1. Introduction

With revolutionary advancements in aerospace and sensor technologies, multimodal remote sensing data acquisition capabilities have achieved transformative breakthroughs. Researchers now have unprecedented access to multidimensional Earth observation systems comprising optical imagery, multispectral/hyperspectral data, Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) [

1,

2,

3]. These cutting-edge datasets, featuring sub-meter spatial resolution, nanometer-level spectral resolution, and hourly temporal resolution, not only accurately document spatiotemporal evolution patterns of terrestrial ecosystems but also reveal profound spatial imprints of human activities [

1,

4,

5]. Effectively mining valuable information from massive heterogeneous datasets has emerged as a critical scientific challenge in intelligent remote sensing interpretation.

The synergistic fusion of multisource remote sensing data establishes a new paradigm for Earth system science research. By integrating complementary sensor advantages, researchers can construct multidimensional feature spaces to enhance surface characterization capabilities. This paradigm demonstrates remarkable efficacy in change detection: SAR’s all-weather observation combined with optical spectral information enables precise urban expansion monitoring [

1,

3,

4]; hyperspectral-LiDAR fusion elevates land cover classification accuracy beyond

[

6,

7]; while multi-temporal multi-angle image integration effectively resolves camouflage recognition challenges in military applications [

8,

9]. These breakthroughs propel the paradigm shift from visual to intelligent interpretation in remote sensing [

10,

11,

12,

13].

As the core technology for deep image understanding, semantic segmentation has gained significant attention in remote sensing. Through pixel-level classification generating semantic thematic maps, it supports decision-making in digital twin cities, flood assessment, and precision agriculture. However, unique remote sensing characteristics—sub-pixel features (e.g., small-scale structures), inter-class similarity (e.g., vegetation types), and target occlusion—pose formidable challenges to conventional segmentation algorithms [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Particularly in high-density urban areas, traditional CNNs (i.e., Convolutional Neural Networks) struggle to distinguish occluded boundaries due to limited receptive fields, leading to significant accuracy degradation. These challenges drive research on novel segmentation frameworks tailored for remote sensing characteristics.

While CNN-based models excel in feature extraction, their hierarchical downsampling mechanisms progressively discard small-scale features. For instance, 3-5 pixel-wide road markings in high-resolution urban imagery degrade to sub-pixel levels after four downsampling operations, complicating network recognition. Furthermore, weakened inter-class heterogeneity (e.g., vegetation spectral confusion, similar reflectance between buildings and pavements) undermines CNN’s reliance on local textures for establishing discriminative boundaries [

15,

18,

19,

20]. Combined with vertical occlusion effects, these limitations exacerbate pixel-level semantic ambiguity, highlighting the inadequacy of single-scale feature extraction.

To tackle these challenges, we focus on developing multi-granularity feature fusion systems that combine local details with global context. The Swin Transformer [

21] introduces hierarchical window attention mechanisms alongside CNN-style feature learning. It features: 1) Progressive feature pyramids achieved through patch merging, 2) Window-based Multi-head Self-Attention (W-MSA) that reduces computational complexity, and 3) Shifted Window (SW-MSA) mechanisms that address limitations in the visual field. However, the limitations of Transformers in weak boundaries (such as water-wetland transitions) and high-frequency textures (like farmland furrows) highlight the need for the local inductive bias of CNNs, which has prompted research into hybrid architectures [

22]. Dual-branch networks that combine CNN and Transformer pathways, along with channel-spatial attention mechanisms, show superior multimodal fusion capabilities. Building on these foundations, this paper proposes PLGTransformer—a dual-encoder enhanced hybrid architecture that innovatively integrates local perception, global modeling, and graph-structured reasoning. To summarize, our main contributions include:

Heterogeneous Multi-branch Local Feature Extraction: The proposed model establishes a multimodal local feature extraction network through three parallel convolutional branches. Specifically, the feature extractors perform diverse processing operations within different architectures to better capture comprehensive representations such as high-frequency textures, mesoscale structures, and detail representations for the remote sensing images. By doing this, the aligned and concatenated composite features preserve both sub-pixel edge responses and regional semantic correlations, effectively addressing feature representation limitations of single convolutional kernels.

Hierarchical Window Attention with Pyramid Pooling: To mitigate the Transformer’s local detail loss, we propose an enhanced customized architecture termed Pyramid Self-learning Fusion Module by constructing four-level feature pyramids via patch merging. The dynamic shifted window mechanism enables cross-scale context modeling. Innovatively, dual pyramid pooling modules perform multi-granular spatial pooling on local and global features. After bilinear upsampling and convolution-based channel control, this strategy significantly improves vegetation classification by fusing local details with global semantics.

Spatial Graph Convolution-Guided Feature Propagation: The proposed Graph Fusion Module maps local, global, and fused features into high-dimensional graph nodes, constructing spatial topology using 4-neighbor adjacency matrices. Three GCN pathways facilitate feature propagation, with learnable weights dynamically aggregating improved node features. This design goes beyond traditional grid limitations, establishing long-range dependencies in the reconstruction space to address semantic discontinuities caused by high-rise occlusions.

In the next section, we discuss some related works in the remote sensing image segmentation. Subsequently, the proposed framework is detailed in

Section 3, followed by a presentation of all experimental results in

Section 4. Finally, in

Section 5, we discuss future research directions and summarize this work.

2. Related Works

In recent years, deep learning-based image segmentation techniques have made remarkable progress, with a core focus on effectively extracting and fusing multi-scale and multi-modal features. Representative technologies such as CNNs and Transformers have propelled this field from the perspectives of local perception and global dependency modeling, respectively. Research trends are gradually shifting from single-model dominance toward hybrid approaches that integrate multiple techniques to overcome individual limitations and achieve performance breakthroughs.

2.1. CNN-Based Remote Sensing Image Segmentation

CNNs have achieved significant success in the field of remote sensing semantic segmentation due to their powerful capabilities in local feature extraction and spatial relationship modeling. Early CNN architectures like AlexNet [

18] and VGGNet [

23] achieved hierarchical abstraction of image features through stacked convolutional layers, laying the groundwork for subsequent remote sensing image analysis. The Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) [

24] replaced fully connected layers with convolutional layers to enable end-to-end pixel-level predictions, marking a milestone in remote sensing segmentation.

Building on the FCN framework, U-Net [

25] introduced an encoder-decoder architecture with skip connections, effectively addressing the challenge of detail recovery in remote sensing images. This design enables the network to fuse low-level edge information with high-level semantic features during decoding, making it especially suited for accurately delineating complex object boundaries in remote sensing scenarios. The DeepLab series [

26] further expanded the receptive field by introducing atrous convolution while preserving spatial resolution—crucial for capturing multi-scale features in remote sensing images. Notably, the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module in DeepLabV3+ effectively captures multi-scale contextual information, enhancing segmentation accuracy for objects of varying sizes. To address the unique characteristics of remote sensing imagery, Chen et al. [

27] proposed a CNN model based on attention mechanisms that learns to weigh important features, thereby improving recognition of complex land covers. Wang et al. [

28] introduced a multi-scale feature fusion strategy to effectively handle large variations in object scale within remote sensing data. However, traditional CNNs have limitations in modeling long-range dependencies, making it challenging to capture broad contextual and non-local features in remote sensing images. This has prompted researchers to explore more advanced model architectures.

2.2. Transformer-Based Remote Sensing Semantic Segmentation

Originally successful in natural language processing [

29], Transformers have since been adopted in computer vision. The Vision Transformer (ViT) [

30] processes images as sequences of fixed-size patches to model global context but suffers from quadratic computational complexity relative to input image size, limiting its applicability to high-resolution remote sensing images. The Swin Transformer alleviates this limitation by introducing a shifted window mechanism. Its hierarchical structure and localized self-attention computation allow for global dependency modeling while maintaining linear computational complexity, making it especially suitable for large-scale remote sensing images. The Swin Transformer’s ability to represent multi-scale features enables outstanding performance in remote sensing segmentation tasks, particularly in modeling extensive regions and intricate textures. Zheng et al. [

31] proposed Swin-UNet, which integrates the Swin Transformer into a U-Net framework, combining Transformer-based global modeling with U-Net’s detailed feature recovery. Xu et al. [

32] developed a hierarchical feature extraction network based on Swin Transformer to address multi-scale semantic segmentation in remote sensing images. Bazi et al. [

33] designed the RS-ST model specifically for high-resolution remote sensing imagery, incorporating improved window partitioning and feature fusion strategies to enhance sensitivity to complex boundaries. Liu et al. [

34] further incorporated a spatial attention module into the Swin Transformer, improving the model’s perception of spatial distribution patterns in remote sensing data. Despite their strength in modeling long-range dependencies, Transformers still face challenges in capturing fine-grained local details, motivating research into hybrid architectures that combine CNNs and Transformers to leverage their complementary strengths.

2.3. GCNs-Based and Other Related Deep Learning Methods

GCN [

35] perform convolutions in non-Euclidean space, offering a new paradigm for processing data with complex topological structures. In remote sensing segmentation, GCNs can effectively model spatial relationships and contextual dependencies between objects, addressing the limitations of CNNs’ local receptive fields. Remote sensing imagery often exhibits complex spatial dependencies. Liang et al. [

36] applied GCNs to remote sensing segmentation by constructing pixel-level relational graphs, enhancing spatial correlation modeling—particularly beneficial for segmenting irregularly shaped objects. Chen et al. [

37] proposed a dynamically constructed GCN model that adaptively connects nodes based on feature similarity, improving segmentation accuracy in complex scenes. Sun et al. [

38] innovatively combined GCNs with attention mechanisms to design a spatial relationship-enhanced network, learning long-range dependencies between objects to significantly improve segmentation performance. Zhang et al. [

39] further explored multi-scale graph convolution operations, constructing graphs at different scales to improve recognition of objects of varying sizes. In recent years, integration of CNNs, Transformers, and GCNs has become a research hotspot. Wang et al. [

40] proposed a hybrid architecture where CNNs extract local features, Transformers model global dependencies, and GCNs enhance spatial relationship modeling—together significantly improving remote sensing segmentation accuracy. Li et al. [

41] designed a hierarchical feature fusion framework that applies CNNs, Transformers, and GCNs at different levels, achieving more accurate boundary delineation through multi-level feature complementarity. Our proposed PLGTransformer model follows this trend by integrating the strengths of CNNs (local feature extraction), Swin Transformers (global context modeling), and GCNs (spatial relationship enhancement) into a unified remote sensing segmentation framework. This model effectively handles multi-scale features and complex textures in remote sensing images while modeling spatial dependencies through graph structures, thus achieving more accurate and robust semantic segmentation results.

With the growth of deep learning technologies, research is increasingly focused on improving feature extraction and modeling in remote sensing image segmentation. The Mamba model [

42], an emerging deep learning architecture, has shown promise in this area. It combines convolutional neural networks (CNN) with attention mechanisms, enabling effective local feature extraction and global dependency modeling. This allows the Mamba model to distinguish objects in complex images and handle multi-scale features, making it particularly effective for high-resolution remote sensing images with varying object sizes [

43]. Additionally, the Mamba model enhances segmentation performance through multi-modal information fusion, utilizing data from different sensors such as optical and radar images. This capability improves object recognition and segmentation accuracy in complex environments [

44]. Overall, the Mamba model excels in remote sensing image segmentation, leveraging CNNs and attention mechanisms to provide effective solutions across various applications.

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) model [

45] is a deep learning-based object detection method recognized for its efficient real-time processing capabilities. Initially designed for object detection, YOLO has gained attention in remote sensing image segmentation due to its end-to-end training, which allows it to learn effective image features automatically. YOLO divides images into grids, with each grid predicting the location and category of objects, enabling the detection and segmentation of multiple targets in a single pass. This approach is more efficient than traditional sliding window techniques, especially for large-area remote sensing images. Its rapid detection makes YOLO suitable for real-time applications, such as disaster monitoring and urban planning, where it can quickly identify land cover changes. For instance, Gao et al. [

46] applied YOLO in flood monitoring to swiftly pinpoint affected areas. However, while YOLO excels in object detection, it may lack precision in complex segmentation tasks requiring high detail, prompting researchers to enhance it by integrating other deep learning techniques for better accuracy.

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [

47] networks are a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) designed for handling long-term dependencies in sequential data. Originally developed for language models and time series, LSTMs have proven effective in remote sensing image segmentation due to their ability to capture time- or space-varying patterns. They are particularly useful for processing multi-temporal remote sensing data, allowing models to learn relationships between images from different time points and detect land cover changes. For example, Chen et al. [

48] applied LSTM to monitor urban development and crop growth, accurately identifying land cover changes. However, LSTMs require substantial training data and computational resources, which can limit their practical application, especially for high-resolution images. Nevertheless, advancements in technology are enhancing the feasibility of LSTM models in remote sensing image segmentation, particularly for tasks needing high spatiotemporal resolution.

2.4. Overall Architecture

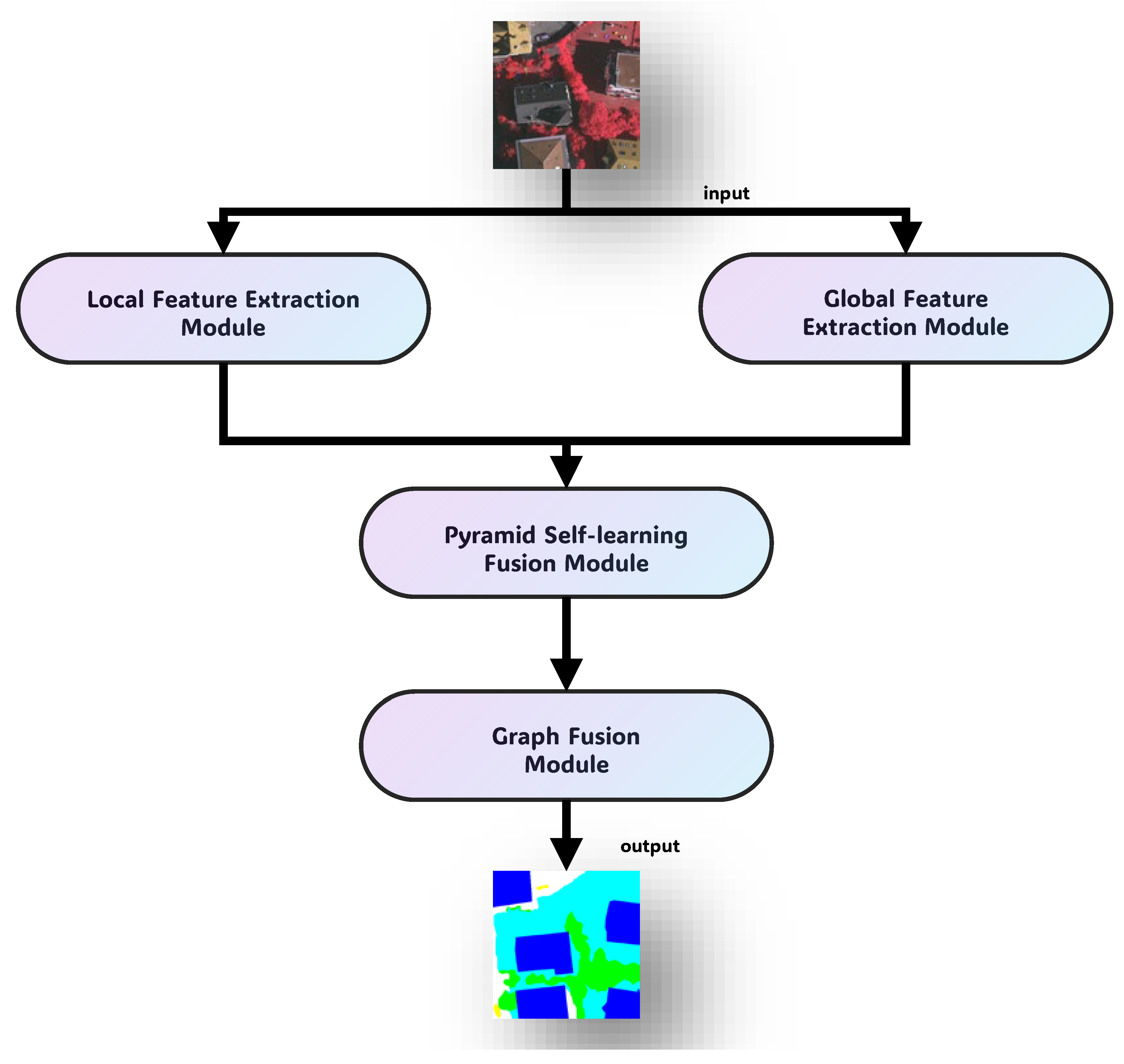

The overall architecture of PLGTransformer is illustrated in

Figure 1. The model combines the strengths of CNNs for local structural perception, the Swin Transformer for global dependency modeling, and GCNs for structured spatial representation. This synergy enables accurate segmentation of multi-scale and diverse land cover types in remote sensing imagery. PLGTransformer comprises three main functional modules.

3. Methodology

This section details the overall design of our proposed PLGTransformer model, including its parallel encoding architecture and graph convolutional fusion module. The model integrates multi-scale feature representation with local spatial cues, global contextual information, and graph-structured awareness, significantly improving semantic segmentation performance.

First, three heterogeneous local feature extractors are employed in parallel to extract multi-scale local representations, enhancing the model’s ability to capture texture and boundary information. Second, a hierarchical Swin Transformer backbone is used to model global context through shifted window-based multi-head self-attention, efficiently capturing long-range dependencies. Third, pyramid pooling modules are embedded into both local and global branches to broaden semantic perception and enhance contextual awareness via multi-scale pooling. After local and global features are extracted, a learnable weighted fusion mechanism is designed to explicitly integrate these complementary sources, optimizing the combination of heterogeneous features. Furthermore, a graph-based fusion module is introduced to enhance spatial structure awareness. This module leverages GCNs to model topological relationships within the fused features, strengthening spatial adjacency and boundary continuity.

Finally, a convolutional prediction head and an upsampling module map the refined feature maps back to the original input resolution, yielding pixel-wise semantic segmentation outputs. In summary, PLGTransformer adopts a three-level synergy of local-global-structural design, forming an end-to-end segmentation framework with both multi-scale understanding and spatial modeling capabilities for remote sensing applications.

3.1. Parallel Encoding Architecture

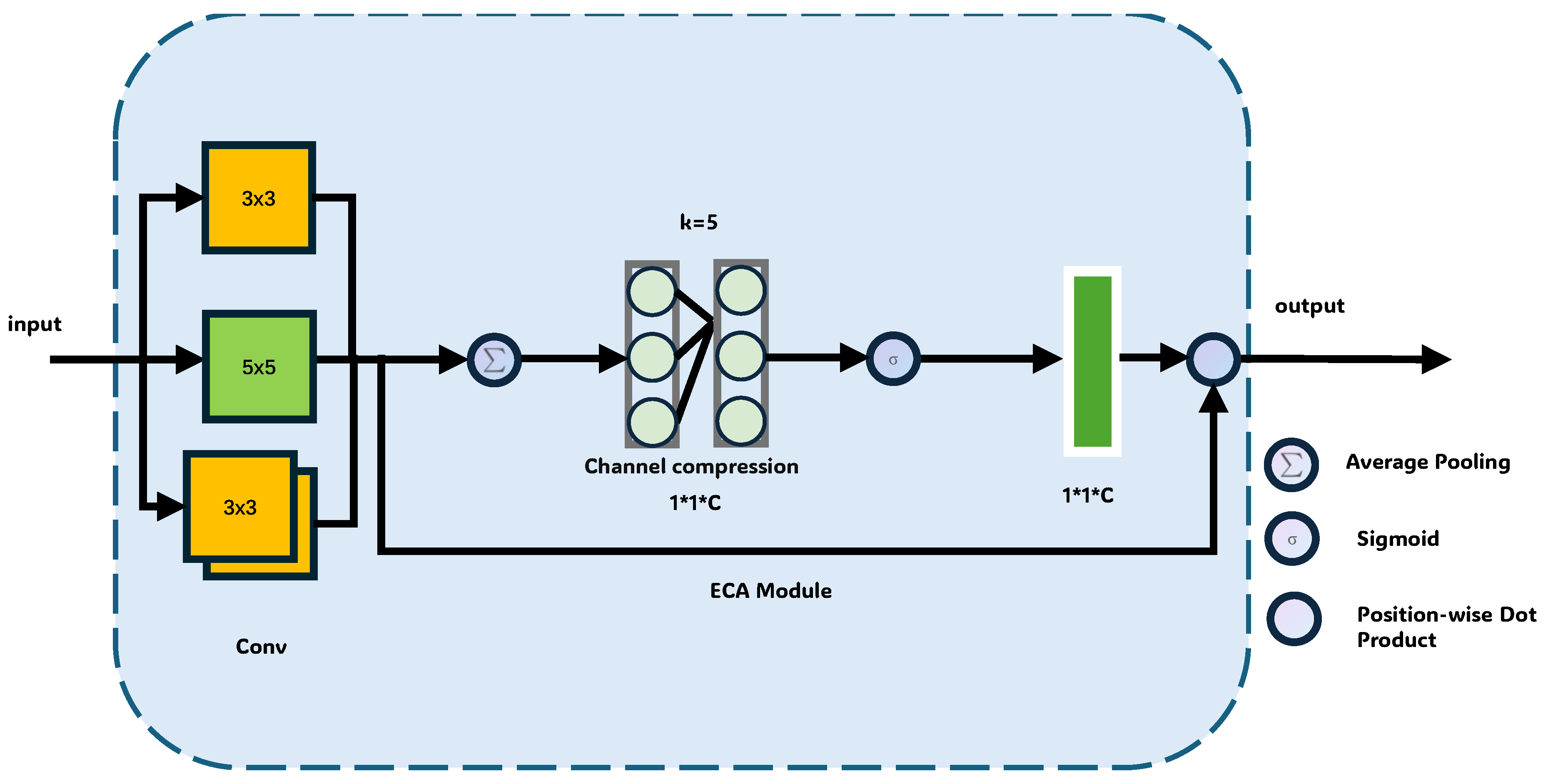

We achieve efficient local feature extraction and multi-scale contextual fusion through the collaborative design of a heterogeneous convolutional architecture and pyramid pooling. Specifically, as shown in

Figure 2, three independent local feature extractors: LocalFeatureExtractor1, LocalFeatureExtractor2, and LocalFeatureExtractor3, each use convolutional kernels of different sizes for feature extraction and optimize the features through pooling strategies. This can be expressed as follows:

(1) LocalFeatureExtractor1:

Here, a convolutional kernel (i.e., ) is used to extract high-frequency texture features from the input x, and the max pooling (i.e., ) operation retains prominent features.

(2) LocalFeatureExtractor2:

A 5×5 convolutional kernel is used to extract mid-scale semantic features, and the average pooling (i.e., ) operation suppresses noise.

(3) LocalFeatureExtractor3:

The cascading of two

convolutional kernels is used to extract fine-grained detail features. After feature extraction through the three branches, the features are upsampled to a

resolution using bilinear interpolation and concatenated along the channels to obtain a unified local feature map:

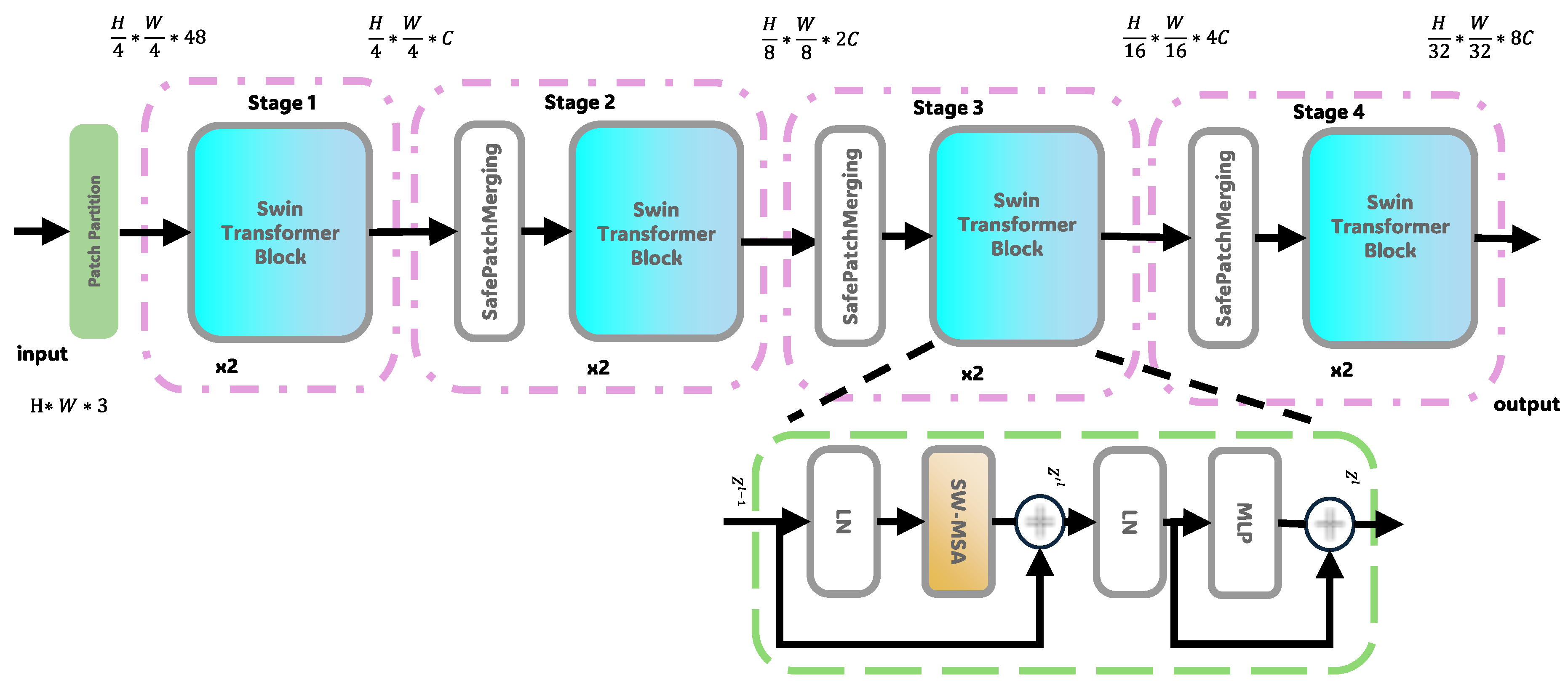

To achieve efficient long-range dependency modeling and global feature extraction, we use an improved hierarchical Swin Transformer and enhance global feature modeling through dynamic window attention mechanisms. As shown in

Figure 3, the input image is first divided into non-overlapping image patches using a

convolution kernel in the Patch Embedding layer, generating a 96-channel feature map of size

. The image is then input into the four-stage Transformer architecture. In the first stage, it contains 2 Swin Blocks, using a fixed window size of

for multi-head attention calculation (4 heads). This stage enhances the low-level semantic representation through the interaction of local and global features:

Then from the second to fourth stages, a hierarchical downsampling strategy is adopted, where the SafePatchMerging module merges adjacent

feature blocks before each stage, achieving

downsampling of spatial resolution (

) and a stepwise expansion of channel numbers. The mathematical expressions are:

Each Swin Block uses an alternating structure of window multi-head attention and shifted window attention, which is represented as:

where

B is a learnable relative positional bias and

is the dimension of each attention head. During the merging, features from

neighboring regions are concatenated and projected through a linear layer for downsampling and channel expansion. The final global feature output is normalized and upsampled via bilinear interpolation to align with the local feature resolution.

3.2. Pyramid Self-learning Fusion Module

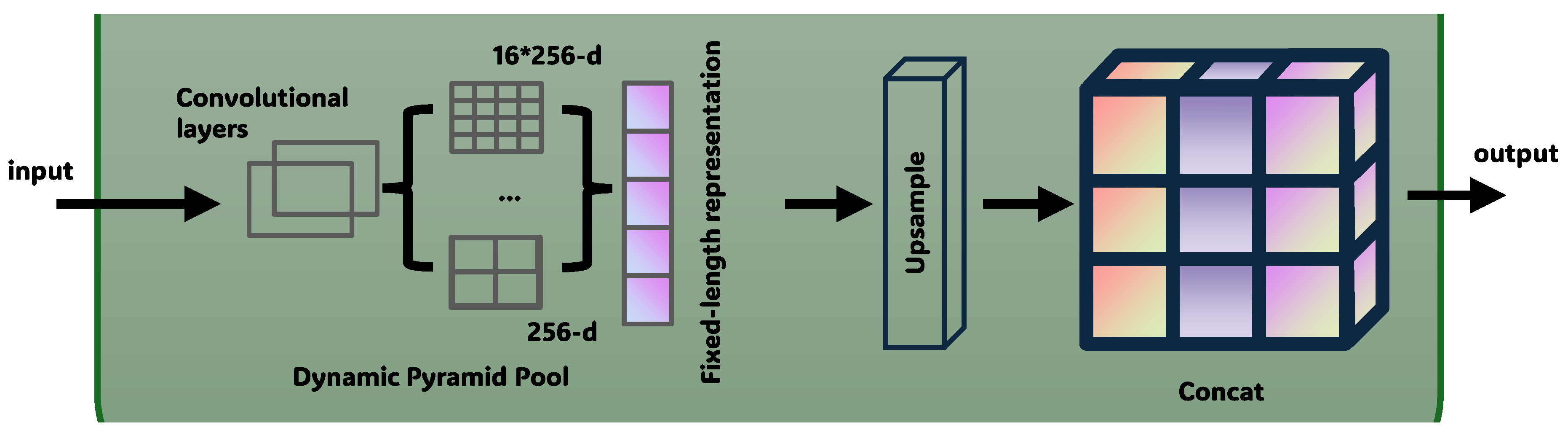

To effectively capture multi-scale contextual information in images and enhance the segmentation ability for complex objects, we propose an adaptive pyramid pooling fusion module as shown in

Figure 4. This module optimizes feature fusion through multi-scale context aggregation and dynamic weight learning. The specific design is as follows:

(1) Pyramid Pooling Operation: The module first applies the pyramid pooling operation to both local and global feature channels to extract contextual information at different scales. Specifically, for the input feature map

, we perform pooling at different scales:

where

denotes the feature maps at different pooling scales.

(2) Feature Dimension Matching: To reduce the number of channels and match the feature dimensions, the multi-scale features obtained from pooling are processed through a

convolution:

where

is the output number of channels after the convolution.

(3) Feature Concatenation and Weighted Fusion: The pooled multi-scale features are fused through concatenation:

Subsequently, we design a weighted fusion mechanism, which explicitly fuses local and global features through a 1×1 convolution and learnable normalized weights:

where

are the normalized weights learned to dynamically adjust the contribution ratios from different feature sources. This mechanism can dynamically adjust the contribution of different feature sources based on the task requirements, thus improving the expression ability of fused features, enhancing the network’s perception of features at different scales, and ultimately improving the accuracy and robustness of semantic segmentation for remote sensing images.

3.3. Graph Fusion Module

While CNNs and Transformers effectively extract local and global features, they face challenges in capturing structured spatial relationships—particularly in complex remote sensing scenes. Pixels in remote sensing images exhibit not only local attributes but also long-range, structured dependencies tied to object boundaries, textures, shapes, and inter-object interactions. To better model such spatial structures, we introduce a GraphFusionModule based on GCNs. This module enhances the semantic coherence and boundary accuracy of the segmentation results by learning topological relations across multi-source features. As shown in

Figure 5, the multi-source graph convolution fusion network constructs dynamic graphs and learns adaptive weights to model the topological relationships between local and global features. The specific design process is as follows:

(1) Graph Construction: The module constructs a multi-adjacency graph structure, converting local features, global features, and fused features into graph nodes, and performs graph convolution operations to enhance the expression of target boundaries, structural relationships, and spatial consistency. First, the local, global, and fused features are uniformly upsampled to generate feature maps:

These feature maps are flattened to form the node feature matrix H and the adjacency matrix A.

(2) Graph Convolution Operation: The graph convolution operation updates the node features

H as follows:

where

D is the degree matrix,

A is the adjacency matrix,

W is the weight parameters, and

is the activation function. The graph convolution operation is performed separately on local features, global features, and fused features.

(3) Weighted Fusion: A learnable vector

is used to perform weighted fusion on the graph convolution outputs of local, global, and fused features:

This weighted mechanism dynamically adjusts the contribution of different source graph models according to the task requirements.

(4) Category Mapping and Feature Recovery: Finally, the network maps the fused output to the category space using a

convolution, and recovers the features to the input size using bilinear interpolation, thus obtaining the final semantic prediction map:

This process is simple and efficient, supports end-to-end training, and is particularly suitable for segmentation tasks in remote sensing images with complex structures and diverse scales.

3.4. Loss Function

In remote sensing image semantic segmentation, precise object recognition requires high accuracy in both region classification and boundary localization. This is crucial for high-resolution images, where complex object shapes can lead to blurred boundaries and concentrated errors. This study presents a composite loss function, the Multi-scale Boundary Focal Loss Function , to optimize both region recognition and boundary delineation. This loss function consists of two components: the first component is the Multi-class Region Focal Loss, which is used to optimize pixel-wise classification within regions; the second component is the Multi-scale Boundary Loss, which strengthens the model’s sensitivity to boundary pixels. The final combined loss function is expressed as follows:

where

denotes the Multi-class Region Focal Loss for the region,

represents the Multi-scale Boundary Loss, and

is the balancing coefficient controlling the relative importance of the two components. Among this, the two loss terms are defined as:

The number of classes is set to 6, addressing the requirements of multi-class segmentation tasks in remote sensing images. For the Multi-class Region Focal Loss, the focusing parameter is set to to emphasize hard examples, while the class balancing factor is set to to ensure equal contributions from all classes. The weight of the boundary loss is also regulated by , which is set to 0.3 to emphasize boundary regions. To enhance boundary perception at different scales, the boundary loss is calculated using three scales: , , and . Finally, the balancing coefficient is set to 0.3 to adjust the trade-off between region focal loss and boundary loss.

4. Experiments and Discussion

The primary objective of the experiments is to quantitatively and qualitatively verify the performance of the proposed model in remote sensing image segmentation. By comparing with traditional methods and the latest deep learning models, we aim to demonstrate the advantages of the proposed model in improving segmentation accuracy, handling boundaries, and detecting small objects.

4.1. Dataset Descriptions

In this study, we used the ISPRS Vaihingen and Potsdam datasets to evaluate the PLGTransformer model. Both datasets contain high-resolution remote sensing images and Digital Surface Models (DSM), providing detailed label information for semantic segmentation tasks.

Vaihingen Dataset: The Vaihingen dataset consists of 16 high-resolution orthophotos, each measuring pixels. Each image includes three spectral channels: Near-Infrared (NIR), Red (R), and Green (G), along with a DSM at ground sampling distance (GSD). The dataset’s labels consist of 5 foreground classes: Buildings, Trees, Low vegetation, Cars, and Impervious surfaces, along with one background class (Clutter). The 16 images were split into a training set (12 images) and a testing set (4 images).

Potsdam Dataset: The Potsdam dataset consists of 24 high-resolution orthophotos, each with a resolution of pixels. It offers four multispectral channels: Red (R), Green (G), Blue (B), and Infrared (IR), with a GSD. Similar to the Vaihingen dataset, it includes 5 foreground classes and 1 background class, but the distribution of foreground classes differs.

4.2. Experimental Setup

All experiments were implemented on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU using the PyTorch framework with 24GB RAM. The specific setup is as follows: We used the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.0001, momentum of 0.9, a decay factor of 0.0005, and a sliding window size of 256×256 for training. During testing, the sliding window size was 32. Data augmentation methods like random rotation, horizontal flipping, and vertical flipping were employed. The training duration was set to 100 epochs.

The AdamW optimizer performed excellently in image segmentation tasks, particularly during deep network training. To avoid overfitting, L2 regularization (weight decay) was added during training with a weight decay coefficient of 1e-4. The learning rate was dynamically adjusted using the CosineAnnealingLR scheduler to help the model converge more effectively. The batch size was set to 4, and we also implemented dropout and early stopping mechanisms to prevent overfitting. Validation metrics like IoU and F1-Score were monitored, and training was stopped early when no improvement was observed.

We utilized custom loss functions such as Multi-Scale Boundary Loss and Adaptive Focal Loss. The Multi-Scale Boundary Loss helped the model better handle boundary regions, while the Adaptive Focal Loss addressed class imbalance by adjusting the weight of each class dynamically.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

In this experiment, we used multiple evaluation metrics to measure the model’s segmentation performance. Common evaluation metrics for remote sensing image segmentation include Intersection over Union (IoU) and F1-Score.

IoU (Intersection over Union): IoU is a standard metric for evaluating image segmentation model performance, calculated as the intersection area of the predicted and ground truth regions divided by their union area. A higher IoU indicates better segmentation accuracy. In the experiments, we computed the IoU for each class and averaged them to obtain the overall IoU. A high IoU value indicates that the model performs well in handling complex boundaries and small objects.

F1-Score: F1-Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall and is typically used to evaluate models with class imbalance. In remote sensing image segmentation tasks, some classes may have significantly fewer samples than others. The F1-Score provides a more comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance across different object types. A higher F1-Score indicates better balance between precision and recall.

To evaluate the segmentation results from multi-modal remote sensing data, we used the mean F1-score (mF1) and mean IoU (mIoU) as the key statistical indicators. These metrics were used to compare the performance of the proposed PLGTransformer with other state-of-the-art methods. Specifically, we computed mF1 and mIoU for the four foreground classes and averaged them to get the final results.

4.4. Comparative Experiments

We compare the PLGTransformer with several state-of-the-art remote sensing image segmentation methods on two different datasets. The selected models for comparison include SwinT [

21], Swin UNet [

49], BANet [

50], FTUNetFormer [

51], and CTFuse [

52]. As shown in

Table 1, on the Vaihingen dataset, the PLGTransformer achieves performance scores of

for mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) and

for mean F1 score (mF1). Compared to the baseline model CTFuse, PLGTransformer improves by

in mIoU and

in mF1. The table highlights that our model excels in the categories of impermeable surfaces, buildings, low vegetation, and trees.

Figure 6 presents the visual results obtained by all six methods on the Vaihingen dataset.

On the Potsdam dataset, as shown in

Table 2, the PLGTransformer achieves performance scores of

for mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) and

for mean F1 score (mF1). Compared to the baseline model CTFuse, PLGTransformer improves by

in mIoU and

in mF1.

Figure 7 presents the visual results obtained by all six methods on the Potsdam dataset. Similar to the results on the Vaihingen dataset, our PLGTransformer performs better than other state-of-the-art models in handling fine details.

It is evident that, compared to other state-of-the-art models, our PLGTransformer performs better in recognizing fine details and handling edges. Specifically, the CNN + Swin Transformer parallel encoding structure effectively combines local texture information with global semantic context, providing a stronger receptive field and region discrimination ability. As observed in

Figure 6, the dual-branch encoding structure allows the model to maintain clear boundary expressions when processing complex scenes, such as "building-road" and "building-low vegetation" adjacent areas. Moreover, the Pyramid Self-Learning Fusion Module (PSFM) in the decoding stage adapts and guides the fusion of multi-scale features, allowing the model to flexibly focus on important regions at different scales. The model effectively captures the subtle semantic transitions between buildings and surrounding low vegetation, achieving continuous edges and complete form segmentation of building objects, significantly outperforming other comparison methods. The integrated GFM models structural relationships between objects in the high-level semantic space, enhancing semantic consistency and reducing errors like object fragmentation. In conclusion, the proposed model excels in segmentation accuracy and shows superior generalization in structural continuity, boundary completeness, and small-object recognition.

4.5. Ablation Experiments

4.5.1. Performance Analysis From Different Modules

To validate the effectiveness of each component in the PLGTransformer, we conducted a series of ablation experiments. By retaining the dual-branch framework, we removed specific components to assess their contributions. We used the basic CNN + Swin Transformer as the baseline and performed ablation experiments on both datasets for comparison. We separately removed the Pyramid Self-Learning Fusion Module (PSFM) and the Graph Neural Network Fusion Module (GFM) on the two datasets. After introducing the hybrid CNN and Transformer structure, the model showed an improvement in accuracy compared to the original UNet model. When the Pyramid Self-Learning Fusion Module (PSFM) was removed, the model’s performance significantly dropped, especially in tasks involving the segmentation of small objects and fine details. This demonstrates that shallow feature fusion is crucial for preserving local details such as object shapes and boundaries. When the Graph Neural Network Fusion Module (GFM) was removed, the model’s ability to model global contextual information greatly decreased. Deep feature fusion plays a key role in handling long-range dependencies and large-scale contextual information in remote sensing images.

The Vaihingen dataset contains images with high texture complexity and a significant presence of small objects, such as vehicles, and tightly distributed targets, such as buildings. The experimental results, as shown in

Table 3, are as follows, After removing the PSFM module, the overall accuracy of the model significantly decreased, with IoU dropping from

to

and F1 decreasing from

to

. This performance drop was particularly noticeable in the recognition of "small object" categories. The introduction of PSFM played a key role in multi-scale feature fusion and boundary recovery, especially improving performance in the "building" and "low vegetation" categories; When the GFM module was removed, the model’s performance in handling large-scale scenes declined, with both IoU and F1 values dropping. IoU decreased from

to

, and there was a noticeable blurring of boundaries in large-scale scenes, highlighting the crucial role of GFM in modeling global contextual information. In remote sensing images, land cover objects often have long-range dependencies, and GFM provides global coherence modeling, ensuring that complex regions in remote sensing images are accurately identified; The complete model (Base + PSFM + GFM) achieved the best performance on this dataset, with significant improvements over the baseline. After integrating PSFM and GFM, the model’s accuracy was balanced in both small-object and large-area segmentation, demonstrating the model’s ability to optimize both global and local features in a collaborative manner.

The Potsdam dataset, known for its high resolution and diverse categories, is ideal for model performance evaluation. Experimental results in

Table 4 indicate that Removing the PSFM module reduces IoU from

to

, significantly impairing small object segmentation, notably for "car" categories where IoU drops by

. PSFM is vital for fine-grained target and multi-scale feature fusion. Removing the GFM module further decreases IoU to

, highlighting its importance for large-scale semantic classification and maintaining global structural consistency. The combined removal of both modules results in a

IoU decrease and a

F1 drop. Using both PSFM and GFM together markedly improves handling complex structures, enhancing feature fusion and adaptability in challenging scenes.

Figure 8 presents the performance of different modules in the ablation experiments. The analysis is as follows: PSFM demonstrates excellent performance in small-object detection and multi-scale scenarios, effectively preserving object shapes and boundaries, particularly in cases with blurred edges. GFM plays a critical role in global semantic modeling, contributing to semantic consistency and capturing long-range dependencies, although its improvement is relatively less pronounced compared to PSFM. The proposed PLGTransformer integrates both local and global feature information, further enhancing segmentation accuracy and cross-dataset robustness. Overall, the experimental results indicate that each module is indispensable for remote sensing image segmentation tasks, and they exhibit strong complementarity.

4.5.2. Performance Variations on Diverse Losses

To evaluate the contribution of each component within the loss function, we conducted a series of ablation experiments on the Vaihingen dataset using our proposed PLGTransformer model. To better understand the role of each component, we designed the following experimental settings: 1) Baseline: Both Multi-class Region Focal Loss (i.e.,

) and Multi-scale Boundary Loss (i.e.,

) are applied; 2) Multi-class Region Focal Loss only: Only the Multi-class Region Focal Loss is used; 3) Multi-scale Boundary Loss only: Only the Multi-scale Boundary Loss is used. The experimental results are summarized in

Table 5. The experimental results show that the complete loss combination, which jointly optimizes both the region focal and boundary losses, results in the best overall performance. Removing either branch leads to a significant decrease in both mIoU and mF1 scores, demonstrating the complementary nature of region classification and boundary modeling.

4.6. Discussion

The PLGTransformer model, by combining the strengths of CNN and Vision Transformers, achieves excellent performance in remote sensing image segmentation tasks. Specifically, the CNN backbone network is employed to extract local detail features, while the Transformer is used to model the global contextual information and long-range dependencies within the image. This multi-level feature fusion mechanism enables PLGTransformer to effectively handle complex scenes and objects with rich details.

Although PLGTransformer achieves excellent performance in remote sensing image segmentation tasks, there are still some limitations, particularly in handling certain categories such as trees and low vegetation. These categories have high similarities in color, texture, and shape, and their boundaries are relatively ambiguous, posing challenges for the model in distinguishing these fine-grained targets. Additionally, despite the model outperforming current methods in segmentation accuracy, its computational complexity is relatively high, especially when processing high-resolution images. The memory usage and inference time are longer. Therefore, optimizing the model architecture to reduce computational overhead and memory consumption remains an important research direction. Moreover, there is still room for improvement in the multi-modal data fusion strategy. Although the integration of optical imagery and DSM data has been used, challenges still exist in handling the heterogeneity and inconsistencies between modalities. Future work could focus on designing more refined fusion mechanisms to improve cross-modal data integration, thereby enhancing the model’s performance in multi-modal remote sensing images.

Future research can focus on several improvements. For fine-grained target segmentation, introducing precise scale-aware modules can enhance performance with irregular shapes and boundary ambiguity. Incorporating traditional methods like edge detection may also boost accuracy in boundary extraction. As remote sensing image resolution increases, computational efficiency and memory demands rise. Future studies could investigate model compression, quantization, or more efficient attention mechanisms for real-time applications and lightweight models for large-scale data processing. Additionally, multi-modal remote sensing image fusion could be improved by effectively handling various data types like radar and LiDAR, addressing modality heterogeneity for better segmentation accuracy. Finally, the PLGTransformer model’s application could extend to fields like medical image analysis and autonomous driving, where similar segmentation challenges exist.

5. Conclusion

This study proposes a novel remote sensing image semantic segmentation method, PLGTransformer, which combines the advantages of CNN and Transformer to optimize for the complexity and diversity of remote sensing images. By fusing multi-level and multi-modal features, the model can effectively capture both local details and global context information, thereby improving segmentation accuracy. In the experimental section, we used the ISPRS Vaihingen and Potsdam datasets to verify the effectiveness of the proposed method. The experimental results show that PLGTransformer outperforms the current state-of-the-art segmentation methods on various evaluation metrics, especially in the tasks of segmenting buildings, trees, and impervious surfaces. Specifically, by deeply integrating optical imagery and DSM data, the model successfully improves segmentation performance for objects with different scales and shapes. The innovation of this study lies in the proposed multi-level feature fusion mechanism. By combining the strengths of shallow and deep features, the model improves its ability to handle complex remote sensing images. Furthermore, the model’s global context modeling ability, based on the Swin Transformer, enables it to capture long-range dependencies, significantly improving segmentation performance in remote sensing images.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and G.W.; methodology, Y.L., and G.W.; software, Y.L.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L. and G.W.; investigation, Y.L., and G.W.; resources, G.W.; data curation, Y.L. and G.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., and G.W.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, G.W.; project administration, Y.L., and G.W.; funding acquisition, G.W.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fu, K.; Lu, W.X.; Liu, X.Y.; Deng, C.B.; Yu, H.F.; Sun, X. A comprehensive survey and assumption of remote sensing foundation modal. National Remote Sensing Bulletin 2024, 28, 1667–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Hu, B. REU-Net: A Remote Sensing Image Building Segmentation Network Based on Residual Structure and the Edge Enhancement Attention Module. Applied Sciences (2076-3417) 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Seng, K.P.; Ang, L.M.; Peng, B.; Zhao, X. Hyper-CycleGAN: A New Adversarial Neural Network Architecture for Cross-Domain Hyperspectral Data Generation. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.P.; Zhang, L.F.; Du, B. Deep Learning for Remote Sensing Data: A Technical Tutorial on the State of the Art. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2016, 4, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazerouni, A.; Karimijafarbigloo, S.; Azad, R.; Velichko, Y.; Bagci, U.; Merhof, D. FuseNet: Self-Supervised Dual-Path Network For Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI); 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models from Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Salt Lake City, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Chen, D.; Chen, Y.L.; Codella, N.C.F.; Dai, X.; Gao, J.; Hu, H.; Huang, X.; Li, B.; Li, C.; et al. Florence: A New Foundation Model for Computer Vision. ArXiv 2021, abs/2111.11432.

- Bao, H.; Dong, L.; Piao, S.; et al. BEiT: BERT PreTraining of Image Transformers. In Proceedings of the The Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sherrah, J. Fully convolutional networks for dense semantic labelling of high-resolution aerial imagery. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.02585 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Jia, X.; Paull, D. Effective sequential classifier training for SVM-based multitemporal remote sensing image classification. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2018, 27, 3036–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, M. Random forest classifier for remote sensing classification. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2007, 26, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. A New Paradigm of Remote Sensing Image Interpretation by Coupling Knowledge Graph and Deep Learning. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2022, 47, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, G.; Gu, J.; Han, J. Pruning convolutional neural networks with an attention mechanism for remote sensing image classification. Electronics 2020, 9, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Pan, X.; Li, F. DenseU-net-based semantic segmentation of small objects in urban remote sensing images. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 65347–65356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, G.; Sun, X.; Hu, P.; Liu, Y. Attention-Based Multi-Kernelized and Boundary-Aware Network for image semantic segmentation. Neurocomputing 2024, 597, 127988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Dong, J.; Zhou, H.; Chen, S. Gaussian dynamic convolution for efficient single-image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2021, 32, 2937–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, G.; Liu, Y. Prototype Enhancement for Few-Shot Point Cloud Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing. Springer; 2024; pp. 270–285. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proc. NIPS; 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- An, W.; Wu, G. Hybrid spatial-channel attention mechanism for cross-age face recognition. Electronics 2024, 13, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Sun, X.; Chen, C.; Dong, J.; Zhou, H. Parallel complement network for real-time semantic segmentation of road scenes. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 23, 4432–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; et al. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the Proc. ICCV; 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Bai, C. Multi-scale medical image segmentation based on pixel encoding and spatial attention mechanism. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi 2024, 41, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proc. ICLR; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proc. CVPR; 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proc. MICCAI; 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proc. ECCV; 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, P.; Feng, M. A self-attention CNN for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 59, 3155–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Chanussot, J.; Li, X. Scene classification with recurrent attention of VHR remote sensing images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; et al. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Proc. NIPS; 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the Proc. ICLR; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; et al. Swin-UNet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proc. MICCAI; 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. Multi-scale spatial context-aware transformer for remote sensing image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bazi, Y.; Bashmal, L.; Al Rahhal, M.M.; Dayil, R.A.; Ajami, N. Vision transformers for remote sensing image classification. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Li, X. SwinFCN: A spatial attention Swin transformer backbone for semantic segmentation of high-resolution aerial images. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Proc. ICLR; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. SwinIR: Image restoration using Swin transformer. In Proceedings of the Proc. ICCV; 2021; pp. 1833–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Badrinarayanan, V.; Lee, C.Y.; Rabinovich, A. GradNet: Gradient-guided network for visual object tracking. In Proceedings of the Proc. ICCV; 2019; pp. 6162–6171. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Li, W.; Guan, X.; Liu, H.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y. Dual attention graph convolutional network for semantic segmentation of very high resolution remote sensing imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Multi-scale graph convolutional network for remote sensing image segmentation. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-local neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proc. CVPR; 2018; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B. MAT-GCN: A multi-scale attention guided graph convolutional network for remote sensing scene classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Dan, J.; Lu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X. CM-UNet: Hybrid CNN-Mamba UNet for Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. arXiv preprint 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Xu, H. Multimodal fusion for remote sensing image segmentation using Mamba model. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing 2022, 16, 019–032. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Real-time remote sensing image change detection using YOLO. Journal of Remote Sensing Technology 2019, 20, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vennerød, C.; Kjærran, A.; Bugge, E. Long Short-term Memory RNN. ArXiv 2021, abs/2105.06756.

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q. Remote sensing image segmentation based on LSTM for urban change detection. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2020, 41, 2048–2061. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-Unet: Unet-like Pure Transformer for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the ECCV Workshops; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, G.; Li, S.; Bourahla, O.E.; Wu, Y.; Wang, F.; Feng, J.; Xu, M.; Li, X. BANet: Bidirectional Aggregation Network With Occlusion Handling for Panoptic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020; pp. 3792–3801. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, C.; Fang, S.; Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Atkinson, P.M. UNetFormer: A UNet-like transformer for efficient semantic segmentation of remote sensing urban scene imagery. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 190, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, D.; Xiong, Q.; Deng, C. CTFuseNet: A Multi-Scale CNN-Transformer Feature Fused Network for Crop Type Segmentation on UAV Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The overall structure of the PLGTransformer we propose consists of four components: the local feature extractor, the global feature extractor, the pyramid self-fusion module, and the graph fusion module.

Figure 1.

The overall structure of the PLGTransformer we propose consists of four components: the local feature extractor, the global feature extractor, the pyramid self-fusion module, and the graph fusion module.

Figure 2.

The architecture of the local feature extractor in the parallel feature encoder.

Figure 2.

The architecture of the local feature extractor in the parallel feature encoder.

Figure 3.

The architecture of the global feature extractor based on Swin Transformer in the parallel feature encoder.

Figure 3.

The architecture of the global feature extractor based on Swin Transformer in the parallel feature encoder.

Figure 4.

The main structure of the Pyramid Self-learning Fusion Module.

Figure 4.

The main structure of the Pyramid Self-learning Fusion Module.

Figure 5.

The main structure of the Graph Gusion Module.

Figure 5.

The main structure of the Graph Gusion Module.

Figure 6.

Image segmentation comparisons on the Vaihingen dataset. In the figure, the following are shown: (1) Original Image; (2) Ground Truth; (3) SwinT; (4) Swin UNet; (5) BANet; (6) FTUNetFormer; (7) CTFuse. (8) PLGTransformer.

Figure 6.

Image segmentation comparisons on the Vaihingen dataset. In the figure, the following are shown: (1) Original Image; (2) Ground Truth; (3) SwinT; (4) Swin UNet; (5) BANet; (6) FTUNetFormer; (7) CTFuse. (8) PLGTransformer.

Figure 7.

Image segmentation comparisons on the Potsdam dataset. In the figure, the following are shown: (1) Original Image; (2) Ground Truth; (3) SwinT; (4) Swin UNet; (5) BANet; (6) FTUNetFormer; (7) CTFuse; (8) PLGTransformer.

Figure 7.

Image segmentation comparisons on the Potsdam dataset. In the figure, the following are shown: (1) Original Image; (2) Ground Truth; (3) SwinT; (4) Swin UNet; (5) BANet; (6) FTUNetFormer; (7) CTFuse; (8) PLGTransformer.

Figure 8.

Image segmentation results in the ablation study. In this figure, the following are shown: (1) Original Image, (2) Baseline Model, (3) PSFM Module Removed, (4) GFM Module Removed, (5) Proposed Model.

Figure 8.

Image segmentation results in the ablation study. In this figure, the following are shown: (1) Original Image, (2) Baseline Model, (3) PSFM Module Removed, (4) GFM Module Removed, (5) Proposed Model.

Table 1.

Comparison results of different modules on the Vaihingen dataset.

Table 1.

Comparison results of different modules on the Vaihingen dataset.

| Model |

Imp. surf. |

Building |

Car |

Low veg. |

Tree |

mIoU |

mF1 |

| IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

| SwinT |

72.74 |

82.27 |

81.90 |

88.83 |

26.24 |

44.02 |

66.31 |

79.93 |

68.41 |

79.46 |

63.12 |

74.90 |

| Swin UNet |

65.75 |

77.08 |

71.51 |

81.24 |

28.05 |

46.36 |

55.10 |

69.61 |

61.01 |

73.89 |

56.28 |

69.64 |

| BANet |

72.14 |

81.87 |

81.47 |

88.44 |

32.96 |

52.26 |

65.70 |

79.38 |

68.94 |

79.84 |

64.24 |

76.36 |

| FTUNetFormer |

75.91 |

84.60 |

84.49 |

90.38 |

43.71 |

63.99 |

69.06 |

82.33 |

70.28 |

80.88 |

68.69 |

80.44 |

| CTFuse |

77.19 |

85.37 |

78.51 |

87.96 |

56.06 |

71.84 |

73.20 |

84.53 |

72.03 |

83.74 |

71.40 |

82.69 |

| PLGTransformer |

81.46 |

88.45 |

77.64 |

87.41 |

59.05 |

74.26 |

73.38 |

84.65 |

72.74 |

84.22 |

72.85 |

83.80 |

Table 2.

Comparison results of different models on the Potsdam dataset.

Table 2.

Comparison results of different models on the Potsdam dataset.

| Model |

Imp. surf. |

Building |

Car |

Low veg. |

Tree |

mIoU |

mF1 |

| IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

| SwinT |

65.17 |

74.50 |

58.06 |

63.03 |

51.71 |

58.41 |

67.84 |

79.01 |

58.74 |

68.76 |

60.30 |

68.74 |

| Swin UNet |

59.52 |

69.56 |

54.59 |

60.22 |

56.77 |

62.52 |

63.38 |

75.12 |

52.06 |

62.35 |

57.26 |

65.95 |

| BANet |

63.25 |

72.82 |

55.99 |

61.28 |

53.51 |

59.82 |

66.77 |

78.09 |

54.65 |

64.62 |

58.83 |

67.33 |

| FTUNetFormer |

66.87 |

75.78 |

59.23 |

63.96 |

57.66 |

63.24 |

70.16 |

81.14 |

60.25 |

70.30 |

62.83 |

70.88 |

| CTFuse |

67.98 |

76.55 |

68.81 |

81.52 |

59.56 |

74.66 |

77.46 |

87.30 |

61.37 |

76.06 |

67.04 |

79.22 |

| PLGTransformer |

58.90 |

74.14 |

85.21 |

92.01 |

70.44 |

82.66 |

61.11 |

70.40 |

75.14 |

85.81 |

70.16 |

81.00 |

Table 3.

Ablation results from different modules on the Vaihingen dataset.

Table 3.

Ablation results from different modules on the Vaihingen dataset.

| Model |

Imp. surf. |

Building |

Car |

Low veg. |

Tree |

mIoU |

mF1 |

| IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

| Base |

65.75 |

77.08 |

71.51 |

81.24 |

18.05 |

26.36 |

45.10 |

59.61 |

61.01 |

73.89 |

52.29 |

63.64 |

| Base+PSFM |

67.28 |

78.41 |

78.70 |

86.81 |

6.90 |

11.24 |

50.68 |

64.70 |

61.90 |

74.27 |

53.09 |

63.09 |

| Base+GFM |

70.57 |

80.66 |

79.66 |

87.19 |

29.19 |

39.27 |

53.71 |

67.62 |

67.07 |

78.35 |

60.04 |

70.62 |

| Base+PSFM+GFM |

81.46 |

88.45 |

77.64 |

87.41 |

59.05 |

74.26 |

73.38 |

84.65 |

72.74 |

84.22 |

72.85 |

83.80 |

Table 4.

Ablation results from different modules on the Potsdam dataset.

Table 4.

Ablation results from different modules on the Potsdam dataset.

| Model |

Imp. surf. |

Building |

Car |

Low veg. |

Tree |

mIoU |

mF1 |

| IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

IoU |

F1 |

| Base |

59.52 |

69.56 |

59.72 |

64.58 |

40.61 |

45.91 |

52.27 |

63.12 |

41.01 |

51.08 |

50.63 |

58.85 |

| Base+PSFM |

61.18 |

71.40 |

76.76 |

82.10 |

42.35 |

50.52 |

61.87 |

73.26 |

61.00 |

70.97 |

60.63 |

69.65 |

| Base+GFM |

62.26 |

72.06 |

75.00 |

80.57 |

56.55 |

62.58 |

58.73 |

70.19 |

65.70 |

76.22 |

63.65 |

72.32 |

| Base+PSFM+GFM |

58.90 |

74.14 |

85.21 |

92.01 |

70.44 |

82.66 |

61.11 |

70.40 |

75.14 |

85.81 |

70.16 |

81.00 |

Table 5.

Ablation results on the Vaihingen dataset with different loss settings

Table 5.

Ablation results on the Vaihingen dataset with different loss settings

| Setting |

|

|

mIoU |

mF1 |

| Baseline |

✓ |

✓ |

72.85 |

83.80 |

| Multi-class Region Focal Loss Only |

✓ |

|

61.62 |

70.09 |

| Multi-scale Boundary Loss Only |

|

✓ |

63.43 |

74.06 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).