Introduction

Early proof-of-concept studies in healthy volunteers established that stimulating the calf can acutely boost venous return [

1]. NMES applied to the calf muscles produces immediate increases in popliteal and femoral vein blood flow [

2]. The NMES-induced contractions compress intramuscular veins, emulating the natural calf muscle pump [

3]. One report noted median popliteal velocities rising from ~7 cm/s at rest to ~70 cm/s with a voluntary calf contraction, and to ~13 cm/s with electrically induced contraction in standing subjects [

4]. Although voluntary effort generated the highest flow (since maximal effort can be greater than tolerable NMES intensity), NMES still produced a significant hemodynamic gain over resting conditions. Higher NMES currents recruit more muscle fibers, yielding greater venous outflow [

5]. Over a 30-minute NMES session, healthy subjects showed sustained venous ejection volumes, indicating no fatigue-induced drop-off in performance [

6]. In fact, as users habituated to the stimulation over days, they could comfortably tolerate higher intensities, leading to approximately double the venous ejected volume after one week of daily NMES compared to the first day [

6].

Interestingly, purely sensory stimulation (TENS) at low frequency can also trigger hemodynamic response, possibly via reflex pathways. For example, one crossover study in young healthy adults found popliteal vein time-averaged flow volume surged by over 220% above baseline with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) [

7]. In the same study, time-averaged flow volume in the popliteal vein rose ~37% with NMES. TENS and NMES both used symmetrical biphasic square waveforms with a 350 µs phase duration but differed in frequency – 5 Hz for TENS and 35 Hz for NMES – reflecting their distinct purposes, i.e., sensory stimulation for TENS and muscle stimulation for NMES. These findings confirm that even brief TENS/NMES bouts can eject a substantial volume of blood from the veins of the calf. Furthermore, this implies that muscle contractions are the primary drivers of venous return, though sensory nerve activation alone might induce calf muscle twitches or vasodilatory reflexes that aid flow.

Design innovations like textile electrodes (e.g. calf stimulation socks) aim to improve comfort further while maintaining efficacy [

8]. Modern NMES devices for healthy users (e.g. wearable integrated electrode garments) have been generally well tolerated. Within seconds of stimulation, the venous outflow from the calf is elevated, helping to empty the venous reservoir of the lower limb. These controlled lab findings laid the groundwork for therapeutic applications in clinical populations. An intriguing aspect of electrically induced peripheral exercise is its effect on central and cerebral circulation [

5]. Lower-limb NMES, by increasing venous return and cardiac preload, might influence cardiac output, blood pressure, and ultimately brain perfusion [

9]. Additionally, the absence of central command (since exercise is passive) can lead to unique autonomic and ventilatory responses (e.g. altered CO₂ levels) that impact cerebral blood flow (CBF). A 2021 study in Japan investigated CBF changes during NMES of large leg muscles [

9]. Using ultrasound flow measurements in major cerebral arteries, they found internal carotid artery (ICA) blood flow increased significantly by ~12% during calf/thigh NMES (from ~330 mL/min at rest to ~371 mL/min). In contrast, vertebral artery flow (posterior circulation) did not change appreciably. The rise in ICA flow suggests improved perfusion to anterior brain regions during NMES. Notably, there was a strong linear correlation between the increase in end-tidal CO₂ (a measure of carbon dioxide retention) and the increase in ICA flow during NMES (R=0.74). This implies the mechanism was partly CO₂-mediated cerebral vasodilation because the subjects were not volitionally exercising, their ventilation did not initially rise to offset increased CO₂ production by the stimulated muscles, leading to mild hypercapnia that dilated cerebral vessels. These findings show that NMES can enhance cerebral haemodynamics [

5], forming the rationale for the RETRAIN Phase 1 trial (NCT06614400).

Methodology

A. Study Design and Participants

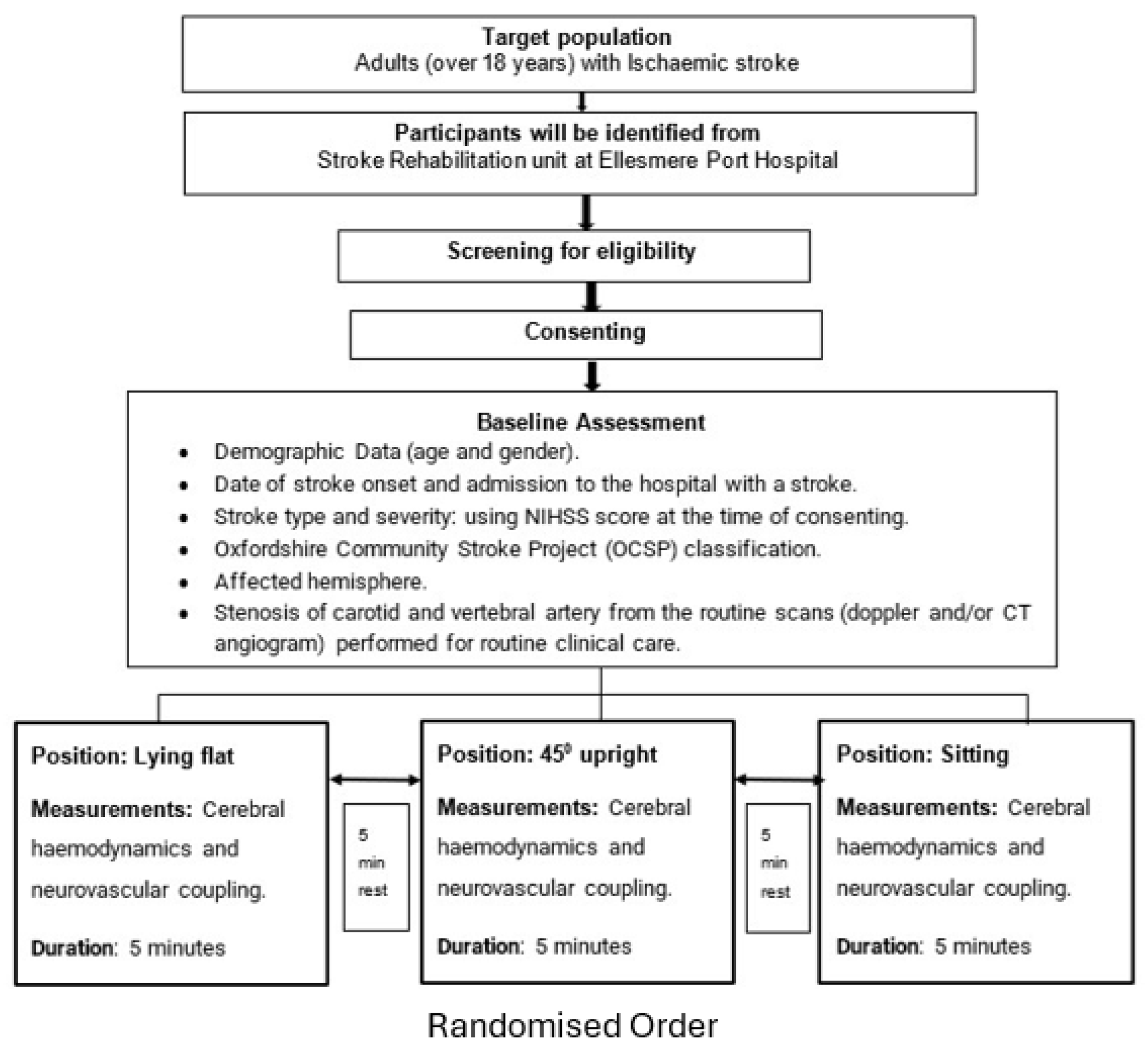

The RETRAIN Phase 1 trial (NCT06614400) was a single-centre, prospective observational study conducted at the Stroke Rehabilitation Unit, Ellesmere Port Hospital, Chester, UK – see

Figure 1. The protocol followed Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki, with ethical approval and informed consent obtained prior to enrolment. Eighteen adults (>18 years) in the subacute phase of ischemic stroke (>7 days post-onset) were recruited. Eligibility required the ability to assume three postures (supine, semi-supine at 45°, and upright sitting) and use of the geko™ NMES device as part of routine care. Exclusion criteria included recent stroke (<7 days), TIA, epilepsy, peripheral neuropathy, limb amputation, concurrent neuromodulatory device use, or inability to consent.

A. Experimental Procedures

Participants underwent baseline assessments including demographics, stroke severity (NIHSS), and vascular imaging. NMES was delivered bilaterally using the geko™ T-3 device to stimulate the common peroneal nerve across five stimulation levels (from three below to one above the clinical optimum). Each intensity was applied for 5 minutes across the three postures in randomized order, with 5-minute rest periods between conditions. fNIRS measurements were acquired using the NIRSport2 system (NIRx Medical Technologies, USA), with 16 sources and 16 detectors placed over the bilateral sensorimotor cortices. Probes were secured to optimize signal quality and minimize artifacts. Transcutaneous CO₂ was monitored using the Sentec Digital system, and other physiological parameters (blood pressure, room temperature) were controlled to reduce confounders.

A. Statistical Analysis

At the individual level, β-values were computed per channel and condition. Group-level analysis used mixed-effects models to account for subject variability and fixed effects (posture, stimulation intensity, lesion characteristics). Outlier subjects were excluded based on influence metrics. A multiple linear regression assessed the influence of clinical and experimental factors (e.g., lesion size, location, affected side, posture, stimulation level) on HbO β-values. ROI analysis was performed by grouping channels by hemisphere, followed by a two-way ANOVA on ROI and chromophore type (HbO vs. HbR). Topographical and statistical parametric maps were generated for spatial visualization of cortical activation, with false discovery rate correction (q < 0.05) applied for significance. We defined responders as the top quartile of HbO increases to capture the most robust and physiologically meaningful effects. This percentile-based approach reduces ambiguity in our small, heterogeneous cohort, avoids arbitrary cut-offs, and accounts for inter-individual variability in baseline hemodynamics. Clinical and demographic variables were extracted from structured electronic records and neuroimaging reports. Predictors included, Demographics: age, sex; Comorbidities: history of hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, cardiac failure, etc.; Stroke characteristics: lesion location, size, number, vascular territory; NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS): component and total scores; Systemic hemodynamics: posture-dependent systolic/diastolic blood pressure; Stimulation parameters: NMES intensity levels at each posture. Categorical variables were one-hot encoded; continuous variables were standardized (z-scored). Variables with >25% missingness were excluded. For the remaining data, missing values were imputed with zeros after standardization, where zero corresponds to the cohort mean. This approach treats missing values as average rather than extreme observations, helping to minimize bias in a small dataset. Each predictor’s univariate association with responder status was quantified using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, and area under the ROC curve (AUROC) was computed. Predictors with AUROC > 0.5 and adequate data coverage were retained for multivariate modeling. To develop a sparse, interpretable predictive model, we used logistic regression with L1 regularization (LASSO) on the preprocessed data matrix. Model training employed 10-fold cross-validation to select the optimal regularization parameter (λ) minimizing binomial deviance. The model’s out-of-sample performance was evaluated using AUROC. To assess predictor robustness, we performed permutation importance analysis. Each retained predictor was permuted 30 times, and AUROC drops relative to the baseline model were calculated. Greater AUROC loss indicated higher feature importance. For interpretability, odds ratios (OR) were computed by exponentiating the final LASSO coefficients (β) for all selected features. Final predictor importance was ranked using absolute β, permutation drop in AUROC, and univariate AUROC. All analyses were implemented in MATLAB R2024a (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

A. Safety and Ethics

Adverse events and device-related complications were closely monitored throughout the protocol. The study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (REC Ref: 343056), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Results

The final analytic sample included 18 stroke survivors (mean age: 76 ± 3 years; NIHSS mean: 4) monitored during NMES with concurrent fNIRS recordings. After filtering data completeness, 69 predictors were considered. Top-quartile increases in HbO served as the binary outcome for responder classification.

A. Cortical Hemodynamic Mapping

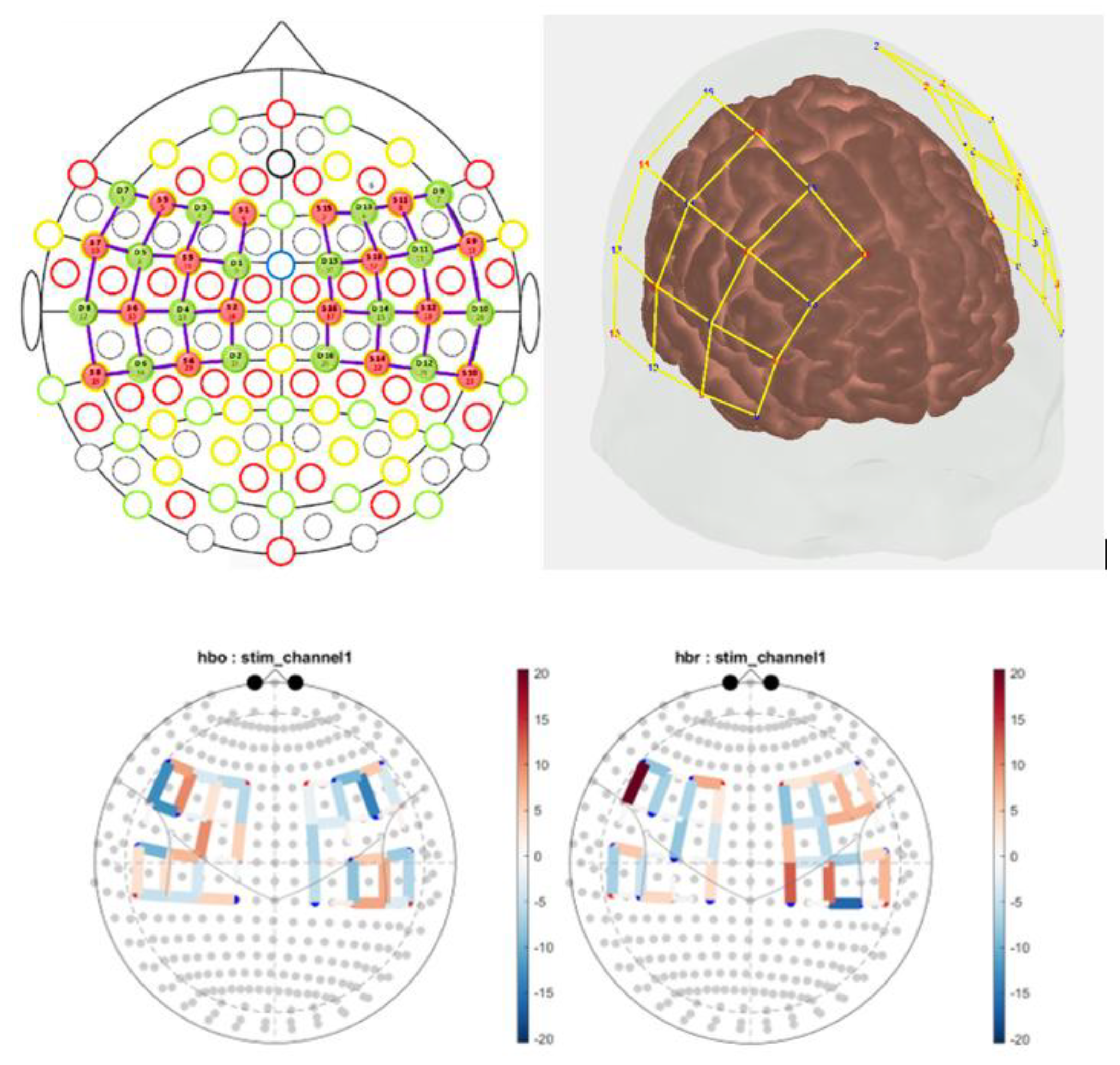

Figure 2 illustrates the fNIRS montage and statistical parametric maps. NMES stimulation produced significant cortical hemodynamic changes across bilateral sensorimotor regions with both increases and decreases observed in oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and deoxyhemoglobin (HbR) signals. These responses varied by stimulation intensity and posture as identified by group-level GLM with false discovery rate correction (q < 0.05).

A. Responder Analysis

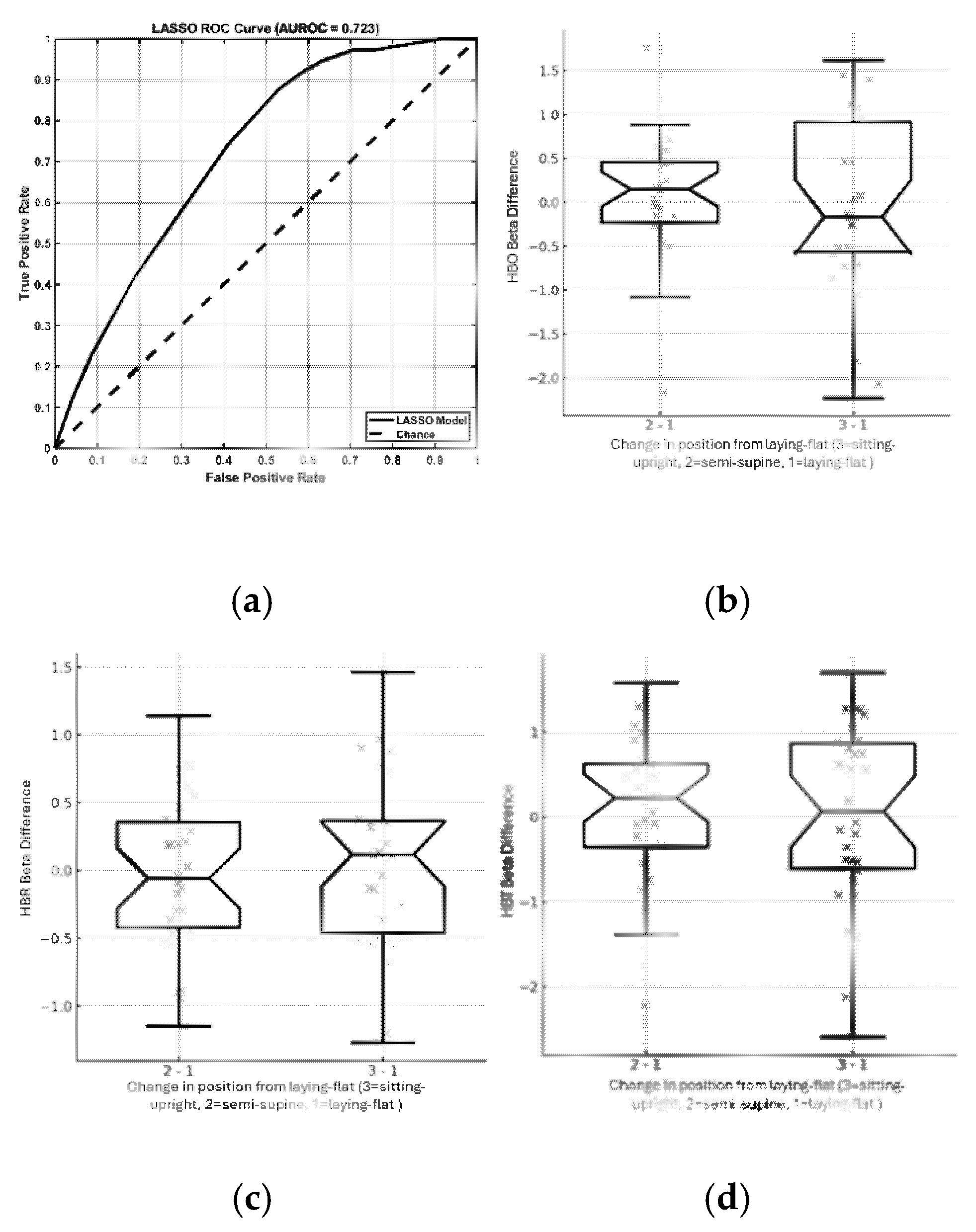

Initial AUROC-based screening revealed modest individual predictor performance (AUROC range: 0.50–0.62). Clinical history variables such as atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and stroke anatomical features such as lesion location and size showed mild to moderate predictive power. These variables were passed to the multivariate stage. The LASSO logistic regression model achieved a cross-validated AUROC of 0.723, indicating good discriminatory ability between responders and non-responders. The ROC curve demonstrated clear separation from chance, validating the utility of multi-feature modeling in this context. A total of 13 predictors were retained in the final model that included lesion characteristics (cortical location of main lesion, ASPECTS (affected = 0, unaffected = 1) left thalamus, ASPECTS right caudate), clinical history (history of Atrial Fibrillation, history of Hypertension), level of consciousness (item 1c of the NIH Stroke Scale i.e. patient’s ability to follow commands). The strongest effect was observed for cortical location of main lesion which had an odds ratio (OR) of 1.66 and the largest absolute β. This was followed by inverse associations for ASPECTS left thalamus (OR = 0.70) and ASPECTS right caudate (OR = 0.77), indicating lower likelihood of HbO response when those regions were unaffected. Permutation analysis confirmed feature robustness. The largest AUROC drops were observed upon permuting cortical location of main lesion (ΔAUROC = 0.064), ASPECTS left thalamus (ΔAUROC = 0.053), ASPECTS right caudate (ΔAUROC = 0.033). These features were thus identified as the most stable contributors to model prediction across resampling in noisy clinical data.

Figure 2.

Top Panels: 2D and 3D rendering of the fNIRS optode montage over the cortical surface, showing source (red) and detector (blue) positions connected by yellow lines, representing measurement channels over bilateral frontal and motor cortices. The montage is designed to capture cortical hemodynamic activity in regions relevant to motor and cognitive functions. Bottom Panel: Topographical statistical parametric maps showing NMES-evoked changes in oxyhemoglobin (hbo) and deoxyhemoglobin (hbr) concentrations from pre-stimulation baseline across the cortex with significance determined by a false discovery rate (q<0.05).

Figure 2.

Top Panels: 2D and 3D rendering of the fNIRS optode montage over the cortical surface, showing source (red) and detector (blue) positions connected by yellow lines, representing measurement channels over bilateral frontal and motor cortices. The montage is designed to capture cortical hemodynamic activity in regions relevant to motor and cognitive functions. Bottom Panel: Topographical statistical parametric maps showing NMES-evoked changes in oxyhemoglobin (hbo) and deoxyhemoglobin (hbr) concentrations from pre-stimulation baseline across the cortex with significance determined by a false discovery rate (q<0.05).

Figure 3a shows the ROC curve illustrating the performance of the LASSO classification model. The solid black line represents the model’s performance, plotting the True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) against the False Positive Rate across different classification thresholds. The dashed diagonal line indicates a random classifier (Chance line), representing an AUROC of 0.5. The LASSO model achieved an AUROC of 0.723, indicating a fair discriminative ability above random chance.

Figure 3b-d show that posture influenced NMES-evoked hemodynamic responses. Notched boxplots revealed posture-specific modulation in HbO, HbR, and HbT beta values. The semi-supine position produced the most consistent increases in HbT, suggesting enhanced cerebral blood volume possibly due to muscle-pump effects. Non-overlapping notches between postures indicated statistically significant median differences.

Discussion

This study identified and ranked predictors of cerebral hemodynamic responsiveness to common peroneal NMES in subacute stroke. Key predictors included lesion non-involvement of the left thalamus, right caudate, and overall cortical lesion location, supporting the role of subcortical structures in neurovascular regulation. Cardiovascular comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation (OR = 1.28) and hypertension also emerged as significant, consistent with their known effects on cerebrovascular function. Permutation analysis confirmed the robustness of these predictors. Some features with moderate univariate performance (e.g., lesion size, NIHSS 1c) gained relevance in the multivariate context, underscoring LASSO’s ability to reveal latent patterns. Therefore, by combining AUROC-based screening, LASSO regression, and permutation importance analysis, we developed a multivariate model (AUROC = 0.723) that outperformed individual predictors. While modest, this performance is consistent with early-phase exploratory studies and highlights the potential of multivariate modeling to capture latent patterns in small, heterogeneous cohorts. The strongest effect was observed for cortical lesions, where involvement of the cortex was associated with a 66% increased likelihood of HbO response (OR = 1.66), suggesting heightened neurovascular reactivity following injury. Also, infarction of the left thalamus (ASPECTS = 0) and right caudate (ASPECTS = 0) were associated with a higher likelihood of HbO response, as evidenced by odds ratios < 1 when these regions were unaffected (OR = 0.70 and OR = 0.77, respectively). These findings support the role of both structural lesions and vascular risk factors in modulating neurovascular reactivity after stroke [

11]. Importantly, our study extends prior NMES research by focusing not only on group-level hemodynamic effects but also on individual-level predictors of responsiveness that is a step toward clinical stratification with a model-based approach.

The use of fNIRS in this study enabled sensitive detection of regional hemodynamic changes, offering a non-invasive and portable tool to monitor neurovascular responses in bedside environments. The integration of real-time CO₂, temperature, monitoring further strengthened the reliability of hemodynamic interpretations by accounting for systemic confounders. Moreover, the rigorous statistical handling of artifacts and outliers using the NIRS Brain AnalyzIR Toolbox ensured the robustness of group-level inferences [

10]. Positive beta coefficient changes in HBO indicate enhanced cerebral oxygen delivery, whereas negative values signal relative hypoperfusion. HBR behaves inversely, i.e., a fall in HBR accompanies improved oxygenation, while elevations suggest transient desaturation under constant CBF. The heterogeneous response patterns observed are consistent with stroke-related neural plasticity and perfusion dynamics [

12]. A novel contribution of this study is the demonstration of posture as a physiological modulator i.e. the semi-supine position yielded the most consistent increases in cerebral blood volume, suggesting NMES may counteract venous pooling and optimize cerebral perfusion under orthostatic stress. This aligns with established principles of cardiovascular physiology [

13,

14] and has direct clinical relevance for tailoring NMES protocols for rehabilitation [

15].

For clinical translation in heterogeneous stroke pathophysiology, including stroke–heart syndrome [

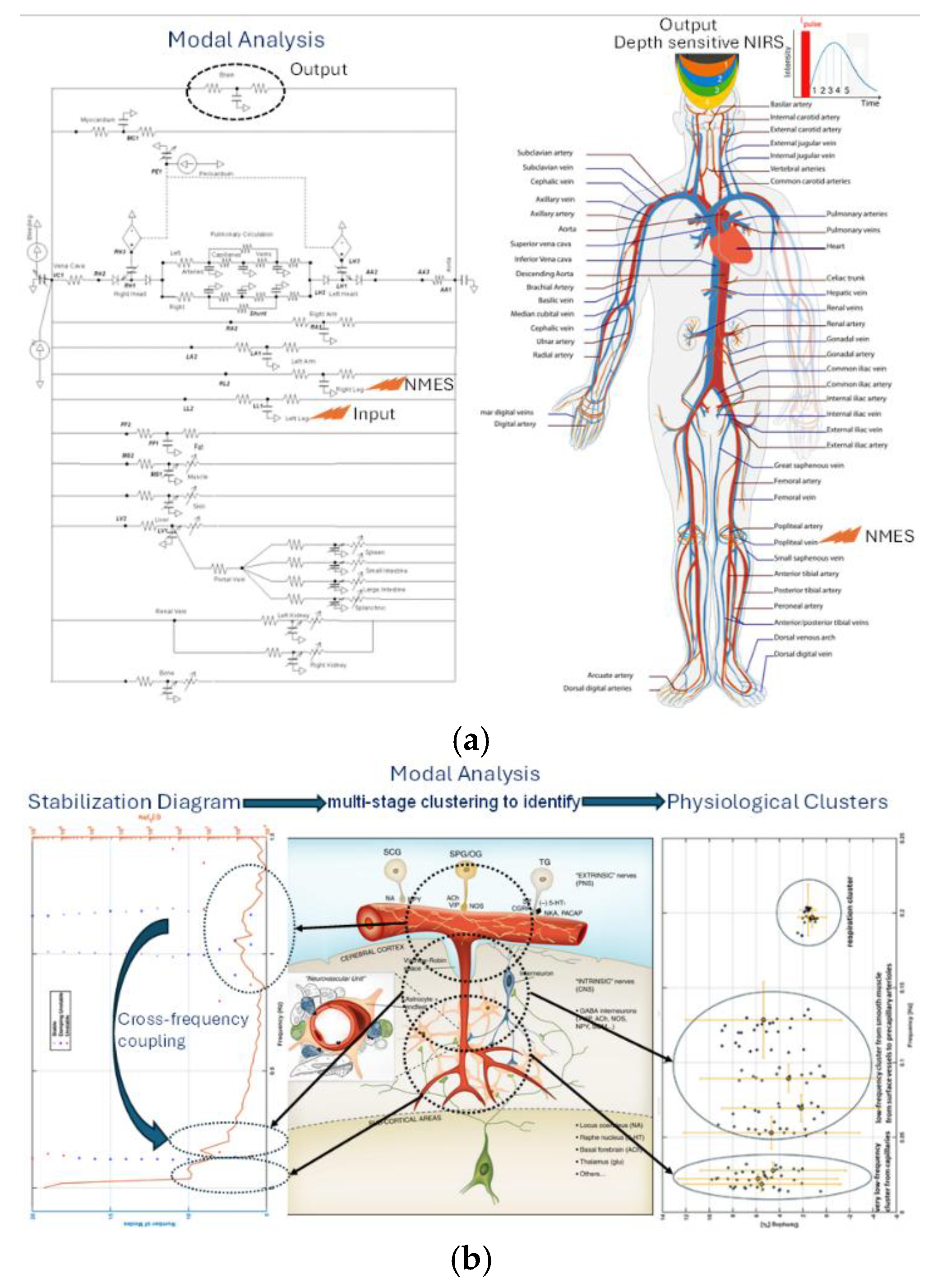

16], we now apply model-based approach to integrate heart–lung–brain dynamics with real-time muscle [

15] and cerebral NIRS monitoring to optimize NMES dosing [20] – see

Figure 4. An AI-enabled framework can tailor NMES for stroke patients by integrating real-time brain monitoring with physiological modeling. Time-domain NIRS provides depth-resolved signals from cortical and subcortical vessels, while simulations such as the Pulse Physiology Engine model how NMES influences systemic and cerebral circulation. These tools, combined with signal decomposition methods that separate systemic from cerebral effects, support closed-loop systems that automatically adjust NMES settings based on patient-specific vascular responses. This approach enables adaptive, data-driven protocols designed to enhance cerebral perfusion and support recovery.

Prior works on NMES has shown promising evidence to enhance peripheral and cerebral hemodynamics, particularly through its effects on the calf muscle pump – see

Table 1. Computational modelling has been instrumental in reinforcing these findings [

17],[

3], demonstrating how NMES interacts with venous valves and systemic blood pressure. Models confirm that effective venous return hinges on both adequate muscle contraction and valve competence, especially in upright positions or in individuals with venous disease [

18]. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 4, depth-resolved tracking of hemodynamic signals enables monitoring of pial and cortical microvessels, which are differentially regulated with surface vessels primarily by peripheral nerves and deeper microvessels by central pathways within the neurovascular unit [

19].

Our study has several limitations. The small sample size and observational design limit generalizability, and mean imputation of missing values may underestimate variability. The lack of sham control prevents exclusion of placebo effects, and fNIRS does not capture deeper brain regions. Although no serious adverse effects occurred, future trials should systematically report tolerability and potential risks such as discomfort, skin irritation, or autonomic changes, given the geko™ NMES device was originally designed for venous thromboembolism prevention. Finally, while our AUROC of 0.723 indicates fair discrimination, larger studies with external validation and functional outcome measures are needed to refine and validate predictive models.

Table 1.

Impact of NMES on internal carotid artery (ICA), vertebral artery (VA), and global cerebral perfusion [

9].

Table 1.

Impact of NMES on internal carotid artery (ICA), vertebral artery (VA), and global cerebral perfusion [

9].

| Measure |

NMES Effect |

Interpretation |

| ICA Blood Flow |

↑ from 330 to 371 mL/min (p = 0.001) |

NMES increases internal carotid artery perfusion, contributing to enhanced cerebral oxygen delivery. |

| ICA Diameter |

↑ from 0.48 to 0.50 mm (p = 0.049) |

Suggests vasodilation in response to metabolic/pressure changes. |

| ICA Cerebrovascular Conductance |

Slight ↑ (p = 0.005) |

Reflects improved vascular efficiency in response to NMES. |

| VA Blood Flow and Diameter |

No significant change |

Indicates NMES preferentially affects anterior circulation. |

| Global Cerebral Blood Flow |

↑ from 910 to 1,002 mL/min (p < 0.001) |

Major finding: NMES significantly enhances global brain perfusion. |

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides preliminary evidence that common peroneal NMES can enhance cerebral perfusion in subacute stroke, with responsiveness influenced by lesion characteristics, cardiovascular comorbidities, and body posture. By integrating clinical and imaging predictors through an interpretable machine learning framework, we move beyond prior work that focused only on group-level hemodynamic effects. These findings suggest NMES may be particularly valuable for patients unable to exercise, as benefits appear to arise from combined calf muscle pump activity, autonomic reflexes, and gas exchange. While mechanistic modeling indicates that venous valve integrity and vascular pathways modulate these effects, validation in larger, controlled trials is needed. Future studies should confirm predictive markers, systematically assess safety and tolerability, and evaluate whether stratified NMES protocols can translate into improved functional outcomes.

CRediT Author Contributions

Kausik Chatterjee, MD: Clinical Supervision, Investigation, Resources, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing. Sandra Leason: Data Curation, Investigation, Project Administration. Allam Harfoush, MD: Investigation. Yashika Arora, PhD: Methodology. Anirban Dutta, PhD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- M. D. Laverick, R. C. McGivern, M. D. Crone, and R. A. B. Mollan, ‘A Comparison of the Effects of Electrical Calf Muscle Stimulation and the Venous Foot Pump on Venous Blood Flow in the Lower Leg’, Phlebology, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 285–290, Dec. 1990. [CrossRef]

- M. Ojima, R. Takegawa, T. Hirose, M. Ohnishi, T. Shiozaki, and T. Shimazu, ‘Hemodynamic effects of electrical muscle stimulation in the prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis for intensive care unit patients: a randomized trial’, J Intensive Care, vol. 5, p. 9, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- ‘Hemodynamics Due to Calf Muscle Activity – Biophysical Modeling and Experiments Using Frequency Domain Near Infrared Spectroscopy in Healthy Humans - ProQuest’. Accessed: Apr. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2057213070/abstract/A0B18FA2CF14415DPQ/1.

- M. Clarke Moloney, G. M. Lyons, P. Breen, P. E. Burke, and P. A. Grace, ‘Haemodynamic study examining the response of venous blood flow to electrical stimulation of the gastrocnemius muscle in patients with chronic venous disease’, Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 300–305, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. Dutta, F. Zhao, M. Cheung, A. Das, M. Tomita, and K. Chatterjee, ‘Cerebral and muscle near-infrared spectroscopy during lower-limb muscle activity - volitional and neuromuscular electrical stimulation’, Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc, vol. 2021, pp. 6577–6580, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Corley, P. P. Breen, S. I. Bîrlea, J. M. Serrador, P. A. Grace, and G. Ólaighin, ‘Hemodynamic effects of habituation to a week-long program of neuromuscular electrical stimulation’, Med Eng Phys, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 459–465, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- F. Senin-Camargo, A. Martínez-Rodríguez, M. Chouza-Insua, I. Raposo-Vidal, and M. A. Jácome, ‘Effects on venous flow of transcutaneous electrical stimulation, neuromuscular stimulation, and sham stimulation on soleus muscle: A randomized crossover study in healthy subjects’, Medicine, vol. 101, no. 35, p. e30121, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Juthberg et al., ‘Electrically induced hemodynamic enhancement via sock-integrated electrodes is more comfortable and efficient at 1 hz as compared to 36 hz’, Sci Rep, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 12944, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Ando et al., ‘Effects of electrical muscle stimulation on cerebral blood flow’, BMC Neurosci, vol. 22, p. 67, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Santosa, X. Zhai, F. Fishburn, and T. Huppert, ‘The NIRS Brain AnalyzIR Toolbox’, Algorithms, vol. 11, no. 5, Art. no. 5, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. B. G. van Wijngaarden, R. Zucca, S. Finnigan, and P. F. M. J. Verschure, ‘The Impact of Cortical Lesions on Thalamo-Cortical Network Dynamics after Acute Ischaemic Stroke: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study’, PLOS Computational Biology, vol. 12, no. 8, p. e1005048, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Cramer, ‘Repairing the human brain after stroke: I. Mechanisms of spontaneous recovery’, Ann Neurol, vol. 63, no. 3, pp. 272–287, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Rickards and Y.-C. Tzeng, ‘Arterial pressure and cerebral blood flow variability: friend or foe? A review’, Front Physiol, vol. 5, p. 120, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Van Lieshout, W. Wieling, J. M. Karemaker, and N. H. Secher, ‘Syncope, cerebral perfusion, and oxygenation’, J Appl Physiol (1985), vol. 94, no. 3, pp. 833–848, Mar. 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. Cheung, ‘Hemodynamics Due to Calf Muscle Activity – Biophysical Modeling and Experiments Using Frequency Domain Near Infrared Spectroscopy in Healthy Humans’, M.S., State University of New York at Buffalo, United States -- New York. Accessed: Sep. 28, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://www.proquest.com/docview/2057213070/abstract/A0B18FA2CF14415DPQ/1.

- J. F. Scheitz, L. A. Sposato, J. Schulz-Menger, C. H. Nolte, J. Backs, and M. Endres, ‘Stroke-Heart Syndrome: Recent Advances and Challenges’, J Am Heart Assoc, vol. 11, no. 17, p. e026528, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. M. T. Keijsers, C. A. D. Leguy, W. Huberts, A. J. Narracott, J. Rittweger, and F. N. van de Vosse, ‘A 1D pulse wave propagation model of the hemodynamics of calf muscle pump’, International Journal for Numerical Methods in Biomedical Engineering, vol. 31, no. 7, pp. 1–20, 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. Niccolini et al., ‘Possible Assessment of Calf Venous Pump Efficiency by Computational Fluid Dynamics Approach’, Front Physiol, vol. 11, p. 1003, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhao, M. Tomita, and A. Dutta, ‘Portable Neuroimaging-Based Digital Twin Model for Individualized Interventions in Type 2 Diabetes’, in Technology Innovation for Sustainable Development of Healthcare and Disaster Management, P. K. Ray, R. Shaw, Y. Soshino, A. Dutta, and T. A. Geumpana, Eds., Singapore: Springer Nature, 2024, pp. 295–313. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).