Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

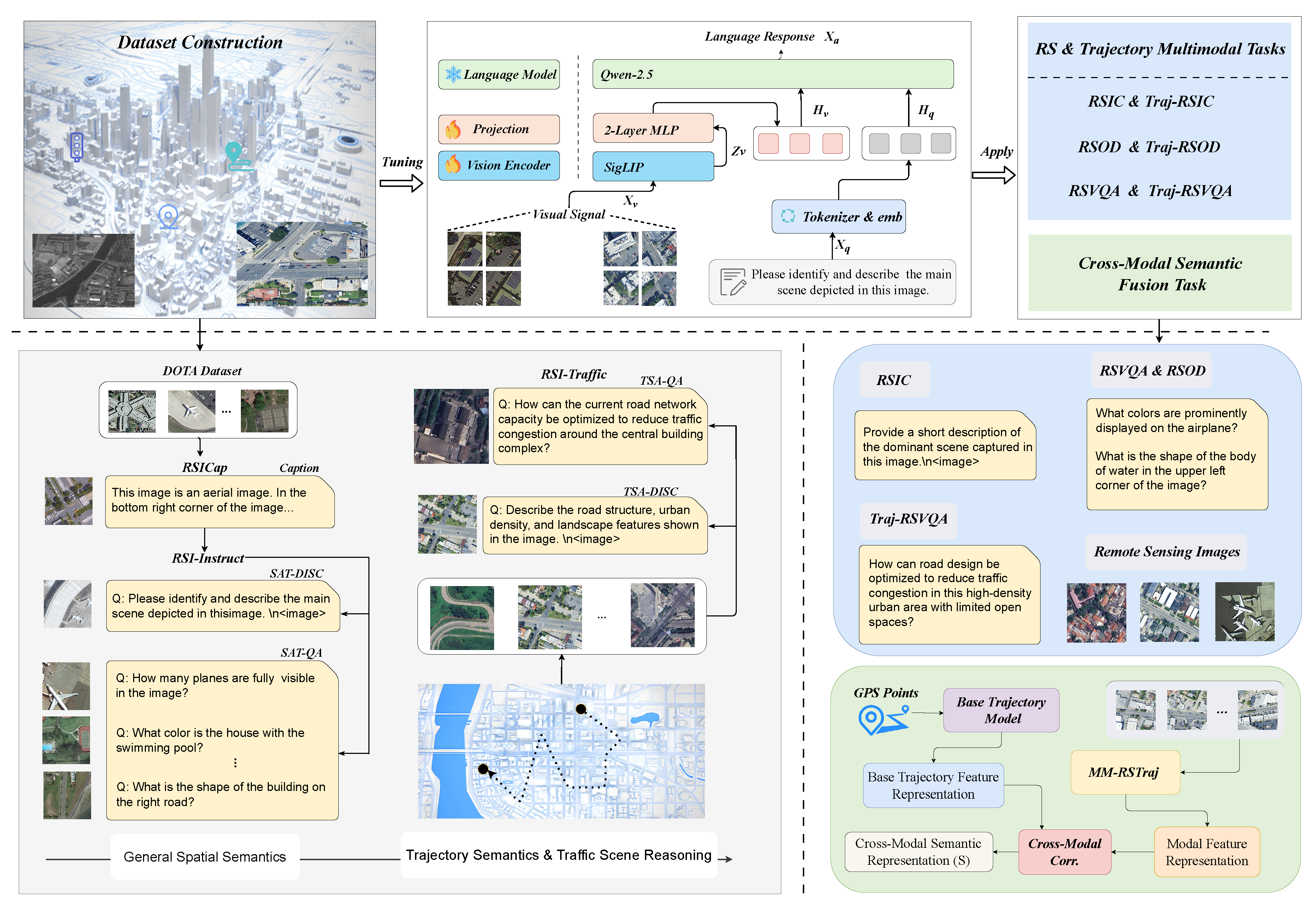

- We construct the first multimodal instruction dataset system for remote sensing and trajectory traffic semantics. Specifically, we extend RSICap into RSI-Instruct with multi-turn dialogues for general remote sensing semantics, and develop RSI-Traffic, focusing on trajectory-related elements such as road structures and building layouts.

- We propose MM-RSTraj, the first remote-sensing-assisted multimodal large language model designed for trajectory traffic understanding. Built on the LLaVA-OneVision architecture, MM-RSTraj employs a two-stage strategy that combines general remote sensing pretraining with trajectory-specific fine-tuning, optimizing cross-modal semantic alignment.

- We validate MM-RSTraj on both trajectory semantic evaluation and general remote sensing tasks. The experiments show that MM-RSTraj achieves superior performance in trajectory-related evaluation while maintaining competitive results on RSIC and RSVQA.

2. Related Work

2.1. Vision-Language Models for Remote Sensing

2.2. Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs)

2.3. Instruction Tuning in MLLMs

2.4. Remote Sensing Multimodal Datasets

3. Dataset Construction

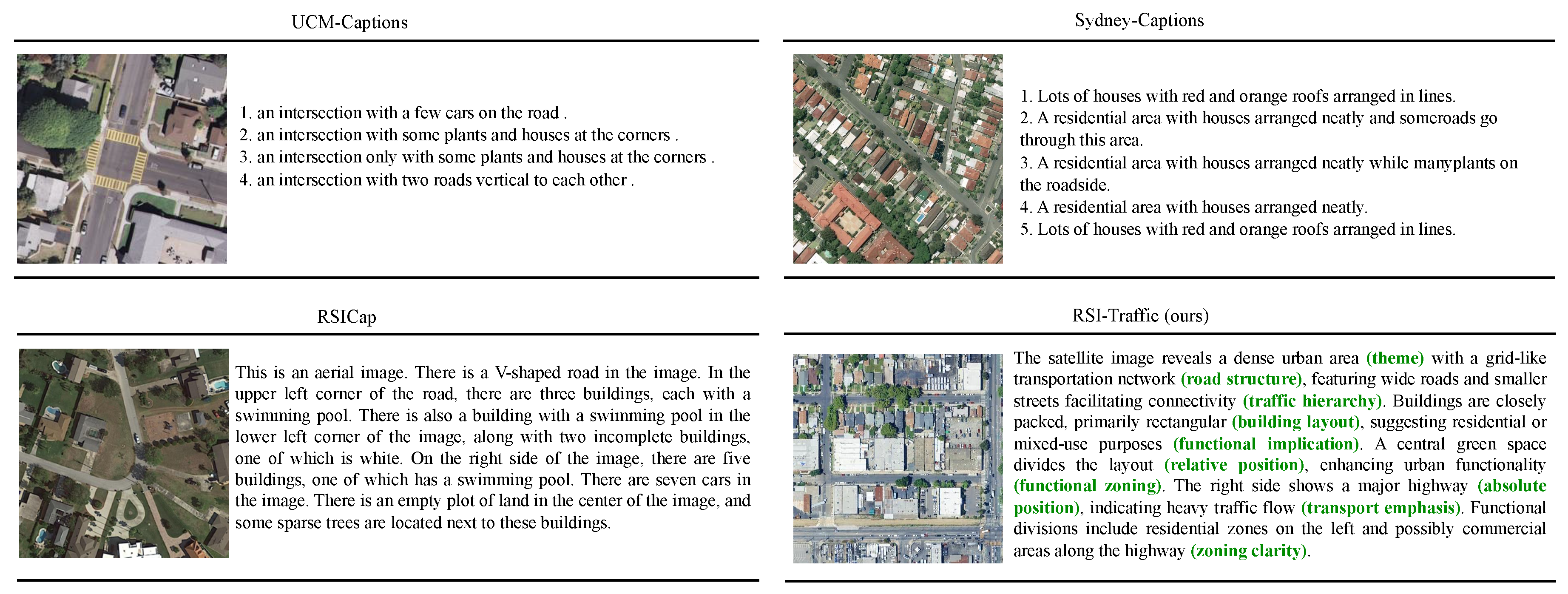

3.1. RSI-Instruct

3.1.1. Motivation and Dataset Foundation

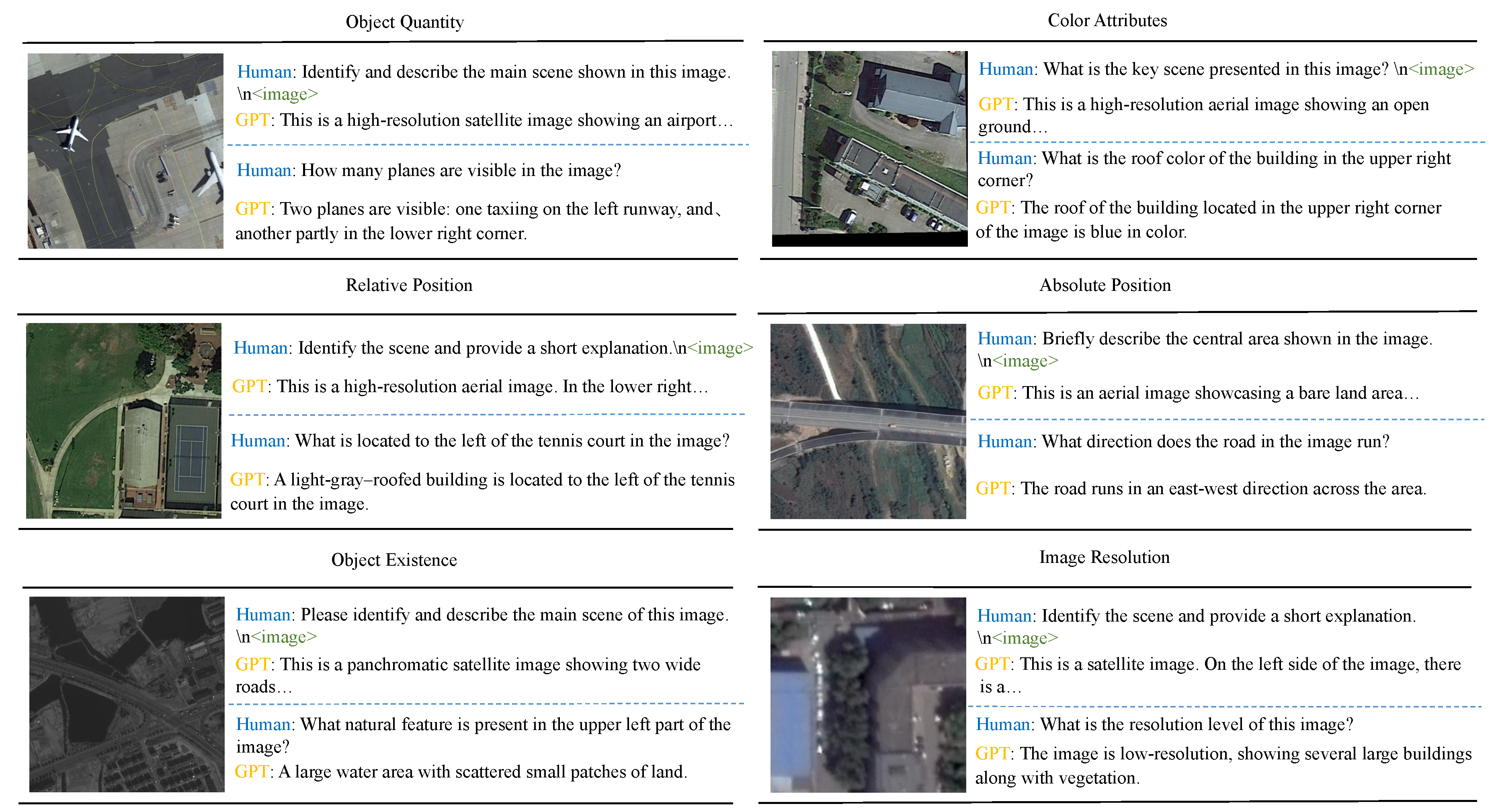

3.1.2. Multi-Turn Instruction-Response Construction

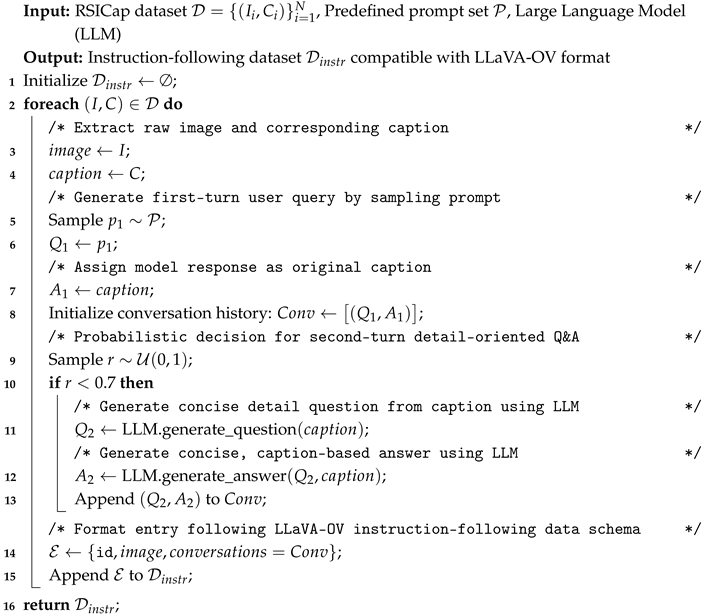

| Algorithm 1: Construction of RSI-Instruct Dataset |

|

3.1.3. Semantic Diversity and Fine-Grained Attributes

3.2. RSI-Traffic

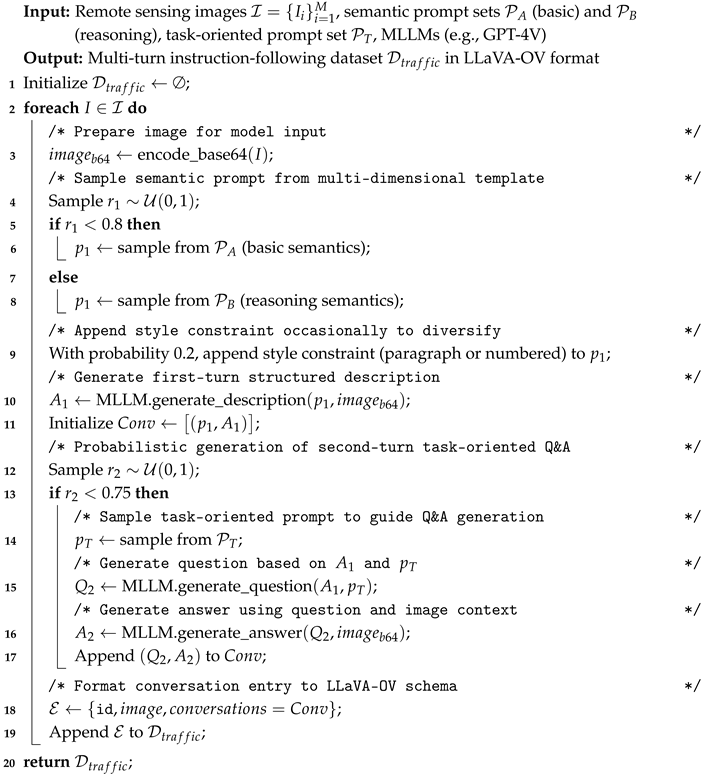

| Algorithm 2: Construction of RSI-Traffic Dataset |

|

3.2.1. Urban Remote Sensing Image Acquisition and Selection

| Region | Data Source | #Images | Zoom 18/19 | Avg. Score | Feature Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles | LocalCBD | 650 | 220 / 483 | 9 | Complex and clear traffic structure in the urban core, well-planned layout. |

| Singapore | Grab-Posisi | 1,000 | 492 / 386 | 9 | Efficient transport network and high-density buildings with excellent image structure. |

| Beijing | GeoLife | 300 | 168 / 79 | 6 | Sparse trajectory distribution; weak semantic expression and lower resolution in some areas. |

| Jakarta | Grab-Posisi | 350 | 145 / 183 | 6 | Incomplete road system with evident traffic congestion. |

| UCI Area | UCI | 316 | 95 / 93 | 8 | Clear image structure, suitable for studies on urban fringe and mixed-use areas. |

3.2.2. Multi-Dimensional Prompt Design and Multi-Turn Semantic Dialogue Generation

3.2.3. Manual Review and Quality Control

3.2.4. Visualization of Data Quality

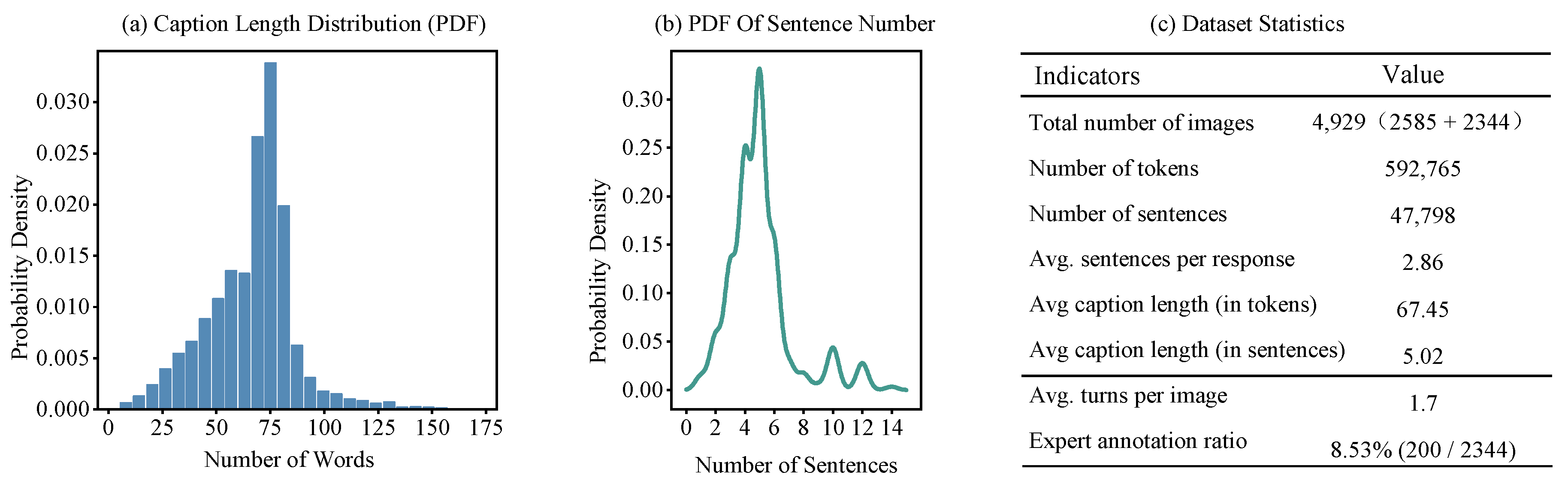

3.3. Statistical Analysis of RSI-Instruct and RSI-Traffic

4. Method

4.1. Problem Statement

4.2. Overall Workflow

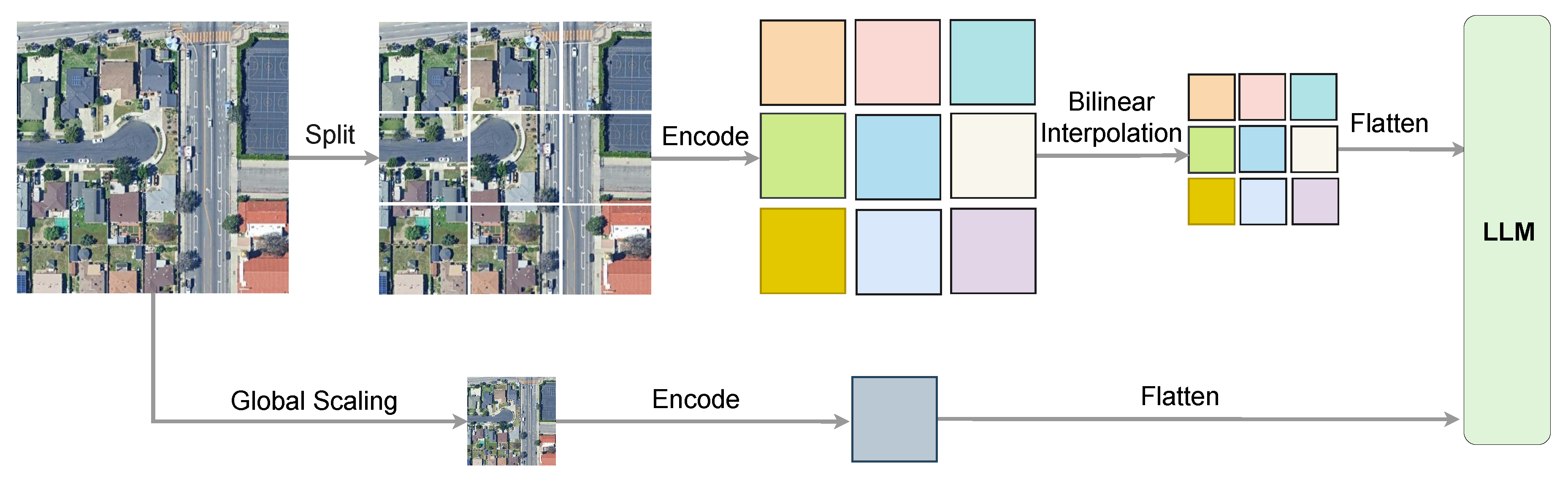

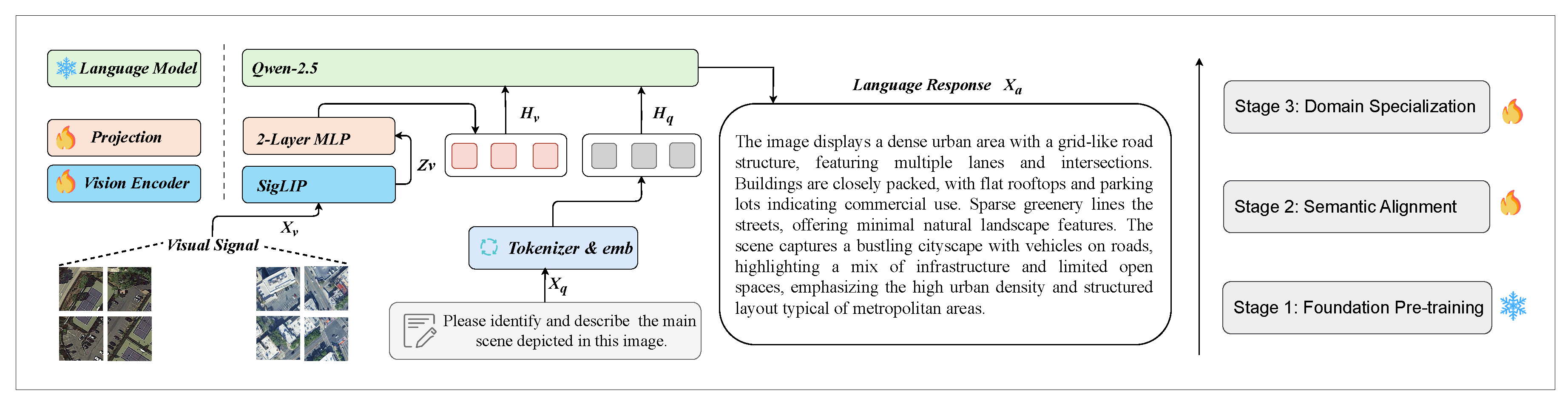

4.3. Network Structure

4.3.1. Vision Encoder

4.3.2. Projector

4.3.3. LLM

4.3.4. Higher AnyRes with Bilinear Interpolation

4.4. Training Strategy

5. Experiments

5.1. Implementation Details

5.2. Evaluation Metrics For RSIC

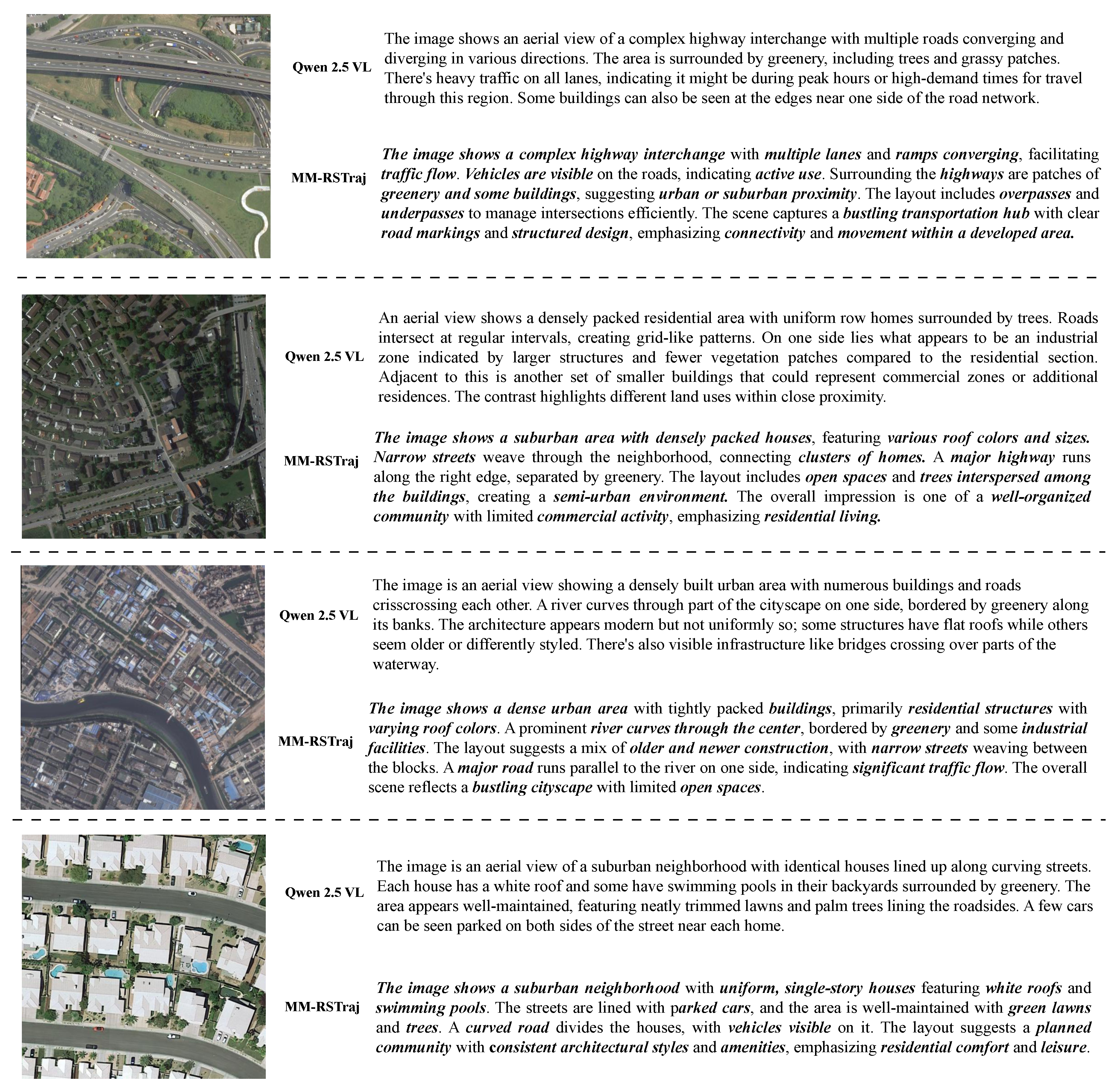

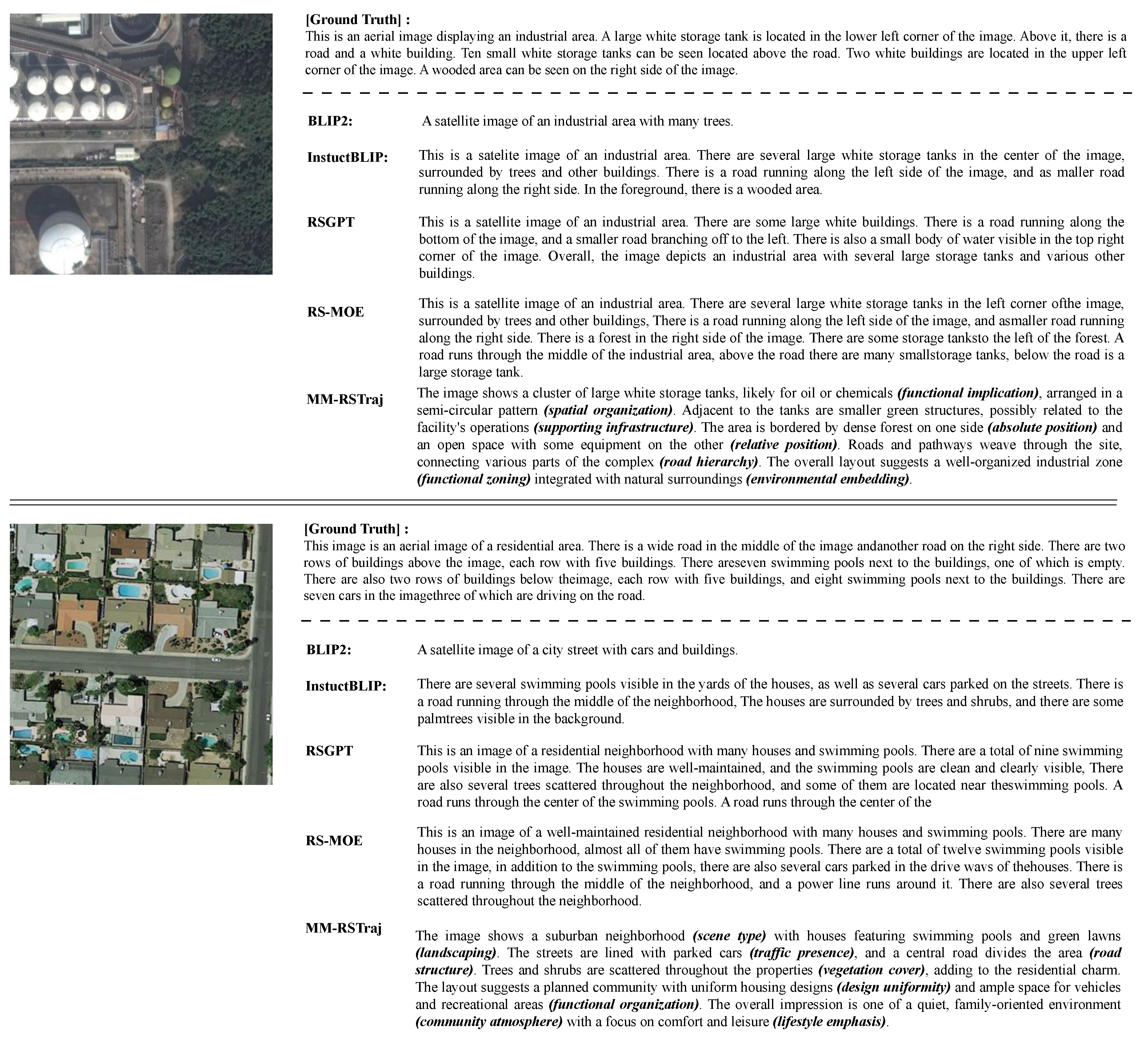

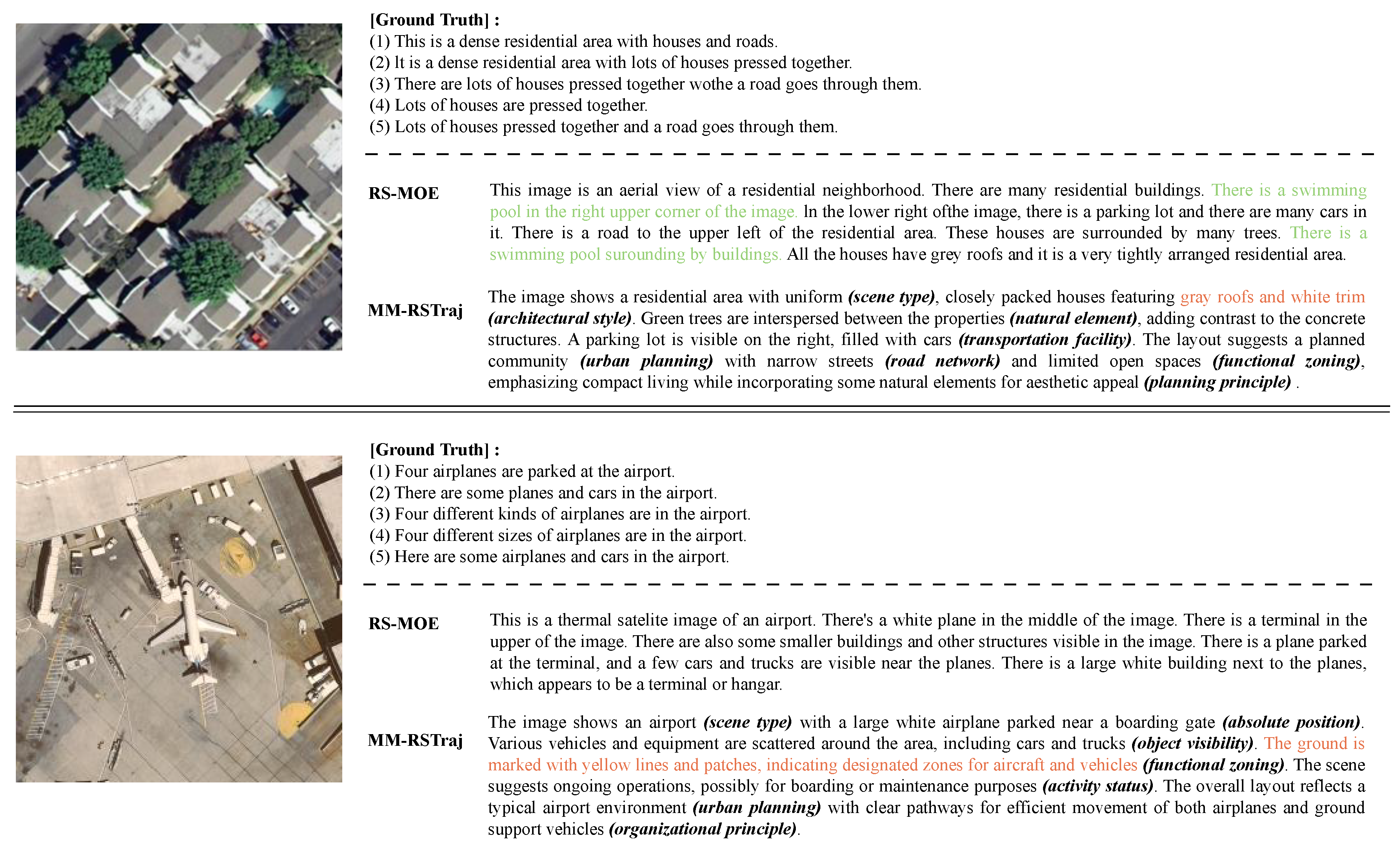

5.3. General Semantic Evaluation for Remote Sensing

5.3.1. RSIC Task on RSIEval

5.3.2. RSIC Task on UCM-Captions

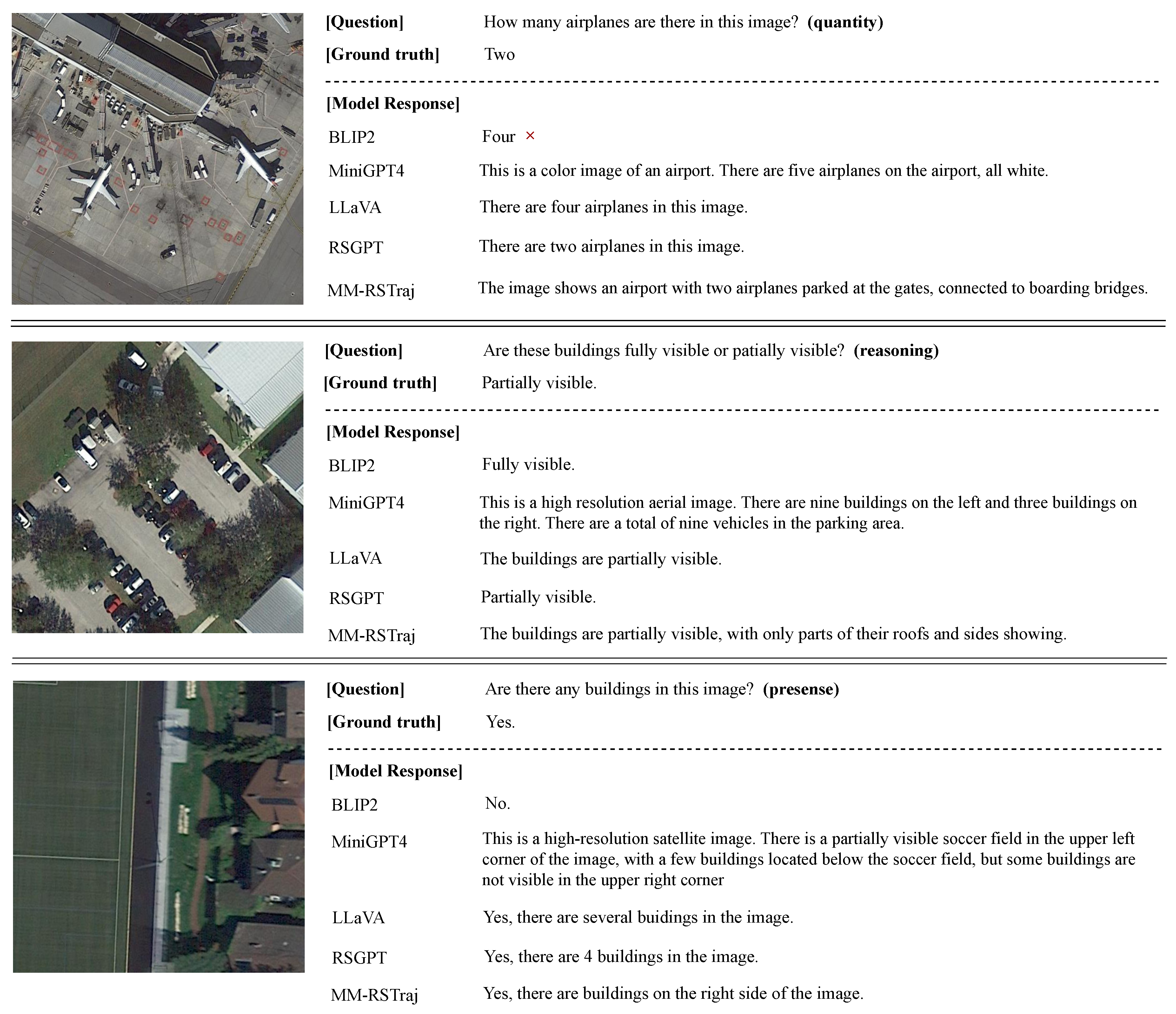

5.3.3. RSVQA Task on RSIEval

5.4. Trajectory Traffic Semantic Evaluation for Remote Sensing

6. Conclusion

7. Limitation and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Xia, L.; Xu, Y.; Huang, C. Flashst: A simple and universal prompt-tuning framework for traffic prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.17898 2024.

- Ma, Z.; Tu, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, D.; Zhou, G.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Gong, J. More than routing: Joint GPS and route modeling for refine trajectory representation learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, 2024, pp. 3064–3075.

- Li, Z.; Xia, L.; Tang, J.; Xu, Y.; Shi, L.; Xia, L.; Yin, D.; Huang, C. Urbangpt: Spatio-temporal large language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2024, pp. 5351–5362.

- Deng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Xia, Y.; Zheng, K. Learning to hash for trajectory similarity computation and search. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE). IEEE, 2024, pp. 4491–4503.

- Li, S.; Chen, W.; Yan, B.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Yu, Y. Self-supervised contrastive representation learning for large-scale trajectories. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 148, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Cheng, H.; Guo, C.; Gao, H.; Hu, J.; Yang, S.B.; Yang, B. Mm-path: Multi-modal, multi-granularity path representation learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V. 1, 2025, pp. 1703–1714.

- Yan, Y.; Wen, H.; Zhong, S.; Chen, W.; Chen, H.; Wen, Q.; Zimmermann, R.; Liang, Y. Urbanclip: Learning text-enhanced urban region profiling with contrastive language-image pretraining from the web. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, 2024, pp. 4006–4017.

- Yuan, Q.; Shen, H.; Li, T.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, H.; Tan, W.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; et al. Deep learning in environmental remote sensing: Achievements and challenges. Remote sensing of Environment 2020, 241, 111716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakogeorgiou, I.; Karantzalos, K. Evaluating explainable artificial intelligence methods for multi-label deep learning classification tasks in remote sensing. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 103, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, C.; Wu, M. D-LinkNet: LinkNet with pretrained encoder and dilated convolution for high resolution satellite imagery road extraction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2018, pp. 182–186.

- Yuan, Y.; Ding, J.; Feng, J.; Jin, D.; Li, Y. Unist: A prompt-empowered universal model for urban spatio-temporal prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2024, pp. 4095–4106.

- Xu, R.; Huang, W.; Zhao, J.; Chen, M.; Nie, L. A spatial and adversarial representation learning approach for land use classification with POIs. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2023, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, Z.; Huang, W.; Gong, Y.; Yin, Y. Profiling urban streets: A semi-supervised prediction model based on street view imagery and spatial topology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2024, pp. 319–328.

- OpenAI. ChatGPT: A Language Model for Conversational AI. Tech. rep., OpenAI, 2023.

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 2023.

- Peng, B.; Li, C.; He, P.; Galley, M.; Gao, J. Instruction tuning with gpt-4. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.03277 2023.

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D.; et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S. Blip: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2022, pp. 12888–12900.

- Chen, J.; Guo, H.; Yi, K.; Li, B.; Elhoseiny, M. Visualgpt: Data-efficient adaptation of pretrained language models for image captioning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 18030–18040.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PmLR, 2021, pp. 8748–8763.

- Lu, X.; Wang, B.; Zheng, X.; Li, X. Exploring models and data for remote sensing image caption generation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 56, 2183–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Tang, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, C. Description generation for remote sensing images using attribute attention mechanism. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fang, S.; Jiao, L.; Liu, R.; Shang, R. A multi-level attention model for remote sensing image captions. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, B.; Du, X.; Lu, X. Mutual attention inception network for remote sensing visual question answering. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, C.; Mendez, V.; Walt, E.; Lobry, S.; Le Saux, B.; Tuia, D. Language Transformers for Remote Sensing Visual Question Answering. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2022-2022 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. IEEE, 2022, pp. 4855–4858.

- Li, A.; Lu, Z.; Wang, L.; Xiang, T.; Wen, J.R. Zero-shot scene classification for high spatial resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 55, 4157–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Structural alignment based zero-shot classification for remote sensing scenes. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Electronics and Communication Engineering (ICECE). IEEE, 2018, pp. 17–21.

- Awadalla, A.; Gao, I.; Gardner, J.; Hessel, J.; Hanafy, Y.; Zhu, W.; Marathe, K.; Bitton, Y.; Gadre, S.; Sagawa, S.; et al. Openflamingo: An open-source framework for training large autoregressive vision-language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.01390 2023.

- Ye, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, H.; Hu, A.; Yan, M.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Zhou, J. mplug-owl3: Towards long image-sequence understanding in multi-modal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04840 2024.

- Hu, J.; Yao, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yu, T.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Large multilingual models pivot zero-shot multimodal learning across languages. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12038 2023.

- Bai, S.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Song, S.; Dang, K.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; et al. Qwen2. 5-vl technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13923 2025.

- Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ye, S.; Gu, L.; Tian, H.; Duan, Y.; Su, W.; Shao, J.; et al. Internvl3: Exploring advanced training and test-time recipes for open-source multimodal models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.10479 2025.

- Comanici, G.; Bieber, E.; Schaekermann, M.; Pasupat, I.; Sachdeva, N.; Dhillon, I.; Blistein, M.; Ram, O.; Zhang, D.; Rosen, E.; et al. Gemini 2.5: Pushing the frontier with advanced reasoning, multimodality, long context, and next generation agentic capabilities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.06261 2025.

- Han, J.; Zhang, R.; Shao, W.; Gao, P.; Xu, P.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, C.; Wen, S.; Guo, Z.; et al. Imagebind-llm: Multi-modality instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.03905 2023.

- Sanh, V.; Webson, A.; Raffel, C.; Bach, S.H.; Sutawika, L.; Alyafeai, Z.; Chaffin, A.; Stiegler, A.; Scao, T.L.; Raja, A.; et al. Multitask prompted training enables zero-shot task generalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.08207 2021.

- Hong, W.; Yu, W.; Gu, X.; Wang, G.; Gan, G.; Tang, H.; Cheng, J.; Qi, J.; Ji, J.; Pan, L.; et al. GLM-4.1 V-Thinking: Towards Versatile Multimodal Reasoning with Scalable Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.01006 2025.

- Li, L.H.; Yatskar, M.; Yin, D.; Hsieh, C.J.; Chang, K.W. Visualbert: A simple and performant baseline for vision and language. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.03557 2019.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual instruction tuning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 34892–34916. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, P.; Xu, P.; Iyer, S.; Sun, J.; Mao, Y.; Ma, X.; Efrat, A.; Yu, P.; Yu, L.; et al. Lima: Less is more for alignment. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 55006–55021. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, W.L.; Li, Z.; Lin, Z.; Sheng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhuang, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Gonzalez, J.E.; et al. Vicuna: An open-source chatbot impressing gpt-4 with 90%* chatgpt quality. See https://vicuna. lmsys. org (accessed 14 April 2023) 2023, 2, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wen, C.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Rsgpt: A remote sensing vision language model and benchmark. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2025, 224, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fu, C.; Chen, P.; Zhang, M.; Li, K.; Sun, X.; Wu, Y.; Lin, S.; Ji, R. Aligning and prompting everything all at once for universal visual perception. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 13193–13203.

- Oquab, M.; Darcet, T.; Moutakanni, T.; Vo, H.; Szafraniec, M.; Khalidov, V.; Fernandez, P.; Haziza, D.; Massa, F.; El-Nouby, A.; et al. Dinov2: Learning robust visual features without supervision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.07193 2023.

- Gan, Z.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; et al. Vision-language pre-training: Basics, recent advances, and future trends. Foundations and Trends® in Computer Graphics and Vision 2022, 14, 163–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Yan, H.; Ding, K. CLIP-MoA: Visual-Language Models with Mixture of Adapters for Multi-task Remote Sensing Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Shi, Z.; Zou, Z. High-resolution remote sensing image captioning based on structured attention. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, U.; Riaz, M.M.; Ghafoor, A. Transforming remote sensing images to textual descriptions. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2022, 108, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazi, Y.; Al Rahhal, M.M.; Mekhalfi, M.L.; Al Zuair, M.A.; Melgani, F. Bi-modal transformer-based approach for visual question answering in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Mou, L.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, X.X. Change detection meets visual question answering. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, T.; Bazi, Y.; Al Rahhal, M.M.; Mekhalfi, M.L.; Rangarajan, L.; Zuair, M. TextRS: Deep bidirectional triplet network for matching text to remote sensing images. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Rong, X.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Fu, K.; Sun, X. A lightweight multi-scale crossmodal text-image retrieval method in remote sensing. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahhal, M.M.A.; Bencherif, M.A.; Bazi, Y.; Alharbi, A.; Mekhalfi, M.L. Contrasting Dual Transformer Architectures for Multi-Modal Remote Sensing Image Retrieval. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rahhal, M.M.; Bazi, Y.; Alsharif, N.A.; Bashmal, L.; Alajlan, N.; Melgani, F. Multilanguage Transformer for Improved Text to Remote Sensing Image Retrieval. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2022, 15, 9115–9126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahhal, M.M.A.; Bazi, Y.; Abdullah, T.; Mekhalfi, M.L.; Zuair, M. Deep unsupervised embedding for remote sensing image retrieval using textual cues. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejiga, M.B.; Melgani, F.; Vascotto, A. Retro-remote sensing: Generating images from ancient texts. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2019, 12, 950–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Shi, Z. Text-to-remote-sensing-image generation with structured generative adversarial networks. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2021, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yu, W.; Ghamisi, P.; Kopp, M.; Hochreiter, S. Txt2Img-MHN: Remote sensing image generation from text using modern Hopfield networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.04441 2022.

- Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Lin, D.; Zhang, J. Generative Adversarial Networks for Zero-Shot Remote Sensing Scene Classification. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yu, Y.; Dong, J.; Li, C.; Su, D.; Chu, C.; Yu, D. Mm-llms: Recent advances in multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.13601 2024.

- Islam, R.; Moushi, O.M. Gpt-4o: The cutting-edge advancement in multimodal llm. Authorea Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; Millican, K.; et al. Gemini: a family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11805 2023.

- Anthropic. Introducing Claude 3.5 Sonnet. Tech. rep., Anthropic, 2024.

- Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, D.; Zhang, R.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Llava-onevision: Easy visual task transfer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.03326 2024.

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Savarese, S.; Hoi, S. Blip-2: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 19730–19742.

- Zhu, D.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Elhoseiny, M. Minigpt-4: Enhancing vision-language understanding with advanced large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.10592 2023.

- Li, K.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Luo, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Qiao, Y. Videochat: Chat-centric video understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.06355 2023.

- Maaz, M.; Rasheed, H.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S. Video-chatgpt: Towards detailed video understanding via large vision and language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05424 2023.

- Chu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J. Qwen-audio: Advancing universal audio understanding via unified large-scale audio-language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.07919 2023.

- Bazi, Y.; Bashmal, L.; Al Rahhal, M.M.; Ricci, R.; Melgani, F. Rs-llava: A large vision-language model for joint captioning and question answering in remote sensing imagery. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Hong, D.; Ge, S.; Luo, C.; Jiang, K.; Jin, H.; Wen, C. Rs-moe: A vision-language model with mixture of experts for remote sensing image captioning and visual question answering. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Roller, S.; Goyal, N.; Artetxe, M.; Chen, M.; Chen, S.; Dewan, C.; Diab, M.; Li, X.; Lin, X.V.; et al. Opt: Open pre-trained transformer language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01068 2022.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2020, 21, 5485–5551. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.W.; Hou, L.; Longpre, S.; Zoph, B.; Tay, Y.; Fedus, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Dehghani, M.; Brahma, S.; et al. Scaling instruction-finetuned language models. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024, 25, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, S.; Lin, X.V.; Pasunuru, R.; Mihaylov, T.; Simig, D.; Yu, P.; Shuster, K.; Wang, T.; Liu, Q.; Koura, P.S.; et al. Opt-iml: Scaling language model instruction meta learning through the lens of generalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.12017 2022.

- Alayrac, J.B.; Donahue, J.; Luc, P.; Miech, A.; Barr, I.; Hasson, Y.; Lenc, K.; Mensch, A.; Millican, K.; Reynolds, M.; et al. Flamingo: a visual language model for few-shot learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 23716–23736. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2014, pp. 740–755.

- Dai, W.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Tiong, A.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Fung, P.N.; Hoi, S. Instructblip: Towards general-purpose vision-language models with instruction tuning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 49250–49267. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, B.; Li, X.; Tao, D.; Lu, X. Deep semantic understanding of high resolution remote sensing image. In Proceedings of the 2016 International conference on computer, information and telecommunication systems (Cits). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–5.

- Yang, Y.; Newsam, S. Bag-of-visual-words and spatial extensions for land-use classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th SIGSPATIAL international conference on advances in geographic information systems, 2010, pp. 270–279.

- Zhang, F.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. Saliency-guided unsupervised feature learning for scene classification. IEEE transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2014, 53, 2175–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, B.; Zheng, X.; Li, X. Exploring models and data for remote sensing image caption generation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 56, 2183–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Huang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Z. NWPU-captions dataset and MLCA-net for remote sensing image captioning. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Bosma, M.; Zhao, V.Y.; Guu, K.; Yu, A.W.; Lester, B.; Du, N.; Dai, A.M.; Le, Q.V. Finetuned language models are zero-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.01652 2021.

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, J.; Xia, J.; Wei, G.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, T.; Song, R. What matters in training a gpt4-style language model with multimodal inputs? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2024, pp. 7930–7957.

- Du, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhou, K.; Zhao, W.X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Cai, M.; Song, R.; Wen, J.R. What makes for good visual instructions? synthesizing complex visual reasoning instructions for visual instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.01487 2023.

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.09388 2025.

- Zhai, X.; Mustafa, B.; Kolesnikov, A.; Beyer, L. Sigmoid loss for language image pre-training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2023, pp. 11975–11986.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Lee, Y.J. Improved baselines with visual instruction tuning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2024, pp. 26296–26306.

- Team, Q. Qwen2 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.10671 2024.

- Yin, S.; Fu, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, K.; Sun, X.; Xu, T.; Chen, E. A survey on multimodal large language models. National Science Review 2024, 11, nwae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yuan, A.; Lu, X. Multi-modal gated recurrent units for image description. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2018, 77, 29847–29869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lu, X.; Zheng, X.; Li, X. Semantic descriptions of high-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2019, 16, 1274–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, B.; Zheng, X. Sound active attention framework for remote sensing image captioning. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 58, 1985–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ba, J.; Kiros, R.; Cho, K.; Courville, A.; Salakhudinov, R.; Zemel, R.; Bengio, Y. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2015, pp. 2048–2057.

- Sumbul, G.; Nayak, S.; Demir, B. SD-RSIC: Summarization-driven deep remote sensing image captioning. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 59, 6922–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zheng, X.; Qu, B.; Lu, X. Retrieval topic recurrent memory network for remote sensing image captioning. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2020, 13, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, G.; Melgani, F. A novel SVM-based decoder for remote sensing image captioning. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, G.; Scuccato, G.; Melgani, F. Improving Image Captioning Systems with Post-Processing Strategies. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.D.; Magalhães, J.; Tuia, D.; Martins, B. Large language models for captioning and retrieving remote sensing images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06475 2024.

| Method | BLEU-1 | BLEU-2 | BLEU-3 | BLEU-4 | METEOR | ROUGE_L | CIDEr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLIP2-13B [67] | 54.51 | 42.42 | 34.64 | 28.17 | 27.54 | 24.38 | 105.51 |

| MiniGPT4-13B [68] | 68.49 | 59.31 | 43.22 | 39.78 | 31.70 | 30.95 | 120.33 |

| InstructBLIP-13B [80] | 63.71 | 50.76 | 49.35 | 40.50 | 30.58 | 27.15 | 121.91 |

| RSGPT-13B [44] | 77.05 | 62.18 | 48.25 | 40.34 | 37.41 | 33.26 | 149.32 |

| RS-MoE-1B | 57.36 | 42.25 | 22.14 | 20.54 | 32.36 | 25.98 | 109.37 |

| MM-RSTraj-0.5B | 55.86 | 40.12 | 21.62 | 19.45 | 26.49 | 21.76 | 119.20 |

| RS-MoE-7B | 82.13 | 65.44 | 51.93 | 42.55 | 40.28 | 35.72 | 158.36 |

| MM-RSTraj-7B | 69.64 | 57.82 | 43.88 | 36.54 | 30.85 | 27.98 | 131.17 |

| Method | BLEU-1 | BLEU-2 | BLEU-3 | BLEU-4 | METEOR | ROUGE_L | CIDEr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VLAD + RNN [84] | 63.11 | 51.93 | 46.06 | 42.09 | 29.71 | 58.78 | 200.66 |

| VLAD + LSTM [84] | 70.16 | 60.85 | 54.96 | 50.30 | 34.64 | 65.20 | 231.31 |

| mRNN [81] | 60.10 | 50.70 | 32.80 | 20.80 | 19.30 | - | 214.00 |

| mLSTM [81] | 63.50 | 53.20 | 37.50 | 21.30 | 20.30 | - | 222.50 |

| mGRU [95] | 42.56 | 29.99 | 22.91 | 17.98 | 19.41 | 37.97 | 124.82 |

| mGRU embedword [95] | 75.74 | 69.83 | 64.51 | 59.98 | 36.85 | 66.74 | 279.24 |

| CSMLF [96] | 37.71 | 14.85 | 7.63 | 5.05 | 9.44 | 29.86 | 13.51 |

| SAA [97] | 79.62 | 74.01 | 69.09 | 64.77 | 38.59 | 69.42 | 294.51 |

| Soft-attention [98] | 74.54 | 65.45 | 58.55 | 52.50 | 38.86 | 72.37 | 261.24 |

| Hard-attention [98] | 81.57 | 73.12 | 67.02 | 61.82 | 42.63 | 76.98 | 299.47 |

| SD-RSIC [99] | 74.80 | 66.40 | 59.80 | 53.80 | 39.00 | 69.50 | 213.20 |

| RTRMN (semantic) [100] | 55.26 | 45.15 | 39.62 | 35.87 | 25.98 | 55.38 | 180.25 |

| RTRMN (statistical) [100] | 80.28 | 73.22 | 68.21 | 63.93 | 42.58 | 77.26 | 312.70 |

| SVM-D BOW [101] | 76.35 | 66.64 | 58.69 | 51.95 | 36.54 | 68.01 | 271.42 |

| SVM-D CONC [101] | 76.53 | 69.47 | 64.17 | 59.42 | 37.02 | 68.77 | 292.28 |

| Post-processing [102] | 79.73 | 72.98 | 67.44 | 62.62 | 40.80 | 74.06 | 309.64 |

| RS-CapRet-7B [103] | 84.30 | 77.90 | 72.20 | 67.00 | 47.20 | 81.70 | 354.80 |

| RSGPT-13B [44] | 86.12 | 79.14 | 72.31 | 65.74 | 42.21 | 78.34 | 333.23 |

| RS-LLaVA-13B [72] | 90.00 | 84.88 | 80.30 | 76.03 | 49.21 | 85.78 | 355.61 |

| RS-MoE-7B | 94.81 | 87.09 | 79.57 | 72.34 | 66.97 | 62.74 | 396.46 |

| MM-RSTraj-7B (ours) | 91.14 | 85.10 | 77.06 | 71.53 | 64.10 | 61.87 | 398.10 |

| Method | Presence | Quantity | Color | Absolute pos. | Relative pos. | Area comp. | Road dir. | Image | Reasoning | Scene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLIP2 | 60.41 | 26.02 | 43.24 | 7.69 | 13.16 | 58.14 | 33.33 | 74.42 | 47.50 | 43.24 |

| MiniGPT4 | 29.70 | 9.76 | 31.53 | 1.54 | 1.32 | 16.28 | 0.00 | 34.88 | 17.50 | 24.32 |

| InstructBLIP | 76.14 | 21.95 | 45.05 | 12.31 | 10.53 | 69.77 | 0.00 | 81.40 | 57.50 | 45.95 |

| RSGPT | 81.22 | 39.02 | 54.05 | 38.46 | 35.53 | 62.79 | 66.67 | 93.02 | 70.00 | 89.19 |

| RS-MOE | 83.16 | 32.77 | 71.92 | 43.95 | 45.00 | 63.41 | 0.00 | 77.89 | 74.07 | 93.18 |

| MM-RSTraj | 87.31 | 33.06 | 77.59 | 68.13 | 47.50 | 81.25 | 0.00 | 61.46 | 71.24 | 93.331 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).