Introduction

The 1987 Brundtland Report of the United Nations defined sustainable development as meeting the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs [1]. This concept is far from selfish; it is a way of life that shows future generations that dreams can be achieved. The Brundtland Report highlighted the connection between humanity’s hopes for a better life and the limits set by nature. Over time, the idea has been redefined to include the three pillars of sustainability: social, economic, and environmental [3]. The concept of community plays a vital role in this transition, where all parties are encouraged to collaborate [4]. In recent years, awareness of sustainability issues has increased, as sustainability encompasses various aspects of resource use and society [5, 6].

The sustainability of cities has become essential in addressing environmental, social, and economic challenges, especially as it is projected that 60% of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050 [7]. Cities are the center of human activity, and most environmental degradation and consumption are focused within urban areas [8]. Despite this, cities and their residents can play a vital role in achieving global sustainability [9]. This argument is based on the idea that sustainable development mainly focuses on the relationship between human activity and the environment [10].

Over the last century, theories of modern urban planning have been developed, with most references pointing to Howard’s “Garden City” theory in 1898 as the beginning of the contemporary and sustainable urban planning concept. Howard criticized Britain’s crowded industrial cities and proposed the “Garden City,” which can combine the best features of town and country living, promote community and social interaction, enhance environmental sustainability, and provide economic opportunity. It also emphasized the spatial arrangements and components of cities and towns, such as housing units and neighborhood facilities, for the first time [11]. In 1929, American urban planner Clarence Perry built on Howard’s theory to develop his neighborhood concept. The theory highlighted the importance of central services, accessibility, and the need for key community amenities like schools to be located at the center of neighborhoods. Furthermore, Clarence focused on the social pillar and social interaction among community members. His theory argued that the user experience is influenced by the quality of life in the neighborhood and the surrounding environment. Clarence greatly affected the livability of communities after cars started to dominate urban areas, leading to many changes in social dynamics [12].

One of the most crucial parts of a city is the neighborhood, the most livable area where residents spend most of their time building social connections, which help create more livable cities [13]. It is no longer surprising that planners and decision-makers increasingly recognize neighborhoods as the fundamental units of cities and the closest environmental, social, and economic contexts to residents, where sustainability can be effectively assessed [8]. The neighborhood scale is the fundamental unit of urban development [14] and the minimum criteria for assessing social, economic, and institutional sustainability aspects [8, 15]. The concept of sustainability at the neighborhood level can be seen as a process where successes become visible parts of daily life [16]. This idea is valuable because it highlights citizens’ daily efforts to promote sustainability rather than relying on centralized institutions [17].

Social and economic sustainability go beyond just survival. Neighborhoods should be developed to enhance residents’ social and economic well-being and be enjoyable places to live, work, or visit. This is essential for a neighborhood to be truly sustainable. Popular destinations attract people and investment, and are continually revitalized [18]. Social sustainability is meeting essential needs, building social capital, and preserving community characteristics while promoting social justice and equality [19]. Economic sustainability is defined “as a state of a society, economy, and environment that implies minimal risks for the long-term development of a city,” which develops a conceptual framework to view economic sustainability as a multifaceted phenomenon that reflects the city’s economic growth, ensuring that the potential of future generations is not harmed and the rights of current residents are protected [20, 21].

Although neighborhood planning has a relatively long history, planners and environmentalists did not begin to design tools for sustainability assessment at the neighborhood scale until the beginning of the 21st century [22]. The rapid expansion of cities, environmental concerns, and the need for sustainable neighborhoods have led to Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment Tools (NSATs) like LEED-ND and BREEAM-Communities [23]. The NSAT considered for this study is the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM), developed in 1990 by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) in the United Kingdom. BREEAM is the world’s first and leading sustainability assessment and certification scheme for the built environment. It aims to inspire and motivate change by rewarding and encouraging sustainability throughout the life cycle of master-planning projects, infrastructure, and buildings. It evaluates, promotes, and rewards environmental, social, and economic sustainability within the built environment [24].

NSATs are tools designed to assess a neighborhood’s progress toward sustainability goals [25]. NSATs cannot fully address multiple aspects of sustainability, mainly social and economic factors. This may reinforce the idea that sustainability is achieved by focusing only on specific areas instead of considering the complex relationships between building and urban environments. This encourages reconsidering the spatial boundaries of the impact of sustainable neighborhoods. Many researchers have found that social and economic impact studies can help urban planners and decision-makers make better choices that benefit society [27, 28]. As mentioned earlier, sustainability is not selfish, so it is crucial to analyze how a sustainable neighborhood can impact social and economic aspects of the surrounding area, especially for a certified neighborhood with defined boundaries, which this study aims to investigate, particularly since NSAT does not examine this impact.

Literature Review

Hubbard 1995 pointed out that improved urban design can help promote local economic growth. Rethinking how urban design supports economic recovery is essential. While urban design policies can stimulate the local economy, they may also overlook urgent social issues [29]. French and others 2014 highlighted the importance of urban design in promoting social engagement [30]. Forrest and Kearns 2001 observed a renewed focus on local social relations, especially those related to social capital. They emphasized that neighborhoods have become vital for many processes that shape social identity and life opportunities. They argued that societies face a new crisis in social cohesion and identified its main aspects. Additionally, they explored how modern residential neighborhoods connect to broader discussions about social capital, particularly the link between social cohesion and social capital. Furthermore, they demonstrated how social capital can be divided into key areas for policy action at the neighborhood level. They discussed ways to implement social cohesion and social capital in research [31].

Leyden 2003 studied the relationship between neighborhood design and individual social capital levels. Data were collected from a household survey that measured residents’ social capital in areas ranging from traditional, mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly layouts to modern, car-oriented suburban neighborhoods in Galway, Ireland. The analysis indicates that people living in walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods generally have higher social capital than those in car-oriented suburbs. Respondents in walkable areas were more likely to know their neighbors, participate in politics, trust others, and engage socially. Walkable, mixed-use neighborhood designs can help foster the development of social capital [32]. Neighborhood studies have drawn researchers from various perspectives. Choguill 2008 argued that a city could not be sustainable if its neighborhood, one of its most essential components, is not sustainable. Choguill aimed to develop criteria to assess neighborhood sustainability and explore the concept of sustainability in neighborhood development. He identified previous criteria used to measure neighborhood sustainability and then listed characteristics that define sustainable neighborhoods, including walkability, proximity to services, availability of parks and green spaces, community centers, mixed density, and mixed-use buildings. The study emphasized that neighborhood planning theories have been developed over the years to achieve sustainability [33].

Dempsey, Brown, and Bramley 2012 examined the connection between elements of urban form, including density, and sustainability, focusing on social sustainability aspects such as social equity (access to services and facilities), environmental equity (access to green and open spaces), and community sustainability (perceptions of safety, social interaction, and stability). They explore the idea that high-density neighborhoods are less likely to support socially sustainable behaviors and attitudes than low-density areas. They demonstrate how various neighborhood elements, both physical and non-physical, are interconnected. For example, design, maintenance, and safety are all related. People engage socially in their local neighborhood when there are valid reasons, often provided by accessible services and facilities that can be safely and comfortably reached on foot. They conclude that the compact city model offers multiple sustainability benefits; however, its impact on social sustainability is not entirely positive. Furthermore, several questions about its applicability and replicability remain in a highly globalized and urbanized world. They also highlight that privacy is important at home and in public spaces, helping users feel safe and comfortable [34].

Silvestre and Ţîrcă 2019 explored various innovations for sustainable development (SD) in the literature. They emphasize the need for further research to understand how different types of innovations (e.g., traditional, green, social, and sustainable) and their focus areas (e.g., technology, management, and policy) affect the four TCOS innovation uncertainties (e.g., technological, commercial, organizational, and societal). This offers practical insights into reducing or eliminating uncertainties based on the specific type and focus of an innovation for SD. The reviewed literature addresses urgent environmental and social issues, and its findings, recommendations, and contributions are promising for advancing toward a sustainable society through innovation and change. This helps develop a clearer understanding of the most relevant innovations, supporting research and practice in tackling society’s critical sustainability challenges [35].

Akbar and others 2019 conducted an analytical study to develop historical land use and land cover (LULC) maps covering 1988–2016 for spatial and temporal analysis. They projected future LULC up to 2040 using remote sensing satellite data and a Markov model, while also examining how LULC changes impacted urbanization and the economy in Lahore, Pakistan. The study revealed significant land cover changes in Lahore, with most areas transforming into built-up urban land. These changes notably improved residents’ living standards and influenced the real estate market. Many barren lands were developed into housing societies, commercial buildings, and industrial zones, driving urbanization and industrial growth. Additionally, these transformations promoted population growth through migration from neighboring regions, increasing pressure on natural resources such as land and water, and creating new challenges for sustainable development. The literature highlights a positive relationship between urbanization, building increase, and economic growth by creating more commercial spaces [36].

Eriksson and others in 2021 state that sociodemographic factors influence social capital at the neighborhood level. Policies should promote mixed sociodemographic groups to strengthen social capital for sustainable social development. Encouraging community engagement by creating meeting places and improving access to shops, cafés, and restaurants can boost social interactions and neighborhood satisfaction [37]. Stessens, Canters, and Khan 2021 argue that green spaces positively impact human well-being, and non-affluent neighborhoods are generally underserved regarding green space availability [38]. Guinaudeau and others 2023 and Inançoglu and others 2023 state that urban green and blue spaces contribute to human health benefits and play a crucial role in maintaining cities’ quality of life and sustainability [39, 40].

Chiaradia and others 2024 state that strong cultural and public services, public spaces, and small retail shops characterize urban areas with higher levels of walking and cycling. Their walkability and diverse amenities foster lively street life and frequent social interactions, enabling residents to enjoy their preferred lifestyles. These areas typically attract wealthier, more educated residents who can afford higher housing costs to access public services, cultural attractions, shops, and infrastructure [41]. Al-Zghoul and Al-Homoud emphasize that walkable environments improve mobility and play a key role in fostering social cohesion and interaction [42]. Orlandi and others state that community engagement and resilience in public spaces indicate that users feel safe and secure [43]. Positive social impacts highlight opportunities to enhance human well-being and provide a broad view of a product’s overall social impact. The literature indicates that standards for defining positive impacts and methods for assessing them are still evolving and have gaps [44].

Despite extensive studies on sustainable neighborhoods that various NSATs can evaluate, a gap remains in understanding and examining their social and economic impacts on surrounding areas. Furthermore, there is limited research on the social and economic impacts of sustainable neighborhoods in the Sultanate of Oman; however, two certified neighborhoods are in Muscat. Therefore, this study addresses these gaps by analyzing and identifying certified sustainable neighborhoods’ social and economic impacts on the surrounding area. This will assist urban planners and decision-makers in making better choices that benefit society and promote sustainable development.

Methodology

This study investigates the social and economic impacts of certified sustainable neighborhoods, specifically “Al-Mouj Muscat,” on the nearby urban area “Al-Mawaleh North.” It highlights key factors and how sustainable practices influence economic growth, social dynamics, and community well-being. A research question has been formulated: How do sustainable neighborhoods impact the social and economic development of surrounding urban areas? Several objectives are outlined to address this, including analyzing land use and land cover in the Al-Mawaleh North district—the nearest urban area to the sustainable neighborhood Al-Mouj—over 15 years; evaluating the social and economic impacts on the nearby urban area of the certified sustainable neighborhood Al-Mouj; exploring residents’ perceptions and opinions about Al-Mouj’s impact on quality of life, community engagement, and social networks; and investigating changes in property values, local business performance, and the growth of surrounding businesses around Al-Mouj. A mixed-methods approach combining quantitative and qualitative methods has been employed to achieve the research aim and objectives and address the research question. This approach enables understanding local conditions and variation, leading to more reliable urban planning interventions [42]. The research utilized four data collection methods: literature review, case study, questionnaire, and interviews, resulting in 515 responses—511 from the questionnaire and 4 from interviews. The data collected were analyzed geographically using ArcGIS, statistically with SPSS, and thematically with NVivo.

The literature review shows no specific criteria have been tested to accurately measure a sustainable neighborhood’s social and economic impact. However, it also indicates a consensus that social impact can be assessed by examining sustainable features, inclusive communities, social cohesion, quality of life, well-being, and mental and physical health. Economic impact can be measured by analyzing effects on the local economy, job opportunities, investments, land use development, and the real estate market. Therefore, these are the chosen criteria to be tested in this study through land use and land cover analysis, the questionnaire, and interviews.

This study employed ethnographic methods to maximize data collection from open-ended questions in the questionnaire and interview. These methods helped identify the research problem, formulate questions for the questionnaire and interview, collect data, write memos with initial coding into categories, develop detailed memos, refine categories, create diagrams of concepts, and document the findings [45]. They also facilitated collecting participants’ observations, reflecting on them, and developing insights into the social and economic impacts of the sustainable neighborhood on the surrounding area. Additionally, this approach allowed the study to provide researchers and stakeholders with reliable indicators to evaluate this impact in other case studies and guided their decision-making.

Case Study

The selected case study is Al-Mawaleh North district in Muscat Governorate, Oman, as shown in

Figure 1a. It was selected because it is a nearby district within 3 km of Al-Mouj, as shown in

Figure 1b, to investigate the social and economic impact of sustainable neighborhoods on the surrounding urban area. Al-Mouj Muscat is recognized as Oman’s first certified sustainable neighborhood. It received two BREEAM Communities certificates for the master planning of a larger community of buildings, with a Pass and a Very Good rating for Golf Beach Residences—a collection of luxury family homes on the oceanfront [46]. Golf Beach Residences includes 51 apartments and villas within private gated communities. While designs vary, all are built to the highest standards using premium materials, focusing on long-term energy efficiency, health, and well-being. Residents’ living environments help protect the broader environment by reducing energy consumption and CO2 emissions. Al-Mouj also lowers owners’ operating costs through smart energy management systems and innovative architectural design. Alongside the ocean and 6 km of beaches, there are tree-lined walkways, nine landscaped parks with eight kids’ play areas, and 1.5 km of cycle paths—providing opportunities to enjoy the outdoors and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Al-Mouj includes 8,000 residential properties and over 19,000 residents from 85 different countries. It also attracts visitors to its boulevard-style, world-class retail, dining, and entertainment venues, including a 400-berth marina and an award-winning golf course [47].

Al-Mouj is Oman’s first Integrated Tourism Complex (ITC) project, which began construction in 2007 and was 75% complete by 2020 [48]. Aiming to promote economic diversification, encourage tourism growth and employment, and create opportunities for enterprise and investment, in line with Oman Vision 2040. Therefore, the project is designed to be Oman’s leading lifestyle and leisure destination, attracting people from different backgrounds, cultures, and industries to connect and thrive within a balanced community. Additionally, this community plans to integrate facilities and services seamlessly to ensure a sustainable and livable environment. The Royal Decree issued in 2006 permits foreigners to own real estate within Integrated Tourism Complexes (ITCs) like Al-Mouj, granting them freehold ownership rights. They can apply for long-term residency for themselves and their immediate family if they continue to own property [49].

Land Use and Land Cover

A spatial analysis of land use and land cover change in Al-Mawaleh North is conducted to achieve the research objectives. Four years were chosen to illustrate the changes and development over 15 years in Al-Mawaleh North, to record the impact of Al-Mouj. The selected years are 2009, 2014, 2019, and 2024, as shown in

Figure 2 (a, b, c, and d) each spaced five years apart. Primary geographical data and coordinates for these years were obtained from a reliable government agency, the Muscat Municipality. Land use codes were assigned based on land type using Python to create a new attribute field. Maps of land use were then generated with ArcGIS. These spatial analysis maps clearly illustrate land use changes and development, and the increase in buildings over 15 years, classified into residential (low and medium density), commercial, mixed-use, educational, public buildings, healthcare, social areas, and religious use.

Table 1 displays changes in the number of units for each use across the four selected years.

The analysis of land use and land cover maps shows that residential land use experienced the greatest change and growth, increasing from 556 units in 2009 to 1269 in 2024, including single villas, twin villas, and apartments. There has also been a rise in the area’s population density. Meanwhile, commercial land use ranked second in building expansion, growing from 9 units in 2009 to 52 in 2024, including shops, companies, and offices. Mixed-use buildings with commercial and residential uses ranked third, rising from 8 units in 2009 to 17 in 2024. Additionally, the number of educational campuses—comprising private schools, government schools, and colleges—rose from zero units in 2009 to five in 2024. Public and religious buildings also increased from zero units to four over the fifteen years. While many land uses developed over time, some remained unchanged, like healthcare, which maintained only one building throughout the period. Conversely, the social area for indoor meetings and social activities expanded by one building in 2019. The total number of buildings increased by 135.7% between 2009 and 2024.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was created to meet research objectives by collecting participants’ perceptions of Al-Mouj’s social impact on the nearby area. A QR code linking to the questionnaire was provided to visitors in Al-Mouj’s public spaces and surrounding areas. Cochran’s formula is used to determine the sample size needed for a large population with a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. It shows below that a sample size of 384 responses is sufficient, but we received more responses, totaling 511. Participants were 18 years or older, including both men and women. The survey included 14 open-ended and closed-ended questions, written in Arabic and English to ensure clarity for all respondents. The questions covered age, gender, nationality, whether they live near Al-Mouj, how often they visit, their quality of life there, and how it compares to other places in Oman. It also asked about features of Al-Mouj that influence their experience during visits, whether they would like to live in a similar community, and if urban design features, walking paths, and green spaces positively impact mental and physical health. Additionally, it asked if public spaces at Al-Mouj help reduce social isolation and promote social connections, and whether the facilities and design support a diverse and inclusive community with various needs and backgrounds, including those with disabilities. The questionnaire also inquired if they support projects like Al-Mouj in Oman, have noticed increased economic activity, or believe Al-Mouj has created more job opportunities for the local community.

Z = z-value for a confidence level of 95% = 1.96

P = Population Proportion (because it is unknown) = 0.5

e = Margin of error = 0.05

Table 2.

Shows the responses to questions 1 through 7.

Table 2.

Shows the responses to questions 1 through 7.

| Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q5 |

Q6 |

Q7 |

| What is your gender? |

What is your nationality? |

What is your age? |

Do you live near Al-Mouj? |

How often do you visit Al-Wave? |

What are your favorite features of Al-Wave? |

Do you feel the quality of life in Al-Mouj differs from other places in Oman? |

| Male |

Female |

Omani |

Non-Omani |

18-24 |

24-34 |

35-44 |

45-54 |

55-64 |

64 and above |

Yes |

No |

Never |

Once a week |

1-3 times a week |

4-6 times a week |

Daily |

Access to public transportation |

Sustainable Energy Usage |

Community Centers |

Architectural Designs |

Walkability and Cycling Paths |

Parks and Recreational Areas |

Yes |

No |

| 47.9 % |

52.1 % |

67.3 % |

32.7 % |

11.9 % |

34.2 % |

41.3 % |

7.4 % |

2.5 % |

2.5 % |

87.9 % |

12.1 % |

9 % |

14.5 % |

25.5 % |

35 % |

15.7 % |

14.5 % |

13.1 % |

17.7 % |

16.9 % |

19.5 % |

18.3 % |

97.1 % |

2.9 % |

The analysis of responses shows that 52.1% of participants are female, and 67.3% are Omani. 87.9% live near Al-Mouj. The largest age group is 35 to 44, making up 41.3%. Regarding frequent visits to Al-Mouj, 35% go 4-6 times weekly. Participants’ favorite features at Al-Mouj include walkability and cycling paths, parks and recreational areas, and community centers for events and activities. 97.1% believe they experience a better quality of life in Al-Mouj compared to other places in Oman. 83.2% would like to live in a community like Al-Mouj. 56.9% think that the public spaces at Al-Mouj help reduce social isolation and foster social connections. 69.7% feel that the facilities and design support a diverse and inclusive community with various needs and backgrounds, including those with disabilities. 65.4% believe that urban design features, walking paths, and green spaces positively impact mental and physical health. 98.4% want to see more projects like Al-Mouj in Oman. 84.5% noticed increased economic activity in the area. 63.8% believe that Al-Mouj has created more job opportunities for the local community.

Table 3.

Shows the responses to questions 8 through 14.

Table 3.

Shows the responses to questions 8 through 14.

| Q8 |

Q9 |

Q10 |

Q11 |

Q12 |

Q13 |

Q14 |

| Would you like to live in a place like Al-Mouj? |

Do you think public spaces reduce social isolation? |

Do the facilities and design support a diverse and inclusive community? |

Do you think urban design features positively affect mental and physical health? |

Would you like to see projects like Al-Mouj in Oman? |

Have you noticed increased economic activity in the area? |

Do you believe that Al-Mouj has created more job opportunities? |

| Yes |

No |

Neutral |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Neutral |

Significant increase |

Moderate increase |

Limit increase |

No change |

Not sure |

| 83.2 % |

13.7 % |

3.1 % |

56.9 % |

38 % |

3.9 % |

0.6 % |

0.6 % |

69.7 % |

25.8 % |

2.9 % |

1.2 % |

0.4 % |

65.4 % |

31.9 % |

2 % |

0.4 % |

0.4 % |

98.4 % |

1.6 % |

84.5 % |

2.5 % |

12.9 % |

63.8 % |

32.3 % |

1 % |

1 % |

2 % |

Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated using SPSS to evaluate the internal consistency and reliability of the 5-point Likert scale for questions 9, 10, and 11, which assessed quality of life. These questions explored perceptions regarding public spaces that reduce social isolation, facilities and designs that foster a more diverse and inclusive community, and features like walking paths and green areas that positively affect mental and physical health. The resulting Cronbach’s Alpha (0.911) indicates excellent internal consistency and reliability for the scale.

Table 4.

Reliability Statistics for the 5-point Likert Scales of Questions 9, 10, and 11.

Table 4.

Reliability Statistics for the 5-point Likert Scales of Questions 9, 10, and 11.

| Q8 |

Q9 |

Q10 |

Q11 |

Q12 |

Q13 |

Q14 |

| Would you like to live in a place like Al-Mouj? |

Do you think public spaces reduce social isolation? |

Do the facilities and design support a diverse and inclusive community? |

Do you think urban design features positively affect mental and physical health? |

Would you like to see projects like Al-Mouj in Oman? |

Have you noticed increased economic activity in the area? |

Do you believe that Al-Mouj has created more job opportunities? |

| Yes |

No |

Neutral |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Neutral |

Significant increase |

Moderate increase |

Limit increase |

No change |

Not sure |

| 83.2 % |

13.7 % |

3.1 % |

56.9 % |

38 % |

3.9 % |

0.6 % |

0.6 % |

69.7 % |

25.8 % |

2.9 % |

1.2 % |

0.4 % |

65.4 % |

31.9 % |

2 % |

0.4 % |

0.4 % |

98.4 % |

1.6 % |

84.5 % |

2.5 % |

12.9 % |

63.8 % |

32.3 % |

1 % |

1 % |

2 % |

Figure 3.

Displays responses to the questionnaire: (a) questions 1 through 7; (b) questions 8 through 14.

Figure 3.

Displays responses to the questionnaire: (a) questions 1 through 7; (b) questions 8 through 14.

Correlation analysis measured the strength and direction of the linear relationship between questions 7 to 12.

Table 5 shows the results, which include three types of correlations: strong positive, positive, and negative. The strong positive correlation indicates that responses supporting the idea that Al-Mouj’s urban design features promote mental and physical health are also linked to increased opportunities for fostering a diverse and inclusive community. The negative correlation reveals that respondents who do not like living in a community like Al-Mouj agree that its facilities and design support a diverse and inclusive community.

Thematic analysis using NVivo software was conducted on 511 responses to the open-ended question about whether participants would like to live in a place like Al-Mouj, along with their reasons for or against it. The responses were collected and combined into a single file. This file was imported into NVivo to code and analyze similar responses under main categories. The analysis showed that respondents favored living in Al-Mouj due to the quality of life, mixed land use, architectural designs, active transportation infrastructure, and green and public spaces. Conversely, reasons against included cultural barriers related to differing lifestyles from Omani culture, traffic congestion caused by the roundabout before the entrance of Al-Mouj, lack of privacy in some areas, and the high cost of rent or ownership. Neutral responses were also attributed to cultural barriers, privacy concerns, and unaffordability. The questionnaire’s thematic analysis results are presented in

Figure 4a,b.

Interview

A structured interview was conducted to investigate the economic impact of Al-Mouj on local businesses and the surrounding real estate. The interview included seven questions about the interviewee’s occupation, how long they have worked in the area, whether they noticed any specific changes or developments in their business since the establishment of the Al-Mouj project, how Al-Mouj has affected economic activities in the area, their views on competition among entrepreneurs and business owners in the area, their perspectives on the real estate market and rental prices near Al-Mouj compared to other parts of Muscat, and whether they believe sustainable projects like Al-Mouj attract foreign investments and appeal to investors and users. Participants were chosen because they had been business owners in Al-Mouj or nearby for at least 12 years, ensuring they had observed economic growth since the start of the Al-Mouj project or earlier. Four business owners specializing in real estate, construction, and engineering consultancy were interviewed. These four interviews provided valuable qualitative insights from industry experts regarding Al-Mouj’s impact on local economic activity.

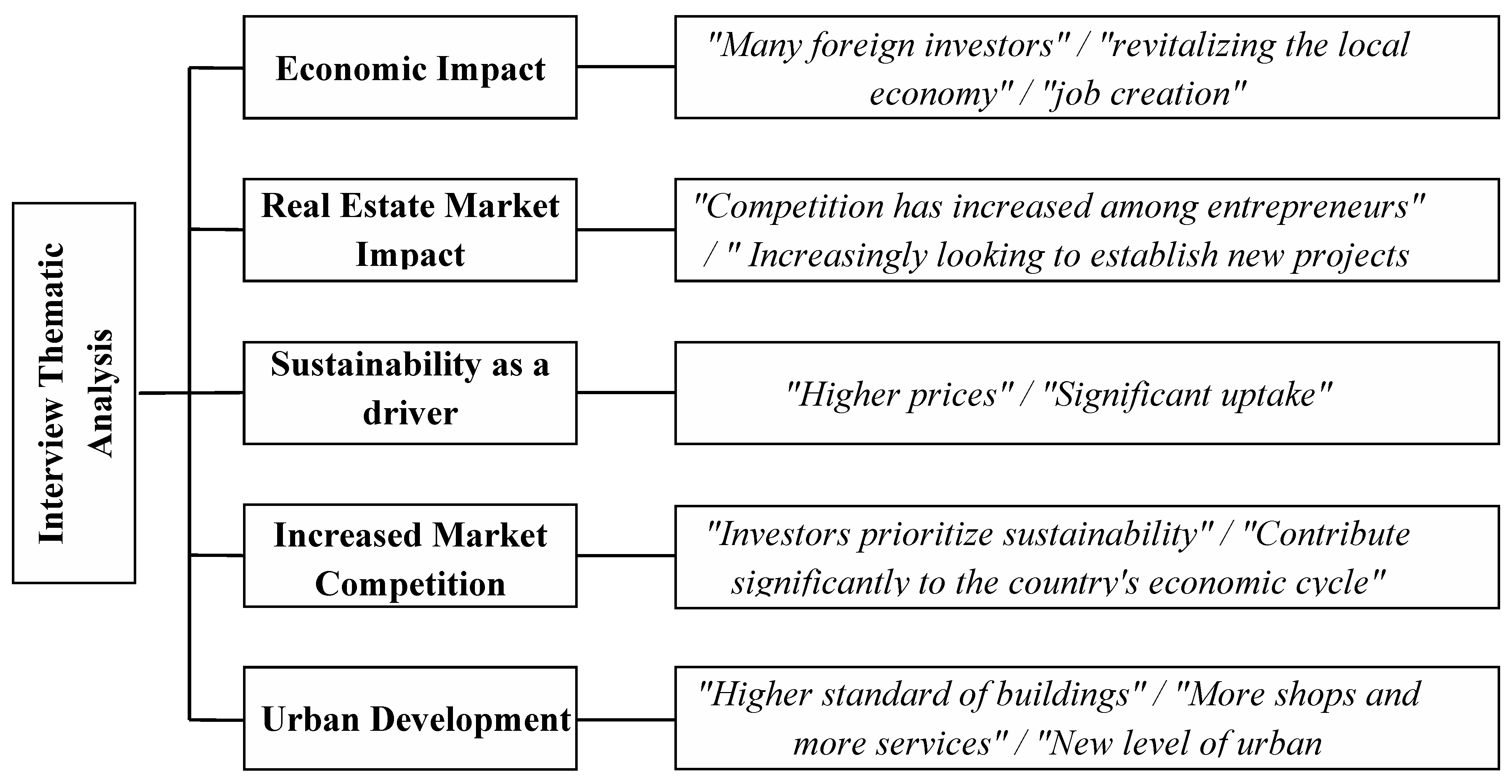

A thematic analysis of the qualitative data collected from the interviews was conducted. The responses were transcribed, reviewed, and combined into a single file for comparison. Six main themes were identified: economic impact, real estate market impact, sustainability as a driver, increased market competition, and urban development.

Figure 5 displays the six themes derived from the interview analysis, including quotes from interviewees.

Results and Discussion

From 2009 to 2024, the Al-Mawaleh North area experienced significant growth in the number of buildings and land use diversity, starting with the development of Al-Mouj. The expansion of residential areas indicates that the region has attracted many residents, leading to population growth and increased demand for services and land uses supporting infrastructure, such as improved educational, public, healthcare, and religious facilities. The increase in commercial activities, including mixed-use developments, companies, offices, restaurants, and shops, reflects economic growth in Al-Mawaleh North and points to a diverse, investment-friendly local economy.

The questionnaire showed that Al-Mouj’s public spaces and facilities effectively meet local needs, with 67.3% of participants being locals. Additionally, they indicated that these spaces and amenities are accessible to people beyond Al-Mouj residents, as 87.9% of participants are visitors from nearby areas who come to Al-Mouj for social and economic activities during the week, mainly 4 to 6 times per week, and on weekends when special events are held for various age groups. Most participants believe that living in Al-Mouj or nearby offers a higher quality of life and express interest in living in similar communities, trusting that public spaces and facilities can enhance visitors’ mental and physical health, not just those of residents. Furthermore, a strong connection exists between quality of life and its impact on social interaction, health, and economic growth, with 84.5% noting increased economic activity and job opportunities.

The correlation analysis and thematic analysis of the questionnaire indicate that, although locals enjoy and benefit from Al-Mouj’s public spaces and facilities, they still perceive cultural barriers to living there. The living spaces were designed based on international standards, which differ from traditional preferences. Privacy in Al-Mouj also varies from what locals prefer, especially regarding residential spaces and building designs. Additionally, traffic congestion on the main street outside Al-Mouj, leading to the main entrances between Al-Mouj and Al-Mawaleh North, has increased due to a growing population and traffic. During rush hours, the current infrastructure is overwhelmed, particularly at peak times, and a solution from the municipality is required.

Real estate prices inside Al-Mouj are not affordable, so many development projects have been built around Al-Mouj at more reasonable prices. These projects attract high demand from locals who want to live in a traditional and local style, while also benefiting from social facilities and economic activities near the sustainable neighborhood of Al-Mouj. Additionally, the economic activities within Al-Mouj attract international brands mainly because of the high rent or ownership costs, which encourage local brands to open outside Al-Mouj, close enough to serve residents with more competitive prices. This has helped the growth of local brands in the surrounding area.

The interviewees emphasized Al-Mouj’s economic impact based on their recent observations of the surrounding area. All participants agreed that the area has seen significant economic growth over the past 12 years. These changes include various factors, such as more shops, increased foreign and local investments, and improved employment opportunities. The presence of Al-Mouj has enhanced competitiveness among entrepreneurs and investors to start new projects and branches of well-known international restaurants and stores on Al-Mouj Street, located in Al-Mawaleh North. They also noted that it has attracted many young people to start small ventures across from Al-Mouj, drawing in residents and encouraging youth to be more innovative in developing and launching new investment projects as demand increases. Based on their experience and expertise in the real estate market, the interviewees observe a rise in property values around Al-Mouj compared to other parts of Muscat Governorate. This is due to the high standards of buildings that closely match Al-Mouj’s standards, attracting locals who want to live at a similar sustainable level but with a local style, as well as the proximity to many services provided by Al-Mouj and its surrounding area.

Conclusions

Countries can rely on sustainable neighborhood development to generate positive social and economic impacts in both the short and long term, reaching nearby districts when developed as open communities that attract visitors, users, and investors. However, this impact cannot be measured by NSATs. Achieving positive social and economic impacts on local communities is just as important as earning an international certificate in sustainable development for communities. Sustainable open communities that attract regional and global investments effectively support the local economy. Developing sustainable neighborhoods, recognizing that healthy lifestyles are not limited to residents but also extend to surrounding districts, can improve social cohesion and maximize the positive social impact of sustainable development. Sustainable neighborhood development also positively affects the surrounding area by demonstrating an excellent example of how high-quality building standards can meet market demand.

This study tested reliable criteria to investigate a sustainable neighborhood’s social and economic impact on the surrounding area. It confirms that sustainable development can enhance local economic growth by creating opportunities for healthy competition among international and local entrepreneurs and increasing job opportunities. It also promotes economic sustainability by supporting the local economy for both current residents and future generations through sustainable solutions and infrastructure. Affordable living is a key element that should be included in sustainable communities. It must be carefully managed to ensure everyone can afford to live there. Sustainable practices can support inclusive communities, social cohesion, quality of life, well-being, and mental and physical health beyond the boundaries of certified sustainable neighborhoods.

Al-Mouj introduced a new lifestyle through mixed-use development to the local community, supporting the economy and encouraging social cohesion. It has also shifted local consumer preferences toward sustainable practices that impact both the short and long term, providing a new perspective on quality of life. Although this new perspective may differ from traditional standards, it remains acceptable to some extent to the local society and can still improve mental and physical health. Al-Mouj was developed following international standards for sustainable open communities with some privacy, which has helped attract locals and people from different countries to its unique lifestyle. Privacy takes different forms and meanings in various societies and cultures. While international assessment tools like BREEAM consider Al-Mouj a private gated community, its privacy remains negotiable for the local community. This highlights the need for local standards and a neighborhood sustainability assessment tool that considers local needs and promotes sustainable practices.

Some challenges have arisen in finding business owners for interviews who have lived in the area for the past 15 years and can serve as witnesses to the economic impact of Al-Mouj on the Al-Mawaleh North district. A future study is necessary to compare urban development in Al-Mawaleh North and Al-Mawaleh South within a 7 km radius of Al-Mouj to determine the extent to which the sustainable neighborhood influences the social and economic aspects of the surrounding area. Additionally, future studies could explore ways to design local tools for sustainability assessment to establish Omani standards for Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment Tools suitable for the Omani context.

Author Contributions

The authors worked collaboratively as follows: “Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing, E.N. and M.K.; Software, analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, E.N. and A.A.; Supervision, E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The questionnaire was approved by the Research and Innovation office of Global College of Engineering and Technology (January 7, 2025) and the Research & Faculty Promotion Committee of Scientific College of Design (January 29, 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the interviews.

Data Availability Statement

Primary geographical data and coordinates for the study area were obtained from the Muscat Municipality, a reliable government agency. However, these data are not available for open access publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Muscat Municipality for providing the primary geographical data and supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NSAT |

Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment Tools |

| BREEAM |

Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method |

| BRE |

Building Research Establishment |

| SD |

Sustainable Development |

| TCOS |

Technological, Commercial, Organizational, and Societal) |

| LULC |

Land Use and Land Cover |

| ITC |

Integrated Tourism Complex |

| ArcGIS |

ArcGIS is a comprehensive Geographic Information System software developed by Esri |

| SPSS |

Statistical Product and Service Solutions software |

| NVivo |

Non-numerical Unstructured Data Indexing, Searching, and Theorizing software |

References

- WCED. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; WCED: Cape Town, South Africa, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- D’adamo, I.; Ioppolo, G.; Shen, Y.; Rosen, M.A. Sustainability Survey: Promoting Solutions to Real-World Problems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What is Sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’adamo, I.; Sassanelli, C. Biomethane Community: A Research Agenda towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, T.; Sakurai, R. Have Sustainable Development Goal Depictions Functioned as a Nudge for the Younger Generation before and during the COVID-19 Outbreak? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajačić, K.G.; Duić, N.; Rosen, M.A.; Al-Nimr, M.A. Advances in integration of energy, water and environment systems towards climate neutrality for sustainable development. Energy Conversion and Management 2020, 225, 113410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiso, A.F.; O’neill, E.; Brereton, F.; Abeje, W. Rapid Urbanization in Ethiopia: Lakes as Drivers and Its Implication for the Management of Common Pool Resources. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U. Sustainability assessment of urban communities through rating systems. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 1573–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, W.; Wackernagel, M. Urban ecological footprints: Why cities cannot be sustainable—And why they are a key to sustainability. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 1996, 16, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawodu, A.; Akinwolemiwa, B.; Cheshmehzangi, A. A conceptual re-visualization of the adoption and utilization of the Pillars of Sustainability in the development of Neighbourhood Sustainability Assessment Tools. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 28, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C., A.; Howard, E.; Osborne, F.J. Garden Cities of To-Morrow. Population 1968, 23, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.; Stout, F.; LeGates, R.T. The Neighborhood Unit: from The Regional Plan of New York and its Environs (1929), 7 ed.; Routledge, 2020; pp. 557–569. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Vintage Digital, 2016, pp. 55-60.

- Xia, B.; Chen, Q.; Skitmore, M.; Zuo, J.; Li, M. Comparison of sustainable community rating tools in Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Murayama, A. Neighborhood sustainability assessment in action: Cross-evaluation of three assessment systems and their cases from the US, the UK, and Japan. Build. Environ. 2014, 72, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanarella, E.J.; Levine, R.S. Does sustainable development lead to sustainability? Futures 1992, 24, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, L.; Michell, K.; Viruly, F. A Critique of the Application of Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment Tools in Urban Regeneration. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudlin, D. Sustainable urban neighbourhood: building the 21st century home; Routledge, 2010; p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alov, I.N.; Petrović, M.D.; Belyaeva, A.M. Evaluating the Economic Sustainability of Two Selected Urban Centers—A Focus on Amherst and Braintree, MA, USA. Sustainability 2024, 16, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Sen, A. Human Development and Economic Sustainability. World Development 2000, 28, 2029–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Murayama, A. A critical review of seven selected neighborhood sustainability assessment tools. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 38, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawodu, A.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; Sharifi, A.; Oladejo, J. Neighborhood sustainability assessment tools: Research trends and forecast for the built environment. Sustain. Futur. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRE Global, “BREEAM In-Use International Technical Manual: Commercial,” www.breeam.org, Watford, UK, 2020.

- Rubilar, P.P.; Vidal, M.M.J.; Fernández, D.B.; Ramirez, M.O.; Torres, L.P.; Vial, M.L.; Calquin, D.L.; Fabregat, F.P.; Pedreño, J.N. Neighbourhood Sustainability Assessment Tools for Sustainable Cities and Communities, a Literature Review—New Trends for New Requirements. Buildings 2023, 13, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeily, A.; Srinivasan, R.S. A need for balanced approach to neighborhood sustainability assessments: A critical review and analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2015, 18, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorza, F.; Fortunato, G.; Carbone, R.; Murgante, B.; Pontrandolfi, P. Increasing Urban Walkability through Citizens’ Participation Processes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.; Arribas-Bel, D.; Rowe, F. Tracking the Transit Divide: A Multilevel Modelling Approach of Urban Inequalities and Train Ridership Disparities in Chicago. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, P. Urban design and local economic development: A case study in Birmingham. Cities 1995, 12, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.; Wood, L.; Foster, S.A.; Giles-Corti, B.; Frank, L.; Learnihan, V. Sense of Community and Its Association With the Neighborhood Built Environment. Environ. Behav. 2013, 46, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, R.; Kearns, A. Social Cohesion, Social Capital and the Neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2125–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyden, K.M. Social Capital and the Built Environment: The Importance of Walkable Neighborhoods. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1546–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choguill, C.L. Developing sustainable neighbourhoods. Habitat international 2008, 38, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Brown, C.; Bramley, G. The key to sustainable urban development in UK cities? The influence of density on social sustainability. Prog. Plan. 2012, 77, 89–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, B.S.; Ţîrcă, D.M. Innovations for sustainable development: Moving toward a sustainable future. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, T.A.; Hassan, Q.K.; Ishaq, S.; Batool, M.; Butt, H.J.; Jabbar, H. Investigative Spatial Distribution and Modelling of Existing and Future Urban Land Changes and Its Impact on Urbanization and Economy. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Santosa, A.; Zetterberg, L.; Kawachi, I.; Ng, N. Social Capital and Sustainable Social Development—How Are Changes in Neighbourhood Social Capital Associated with Neighbourhood Sociodemographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stessens, P.; Canters, F.; Khan, A.Z. Exploring Options for Public Green Space Development: Research by Design and GIS-Based Scenario Modelling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinaudeau, B.; Brink, M.; Schäffer, B.; Schlaepfer, M.A. A Methodology for Quantifying the Spatial Distribution and Social Equity of Urban Green and Blue Spaces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnançoğlu, S.; Uzunahmet, H.A.; Özden, Ö. The Effect of Green Spaces on User Satisfaction in Historical City of Nicosia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaradia, F.; Lelo, K.; Monni, S.; Tomassi, F. The 15-Minute City: An Attempt to Measure Proximity to Urban Services in Rome. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zghoul, S.; Al-Homoud, M. GIS-Driven Spatial Planning for Resilient Communities: Walkability, Social Cohesion, and Green Infrastructure in Peri-Urban Jordan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, S.; Longo, D.; Turillazzi, B. Integrating Security-by-Design into Sustainable Urban Planning for Safer, More Accessible, and Livable Public Spaces. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunuwila, P.; Daigo, I.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Liyanage, D.J.T.S.; Gong, W.T.; Hatayama, H.; Shobatake, K.; Tahara, K.; Hoshino, T. Social Life Cycle Assessment Methodology to Capture “More-Good” and “Less-Bad” Social Impacts—Part 1: A Methodological Framework. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, K. Ethnographic analysis. In Ethnographic Methods, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, 2012; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- BREEAM, “Explore BREEAM,” 2022. Available online: https://tools.breeam.com/projects/explore/buildings.jsp?sectionid=0&projectType=&rating=&countryID=512&client=&description=&certBody=&certNo=&developer=&location=&buildingName=&assessor=&subschemeid=0&Submit=Search (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Al-Mouj Muscat. Available online: https://www.almouj.com/en/news/al-mouj-muscats-golf-beach-residences-achieves-omans-first-ever-breeam-sustainability-certification/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Arab Urban Development Institute. Available online: https://araburban.org/en/infohub/projects/?id=6850 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- The Wave Muscat. The Wave, Muscat “Main Brochure”. Available online: https://www.thewavecommunity.com/file_save.php?save_file=93 (accessed on 17 August 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).