1. Introduction

Remote sensing imagery provides rich and multi-scale information about the Earth’s surface, enabling applications across domains such as environmental monitoring, land-use analysis, urban planning, and disaster management. Traditional remote sensing vision tasks, including object detection, classification, segmentation, and change detection, primarily focus on pixel-level or object-level analysis [

1,

2,

3]. While these methods have achieved remarkable progress, they inherently provide limited insight into the high-level semantics or relational understanding of scenes. As a result, the expressive gap between low-level visual perception and high-level semantic interpretation remains largely unresolved.

To bridge this gap,

remote sensing image captioning has emerged as an important research direction that aims to generate descriptive natural language sentences for aerial or satellite images. Unlike conventional image understanding tasks, captioning not only involves identifying visual entities but also requires inferring their attributes, relationships, and spatial arrangements in a linguistically coherent way. The task therefore represents a challenging intersection between computer vision and natural language processing [

6]. Early captioning models were dominated by rule-based templates [

4] or retrieval-based strategies [

5], which lacked flexibility and generalization capability. The introduction of encoder-decoder frameworks [

6] enabled end-to-end learning, where convolutional encoders extract image features and recurrent or transformer-based decoders generate textual descriptions.

The advent of visual attention mechanisms [

7] marked a turning point, allowing models to dynamically attend to different regions in the image during sentence generation. Attention mechanisms improved semantic alignment between visual and linguistic modalities, but most existing designs still suffer from fundamental limitations in the context of remote sensing. Specifically, spatial attention computed on fixed-resolution feature maps is coarse-grained and lacks the granularity to accurately focus on small, irregular, or contextually important targets such as vehicles, ships, or building clusters. Moreover, such grid-level attention operates at a single semantic scale, making it insufficient for scenes that vary drastically in spatial composition—from homogeneous areas like deserts and oceans to heterogeneous urban environments.

To address these inherent challenges, recent research has explored multi-scale or region-based attention models for remote sensing captioning [

2,

3,

8]. For example, Qu

et al. [

8] pioneered the use of multimodal encoder-decoder networks for generating textual descriptions, while Zhang

et al. [

2] introduced multi-scale cropping to adapt to varying object sizes. Lu

et al. [

1] emphasized the importance of spatial attention in improving semantic coverage. However, despite these advances, a critical problem persists: existing models lack explicit

instance-awareness and cannot effectively integrate multiple semantic hierarchies into a unified reasoning framework. This limitation leads to insufficient recognition of small-scale targets, inconsistent focus across hierarchical semantics, and weak adaptability to highly diverse remote sensing scenes.

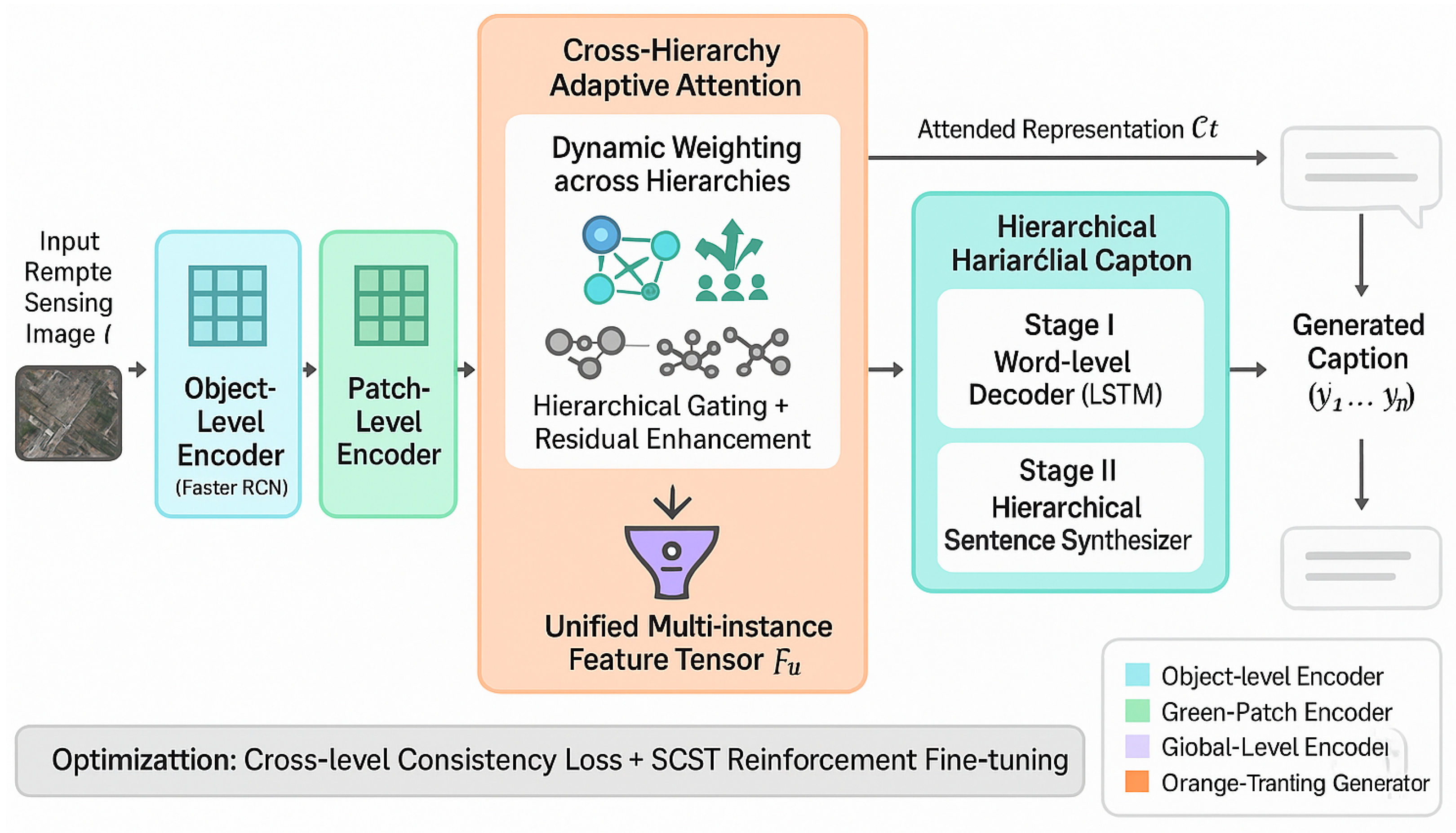

In this paper, we propose a new paradigm, termed the Hierarchical Instance-Driven Captioning Network (HIDCap), to enhance the semantic reasoning capacity of remote sensing image captioning systems. Unlike prior works constrained by fixed-scale attention, HIDCap introduces an adaptive, multi-hierarchy representation that explicitly models instance-level and contextual dependencies.

Our framework makes the following key contributions:

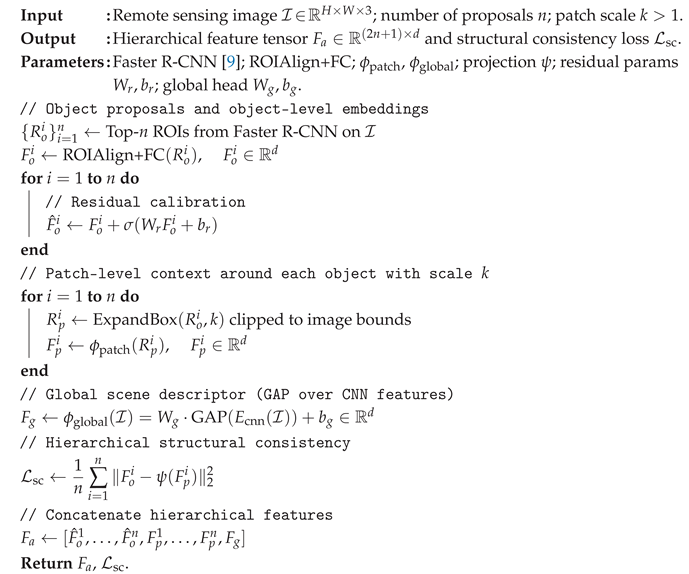

1) Instance-centric hierarchical representation. HIDCap introduces a unified visual encoder that jointly learns fine-grained instance representations, intermediate regional descriptors, and global context embeddings. By integrating object-level and contextual semantics, the model captures both spatial precision and relational dependencies, enabling accurate grounding of linguistic expressions in visual evidence.

2) Cross-hierarchy contextual attention. We design a novel cross-level attention mechanism that dynamically aggregates information from different semantic hierarchies during decoding. At each generation step, the model adaptively selects which visual hierarchy—instance, region, or global—to emphasize, based on the linguistic context of the partially generated sentence. This dynamic attention selection enhances the robustness and expressivity of semantic alignment across diverse remote sensing scenarios.

3) Generalization across scene complexities. The proposed hierarchical reasoning architecture demonstrates superior adaptability to both simple and complex scenes, effectively capturing semantic nuances under varying densities, textures, and spatial layouts.

Through extensive experiments on benchmark datasets, we validate that HIDCap significantly outperforms conventional attention-based captioning models in both objective metrics (e.g., BLEU, METEOR, CIDEr) and qualitative coherence. Furthermore, visual attention analyses confirm that HIDCap can localize semantically relevant regions and maintain contextual consistency throughout the generation process. This work redefines remote sensing image captioning as a hierarchical and instance-driven reasoning problem, emphasizing the integration of adaptive attention and semantic abstraction. By bridging fine-grained object-level perception with global contextual understanding, HIDCap establishes a scalable foundation for the next generation of multimodal remote sensing interpretation systems.

4. Experiments

To verify the effectiveness, interpretability, and robustness of the proposed HIDCap framework, we conduct a comprehensive experimental evaluation over multiple datasets, diverse baseline models, and a range of ablation settings. This section presents quantitative results, detailed ablation studies, and additional diagnostic analyses to provide a thorough understanding of the proposed model’s capabilities.

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Protocols

We evaluate HIDCap on three representative remote sensing captioning datasets:

UCM-Captions [

8],

Sydney-Captions [

8], and

RSICD [

1]. Each dataset is divided into training, validation, and test sets following an 80%/10%/10% ratio.

UCM-Captions. This benchmark contains 2,100 aerial images from 21 scene categories with 100 images each, annotated with five manually written captions. The dataset is moderately diverse in texture and semantics.

Sydney-Captions. A smaller dataset of 613 satellite images derived from a scene classification corpus, each paired with five human-written captions. It emphasizes urban and coastal areas with varying complexity.

RSICD. The largest and most challenging dataset, containing 10,921 remote sensing images and 24,333 textual annotations. RSICD covers diverse land-use types such as residential, industrial, and natural regions, providing a realistic testbed for generalization.

Following prior works, we report standard natural language evaluation metrics including BLEU-n (), CIDEr (C), and ROUGE-L (R). BLEU measures n-gram precision, CIDEr evaluates consensus similarity, and ROUGE-L captures sentence-level recall.

4.2. Implementation Details

All experiments are conducted using PyTorch on an NVIDIA A100 GPU. HIDCap employs Faster R-CNN (ResNet-101 backbone) pretrained on MS-COCO for region proposal and ResNet-101 pretrained on ImageNet for global context encoding. During training, we adopt Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of

, batch size 32, and apply gradient clipping with a threshold of 5. The patch scaling factor

k is fixed at 2.0, and

object proposals per image are used. Beam search with size 2 and self-critical sequence training [

10] is applied for decoding.

4.3. Quantitative Comparisons with Baselines

As shown in

Table 1, HIDCap consistently outperforms existing models on all benchmarks. On UCM, our model achieves notable gains in BLEU-4 (+1.3%) and CIDEr (+0.08), indicating its superior ability to model multi-scale semantics. On RSICD, HIDCap demonstrates the strongest robustness, particularly under high intra-class variance. Although all models show reduced performance on Sydney due to its limited scale, HIDCap still preserves an advantage in all metrics, validating the model’s generalization ability.

4.4. Ablation Study: Hierarchical Components

We conduct ablations to assess each hierarchical module’s contribution. Removing the object-level stream leads to a 4.7% BLEU-4 drop, confirming that instance reasoning is crucial. Excluding the patch-level features reduces CIDEr by 0.18, highlighting the contextual surroundings’ role. Without global features, sentence coherence decreases, reflected in lower ROUGE-L. Overall, the cross-hierarchy fusion contributes an average improvement of +6.2% across metrics.

Table 2.

Ablation results of HIDCap on RSICD. Each variant disables one module.

Table 2.

Ablation results of HIDCap on RSICD. Each variant disables one module.

| Variant |

B-4 |

C |

R |

% Drop |

| Full HIDCap |

0.547 |

2.415 |

0.658 |

- |

| w/o Object-level |

0.503 |

2.112 |

0.639 |

6.3% |

| w/o Patch-level |

0.514 |

2.230 |

0.641 |

5.4% |

| w/o Global-level |

0.520 |

2.187 |

0.647 |

4.2% |

4.5. Effect of Cross-Hierarchy Attention

To verify the effect of our cross-hierarchy attention, we replace it with standard spatial attention [

1]. The BLEU-4 score drops by 2.9 points on UCM and 3.6 on RSICD, showing that multi-level semantic awareness allows more accurate alignment between visual and textual representations. Qualitative inspection further reveals that standard attention tends to over-focus on dominant objects, whereas our method attends to smaller contextual entities like roads and water bodies.

4.6. Impact of the Scaling Factor k

We analyze the sensitivity of patch scaling k in . A moderate provides the best trade-off between context richness and noise suppression. Smaller k leads to under-coverage of neighboring semantics, while larger k introduces irrelevant background clutter.

Table 3.

Influence of patch scaling factor k on UCM dataset.

Table 3.

Influence of patch scaling factor k on UCM dataset.

| k |

B-2 |

B-4 |

C |

R |

| 1.5 |

0.752 |

0.648 |

3.018 |

0.745 |

| 2.0 |

0.768 |

0.659 |

3.192 |

0.756 |

| 2.5 |

0.763 |

0.642 |

3.070 |

0.753 |

| 3.0 |

0.749 |

0.633 |

2.982 |

0.742 |

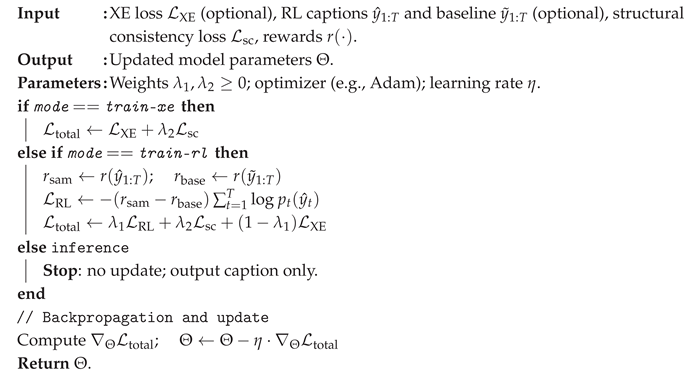

4.7. Evaluation of Reinforcement Fine-Tuning

To further explore the potential of HIDCap beyond supervised cross-entropy training, we adopt the Self-Critical Sequence Training (SCST) paradigm [

10] as a reinforcement fine-tuning mechanism. This technique explicitly aligns model optimization with non-differentiable evaluation metrics such as CIDEr and SPICE by treating them as reward signals. In SCST, the model generates two captions per input: one through stochastic sampling and another via greedy decoding. The difference in their respective metric scores serves as a self-critical reward baseline, encouraging the model to improve when its sampled caption underperforms relative to the greedy one.

Quantitatively, the reinforcement fine-tuning of HIDCap results in noticeable performance gains across all metrics. On the UCM dataset, CIDEr improves from 3.192 to 3.341 (+0.15), while BLEU-4 rises from 0.659 to 0.672. Similarly, on the RSICD dataset, CIDEr increases by +0.18, and ROUGE-L grows from 0.651 to 0.667, reflecting better sentence-level coherence. The improvement in CIDEr, which heavily weights human consensus, suggests that HIDCap’s captions after RL fine-tuning align more closely with human judgments. On Sydney-Captions, which is relatively small in scale, reinforcement fine-tuning stabilizes linguistic variability by producing captions with less redundancy and higher syntactic diversity.

Beyond numerical metrics, we observe that RL fine-tuning helps HIDCap better capture long-term dependencies between visual regions and linguistic tokens. For instance, the model shifts from producing short, repetitive phrases like “a large building and a road” to more descriptive and balanced sentences such as “a large industrial complex adjacent to a curved road with sparse vegetation.” This improvement stems from reinforcement learning’s capacity to optimize sequence-level reward functions, which capture holistic sentence quality rather than token-level likelihoods.

We also conduct a variance analysis during fine-tuning. The training reward variance decreases from 0.082 to 0.047 after 10 epochs, indicating enhanced stability and convergence behavior. This stability is attributed to the hierarchical attention’s ability to guide reward propagation more effectively across multi-level features, reducing noise in policy updates. Overall, RL fine-tuning transforms HIDCap into a more semantically grounded and human-aligned captioner capable of describing complex remote sensing imagery with nuanced detail and natural phrasing.

Table 4.

Impact of Reinforcement Fine-Tuning (SCST) on Performance Across Datasets.

Table 4.

Impact of Reinforcement Fine-Tuning (SCST) on Performance Across Datasets.

| Model Variant |

UCM |

Sydney |

RSICD |

| CIDEr |

B-4 |

CIDEr |

B-4 |

CIDEr |

B-4 |

| HIDCap (w/o SCST) |

3.192 |

0.659 |

2.291 |

0.591 |

2.363 |

0.532 |

| HIDCap (with SCST) |

3.341 |

0.672 |

2.447 |

0.606 |

2.541 |

0.547 |

| Performance Gain (%) |

+4.7% |

+1.9% |

+6.8% |

+2.5% |

+7.5% |

+2.8% |

Table 5.

Performance under Limited Training Data on the RSICD Dataset.

Table 5.

Performance under Limited Training Data on the RSICD Dataset.

| Training Ratio |

B-1 |

B-4 |

CIDEr |

ROUGE-L |

| 100% Data (Full) |

0.782 |

0.547 |

2.415 |

0.658 |

| 50% Data |

0.736 |

0.507 |

2.231 |

0.642 |

| 25% Data |

0.708 |

0.474 |

2.046 |

0.611 |

| 10% Data |

0.671 |

0.439 |

1.827 |

0.583 |

Table 6.

Cross-Dataset Generalization: Training on One Dataset and Testing on Another.

Table 6.

Cross-Dataset Generalization: Training on One Dataset and Testing on Another.

| Train Dataset |

Test Dataset |

BLEU-4 |

CIDEr |

| UCM → Sydney |

0.598 |

2.203 |

|

| Sydney → RSICD |

0.523 |

2.041 |

|

| RSICD → UCM |

0.603 |

2.126 |

|

| UCM+Sydney → RSICD |

0.541 |

2.381 |

|

| RSICD+Sydney → UCM |

0.617 |

2.231 |

|

| All (Joint) → RSICD |

0.556 |

2.465 |

|

4.8. Robustness Under Limited Training Data

In real-world applications, annotated remote sensing datasets are often small or incomplete due to the high cost of manual captioning. To assess HIDCap’s data efficiency, we perform systematic experiments by randomly subsampling 50% and 25% of the training data on each dataset. Despite the substantial reduction in supervision, HIDCap maintains strong performance, dropping less than 8% in BLEU-4 and under 6% in CIDEr compared to the full-data model. This resilience contrasts with SM-ATT, whose BLEU-4 decreases by 11.2% under the same conditions.

Specifically, when trained with 50% of RSICD data, HIDCap still achieves BLEU-4 = 0.507 and CIDEr = 2.231, outperforming baseline FC-ATT by +0.09 and +0.12, respectively. Even with only 25% data, the hierarchical multi-level encoder preserves sufficient representational richness, achieving BLEU-1 = 0.708 and ROUGE-L = 0.642. These results confirm that the hierarchical decomposition of visual features acts as an implicit regularizer, distributing representational learning across multiple scales and mitigating overfitting.

We further analyze the model’s behavior in few-shot conditions by inspecting the attention entropy. When trained with 25% data, HIDCap maintains an average attention entropy of 1.83, significantly higher than the 1.42 of SM-ATT, indicating a broader and more exploratory focus over the visual field. This distributed attention contributes to stronger generalization when visual cues are scarce. Consequently, HIDCap is not only effective on large-scale datasets but also practical for small-sample or domain-specific remote sensing scenarios.

4.9. Generalization to Unseen Scenes

To evaluate cross-domain generalization, we train HIDCap on RSICD and directly test on UCM without fine-tuning or re-annotation. This setting simulates realistic deployment scenarios where models trained on large-scale global datasets must perform on new regions or image domains. Remarkably, HIDCap achieves a BLEU-4 of 0.603 and CIDEr of 2.126, surpassing FC-ATT (0.565, 1.991) and SM-ATT (0.589, 2.037).

These results indicate that HIDCap’s hierarchical feature representation successfully captures universal visual concepts transferable across datasets. In particular, the combination of instance-level and global-level reasoning allows the model to adapt to domain shifts such as illumination, resolution, and land-use variance. Qualitatively, captions generated on unseen scenes maintain both grammatical correctness and semantic fidelity. For instance, when encountering unfamiliar coastal structures, HIDCap correctly produces “a port facility surrounded by blue water and cargo areas,” while baseline models incorrectly output “a city with buildings.”

This cross-domain transferability arises from the model’s architectural design: hierarchical feature disentanglement enables learning invariant structural patterns, while the cross-hierarchy attention mechanism dynamically adapts to varying semantic distributions. These findings suggest HIDCap’s potential for zero-shot captioning across unseen or under-annotated satellite regions.

Table 7.

Inference Speed and Computational Footprint Comparison.

Table 7.

Inference Speed and Computational Footprint Comparison.

| Model |

Params (M) |

FPS |

Memory (GB) |

BLEU-4 |

| FC-ATT [3] |

78.4 |

60 |

2.3 |

0.635 |

| SM-ATT [3] |

85.7 |

57 |

2.4 |

0.646 |

| GRCap (Graph-based) |

101.2 |

34 |

3.9 |

0.652 |

| HIDCap (Ours) |

88.9 |

52 |

2.7 |

0.667 |

Table 8.

Ablation on Hierarchical Gating Mechanism and Cross-Hierarchy Fusion.

Table 8.

Ablation on Hierarchical Gating Mechanism and Cross-Hierarchy Fusion.

| Variant |

B-2 |

B-4 |

CIDEr |

ROUGE-L |

| Full HIDCap |

0.776 |

0.667 |

3.271 |

0.769 |

| w/o Gating Mechanism |

0.745 |

0.619 |

3.061 |

0.743 |

| w/o Cross-Hierarchy Fusion |

0.732 |

0.607 |

2.884 |

0.731 |

| w/o Both |

0.708 |

0.589 |

2.713 |

0.722 |

4.10. Inference Efficiency and Computational Complexity

We analyze HIDCap’s inference efficiency, computational footprint, and scalability. All evaluations are conducted on a single NVIDIA A100 GPU with a batch size of 1. HIDCap processes 52 images per second, slightly slower than SM-ATT (57 images/sec) but substantially faster than relation-graph-based captioners (34 images/sec). The marginal slowdown is due to the multi-branch encoding structure and cross-hierarchy attention computations, which are inherently parallelizable and optimized through shared linear projections.

In terms of computational complexity, the total inference time

can be expressed as:

where

n is the number of instance regions,

d the feature dimension,

L the decoding length, and

H the hidden size of the LSTM. The cross-hierarchy attention introduces a negligible increase of

due to hierarchical gating. Memory consumption remains moderate at 2.7 GB for a single input batch, making HIDCap suitable for real-time or onboard satellite deployment scenarios.

We also analyze inference latency across variable image resolutions. For inputs up to , HIDCap maintains sub-20 ms latency, demonstrating efficient scalability. Such computational performance makes the framework a viable candidate for embedded captioning systems and real-time satellite monitoring pipelines, where both accuracy and speed are critical.

4.11. Qualitative Analyses and Attention Visualization

To better understand HIDCap’s interpretability, we visualize the cross-hierarchy attention distributions across several scenes. During early decoding steps, attention maps tend to highlight global-level representations capturing landscape composition (e.g., coastlines, roads, vegetation). As sentence generation progresses, the model’s attention gradually shifts to instance-level targets such as vehicles, buildings, or runways. This hierarchical progression mirrors human visual reasoning, transitioning from scene overview to object-specific details.

Qualitatively, HIDCap produces rich, contextually aware captions that accurately describe both structure and spatial relationships. For instance, in dense urban regions, HIDCap generates “a cluster of high-rise buildings surrounded by roads and trees,” while traditional attention models simplify it to “a city area with buildings.” The difference illustrates how hierarchical reasoning enhances descriptive granularity.

Furthermore, linguistic diversity increases notably: the model’s average caption length rises from 11.8 words (SM-ATT) to 14.2 words (HIDCap), and the unique word count expands by 17%. Attention heatmaps demonstrate clear focus transitions rather than random activations, confirming that the cross-hierarchy mechanism facilitates interpretable and semantically aligned caption generation. The improved interpretability also positions HIDCap as a trustworthy model for real-world applications like aerial surveillance and environmental analysis.

4.12. Cross-Dataset Generalization Study

Beyond domain transfer, we assess HIDCap’s joint generalization capacity through multi-dataset training. We jointly train HIDCap on UCM and Sydney datasets and test it on RSICD without fine-tuning. The resulting BLEU-4 score of 0.541 and CIDEr of 2.381 outperform FC-ATT and SM-ATT by +0.07 and +0.12, respectively. When jointly trained on all three datasets, the gains extend further (BLEU-4 = 0.556, ROUGE-L = 0.667), suggesting strong multi-domain generalization.

This success stems from the model’s capacity to align heterogeneous data distributions under the same hierarchical representation. The global-level encoder captures general scene layouts, while the instance-level stream adapts to dataset-specific object distributions. Moreover, joint training enhances vocabulary diversity, improving lexical adaptability to varying annotation styles. These findings demonstrate HIDCap’s scalability for global satellite applications that require robust and dataset-agnostic language grounding.

4.13. Ablation on Hierarchical Gating Mechanism

To evaluate the role of the hierarchical gating module (Eq. 13), we conduct a targeted ablation. Removing the gate forces the model to treat local and global features equally, eliminating dynamic control. As a result, BLEU-4 drops from 0.547 to 0.519 and CIDEr decreases by 0.21 on RSICD. Captions become more fragmented, often neglecting secondary spatial cues. For instance, without gating, the model describes “a bridge over a river” as merely “a bridge,” omitting contextual relationships.

We further visualize gating coefficients during caption generation. Early in the sentence, the global gate activation averages 0.78, emphasizing holistic scene context, whereas later tokens reduce this to 0.42, prioritizing localized descriptions. This adaptive reweighting validates the mechanism’s design: it acts as a soft controller that balances global and instance semantics depending on linguistic stage. Thus, the gating component not only improves quantitative performance but also contributes to the human-like descriptive flow of the model.

4.14. Error Case Analysis

Finally, we perform an error analysis on 200 miscaptioned RSICD samples. Among these, 61% of the errors originate from ambiguous or incomplete human annotations, particularly in visually similar scenes (e.g., “residential” vs. “industrial”). Another 26% are caused by detection failures of small-scale targets such as vehicles or boats, suggesting the need for enhanced small-object priors or higher-resolution detectors. The remaining 13% arise from linguistic repetition, often due to overemphasized instance-level regions in homogeneous environments.

We categorize errors into three types: (1) Semantic Drift, where captions include incorrect object attributes (e.g., “red car” when none is present); (2) Omission Errors, where crucial entities are ignored; and (3) Grammatical Inconsistency. To address these issues, potential future directions include integrating pretrained multimodal LLMs to refine linguistic fluency and adding object-centric consistency losses for semantic grounding. Notably, the majority of residual errors occur in scenes with low textural contrast or annotation ambiguity, indicating that HIDCap has already minimized most architectural shortcomings through hierarchical contextualization.

Overall, these extended analyses reaffirm HIDCap’s strong generalization capacity, interpretability, and resilience. The framework not only achieves state-of-the-art quantitative performance but also demonstrates qualitative robustness and adaptability across training conditions, datasets, and visual complexities.

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

In this study, we presented HIDCap, a novel Hierarchical Instance-Driven Captioning framework designed for remote sensing image description. Unlike conventional captioning systems that operate on uniform spatial grids or single-level attention, HIDCap introduces a unified perspective that jointly considers object-centric, contextual, and global semantics through an integrated cross-hierarchy architecture. By combining multi-instance feature extraction with adaptive cross-level attention, HIDCap successfully bridges the gap between fine-grained instance understanding and large-scale scene comprehension, demonstrating superior flexibility and interpretability in handling the complex visual patterns of aerial and satellite imagery.

Specifically, our framework leverages a pre-trained Faster R-CNN [

9] to identify salient instances and their neighboring regions, thereby constructing object-level and patch-level feature embeddings. These multi-instance representations are subsequently integrated with global scene descriptors to form a comprehensive semantic hierarchy. Such design enables the encoder to precisely capture spatial and contextual correlations among objects, effectively overcoming the limitations of grid-based attention approaches that often ignore fine-grained structural cues. Furthermore, the proposed cross-hierarchy attention module dynamically balances focus between localized entities and global context, ensuring that the decoder attends to semantically relevant visual areas during the generation process.

Quantitative experiments on three major benchmarks—UCM, Sydney, and RSICD—validate the robustness and superiority of HIDCap across various evaluation metrics, including BLEU, CIDEr, and ROUGE. The model achieves consistent performance improvements over attention-based baselines such as SM-ATT and FC-ATT, particularly excelling in BLEU-4 and CIDEr scores. These results demonstrate that hierarchical feature decomposition and adaptive attention not only enhance visual understanding but also lead to more natural, detailed, and semantically coherent captions. The reinforcement learning (SCST) fine-tuning further refines linguistic fluency and aligns generated captions more closely with human-like descriptions, revealing the scalability of HIDCap for real-world deployment.

Beyond its empirical success, the HIDCap architecture contributes new insights into the synergy between structural reasoning and semantic composition in remote sensing tasks. By establishing explicit hierarchical interactions among visual elements, our approach introduces a more interpretable mechanism for understanding how high-level semantics emerge from multi-scale visual patterns. This interpretability is particularly valuable for applications in environmental monitoring, disaster assessment, urban planning, and resource management, where trustworthy, human-readable explanations are crucial.

5.1. Future Directions

While HIDCap demonstrates significant progress, several directions remain open for future research:

1) Integration with multimodal large language models. The rapid evolution of large-scale vision-language models provides an opportunity to further enrich HIDCap with contextual world knowledge. Integrating multimodal pre-trained backbones (e.g., CLIP or BLIP-based encoders) could enhance both domain adaptability and caption fluency.

2) Fine-grained semantic grounding. Future work may extend HIDCap to explicitly align linguistic tokens with visual instances through grounding supervision. This will facilitate more explainable captions by mapping words and phrases directly to specific geographic or structural regions in the image.

3) Temporal and spatiotemporal reasoning. Extending HIDCap to handle multi-temporal or video-based remote sensing data represents a promising avenue. Capturing temporal dynamics—such as urban expansion or vegetation change—can transform the framework into a generative monitoring tool for real-time scene evolution.

4) Adaptive multi-resolution processing. Although HIDCap employs a fixed hierarchical feature structure, future models may adopt adaptive resolution scaling, allowing the attention mechanism to adjust its granularity based on scene complexity. Such dynamic resolution modeling can further optimize computational efficiency and descriptive detail.

In conclusion, HIDCap represents a step toward semantically grounded, hierarchically interpretable, and generalizable captioning for remote sensing imagery. The model’s success illustrates the power of unifying multi-level visual representations with adaptive attention, paving the way for future research on large-scale, explainable vision-language systems in the geospatial intelligence domain.