1. Introduction

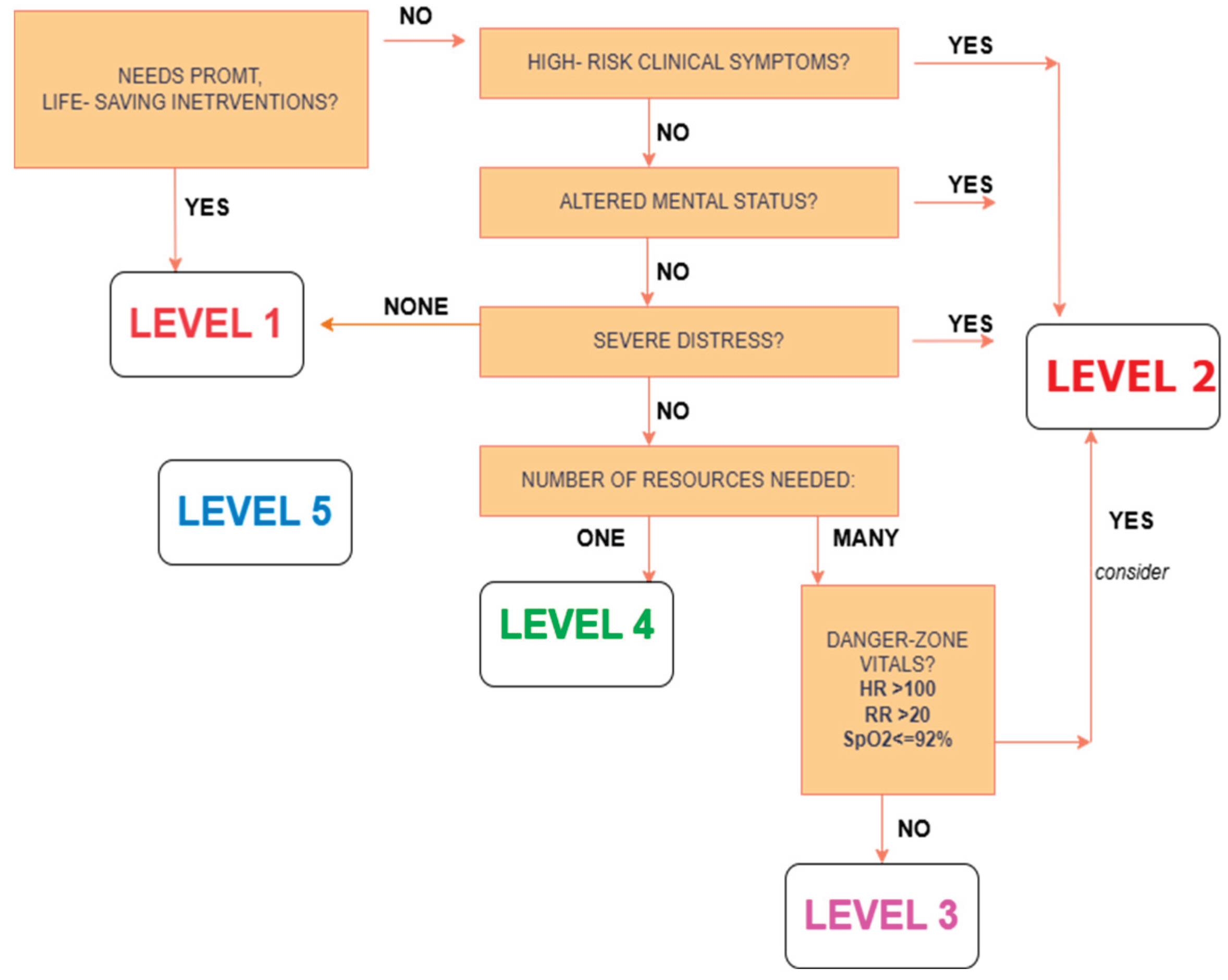

In emergency departments (EDs), triage is essential for setting patient treatment priorities according to severity, which has a direct impact on results and resource utilization. From Level 1 (most urgent) to Level 5 (least urgent), the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), a commonly used five-level framework, aids doctors in rapidly determining acuity. Mistakes may originate from conventional triage, which is nurse-subjective based on vital signs, symptoms, and histories. Manual ESI assignments in 2022 had a 15.3% error rate and a 6.8% rate of under-triage, potentially leading to delayed critical care. Machine learning models have become effective tools for enhancing the precision and reliability of triage.

These algorithms enable automation of severity prediction by analyzing factors like vital signs, chief complaints, and demographics. In a 2024 review of 60 studies, ML models like XGBoost and deep neural networks performed better than human triage, with an average AUC of 0.88 with 23.4% of models achieving 0.95. For instance, a machine learning model in 2021 reduced mis-triage from 1.2% to 0.9% with an AUC of 0.875, whereas a gradient-boosting model in 2023 reduced wait time for urgent patients by 12.4% with a correctness of 87.5%. Still, there are challenges. Most ML models are not interpretable, do not generalize well to diverse populations, and encounter practical computational hurdles to real-time ED integration. These concerns emphasize the demand for more efficient, interpretable, and clinically flexible triage solutions.

History of Triage began with 18th-century war surgeons like Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, who developed systems to prioritize wounded soldiers for expedited treatment, a concept later applied to civilian emergency departments globally [

1].

START (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment) is most commonly employed in United States for adults, with rapid evaluation (under 60 s) based on pulse, respiratory rate, capillary refill, bleeding, and ability to follow commands. For children, the Jump START system adjusts the START algorithm to consider children’s greater vulnerability to respiratory failure and poor ability to comply with commands [

2]. In U.S. emergency departments, the most employed measure for hospital emergency triage is Emergency Severity Index (ESI).

The ESI is a five-level system which initially emphasizes the identification of those patients in whom there are immediate life-threatening interventions required (Level 1), assessment for critical findings like airway patency, breathing, and circulation, and significant alteration in mental status. If the patient is not a Level 1, follow-up questions prompt the nurse to evaluate whether the patient is in an acute high-risk state, confused, lethargic, disoriented, or in acute pain/distress (Level 2). Clinical practice on the part of the nurse is valuable in noticing subtle presentations of a deteriorating acceleration [

3,

4]. For non-Level 1 and 2 patients, the ESI algorithm then considers the estimated number of hospital re-sources to be deployed for their treatment (Level 3: two or more resources; Level 4: one resource; Level 5: no resources). Unstable vital signs in patients requiring more than one resource al-so raise their ESI level to 2 [

5,

6]. The definition of “resources” may vary slightly between institutions, but examples most commonly include laboratory tests, imaging, par-enteral therapy medications, and consultations [

7,

8]. The ESI system, as revised, has shown improvements in the expression of inpatient acuity and resource utilization [

9]. The START triage protocol is also used here, where ambulatory patients are labeled “minor” (green tag) and non-ambulatory patients are assessed according to RPM (Respirations, Perfusion, Mental status) and ranked as “immediate” (red tag), “delayed” (yellow tag), or “deceased” (black tag). Another, SALT (Sort, Assess, Life-saving interventions, and Treatment/Transport) triage, is similar to START but includes an internal question of the patient’s chances to survive according to resources present, and allowing greater latitude in decision-making and even leading to an “expectant” category. The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS), inspired by the ATS, is also a five-level system involving the presentation of patient complaints and uses “first and second-order modifiers” (e.g., vital signs, pain scores, mechanism of injury, com-plaint-specific modifiers) to adjust initial acuity levels [

9].

In China, the Chinese Four-level and Three District Triage Standard categorizes patients at four levels of acuity and assigns them to “red,” “yellow,” and “green” treatment zones based on seriousness [

10] In other countries outside the U.S., several other widely recognized triage systems exist.

The Australasian Triage Scale (ATS), formerly the International Triage Scale (ITS), is the five-category scale adopted as national standard in Australia and offers the performance reporting framework for EDs. It combines patient problems, appearance, and physiological observations based on 79 clinical descriptors to group urgency and respective waiting times [

10,

11]. The Manchester Triage System (MTS), common in Europe, is distinguished by use of 52 flowcharts by presenting complaint, with “discriminators” that direct nurses to categorize patients into five levels of urgency correlating with optimal waiting times [

12,

13,

14]. Traditional ML models [

15,

16] have met with limited success in triage, with accuracies purported to be approximately.75.9%. The models tend to lack the accuracy and flexibility required for heterogeneous, complex ED populations (17). A comparative study conducted in 2023 among supervised ML models and nine techniques reported that Random Forest had the best performance with 89.1% accuracy, 89.0% precision, and 89.1% recall, yet it is still far from optimal performance in triage critical tasks (Supervised ML for triage). In addition, most current models are not capable of giving actionable insights, which restricts their applicability to clinicians who need explainable decision-making pathways in order to act on significant risk factors. Reinforcement learning, which is particularly good at optimizing decisions in dynamic environments, presents a promising solution but has been underutilized in triage domains. But applying it directly to predict ESI is very limited, so there is a knowledge gap this study attempts to fill by using the new SXI++ framework that was combined with interpretable decision trees. Past studies have utilized machine learning (ML) for tackling the intricacy of emergency department (ED) triage, especially that of patient acuity prediction to enhance resource allocation. Current models tend to lack in understanding the function of clinical parameters, evaluating the performance of triage based on various care timelines, and providing pre-training-free, generalized solutions. This work tries to fill these voids by developing and validating a sophisticated ED triage prediction framework with the aims of:

Assessing SXI++ as a bivariate scorer for triage accuracy-based binary ESI classification using strong preprocessing and feature engineering,

Scaling up SXI++ scoring to synchronize with triage accuracy for immediate, short-term, and long-term care, and

Using a decision tree model to determine key indicators (e.g., heart rate, oxy-gen saturation, chest pain) influencing best ESI classification pathways.

Through synchronized predictive outputs across triage scenarios, the study suggests an integrated, explainable model to enhance patient prioritization, utilization of resources, and overall clinical outcomes in EDs.

2. Materials and Methods

This study uses a retrospective dataset of adult ED visits from three Yale New Haven Health System hospitals (one academic and two community) between March 2014 and July 2017 [

18]. It contains 560,486 encounters, of which 100,000 records were chosen at random. Each record originally contained 972 variables, sourced from electronic health records. After preprocessing to remove missing or low-value features, 180 clinically relevant variables were retained, covering demographics, triage vitals, medical history, and binary chief complaints. The Emergency Severity Index (ESI), a target variable, was reduced to two classes: emergency (Levels 1-2) and non-emergency (Levels 3–5).

For prediction, Sriya.AI’s SXI++ framework was employed. It uses a patented deep neural network that dynamically adjusts feature relevance in conjunction with ensemble learning [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Weights based on correlation were used to construct the original SXI score, which was then improved using LASSO (24) regression and combined with importance ratings from PCA [

25], mutual information [

26], XGBoost [

27], and Naïve Bayes [

28]. Predictive accuracy was further increased by prioritizing often essential features using a proprietary kernel initializer in a custom neural network. In order to offer interpretable, rule-based outputs that highlight important clinical signs like low oxygen or abnormal vitals, decision tree classifiers were also integrated.

SXI++ outperformed baseline models—including traditional machine learning algorithms, amongst which we found that an XGBoost-based classifier performed the best, and the original SXI baseline model—achieving near-perfect accuracy, precision, and AUC. To validate its scalability, SXI++ was tested on a second dataset of 1,267 adult ED cases from two additional hospitals (Oct 2016–Sept 2017), which confirmed its adaptability across varying data scopes and triage environments (Emergency Services) [

29].

In conclusion, SXI++ offers a robust, scalable, and clinically interpretable solution for emergency triage prediction by blending machine learning precision with deep learning adaptability.

2.1. Dataset Description

This study makes use of a clinical dataset that has been carefully selected to improve ED triage and lower avoidable hospitalizations. Its foundation is a stratified random sample of 100,000 patient records drawn from a larger real-world database that includes 972 variables and 560,486 interactions from a busy emergency room. The Emergency Severity Index (ESI), a five-level national triage system, is the main prediction aim. ESI levels were divided into two groups for binary classification:

This binary division supports the evaluation of classification models in identifying high-risk versus low-risk patients. From the original 972 features, preprocessing and expert-guided dimensionality reduction narrowed the dataset to 180 highly relevant clinical variables across four major dimensions:

Demographics: age, gender, arrival mode (e.g., ambulance, walk-in), and prior healthcare usage

Triage vital signs: heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, and oxygen saturation

Clinical history: presence or absence of chronic conditions (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular disease)

Chief complaints: binary indicators of reported symptoms (e.g., dizziness, abdominal pain)

Features with over 50% missing data or limited clinical relevance were removed, reducing the set from 792 to 180 columns. This refined dataset balances predictive power with interpretability. The resulting class distribution reflects a moderate imbalance, as detailed in

Table 1.

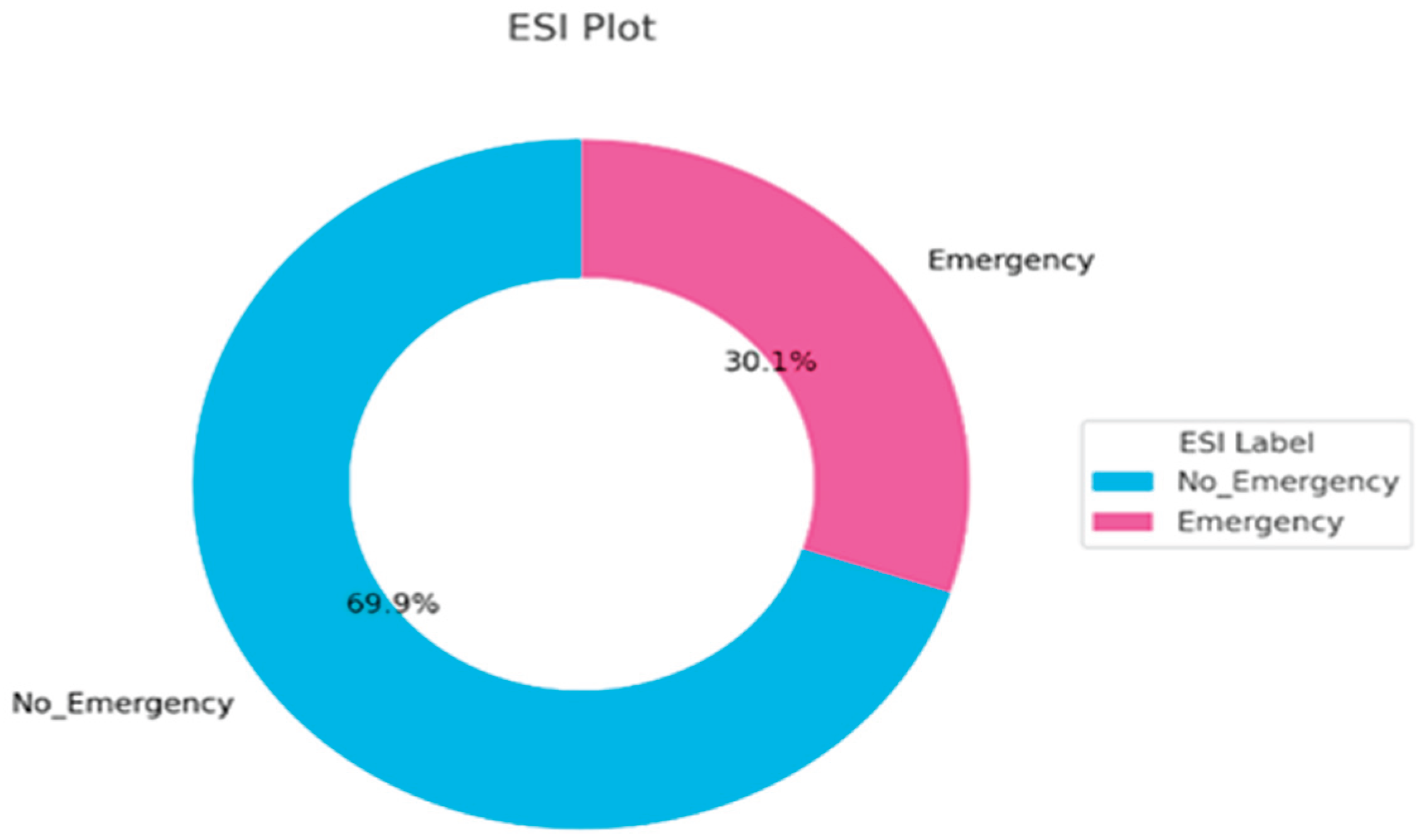

This distribution (

Figure 1) is indicative of actual patient inflow patterns and requires strategies for handling class imbalance when training models, including weighted loss functions or oversampling methods.

Most importantly, this dataset is the empirical basis upon which the performance of SXI++, an AI-assisted triage augmentation model created to forecast emergency severity with higher accuracy, will be tested.

Table 2.

Hospital Triage and Patient History Dataset.

Table 2.

Hospital Triage and Patient History Dataset.

| FEATURES |

| Target |

ESI |

| Past medical history |

From 2sndarymalig to whtblooddx |

| Demographics |

Age |

| Gender |

| Arrival mode |

| previousdispo |

| Triage Vital Signs |

triage_vital_hr |

| triage_vital_rr |

| triage_vital_sbp |

| triage_vital_temp |

| triage_vital_o2 |

| triage_vital_dbp |

| Chief Complaints |

From cc_abdominalcramping to cc_wristpain |

2.2. Interpretation of ESI Distribution

The donut chart named ESI Plot in

Figure 2. visually illustrates the binary case classification of patients into two groups:

Figure 2.

ESI Distribution based on SXI.

Figure 2.

ESI Distribution based on SXI.

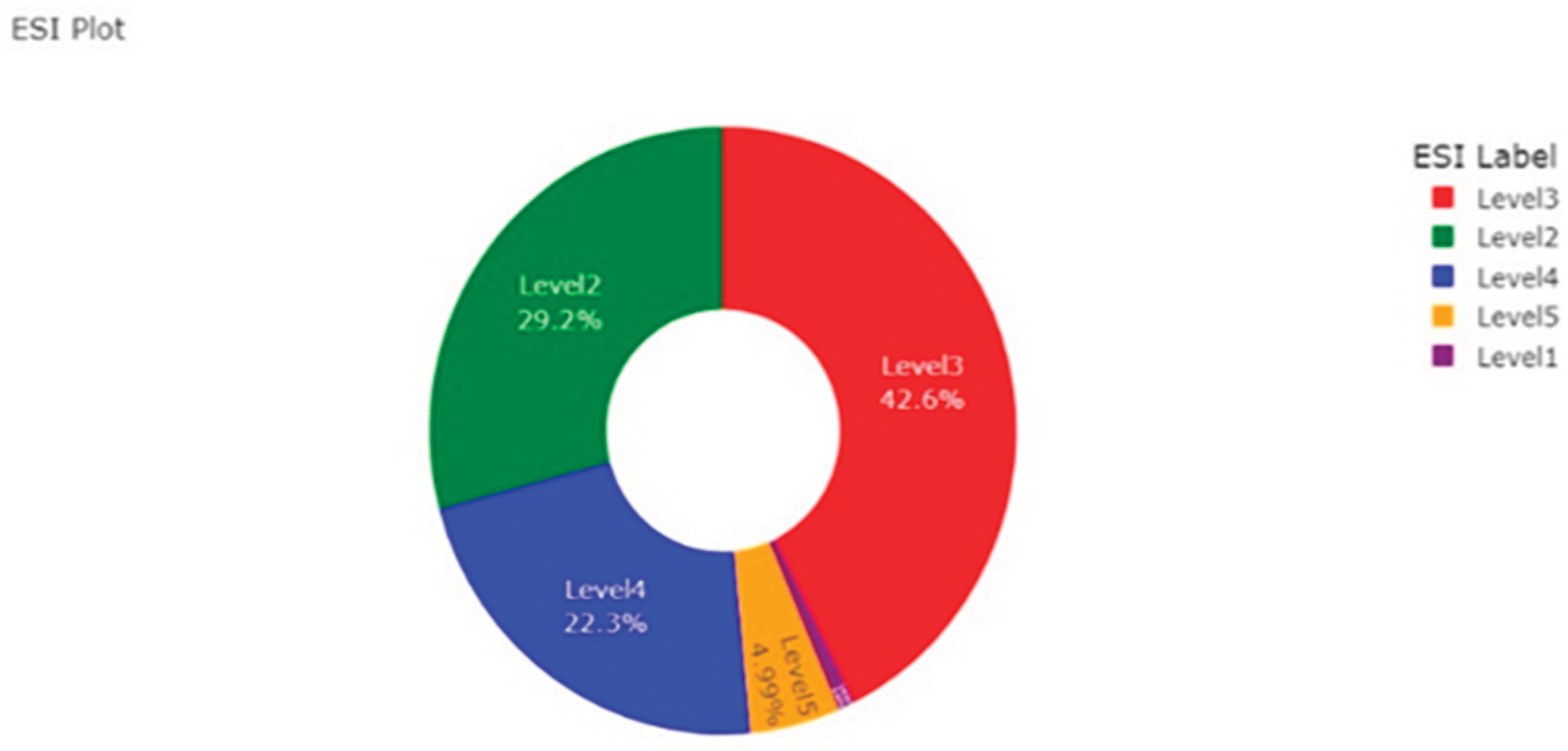

Figure 3.

ESI Distribution based on SXI.

Figure 3.

ESI Distribution based on SXI.

This preprocessing reduces the initial multi-level ESI classification to the binary label that the SXI++ model utilizes. The graph shows that about 70% of the cases did not classify as emergencies and about 30% were indicated as emergency cases. This clear demarcation probably serves to help the model concentrate on critical triage predictions.

The initial Emergency Severity Index distribution, prior to binarization, reflects a more dynamic clinical triage environment based on five levels of severity from the entire data gathered (

Table 3):

The ESI distribution reveals that the majority of cases (71.8%) fall under Levels 2 and 3, reflecting moderate to high-acuity patients—those needing urgent, but not immediate, life-saving care. Level 3 alone accounts for the largest portion (42.6%), indicating patients with complex symptoms that require evaluation but are not critically ill. Level 2, at 29.2%, includes patients needing prompt attention, often due to abnormal vital signs or high-risk presentations. In contrast, low-acuity Levels 4 and 5 make up only 27.3%, with Level 5 comprising just 4.99%. Level 1 cases—representing life-threatening emergencies—are extremely rare, likely due to actual rarity or limitations in sampling or documentation.

This distribution highlights the importance of robust triage models like SXI++, capable of accurately distinguishing between closely related levels such as 2 and 3, where misclassification could lead to resource strain or patient harm. The low proportion of Level 5 cases also underscores the need to divert non-urgent patients toward alternative care paths to reduce ED congestion. Overall, the observed ESI pattern supports the clinical relevance of predictive scoring systems and the integration of explainable AI to guide real-time triage in diverse patient populations.

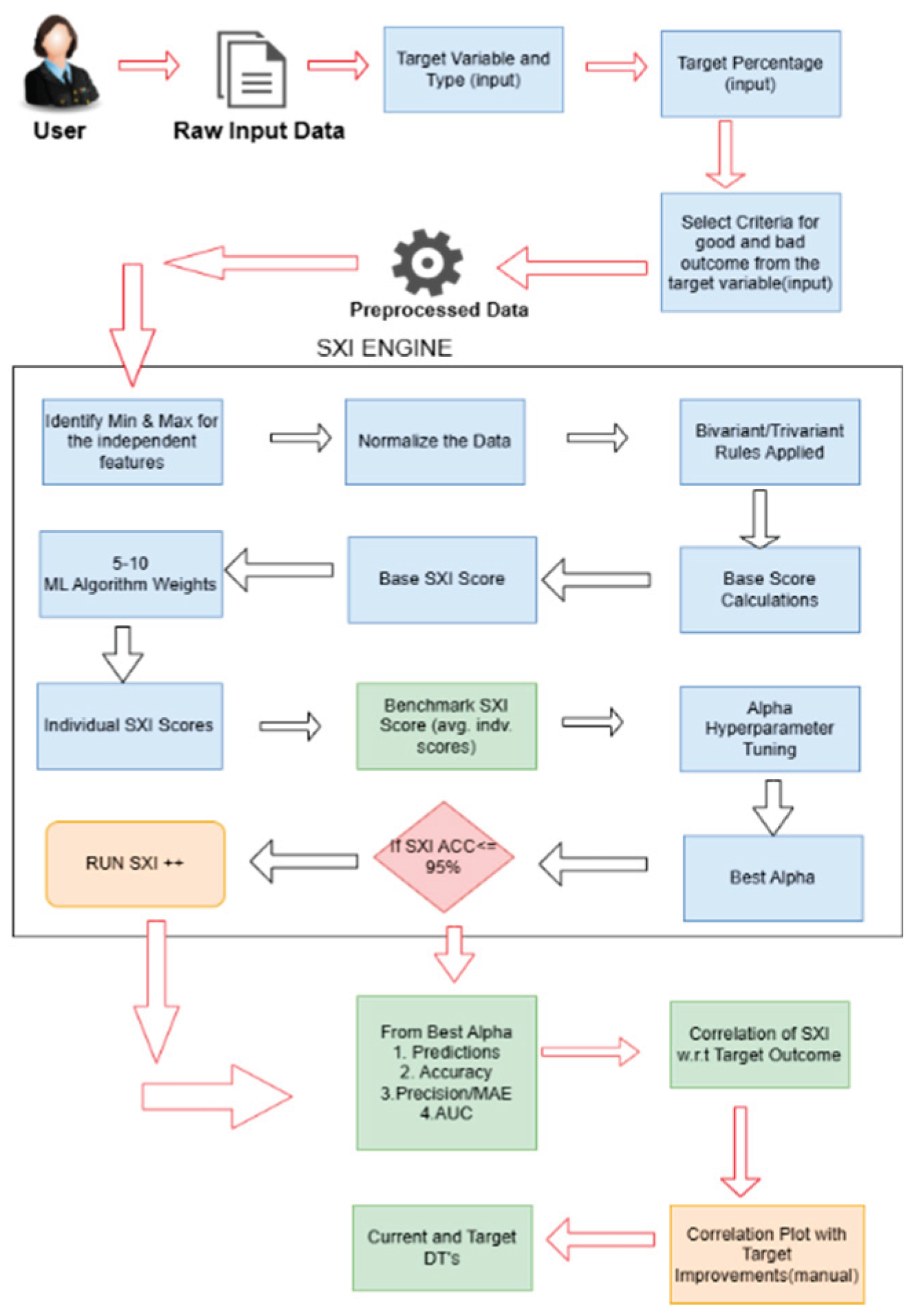

2.3. Method Use

In this research, the method used is SXI++ framework. It is a highly interpretable, machine learning-driven predictive model developed by Sriya.AI to optimize triage decisions in emergency care. It enhances traditional severity evaluations through a multistage pipeline beginning with bivariate correlation analysis, identifying key feature interdependencies and clinical relevance. SXI++ employs an iterative scoring mechanism that integrates machine learning models like XGBoost, LASSO, PCA, Naïve Bayes, and a proprietary deep neural network, which refines predictions via repeated calibration. This ensemble approach dynamically adjusts feature weights using a custom kernel initializer, emphasizing critical clinical markers such as vital signs and chief complaints, leading to accurate SXI++ scores reflecting triage urgency.

The framework ensures interpretability by combining decision trees to generate clinician-friendly diagnostic pathways. For instance, it flags a case as “Emergency” based on patterns like low oxygen saturation with abnormal systolic pressure, aiding transparent prioritization. In large-scale evaluations, SXI++ demonstrated superior performance—achieving 99.8% accuracy and precision, and an AUC of 0.999—far outperforming baseline models. Moreover, SXI++ significantly reduced projected emergency admissions from 99.98% under the current threshold to 35.58% under the optimized one—highlighting its ability to optimize resource use and minimize over triage (

Figure 1). Through Bayesian hyper-parameter tuning and iterative weight calibration, SXI++ consistently refines prediction logic to reduce misclassifications and support real-time deployment in emergency settings [

19].

The SXI++ LNM model reveals actionable insights through feature importance, identifying key drivers such as mode of arrival, blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and chief complaints. Sensitivity analysis confirmed stability across varying parameters, and robust preprocessing allowed improved generalizability across emergency departments. After normalization, features undergo bivariate correlation analysis (

Figure 4) to compute correlation weights, which help identify influential features. These weights guide the computation of base SXI scores using weighted sums of normalized values. Binary flags (Base SXI++ LNM Flags) categorize individual scores based on deviation from the base score.

Lasso regression adjusts min-max mappings of features using coefficients derived from fitting to normalized data and binary flags, ensuring that feature importance is accurately reflected. The model then aggregates weights from algorithms like Naïve Bayes, XGBoost, LASSO, Mutual Information, and PCA to generate a final composite weight for each feature. Features with non-zero weights across all models are used to compute final SXI scores, maximizing reliability and preserving critical information (

Figure 4). Delineation between outcome groups is iteratively improved by comparing updated SXI distributions over time.

The in-house deep neural network is trained using features, target variables, and SXI scores, with emphasis on the five most frequent and important features. A custom kernel initializer modifies the Xavier/Glorot method by scaling weights based on feature frequency and importance. Bayesian optimization tunes hyperparameters like neurons, activations, optimizers, learning rate, and batch size, with stratified k-fold cross-validation ensuring robustness even with limited data. The optimized network is trained with the best parameters, and weights from early layers are used to refine new SXI scores.

Finally, SXI++ uses an iterative weight calibration system to enhance score accuracy. It begins by evaluating performance with initial weights, then tests positive and negative weight adjustments (from 0% to beyond ±100%) to maximize delineation. If no gains are found, a new weight vector is created by boosting the top 5 features from the neural network’s hidden layers, which is adopted for future iterations. This loop continues with recalibrations, penalties, and rewards until the most accurate and delineated SXI scores are achieved.

3. Results

3.1. SXI Distribution

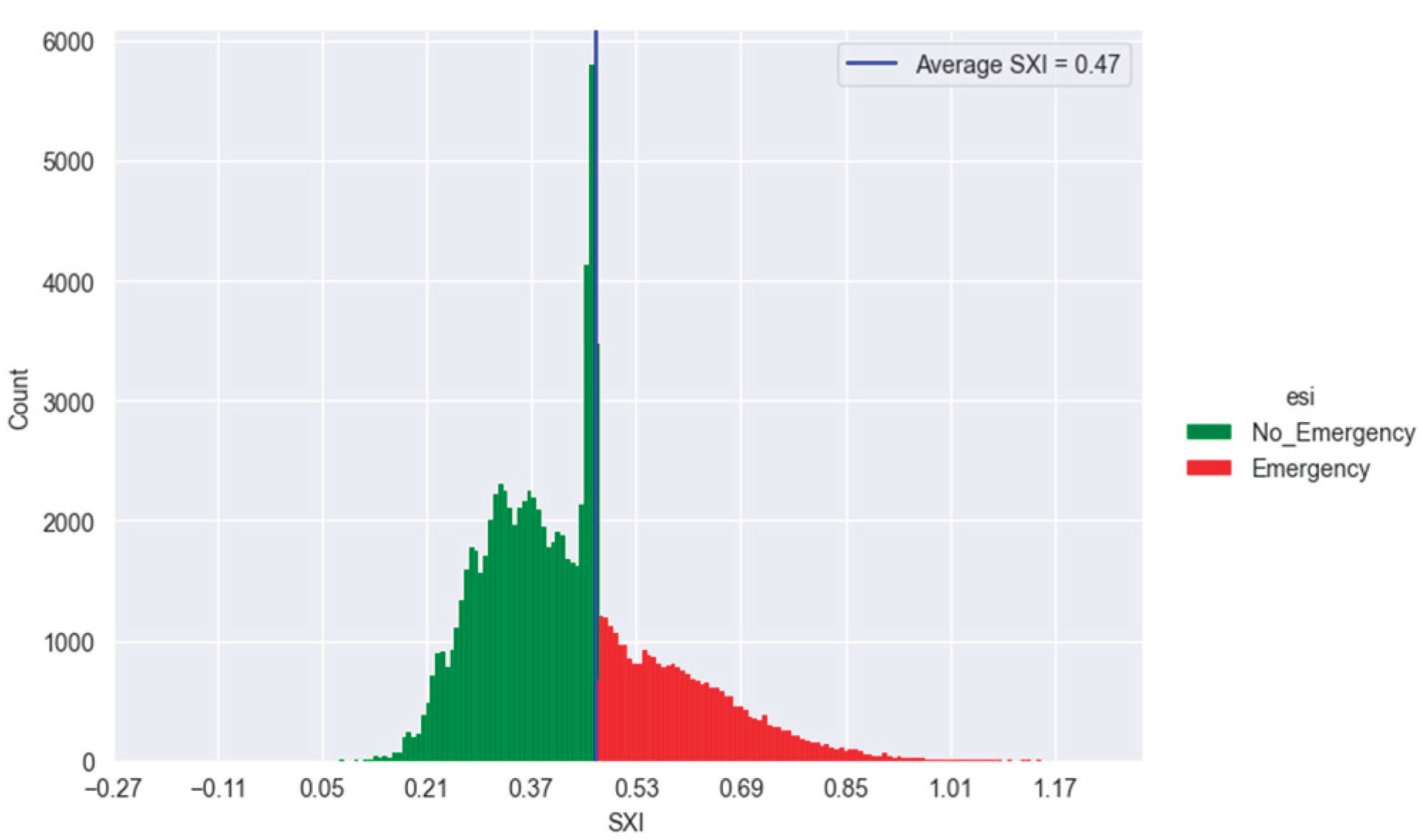

The results of the SXI++ system, detailed in

Figure 5, are based on a curated dataset of 100,000 ED patient records with 180 clinically relevant features to predict Emergency Severity Index (ESI) classifications. Using a benchmark SXI score threshold of 0.47—representing the system-wide cutoff for triage urgency—30.1% of patients were classified as “Emergency” (Levels 1–2) and 69.9% as “Non-Emergency” (Levels 3–5). Among Emergency-labelled cases, 99.98% had SXI scores above 0.47, while only 35.58% of patients below the threshold were Emergency.

Table 4 gives the result metrics of the dataset. Another triage dataset with 1,267 adult ED cases were also tested on SXI++ model and the results are shown in

Table 5 below.

3.2. Confusion Matrix

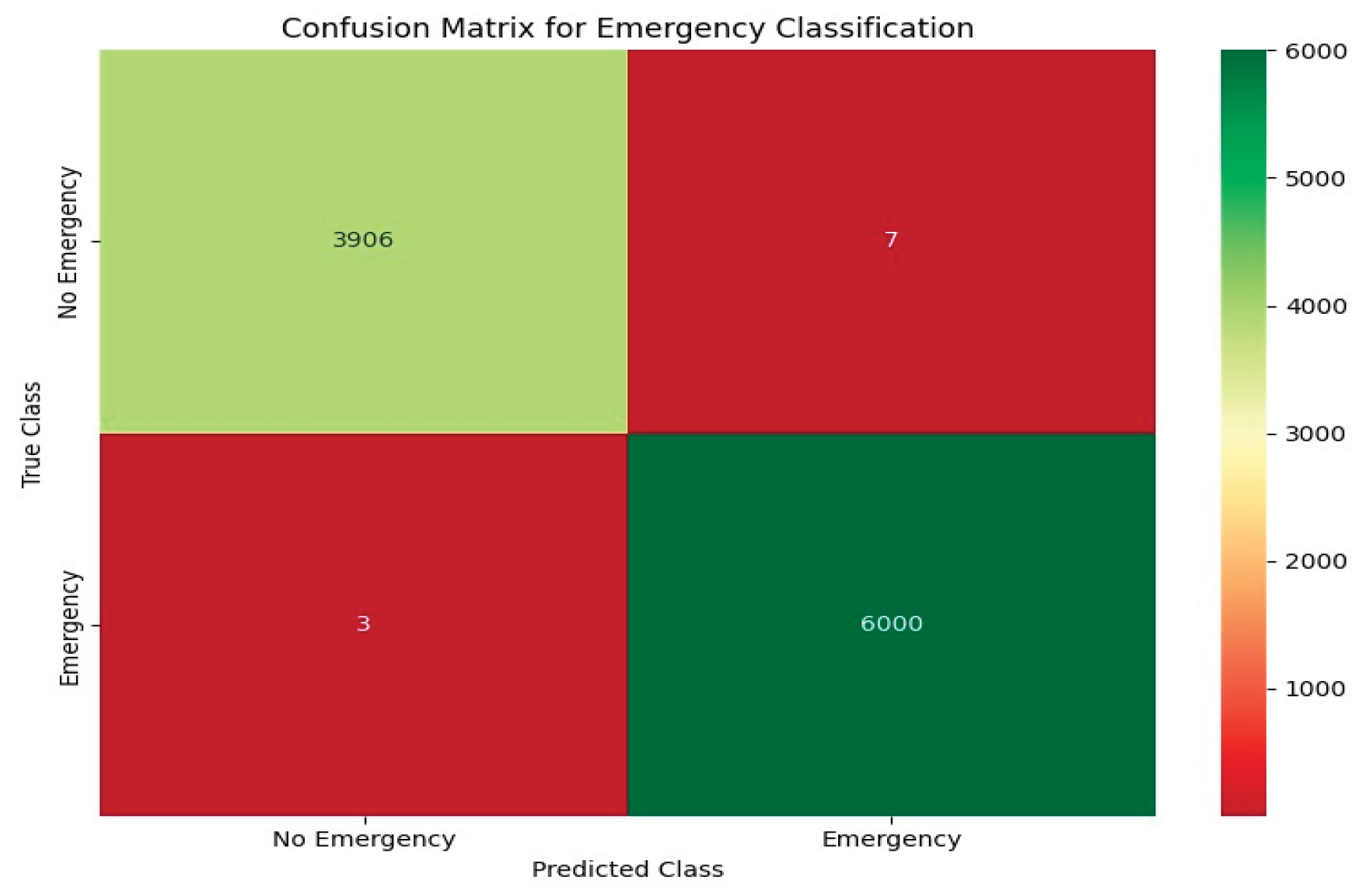

The SXI++ algorithm demonstrated strong discriminatory power in predicting emergency triage outcomes. In a held-out test set of 10,000 records, it accurately identified 6,000 true Emergency cases and 3,906 true Non-Emergency cases, with minimal misclassification. This high sensitivity and specificity support SXI++ as a clinically reliable tool for urgent care prioritization and efficient resource use.

The confusion matrix (

Figure 6) visually confirms this performance, showing mostly accurate predictions (green cells) with very few errors (red cells). Even when validating the test result for another triage dataset the out with SXI are giving perfect results indicating reliability of the model.

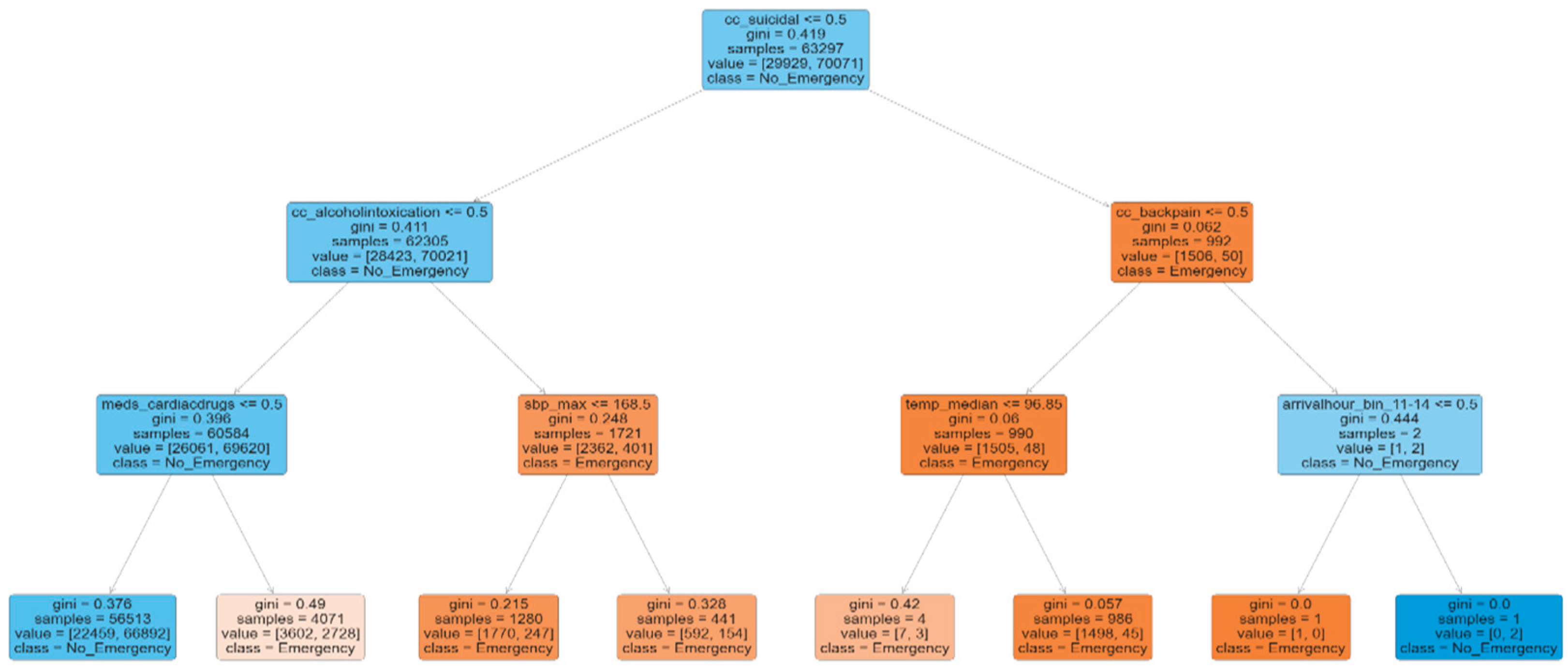

3.3. Current Decision Tree

Figure 7 highlights a decision tree illustrating key predictors of emergency cases at the current SXI score of 0.47, where 30.1% of patients are classified as emergency. Notable indicators of emergency include a high likelihood of suicidal complaints (cc_suicidal > 0.5), back pain as a primary complaint (cc_backpain > 0.5), and elevated body temperature (temp_median > 96.85). These factors contribute to pathways that lead toward an emergency classification. In contrast, patients with low probabilities of suicidal intent (cc_suicidal ≤ 0.5), alcohol intoxication (cc_alcoholintoxication ≤ 0.5), and use of cardiac drugs (meds_cardiacdrugs ≤ 0.5) are more likely to be categorized as non-emergency. The decision tree clearly defines diagnostic paths based on a combination of complaint types and clinical measurements

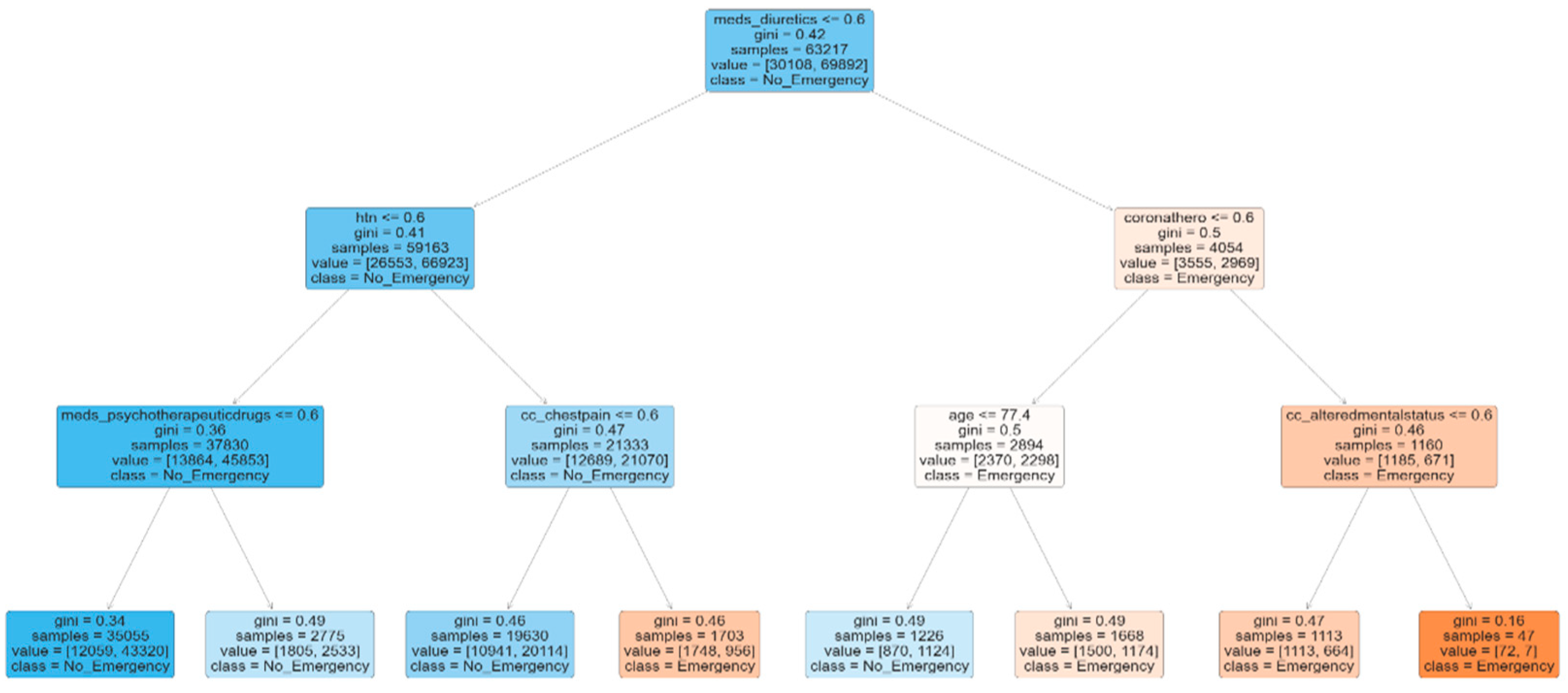

3.4. Target Decision Tree

In contrast,

Figure 8 presents a target decision tree focused on emergency prediction, showing Emergency cases are more likely if patients have high probability of diuretic use (meds_diuretics > 0.6), coronary artery disease (coronathero > 0.6), or altered mental status (cc_alteredmentalstatus > 0.6). Non-Emergency cases had lower probabilities for diuretic use, hypertension, and psychotherapeutic drugs. These rule paths support precise emergency identification.

In the Cleveland Heart Disease dataset (303 patients), 139 (45.87%) had heart disease. By comparing current and target trees, the SXI++ model suggests clinical feature adjustments (e.g., ST depression, angina) that could reduce disease prevalence to 36.70%, offering a framework for targeted clinical intervention.

The SXI++ model was also validated on a second dataset, achieving 98.3% accuracy, 99% precision, and AUC of 0.989, confirming its robustness across different settings.

4. Discussions

4.1. Key Findings

The XGBoost-based triage model shows strong potential for improving emergency department (ED) operations, achieving 82.57% accuracy and high AUC scores across severity levels I–IV (0.9629, 0.9554, 0.9120, and 0.9296, respectively). By analyzing complex patterns in patient data—such as vital signs, chief complaints, and medical history—it offers a more objective and consistent alternative to traditional triage methods like the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), which often rely on subjective judgment and lead to over- or under-triage.

Machine learning has been shown to accurately predict clinical outcomes such as hospital admission, mortality, and critical care needs. Recent advances, especially using models like XGBoost and Gradient Boosting, have significantly enhanced triage prediction. Notably, integrating Natural Language Processing (NLP) to interpret free-text chief complaints has further improved consistency and performance, surpassing ESI’s AUC of 0.843 and reducing real-world mis-triage by up to 0.3%.

These advancements have important implications. Improved triage accuracy enables quicker identification of high-risk patients, reducing treatment delays and improving outcomes in overcrowded EDs. Additionally, explainable AI methods like SHAP and LIME enhance clinician trust by clearly showing how predictors such as arrival mode and vital signs influence decisions. To maximize effectiveness, these models should be embedded in electronic health record (EHR) systems for real-time triage support. This integration can streamline resource allocation and alleviate ED crowding, provided that strong data governance is in place to manage data quality variability.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

Existing machine learning models for emergency department triage, like Random Forests, Gradient Boosting, and Logistic Regression, have increased classification accuracy but frequently struggle with scalability, interpretability, and practical application. Usually based on static feature sets, these models have trouble with class imbalances, particularly in under-represented Level 1–2 emergency cases, and provide no transparency, which undermines clinician confidence and prevents adoption.

The SXI++ framework provides a dynamic, interpretable, and extremely accurate triage model in order to overcome these drawbacks. Adaptively weighting information according to clinical importance, it combines ensemble machine learning with a deep neural network enhanced by reinforcement learning. This makes it possible for SXI++ to model complex, non-linear correlations between historical risk variables, chief complaints, and vital signs. Clinicians can comprehend and confirm emergency classifications because to its decision tree layer, which guarantees interpretability. The system outperformed conventional XGBoost models and demonstrated efficacy in high-stakes triage scenarios, achieving remarkable performance (accuracy: 99.8%, precision: 99.8%, AUC: 0.999) on extensive test datasets.

Beyond predictive strength, SXI++ includes threshold-based scoring that supports operational goals like reducing unnecessary emergency admissions by over 20%. Its capacity to classify patient risk according to metrics such as systolic blood pressure and oxygen saturation complies with clinical guidelines and permits prompt action. Additionally, resilience under moderately imbalanced datasets is improved by the model’s adaptive feature weighting and iterative scoring.

However, SXI++ has the same limitations as other ML systems: it mostly relies on high-quality input data. Reliability may be impacted by inaccurate or insufficient triage metrics, which are frequent in real-time emergency departments. Furthermore, there are questions regarding the model’s generalisability across several hospitals with disparate triage processes because it was trained using retrospective data from a single health system. Validating its scalability and clinical uptake requires integration with live EHR systems and more extensive cross-validation across several ED sites. Furthermore, for deployment and monitoring, the more complex SXI++ modules—such as deep learning and reinforcement learning—may need for specific infrastructure and skilled staff.

In summary, SXI++ represents a significant advancement in automated triage. Its adoption will depend on prospective validation, multi-center evaluation, and seamless integration into emergency department workflows.

4.3. Comparison with Similar Research

Most recent developments in machine learning (ML) have had a large effect on predictive model development meant to improve triage accuracy and prioritization in emergency department (ED) environments. Various research studies have investigated this area based on a range of modeling strategies and data sets. For example, a study of National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) ED data used Lasso regression, random forest, gradient boosting, and deep neural networks to predict critical care admissions and hospitalization outcomes. Of these, the deep neural network identified 0.89 AUC in predicting high-risk cases—better than the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) baseline (AUC = 0.843)—and had 85% accuracy in identifying patients that needed critical care [

30].

In a similar manner, in paediatric triage models, NLP models such as BERT-based ones have been shown very high performance (e.g., AUC = 0.839 for predicting critical outcome). Although these models have high performance, they typically suffer from drawbacks like single-centre bias, non-generalizability, limited interpretability, and vulnerability towards imbalanced dataset distributions [

31].

By contrast, the SXI++ framework proposed in this paper presents an exhaustive and clinically interpretable model, filling the identified gaps of previous work. Leveraging the hybrid architecture that unites ensemble machine learning techniques (e.g., XGBoost, LASSO, Naïve Bayes) with a deep neural network optimized with reinforcement learning, SXI++ reported excellent performance metrics: 99.8% accuracy, 99.8% precision, and AUC of 0.999 in Emergency vs. Non-Emergency patient classification. In contrast to traditional models that depend on static feature engineering, SXI++ dynamically learns feature weights via an iterative scoring framework that improves model sensitivity to changing clinical patterns.

In addition, whereas previous works are typically not interpretable, SXI++ features a decision tree-based interpretability component. This enables clinicians to visualize influential pathways that determine emergency classification—e.g., low oxygen saturation, abnormal systolic blood pressure, and acute chief complaints—thus enhancing model transparency and clinician trust.

Another significant differentiator is the capability of SXI++ to manage moderately imbalanced datasets, which is a typical problem in ED triage modeling. The model’s precision remained high even when Emergency cases were just 30.1% of the dataset, and was able to reduce predicted Emergency rates to 20% through threshold-based optimization, aligning operational objectives of minimizing overcrowding and over triage.

Together, these benefits make SXI++ a more interpretable, robust, and scalable triage system than most previous ML models. Its ability to handle multiple feature types, address class imbalances, and provide real-time, interpretable predictions is an important step forward relative to the previously published triage literature.

Its emphasis on optimizing diagnostic routes and minimizing heart disease incidence shows how it can improve patient outcomes and maximize resource utilization in healthcare facilities.

4.4. Implications, Recommendations, and User Interaction

Implications: The SXI++ algorithm is poised to enhance cardiovascular care through enabling precise heart disease prediction, as proven on the Hospital Triage and Patient History dataset. Its capacity for fusion of clinical features holds potential for extension to various clinical environments, which may raise patient outcomes and maximize resource utilization awaiting further validation in diverse settings. To facilitate greater clinical uptake, subsequent studies ought to:

Recommendations: To enhance clinical adoption, future research should:

Cross-validate SXI++ algorithm on external data, including global and outpatient populations.

Integrate SXI++ algorithm into electronic medical records (EMR) for real-time monitoring and prediction.

Carry out prospective trials to measure its effect on patient outcomes, including the reduction of events associated with heart disease.

User Interaction and Expertise: The SXI++ system has minimal user input, pre-processing the data and selecting features to a large extent. Users simply need to supply input data that is structured, including lab values and vital signs, and specify the outcome. Expertise in machine learning is not required, though knowledge of clinical data and predictive analytics can facilitate effective use. A user interface that is easy to use and customized for clinicians would further reduce adoption hurdles.

4.5. Future Investigation

To augment the SXI++ algorithm’s utility in prediction of Triage, future studies should aim to deploy it on an interoperable platform that interlinks with current electronic medical record (EMR) systems through real-time risk stratification by Sriya’s inbuilt multiagent bot. Prospective, randomized trials in various healthcare environments are underway to validate the performance of the model in different patient populations. In addition, research may investigate SXI++’s utility in the prediction of response to lifestyle interventions or pharmacological therapy in high-risk patients. Future research will focus on external validation and real-time evaluation to confirm the model’s durability and clinical usefulness, placing SXI++ at the center of precision medicine for the management of patient in need.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effectiveness of the SXI++ framework for emergency triage prediction using a curated dataset of 100,000 patient records and 180 clinically relevant features. The model achieved a high accuracy of 99.8%, precision of 99.8%, and an AUC of 0.999, demonstrating its superior capability to accurately distinguish between Emergency (Level 1–2) and Non-Emergency (Level 3–5) cases. The integration of decision tree-based interpretability enabled the identification of critical clinical factors—such as oxygen saturation, systolic blood pressure, and chief complaints—providing clear and actionable insights for frontline clinicians.

While the results are promising, this study was based on retrospective data from a single-source emergency triage dataset. Further research is required to assess the generalizability of SXI++ across diverse hospital settings, populations, and triage protocols. Prospective validations and real-world deployments are essential to evaluate the model’s performance under operational constraints. In conclusion, SXI++ shows significant potential for enhancing emergency department triage by delivering precise, interpretable, and clinically grounded predictions. With further validation, the model may support timely prioritization, optimize emergency resource utilization, and ultimately improve patient outcomes in critical care environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, S.K. resources, S.K. and M.B.; data curation, R.K. and D.D.; visualization, D.D., R.K.; formal analysis, D.D., R.K. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, P.Y., M.B., S.K.; project administration, P.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. The study used publicly available, de-identified data from Kaggle, originally collected by the Yale New Haven Health System with all necessary ethical approvals and patient consents obtained by the original investigators. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Since the research involved secondary analysis of anonymized data and did not include direct interaction with or intervention in human subjects, an ethics board review was not required. The study did not involve sensitive or personal data that would necessitate informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This study utilizes a retrospective dataset of adult emergency department visits from three Yale New Haven Health System hospitals (one academic and two community) collected between March 2014 and July 2017, obtained via Kaggle. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of Sriya through the use of the SXI framework

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. D.D., R.K., P.Y., S.K., are employed by Sriya.AI LLC. MB is employed at Clarkson University and is a consultant at Sriya.AI. Sriya.AI LLC has filed US provisional patents on the underlying core technology and its applications in the healthcare industry. 4 patents related to the technology have already been filed, which are cited as [

20,

21,

22,

23]. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| ESI |

Emergency Severity Index |

| XGBoost |

Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| DNN |

Deep Neural Network |

| EMR |

Electronic Medical Record |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| R2

|

Coefficient of Determination (R-squared) |

| SXI++ |

SRIYA EXPERT INDEX PLUS (A deep-learning framework for dynamic weighting of features) |

| LASSO |

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| PPV |

Positive Predictive Value (Precision) |

| NPV |

Negative Predictive Value (Recall) |

| HER |

Electronic Health Record |

| ED |

Emergency Department |

| SHAP |

Shapley Additive Explanations |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic curve |

| ESI |

Emergency Severity Index |

| EDs |

Emergency departments |

References

- Robertson-Steel I. Evolution of triage systems. Emerg Med J. 2006 Feb;23(2):154-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2564046/. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16439754 . [CrossRef]

- Romig LE. Pediatric triage. A system to JumpSTART your triage of young patients at MCIs. JEMS. 2002 Jul;27(7):52-8, 60-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12141119.

- Stanfield LM. Clinical Decision Making in Triage: An Integrative Review. J Emerg Nurs. 2015 Sep;41(5):396-403. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25814095 . [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarzehi N, Balouchi A, Sabzevari S, Darban F, Khayat NH. Effect of Triage Training on Concordance of Triage Level between Triage Nurses and Emergency Medical Technicians. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 May;10(5):IC05-IC07. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4948419/, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27437243.

- National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

- FitzGerald G, Jelinek GA, Scott D, Gerdtz MF. Emergency department triage revisited. Emerg Med J. 2010 Feb;27(2):86-92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20156855.

- Tanabe P, Travers D, Gilboy N, Rosenau A, Sierzega G, Rupp V, Martinovich Z, Adams JG. Refining Emergency Severity Index triage criteria. Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Jun;12(6):497-501. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15930399 . [CrossRef]

- Jordi K, Grossmann F, Gaddis GM, Cignacco E, Denhaerynck K, Schwendimann R, Nickel CH. Nurses’ accuracy and self-perceived ability using the Emergency Severity Index triage tool: a cross-sectional study in four Swiss hospitals. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015 Aug 28;23:62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4551516/, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26310569 . [CrossRef]

- Bullard MJ, Musgrave E, Warren D, Unger B, Skeldon T, Grierson R, van der Linde E, Swain J. Revisions to the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) Guidelines 2016. CJEM. 2017 Jul;19(S2):S18-S27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28756800 . [CrossRef]

- Zhu A, Zhang J, Zhang H, Liu X. Comparison of Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Four-Level and Three-District Triage Standard and the Australasian Triage Scale. Emerg Med Int. 2019;2019:8490152. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6885288/, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31827931 . [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi M, Heydari A, Mazlom R, Mirhaghi A. The reliability of the Australasian Triage Scale: a meta-analysis. World J Emerg Med. 2015;6(2):94-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4458479/, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26056538 . [CrossRef]

- Brouns SHA, Mignot-Evers L, Derkx F, Lambooij SL, Dieleman JP, Haak HR. Performance of the Manchester triage system in older emergency department patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2019 Jan 07;19(1):3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6322327/, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30612552 . [CrossRef]

- Zachariasse JM, Seiger N, Rood PP, Alves CF, Freitas P, Smit FJ, Roukema GR, Moll HA. Validity of the Manchester Triage System in emergency care: A prospective observational study. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170811. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5289484/, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28151987 . [CrossRef]

- Hodge A, Hugman A, Varndell W, Howes K. A review of the quality assurance processes for the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS) and implications for future practice. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2013 Feb;16(1):21-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23622553 . [CrossRef]

- T. Chen and C. Guestrin, “XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System,” in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, Aug. 2016, pp. 785–794. [CrossRef]

- Zhigang Sun, Guotao Wang, Pengfei Li, Hui Wang, Min Zhang, Xiaowen Liang, An improved random forest based on the classification accuracy and correlation measurement of decision trees. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov O, Wolf L, Brecher D, et al. Improving Emergency Department ESI Acuity Assignment Using Machine Learning and Clinical Natural Language Processing. arXiv. 2020;2004.05184. [CrossRef]

- Emergency Service—Triage Application. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ilkeryildiz/emergency-service-triage-application.

- Mahto D, Yadav P, Joseph AT, Kilambi S. AI2-SXI algorithm enables predicting and reducing the risk of less than 30 days patient readmissions with 99% accuracy and precision. J Med Artif Intell 2025; 8:10. [CrossRef]

- S. Kilambi (2024) AI Square Enabled by Sriya Expert Index (SXI): Method of Determining and Use. U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 63/549,553, 4 Feb 2024.

- S. Kilambi (2024) AI Square Enabled by Sriya Expert Index (SXI) Plus Reinforcement Learning. U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 63/553,335, 14 Feb 2024.

- S. Kilambi (2024) Processing of Large Numerical Models (LNM) by AI2 enabled SXI. U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 63/575,991, 8 Apr 2024.

- S. Kilambi (2024) AI Square Enabled by Sriya Expert Index (SXI): Generative AI. U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 63/554,252, 16 Feb 2024.

- Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso. J. Roy. Statist. Soc. B, 58(1), 267–288. [CrossRef]

- Luss, R., & d’Aspremont, A. (2007). Clustering and Feature Selection using Sparse PCA. arXiv preprint.

- Peng, H.-C., Long, F., & Ding, C. (2005). Feature selection based on mutual information: max-dependency, max-relevance, and mRMR. IEEE TPAMI, 27(8), 1226–1238.

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. KDD ‘16 Proceedings.

- Lewis, D.D. (1998). Naïve (Bayes) at Forty: The Independence Assumption in Information Retrieval. ECML-98, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 1398.

- Emergency Service—Triage Application. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ilkeryildiz/emergency-service-triage-application.

- Raita, Y., Goto, T., Faridi, M. K., Brown, D. F., Camargo, C. A., & Hasegawa, K. (2019). Emergency department triage prediction of clinical outcomes using machine learning models. Critical Care, 23(1), 64. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J., Kim, M. Y., Kim, M., Yeo, S. Y., & Hwang, H. (2024). Development of a Pediatric Emergency Triage Prediction Model Using Natural Language Processing with Pre-trained BERT Models. Healthcare Informatics Research, 30(2), 123–131. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).