-Zinsser disease in France. The Lancet 1999, 353, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullan, M.; Asken, B.; Jaffee, M.; DeKosky, S.; Bauer, R. Glymphatic system disruption as a mediator of brain trauma and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018, 84, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lee, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, T.; Lin, K.; Lin, C.; PN, W.; Tang, L.; Chiu, M. A nationwide survey of mild cognitive impairment and dementia, including very mild dementia, in Taiwan. PLoS One 2014, 9, e100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, M. Late recurrence of carcinoma of breast. BMJ 1960, 2, 1132–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivanen, A.; Heliövaara, M.; Impivaara, O.; Arokoski, J.; Knekt, P.; Lauren, H.; Kröger, H. Obesity, physically demanding work and traumatic knee injury are major risk factors for knee osteoarthritis--a population-based study with a follow-up of 22 years. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010, 49, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, J.M. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature 2014, 509, 439–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Meter, M.; Kashyap, M.; Rezazadeh, S.; Geneva, A.; Morello, T.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V. SIRT6 represses LINE1 retrotransposons by ribosylating KAP1 but this repression fails with stress and age. Nat Commun. 2014, 5, 5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ezcurra, M.; Benedetto, A.; Gilliat, A.; Hellberg, J.; Ren, Z.; Athigapanich, T.; Girstmair, J.; Telford, M.J.; Dolphin, C.T.; Zhang, Z.; Gems, D. A parthenogenetic quasi-program causes teratoma-like tumors during aging in wild-type C. elegans. NPJ Aging Mech Disease 2018, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiley, C.D.; Campisi, J. The metabolic roots of senescence: mechanisms and opportunities for intervention. Nat Metab. 2021, 3, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, J.E.; Burmeister, L.; Brooks, S.V.; Chan, C.C.; Friedline, S.; Harrison, D.E.; Hejtmancik, J.F.; Nadon, N.; Strong, R.; Wood, L.K.; Woodward, M.A.; Miller, R.A. Rapamycin slows aging in mice. Aging Cell. 2012, 11, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.C. Pleiotropy, natural selection and the evolution of senescence. Evolution 1957, 11, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, T.T.; Schmader, K. Herpes zoster in older adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001, 32, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngman, M.J.; Rogers, Z.N.; Kim, D.H. A decline in p38 MAPK signaling underlies immunosenescence in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajitschek, F.; Georgolopoulos, G.; Vourlou, A.; Ericsson, M.; Zajitschek, S.; Friberg, U.; Maklakov, A. Evolution under dietary restriction decouples survival from fecundity in Drosophila melanogaster females. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019, 74, 1542–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Promislow, D.E.L. Senescence and ageing. In The Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Medicine; Brüne, M., Schiefenhövel, W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 167–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Gilliat, A.F.; Ziehm, M.; Turmaine, M.; Wang, H.; Ezcurra, M.; Yang, C.; Phillips, G.; McBay, D.; Zhang, W.B.; Partridge, L.; Pincus, Z.; Gems, D. Two forms of death in aging Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 15458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Simon, M.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V. DNA damage and repair in age-related inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023, 23, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).