Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

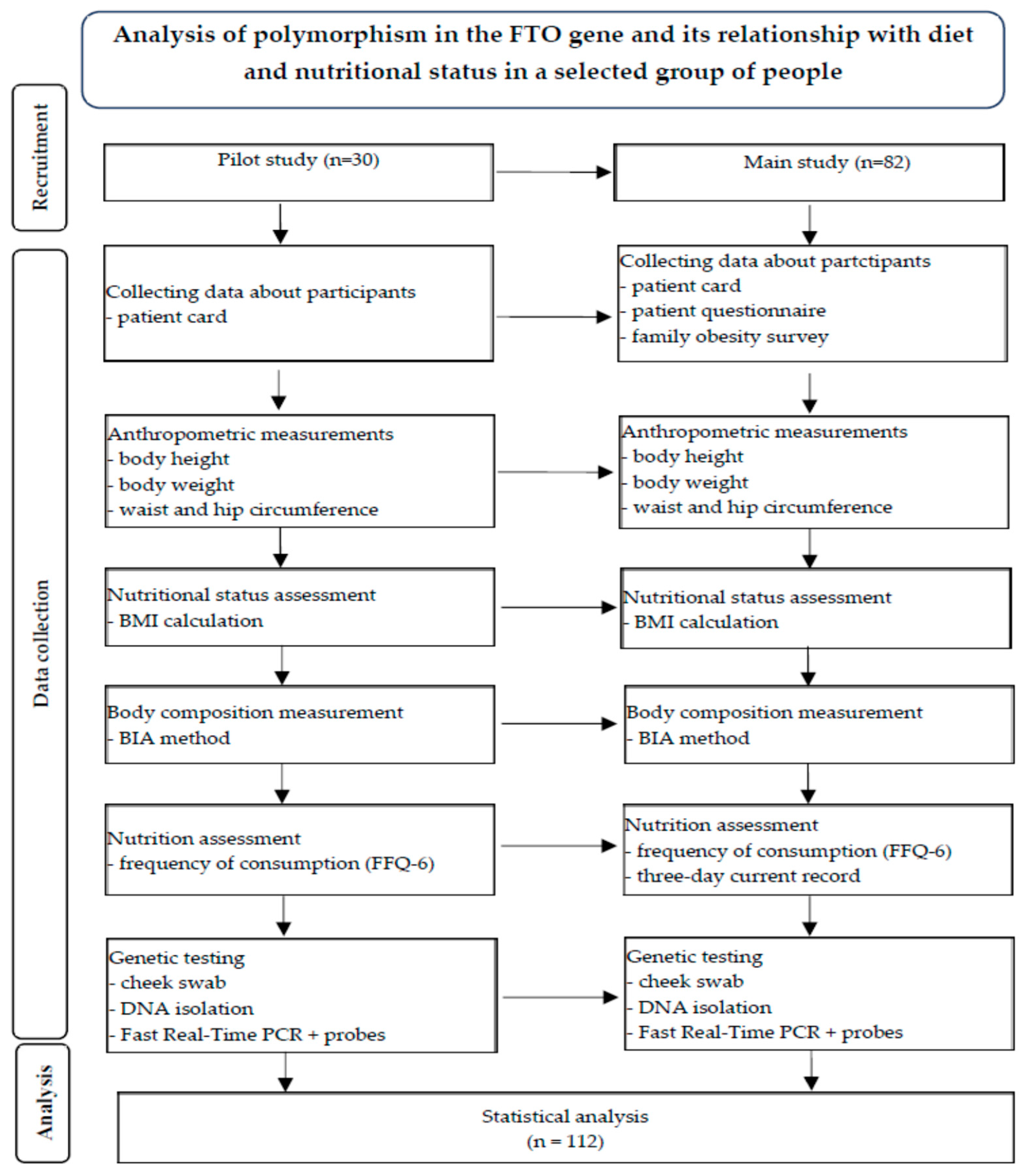

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Selection of Participants

2.4. Nutritional Status

2.5. Dietary Intake

2.6. Genotyping

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

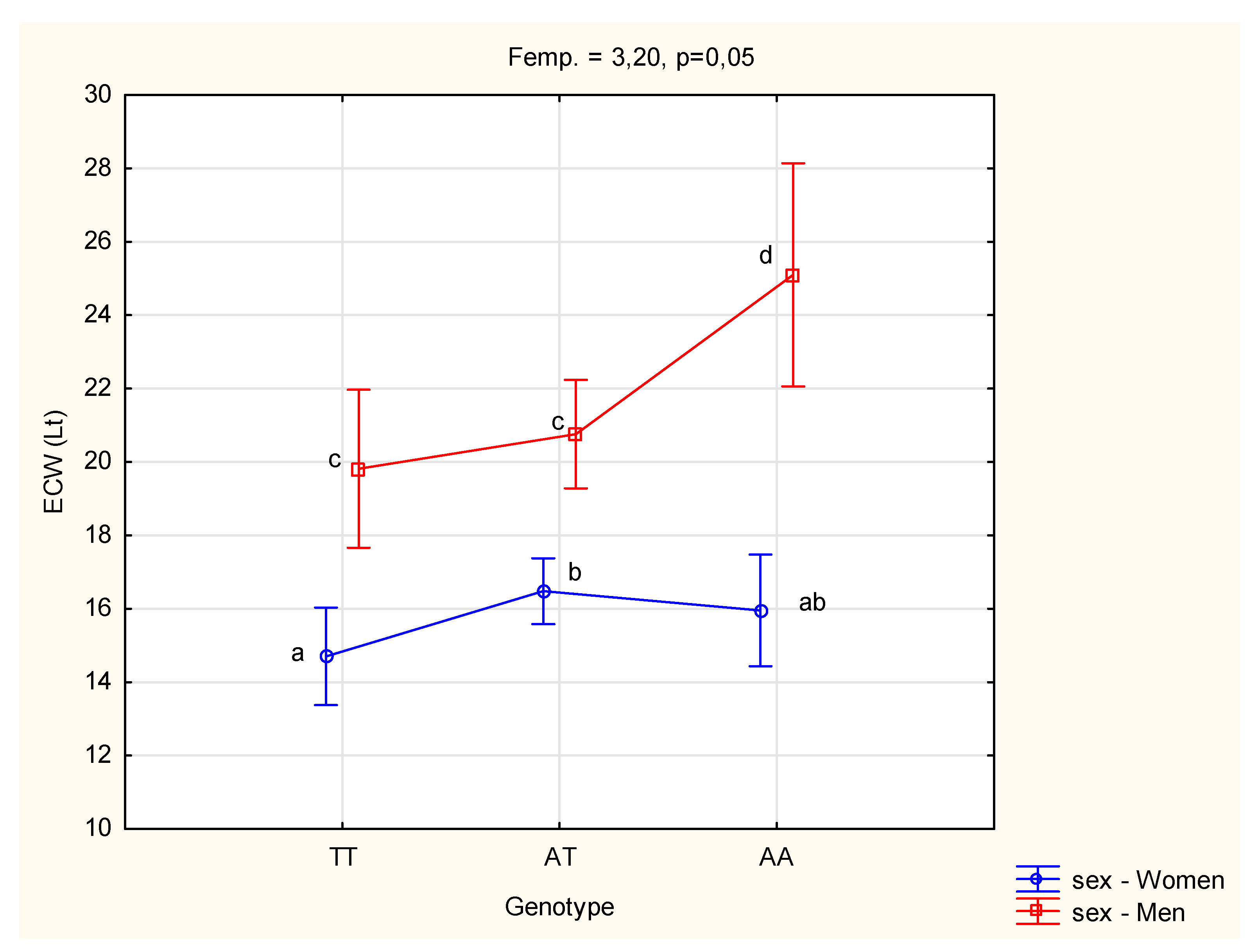

3.2. Genotype and Nutritional Status

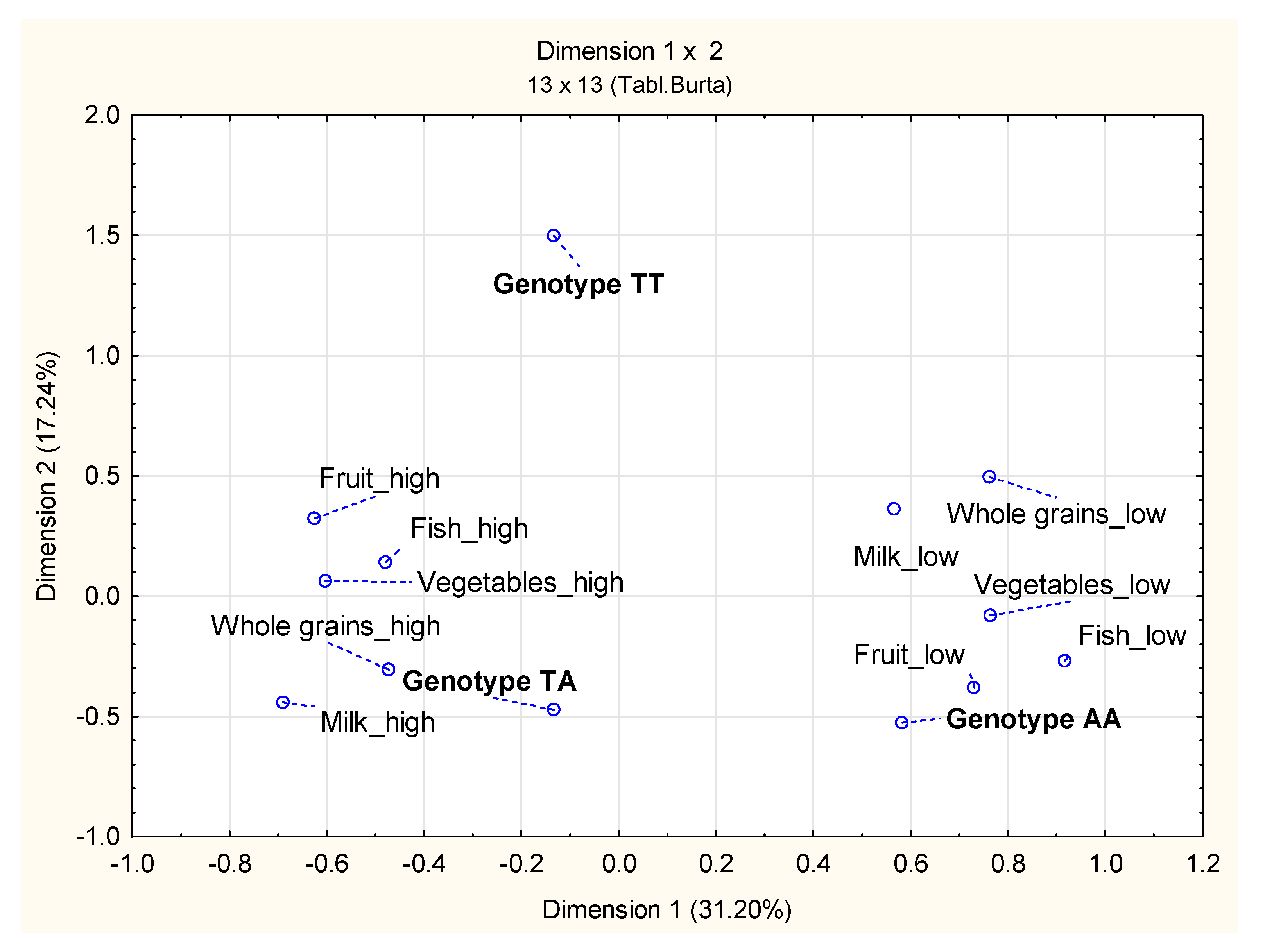

3.2. Genotype and Dietary Charactetistics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet 2024, 403, 1027-1050.

- World Obesity Federation. World Obesity Atlas 2024. World Obesity Federation, London, 2024.

- Chong, B., Jayabaskaran, J., Kong, G., Chan, Y. H., Chin, Y. H., Goh, R., Kannan, S., Ng, C. H., Loong, S., Kueh, M. T. W., Lin, C., Anand, V. V., Lee, E. C. Z., Chew, H. S. J., Tan, D. J. H., Chan, K. E., Wang, J. W., Muthiah, M., Dimitriadis, G. K., Hausenloy, D. J., … Chew, N. W. S. Trends and predictions of malnutrition and obesity in 204 countries and territories: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine, 2023, 57, 101850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101850. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25031882. [CrossRef]

- Tiffany M. Powell-Wiley, Paul Poirier, Lora E. Burke, Jean-Pierre Després, Penny Gordon-Larsen, Carl J. Lavie, MD, Scott A. Lear, Chiadi E. Ndumele, Ian J. Neeland, Prashanthan Sanders, Marie-Pierre St-Onge. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2021, 143, e984-e1010 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000973. [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; Irfan, W.; Jameel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 485. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Xiling Xu, Cunchuan Wang, Susie Cartledge, Ralph Maddison, Sheikh Mohammed Shariful Islam, Association of overweight and obesity with obstructive sleep apnoea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Medicine, 2020, 17, 100185. [CrossRef]

- Okunogbe A, Nugent R, Spencer G, Powis J, Ralston J, Wilding J. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for 161 countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2022, 7(9), e009773. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009773. [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, P.; Adamska-Patruno, E.; Bauer, W.; Fiedorczuk, J.; Krasowska, U.; Moroz, M.; Gorska, M.; Kretowski, A. The Impact of FTO Genetic Variants on Obesity and Its Metabolic Consequences is Dependent on Daily Macronutrient Intake. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3255. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113255. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, H. Obesity: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 706978. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.706978. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Duan H, Tian X, Xu C, Wang W, Jiang W, et al. Genetics of Obesity Traits: A Bivariate Genome-Wide Association Analysis. Front Genet, 2018, 9, 179. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00179. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Ch.; Chen, W.; Wang, X. Studies on the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene and its impact on obesity-associated diseases. Genes & Diseases, 2023, 10, 2351e2365. [CrossRef]

- Hinney A, Nguyen TT, Scherag A, et al. Genome wide association (GWA) study for early onset extreme obesity supports the role of fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) variants. PLoS One, 2007, 2(12), e1361. [CrossRef]

- Speakman JR. The ‘fat mass and obesity related’ (FTO) gene: mechanisms of impact on obesity and energy balance. Curr Obes Rep, 2015, 4(1), 73e91.

- Locke, A., Kahali, B., Berndt, S. et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature, 2015, 518, 197–206 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14177. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L. J., Zhu, H., He, H., Wu, K. H., Li, J., Chen, X. D., ... & Deng, H. W. Replication of 6 obesity genes in a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies from diverse ancestries. PLoS One, 2014, 9(5), e96149. [CrossRef]

- Gao X, Shin Y-H, Li M, Wang F, Tong Q, Zhang P. The Fat Mass and Obesity Associated Gene FTO Functions in the Brain to Regulate Postnatal Growth in Mice. PLoS ONE 2010, 5(11): e14005. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014005. [CrossRef]

- Chen X., Luo Y., Jia G., Liu G., Zhao H., Huang Z. FTO promotes adipogenesis through inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in porcine intramuscular preadipocytes. Anim Biotechnol, 2017, 28(4), 268–274.

- Wu R., Liu Y., Yao Y., et al. FTO regulates adipogenesis by controlling cell cycle progression via m6A-YTHDF2 dependent mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2018, 1863(10), 1323–1330.

- Jiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Xu, J.; Qin, L. The Fto Gene Regulates the Proliferation and Differentiation of Pre-Adipocytes in Vitro. Nutrients 2016, 8, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8020102. [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, L.; Fernando Javier Luna, Jeremías Zubrzycki, Hernán Dopazo, Magalí Pellon-Maison. Associations Between rs9939609 FTO Polymorphism With Nutrient and Food Intake and Adherence to Dietary Patterns in an Urban Argentinian Population. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2024, 124, 874-882. [CrossRef]

- Rahimlou, M., Ghobadian, B., Ramezani, A. et al. Fat mass and obesity-associated gene (FTO) rs9939609 (A/T) polymorphism and food preference in obese people with low-calorie intake and non-obese individuals with high-calorie intake. BMC Nutr, 2023, 9, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-023-00804-y. [CrossRef]

- Madrigal-Juarez, A.; Erika Martínez-López, Tania Sanchez-Murguia, Lisset Magaña-de la Vega, Roberto Rodriguez-Echevarria, Maricruz Sepulveda-Villegas, Rafael Torres-Valadez, Nathaly Torres-Castillo; FTO genotypes (rs9939609 T>A) are Associated with Increased Added Sugar Intake in Healthy Young Adults. Lifestyle Genomics, 2023, 16(1), 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1159/000534741. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Mei, H., Lin, Q., Wang, J., Liu, S., Wang, G., & Jiang, F. Interaction effects of FTO rs9939609 polymorphism and lifestyle factors on obesity indices in early adolescence. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract, 2019, 13(4), 352–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2019.06.004. [CrossRef]

- Labayen, I., Ruiz, J. R., Huybrechts, I., Ortega, F. B., Arenaza, L., González-Gross, M., Widhalm, K., Molnar, D., Manios, Y., DeHenauw, S., Meirhaeghe, A., & Moreno, L. A. Dietary fat intake modifies the influence of the FTO rs9939609 polymorphism on adiposity in adolescents: The HELENA cross-sectional study. NMCD, 2016, 26, 937–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2016.07.010. [CrossRef]

- Susmiati, Nur Indrawaty Lipoeto, Ingrid S. Surono and Jamsari Jamsari, Association of fat mass and obesity-associated rs9939609 polymorphisms and eating behaviour and food preferences in adolescent Minangkabau girls. Pak. J. Nutr., 2018, 17, 471-479. [CrossRef]

- Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 2020, 372, 71. [CrossRef]

- Antropometry Procedures Manual; National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_07_08/manual_an.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- A Healthy Lifestyle—WHO Recommendations. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations (accessed on on 15 July 2025).

- Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio; Report of a WHO Expert Consultation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241501491 (accessed on on 15 July 2024).

- Yoo, E.G. Waist-to-Height Ratio as a Screening Tool for Obesity and Cardiometabolic Risk. Korean J. Pediatr. 2016, 59, 431. [CrossRef]

- Ashwell, M.; Gibson, S. Waist-to-Height Ratio as an Indicator of “Early Health Risk”: Simpler and More Predictive than Using a “matrix” Based on BMI and Waist Circumference. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010159.

- Kunachowicz, H.; Przygoda, B.; Nadolna, I.; Iwanow, K. Tables of Food Composition and Nutritional Values [Tabele Składu i Wartości Odżywczej Żywności]; PZWL: Warsaw, Poland, 2017.

- Niedzwiedzka, E.; Wadolowska, L.; Kowalkowska, J. Reproducibility of A Non-Quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (62-Item FFQ-6) and PCA-Driven Dietary Pattern Identification in 13–21-Year-Old Females. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2183. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone K. M., Brayner B., Celis-Morales C., Moschonis G., Manios Y., Traczyk I., Drevon C. A., Daniel H., Saris W. H. M., Lovegrove J. A., Gibney M., Gibney E. R., Brennan L., Martinez J. A., Mathers J. C. Associations between dietary patterns, FTO genotype and obesity in adults from seven European countries. Eur. J. Nutr, 2022, 61, 2953–2965. [CrossRef]

- Piwonska A. M., Cicha-Mikolajczyk A., Sobczyk-Kopciol A., Piwonski J., Drygas W., Kwasniewska M., Pajak A., Zdrojewski T., Tykarski A., Kozakiewicz K., Ploski R. Independent association of FTO rs9939609 polymorphism with overweight and obesity in Polish adults. Results from the representative population-based WOBASZ study. J. Physiol. Pharmacol, 2022, 73, doi: 10.26402/jpp.2022.3.07. [CrossRef]

- Ağagündüz D., Gezmen-Karadağ M. Association of FTO common variant (rs9939609) with body fat in Turkish individuals. Lipids Health Dis, 2019, 18, 1, s. 212. [CrossRef]

- Mehrdad M., Fardaei M., Fararouei M., Eftekhari M. H. The association between FTO rs9939609 gene polymorphism and anthropometric indices in adults. J. Physiol. Anthropol, 2020, 39, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lan N., Lu Y., Zhang Y., Pu S., Xi H., Nie X., Liu J., Yuan W. FTO – A Common Genetic Basis for Obesity and Cancer. Frontiers in Genetics, 2020, 11, 559138.

- Frayling, T.M. Genome – wide association studies provide new insights into type 2 diabetes aetiology. Nature Review Genetics, 2007, 8 (9), 657–662. [CrossRef]

- Chang Y., Liu, P., Lee, W., Chang, T., Jiang, Y., Li, H. Common variation in the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene confers risk of obesity and modulates BMI in the Chinese population. Diabetes, 2008, 57, 2245–2252. [CrossRef]

- Tan J., Dorajoo R. Seielstad, M. Sim, X., Ong R. T., Chia K. FTO variants are associated with obesity in the chinese and malay populations in Singapore. Diabetes, 2008, 57, 2851–2857.

- Li H., Kilpeläinen, T. Liu C. Zhu J., Liu Y., Hu C. Association of genetic variation in FTO with risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes with data from 96,551 east and south Asians. Diabetologia, 2012, 55, 981–995.

- Fonseca A., Abreu G., Zembrzuski V., Junior M., Carneiro J., Neto J. The association of the fat mass and obesity-associated gene (FTO) rs9939609 polymorphism and the severe obesity in a Brazilian population. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity, 2019, 12, 667–684. [CrossRef]

- Gholamalizadeh M., Mirzaei Dahka S., Vahid F., Bourbour F., Badeli M., JavadiKooshesh S., Mosavi Jarrahi S. A., Akbari M. E., Azizi Tabesh G., Montazeri F., Hassanpour A., Doaei S. Does the rs9939609 FTO gene polymorphism affect fat percentage? A meta-analysis. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry, 2020, 128, 6, 1421–1425. [CrossRef]

- Reuter C. P., Rosane De Moura Valim A., Gaya A. R., Borges T. S., Klinger E. I., Possuelo, L. G. (2016): FTO polymorphism, cardiorespiratory fitness, and obesity in brazilian youth. American Journal of Human Biology, 28, s. 381–386. [CrossRef]

- Liang Chen X., Li J., Yan M., Yang Y. Study on body composition and its correlation with obesity: A Cohort Study in 5121 Chinese Han participants. Medicine (Baltimore), 2018, 97, 21, e10722. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010722. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone K., Celis-Morales C., Lara J., Ashor A., Lovegrove J., Martinez J., Saris W., Gibney M., Manios Y., Traczyk I., Drevon C., Daniel H., Gibney E., Brennan L., Bouwman J., Grimaldi K., Mathers J. Associations between FTO genotype and total energy and macronutrients intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev, 2015, 16, 8, s. 666–678. [CrossRef]

- Daya M., Pujianto D. A., Witjaksono F., Priliani L., Susanto J., Lukito W., Malik S. G. Obesity risk and preference for high dietary fat intake are determined by FTO rs9939609 gene polymorphism in selected Indonesian adults. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr, 2019, 28, 1, 183–191. [CrossRef]

- Madrigal-Juarez, A.; Erika Martínez-López, Tania Sanchez-Murguia, Lisset Magaña-de la Vega, Roberto Rodriguez-Echevarria, Maricruz Sepulveda-Villegas, Rafael Torres-Valadez, Nathaly Torres-Castillo; FTO genotypes (rs9939609 T>A) are Associated with Increased Added Sugar Intake in Healthy Young Adults. Lifestyle Genomics, 2023, 16 (1), 214–223. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone K. M., Celis-Morales C., Navas-Carretero S., San-Cristobal R., Forster H., O'Donovan C. B., Woolhead C., Marsaux C. F., Macready A. L., Fallaize R., Kolossa S., Tsirigoti L., Lambrinou C. P., Moschonis G., Godlewska M., Surwiłło A., Drevon C. A., Manios Y., Traczyk I., Gibney E. R., Brennan L., Walsh M. C., Lovegrove J. A., Martinez J. A., Saris W. H., Daniel H., Gibney M., Mathers J. C. Food4Me study. Fat mass- and obesity-associated genotype, dietary intakes and anthropometric measures in European adults: the Food4Me study. Br J Nutr. 2016, 14, 115, 3, s. 440–448. [CrossRef]

- Lusting R., Collier D., Kassotis Ch., Roepke T., Kim M., Blanc E., Barouki R., Bansal A., Cave M., Chatterjee S., Choudhury M., Gilbertson M., Lagadic-Gossmann D., Howard S., Lind L., Tomlinson C., Vondracek J., Heindel J. Obesity I: Overview and Molecular and Biochemical Mechanisms. Biochem. Pharmacol, 2022, 199, 115012. [CrossRef]

| Genotype | Number of people (n) | Women (n) | Men (n) | Percentage of genotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homozygous TT | 29 | 21 | 8 | 25.9 |

| Heterozygous TA | 63 | 46 | 17 | 56.2 |

| Homozygous AA | 20 | 16 | 4 | 17.9 |

| Total | 112 | 83 | 29 | 100.0 |

| Genotype | Number of people with normal body weight | Number of overweight people | Number of people with obesity | Percentage of individuals with excess body weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homozygous TT | 12 | 7 | 10 | 58.6 |

| Heterozygous TA | 15 | 20 | 28 | 76.2 |

| Homozygous AA | 3 | 6 | 11 | 85.0 |

| Total | 30 | 33 | 49 | 73.2 |

| r variance analysis p | Genotype AA Mean ± SD |

Genotype TA Mean ± SD |

Genotype TT Mean ± SD |

Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS* | 170.5 ± 9.32 | 171.6 ±7.91 | 172.5 ± 8.48 | Height [cm] |

| NS | 98.8 ± 22.47 | 84.2 ± 24.38 | 75.3 ± 20.75 | Body weight [kg] |

| NS | 116.0 ± 10.89 | 104.7 ± 14.95 | 98.0 ± 14.65 | Hip circumference [cm] |

| NS | 104.0 ± 17.44 | 90.6 ±19.65 | 85.5 ± 17.08 | Waist circumference [cm] |

| NS | 0.88 ± 0.13 | 0.88 ± 0.12 | 0.87 ± 0.11 | WHR [cm/cm] |

| NS | 0.55 ± 0.10 | 0.56 ± 0.11 | 0.58 ± 0.09 | WHtR [cm/cm] |

| NS | 9.5 ± 2.81 | 8.4 ± 2.69 | 7.7 ± 3.25 | Body cell mass index |

| NS | 38.1 ± 8.11 | 34.3 ± 10.04 | 29.3 ± 9.57 | Fat mass [%] |

| NS | 38.7 ± 11.98 | 31.0 ± 17.64 | 23.5 ± 13.9 | Fat mass [kg] |

| NS | 61.9 ± 14.63 | 65.2 ± 10.57 | 70.7 ± 11.06 | Fat free mass [%] |

| NS | 60.0 ± 8.21 | 53.2 ± 7.43 | 51.7 ± 9.40 | Fat free mass [kg] |

| NS | 46.6 ± 12.51 | 46.3 ± 10.94 | 44.7 ± 13.74 | Cellular mass [%] |

| NS | 28.0 ± 8.21 | 24.7 ± 7.43 | 23.0 ± 9.40 | Cellular mass [kg] |

| NS | 36.1 ± 12.11 | 38.3 ± 10.75 | 39.8 ± 11.02 | Muscle mass [%] |

| NS | 34.7 ± 9.58 | 30.8 ± 8.52 | 28.7 ± 10.75 | Muscle mass [kg] |

| NS | 45.3 ± 5.80 | 47.9 ±7.26 | 51.7 ± 6.58 | Total body water [%] |

| NS | 43.9 ± 10.54 | 39.0 ± 8.03 | 37.8 ± 7.94 | Total body water [Lt.] |

| NS | 45.2 ±4.11 | 45.2 ± 4.14 | 45.7 ± 5.09 | Extracellular water [%] |

| NS | 19.8 ± 4.67 | 17.5 ± 3.84 | 17.2 ± 3.37 | Extracellular water [Lt.] |

| NS | 54.8 ± 4.11 | 54.2 ± 4.56 | 54.3 ± 5.09 | Intracellular water [%] |

| NS | 24.1 ± 6.32 | 21.5 ± 4.90 | 20.6 ± 5.60 | Intracellular water [Lt.] |

| Degree of kinship | Genotype of the studied individual | |

|---|---|---|

| AA | TA & TT | |

| Individual | 18.06 | 61.11 |

| Mother | 8.33 | 38.89 |

| Father | 9.72 | 33.33 |

| Brothers | 1.39 | 27.77 |

| Sisters | 11.11 | 34.73 |

| Sons | 2.78 | 13.89 |

| Daughters | 2.78 | 16.66 |

| Grandchildren | 0.00 | 2.78 |

| Father's brothers | 2.78 | 9.72 |

| Father's sisters | 4.17 | 30.55 |

| Father's father | 1.39 | 1.39 |

| Father's mother | 4.17 | 12.50 |

| Mother's brothers | 2.78 | 15.28 |

| Mother's sisters | 0.00 | 19.45 |

| Mother's father | 1.39 | 5.56 |

| Mother's mother | 4.17 | 20.84 |

| The Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA p | Genotype AA | Genotype TA | Genotype TT | Food product / group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me | SD | Mean | Me | SD | Mean | Me | SD | Mean | ||

| NS* | 2.0 | 1.87 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 1.86 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 1.83 | 2.4 | Sugar for sweetening drinks |

| NS | 3.0 | 1.31 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.36 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 1.16 | 2.6 | Honey |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.87 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 0.87 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 1.03 | 3.3 | Chocolates, chocolate candies and bars |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.94 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 1.05 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 0.82 | 2.4 | Non-chocolate candies |

| 0.088 | 3.0 | 0.91 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.93 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 2.7 | Biscuits and biscuits |

| 0.068 | 2.0 | 0.94 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 0.77 | 2.5 | Ice cream and pudding |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.96 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 1.01 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 1.08 | 2.6 | Salty snacks |

| NS | 4.0 | 1.05 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 1.34 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 3.9 | Milk and natural milk drinks |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.99 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 1.19 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.23 | 2.5 | Sweetened milk drinks |

| NS | 4.0 | 0.68 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 0.89 | 3.3 | Natural cottage cheese |

| NS | 1.0 | 0.98 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.94 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.93 | 2.0 | Flavoured cottage cheese |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.77 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 0.96 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 1.04 | 3.4 | Cheese |

| NS | 4.0 | 0.83 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 0.86 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.82 | 3.8 | Eggs and egg dishes |

| NS | 5.0 | 0.73 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 0.98 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 0.91 | 4.6 | Wholemeal bread or bread with grains |

| NS | 3.0 | 1.37 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 1.22 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 1.12 | 3.0 | Refined bread |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.99 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 0.82 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 0.76 | 2.8 | Coarse-grained groats, unrefined |

| 0.019 | 3.0 | 0.82 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0.83 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 0.78 | 2.9 | Fine-grained refined groats |

| 0.087 | 1.0 | 0.51 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 0.96 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.81 | 1.9 | Ready-made breakfast cereal products |

| NS | 4.0 | 1.16 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 0.89 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 1.06 | 4.0 | Oil, all types |

| NS | 4.0 | 1.36 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 1.15 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 0.82 | 4.2 | Butter |

| NS | 2.0 | 1.45 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 1.44 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 1.47 | 2.8 | Margarine, all types |

| NS | 3.0 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 0.94 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 3.3 | Cream, all types |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.51 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 0.87 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.79 | 1.7 | Other animal fats |

| NS | 2.0 | 1.16 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 0.95 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.04 | 2.6 | Mayonnaise and dressings |

| NS | 4.0 | 1.0 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 0.91 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 1.07 | 4.7 | Fruits, all kinds |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.84 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 0.84 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 0.89 | 3.7 | Kiwi and citrus |

| 0.047 | 2.0 | 1.11 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 0.86 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.98 | 3.0 | Tropical fruits other |

| 0.054 | 2.0 | 0.96 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 0.76 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.99 | 3.2 | Berries |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 0.88 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 0.82 | 3.6 | Bananas |

| NS | 4.0 | 0.76 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 0.85 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 1.04 | 3.9 | Apples and pears |

| 0.074 | 2.0 | 0.92 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.93 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.84 | 2.3 | Avocado |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.97 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 0.86 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 1.14 | 2.3 | Olives |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.93 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 0.75 | 2.2 | Dried fruit |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.83 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.93 | 2.1 | Sweet fruit preparations and candied fruit |

| NS | 4.0 | 0.96 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 0.88 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 1.21 | 4.7 | Vegetables, all types |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.76 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 0.82 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 3.6 | Cruciferous vegetables |

| 0.038 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 0.78 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.97 | 3.8 | Yellow-orange vegetables |

| NS | 4.0 | 0.63 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.89 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.96 | 3.8 | Leafy green vegetables |

| NS | 4.0 | 0.94 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 0.98 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 1.02 | 4.0 | Tomatoes |

| 0.098 | 4.0 | 1.01 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 0.75 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 0.63 | 3.7 | Vegetables like cucumber |

| NS | 4.0 | 0.68 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 0.79 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.6 | 3.8 | Root and other vegetables |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.77 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 0.68 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 0.76 | 2.6 | Fresh and canned legumes |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.81 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 0.82 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.87 | 2.6 | Dry legumes |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.92 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 0.78 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 0.65 | 3.6 | Potatoes |

| NS | 2.0 | 1.22 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.05 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 1.06 | 3.0 | Nuts |

| NS | 3.0 | 1.27 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 1.17 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 1.08 | 3.1 | Grain |

| NS | 3.0 | 1.03 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 0.96 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 0.94 | 3.2 | Sausage |

| NS | 4.0 | 1.07 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 1.11 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 4.0 | High-quality cold cuts |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.87 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.79 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.68 | 2.0 | Organ meat and sausage |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.82 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 0.65 | 2.6 | Red meat |

| NS | 4.0 | 0.96 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 0.73 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 0.86 | 3.4 | Poultry and rabbit meat |

| NS | 1.0 | 0.32 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.41 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.2 | Game meat |

| 0.052 | 2.0 | 0.76 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 0.76 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 2.8 | Lean fish |

| NS | 3.0 | 0.96 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.09 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.91 | 3.1 | Oily fish |

| NS | 3.0 | 1.24 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0.94 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0.76 | 2.9 | Fruit juices and fruit nectars |

| NS | 3.0 | 1.12 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 0.96 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 0.97 | 2.8 | Vegetable and vegetable and fruit juices |

| NS | 1.0 | 1.27 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.15 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.04 | 2.1 | Energy drinks |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.75 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.91 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.96 | 2.2 | Sweetened drink |

| NS | 2.0 | 1.18 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.01 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 0.98 | 2.7 | Beer |

| NS | 2.0 | 1.15 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 1.14 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.08 | 2.6 | Wine and drinks |

| NS | 2.0 | 0.96 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.73 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.73 | 2.0 | Vodka and spirits |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).